Abstract

Crohn disease involves the perineum and rectum in approximately one-third of patients. Symptoms can range from mild, including skin tags and hemorrhoids, to unremitting and severe, requiring a proctectomy in a small, but significant, portion. Fistula-in-ano and perineal sepsis are the most frequent manifestation seen on presentation. Careful diagnosis, including magnetic resonance imaging or endorectal ultrasound with examination under anesthesia and aggressive medical management, usually with a tumor necrosis factor-alpha, is critical to success. Several options for definitive surgical repair are discussed, including fistulotomy, fibrin glue, anal fistula plug, endorectal advancement flap, and ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract procedure. All suffer from decreased efficacy in patients with Crohn disease. In the presence of active proctitis or perineal disease, no surgical therapy other than drainage of abscesses and loose seton placement is recommended, as iatrogenic injury and poor wound healing are common in that scenario.

Keywords: anorectal, Crohn disease, fistula, abscess, flap, plug, ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT), immunomodulators, fistulotomy

Objectives: Upon completion of this article, the reader should be able to (1) understand the presentation and methods of diagnosis and management of Crohn-associated anorectal infections, (2) understand the various options for surgical management of Crohn-associated anorectal fistulas, (3) understand the issues and option regarding adjuvant medical management of anorectal Crohn disease, and (4) understand the various options for management of refractory anorectal Crohn disease.

In the first widely read description of “terminal ileitis” in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Burrill Crohn and his associates did not describe any perianal manifestations.1 However, the syndrome has been recognized for centuries,2 including descriptions of fistulizing rectal and perianal disease in Irish children by Colles in 1830.3 Bissell described a cohort of children with perianal Crohn disease (CD) in the American literature in 1938,4 and Penner and Crohn amended the original description of CD with a case series of three patients with perianal disease, and estimated CD would present with fistula-in-ano some 14% of the time.5

How many patients with CD actually have perianal manifestations is not as clear, however, with reports ranging from 14 to 38% in the literature.6,7,8 This wide range is likely due to variation in the way perianal disease is defined, as only a subset of patients will develop disease requiring operative intervention, and many develop benign problems, such as skin tags and hemorrhoids that are not necessarily reported.9 However, only a small minority present with isolated disease of the anus,10 and the likelihood increases the more distal the luminal disease. In patients with ileocolonic CD, only 15% will develop fistulas, but fistulas occur in 92% of patients with colonic CD and rectal involvement.8 In addition, the longer a patient has CD, the more likely they are to have perianal manifestations—fewer than 10% of patients with proximal disease develop perianal fistulas in the first 5 years of the disease, but more than 25% will over the course of 20 years.11,12

Patients who have perianal disease are worse off than those who do not. Perianal disease is associated with a more disabling natural history,13 increased extraintestinal manifestations,14 and more steroid resistance.15 Most patients will require surgery of some kind, and although this will usually be minor procedures, such as incision and drainage of perirectal abscesses, as many as 21% will require proctectomy for refractory and recurrent disease.6,8

Perirectal Abscess

Fistula-in-ano and associated abscess and perineal sepsis are the most common presentations of perianal CD, and are by far the most common reasons for operative intervention. One study of 202 consecutive patients with CD in the United Kingdom found that 54% of patients presented with perianal findings overall, and 55% of those patients had an abscess or fistula.16

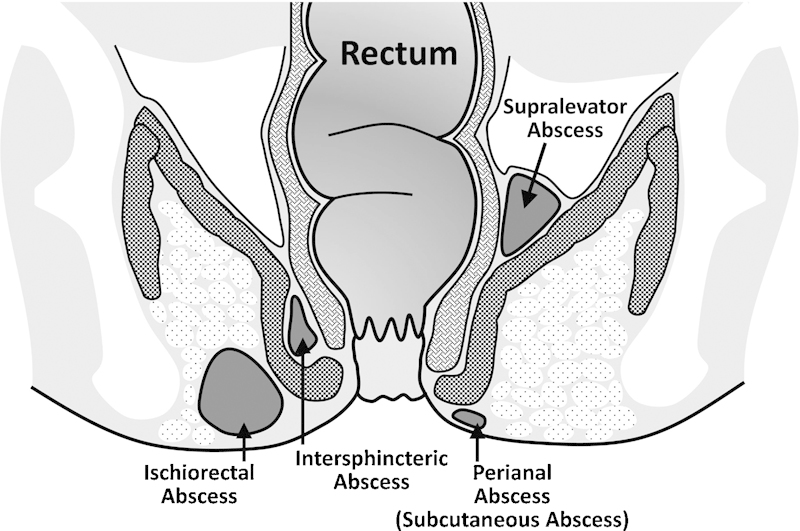

Abscess presents with rectal pain at rest or with defecation, fever, swelling, and fluctuance on digital rectal examination. In patients with CD, similar to patients without the disease, these abscesses can present in any of the potential perirectal spaces (Fig. 1). However, patients with CD are more likely to have more complex abscesses (in the ischiorectal or supralevator space). Diagnosis is usually possible with a complete history and digital rectal examination, but can be challenging. In a prospective study of 66 patients with perianal abscess, digital exam was able to clearly delineate only 57% of cases, and was not useful in diagnosing any of the abscesses in the supralevator space. The addition of endorectal ultrasound (EUS) in this instance was able to diagnose 100% of the abscesses, and was a useful guide to therapy.17,18 Similar results have been found with transperineal ultrasound.19 Computed tomography (CT) scanning is a common and easily available modality, and frequently effective in diagnosing abscesses that may not be palpable. It should be used with caution, however; a recent study of 113 patients with abscess found that CT missed 23% of cases, and was especially ineffective in immunocompromised patients.20

Fig. 1.

Sites of anorectal abscess.

Once an abscess is diagnosed, surgery is required. Incision through the rectal mucosa and drainage into the rectum is ideal when possible, but care must be taken to avoid injury to the anal sphincter complex.21,22 Alternatively, for deeper infections, a mushroom drain can be placed into deeper spaces through a small incision in the skin to avoid a prohibitively large wound, although this is more likely to lead to an eventual persistent tract. Additionally, abscesses associated with CD may be associated with high-blind tracts, without complete fistula.

After drainage is performed, antibiotics can be initiated, although they are neither effective monotherapy nor a necessary adjunct following good surgical drainage. Most practitioners do not send cultures of the abscess fluid, as these are almost always polymicrobial and respond well to drainage alone, but cultures are warranted if there is extensive surrounding cellulitis and the patient requires a course of antibiotic therapy. Immunosuppressants and immunomodulator therapy should be discontinued once an abscess is diagnosed. Deciding when to restart this therapy can be challenging, as a majority of abscesses progress to fistulas and will require continued surgical treatment. A multidisciplinary approach, including the practioners who prescribe the patient's medical regimen, should be utilized.

Fistula-in-Ano

The majority of perirectal abscesses in patients with CD will eventually develop into fistulas. In addition, 29% of patients with CD presenting with perineal disease will have fistula-in-ano without frank abscess.16

Fistulas can be characterized using several different schema. However, a straightforward and clinically relevant system categorizes all fistulas as either simple or complex. Simple fistulas are defined as superficial, low intersphincteric, or transsphincteric fistula, with a single opening and no associated abscess. Complex fistulas are defined as any fistula with an internal opening above the dentate line, fistulas that traverse a significant portion of the sphincter complex, as well as branched fistula at any level with multiple openings.7 Rectovaginal fistulas are considered complex, regardless of the location of the internal opening. Some investigators consider all fistulas in patients with CD as complex, regardless of anatomic location.

The diagnosis of a fistula-in-ano, like the diagnosis of perirectal abscess, can usually be made with a thorough physical exam. Goodsall's rule, which predicts the tract of a fistula and the associated opening into the rectum based upon the relationship of the external opening to the transverse anal line, and the distance from the anal verge, is often not effective in patients with CD. A good exam under anesthesia (EUA) is required, in addition to either an EUS, or preferably, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The addition of either one of these modalities to an EUA increases diagnostic accuracy by 10%.23 The addition of a pelvic MRI cannot only assist in making the diagnosis,24,25 but can substantially alter the operative plan by revealing additional or more complex disease in as many as 40% of patients with CD.26,27

Medical Therapy

Medical therapy is a critical adjunct in the treatment of fistula-in-ano and CD, and should be initiated once the diagnosis of active perianal CD is made.

Antibiotics have been shown to be effective as a bridge to immunosuppressive therapy,28 with 70 to 95% experiencing a positive clinical response within 6 to 8 weeks,29,30 and worsening of symptoms when they are discontinued or decreased.31 Fewer than 50% of patients, however, experience healing of the fistula on antibiotic therapy alone, and the majority of cases will recur if antibiotics are withdrawn.32

More definitive medical therapy usually requires immunosuppression. A meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials examined the efficacy of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and azathioprine and showed that in these 70 patients, 54% of treated patients experienced fistula healing versus only 21% of controls.33 Other agents, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus have been used, but less frequently. Cyclosporine has an excellent, rapid effect in up to 83% of patients when given intravenously,34,35 but does not work as well when taken orally.36 In a randomized controlled trial, tacrolimus resulted in improvement of CD symptoms in 43% of patients versus 8% in the placebo arm.37 Neither of these agents were studied looking specifically at perianal fistulizing disease, however.

Tumor necrosis factor antagonists have proven to be extremely effective in achieving durable remission of CD, including perianal fistulizing disease. All three major TNF antagonists antibodies are effective, but head-to-head comparisons have not yet been performed.

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, and was evaluated in the ACCENT 1 and 2 trials. ACCENT 1 enrolled 92 patients, and showed efficacy using infliximab as induction therapy for fistulizing CD: 68% of patients treated with infliximab had at least a 50% improvement in symptoms versus 26% with placebo.38 The ACCENT 2 trial documented longer time to recurrence of fistulas with infliximab maintenance therapy (40 vs. 14 weeks for placebo).39 In addition, treatment with infliximab resulted in less need for surgery and fewer hospitalizations.39 Interestingly, rectovaginal fistulas have a poorer response to infliximab therapy—only 14 to 30% of these heal versus 46 to 78% of other perianal fistulas.38,40,41 Infliximab is associated with a significant number of nonresponders and gradual resistance, resulting in a decreasing efficacy in ∼50% of patients over time.42

Another agent, adalimumab, has a similar safety profile to infliximab,43 and is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against TNF-α. In a post hoc analysis of the CHARM trial, in 854 patients, complete fistula closure at 1 year was seen in 39% of patients treated, versus 13% in the placebo arm. These results were shown to be durable at 2 years.44 In addition, adalimumab is effective in patients who are infliximab nonresponders or have become infliximab-refractory. In the CHOICE trial, 673 patients, achieved complete fistula healing after 8 weeks of adalimumab therapy; in 39% of these patients, significant improvements in quality of life (QOL) measures were seen.45

Certolizumab pegol is also an anti-TNF-α antibody, but has had the Fc portion of the molecule removed, retaining only the Fab' moiety. This processing increases solubility and decreases immunogenicity.46 In a series of trials (PRECiSE 1-4), certolizumab pegol has been shown to be effective induction therapy, effective maintenance therapy, resulting in durable remission for at least 4 years, and effective in causing healing of perianal fistula in 36% of patients undergoing therapy for at least 26 weeks.47,48,49

Finally, combining infliximab with azathioprine has resulted in the highest rate of treatment success at 6 months, measured by corticosteroid-free clinical remission rates, at 56.8%.50 Fistulizing disease has not been specifically examined for this similar additive effect, but mucosal healing was a secondary endpoint in this trial, and also demonstrated additional efficacy with the combination therapy. Testing of combined therapy with other TNF antagonist agents is ongoing.51

In summary, the medical approach to the treatment of CD is undergoing a sea of change. In the past, therapy has been increased in a stepwise fashion to achieve remission, adding increasingly potent immunosuppressant medications. However, with the addition of anti-TNF-α agents, patients are increasingly starting on monotherapy with an anti-TNF agent or combined therapy with immunosuppression and a TNF-α antagonist, allowing for faster, and more durable remission of disease.

Surgical Therapy

There are several surgical options available for the repair of a fistula in a patient with CD. Simple fistulas, especially in the absence of active proctitis, are amenable to straightforward surgical therapy via fistulotomy. Complex fistulas, on the other hand, must be treated more cautiously, as operative intervention or muscle division with a cutting seton has resulted in a high rate of incontinence in patients with CD.52,53 Up to 60% of patients with complex fistulas who undergo fistulotomy will have poor wound healing and persistent complications.54,55 In the presence of active inflammation, a seton can be safely placed to prevent abscess formation, but definitive surgical therapy should be avoided.56

Seton

A loose or noncutting seton made of inert material, passed through the fistula tract and secured as a loop, allows the tract to remain open and drain, and facilitates healing or improvement in the fistula tract in up to 79 to 100% of patients, when combined with medical therapy.57,58,59,60,61,62

Ideally, a loose seton will act as a bridge to more definitive surgical therapy, but in some patients with refractory disease, setons will need to remain in long term. Patients report a good QOL with setons in place, even for months at a time, but removal of the seton does result in recurrence of disease in the majority of patients—up to 80%.60,63,64

Fistulotomy

Several series have examined the effect of fistulotomy in patients with CD with simple superficial perianal fistula (with no muscle involvement), and most report healing rates between 80 and 100%.7 When the investigators specifically noted the absence of rectal inflammation, results were even better, with healing in 22 of 24 (95%) of patients, and recurrence in only 4 of 24 (15%).22,65,66 In contrast, a study that specifically noted active proctocolitis at the time of surgery documented a healing rate of only 27%.54

Many surgeons would not advocate dividing a significant amount of muscle during the performance of the fistulotomy, as this can impact continence in as many as 54% of patients, double the rate of those treated with loose setons and more conservative therapy.67 The same investigators, however, note good results with fistulotomy for simple intersphincteric and transsphincteric fistulas, even when a portion of the muscle is divided.57,66,67

The addition of biologic immunomodulators perioperatively appears to be effective, increasing the rate of clinical improvement in a recent review from 36 to 71%.68

Fibrin Glue

Fibrin glue consists of two parallel syringes of fibrinogen and thrombin. Injected together to fill a fistula tract via a catheter, the resultant clot fills the cavity and seals the fistula. Early reports from one group, using either autologous blood admixed with a fibrin adhesive, or a commercial fibrin adhesive, on patients with cryptoglandular fistula, yielded excellent results, with 68 to 85% healing at 1 year.69,70,71 These results have been difficult to replicate, however, with other investigators reporting success rates of 50% or less.72,73,74 Notably, although better results may be obtainable with different therapy for simple fistulas, even the 50 to 70% healing is an improvement in patients with complex fistulas.75,76

One dedicated randomized controlled trial77 of fibrin glue has been performed in 77 patients with CD. All patients had quiescent disease, illustrated by a mean Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) of only 96, making them favorable hosts. Half had a complex fistula. The control group had all setons removed at the start of the trial, and underwent observation. Clinical remission was assessed at 8 weeks. In the patients treated with glue, only 38% experienced remission, but this was more than double the 16% remission rate in patients given no therapy. There were no adverse events. These results echo smaller series previously, which showed healing after fibrin glue in only 31% of patients with CD.78

Clearly, fibrin glue has some role in assisting fistula closure. It seems to be less effective in patients with CD, but is extremely well tolerated and has a minimal risk profile, and could be used as an attempt to avoid further surgery or as an alternative to long-term seton placement.

Fistula Plug

The Surgisis (COOK Biotech, West Lafayette, IN) fistula plug is a portion of lyophilized porcine intestinal submucosa. It is inert, eliciting no foreign body or inflammatory reaction when implanted, and acts as a collagen scaffold, which is populated by a patient's endogenous cells over the course of 3 months.79,80

More than 50 articles have been published on the use of the fistula plug, with highly variable results. Two recent systematic reviews have looked at outcomes in these series.81,82 Garg et al81 in 2009 examined the literature to that date, inclusive of 317 patients. Patients with rectovaginal fistula were excluded. They considered the data too heterogeneous to allow weighted comparisons, and so reported a range of healing of 24 to 95%, at follow-up of 3.5 to 12 months. In patients with complex fistulas, the rate was 35 to 87%, and in the 44 patients included with CD, the rate was 29 to 86%.

O'Riordan et al82 performed a systematic review in 2012, including and adding to the studies summarized by Garg et al, looked specifically to compare those patients with cryptoglandular abscess to those with CD. Their results were similar: in 530 patients with 42 patients with CD, healing rates were 54.8% in patients without CD, and 54.3% in those with CD at follow-up between 3 and 24 months. Significantly, both studies noted high rates of failure secondary to extrusion of the plug (4-41% in Garg et al).81 O'Riordan et al specifically noted no changes in continence in the 196 patients in which this was studied.82

Several small series have used the fistula plug in rectovaginal and pouch-vaginal fistulas in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Healing rates, using a specialized button plug, were 58% (7 of 12 patients)83 at 4 months in one series and 88% (6 of 7 patients)84 at 6 months in another. Repeat attempts after a failure were almost always unsuccessful.

The fistula plug has been compared directly to the endorectal advancement flap in two randomized controlled trials and one cohort study,85,86,86 the results of which are discussed below. Although safe and easy to perform, the success rate of the plug is not high, and compares unfavorably with endorectal advancement flaps. Failure is almost always due to extrusion of the plug in the early postoperative period, and techniques to prevent this may result in improved healing.

Ligation of Intersphincteric Tract

First described by Rojanasakul in 2007,87 ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT procedure) is a procedure designed to close complex fistulas with complete sphincter preservation. An incision is made in the intersphincteric groove, and dissection carried down to the fistula tract. The fistula tract is ligated in the intersphincteric groove at both the internal and external sphincters. The remainder of the external tract is then curetted out, and the external opening is widened at the skin. Finally, the skin incision is closed. The approach is low cost, and in several small series from around the world, effective in healing 57 to 83% of cryptoglandular fistula, even if they have failed a previous surgical attempt.88,89,90 In patients undergoing LIFT primarily, the healing rate is up to 90%.91 Importantly, no deficit in continence has been reported.

Although the procedure holds promise, it has not undergone rigorous academic examination, nor has it been performed in a cohort of patients with CD. In an examination of failures and recurrences, most failures stemmed from a persistence of the internal fistula opening, which then resulted in drainage and failure of wound healing at the intersphincteric incision made to perform the dissection.92 This pattern of failure—poor wound healing and a persistence of fistulous disease despite intervention—is likely to be higher in patients with CD than in the general population.

Endorectal Advancement Flap

Endorectal advancement flaps have been used successfully in the treatment of complex or recurrent fistulas, including rectovaginal fistulas. In this operation, the internal opening of the fistula is identified from within the rectum, and is excised. The mucosa, submucosa, and sometimes the circular muscle is then mobilized as a vascularized pedicle, and advanced over the fistula tract. The results of numerous surgical series have been published, with healing rates of 71% reported in early series, even in cohorts of patients with CD.93 Other series have reported widely variant healing rates, however, as well as widely reported rates of incontinence postoperatively, which can be the major complication following this surgery.

Soltani and Kaiser recently published a systemic review of the literature, specifically examining patients with cryptoglandular disease separately from those with CD.94 They extracted data on 1,654 patients from 35 studies, limiting themselves to perianal fistulas. Overall, the quality of the studies was low, with only three randomized trials included. Of these patients, 91 were noted to have CD. At a mean follow-up of 29 months, healing was noted in 80.8% (range 24.1-100%) of patients with cryptoglandular disease, and 64% (range 33.3-92.9%) of patients with CD. Partial thickness flaps, rather than full-thickness flaps, enjoyed above average success. The weighted average rate of incontinence was noted to be 13.3% (range 0-35%) in patients with cryptoglandular disease, and 9.4% (0-28.6%) in patients with CD.

Two randomized controlled trials, included in the systematic analysis above, compared advancement flap to fistula plug in patients with complex cryptoglandular disease. Van Koperen et al85 found in 60 patients no statistically significant difference between therapies at 11 months, but reported recurrence rates far higher than other investigators, with only 29% healing with the fistula plug, and 48% healing with the mucosal advancement flap. The trial performed by Ortiz et al,86 in 31 patients with complex cryptoglandular fistulas, was halted due to poor performance with the fistula plug—only 20% of patients healing at 1 year. In contrast, 87.5% of patients who underwent endorectal advancement flap healed.

Finally, in patients with rectovaginal fistula, an advancement flap has been shown to be effective in retrospective series, with 54 to 71% healing.95,96 Although most advocate rectal flaps because the rectum is the high-pressure side of the fistula, one series has demonstrated 92% healing in 14 patients treated with a vaginal advancement flap.97

Diversion

Diversion can be used as either a temporary measure, or a more permanent solution in patients with unrelenting perineal disease. Usually, other surgical methods and maximal medical therapy have been attempted before creating a stoma.56 Risk factors for requiring diversion include colonic CD, anal stricture, and multiple complex perianal fistulas (i.e., “watering can perineum”). As many as 50% of these stomas are never reversed; patients need to be prepared for this possibility.98,99 Interestingly, permanent diversion can improve QOL. One study found that diverted patients complained of symptoms of their CD half as often as patients who had not been diverted.100

Diversion does help create an opportunity to effect complex perianal repairs more effectively; up to 81% of patients do have improvement of perianal disease immediately after diversion, but 55% relapse quickly, so any repair should be done promptly after diversion. Many of these patients will eventually progress to proctectomy.101

Proctectomy

If a patient fails more conservative medical and surgical therapy, or in the presence of aggressive and unrelenting rectal disease, proctectomy is appropriate, and in published series it is required in 10 to 20% of cases.7 Unfortunately, proctectomy can be complicated by poor wound healing and perineal sinus formation in up to 25 to 50% of patients.102,103 A gracillis flap104 can be helpful.

Fissure

Fissures are common in CD, and unlike idiopathic fissures in the general population, which are almost always located in the anterior or posterior midline, fissures in patients with CD can be eccentrically located in up to 20%.105,106 In fact, fissures arising in atypical locations may be a first sign heralding the diagnosis of CD. The etiology of fissures in CD is not clearly delineated, but could be due to the ischemia thought to be responsible for idiopathic fissures, or could be a more direct inflammatory and erosive process of the anoderm overlying the sphincter complex. Traditionally, it has been reported that fissures in patients with CD are painless, and pain should prompt examination for underlying abscess. However, more recent work has found that as many as 85% of fissures present with pain, even in the absence of an abscess.107

Medical management is always the first step in treatment, and outcomes are similar to that of idiopathic fissures; 80% will resolve with conservative therapy.108 The various medication options, including nitroglycerin paste, diltiazem ointment, and botulinum toxin, have not be compared in patients with CD.7 Surgical therapy is avoided for the very real risk of a nonhealing wound in addition to the fissure, and this is especially true if any sign of active anorectal disease is present.56 In a patient without active disease, however, one study found an 88% success rate with sphincterotomy. The same study also found that in patients treated with medical therapy alone, up to 26% progress to abscess or fistula.107

Stricture

Anal and low rectal stricture in patients with anorectal CD is not uncommon, occurring in 10% of patients in one series.16 Approximately half are in the rectum, and half in the anus.109 Diagnosis is usually made easily on anoscopic or proctoscopic examination, and if the stricture is not symptomatic, no therapy is needed.56

However, should patients complain of functional difficulty with defecation, therapy is warranted.109 There is no targeted medical therapy, and it is unclear if treatment with modern anti-CD regimens can result in regression or resolution of symptomatic stenosis. Surgical therapy begins with either anal or rectal dilation with a coaxial balloon, serial dilators, or a finger, and is initially very effective. Unfortunately, it is accompanied by poor wound healing in 47%.110 In refractory cases, which can be a large minority of these patients, proctectomy will be required eventually. Diversion is ineffective, as it can often exacerbate proctitis and stenosis, requiring further therapy.111

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are thought to occur in patients with CD for the same reason as the general population-straining with stool, constipation, and frequent sitting on the toilet. In patients with CD rarely suffering from constipation, it is not surprising that only 7% of patients with CD report hemorrhoids, compared with an estimated 24% of the general population.16,112 Symptoms of hemorrhoidal disease, however, can be exacerbated by the loose stools that can accompany CD flares.

Medical treatment is similar to patient without CD-sitz baths, increased dietary fiber combined with oral hydration, and topical ointments for symptomatic relief. Surgical treatment, on the other hand, should be avoided, due to high rates of nonhealing wounds, infection, and stenosis.113 However, in the absence of active anorectal CD, standard techniques have enjoyed success. Wolkomir and Luchtefeld reported an 88% success rate with simple hemorrhoidectomy in a series of 17 patients.114 The American Gastroenterological Association supports elastic banding in a 2003 consensus statement,7 and a recent series of 13 patients with CD showed a 77% success rate at 18 months, and no complications, using Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation.115

Skin Tags

Perianal skin tags can masquerade as hemorrhoids in patients with CD, and are present in up to 70% of patients. Atypical skin tags, “cocks-comb tags,” are pathognomonic for anorectal CD and often prompt the diagnosis. These irregular folds of perianal skin are thought be due to recurrent fissures and fistulas, or associated with perianal lymphedema.116 They are usually soft, asymptomatic, and nontender, as one would expect of skin tags in the general population, and diagnosis can be made on physical exam. This can be challenging, however, as often they become swollen, hard, and painful during a CD flare, tempting excision.114

Once diagnosed, they should be managed conservatively whenever possible. Medical management is expectant. Should they interfere significantly with perineal hygiene or become persistently bothersome, they can be excised. However, if excised, there is an increased risk of delayed wound healing and exacerbation of pre-existing perianal CD.16,117

Anal Cancer

Patients with CD have a known increased risk of colon cancer, similar to the risk seen in ulcerative colitis.118 In addition, patients with CD have a significantly increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the anus.119,120 Persistent active perianal disease and long duration of disease are risk factors for developing these cancers.121,122 Although the resultant tumors appear to be no more aggressive than those in non-IBD patients, they are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage.123 Therefore, Sjodahl et al have recommended that patients at high risk (including patients with extensive colitis, bypassed loops, diversion, refractory perianal disease, strictures, and primary sclerosing cholangitis) undergo surveillance annually with anoscopic examination, starting 15 years after diagnosis.119

Summary

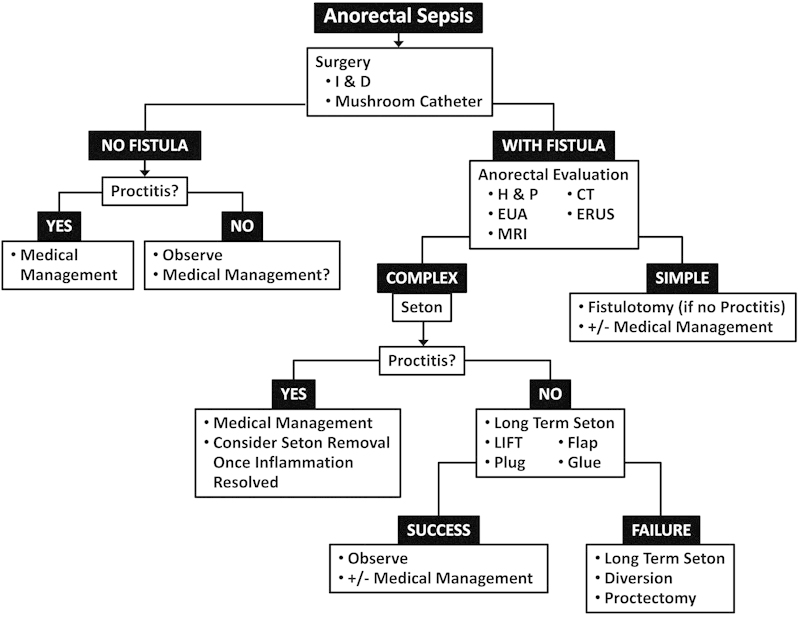

In summary, anorectal manifestations of CD are common and varied. Straightforward anorectal disease in the absence of active proctitis can be managed in the same way as in the general population, but in the presence of active anorectal inflammation, management is complex. Successful resolution of anorectal CD requires a careful approach with knowledge of the inherent risks and complications, and is usually multimodality, requiring active medical management after eradication of sepsis. Refractory disease requires conservative management, but may result in the eventual need for diversion or proctectomy. A flow diagram for a suggested management schema is provided (Fig. 2). The careful surgeon should be aware of the many modalities to approach in treated this complex disease process.

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram for suggested management scheme for Crohn-disease-associated anorectal infections. H & P, history and physical; I & D, incision and drainage; CT, computed tomography; ERUS, endorectal ultrasound; EUA, exam under anesthesia; LIFT, ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

References

- 1.Crohn B B, Ginzberg L, Oppenheimer G D. Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity. JAMA. 1932;99:1323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirsner J B. Historical origins of current IBD concepts. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7(2):175–184. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colles A. Practical observations upon certain diseases of intestines, colon and rectum. Dublin Hospital Reports. 1830;5:131. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bissell A D. Localized chronic ulcerative ileitis. Ann Surg. 1934;99(6):957–966. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193406000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penner A, Crohn B B. Perianal fistulae as a complication of regional ileitis. Ann Surg. 1938;108(5):867–873. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193811000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hellers G, Bergstrand O, Ewerth S, Holmström B. Occurrence and outcome after primary treatment of anal fistulae in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1980;21(6):525–527. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.6.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandborn W J, Fazio V W, Feagan B G, Hanauer S B. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee . AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1508–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz D A, Loftus E V Jr, Tremaine W J. et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):875–880. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safar B, Sands D. Perianal Crohn's disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2007;20(4):282–293. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams D R, Coller J A, Corman M L, Nugent F W, Veidenheimer M C. Anal complications in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24(1):22–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02603444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A. et al. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8(4):244–250. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts P L, Schoetz D J Jr, Pricolo R, Veidenheimer M C. Clinical course of Crohn's disease in older patients. A retrospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33(6):458–462. doi: 10.1007/BF02052138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre J P, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):650–656. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rankin G B, Watts H D, Melnyk C S, Kelley M L Jr. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: extraintestinal manifestations and perianal complications. Gastroenterology. 1979;77(4 Pt 2):914–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelbmann C M, Rogler G, Gross V. et al. Prior bowel resections, perianal disease, and a high initial Crohn's disease activity index are associated with corticosteroid resistance in active Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(6):1438–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keighley M R, Allan R N. Current status and influence of operation on perianal Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1986;1(2):104–107. doi: 10.1007/BF01648416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.el Mouaaouy A, Tolksdorf A, Starlinger M, Becker H D. [Endoscopic sonography of the anorectum in inflammatory rectal diseases] Z Gastroenterol. 1992;30(7):486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovannini M, Bories E, Moutardier V. et al. Drainage of deep pelvic abscesses using therapeutic echo endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35(6):511–514. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rieger N, Tjandra J, Solomon M. Endoanal and endorectal ultrasound: applications in colorectal surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(8):671–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.02884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caliste X, Nazir S, Goode T. et al. Sensitivity of computed tomography in detection of perirectal abscess. Am Surg. 2011;77(2):166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pritchard T J, Schoetz D J Jr, Roberts P L, Murray J J, Coller J A, Veidenheimer M C. Perirectal abscess in Crohn's disease. Drainage and outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33(11):933–937. doi: 10.1007/BF02139102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohn N, Korelitz B I, Weinstein M A. Anorectal Crohn's disease: definitive surgery for fistulas and recurrent abscesses. Am J Surg. 1980;139(3):394–397. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(80)90301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz D A, Wiersema M J, Dudiak K M. et al. A comparison of endoscopic ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and exam under anesthesia for evaluation of Crohn's perianal fistulas. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(5):1064–1072. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaefer O, Lohrmann C, Langer M. Assessment of anal fistulas with high-resolution subtraction MR-fistulography: comparison with surgical findings. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19(1):91–98. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchanan G N, Halligan S, Bartram C I, Williams A B, Tarroni D, Cohen C R. Clinical examination, endosonography, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of fistula in ano: comparison with outcome-based reference standard. Radiology. 2004;233(3):674–681. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beets-Tan R G, Beets G L, van der Hoop A G. et al. Preoperative MR imaging of anal fistulas: Does it really help the surgeon? Radiology. 2001;218(1):75–84. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01dc0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchanan G N, Halligan S, Williams A B. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for primary fistula in ano. Br J Surg. 2003;90(7):877–881. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dejaco C, Harrer M, Waldhoer T, Miehsler W, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W. Antibiotics and azathioprine for the treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(11-12):1113–1120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernstein L H, Frank M S, Brandt L J, Boley S J. Healing of perineal Crohn's disease with metronidazole. Gastroenterology. 1980;79(3):599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turunen U M, Färkkilä M A, Hakala K. et al. Long-term treatment of ulcerative colitis with ciprofloxacin: a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(5):1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandt L J, Bernstein L H, Boley S J, Frank M S. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn's disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83(2):383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakobovits J, Schuster M M. Metronidazole therapy for Crohn's disease and associated fistulae. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79(7):533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson D C, May G R, Fick G H, Sutherland L R. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123(2):132–142. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-2-199507150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinterleitner T A, Petritsch W, Aichbichler B, Fickert P, Ranner G, Krejs G J. Combination of cyclosporine, azathioprine and prednisolone for perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35(8):603–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egan L J, Sandborn W J, Tremaine W J. Clinical outcome following treatment of refractory inflammatory and fistulizing Crohn's disease with intravenous cyclosporine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(3):442–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gurudu S R, Griffel L H, Gialanella R J, Das K M. Cyclosporine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: short-term and long-term results. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29(2):151–154. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandborn W J, Present D H, Isaacs K L. et al. Tacrolimus for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(2):380–388. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Present D H, Rutgeerts P, Targan S. et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sands B E, Anderson F H, Bernstein C N. et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parsi M A, Lashner B A, Achkar J P, Connor J T, Brzezinski A. Type of fistula determines response to infliximab in patients with fistulous Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(3):445–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ricart E, Panaccione R, Loftus E V, Tremaine W J, Sandborn W J. Infliximab for Crohn's disease in clinical practice at the Mayo Clinic: the first 100 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(3):722–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alzafiri R, Holcroft C A, Malolepszy P, Cohen A, Szilagyi A. Infliximab therapy for moderately severe Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a retrospective comparison over 6 years. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:9–17. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S16168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiff M H, Burmester G R, Kent J D. et al. Safety analyses of adalimumab (HUMIRA) in global clinical trials and US postmarketing surveillance of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(7):889–894. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.043166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colombel J F, Schwartz D A, Sandborn W J. et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Gut. 2009;58(7):940–948. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lichtiger S, Binion D G, Wolf D C. et al. The CHOICE trial: adalimumab demonstrates safety, fistula healing, improved quality of life and increased work productivity in patients with Crohn's disease who failed prior infliximab therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(10):1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schreiber S. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn's disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4(6):375–389. doi: 10.1177/1756283X11413315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandborn W J, Feagan B G, Stoinov S. et al. PRECISE 1 Study Investigators . Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):228–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrance I C. et al. PRECISE 2 Study Investigators . Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schreiber S, Lawrance I C, Thomsen O O, Hanauer S B, Bloomfield R, Sandborn W J. Randomised clinical trial: certolizumab pegol for fistulas in Crohn's disease—subgroup results from a placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(2):185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colombel J F, Sandborn W J, Reinisch W. et al. SONIC Study Group . Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guidi L, Pugliese D, Armuzzi A. Update on the management of inflammatory bowel disease: specific role of adalimumab. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:163–172. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S14558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hämäläinen K P Sainio A P Cutting seton for anal fistulas: high risk of minor control defects Dis Colon Rectum 199740121443–1446., discussion 1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ritchie R D, Sackier J M, Hodde J P. Incontinence rates after cutting seton treatment for anal fistula. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(6):564–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nordgren S, Fasth S, Hultén L. Anal fistulas in Crohn's disease: incidence and outcome of surgical treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1992;7(4):214–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00341224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matos D, Lunniss P J, Phillips R K. Total sphincter conservation in high fistula in ano: results of a new approach. Br J Surg. 1993;80(6):802–804. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh B, George B D, Mortensen N J. Surgical therapy of perianal Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(10):988–992. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.07.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams J G, Rothenberger D A, Nemer F D, Goldberg S M. Fistula-in-ano in Crohn's disease. Results of aggressive surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(5):378–384. doi: 10.1007/BF02053687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halme L, Sainio A P. Factors related to frequency, type, and outcome of anal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(1):55–59. doi: 10.1007/BF02053858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sangwan Y P, Schoetz D J Jr, Murray J J, Roberts P L, Coller J A. Perianal Crohn's disease. Results of local surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(5):529–535. doi: 10.1007/BF02058706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Faucheron J L, Saint-Marc O, Guibert L, Parc R. Long-term seton drainage for high anal fistulas in Crohn's disease—a sphincter-saving operation? Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(2):208–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02068077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pearl R K Andrews J R Orsay C P et al. Role of the seton in the management of anorectal fistulas Dis Colon Rectum 1993366573–577., discussion 577-579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thornton M, Solomon M J. Long-term indwelling seton for complex anal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(3):459–463. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchanan G N, Owen H A, Torkington J, Lunniss P J, Nicholls R J, Cohen C R. Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg. 2004;91(4):476–480. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eitan A, Koliada M, Bickel A. The use of the loose seton technique as a definitive treatment for recurrent and persistent high trans-sphincteric anal fistulas: a long-term outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(6):1116–1119. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0826-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hobbiss J H, Schofield P F. Management of perianal Crohn's disease. J R Soc Med. 1982;75(6):414–417. doi: 10.1177/014107688207500609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morrison J G, Gathright J B Jr, Ray J E, Ferrari B T, Hicks T C, Timmcke A E. Surgical management of anorectal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(6):492–496. doi: 10.1007/BF02554504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Williams J G, MacLeod C A, Rothenberger D A, Goldberg S M. Seton treatment of high anal fistulae. Br J Surg. 1991;78(10):1159–1161. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Church J M. Biological immunomodulators improve the healing rate in surgically treated perianal Crohn's fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(10):1217–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cintron J R, Park J J, Orsay C P, Pearl R K, Nelson R L, Abcarian H. Repair of fistulas-in-ano using autologous fibrin tissue adhesive. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(5):607–613. doi: 10.1007/BF02234135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cintron J R Park J J Orsay C P et al. Repair of fistulas-in-ano using fibrin adhesive: long-term follow-up Dis Colon Rectum 2000437944–949., discussion 949-950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park J J, Cintron J R, Orsay C P. et al. Repair of chronic anorectal fistulae using commercial fibrin sealant. Arch Surg. 2000;135(2):166–169. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Swinscoe M T, Ventakasubramaniam A K, Jayne D G. Fibrin glue for fistula-in-ano: the evidence reviewed. Tech Coloproctol. 2005;9(2):89–94. doi: 10.1007/s10151-005-0204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zmora O, Neufeld D, Ziv Y. et al. Prospective, multicenter evaluation of highly concentrated fibrin glue in the treatment of complex cryptogenic perianal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(12):2167–2172. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sehgal R, Koltun W A. Fibrin glue for the treatment of perineal fistulous Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2216–2219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lindsey I, Smilgin-Humphreys M M, Cunningham C, Mortensen N J, George B D. A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(12):1608–1615. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vitton V, Gasmi M, Barthet M, Desjeux A, Orsoni P, Grimaud J C. Long-term healing of Crohn's anal fistulas with fibrin glue injection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(12):1453–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grimaud J C Munoz-Bongrand N Siproudhis L et al. Groupe d'Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif Fibrin glue is effective healing perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease Gastroenterology 201013872275–2281., e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Loungnarath R, Dietz D W, Mutch M G, Birnbaum E H, Kodner I J, Fleshman J W. Fibrin glue treatment of complex anal fistulas has low success rate. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(4):432–436. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Champagne B J, O'Connor L M, Ferguson M, Orangio G R, Schertzer M E, Armstrong D N. Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(12):1817–1821. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Badylak S F. The extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13(5):377–383. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garg P, Song J, Bhatia A, Kalia H, Menon G R. The efficacy of anal fistula plug in fistula-in-ano: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(10):965–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.O'Riordan J M, Datta I, Johnston C, Baxter N N. A systematic review of the anal fistula plug for patients with Crohn's and non-Crohn's related fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(3):351–358. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318239d1e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gonsalves S, Sagar P, Lengyel J, Morrison C, Dunham R. Assessment of the efficacy of the rectovaginal button fistula plug for the treatment of ileal pouch-vaginal and rectovaginal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1877–1881. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b55560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ellis C N. Outcomes after repair of rectovaginal fistulas using bioprosthetics. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(7):1084–1088. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Koperen P J, Bemelman W A, Gerhards M F. et al. The anal fistula plug treatment compared with the mucosal advancement flap for cryptoglandular high transsphincteric perianal fistula: a double-blinded multicenter randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(4):387–393. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318206043e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ortiz H, Marzo J, Ciga M A, Oteiza F, Armendáriz P, de Miguel M. Randomized clinical trial of anal fistula plug versus endorectal advancement flap for the treatment of high cryptoglandular fistula in ano. Br J Surg. 2009;96(6):608–612. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rojanasakul A. LIFT procedure: a simplified technique for fistula-in-ano. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13(3):237–240. doi: 10.1007/s10151-009-0522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bleier J I, Moloo H, Goldberg S M. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract: an effective new technique for complex fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(1):43–46. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181bb869f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ooi K, Skinner I, Croxford M, Faragher I, McLaughlin S. Managing fistula-in-ano with ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract procedure: the Western Hospital experience. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(5):599–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shanwani A, Nor A M, Amri N. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT): a sphincter-saving technique for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(1):39–42. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181c160c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abcarian A M, Estrada J J, Park J. et al. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract: early results of a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(7):778–782. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318255ae8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tan K K, Tan I J, Lim F S, Koh D C, Tsang C B. The anatomy of failures following the ligation of intersphincteric tract technique for anal fistula: a review of 93 patients over 4 years. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(11):1368–1372. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822bb55e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Joo J S, Weiss E G, Nogueras J J, Wexner S D. Endorectal advancement flap in perianal Crohn's disease. Am Surg. 1998;64(2):147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soltani A, Kaiser A M. Endorectal advancement flap for cryptoglandular or Crohn's fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(4):486–495. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181ce8b01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hull T L, Fazio V W. Surgical approaches to low anovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. Am J Surg. 1997;173(2):95–98. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kodner I J Mazor A Shemesh E I Fry R D Fleshman J W Birnbaum E H Endorectal advancement flap repair of rectovaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas Surgery 19931144682–689., discussion 689-690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sher M E, Bauer J J, Gelernt I. Surgical repair of rectovaginal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease: transvaginal approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(8):641–648. doi: 10.1007/BF02050343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Galandiuk S Kimberling J Al-Mishlab T G Stromberg A J Perianal Crohn disease: predictors of need for permanent diversion Ann Surg 20052415796–801., discussion 801-802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mueller M H, Geis M, Glatzle J. et al. Risk of fecal diversion in complicated perianal Crohn's disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(4):529–537. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0029-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kasparek M S, Glatzle J, Temeltcheva T, Mueller M H, Koenigsrainer A, Kreis M E. Long-term quality of life in patients with Crohn's disease and perianal fistulas: influence of fecal diversion. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(12):2067–2074. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yamamoto T Allan R N Keighley M R Effect of fecal diversion alone on perianal Crohn's disease World J Surg 200024101258–1262., discussion 1262-1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cohen J L, Stricker J W, Schoetz D J Jr, Coller J A, Veidenheimer M C. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(10):825–828. doi: 10.1007/BF02554548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yamamoto T, Bain I M, Allan R N, Keighley M R. Persistent perineal sinus after proctocolectomy for Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(1):96–101. doi: 10.1007/BF02235190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rius J, Nessim A, Nogueras J J, Wexner S D. Gracilis transposition in complicated perianal fistula and unhealed perineal wounds in Crohn's disease. Eur J Surg. 2000;166(3):218–222. doi: 10.1080/110241500750009311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Buchmann P, Keighley M R, Allan R N, Thompson H, Alexander-Williams J. Natural history of perianal Crohn's disease. Ten year follow-up: a plea for conservatism. Am J Surg. 1980;140(5):642–644. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(80)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sweeney J L, Ritchie J K, Nicholls R J. Anal fissure in Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1988;75(1):56–57. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fleshner P R, Schoetz D J Jr, Roberts P L, Murray J J, Coller J A, Veidenheimer M C. Anal fissure in Crohn's disease: a plea for aggressive management. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(11):1137–1143. doi: 10.1007/BF02048328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Steele S R. Operative management of Crohn's disease of the colon including anorectal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87(3):611–631. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Linares L, Moreira L F, Andrews H, Allan R N, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley M R. Natural history and treatment of anorectal strictures complicating Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1988;75(7):653–655. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Alexander-Williams J, Allan A, Morel P, Hawker P C, Dykes P W, O'Connor H. The therapeutic dilatation of enteric strictures due to Crohn's disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1986;68(2):95–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Williamson M E, Hughes L E. Bowel diversion should be used with caution in stenosing anal Crohn's disease. Gut. 1994;35(8):1139–1140. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.8.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nelson R L, Abcarian H, Davis F G, Persky V. Prevalence of benign anorectal disease in a randomly selected population. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(4):341–344. doi: 10.1007/BF02054218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jeffery P J, Parks A G, Ritchie J K. Treatment of haemorrhoids in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1977;1(8021):1084–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wolkomir A F, Luchtefeld M A. Surgery for symptomatic hemorrhoids and anal fissures in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(6):545–547. doi: 10.1007/BF02049859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Karin E, Avital S, Dotan I, Skornick Y, Greenberg R. Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation in patients with Crohn's disease. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(1):111–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ingle S B, Loftus E V Jr. The natural history of perianal Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(10):963–969. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.07.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Singh B, McC Mortensen N J, Jewell D P, George B. Perianal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2004;91(7):801–814. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mahmoud N, Rombeau J L, Ross H M, Fry R D. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004. Colon and rectum. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sjödahl R I, Myrelid P, Söderholm J D. Anal and rectal cancer in Crohn's disease. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5(5):490–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ky A, Sohn N, Weinstein M A, Korelitz B I. Carcinoma arising in anorectal fistulas of Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41(8):992–996. doi: 10.1007/BF02237388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Connell W R, Sheffield J P, Kamm M A, Ritchie J K, Hawley P R, Lennard-Jones J E. Lower gastrointestinal malignancy in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1994;35(3):347–352. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Weedon D D, Shorter R G, Ilstrup D M, Huizenga K A, Taylor W F. Crohn's disease and cancer. N Engl J Med. 1973;289(21):1099–1103. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197311222892101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Perianal Crohn's disease: classification and clinical evaluation. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(10):959–962. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.07.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]