Abstract

Lemierre syndrome is an uncommon condition classically described in acute oropharyngeal infection with septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and metastatic septic embolism particularly to the lungs. It is commonly described in young healthy adults with isolation of Fusobacterium necrophorum. We describe a case of Lemierre syndrome in a 50-year-old man with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus presenting with a neck abscess secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae. Our patient made good recovery to appropriate antimicrobial therapy, prompt surgical drainage, and anticoagulation. Anticoagulation remains controversial and we review the literature for its role in Lemierre syndrome.

Keywords: Lemierre syndrome, internal jugular vein thrombosis, septic thrombophlebitis, anticoagulation, Klebsiella pneumoniae, diabetes mellitus, neck abscess

Lemierre syndrome was first described in 1936 in 20 patients presenting with oropharyngeal infection with septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and secondary septic embolism most commonly to the lungs. Mortality was high with death in 18 of 20 patients described during the preantibiotic era.1 Although a rare presentation since the advent of antibiotics, the increased number of patients reported in the last few years have been attributed to the modest use of antibiotics and improved methods for detection.2,3 The most common organism isolated is Fusobacterium necrophorum, a gram-negative anaerobe found in the oropharynx. However, there are increasing reports of Lemierre syndrome with Klebsiella pneumoniae in the context of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.4,5,6 Treatment typically involves prompt antimicrobial therapy and surgical drainage of accessible infected collections, but the role of anticoagulation is controversial due to the lack of controlled studies.

In this case report, we describe a newly diagnosed diabetic patient with Lemierre syndrome presenting with a neck abscess secondary to K. pneumoniae species. Thereafter, we review the literature on the role of anticoagulation.

Case Report

A 50-year-old Filipino man presented with a painful left neck swelling for 8 days associated with fever and chills. He suffered an unwitnessed syncopal episode before admission but had no chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, or focal neurological symptoms. He had a productive cough with white sputum for 1 week, but other systemic review was unremarkable. There was no recent travel or contact history and he had no relevant past medical illnesses of note.

On examination, he was febrile (38.5°C), tachycardic (pulse 115), and hypotensive (BP 86/48), with a respiratory rate of 20 cycles per minute and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. He was alert but lethargic looking. There was a large left neck mass, 5 × 4 cm in size which was warm and tender with overlying erythema. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy and the tonsils were not enlarged or deviated. He was able to speak in full sentences and there was no stridor. Examinations of the other systems were unremarkable.

Initial laboratory investigations showed leucocytosis (white cell count 14.9 × 109/L) with left shift and an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). He was also diagnosed with diabetes mellitus with a random blood sugar of 22 mmol/L and a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 12.1%. An electrocardiogram was sinus in rhythm and a plain chest radiograph showed no consolidation or pleural effusion.

He was managed with intravenous fluids and inotropic support for septic shock and commenced on intravenous ceftazidime, cloxacillin, and clindamycin. He received subcutaneous insulin and subsequently oral hypoglycemics for diabetes mellitus.

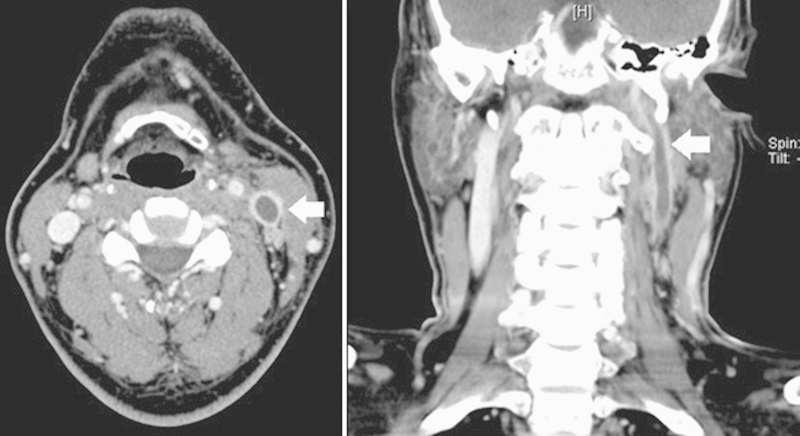

A computed tomography (CT) of the neck showed a large left-sided septated collection with enhancing wall in keeping with an abscess formation (Fig. 1). There was complete thrombosis of the left internal jugular vein (Fig. 2). In addition, thrombosis was seen in the left sigmoid sinus, distal left transverse sinus, left external jugular vein, and proximal left facial vein as well. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed no evidence of intra-abdominal collections.

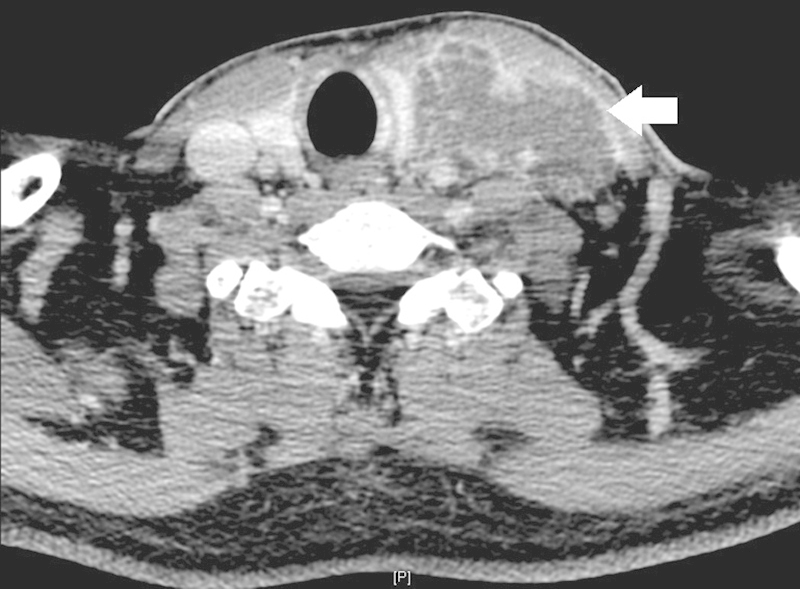

Fig. 1.

Axial computed tomography showing a large left septated neck abscess (arrow).

Fig. 2.

Axial and coronal sections on computed tomography showing complete thrombosis of the left internal jugular vein with cranial extension (arrow).

He underwent emergency incision and drainage of the neck abscess under general anesthesia with findings of pockets of retroclavicular abscesses and also deep to the left sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Both cultures from blood and neck abscess grew extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) negative K. pneumoniae and urine cultures had no growth. White cell count had improved from 19.2 × 109/L to 13.2 × 109/L, pre- and postoperative, respectively. Antibiotics were changed to intravenous cefazolin based upon culture sensitivities with the intention to complete 6 weeks duration.

In view of the extensive venous thrombosis involving left internal jugular veins with extension to the sigmoid and transverse sinus, he was started on anticoagulation. He was treated with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin with plans to complete a total 3 months of anticoagulation.

Discussion

In this case report, we described a middle age patient with newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus who presented with a neck abscess. Imaging of the neck abscess revealed deep venous thrombosis involving the left internal jugular vein consistent with Lemierre syndrome. Although classically F. necrophorum has been described in young patients with Lemierre syndrome, there have been increasing reports of K. pneumoniae being isolated in older patients with poorly controlled diabetic mellitus.4,5,6 This is an interesting observation although the reason for this is not clear. Locally, it has been reported that K. pneumoniae accounted for 27.1% of pathogens cultured from deep neck abscesses, of which half had diabetes mellitus.7 Other organisms isolated in Lemierre syndrome include group A streptococci, Streptococcus pyogenes, Bacteroides melaninogenicus, Eikenella corrodens, and Leptotrichia buccalis.4,5 In our patient, K. pneumoniae was isolated from both neck abscess and blood cultures.

Priority of treatment involves prompt antimicrobial therapy with reported mortality of 0 to 18%3 compared with 25% in cases when antibiotics were delayed.8 In addition, surgical drainage of accessible collections is also important in conjunction with antibiotic therapy. Internal jugular vein ligation is now rarely performed unless indicated in patients with persistent septic embolization despite antibiotic therapy.9

The role of anticoagulation in Lemierre syndrome is controversial and recommendations are often based on anecdotal evidence. In Lemierre syndrome, there is a significant risk of metastatic embolism to organs, especially to the lungs. These complications manifest as multiple nodular lung infiltrates with cavitation and may even rapidly progress despite antibiotics with formation of empyema in 10 to 15% of cases.3,10 However, these pulmonary septic embolisms are often not hemodynamically significant and may even be asymptomatic in some cases. The role of anticoagulation would be to prevent the associated complications of respiratory failure and propagation of the septic thrombus into the intracranial sinuses.11 Due to the lack of randomized studies in this rare illness, it remains unclear if anticoagulation will reduce these complications and improve outcome.

It has been argued that thrombosis associated with Lemierre syndrome will spontaneously resolve, but it is also unclear if anticoagulation will expedite the resolution of thrombosis.9 Many have reported successful treatment in both patients with4,6,12,13,14,15 or without anticoagulation2,16,17,18,19 in conjunction with antimicrobial therapy (Table 1). In a small retrospective study of 11 patients with internal jugular venous thrombosis associated with deep neck infection in intravenous drug abusers, there were no serious adverse consequences in those patients who did not receive anticoagulation.20 In a case series, anticoagulation in a patient did not prevent a left frontal lobe seizure attributed to septic embolism.2 Internal jugular venous thrombosis had also persisted despite anticoagulation in another patient.2 On the other hand, another case series had also described an episode of recurrent thrombosis in a patient who did not receive anticoagulation.9 Others have also reported that 11 of 41 patients (26.8%) demonstrated improvement with the addition of anticoagulation, with recommendations for use in cases of extensive thrombosis.13

Table 1. Case studies of Lemierre syndrome and anticoagulation treatment.

| Study | N | Isolated organisms | Thrombosis | Complications | Anticoagulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Duration | |||||

| Garbati et al6 | 1 | Fusobacterium necrophorum | Internal JV, sigmoid, and transverse sinus | Nil | 1 (100%) | 6 wk |

| Krishna et al12 | 2 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus | Internal JV, sigmoid, transverse and sagittal sinus | Pulmonary septic emboli, occipital infarct | 2 (100%) | 6 wk |

| Lee et al19 | 1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Internal JV | Brain abscesses, seizures | 0 (0%) | - |

| Lim and Pua14 | 1 | K. pneumoniae | Internal JV | Pulmonary septic emboli | 1 (100%) | Unknown |

| Tsai et al4 | 1 | K. pneumoniae | Internal JV, sigmoid sinus | Pulmonary abscess | 1 (100%) | Unknown |

| Ridgway et al9 | 3 | F. necrophorum | Internal and external JV | Pulmonary cavities, subdural empyema, septic arthritis | 1 (33%) | 6 wk |

| Lu et al2 | 3 | F. necrophorum | Internal and external JV | Pulmonary cavities, ARDS, frontal lobe seizures | 2 (67%) | 3-4 mo |

| Bondy and Grant11 | 2 | F. necrophorum | Internal JV | Pulmonary emboli | 2 (100%) | 4 wk |

| Chang and Wu15 | 1 | Nil | Common JV, subclavian vein | Pulmonary septic emboli | 1 (100%) | 2 wk |

| Singaporewalla et al5 | 1 | K. pneumoniae | Internal JV | Nil | 0 (0%) | - |

| Dool et al18 | 3 | F. necrophorum | Internal and external JV | Pulmonary cavities and empyema | 0 (0%) | - |

| Moore et al13 | 1 | Nil | Internal JV, brachiocephalic, subclavian, axillary and basilic vein | Pulmonary cavities | 1 (100%) | 6 mo |

| Edibam et al16 | 1 | F. necrophorum | External JV | Pulmonary septic emboli | 0 (0%) | - |

| Screaton et al17 | 4 | F. necrophorum, enterococcus species | Internal and external JV | Pulmonary empyema and infarction | 2 (50%) | Unknown |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; JV, jugular vein; N, number of patients.

Some authors recommend anticoagulation for a select group of patients with lack of response despite 48 to 72 hours of adequate antimicrobial therapy, underlying thrombophilia, and progression of thrombosis or retrograde cavernous sinus thrombosis.2,21 In patients where anticoagulation has commenced, optimal duration is unclear and may range from 4 weeks to 6 months.11,13 Furthermore, internal jugular venous thrombosis may persist long after infection has been resolved despite anticoagulation,2,5 but others have reported resolution only after 2 weeks.12

Other issues to consider when starting anticoagulation is assessing the bleeding risks, especially since disseminated intravascular coagulation is not uncommon.2 However, anticoagulation in Lemierre syndrome appears to be relatively safe with no attributed bleeding complications4,6,12,13,14,15 although there was a reported complication of pulmonary hemorrhage in a patient initiated on anticoagulation.22 Many reported cases were young individuals with little comorbidities, and hence risk benefit assessments need to be individualized.

Internal jugular venous thrombosis may commonly develop from causes other than infection such as central venous access devices; thrombophilia; and malignancies of lung, colon, breast, and ovary. Bilateral internal jugular venous thrombosis has been associated with underlying malignancy and screening for malignancy should be considered.23 Similar to Lemierre syndrome, thrombus propagation and recurrent thromboembolic events are of concern with reported pulmonary embolism in 2.7 to 10.3% of cases.23,24 Anticoagulation for 3 months is recommended in the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) 2012 guidelines with associated reduction in recurrent thromboembolism in patients with bland internal jugular vein thrombosis.25 A trend toward mortality benefit with anticoagulation has been reported in isolated internal jugular vein thrombosis.24 In catheter-associated thrombosis, removal is advised when the catheter is no longer indicated, but it is unclear if this should be deferred after an initial period of anticoagulation.25 The catheter may be kept if further intravenous access is required in patients with difficult vascular access, unless there are contraindications to anticoagulation or the line becomes infected.25,26 Although the role of interventional techniques is unclear, successful percutaneous thrombectomy and catheter-directed thrombolysis have been reported in internal jugular venous thrombosis.27,28 Interestingly, superior vena cava filter placement has also been described but data supporting this is lacking.24

In conclusion, there are currently no clear guidelines for the use of anticoagulation in Lemierre syndrome due to its rarity and lack of randomized controlled studies. Until more evidence is available, appropriate and prompt institution of antibiotics remains the mainstay of therapy with surgical drainage where indicated. However, anticoagulation should be considered in high-risk patients with extensive internal jugular venous thrombosis or extension despite antimicrobial therapy.

References

- 1.Lemierre A. On certain septicemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;1:701–703. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu M D, Vasavada Z, Tanner C. Lemierre syndrome following oropharyngeal infection: a case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(1):79–83. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.01.070247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riordan T, Wilson M. Lemierre's syndrome: more than a historical curiosa. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(944):328–334. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.014274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai Y J, Lin Y C, Harnnd D J, Chiang R P, Wu H M. A Lemierre syndrome variant caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111(7):403–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singaporewalla R M, Clarke M J, Krishnan P U, Tan D E. Is this a variant of Lemierre's syndrome? Singapore Med J. 2006;47(12):1092–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garbati M A, Ahsan A M, Hakawi A M. Lemierre's syndrome due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in a 63-year-old man with diabetes: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2012;6:97. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y Q, Kanagalingam J. Bacteriology of deep neck abscesses: a retrospective review of 96 consecutive cases. Singapore Med J. 2011;52(5):351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leugers C M, Clover R. Lemierre syndrome: postanginal sepsis. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1995;8(5):384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridgway J M, Parikh D A, Wright R. et al. Lemierre syndrome: a pediatric case series and review of literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagelskjaer L H, Prag J, Malczynski J, Kristensen J H. Incidence and clinical epidemiology of necrobacillosis, including Lemierre's syndrome, in Denmark 1990-1995. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17(8):561–565. doi: 10.1007/BF01708619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bondy P, Grant T. Lemierre's syndrome: what are the roles for anticoagulation and long-term antibiotic therapy? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(9):679–683. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishna K, Diwan A G, Gupt A. Lemierre's syndrome—the syndrome quite forgotten. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore B A Dekle C Werkhaven J Bilateral Lemierre's syndrome: a case report and literature review Ear Nose Throat J 2002814234–236., 238-240, 242 passim [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim A L, Pua K C. Lemierre syndrome. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67(3):340–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang W E, Wu L S. Lemierre's syndrome: a case report. Taiwan Soc Int Med. 2007;18:287–292. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edibam C, Gharbi R, Weekes J W. Septic jugular thrombophlebitis and pulmonary embolism: a case report. Crit Care Resusc. 2000;2(1):38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Screaton N J, Ravenel J G, Lehner P J, Heitzman E R, Flower C D. Lemierre syndrome: forgotten but not extinct—report of four cases. Radiology. 1999;213(2):369–374. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv09369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dool H, Soetekouw R, van Zanten M, Grooters E. Lemierre's syndrome: three cases and a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(8):651–654. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0880-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee W S, Wang F D, Shieh Y H, Teng S O, Ou T Y. Lemierre syndrome complicating multiple brain abscesses caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae cured by fosfomycin and meropenem combination therapy. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45(1):72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin D, Reeck J B, Murr A H. Internal jugular vein thrombosis and deep neck infection from intravenous drug use: management strategy. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(1):56–60. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lustig L R, Cusick B C, Cheung S W, Lee K C. Lemierre's syndrome: two cases of postanginal sepsis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112(6):767–772. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoehn K S. Lemierre's syndrome: the controversy of anticoagulation. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1415–1416. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gbaguidi X, Janvresse A, Benichou J, Cailleux N, Levesque H, Marie I. Internal jugular vein thrombosis: outcome and risk factors. QJM. 2011;104(3):209–219. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheikh M A, Topoulos A P, Deitcher S R. Isolated internal jugular vein thrombosis: risk factors and natural history. Vasc Med. 2002;7(3):177–179. doi: 10.1191/1358863x02vm440oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kearon C, Akl E A, Comerota A J. et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2, Suppl):e419S–e494S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucher N. Clinical practice. Deep-vein thrombosis of the upper extremities. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1008740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tajima H, Murata S, Kumazaki T, Ichikawa K, Tajiri T, Yamamoto Y. Successful interventional treatment of acute internal jugular vein thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(2):467–469. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang R, Horne M K III, Mayo D J, Doppman J L. Pulse-spray treatment of subclavian and jugular venous thrombi with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7(6):845–851. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(96)70858-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]