Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most common tumor in women with Li Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS), an inherited cancer syndrome associated with germline mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene. Their lifetime breast cancer risk is 49% by age 60. Breast cancers in TP53 carriers have recently been reported to more often be hormone receptor and HER-2 positive by immunohistochemistry and FISH in small series. We seek to expand this small literature with this report of a histopathologic analysis of breast cancers from women with documented LFS.

Methods

Unstained slides and paraffin-embedded tumor blocks from breast cancers from 39 germline TP53 mutations carriers were assembled from investigators in the LFS consortium. Central histology review was performed on 93% of the specimens by a single breast pathologist from a major university hospital. Histology, grade and hormone receptor status was assessed by immunohistochemistry; HER-2 status was defined by immunohistochemistry and/or FISH.

Results

The 43 tumors from 39 women comprise 32 invasive ductal carcinomas and 11 ductal carcinomas in situ (DCIS). No other histologies were observed. The median age at diagnosis was 32 years (range 22–46). Of the invasive cancers, 84% were positive for ER and/or PR; 81% were high grade. Sixty three percent of invasive and 73% of in situ carcinomas were positive for Her2/neu (IHC 3+ or FISH amplified). Of the invasive tumors, 53% were positive for both ER, and HER2+; other ER/PR/HER2 combinations were observed. The DCIS were positive for ER and HER2 in 27% of the cases.

Conclusions

This report of the phenotype of breast cancers from women with Li Fraumeni syndrome nearly doubles the literature on this topic. Most DCIS and invasive ductal carcinomas in Li Fraumeni syndrome are hormone receptor positive and/or HER-2 positive. These findings suggest that modern treatments may improve outcomes for women with LFS-associated breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Li Fraumeni Syndrome, TP53 mutations, HER2, hormone receptors

Introduction

Early onset breast cancer is one of the component tumors of the rare autosomal dominant hereditary cancer syndrome, Li Fraumeni Syndrome. The syndrome also features soft tissue and bone sarcomas, brain tumors, leukemias, and adrenal cortical carcinomas and a wide spectrum of other malignancies, predominantly in childhood and early adult life [1, 2]. Germline mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene (tumor protein p53, chromosome 17p13; OMIM 191170) are identified in 70% to 90% of families meeting classic criteria for LFS [3, 4]. Breast cancer is the most common tumor among women with germline TP53 mutations. The risk of breast cancer in women with LFS is approximately 49% by age 60, with significant risk before age 40 [5]. The frequency of TP53 mutations in population-based series of young onset breast cancers (age <30 years at diagnosis) ranges from <1% to approximately 7% [6–8].

Microarray analysis has shown distinctions among breast cancer subtypes [9, 10]. In addition, breast cancers occurring in individuals with specific hereditary predisposition syndromes have been shown to cluster by subtype. For example, the majority of BRCA1-associated breast cancers share the gene expression profile of sporadic basal-like tumors (ER negative, PR negative, HER-2 negative) [10, 9]. In contrast, BRCA2-associated breast cancers are predominantly estrogen and progesterone receptor positive and HER-2 negative [11]. Recent reports suggest that breast cancers in women with LFS are both hormone receptor and HER2/neu – positive [12–14].

Given the rarity of Li Fraumeni syndrome, an international consortium of academic cancer genetics programs has been formed with the goal of providing clinical care and research participation to adults and children with LFS. Consortium investigators pooled their paraffinembedded breast cancer specimens from women with TP53 mutations to better characterize the features of malignant breast tumors in the context of LFS.

Materials and Methods

Forty-three paraffin-embedded tumor blocks or unstained slides from invasive and in situ breast cancers from women with a known TP53 mutation were identified by investigators from the City of Hope, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Stanford University, University of Michigan, University of Texas Southwestern and Hospital Vall d’Hebron, in Barcelona, Spain.

Clinical data, family history information and mutation status on these women had been collected under institution-specific institutional review board-approved protocols: individual identifiers were not shared. Review of histology and determination of estrogen and progesterone receptors by immunohistochemistry and HER2 status by immunohistochemistry and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were performed on 93% of the specimens by a single breast pathologist from a major university hospital (DD from BWH). Histopathologic description and ER, PR and HER2/neu status from 4 cases from one pathology department (BWH) without tissue available for confirmation was accepted by pathology report only, as all breast cases at BWH are reviewed by an expert breast pathologist.

Histologic analysis

For 93% of the cases at least one H&E slide was available for central review by an expert breast pathologist. Invasive carcinoma was classified as ductal, lobular, or mixed ductal and lobular according to standard criteria and graded using a modified Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grading system [15]. Cases with only ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) were classified according to nuclear grade (high, intermediate or low). Areas appropriate for coring were marked for tissue microarray (TMA) construction.

Tissue microarray construction

TMAs were constructed in the Dana Farber Harvard Cancer Center Tissue Microarray Core Facility from cases with available formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded archival tissue blocks. Three 0.6 mm cores from cases of invasive carcinoma and four to six cores from cases of DCIS were taken from marked areas and placed into a recipient block using a manual arrayer (Beecher Instruments). Representative cores of normal breast epithelium were included.

Immunohistochemistry for ER, PR and Her2/neu

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-µm tissue sections (TMA sections and whole slide sections) using EnVision+ System-HRP (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Briefly, slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated and endogenous peroxidase activity blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Antigen retrieval was performed using 10mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 (Target Retrieval Solution, S1699, DAKO) and pressure cooking (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) at 122°C (14 and 17 psi) for 45 minutes. Primary antibodies for estrogen receptor (SP1, 1:200; Lab Vision, Fremont, CA), progesterone receptor (PgR636, 1:200; DAKO) and Her2/neu (SP3 1:100; Labvision, Fremont, CA) were incubated for 40 minutes at room temperature. A DAKO polymer secondary antibodysystem was used (Envision Poly K4011 for the SP1 RabMab and Envision Mono K4007 for PR MMab) and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes in a humid chamber. 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) was used for detection as with counterstaining using Mayer hematoxylin. External positive controls were included with each run.

Slides were scored by a breast pathologist (DD) as positive (greater than or = 1% tumor nuclei staining) or negative (less than 1%) for ER and PR according to ASCO/CAP guidelines [16]. Immunohistochemistry for Her2/neu was scored as positive 3+ (strong complete membrane immunoreactivity in >30% of tumor cells), equivocal 2+ (weak to moderate complete membrane immunoreactivity in at least 10% of tumor cells), negative 1+ (faint, weak partial membrane immunoreactivity in at least 10% of tumor cells) and negative 0 (no immunoreactivity or immunoreactivity in <10% of tumor cells) according to ASCO/CAP guidelines [17].

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

Bacterial artificial chromosome clones RP11-62N23, RP11-1065L22 and RP11-1044P23 were obtained from Children’s Hospital, Oakland and used in construction of FISH probes for a 340kb region including ERBB2. Probes were biotin-labeled using the Random Prime DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and detected with rhodamine (red). FITC-labeled probe to the chromosome 17 centromeric region was purchased from Abbott/Vysis. Specificity of probe binding was verified using normal lymphocyte metaphase spreads.

Dual color FISH was performed on TMA and whole tissue sections. Slides were counterstained with DAPI/Antifade (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and evaluated using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope. Hybridization signals were scored in at least 20 tumor cells according to ASCO/CAP guidelines. A ratio of HER2 probe signals to centromere probe signals was calculated, with a ratio of >2.2 reported as amplified and a ratio of <1.8 as not amplified.

Results

Forty-three specimens from 39 women with confirmed germline TP53 mutations included 32 invasive ductal carcinomas and 11 DCIS. Two women had both DCIS and invasive carcinomas and 2 had bilateral invasive breast cancers. The median age at diagnosis of invasive breast cancer was 32 years (range 22–60 years); it was 34 years for DCIS (range 22–40 years) (Table 1). All women in the cohort were carriers of confirmed deleterious TP53 mutations.

Table 1.

Characteristics of breast cancers in women with germline TP53 mutations.

| DCIS (%) n=11 |

IDC (%) n=32 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis | 34 | 32 |

| Range | 22–40 | 22–60 |

| Histology | ||

| DCIS | 8 | - |

| DCIS/Microinvasion | 3 | - |

| IDC | - | 31 |

| ILC | - | - |

| IDLC | - | 1 |

| Grade | ||

| High Nuclear Grade | 11 | - |

| I | - | 1 |

| II | - | 5 |

| III | - | 26 |

| TNM | ||

| Tis | 7 | - |

| T1 | - | 15 |

| T2 | - | 10 |

| N0 | 6 | 10 |

| N1 | 2 | 10 |

| N2 | - | - |

| N3 | - | 1 |

| N/A | 3 | 11 |

| ER | ||

| ER+ | 6 | 27 |

| ER− | 5 | 5 |

| PR | ||

| PR+ | 6 | 23 |

| PR− | 5 | 9 |

| HER2 | ||

| HER2+ | 8 | 20 |

| HER2− | 3 | 12 |

IDC: invasive ductal carcinoma; ILC: invasive lobular Carcinoma; IDLC: invasive ductal/lobular carcinoma.

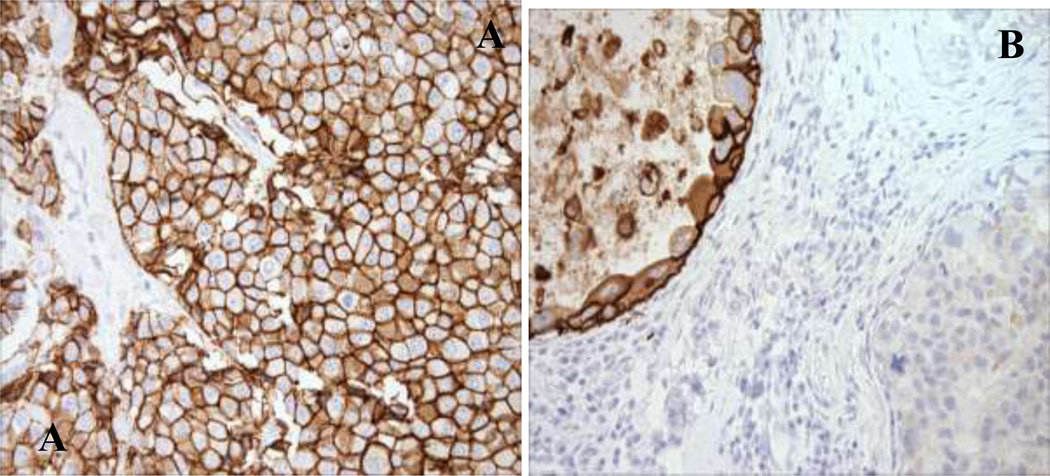

Thirty of 39 women reported family cancer histories that meet the 2009 Chompret criteria for LFS [18] (Table 2). One or more additional primary malignancies were reported among 27 women of which 21 were tumors considered components of LFS. Eleven women had had a primary cancer prior to their breast cancer diagnosis, of which five were childhood tumors. High nuclear grade was observed in 26 (81%) of the invasive carcinomas and all DCIS cases. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that 27 (84%) of the invasive cancers stained positive for ER and 23 (72%) for PR; 6 (55%) of the DCIS stained positive for ER and PR. HER-2 was positive by IHC and/or FISH in 63% of invasive and 73% of in situ carcinomas respectively. Among the tumors in this cohort, the most common immunophenotype was ER+/HER2+, present in 53% of invasive carcinomas and 27 % of DCIS (Table 3). Of note, we found one DCIS specimen with a heterogeneous pattern characterized by adjacent areas of HER2 positivity and negativity (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Fulfillment of clinical criteria for Li-Fraumeni syndrome and description of additional primary cancers in women with germline TP53 mutations and breast cancer.

| Criteria | N=39 |

|---|---|

| Classic LFS Criteria | 10 |

| Chompret Criteria | 30 |

| Additional primary tumors | 36 |

| Adrenal Cortical Carcinoma | 2 |

| Breast Carcinoma | 5 |

| Central Nervous System Tumor | 1 |

| Lung Carcinoma | 2 |

| Sarcoma | 14 |

| Thyroid Carcinoma | 5 |

| Other Malignancies | 7 |

Table 3.

Joint ER and HER2 status of the tumors in the cohort

| N | ER+/HER2+ | ER−/HER2+ | ER+/HER2- | ER−/HER2- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCIS | 11 | 3 | 5 | 3 | - |

| IDC | 32 | 17 | 3 | 10 | 2 |

| Total | 43 | 20 (47%) | 8 (19%) | 13 (30%) | 2 (5%) |

Figure 1.

A: Representative sections with immunohistochemical stains for Her2/neu in invasive ductal carcinoma in case 1, showing the strong complete membrane immunoreactivity (3+ pattern) characteristic of HER2-amplified tumors; B: Representative immunohistochemical stain for Her2/neu in case 2 showing heterogeneity of DCIS. HER2+ DCIS is seen in the upper left and HER2- DCIS is seen in the lower right. Of interest, patient 2 also had a HER2- invasive ductal cancer (not shown).

Discussion

In our series of 43 tumors in 39 women with TP53 mutations we found that 63% of the invasive breast cancers and 73% of DCIS were positive for HER2, and more than three quarters of the tumors were positive for ER. The concurrent expression of the estrogen receptors and HER-2 was present in 49% of the samples. Similar to other LFS series, the age at diagnosis of breast cancer in LFS was much younger than in the general population in the United States (median age at diagnosis at 32 years versus 61 years, p<0.0001) [19].

Our study represents the largest cohort of breast cancer in LFS reported to date and adds to the recently published data on the clinical pathological features of breast cancers in TP53 mutation carriers. The rarity of LFS makes it difficult to assemble large series of tumors for analysis. Our results confirm the finding that breast tumors in LFS are predominantly – but not exclusively – hormone receptor and HER-2 positive.

The histopathologic profile of breast tumors in women with germline TP53 mutations has been recently characterized in two other cohorts. In the initial observation, Wilson et al. found that breast cancers in 9 TP53-mutation carriers in a clinical-based series from one UK regional genetics service are more likely to be HER-2 positive (83%) compared to 16% in a reference panel of 231 young onset breast tumors of women diagnosed age aged ≤ 30 years participating in the Prospective Study of Outcomes in Sporadic versus Hereditary Breast Cancer study (POSH) [12]. A group from MD Anderson Cancer Center and the University of Chicago confirmed these findings in their analysis of specimens from their cohort of 30 TP53 mutation positive patients, with 70% positive for estrogen receptor and 67% showing HER-2 over-expression and/or amplification in comparison to 68% of ER positive and 25% of HER-2 positive in the control group of TP53 mutation negative patients [14].

The HER-2 gene is amplified in 15–25% of invasive breast cancers. In cohorts of young women (age < 40) with breast cancer unselected for family history, 52–66% of tumors were estrogen receptor positive and 22–33% HER2 positive [20–22]. Among women in our cohort diagnosed before age 40, 75% of tumors were estrogen receptor positive and 72% HER2 positive.

In our paper, the data demonstrate that breast cancers arising in individuals with germline TP53 mutations have a predominant immunohistochemical profile that correlates with molecular phenotype. The subtype differs from those observed in breast cancers arising in other hereditary predisposition syndromes. Breast cancers arising in BRCA1 mutation carriers are predominantly basal-like by microarray; 80% of breast cancers in women with germline BRCA2 mutations are ER+ and HER2 negative. In women with CDH1 mutations (Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer Syndrome), the breast tumors have invasive lobular histology [23]. TP53 abnormalities have been detected in sporadic HER2+ breast carcinomas [24]. It is notable that BRCA1-associated basal-like tumors are frequently TP53 mutant [25]. Tumors arising in LFS are also TP53 mutated, but whether loss of the second allele is an early event is not known [26]. The data raise questions about biologic mechanisms underlying the diversity of tumor types, among which differences in cell-of-origin, order of mutation acquisition and epigenetic influences are candidates.

These findings may have important clinical implications for women with LFS. Over-expression of HER-2 has been associated with an aggressive phenotype which includes poorly differentiated and high-grade tumors, high rates of cell proliferation, lymph-node involvement, and resistance to certain types of hormonal and chemotherapies [27, 28]. In contrast, the outcome for women with HER2-positive tumors has improved markedly in the era of HER2-targeted therapies [29]. It remains to be shown that women with LFS-associated HER2 positive tumors benefit to same extent as do women with sporadic HER2-positive tumors; the prevalence of women with TP53 mutations among the clinical trial cohorts should be very low. In addition, it would be interesting to know the prevalence of TP53 mutations among young women with HER2+ breast cancer which may lead to consideration for TP53 testing in young patients with this breast cancer subtype.

In conclusion, our results confirm the finding that breast cancers developing in individuals with germline TP53 mutations often feature a hormone receptor positive, HER2 positive subtype. Further research is needed to understand the biology driving this observation.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of the Dana Farber Harvard Cancer Center Specialized Histopathology Core Laboratory, particularly Teri Bowman and Donna Skinner for assistance with slide preparation, as well as Chungdak Namgyal for construction of the tissue microarray, Mei Zheng for immunohistochemistry and Krishan Taneja for fluorescence in situ hybridization. Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center is supported in part by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant # NIH 5 P30 CA06516. This research is supported in part by the Dana-Farber/Harvard SPORE in Breast Cancer (CA 89393). The City of Hope Clinical Cancer Genetics Community Research Network is supported in part by Award Number RC4A153828 (PI: JN Weitzel) from the National Cancer Institute and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health. Supported by NCI P30 CA014089-37 (S. Gruber). Partially funded by a Hellenic Society of Medical Oncology (HeSMO) scholarship (G. Lypas).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Li FP, Fraumeni JF., Jr Soft-tissue sarcomas, breast cancer, and other neoplasms. A familial syndrome? Ann Intern Med. 1969;71(4):747–752. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-71-4-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Mulvihill JJ, Blattner WA, Dreyfus MG, Tucker MA, Miller RW. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988;48(18):5358–5362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA, et al. Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990;250(4985):1233–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1978757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varley JM, Evans DG, Birch JM. Li-Fraumeni syndrome--a molecular and clinical review. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang SJ, Lozano G, Amos CI, Strong LC. Germline p53 mutations in a cohort with childhood sarcoma: sex differences in cancer risk. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(4):975–983. doi: 10.1086/374567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lalloo F, Varley J, Moran A, Ellis D, O'Dair L, Pharoah P, Antoniou A, Hartley R, Shenton A, Seal S, Bulman B, Howell A, Evans DG. BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 mutations in very early-onset breast cancer with associated risks to relatives. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(8):1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mouchawar J, Korch C, Byers T, Pitts TM, Li E, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Hopper JL, Southey MC. Population-based estimate of the contribution of TP53 mutations to subgroups of early-onset breast cancer: Australian Breast Cancer Family Study. Cancer Res. 70(12):4795–4800. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez KD, Noltner KA, Buzin CH, Gu D, Wen-Fong CY, Nguyen VQ, Han JH, Lowstuter K, Longmate J, Sommer SS, Weitzel JN. Beyond Li Fraumeni Syndrome: clinical characteristics of families with p53 germline mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1250–1256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedenfalk I, Duggan D, Chen Y, Radmacher M, Bittner M, Simon R, Meltzer P, Gusterson B, Esteller M, Kallioniemi OP, Wilfond B, Borg A, Trent J, Raffeld M, Yakhini Z, Ben-Dor A, Dougherty E, Kononen J, Bubendorf L, Fehrle W, Pittaluga S, Gruvberger S, Loman N, Johannsson O, Olsson H, Sauter G. Gene-expression profiles in hereditary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(8):539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102223440801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, Deng S, Johnsen H, Pesich R, Geisler S, Demeter J, Perou CM, Lonning PE, Brown PO, Borresen-Dale AL, Botstein D. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakhani SR, Van De Vijver MJ, Jacquemier J, Anderson TJ, Osin PP, McGuffog L, Easton DF. The pathology of familial breast cancer: predictive value of immunohistochemical markers estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER-2, and p53 in patients with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(9):2310–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JR, Bateman AC, Hanson H, An Q, Evans G, Rahman N, Jones JL, Eccles DM. A novel HER2-positive breast cancer phenotype arising from germline TP53 mutations. J Med Genet. 2010;47(11):771–774. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.078113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masciari SKM, Digianni L, Dillon D, Li F, Garber JE. Histopathological features of breast cancers in women with germline TP53 mutations. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2006 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. 2006 Jun 20;vol 18S(Supplement):10031. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melhem-Bertrandt A, Bojadzieva J, Ready KJ, Obeid E, Liu DD, Gutierrez-Barrera AM, Litton JK, Olopade OI, Hortobagyi GN, Strong LC, Arun BK. Early onset HER2-positive breast cancer is associated with germline TP53 mutations. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. I. The value of histological grade in breast cancer: experience from a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1991;19(5):403–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Wolff AC, Mangu PB, Temin S. American society of clinical oncology/college of american pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 6(4):195–197. doi: 10.1200/JOP.777003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, Hagerty KL, Allred DC, Cote RJ, Dowsett M, Fitzgibbons PL, Hanna WM, Langer A, McShane LM, Paik S, Pegram MD, Perez EA, Press MF, Rhodes A, Sturgeon C, Taube SE, Tubbs R, Vance GH, van de Vijver M, Wheeler TM, Hayes DF. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(1):118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinat J, Bougeard G, Baert-Desurmont S, Vasseur S, Martin C, Bouvignies E, Caron O, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Berthet P, Dugast C, Bonaiti-Pellie C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Frebourg T. 2009 version of the Chompret criteria for Li Fraumeni syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):e108–e109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7967. author reply e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2008. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2011. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins LC, Marotti JD, Gelber S, Cole K, Ruddy K, Kereakoglow S, Brachtel EF, Schapira L, Come SE, Winer EP, Partridge AH. Pathologic features and molecular phenotype by patient age in a large cohort of young women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1872-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker RA, Lees E, Webb MB, Dearing SJ. Breast carcinomas occurring in young women (< 35 years) are different. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(11):1796–1800. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Broglio K, Kau SW, Eralp Y, Erlichman J, Valero V, Theriault R, Booser D, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN, Arun B. Women age< or = 35 years with primary breast carcinoma: disease features at presentation. Cancer. 2005;103(12):2466–2472. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaurah P, MacMillan A, Boyd N, Senz J, De Luca A, Chun N, Suriano G, Zaor S, Van Manen L, Gilpin C, Nikkel S, Connolly-Wilson M, Weissman S, Rubinstein WS, Sebold C, Greenstein R, Stroop J, Yim D, Panzini B, McKinnon W, Greenblatt M, Wirtzfeld D, Fontaine D, Coit D, Yoon S, Chung D, Lauwers G, Pizzuti A, Vaccaro C, Redal MA, Oliveira C, Tischkowitz M, Olschwang S, Gallinger S, Lynch H, Green J, Ford J, Pharoah P, Fernandez B, Huntsman D. Founder and recurrent CDH1 mutations in families with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Jama. 2007;297(21):2360–2372. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.21.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eyfjord JE, Thorlacius S, Steinarsdottir M, Valgardsdottir R, Ogmundsdottir HM, Anamthawat-Jonsson K. p53 abnormalities and genomic instability in primary human breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1995;55(3):646–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manie E, Vincent-Salomon A, Lehmann-Che J, Pierron G, Turpin E, Warcoin M, Gruel N, Lebigot I, Sastre-Garau X, Lidereau R, Remenieras A, Feunteun J, Delattre O, de The H, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Stern MH. High frequency of TP53 mutation in BRCA1 and sporadic basal-like carcinomas but not in BRCA1 luminal breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2009;69(2):663–671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borresen AL, Andersen TI, Garber J, Barbier-Piraux N, Thorlacius S, Eyfjord J, Ottestad L, Smith-Sorensen B, Hovig E, Malkin D, et al. Screening for germ line TP53 mutations in breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1992;52(11):3234–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burstein HJ. The distinctive nature of HER2-positive breast cancers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1652–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, Pienkowski T, Martin M, Press M, Mackey J, Glaspy J, Chan A, Pawlicki M, Pinter T, Valero V, Liu MC, Sauter G, von Minckwitz G, Visco F, Bee V, Buyse M, Bendahmane B, Tabah-Fisch I, Lindsay MA, Riva A, Crown J. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 365(14):1273–1283. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]