In its 2006 report “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition,”1 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) provided suggestions for improving transitional and follow-up care for the growing population of cancer survivors. The IOM recommended that all patients completing primary treatment for cancer be provided with a comprehensive treatment summary and follow-up care plan, together referred to as a survivorship care plan (SCP).1,2 The IOM recommended that the SCP be reviewed with the patient during an end-of-treatment consultation, in the hope that use of an SCP and consultation would foster improved care coordination and communication.1 The IOM panel acknowledged the lack of an evidence base for survivorship care planning but concluded that “some elements of care simply make sense—that is, they have strong face validity and can reasonably be assumed to improve care unless and until evidence accumulates to the contrary.”1p5 However, the IOM report went on to call for health services research to assess the impact, cost, and acceptability of SCPs with regard to patients and providers.1

Nearly 7 years later, evidence regarding the impact of SCPs on care delivery and survivor outcomes remains limited and is primarily characterized by descriptive, exploratory, and pilot studies.3–9 Grunfeld et al5 conducted the single published randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of care planning in care coordination and patient-reported outcomes, which showed no effect. However, the validity and generalizability of the 2011 study findings have been questioned because of concerns about the appropriateness of the primary outcomes, aspects of the research design that may have affected results, and difficulty translating the findings from Canada to the United States.10–14 Another shortcoming of existing research on survivorship care planning is that it has not adequately addressed the diverse sociocultural backgrounds that survivors bring with them to the care context. Implementation problems compound the challenges posed by the lack of a robust and compelling evidence base. The development and delivery of SCPs is currently a resource-intensive activity that lacks adequate integration with technology platforms, clear reimbursement pathways, and clarity regarding who is responsible for generating and communicating the care plan to patients and providers.4,15,16 Despite these limitations, the American Society of Clinical Oncology has recommended adoption of chemotherapy treatment summaries as a 2008 Quality Oncology Practice Initiative indicator, and the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer has called for implementation of SCPs by January 2015.17,18

The flurry of commentaries after the publication of the results of Grunfeld et al5 generated a lively dialogue about next steps and urged us not to jump to conclusions about the efficacy or feasibility of survivorship care planning until further research was generated.10–13 To that end, researchers have called for studies of survivorship care planning to determine what information should be provided in SCPs and to whom, develop appropriate metrics to evaluate the efficacy of SCPs, and identify outcome constructs and measures more congruent with survivorship care planning intervention content and targets.12,13,15 Proposed outcomes for investigation include health and functional outcomes, lifestyle changes, under- and overuse of health care, and acquisition of support for unmet needs.7,10,12

Call for Context

We agree that if SCPs are to become a standard of care, their efficacy and viability in real-world settings must be thoughtfully and rigorously evaluated. But questions remain. What constructs should be evaluated? With which measures? What outcomes can reasonably be expected of survivorship care planning interventions? We argue that problems with the nascent science in this area stem from the conceptual divorcing of SCPs from the context of care and specifically from the process of care planning. In short, we have confused care plans with care planning. By focusing on the document rather than the processes and models of care in which SCPs are imbedded, we have taken care plans out of context and lost sight of the proverbial forest for the trees. Care plans exist in the context of processes of care, models of care, and technologies that can aid and impede care coordination and communication. Much like electronic health records, care plans are vehicles for communication and coordination of care, nothing more. We cannot expect a document to do the work of a process, and we certainly cannot expect it to fix a flawed process. It is only through revisiting the context of care plans that we can improve the quality of cancer follow-up care.

Toward a Conceptual Framework

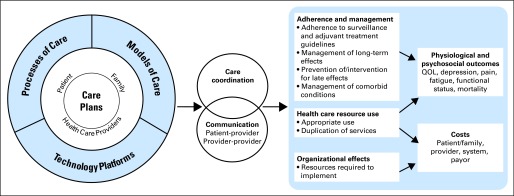

Without a guiding framework, problems are likely to persist in identifying relevant constructs and measures that map onto survivorship care planning activities. The pathways through which we might hope care plans would affect patient, provider, and systems outcomes need to be described. The scant research literature, in conjunction with IOM goals and recommended content for SCPs, suggests a conceptual framework incorporating the constructs shown in Figure 1. Although not intended to be definitive or exhaustive, we propose the framework described here as a starting point for building testable scientific models in care planning research.

Fig 1.

Conceptual framework for survivorship care planning research. QOL, quality of life.

In the concentric circle on the left side of the model, care plans are shown imbedded within the models of care, processes of care, and technology platforms that would ideally support the generation and sharing of SCPs. Models of care include the ways in which care is organized, the stakeholders involved in care, and the role expectations associated with those individuals. Processes of care are distinguished from models of care by the focus of the former on how various stakeholders operate and interact within the care system. Both models and processes of care should outline and attend to the settings and providers (eg, primary care, oncology, and other specialties) involved in the delivery and coordination of survivors' care. Technology platforms include, but are not limited to, electronic medical records, electronic and mobile health applications, and social media. The individuals involved in the generation and use of SCPs (patients, family members, and an array of health care providers) are represented in the middle ring of the circle. The intertwined circles to the right of the concentric circle represent the two intermediary constructs through which the IOM postulated survivorship care planning might affect survivor- and system-level outcomes: care coordination and communication. The rectangles to the right represent potential short-term and long-term outcomes. The first column holds three groupings of potential short-term outcomes of care planning: adherence to follow-up care protocols and provider management or self-management of late and long-term effects and comorbid conditions; health care resource use; and organizational effects of care planning, such as staff time and financial resources associated with the generation, sharing, and updating of care plans. The far right column includes two potential groups of long-term outcomes: physiologic and psychosocial morbidity and cost implications (savings or losses) of care planning for patients, providers, systems, and payers. It is not yet known whether the initial expenditures associated with the creation and delivery of SCPs will be balanced by long-term gains in communication and care coordination or if such gains will translate to net cost savings.

Developing an Evidence Base

The proposed framework facilitates the examination of survivorship care planning using diverse methodologies and speaks to the need for studies that will identify models and processes of care that may promote effective survivorship care planning and evaluate the impact of survivorship care planning on survivor-, provider-, and system-level outcomes. However, lack of standardization and consensus regarding the content of SCPs and of congruence with IOM-recommended components poses a challenge to the interpretation, comparison, and application of results.15 Therefore, studies should carefully describe the content and method of generation of the SCP and processes associated with the care planning intervention so that results can be interpreted in a meaningful way. Development of performance measures of quality care could also aid in assessing congruence with recommendations and evaluating outcomes of survivorship care planning.1

Because of the exploratory stage of the science, the existing survivorship care planning literature is characterized largely by cross-sectional studies. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the downstream effects of care planning on survivors, providers, and health care delivery systems. Comparative designs are needed to assess whether care planning provides added value beyond usual care. The optimal unit of analysis to be used in comparative designs is not yet clear and may include the patient, clinician, hospital, and health care system or have a multilevel focus. Both observational and experimental studies of the efficacy and implementation of care planning models and interventions are needed.

At present, survivorship care planning practices vary greatly. Future research should seek to describe the setting in which care planning occurs, the participants in the care planning process, and the structures and processes in place to support quality transitional and follow-up care. Studies documenting the organizational context and factors that promote or inhibit efficacious survivorship care planning are needed, including studies that explore how reimbursement and insurance practices affect the use of SCPs now, and how they will in the future, under the Affordable Care Act and accountable care mandates. It is likely that not all patients require the same degree and intensity of follow-up care and/or survivorship care planning. Risk assessment and stratification may be useful strategies for tailoring the content of SCPs and determining the frequency with which SCPs are revised and revisited with patients. Such strategies need to be evaluated for efficacy. Future research is also needed to understand how sociocultural diversity may influence survivorship care planning. Do populations differ in their preferences for how information is provided or shared? Are survivors from different sociocultural backgrounds more or less likely to receive appropriate and timely follow-up care? How can providers effectively deliver survivorship care planning for individuals from diverse backgrounds? These and other questions remain to be answered.

Research is needed exploring the optimal means of using technology to support survivorship care planning. Researchers and clinicians are examining how best to use electronic medical records and extant data repositories, such as state cancer registries, to more efficiently abstract and package data needed for SCPs.19,20 Other efforts are evaluating how technology may facilitate self-management of health after cancer.21 Going forward, research will be needed on ways technology can support the use of accessible SCP formats that are easily updatable by a variety of end users (care providers, patients, family members, and so on) and facilitate survivor adherence to follow-up care recommendations.

Further refinement of metrics and development of consensus on measurement are necessary to support research evaluating the efficacy of survivorship care planning. The National Cancer Institute Grid-Enabled Measures online tool provides a means for dialogue and building consensus in this area. It contains a dynamic library of 124 measures relevant to the evaluation of survivorship care planning, organized in domains such as quality of care, care coordination, and physical and psychosocial outcomes.22 Preliminary results of the Grid-Enabled Measures initiative suggest that measurement of patient-level outcomes is fairly well developed, but metrics are less well developed at the provider and system levels.

Finally, it is important that research in care planning be patient centered. This will necessitate understanding which questions are important to cancer survivors and understanding whether survivors feel that care planning strategies render them better prepared to manage their health and navigate their care in ways that are consistent with their needs and preferences. Do survivors understand what to expect after treatment? Whom to call, when, and for which problems? What follow-up care to seek and from which providers? These may be difficult questions to answer in a health care context unclear about provider roles and responsibilities and reimbursement mechanisms to support follow-up care. Nonetheless, these and many other questions remain to be answered. The question raised by the IOM report was broader than evaluation of SCPs; the question was how best to deliver high-quality transitional and follow-up care to cancer survivors. This is the question we should seek to answer with our science on survivorship care planning. This is the question that allows us to keep sight of the forest as well as the trees and improve outcomes for all cancer survivors.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. pp. 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- 2.President's Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2004. 2003-2004 Annual Report: Living Beyond Cancer—Finding a New Balance. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Earle CC. Long-term care planning for cancer survivors: A health services research agenda. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:64–74. doi: 10.1007/s11764-006-0003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faul LA, Rivers B, Shibata D, et al. Survivorship care planning in colorectal cancer: Feedback from survivors and providers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:198–216. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.651260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, et al. Evaluating survivorship care plans: Results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4755–4762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayer DK, Gerstel A, Leak AN, et al. Patient and provider preferences for survivorship care plans. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e80–e86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, et al. Increasing rates of breast cancer and cardiac surveillance among high-risk survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma following a mailed, one-page survivorship care plan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:818–824. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan ME, Butow P, Marven M, et al. Survivorship care after breast cancer treatment: Experiences and preferences of Australian women. Breast. 2011;20:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jefford M, Lotfi-Jam K, Baravelli C, et al. Development and pilot testing of a nurse-led posttreatment support package for bowel cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:E1–E10. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f22f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Palmer SC. Survivorship care plans: An argument for evidence over common sense. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1392–1393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Maunsell E, et al. Reply to M. Jefford et al and C.T. Stricker et al. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1393–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jefford M, Schofield P, Emery J. Improving survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1391–1392. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.5886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith TJ, Snyder C. Is it time for (survivorship care) plan B? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4740–4742. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earle CC, Ganz PA. Cancer survivorship care: Don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3764–3768. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Risendal B, et al. Survivorship care planning after the Institute of Medicine recommendations: How are we faring? J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:358–370. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blaseg K, Kile M, Salner A. Survivorship and palliative care: A comprehensive approach to a survivorship care plan. http://www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/accc/ncccp_monograph/index.php?startid=1#/50.

- 17.Commission on Cancer. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care (version 2) http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cps2012draft.pdf.

- 18.Siegel RD, Clauser SB, Lynn JM. National collaborative to improve oncology practice: The National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program Quality Oncology Practice Initiative experience. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:276–281. doi: 10.1200/JOP.091050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horowitz ME, Fordis M, Krause S, et al. Passport for care: Implementing the survivorship care plan. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:110–112. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0934405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, et al. An Internet tool for creation of cancer survivorship care plans for survivors and health care providers: Design, implementation, use and user satisfaction. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e39. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DuBenske LL, Gustafson DH, Shaw BR, et al. Web-based cancer communication and decision making systems: Connecting patients, caregivers, and clinicians for improved health outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2010;30:732–744. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10386382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cancer Institute. Grid-Enabled Measures Database: The GEM-Care Planning Initiative. http://www.gem-beta.org/GEM-CP.