Abstract

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) of deer and elk is a highly communicable neurodegenerative disorder caused by prions. Investigations of CWD are hampered by slow bioassays in transgenic (Tg) mice. Towards the development of Tg mice that will be more susceptible to CWD prions, we created a series of chimeric elk/mouse transgenes that encode the N terminus of elk PrP (ElkPrP) up to residue Y168 and the C terminus of mouse PrP (MoPrP) beyond residue 169 (mouse numbering), designated Elk3M(SNIVVK). Between codons 169 and 219, six residues distinguish ElkPrP from MoPrP: N169S, T173N, V183I, I202V, I214V and R219K. Using chimeric elk/mouse PrP constructs, we generated 12 Tg mouse lines and determined incubation times after intracerebral inoculation with the mouse-passaged RML scrapie or Elk1P CWD prions. Unexpectedly, one Tg mouse line expressing Elk3M(SNIVVK) exhibited incubation times of <70 days when inoculated with RML prions; a second line had incubation times of <90 days. In contrast, mice expressing full-length ElkPrP had incubation periods of >250 days for RML prions. Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice were less susceptible to CWD prions than Tg(ElkPrP) mice. Changing three C-terminal mouse residues (202, 214 and 219) to those of elk doubled the incubation time for mouse RML prions and rendered the mice resistant to Elk1P CWD prions. Mutating an additional two residues from mouse to elk at codons 169 and 173 increased the incubation times for mouse prions to >300 days, but made the mice susceptible to CWD prions. Our findings highlight the role of C-terminal residues in PrP that control the susceptibility and replication of prions.

Introduction

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a fatal prion disease of the cervid family, including deer, elk and moose (Sigurdson, 2008; Williams, 2005). CWD is highly communicable among cervids. Over 90 % of deer and elk in closed domesticated and game herds have been reported to be infected with CWD prions (Williams, 2005). Why CWD is so contagious among cervids is unknown, but shedding of prions in faeces probably leads to grassland contamination (Tamgüney et al., 2009b). In addition, CWD prions have been identified in tissues and bodily secretions from both ill and asymptomatic animals; these include the central nervous system (CNS), the lymphoreticular system, muscle, blood and saliva (Angers et al., 2006; Fox et al., 2006; Mathiason et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2004; Nichols et al., 2009; Sigurdson et al., 1999; Tamgüney et al., 2012).

Prions are composed solely of PrPSc, an aberrantly folded, infectious isoform of the benign cellular prion protein (denoted PrPC). Conversion of PrPC to PrPSc probably requires direct interaction between the two conformers, in which PrPSc acts as a template or seed for PrPC (Prusiner et al., 1990). The formation of prions is influenced by many factors, including the genetic background of the host, expression levels of PrPC, the primary structures of both host PrPC and infecting PrPSc, and the strain of PrPSc (Barron et al., 2001; Carlson et al., 1988, 1989; Manson et al., 1999; Scott et al., 1989, 2005). Transmission experiments of CWD prion isolates from white-tailed deer, mule deer and elk to transgenic (Tg) mice expressing deer, elk, sheep, cattle or human PrPC suggest that the transmission barrier for CWD prions among different species of the cervid family is low, whereas the transmission barrier for CWD prions to sheep, cattle and humans is high (Browning et al., 2004; Kong et al., 2005; LaFauci et al., 2006; Tamgüney et al., 2006). In contrast, sheep and sheep-passaged bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) prions transmit readily to Tg mice expressing elk PrP (ElkPrP) (Green et al., 2008; Tamgüney et al., 2009a).

Tg mice expressing chimeric PrP molecules have facilitated studies of the species barrier and helped to identify critical PrP residues that control prion transmission or de novo prion generation (Giles et al., 2010, 2012; Korth et al., 2003; Scott et al., 1993; Telling et al., 1994, 1995). Residues at the C terminus of chimeric human/mouse PrP transgenes were identified to be critical in facilitating transmission of human prions to Tg mice (Telling et al., 1995). Introduction of elk residues S169N and N173T into mouse PrP (MoPrP; mouse numbering) was found to result in the de novo generation of transmissible prions in Tg mice (Sigurdson et al., 2009).

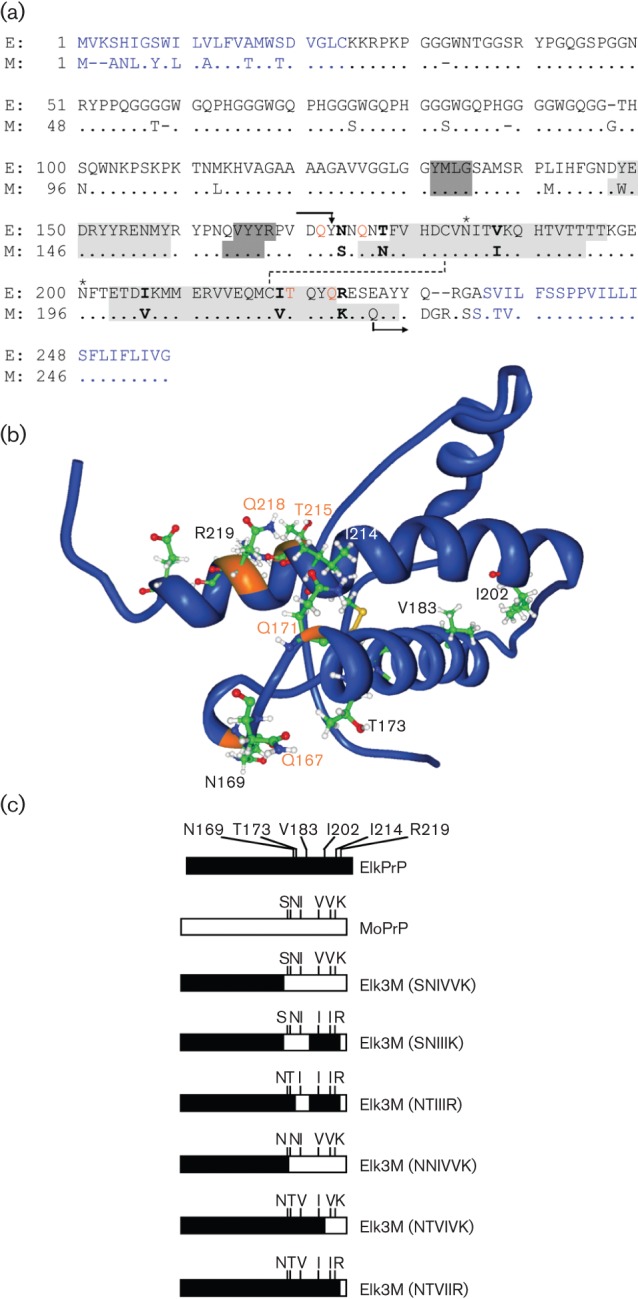

To interrogate further the role of the C-terminal residues in the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc, we created 12 Tg mouse lines on a background where the wild-type (wt) mouse PrP gene had been ablated (Büeler et al., 1992). We constructed a series of chimeric elk/mouse PrP transgenes that encode the N terminus of ElkPrP up to residue Y168 and the C terminus of MoPrP beyond residue 169 (mouse numbering), designated Elk3M(SNIVVK). Between codons 169 and 219, six residues distinguish ElkPrP from MoPrP: N169S, T173N, V183I, I202V, I214V and R219K (Fig. 1). For each Tg line, we determined incubation times after intracerebral inoculation with mouse-passaged scrapie (RML strain) or mouse-passaged CWD (Elk1P) prions. Unexpectedly, one Tg mouse line expressing Elk3M(SNIVVK) exhibited incubation times of <70 days when inoculated with mouse RML prions; a second line had incubation times of <90 days. In contrast, Tg mice expressing full-length ElkPrP had incubations of >250 days. The Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice were less susceptible to Elk1P prions than the Tg(ElkPrP) mice. We found that changing three C-terminal mouse residues (202, 214 and 219) to those of elk doubled the incubation time for mouse RML prions and rendered the mice resistant to Elk1P prions. Mutating an additional two residues from mouse to elk at codons 169 and 173 increased the incubation times for RML prions to >300 days, but made the mice susceptible to Elk1P prions.

Fig. 1.

(a) Amino acid alignment of PrP from American elk (E; Cervus elaphus nelsoni, UniProt ID: P67986) and mouse (M; Mus musculus, UniProt ID: P04925). N- and C-terminal signal peptides that are cleaved off from the mature protein are indicated in blue. All chimeric PrP molecules have the N terminus of ElkPrP up to residue Y168 and the C terminus of MoPrP beginning from Q222 (mouse numbering and indicated by arrows). Between codons 169 and 221, the ElkPrP and MoPrP sequences are identical, except at six residues indicated in bold. Elk3M(SNIVVK) expresses mouse residues at these six positions; one, some, or all mutations from mouse to elk amino acids were made. Residues forming the three α-helical domains of PrP are shaded in light grey and residues forming an antiparallel β-sheet in dark grey. Glycosylation sites are indicated by asterisks; a disulfide bridge is indicated by a dashed line. Residues controlling prion replication are shown in orange (Kaneko et al., 1997; Perrier et al., 2000, 2002; Zulianello et al., 2000). (b) Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of ElkPrP(124–234) (Gossert et al., 2005). Residues N169, T173, V183, I202, I214 and R219 (mouse numbering), which differ between elk and mouse PrP and were mutated in the chimeric PrP constructs in this study, are shown. Residues Q167, Q171, T215 and Q218, labelled in orange, are identical in elk and mouse PrP and control prion replication (Kaneko et al., 1997). (c) Schematic representation of ElkPrP (black), MoPrP (white) and chimeric elk/mouse PrP molecules expressed in Tg mice in these studies.

The results of the studies reported here not only highlight the critical role of the C-terminal residues in prion transmission from one species to another, but also argue for a more complex set of rules than was previously appreciated in studies of human and bovine prion transmission to Tg mice (Scott et al., 1993, 2005; Telling et al., 1995).

Results

Tg mice expressing chimeric elk/mouse PrP

Earlier, we and others established lines of Tg mice expressing PrPC from American elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) that are susceptible to infection with CWD prions (Browning et al., 2004; Kong et al., 2005; LaFauci et al., 2006; Tamgüney et al., 2006, 2009a). To study the influence of the C-terminal residues of ElkPrPC on conversion into PrPSc, we generated 12 Tg mouse lines expressing chimeric elk/mouse PrPC (Table 1). All chimeric PrP molecules had the same N terminus of ElkPrP up to residue Y168 (mouse numbering) and the C terminus of MoPrP beginning at Q222. Between codons 169 and 221, ElkPrP and MoPrP share the same sequence except at six codons: 169, 173, 183, 202, 214 and 219 (Fig. 1a, b). Chimeric PrP with mouse residues at all six C-terminal positions was designated Elk3M(SNIVVK). We generated five additional chimeric elk/mouse PrP constructs by reverting selected mouse residues at these six codons back to elk (Fig. 1c). In the 12 Tg mouse lines established from each of these chimeric PrP constructs, the mice expressed varying levels of chimeric PrPs (1–12×) relative to wt PrP in FVB/N mice (Table 1). Eleven of the 12 lines showed no signs of CNS dysfunction for >600 days (data not shown). One line, Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16033 mice, expressed chimeric PrP at a level 12-fold greater than that found for wt PrP in FVB/N mice; these mice developed spontaneous disease at a median age of 342 days, but did not show any proteinase K (PK)-resistant PrP by Western blotting, PrP aggregates by immunohistochemistry, or other distinguishing neuropathological lesions, and were excluded from further study (data not shown). We restricted our observation period to 600 days, because a few Tg mice from some lines develop spontaneous neurological dysfunction after this time (Telling et al., 1996; Colby et al. 2010).

Table 1. Transmission of RML and Elk1P prions in Tg mice expressing mouse, elk, and chimeric elk/mouse PrP.

c.i., Confidence interval.

| Mouse line* | PrP expression(fold)† | RML | Elk1P | ||

| Median incubation timewith 95 % c.i. (days) | n/n0‡ | Median incubation timewith 95 % c.i. (days)§ | n/n0‡ | ||

| FVB/N | 1 | 133 (119, 150) | 5/5 | 148, 189 | 2/8 |

| Tg(MoPrP)4053 | 8 | 54 (47, 57)|| | 8/8 | 127 (97, >600) | 4/6 |

| Tg(ElkPrP)12577 | 2 | 398 (280, 508)¶ | 6/6 | 123 (117, 132)# | 7/7 |

| Tg(ElkPrP+/+)12584 | 6 | 258 (165, 400) | 7/8 | 99 (84, 109)¶ | 10/10 |

| Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK)12316 | 3 | 67 (48, 71) | 7/8 | 119, 124 | 2/5 |

| Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK)12336 | 2–3 | 88 (83, 92) | 8/8 | 166 (111, >600) | 4/7 |

| Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR)23029 | 2–3 | 145 (134, 158) | 8/8 | 334 | 1/7 |

| Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR)23048 | 2–3 | 139 (132, 163) | 8/8 | >600 | 0/4 |

| Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR+/+)18108 | 1 | 378 (329, 539) | 4/5 | 350, 357 | 2/4 |

| Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR)20909 | 1 | 312 (256, 554) | 5/5 | 511 (482, >600) | 2/2 |

| Tg(Elk3M,NNIVVK)18401 | 1 | 193 (160, 202) | 8/8 | 364 (250, 473) | 7/7 |

| Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16048 | 4–6 | 216 (196, 225) | 8/8 | 439 (412, 498) | 7/7 |

| Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16036 | 2–3 | 231 (204, 260) | 8/8 | 389 (256, 404) | 6/6 |

| Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR)20840 | 4 | 330 (187, 482) | 5/5 | 265 (234, 394) | 7/7 |

| Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR)20841 | 2 | 368 (242, 498) | 5/7 | 246 (215, 300) | 8/8 |

Elk residues within the region of interest are shown in bold and underlined. Mice homozygous for the transgene are denoted by ‘+/+’.

Compared with PrPC in wild-type FVB/N mouse brain.

n, No. of ill animals; n0, no. of inoculated animals without intercurrent disease.

When fewer than half of the inoculated mice developed disease, individual incubation periods are listed in italics.

Data from Telling et al. (1996).

Data from Tamgüney et al. (2009a).

Data from Tamgüney et al. (2006).

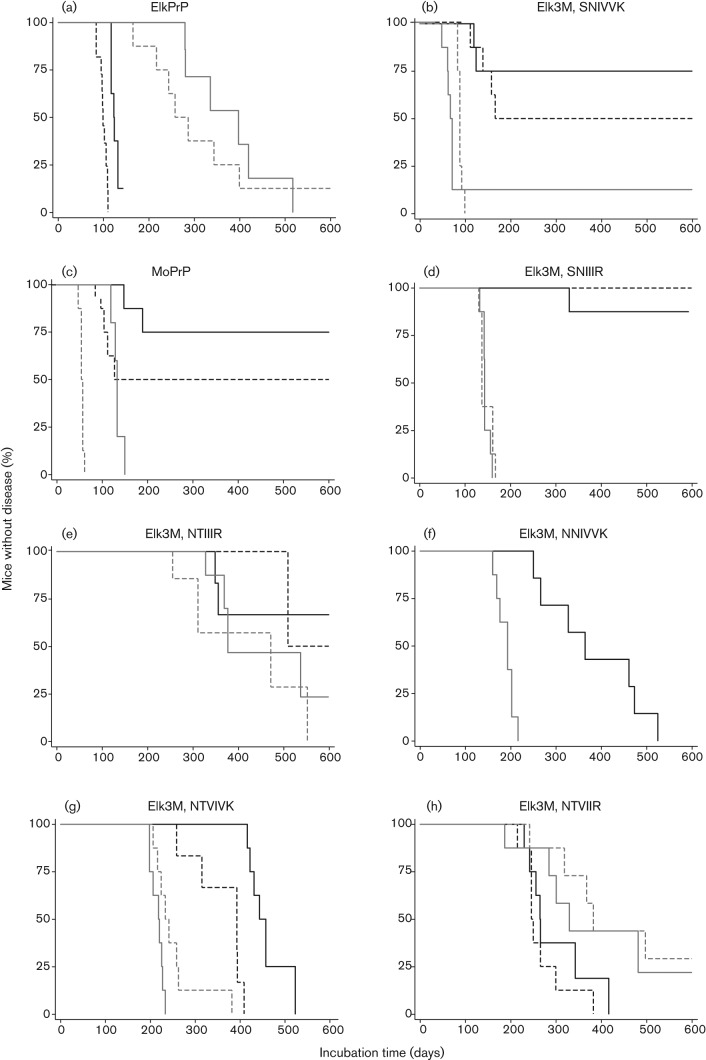

Transmission of prions to Tg mice expressing chimeric PrP

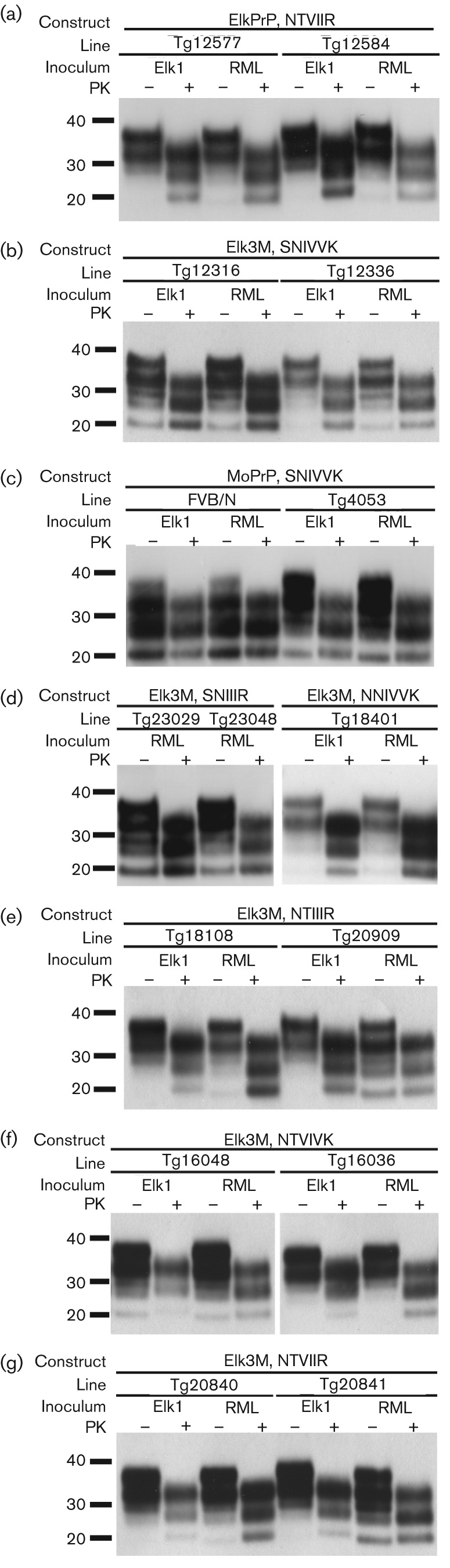

We inoculated Tg mice expressing ElkPrP, as well as Tg mice expressing chimeric elk/mouse PrP, with mouse RML prions or Elk1P prions, a CWD field isolate from elk that was passaged twice in Tg(ElkPrP+/+) mice (Table 1). Mouse RML prions transmitted disease to two lines of Tg(ElkPrP) mice, in 258 and 398 days (Fig. 2a). Unexpectedly, exchanging the C terminus of ElkPrP for MoPrP altered the susceptibility for RML prions, which caused disease in 67 and 88 days in two lines of Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice (Fig. 2b). While Elk1P prions transmitted CNS dysfunction to two Tg(ElkPrP) mouse lines in 99 and 123 days (Fig. 2a), their transmission to FVB, Tg(MoPrP-A)4053 and Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice was prolonged and inefficient (Fig. 2b, c, Table 1). Western blots of brain homogenates prepared from terminal, euthanized mice showed protease-resistant PrP 27–30 after limited digestion with PK (Fig. 3a–c).

Fig. 2.

Survival curves of mice following inoculation of RML (grey lines) and Elk1P (black lines) prions. Transmissions to (a) Tg(ElkPrP)12577 (solid lines) and Tg(ElkPrP+/+)12584 mice (dashed lines); (b) Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK)12316 (solid lines) and Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK)12336 mice (dashed lines); (c) FVB/N (solid lines) and Tg(MoPrP)4053 mice (dashed lines); (d) Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR)23029 (solid lines) and Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR)23048 mice (dashed lines); (e) Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR+/+)18108 (solid lines) and Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR)20909 mice (dashed lines); (f) Tg(Elk3M,NNIVVK)18401 mice; (g) Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16048 (solid lines) and Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16036 mice (dashed lines); and (h) Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR)20840 (solid lines) and Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR)20841 mice (dashed lines).

Fig. 3.

Western blot analyses of brain homogenates of mice following inoculation of Elk1P prions and RML prions. (a) Tg(ElkPrP)12577 and Tg(ElkPrP+/+)12548 mice expressing ElkPrP. (b) Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK)12316 and Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK)12336 mice expressing Elk3M with mouse residues (SNIVVK) at all six C-terminal positions. (c) FVB/N and Tg(MoPrP)4053 mice expressing MoPrP. (d) Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR)23029 and Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR)23048 mice expressing Elk3M with three mutations to ElkPrP, and Tg(Elk3M,NNIVVK)18401 mice expressing Elk3M with the S173N mutation. (e) Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR+/+)18108 and Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR)20909 mice expressing Elk3M with five mutations to ElkPrP. (f) Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16048 and Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16036 mice expressing Elk3M with four mutations to ElkPrP. (g) Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR)20840 and Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR)20841 mice expressing Elk3M with all six mutations to ElkPrP. In all panels, samples were either subjected to limited digestion with PK (+) or left undigested (−). Blots were probed using recFab HuM-P coupled to HRP. Apparent molecular masses based on migration of protein standards are shown in kDa.

Changing three C-terminal residues in Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice from mouse to elk generated Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR) mice. This change doubled the incubation time for mouse RML prions to 139 and 145 days, and rendered the mice resistant to Elk1P prions (Fig. 2d, Table 1). Western blot analysis showed PK-resistant PrPSc in the brains of Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR) mice inoculated with RML prions (Fig. 3d).

Introduction of two additional ElkPrP residues (total of five) into the C terminus prolonged the incubation times to 312 and 378 days in Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice after inoculation with RML prions (Fig. 2e, Table 1); the chimeric PrP expression levels in these Tg mice were 1×, similar to those found in FVB mice, which had an incubation period of 133 days (Table 1). In the Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice, five C-terminal mouse residues were converted to elk, and I183 remains mouse-specific (Fig. 1). Notably, the incubation times for RML prions in Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice were similar to those for Tg(ElkPrP) mice. However, the incubation times for Elk1P prions in the Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice were quite prolonged (>350 days) with not all mice becoming ill, compared with those in Tg(ElkPrP) mice, of 99 and 123 days (Table 1). Western blots of the brains of ill Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice inoculated with RML or Elk1P prions showed protease-resistant PrPSc (Fig. 3e).

Analysis of a single-residue change at the C terminus is provided by the Tg(Elk3M,NNIVVK) mice with a 1× level of transgene expression (Fig. 2f). Tg18401 mice expressed Elk3M(NNIVVK) at lower levels than the Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) lines (2–3×). Despite this lower expression level, all seven Tg(Elk3M,NNIVVK) mice inoculated with Elk1P prions developed disease after 364 days, compared with only 50 % of Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice developing signs of CNS dysfunction after Elk1P inoculation (Table 1). The brains of the Tg(Elk3M,NNIVVK) mice inoculated with RML or CWD prions harboured protease-resistant PrPSc (Fig. 3d).

Reverting four of six residues in Elk3M(SNIVVK) from mouse to elk produced a large increase in the incubation time of Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK) mice inoculated with mouse RML prions; these Tg mice became ill at 216 and 231 days (Fig. 2g, Table 1). Elk1P prions caused CNS dysfunction in the Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK) mice in 389 and 439 days. Western blotting of the brains of Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK) mice inoculated with RML or Elk1P prions showed protease-resistant PrPSc (Fig. 3f).

When the six C-terminal mouse residues in the Elk3M(SNIVVK) transgene were changed to elk, the resulting Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) mice had incubation times of 330 and 368 days (Fig. 2h, Table 1) after inoculation with mouse RML prions. These incubation times were similar to those observed in Tg(ElkPrP) mice (258 and 367 days) for RML prions (Table 1). Curiously, Elk1P prions resulted in prolonged incubation times in Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) mice, of 265 and 246 days (Table 1), compared with passage in Tg(ElkPrP) mice, with incubation periods of 99 and 123 days. Western blotting of brain homogenates from Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) (Fig. 3g) mice showed protease-resistant PrPSc after limited digestion. Interestingly, transmission of Elk1P prions to mice expressing Elk3M(SNIVVK) (Fig. 3b) and MoPrP (Fig. 3c) resulted in predominantly monoglycosylated PrP, whereas primarily diglycosylated PrP resulted following transmission to other lines.

Neuropathology in Tg mice

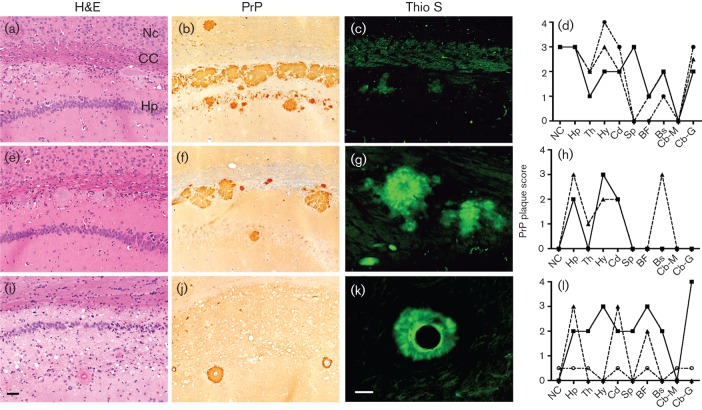

Histological analysis of the brain sections from symptomatic Tg mice expressing elk/mouse PrP inoculated with Elk1P prions showed deposition of PrPSc and reactive astrocytic gliosis characteristic of prion disease (Fig. 4). For the mice expressing Elk3M(SNIVVK), Elk3M(SNIIIR) or Elk3M(NNIVVK) constructs (data not shown), no distinguishing features were observed; however, other constructs led to distinct phenotypes. With inoculation of Elk1P prions, focal vacuolation occurred in a few regions of the brains of Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) and Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice (Fig. 4a, e), whereas vacuolation was distributed to all brain regions in Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK) mice (Fig. 4i). PrP plaques were found surrounding the lateral ventricles in Tg mice expressing Elk3M(NTVIIR) and Elk3M(NTIIIR) (Fig. 4b, f), but were also found with varying abundance throughout the brain (Fig. 4d, h). The largest number of plaques with the broadest brain distribution occurred in Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) mice (Fig. 4d). In comparison, the number and distribution of plaques were reduced by approximately 50 % in Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice (Fig. 4h). Different patterns of PrP deposition were identified in three Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK) mice (Fig. 4l): one resembled the pattern in Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) mice, one resembled the pattern in Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) mice, and the third mouse showed a completely different pattern, which consisted of PrP staining surrounding arteries and arterioles, and no freestanding plaques (Fig. 4l). To determine whether the PrP plaques are amyloid, they were stained with thioflavin S. The PrP plaques in Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) and Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK) mice (Fig. 4g, k) stained strongly with thioflavin S, and those in Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) mice stained weakly (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Neurohistology of Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR)20841 (a–d), Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR)20909 (e–h) and Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK)16306 (i–l) mice infected with Elk1P prions. Hippocampal sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to evaluate spongiform degeneration, nerve cell loss and plaque formation (a, e, i); immunostained for PrP (b, f, j); or stained with thioflavin S (Thio S) to determine whether the plaques formed amyloid (c, g, k). PrP plaque scores (d, h, l), based on PrP immunohistochemistry obtained from multiple brain regions, demonstrate that the three Tg mouse lines produced different quantities and distributions of PrP plaques; each line on the graphs indicates scores from an individual mouse. Bars, 50 µm [(i); applies to all the H&E-stained and PrP-immunostained sections]; 25 µm [(k); applies to all the Thio S-stained sections]. NC, Neocortex; CC, corpus callosum; Hp, hippocampus; Th, thalamus; Hy, hypothalamus; Cd, caudate nucleus; Sp, septum; BF, basal forebrain; Bs, brainstem; Cb-M, cerebellar cortex, molecular cell layer; Cb-G, cerebellar cortex, granule cell layer.

Discussion

Our findings show that single-residue substitutions in the C-terminal segment of PrP alter the susceptibility of Tg mice to a particular prion strain. The expression of elk residues in the C-terminal PrP segment plays a critical role in the formation of ElkPrPSc after infection with Elk1P prions. Based on earlier studies with chimeric PrP transgenes (Giles et al., 2010, 2012; Korth et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2005; Telling et al., 1995), we hypothesized that Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice would be more susceptible to cervid prions than Tg(ElkPrP) mice. Our finding that Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice are more susceptible to mouse RML prions than to Elk1P prions was unanticipated. Reverting individual residues in the mouse segment of Elk3M(SNIVVK) to elk did not create a strategy for constructing Tg mice with greater susceptibility to cervid prions. As expected, the incubation times for RML prions lengthened when the mouse residues in the C-terminal segment were mutated to elk. Notably, Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) and Tg(ElkPrP) mice showed greater than twofold differences in their incubation periods for Elk1P prions. These mice express PrP constructs that differ at four residues at the extreme C terminus, arguing that residues at the extreme C terminus control strain selectivity in prion replication.

Reverting mouse S169 in Elk3M(SNIVVK) to the elk residue (N) doubled the incubation time for RML prions but facilitated transmission of Elk1P prions, underscoring the importance of this residue for the formation of CWD prions (Table 1). Mutating S→N at residue 169 and N→T at 173 (mouse numbering) in MoPrP created a rigid loop that was first recognized when the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) solution structure of recombinant ElkPrP was solved (Gossert et al., 2005). The chimeric MoPrP(S169N,N173T) transgene led to spontaneous disease, which was transmissible (Sigurdson et al., 2009). The importance of N169 for CWD prion replication has also been emphasized in a protein misfolding cyclic amplification study, in which brain homogenates from species expressing N169 supported amplification of CWD prions and those expressing S173 did not, with only one exception (Kurt et al., 2009).

CWD prions passaged in Tg mice expressing ElkPrP generally show a glycosylation profile with a predominant band of diglycosylated PrP (Tamgüney et al., 2006). Here, transmission of Elk1P prions to Tg mice expressing MoPrP or Elk3M(SNIVVK) resulted in primarily monoglycosylated PrP. This observation may indicate a modification of the Elk1P prion strain following passage in some lines of mice. Strain adaptation may also become more evident should second passage of this inoculum result in shorter incubation times.

Because CWD prions cause widespread PrP amyloid deposition in the brains of cervids (Bahmanyar et al., 1985), we examined the amyloid in the brains of our mice. Tg mice expressing wt ElkPrP exhibited widespread PrP amyloid plaques after inoculation with CWD prions (Browning et al., 2004; Kong et al., 2005; Tamgüney et al., 2006; Trifilo et al., 2007). In the Tg lines expressing chimeric elk/mouse PrP and inoculated with Elk1P prions, the highest PrP plaque load was found in Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) mice, which express chimeric PrP that differs from ElkPrP at only four residues at the extreme C terminus. In Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR) and Tg(Elk3M,NTVIVK) mice expressing one or two, respectively, fewer C-terminal elk residues than Tg(Elk3M,NTVIIR) mice, the PrP plaque burden was lower after Elk1P inoculation (Fig. 4). In Tg mice expressing chimeric PrP with even fewer C-terminal elk residues [Tg(Elk3M,SNIIIR), Tg(Elk3M,NNIVVK) and Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice], PrP amyloid plaques were not found. Interestingly, this phenotype was not related to the incubation period (Table 1).

Because cervids are susceptible to experimental infection with scrapie and BSE prions, it will be important to ascertain whether any of the Tg mouse lines established here could be used to differentiate between scrapie, BSE and CWD prions in cervids (Hamir et al., 2004; Martin et al., 2009). In a recent report, the residue expressed at codon 169 in voles and mice was correlated with differential susceptibilities to scrapie and BSE prions (Agrimi et al., 2008). Previous work also showed that certain lines of Tg mice expressing chimeric bovine/mouse PrP were differentially susceptible to infection with BSE, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) and scrapie prions (Scott et al., 2005). The differential results for Elk1P and RML prions in these lines may help to unravel the complexity of the crucial residues for strain-specific transmission of prions. Defining the regulatory signals carried within the C-terminal region of PrP that influence PrPSc formation may aid in deciphering how prion strains are replicated with high fidelity as well as in developing effective therapeutics for CJD and other prion diseases.

Methods

Chimeric elk/mouse PrP constructs.

The ORFs encoding MoPrP-A and cervid PrP were cloned in earlier studies (Carlson et al., 1994; Tamgüney et al., 2006). The C-terminal sequence of cervid PrP was changed to that of MoPrP using a unique KpnI restriction site common to both PrP sequences, resulting in a chimeric PrP molecule encoding cervid PrP residues 1–95 and MoPrP thereafter (mouse numbering). All further mutations were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mutations were introduced sequentially at N96S, L108M, M137L and W144Y using the following respective oligonucleotides: 5′-GGGTCAAGGTGGTACCCATAGTCAGTGGAACAAGCCCAG-3′, 5′-CAAACCAAAAACCAACATGAAGCATGTGGCAGGGG-3′, 5′-CCATGAGCAGGCCCCTGATCCATTTTGGCAAC-3′ and 5′-GATCCATTTTGGCAACGACTACGAGGACCGCTACTACCG-3′. These four mutations changed the mouse residues to elk amino acids, extending the N-terminal ElkPrP sequence up to residue Y168; this construct was denoted Elk3M(SNIVVK). Using this Elk3M(SNIVVK) construct, up to six additional mutations were made at S169N, N173T, I183V, V202I, V214I and K219R with 5′-CAGTGGATCAGTACAACAACCAGAACACCTTCGTGCACGAC-3′ (for S169N and N173T); 5′-GACTGCGTCAATATCACCGTCAAGCAGCACACGGTC-3′ (for I183V); 5′-CTTCACCGAGACCGATATCAAGATGATGGAGCGCG-3′ (for V202I); and 5′-CAGATGTGCATCACCCAGTACCAGAGGGAGTCCCAGG-3′ (for V214I and K219R). The amino acids expressed in the resulting constructs are denoted following ‘Elk3M’.

Complete sequences of all constructs were determined and archived by using Vector NTI Advance software (Invitrogen).

Source of Tg mice.

All Tg mouse lines were generated using the cosSHa.Tet cosmid vector for transgenic expression as described previously (Scott et al., 1992). With the exception of Tg(MoPrP)4053 mice, all Tg mice originated from Zrch/Prnp0/0 mice that do not express endogenous MoPrP (Büeler et al., 1992), and were maintained by breeding with FVB/Prnp0/0 mice. Tg(MoPrP)4053 mice express endogenous PrP at 8× the level of wt FVB/N mice (Charles River Laboratories; Carlson et al., 1994). Tg(ElkPrP)12577 and Tg(ElkPrP+/+)12584 mice have been described previously (Tamgüney et al., 2006, 2009a). The Tg(Elk3M,NTIIIR+/+)18108 mice were made homozygous for the transgene by intercrossing the hemizygous line. All other lines used in this study are hemizygous.

Expression levels of PrP in the brain of all newly developed lines were determined by dot blot using serial dilutions of homogenate and compared with that of wt FVB/N mice (Scott et al., 1993). PrP was detected with the human/mouse (HuM) recombinant fragment antibody (recFab) P conjugated to HRP as described previously (Tamgüney et al., 2009a).

Nomenclature.

Tg(Elk3M,SNIVVK) mice express the chimeric Elk3M(SNIVVK) construct, which has the elk sequence up to residue 168 and mouse sequence beginning at residue 169 (mouse numbering). Tg mice expressing chimeric elk/mouse PrP constructs with mutations are designated by Elk3M, followed by the amino acids expressed at codons 169, 173, 183, 202, 214 and 219, respectively. The mouse PrP residues at these positions are SNIVVK; the elk residues are NTVIIR (Fig. 1). Mice homozygous for the transgene are denoted by ‘+/+’.

Prion isolates and transmission studies.

Elk1P was derived from the elk CWD isolate 03-12609 (Elk1, provided by Michael W. Miller, Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, CO, USA), characterized in an earlier study (Tamgüney et al., 2006), and maintained by passaging twice in Tg(ElkPrP+/+)12584 mice. Brain homogenates (10 %, w/v) in PBS from Tg(ElkPrP+/+)12584 mice infected with the serially passaged Elk1P inoculum were obtained by three 30 s strokes of a PowerGen homogenizer (Fisher Scientific).

The RML prion strain, which was derived from the Chandler isolate (Chandler, 1961) passaged in Swiss CD-1 mice (Charles River Laboratories) expressing MoPrP-A, was originally provided by William Hadlow, Rocky Mountain Laboratory, Hamilton, MT, USA. For RML prions, 10 % (w/v) brain homogenates in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free PBS (pH 7.4) were obtained by applying three repeated strokes of 15 s each using a Kinematica Polytron Generator with a PTA-20 tip (Brinkman Instruments).

Brain homogenates were diluted in 5 % (w/v) bovine albumin fraction V and PBS to obtain final 1 % (w/v) brain homogenates used for inoculation. Mice were inoculated with 30 µl 1 % (w/v) brain homogenate using a 27-gauge, disposable hypodermic syringe inserted into the right parietal lobe. The clinical status of inoculated mice was assessed daily and neurological dysfunction three times weekly. CNS dysfunction was determined based on standard diagnostic criteria; mice were euthanized following evidence of progressive neurological dysfunction (Carlson et al., 1988; Scott et al., 1993). All mouse studies were approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

The Kaplan–Meier function was used to calculate median incubation periods (Kaplan & Meier, 1958); mice with intercurrent illness were censored at the time of euthanasia, and 95 % confidence intervals (were determined (Brookmeyer & Crowley, 1982). Calculations were performed with Stata/IC 10.0 (StataCorp).

Western blotting.

For Western blotting analysis, 10 % (w/v) brain homogenates were prepared in PBS with 2 % (w/v) N-lauroylsarcosine sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich) by three runs of 15 s each in a Precellys 24 homogenizer (MO BIO Laboratories). Samples of 5 % brain homogenates were incubated with 20 µg PK ml−1 (New England Biolabs) for 1 h at 37 °C. PK was inactivated with 1 mM PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich) and samples were centrifuged at 100 000 g for 1 h at 4 °C. Pellets were resuspended in 100 µl PBS containing 2 % (w/v) N-lauroylsarcosine sodium salt, before 100 µl 2× NuPage LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) was added and the samples were boiled for 5 min. For electrophoresis, 5–20 µl undigested and PK-digested samples were loaded onto the gels. SDS gel electrophoresis and Western blotting were performed using NuPAGE Novex 4–12 % Bis-Tris gels and the iBlot dry blotting system (Invitrogen). PrP was detected with recFab HuM-P bound covalently to HRP (Safar et al., 2002) and developed with the enhanced chemiluminescent detection system (GE Healthcare Biosciences).

Neuropathology.

Mouse brains were removed and frozen on dry ice or immersion-fixed in 10 % buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Vacuolation was evaluated using 8 µm-thick brain sections that were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). PrPSc was detected in formalin-fixed tissue sections after hydrolytic autoclaving with recFab HuM-P, as described previously (Muramoto et al., 1997). PrP plaque scores were determined by assigning a value from 0 to 4 based on the number of plaques in the tissue section: ‘0’ indicates no plaques, ‘1’ denotes a few plaques, ‘2’ was given for some plaques, ‘3’ was assigned for a moderate number of plaques, and ‘4’ signifies many plaques. Thioflavin S staining of PrP amyloid plaques was performed as described previously (Tamgüney et al., 2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG02132, AG031220, AG10770), a cooperative agreement from the USDA, and gifts from the Sherman Fairchild Foundation and Robert Galvin. G. T. was supported by a fellowship from the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation. The authors thank the staff of the Hunters Point animal facility for support with the transgenic animal experiments, Conny Heinrich and Quinn Walker for microinjections, Azucena Lemus for histopathological preparations, Ana Serban for antibodies and Hang Nguyen for editorial assistance.

References

- Agrimi U., Nonno R., Dell’Omo G., Di Bari M. A., Conte M., Chiappini B., Esposito E., Di Guardo G., Windl O. & other authors (2008). Prion protein amino acid determinants of differential susceptibility and molecular feature of prion strains in mice and voles. PLoS Pathog 4, e1000113 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers R. C., Browning S. R., Seward T. S., Sigurdson C. J., Miller M. W., Hoover E. A., Telling G. C. (2006). Prions in skeletal muscles of deer with chronic wasting disease. Science 311, 1117 10.1126/science.1122864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanyar S., Williams E. S., Johnson F. B., Young S., Gajdusek D. C. (1985). Amyloid plaques in spongiform encephalopathy of mule deer. J Comp Pathol 95, 1–5 10.1016/0021-9975(85)90071-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron R. M., Thomson V., Jamieson E., Melton D. W., Ironside J., Will R., Manson J. C. (2001). Changing a single amino acid in the N-terminus of murine PrP alters TSE incubation time across three species barriers. EMBO J 20, 5070–5078 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R., Crowley J. (1982). A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics 38, 29–41 10.2307/2530286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browning S. R., Mason G. L., Seward T., Green M., Eliason G. A., Mathiason C., Miller M. W., Williams E. S., Hoover E., Telling G. C. (2004). Transmission of prions from mule deer and elk with chronic wasting disease to transgenic mice expressing cervid PrP. J Virol 78, 13345–13350 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13345-13350.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büeler H., Fischer M., Lang Y., Bluethmann H., Lipp H.-P., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B., Aguet M., Weissmann C. (1992). Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature 356, 577–582 10.1038/356577a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson G. A., Goodman P. A., Lovett M., Taylor B. A., Marshall S. T., Peterson-Torchia M., Westaway D., Prusiner S. B. (1988). Genetics and polymorphism of the mouse prion gene complex: control of scrapie incubation time. Mol Cell Biol 8, 5528–5540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson G. A., Westaway D., DeArmond S. J., Peterson-Torchia M., Prusiner S. B. (1989). Primary structure of prion protein may modify scrapie isolate properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86, 7475–7479 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson G. A., Ebeling C., Yang S.-L., Telling G., Torchia M., Groth D., Westaway D., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (1994). Prion isolate specified allotypic interactions between the cellular and scrapie prion proteins in congenic and transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91, 5690–5694 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler R. L. (1961). Encephalopathy in mice produced by inoculation with scrapie brain material. Lancet 277, 1378–1379 10.1016/S0140-6736(61)92008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby D. W., Wain R., Baskakov I. V., Legname G., Palmer C. G., Nguyen H. O., Lemus A., Cohen F. E., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2010). Protease-sensitive synthetic prions. PLoS Pathog 6, e1000736 10.1099/vir.0.83168-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. A., Jewell J. E., Williams E. S., Miller M. W. (2006). Patterns of PrPCWD accumulation during the course of chronic wasting disease infection in orally inoculated mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). J Gen Virol 87, 3451–3461 10.1099/vir.0.81999-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles K., Glidden D. V., Patel S., Korth C., Groth D., Lemus A., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2010). Human prion strain selection in transgenic mice. Ann Neurol 68, 151–161 10.1002/ana.22104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles K., De Nicola G. F., Patel S., Glidden D. V., Korth C., Oehler A., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2012). Identification of I137M and other mutations that modulate incubation periods for two human prion strains. J Virol 86, 6033–6041 10.1128/JVI.07027-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossert A. D., Bonjour S., Lysek D. A., Fiorito F., Wüthrich K. (2005). Prion protein NMR structures of elk and of mouse/elk hybrids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 646–650 10.1073/pnas.0409008102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green K. M., Browning S. R., Seward T. S., Jewell J. E., Ross D. L., Green M. A., Williams E. S., Hoover E. A., Telling G. C. (2008). The elk PRNP codon 132 polymorphism controls cervid and scrapie prion propagation. J Gen Virol 89, 598–608 10.1099/vir.0.83168-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamir A. N., Miller J. M., Cutlip R. C., Kunkle R. A., Jenny A. L., Stack M. J., Chaplin M. J., Richt J. A. (2004). Transmission of sheep scrapie to elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) by intracerebral inoculation: final outcome of the experiment. J Vet Diagn Invest 16, 316–321 10.1177/104063870401600410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko K., Zulianello L., Scott M., Cooper C. M., Wallace A. C., James T. L., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B. (1997). Evidence for protein X binding to a discontinuous epitope on the cellular prion protein during scrapie prion propagation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94, 10069–10074 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E. L., Meier P. (1958). Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53, 457–481 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q., Huang S., Zou W., Vanegas D., Wang M., Wu D., Yuan J., Zheng M., Bai H. & other authors (2005). Chronic wasting disease of elk: transmissibility to humans examined by transgenic mouse models. J Neurosci 25, 7944–7949 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2467-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korth C., Kaneko K., Groth D., Heye N., Telling G., Mastrianni J., Parchi P., Gambetti P., Will R. & other authors (2003). Abbreviated incubation times for human prions in mice expressing a chimeric mouse–human prion protein transgene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 4784–4789 10.1073/pnas.2627989100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt T. D., Telling G. C., Zabel M. D., Hoover E. A. (2009). Trans-species amplification of PrP(CWD) and correlation with rigid loop 170N. Virology 387, 235–243 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFauci G., Carp R. I., Meeker H. C., Ye X., Kim J. I., Natelli M., Cedeno M., Petersen R. B., Kascsak R., Rubenstein R. (2006). Passage of chronic wasting disease prion into transgenic mice expressing Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) PrPC. J Gen Virol 87, 3773–3780 10.1099/vir.0.82137-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson J. C., Jamieson E., Baybutt H., Tuzi N. L., Barron R., McConnell I., Somerville R., Ironside J., Will R. & other authors (1999). A single amino acid alteration (101L) introduced into murine PrP dramatically alters incubation time of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. EMBO J 18, 6855–6864 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S., Jeffrey M., González L., Sisó S., Reid H. W., Steele P., Dagleish M. P., Stack M. J., Chaplin M. J., Balachandran A. (2009). Immunohistochemical and biochemical characteristics of BSE and CWD in experimentally infected European red deer (Cervus elaphus elaphus). BMC Vet Res 5, 26 10.1186/1746-6148-5-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiason C. K., Powers J. G., Dahmes S. J., Osborn D. A., Miller K. V., Warren R. J., Mason G. L., Hays S. A., Hayes-Klug J. & other authors (2006). Infectious prions in the saliva and blood of deer with chronic wasting disease. Science 314, 133–136 10.1126/science.1132661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. W., Williams E. S., Hobbs N. T., Wolfe L. L. (2004). Environmental sources of prion transmission in mule deer. Emerg Infect Dis 10, 1003–1006 10.3201/eid1006.040010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto T., DeArmond S. J., Scott M., Telling G. C., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B. (1997). Heritable disorder resembling neuronal storage disease in mice expressing prion protein with deletion of an α-helix. Nat Med 3, 750–755 10.1038/nm0797-750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols T. A., Pulford B., Wyckoff A. C., Meyerett C., Michel B., Gertig K., Hoover E. A., Jewell J. E., Telling G. C., Zabel M. D. (2009). Detection of protease-resistant cervid prion protein in water from a CWD-endemic area. Prion 3, 171–183 10.4161/pri.3.3.9819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier V., Wallace A. C., Kaneko K., Safar J., Prusiner S. B., Cohen F. E. (2000). Mimicking dominant negative inhibition of prion replication through structure-based drug design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 6073–6078 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier V., Kaneko K., Safar J., Vergara J., Tremblay P., DeArmond S. J., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B., Wallace A. C. (2002). Dominant-negative inhibition of prion replication in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 13079–13084 10.1073/pnas.182425299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner S. B., Scott M., Foster D., Pan K.-M., Groth D., Mirenda C., Torchia M., Yang S.-L., Serban D. & other authors (1990). Transgenetic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell 63, 673–686 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90134-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safar J. G., Scott M., Monaghan J., Deering C., Didorenko S., Vergara J., Ball H., Legname G., Leclerc E. & other authors (2002). Measuring prions causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy or chronic wasting disease by immunoassays and transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol 20, 1147–1150 10.1038/nbt748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M., Foster D., Mirenda C., Serban D., Coufal F., Wälchli M., Torchia M., Groth D., Carlson G. & other authors (1989). Transgenic mice expressing hamster prion protein produce species-specific scrapie infectivity and amyloid plaques. Cell 59, 847–857 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90608-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M. R., Köhler R., Foster D., Prusiner S. B. (1992). Chimeric prion protein expression in cultured cells and transgenic mice. Protein Sci 1, 986–997 10.1002/pro.5560010804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M., Groth D., Foster D., Torchia M., Yang S.-L., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (1993). Propagation of prions with artificial properties in transgenic mice expressing chimeric PrP genes. Cell 73, 979–988 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90275-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M. R., Peretz D., Nguyen H.-O. B., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2005). Transmission barriers for bovine, ovine, and human prions in transgenic mice. J Virol 79, 5259–5271 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5259-5271.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson C. J. (2008). A prion disease of cervids: chronic wasting disease. Vet Res 39, 41 10.1051/vetres:2008018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson C. J., Williams E. S., Miller M. W., Spraker T. R., O’Rourke K. I., Hoover E. A. (1999). Oral transmission and early lymphoid tropism of chronic wasting disease PrPres in mule deer fawns (Odocoileus hemionus). J Gen Virol 80, 2757–2764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson C. J., Nilsson K. P., Hornemann S., Heikenwalder M., Manco G., Schwarz P., Ott D., Rülicke T., Liberski P. P. & other authors (2009). De novo generation of a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy by mouse transgenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 304–309 10.1073/pnas.0810680105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamgüney G., Giles K., Bouzamondo-Bernstein E., Bosque P. J., Miller M. W., Safar J., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2006). Transmission of elk and deer prions to transgenic mice. J Virol 80, 9104–9114 10.1128/JVI.00098-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamgüney G., Miller M. W., Giles K., Lemus A., Glidden D. V., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2009a). Transmission of scrapie and sheep-passaged bovine spongiform encephalopathy prions to transgenic mice expressing elk prion protein. J Gen Virol 90, 1035–1047 10.1099/vir.0.007500-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamgüney G., Miller M. W., Wolfe L. L., Sirochman T. M., Glidden D. V., Palmer C., Lemus A., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2009b). Asymptomatic deer excrete infectious prions in faeces. Nature 461, 529–532 10.1038/nature08289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamgüney G., Richt J. A., Hamir A. N., Greenlee J. J., Miller M. W., Wolfe L. L., Sirochman T. M., Young A. J., Glidden D. V. & other authors (2012). Salivary prions in sheep and deer. Prion 6, 52–61 10.4161/pri.6.1.16984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telling G. C., Scott M., Hsiao K. K., Foster D., Yang S.-L., Torchia M., Sidle K. C. L., Collinge J., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (1994). Transmission of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease from humans to transgenic mice expressing chimeric human–mouse prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91, 9936–9940 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telling G. C., Scott M., Mastrianni J., Gabizon R., Torchia M., Cohen F. E., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (1995). Prion propagation in mice expressing human and chimeric PrP transgenes implicates the interaction of cellular PrP with another protein. Cell 83, 79–90 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90236-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telling G. C., Haga T., Torchia M., Tremblay P., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (1996). Interactions between wild-type and mutant prion proteins modulate neurodegeneration in transgenic mice. Genes Dev 10, 1736–1750 10.1101/gad.10.14.1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifilo M. J., Ying G., Teng C., Oldstone M. B. (2007). Chronic wasting disease of deer and elk in transgenic mice: oral transmission and pathobiology. Virology 365, 136–143 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E. S. (2005). Chronic wasting disease. Vet Pathol 42, 530–549 10.1354/vp.42-5-530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulianello L., Kaneko K., Scott M., Erpel S., Han D., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B. (2000). Dominant-negative inhibition of prion formation diminished by deletion mutagenesis of the prion protein. J Virol 74, 4351–4360 10.1128/JVI.74.9.4351-4360.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]