Abstract

Objectives

Patients with frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) may be agraphic. The study aimed at characterizing agraphia in individuals with a P301L MAPT mutation.

Methods

Two pairs of siblings with FTDP-17 were longitudinally examined for agraphia in relation to language and cognitive deficits.

Results

All patients presented with dysexecutive agraphia. In addition, in the first pair of siblings one sibling demonstrated spatial agraphia with less pronounced allographic agraphia and the other sibling had aphasic agraphia. Aphasic agraphia was also present in one sibling from the second pair.

Conclusion

Agraphia associated with FTDP-17 is very heterogeneous.

Keywords: frontotemporal dementia, writing, neuropsychological assessment, dysexecutive agraphia, spatial agraphia, aphasic agraphia

Writing is a complex function requiring the integration of many cognitive and executive processes including language, orthographic lexical representations, visuospatial skills, planning, working memory, graphemic representations and the ability to program skilled movements (praxis). Thus, writing impairments can be related not only to language-orthographic dysfunction but also to executive and spatial dysfunctions as well as apraxia. Apart from the commonly diagnosed aphasic agraphias (e.g. lexical, phonological and semantic agraphia) other specific forms of agraphia, related to non-linguistic deficits are also frequently described in the literature (see: Rapscak &Beeson, 2002; Roeltgen, 2003).

Traditional neurological classification of agraphia includes pure agraphia, apraxic agraphia, spatial agraphia, aphasic agraphia with lexical, phonological, deep and semantic subtypes (Luzzatti, Laiacona & Agazzi, 2003; Roeltgen, 2003). Additionally, agraphia is often caused by focal lesions and therefore sometimes it is classified by lesion location; e.g. parietal agraphia or callosal agraphia. Apraxic agraphia is characterized by a disorder in accessing and implementing the correct writing movement programs. In several neurodegenerative disorders, such as corticobasal degeneration, lateralized symptoms and signs may be present, and patients with this disorder may exhibit an asymmetrical apraxic agraphia, that is often associated with an ideomotor apraxia (Heilman et al., 2008). Some patients with corticobasal degeneration or posterior cortical atrophy may also present with features of Balint’s syndrome which includes simultanognosia, optic ataxia, and apraxia of gaze as well as having the signs of the unilateral neglect syndrome, all potentially contributing to the development of spatial agraphia (Roeltgen, 2003). In contrast, patients with frontal lobe dysfunction may predominantly experience problems with planning, organizing ideas and maintaining attention during narrative writing, but may not have other forms of agraphia. Thus, writing to dictation may remain intact in these patients. This type of writing disturbances has been recently termed “dysexecutive agraphia” by Ardila & Surloff (2006).

Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) is a subtype of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) / frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). FTDP-17 may be associated with mutations in the gene encoding the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) and in the progranuline gene (GRN) (Clark, 1998, Hutton, 2001, Baker, 2006). This rare neurodegenerative disorder is characterized by behavioral, cognitive and motor manifestations. Despite lack of definite diagnostic criteria of FTDP-17, the common clinical presentation of the disorder was defined at a consensus conference in 1996 (Foster et al., 1997). Behavioral disturbances such as behavioral disinhibition with poor impulse control, and inappropriate social conduct as well as apathy are closely linked to other forms of executive dysfunction including impaired foresight and planning, disturbed cognitive control and reduced mental flexibility. Cognitive and behavioral deficits often precede the extrapyramidal and corticospinal motor signs and symptoms. In patients with this disorder, executive deficits appear first and often rapidly progress.

Although patients with FTLD have been shown to have various types of agraphia: e.g. aphasic agraphia (Ichikawa et al., 2008), including jargonagraphia (Östberg, Bogdanovic, Fernaeus & Wahlund, 2001), and allographic agraphia (Menichelli, Rapp & Semenza, 2008), there has been only few descriptions of the writing impairment associated with FTDP-17 with the P301L MAPT mutation (Bird et al., 1999; Kodama et al., 2000). The agraphia profiles in those patients with the respective neuroimaging findings are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Previous descriptions of agraphia in patients with P301 L MAPT mutation

| Patient | Symptom onset | Possible type of agraphia | Cognitive function | Neuroimaging findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | dysexecutive agraphia | severe dementia 2 years after the onset, severe executive and language dysfunction | bilateral frontotemporal and subcortical atrophy | Kodama et al., 2002 |

| 2 | 56 | apraxic or/and aphasic agraphia | preserved occupational functioning (surgeon) at the onset of agraphia; language and memory dysfunction | bilateral frontal and temporal atrophy (4 years after the onset of agraphia) | Subject II-4 Bird et al., 1999 |

| 3 | 47 | aphasic or/and apraxic agraphia? | executive dysfunction | diffuse cerebrocortical atrophy | Subject III-2 Bird et al., 1999 |

Whereas these reports do suggest the presence of agraphia in patients with FTDP-17, a detailed analysis of the abnormalities that characterize these patients’ writing impairment has not been reported. Since the hemispheric atrophy present in patients with FTDP-17 is often found in both the anterior and posterior brain regions (Boeve & Hutton, 2008), it is likely that different types of agraphia might be seen in these patients. For example, given that language and/or executive deficits related to frontal pathology are among the most prominent neuropsychological features of FTDP-17 (Bird et al., 1999; Lossos et al., 2003; Soliveri et al., 2003; Alberici et al., 2004; Boeve et al., 2005), it may be expected that aphasic and/or dysexecutive agraphia might be particularly frequently associated with this condition. In addition, parkinsonism, which occurs later in the course of disease may be related to ideomotor and limb-kinetic apraxia, leading to different forms of apraxic agraphia. Spatial agraphia in patients with FTDP-17 could be related to parkinsonism, which has been linked with severe visuospatial disorders, not only in case of Parkinson’s disease (Crucian and Okun, 2003), but also in atypical parkinsonism syndromes that can included in the FTLD spectrum, such as corticobasal degeneration (Hodges, 2007; Kertesz, 2008). What is more, writing impairment may be one of the early Parkinsonian signs (Kim et al., 2005; Ponsen et al., 2008), so it is of interest if writing impairment in FTDP-17 could be better explained within FTD spectrum or parkinsonian symptomatology.

Although the many forms of agraphia, briefly discussed above, may be associated with FTDP-17, to our knowledge, there are no prospective studies investigating agraphia in FTDP-17 and thus, to better learn the type of writing impairments associated with FTDP-17, we report the results of writing assessments performed on two pairs of siblings with FTDP-17 due to the P301L mutation in MAPT.

Methods

Participants

Four patients (two pairs of siblings with FTDP-17) were the participants of this study. The study was approved by IRB Committees of all participating institutions, and all patients provided informed consent to the genetic testing and clinical assessment. The examiners were blind to the patients’ genetic status during their initial evaluation.

Genetic analysis

Genetic study included sequencing of all coding and non-coding exons of GRN and exon 1, 7 and 9–13 of MAPT, as described previously (Baker., 2006). In all 4 participants sequencing analysis of MAPT and GRN identified the P301L mutation in MAPT.

Neuroimaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurements were performed on a 1,5 T scanner. Imaging slices of the brain were taken in the frontal, coronal and sagittal planes based on multiple MR sequences, including T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and fluid attenuated inversion recovery. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was performed 30 min after intravenous injection of 740MBq (20mCi) of 99mTc-ECD (FAM, ŁódŸ, Poland). Scanning was performed on a triple-head gamma-camera Multispect-3 (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a low-energy, ultrahigh resolution parallel-hole collimator. Regional cerebral blood flow was assessed semi-quantitatively on transverse slices using as reference region cerebellum.

Apparatus and Procedures: Neuropsychological Evaluation

Screening assessment

Global cognitive function was assessed using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein & McHugh, 1975), Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) (Mattis, 1988), Addenbrooke Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) (Mioshi, Dawson, Mitchell, Arnold & Hodges, 2006) and Blessed Dementia Rating Scale (BDRS) (Lezak, Howieson & Loring, 2004).

Memory

Working memory was assessed by using Digit Span (Brzezinski et al., 2004) and the Trail Making Test (TMT) Part A and B (Kadzielawa, Mroziak, Bolewska & Osiejuk, 1990). Verbal learning was measured by the 10-word or 15-word list of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) (Choynowski & Kostro, 1980) and/or the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) (Brandt, 1991). Whenever feasible the delayed copy of the Rey Complex Figure Test, served as a spatial memory measure (Rey, 1964). Semantic memory was tested using the Information subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) (Brzezinski et al., 2004).

Visuospatial functions

To measure visuospatial function Rey / Taylor Complex Figure Test (CFT) (Rey, 1964) and/or constructional praxis trials from Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive (ADAS – Cog) (Mohs, 1994) were used. The progression of unilateral neglect in Participant No. 1 was periodically assessed with the line bisection test (Schenkenberg, Bradford & Ajax, 1980), clock face drawing task from ACE-R, the letter cancellation test from Behavioural Inattention Test (Wilson, Cockburn & Halligan, 1987), Mesulam cancellation test (Weintraub & Mesulam, 1985) and experimental visual search task assessing visual search speed in four quadrants of a rectangular board devised by Wieczorek and Jodzio (see: Sitek et al., 2009).

Executive function and abstract thinking

Abstract thinking was investigated with the Similarities subtest of the WAIS-R. Executive functions were assessed with two phonemic (“K” – 60 sec. and “P”- 60 sec. or “P” and “W”) and two semantic fluency trials (animals – 60 sec. and plants or fruit and vegetables – 60 sec.), as well as the Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside (FAB) (Dubois, Slachevsky, Litvan & Pillon, 2000). Luria’s 3-step hand sequence-learning trials and Luria’s alternate drawn designs in motor programming assessment were also administered. Whenever feasible, depending on the severity of dementia and executive deficits, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (Jaworowska, 2002), Tower of Toronto task (Saint-Cyr, Taylor & Lang, 1988), Tower of London task (Culbertson & Zillmer, 2005) and Stroop test (1935) were also administered.

Language functions

Language functions were assessed using Boston Naming Test-short version (BNT) (Kaplan & Goodglass, 1983) as well as the elements of Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE) (Goodglass & Kaplan, 1983), speech comprehension was also assessed with Token Test (De Renzi & Vignolo, 1962).

Writing

Writing assessment was performed in all cases with the sentence writing task derived from the MMSE. All 4 patients, whenever feasible, were examined with the writing trials from BDAE including : primer-level dictation, writing to dictation, writting the names of visually presented items (written confrontation naming) and copying a sentence. A written description of a picture from Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test (FAST) (Enderby & Crow, 1986) was administered without time limits. To test for spatial agraphia Participants No. 1 (with the unilateral neglect syndrome), and in No. 4 (for screening purposes) attempted to write text from the Functional Neglect Assessment Battery (Wieczorek & Jodzio, 2002) was administered to test for spatial agraphia.

Summary of the clinical characteristics and the results of cognitive and language assessment

Patient No. 1

Participant No. 1 is a right-handed man employed as an electrical technician in whom developed apathy about the age of 49. One year later his speech became impoverished and his personality grew more introverted. He then developed psychomotor slowing and depression with a suicidal ideation, so he required admission to a psychiatry inpatient ward. Subsequently, hyperphagia and indifference emerged. Parkinsonian signs started at the age of 55, with left-sided resting tremor and hypomimia, but initially he had a good response to levodopa treatment. At the age of 56, he developed autonomic dysfunction (e.g., urinary incontinence). Examination at this time revealed vertical nystagmus and a positive glabellar tap reflex. He then developed compulsive behaviors, a decline in hygiene as well as problems with dressing. At the age of 58, he became disinhibited and mildly amnesic. One year later, he experienced several epileptic seizures. His parkinsonism progressed with bradykinesia, rigidity and postural instability, accompanied by dysphagia. At the age of 61, the patient was bedridden and mute. He died at the age of 61 years, 11 months. The neuroimaging data of this and other participants has been presented in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Also, the results of each neuropsychological examination of this patient have been presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 2.

The summary of agraphia pattern and neuroimaging data in all patients

| Case no. 1 | Case no.2 | Case no. 3 | Case no. 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Agraphia | ||||

| - aphasic | + | + | + | + (?) |

| - dysexecutive | + | + | + | + |

| - spatial | + | − | − | − |

| - apraxic / allographic | + | + | − | − |

|

| ||||

| age at the neuroimaging (time since onset) years | 58 (9) | 57 (6) | 52 (8) | 50 (1) |

|

| ||||

| MRI | ||||

| - generalized cortical atrophy | + | + | + | − |

| - predominant atrophy pattern frontal (F) / temporal (T) / parietal (P) | T | F & T | F | P |

| - asymmetry: right (R) or left( L) | + (R) | − | + (L) | − |

|

| ||||

| SPECT | ||||

| - generalized hypoperfusion | − | + | + | + |

| - anterior hypoperfusion profile | + | + | + | + |

| - predominant hypoperfusion pattern frontal (F) / temporal (T) / parietal (P) | F & T | F | F | F |

| - asymmetry: right (R) or left( L) | + (R) | + (R) | + (L) | + (L) |

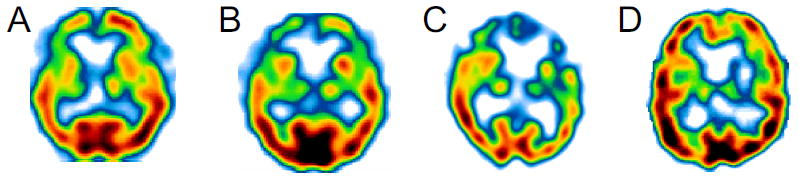

Figure 1.

Frontotemporal hypoperfusion on SPECT is present in all cases: A) Participant No. 1, B) Participant No. 2, C) Partcipant No. 3, D) Participant No. 4

Table 3.

Writing assessment in the context of global cognitive and language function

| Pair of siblings | I | II | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Patient no. 1 | Patient no. 2 | Patient no.3 | Patient no.4 | |||||||||

| Age (years/ months) | 58/5 | 58/11 | 59/6 | 60/1 | 60/11 | 57/2 | 57/9 | 50/0 | 52/0 | 53/2 | 48/0 | 49/11 | 51/0 |

| Time since onset (years) | 9 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| MMSE (max. 30) | 24 | 21 | 20 | 11 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 30 | 29 | 29 |

| Naming | |||||||||||||

| BNT-short version (max. 15) or full version (max. 60) | 13 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0 | NA | 5 | 0 | NA | 57/60 | 58/60 |

| Naming (20 pictures) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17 | NA | NA | 20 | NA | NA |

| BDAE-Confrontation naming (max. 105 points) | 101 | 95 | 94 | NA | NA | 93 | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| BDAE-Responsive naming (max. 30 points) | 29 | 30 | 30 | 19 | 2 | 20 | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Comprehension | |||||||||||||

| BDAE-Word discrimination (max. 72 points) | 70.5 | 70.5 | 69 | NA | NA | 64 | DD | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| BDAE-Commands (max. 15 points) | 13 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 0 | NA | 5 | 3 | NA | 15 | 15 |

| Token test-shortened version (max. 163 points) vs part V (max. 22 points) | 16 / 22 | 15 / 22 | 153 / 163 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 163/163 | 163/163 |

| Repetition | |||||||||||||

| BDAE-Sentence repetition high / low frequency (max. 8/8 points) | 8 / 8 | 8 / 8 | 8 / 8 | 7 / 8 | 5 / 5 | 8 / 6 | 4 / 3 | NA | 2 / 2 | 0 / 0 | NA | 7 / 8 | 7 / 8 |

| Reading | |||||||||||||

| BDAE-Reading words (max. 30 points) | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 27 | 30 | 30 | NA | 30 | 27 | NA | NA | 30 |

| BDAE-Reading sentences (max. 10 points) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 9 | NA | 5 | 2 | NA | NA | 10 |

| BDAE-Reading paragraphs (max.10 points) | 10 | 9 | 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Writing | |||||||||||||

| Signature preserved (yes / no) | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | ? | ? | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes |

| BDAE-Primer level dictation (max. 15) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 14 | 4 | NA | 0 | 1 | NA | 15 | 15 |

| BDAE-Writing to dictation (max.10) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 10 | - | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 10 | 10 |

| BDAE-Written confrontation naming (max.10) | 9 | 10 | 8 | 4 | NA* | 4 | - | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 10 | 10 |

BDAE, Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; BNT, Boston Naming Test; DD, discontinued; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NA, not available

Table 4.

Neuropsychological assessment of the Patient No. 1

| Age at examination, years/months (years since onset)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57/10 (8) | 58/5 (9) | 59/0 (9) | 59/6 (10) | 60/1 (11) | 60/11 (11) | |

|

| ||||||

| Global measures | ||||||

| MMSE (max. 30 p.) | 28 | 24 | 21 | 20 | 11 | 5 |

| BDRS (max. 28 p.) | 6 | 11 | 17 | 16.5 | 20 | 25 |

| ACE-R global score (max.100 points) | NA | 82 | 71 | 51 | NA | NA |

| ACE-R attention and orientation (max.18 p.) | NA | 18 | 17 | 12 | NA | NA |

| ACE-R memory (max.26 p.) | NA | 20 | 19 | 14 | NA | NA |

| ACE-R verbal fluency (max. 14 p.) | NA | 5 | 3 | 2 | NA | NA |

| ACE-R language function (max.26 p.) | NA | 24 | 19 | 15 | NA | NA |

| ACE-R visuospatial function (max.16 p.) | NA | 15 | 13 | 8 | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||

| Executive function | ||||||

| WCST - Categories attained (max. 6) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| FAB (max. 18 points) | NA | NA | 4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Stroop test (interference: % of errors) | NA | 17% | 54% | NA | NA | NA |

| Luria’a alternate design (% of errors) | NA | 30% | 91% | NA | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||

| Attention and memory | ||||||

| Digit Span forward (WAIS-R) - max. span | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | NA | 3 |

| Digit Span backward (WAIS-R) - max. span | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | NA | NA |

| TMT A (T-score) | 59 | 65 | >100 | >100 | NA | NA |

| TMT B (T-score) | 67 | 86 | >100 | NA 1 | NA | NA |

| TMT B-A (T-score) | 8 | 21 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| TMT B (errors) | 2 | 2 | 12 | NA | NA | NA |

| AVLT-learning curve | 5-8-10-9-12 | 4-5-7-9-9 | 4-5-7-8-7 | 5-5-4-6-6 | NA | NA |

| AVLT-recognition | 12 | 8 | 3 | 0 | NA | NA |

| AVLT-delayed recall | 10 | 10 | 6 | 0 | NA | NA |

| AVLT-retention (%) | 83 | 90 | 75 | 0 | NA | NA |

| AVLT-sum of intrusions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| AVLT-delayed recognition (false positives) | 13 (3) | 15 (11) | 14 (29) | 15 (30) | NA | NA |

| HVLT-learning curve | NA | 4-6-8 | 3-3-3 | 3-5-6 | NA | NA |

| HVLT-delayed recall | NA | 6 | 3 | 0 | NA | NA |

| HVLT-delayed recognition | NA | 2 | 0 | 2 | NA | NA |

| HVLT-retention (%) | NA | 75 | 100 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Rey/ Taylor CFT-after 3 min. (%) | NA | 96 | 95 | 44 | NA | NA |

| Information (WAIS-R) - Scaled Score | 10 | NA | 11 | NA | 3 | NA |

|

| ||||||

| Visuospatial functioning | ||||||

| CFT-Rey/Taylor-copy (raw score) | 33 | 28.5 | 30 | 26 | 16 | NA |

| Line bisection (average deviation in mm | NA | 6.77 | 5.03 | 5.62 | 17.8 | NA |

| Mesulam cancellation test (max. 30; left/right) | NA | NA | 26/28 | 0/9 | 0/6 | NA |

| BIT- letter cancellation: omissions from the left to the right | NA | 1-1-1-0 | 3-4-4-5 | 10-6-3-4 | 10-10-10-6 | NA |

| VST-Upper left / right quadrant: time in seconds | NA | 42/18 | 25/12 | 136/10 | NA | NA |

| VST-Lower left / right quadrant: time in seconds | NA | 16/9 | 13/13 | 23/19 | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||

| Verbal fluency | ||||||

| Semantic fluency trials (animals, plants) | 19 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Phonemic fluency trials ( K”, P”) | 9 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

ACE-R, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination - Revised; AVLT, Auditory Verbal Learning Test; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BIT, Behavioural Inattention Test; BDRS, Blessed Dementia Rating Scale; CFT, Complex Figure Test; FA, false alarms; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; HVLT, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NA, not available; p, points; TMT, Trail Making Test; VST, Visual Search Task, WAIS-R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test;

after poor execution of an example TMT B, the test was discontinued

This patient was assessed six times, at approximately 6-month intervals. On the first examination the patient demonstrated marked working memory, verbal fluency, and set-shifting impairments. This patient also exhibited echopraxia and could not perform Luria’s hand sequencing. On this first examination the patient was asked to write only as part of the MMSE. At that time he was able to differentiate between lower and upper script, but the letters were for the most part disconnected from each other (see: Figure 2).

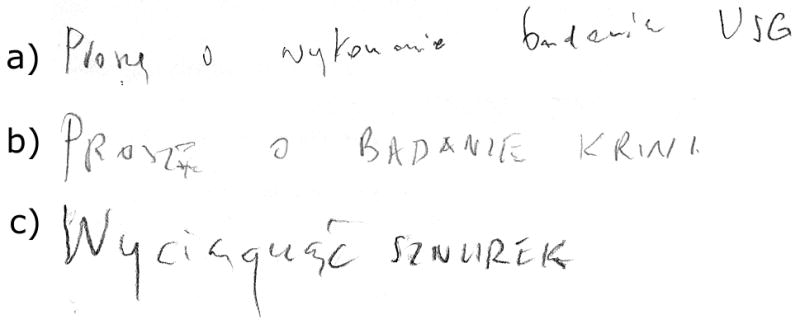

Figure 2.

Writing sentence from MMSE by patient no. 1 at three testing sessions: a) 57,2 years old, b) 58,5 years old, c) 58,11 years old

On the next examination, his working memory and verbal fluency problems progressed. Also, verbal learning, planning and cognitive control, naming and speech comprehension were deficient. At that time allographic and dysexecutive agraphia were present (see: Table 4). He was then diagnosed with left unilateral neglect, more pronounced in personal than extrapersonal space, and likely contributing to his spatial agraphia presenting as neglect dysgraphia (see: Figure 3).

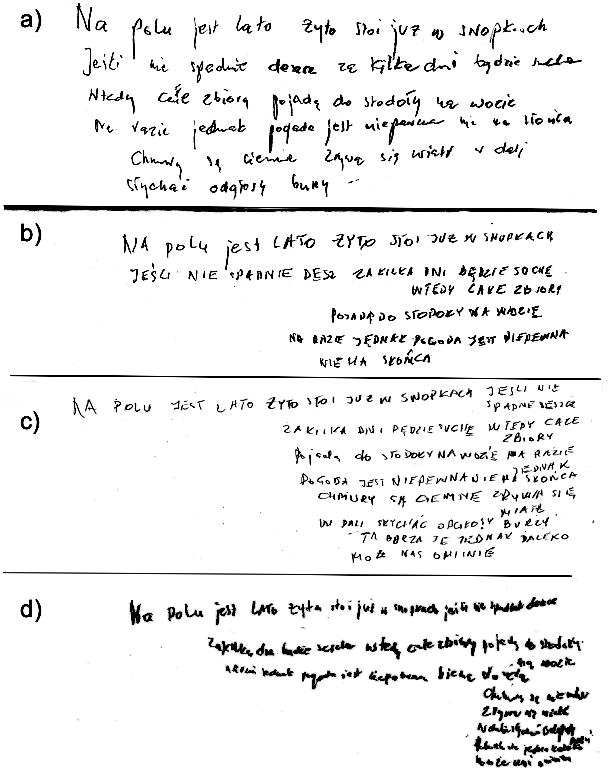

Figure 3.

Progression of unilateral neglect in patient no. 1: a) 58,5 years old, b) 58,11 years old, c) 59, 6 years old

The third examination conducted 5 months later revealed further cognitive deterioration in all tested domains. At that time, when writing he had impaired access to his allographic store of letters, agrammatism and perseverative tendencies (see: Figure 4). The description of the picture from FAST was as follows: “THE BOY IS ROWING A BOAT. THE BOY IS ROWING A CANOE. THE BOYS ARE FEEDING DUCKS. THE SAILING BOAT IS ANCHORED. THE MAN IS WALKING WITH A DOG.”.

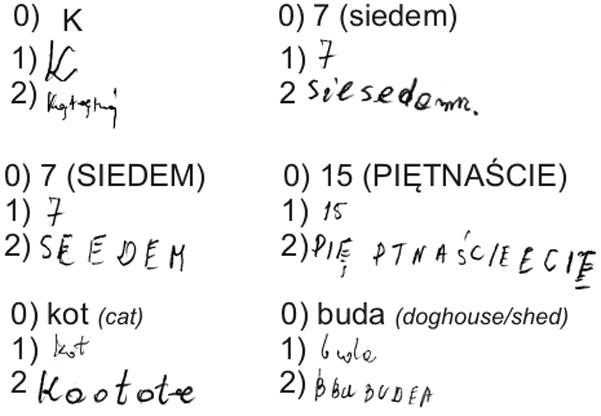

Figure 4.

Progression of agraphia in writing words to dictation in patient no. 2: 0) expected performance (in case of words translation was added) 1) performance when 57,2 years old, b) performance when 57,9 years old

The patient’s general cognitive status remained stable over the next 6 months, except for a dramatic deterioration of verbal and visual memory, as revealed during the 4th examination. Further, hemispatial neglect became evident in paper and pencil tests. There was also an increase of his agrammatism in writing; e.g., while describing a picture from the FAST he wrote: “THE MAN IS LEADING A DOG. THE BOY IS ROWING A BOAT. TWO BOYS BY THE BRIDGE….DUCKS BY THE BRIDGE”.

On the 5th examination, this patient’s attentional and executive deficits further progressed. Since the patient could not understand complex instructions the verbal learning trials could not be administered. The patient managed to correctly copy several elements of Rey CFT, suggesting severe problems with planning. At that time, this patient was also committing severe spelling errors while writing to dictation (e.g. “kok”[bun] instead of “kot” [cat], “puda”[neologism] instead of “buda” [doghouse], “terar” [neologism] instead of “teatr” [theatre]). Written confrontation naming and written picture description (from FAST), similarly to oral confrontation naming, were severely impaired. This patient often reverted to copying pictures instead of writing, suggesting progression of a dysexecutive agraphia. The patient managed to write only one short sentence in FAST; however it was grammatically incorrect. From 3rd to 5th examination spatial agraphia was progressing quite rapidly, with additional evidence of micrographia (see: Figure 3).

During 6th examination, the patient presented with markedly delayed response to various stimuli and echolalia emerged. He managed to copy only a circle and a diamond from ADAS-Cog Constructional praxis task. Eventually, the patient was able to write only a couple of short words with simple phonological structure. When attempting to write longer words he had problems with producing correct letter shapes, a sign of apraxic agraphia as well as progression of his allographic agraphia such that he could write only using capital letters. He could not even produce his signature to command.

Patient No. 2

This right-handed saleswoman was admitted to a neurology in-patient service at the age of 57 due to progressive dementia and gait impairment. She was neurologically and psychiatrically intact until the age of 51. Since then, progressive behavioral disturbances, such as disinhibition, compulsive behaviors, and apathy, were noticed by the family. At the age of 52, she started stealing products from the shop where she was employed, gathering useless things and borrowing money without need. At the age of 56, she developed the symptoms and signs of parkinsonism including bradykinesia and left-sided cogwheel rigidity, which responded to levodopa treatment. She also had gait disturbances, and autonomic dysfunction. At the age of 57 she experienced epileptic seizures, as well as visual hallucinations. Later, utilization behavior became a prominent sign.

The results of all three neuropsychological examinations are presented in Tables 3 and 5. Results from the first examination were collected retrospectively from the medical charts.

Table 5.

Neuropsychological assessment of the Patient No. 2

| Age: years, months (years since onset)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 56/4 (5) | 57/2 (6) | 57/10 (6) | |

|

| |||

| Global measures | |||

| MMSE (max.30 points) | 22 | 14 | 4 |

| BDRS (max. 28 points) | 6 | 20 | 21 |

| ACE-R (max.100 points) | NA | 33 | 11 |

| ACE-R attention and orientation (max.18 points) | NA | 6 | 3 |

| ACE-R memory (max.26 points) | NA | 5 | 0 |

| ACE-R verbal fluency (max. 14 points) | NA | 0 | 0 |

| ACE-R language function (max. 26 points ) | NA | 13 | 6 |

| ACE-R visuospatial function (max.16 points) | NA | 9 | 2 |

| DRS | NA | 62 | NA |

|

| |||

| Attention and memory | |||

| Digit Span forward from WAIS-R- max. span | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Digit Span backward from WAIS-R- max. span | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| AVLT-learning curve | 3-4-7-8-8 | 1-3-4-4-5 | NA |

| AVLT-delayed recall | 5 | 0 | NA |

| AVLT-retention (%) | 63 | 0 | NA |

| AVLT-sum of intrusions | 5 | 2 | NA |

| HVLT - learning curve | NA | 5-5-5 | 1-1-0 |

| HVLT- delayed recall | NA | 2 | 0 |

| HVLT-retention (%) | NA | 40 | 0 |

| HVLT- delayed recognition | NA | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Semantic memory | |||

| Information from WAIS-R (raw score) | 6 | 2 | NA |

|

| |||

| Abstract thinking | |||

| Similarities from WAIS-R (raw score) | 0 | 0 | NA |

|

| |||

| Verbal fluency | |||

| semantic fluency trials (animals, plants-summed) | NA | 2 | 0 |

| phonemic fluency trials ( K”, P”- summed) | NA | 2 | 0 |

ACE-R, Addenbrooke Cognitive Examination- Revised; AVLT, Auditory Verbal Learning Test; BDRS, Blessed Dementia Rating Scale; BDAE, Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; BNT, Boston Naming Test; HVLT, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NA, not available

At the 2nd assessment, there was a global deterioration of cognitive functions. The patient exhibited limited spontaneous speech output, moderate anomia, and impaired speech comprehension. When asked to perform any task, instead of following the command, she tended to write down the given instructions. At that time, her echolalia was also severe. She also had problems in written confrontation naming from BDAE. She could not write the words that denote numbers to command which was may have been due to impaired set-shifting. She also committed various semantic paragraphic errors, as she wrote words unrelated to pictures (“ołówek”[pencil] instead of “klucz”[key], “drugie” [the second] instead of “koło” [circle], “trzydzieści sókow” [thirty (cartons of) juice] instead of “kwadrat” [square] and these errors were probably related to an impairment in lexical retrieval.

On the 3rd examination the patient was severely demented with predominant executive and language dysfunction. Only oral reading was preserved. Writing assessment showed severe problems in writing letters and short words (see: Figure 4). She demonstrated both perseverative and spelling errors, evidencing features of dysexecutive and aphasic agraphia. Similar perseverative tendencies were seen in drawing tasks. In this participant there were neither problems with spatial organization of the text nor a disorder of case selection.

Patient No. 3

This patient was a left-handed artist (painter) with probable developmental dyslexia and dysgraphia. Personality changes were his first symptom, noted at the age of 44/45. Those changes were initially attributed to artistic nonchalance and as a reaction to marital problems; however, at the age of 48 his behavioral and cognitive impairments became evident. His paintings became poorly structured and then he stopped painting as he no longer had creative inspirations. He lost interest in his family, demonstrated hyperphagia with stereotypical and compulsive behaviors (gathering old newspapers, repeatedly walking the same route, persistent charging his mobile phone). His self-grooming and hygiene also deteriorated.

He was referred for evaluation because of his occupational problems, apathy, lack of care about appearance and impoverished spontaneous speech. The patient himself appeared unconcerned about his cognitive or behavioral problems.

Neurological examination at the age of 50 did not reveal any abnormalities. At the age of 52, spontaneous speech was very impoverished. Occasionally, even his responses to yes/no questions were inappropriate. When he misunderstood the questions, he frequently gave echolalic responses. He had bilateral frontal release signs, motor perseveration, echolalia, but no signs of parkinsonism.

During his first neuropsychological assessment, the patient had evidence of dementia, with pronounced executive and language impairments (see: Table 3 & Table 6).

Table 6.

Neuropsychological assessment results in Patients no. 3 and no. 4

| Patient no. 3 | Patient no. 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age: years/ months (years since onset) | 50/0 (6) | 52/0 (8) | 53/2 (9) | 48/0 (0) | 49/11 (1) | 51/0 (2) |

|

| ||||||

| Global measures | ||||||

| MMSE (max. 30 points) | 16 | 4 | 1 | 30 | 29 | 29 |

| BDRS (max. 28 points) | NA | 9.5 | 18 | NA | 0 | 0 |

| ACE-R global score (max.100 points) | NA | 22 | NA | NA | NA | |

|

| ||||||

| Executive function | ||||||

| WCST - Categories attained (max. 6) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 | NA |

| FAB (max. 18 points) | 3 | 1 | NA | 18 | 18 | 17 |

| Stroop test (interference:% of errors) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.02 | 2.04 |

| Luria’a alternate design (% of errors) | 0 | DD | DD | NA | 3 | NA |

| Similarities from WAIS-R (Scaled Score) | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 13 | 14 |

|

| ||||||

| Attention and memory | ||||||

| Digit Span forward - max. span | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Digit Span backward - max. span | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Block span forward- max. span | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6 | 6 |

| Block span backward- max. span | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 5 |

| BVRT-version F (max. 15) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 13 | 15 |

| TMT A (T-score) | DD | DD | NA | 40 | 47 | 42 |

| TMT B (T-score) | NA | NA | NA | 65 | 48 | 48 |

| TMT B-A (T-score) | NA | NA | NA | 25 | 1 | 6 |

| TMT B (errors) | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 10 word-list learning | 3,4,4,5,5,6,5,6 | NA | NA | 4,5,9,9,10,10,10 | NA | NA |

| 10 word-delayed recall | 3 | NA | NA | 9 | NA | NA |

| 10 word-delayed recognition | 8 | NA | NA | 10 | NA | NA |

| AVLT-learning curve | NA | NA | NA | NA | 6,10,13,14,15 | 7,12,12,14,15 |

| AVLT-recognition | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 15 |

| AVLT-delayed recall | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 14 |

| AVLT-retention (%) | 50% | NA | NA | NA | 100% | 93% |

| AVLT-sum of intrusions | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 0 |

| AVLT-delayed recognition | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 |

| Rey/ Taylor CFT-after delay (%) | 125 | 105 | NA | 49 | 97 | 94 |

| Information (WAIS-R) - Scaled Score | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14 | 14 |

|

| ||||||

| Visuospatial functioning | ||||||

| CFT-Rey/Taylor-copy (raw score) | 16 | 9.5 | 2 | 35 | 33 | 36 |

|

| ||||||

| Verbal fluency | ||||||

| semantic fluency trials (animals, plants/ fruit and vegetables) | 11 | 1 | NA | 33 | 48 | 49 |

| phonemic fluency trials ( K”, P”) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 17 | 21 |

| (“P”, “W”) | 2 | NA | NA | 13 | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||

| Planning | ||||||

| Tower of London-total move score, SS | NA | NA | NA | 112 | NA | 122 |

| Tower of Toronto- total score | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11 | 14 |

ACE-R, Addenbrooke Cognitive Examination-Revised; AVLT, Auditory Verbal Learning Test; BDRS, Blessed Dementia Rating Scale; BVRT, Benton Visual Retention Test; CFT, Complex Figure Test; DD, discontinued; FAB, Frontal Assessment Battery; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NA, not available; SS, standardized score, TMT, Trail Making Test; WAIS-R, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

During the first evaluation an assessment of his writing ability was made during MMSE administration and this patient had difficulty understanding the instructions. Further guidance did not help and the patient actually copied his name and surname from the envelope containing his medical records. Further encouragement to write anything else resulted in words “choroba Parkinson” (an agrammatical form of Parkinson’s disease). During the first neuropsychological examination a larger writing sample was not obtained.

The 2nd examination revealed global deterioration of his cognitive functions, especially in terms of language and executive domains (see: Table 3 and 6). At that time, the patient was approached with writing tasks on three occasions. Each time the patient tended to write only his surname. Even when asked to write the letter “K” which is the first letter of his name, he continued with writing his surname. When asked to provide a written description of a picture from the FAST he simply re-drew some parts of the picture. He was unable to copy a short sentence and committed severe aphasic errors.

The 3rd examination showed further cognitive decline. He failed to perform in response to commands or answer questions. His spontaneous speech lacked informative content. He also perseverated while drawing. The patient was unable to write his signature to command. When asked to write letters to dictation after writing the correct letter (“B”) he produced the whole array of letters (BANANNANABBAMAMAMA…). Even copying a sentence from BDAE led to generating a perseverative non-word string of letters (CAAAMMMBMMMM). His severe agraphia was consistent with his aphasia and dysexecutive symptoms.

Patient No. 4

Patient No. 4, was a right-handed restorer of antique furniture. He was assessed for the first time at the age of 48, due to his brother being diagnosed with dementia. His wife, however, reported no cognitive or behavioral changes. Neurological examination was also normal but neuropsychological evaluation identified subtle abnormalities. One year later, he became depressed. The patient was still occupationally successful. Neurological examination did reveal a reduced swing of his right upper limb when walking, but both the patient and his wife still denied any cognitive or behavioral alterations.

The patient’s first neuropsychological evaluation revealed only subtle attention deficits and reduced letter-phonemic fluency (see: Table 3 and 6). Writing was only assessed as a part of the MMSE where he wrote a sentence that was grammatically correct.

On the 2nd evaluation, his cognitive profile remained stable. His speech output was slightly impoverished as was his writing, with only brief utterances. The patient’s speech seemed rather aprosodic. While performing a written description of a picture, this patient used very simple grammatical structures, with only one spelling error (“oboko” instead of “obok”-meaning nearby). According to the results of his neuropsychological testing, his writing impairment seems to best classified as mild dysexecutive agraphia, although the spelling errors may also suggest aphasic agraphia.

During his 3rd examination no deterioration was observed. Writing seemed almost intact with no aphasic errors and better organization than during his 2nd assessment when the patient was providing a description of a picture.

Some of the clinical and neuromaging data of participants No. 1, No. 2 and No. 4 were previously reported by Narożańska et al. (2011), Sitek et al. (2010, 2011, 2012). The summary of the agraphia profiles in and neuroradiological findings of all the 4 participants is presented in Table 2.

Discussion

This series of patients suggest that dysexecutive agraphia may appear early in the course of FTDP-17. Aphasic and allographic agraphia seem to develop later. In FTDP-17, spatial agraphia, if present, is presumably related to the unilateral neglect syndrome as well as the right-sided brain pathology, whereas aphasic agraphia is associated with an asymmetrical atrophy and/or hypoperfusion of the left hemisphere.

Agraphia in FTLD was previously described in terms of aphasic agraphia in primary progressive aphasia (Neil & Duffy, 2001), surface dysgraphia in semantic dementia (Garrard & Hodges, 2000), and allographic agraphia (Menichelli et al., 2008) in an unspecified FTLD variant. Aphasic errors in writing were reported also in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Ichikawa et al., 2008). However, most descriptions of writing dysfunction in the context of neurodegenerative disorders have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease (Neil-Strunjas, Shuren, Roeltgen & Brown, 1998; Glosser, Kohn, Sands, Grugan & Friedman, 1999; Luzzatti et al., 2003). These reports appear to indicate that writing impairments are often more closely related to general cognitive or executive dysfunctions than to language dysfunction. This observation is also partially supported by the results from current study. In all our three advanced cases with FTDP-17 (participants No.1, No.2 and No. 3), writing impairment progressed over time with the profile of errors indicating a close relationship with their cognitive dysfunction. Especially, the long observation period of participant No. 1 appears to indicate that the agraphia associated with FTLD might be more closely related to executive, spatial and praxic dysfunction than to aphasia. In this patient the aphasic errors in writing appeared very late in the course of his disease. The deficits are consistent with the findings on brain imaging which demonstrated right-hemispheric predominance of abnormalities (in contrast to participant No. 3 with aphasia and left-sided atrophy).

The profile of the progressive language impairments in participants No. 1, No. 2 and No. 4 suggest that receptive language functions elicited by external stimuli (comprehension, repetition, reading aloud) are better preserved than those that have to be initiated and organized by these patients such as spontaneous speech. Although initially the decreased productivity was observed only in speech it subsequently involved writing. This decrease of writing productivity was parallel to other frontal mediated cognitive activities and these behavioral decrements were associated with frontal abnormalities on imaging, with frontal atrophy in participants No. 1, No. 2 and No. 3 and frontal hypoperfusion in participant No. 4. This impoverished output with perseverative errors in writing accompanied by executive dysfunction (e.g., impaired planning, organization, and set shifting) consistently observed in these participants, provides further support for the concept of dysexecutive agraphia (Ardila & Surloff, 2006). In participants No. 1 and No. 4, dysexecutive agraphia was present early in the course of the disease, suggesting it can be among the first symptoms of cognitive decline in individuals with FTDP-17. Thus, dysexecutive agraphia may be another potential marker for FTDP-17, apart from the previously reported poor verbal (phonemic) fluency, speech and smell deterioration (Geschwind et al., 2001; Ferman et al., 2003; Alberici et al., 2004; Arvanitakis et al., 2007; Liss et al., 2006). Additionally, as demonstrated by participant No. 2, a progressive spatial agraphia (neglect dysgraphia), associated with unilateral neglect might be sometimes also present in subjects with FTDP-17, especially those with more pronounced right-sided atrophy and/or hypoperfusion.

Some of patients with FTDP-17, such as patient No. 1 and No. 2, may also present with features of apraxic agraphia characterized by a loss of the knowledge about the movements needed to write letters. This apraxic agraphia even impaired their ability to sign their name. Allographic agraphia, characterized by the improper use of upper and lower case letters, as well as a tendency to write in block letters, was also noted.

An anomia, present in the speech of participants No. 1, No. 2 and No. 3 was also observed in their writing. The spelling errors observed in participants No. 1, No. 2, and No. 4 are suggestive of aphasic agraphia. Aphasic agraphia, however, only predominated in participant No. 3, who presented with the most severe aphasic speech disturbance accompanied by marked frontal hypoperfusion, that was more pronounced on the left.

Heilman et al. (2008) suggested that the initial symptom of corticobasal degeneration might be an asymmetrical apraxic agraphia. Fukui and Lee (2008) suggested that progressive agraphia could be an early symptom of dementia. Bird et al. (1999) reported one FTDP-17 subject with writing impairment that was among one of the first symptoms, as was in the case of participant No. 4 who also exhibited dysexecutive agraphia very early in his disease. The results obtained from participant No. 4 seem to be in line with the suggestions by Ardila and Surloff (2006), who claimed that the assessment of spontaneous writing may be valuable in the early detection of a degenerative disease.

Our study has several limitations. Apart from participant No. 4 these patients with FTDP-17 who we report were more advanced and cognitively impaired than those described by others (Boeve et al., 2005). Also, these participants’ writing abilities were not all assessed using the same strategies and not all tests of writing were used in all the participants. In addition, due to progressive cognitive deterioration, not all the neurocognitive and imaging measures could be repeated over time. Therefore, future research is needed to verify the profile of agraphia in FTDP-17 in larger samples, starting at the earlier stages of the disease and with longer follow-up.

Conclusions

Agraphia in FTDP-17 is a heterogenous phenomenon: dysexecutive, aphasic, spatial, allographic and apraxic. Further studies should examine the usefulness of narrative writing as an early indicator of the cognitive (especially executive) dysfunction in frontal/behavioral variant of FTD.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank patients and all family members for their participation and interest in our study. EJS was supported by the START Scholarship awarded by the Foundation for the Polish Science. Both EJS and MH received a scholarship from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education. BJM was supported by the Robert and Clarice Smith Fellowship Program, Mayo Clinic Florida, the Medical University of Silesia, Poland, and the Polish Foundation for Development of Neurology, Degenerative and Cerebrovascular Diseases. ZKW was supported by a Morris K. Udall NIH/NINDS Parkinson’s Disease Research Center of Excellence (P50NS072187), NIH/NINDS (1RC2NS070276 and NS057567), and Mayo Clinic Florida CR Program (MCF 90052018 and MCF 90052030) grants and by Carl Edward Bolch, Jr. and Susan Bass Bolch Gift Fund. RR was supported by the National Institute of Health (grant # NS65782).

References

- Alberici A, Gobbo C, Panzacchi A, Nicosia F, Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Hock C, Papassotiropoulos A, Lieberini P, Growdon JH, Frisoni GB, Villa A, Zanetti O, Cappa S, Fazio F, Binetti G. Frontotemporal dementia: impact of P301L tau mutation on a healthy carrier. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2004;75:1607–1610. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.021295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardila A, Surloff C. Dysexecutive agraphia: a major executive dysfunction sign. The International Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;116:653–663. doi: 10.1080/00207450600592206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z, Witte RJ, Dickson DW, Tsuboi Y, Uitti RJ, Slowinski J, Hutton ML, Lin SC, Boeve BF, Cheshire WP, Pooley RA, Liss JM, Caviness JN, Strogosky AJ, Wszolek ZK. Clinical-pathologic study of biomarkers in FTDP-17 (PPND family with N279K tau mutation) Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2007;13:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Mackenzie IR, Pickering-Brown SM, Gass J, Rademakers R, Lindholm C, Snowden J, Adamson J, Dessa Sadovnick A, Rollinson S, Cannon A, Dwosh E, Neary D, Melquist S, Richardson A, Dickson D, Berger Z, Eriksen J, Robinson T, Zehr C, Dickey CA, Crook R, McGowan E, Mann D, Boeve B, Feldman H, Hutton M. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–919. doi: 10.1038/nature05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird TD, Nochlin D, Poorkaj P, Cherrier M, Kaye J, Payami H, Peskind E, Lampe TH, Nemens E, Boyer PJ, Schellenberg GD. A clinical pathological comparison of three families with frontotemporal dementia and identical mutations in the tau gene (P301L) Brain. 1999;122:741–756. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeve BF, Hutton M. Refining frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: introducing FTDP-17 (MAPT) and FTDP-17 (PGRN) Archives of Neurology. 2008;65:460–464. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.4.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeve BF, Tremont-Lukats IW, Waclawik AJ, Murrell JR, Hermann B, Jack CR, Shiung MM, Smith GE, Nair AR, Lindor N, Koppikar V, Ghetti B. Longitudinal characterization of two siblings with frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 associated with the S305N tau mutation. Brain. 2005;128:752–772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: Development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1991;5:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziński J, Gaul M, Hornowska E, Jaworowska A, Machowski A, Zakrzewska M. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Renormalization. WAIS-R(PL)–Manual. Warsaw: Laboratory of Psychological Tests; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Choynowski M, Kostro B. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test. Warsaw: PWN Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LN, Poorkaj P, Wszolek ZK, Geschwind DH, Nasreddine ZS, Miller B, Li D, Payami H, Awert F, Markopoulou K, Andreadis A, D’Souza I, Lee W, Reed L, Trojanowski J, Zhukareva V, Bird T, Schellenberg G, Wilhelmsen KC. Pathogenic implications of mutations in the tau gene in pallido-ponto-nigral degeneration and related neurodegenerative disorders linked to chromosome 17. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:13103–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crucian GP, Okun MS. Visual-spatial ability in Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 2003;8:992–997. doi: 10.2741/1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson CW, Zillmer EA. Tower of London Drexel University (TOL DX) New York: Multi-Health Systems Inc. (MHS); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Renzi E, Vignolo LA. The token test: A sensitive test to detect receptive disturbances in aphasics. Brain. 1962;85:665–678. doi: 10.1093/brain/85.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55:1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enderby P, Crow E. Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test: validity and comparability. Disability and Rehabilitation. 1996;18:238–240. doi: 10.3109/09638289609166307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferman TJ, McRae CA, Arvanitakis Z, Tsuboi Y, Vo A, Wszolek ZK. Early and pre-symptomatic neuropsychological dysfunction in the PPND family with the N279K tau mutation. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2003;9:265–270. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(02)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster NL, Wilhelmsen K, Sima AA, Jones MZ, D’Amato CJ, Gilman S. Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: a consensus conference. Annals of Neurology. 1997;41:706–715. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui T, Lee E. Progressive agraphia can be a harbinger of degenerative dementia. Brain and Language. 2008;104:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard P, Hodges JR. Semantic dementia: clinical, radiological and pathological perspectives. Journal of Neurology. 2000;247:409–422. doi: 10.1007/s004150070169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind DH, Robidoux J, Alarcón M, Miller BL, Wilhelmsen KC, Cummings JL, Nasreddine ZS. Dementia and neurodevelopmental predisposition: cognitive dysfunction in presymptomatic subjects precedes dementia by decades in frontotemporal dementia. Annals of Neurology. 2001;50:741–746. doi: 10.1002/ana.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glosser G, Kohn SE, Sands L, Grugan PK, Friedman RB. Impaired spelling in Alzheimer’s disease: a linguistic deficit? Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:807–815. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman KM, Coenen A, Kluger B. Progressive asymmetric apraxic agraphia. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 2008;21:14–7. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e318165b133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges JR. Overview of frontotemporal dementia. In: Hodges JR, editor. Frontotemporal dementia syndromes. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M. Missense and splice site mutations in tau associated with FTDP-17: multiple pathogenic mechanisms. Neurology. 2001;56:S21–25. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.suppl_4.s21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa H, Koyama S, Ohno H, Ishihara K, Nagumo K, Kawamura M. Writing errors and anosognosia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with dementia. Behavioural neurology. 2008;19:107–116. doi: 10.1155/2008/814846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworowska A. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)–Manual. Warsaw: Laboratory of Psychological Tests; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kądzielawa D, Mroziak J, Bolewska A, Osiejuk E. Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Battery. Manual. Warsaw: Psychological Test Laboratory of the Polish Psychological Association; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H. Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE) Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. Frontotemporal dementia: a topical review. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 2008;21:127–133. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31818a8c66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Lee BH, Park KC, Lee WY, Na DL. Micrographia on free writing versus copying tasks in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2005;11:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama K, Okada S, Iseki E, Kowalska A, Tabira T, Hosoi N, Yamanouchi N, Noda S, Komatsu N, Nakazato M, Kumakiri C, Yazaki M, Sato T. Familial frontotemporal dementia with a P301L tau mutation in Japan. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2000;176:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liss JM, Krein-Jones K, Wszolek ZK, Caviness JN. Speech Characteristics of Patients With Pallido-Ponto-Nigral Degeneration and Their Application to Presymptomatic Detection in At-Risk Relatives. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2006;15:226–235. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2006/021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossos A, Reches A, Gal A, Newman JP, Soffer D, Gomori JM, Boher M, Ekstein D, Biran I, Meiner Z, Abramsky O, Rosenmann H. Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism with the P301S tau gene mutation in a Jewish family. Journal of Neurology. 2003;250:733–740. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzatti C, Laiacona M, Agazzi D. Multiple patterns of writing disorders in dementia of the Alzheimer type and their evolution. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S. DRS Dementia Rating Scale - Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil MR, Duffy JR. Primary progressive aphasia. In: Chapey R, editor. Language Intervention Strategies in Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Communication Disorder. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 472–486. [Google Scholar]

- Menichelli A, Rapp B, Semenza C. Allographic agraphia: a case study. Cortex. 2008;44:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mioshi E, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Arnold R, Hodges JR. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;21:1078–1085. doi: 10.1002/gps.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohs RC. the Administration and Scoring Manual for the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale. New York: The Mount Sinai School of Medicine; 1994. Revised Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Narożańska E, Jasi ska-Myga B, Sitek EJ, Robowski P, Brockhuis B, Lass P, Dubaniewicz M, Wieczorek D, Baker M, Rademakers R, Wszolek ZK, Slawek J. Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 - the first Polish family. European Journal of Neurology. 2011;18:535–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neils-Strunjas J, Shuren J, Roeltgen D, Brown C. Perseverative writing errors in a patient with Alzheimer’s disease. Brain and Language. 1998;63:303–320. doi: 10.1006/brln.1997.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostberg P, Bogdanovic N, Fernaeus SE, Wahlund LO. Jargonagraphia in a case of frontotemporal dementia. Brain and Language. 2001;79:333–9. doi: 10.1006/brln.2001.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsen MM, Daffertshofer A, Wolters ECh, Beek PJ, Berendse HW. Impairment of complex upper limb motor function in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders. 2008;14:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapcsak SZ, Beeson PM. Neuroanatomical correlates of spelling and writing. In: Hillis AE, editor. The handbook of adult language disorders. Hove, UK: Psychology Press; 2002. pp. 71–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rey A. L’examen clinique en psychologie. Paris: Presses universitaires de France; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Roeltgen DP. Agraphia. In: Heilman KM, Valenstein EE, editors. Clinical Neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 126–145. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Cyr JA, Taylor AE, Lang AE. Procedural learning and neostriatal dysfunction in man. Brain. 1988;111:941–959. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.4.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkenberg T, Bradford DC, Ajax ET. Line bisection and unilateral Visual neglect in patients with neurologic impairment. Neurology. 1980;30:509–517. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitek EJ, Narożańska E, Sławek J, Wójcik J, Wieczorek D, Robowski P, Schinwelski M, Jasińska-Myga B, Bkaer M, Rademakers R, Wszolek ZK. Psychometric evaluation of personality in a patient with FTDP-17. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2010;64:211–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitek EJ, Narożańska E, Sławek J, Wieczorek D, Brockhuis B, Lass P, Dubaniewicz M, Jasińska-Myga B, Baker M, Rademakers R, Wszolek ZK. Unilateral neglect in a patient diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2009;21:209–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2009.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitek EJ, Barczak A, Narożańska E, Chodakowska-Żebrowska M, Jasińska-Myga B, Brockhuis B, Berdyński M, Wieczorek D, Żekanowski C, Konieczna S, Barcikowska M, Wszołek ZK, Sławek J. The role of neuropsychological assessment in the detection of early symptoms in frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) Acta neuropsychologica. 2012;9:209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Soliveri P, Rossi G, Monza D, Tagliavini F, Piacentini S, Albanese A, Bugiani O, Girotti F. A case of dementia parkinsonism resembling progressive supranuclear palsy due to mutation in the tau protein gene. Archives of Neurology. 2003;60:1454–1456. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.10.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Mesulam MM. Mental state assessment of young and elderly adults in behavioral neurology. In: Mesulam MM, editor. Principles of Behavioral Neurology. Philadelphia, USA: Davis Company; 1985. pp. 71–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek D, Jodzio K. Propozycja kompleksowej diagnozy objawów pomijania stronnego u osób z uszkodzeniem mózgu. Studia Psychologiczne. 2002;40:151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B, Cockburn J, Halligan P. Development of a behavioral test of visuospatial neglect. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1987;68:98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]