Abstract

Background

Isoniazid resistance is an obstacle to the treatment of tuberculosis disease and latent tuberculosis infection in children. We aim to summarize the literature describing the risk of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis among children with tuberculosis disease.

Methods

We did a systematic review of published reports of children with tuberculosis disease who had isolates tested for susceptibility to isoniazid. We searched PubMed, Embase and LILACS online databasesuptoJanuary 12, 2012.

Results

Our search identified 3,403 citations, of which 95 studies met inclusion criteria. These studies evaluated 8,351 children with tuberculosis disease for resistance to isoniazid. The median proportion of children found to have isoniazid-resistant strains was 8%; the distribution was right-skewed (25th percentile: 0% and 75th percentile: 18%).

Conclusions

High proportions of isoniazid resistance among pediatric tuberculosis patients have been reported in many settings suggesting that diagnostics detecting only rifampin resistance are insufficient to guide appropriate treatment in this population. Many children are likely receiving sub-standard tuberculosis treatment with empirical isoniazid-based regimens, and treating latent tuberculosis infection with isoniazid may not be effective in large numbers of children. Work is needed urgently to identify effective regimens for the treatment of children sick with or exposed to isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis and to better understand the scope of this problem.

Keywords: drug resistance, mono-resistance, pediatric, INH, LTBI

INTRODUCTION

Isoniazid-resistant tuberculosisin adults and children is an obstacle to effective treatment of both tuberculosis disease and latent tuberculosisinfection (LTBI). According to recent global estimates,13.9% of new tuberculosis cases outside of the Eastern European region and 44.9% of new cases within the Eastern European regionhad isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis.1To date, no attempt has been made to quantify the risk of isoniazidresistance among children with tuberculosis.Understanding this risk is important because children are a sentinel population for transmission,2,3 and because isoniazid resistance may impact the choice of regimen used to treat children with both active tuberculosis disease and LTBI.

Studies of adults have demonstrated thatpatients with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis have higher rates of treatment failure compared to patients with susceptible strains when treated with standard chemotherapy regimens.4,5This increased risk of failure is present for both new and retreatment patients,5,6for patients with concurrent rifampin resistance and for those with other resistance patterns.6 Although data on the treatment outcomes ofchildren with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis are quite limited, isoniazidresistance may also erode the efficacy of combination regimens among young patients, and may contribute tothe amplification of resistance.

Although a number of regimens for treating latent tuberculosis infection have been developed,7the regimens most commonly recommended for the treatment of children are based on isoniazidalone.8,9 However, children with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis may not benefit from this prophylaxis. Case reports highlight the potential inefficacy of prophylaxis in child contacts of drug-resistant tuberculosis cases when the source case has a strain resistant to one or more of the drugs on which the prophylaxis regimen is based.10,11

Here we review the literature on isoniazidresistance in pediatric tuberculosis patients in order to better understand its potential impact on the treatment of children with tuberculosis disease and latent tuberculosis infection.

METHODS

Search strategy

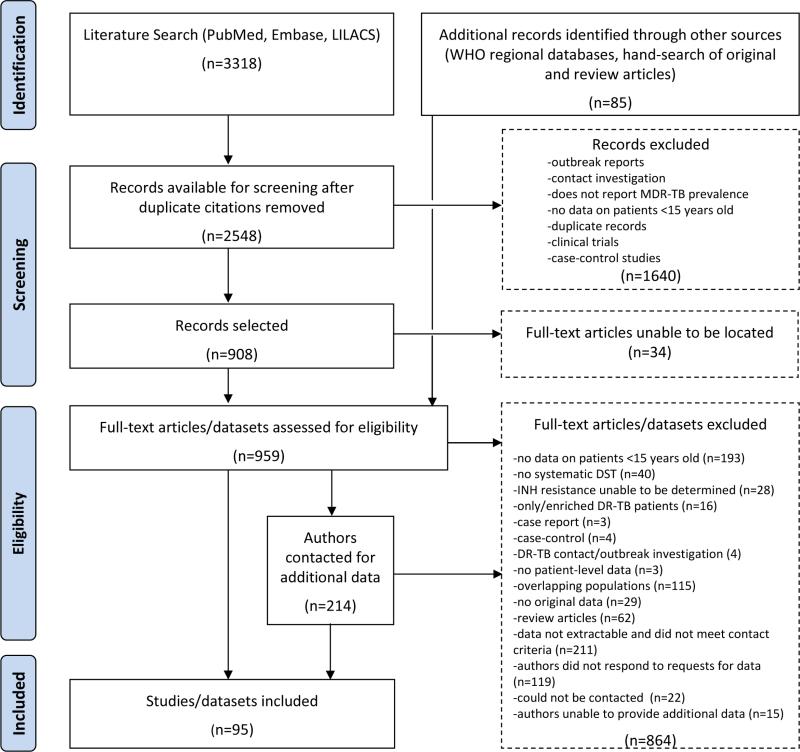

Our search strategy (Figure 1)aimed to identify studies that could provide an estimate ofthe proportion of children with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosisdisease based on drug-susceptibility testing (DST). We reviewed all published studies that reported this measure among a patient population that we expected would be representative of risk of isoniazid resistance among pediatric patients in the study base. Accordingly, we excluded reports where the inclusion of subjects may have been related to drugresistance (e.g., clinical trials, case-control studies). We also excluded reportsfrom outbreak or contact investigations, where resistance among the included subset of patients is expected to be highly correlated and less likely to represent resistance in the study base of all children with tuberculosis disease.We did not restrict the language of the publications reviewed.

Figure 1.

Search strategy

We systematically searched the PubMed, Embase and LILACS electronic databases for primary studies and review articles published through January 12, 2012. The search terms used controlled vocabulary and free text and included combinations intended to capture reports of drug-resistant tuberculosis (e.g. “resist*” and “tuberculosis,” “drug-resistant tuberculosis”) in children (e.g. “infan*,” “adolescen*,” “child*”).The complete search strategy is detailed in Addendum 1.

To identify relevant articles not found in these primary electronic databases, we also reviewed the reference lists of primary studies and reviews for additional references and searched the Western Pacific, Africa, South East Asia, and Eastern Mediterranean regional databases of the World Health Organization.

Initial review of studies

We compiled an initial database from the electronic searches and removed duplicate citations. Two reviewers (AWT and MCB or CMY) screened these citations by reviewing the title and abstract to capture relevant studies. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported the proportion of children with culture-confirmed tuberculosisdisease who had isolates tested for susceptibility toisoniazid. We resolved disagreements among the reviewers by consensus. For the group of citations that met the screening criteria, we obtained the full text to assess for eligibility. With the aid of translators, studies in multiple languageswere assessed for inclusion.

We contacted authors for additional information if the report met all of the following criteria: (a) the drug-susceptibility test results in the report were not disaggregated by age group (0-14 and ≥15 years), (b) published after 2000, and (c) published in English or Spanish. All correspondence was conducted through email.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: no pediatric (0-14 years old) patients, the study population was limited to patients with resistant tuberculosisorthese patients were preferentially enrolled, patients were identified through contact investigations of drug-resistant source cases, the study contained no original data or no patient-level data, or we could not determine the total number of pediatric patients with any isoniazidresistance (e.g. studies that explicitly omitted one or more subcategories of isoniazidresistance such as monoresistance).Additionally, studies for which data on the pediatric age group (defined as 0-14 years or 0-15 years) could not be extracted were excluded if authors were unable to provide additional data or did not respond to requests for data. If multiple studies analyzed the same or overlapping populations of patients, only the definitive report was included. Literature reviews and meta-analyses were excluded from data extraction, and their references were hand-searched for additional records.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (CMY, AWT) extracted all study data. A third reviewer (JBP) arbitrated any discrepancies between the first two reviewers. All final data was double-entered into a relational database designed for this purpose in Microsoft Access.

For each study, we extracted data about the number of children with tuberculosisdisease who had isolates tested forsusceptibility to isoniazid, and the proportion of those who had strains resistant to isoniazid. Where possible, we also extracted data about the number of children who had tuberculosis resistant to any drug and the number of children who had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), defined as those resistant to both isoniazid and rifampin(the backbone of the first-line anti-tuberculosis therapy).

The data extracted included the following information: location and enrollment year(s) of study, data source (e.g. national/regional surveillance, institution-based, randomized sample), patient population restrictions (e.g. failed treatment, HIV co-infected, extra-pulmonary tuberculosis), type of laboratory in which DST was performed, and DST data on children with culture-confirmed tuberculosis.

For each study that met inclusion criteria, we reportthe number of children with tuberculosisdisease who had strains tested for susceptibility to isoniazid, and the proportion of those children found to have strains resistant toisoniazid.

RESULTS

Of the 3,403 abstracts, we identified 95 studies that were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1).12-106The most common reason for exclusion was that resistance data on a pediatric age group were not extractable and the report did not meet our criteria for contacting the authors(n=211). We attempted to contact 214 authors and received 70 responses, of which 33 contained unpublished datathat we included in this review.

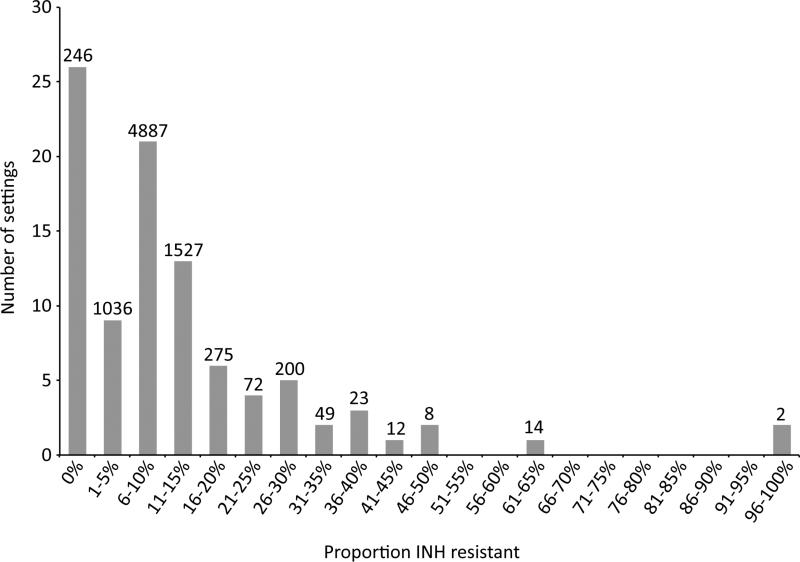

The 95 studies evaluated 8,351 children with tuberculosis disease who had isolates tested for susceptibility to isoniazid;69 studies (73%) reported at least one child with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis. The proportion of isoniazid-resistant strains detected among children tested in each study isshown in Table 1.The median proportion of children found to have isoniazid-resistant strains was 8%. The distribution of this proportion was right-skewed: the25th percentile for thisproportion was 0%, and the 75thpercentile was 18%. Figure 2 shows the frequency of studies reporting each proportion of isoniazid resistance.

Table 1.

Children with INH-resistant strains among all children with DST results in each of 95 studies

| Authors | Country | Years of enrollment | INH-resistant cases/cases with DST (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grosset et al.12 | Algeria | 1963-1966 | 10/152 (7) |

| Stauffer et al.13† | Austria | 1995-1998 | 2/108 (2) |

| Van Deun et al.14† | Bangladesh | 2001 | 0/11 (0) |

| Bajraktarevic et al.15† | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 1996-2007 | 27/444 (6) |

| Silveira et al.16 | Brazil | 1963-1970 | 35/133 (26) |

| Ferrazoli et al.17† | Brazil | 1995-1997 | 0/4 (0) |

| Telles et al.18† | Brazil | 2000-2002 | 2/5 (40) |

| Brito et al.19 | Brazil | 2004-2006 | 0/1 (0) |

| Sanders et al.20† | Burundi | 2002-2003 | 2/13 (15) |

| Farzad et al.21 | Canada | 1993-1994 | 0/14 (0) |

| Kassa-Kelembho et al.22 | Central African Republic | 1998-2000 | 15/165 (9) |

| Shen et al.23 | China | 2004-2005 | 0/3 (0) |

| Llerena et al.24 | Colombia | 2001-2009 | 16/128 (13) |

| Elenga et al.25 | Cote d'lvoire | 2000-2003 | 2/5 (40) |

| Thomsen et al.26 | Denmark | 0/18 (0) | |

| Christensen et al.27† | Denmark | 2000-2008 | 0/7 (0) |

| Espinal et al.28 | Dominican Republic | 1994-1995 | 0/2 (0) |

| Morcos et al.29 | Egypt | Unknown | 4/73 (0) |

| Tudo et al.30† | Equatorial Guinea | 1999-2001 | 1/5 (20) |

| Ejigu et al.31† | Ethiopia | 2005 | 3/11 (27) |

| Aho et al.32 | Finland | 1959-1961 | 7/26 (27) |

| Aho et al.33 | Finland | 1964-1965 | 1/2 (50) |

| Breton et al.34 | France | 1952 | 3/39 (8) |

| Kaplan et al.35 | France | 1955-1959 | 9/127 (7) |

| Brudey et al.36† | French overseas departments | 1994-2003 | 2/16 (13) |

| Kessler and Bartmann37 | Germany | 1959, 1961, 1962, 1964, 1965 | 7/48 (15) |

| Forssbohm et al.38 | Germany | 1997-2000 | 11/198 (6) |

| Haas et al.39 | Germany | 2004 | 16/90 (18) |

| Gitti et al.40† | Greece | 2000-2009 | 1/12 (8) |

| Scalcini et al.41 | Haiti | 1988 | 1/12 (8) |

| Kam and Yip42† | Hong Kong | 1985-1989 | 21/429 (5) |

| Swaminathan et al.43 | India | 1995-1997 | 22/175 (13) |

| Kumar et al.44 | India | 2000-2005 | 3/6 (50) |

| Joseph et al.45 | India | 2004 | 0/1 (0) |

| Aparna et al.46† | India | 2004-2005 | 2/22 (9) |

| Baveja et al.47 | India | 2004-2005 | 4/22 (18) |

| Agashe et al.48† | India | 2007-2008 | 9/14 (64) |

| Vadwai et al.49† | India | 2010 | 5/12 (42) |

| Romano et al.50 | Italy | 1994-2002 | 5/13 (38) |

| Osato et al.51 | Japan | 1964-1968 | 3/95 (3) |

| Tuberculosis research committee (Ryoken)52† | Japan | 2002 | 0/7 (0) |

| East African and British Medical Research Council53 | Kenya | 1964 | 5/96 (5) |

| East African and British Medical Research Council54 | Kenya | 1984 | 9/55 (9) |

| Githui et al.55 | Kenya | 1995 | 0/14 (0) |

| Araj et al.56 | Lebanon | 1996-1998 | 1/8 (13) |

| Rasolofo Razamparny et al.57 | Madagascar | 1997-2000 | 1/97 (1) |

| Ramarokoto et al.58 | Madagascar | 2005-2007 | 0/14 (0) |

| Warndorff et al.59† | Malawi | 1986-2010 | 7/69 (7) |

| Yang et al.60† | Mexico | Unknown | 1/1 (100) |

| Amaya-Tapia et al.61† | Mexico | 1993-1999 | 1/4 (25) |

| Zazueta-Beltran et al.62† | Mexico | 1997-2004 | 1/7 (14) |

| Buyankhishig et al.63 | Mongolia | 2007 | 3/11 (27) |

| Chaoui et al.64† | Morocco | Unknown | 0/3 (0) |

| Das et al.65† | New Zealand | 2001-2010 | 6/105 (6) |

| Krogh et al.66 | Norway | 1998-2009 | 4/19 (21) |

| Bujko et al.67 | Poland | 1960-1963 | 6/97 (6) |

| Zwolska et al.68 | Poland | 1996-1997 | 1/24 (4) |

| Leite et al.69† | Portugal | Unknown | 0/17 (0) |

| Al-Marri70 | Qatar | 1996-1998 | 0/3 (0) |

| Kim et al.71 | Republic of Korea | 1994 | 0/2 (0) |

| Rudoi et al.72 | Soviet Union | 5/20 (25) | |

| Alrajhi et al.73† | Saudi Arabia | 1995-2000 | 2/10 (20) |

| Kyi Win et al.74† | Singapore | 2000-2009 | 0/33 (0) |

| Schaaf et al.75 | South Africa | 1992-1997 | 1/9 (11) |

| Adhikari et al.76 | South Africa | 1996-1997 | 0/11 (0) |

| Soeters et al.77 | South Africa | 2000-2001 | 18/93 (19) |

| Schaaf et al.78 | South Africa | 2003-2005 | 65/592 (11) |

| Schaaf et al.79 | South Africa | 2005-2007 | 41/285 (14) |

| Fairlie et al.80 | South Africa | 2008 | 21/148 (14) |

| del Rosal et al.81 | Spain | 1978-2007 | 4/48 (8) |

| Marin Royo et al.82 | Spain | 1992-1998 | 0/17 (0) |

| Martin-Casabona et al.83 | Spain | 1995-1997 | 1/72 (1) |

| Mejuto et al.84† | Spain | 1996-2006 | 0/2 (0) |

| Borrell et al.85† | Spain | 2003-2004 | 0/15 (0) |

| Nejat et al.86† | Sweden | 2000-2009 | 14/40 (35) |

| Lin et al.87† | Taiwan | 1998-2002 | 0/40 (0) |

| Liu et al.88† | Taiwan | 2001-2002 | 0/2 (0) |

| Yoshiyama et al.89† | Thailand | 1996-1998 | 5/19 (26) |

| Dilber et al.90 | Turkey | 1975-1995 | 4/60 (7) |

| Kisa et al.91† | Turkey | 1998-2001 | 0/1 (0) |

| Cox et al.92† | Turkmenistan Uzbekistan | 2001-2002 | 0/3 (0) |

| Djuretic et al.93 | United Kingdom | 1993-1999 | 32/510 (6) |

| Story et al.94 | United Kingdom | 2003 | 6/29 (21) |

| Teo et al.95 | United Kingdom, Ireland | 2003-2005 | 10/102 (10) |

| East African and British Medical Research Council96 | United Republic of Tanzania | 1969-1970 | 2/42 (5) |

| Steiner and Cosio97 | U.S.A. | 1961-1964 | 5/80 (6) |

| Steiner et al.98 | U.S.A. | 1965-1968 | 10/103 (10) |

| Steiner et al.99 | U.S.A. | 1969-1972 | 12/79 (15) |

| Steiner et al.100 | U.S.A. | 1973-1980 | 6/72 (8) |

| Steiner et al.101 | U.S.A. | 1981-1984 | 2/19 (11) |

| Nolan et al.102 | U.S.A | 1979-1982 | 0/1 (0) |

| Khouri et al.103 | U.S.A. | 1981-1990 | 3/9 (33) |

| Bakshi et al.104 | U.S.A. | 1990-1992 | 1/1 (100) |

| Nelson et al.105 | U.S.A. | 1993-2001 | 178/2456 (7) |

| Al-Akhali et al.106 | Yemen | 2004 | 1/14 (7) |

Unpublished data received from author(s)

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of the proportion of children with isoniazid-resistanttuberculosis. Numbers above bars indicate the total number of children contributing to the denominator for each proportion.

Studies were classified according to their setting, data source, and restriction(s) on study population (when applicable) (Table 2).Studies reporting results from 57 countries and territories were included.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 95 studies that met inclusion criteria

| Reports included | 95 |

| Countries and territories included | 57 |

| Year range during which data were collected | 1952-2010 |

| Total pediatric patients with drug-susceptibility testing (DST) results for at least isoniazid and rifampicin | 8351 |

| New (%) | 2980 (36) |

| Previously treated (%) | 226 (3) |

| Unknown/unspecified treatment history (%) | 5145 (62) |

| Number of reports (%) | Number of pediatric patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of pediatric patients with DST results per report | ||

| 0-10 | 28 (29) | 114 (1) |

| 11-50 | 35 (37) | 749 (9) |

| 51-100 | 14 (15) | 1128 (14) |

| 101-500 | 15 (16) | 2802 (34) |

| >500 (max. 2,456) | 3 (3) | 3558 (43) |

| Source of data used in report | ||

| Reported surveillance data | 20 (21) | 3908 (47) |

| Hospital records | 48 (51) | 2736 (33) |

| Laboratory records | 9 (9) | 802 (10) |

| Representative population sample | 9 (9) | 270 (3) |

| Other or not specified | 4 (4) | 542 (6) |

| Reports with restricted study populations* | 32 (34) | 720 (9) |

Includes study populations restricted to patients with pulmonary TB, smear positive TB, extrapulmonary TB, TB meningitis, TB pleurisy, or HIV coinfection; patients with no previous treatment, patients who failed treatment, or patients on DOTS treatment; patients with HIV-infected family member(s); refugees; and/or contacts of source cases with DST results.

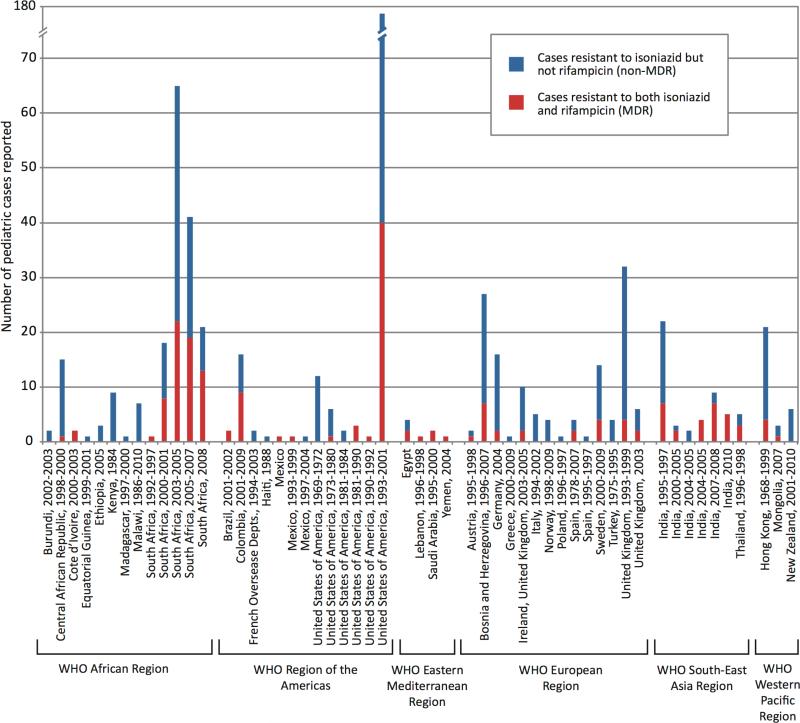

In 52 of the 71 studies that also reported DST results for drugs other than isoniazid, the majority of children with strains resistant to any drug had isolates resistant to isoniazid.In 35 of the 55 studies that reportedrifampinsusceptibilityresults for children with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis, the majority of the children with strains resistant to isoniaziddid not have MDR-TB (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of children with isoniazid-resistant strains with and without concomitant rifampin resistance (MDR-TB), from studies reporting rifampin susceptibility results for all isoniazid-resistant cases.

DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis in children. Longitudinal drug-resistance surveillance data, which are based almost exclusively on isolates obtained in adults,suggesta rising risk of isoniazidresistance for incident tuberculosis casesin many parts of the world.In 51 locations that reported data on isoniazidresistance for at least three time points between 1994 and 2009, 14showedan increasing risk of isoniazidresistance among new tuberculosis cases, while only two showed a decrease.1Among the studies that were included in the present analysis, we found a substantial risk of isoniazid resistance among children with tuberculosis disease(Figure 3).This finding has bearing on the treatment of both tuberculosis disease and latent tuberculosisinfection in children.

It is notable that we found only 95 studies (out of over 3000 abstracts screened) from which we could extract a prevalence of isoniazidresistance in a population of children with tuberculosis disease, and that two thirds of these studies included fewer than 50 children (Table 2). The paucity of reporting on anti-tuberculosis drugresistance in children reflects the challenges in diagnosing tuberculosis in children.107Bacteriologicconfirmation of tuberculosis in pediatric patients is more difficult than in adults, and the usefulness of sputum-based tests in particular is limitedbecausechildrenfrequently havepaucibacillarydisease and very young children cannotexpectorate.108Rapid DNA-based diagnostic approaches have shown some promise for identifying tuberculosis in sputum-smear negative pediatric populations.108,109 Since the most dominant of these testing modalities relies on identification of mutationsassociated with rifampinresistance, our finding that alarge proportion of children whosetuberculosisstrains haveisoniazidresistance without concurrent rifampin resistance raises concerns about using this approach alone for ensuring that children with tuberculosis disease receive appropriate therapy.

There are two principalconclusions that can be taken from this review of the literature.First are the implications on treatment of active disease and latent infection. We found reports of isoniazid resistance in pediatric tuberculosis patients from around the world, suggesting that clinicians and programs should be aware that this may be an emerging problem for their practice, even if no data have yet been reported from their locale. Adults with isoniazid-resistant tuberculosistreated with four-drug short-course chemotherapy are at higher risk for both treatment failureand amplification of resistance, compared to those with drug-susceptible disease.6,110,111Few reports describe treatment outcomes in children with isoniazid mono-resistant disease.112,113Indeed, in areas with low prevalence of isoniazid resistance, young children with uncomplicated disease can be treated with three drugs (isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide) during the intensive phase followed by isoniazid and rifampin only during the continuation phase.114 However, in areas where the prevalence of isoniazid resistance is high, ifa program uses a three-drug regimen to treat children, a substantial proportion of themmay receive only two effective drugs during the intensive phase of treatment and only one effective drug during the continuous phase.It is therefore important to determine the prevalence of isoniazid resistance in a population and, if this prevalence is high,to use a four-drug regimen for the treatment of children as recommended in the 2010 update of the international treatment guidelines for pediatric tuberculosis.114Although clear definitions of the threshold at which isoniazid resistance is considered high have not been established, our finding that a median of 8% of children with tuberculosis disease have isoniazid resistance is cause for a concern.

The widespread presence of isoniazid resistance in children also points to the need for alternative regimens to treat isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis in children. The implications of unrecognized isoniazid resistance for treatment outcomes are best illustrated in tuberculous meningitis. Tuberculous meningitis is a severe manifestation of tuberculosis with disease onset occurringwithin weeks of infection; it is more frequent in young children than in older children and adults, and,if untreated, it is uniformly fatal.115Untreated patients diein a median of 20 days.116A large cohort study of all tuberculousmeningitis cases reported in the U.S.over 13 years showed that isoniazidresistance was significantly associated with a higher risk of death despite treatmentamong patients who had positive cerebrospinal fluid cultures.117 However, a study from South Africa,has demonstrated thatalternative regimens that include a number of effective drugs with good cerebrospinal fluid penetration can eliminate the excess risk of child deaths that would be expected when isoniazid-based regimens are used to treat tuberculous meningitis.113More work to identify alternative regimens is urgently needed.

In terms of preventive treatment, our reviewsuggeststhat a significant proportion of children with LTBI may require alternativeprophylactic regimens.Most national policies currently indicateisoniazidprophylaxis to treat children with LTBI and child contacts of infectious tuberculosis cases.However, studies in adults have shown isoniazidprophylaxis to be ineffective at preventing tuberculosis disease caused by isoniazid-resistant strains.During an outbreak of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis in the homeless population of Boston, patients found to be tuberculin skin-test positive and treated prophylactically withrifampin had a significantly reduced occurrence of tuberculosis disease in the follow-up period compared to those who declined prophylaxis, but no reduction was observed among those given a prophylactic regimen consisting ofisoniazidalone.118In a study of Southeast Asian refugees who had received isoniazidprophylaxis, almost half of the cases of tuberculosis disease that developed despite prophylaxis had strains resistant to isoniazid.102Some evidence exists to support the efficacy of alternative prophylactic regimens for preventing tuberculosis diseasein adolescent contacts of isoniazid-resistant TB cases119 and child contacts of MDR-TB cases.120However, no controlled trials and very few cohort studies have evaluated alternativestrategies in children.121,122Our findings suggest that such research is critical.

The second principal conclusion to be taken from this review followsfrom the vast heterogeneity that we observed in the proportion of children with isoniazid-resistant diseaseacross studies. This is a strong reminder thata better understanding of local variability of the burden of pediatric drug-resistant tuberculosis will be critical to guide the decisions of clinicians and programs, such as the choice ofrapid diagnostics,alternative regimens,andthe procurement of specific drugs and pediatric formulations.While there are substantialchallengesin estimating the burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis among adults,123the challenges will be even greater for estimating the pediatric burden, given the difficulty of obtaining suitable sputum specimens from children. Thus, our reviewsuggests a need forinnovative efforts toestimate the burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis in pediatric tuberculosis patients specifically.

Our reportis subject to a number of limitations. First, almost 30% of the studies included in the finalstep (data extraction)reported 10 or fewer children who had strains tested for isoniazid resistance. In addition, very few of the reports were true population-based surveys with attempts to do representative sampling. For both these reasons, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the true prevalence of isoniazid resistance in childrenwith tuberculosis in the study locales.Second,because this is the first systematic review of this topic, wedeliberately employed broad inclusion criteria, which resulted indifferences among the populations of children in the included reports. Third, the vast majority of studies did not assess or provide information about the underlying isoniazid-resistance-conferring mutations.

In sum, this systematic review of the available literature shows that isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis in children is a widespread, geographically variable, but poorly quantified phenomenon. A better understanding of this problem is necessary to inform improvements to the management of tuberculosis in children, including optimizing approaches to the treatment of tuberculosis disease and latent infection, and to thedetection of drug resistance. Furthermore, improving access to timely susceptibility testing for at least both isoniazid and rifampin is critical, so that children can receive effective therapy. A one-size-fits-all approach may have deleterious consequences for large numbers of children with tuberculosis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the following authors who provided us with additional information not included in their published reports: Ibrahim Abubakar, Dissou Affolabi, VikasAgashe, SohailAkhtar, Abdulrahman A. Alrajhi, Gerardo Amaya Tapia, Jaffar A. Tawfiq, Delphine Antoine, Aparna B. Srikantam, George F. Araj, Adnan Bajraktarevic, Michael Baker, SayeraBanu, D. Bendayan, RutgerBennet, Sonia Borrell, Adrian Canizalez-Roman, M. Donald Cave, A. Chaiprasert, ImaneChaoui, Anne-Sophie Christensen, Helen Cox, Mohammed El Mzibri, LucilaineFerrazoli, Beatriz E. Ferro, Ines Suarez-Garcia, Zoe Gitti, Judith Glynn, Julian González-Martín, Helen Heffernan, Rein Houben, Y.-C. Huang, Kai Man Kam, Michael Kimerling, OzgülKisa, Khin Mar Kyi Win, Rafael Laniado-Laborin, Ana LuísaLeite, Theophile C.E.Liu, AthanasiosMakristhathis, Beatriz Mejuto, Julie Millet, P.R. Narayanan, OhkadoAkihiro , Françoise Portaels, T.Prammananan, NalinRastogi, Leen Rigouts, Camilla Rodrigues, ShubhadaShenai, GirumShiferaw, ArchanaSingal, Rupak Singla, SoumyaSwaminathan, Maria Alice Telles, Aleyamma Thomas, Griselda Tudó, Viral Vadwai, Armand Van Deun, Karin Weyer, Peter C.W. Yip, Takashi Yoshiyama, and theServizo de Control de Enfermidades Transmisibles, Dirección Xeral de Innovación e Xestión da Saúde Pública, Consellería de Sanidade.

We would also like to thank the following individuals who read articles in foreign languages and helped us to extract data from them:Tara Banani, Vera Bakman, Sophie Becker, YevgenyBrudno, Sun Chung, Anna Drachuk, Nadza Durakovic, Lisa Freinkman, Michinao Hashimoto, JitkaHiscox, Chuan-Chin Huang, CristianJitianu, Maria Joachim, RafalKorytkowski, ViktoriyaLivchits, Karolina Maciag, Aaron Shakow, MatyldaTomaszczyk, Angelique Wils, and Stephanie Wu.

And finally, we would like to thank reference and education librarian Paul Bain for his assistance with developing our search strategy, and Jonathan Eisenberg, Lowell Nicholson, Casey Traylor, and Vanessa Van Doren for research assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict Of Interest Statement and Source of Funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest or funding to disclose.

Contributors: CMY, AWT, and MCB designed the study. CMY, AWT, and JBP participated in data extraction. CMY analyzed the data. TC and SK guided data interpretation. CMY and MCB wrote the manuscript draft and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors participated in manuscript revisions and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jenkins HE, Zignol M, Cohen T. Quantifying the burden and trends of isoniazid resistant tuberculosis, 1994-2009. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloch AB, Snider DE., Jr How much tuberculosis in children must we accept? Am J Public Health. 1986;76:14–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shingadia D, Novelli V. Diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in children. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:624–32. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, et al. Effect of duration and intermittency of rifampin on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, et al. Standardized treatment of active tuberculosis in patients with previous treatment and/or with mono-resistance to isoniazid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lew W, Pai M, Oxlade O, Martin D, Menzies D. Initial drug resistance and tuberculosis treatment outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:123–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-2-200807150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad S. New approaches in the diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Respir Res. 2010;11:169. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sneag DB, Schaaf HS, Cotton MF, Zar HJ. Failure of chemoprophylaxis with standard antituberculosis agents in child contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:1142–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31814523e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tochon M, Bosdure E, Salles M, et al. Management of young children in contact with an adult with drug-resistant tuberculosis, France, 2004-2008. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:326–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosset J, Benhassine M. Antibiotic primary resistance of mycobacterium tuberculosis in hospitals in Algeria (1964-1966). Rev Tuberc Pneumol (Paris) 1967;31:475–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stauffer F, Makristathis A, Klein JP, Barousch W. Drug resistance rates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in Austria between 1995 and 1998 and molecular typing of multidrug-resistant isolates. The Austrian Drug Resistant Tuberculosis Study Group. Epidemiol Infect. 2000;124:523–8. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899004021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Deun A, Salim AH, Daru P, et al. Drug resistance monitoring: combined rates may be the best indicator of programme performance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bajraktarevic A, Mulalic Z, Perva N, et al. Tuberculosis in Bosnian children as result of endemic situation, refugees and migration. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:231. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silveira J, Medeiros S. Primary resistance in childhood. Correlation of infectious source with those exposed to infection. Torax. 1971;20:113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrazoli L, Palaci M, Marques LR, et al. Transmission of tuberculosis in an endemic urban setting in Brazil. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Telles MA, Ferrazoli L, Waldman EA, et al. A population-based study of drug resistance and transmission of tuberculosis in an urban community. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:970–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brito RC, Mello FC, Andrade MK, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in six hospitals in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:24–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders M, Van Deun A, Ntakirutimana D, et al. Rifampicin mono-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Bujumbura, Burundi: results of a drug resistance survey. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:178–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farzad E, Holton D, Long R, et al. Drug resistance study of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Canada, February 1, 1993 to January 31, 1994. Can J Public Health. 2000;91:366–70. doi: 10.1007/BF03404809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kassa-Kelembho E, Bobossi-Serengbe G, Takeng EC, Nambea-Koisse TB, Yapou F, Talarmin A. Surveillance of drug-resistant childhood tuberculosis in Bangui, Central African Republic. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:574–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen X, Shen M, Gui XH, Gao Q, Mei J. The prevalence and risk factors of drug-resistant tuberculosis among migratory population in Shanghai, China. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2007;30:407–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llerena C, Fadul SE, Garzon MC, et al. Drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in children under 15 years. Biomedica. 2010;30:362–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elenga N, Kouakoussui KA, Bonard D, et al. Diagnosed tuberculosis during the follow-up of a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire: ANRS 1278 study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:1077–82. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000190008.91534.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomsen VO, Bauer J, Lillebaek T, Glismann S. Results from 8 yrs of susceptibility testing of clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Denmark. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:203–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16b04.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen ASH, Andersen AB, Thomsen VT, Andersen PH, Johansen IS. Tuberculous meningitis in Denmark: A review of 50 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2011:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Espinal MA, Baez J, Soriano G, et al. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in the Dominican Republic: results of a nationwide survey. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:490–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morcos W, Morcos M, Doss S, Naguib M, Eissa S. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in Egyptian children using Etest. Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60:1385–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tudo G, Gonzalez J, Obama R, et al. Study of resistance to anti-tuberculosis drugs in five districts of Equatorial Guinea: rates, risk factors, genotyping of gene mutations and molecular epidemiology. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ejigu GS, Woldeamanuel Y, Shah NS, Gebyehu M, Selassie A, Lemma E. Microscopic-observation drug susceptibility assay provides rapid and reliable identification of MDR-TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:332–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aho K, Hallstrom K, Wager O. Incidence of primarily resistant tubercle bacilli in Finland. Difference in child and adult series. Acta Tuberc Pneumol Scand. 1962;42:214–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aho K, Brander E, Patiala J. Studies of primary drug resistance in tuberculous pleurisy. Scand J Respir Dis Suppl. 1968;63:111–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breton A, Gaudier B, Pierret R. Incidence of resistance of Koch bacillus to antibiotics during primary infection. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1956;13:664–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan M, Dobrowolski B. Study of the germs isolated from 289 cases of initial tuberculosis in children. Frequency of isolation. Cultural and biological characteristics. Resistance to antibiotics. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1960;17:605–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brudey K, Filliol I, Ferdinand S, et al. Long-term population-based genotyping study of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates in the French departments of the Americas. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:183–91. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.183-191.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessler R, Bartmann K. Primary isoniazid resistance in tuberculous children of West Berlin. Pneumonologie. 1971;145:400–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02095061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forssbohm M, Loddenkemper R, Rieder HL. Isoniazid resistance among tuberculosis patients by birth cohort in Germany. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:973–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haas WH, Altmann D, Brodhun B. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in childhood. Monatsschr Kinderh. 2006;154:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gitti Z, Mantadakis E, Maraki S, Samonis G. GenoType(R) MTBDRplus compared with conventional drug-susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a low-resistance locale. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:357–62. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scalcini M, Carre G, Jean-Baptiste M, et al. Antituberculous drug resistance in central Haiti. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:508–11. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kam KM, Yip CW. Surveillance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance in Hong Kong, 1986-1999, after the implementation of directly observed treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:815–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swaminathan S, Datta M, Radhamani MP, et al. A profile of bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis in children. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:743–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar A, Upadhyay S, Kumari G. Clinical Presentation, treatment outcome and survival among the HIV infected children with culture confirmed tuberculosis. Curr HIV Res. 2007;5:499–504. doi: 10.2174/157016207781662434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joseph MR, Shoby CT, Amma GR, Chauhan LS, Paramasivan CN. Surveillance of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in Ernakulam District, Kerala State, South India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:443–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aparna SB, Reddy VCK, Gokhale S, Moorthy KVK. In vitro drug resistance and response to therapy in pulmonary tuberculosis patients under a DOTS programme in south India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:564–70. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baveja CP, Gumma V, Jaint M, Chaudharyz M, Talukdar B, Sharma VK. Multi drug resistant tuberculous meningitis in pediatric age group. Iran J Pediatr. 2008;18:309–14. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agashe V, Shenai S, Mohrir G, et al. Osteoarticular tuberculosis--diagnostic solutions in a disease endemic region. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:511–6. doi: 10.3855/jidc.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vadwai V, Boehme C, Nabeta P, Shetty A, Alland D, Rodrigues C. Xpert MTB/RIF: a new pillar in diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis? J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2540–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02319-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romano A, Di Carlo P, Abbagnato L, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in Italian children by age at presentation. Minerva Pediatr. 2004;56:189–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osato T, Kihara K, Iwasaki T, Shimao T, Fukushima K. Studies on infection by drug-resistant tubercle bacilli. 2 Primary drug resistance in children. Kekkaku. 1968;43:431–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Japan: a nationwide survey, 2002. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1129–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tuberculosis in Kenya: a national sampling survey of drug resistance and other factors. Tubercle. 1968;49:136–69. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(68)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tuberculosis in Kenya 1984: a third national survey and a comparison with earlier surveys in 1964 and 1974. A Kenyan/British Medical Research Council Co-operative Investigation. Tubercle. 1989;70:5–20. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(89)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Githui WA, Juma ES, Van Gorkom J, Kibuga D, Odhiambo J, Drobniewski F. Antituburculosis drug resistance surveillance in Kenya, 1995. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:499–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Araj GF, Itani LY, Kanj NA, Jamaleddine GW. Comparative study of antituberculous drug resistance among Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates recovered at the American University of Beirut Medical Center: 1996-1998 vs 1994-1995. Journal Medical Libanais. 2000;48:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rasolofo Razanamparany V, Ramarokoto H, Clouzeau J, et al. Tuberculosis in children less than 11 years old: primary resistance and dominant genetic variants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Antananarivo. Arch Inst Pasteur Madagascar. 2002;68:41–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramarokoto H, Ratsirahonana O, Soares JL, et al. First national survey of Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug resistance, Madagascar, 2005-2006. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:745–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Warndorff DK, Yates M, Ngwira B, et al. Trends in antituberculosis drug resistance in Karonga District, Malawi, 1986-1998. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:752–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang ZH, Rendon A, Flores A, et al. A clinic-based molecular epidemiologic study of tuberculosis in Monterrey, Mexico. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:313–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amaya-Tapia G, Martin-Del Campo L, Aguirre-Avalos G, Portillo-Gomez L, Covarrubias-Pinedo A, Aguilar-Benavides S. Primary and acquired resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in western Mexico. Microb Drug Resist. 2000;6:143–5. doi: 10.1089/107662900419456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zazueta-Beltran J, Leon-Sicairos N, Muro-Amador S, et al. Increasing drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Sinaloa, Mexico, 1997-2005. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e272–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buyankhishig B, Naranbat N, Mitarai S, Rieder HL. Nationwide survey of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in Mongolia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1201–5. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chaoui I, Sabouni R, Kourout M, et al. Analysis of isoniazid, streptomycin and ethambutol resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Morocco. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:278–84. doi: 10.3855/jidc.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Das D, Baker M, Venugopal K, McAllister S. Why the tuberculosis incidence rate is not falling in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2006;119:U2248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krogh K, Suren P, Mengshoel AT, Brandtzaeg P. Tuberculosis among children in Oslo, Norway, from 1998 to 2009. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42:866–72. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.508461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bujko K, Zapasnik-Kobierska MH, Maliszewska Z, Kostrzenski W. Primary resistance to basic antituberculous drugs in tuberculosis in children. Pol Med Sci Hist Bull. 1966;9:81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zwolska Z, Augustynowicz-Kopec E, Klatt M. Primary and acquired drug resistance in Polish tuberculosis patients: results of a study of the national drug resistance surveillance programme. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:832–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leite AL, Carvalho I, Tavares E, Vilarinho A. Tuberculosis disease - statistics of a paediatric department in the 21st century. Rev Port Pneumol. 2009;15:771–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Marri MRHA. Pattern of mycobacterial resistance to four anti-tuberculosis drugs in pulmonary tuberculosis patients in the State of Qatar after the implementation of DOTS and a limited expatriate screening programme. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:1116–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim SJ, Bai SH, Hong YP. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in Korea, 1994. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;1:302–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rudoi NM, Rachinskii SV. Drug resistance of mycobacterium tubeculosis in young children. Probl Tuberk. 1963;41:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alrajhi AA, Abdulwahab S, Almodovar E, Al-Abdely HM. Risk factors for drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:305–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kyi Win KM, Chee CB, Shen L, Wang YT, Cutte J. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons, Singapore, 2000-2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:517–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.101615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schaaf HS, Geldenduys A, Gie RP, Cotton MF. Culture-positive tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:599–604. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adhikari M, Pillay T, Pillay DG. Tuberculosis in the newborn: an emerging disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:1108–12. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Soeters M, de Vries AM, Kimpen JLL, Donald PR, Schaaf HS. Clinical features and outcome in children admitted to a TB hospital in the Western Cape - The influence of HIV infection and drug resistance. S Afr Med J. 2005;95:602–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schaaf HS, Marais BJ, Whitelaw A, et al. Culture-confirmed childhood tuberculosis in Cape Town, South Africa: a review of 596 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schaaf HS, Marais BJ, Hesseling AC, Brittle W, Donald PR. Surveillance of antituberculosis drug resistance among children from the Western Cape Province of South Africa--an upward trend. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1486–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fairlie L, Beylis NC, Reubenson G, Moore DP, Madhi SA. High prevalence of childhood multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in Johannesburg, South Africa: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.del Rosal T, Baquero-Artigao F, Garcia-Miguel MJ, et al. Impact of immigration on pulmonary tuberculosis in Spanish children: a three-decade review. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:648–51. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d5da11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marin Royo M, Gonzalez Moran F, Moreno Munoz R, et al. Evolution of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the province of Castellon. 1992-1998. Arch Bronconeumol. 2000;36:551–6. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2896(15)30096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martin-Casabona N, Alcaide F, Coll P, et al. Drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Multicenter study in Barcelona, Spain. Medicina Clinica. 2000;115:493–8. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71603-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mejuto B, Tunez V, del Molino MLP, Garcia R. Characterization and evaluation of the directly observed treatment for tuberculosis in Santiago de Compostela (1996-2006). Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2010;3:21–6. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S8921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Borrell S, Espanol M, Orcau T, et al. Tuberculosis transmission patterns among Spanish-born and foreign-born populations in the city of Barcelona. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:568–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nejat S, Buxbaum C, Eriksson M, Pergert M, Bennet R. Pediatric Tuberculosis in Stockholm - A Mirror to the World. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011 doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31823d923c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin YS, Huang YC, Chang LY, Lin TY, Wong KS. Clinical characteristics of tuberculosis in children in the north of Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2005;38:41–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu CE, Chen CH, Hsiao JH, Young TG, Tsay RW, Fung CP. Drug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yoshiyama T, Supawitkul S, Kunyanone N, et al. Prevalence of drug-resistant tuberculosis in an HIV endemic area in northern Thailand. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:32–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dilber E, Gocmen A, Kiper N, Ozcelik U. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in Turkish children. Turk J Pediatr. 2000;42:145–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kisa O, Albay A, Baylan O, Balkan A, Doganci L. Drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a retrospective study from a 2000-bed teaching hospital in Ankara, Turkey. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;22:456–7. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(03)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cox HS, Orozco JD, Male R, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in central Asia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:865–72. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Djuretic T, Herbert J, Drobniewski F, et al. Antibiotic resistant tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: 1993-1999. Thorax. 2002;57:477–82. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.6.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Story A, Murad S, Roberts W, Verheyen M, Hayward AC. Tuberculosis in London: the importance of homelessness, problem drug use and prison. Thorax. 2007;62:667–71. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.065409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Teo SS, Riordan A, Alfaham M, et al. Tuberculosis in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:263–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.133645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tuberculosis in Tanzania: a national sampling survey of drug resistance and other factors. Tubercle. 1975;56:269–94. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(75)90084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Steiner M, Cosio A. Primary tuberculosis in children. 1 Incidence of primary drug-resistant disease in 332 children observed between the years 1961 and 1964 at the Kings County Medical Center of Brooklyn. N Engl J Med. 1966;274:755–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196604072741401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Steiner M, Steiner P, Schmidt H. Primary drug-resistant tuberculosis in children. A continuing study of the incidence of disease caused by primarily drug-resistant organisms in children observed between the years 1965 and 1968 at the Kings County Medical Center of Brooklyn. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1970;102:75–82. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1970.102.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Steiner P, Rao M, Goldberg R, Steiner M. Primary drug resistance in children. Drug susceptibility of strains of M. tuberculosis isolated from children during the years 1969 to 1972 at the Kings County Hospital Medical Center of Brooklyn. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110:98–100. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Steiner P, Rao M, Victoria MS, Hunt J, Steiner M. A continuing study of primary drug-resistant tuberculosis among children observed at the Kings County Hospital Medical Center between the years 1961 and 1980. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:425–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Steiner P, Rao M, Mitchell M, Steiner M. Primary drug-resistant tuberculosis in children. Emergence of primary drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis to rifampin. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:446–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.3.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nolan CM, Aitken ML, Elarth AM, Anderson KM, Miller WT. Active tuberculosis after isoniazid chemoprophylaxis of southeast Asian refugees. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:431–6. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.3.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Khouri YF, Mastrucci MT, Hutto C, Mitchell CD, Scott GB. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in children with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:950–5. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199211110-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bakshi SS, Alvarez D, Hilfer CL, Sordillo EM, Grover R, Kairam R. Tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. A family infection. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:320–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160270082027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nelson LJ, Schneider E, Wells CD, Moore M. Epidemiology of childhood tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2001: the need for continued vigilance. Pediatrics. 2004;114:333–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Al-Akhali A, Ohkado A, Fujiki A, et al. Nationwide survey on the prevalence of anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the Republic of Yemen, 2004. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1328–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reubenson G. Pediatric drug-resistant tuberculosis: a global perspective. Paediatr Drugs. 2011;13:349–55. doi: 10.2165/11593160-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Perez-Velez CM, Marais BJ. Tuberculosis in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:348–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1008049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marais BJ, Pai M. Specimen collection methods in the diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24:249–51. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.29381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Seung KJ, Gelmanova IE, Peremitin GG, et al. The effect of initial drug resistance on treatment response and acquired drug resistance during standardized short-course chemotherapy for tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1321–8. doi: 10.1086/425005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nagaraja SB, Satyanarayana S, Chadha SS, et al. How do patients who fail first-line tb treatment but who are not placed on an mdr-tb regimen fare in south india? PLoS ONE. 2011:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Steiner P, Rao M, Victoria M, Steiner M. Primary isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis in children. Clinical features, strain resistance, treatment, and outcome in 26 children treated at Kings County Medical Center of Brooklyn between the years 1961 and 1972. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110:306–11. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Seddon JA, Visser DH, Bartens M, et al. Impact of drug resistance on clinical outcome in children with tuberculous meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:711–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318253acf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rapid advice: Treatment of tuberculosis in children. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Starke JR. Tuberculosis of the central nervous system in children. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1999;6:318–31. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(99)80029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lincoln EM. Tuberculous meningitis in children; with special reference to serous meningitis; serous tuberculous meningitis. Am Rev Tuberc. 1947;56:95–109. doi: 10.1164/art.1947.56.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Vinnard C, Winston CA, Wileyto EP, MacGregor RR, Bisson GP. Isoniazid resistance and death in patients with tuberculous meningitis: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341:596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Polesky A, Farber HW, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rifampin preventive therapy for tuberculosis in Boston's homeless. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1473–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.5.8912767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Villarino ME, Ridzon R, Weismuller PC, et al. Rifampin preventive therapy for tuberculosis infection: experience with 157 adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1735–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schaaf HS, Gie RP, Kennedy M, Beyers N, Hesseling PB, Donald PR. Evaluation of young children in contact with adult multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis: a 30-month follow-up. Pediatrics. 2002;109:765–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fraser A, Paul M, Attamna A, Leibovici L. Treatment of latent tuberculosis in persons at risk for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.van der Werf MJ, Langendam MW, Sandgren A, Manissero D. Lack of evidence to support policy development for management of contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients: two systematic reviews. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:288–96. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cohen T, Colijn C, Wright A, Zignol M, Pym A, Murray M. Challenges in estimating the total burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1302–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-175PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.