Abstract

Purpose

To determine the effect of VEGF TrapR1R2 on bFGF-induced experimental corneal neovascularization (NV).

Methods

Control pellets or pellets containing 80 ng bFGF were surgically implanted into wild-type C57BL/6 and VEGF-LacZ mouse corneas. The corneas were photographed, harvested, and the percentage of corneal NV was calculated. The harvested corneas were evaluated for VEGF expression. VEGF-LacZ mice received tail vein injections of an endothelial-specific lectin after pellet implantation to determine the temporal and spatial relationship between VEGF expression and corneal NV. Intraperitoneal injections of VEGF TrapR1R2 or a human IgG Fc domain control protein were administered, and bFGF pellet-induced corneal NV was evaluated.

Results

NV of the corneal stroma began on day 4 and was sustained through day 21 following bFGF pellet implantation. Progression of vascular endothelial cells correlated with increased VEGF-LacZ expression. Western blot analysis showed increased VEGF expression in the corneal NV zone. Following bFGF pellet implantation, the area of corneal NV in untreated controls was (1.05±0.12 mm2 and 1.53±0.27 mm2) at days 4 and 7, respectively. This was significantly greater than that of mice treated with VEGF Trap (0.24±0.11 mm2 and 0.35±0.16 mm2 at days 4 and 7, respectively; p<0.05).

Conclusions

Corneal keratocytes express VEGF after bFGF stimulation and bFGF-induced corneal NV is blocked by intraperitoneal VEGF TrapR1R2 administration. Systemic administration of VEGF TrapR1R2 may have potential therapeutic applications in the management of corneal NV.

Keywords: VEGF TrapR1R2, bFGF, angiogenesis, cornea

INTRODUCTION

Corneal avascularity requires a balance between several endogenous angiogenic (including VEGF, bFGF) and anti-angiogenic (endostatin, thrombospondin-1) factors [1–4]. VEGF TrapR1R2, a VEGF antagonist, is a soluble fusion protein combining the truncated form of the fms-like tyrosine kinase (Flt), kinase insert domain-containing receptor (KDR) and Fc portion of human IgG. VEGF TrapR1R2 is designed to sequester, antagonize the VEGF and to prevent blood vessel formation [5, 6].

Angiogenesis is involved in both normal physiological processes as well as in pathological conditions; such processes and conditions include embryonic vessel formation, wound healing, tumor vascularization, rheumatoid arthritis, corneal neovascularization (NV) and diabetic retinopathy [1, 7–12]. Several angiogenic factors have been identified and characterized, including basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [13–16]. Investigation of the relationship between bFGF and VEGF during angiogenesis and tumor progression has elucidated a synergistic effect between these two factors in the induction of angiogenesis in vitro [17]. Additionally, Seghezzi et al. demonstrated that bFGF induces VEGF expression in vascular endothelial cells through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms [18].

In this report, we determine whether corneal keratocytes express VEGF after bFGF stimulation and whether bFGF-induced corneal NV is blocked by intraperitoneal VEGF TrapR1R2 administration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. VEGF-LacZ and C57BL/6 mice of approximately equal weights between the ages of 6–10 weeks were used.

Experimental corneal NV

bFGF pellets consist of the slow-release polymer Hydron (polyhydroxyethylmethacrylate) containing a combination of 45 ng/pellet of sucralfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with or without 80 ng/pellet of bFGF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and were made as previously described by Kenyon et al [19].

Briefly, a suspension of sterile saline containing the appropriate amount of recombinant bFGF and sucralfate was made and speed vacuumed for 5 minutes. Ten μl of 12% Hydron in ethanol was added to the suspension, which was then deposited onto a sterilized 15 mm2 piece of nylon mesh (LAB Pak, Sefar America, Depew, NY) and embedded between the fibers. The resulting grid of 10 x 10 mm squares was allowed to dry on a sterile Petri dish for 60 min. The fibers of the mesh were separated under a microscope and among the approximately 100 pellets produced, 30 to 40 uniformly-sized pellets of 0.4 x 0.4 x 0.2 mm3 were selected for implantation. All procedures were performed under sterile conditions. The pellets can be stored at −20°C for several days without loss of bioactivity.

Corneal micropocket assays were performed as described Kenyon et al, (1996) [19]. Eight weeks old mice were anesthetized by a combined ketamine and xylazine injection. Proparacaine eye drops were used for local anesthesia. Eye globes were proptosed with a jeweler’s forceps. Using an operating microscope (JKH operating surgical microscope), corneas were marked with a 3 mm trephine. Corneal lamellar micropocket incisions were created parallel to the corneal plane using a modified von Graefe knife along the trephine mark. A 0.5-mm incision perpendicular to the mouse corneal surface traversing the epithelium and anterior stroma toward the center of the cornea was performed with a 1/2-in., 30-gauge needle (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). A uniformly sized hydron pellet (0.4 x 0.4 x 0.2 mm) containing 80 ng of human bFGF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 40 μg of sucrose aluminum sulfate was placed on the corneal surface at the base of the pocket with jeweler’s forceps and using one arm of the forceps, the pellet was advanced to the end of the pocket. In all animals, we aimed for a 1 mm distance from the pellet to the limbus. Antibiotic ointment (Bacitracin) was then applied to the operated eye to prevent infection and to decrease surface irregularities. Corneal images were obtained perpendicular to the cornea at the pellet position to minimize the parallax as described previously by Kure et al. (2003) [20]. Two images of every pellet were obtained. The distances from limbus to pellets were measured by three independent observers, and were normalized to the overall average diameter (4.0mm).

Corneas were routinely examined and photographed. Photographs were digitized, and images were analyzed with the NIH ImageJ program.

Confocal microscopy

C57BL/6 mouse eyes were obtained on days 0, 1, 4, 7, 10, 14, and 21 after bFGF and blank pellet implantation, and were frozen in OCT compound (Baxter Scientific, Columbia, MD). Cryostat sections, 8 μm thick, were fixed in acetone for 10 min. After blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich), sections were incubated for 1 h with rat anti-CD31 antibody (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and goat anti-mouse VEGF antibody (R&D Systems) used at a 1:100 dilution. Secondary antibodies used were a Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG antibody and a rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (both from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Sections were viewed with a Leica TCS SP2 CLSM confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

VEGF-LacZ mice were implanted with either a bFGF pellet or a blank pellet. The mice received 8 μg/g tail vein injections of an endothelial-specific, fluorescein-conjugated lectin (lycopersicon esculentum) on days 1, 4 and 7 post-pellet implantation. Mice were then sacrificed and whole eyes were harvested and fixed in 10% neutral, buffered formalin for 24 h. The corneas were dissected and placed in blocking solution (1% BSA) for 4 h. The corneas were then incubated with a 1:200 dilution of biotin-conjugated IgG fraction of anti-β-galactosidase antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals Research Inc, Gilbertsville, PA) overnight, rinsed in PBS, and incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of rhodamine-conjugated streptavidin (Rockland) for 2 h. The specimens were rinsed in PBS and mounted on glass slides with Vectashield mounting medium for fluorescence imaging (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescence in the perfused vessels and LacZ expression was captured using a Leica TCS SP2 CLSM confocal laser scanning microscope.

Western blot analysis for VEGF expression

Wild-type mouse corneas were collected on day 7 after bFGF pellet implantation. Corneas were sectioned, homogenized, lysed with lysis buffer, and run on 4% to 20% SDS polyacrylamide gels (Novex, San Diego, CA). Proteins were electrotransferred onto nylon membranes (Immobilon P, Millipore, Bedford, MA), blotted with 3% BSA for 30 min, and incubated for 1 h with anti-VEGF antibody (R & D system, MN, USA, cat# AF-493-NA; 1:1000 dilution). Subsequently, horseradish peroxidase donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:20,000, GE Life Science, Piscataway, NJ) was used as secondary antibody. Human VEGF was used as a standard control (1:100).

After washing with Tris-buffered saline Tween-20 (TBST) for 15 min, immunoblots were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Intraperitoneal injection of VEGF TrapR1R2 into mouse after corneal bFGF pellet implantation

VEGF TrapR1R2 12.5 mg/kg or human Fc domain protein (hFc) (12.5 mg/kg; control) were intraperitoneally injected into mice immediately before bFGF pellet implantation in the cornea (n = 5 mice/group). Antibiotic ophthalmic ointment was applied after bFGF pellet implantation. Five additional mice with bFGF pellets served only as controls. The extent of corneal NV was photographed and quantified on days 4 and 7 after bFGF implantation. Subsequent experiments were performed to confirm the corneal bioavailability of VEGF TrapR1R2 and hFc in our model by goat anti-human Fc antibody (cat # G-102-C, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

RESULTS

bFGF induces VEGF expression in mouse corneas

The extent of corneal NV was assayed using bFGF pellets of 80 ng implanted into mouse corneas. New vessel growth began at day 4 post-intrastromal bFGF pellet implantation and progressed until day 21 (Figure 1).

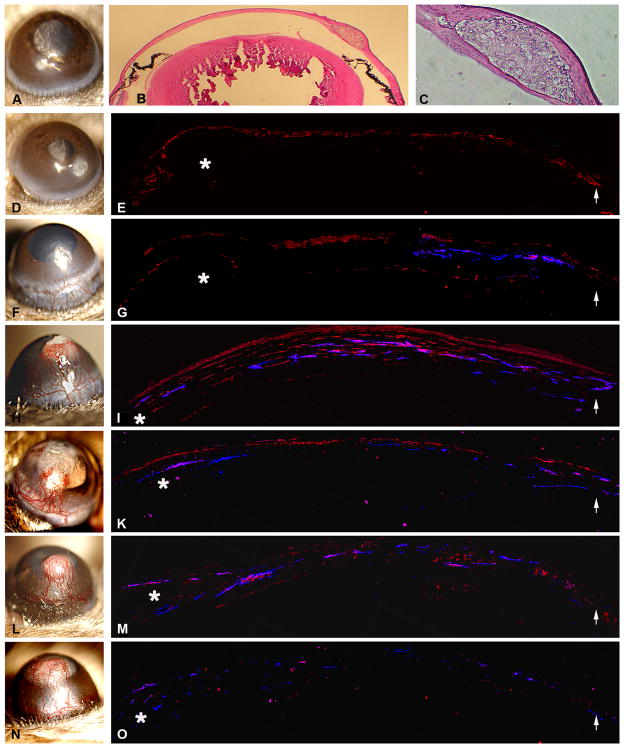

Figure 1.

Temporal and spatial relationship of VEGF expression and corneal vessel formation. Mouse corneas were implanted with a bFGF pellet and photographed by slit lamp on day 1 (D), day 4 (F), day 7 (H), day 10 (J), day 14 (L), and day 21 (N). A blank pellet was implanted as the control (A). bFGF pellet localization was shown in the transversal eye (B) and the intrastromal section (C). Sections of corneas were stained with anti-VEGF and anti-CD-31 antibodies on days 1 (E), 4 (G), 7 (I), 10 (K), 14 (M), and 21 (O). VEGF expression was noted in the corneal epithelium at day 1 (E). VEGF expression in the corneal keratocytes peaked on day 7 (I) and its expression decreased after 7 days. CD-31 localization lagged behind VEGF expression, which started on day 4 and continued until day 14. (* asterisk indicates the location of the bFGF pellet; arrows point to the limbus.) Areas of VEGF expression are stained red with anti-VEGF antibody; vascular endothelial cells are stained dark blue with anti-CD31 antibody.

VEGF expression was noted in the epithelium and perivascularly at day 4 (Figure 1G). The level of VEGF peaked on day 7 (Figure 1I) in the epithelium and corneal stroma, and diminished gradually by days 10, 14, and 21 (Figure 1).

Miquerol et al. generated VEGF-LacZ mice by inserting a reporter gene into the 3′ untranslated region of the endogenous VEGF gene so that VEGF and the LacZ reporter mRNA are produced from a bicistronic mRNA [21]. Using corneas from these VEGF-LacZ mice, the expression of VEGF and corneal vessels were visualized after injections of FITC-conjugated lectin into the tail vein. LacZ expression was noted in activated stromal cells on day 4 (Figure 2E) and increased on day 7 (Figure 2F) after bFGF pellet implantation.

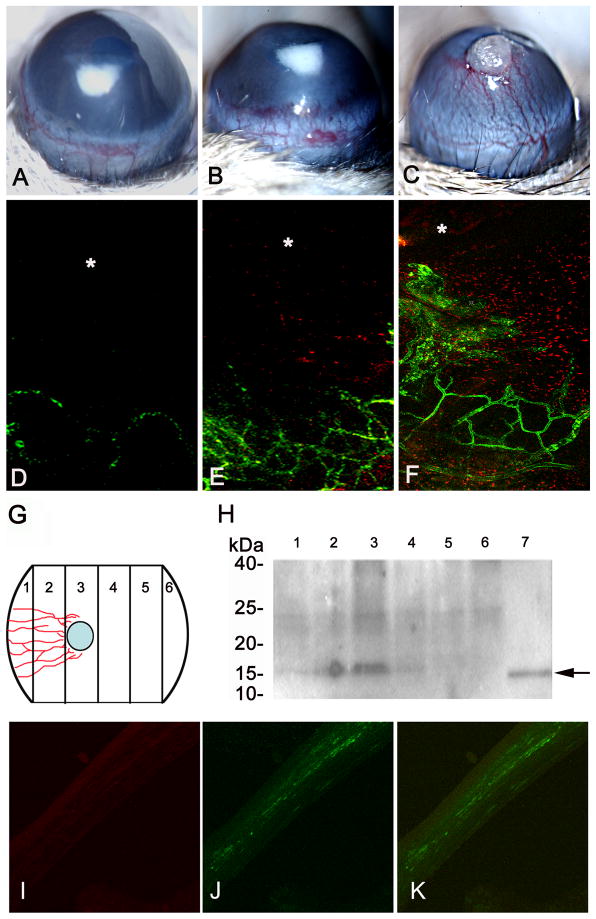

Figure 2.

VEGF expression correlated with vascular progression in the cornea. Vascular progression was induced by bFGF pellet implantation on days 1 (A), 4 (B), and 7 (C). Vascular endothelial cells were visualized by fluorescein-conjugated tomato lectin, and the progression of vessels was visualized by the VEGF-LacZ expression on days 1 (D), 4 (E), and 7 (F). LacZ expression (in red) was observed starting at day 4 and showed greater expression at day 7 (E–F). bFGF implanted corneas were divided into 6 segments as illustrated in (G) and were analyzed by Western blot analysis (H). Fifteen kDa bands (H, lanes 1 to 6) corresponding to VEGF expression in different segments (G, lanes 1 to 6) were observed. Recombinant VEGF was used as control (H, lane 7). The highest amount of VEGF was seen close to the pellet (H, lane 3) and in the segments adjacent to the pellet (H, lanes 2 and 4). There is also a lighter band noted at the limbal area closer to the pellet (H, lane 1). No VEGF expression was observed in segments away from the pellet (H, lanes 5 and 6). bFGF implanted corneas were coimmunostained with anti-VEGF antibody (I) and macrophage marker F4/80 antibody (J; merged image (K)).

bFGF pellet-implanted corneas were harvested and sectioned into a set of three mirror-image segments (Figure 2G and H). Lysates of these sections were analyzed by western blot analysis using an anti-VEGF antibody. Corneal segments with vascularization showed maximal VEGF expression at the area of the bFGF pellet.

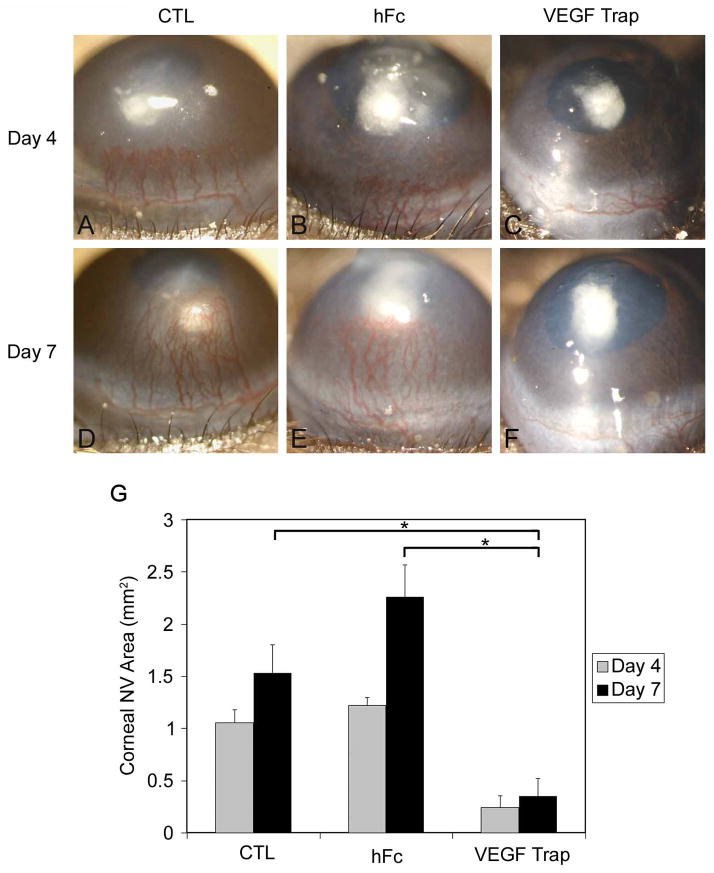

Blocking of bFGF-induced corneal NV via VEGF TrapR1R2

Mice were given a 12.5 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection of VEGF TrapR1R2 before corneal implantation of an 80 ng bFGF pellet. Mouse corneas implanted with a bFGF pellet with or without 12.5 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection of hFc-protein were used as controls. The distance of the pellet to the limbus was measured by 3 observers for each corneal images as described in the Materials and Methods section. There were no significant difference in the distance of pellets to limbus between 3 groups (control = 1.01mm±0.17mm; hFc = 1.21mm±0.22mm; VEGF Trap = 1.10mm±0.20mm; p=0.30). Following bFGF pellet implantation, the area of corneal NV in untreated controls was 1.05 ± 0.12 mm2 and 1.53 ± 0.27 mm2 at days 4 and 7, respectively. This was significantly greater than that of mice treated with VEGF TrapR1R2 (Figures 3C and 3F; 0.24 ± 0.11 mm2 and 0.35 ± 0.16 mm2 at days 4 and 7, respectively; P<0.05). Corneas displayed bFGF-induced NV on day 7 in the hFc protein intraperitoneal-treated group (Figures 3B and 3D; 1.21 ± 0.07 mm2 and 2.25 ± 0.30 mm2 at days 4 and 7, respectively). The results are summarized in Figure 3G.

Figure 3.

VEGF-TrapR1R2 blocks bFGF-induced corneal NV. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with VEGF TrapR1R2 or hFc-protein before 80 ng bFGF pellet implantation. Corneal NV was photographed at day 4 (A, B, and C) and day 7 (D, E, and F). The distance of the pellet to the limbus was measured by 3 observers for each corneal images as described in the Materials and Methods section. There were no significant difference in the distance of pellets to limbus between 3 groups (control = 1.01mm±0.17mm; hFc = 1.21mm±0.22mm; VEGF Trap = 1.10mm±0.20mm; p=0.30). Enhanced corneal NV was documented in bFGF-implanted corneas with hFc-protein injection (B, E) and without peptide injection (A, D). bFGF-induced corneal NV was blocked by intraperitoneally injected VEGF TrapR1R2 (C, F). At day 4 after bFGF pellet implantation, the areas of corneal NV in these three groups (bFGF pellet only, or combined with human Fc injection or VEGF TrapR1R2 injection) were calculated and compared (G).

DISCUSSION

Corneal NV usually is associated with inflammatory, infectious, degenerative, and traumatic disorders of the ocular surface. The pathological condition of corneal NV may result from the production of angiogenic factors by local epithelial cells, keratocytes, and infiltrating leukocytes [22]. During corneal NV, these angiogenic factors may directly or indirectly stimulate vascular endothelial cells to proliferate, migrate, and form new blood vessels.

Implantation of bFGF pellets in mouse corneas stimulates corneal vessel formation originating from the limbal area [19]. In this study, we investigated the role of VEGF in bFGF-induced corneal NV. Our results suggest that bFGF stimulates VEGF production in corneal keratocytes. In the corneal NV assay, vessels were visualized on day 4, peaked on day 7, and extended to day 21 following bFGF pellet implantation, with a concomitant increase in VEGF expression in the stroma. A similar experiment reported that corneas implanted with sham pellets do not induce corneal NV [23].

Cursiefen et al. have demonstrated that VEGF TrapR1R2, a soluble VEGF antagonist molecule, binds VEGF-A and PlGF but not VEGF-C and VEGF-D in vitro, and in mice, an intraperitoneal injection of VEGF TrapR1R2 blocked suture-induced corneal vessel formation [24]. We used similar conditions in our experiments, and show that VEGF TrapR1R2 blocked bFGF-pellet-induced corneal NV, much like the VEGF TrapR1R2-mediated block of suture-induced corneal NV [24].

We also used VEGF-LacZ transgenic mice to detect VEGF expression [21]. This allele allows independent translation of VEGF and LacZ from the same mRNA and reporter activity and can be detected at the single-cell level. LacZ expression was enhanced in the corneal keratocytes after bFGF pellet implantation in these VEGF-LacZ transgenic mice. The difference of the detection of VEGF expression after bFGF-pellet implantation in WT (C57BL/6) and VEGF-LacZ (129/sv) mice at day 1 may be due to different genetic backgrounds or the different antibodies used in immunostaining.

Our findings are consistent with other reports showing that bFGF-induced corneal NV may be mediated via VEGF. The expression of VEGF induced by bFGF pellet corneal implantation may not be limited to keratocytes. Seghezzi et al. have demonstrated that bFGF-induced vascular endothelial cells produce VEGF and induce corneal NV [18]. The bFGF-induced corneal NV can be partially blocked by using a neutralizing anti-VEGF antibody. Chang et al. and Cursiefen et al. have both demonstrated that VEGF also plays a role in bFGF-induced corneal lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis [22, 25]. Corneal suture or bFGF-pellet implantation recruits neutrophils and macrophages to the wounded cornea and produce VEGF, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D which further induces corneal NV. However, information regarding the production of VEGF by resident cells (keratocytes) in corneal angiogenesis is limited.

In this report, the experiments are consistent with the hypothesis that bFGF stimulates corneal keratocytes to produce VEGF. These data suggests that experimental corneal NV using bFGF pellets in mouse corneas can be blocked by systemic administration of VEGF TrapR1R2. In addition to its potential therapeutic applications for ocular angiogenesis, VEGF TrapR1R2 mechanisms may lead to a better understanding of corneal NV and possibly its prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. A. Nagy for providing VEGF-LacZ mice for this study.

Supported by an unrestricted Departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, and the National Institutes of Health EY001792 and EY10101 (DTA), and EY14048 (JHC).

Footnotes

Commercial relationships: None

References

- 1.Azar DT. Corneal angiogenic privilege: angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in corneal avascularity, vasculogenesis, and wound healing (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis) Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:264–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambati BK, Nozaki M, Singh N, Takeda A, Jani PD, Suthar T, Albuquerque RJ, Richter E, Sakurai E, Newcomb MT, Kleinman ME, Caldwell RB, Lin Q, Ogura Y, Orecchia A, Samuelson DA, Agnew DW, St Leger J, Green WR, Mahasreshti PJ, Curiel DT, Kwan D, Marsh H, Ikeda S, Leiper LJ, Collinson JM, Bogdanovich S, Khurana TS, Shibuya M, Baldwin ME, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, De Falco S, Witta J, Baffi JZ, Raisler BJ, Ambati J. Corneal avascularity is due to soluble VEGF receptor-1. Nature. 2006;443:993–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cursiefen C, Chen L, Saint-Geniez M, Hamrah P, Jin Y, Rashid S, Pytowski B, Persaud K, Wu Y, Streilein JW, Dana R. Nonvascular VEGF receptor 3 expression by corneal epithelium maintains avascularity and vision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11405–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maharaj AS, Saint-Geniez M, Maldonado AE, D’Amore PA. Vascular endothelial growth factor localization in the adult. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:639–48. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chappelow AV, Kaiser PK. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration: potential therapies. Drugs. 2008;68:1029–36. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudge JS, Holash J, Hylton D, Russell M, Jiang S, Leidich R, Papadopoulos N, Pyles EA, Torri A, Wiegand SJ, Thurston G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD. Inaugural Article: VEGF Trap complex formation measures production rates of VEGF, providing a biomarker for predicting efficacious angiogenic blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18363–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708865104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velazquez OC. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis: inducing the growth of new blood vessels and wound healing by stimulation of bone marrow-derived progenitor cell mobilization and homing. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(Suppl A):A39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakobsson L, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. Building blood vessels--stem cell models in vascular biology. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:751–5. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eming SA, Brachvogel B, Odorisio T, Koch M. Regulation of angiogenesis: wound healing as a model. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2007;42:115–70. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibuya M, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by VEGF receptors in regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:549–60. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motiejunaite R, Kazlauskas A. Pericytes and ocular diseases. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ejaz S, Chekarova I, Ejaz A, Sohail A, Lim CW. Importance of pericytes and mechanisms of pericyte loss during diabetes retinopathy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:53–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan W, Bentley B, Shao R. Distinct Angiogenic Mediators Are Required for Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor- and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-induced Angiogenesis: The Role of Cytoplasmic Tyrosine Kinase c-Abl in Tumor Angiogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2278–88. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee IY, Kim J, Ko EM, Jeoung EJ, Kwon YG, Choe J. Interleukin-4 inhibits the vascular endothelial growth factor- and basic fibroblast growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vitro. Mol Cells. 2002;14:115–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poltorak Z, Cohen T, Sivan R, Kandelis Y, Spira G, Vlodavsky I, Keshet E, Neufeld G. VEGF145, a secreted vascular endothelial growth factor isoform that binds to extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7151–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Folkman J, Shing Y. Control of angiogenesis by heparin and other sulfated polysaccharides. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;313:355–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2444-5_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ley CD, Olsen MW, Lund EL, Kristjansen PE. Angiogenic synergy of bFGF and VEGF is antagonized by Angiopoietin-2 in a modified in vivo Matrigel assay. Microvasc Res. 2004;68:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seghezzi G, Patel S, Ren CJ, Gualandris A, Pintucci G, Robbins ES, Shapiro RL, Galloway AC, Rifkin DB, Mignatti P. Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the endothelial cells of forming capillaries: an autocrine mechanism contributing to angiogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1659–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenyon BM, Voest EE, Chen CC, Flynn E, Folkman J, D’Amato RJ. A model of angiogenesis in the mouse cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1625–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kure T, Chang JH, Kato T, Hernandez-Quintela E, Ye H, Lu PC, Matrisian LM, Gatinel D, Shapiro S, Gosheh F, Azar DT. Corneal neovascularization after excimer keratectomy wounds in matrilysin-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:137–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.01-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miquerol L, Gertsenstein M, Harpal K, Rossant J, Nagy A. Multiple developmental roles of VEGF suggested by a LacZ-tagged allele. Dev Biol. 1999;212:307–22. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cursiefen C. Immune privilege and angiogenic privilege of the cornea. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2007;92:50–7. doi: 10.1159/000099253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onguchi T, Han KY, Chang JH, Azar DT. Membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase potentiates basic fibroblast growth factor-induced corneal neovascularization. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1564–71. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cursiefen C, Cao J, Chen L, Liu Y, Maruyama K, Jackson D, Kruse FE, Wiegand SJ, Dana MR, Streilein JW. Inhibition of hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis after normal-risk corneal transplantation by neutralizing VEGF promotes graft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2666–73. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang LK, Garcia-Cardena G, Farnebo F, Fannon M, Chen EJ, Butterfield C, Moses MA, Mulligan RC, Folkman J, Kaipainen A. Dose-dependent response of FGF-2 for lymphangiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11658–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404272101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]