Abstract

Polymorphism in the TRIM5α/TRIMcyp gene, which interacts with the lentiviral capsid, has been shown to impact on simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) replication in certain macaque species. Here, in the context of a live-attenuated SIV vaccine study conducted in Mauritian-origin cynomolgus macaques (MCM), we demonstrate upregulation of TRIM5α expression in multiple lymphoid tissues immediately following vaccination. Despite this, the restricted range of TRIM5α genotypes and lack of TRIMcyp variants had no or only limited impact on the replication kinetics in vivo of either the SIVmac viral vaccine or wild-type SIVsmE660 challenge. Additionally, there appeared to be no impact of TRIM5α genotype on the outcome of homologous or heterologous vaccination/challenge studies. The limited spectrum of TRIM5α polymorphism in MCM appears to minimize host bias to provide consistency of replication for SIVmac/SIVsm viruses in vivo, and therefore on vaccination and pathogenesis studies conducted in this species.

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in macaques represents a widely used, non-human primate model to study pathogenic lentivirus infection and to evaluate new therapeutic strategies against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In live-attenuated SIV vaccination (LAV) studies, significant levels of protection against wild-type virus challenge can be conferred against both homologous (Almond et al., 1995; Berry et al., 2008; Daniel et al., 1992) and heterologous (Berry et al., 2011; Wyand et al., 1999) virus challenge. However, levels of protection vary between different viral challenges and among different host species. Although a live-attenuated HIV vaccine is unlikely ever to be employed due to safety concerns, characterization of the mechanism of protection could unveil novel strategies to reproduce this potent protection safely. In the Mauritian cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis; MCM) model, protection seems to be acting as early as 21 days post-vaccination (Stebbings et al., 2004; Berry et al., 2011), when adaptive responses are either not fully matured or do not appear to be central to the protection observed in this model (Almond et al., 1997; Stebbings et al., 2005).

To extend these studies, we examined whether TRIM5α expression is induced by live-attenuated SIV vaccination and whether TRIM5α polymorphism may play a contributory role in vaccine outcome. TRIM5α is a component of the innate immune system responsible for an intracellular block to retroviruses (Stremlau et al., 2004; Yap et al., 2004), as well as being a sensor for the innate immune response (Pertel et al., 2011). In SIV/macaque studies, polymorphisms in TRIM5α have been correlated with differential control of SIV infection (de Groot et al., 2011; Kirmaier et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2010), suggesting that genotypic variation in TRIM5α and/or expression may impact both on the ability of an attenuated SIV to replicate in vivo and, perhaps, on subsequent protection conferred by live-attenuated SIV vaccination. However, expression levels of TRIM5α in tissues susceptible to SIV infection have not been hitherto described. Here, we have measured TRIM5α mRNA levels in a previously reported early-pathogenesis SIV/MCM study (Li et al., 2011). Briefly, 16 MCM were inoculated intravenously with a nef-disrupted SIV, SIVmac251/C8, which has been shown to confer protection at 3 and 20 weeks post-infection (Berry et al., 2011, 2008; Stebbings et al., 2004). At these and earlier time points, macaques were sacrificed and multiple lymphoid tissues and blood were collected.

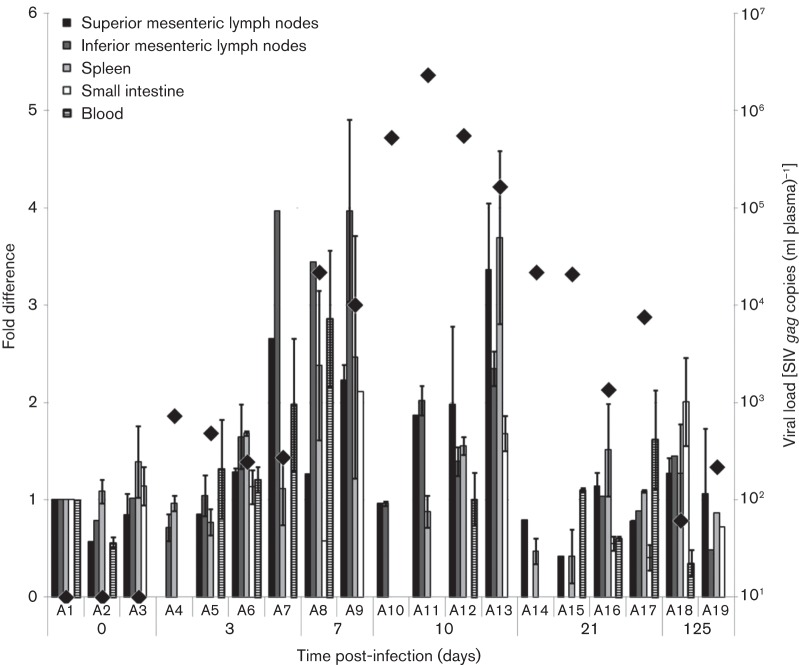

Viral RNA (vRNA) in plasma was detected at day 3, increasing progressively to a peak at day 10; vRNA then declined, but still persisted at low levels at day 125 (Li et al., 2011). Total RNA was isolated from a range of different tissues taken at 0, 3, 7, 10, 21 and 125 days post-inoculation, and TRIM5α and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RNA levels were quantified by SYBR Green-based quantitative PCR, using primers TRIM5s (5′-CGCTACTGGGTTGATGTGACAC-3′) and TRIM5ns (5′-CCCTGGTGCCTGATACATTATCTG-3′) or GAPDH-s (5′-GGCTGAGAACGGGAAGCTC-3′) and GAPDH-ns (5′-AGGGATCTCGCTCCTGGAA-3′). TRIM5α copy number was normalized to that of GAPDH and expressed as fold difference in comparison to one of the naïve animals (A1; Fig. 1). Despite considerable variation across individual tissues and between vaccinates in response to SIVmac251/C8 infection, there was a significant increase in TRIM5α mRNA expression over days 3, 7 and 10, when all tissues were analysed together and compared with naïve, unvaccinated macaques (P = 0.012, two-tailed t-test). However, beyond the peak of virus production (day 10), TRIM5α mRNA expression returned to the normal range between days 21 and 125, when the plasma viral RNA levels were low, and the overall virus profile is that of a controlled infection. TRIM5α mRNA kinetics were similar to those observed previously for APOBEC3G in rhesus macaques (Mußil et al., 2011), suggesting a general response to acute retroviral infection, most likely mediated by a type 1 interferon. Whether this increase in restriction factor expression levels influences the antiviral state of the host is difficult to determine, as the transient increase in TRIM5 mRNA levels was not maintained at these higher induction levels beyond the immediate acute phase, and no correlation was found between TRIM5α expression and viral load in plasma (Fig. 1). However, we reasoned that the higher level of TRIM5α expression observed during the peak of primary viraemia could influence subsequent outcome of SIV infection or vaccination, the extent of which could differ in MCM with different TRIM5α genotypes.

Fig. 1.

TRIM5α RNA expression level in tissues. Total RNA was extracted from cell-derived tissues and reverse-transcribed, and cDNA equivalent to 20–50 ng total RNA was used in a SYBR Green-based quantitative PCR. PCR product specificity was assessed by dissociation curves. TRIM5α copy numbers were normalized to 5×105 GAPDH copies and the naïve animal A1, used as calibrator. All experiments were run in duplicate and error bars represent the mean±sd of two independent experiments. vRNA in plasma for each animal at the time of termination (⧫) was measured by quantitative RT-PCR as described previously (Berry et al., 2008).

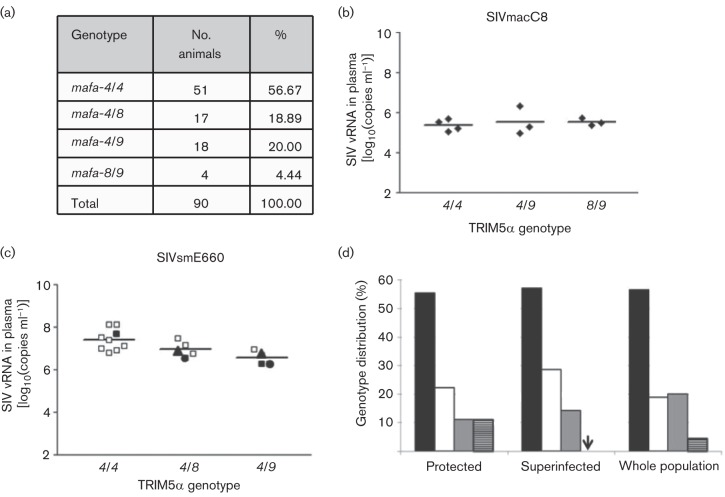

In rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), variations in the sequence of the TRIM5α B30.2 domain, including its replacement with cyclophilin A, have a great impact on lentiviral infection both in vivo and in vitro (de Groot et al., 2011; Kirmaier et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2008). MCM display limited genetic diversity as a result of a small founder population and geographical isolation (Tosi & Coke, 2007), offering the potential to develop an SIV/macaque model where the confounding effects of host genetics can be minimized. TRIM5α genotypes in cynomolgus macaques of different origin have also been recently characterized (Berry et al., 2012; de Groot et al., 2011; Dietrich et al., 2011; Saito et al., 2012). Only three alleles have been identified in MCM: mafa-4 (identical to rhesus mamu-4) and cynomolgus-specific mafa-8 and mafa-9, but to date no TRIMCyp variants (with cyclophilin A) have been identified (Berry et al., 2012; de Groot et al., 2011; Dietrich et al., 2011). These three alleles, in the B30.2 domain, differ only by three amino acids (M330V and Y389C in mafa-8, and I437V in mafa-9); however, they all share the Q339TFP polymorphism, which, in rhesus macaques, is associated with a permissive phenotype (Kirmaier et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2010). We extended this genotyping of MCM as described previously (Berry et al., 2012) to a total of 90 MCM. This confirmed the presence of only the three previously identified alleles, with the mafa-4/4 homozygote constituting 56.7 % of the population, and with only four of 90 MCM not carrying the mafa-4 allele (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Lack of correlation between SIV infection and TRIM5α genotype. (a) TRIM5α genotype was characterized in 90 MCM. (b, c) Viral load in plasma. MCM were infected intravenously with 5000 TCID50 of the 9/90 pool of SIVmacC8 (b), or with 10 (□), 100 (▪), 1000 (▴) or 10 000 (•) MID50 of SIVsmE660 (c). Viral load in plasma was determined at 10 (b) or 14 (c) days post-inoculation by quantitative probe-based one-step RT-PCR. Differences between genotypes were not statistically significantly different by one-way ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test. The difference between viral loads for genotypes mafa-4/4 versus mafa-4/9 (c) was significant by Dunn’s multiple comparison test (P<0.05). (d) MCM were vaccinated with 5×103 TCID50 SIVmacC8, and challenged 3 or 20 weeks post-vaccination with 10 MID50 of SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251/L28. Six of eight animals challenged with SIVsmE660 and three of eight animals infected with SIVmac251/L28 were protected. One of the two SIVsmE660-superinfected animals and two with SIVmac251/L28 were vaccinated for 3 weeks and the others for 20 weeks. MCM were grouped based on study outcome and compared with the whole population. Percentages of each genotype [mafa-4/4 (black), -4/8 (white), -4/9 (grey) and -8/9 (striped)] were calculated for each group. Distribution of the genotypes among the different groups was not found to be statistically significantly different as assessed by Fisher’s exact test.

We then examined the contribution of each genotype to the level of plasma vRNA at the time of peak viraemia (10–14 days) following intravenous infection with 5000 TCID50 of the 9/90 pool of SIVmacC8 (Rud et al., 1994) as used in live-attenuated SIV vaccine studies, or 10–10 000 MID50 of an uncloned heterologous SIVsmE660 challenge stock (Berry et al., 2011), representing a wild-type SIVsm-derived virus (Fig. 2b, c). No major differences in viral load at the peak of viraemia for SIVmacC8 could be associated with any of the TRIM5α genotypes (Fig. 2b). Levels of SIVsmE660 in plasma were also similar, regardless of the initial viral dose (Berry et al., 2011) or TRIM5α genotype (Fig. 2c), although the difference in the mean for the mafa-4/4 homozygotes and the mafa-4/9 heterozygotes was significant by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Hence, there was no strong impact of TRIM5α genotype on acquisition or replication potential of SIVmac or SIVsm in vivo in MCM.

In further support of this hypothesis, we retrospectively analysed two previously published LAV vaccination studies. Briefly, 16 MCM were vaccinated with 5×103 TCID50 SIVmacC8 and challenged with either SIVmac251/L28 (Berry et al., 2008) or SIVsmE660 (Berry et al., 2011), representing homologous and heterologous challenges, respectively. Taking these two vaccine populations together, irrespective of the composition of the virus challenge, mafa-4/4 homozygotes constituted 62.5 % of the protected macaques, 50 % of the superinfected and 55.8 % of the total; mafa-4/8 heterozygotes were slightly more represented in the superinfected MCM (28.6 %) than in protected ones or the whole population (18.6 and 18.7 %, respectively). A total of 18.7 % of the protected macaques, 14.3 % of the superinfected and 20 % of all MCM were mafa-4/9 heterozygotes. There was just one macaque with the genotype mafa-8/9, which was protected from viral rechallenge, but there were insufficient data for statistical analysis. These data suggest that distribution of TRIM5α genotypes among vaccine study populations does not differ significantly between protected and superinfected vaccinated macaques, in comparison with the whole population (Fig. 2d), and hence TRIM5α genotype per se has no impact on vaccine/study outcome. This would appear to hold for both homologous and heterologous virus challenges in such a scenario.

Finally, the three MCM TRIM5α alleles were tested in vitro for their ability to restrict lentiviral infection. TRIM5α genes were PCR-cloned using cDNA from animals with genotypes mafa-4/8 and mafa-4/9 and the following primers: sense, 5′-TAGAATTCGCTTCTGGAATCCTGC-3′, and antisense, 5′-TCACGTCGACTCAAGAGCTTGGTGAG-3′ (EcoRI and SalI restriction sites underlined). PCR products were subcloned into the gammaretroviral vector EXN (Zhang et al., 2006), downstream and in frame with a haemagglutinin (HA) tag using the restriction enzymes EcoRI and SalI. Crandell–Rees feline kidney (CRFK) cells stably expressing TRIM5α alleles were produced as described previously (Ylinen et al., 2010). Similar TRIM5α expression levels were assessed by Western blotting using an anti-HA.11 antibody (Covance; dilution 1 : 1000) and anti-β-actin (Abcam; dilution 1 : 1000), together with an HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (DAKO; 1 : 3000 dilution) (Fig. 3a). TRIM5α-expressing cells were exposed to serial dilutions of VSV-G-pseudotyped, lentiviral vectors derived from HIV-1 (Zufferey et al., 1997), HIV-2 (Griffin et al., 2001) or SIVmac251 (Nègre et al., 2000) carrying a GFP marker gene, and infectious titres were inferred by flow-cytometry analysis. GFP/SIVsmE660 was obtained by replacing SIVmac Gag aa 1–373 with the equivalent residues from SIVsmE660, using XhoI and AgeI restriction sites added to the SIVmac packaging plasmid SIV3+ by mutagenesis. The SIVsmE660 gag sequence (GenBank accession no. JX119100) was cloned from vRNA purified from infected animals using the following primers: sense, 5′-TAGAGCTCGAGATGGGCGCGAGAAACTCCGTC-3′, and antisense, 5′-TCGCGACCGGTCTCAGTGCCTCTTTCAATGCTTC-3′ (XhoI and AgeI restriction sites underlined). As expected, HIV-1 vector titre was reduced in cells expressing the simian TRIM5α genes, but no significant reduction of titre was observed for HIV-2, SIVmac251 or SIVsmE660 (Fig. 3b). The non-restrictive phenotype of the MCM TRIM5α alleles, which all carry a glutamine at aa 339, concurs with previous reports (Kirmaier et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

Lentiviral infection in CRFK cells expressing MCM TRIM5α alleles. Feline CRFK cells were transduced using a gammaretroviral vector to express MCM N-terminal HA-tagged TRIM5α alleles mafa-4, mafa-8 and mafa-9 or an empty vector. (a) Cell lysates were harvested 2 weeks post-TRIM5α expression, after selection with G418, and subjected to immunoblotting using monoclonal anti-HA.11 antibody. β-Actin was detected on the same membrane to assess protein input. (b) CRFK cells were infected with fivefold serial dilutions of GFP-expressing lentiviruses and viral titres were determined by monitoring EGFP expression by flow cytometry. Histograms represent the mean±sem of three independent experiments. Only for HIV-1 was the reduction of viral titre between empty vector (EV) and MCM TRIM5α alleles statistically significant (t-test; P<0.05).

Although we cannot categorically exclude a contribution of TRIM5α gene expression to the long-term control of SIV/HIV-2 infection in vivo and/or vaccination in MCM, we hypothesize that any effects will be minimal, as the only three alleles identified in MCM do not restrict HIV-2, SIVmac251 or SIVsmE660 (Fig. 3). In addition, no correlation between the four different MCM TRIM5α genotypes and outcome of SIV infection in naïve or vaccinated MCM was observed, although a larger number of animals could improve the statistical significance of these observations. MHC genotyping will still be required, as it has been shown that certain MCM haplotypes have an impact on SIV infection in MCM (Mee et al., 2009; Mühl et al., 2002). Animals used in this study have been MHC-genotyped and only two of them (A5 and A17) express allele M6, associated with spontaneous control of infection. No correlation was found with virus replication (Fig. 1).

The results presented here suggest that prerequisite TRIM5α genotyping is of low priority in cynomolgus macaques of Mauritian origin. Our data consolidate the MCM/SIV system as a powerful model to study HIV/AIDS, where bias introduced by host genetics can be reduced to a minimum and rationalized. The replication potential of different SIVmac/SIVsm viruses appears to be largely unimpeded by different TRIM5 genotypes in this non-human primate model of HIV infection and study outcomes unaffected by predisposition to particular TRIM5 variants.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by MRC grants G9025730, G9419998, G0600007 and G0801172, the NIHR Centre for Research in Health Protection at the Health Protection Agency, a Wellcome Trust Fellowship to G. J. T. and the National Institute of Health Research UCL/UCLH Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre. The authors have non-financial competing interests.

References

- Almond N., Kent K., Stott E. J., Cranage M., Rud E., Clarke B., Rud E. (1995). Protection by attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus in macaques against challenge with virus-infected cells. Lancet 345, 1342–1344 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92540-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond N., Rose J., Sangster R., Silvera P., Stebbings R., Walker B., Stott E. J. (1997). Mechanisms of protection induced by attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. I. Protection cannot be transferred with immune serum. J Gen Virol 78, 1919–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry N., Stebbings R., Ferguson D., Ham C., Alden J., Brown S., Jenkins A., Lines J., Duffy L. & other authors (2008). Resistance to superinfection by a vigorously replicating, uncloned stock of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac251) stimulates replication of a live attenuated virus vaccine (SIVmacC8). J Gen Virol 89, 2240–2251 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001693-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry N., Ham C., Mee E. T., Rose N. J., Mattiuzzo G., Jenkins A., Page M., Elsley W., Robinson M. & other authors (2011). Early potent protection against heterologous SIVsmE660 challenge following live attenuated SIV vaccination in Mauritian cynomolgus macaques. PLoS ONE 6, e23092 10.1371/journal.pone.0023092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry N. J., Marzetta F., Towers G. J., Rose N. J. (2012). Diversity of TRIM5α and TRIMCyp sequences in cynomolgus macaques from different geographical origins. Immunogenetics 64, 267–278 10.1007/s00251-011-0585-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M. D., Kirchhoff F., Czajak S. C., Sehgal P. K., Desrosiers R. C. (1992). Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science 258, 1938–1941 10.1126/science.1470917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot N. G., Heijmans C. M., Koopman G., Verschoor E. J., Bogers W. M., Bontrop R. E. (2011). TRIM5 allelic polymorphism in macaque species/populations of different geographic origins: its impact on SIV vaccine studies. Tissue Antigens 78, 256–262 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2011.01768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich E. A., Brennan G., Ferguson B., Wiseman R. W., O’Connor D., Hu S. L. (2011). Variable prevalence and functional diversity of the antiretroviral restriction factor TRIMCyp in Macaca fascicularis. J Virol 85, 9956–9963 10.1128/JVI.00097-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin S. D., Allen J. F., Lever A. M. (2001). The major human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) packaging signal is present on all HIV-2 RNA species: cotranslational RNA encapsidation and limitation of Gag protein confer specificity. J Virol 75, 12058–12069 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12058-12069.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmaier A., Wu F., Newman R. M., Hall L. R., Morgan J. S., O’Connor S., Marx P. A., Meythaler M., Goldstein S. & other authors (2010). TRIM5 suppresses cross-species transmission of a primate immunodeficiency virus and selects for emergence of resistant variants in the new species. PLoS Biol 8, e1000462 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Berry N., Ham C., Ferguson D., Smith D., Hall J., Page M., Quartey-Papafio R., Elsley W. & other authors (2011). Vaccination with live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus causes dynamic changes in intestinal CD4+CCR5+ T cells. Retrovirology 8, 8 10.1186/1742-4690-8-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. Y., Rogers T., Chan T., Whitney J. B., Kim J., Sodroski J., Letvin N. L. (2010). TRIM5α modulates immunodeficiency virus control in rhesus monkeys. PLoS Pathog 6, e1000738 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee E. T., Berry N., Ham C., Sauermann U., Maggiorella M. T., Martinon F., Verschoor E. J., Heeney J. L., Le Grand R. & other authors (2009). Mhc haplotype H6 is associated with sustained control of SIVmac251 infection in Mauritian cynomolgus macaques. Immunogenetics 61, 327–339 10.1007/s00251-009-0369-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühl T., Krawczak M., Ten Haaft P., Hunsmann G., Sauermann U. (2002). MHC class I alleles influence set-point viral load and survival time in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J Immunol 169, 3438–3446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mußil B., Sauermann U., Motzkus D., Stahl-Hennig C., Sopper S. (2011). Increased APOBEC3G and APOBEC3F expression is associated with low viral load and prolonged survival in simian immunodeficiency virus infected rhesus monkeys. Retrovirology 8, 77 10.1186/1742-4690-8-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nègre D., Mangeot P. E., Duisit G., Blanchard S., Vidalain P. O., Leissner P., Winter A. J., Rabourdin-Combe C., Mehtali M. & other authors (2000). Characterization of novel safe lentiviral vectors derived from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac251) that efficiently transduce mature human dendritic cells. Gene Ther 7, 1613–1623 10.1038/sj.gt.3301292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertel T., Hausmann S., Morger D., Züger S., Guerra J., Lascano J., Reinhard C., Santoni F. A., Uchil P. D. & other authors (2011). TRIM5 is an innate immune sensor for the retrovirus capsid lattice. Nature 472, 361–365 10.1038/nature09976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rud E. W., Cranage M., Yon J., Quirk J., Ogilvie L., Cook N., Webster S., Dennis M., Clarke B. E. (1994). Molecular and biological characterization of simian immunodeficiency virus macaque strain 32H proviral clones containing nef size variants. J Gen Virol 75, 529–543 10.1099/0022-1317-75-3-529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A., Kono K., Nomaguchi M., Yasutomi Y., Adachi A., Shioda T., Akari H., Nakayama E. E. (2012). Geographical, genetic and functional diversity of antiretroviral host factor TRIMCyp in cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis). J Gen Virol 93, 594–602 10.1099/vir.0.038075-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbings R., Berry N., Stott J., Hull R., Walker B., Lines J., Elsley W., Brown S., Wade-Evans A. & other authors (2004). Vaccination with live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus for 21 days protects against superinfection. Virology 330, 249–260 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbings R., Berry N., Waldmann H., Bird P., Hale G., Stott J., North D., Hull R., Hall J. & other authors (2005). CD8+ lymphocytes do not mediate protection against acute superinfection 20 days after vaccination with a live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol 79, 12264–12272 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12264-12272.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stremlau M., Owens C. M., Perron M. J., Kiessling M., Autissier P., Sodroski J. (2004). The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5α restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427, 848–853 10.1038/nature02343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi A. J., Coke C. S. (2007). Comparative phylogenetics offer new insights into the biogeographic history of Macaca fascicularis and the origin of the Mauritian macaques. Mol Phylogenet Evol 42, 498–504 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S. J., Webb B. L., Maplanka C., Newman R. M., Verschoor E. J., Heeney J. L., Towers G. J. (2008). Rhesus macaque TRIM5 alleles have divergent antiretroviral specificities. J Virol 82, 7243–7247 10.1128/JVI.00307-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyand M. S., Manson K., Montefiori D. C., Lifson J. D., Johnson R. P., Desrosiers R. C. (1999). Protection by live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus against heterologous challenge. J Virol 73, 8356–8363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap M. W., Nisole S., Lynch C., Stoye J. P. (2004). Trim5α protein restricts both HIV-1 and murine leukemia virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 10786–10791 10.1073/pnas.0402876101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylinen L. M., Price A. J., Rasaiyaah J., Hué S., Rose N. J., Marzetta F., James L. C., Towers G. J. (2010). Conformational adaptation of Asian macaque TRIMCyp directs lineage specific antiviral activity. PLoS Pathog 6, e1001062 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Hatziioannou T., Perez-Caballero D., Derse D., Bieniasz P. D. (2006). Antiretroviral potential of human tripartite motif-5 and related proteins. Virology 353, 396–409 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R., Nagy D., Mandel R. J., Naldini L., Trono D. (1997). Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 15, 871–875 10.1038/nbt0997-871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]