Abstract

The 15 human kallikrein-related peptidases (KLKs) are clinically important biomarkers and therapeutic targets of interest in inflammation, cancer and neurodegenerative disease. KLKs are secreted as inactive pro-forms (pro-KLKs) that are activated extracellularly by specific proteolytic release of their amino-terminal pro-peptide and this is a key step in their functional regulation. Physiologically relevant KLK regulatory cascades of activation have been described in skin desquamation and semen liquefaction, and work by a large number of investigators has elucidated pair-wise and autolytic activation relationships among the KLKs with the potential for more extensive activation cascades. More recent work has asked whether functional intersection of KLKs with other types of regulatory proteases exists. Such studies show a capacity for members of the thrombostasis axis to act as broad activators of pro-KLKs. In the present report we ask whether such functional intersection is possible between the KLKs and members of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family by evaluating the ability of MMPs to activate pro-KLKs. The results identify MMP-20 as a broad activator of pro-KLKs, suggesting the potential for intersection of the KLK and MMP axes under pathological dysregulation of MMP-20 expression.

Keywords: kallikrein-related peptidases, KLK, activation cascade, matrix metalloproteinase, MMP-20, enamelysin

Introduction

The 15 members of the kallikrein-related peptidase family (KLK1-15) represent the largest cluster of S1 (or chymotrypsin-like) serine proteases within the human genome (Yousef and Diamandis 2001) and includes both trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like members. KLK3 (“prostate specific antigen” or PSA) is a widely used cancer biomarker for prostate cancer screening (Stamey 1987; Luderer 1995; Catalona 1997) and evidence suggests several other KLKs are differentially regulated in specific types of cancer (Clements 1989; Diamandis et al. 2000) and may also be useful as cancer biomarkers (Diamandis and Yousef 2001). Members of the KLK family have been shown to be associated with normal physiological and pathological processes of skin desquamation (Lundstrom and Egelrud 1991; Brattsand and Egelrud 1999; Brattsand et al. 2005), myelin turnover and inflammatory demyelination (Blaber et al. 2004; Scarisbrick et al. 2006), neurodegeneration (Scarisbrick et al. 2008), and semen liquefaction (Kumar et al. 1997; Vaisanen et al. 1999; Malm et al. 2000; Michael et al. 2006). Such studies point to the increasing importance of KLKs in the diagnosis and treatment of serious human medical disorders.

KLKs are secreted as inactive pro-forms that are subsequently processed extracellularly to their active form via proteolytic removal of their amino-terminal pro-peptide. This is a key regulatory step in controlling levels of active KLK relevant to both normal physiologic function and pathology. Numerous studies indicate that members of the KLK family participate in cascades of activation that regulate their function (Lovgren et al. 1997; Takayama et al. 1997; Sotiropoulou et al. 2003; Brattsand et al. 2005; Michael et al. 2006; Yoon et al. 2007). Such studies have resulted in a substantially complete characterization of the KLK “activome” (Yoon et al. 2007; Yoon et al. 2009) identifying both specific pair-wise and autolytic activation relationships. More recent studies investigating the intersection of KLK function with other major protease families has demonstrated the ability of plasmin, tPA, uPA, thrombin, factor Xa and plasma kallikrein of the thrombostasis axis to activate specific pro-KLKs (Yoon et al. 2008). Normally the secreted pro-KLKs in the extracellular matrix are isolated from thrombostasis proteases in the circulatory system; however, pathologies associated with vascular damage can enable these axes to intersect; thus, functional intersection is associated with pathological conditions.

The matrix metallproteases (MMPs) are a large family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases known as the metzincin superfamily (Page-McCaw et al. 2007). They function in the degradation of diverse types of extracellular matrix proteins and can also process a number of bioactive peptides. They are known to cleave cell surface receptors, release apoptotic ligands (such as the FAS ligand), and can activate and inactivate chemokines and cytokines (Van Lint and Libert 2007). In this report we ask whether the KLK and MMP family of proteases have the potential to functionally intersect by evaluating the ability of the MMPs to activate the pro-KLKs. Nine different members of the MMP family, including representatives of the collagenase, gelatinase, stromelysin and heterogenous classes, were initially evaluated for their ability to hydrolyze peptides representing the pro-sequences of the 15 different KLKs. This data indicated an ability of MMP-20 to correctly process the pro-sequence of nine different KLKs, and indicating that MMP-20 may be a “broad activator” of the KLK family. The ability of MMP-20 to activate specific pro-KLKs, including its natural substrate pro-KLK4, was subsequently quantified using expressed and purified recombinant pro-KLKs. The results show that MMP-20 is able to efficiently activate several members of the KLK family and with catalytic efficiency equal, or greater, to that for its normal pro-KLK4 substrate. MMP-20 expression is normally limited to dental enamel; however, it is hypothesized that disregulated expression of MMP-20 (as observed in pathologies of oral cancers), can result in functional intersection between the MMP and KLK family of proteases, leading to stimulation of KLK activation cascades.

Experimental Procedures

Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs)

MMP1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 13 were obtained from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, MN); MMP-20 was a gift of Dr. Wu Li, U.C. San Francisco. This set includes representative members of the collagenases (MMP-1,8,13), gelatinases (MMP-2,9), stromelysins (MMP-10), and heterogenous MMPs (MMP-7,12,20).

Pro-KLK fusion proteins

Quantitation of proteolytic specificity towards the 15 different KLK pro-peptide sequences was evaluated using a previously-described KLK pro-peptide fusion protein construct (Yoon et al. 2007; Yoon et al. 2008; Yoon et al. 2009). Briefly, the individual amino-terminus pro-peptide region of the 15 KLKs (comprising all “P” positions through the P6’ position, in addition to an N-terminus 6x-His tag) was fused to the N-terminus of a highly-soluble and protease resistant carrier protein (a mutant form of fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1)). This carrier protein provides solubility to each KLK pro-peptide, a highly solvated and unstructured N-terminus (as observed for the pro-KLK N-terminus (Gomis-Ruth et al. 2002)), rapid production from an E. coli expression host, and a mass differential upon pro-peptide hydrolysis that permits rapid evaluation using SDS PAGE. In the case of the pro-KLK4 sequence, a native Cys residue at position P3 was substituted by Ser to avoid potential disulfide bond-mediated dimer formation. All expression and purification steps were performed as previously described (Yoon et al. 2007). Purified pro-KLK fusion protein (1.0 mg/ml) was exchanged into 20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.15 M NaCl (PBS), pH 7.4, filtered through a 0.2 μm filter (Whatman Inc., Florham Park, NJ), snap-frozen in dry ice/ethanol, and stored at −80 °C prior to use. Samples of all pro-KLK fusion proteins were subjected to self-incubation, at a concentration of 50 μM, for 24 hrs at 37 °C, followed by SDS PAGE analysis, to confirm the absence of contaminating expression host proteases.

Pro-KLK fusion protein hydrolysis assay

Pro-KLK fusion proteins and MMPs (Matrix Metalloproteinases) were diluted into PBS, pH 7.4, and combined in a 100:1 molar ratio, respectively, with a final pro-KLK fusion protein concentration of 40 μM. Samples were incubated at 37 °C for either 1 hr or 24 hr, after which time they were immediately added to SDS-sample buffer and boiled to halt the reaction. The digestion samples (5.0 μg) were subsequently resolved using 16.5% Tricine SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The stained gels were scanned and the extent of hydrolysis quantified against pro-KLK fusion protein standards using UNSCAN-IT densitometry software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT). The pro-KLK fusion proteins that exhibited proteolytic cleavage were subjected to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis using a matrix of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid and performed on an Axima CFR-plus mass spectrometer (Shimadzu & Biotech, Columbia, MD). Those reactions exhibiting mass fragments inconsistent with the expected pro-peptide fragment were resolved on 16.5% Tricine SDS-PAGE, electro blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and subjected to aminoterminal peptide sequencing using an Applied Biosystems Procise model 492 protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Pro-KLK proteins

Recombinant pro-KLK1, pro-KLK2, pro-KLK4, pro-KLK6, and pro-KLK6(R74E/R76Q) mutant were expressed recombinantly from HEK293 human embryonic kidney epithelial cells as previously described (Blaber et al. 2007). Briefly, these recombinant proteins were expressed with addition of a C-terminal Strep-tag and His-tag, respectively. The KLK C-terminus is essentially antipodal to the N-terminus and as such, short C-terminal tags do not interfere with the N-terminal pro-region (Bernett et al. 2002; Gomis-Ruth et al. 2002). The cDNA encoding human pre-pro-KLKs was cloned into the pSecTag2/HygroB expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). In this construct the native secretion signals were utilized to direct secretion into the culture media. The HEK293 culture media was harvested 2 days after transfection, and the pro-KLK protein was purified by sequential nickel- and Strep-Tactin- affinity chromatography (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Purity and homogeneity of recombinant pro-KLK proteins were evaluated by 16.5% Tricine SDS-PAGE and N-terminal sequencing. Purity by gel scanning densitometry was determined to be >95% in each case. The absence of contaminating host protease activity was confirmed by lack of degradation (as determined by 16.5% Tricine SDS PAGE) after extended (6 hr) self-incubation at 50 μM, 37 °C, pH 8.0.

Pro-KLK activation assay

The determination of kinetic constants of activation of pro-KLK proteins by MMP20 utilized a coupled assay involving separate activation and detection steps. In the activation step pro-KLK protein (50-1,500 nM) was incubated with a catalytic amount (2 nM) MMP20 and incubated in 20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.4 (phosphate buffered saline, PBS) at 37 °C for an extended period (1-6 hr). The resulting pro-KLK substrate:MMP20 enzyme ratio therefore varied between 25:1 and 750:1. The exact time of incubation for activation was selected so that <15% of the pro-KLK substrate was hydrolyzed at the end of the activation step; thus, the reaction proceeded under conditions of pseudo-constant concentration. In the detection step the amount of activated KLK was determined using a fluorescent substrate (Boc-VPR-AMC) (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN) in PBS at 25 °C and a standard curve generated using known concentrations of mature KLK protein. The detection step was short (5 min) so as to effectively assay only the pro-KLK produced in the activation step and not any additional amount produced in the detection step. The concentration of Boc-VPR-AMC (100 μM) and 5 min incubation time in the detection step was chosen so as to limit the hydrolysis of Boc-VPR-AMC to <10%; thus, this step of the reaction also proceeded under conditions of pseudo-constant substrate concentration. 100 μM was the maximum practical concentration of Boc-VPR-AMC due to intermolecular quenching above this concentration resulting in non-linear effects. Fluorescence signal was quantified using a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with excitation wavelength of 380 nm and emission detection at 460 nm. The different pro-KLK substrate concentrations in the activation step were used to plot activation rate versus substrate relationships. In this regard, while pro-KLK substrate concentrations spanning both sides of the apparent Km value were desirable, 1,500 nM was a practical upper limit due to solubility and amounts of purified protein available. Reaction rate versus pro-KLK substrate concentration were analyzed using standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics, implemented in the non-linear curve-fitting software Datafit (Oakdale Engineering, Oakdale, PA).

Results

Hydrolysis of pro-KLK fusion proteins by MMPs

MMP-1, 8 and 13 are members of the collagenase family of MMPs. A 1 hr incubation of MMP-1 with the pro-KLK fusion proteins showed no significant hydrolysis (Supplemental Fig. S1); whereas, the 24 hr incubation resulted in essentially complete degradation of the pro-KLK fusion proteins in each case (Supplemental Fig. S2). A 1 hr incubation with MMP-8 showed evidence of specific but minor proteolytic cleavage for pro-KLK5, 7, 13, 14 and 15 (Supplemental Fig. S3). Extended 24 hr incubation with MMP-8 showed a characteristic ~14.5 and ~13.9 kDa doublet pattern for each pro-KLK fusion protein (Supplemental Fig. S4; however, the masses of these cleavage sites determined from SDS PAGE mass standards indicate they reside within the carrier protein and not the KLK pro-sequence. A 1 hr incubation with MMP-13 showed specific but minor proteolytic cleavage for pro-KLK5, 10 and 12 (Supplemental Fig. S5). Extended 24 hr incubation yielded only incremental increase in these minor cleavages (Supplemental Fig. S6).

MMP-2 and 9 are members of the gelatinase family of MMPs. A 1 hr incubation of MMP-2 with the pro-KLK fusion proteins showed specific but minor proteolytic cleavage for pro-KLK5, 7, 12 and 15 (Supplemental Fig. S7); however, the masses of these cleavage sites determined from SDS PAGE mass standards indicate they reside within the carrier protein and not the KLK pro-sequence. Extended 24 hr incubation with MMP-2 resulted in essentially complete degradation of the pro-KLK fusion proteins in each case (Supplemental Fig. S8). No specific hydrolyses of the pro-KLK fusion proteins were observed for MMP-9 even after 24 hr incubation (Supplemental Figs. S9 and S10).

MMP-10 is a member of the stromelysin family of MMPs. No specific hydrolyses of the pro-KLK fusion proteins were observed for MMP-10 even after 24 hr incubation (Supplemental Figs. S11 and S12).

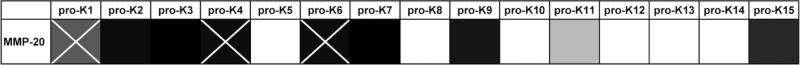

MMP-7, 12 and 20 are members of the heterogeneous family of MMPs. A 1 hr incubation of MMP-7 with the pro-KLK fusion proteins showed a complex fragmentation pattern shared by all the pro-KLK fusion proteins with masses indicating that the specific cleavage sites were within the carrier protein (Supplemental Fig. S13). Extended 24 hr incubation with MMP-7 resulted in essentially complete degradation of the pro-KLK fusion proteins in each case (Supplemental Fig. S14). A 1 hr incubation of MMP-12 with the pro-KLK fusion proteins showed complex fragmentation patterns shared by several of the pro-KLK fusion proteins (e.g. pro-KLK1, 2, 3, 4; and pro-KLK6, 7, 13, 14, 15), indicating that the specific cleavage sites were within the carrier protein (Supplemental Fig. S15); however, a specific and essentially complete hydrolysis was observed for pro-KLK10. Extended 24 hr incubation with MMP-12 resulted in complete degradation of the pro-KLK fusion proteins in each case (Supplemental Fig. S16). A 1 hr incubation of MMP-20 with the pro-KLK fusion proteins showed specific cleavages for several of the pro-KLK fusion proteins, including pro-KLK1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 10, 12, 14 and 15. In the case of pro-KLK3 and 4 these cleavages were essentially complete (Supplemental Fig. S17). Extended 24 hr incubation did not result in degradation; rather, the majority of the specific cleavages went to essential completion (including pro-KLK2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 14 and 15 (Supplemental Fig. S18). 24 hr hydrolyses samples of the pro-KLK1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14 and 15 fusion proteins by MMP-20 were subjected to mass spectrometry analyses and experimental masses for the processed KLK pro-peptide agreed with theoretical values for KLK1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, and 15 indicating correct processing to yield the mature KLK N-terminus (i.e. P1’ residue; Table 1). Experimental masses for the cleaved pro-peptide of KLK10 and 14 were aberrantly low; while masses associated with the released pro-peptide of KLK11 and 12 could not be identified. N-terminal sequencing was therefore performed on the pro-KLK10, 11, 12 and 14 large cleavage fragments to identify the site of cleavage. N-terminal sequence analyses showed that the cleavage of the pro-KLK10 fusion protein occurred between the pro-peptide P6 and P5 positions; cleavage of the pro-KLK11 fusion protein occurred between the correct propeptide P1 and mature N-terminus P1’ positions; cleavage of the pro-KLK12 fusion protein occurred between the pro-peptide P5 and P4 positions; and cleavage of the pro-KLK14 fusion protein occurred between the pro-peptide P7 and P6 positions (Table 1). Thus, analysis of the pro-KLK fusion protein hydrolyses indicated correct activation cleavage by MMP-20 for 9 of the 15 human pro-KLKs, including pro-KLK1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11 and 15. The relative efficiency of these hydrolyses, quantified by scanning densitometry of the Coomassie Blue stained SDS PAGE analyses, is pro-KLK3,7 > 2,4,6 > 9,15 > 1 > 11 (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 1.

Mass spectrometry and N-terminal sequence analysis of pro-KLK fusion protein hydrolyses by MMP-20.

| pro-peptide (theor) (Da) | pro-peptide (exp) (Da) | N-terminal sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-12 | |||

| pro-KLK10 | 1,953.89 | N.D. | Tyr [Glu Phe Asn Leu] P6’ [Carrier protein] |

| MMP-13 | |||

| pro-KLK10 | 1,953.89 | N.D. | Tyr [Glu Phe Asn Leu] P6’ [Carrier protein] |

| MMP-20 | |||

| pro-KLK1 | 1,878.89 | 1,879.26 | |

| pro-KLK2 | 1,922.95 | 1,924.79 | |

| pro-KLK3 | 1,879.95 | 1,880.59 | |

| pro-KLK4 | 1,761.75 | 1,777.26 | |

| pro-KLK6 | 2,014.87 | 2,015.33 | |

| pro-KLK7 | 1,886.80 | 1,887.28 | |

| pro-KLK9 | 1,952.85 | 2,024.24 | |

| pro-KLK10 | 1,953.89 | 1,340.07 | Gln Asn Asp Thr Arg P5 P4 P3 P2 P1 |

| pro-KLK11 | 1,629.71 | N.D | Ile Ile Lys Gly Phe P1’ P2’ P3’ P4’ P5’ |

| pro-KLK12 | 1,812.83 | N.D | Ala Thr Pro Lys Ile P4 P3 P2 P1 P1’ |

| pro-KLK14 | 1,959.81 | 1,255.24 | Gln Glu Asp Glu Asn Lys P6 P5 P4 P3 P2 P1 |

| pro-KLK15 | 1,743.74 | 1,744.35 | |

Hydrolysis of recombinant pro-KLK proteins by MMP-20

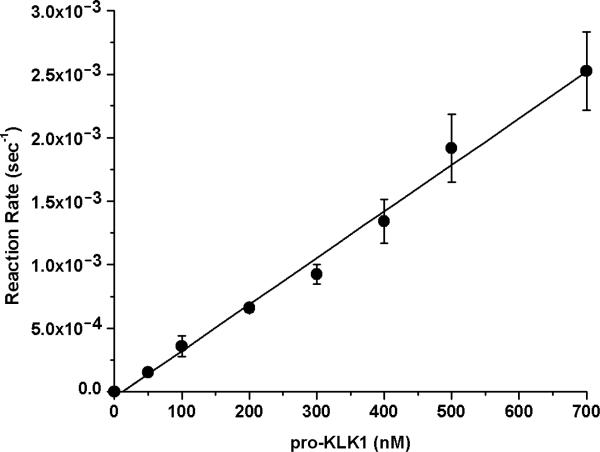

Activation of recombinant pro-KLK1 by MMP-20 was evaluated using 2 nM MMP-20 and a concentration range of pro-KLK1 of 0-700 nM. A 6 hr activation incubation period was utilized, resulting in <15% substrate hydrolysis in each case. The reaction rate versus concentration data demonstrated essentially first order kinetics over the 0-700 nM concentration range (Fig. 1), indicating that this concentration range is <Km. In this case the pseudo-first order kinetics approximate the value for kcat/Km, yielding a value of 3.7×103 sec−1M−1 (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Activation of recombinant pro-KLK1 by MMP-20 (PBS pH 7.4, 37 °C). The kinetics are pseudo-first order over the 0-700 nM substrate range evaluated indicating that this concentration range is <Km; thus, the pseudo-first order kinetics approximates the kcat/Km value for this enzyme/substrate combination.

Table 2.

Catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) for the activation by MMP-20 of recombinant pro-KLK1, pro-KLK4, and autolysis-resistant pro-KLK6/R74E/R76Q proteins (PBS pH 7.4, 37 °C).

| kcat/Km (sec-1M-1) | |

|---|---|

| pro-KLK1 | 3.7 × 103 |

| pro-KLK4 | 3.5 × 103 |

| pro-KLK6//R74E/R76Q | 7.3 × 103 |

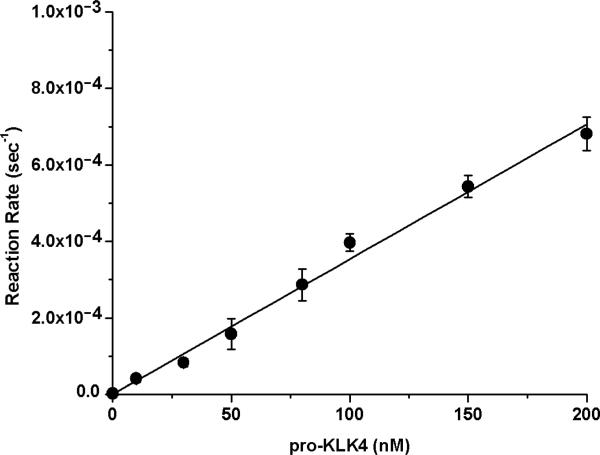

Activation of recombinant pro-KLK4 by MMP-20 was evaluated using 2 nM MMP-20 and a concentration range of pro-KLK4 of 0-200 nM. A 6 hr activation incubation period was utilized, resulting in <20% substrate hydrolysis in each case. The reaction rate versus concentration data demonstrated essentially first order kinetics over the 0-200 nM concentration range (Fig. 2), indicating that this concentration range is <Km. In this case the pseudo-first order kinetics approximate the value for kcat/Km, yielding a value of 3.5×103 sec−1M−1.

Fig. 2.

Activation of recombinant pro-KLK4 by MMP-20 (PBS pH 7.4, 37 °C). The kinetics are pseudo-first order over the 0-200 nM substrate range evaluated indicating that this concentration range is <Km; thus, the pseudo-first order kinetics approximates the kcat/Km value for this enzyme/substrate combination.

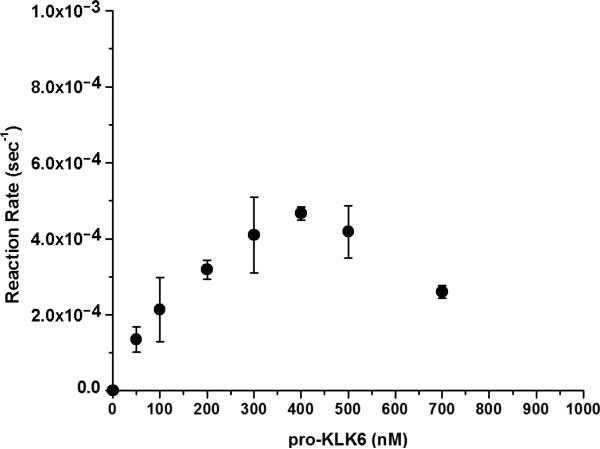

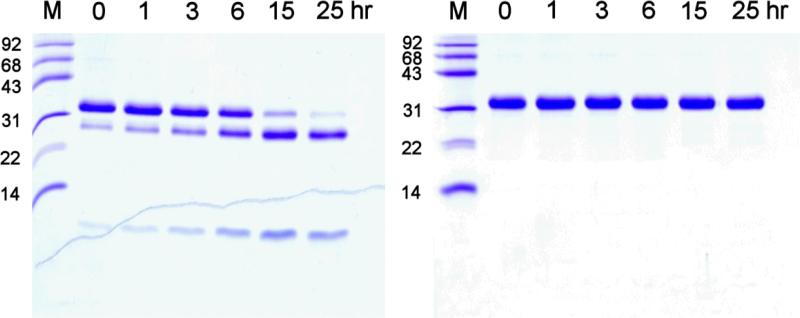

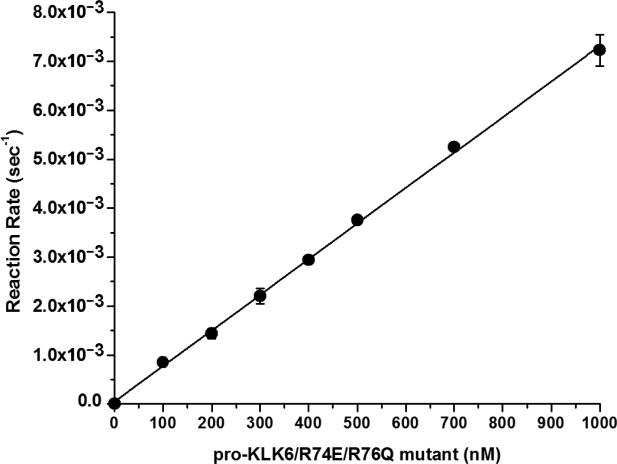

Activation of recombinant pro-KLK6 by MMP-20 was evaluated using 2 nM MMP-20 and a concentration range of pro-KLK6 of 0-700 nM. A 6 hr activation incubation period was utilized, resulting in <20% substrate hydrolysis in each case. The activation kinetics showed an apparent loss of KLK6 enzymatic activity at the higher substrate concentrations (Fig. 3). Since KLK6 is known to efficiently undergo autolytic inactivation via internal cleavage at specific internal basic residues (Bernett et al. 2002; Blaber et al. 2002; Blaber et al. 2007) a mutant human pro-KLK6 protein was constructed and expressed having Arg74Glu and Arg76Gln substitution mutations (pro-KLK6/R74E/R76Q). Extensive incubation with catalytic amounts of mature KLK6 (100:1 ratio, respectively) demonstrated effective resistance to internal cleavage in comparison to the wild-type protein (Fig. 4). Activation of recombinant pro-KLK6/R74E/R76Q by MMP-20 was evaluated using 2 nM MMP-20 and a concentration range of pro-KLK6/R74E/R76Q of 0-1,000 nM. A 2 hr activation incubation period was utilized, resulting in <20% substrate hydrolysis in each case. The reaction rate versus concentration data demonstrated essentially first order kinetics over the 0-1,000 nM concentration range (Fig. 5), indicating that this concentration range is <Km. In this case the pseudo-first order kinetics approximate the value for kcat/Km, yielding a value of 7.3×103 sec−1M−1.

Fig. 3.

Activation of pro-KLK6 by MMP-20 (PBS pH 7.4, 37 °C). Increased activation of the pro-KLK6 substrate results in an increasing extent of autolytic inactivation. The site of autolysis is Arg74 and Arg76 (Bernett et al. 2002; Blaber et al. 2002; Blaber et al. 2007).

Fig. 4.

Reduced Coomassie Blue stained SDS PAGE of recombinant pro-KLK6 (left panel) and pro-KLK6/R74E/R76Q mutant protein (right panel) incubated with mature KLK6 (100:1 molar ratio) and incubated in PBS pH 7.4 and 37 °C for the indicated time periods. The characteristic cleavage fragments at ~26 kDa and ~8 kDa are indicative of internal autolytic cleavage at adjacent positions Arg74 and Arg76 (the smaller of the two fragments is the N-terminal peptide; the larger fragment is the C-terminal peptide). Such cleavage results in functional inactivation of the KLK6 protein (Bernett et al. 2002; Blaber et al. 2002; Blaber et al. 2007). The R74E/R76Q mutations effectively abolish autolytic inactivation in the KLK6 protein.

Fig. 5.

Activation of pro-KLK6/R74E/R76Q by MMP-20 (PBS pH 7.4, 37 °C). The kinetics is pseudo-first order over a 0-1000 nM substrate range evaluated indicating that this concentration range is <Km; thus, the pseudo-first order kinetics approximates the kcat/Km value for this enzyme/substrate combination.

Discussion

Of the nine different MMPs evaluated (including members of the collagenase, gelatinase, stromelysin and heterogenous MMPs) only MMP-20 (Enamelysin, a member of the heterogeneous class) demonstrated cleavage specificity towards the KLK pro-peptide sequences (in a fusion protein construct). These cleavages resulted in the correctly processed mature N-terminus for nine of the 15 different pro-KLKs (pro-KLK1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, and 15). The activation potential of MMP-20 towards intact pro-KLK protein was subsequently evaluated for three different recombinant pro-KLK proteins including pro-KLK1 (requiring hydrolysis between an Arg-Ile bond), pro-KLK4 (requiring hydrolysis between a Gln-Ile bond), and pro-KLK6 (requiring hydrolysis between a Lys-Leu bond). Pro-KLK4 is the natural substrate of MMP-20 (Lu et al. 2008); thus, among the set of evaluated pro-KLKs is a functionally-relevant reference for catalytic efficiency. With the exception of pro-KLK4, activation of the KLK family of proteases involves specific hydrolysis after either Lys or Arg basic amino acids and differential specificity for hydrolysis after Arg or Lys can be a distinguishing feature of activating proteases(Blaber et al. 2007); thus, including pro-KLK1 and pro-KLK6 evaluates basic residue discrimination. KLK1 is known as “true kallikrein”, is a key component of the kallikrein-kinin system, and plays a role in inflammation, blood pressure control, coagulation and pain (Clements 1997; Margolius 1998). KLK6 is expressed robustly in the CNS and cerebrospinal fluid, and plays a role in myelin homeostasis and inflammatory demyelination in pathological conditions (Blaber et al. 2004; Scarisbrick et al. 2006; Scarisbrick et al. 2008). Activation of recombinant pro-KLK1, 4 and 6 by MMP-20 was confirmed and with catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) showing that MMP-20 can activate pro-KLK1 with similar efficiency to that of its recognized substrate pro-KLK4, and can activate pro-KLK6 with approximately twofold greater efficiency compared to its natural pro-KLK4 substrate.

MMP-20 functions to degrade enamel proteins in the mineralization of teeth. Ameloblasts (cells that deposit tooth enamel) secrete two proteases in tandem: MMP-20 as the enamel layer is being created in the early stage, followed temporally by pro-KLK4 (also known as enamel matrix serine protease-1) during the later maturation stage (Lu et al. 2008). The MMP-20 secreted in the early stage activates the pro-KLK4 secreted in the later maturation stage. The role of KLK4 is to degrade the enamel matrix protein which allows nascent enamel crystals to grow in thickness until adjacent crystals contact, thus permitting essentially complete mineralization of enamel (Lu et al. 2008). Defects in this system lead to amelogenesis imperfecta, a disease characterized by a high protein content and incomplete mineralization of enamel, resulting in brittle and easily fractured teeth (Lu et al. 2008). Activation of pro-KLK4 requires hydrolysis between a Gln-Ile bond and is unique in being the only pro-KLK where activation cleavage does not occur after a basic (i.e. Arg or Lys) residue. This Gln-Ile bond is not hydrolyzed by any known serine type protease (including KLKs) and appears uniquely dependent upon MMP-20. MMP-20 is also capable of degrading amelogenin, a major secreted enamel matrix protein. Cleavage specificity of porcine MMP-20 towards porcine and murine amelogenin includes Ser-Met, Phe-Ser, Pro-Leu, Pro-Ala, Ala-Leu, Trp-Leu, Pro-Met, His-His, and Ser-Gln bonds (Ryu et al. 1999; Nagano et al. 2009). MMP-20 has also been shown to cleave aggrecan interglobular domain protein at an Asn-Phe bond (Stracke et al. 2000). Cleavage of pro-KLK1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, and 15 pro-peptide requires hydrolysis between Arg-Ile, Gln-Ile, Lys-Leu, Lys-Ile, or Arg-Ala bonds. Thus, MMP-20 is remarkable in its broad specificity of hydrolysis. However, despite this apparent broad specificity, cleavage by MMP-20 of the pro-KLK sequences appeared remarkably precise for the individual activation sites. The structure of MMP-20 has been solved by solution NMR (Arendt et al. 2007) and shows a large and generally hydrophobic S1’ binding pocket (which accommodates the substrate P1’ amino acid; with hydrolysis occurring between substrate P1 and P1’ positions). Additionally, a study of substrate P3-P3’ specificities of MMP-20, determined from hydrolysis of a peptide library, demonstrated broad specificity at each substrate position except the P1' position which exhibited the greatest discrimination and a preference for large hydrophobic residues (Turk et al. 2006). Thus, an ability to accommodate hydrophobic P1’ substrate residues (as is the case with all pro-KLK activation sites) is consistent with the substrate binding site structural features of MMP-20. However, specific cleavage of pro-KLK5, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14, which was not observed, requires similar hydrolyses after Arg-Ile, Lys-Val, Arg-Leu, Lys-Ile, or Lys-Leu bonds, and there is no obvious rationale for the MMP-20 not to activate these other pro-KLKs. Available structural details for the pro-KLKs is limited to a single example (pro-KLK6 (Gomis-Ruth et al. 2002)) and shows that the pro-peptide of KLK6 is highly solvent exposed and flexible, and such accessibility and flexibility may be a requirement for efficient MMP-20 hydrolysis. Thus, a possible hypothesis for the inability of MMP-20 to activate pro-KLK5, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14 is that their pro-peptide is structured in such a way as to prevent efficient cleavage; alternatively, secondary binding interactions (i.e. exosites) with the activatable pro-KLKs may participate to yield efficient hydrolysis.

MMP-20 exhibits tightly-restricted tissue expression and has been identified from Northern blots as being expressed almost exclusively in teeth (Bartlett et al. 1996; Llano et al. 1997) although minor expression in intestine was identified using qPCR methods (Turk et al. 2006). The process of enamel formation in the maturation of teeth occurs over a time frame of weeks to months. The catalytic efficiency of MMP-20 for its pro-KLK4 substrate is on the order of 103 sec−1M−1, placing MMP-20 in the lower quartile of typical enzyme efficiencies (the median being 105 sec−1M−1) (Bar-Even et al. 2011). However, this level of efficiency is perhaps appropriate given its functional role and the temporal process of enamelization. The results show that MMP-20 can exhibit greater efficiency in the activation of other pro-KLKs (e.g. pro-KLK6) in comparison to its natural pro-KLK4 substrate, and based upon the data presented herein MMP-20 can be described as a potential “broad activator” of the KLK family (Fig. 6). In this regard, the tight transcriptional control of MMP-20 to teeth limits its ability to activate pro-KLKs other than pro-KLK4. However, abnormal expression of MMP-20 has been reported in tongue squamous cell carcinoma (Vaananen et al. 2001), neoplastic epithelial cells of odontogenic tumors (Takata et al. 2000; Vaananen et al. 2004), and adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (Sekine et al. 2004). The KLKs are widely distributed in most tissues and disregulation of MMP-20 associated with pathological conditions can potentially lead to broad activation of the KLK axis (notably, the submandibular gland is a rich source of expression of the KLKs (Shaw and Diamandis 2007), and multiple KLKs have been identified as expressed in squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity (Pettus et al. 2009)). Intersection of the KLK axis with the thrombostasis axis under conditions of vascular injury or pathology has previously be proposed from in vitro activation relationships, with plasmin identified as a notable broad-activator of the pro-KLKs (Yoon et al. 2008). Based upon the data herein we propose a similar functional intersection between the KLKs and MMPs, principally demonstrated for MMP-20 and associated with disregulated expression. Based upon studies of the cross-activating potential of the KLKs (i.e. the KLK activome) disregulated activation of one or more KLKs can potentially initiate a broader cascade of KLK activation (Cassim et al. 2002; Brattsand et al. 2005; Pampalakis and Sotiropoulou 2007; Yoon et al. 2007).

Fig. 6.

Grey scale “heat map” for the correct activation cleavage of pro-KLK fusion proteins by MMP-20 (PBS, pH 7.4, 24 hr). White indicates 0% hydrolysis and black indicates 100% hydrolysis (as quantified by gel densitometry; Supplemental Table S1). The white “X” is used to indicate activation relationships confirmed by kinetic analyses of activation of recombinant pro-KLK proteins by MMP-20.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a research grant from the Florida State University College of Medicine (MB) and NIH grants 1R01NS052741-01A2 (IAS) and 2R01DE015821 (WL).

Abbreviations

- KLK

kallikrein-related peptidase

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- SDS PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney epithelial cells

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- MALDI-TOF

matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

References

- Arendt Y, Banci L, Bertini I, Cantini F, Cozzi R, Del Conte R, Gonnelli L. Catalytic domain of MMP20 (Enamelysin) - The NMR structure of a new matrix metalloproteinase. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4723–4726. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Even A, Noor E, Savir Y, Liebermeister W, Davidi D, Tawfik DS, Milo R. The moderately efficient enzyme: evolutionary and physicochemical trends shaping enzyme parameters. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4402–4410. doi: 10.1021/bi2002289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, Simmer JP, Xue J, Margolis HC, Moreno EC. Molecular cloning and mRNA tissue distribution of a novel matrix metalloproteinase isolated from porcine enamel organ. Gene. 1996;183:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00525-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernett MJ, Blaber SI, Scarisbrick IA, Dhanarajan P, Thompson SM, Blaber M. Crystal structure and biochemical characterization of human kallikrein 6 reveals a trypsin-like kallikrein is expressed in the central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:24562–24570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202392200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber SI, Ciric B, Christophi GP, Bernett M, Blaber M, Rodriguez M, Scarisbrick IA. Targeting kallikrein 6 proteolysis attenuates CNS inflammatory disease. FASEB J. 2004;18:920–922. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1212fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber SI, Scarisbrick IA, Bernett MJ, Dhanarajan P, Seavy MA, Jin Y, Schwartz MA, Rodriguez M, Blaber M. Enzymatic properties of rat myelencephalon specific protease. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1165–1173. doi: 10.1021/bi015781a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaber SI, Yoon H, I.A. S, Juliano MA, M. B. The Autolytic Regulation of Human Kallikrein-Related Peptidase 6. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5209–5217. doi: 10.1021/bi6025006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattsand M, Egelrud T. Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of a human stratum corneum trypsin-like serine protease with possible function in desquamation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:30033–30040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattsand M, Stefansson K, Lundh C, Haasum Y, Egelrud T. A proteolytic cascade of kallikreins in the stratum corneum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005;124:198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassim B, Mody G, Bhoola KD. Kallikrein cascade and cytokines in inflammed joints. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;94:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00166-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalona WJ, Besser JA, Smith DS. Serum free prostate specific antigen and prostate specific antigen measurements for predicting cancer in men with prior negative prostatic biopsies. The Journal of Urology Volume. 1997;158:2162–2167. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements JA. The glandular kallikrein family of enzymes: tissue-specific expression and hormonal regulation. Endocr. Rev. 1989;10:393–419. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-4-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements JA. The molecular biology of the kallikreins and their roles in inflammation. In: Farmer SG, editor. The Kinin System. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. pp. 71–97. [Google Scholar]

- Diamandis EP, Yousef GM. Human tissue kallikrein gene family: a rich source of novel disease biomarkers. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2001;1:182–190. doi: 10.1586/14737159.1.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamandis EP, Yousef GM, Luo LY, Magklara A, Obiezu CV. The new human kallikrein gene family: implications in carcinogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomis-Ruth FX, Bayes A, Sotiropoulou G, Pampalakis G, Tsetsenis T, Villegas V, Aviles FX, Coll M. The structure of human prokallikrein 6 reveals a novel activation mechanism for the kallikrein family. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27273–27281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201534200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Mikolajczyk SD, Goel AS, Millar LS, Saedi MS. Expression of pro-form of prostate-specific antigen by mammalian cells and its conversion to mature, active form by human kallikrein 2. Cancer Research. 1997;57:3111–3114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano E, Pendas AM, Knäuper V, Sorsa T, Salo T, Salido E, Murphy G, Simmer JP, Bartlett JD, Lopez-Otin C. Identification and structural and functional characterization of human enamelysin. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15101–15108. doi: 10.1021/bi972120y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovgren J, Rajakoski K, Karp M, Lundwall A, Lilja H. Activation of the zymogen form of prostate-specific antigen by human glandular kallikrein 2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1997;238:549–555. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Papagerakis P, Yamakoshi Y, Hu JC, Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. Functions of KLK4 and MMP-20 in dental enamel formation. Biol. Chem. 2008;389:695–700. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luderer A, Chen Y-T, Soraino TF, Kramp WJ, Carlson G, Cuny C, Sharp T, Smith W, Petteway J, Brawer KM, Thiel R. Measurement of the proportion of free to total prostate specific antigen improves diagnostic performance of prostate-specific antigen in the diagnostic gray zone of the total prostate specific antigen. Urology. 1995;46:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstrom A, Egelrud T. Stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme: a proteinase which may be generally present in the stratum corneum and with a possible involvement in desquamation. Acta. Derm. Venereol. 1991;71:471–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm J, Hellman J, Hogg P, Lilja H. Enzymatic action of prostate-specific antigen (PSA or hK3): substrate specificity and regulation by Zn2+, a tight-binding inhibitor. Prostate. 2000;45:132–139. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20001001)45:2<132::aid-pros7>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolius HS. Kallikreins, kinins and cardiovascular diseases: a short review. Biological Research. 1998;31:135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael IP, Pampalakis G, Mikolajczyk SD, Malm J, Sotiropoulou G, Diamandis EP. Human tissue kallikrein 5 (hK5) is a member of a proteolytic cascade pathway involved in seminal clot liquefaction and potentially in prostate cancer progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:12743–12750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano T, Kakegawa A, Yamakoshi Y, Tsuchiya S, Hu JC-C, Gomi K, Arai T, Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. Mmp-20 and Klk4 cleavage site preferences for amelogenin sequences. J. Dent. Res. 2009;88:823–828. doi: 10.1177/0022034509342694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinase and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampalakis G, Sotiropoulou G. Tissue kallikrein proteolytic cascade pathways in normal physiology and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1776:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettus JR, Johnson JJ, Shi Z, Davis JW, Koblinski J, Ghosh S, Liu Y, Ravosa MJ, Frazier S, Stack MS. Multiple kallikrein (KLK 5, 7, 8, and 10) expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Histol. Histophathol. 2009;24:197–207. doi: 10.14670/hh-24.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu OH, Fincham AG, Hu C-C, Zhang C, Qian Q, Bartlett JD, Simmer JP. Characterization of recombinant pig enamelysin activity and cleavage of recombinant pig and mouse amelogenins. J. Dent. Res. 1999;78:743–750. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Blaber SI, Tingling JT, Rodriguez M, Blaber M, Christophi GP. Potential scope of action of tissue kallikreins in CNS immune-mediated disease. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2006;178:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarisbrick IA, Linbo R, Vandell AG, Keegan M, Blaber SI, Blaber M, Sneve D, Lucchinetti CF, Rodriguez M, Diamandis EP. Kallikreins are associated with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis and promote neurodegeneration. Biol.Chem. 2008;389:739–745. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine S, Takata T, Shibata T, Mori M, Morishita Y, Noguchi M, Uchida T, Kanai Y, Hirohashi S. Expression of enamel proteins and LEF1 in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma: evidence for its odontogenic epithelial differentiation. Histopathology. 2004;45:573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JLV, Diamandis EP. Distribution of 15 human kallikreins in tissues and biological fluids. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1423–1432. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.088104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiropoulou G, Rogakos V, Tsetsenis T, Pampalakis G, Zafiropoulos N, Simillides G, Yiotakis A, Diamandis EP. Emerging interest in the kallikrein gene family for understanding and diagnosing cancer. Oncol. Res. 2003;13:381–391. doi: 10.3727/096504003108748393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamey TA, Yang N, Hay AR, McNal JE, Freiha FS, Redwine E. Prostate-specific antigen as a serum marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987;15:909–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710083171501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke JO, Fosang AJ, Last K, Mercuri FA, Pendas AM, Llano E, Perris R, Di Cesare PE, Murphy G, Knäuper V. Matrix metalloproteinase 19 and 20 cleave aggrecan and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP). FEBS Lett. 2000;478:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01819-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata T, Zhao M, Uchida T, Wang T, Aoki T, Bartlett JD, Nikai H. Immunohistochemical detection and distribution of Enamelysin (MMP-20) in human odontogenic tumors. J. Dent. Res. 2000;79:1608–1613. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790081401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama TK, Fujikawa K, Davie EW. Characterization of the precursor of prostate-specific antigen. Activation by trypsin and by human glandular kallikrein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21582–21588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk BE, Lee DH, Yamakoshi Y, Klingenhoff A, Reichenberger E, Wright JT, Simmer JP, Komisarof JA, Cantley LC, Bartlett JD. MMP-20 is predominantly a tooth-specific enzyme with a deep catalytic pocket that hydrolyzes type V collagen. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3863–3874. doi: 10.1021/bi052252o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaananen A, Srinivas R, Parikka M, Palosaari H, Bartlett JD, Iwata K, Grenman R, Stenman U-H, Sorsa T, Salo T. Expression and regulation of MMP-20 in Human tongue carcinoma cells. J. Dent. Res. 2001;80:1884–1889. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaananen A, Tjaderhane L, Eklund L, Heljasvaara R, Pihlajaniemi T, Herva R, Ding Y, Bartlett JD, Salo T. Expression of collagen XVIII and MMP-20 in developing teeth and odontogenic tumors. Matrix Biology. 2004;23:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisanen V, Lovgren J, Hellman J, Piironen T, Lilja H, Pettersson K. Characterization and processing of prostate specific antigen (hK3) and human glandular kallikrein (hK2) secreted by LNCaP cells. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 1999;2:91–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lint P, Libert C. Chemokine and cytokine processing by matrix metalloproteinases and its effect on leukocyte migration and inflammation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2007;82:1375–1381. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Blaber SI, Debela M, Goettig P, I.A. S, M. B. A completed KLK activome profile: investigation of activation profiles of KLK9, 10 and 15. Biol. Chem. 2009;390:373–377. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Blaber SI, Evans DM, Trim J, Juliano MA, I.A. S, M. B. Activation profiles of human Kallikrein-related peptidases by proteases of the thrombostasis axis. Prot. Sci. 2008;17:1998–2007. doi: 10.1110/ps.036715.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Laxmikanthan G, Lee J, Blaber SI, Rodriguez A, Kogot JM, I.A. S, M. B. Activation profiles and regulatory cascades of the human kallikrein-related proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:31852–31864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousef GM, Diamandis EP. The new human tissue kallikrein gene family: structure, function, and association to disease. Endocr. Rev. 2001;22:184–204. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.