Abstract

Objectives To identify independent predictors of outcome in patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) of the paranasal sinuses and skull base.

Design Meta-analysis of the literature and data from the International ACC Study Group.

Setting University-affiliated medical center.

Participants The study group consisted of 520 patients, 99 of them from the international cohort. The median follow-up period was 60 months (range, 32 to 100 months).

Main Outcome Measures Overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS).

Results The 5-year OS and DSS of the entire cohort were 62% and 67%, respectively. The local recurrence rate was 36.6%, and the regional recurrence rate was 7%. Distant metastasis, most commonly present in the lung, was recorded in 106 patients (29.1%). In the international cohort, positive margins and ACC of the sphenoid or ethmoidal sinuses were significant predictors of outcome (p < 0.001). Perineural invasion and adjuvant treatment (radiotherapy or chemoradiation) were not associated with prognosis.

Conclusion Tumor margin status and tumor site are associated with prognosis in ACC of the paranasal sinuses, whereas perineural invasion is not. Adjuvant treatment apparently has no impact on outcome.

Keywords: adenoid cystic carcinoma, paranasal sinuses, skull base, meta analysis, survival

Introduction

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) accounts for 3 to 5% of all head and neck malignancies.1 It is characterized by an intermediate growth rate, low probability of lymphatic spread, and frequent lung metastases.2 The overall survival (OS) rate of localized ACC that originates in the major salivary glands and minor oral cavity salivary glands are 93.9% and 92.4%, respectively, whereas survival rates for metastatic disease are 43.3% and 55.4%, respectively.1 However, ACC of the paranasal sinuses and skull base represent a pathology with distinct clinical implications.3 Those tumors are typically diagnosed late, and their proximity to vital structures (e.g., dura, brain, orbit, and central nerves) makes adequate oncological resection less likely.4 Another characteristic of ACC of the paranasal sinuses is perineural spread, with an incidence of over 50%.3 Due to the high propensity of local invasion to adjacent vital anatomical structures (i.e., cranial nerves) and late diagnosis, ACC is associated with poor prognosis, intracranial extent, and positive surgical margins.5 The mainstay of treatment of ACC is surgery; adjuvant radiation therapy is reserved in case of positive margins or advanced stage.6,7,8

Due to its rarity, there is some controversy over the clinical and histological factors that affect the survival of patients with ACC of the paranasal sinuses and skull base. Perineural invasion, efficacy of adjuvant treatment, and the site of origin were found to be significant prognostic factors by some authors, whereas others found that they had no impact on survival.6,9,10,11 Since most of the reports on ACC of the paranasal sinuses are based on small cohorts and on studies that also included tumors from other anatomical locations, information on predictors of outcomes in this specific population is sparse.

We performed a meta-analysis of the published pathologic and clinical data on ACC of the paranasal sinus and anterior skull base. Our aims were (1) to assess clinical and histological characteristics of this population, (2) to characterize the outcome of these patients, and (3) to identify independent predictors of outcome. Recognition of the biologic behavior of this tumor and the clinical predictors of survival may have implications for the treatment and prognosis of patients and may play a role in planning the extent of surgery and the surgical approach. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first meta-analysis of patients with ACC of the skull base and paranasal sinuses.

Materials and Methods

Meta-Analysis Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

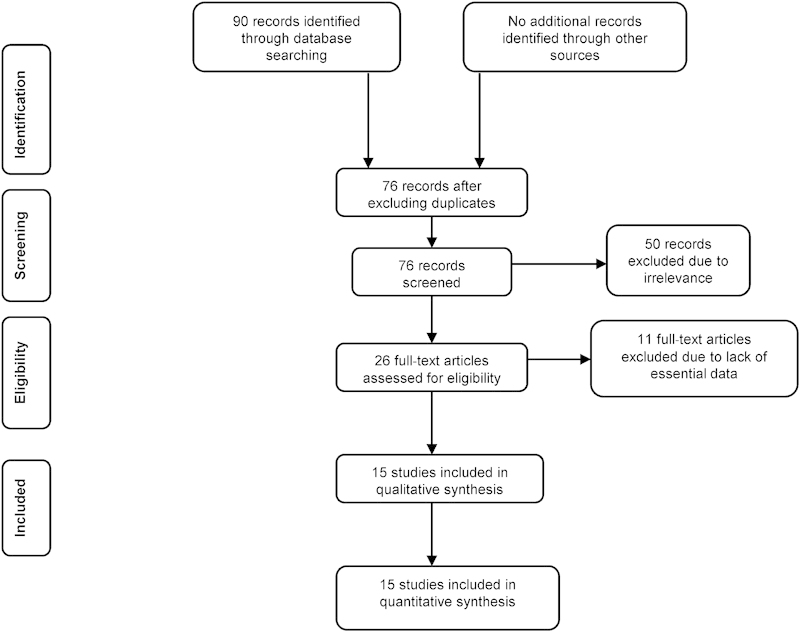

During October 2012, we conducted a systematic electronic literature database search of PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, and Google from 1975 to 2012. The searches were conducted using the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms (adenoid cystic) AND (carcinoma OR cancer) AND (skull base OR paranasal sinuses OR sinonasal) and limited to human. Reference lists of retrieved manuscripts were hand-searched for additional publications. Publications in a language other than English that could not be translated because of resource constraints were excluded. Two reviewers (M.A. and Z.G.) independently screened all available titles, as well as abstracts that were identified by the electronic search strategies. Articles were rejected at the initial screening if their titles or abstracts showed that they were clearly irrelevant. The full text of potentially relevant articles was reviewed to assess their suitability for inclusion in this meta-analysis. The study selection process is described in Fig. 1. According to the study design, the inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohorts, case-control study designs, case reports, and case series. Criteria for study population inclusion were histopathologic diagnosis of ACC involving the paranasal sinuses or the orbit, > 6 months follow-up or earlier death, and available outcome data, including survival or recurrence. The included studies are listed in Table 1. Two independent reviewers assessed both their quality and risk of bias of the included publications. They were not blinded to publication details, but measures were taken to obscure outcome assessment by using an identical abstraction form to record the collected data, thereby avoiding the description of incomplete outcome data, and to assess the risk of selective outcome reporting. The two authors independently checked each case, and all available specific data and end points were recorded for each cohort in the selected studies. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.

Table 1. Studies Included in the Meta-analysis.

| Author | Number of patients | Stage (T1-2/T3-4) |

Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Surgery followed by RT/ChRT | Primary RT/ChRT | |||

| Lin et al. 201220 | 25 | 6/19 | 21 | 0 | 4 |

| Strick et al. 200424 | 7 | 0/7 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Bhattacharyya 200318 | 64 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| da Cruz Perez et al. 200621 | 18 | 2/16 | 3 | 8 | 7 |

| Douglas et al. 200022 | 30 | n/a | 0 | 32 | 0 |

| Pitman et al. 19998 | 35 | 0/35 | 0 | 35 | 0 |

| Qureshi et al. 200625 | 8 | 2/6 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Resto et al. 200826 | 20 | n/a | 0 | 11 | 9 |

| Vedrine et al. 200915 | 4 | 0/4 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Lupinetti et al. 20076 | 105 | 26/79 | 11 | 60 | 34 |

| Schramm et al. 200127 | 11 | 0/11 | 2 | 9 | 0 |

| Rhee et al. 200619 | 35 | 10/25 | 3 | 24 | 8 |

| Doerr et al. 200328 | 14 | n/a | 3 | 10 | 1 |

| Pommier et al. 20067 | 23 | n/a | 0 | 12 | 11 |

| Kim et al. 199911 | 22 | 4/18 | 3 | 10 | 9 |

| Amit et al. | 99 | 31/68 | 28 | 71 | 0 |

| Total | 520 | 81/288 | 74 | 282 | 84 |

Abbreviations: ChRT, chemoradiation therapy; n/a, not available; RT, radiotherapy.

Patients

The International Study Group of the ACC cohort included 99 patients treated for ACC of the paranasal sinuses between 1985 and 2011 in nine cancer centers worldwide. The study was approved by the local institutional review board committees of the participating centers. The patients ranged in age from 20 to 91 years (median 55 years) and included 44 males (44%). Their follow-up ranged from 2 to 240 months (median 41 months). All patients underwent primary surgery, with or without adjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiation. The tumors were evaluated by a certified head and neck pathologist in each center according to current guidelines for the histopathological assessment of head and neck cancer carcinoma.12 Of the 99 patients, 60 (60%) died during follow-up, and 18 (18%) had distant metastases.

Statistical Analysis

Five-year OS, disease-specific survival (DSS), and disease-free survival (DFS) rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the difference in survival rate was assessed by the log rank test. OS was measured from the date of surgery to the date of death or last follow-up. The DSS for patients who died from causes other than ACC was established as the time of death. The variables that had prognostic potential were subjected to multivariate analyses with the Cox proportional hazards regression model. All analyses were performed on JMP 9 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) and confirmed by an independent statistician on an IBM SPSS Statistics package (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). All p values were two-sided, and a p value of less than 0.05 was adopted as the threshold for significance. Variables used to stratify survival included age, gender, primary tumor site, tumor margin status, invasive features (i.e., invasion to adjacent structures or nerves) and treatment group (surgery alone versus surgery and radiation versus surgery and chemoradiation). The sixth edition of the tumor-node-metastasis staging system was used for tumor, nodal, and metastasis (TNM) staging.13 The meta-analysis was performed in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.14

Results

Twenty-six relevant articles were reviewed, of which eight were excluded due to insufficient data or for not meeting the inclusion criteria (e.g., lack of essential data). Two publications that analyzed the same study population were excluded.3,15 One paper on ACC of the paranasal sinuses that focused on presenting an experimental treatment protocol (intra-arterial chemotherapy) was also excluded.16

The final study group consisted of 520 patients: 99 were enrolled in the international cohort and 421 were extracted from 15 published studies.6,7,8,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 The median age of the patients was 50 years (range, 38 to 55 years). The median follow-up period was 60 months (range, 32 to 100 months). The reason for a lower denominator being less than 520 is because details on an individual patient's demographics were not always available. Advanced stage (III-IV) disease at presentation was found in 288/369 (78%) patients. Perineural invasion was present in 214/392 (54.5%) patients, and positive tumor margins in 151/253 (59.6%). The maxillary sinus was the most commonly involved site (286/520, 54.7%), followed by the nasal cavity (57/520, 10.9%), nasopharynx (29/520, 5.5%), ethmoid sinus (22/520, 4.2%), and sphenoid sinus (16/520, 3%). The tumor epicenter was not specified in 110/520 (21%) cases.

To further characterize patterns of local and regional spread in patients with ACC of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity, we repeated the analysis in the 99 patients that were recruited from nine tertiary cancer centers that were enrolled in the ACC International Study Group. The database included detailed characteristics of the clinical, demographic, and pathological parameters of the patients, including 16 variables per patient. Table 2 lists their clinical and pathological characteristics. Forty-one patients in this group (41%) underwent neck dissection and 13/99 (13%) had nodal metastases. In 26 patients, the radiological and clinical assessment suggested the existence of neck nodes metastases. Of these, 12 patients (46%) had pathological evidence of neck metastases. The accuracy of the clinical nodal staging procedure was 63%, similar to other studies on head and neck cancer.29

Table 2. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in the International Cohort.

| Variable | No. of patients | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, y | 55 (20-91) | 99 | 100 |

| Gender | Male Female |

44 55 |

44 55 |

| Treatment | Surgery Surgery + RT/ChRT ChRT |

28 47 24 |

28 47 24 |

| Site | Maxillary sinus Nasal cavity Sphenoid/ethmoid sinus Nasopharynx Unspecified |

63 10 4 2 20 |

63 10 4 2 20 |

| T classification | 1-2 3-4 |

31 68 |

31 68 |

| N classification | N0 N+ |

86 13 |

86 13 |

| Perineural invasion | Present Absent |

51 48 |

51 48 |

| Surgical margins | Positive Negative |

43 56 |

43 56 |

| Follow-up (months) | Median (range) | 41 (2-240) | 100 |

Abbreviations: ChRT, chemoradiation therapy; RT, radiotherapy.

Histopathological examination revealed that 81/99 patients (81%) had invasion to adjacent structures, including the orbit, dura, cavernous sinus, brain, muscles, or skin (Table 3). Perineural invasion was identified in 51/99 (51%) patients, and 43/99 (43%) had positive/close margins.

Table 3. Patterns of Invasion.

| Structure involved | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Nerve | 51 (51) |

| Bone | 28 (28) |

| Muscle | 21 (21) |

| Orbital | 3 (3) |

| Skin | 2 (2) |

| Cavernous sinus | 2 (2) |

| Brain | 1 (1) |

| Dural | 1 (1) |

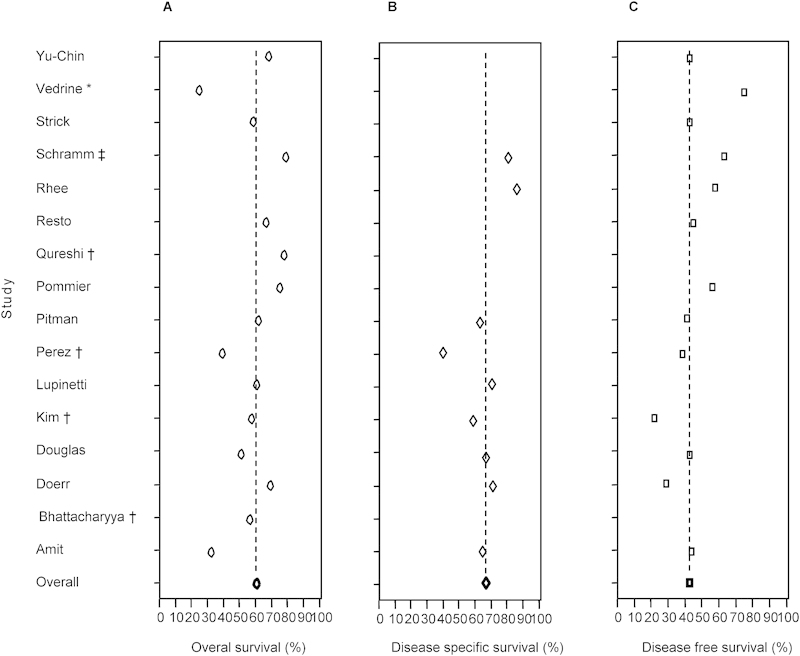

The 5-year OS and DSS of the entire 520-patient cohort were 62% (range, 25 to 81%) and 67% (range, 40 to 86%), respectively (Fig. 2). The OS and DSS of the international consortium subgroup (n = 99) was 64% and 69%, respectively. Local recurrence was found in 126/344 (36.6%) patients, whereas regional recurrence was infrequent (26/364, 7%). A total of 106 patients (29.1%) had distant metastasis, most commonly in the lung (82/106, 77%), liver (7%), and bone (6%). The 5-year DFS rate was 43% for the entire cohort and 53% for the international consortium (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Survival rates in the included studies. (A) 5-year overall survival. (B) 5-year disease-specific survival. (C) 5-year disease-free survival. The dashed line indicates the mean survival rate for the whole group. *Only the sphenoid sinus is involved. †Only the maxillary sinus is involved. ‡Only the nasopharynx is involved.

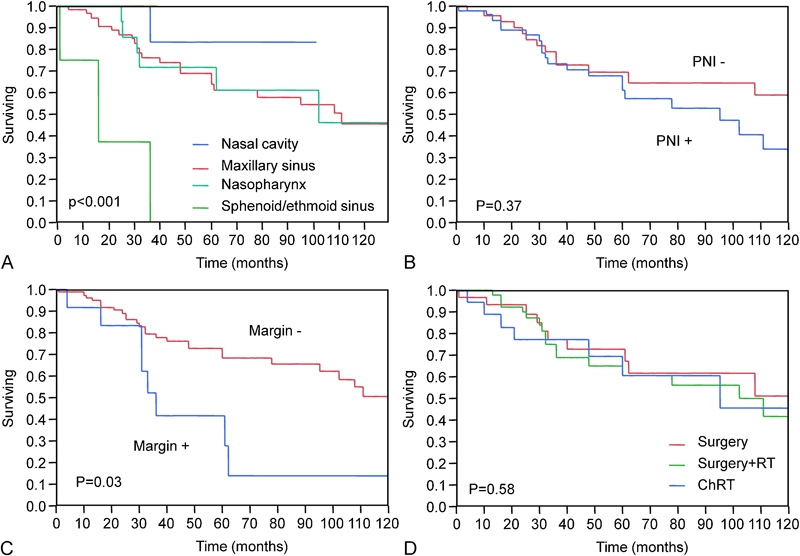

We next sought to identify predictors of outcome. As shown in Fig. 3A, our meta-analysis revealed a significant correlation between the origin of the tumor and the patient's OS and DSS (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). The DSS rates for the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus ACC were 83% and 64%, respectively, whereas ethmoid or sphenoid sinus involvement resulted in a DSS of 25%, (p < 0.001, hazard ratio [HR] = 7.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.7 to 23.5). The Kaplan-Meier analysis (Fig. 3B) also revealed that perineural invasion was not associated with OS or DSS (p = 0.3 and p = 0.37, respectively). Patients with perineural invasion had a lower DFS rate than those without perineural invasion (35% versus 51%, respectively), but the difference did not reach a level of significance (p = 0.08). In contrast, with an HR of 3.1 (95% CI 1.3 to 6.5), positive/close tumor margins were significantly more associated with a poor OS compared with negative tumor margins (69% versus 27%, respectively, p = 0.04, Fig. 3C). The results were similar for DSS (71% versus 30% for positive and negative tumor margins, respectively; p = 0.03). Local invasion was present in 160/520 (31%) patients, most commonly in the skull base (83/160, 51.8%) followed by bone (43/160, 26%), orbit (21/159, 13.7%), vasculature (8/160, 5%), and muscle (4/160, 2.5%). Our analysis revealed no association between outcome and skull base invasion (p = 0.7 for OS and p = 0.32 for DSS).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier 5-year disease-specific survival analysis. (A) Site of tumor. (B) Perineural invasion status. (C) Tmor margin status. (D) Treatment group. *Only the sphenoid sinus is involved. †Only the maxillary sinus is involved. ‡Only the nasopharynx is involved. ¶Data are not provided.

To determine whether there is any advantage for adjuvant therapy on outcome in this population, a Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed in three treatment groups (n = 440): surgery alone (74/440, 17%), surgery followed by radiotherapy, or chemoradiation (282/440, 64%) and primary chemoradiation therapy (84/440, 19%). The results demonstrated that there was no difference in 5-year OS between the three groups (p = 0.58, Fig. 3D).

Since multivariate analysis is not possible in a meta-analysis, we used the expanded data from the international consortium to validate the independent predictors of outcome in patients with ACC of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. The results of the multivariate analysis are displayed in Table 4. Independent predictors of outcome were age and tumor site for OS and DSS; tumor margin status was marginally significant (p = 0.059 and p = 0.063, respectively), probably due to the low number of patients.

Table 4. Multivariate Analysis of Outcome.

| Variable | Overall survival (p value) |

Disease-specific survival (p value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | <70 >70 |

0.03 | 0.02 |

| T classification | 1/2 3/4 |

0.78 | 0.56 |

| N classification | 1-4 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Treatment | Surgery Surgery + RT ChRT |

0.99 | 0.84 |

| Margins status | Positive Negative |

0.05 | 0.06 |

| Perineural invasion | Yes No |

0.13 | 0.24 |

| Intraorbital invasion | Yes No |

0.37 | 0.66 |

| Dural invasion | Yes No |

0.74 | 0.42 |

| Cavernous sinus invasion | Yes No |

0.67 | 0.78 |

| Bone invasion | Yes No |

0.36 | 0.65 |

| Tumor site | Maxillary Nasal cavity Ethmoid/sphenoid |

0.007 | 0.009 |

Abbreviations: ChRT, chemoradiation therapy; RT, radiotherapy.

Discussion

Previous studies on the prognostic factors that influence survival of patients with ACC of the paranasal sinuses and skull base have yielded contradictory results. For example, the impact of local invasion was evaluated in three studies and only one of them identified skull base infiltration as being a significant factor.6,7,8 Adjuvant treatment had a significant impact on survival in several studies,6,23 whereas others found an effect of adjuvant radiotherapy only in patients with negative surgical margins.20 These discrepancies can be attributable to differences in the locations of tumors, the size of the cohort, the tumor stage, and the type of statistical analysis.

In our current work, we aimed to re-evaluate the significance of the above-cited variables in a more uniform population of patients—specifically, those with tumors isolated to the paranasal sinuses, as opposed to ACC tumors in a variety of locations. To improve the statistical strength of our study, we conducted a meta-analysis of previously published cohorts and a separate analysis of data retrieved from multiple tertiary cancer centers. Our analysis revealed that tumor margin status and tumor site were significant predictors of outcome. Both positive/close tumor margins and tumors of sphenoid/ethmoid origin were associated with dismal prognosis compared with negative tumor margins and tumors of maxillary/nasal cavity origin. Our data also indicate that positive lymph nodes are associated with decreased OS (p = 0.05)

We also evaluated the importance of perineural invasion, whose significance in ACC is controversial, with most of the previous studies having found no impact on survival.3,30,31 An early study from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center evaluated 160 patients with malignant minor salivary gland tumors and 40 with tumors originating in the paranasal sinuses.32 Those authors found that perineural invasion in general, as well as perineural invasion in an identified nerve, were not associated with survival, and other studies showed that perineural invasion was associated with an increased treatment failure rate, but that it had no impact on outcome.33 In contrast, a recent study by Mendenhall et al5 analyzed the importance of clinical evidence of perineural invasion on patients with ACC of all possible anatomical sites and found that it had a significant impact on survival. The collective results of our current meta-analysis, which represents the largest study performed to date on paranasal ACC, revealed that perineural invasion had no significant impact on survival. We speculate that, similar to cases of squamous cell carcinoma, it is possible that proximity of paranasal tumors to the skull base and other vital structures limits the impact of perineural invasion on survival.

An important finding of our study was that adjuvant treatment in the form of radiotherapy or chemoradiation was not associated with better outcome than surgery alone or primary chemoradiation. It is reasonable to consider that some of the patients who were treated by primary chemoradiation were poor surgical candidates or had inoperable tumors. As such, the finding that surgery did not improve the survival rate (with or without radiotherapy) raises questions about the role of surgery in this population. Though on the one hand several studies on ACC of the head and neck showed that adjuvant radiotherapy generally leads to enhanced local control after surgery,5 a similar study from the Cleveland Clinic reported local control benefit of postoperative radiation therapy limited only to advanced tumors with/without positive margins.34 It is reasonable to consider that some of the patients who were treated by primary chemoradiation were poor surgical candidates or had inoperable tumors. Furthermore, the small number of patients treated by primary chemoradiation with curative intent (n = 84), limits any meaningful analysis.

We realize that one of the limitations of this study is the lack of data regarding the histological classification of ACC (i.e., solid, cribriform, or tubular subtype). Although several authors showed that tumor grade does not have prognostic value, others have demonstrated correlation between high-grade solid tumors and poor prognosis. 6,20,24,35

Conclusions

The results of this meta-analysis revealed that margin status and tumor site were significant predictors of outcome in patients with paranasal and skull base ACC. In addition, tumors of the sphenoid and ethmoidal sinuses were associated with dismal prognosis, whereas perineural invasion was not associated with prognosis. Our findings showed no added benefit of adjuvant treatment and warrant prospective studies to verify the role of surgery and adjuvant treatment in the survival of patients with paranasal ACC.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation, the Israel Cancer Association (grant donated by Ellen and Emanuel Kronitz in memory of Dr. Leon Kronitz No. 20090068), the Israeli Ministry of Health (No. 3-7355), the Weizmann Institute - TASMC Joint Grant, the ICRF Barbara S. Goodman Endowed Research Career Development Award (2011-601-BGPC), and a grant from the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation. Esther Eshkol is thanked for her editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Ellington C L, Goodman M, Kono S A. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: Incidence and survival trends based on 1973-2007 surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4444–4451. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhayani M K, Yener M, El-Naggar A. et al. Prognosis and risk factors for early-stage adenoid cystic carcinoma of the major salivary glands. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2872–2878. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gil Z, Carlson D L, Gupta A. et al. Patterns and incidence of neural invasion in patients with cancers of the paranasal sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(2):173–179. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2008.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel S G, Singh B, Polluri A. et al. Craniofacial surgery for malignant skull base tumors: report of an international collaborative study. Cancer. 2003;98(6):1179–1187. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendenhall W M, Morris C G, Amdur R J, Werning J W, Hinerman R W, Villaret D B. Radiotherapy alone or combined with surgery for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2004;26(2):154–162. doi: 10.1002/hed.10380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupinetti A D, Roberts D B, Williams M D. et al. Sinonasal adenoid cystic carcinoma: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2007;110(12):2726–2731. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pommier P, Liebsch N J, Deschler D G. et al. Proton beam radiation therapy for skull base adenoid cystic carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(11):1242–1249. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.11.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitman K T, Prokopakis E P, Aydogan B. et al. The role of skull base surgery for the treatment of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sinonasal tract. Head Neck. 1999;21(5):402–407. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199908)21:5<402::aid-hed4>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett A W, Speight P M. Perineural invasion in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands: a valid prognostic indicator? Oral Oncol. 2009;45(11):936–940. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurie S A, Ho A L, Fury M G, Sherman E, Pfister D G. Systemic therapy in the management of metastatic or locally recurrent adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):815–824. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70245-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim K H, Sung M W, Chung P S, Rhee C S, Park C I, Kim W H. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120(7):721–726. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880310027006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidlines for the examination and reporting of head and neck cancer specimens. LEEDS: Yorkshire Cancer Network. 2007;7:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel S G Shah J P TNM staging of cancers of the head and neck: striving for uniformity among diversity CA Cancer J Clin 2005554242–258., quiz 261-262, 264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D G. PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglas J G, Laramore G E, Austin-Seymour M. et al. Neutron radiotherapy for adenoid cystic carcinoma of minor salivary glands. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tse D T, Benedetto P, Dubovy S, Schiffman J C, Feuer W J. Clinical analysis of the effect of intraarterial cytoreductive chemotherapy in the treatment of lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(1):44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vedrine P O, Thariat J, Merrot O. et al. Primary cancer of the sphenoid sinus—a GETTEC study. Head Neck. 2009;31(3):388–397. doi: 10.1002/hed.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya N. Factors affecting survival in maxillary sinus cancer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(9):1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhee C S, Won T B, Lee C H. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sinonasal tract: treatment results. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(6):982–986. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000216900.03188.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y C, Chen K C, Lin C H, Kuo K T, Ko J Y, Hong R L. Clinicopathological features of salivary and non-salivary adenoid cystic carcinomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(3):354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Cruz Perez D E, Pires F R, Lopes M A, de Almeida O P, Kowalski L P. Adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the maxillary sinus: report of a 44-year experience of 25 cases from a single institution. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(11):1592–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.11.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douglas J G, Laramore G E, Austin-Seymour M, Koh W, Stelzer K, Griffin T W. Treatment of locally advanced adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck with neutron radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46(3):551–557. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim G E, Park H C, Keum K C. et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the maxillary antrum. Am J Otolaryngol. 1999;20(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(99)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strick M J, Kelly C, Soames J V, McLean N R. Malignant tumours of the minor salivary glands—a 20. year review. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57(7):624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qureshi S S, Chaukar D A, Talole S D, Dcruz A K. Clinical characteristics and outcome of non-squamous cell malignancies of the maxillary sinus. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93(5):362–367. doi: 10.1002/jso.20500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resto V A, Chan A W, Deschler D G, Lin D T. Extent of surgery in the management of locally advanced sinonasal malignancies. Head Neck. 2008;30(2):222–229. doi: 10.1002/hed.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schramm V L Jr, Imola M J. Management of nasopharyngeal salivary gland malignancy. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(9):1533–1544. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doerr T D, Marentette L J, Flint A, Elner V. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expression in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skull base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(2):215–218. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch W M, Ridge J A, Forastiere A, Manola J. Comparison of clinical and pathological staging in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: results from Intergroup Study ECOG 4393/RTOG 9614. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(9):851–858. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perzin K H, Gullane P, Clairmont A C. Adenoid cystic carcinomas arising in salivary glands: a correlation of histologic features and clinical course. Cancer. 1978;42(1):265–282. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197807)42:1<265::aid-cncr2820420141>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eby L S, Johnson D S, Baker H W. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1972;29(5):1160–1168. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197205)29:5<1160::aid-cncr2820290506>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garden A S, Weber R S, Ang K K, Morrison W H, Matre J, Peters L J. Postoperative radiation therapy for malignant tumors of minor salivary glands. Outcome and patterns of failure. Cancer. 1994;73(10):2563–2569. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940515)73:10<2563::aid-cncr2820731018>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fordice J, Kershaw C, El-Naggar A, Goepfert H. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(2):149–152. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman D A, Carlson T P, Khuntia D, Bergstrom R T, Saxton J, Esclamado R M. Role for postoperative radiation therapy in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(7):1194–1199. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiro R H, Huvos A G. Stage means more than grade in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1992;164(6):623–628. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]