Abstract

Pine wilt disease (PWD) caused by pine wood nematode (PWN), Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, is the most destructive diseases of pine and poses a threat of serious economic losses worldwide. Although several of the mechanisms involved in disease progression have been discovered, the molecular response of Pinus massoniana to PWN infection has not been explored. We constructed four subtractive suppression hybridization cDNA libraries by taking time-course samples from PWN-inoculated Masson pine trees. One-hundred forty-four significantly differentially expressed sequence tags (ESTs) were identified, and 124 high-quality sequences with transcriptional features were selected for gene ontology (GO) and individual gene analyses. There were marked differences in the types of transcripts, as well as in the timing and levels of transcript expression in the pine trees following PWN inoculation. Genes involved in signal transduction, transcription and translation and secondary metabolism were highly expressed after 24 h and 72 h, while stress response genes were highly expressed only after 72 h. Certain transcripts responding to PWN infection were discriminative; pathogenesis and cell wall-related genes were more abundant, while detoxification or redox process-related genes were less abundant. This study provides new insights into the molecular mechanisms that control the biochemical and physiological responses of pine trees to PWN infection, particularly during the initial stage of infection.

Keywords: pine wilt disease, differentially expressed genes, suppression subtractive hybridization, Pinus massoniana

1. Introduction

Pine wilt disease (PWD) is caused by the pine wood nematode (PWN), Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, which is believed to be native to North America. Previously, PWD only damaged exotic pine trees in North America, but it has recently spread to Asian and European countries, including Japan, China, South Korea and Portugal, and PWN was recently reported in Spain [1–3]. PWD is the most destructive pine disease, causing significant economic losses around the world, especially in Asia. PWD kills 1,000,000 m3 of pine trees annually in Japan [4] and damaged approximately 7811 ha of pines in Korea by 2005 [5]. In China, economic losses due to PWD were estimated to be 2.5 billion Chinese RMB (approximately 400 million USD) [6]. Pinus spp. are the main hosts of B. xylophilus, and Monochamus spp. beetles are a major vector, feeding on multiple pine trees and introducing the nematodes into the trees through feeding wounds [7]. Once the pine trees are infected, they are usually killed rapidly, and no effective treatment measures are available. Despite many advances on the study of PWD, the pathogenic mechanism of PWD has not been clearly defined.

PWD symptoms are thought to develop in distinct early and advanced stages. During the early stage, typical symptoms are observed near the inoculation site, such as necrosis and destruction of the cortex, phloem tissue and cambium; the destruction of cortex resin canals; the formation of wound periderm in the cortex parenchyma around the resin canals; and ethylene release [8]. During the advanced stage, ethylene production, cambium damage and xylem embolisms increase, ultimately resulting in wilting needles and the death of the tree [8–10].

Accompanying these symptoms, an innate hypersensitive reaction (HR) occurs, resulting in the release of phenolics, the synthesis of toxins and phytoalexins and the compartmentalization of xylem and other tissues, followed by the flooding of the tracheid with oleoresin and toxic substances [9]. Further studies have shown that the HR is activated by a genetic program, wherein resistance genes recognize certain effectors and initiate a resistance response that is frequently linked to rapid cell death [11].

Certain high throughput screening procedures, including suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) and cDNA microarray technologies, have been used to identify differentially expressed genes in the plant-nematode interaction system [5,12,13]. In particular, comparative transcriptomic analyses with confirmation by Illumina deep sequencing have introduced a novel technique for the study of plant response to nematode infection [14,15]. Recent studies have revealed many molecular genetic events associated with PWD progression using such high throughput screening procedures. Shin et al. [5] isolated and analyzed upregulated or newly induced genes in PWN-inoculated Japanese red pine (P. densiflora) using an annealing control primer system and SSH. Significant changes in abundance were found for gene transcripts related to defense, secondary metabolism and transcription. As the disease progressed, other gene transcripts encoding pathogenesis-related proteins were expressed. In addition, pinosylvin synthases and metallothioneins were also more abundant in PWN-inoculated trees than in non-inoculated trees [5]. Santos et al. [12] identified expressed sequence tags (ESTs) in P. pinaster and P. pinea that were inoculated with PWN using the SSH technique and found that a tree defense response occurred at the molecular level at the initial stage of the disease; this response involved mainly the oxidative stress response, the production of lignin and ethylene and the posttranscriptional regulation of nucleic acids. Hirao et al. [13] constructed seven SSH P. thunbergii cDNA libraries from trees after inoculation with PWN and discovered that the expression levels of antimicrobial peptide and putative pathogenesis-related genes (e.g., PR-1b, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) were much higher in susceptible trees at every time point, whereas the expression levels of PR-9, PR-10 and cell wall-related genes (e.g., hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein precursor and extensin) were higher in resistant trees. The physiological changes that occur as PWD progresses have been characterized anatomically and biochemically, but the genetic events, such as changes in transcript profiles that may be associated with physiological changes, are poorly understood.

Masson pine (P. massoniana) is one of the most extensively distributed pine species in China. Most of these trees are found in pure forests. Unfortunately, these forests have been severely damaged by PWD because of Masson pine’s high susceptibility to PWD. The disease has spread during the last three decades and has caused serious damage to this particular species [6]. However, the response of the Masson pine to PWN infection at the molecular level has not been elucidated. In this study, we constructed four SSH libraries from Masson pines at two stages, 24 h and 72 h post-PWD inoculation. Control inoculations were performed with water to compare Masson pine gene expression patterns in response to PWN infection. The genes that were regulated by PWN inoculation were identified by comparing libraries, and the interesting results from the 24 h and 72 h treatments were further studied with real-time quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis.

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of cDNA Libraries Constructed by SSH

To identify the P. massoniana genes that were differentially expressed during the early response stages of PWN inoculation, four SSH libraries were constructed using mRNAs from PWN-inoculated and water-inoculated stems that were sampled at 24 h and 72 h after inoculation (PM-24h and PM-72h, respectively). From each library, 384 clones were selected randomly for dot-blot hybridization. A total of 665 dots (339 dots for the two PM-24h SSH libraries and 326 dots for the two PM-72h SSH libraries) were identified as significantly differentially expressed genes between PWN-inoculated and water-inoculated P. massoniana based on a normalized PWN-inoculation/water-inoculation signal intensity ratio with more than 2.0 or less than 0.5 (Table S1). A total of 144 spots, including 61 dots for the two PM-24h SSH libraries and 83 dots for the two PM-72h SSH libraries, were sequenced. After removing the low-quality region, vector and adaptor sequences, 124 high-quality sequences of the 144 sequences from the four libraries were selected for further analysis (Table S1). A total of five contigs and 32 singletons were present in the two PM-24h SSH libraries and the contigs comprised 23 ESTs, with a redundancy of 42%. The two PM-72h SSH libraries contained 49 unique ESTs, including four contigs and 45 singletons, with 35% redundancy. The insert length varied from 132 to 1051 bp, and the median length ranged from 428 to 459 bp, depending on the library. Summaries of the library data are shown in Table 1. The EST sequences have been deposited in the NCBI dbEST database (accession numbers JZ349248 to JZ349371).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the subtractive suppression hybridization (SSH) libraries.

| PM-24 h | PM-72 h | |

|---|---|---|

| Library and EST summary | ||

| Number of cDNAs sequenced | 61 | 83 |

| Mean read length 1 | 458.5 | 427.6 |

| Number of high-quality ESTs | 55 | 69 |

|

| ||

| Clustering results | ||

| Number of assembled ESTs 2 | 23 | 24 |

| Number of contigs (A) | 5 | 4 |

| Number of singletons (B) | 32 | 45 |

| Number of assembled sequences (A + B) | 37 | 49 |

|

| ||

| Contig sizes | ||

| 2–4 ESTs 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 5–7 ESTs | 1 | 1 |

| 8–13 ESTs | 1 | 0 |

| >14 ESTs | 0 | 1 |

Mean EST length after vector masking and end trimming;

The EST assembly parameters were 75% minimum match with a 30-base minimum overlap;

ESTs, expressed sequence tags.

2.2. Functional Classification and Identification of differentially Expressed Genes in PWN-Inoculated P. massoniana Trees

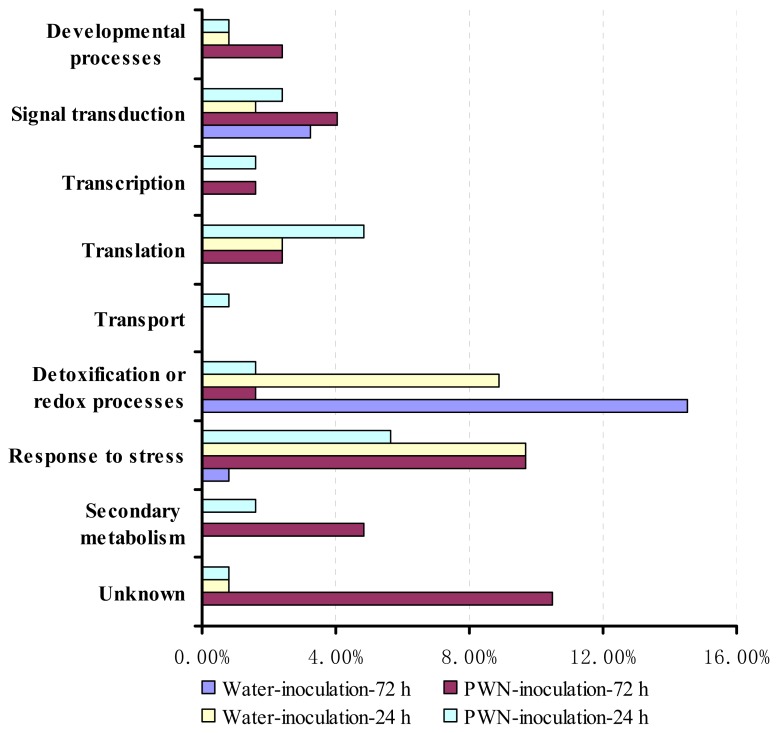

We classified and analyzed the genes from the four SSH libraries according to the gene ontology (GO) classes of their closest orthologues in Arabidopsis. These genes were involved in developmental processes, signal transduction, transcription and translation, transport, detoxification or redox processes and responses to stress and secondary metabolism after inoculation (Figure 1). However, genes involved in signal transduction, transcription and translation and secondary metabolism were highly expressed after 24 h and 72 h, while genes involved in transport were highly expressed only after 24 h. During PWD development, stress response genes were highly expressed only after 72 h; in addition, genes involved in developmental processes and several unknown genes were also highly expressed only after 72 h. In addition to the GO analysis, we also performed individual gene analyses to examine the relationships of the differentially expressed genes to the biochemical and physiological responses of trees during the early stages after PWN inoculation. The most noteworthy of these genes are shown in Table 2 and are reviewed in the Discussion section.

Figure 1.

Functional classification of the ESTs from the SSH libraries. For library construction, the mRNAs from pine wood nematode (PWN)-inoculated Pinus massoniana stems that were sampled at 24 h and 72 h after inoculation were used as the tester set, and the mRNAs from water-inoculated stems were used as the driver set.

Table 2.

Characterization of genes selected from subtractive suppression hybridization (SSH) libraries constructed with mRNA from PWN-inoculated Pinus massoniana stems sampled at 24 h and 72 h after PWN inoculation. The signal ratio indicates the normalized PWN-inoculation/water-inoculation ratio.

| PM-24h | PM-72h | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Clone ID | BLASTX | E Value | Signal intensity ratio | Clustered EST No. | Clone ID | BLASTX | E Value | Signal intensity ratio | Clustered EST No. |

| Developmental process | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| PMXY 148 | Pectin methylesterase 6 Arabidopsis AT4G02330.1 |

6 × 10−84 | 2.07 (Upregulated) | PMXY 165 | No pollen germination 1 Arabidopsis AT2G43040.1 |

1 × 10−7 | 2.06 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 120 | Polygalacturonase Arabidopsis AT1G80170.1 |

4 × 10−18 | 0.10 (Downregulated) | PMXY 155 | Acyl carrier protein 4 Arabidopsis AT4G25050.1 |

9 × 10−28 | 2.30 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 186 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 11A3 Arabidopsis AT2G24270.4 |

2 × 10−15 | 2.02 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Signal transduction | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| PMXY 121 | Jasmonate ZIM domain-containing Arabidopsis AT1G74950.1 |

2 × 10−3 | 2.14 (Upregulated) | Contig 01 | Calcium-binding protein Arabidopsis AT2G46600.1 |

2 × 10−25 | 0.11 (Downregulated) | 4 | |

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 131 | Calreticulin 1a Arabidopsis AT1G56340.2 |

1 × 10−123 | 2.10 (Upregulated) | PMXY 153 | Calcium-binding protein Arabidopsis AT2G46600.1 |

3 × 10−12 | 2.48 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 130 | Phosphate-responsive protein Arabidopsis AT4G08950.1 |

1 × 10−36 | 2.10 (Upregulated) | PMXY 205 | Jasmonate ZIM domain-containing Arabidopsis AT1G19180.2 |

8 × 10−3 | 2.47 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 099 | Phosphoesterase family protein Arabidopsis AT2G26870.1 |

4 × 10−28 | 0.08 (Downregulated) | PMXY 160 | Response regulator 3 Arabidopsis AT1G59940.1 |

1 × 10−35 | 2.01 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 108 | Phosphatidylinositol n-acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit p Arabidopsis AT2G39445.1 |

2 × 10−37 | 0.12 (Downregulated) | PMXY 167 | RAB GTPase homolog A2D Arabidopsis AT5G59150.1 |

3 × 10−29 | 2.19 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 210 | Phosphate-responsive protein Arabidopsis AT4G08950.1 |

2 × 10−40 | 2.05 (Up-regulated) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Transcription | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| PMXY 151 | PHD finger family protein Arabidopsis AT2G02470.2 |

3 × 10−48 | 2.03 (Upregulated) | PMXY 173 | C3HC4-type RING finger protein Arabidopsis AT5G22920.1 |

4 × 10−20 | 2.15 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 147 | Zinc finger protein (C2H2 type) Arabidopsis AT2G28200.1 |

1 × 10−3 | 2.43 (Upregulated) | PMXY 192 | La domain-containing protein Arabidopsis AT4G32720.2 |

8 × 10−17 | 2.30 (Upregulated) | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Translation | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| PMXY 139 | 60S ribosomal protein L10 Arabidopsis AT1G26910.1 |

2 × 10−38 | 2.17 (Upregulated) | PMXY 204 | 60S ribosomal protein L38 Arabidopsis AT3G59540.1 |

2 × 10−8 | 2.65 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 126 | 60S ribosomal protein L24 Arabidopsis AT2G36620.1 |

1 × 10−51 | 2.33 (Upregulated) | PMXY 212 | Serine-rich proteins Arabidopsis AT3G56500.1 |

8 × 10−7 | 2.15 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 141 | 60S ribosomal protein L29 Arabidopsis AT5G02610.1 |

5 × 10−54 | 2.08 (Upregulated) | PMXY 185 | GTP-binding Elongation factor Tu family protein Arabidopsis AT5G60390.3 |

6 × 10−86 | 2.04 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 142 | 60S ribosomal protein L27a-2 Arabidopsis AT1G23290.1 |

1 × 10−51 | 2.37 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 133 | 40S ribosomal protein S11-2 Arabidopsis AT3G48930.1 |

1 × 10−41 | 2.23 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 140 | Translation initiation factor eIF-4A Arabidopsis AT3G13920.4 |

1 × 10−142 | 2.50 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 098 | RNA-binding protein Nova-1-like Arabidopsis AT5G04430.1 |

5 × 10−9 | 0.09 (Down-regulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 089 | RNA recognition motif (RRM)-containing protein Arabidopsis AT1G14340.1 |

3 × 10−5 | 0.08 (Down-regulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 107 | 60S ribosomal protein L15 Arabidopsis AT4G16720.1 |

2 × 10−7 | 0.05 (Down-regulated) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Transport | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| PMXY 124 | TOM1-like protein 2-like isoform 2 Arabidopsis AT4G32760.2 |

4 × 10−24 | 2.31 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Detoxification or redox processes | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Contig 02 | Metallothionein 3 Arabidopsis AT3G15353.1 |

6 × 10−9 | 0.04 (Downregulated) | 11 | Contig 03 | Heavy-metal-associated domaincontaining protein Arabidopsis AT1G01490.2 |

1 × 10−6 | 0.10 (Downregulated) | 3 |

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 134 | Glutathione peroxidase Arabidopsis AT4G11600.1 |

2 × 10−71 | 2.48 (Upregulated) | Contig 04 | Metallothionein 3 Arabidopsis AT3G15353.1 |

6 × 10−9 | 0.09 (Downregulated) 15 | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 136 | 2-alkenal reductase Arabidopsis AT5G16970 |

3 × 10−23 | 2.05 (Upregulated) | PMXY 168 | Glyoxalase 1 family protein Arabidopsis AT1G15380.2 |

3 × 10−12 | 2.29 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 170 | Cyt_b561_FRRS1-likecontaining protein Picea sitchensis ADM73751.1 |

2 × 10−4 | 2.04 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Response to stress | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Contig 05 | Thaumatin-like family protein Arabidopsis AT4G11650.1 |

4 × 10−15 | 2.55 (Upregulated) | 2 | Contig 09 | Mannose/glucose-specific lectin Arabidopsis AT1G19715.3 |

8 × 10−14 | 1.73 (Upregulated) | 2 |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Contig 06 | Heat shock protein 18.2 Arabidopsis AT5G59720.1 |

6 × 10−42 | 0.10 (Downregulated) | 2 | PMXY 172 | Heat shock protein 70 Arabidopsis AT5G02500.1 |

8 × 10−59 | 2.06 (Upregulated) | |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Contig 07 | Calcium-binding protein lp8 Arabidopsis AT1G24620.1 |

9 × 10−20 | 0.04 (Downregulated) | 5 | PMXY 190 | AAA-type ATPase family protein Arabidopsis AT4G02480.1 |

2 × 10−21 | 2.21 (Upregulated) | |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Contig 08 | Drought stress responsive protein Pinus pinaster AJ309123.1 |

6 × 10−97 | 0.10 (Downregulated) | 3 | PMXY 189 | Cell-wall protein (lp5) Pinus sylvestris EU394126.1 |

2 × 10−4 | 2.42 (Upregulated) | |

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 127 | Thaumatin-like family protein Arabidopsis AT4G11650.1 |

3 × 10−16 | 5.60 (Upregulated) | PMXY 156 | BCL-2-associated athanogene 6 Arabidopsis AT2G46240.1 |

3 × 10−6 | 2.14 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 135 | Dirigent-like protein Arabidopsis AT4G11190.1 |

0.77 | 2.39 (Upregulated) | PMXY 195 | Ubiquitin family protein Arabidopsis AT4G02890.4 |

1 × 10−111 | 2.19 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 128 | Chitin recognition protein Arabidopsis AT3G04720.1 |

1 × 10−15 | 8.41 (Upregulated) | PMXY 196 | Ubiquitin-like conjugating enzyme Arabidopsis AT1G64230.5 |

6 × 10−52 | 2.23 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 146 | Chitinase Arabidopsis AT2G43590.1 |

2 × 10−20 | 2.45 (Upregulated) | PMXY 158 | Lipid transfer protein Arabidopsis AT5G59310.1 |

1 × 10−11 | 2.47 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 145 | Heat shock protein 90 Arabidopsis AT5G52640.1 |

1 × 10−65 | 2.33 (Upregulated) | PMXY 209 | Adenine nucleotide alpha hydrolase-like superfamily protein Arabidopsis AT5G14680.1 |

6 × 10−43 | 2.11 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 103 | High mobility group B3 Arabidopsis AT1G20696.3 |

1 × 10−31 | 0.03 (Downregulated) | PMXY 201 | RPS 2 protein Arabidopsis AT4G26090.1 |

6 × 10−6 | 2.04 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 088 | Heat shock protein 101 Arabidopsis AT1G74310.1 |

6 × 10−10 | 0.11 (Downregulated) | PMXY 181 | Pentatricopeptide (PPR) repeatcontaining protein Arabidopsis AT2G22070.1 |

3 × 10−22 | 2.35 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 214 | Aluminum-induced protein with YGL and LRDR motifs Arabidopsis AT5G19140.1 |

1 × 10−33 | 0.14 (Downregulated) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Secondary metabolism | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| PMXY 149 | Methionine synthase 2 Arabidopsis AT3G03780.3 |

1 × 10−120 | 2.28 (Upregulated) | PMXY 166 | Methionine synthase 2 Arabidopsis AT3G03780.3 |

3 × 10−59 | 2.52 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|

||||||||

| PMXY 129 | FAD/NAD(P)-binding oxidoreductase family protein Arabidopsis AT2G35660.1 |

1 × 10−22 | 2.11 (Upregulated) | PMXY 202 | Caffeic acid Omethyltransferase Pinus taeda AAC49708.1 |

2 × 10−12 | 2.08 (Upregulated) | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 152 | Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 5 Arabidopsis AT4G34230.1 |

9 × 10−48 | 2.42 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 187 | Chalcone and stilbene synthase family protein Arabidopsis AT5G13930.1 |

1 × 10−35 | 2.17 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 211 | Caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase Pinus taeda AF036095.1 |

3 × 10−76 | 2.19 (Upregulated) | ||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| PMXY 183 | Phenylcoumaran benzylic ether reductase Pinus taeda AF242490.2 |

1 × 10−94 | 2.26 (Upregulated) | ||||||

Fifty-two upregulated genes were identified in P. massoniana trees at 24 h and 72 h after PWN inoculation. Twenty genes were identified as upregulated at only 24 h after inoculation. Of these genes, six were involved stress responses, including genes encoding dirigent-like protein, heat-shock protein (HSP) 90 and PR proteins, such as thaumatin-like family protein (PR-5), chitin recognition protein (PR-4) and chitinase (PR-3). Two upregulated genes were involved in detoxification or redox processes: glutathione peroxidase and 2-alkenal reductase. One upregulated gene, FAD/NAD(P)-binding oxidoreductase family protein, was involved in secondary metabolism. Twenty-nine genes were upregulated only at 72 h after inoculation. Of these genes, 11 were involved in stress responses: mannose/glucose-specific lectin, HSP 70, AAA-type ATPase family protein, cell-wall protein (lp5), BCL-2-associated athanogene 6, ubiquitin family protein, ubiquitin conjugating-like enzyme, lipid transfer protein (PR-14), adenine nucleotide alpha hydrolase-like superfamily protein, RPS 2 protein and pentatricopeptide (PPR) repeat-containing protein. Two upregulated genes were involved in detoxification or redox processes: glyoxalase 1 family protein and Cyt_b561_FRRS1-like-containing protein. Five upregulated genes were involved in secondary metabolism: cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (CAD), chalcone and stilbene synthase family protein (CHS), caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT), caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase (CCoAOMT) and phenylcoumaran benzylic ether reductase (PCBER). Genes encoding the jasmonate ZIM domain-containing protein PMXY 121, PMXY 205, the phosphate-responsive protein, PMXY 130, PMXY 210, and methionine synthase 2 PMXY 149, PMXY 166 were upregulated at both 24 h and 72 h after inoculation (Table 2).

In contrast, 15 genes were identified as downregulated in PWN-inoculated P. massoniana trees 24 h and 72 h after inoculation. Eleven genes exhibited decreased expression at only 24 h after inoculation. Of these genes, five were involved in stress responses: HSP 18.2, HSP 101, calcium binding protein lp8, drought stress responsive protein and high mobility group B3. Three genes exhibited decreased expression only at 72 h after inoculation. Of these genes, one gene encoding an aluminum-induced protein with YGL and LRDR motifs was classified as a stress response gene and one gene encoding a heavy metal-associated domain-containing protein was classified as a detoxification or redox process gene. Genes encoding metallothionein 3 Contig 02 and Contig 04 were downregulated at both 24 h and 72 h after PWN inoculation (Table 2).

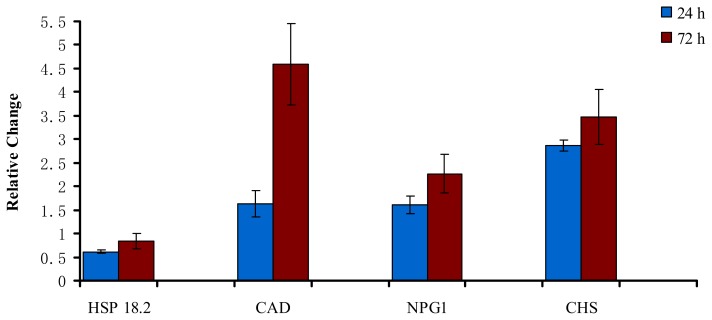

2.3. Validation of Differential Expression using Selected SSH Clones and qRT-PCR

To confirm the reliability of the SSH results, four genes were selected and analyzed by qRT-PCR to evaluate the changes in their expression in response to PWN inoculation. These genes were either upregulated or downregulated in PWN-inoculated P. massoniana trees at 24 h and 72 h after inoculation. One selected downregulated gene was HSP 18.2 (Contig 06), which was involved in stress responses at 24 h after inoculation. The three selected upregulated genes were upregulated only at 72 h: no pollen germination 1 (NPG1) (PMXY 165), which is involved in developmental processes and CAD (PMXY 152) and CHS (PMXY 187), both of which are involved in secondary metabolism.

The qRT-PCR data confirmed that NPG1, CAD and CHS were upregulated in PWN-inoculated trees, and that the expression levels were gene-specific, ranging from 1.60 to 4.54 (Figure 2). The three genes were upregulated at both 24 h and 72 h, and the expression levels of the three genes were much higher at 72 h than at 24 h (Figure 2). Although the expression levels of HSP 18.2 were higher at 72 h than at 24 h, this gene was downregulated both at 24 h and at 72 h in PWN-inoculated P. massoniana trees. Overall, the results of the qRT-PCR analysis were consistent with the SSH analysis.

Figure 2.

Quantitative real-time PCR of transcripts that were differentially expressed at 24 h and 72 h from PWN-inoculated Masson pine trees. The change is expressed as the relative difference in gene expression between the PWN-inoculated sample and the water-inoculated sample.

3. Discussion

To examine the gene expression profiles of P. massoniana in response to PWN inoculation, we constructed four SSH libraries from PWN- and water-inoculated P. massoniana stems sampled at 24 h and 72 h after inoculation. Overall, GO analysis showed that genes involved in signal transduction, transcription, translation and secondary metabolism were more highly expressed in PWN-inoculated trees than in water-inoculated trees at both 24 h and 72 h, and genes involved in stress responses were only more highly expressed in the PWN-inoculated trees at 72 h. However, genes that were involved in detoxification or redox processes were expressed at lower levels in PWN-inoculated trees than in the water-inoculated trees at both 24 h and 72 h (Figure 1). These results suggest that genes involved in responses to stress and secondary metabolism were expressed in the early stage of the P. massoniana response to PWN infection.

Genes encoding PR proteins were found to be highly expressed in P. massoniana after PWN inoculation, including PR-3 (chitinase, PMXY 146), PR-4 (chitin recognition protein, PMXY 128), PR-5 (thaumatin-like protein, Contig 05, PMXY 127) and PR-14 (lipid transfer protein, PMXY 158) (Figure 1, Table 2). PR proteins are expressed by host plants in response to pathological stimuli, and they normally accumulate not only locally, at the site of inoculation, but also systemically following exposure to biotic and abiotic stress factors [16]. PRs have been confirmed to be involved in pine and PWN interactions. Studies have revealed that PR gene expression was induced more quickly and to a higher level in the early stages of pine responses to PWN infection [5,13,17]. PR-2 (β-1,3-glucanase-like protein), PR-3 and PR-4 are thought to be involved in degrading the cell walls of fungal pathogens from the Ceratocystis genus, which are known to infect pine trees concomitantly with PWN [18]. PR-5 proteins exhibit antifungal activity by binding to (1,3)-β-d-glucans [19,20]. In this study, PR-3, PR-4 and PR-5 were found to be upregulated in the PM-24h library, indicating the response of P. massoniana to PWN infection. In addition, PR-14 (lipid transfer protein) produces a direct cytotoxic effect on fungal cells that is mediated by membrane permeabilization and inhibits fungal growth [21]. The gene that encodes PR-14 was found to be upregulated in P. pinaster at 3 h and 24 h after PWN inoculation [12,22] and was also found to be upregulated in P. massoniana 72 h after PWD infestation in our study.

Mannose/glucose-specific lectin and HSP 70, which are associated with stress responses, were also upregulated in P. massoniana at 72 h after PWD infection (Figure 1, Table 2). Plant lectins are entomotoxic proteins that are present in many species, and they participate in a general defense against a multitude of plant pathogens, including nematodes [23]. Ricin B-related lectin expression was upregulated in PWN-infected P. pinea [22]. HSP 70 is required for the folding of nascent proteins and intracellular transportation in addition to stress responses [24]. In the interaction between soybean plants and soybean cyst nematodes, Klink et al. [25] observed the induction of HSP 70 and reactive oxygen species (ROS) responsive genes, such as lipoxygenase and superoxidase dismutase, characteristic in response to soybean cyst nematode infection, suggesting that HSP 70 may contribute to maintaining a properly functioning environment for other defense responses.

Many genes that are involved in detoxification and redox processes were identified by the present study. During PWN invasion, metabolites released by the action of enzymes in nematode saliva, such as cellulase [26], as well as the host’s own secondary metabolites, which are normally restricted to specialized cells or subcellular compartments, can trigger the exposure of plant cells to highly toxic oxygen species [27]. We identified a number of genes that were involved in oxidative stress, including those encoding metallothionein 3 (Contig 02 downregulated in PM-24h and Contig 04 downregulated in PM-72h), a heavy metal-associated domain-containing protein (Contig 03 downregulated in PM-72h), GPX (PMXY 134 upregulated in PM-24h), 2-alkenal reductase (PMXY 136 upregulated in PM-24h), glyoxalase 1 family protein (PMXY 168 upregulated in PM-72h) and Cyt_b561_ FRRS1-like-containing protein (PMXY 170 upregulated in PM-72h) (Figure 1, Table 2).

A novel NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase 2-alkenal reductase gene was upregulated in the PM-24h library in this study. This protein can catalyze the reduction of reactive carbonyls that are produced by biomembrane lipid peroxidation in PWN-inoculated pine trees [28–32]. In addition, an aldo/keto reductase, an NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase that is involved in the detoxification of reactive carbonyls [33], was shown to be induced at 24 h after PWD-infection in P. pinaster [22]. The 2-alkenal reductase appears to play an important role in the antioxidative defense during the early stages following PWN inoculation.

The GPX gene is induced in maritime pine seedlings in response to water deficits and can catalyze the oxidation of glutathione in the presence of H2O2 to yield oxidized glutathione and water [34]. A GPX gene was found to be upregulated in the PM-24h library in our study. A cytochrome b561 gene was also upregulated in the PM-72h library. Cytochrome b561 is believed to catalyze the reduction of monodehydroascorbate (MDHA), resulting in the generation of a fully reduced ascorbate molecule [35]. These two molecules of reduced ascorbate can be used to reduce H2O2 to water by l-ascorbate peroxidase (APX), with the concomitant regeneration of two molecules of MDHA [36]. The APX gene has been verified to respond to PWN infection in PWN-inoculated Japanese red pine [5]. Therefore, the accumulation of GPX and Cyt_b561_FRRS1-like-containing protein provides evidence of H2O2 increases during the early stages following PWN inoculation in P. massoniana trees.

Metallothioneins are involved in metal homeostasis and heavy metal detoxification, and they are highly expressed in tissues under intense oxidative stress [37]. In the Norway spruce (Picea abies), metallothioneins accumulate in the needles under ozone stress and have been implicated in the maintenance of intracellular redox potential via the detoxification of ROS [38]. However, in our study, genes encoding metallothionein 3 (Contig 02 in PM-24 h and Contig 04 in PM-72 h) and a heavy metal-associated domain-containing protein (Contig 03 in PM-72 h) were identified as downregulated in the early stages of PWD progression in P. massoniana (Table 2). Hirao et al. [13] also reported that an EST that putatively encodes a metallothionein-like protein was significantly downregulated in susceptible P. thunbergii trees at 1 and 3 d. The response of such genes in P. massoniana and P. thunbergii suggests that they are likely involved in susceptible pine responses to PWN.

Genes involved in detoxification or redox processes were found to be induced at both 24 h and 72 h in PWN-inoculated P. massoniana trees in this study (Figure 1, Table 2). Shin et al. [5] found that genes related to oxidative stress were strongly induced or upregulated by PWN infection, implying that the inoculated trees were under severe oxidative stress during the nematode infection process. However, the upregulation of oxidative stress-related proteins is believed to play important roles in the maintenance of intracellular redox balance and in stress response/tolerance. Thus, the observed oxidative stress-related responses indicated that ROS accumulation and defense signaling may have been induced by 24 h or 72 h in the PWN-infected trees. Hirao et al. [13] proposed that the rapid induction of defense response genes, such as PR protein-encoding genes, is induced by oxidative stress-related gene expression during the early stage of PWN infection, and our study provides evidence from P. massoniana to support this hypothesis.

Secondary metabolites are important defense agents in conifers [5,13]. In this study, many genes involved in secondary metabolism responded to PWN inoculation, including the genes encoding methionine synthase 2, CAD, PCBER, COMT, CCoAOMT, CHS and other enzymes (Table 2). These proteins are specifically responsible for the production of secondary metabolites related to the phenylpropanoid pathway, flavonoid/stilbenoid pathway and the lignin biosynthetic pathway. Anatomical studies of PWN infection have demonstrated the accumulation of lignin and suberin-like substances around the resin canals in the cortex [39,40]. In our study, five genes encoding the lignin pathway components, methionine synthase 2, CAD, PCBER, COMT and CCoAOMT, were upregulated at 72 h after PWN inoculation. In addition, a dirigent-like protein gene was also upregulated at 24 h after PWD inoculation. The dirigent-like protein can mediate stereospecific lignin precursor couplings in association with H2O2 and may be involved in cell wall modification/lignification [41,42]. Cell wall-mediated resistance is the first line of plant defense against pathogens. Therefore, these findings indicate that the activation of resistant genes is associated with lignin synthesis. The upregulation of cell wall-related genes contributes to the strength of cell walls, providing a very effective defense against PWN infection; these events may restrict PWN migration. Despite these findings, the role of these genes in secondary metabolism in relation to PWN infection remains unclear [13,43,44].

Transcriptional regulators are key factors in the expression of specific genes, and they ensure cellular responses to internal and external stimuli [45,46]. In response to PWN inoculation, significant changes in the expression of genes associated with defense, detoxification or redox processes and secondary metabolism were observed, implying that these genes are transcriptionally regulated. Therefore, we analyzed the expression levels of several transcription factors in the four libraries. Genes encoding putative PHD finger family proteins and zinc finger proteins (C2H2 type) were found to be upregulated in the PM-24h library and genes encoding C3HC4-type RING finger proteins, and a putative La domain-containing protein were found to be upregulated in the PM-72h library. Thus, these regulators were differentially expressed in PWN-inoculated P. massoniana trees and could control the biochemical and physiological responses of P. massoniana to PWN infection. The transcription factors that were associated with PWN infection, and their regulation patterns in relation to downstream genes should be studied further.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Plant Material and Nematode Culture

Non-resistant (non-selected) 50 cm tall three-year-old P. massoniana trees, which were obtained from the Laoshan Forest Farm of Chun’an County in Zhejiang, China, were potted at the Research Institute of Subtropical Forestry in Zhejiang, China in June 2008. The P. massoniana trees were maintained in an environmental growth chamber with a relative humidity of 80%, a photoperiod of 16 h and temperatures of 26–30 °C for three months before inoculation. The PWN isolate B. xylophilus BXY03 was originally isolated from a diseased P. massoniana tree and confirmed as virulent using an inoculation test. The B. xylophilus BXY03 was then reared on fungal hyphae of Botrytis cinerea, which were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium at 25 °C for 7 days. Prior to inoculation, the PWNs were re-isolated from the medium using the Baermann funnel method [47].

4.2. PWN Inoculation and Sampling Time

P. massoniana trees were inoculated as described by Futai and Furuno [48]. In brief, a suspension of 1500 nematodes was pipetted into a small longitudinal wound (3–5 cm) made with a scalpel on the main stem, approximately 10 cm above the soil level. The inoculated wounds were covered with Parafilm to prevent the inoculum from drying. Sterile water (without nematodes) was applied to similarly injured P. massoniana trees as mock-infected samples. Stem tissues from 5 cm below the inoculated stem site were collected from the inoculated and mock-infected samples at 24 h and 72 h after inoculation. A 2 cm segment (from 5 cm to 7 cm below the inoculated stem site) of each stem was cut, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

4.3. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Saplings of three-year-old P. massoniana were used for inoculation with B. xylophilus BXY03. One longitudinal wound (approximately 3–5 mm) on each stem at 10 cm high of the sapling was made using a sterilized scalpel, and a suspension of 1500 nematodes was pipetted into each wound. Then, the inoculated wounds were sealed with parafilm to prevent desiccation and contamination. Stems inoculated with sterile water were used as control. Stem tissues with 2 cm length, from 5 cm to 7 cm below the inoculation site, were collected from each stem at 24 h and 72 h after inoculation and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen for further RNA extraction (Figure S1). Total RNA was isolated from the stem samples using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) by following the protocol. The integrity and purity of the isolated RNA were evaluated using 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry with GeneQuant (GeneQuant II, Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA). cDNAs were synthesized using a Super SMART PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.4. Construction of SSH Libraries and Dot-Blot Hybridization

SSH libraries were constructed using a PCR-Select cDNA Subtraction Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). Four subtractive libraries were constructed from samples taken from PWN and water-inoculated P. massoniana trees at 24 h and 72 h after inoculation, including forward (i.e., PWN-inoculated treatment as the tester and the water-inoculated control as the driver) and reverse (i.e., water-inoculated treatment as the tester and the PWN-inoculated control as the driver) subtracted libraries. The SSH cDNA libraries were constructed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, tester and driver cDNAs were digested with RsaI and ligated to adaptors and two hybridizations and two PCR amplifications were performed to enrich the differentially expressed sequences. The secondary PCR products were purified and inserted into a pMD-18-T Easy Vector (TaKaRa, Otsu, Shiga, Japan), which was then transformed into Escherichia coli DH5a competent cells. Blue/white selection was conducted with Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing ampicillin, isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and X-gal. A set of 384 white clones was randomly selected from each SSH cDNA library and differentially expressed cDNA fragments were amplified by nested PCR with nested primer 1 (5′-TCGAGCGGCCGCCCGGAGGT-3′) and nested primer 2 (5′-AGCGTG GTCGCGGCCGAGGT-3′). Following amplification, 0.6 μL of each PCR product from the two SSH libraries from samples taken at the same times were spotted onto a nylon membrane (Millipore, St. Charles, MO, USA) and pre-hybridized at 68 °C for 2 to 3 h. Two types of probes were generated from the 2nd round of subtracted PCR products, which were produced using the same method that was used to construct the SSH libraries; the samples were digested with RsaI and labelled with P32. The two types of probes were then hybridized with two of the same pre-hybridized nylon membranes at 68 °C for 14 h, followed by washing and incubation with a chromogenic reagent. A ScanArray 4000 Standard Biochip Scanning System and its QuantArray software (Packard Biochip Technologies, Inc: Billerica, MA, USA) were applied for scanning and data capturing. Differentially expressed genes were selected randomly based on a normalized PWN-inoculation/water-inoculation signal intensity ratio with more than 2.0 or less than 0.5.

4.5. DNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

The clones that were identified by dot-blot hybridization were sequenced using an automated ABI 3730 DNA sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Vector masking and trimming, as well as adaptor removal, were performed with the online VecScreen tool [49]. Contaminating bacterial, mitochondrial and ribosomal RNA genes were identified by a BLASTN search and were removed along with sequences of <100 bases and E > 1. The DNA sequence assembly program CAP3 [50] was used to assemble the ESTs into contigs with 75% minimum homology and a 30 base minimum overlap. The BLASTX algorithm was used to perform similarity searches of the individual and clustered ESTs against the GenBank non-redundant Arabidopsis databases. Gene ontology (GO) annotation analysis [51] was used for the functional assignment of matched genes.

4.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

To verify that the library gene results reflected true differential expression, qRT-PCR was performed using the total RNA that were initially isolated for SSH library construction. Gene-specific primers for 18S rRNA, HSP 18.2 (Contig 06), CAD (PMXY 152), NPG1 (PMXY 165) and CHS (PMXY 187) were designed with Primer Express 2.0 (Table 3). After reverse transcription with AMV reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, Otsu, Shiga, Japan), the reaction product was diluted 100-fold with sterile water. Primer specificity was confirmed by standard PCR and electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel, and the reaction efficiency was evaluated relative to standard curves generated from four samples from a 10 × dilution series. Real-time qPCR was performed in an Applied Biosystems ABI 7500 Real-Time System with SYBR Green. For each reaction of 20 μL, 2 μL of diluted cDNA was used. The Standard Cycling Program described in the user manual was used for amplification. Melting curve profiles were analyzed to ensure single product amplification, and the PCR products were reconfirmed by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel to verify the generation of a single product of the expected size. Each sample was tested in triplicate. Transcript abundance was normalized to that of 18S rRNA using the ΔΔCt method, as described previously [52], and the data for each gene in the PWN-inoculated samples were compared with the data from water-inoculated samples.

Table 3.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Candidate gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| Heat-shock protein 18.2 (HSP 18.2) | 5′-TCATACCGCGTGAGAGGTCAA-3′ 5′-AAGGCGAGCATGGAAAACG-3′ |

| Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) | 5′-AGCATGGAGGAAGCACAGGAA-3′ 5′-TCCATGGCCGTGTTGATGTAG-3′ |

| No pollen germination 1 (NPG1) | 5′-TTGGAGCTGTATCATGCAGCC-3′ 5′-CACCAGTTGACCAATGGAAGC-3′ |

| Chalcone and stilbene synthase family protein (CHS) | 5′-GGATCCAGATTCAACTTCGCC-3′ 5′-TGGTTGAGGCATTCCAGCA-3′ |

| 18S rRNA | 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′ 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′ |

5. Conclusions

Pine wilt disease, caused by B. xylophilus, is the most destructive pine disease. The host plant, P. massoniana, is extensively distributed across China, and it is highly susceptible to severe damage by PWD. To assess the pine molecular genetics associated with PWD, i.e., the transcriptional changes in P. massoniana trees following PWN infection, we constructed four subtractive suppression hybridization (SSH) cDNA libraries using time-course sampling of PWN-inoculated Masson pine trees. The genes that exhibited differential expression in response to PWN inoculation were identified by comparing these different libraries. Markedly different transcript profiles were found following PWN inoculation. These genes were mainly related to defense, secondary metabolism and transcription. Certain transcripts were differentially regulated in response to infection; pathogenesis-related genes and cell wall-related genes were upregulated, while detoxification or redox process-related genes were downregulated. The expression levels of genes of interest were compared between 24 h and 72 h and further analyzed by qRT-PCR to confirm differential gene expression.

Because the molecular response of the Masson pine to PWN infection was previously unknown, these results provided novel and fundamental information about the molecular response of the Masson pine to PWN infection and provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the biochemical and physiological responses of pine trees after PWN infection, particularly at the initial stage following infection.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This project was financially supported by the Special Research Programs for Non-profit Forestry of the State Forestry Administration (201204501, 200904061).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tokushige Y., Kiyohara T. Bursaphelenchus sp. in the wood of dead pine trees. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 1969;51:193–195. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang L., Ye J., Wu X., Xu X., Sheng J., Zhou Q. Detection of pine wood nematode using a real-time PCR assay to target the DNA topoisomerase I gene. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2010;127:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicente C., Espada M., Vieira P., Mota M. Pine Wilt Disease: A threat to European forestry. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012;133:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forestry Agency. Annual Report on Trends of Forest and Forestry-Fiscal Year 2003. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan; Tokyo, Japan: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin H., Lee H., Woo K.S., Noh E.W., Koo Y.B., Lee K.J. Identification of genes upregulated by pinewood nematode inoculation in Japanese red pine. Tree Physiol. 2009;29:411–421. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpn034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang B.J., Pan H.Y., Tang J., Wang Y.Y., Wang L.F., Wang Q. Pine Wood Nematode Disease. Chinese Forestry Press; Beijing, China: 2003. pp. 6–143. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones J.T., Moens M., Mota M., Li H., Kikuchi T. Bursaphelenchus xylophilus: Opportunities in comparative genomics and molecular host-parasite interactions. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008;9:357–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda K. Physiological process of the symptom development and resistance mechanism in pine wilt disease. J. For. Res. 1997;2:171–181. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers R.F. Pathogenesis in pine wilt caused by pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. J. Nematol. 1988;20:236–244. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukuda K., Utsuzawa S., Sakaue D. Correlation between acoustic emission, water status and xylem embolism in pine wilt disease. Tree Physiol. 2007;27:969–976. doi: 10.1093/treephys/27.7.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiffer R., Görg R., Jarosch B., Beckhove U., Bahrenberg G., Kogel K.H., Schulze-Lefert P. Tissue dependence and differential cordycepin sensitivity of race-specific resistance responses in the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:830–839. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos C.S.S., Vasconcelos M.W. Identification of genes differentially expressed in Pinus pinaster and Pinus pinea after infection with the pine wood nematode. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012;132:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirao T., Fukatsu E., Watanabe A. Characterization of resistance to pine wood nematode infection in Pinus thunbergii using suppression subtractive hybridization. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsye P.D., Kumar R., Hosseini P., Jones C.M., Tremblay A., Alkharouf N.W., Matthews B.F., Klink V.P. Mapping cell fate decisions that occur during soybean defense responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011;77:513–528. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsye P.D., Lawrence G.W., Youssef R.M., Kim K.H., Lawrence K.S., Matthews B.F., Klink V.P. The expression of a naturally occurring, truncated allele of an α-SNAP gene suppresses plant parasitic nematode infection. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012;80:131–155. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9932-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherer N.M., Thompson C.E., Freitas L.B., Bonatto S.L., Salzano F.M. Patterns of molecular evolution in pathogenesis-related proteins. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2005;28:645–653. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nose M., Shiraishi S. Comparison of the gene expression profiles of resistant and non-resistant Japanese black pine inoculated with pine wood nematode using a modified LongSAGE technique. For. Path. 2011;41:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wingfield M.J. Fungi associated with the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, and cerambycid beetles in Wisconsin. Mycologia. 1987;79:325–328. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osmond R.I.W., Hrmova M., Fontaine F., Imberty A., Fincher G.B. Binding interactions between barley thaumatin-like proteins and (1,3)-β-d-glucans. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:4190–4199. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zamani A., Sturrock R., Ekramoddoullah A.K.M., Wiseman S.B., Griffith M. Endochitinase activity in the apoplastic fluid of Phellinus weirii-infected Douglas-fir and its association with over wintering and antifreeze activity. For. Pathol. 2003;33:299–316. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regente M.C., Giudici A.M., Villalaín J., de la Canal L. The cytotoxic properties of a plant lipid transfer protein involve membrane permeabilization of target cells. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;40:183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos C.S.S., Pinheiro M., Silva A.I., Egas C., Vasconcelos M.W. Searching for resistance genes to Bursaphelenchus xylophilus using high throughput screening. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:599. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandenborre G., Smagghe G., van Damme E.J.M. Plant lectins as defense proteins against phytophagous insects. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:1538–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanzaki H., Saitoh H., Ito A., Fujisawa S., Kamoun S., Katou S., Yoshioka H., Terauchi R. Cytosolic HSP90 and HSP70 are essential components of INF1-mediated hypersensitive response and non-host resistance to Pseudomonas cichorii in Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2003;4:383–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klink V.P., Overall C.C., Alkharouf N.W., MacDonald M.H., Matthews B.F. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) and comparative microarray expression analysis of syncytial cells isolated from incompatible and compatible soybean (Glycine max) roots infected by the soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) Planta. 2007;226:1389–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0578-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q., Bai G., Yang W., Li H., Xiong H. Pathogenic cellulase assay of pine wilt disease and immunological localization. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006;70:2727–2732. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ralph S., Park J.Y., Bohlmann J., Mansfield S.D. Dirigent proteins in conifer defense: Gene discovery, phylogeny, and differential wound- and insect-induced expression of a family of DIR and DIR-like genes in spruce (Picea spp.) Plant Mol. Biol. 2006;60:21–40. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2226-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bidlack W.R., Tappel A.L. Fluorescent products of phospholipids during lipid peroxidation. Lipids. 1973;8:203–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02544636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato S., Misawa T. Lipid peroxidation during the appearance of hypersensitive reaction in cowpea leaves infected with cucumber mosaic virus. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 1976;42:472–480. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhindsa R.S., Plumb-dhindsa P., Thorpe T.A. Leaf senescence: Correlated with increased levels of membrane permeability and lipid peroxidation, and decreased levels of superoxide dismutase and catalase. J. Exp. Bot. 1981;32:93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Futai K. Pine Wilt Is an Epidemic Disease in Forests: Notes on the Interrelationship of Forest Microbes. Bun-ichi Sogo Shyuppan; Tokyo, Japan: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mano J., Belles-Boix E., Babiychuk E., Inzé D., Torii Y., Hiraoka E., Takimoto K., Slooten L., Asada K., Kushnir S. Protection against photooxidative injury of tobacco leaves by 2-Alkenal reductase. Detoxication of lipid peroxide-derived reactive carbonyls. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1773–1783. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamauchi Y., Hasegawa A., Taninaka A., Mizutani M., Sugimoto Y. NADPH-dependent reductases involved in the detoxification of reactive carbonyls in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:6999–7009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Breusegem F., Vranová E., Dat J.F., Inzé D. The role of active oxygen species in plant signal transduction. Plant Sci. 2001;161:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verelst W., Asard H. A phylogenetic study of cytochrome b561 proteins. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R38. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-6-r38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noctor G., Foyer C.H. Ascorbate and glutathione: Keeping active oxygen under control. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998;49:249–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mir G., Demenech J., Huguet G., Guo W.J., Goldsbrough P., Atrian S., Molinas M. A plant type 2 metallothionein (MT) from cork tissue responds to oxidative stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2004;55:2483–2493. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Etscheid M., Klumper S., Riesner D. Accumulation of a metallothionein-like mRNA in Norway spruce under environmental stress. J. Phytopathol. 1999;147:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishida K., Hogetsu T., Fukuda K., Suzuki K. Cortical responses in Japanese black pine to attack by the pine wood nematode. Can. J. Bot. 1993;71:1399–1405. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hückelhoven R. Cell wall-associated mechanisms of disease resistance and susceptibility. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2007;45:101–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.45.062806.094325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afzal A.J., Natarajan A., Saini N., Iqbal M.J., Geisler M., El Shemy H.A., Mungur R., Willmitzer L., Lightfoot D.A. The nematode resistance allele at the rhg1 locus alters the proteome and primary metabolism of soybean roots. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1264–1280. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burlat V., Kwon M., Davin L.B., Lewis N.G. Dirigent proteins and dirigent sites in lignifying tissues. Phytochmistry. 2001;57:883–897. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keen N.T. The molecular biology of disease resistance. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992;19:109–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00015609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ithal N., Recknor J., Nettleton D., Hearne L., Maier T., Baum T.J., Mitchum M.G. Parallel genome-wide expression profiling of host and pathogen during soybean cyst nematode infection of soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:293–305. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-3-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen W., Provart N.J., Glazebrook J., Katagiri F., Chang H.S., Eulgem T., Mauch F., Luan S., Zou G., Whitham S.A., et al. Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative functions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell. 2002;14:559–574. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ulker B., Somssich I.E. WRKY transcription factors: From DNA binding towards biological function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004;7:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayoub S.M. Plant Nematology: An Agricultural Training Aid. NemaAid Publication; Sacramento, CA, USA: 1980. p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Futai K., Furuno T. The variety of resistances among pine species to pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus lignicolus. Bull. Kyoto Univ. For. 1979;51:23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Online VecScreen Tool. [(accessed on 28 March 2013)]. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/VecScreen/VecScreen.html.

- 50.Huang X., Madan A. CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 1999;9:868–877. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.9.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gene Ontology (GO) Annotation Analysis. [(accessed on 1 April 2013)]. Available online: http://www.arabidopsis.org.

- 52.Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2002–2007. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.