Abstract

Bats are reservoirs for a wide range of human pathogens including Nipah, Hendra, rabies, Ebola, Marburg and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (CoV). The recent implication of a novel beta (β)-CoV as the cause of fatal respiratory disease in the Middle East emphasizes the importance of surveillance for CoVs that have potential to move from bats into the human population. In a screen of 606 bats from 42 different species in Campeche, Chiapas and Mexico City we identified 13 distinct CoVs. Nine were alpha (α)-CoVs; four were β-CoVs. Twelve were novel. Analyses of these viruses in the context of their hosts and ecological habitat indicated that host species is a strong selective driver in CoV evolution, even in allopatric populations separated by significant geographical distance; and that a single species/genus of bat can contain multiple CoVs. A β-CoV with 96.5 % amino acid identity to the β-CoV associated with human disease in the Middle East was found in a Nyctinomops laticaudatus bat, suggesting that efforts to identify the viral reservoir should include surveillance of the bat families Molossidae/Vespertilionidae, or the closely related Nycteridae/Emballonuridae. While it is important to investigate unknown viral diversity in bats, it is also important to remember that the majority of viruses they carry will not pose any clinical risk, and bats should not be stigmatized ubiquitously as significant threats to public health.

Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs), in the subfamily Coronavirinae, are enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses with spherical virions of 120–160 nm (King et al., 2012). They are among the largest RNA viruses, with complex polyadenylated genomes of 26–32 kb, and are divided into four genera: Alphacoronavirus (α-CoV) and Betacoronavirus (β-CoV) (infecting mainly mammals), and Gammacoronavirus (γ-CoV) and Deltacoronavirus (δ-CoV) (infecting mainly birds) (King et al., 2012; Woo et al., 2012). Infection with CoVs is often asymptomatic, however, they can be responsible for a range of respiratory and enteric diseases of medical and veterinary importance. Chief among these is the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV, which caused a pandemic in 2002–2003. This outbreak lasted for 8 months, infected 8096 people and resulted in 774 deaths (WHO, 2004). Since then, a renewed public health interest in these viruses has been stimulated by the emergence of a novel β-CoV in nine people from the Middle East. In these cases the patients suffered from acute, serious respiratory illness, presenting with fever, cough, shortness of breath and difficulty breathing (Zaki et al., 2012). Five cases later died. It is currently unclear where this particular virus came from, though genomic analyses have shown similarity to bat CoVs (Zaki et al., 2012). Given that the majority of emerging pathogens are known to originate in animals (Jones et al., 2008), the concern is that this current outbreak may represent a further example of zoonotic transmission from wildlife to people, though further ecological, immunological and evolutionary information is still required to confirm this.

Knowledge about CoV diversity has increased significantly since the SARS pandemic, with the description of several novel viruses from a wide range of mammalian and avian hosts (Cavanagh, 2005; Chu et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2007; Felippe et al., 2010; Guan et al., 2003; Jackwood et al., 2012; Lau et al., 2012b; Woo et al., 2009a, b, 2012). Bats in particular seem to be important reservoirs for CoVs, and discovery efforts have been increasingly focused on them since the recognition of SARS-like CoVs in rhinolophid species (Lau et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005) and because bats appear to be reservoirs for a large number of other viruses (Calisher et al., 2006; Drexler et al., 2012; Jia et al., 2003; Leroy et al., 2005; Rahman et al., 2010; Towner et al., 2007). Several of the novel CoVs described in the last decade were identified in bats of various species and demonstrate a strong association between bats and CoVs (August et al., 2012; Carrington et al., 2008; Chu et al., 2009; Dominguez et al., 2007; Drexler et al., 2011, 2010; Falcón et al., 2011; Ge et al., 2012b; Gloza-Rausch et al., 2008; Li et al., 2005; Misra et al., 2009; Osborne et al., 2011; Pfefferle et al., 2009; Quan et al., 2010; Reusken et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2009b; Woo et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2010).

The large number of CoVs that continue to be described in bats suggest that many (if not most) bat species might be associated with at least one CoV. Given that there are ~1200 extant bat species known, the existence of an equally large diversity of CoVs must be considered likely. Initially, most discovery effort was targeted towards bats from China (Ge et al., 2012a; Lau et al., 2010b; Li et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2006; Woo et al., 2006), followed by limited surveillance in other South-east Asian countries including Japan, the Philippines and Thailand (Gouilh et al., 2011; Shirato et al., 2012; Watanabe et al., 2010). In the Old World, novel CoVs have been found in both Europe and Africa (August et al., 2012; Drexler et al., 2011, 2010; Gloza-Rausch et al., 2008; Pfefferle et al., 2009; Quan et al., 2010; Reusken et al., 2010; Rihtaric et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2009b).

In contrast, very few investigations have been conducted in the New World and little is known about the diversity of CoVs found here. Dominguez et al. (2007) were the first to test bats in the New World for CoV, followed by Donaldson et al. (2010) and Osborne et al. (2011). These groups tested bats captured in Colorado and Maryland and found α-CoVs from five different species of evening bats (Eptesicus fuscus, Myotis evotis, Myotis lucifugus, Myotis occultus and Myotis volans). All were unique compared with CoVs found in Asia. Misra et al. (2009) then tested M. lucifugus samples from Canada and detected a similar α-CoV to those found in myotis bats from Colorado. In South America, Carrington et al. (2008) identified an α-CoV in two species of leaf-nosed bats, Carollia perspicillata and Glossophaga soricina, which clustered most closely with CoVs from North American and European bats.

Nothing is known about the diversity of CoVs in Mexico. Many of the bats studied in Canada and the USA are also found in Mexico, yet it is unknown whether similar viruses are found here. It is also unknown whether β-CoVs exist in the Americas, or whether the α-CoVs predominate. This is a substantive gap in our knowledge of CoV ecology because one-third of all bat species (and 75 % of all known bat genera) are found in the neotropics, which includes southern Mexico (Osborne et al., 2011; Wilson & Reeder, 2005). It seems probable that the high ecological, trophic and taxonomic diversity found in Neotropical and Nearctic bats in Mexico (Arita & Ortega, 1998) would be matched by an equally diverse population of novel CoVs. In this study we examined 42 species of bats using broadly reactive consensus PCR for the discovery of novel CoVs, and found an additional 13 viral lineages/clades, clustering in both the α-CoV and the β-CoV genera. Phylogenetic analysis of these new viruses has provided insight into the molecular epidemiology of CoVs, and shows that host speciation is a significant driver in CoV evolution.

Results and Discussion

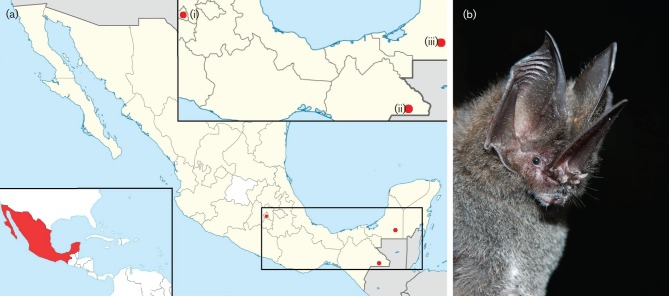

The goal of this study was to increase our knowledge of CoV diversity in bats from southern Mexico. Three sites were included in the study: Campeche, Chiapas and Mexico City (Mexico Distrito Federal; D.F.) (Fig. 1). At two of the sites (Chiapas and Campeche) bats were captured in disturbed and undisturbed habitat to investigate how anthropogenic activity may affect host and viral diversity. Such habitat gradients do not exist in D.F., which is a highly urbanized site. A total of 1046 samples were collected from 606 individuals, of 42 different bat species (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

(a) Map of sampling sites, (i) D.F., Mexico City, (ii) Reserva de la Biosfera Montes Azules, Chiapas, (iii) the Reserva de la Biosfera Calakmul, Campeche. (b) CoV-positive bat, species Lonchorhina aurita. This individual (PMX-505) was positive for the novel α-CoV Mex_CoV-3.

Table 1. Summary of all bats captured at each site.

A total of 606 bats were sampled across three sites. The number of CoV PCR positives (Pos) are indicated in parentheses, together with the number of CoV clades in square brackets. All bat species captured are endemic to the Americas.

| Family | Species | Trophic guild | Campeche | Chiapas | D.F. | Total | ||

| (# CoV PCR Pos)/[CoV clade(s)] | (# CoV PCR Pos)/[# CoV clade(s)] | |||||||

| Undisturbed | Disturbed | Undisturbed | Disturbed | Urban | ||||

| Phyllostomidae | Artibeus lituratus | Frugivorous | 26 (4) [5b, 11b] | 28 (1) [11a] | 16 | 38 | 108 | |

| Artibeus phaeotis | Frugivorous | 21 (1) [11b] | 3 | 3 (2) [11a, 11b] | 9 | 36 | ||

| Artibeus jamaicensis | Frugivorous | 33 (2) [5b] | 23 (1) [4] | 17 (2) [5a] | 20 | 93 | ||

| Artibeus watsoni | Frugivorous | 5 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 17 | ||

| Glossophaga soricina | Nectivorous | 1 | 8 | 12 | 27 | 48 | ||

| Glossophaga commissarisi | Nectivorous | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Carollia sowelli | Frugivorous | 27 | 14 (4) [1, 2, 5b] | 11 (1) [;5a] | 20 (2) [1] | 72 | ||

| Carollia perspicillata | Frugivorous | 8 | 4 (2) [1] | 1 | 8 | 21 | ||

| Sturnira ludovici | Frugivorous | 7 | 16 | 23 | ||||

| Sturnira lilium | Frugivorous | 6 | 6 | 22 | 34 | |||

| Leptonycteris nivalis | Nectivorous | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Leptonycteris yerbabuenae | Nectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Centurio senex | Frugivorous | 1 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Platyrrhinus helleri | Frugivorous | 1 | 5 | 10 | 16 | |||

| Uroderma bilobatum | Frugivorous | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Desmodus rotundus | Haematophagous | 3 | 4 | 7 | ||||

| Micronycteris schmidtorum | Insectivorous | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||||

| Micronycteris microtis | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Mimon cozumelae | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Phyllostomus discolour | Frugivorous | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Choeroniscus godmani | Nectivorous | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Trachops cirrhosus | Carnivorous | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Tonatia saurophila | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Chrotopterus auritus | Carnivorous | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Lonchorhina aurita | Insectivorous | 1 (1) [3]* | 1 | |||||

| Phylloderma stenops | Frugivorous | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Mormoopidae | Mormoops megalohyla | Insectivorous | 9 | 2 | 11 | |||

| Pteronotus davyi | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Pteronotus parnellii | Insectivorous | 1 (1) [10] | 1 | 10 | 7 | 19 | ||

| Molossidae | Nyctinomops macrotis | Insectivorous | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Nyctinomops laticaudatus | Insectivorous | 5 (1) [9] | 5 | |||||

| Tadarida brasiliensis | Insectivorous | 10 (3) [8] | 10 | |||||

| Vespertilionidae | Myotis velifer | Insectivorous | 7 (3) [7] | 7 | ||||

| Myotis occultus | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Myotis keaysi | Insectivorous | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Myotis nigricans | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Eptesicus fuscus | Insectivorous | 1 (1) [6] | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Corynorhinus mexicanus | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Lasiurus intermedius | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Bauerus dubiaquercus | Insectivorous | 17 | 1 | 18 | ||||

| Emballonuridae | Rhynchonycteris naso | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Saccopteryx bilineata | Insectivorous | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total species/families | 13 [9, 10, 5b, 11b] | 13 [1, 2, 4, 5b, 11a] | 26 [3, 5a, 11a, 11b] | 22 [1, 6] | 8 [7, 8] | |||

| Total animals captured | 144 | 96 | 130 | 202 | 34 | 606 | ||

Individual PMX-505/Lonchorhina aurita (Fig. 1b).

Host (bat) diversity

Host diversity was examined at all sites. In Chiapas, a species richness of 32 was recorded, and the calculated Shannon–Wiener diversity index (H′) was 2.81 (Table 2). A comparison of undisturbed and disturbed habitat in Chiapas (Shannon t-test) revealed no significant difference in richness and diversity (P = 0.11). In Campeche the overall species richness was 16 and the diversity index H′ was 2.167 (Table 2). Again, no significant difference in host diversity was seen between the undisturbed and disturbed habitats (P = 0.44). Previous work has shown that bat diversity often reflects the level of disturbance for a given habitat, with lower diversity recorded in disturbed areas (Medellín et al., 2000). No such distinction was observed here between disturbed and undisturbed sites. This may reflect the dominance of bats from the genera Artibeus and Carollia (Table 1), both of which contain species that are known to be more adaptable and resistant to the effects of habitat fragmentation (Medellín et al., 2000). An increased sampling effort including larger spatial and temporal scales will be needed to assess whether the abundance and richness of less-well represented species alter the overall bat diversity in each fragment. In D.F. (Mexico City), eight species were captured and the diversity index H′ was 1.69 (Table 2). Sampling effort was not consistent among the three sites, precluding any direct comparisons of diversity between Chiapas, Campeche and D.F.

Table 2. Evaluations of host and viral diversity at each site/habitat using the Shannon diversity index.

This index takes into account the number of individuals as well as the number of taxa. A 0 value means that community has only a single taxon.

| Site | Habitat | Bat diversity | Viral diversity | ||||

| n | S (richness) | D (diversity) | n | S (richness) | D (diversity) | ||

| Chiapas | Undisturbed | 130 | 26 | 2.775 | 6 | 5 | 1.561 |

| Disturbed | 202 | 22 | 2.57 | 3 | 2 | 0.6365 | |

| Total | 332 | 32 | 2.81 | 9 | 6 | 1.735 | |

| Campeche | Undisturbed | 144 | 13 | 2.079 | 9 | 4 | 1.149 |

| Disturbed | 96 | 13 | 2.01 | 8 | 5 | 1.494 | |

| Total | 240 | 16 | 2.167 | 17 | 7 | 1.732 | |

| D.F. | Urban | 34 | 8 | 1.69 | 6 | 2 | 0.6931 |

| 606 | 42 | 32 | 13 | 606 | |||

CoV diversity

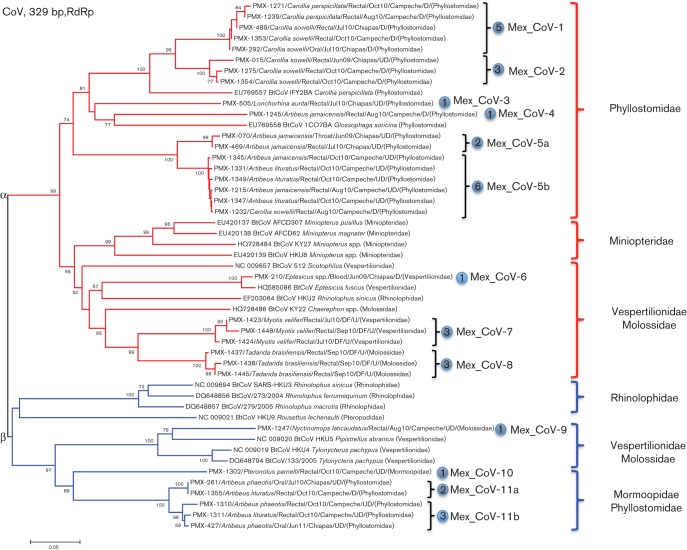

Broadly reactive consensus PCR revealed CoV sequences in 32/606 (5.3 %) bats (Table 1). Sequence analyses indicated high phylogenetic diversity and the presence of 13 distinct clades at the nucleotide level (Fig. 2). Clades 5a/5b and 11a/11b had high nucleotide sequence identity and collapsed into a single group when analysed at the amino acid level (data not shown). Nine of the viruses clustered with known α-CoVs, and four clustered with β-CoVs (Fig. 2). One of the α-CoVs (Mex_Cov-6) was closely related to a virus identified previously in an Eptesicus fuscus bat, sampled on the Appalachian Trail in Maryland, USA (Donaldson et al., 2010). We therefore extend the known geographical range of this virus to south-eastern Mexico and present the discovery of a further 12 novel CoVs.

Fig. 2.

Maximum-likelihood tree of a 329 bp fragment of the RdRp from bat CoVs only (red, α-CoVs; blue, β-CoVs). All 32 positive animals from this study are presented on the tree, and begin with a PMX number that refers to the animal identity. The species of all PMX animals was confirmed by Cyt-b (cytochrome b gene) barcoding. CoVs identified in this study split into 13 clades at the nucleotide level, though Mex_CoV-5a/b and Mex_CoV-11a/b collapse into single clades when analysed at the amino acid level. Each clade is indicated by a blue circle, and the total number of positive animals for each clade is indicated within. D, Disturbed habitat; UD, undisturbed habitat; U, urban habitat. Bar, 0.05 nucleotide substitutions per site.

Prior to this study, very little was known about the diversity of CoVs in the neotropics, despite the high diversity of bat species found here (Wilson & Reeder, 2005). Here, we demonstrate that several additional viruses from both the genus Alphacoronavirus and the genus Betacoronavirus exist in Mexico. This particular study was limited to the analysis of a 329 bp fragment of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), however, it was sufficient for the identification of these novel strains and therefore satisfied our primary goal of discovery.

CoV-positive sample types included 27 rectal swabs, four oral swabs and one blood sample (annotated on Fig. 2). The high number of positive rectal samples agrees with previous studies, which showed CoV detection in bats to be almost exclusively restricted to faeces (Lau et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Pfefferle et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2006). Detection in oral swabs has also been demonstrated, but much less frequently (Carrington et al., 2008).

Phylogenetic analyses of this short fragment show that CoVs cluster based on the relatedness of host species. Fig. 2 shows that all of the α-CoVs detected in phyllostomid bats cluster together; as do all α-CoVs discovered in miniopterid bats. The families Vespertilionidae and Molossidae are closely related (Agnarsson et al., 2011; Teeling et al., 2005), and viruses from these bats also cluster together, though the additional presence of CoV HKU2 (from a rhinolophid bat; Woo et al., 2006) in this group is currently unexplained. In the β-CoV genus a similar pattern is observed. All viruses identified in rhinolophid bats cluster together, as do viruses from the vespertilionid/molossid group, and equally so in the related mormoopid/phyllostomid group. These results suggest purifying selection, which is apparently effective at the level of host species or genus. For example, the α-CoV Mex_CoV-1 was only found in Carollia spp. bats, but could be present variably in the species Carollia sowelli or Carollia perspicillata. The same is true of the β-CoVs Mex_CoV-11a and Mex_CoV-11b, both of which were only found in Artibeus spp. bats, but which could be present in either Artibeus lituratus or Artibeus phaeotis. Mex_CoV-6 was found in an Eptesicus sp. bat and clustered very closely with the previously identified Eptesicus-associated CoV (GenBank accession no. HQ585086). Finally, the close association of Mex-CoV-7 and -8 with Myotis velifer and Tadarida brasiliensis, respectively, also suggest strong host specificity. These results agree with previous studies that show individual CoVs are associated with a single species or genus, even among co-roosting species – including Miniopterus, Rousettus, Rhinolophus and Hipposideros bats (Chu et al., 2006; Drexler et al., 2010; Gouilh et al., 2011; Pfefferle et al., 2009; Quan et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2006).

Phylogenetic association of CoVs with host species/genus is particularly evident in allopatric populations separated by significant geographical distances; such as Mex_CoV-6 and the previously identified HQ585086 (GenBank accession no.) virus from Maryland, both of which were found in Eptesicus fuscus and shared a very high sequence identity despite being separated by >2500 km. Misra et al. (2009) reported a similar observation in North America, noting highly similar viruses from Myotis spp. bats in Canada and Colorado. And the same appears to be true in Myotis ricketti in Asia (Tang et al., 2006), in Chaerephon and Rousettus in Africa (Tong et al., 2009b), and in Nyctalus and Myotis spp. bats in Europe (August et al., 2012; Drexler et al., 2010; Gloza-Rausch et al., 2008). In all cases it was concluded that even if populations of these species were thousands of kilometres apart, highly similar CoVs could be detected. It is important to qualify that our results are based on a short sequence, and additional studies will be required to assess whether our observations are consistent when additional sequences from other genes/proteins are considered.

Mex_CoV-5b was the only virus to be found in two distinct (but related) genera, having been detected in both Artibeus and Carollia bats (Fig. 2). Such findings have been reported previously, albeit rarely (Lau et al., 2012a; Osborne et al., 2011; Tong et al., 2009a), and demonstrate that CoVs can infect individuals from different genera/suborders. It is interesting to note that this particular bat (Carollia sowelli, PMX-1232) was captured in a disturbed habitat. Increased efforts for viral discovery in this region will be required to investigate whether disturbed habitats provide increased risk or opportunity for viruses to spillover into new species, as previously suggested (Cottontail et al., 2009; Keesing et al., 2010; Suzán et al., 2012). That said, the health risk to people probably remains low, and bats should not be viewed as a liability, especially given the vital ecosystem functions they serve (Medellín, 2009).

Strong associations of CoVs with host species/genus could prove to be extremely useful in identifying potential reservoirs for viruses that do spillover into other species, assuming that an emergent virus still shares sufficient similarity to those circulating in the original host. A phylogenetic analysis of the new human β-CoV that recently emerged in Saudi Arabia showed that the virus clusters with viruses from bats in the vespertilionid/molossid families, and that the closest relative is the Mex_CoV-9 virus that was identified in a Nyctinomops laticaudatus bat from this study (Fig. 3). Sequence identity between these two viruses is 86.5 % at the nucleotide level, but 96.5 % at the amino acid level. When only the first and second nucleotide positions are considered, nucleotide identity jumps to 97.1 %, demonstrating both that there is strong purifying selection acting on these viruses, and that Mex_CoV-9 and human β-CoV have probably been evolving separately for quite some time. These results do not mean the Saudi Arabian CoV originates in Nyctinomops spp. bat, but do suggest that any search for the original reservoir of this virus should perhaps focus on bats in the molossid/vespertilionid families, or the related nycterid/emballonurid families.

Fig. 3.

Maximum-likelihood tree of a 329 bp fragment of the RdRp from all CoVs (red, α-CoVs; blue, β-CoVs; yellow, γ-CoVs). Viruses discovered in this study are indicated by blue circles. The 2012 human β-CoV is indicated by an arrow, and clusters most closely to PMX-1247/Nyctinomops laticaudatus. Bar, 0.05 nucleotide substitutions per site.

Artibeus was the only genus shown to contain more than one CoV, with the detection of the α-CoVs Mex_CoV-5a and 5b, Mex_CoV-4, and the β-CoVs Mex_CoV-11a/b. However, bats in this genus were also the most frequently sampled (Table 1), which probably explains why more viruses were identified. Other studies have also identified multiple CoVs within a single species, including Rhinolophus sinicus (Yuan et al., 2010) and Rousettus leschenaulti in China (Lau et al., 2010a), and Miniopterus spp. and Rhinolophus spp. from Europe (Drexler et al., 2010); all of which were shown to be doubly and triply infected with different CoVs. Further studies focusing on rarely represented species would be needed to investigate whether population size determines the ability for bats to carry more than one CoV, or whether all genera are capable of supporting multiple CoVs independently of population size. In this study, when multiple CoVs were discovered in a given bat species/genus they were often closely related, for example α-CoVs Mex_CoV-5a/b and β-CoVs Mex_CoV-11a/b. When examined at the amino acid level, these clades collapsed into single groups, yet they maintained separate clades at the nucleotide level, suggesting the contemporary evolution of new strains in these bats. Together, these results highlight the importance of screening sufficient numbers of individuals per species when attempting to describe viral diversity in a given population/region.

Methods used to assess the diversity of host species were also used to measure CoV diversity at undisturbed and disturbed sites in Chiapas and Campeche. No significant difference was seen in CoV diversity across gradients (Chiapas, P = 0.10; Campeche, P = 0.47), mirroring the non-significant difference also observed in the host (described above).

Methods

Sites and sampling.

Bats were captured at three different sites in Mexico, the Reserva de la Biosfera Montes Azules (Chiapas), the Reserva de la Biosfera Calakmul (Campeche), and Mexico City (D.F., Fig. 1). The first two sites, located in south-eastern Mexico represent regions of high species diversity, and are characterized by large tracts of continuous primary vegetation, while Mexico City represents a highly urbanized site. In Chiapas and Campeche bats were collected in two landscape gradients, assigned as: (1) ‘Undisturbed’ forest (UD), where any sign of human impact is largely absent; and (2) ‘Disturbed’ (D), defined as the transition zone between areas of primary vegetation and agriculture/livestock, and by the presence of urban areas. Landscape units were separated by at least 10 km. Capture effort included two nights of trapping using 5×9 m mist nets by roosts or foraging sites. Nets were opened at dusk and remained open for 4 h consecutively. Identification of animals was made using field guides (Medellín et al., 2008). Oral and rectal swabs, and blood were collected (when possible) from each animal. For blood samples <10 % of the blood volume was collected and for small bats blood was taken using protocols previously described (Smith et al., 2010). A veterinarian was present for all sampling and all animals were released safely at the site of capture. Samples were collected directly into lysis buffer and preserved at −80 °C until transfer to the Center for Infection and Immunity for CoV screening. Capture and sample collection was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Davis (protocol number: 16048).

Laboratory testing.

Total nucleic acid was extracted from all samples using the EasyMag (bioMérieux) platform, and cDNA synthesis performed using SuperScript III first strand synthesis supermix (Invitrogen), all according the manufacturer’s instructions. CoV discovery was performed using broadly reactive consensus PCR primers, targeting the RdRp (Quan et al., 2010). PCR products of the expected size were cloned into Strataclone PCR cloning vector and sequenced using standard M13R primers. If an individual tested positive for CoV, the species of the bat was secondarily confirmed with genetic barcoding, targeting both cytochrome oxidase subunit I and Cyt-b mitochondrial genes, as described previously (Townzen et al., 2008).

Analysis.

Sequences were edited using Geneious Pro (5.6.4). Alignments were constructed using clustal w, executed through Geneious, and refined manually. Neighbour-joining and maximum-likelihood trees were built in mega (5.0), and bootstrapped using 1000 repetitions. Nucleotide trees that represent a consensus of both methods are presented. Evaluations of host and viral diversity at each site/habitat were made using the Shannon–Wiener diversity index (H′) using the Past 1.81 software. This index takes into account the number of individuals as well as the number of taxa. A 0 value means that the community has only a single taxon. Comparison of the Shannon–Wiener diversities (entropies); were calculated between habitat types for each region using the Shannon t-test, described by Poole (1974).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT, NIH-AI57158 (NBC-Lipkin), NIH NIAID R01 A1079231 (non-biodefense EID), DTRA and CONACYT (#290674). We thank Angélica Menchaca, Ana Cecilia Ibarra, Adriana Fernández, William Karesh, Jonna Mazet, Karen Moreno, Stephen Morse, Monica Quijada, Ivan Olivera and Ashley Case. We further thank Dr Nicole Arrigo for editing and comments on the manuscript. The contents of this paper are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

References

- Agnarsson I., Zambrana-Torrelio C. M., Flores-Saldana N. P., May-Collado L. J. (2011) A time-calibrated species-level phylogeny of bats (Chiroptera, Mammalia). PloS Currents: Tree of Life Version 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita H. T., Ortega J. (1998). The Middle-American bat fauna: conservation in the Neotropical-Nearctic border. In Bat Biology and Conservation, pp. 295–308. Edited by Kunz T. H., Racey P. A. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- August T. A., Mathews F., Nunn M. A. (2012). Alphacoronavirus detected in bats in the United Kingdom. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 12, 530–533. 10.1089/vbz.2011.0829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calisher C. H., Childs J. E., Field H. E., Holmes K. V., Schountz T. (2006). Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 19, 531–545. 10.1128/CMR.00017-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington C. V., Foster J. E., Zhu H. C., Zhang J. X., Smith G. J., Thompson N., Auguste A. J., Ramkissoon V., Adesiyun A. A., Guan Y. (2008). Detection and phylogenetic analysis of group 1 coronaviruses in South American bats. Emerg Infect Dis 14, 1890–1893. 10.3201/eid1412.080642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. (2005). Coronaviruses in poultry and other birds. Avian Pathol 34, 439–448. 10.1080/03079450500367682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D. K. W., Poon L. L. M., Chan K. H., Chen H., Guan Y., Yuen K. Y., Peiris J. S. M. (2006). Coronaviruses in bent-winged bats (Miniopterus spp.). J Gen Virol 87, 2461–2466. 10.1099/vir.0.82203-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D. K. W., Peiris J. S. M., Poon L. L. M. (2009). Novel coronaviruses and astroviruses in bats. Virol Sin 24, 100–104. 10.1007/s12250-009-3031-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D. K. W., Leung C. Y. H., Gilbert M., Joyner P. H., Ng E. M., Tse T. M., Guan Y., Peiris J. S. M., Poon L. L. M. (2011). Avian coronavirus in wild aquatic birds. J Virol 85, 12815–12820. 10.1128/JVI.05838-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottontail V. M., Wellinghausen N., Kalko E. K. (2009). Habitat fragmentation and haemoparasites in the common fruit bat, Artibeus jamaicensis (Phyllostomidae) in a tropical lowland forest in Panamá. Parasitology 136, 1133–1145. 10.1017/S0031182009990485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez S. R., O’Shea T. J., Oko L. M., Holmes K. V. (2007). Detection of group 1 coronaviruses in bats in North America. Emerg Infect Dis 13, 1295–1300. 10.3201/eid1309.070491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson E. F., Haskew A. N., Gates J. E., Huynh J., Moore C. J., Frieman M. B. (2010). Metagenomic analysis of the viromes of three North American bat species: viral diversity among different bat species that share a common habitat. J Virol 84, 13004–13018. 10.1128/JVI.01255-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B. Q., Liu W., Fan X. H., Vijaykrishna D., Tang X. C., Gao F., Li L. F., Li G. J., Zhang J. X. & other authors (2007). Detection of a novel and highly divergent coronavirus from Asian leopard cats and Chinese ferret badgers in Southern China. J Virol 81, 6920–6926. 10.1128/JVI.00299-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler J. F., Gloza-Rausch F., Glende J., Corman V. M., Muth D., Goettsche M., Seebens A., Niedrig M., Pfefferle S. & other authors (2010). Genomic characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus in European bats and classification of coronaviruses based on partial RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene sequences. J Virol 84, 11336–11349. 10.1128/JVI.00650-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler J. F., Corman V. M., Wegner T., Tateno A. F., Zerbinati R. M., Gloza-Rausch F., Seebens A., Müller M. A., Drosten C. (2011). Amplification of emerging viruses in a bat colony. Emerg Infect Dis 17, 449–456. 10.3201/eid1703.100526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler J. F., Corman V. M., Müller M. A., Maganga G. D., Vallo P., Binger T., Gloza-Rausch F., Rasche A., Yordanov S. & other authors (2012). Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat Commun 3, 796. 10.1038/ncomms1796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcón A., Vázquez-Morón S., Casas I., Aznar C., Ruiz G., Pozo F., Perez-Breña P., Juste J., Ibáñez C. & other authors (2011). Detection of alpha and betacoronaviruses in multiple Iberian bat species. Arch Virol 156, 1883–1890. 10.1007/s00705-011-1057-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felippe P. A. N., da Silva L. H. A., Santos M. M., Spilki F. R., Arns C. W. (2010). Genetic diversity of avian infectious bronchitis virus isolated from domestic chicken flocks and coronaviruses from feral pigeons in Brazil between 2003 and 2009. Avian Dis 54, 1191–1196. 10.1637/9371-041510-Reg.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X., Li Y., Yang X., Zhang H., Zhou P., Zhang Y., Shi Z. (2012a). Metagenomic analysis of viruses from bat fecal samples reveals many novel viruses in insectivorous bats in China. J Virol 86, 4620–4630. 10.1128/JVI.06671-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X., Li Y., Yang X., Zhang H., Zhou P., Zhang Y., Shi Z. (2012b). Metagenomic analysis of viruses from bat fecal samples reveals many novel viruses in insectivorous bats in China. J Virol 86, 4620–4630. 10.1128/JVI.06671-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloza-Rausch F., Ipsen A., Seebens A., Göttsche M., Panning M., Drexler J. F., Petersen N., Annan A., Grywna K. & other authors (2008). Detection and prevalence patterns of group I coronaviruses in bats, northern Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 14, 626–631. 10.3201/eid1404.071439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouilh M. A., Puechmaille S. J., Gonzalez J.-P., Teeling E., Kittayapong P., Manuguerra J.-C. (2011). SARS-Coronavirus ancestor’s foot-prints in South-East Asian bat colonies and the refuge theory. Infect Genet Evol 11, 1690–1702. 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Zheng B. J., He Y. Q., Liu X. L., Zhuang Z. X., Cheung C. L., Luo S. W., Li P. H., Zhang L. J. & other authors (2003). Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science 302, 276–278. 10.1126/science.1087139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackwood M. W., Hall D., Handel A. (2012). Molecular evolution and emergence of avian gammacoronaviruses. Infect Genet Evol 12, 1305–1311. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G. L., Zhang Y., Wu T. H., Zhang S. Y., Wang Y. N. (2003). Fruit bats as a natural reservoir of zoonotic viruses. Chin Sci Bull 48, 1179–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. E., Patel N. G., Levy M. A., Storeygard A., Balk D., Gittleman J. L., Daszak P. (2008). Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993. 10.1038/nature06536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing F., Belden L. K., Daszak P., Dobson A., Harvell C. D., Holt R. D., Hudson P., Jolles A., Jones K. E. & other authors (2010). Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature 468, 647–652. 10.1038/nature09575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. M. Q., Adams M. J., Carstens E. B., Lefkowitz E. J. (editors) (2012). Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, CA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. K., Woo P. C., Li K. S., Huang Y., Tsoi H. W., Wong B. H., Wong S. S., Leung S. Y., Chan K. H., Yuen K. Y. (2005). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 14040–14045. 10.1073/pnas.0506735102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. K. P., Poon R. W. S., Wong B. H. L., Wang M., Huang Y., Xu H. F., Guo R. T., Li K. S. M., Gao K. & other authors (2010a). Coexistence of different genotypes in the same bat and serological characterization of Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9 belonging to a novel Betacoronavirus subgroup. J Virol 84, 11385–11394. 10.1128/JVI.01121-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lau S. K. P., Li K. S. M., Huang Y., Shek C. T., Tse H., Wang M., Choi G. K. Y., Xu H. F., Lam C. S. F. & other authors (2010b). Ecoepidemiology and complete genome comparison of different strains of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related Rhinolophus bat coronavirus in China reveal bats as a reservoir for acute, self-limiting infection that allows recombination events. J Virol 84, 2808–2819. 10.1128/JVI.02219-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. K., Li K. S., Tsang A. K., Shek C. T., Wang M., Choi G. K., Guo R., Wong B. H., Poon R. W. & other authors (2012a). Recent transmission of a novel alphacoronavirus, bat coronavirus HKU10, from Leschenault’s rousettes to pomona leaf-nosed bats: first evidence of interspecies transmission of coronavirus between bats of different suborders. J Virol 86, 11906–11918. 10.1128/JVI.01305-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. K. P., Woo P. C. Y., Yip C. C. Y., Fan R. Y. Y., Huang Y., Wang M., Guo R. T., Lam C. S. F., Tsang A. K. L. & other authors (2012b). Isolation and characterization of a novel Betacoronavirus subgroup A coronavirus, rabbit coronavirus HKU14, from domestic rabbits. J Virol 86, 5481–5496. 10.1128/JVI.06927-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy E. M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X., Rouquet P., Hassanin A., Yaba P., Délicat A., Paweska J. T., Gonzalez J. P., Swanepoel R. (2005). Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438, 575–576. 10.1038/438575a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Shi Z., Yu M., Ren W., Smith C., Epstein J. H., Wang H., Crameri G., Hu Z. & other authors (2005). Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 310, 676–679. 10.1126/science.1118391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medellín R. A. (2009). Sustaining transboundary ecosystem services provided by bats. In Conservation of Shared Environments: Learning from the United States and Mexico, pp. 171–187. Edited by Lopez-Hoffman L., McGovern E., Varady R., Flessa K. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medellín R. A., Equihua M., Amin M. A. (2000). Bat diversity and abundance as indicators of disturbance in Neotropical rainforests. Conserv Biol 14, 1666–1675. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.99068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medellín R. A., Arita H. T., Sanchez H. (2008). Identificación de los Murciélagos de México. Clave de Campo, 2nd edn. Distrito Federal, México: Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Misra V., Dumonceaux T., Dubois J., Willis C., Nadin-Davis S., Severini A., Wandeler A., Lindsay R., Artsob H. (2009). Detection of polyoma and corona viruses in bats of Canada. J Gen Virol 90, 2015–2022. 10.1099/vir.0.010694-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C., Cryan P. M., O’Shea T. J., Oko L. M., Ndaluka C., Calisher C. H., Berglund A. D., Klavetter M. L., Bowen R. A. & other authors (2011). Alphacoronaviruses in New World bats: prevalence, persistence, phylogeny, and potential for interaction with humans. PLoS ONE 6, e19156. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferle S., Oppong S., Drexler J. F., Gloza-Rausch F., Ipsen A., Seebens A., Müller M. A., Annan A., Vallo P. & other authors (2009). Distant relatives of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and close relatives of human coronavirus 229E in bats, Ghana. Emerg Infect Dis 15, 1377–1384. 10.3201/eid1509.090224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R.W. (1974). An Introduction to Quantitative Ecology. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Quan P. L., Firth C., Street C., Henriquez J. A., Petrosov A., Tashmukhamedova A., Hutchison S. K., Egholm M., Osinubi M. O. V. & other authors (2010). Identification of a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in a leaf-nosed bat in Nigeria. MBio 1, e00208–e00210. 10.1128/mBio.00208-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S. A., Hassan S. S., Olival K. J., Mohamed M., Chang L. Y., Hassan L., Saad N. M., Shohaimi S. A., Mamat Z. C. & other authors (2010). Characterization of Nipah virus from naturally infected Pteropus vampyrus bats, Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis 16, 1990–1993. 10.3201/eid1612.091790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reusken C. B., Lina P. H. C., Pielaat A., de Vries A., Dam-Deisz C., Adema J., Drexler J. F., Drosten C., Kooi E. A. (2010). Circulation of group 2 coronaviruses in a bat species common to urban areas in Western Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 10, 785–791. 10.1089/vbz.2009.0173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihtaric D., Hostnik P., Steyer A., Grom J., Toplak I. (2010). Identification of SARS-like coronaviruses in horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros) in Slovenia. Arch Virol 155, 507–514. 10.1007/s00705-010-0612-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato K., Maeda K., Tsuda S., Suzuki K., Watanabe S., Shimoda H., Ueda N., Iha K., Taniguchi S. & other authors (2012). Detection of bat coronaviruses from Miniopterus fuliginosus in Japan. Virus Genes 44, 40–44. 10.1007/s11262-011-0661-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C., De Jong C., Field H. (2010). Sampling small quantities of blood from microbats. Acta Chiropt 12, 255–258. 10.3161/150811010X504752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzán G., Esponda F., Carrasco-Hernández R., Aguirre A. (2012). Habitat fragmentation and infectious disease ecology. In New Directions in Conservation Medicine: Applied Cases of Ecological Health, pp. 135–150. Edited by Aguirre A., Ostfeld R., Daszak P. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tang X. C., Zhang J. X., Zhang S. Y., Wang P., Fan X. H., Li L. F., Li G., Dong B. Q., Liu W. & other authors (2006). Prevalence and genetic diversity of coronaviruses in bats from China. J Virol 80, 7481–7490. 10.1128/JVI.00697-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeling E. C., Springer M. S., Madsen O., Bates P., O’Brien S. J., Murphy W. J. (2005). A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science 307, 580–584. 10.1126/science.1105113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S., Conrardy C., Ruone S., Kuzmin I. V., Guo X., Tao Y., Niezgoda M., Haynes L., Agwanda B. & other authors (2009a). Detection of novel SARS-like and other coronaviruses in bats from Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis 15, 482–485. 10.3201/eid1503.081013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S. X., Conrardy C., Ruone S., Kuzmin I. V., Guo X. L., Tao Y., Niezgoda M., Haynes L., Agwanda B. & other authors (2009b). Detection of novel SARS-like and other coronaviruses in bats from Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis 15, 482–485. 10.3201/eid1503.081013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towner J. S., Pourrut X., Albariño C. G., Nkogue C. N., Bird B. H., Grard G., Ksiazek T. G., Gonzalez J. P., Nichol S. T., Leroy E. M. (2007). Marburg virus infection detected in a common African bat. PLoS ONE 2, e764. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townzen J. S., Brower A. V. Z., Judd D. D. (2008). Identification of mosquito bloodmeals using mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I and cytochrome b gene sequences. Med Vet Entomol 22, 386–393. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S., Masangkay J. S., Nagata N., Morikawa S., Mizutani T., Fukushi S., Alviola P., Omatsu T., Ueda N. & other authors (2010). Bat coronaviruses and experimental infection of bats, the Philippines. Emerg Infect Dis 16, 1217–1223. 10.3201/eid1608.100208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2004). Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/index.html.

- Wilson D. E., Reeder D. M. (2005). Mammal Species of the World. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woo P. C. Y., Lau S. K. P., Li K. S. M., Poon R. W. S., Wong B. H. L., Tsoi H. W., Yip B. C. K., Huang Y., Chan K. H., Yuen K. Y. (2006). Molecular diversity of coronaviruses in bats. Virology 351, 180–187. 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P. C., Lau S. K., Yip C. C., Huang Y., Yuen K. Y. (2009a). More and more coronaviruses: human coronavirus HKU1. Viruses 1, 57–71. 10.3390/v1010057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P. C. Y., Lau S. K. P., Lam C. S. F., Lai K. K. Y., Huang Y., Lee P., Luk G. S. M., Dyrting K. C., Chan K. H., Yuen K. Y. (2009b). Comparative analysis of complete genome sequences of three avian coronaviruses reveals a novel group 3c coronavirus. J Virol 83, 908–917. 10.1128/JVI.01977-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P. C. Y., Lau S. K. P., Lam C. S. F., Lau C. C. Y., Tsang A. K. L., Lau J. H. N., Bai R., Teng J. L. L., Tsang C. C. C. & other authors (2012). Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus Deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. J Virol 86, 3995–4008. 10.1128/JVI.06540-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J. F., Hon C. C., Li Y., Wang D. M., Xu G. L., Zhang H. J., Zhou P., Poon L. L. M., Lam T. T. Y. & other authors (2010). Intraspecies diversity of SARS-like coronaviruses in Rhinolophus sinicus and its implications for the origin of SARS coronaviruses in humans. J Gen Virol 91, 1058–1062. 10.1099/vir.0.016378-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki A. M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T. M., Osterhaus A. D., Fouchier R. A. (2012). Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med 367, 1814–1820. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]