Abstract

Riboswitches are cis-acting mRNA elements that regulate gene expression in response to ligand binding. Recently, a class of riboswitches was proposed to respond to the molybdenum cofactor (Moco), which serves as a redox center for metabolic enzymes. The 5′ leader of the Escherichia coli moaABCDE transcript exemplifies this candidate riboswitch class. This mRNA encodes enzymes for Moco biosynthesis, and moaA expression is feedback inhibited by Moco. Previous RNA-seq analyses showed that moaA mRNA copurified with the RNA binding protein CsrA (carbon storage regulator), suggesting that CsrA binds to this RNA in vivo. Among its global regulatory roles, CsrA represses stationary phase metabolism and activates central carbon metabolism. Here, we used gel mobility shift analysis to determine that CsrA binds specifically and with high affinity to the moaA 5′ mRNA leader. Northern blotting and studies with a series of chromosomal lacZ reporter fusions showed that CsrA posttranscriptionally activates moaA expression without altering moaA mRNA levels, indicative of translation control. Deletion analyses, nucleotide replacement studies and footprinting with CsrA-FeBABE identified two sites for CsrA binding. Toeprinting assays suggested that CsrA binding causes changes in moaA RNA structure. We propose that the moaA mRNA leader forms an aptamer, which serves as a target of posttranscriptional regulation by at least two different factors, Moco and the protein CsrA. While we are not aware of similar dual posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms, additional examples are likely to emerge.

Keywords: global regulation, translation control, molybdenum cofactor, riboswitch

Introduction

Posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms govern gene expression at local (gene or operon specific) and global levels. The Csr (carbon storage regulator) system of eubacteria is based on a small dimeric protein, CsrA or RsmA (repressor of stationary phase metabolites). In Escherichia coli, CsrA binds to hundreds of different mRNAs and regulates translation and transcript stability on a global scale.1–3 While the regulatory consequences of most of the RNA binding interactions of CsrA remain to be established, sequence-specific RNA binding by CsrA posttranscriptionally represses genes associated with stationary phase metabolism, nutrient stress responses and biofilm formation, while it activates genes for central carbon metabolism and motility.

The sequence GGA is a highly conserved central recognition element of CsrA binding sites, which may reside in unstructured RNA but, for optimal binding, is located in the loop of a stem–loop structure.4,5 A consensus sequence for high-affinity binding, RUACARGGAUGU, was obtained by SELEX analysis.5 CsrA-mediated repression often involves binding to a site overlapping the Shine–Dalgarno (SD) sequence and one or more other sites within the translation initiation region, thus preventing ribosome binding. Translational repression can also occur by CsrA altering mRNA structure or binding exclusively in the mRNA coding region.6,7

CsrA also binds to and activates expression of certain target mRNAs, for example, flhDC,8 although no detailed activation mechanism has been established. Identical RNA binding surfaces are located on either side of the CsrA dimer and are composed of parallel β1 and β5 strands of the opposite polypeptides.9–11

Regulation of CsrA activity occurs at multiple levels.3 Several CsrA dimers bind to small noncoding RNAs, CsrB and CsrC of E. coli, which sequester and antagonize this protein.4,12,13 Transcription of these small RNAs is activated by the stringent response (ppGpp, DksA) and by acetate and shortchain carboxylates, which serve as a stimulus for the BarA/UvrY two-component signal transduction system.14–16 Thus, CsrA activity can be decreased under limitation for amino acids or other nutrients and in the presence of carbon metabolism products. Turnover of CsrB/C requires ribonuclease E, polynucleotide phosphorylase and a specificity factor, CsrD, offering another point of regulation in this system.17,18 CsrA levels are maintained under tight autoregulatory control, in which CsrA directly represses its own translation while indirectly activating its transcription.19

Riboswitches mediate cis-acting regulation and are formed by the three-dimensional folding of untranslated segments of mRNAs.20,21 Riboswitches monitor and respond to physiological cues such as temperature, levels of specific nucleotides, amino acids, ions, cofactors and the proportional charging of tRNAs. Riboswitches are often composed of an aptamer domain, which binds to a specific ligand, and an expression platform, which controls downstream gene expression. Ligand binding causes structural changes affecting transcription termination, translation initiation or mRNA stability.21,22 A few mRNAs respond to dual post-transcriptional regulatory factors, including tandem riboswitches recognizing the same23,24 or different ligands25 and an aptamer that binds to two molecules of the ligand.26 mRNAs regulated both by a riboswitch and at a distinct location, by an RNA binding protein27 or an antisense RNA28 have also been reported. mRNA for the Salmonella Mg2+ transporter mgtA is regulated by a Mg2+-sensing riboswitch and the effect of proline on a proline-rich open reading frame.29,30 Nevertheless, prior to the present study, we were aware of no riboswitch aptamer that interacts with both a low-molecular-weight ligand and an RNA binding protein.

In E. coli, the guanine dinucleotide derivative of Moco forms the active site of redox enzymes involved in anaerobic carbon, sulfur and nitrogen metabolism. 31,32 Four operons, moaABCDE, moeABC, mog and mobAB, encode gene products needed for Moco biosynthesis; modABCD is required for molybdate uptake, and modEF genes encode a Mo-binding transcription factor and protein that may be involved in molybdate uptake, respectively.33–38 Expression of the moa operon is activated by ModE and FNR transcription factors in response to molybdate availability and anaerobiosis, respectively.39,40 Genetic and bioinformatic evidence suggests that moaA transcription is feedback repressed by a riboswitch mechanism in which Moco binds to an RNA aptamer (Fig. 1) formed by the 5′ untranslated leader of this mRNA.40–42

Fig. 1.

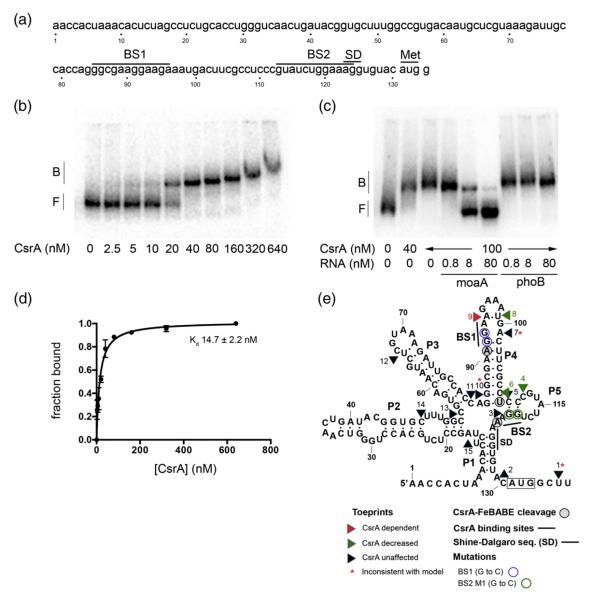

Gel mobility shift analyses of CsrA binding to moaA RNA and a secondary structure model summarizing the results of this study. (a) The moaA leader. The nucleotide sequence of the moaA leader used for gel shift analysis is shown. Putative CsrA binding sites (BS1 and BS2) are shown. The translation initiation site (Met) and the SD sequence are shown. (b and c) RNA gel mobility shift assays were performed to analyze the interactions between CsrA and the moaA leader. (b) Increasing concentrations of CsrA were incubated with 32P-labeled moaA leader (80 pM). (c) RNA competition assays. Binding reactions were performed in the presence of unlabeled specific (moaA RNA) or nonspecific (phoB RNA) competitor. The positions of free (F) and bound (B) RNAs are shown. (d) Binding curve for the reaction shown in (b). (e) Structural model of moaA mRNA based on inline probing analyses.41 Results of toeprinting, FeBABE footprinting and gel shift studies with base-substituted moaA RNAs in the CsrA binding sites (BS1 and BS2) are depicted on this structure.

Recent RNA-seq analyses identified hundreds of potential mRNA targets of CsrA binding in E. coli, including transcripts for molybdate uptake (modA), Moco biosynthesis (moaA, moeA) and Moco-dependent metabolism (narL, narGHJI, nrfAEF, fdoGI, bisC, dmsA, fdnI, hyaA, napA and torZ).14 The present studies were conducted to determine whether CsrA binds directly to the proposed moaA riboswitch and how this affects moaA expression. We confirmed that CsrA binds specifically and with high affinity to the moaA mRNA leader and posttranscriptionally activates moaA expression. We propose that a single RNA aptamer mediates the regulatory effects of both CsrA and Moco on moaA expression. The physiological implication of these findings is that CsrA should enhance the cellular capacity for Moco biosynthesis under conditions of high metabolic demand.

Results

CsrA binds to the moaA mRNA leader

The moaA transcript was identified in RNA-seq analyses, along with >700 different E. coli mRNAs that copurified with CsrA.14 To assess the basis of this observation, we used RNA gel mobility shift analysis to determine whether CsrA binds directly and specifically to the moaA leader (Fig. 1a). Mobility of the moaA mRNA leader extending from +1 to +134 was reduced upon incubation with increasing concentrations of purified CsrA-His6 (Fig. 1b). Binding was observed beginning at 5 nM CsrA. A nonlinear least-squares analysis of the data revealed an apparent Kd value of 15 nM (Fig. 1d), which is within the range of affinities (4–40 nM) for other known mRNA targets of CsrA.14,19,43 Binding specificity was demonstrated by competition assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of specific or nonspecific competitor RNAs. Addition of unlabeled specific competitor RNA (moaA RNA) competed with the formation of CsrA-moaA RNA complexes at the concentrations tested (Fig. 1c). In contrast, incubation with the phoB mRNA leader, which is not a direct target of CsrA binding,44 did not compete for binding at these concentrations (Fig. 1c). Thus, CsrA binds to the moaA leader with high affinity and specificity.

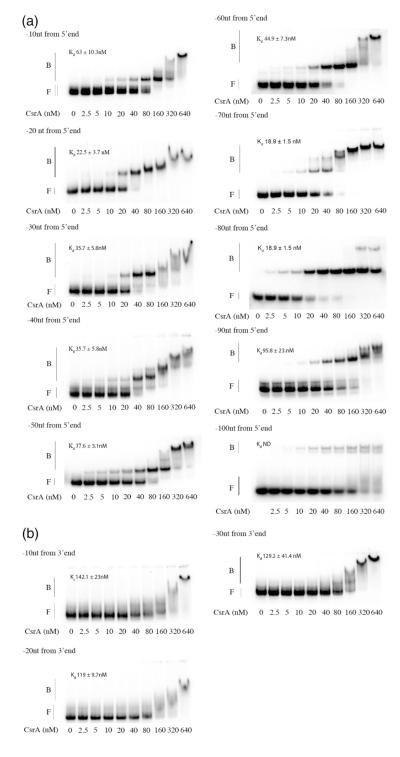

To delineate the regions of the moaA mRNA leader required for CsrA interaction, we performed gel mobility shift analysis with a series of transcripts exhibiting stepwise 10-nt deletions from the 5′ or 3′ end. Deletions from the 5′ end, extending up to nucleotide +80, exhibited moderate, if any, effects on CsrA binding (Fig. 2). Thereafter, binding affinity decreased dramatically, consistent with the loss of an important binding site. In contrast, deletions from the 3′ end of this RNA drastically affected CsrA binding; an immediate reduction in CsrA-moaA complex formation was observed upon deletion of 10 nt (Fig. 2b). The CsrA-moaA RNA complexes that were observed at high CsrA concentrations (≥160 nM) appeared as broad smears, indicating that CsrA rapidly dissociated from the RNA during gel running, which reflects the low affinity of these complexes. Taken together, the deletion analyses indicated that the 3′ end of the moaA transcript leader is critical for CsrA binding, while the 5′ end up to approximately +80 nt is dispensable for high-affinity binding.

Fig. 2.

Deletion analysis of CsrA binding to moaA RNA. Labeled transcripts (80 pM) possessing deletions in 10-nt steps from the 5′ or the 3′ end of the moaA leader RNA (Fig. 1a) were incubated with increasing concentrations of CsrA, and the resulting complexes were examined in RNA gel shift studies. (a) 5′ deletions. (b) 3′ deletions. The positions of free (F) and bound (B) RNAs are shown.

Positive footprinting of CsrA interaction with the moaA mRNA leader

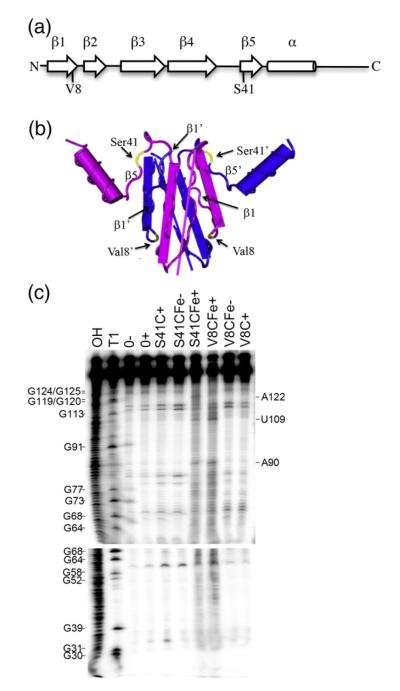

Initial attempts to directly determine the CsrA binding sites of the moaA leader by nuclease protection assays were complicated by the extensive secondary structure of this RNA (data not shown). We therefore adapted a positive footprinting approach, FeBABE footprinting, in which a protein is modified by coupling to an Fe3+ chelate at cysteine residues, which upon reduction produces hydroxyl (•OH) radicals that react with DNA or RNA residues located within a distance of up to 12 A̋ from the FeBABE moiety, leading to strand scission.45 Cysteine residues were singly introduced at two sites within the CsrA protein, Val8 and Ser41 (Fig. 3a). Val8 is located within the β1 strand, which is critical for regulation and RNA binding, but Val8 itself is not essential for regulation9 (Fig. 3b). Similarly, Ser41 is located in the β5 strand, which is essential for RNA binding, but Ser41 itself is not critical for regulation.9 Three specific cleavage sites in the moaA RNA were identified by this approach (Fig. 3). Footprinting with CsrA S41C-FeBABE protein caused cleavage at A90, U109 and A122 (Fig. 3c). Positions A90 and U109 were also cleaved in the presence of FeBABE-modified CsrA V8C (Fig. 3c). To validate this technique for mRNA footprinting, we performed a similar experiment on the glgC leader transcript, a minimally structured RNA that has been extensively characterized by RNase T1 and lead acetate footprinting, toeprinting and mutagenesis of the CsrA binding sites.46 FeBABE footprinting using CsrA S41C yielded cleavages at four sites (A92, G94, A122 and A124), indicative of CsrA binding at two positions, which is consistent with the previous studies of CsrA binding to this transcript.46 This observation validated the use of CsrA-FeBABE footprinting for analysis of CsrA binding to RNA.

Fig. 3.

Footprinting of the moaA mRNA leader RNA with CsrA-FeBABE. (a) Cysteine residues were singly introduced at two different positions within the CsrA protein, valine 8 (V8C) or serine 41 (S41C), and derivatized with the FeBABE reagent. (b) The two polypeptides of the CsrA dimer are shown as blue or purple. Note that the β1 and β5 strands of opposite polypeptides of the dimer lie parallel with each other in the three-dimensional structure of the protein.9 Residues Val8 and Ser41 are shown in yellow. (c) Footprinting of moaA leader RNA. 32P-labeled moaA RNA was incubated with no CsrA (0), CsrA S41C (500 nM) or CsrA V8C (250 nM) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of cleaving reagents, ascorbic acid and hydrogen peroxide. OH and T1 indicate moaA RNA alkaline hydrolysis and partial RNase T1 ladders, respectively. Positions of strand scission are indicated on the right. Numbering is from the start of the moaA transcript shown in Fig. 1a.

CsrA binding examined by base substitutions

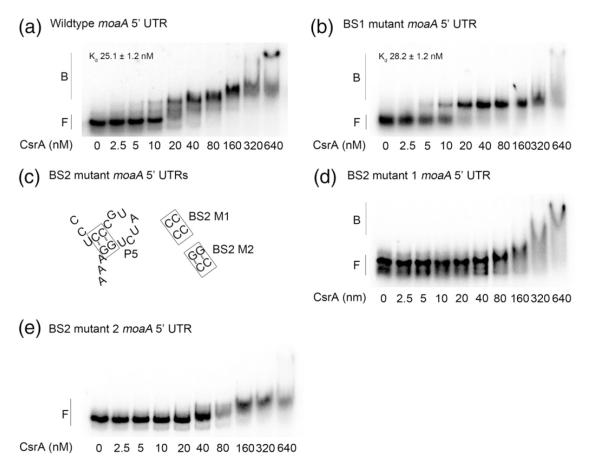

Analysis of the nucleotide sequences that were identified by deletion analyses and CsrA-FeBABE footprinting revealed two likely CsrA binding sites (Figs. 1–3). One site partially overlaps the stem of a previously determined hairpin, P4 (BS1),41 while the other lies just upstream of the SD sequence (BS2). To determine whether either site is important for CsrA binding, we replaced the GG dinucleotide of each critical GGA by CC, which greatly reduces binding to authentic sites.5 Substitutions at binding site BS1 (NT 91–92) allowed the formation of an initial complex with affinity similar to the CsrA-moaA wild-type (WT) RNA (compare Fig. 4a and b; 25 versus 28 nM). This was unexpected in view of the strong effects of deletions in this region (Fig. 2a), although the deletions likely caused more severe structural changes that interfered with CsrA binding. In contrast, substitutions in BS2 (NT 119–120) greatly reduced CsrA affinity for moaA RNA (BS2 M1; Fig. 4c and d). CsrA complexes with BS2 M1 RNA were only evident at <160 nM CsrA and appeared to be unstable, based on the appearance of a smear (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Effects of base substitutions in putative CsrA binding sites. Gel mobility shift assays were used to compare binding of CsrA to moaA leader transcripts containing GG-to-CC substitutions in putative CsrA binding sites identified by sequence analysis and FeBABE footprinting. (a) Gel shift with WT moaA leader RNA. (b) BS1-substituted RNA (NT 91–92; Fig. 1a). (c) Illustration of BS2 M1 substitutions (NT 119–120; Fig. 1a and e) and additional compensatory changes in BS2 M2 (NT 110–111) that restore base pairing. (d) Gel shifts with BS2 RNA. (e) Gel shifts with BS2 M2 RNA. The positions of free (F) and bound (B) RNAs are shown.

To determine whether the loss of CsrA binding in the BS2 mutant was due to a change in the primary sequence of a CsrA binding site or disruption of RNA secondary structure, we introduced compensatory base-pair substitutions to restore base pairing (Fig. 4c and e; BS2 M2). The latter substitutions did not further affect CsrA binding, suggesting that the loss of CsrA binding to the BS2 M1 RNA was caused by altering the sequence of this binding site and not simply by altering RNA secondary structure. These studies suggest that BS2 is necessary for high-affinity interaction of CsrA with moaA RNA, while BS1 may serve as a secondary site. Together, the BS1 and BS2 sequences appeared to fully account for CsrA binding to the moaA leader. It is noteworthy that the CsrA-FeBABE cleavage site at U109 (Fig. 3) was not associated with a conserved CsrA binding sequence and, most likely, does not represent an authentic binding site. Instead, U109 may lie close enough (within 12 A̋) to one of the two FeBABE moieties of the S41C CsrA dimer for a hydroxyl radical reaction to occur at this site when the protein interacts with the three-dimensional moaA mRNA. Indeed, in three-dimensional space, U109 is adjacent to the GGA motif of BS2 (Fig. 1e).

CsrA activates moaA expression

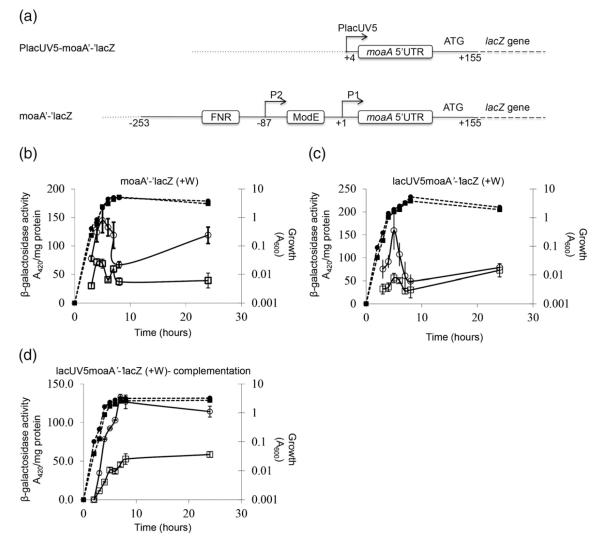

β-Galactosidase assays were performed to assess CsrA regulation of chromosomal translational and posttranscriptional fusions, moaA‘-’lacZ and PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ, respectively (Fig. 5). Fusion expression was investigated under conditions in which the repressive effects of Moco were eliminated by growth in the presence of tungstate, Na2WO4 40,47. Tungstate can replace molybdenum in the cofactor; however, the tungstate-bound cofactor does not mediate moaA repression.40,41 Expression of the moaA‘-’lacZ translational fusion showed a complex pattern with a maximum at the late exponential phase of growth. Disruption of CsrA decreased expression throughout the growth curve (Fig. 5b). Expression of the posttranscriptional fusion was driven by the constitutive lacUV5 promoter to permit the effects of CsrA on the moaA leader to be determined in the absence of potential indirect effects of CsrA on moaA transcription. Disruption of the csrA gene also reduced expression of the PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ fusion (Fig. 5c and d). Ectopic expression of the csrA gene on a plasmid restored expression of this fusion to WT levels (Fig. 5d). These findings revealed that CsrA posttranscriptionally activates moaA expression.

Fig. 5.

Effects of CsrA on expression of chromosomal moaA‘-’lacZ and PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ fusions. (a) The PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ posttranscriptional fusion and the moaA‘-’lacZ translational fusion are depicted. Binding sites for FNR and ModE transcription factors in the latter fusion are marked. Vector DNA (…) and the junctions between moaA DNA (—) and lacZ DNA (—) are also indicated. (b–d) For expression studies, cultures were harvested at various time points after inoculation (T=0) and assayed for β-galactosidase specific activity (A420 per milligram of protein). Isogenic strains were from the CF7789 strain background. We added 10 mM sodium tungstate to derepress Moco-mediated regulation. Values represent independent experiments performed in triplicate, and error bars depict standard deviation of the mean. Growth (broken lines) and β-galactosidase-specific activity (continuous lines) are presented. (b) Activity from a moaA‘-’lacZ translational fusion. CF7789, (●); csrA, (∎). (c) Activity from a PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ posttranscriptional fusion. CF7789, (●); csrA, (∎). (d) Complementation analysis of expression from a PlacUV5moaA‘-’lacZ fusion in a csrA::kan strain containing pBR322 (empty vector) (∎) or the csrA-bearing plasmid pCRA16 (●).

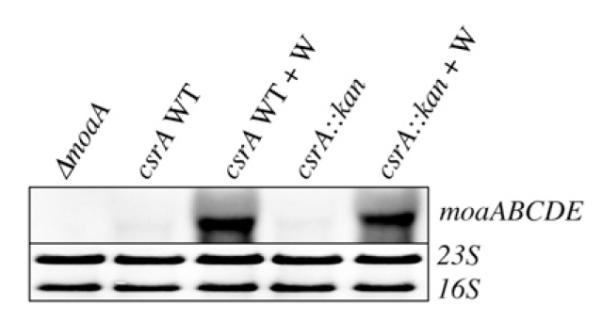

Northern blotting to test for effects of CsrA on moaABCDE mRNA

Because CsrA protein is known to affect translation and/or stability of mRNAs,1–3 Northern blotting was performed to assess the effect of CsrA on moaABCDE mRNA (Fig. 6). Total cellular RNA was isolated from WT and isogenic csrA mutant strains in the presence or absence of 20 mM tungstate (Na2WO4). Growth in the presence of Na2WO4 enhanced moa transcript accumulation in both WT and csrA mutant strains due to the loss of Moco-dependent repression under this condition.40,41 Nevertheless, a csrA mutation did not affect moa mRNA accumulation in either the presence or the absence of tungstate. No transcript was detected in a ΔmoaA::kan mutant, confirming the specificity of this analysis. In conjunction with the finding that CsrA activates expression of the PlacUV5-moaA-lacZ posttranscriptional fusion (Fig. 6), these findings suggest that the effect of CsrA on moaA expression may be mediated entirely at the level of translation.

Fig. 6.

Northern analysis of moaABCDE mRNA in csrA WT and mutant strains. Total cellular RNA was isolated from the indicated E. coli strains, which were isogenic with CF7789. RNA (1 μg) was separated on a 1.2% formaldehyde agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized with a DIG-labeled antisense moaA RNA probe. Sodium tungstate (20 mM) was added to eliminate Moco-mediated repression where indicated (+W). The 16S and 23S ribosomal RNAs served as loading controls.

CsrA binding to moaA RNA examined by toeprinting

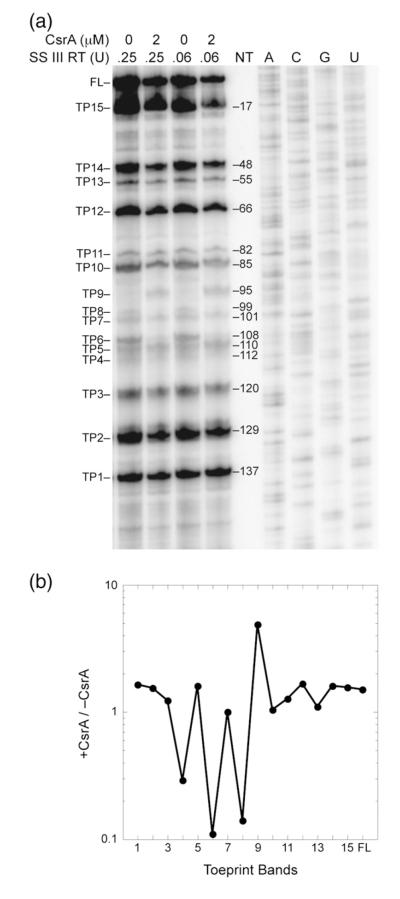

Toeprinting is a primer extension inhibition method that is used to identify the 3′ boundary of a bound protein or RNA structure. Toeprinting was used to identify RNA structures that form in the moaA leader, identify positions of bound CsrA, assess the effects of bound CsrA on RNA structure and determine if CsrA affects ribosome binding to moaA mRNA.43 One distinct CsrA-dependent toeprint was observed at nucleotide 95 (TP9), consistent with CsrA binding at BS1 (Figs. 1e and 7). In addition, a nearby toeprint at nucleotide 99 (TP8) was lost upon CsrA binding. The latter observation is consistent with a structural change occurring in the loop of the P4 stem in response to CsrA binding. Perhaps bound CsrA disrupts an unusually stable GNRA tetraloop48 that may form at the apex of the P4 stem (Figs. 1e and 7). No CsrA-dependent toeprint indicative of binding at BS2 was observed. However, a toeprint at nucleotide 112 (TP4) was reduced in the presence CsrA, which is consistent with CsrA-dependent disruption of pairing between the BS2 site (NT 119–120) and a complementary sequence (NT 110–111) in the moaA P5 stem.41 We cannot explain the absence of a CsrA-dependent toeprint in response to binding at BS2. Perhaps the close proximity of the P1 stem to BS2 influences the processivity of reverse transcriptase in this region.

Fig. 7.

Toeprinting analysis of CsrA binding to moaA mRNA. (a) The absence or presence of CsrA (2 μM) and the amount of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (SS III RT) is shown at the top of each lane. Each toeprint (TP) band is numbered with respect to its position versus the labeled primer. FL, full length. Sequencing reactions (A,C, G,U) for positioning the toeprints with respect to nucleotide sequence are also shown. The toeprinting positions are shown on a structural model for moaA RNA in Fig. 1e. (b) Quantification of the toeprint bands in lanes corresponding to 0.25 U reverse transcriptase. The intensity of each band was normalized to adjust for loading differences by dividing by the total intensity of each lane. Values of +CsrA/−CsrA are plotted with respect to each toeprint band. Bound CsrA caused a 3- to 10-fold.

Most of the structural toeprints that occurred in the absence of CsrA were located at positions of secondary structure that were predicted by the original model of this RNA41: TP2 at NT 129, P1; TP3 at NT 120, P5; TP4 at NT 112, P5; TP5 and TP6 at NT 110 and NT 108, P4; TP8 at NT 99, P4 tetraloop; TP11 at NT 82, P3; TP12 at NT 66, P3; TP13 at NT 55, P2; TP14 at NT 48, P2; TP15 at NT 17, P1 (Figs. 1e and 7). Nevertheless, three toeprints, not predicted by the structural model, were observed: TP1 at NT 136, TP7 at NT 101 and TP10 at NT 86. Note that TP12 was not predicted by the original structure41 but is consistent with an additional 2 bp of complementarity next to the terminal loop of P3, as shown in Fig. 1e.

The secondary structure that was modeled from in-line probing data of moaA RNA showed that the SD sequence is blocked by secondary structure in the absence of Moco.41 Toeprint 2 (Figs. 1e and 7) is consistent with this model. Furthermore, toeprinting reactions with 30S ribosome subunits and tRNAfMet failed to produce a signal in the presence or absence of CsrA (data not shown). Controls using glgC mRNA as the template (data not shown) yielded the same 30S toeprint that was previously observed,46 confirming that the 30S ribosomal subunits and tRNAfMet used in these studies were functional. Taken in context with gel shifts and footprinting analyses (Figs. 1–4), reporter fusion studies (Fig. 5) and Northern blotting (Fig. 6), these findings suggest that CsrA binding to moaA RNA is necessary but not sufficient to activate moaA translation.

Discussion

While CsrA has been known to regulate genes that function in aerobic carbon metabolism,49–52 recent RNA-seq analyses of transcripts that copurify with CsrA identified many mRNAs that are necessary for anaerobic respiration, including the uptake of molybdate, biosynthesis of Moco and the production of Moco-dependent enzymes.14 Here, we show that CsrA activates expression of moaA, which is needed for Moco biosynthesis. This positive regulatory role of CsrA is consistent with its known positive effects on genes of central metabolism, such as pfkA, tpi and eno, and its negative influence on genes such as glgCAP, pfkB, fbp, pgm and cstA, which are associated with secondary or stationary phase metabolism.1,2,52 Nutritional stresses that trigger ppGpp synthesis or the accumulation of metabolic products, for example, acetate, activate transcription of the CsrB/C RNA antagonists of CsrA.14,16 Thus, we propose that activation of moaA expression by CsrA serves to enhance the potential for Moco synthesis under nutritionally replete, anaerobic conditions. In addition to posttranscriptional regulation of moaA by Moco and CsrA, moaA transcription is activated by ModE and FNR in response to molybdate availability and anaerobiosis, respectively.39,40 Thus, at least four regulatory mechanisms converge to govern moaA expression.

Our decision to study the effects of CsrA on moaA expression was based in part on evidence from Regulski et al. that the 5′ mRNA leader of this gene appears to serve as a Moco-responsive riboswitch, which mediates feedback repression on the Moco biosynthesis pathway.41 Despite the fact that binding of Moco to moaA mRNA was not directly demonstrated due to the chemical instability of Moco, considerable genetic and bioinformatic evidence support this riboswitch model.41 On the other hand, CsrA bound to moaA mRNA in vivo14 and in vitro (Figs. 1–4 and 7) and posttranscriptionally activated moaA expression in vivo (Fig. 5). Furthermore, CsrA binding sites are located within the previously proposed Moco-specific aptamer.41 To our knowledge, this is the first evidence for a riboswitch aptamer that is recognized by a regulatory protein in addition to a low-molecular-weight ligand.

The preferred CsrA binding sites contain a GGA triplet that is often, though not always, found within the single-stranded loop of a short hairpin structure.4,5,9,10 Gel shift and FeBABE footprinting studies showed sequence-specific binding of CsrA at two predicted binding sites within the moaA 5′ leader (Figs. 1–4). The upstream CsrA binding site, BS1, is located within an unpaired segment of hairpin P4, whereas the downstream site, BS2, lies just upstream of the moaA SD sequence (Fig. 1). The effects of GG-to-CC dinucleotide substitutions at BS1 or BS2 implied that stronger binding occurs at BS2 (Fig. 4). Binding at BS2 may increase the local concentration of CsrA so that a single dimer might simultaneously interact with or bridge to a secondary site, BS1, at low CsrA concentrations, as previously shown for glgC mRNA.10 Whether bridging actually occurs in moaA RNA or it is relevant for activation will require further study.

While negative regulation by CsrA has been extensively investigated, examples of positive regulation, as shown for moaA, are not well understood. CsrA-mediated repression often involves competition for mRNA binding with the ribosome. In these instances, the CsrA binding sites overlap the SD sequence, the initiation codon and/or the initial coding region.1–3 A repression mechanism has also been identified in which mRNA binding by the CsrA homologue of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, RsmA, alters RNA structure by stabilizing base-pairing interactions between the SD sequence and an anti-SD sequence.6 Negative regulation of translation is frequently, though not always, associated with decreased mRNA stability. A priori, CsrA might activate gene expression by effects on translation, mRNA stability or a combination of the two. CsrA activates flhDC expression by binding to the fhlDC mRNA leader and stabilizing it, possibly by blocking RNase-E-mediated cleavage3,8 (unpublished results). Because CsrA activated a moaA posttranscriptional reporter fusion (Fig. 5) and did not affect moaABCDE mRNA levels (Fig. 6), moaA appears to represent the first example in which CsrA activates translation.

An existing model of moaA mRNA leader regulation proposes that binding of Moco to the moaA mRNA leader alters its structure in a way that affects transcription of the entire moaABCDE operon.40–42 Our Northern blotting studies supported this idea (Fig. 6), although the way in which this occurs still remains to be determined.

Nucleotide substitution studies provided evidence for high-affinity binding of CsrA at BS2, which is located just upstream from the moaA SD sequence (Figs. 1 and 4). Furthermore, a toeprint (TP4) that is consistent with the P5 stem overlaps BS2. This toeprint found to decrease upon CsrA binding, implying that a loss of secondary structure is necessary for binding at BS2 (Figs. 1e and 7). On the other hand, no CsrA-dependent toeprint was observed at BS2 (Figs. 1 and 7). While the latter result remains unexplained, it may reflect a scenario in which a CsrA toeprint at BS2 is masked by the effects of the proximal P1 stem (at the SD sequence) on reverse transcriptase progress in this segment of RNA.

We have been unable to demonstrate in vitro activation of moaA expression by CsrA in a coupled transcription–translation system, and we did not observe a toeprint for the 30S ribosomal subunit on moaA RNA (data not shown). Controls for each of these reactions, conducted in parallel using glgC as a model, revealed that CsrA and the 30S ribosomal subunit were functional in these in vitro assays, as reported previously.46,53 Because translational regulation by CsrA has been observed for many mRNAs, including glgC, pgaA, cstA, sdiA and csrA itself7,19,46,54,55 using in vitro assays, it seems that moaA translation may involve additional factors that were not present or not active in the reactions.

Along with the chemical instability of Moco,41 the apparent inability to translate moaA mRNA in vitro dictates that fundamental questions about posttranscriptional regulation via the moaA mRNA leader must await further advances: Does Moco actually bind to moaA RNA, and if so, how does this affect moaABCDE mRNA levels? What other factors or conditions are required in addition to CsrA for facilitating translation of moaA, and how is this accomplished? Does Moco binding prevent CsrA from interacting with this RNA, or might both factors bind simultaneously? Progress in answering these questions will advance our basic understanding of the diverse processes and mechanisms that have evolved for carrying out posttranscriptional regulation.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, bacteriophage, plasmids and growth conditions

All E. coli K12 strains, plasmids and bacteriophage used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacterial cultures were grown in LB medium at 37 °C and aerated by shaking at 250 rpm. Glycogen accumulation was assessed with iodine vapor staining of bacteria grown on Kornberg medium [1.1% K2HPO4, 0.85% KH2PO4, 0.6% yeast extract, 1% glucose (pH 6.8) and 1.5% agar].49 Antibiotics were added where appropriate, at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 200 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids and bacteriophage

| Strain, plasmid or phage | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| TRMG1655 | MG1655 csrA::kan | 43 |

| CF7789 | MG1655 ΔlacI-Z(MluI) | Michael Cashel |

| TRBW3414 | BW3414 csrA::kan, rpoS | 43 |

| PFLA881 | CF7789 PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ | This study |

| TR PFLA881 | PFLA881 csrA::kan | This study |

| PFA279 | CF7789 moaA‘-’lacZ | This study |

| TR PFA279 | PFA279 csrA::kan | This study |

| S17-1 λpir | λ(pir) hsdRpro thi; chromosomally integrated RP4-2 Tc::Mu Km::Tn7 | 56 |

| BW25142 |

laclqrrnB3ΔlacZ4787 hsdR514 DE(araBAD)567 DE(rhaBAD)568ΔphoBR580 rph-1 galU95ΔendA9 uidA(ΔMluI)::pir(wt) recA1 |

57 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBR322 | Cloning vector, Ampr Tetr | 58 |

| pCRA16 | csrA in blunt-ended VspI site of pBR322 | 12 |

| pLFT | Vector for translational fusions, Ampr | 14 |

| pPFINT | Vector for integration, Tetr | 14 |

| pUV5moaA | pLFT ϕ (PlacUV5-moaA‘-’-lacZ) | This study |

| pmoaA | pLFT ϕ (moaA‘-’lacZ) | This study |

| pCSB12 | csrA in NdeI and BamHI sites of pET21a+ | 5 |

| pCSB12 X#C | csrA X#C C-terminal His6-tag, derived from pCSB12 | This study |

| pCSRH6-19 | pKK223-3 expressing C-terminal His6-tag CsrA, Ampr | 4 |

| pCSRH6-19X#C | csrA X#C C-terminal His6-tag, derived from pCSRH6-19 | This study |

| pAlt-C4 | 48 | |

| pAltermoaA | moaA (LPF85:85) in EcoRI and BamHI sites of pAlter-1 | This study |

| pAltermoaA (109:110) #2 | pAltermoaA with mutations in moaA CsrA binding site BS2 | This study |

| pAltermoaA (111:112) #1 | pAltermoaA with mutations in moaA CsrA binding site BS2 | This study |

| pAltermoaA (113:114) #2 | pAltermoaA with mutations in moaA CsrA binding site BS1 | This study |

| Bacteriophage | ||

| P1 vir | Strictly lytic P1 for generalized transduction59 | Carol Gross |

RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Quantitative mobility shifts were performed as previously described.60 E. coli CsrA-His6 was expressed and purified as previously described.9 DNA templates for RNA synthesis were generated by PCR amplification of CF7789 genomic DNA or by annealing of complementary oligonucleotides (Table 2). RNA templates were synthesized in vitro using the MEGAshortscript kit (Ambion) and purified by denaturing gel electrophoresis. Purified RNA transcripts were dephosphorylated with Antarctic Phosphatase (New England Biolabs) and subsequently end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Ambion) and purified by denaturing gel electrophoresis. Binding reactions were performed for 30 min at 37 °C in 1× binding buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM KCl], 3.25 ng total yeast RNA, 20 mM DTT, 7.5% glycerol, 4 U SUPERasin (Ambion), 80 pM radiolabeled RNA and the indicated protein concentration in a final volume of 10 μl. Reaction products were separated on Tris–borate–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by phosphorimaging. Bound and unbound RNA species were quantified with Quantity One (Bio-Rad), and an apparent equilibrium binding constant (Kd) was calculated as previously described.9 Competition assays were performed to control for nonspecific protein binding. The nonspecific, unlabeled competitor RNA, phoB, was generated as described above using annealed primers phoBT7-F and phoBT7-R.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Primer | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic techniques | ||

| LPF-12 | TTGTCGGTGAACGCTCTCCT | Sequencing pLFT fusions |

| LPF-13 | AAGTTGGGTAACGCCAGG | Sequencing pLFT fusions |

| LPF-16 | CTGGATCCAGTTGTGAAGCCATGTACAC | PlacUV5-moaA and moaA-lacZ translational fusions |

| LPF-17 | AAGTCTGCAGCTCATTAGGCACCCCAGGCTTTACACTTT | PlacUV5-moaA translational fusion |

| ATGCTTCCGGCTCGTATAATGTGTGGAACCACTAAACACTCTAGCCTC | ||

| LPF-18 | AAGTCTGCAGGAGTCAGATTATCCGCGCTACAGT | moaA translational fusion |

| LPF-85 | ACGAATTCCACTAAACACTCTAGCGTC | Amplification of moaA (LPF 1:44) for cloning into pAlter-1 |

| LPF-86 | CTGGATCCCATGTACACCTTTCCAGATACGGGAGGCG | Amplification of moaA (LPF 1:44) for cloning into pAlter-1 |

| ASmoaA | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTAGCCGCCAATGTACGA | moaABCDE antisense RNA probe |

| T7fwd | TAAGTTTTGCGTAATACCGGTG | |

| ASmoaA | ATGGCTTCACAACTGACTGATGCATTTGCGCGTAAGTTTT | moaABCDE antisense RNA probe |

| T7rev | ||

| M13for20 | GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | Sequencing |

| M13rev | AACAGCTATGACCATG | Sequencing |

| RNA EMSAs | ||

| LPF-1 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCACTAAACACTCTAGCCTC | Amplify full-length moaA riboswitch |

| LPF-2 | TGCATCAGTCAGTTGTGAAGCCATGTACACC | Amplify full-length moaA riboswitch |

| LPF-42 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGCACCTGGGTCAACTGATA | CsrA binding analysis (−20 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-43 | AGTTGTGAAGCCATGTACACCTTTCCAGATAC | CsrA binding analysis (−10 nt from 3′ end) |

| LPF-44 | CCATGTACACCTTTCCATATACGGGAGGCG | CsrA binding analysis (−20 nt from 3′ end) |

| LPF-45 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCTAGCCTCTGCACCTGGG | CsrA binding analysis (−10 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-46 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCAACTGATACGGTGCTTTG | CsrA binding analysis (−30 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-47 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGGTGCTTTGGCCGTGAC | CsrA binding analysis (−40 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-48 | CTTTCCAGATACGGGAGGCGAAGTC | CsrA binding analysis (−30 nt from 3′ end) |

| LPF-49 | ACGGGAGGCGAAGTCATTTCTTCC | CsrA binding analysis (−40 nt from 3′ end) |

| LPF-50 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCCGTGACAATGCTCGTAAAG | CsrA binding analysis (−50 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-51 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGCTCGTAAAGATTGCCACC | CsrA binding analysis (−60 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-52 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGATTGCCACCAGGGCG | CsrA binding analysis (−70 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-53 | AAGTCATTTCTTCCTTCGCCCTGGTGG | CsrA binding analysis (−50 nt from 3′ end) |

| LPF-54 | TTCCTTCGCCCTGGTGGCAATCTTTACG | CsrA binding analysis (−60 nt from 3′ end) |

| LPF-55 | CTGGTGGCAATCTTTACGAGCATTGTC | CsrA binding analysis (−70 nt from 3′ end) |

| LPF-56 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGGGCGAAGGAAGAAATGAC | CsrA binding analysis (−80 nt from 5′ end) |

| LPF-57 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGAAGAAATGACTTCGCC | CsrA binding analysis (−90 nt from 5′ end) |

| TCCCGTATCTGGAAAGGTGTACATGG | ||

| GC LPF-57 | CCATGTACACCTTTCCAGATACGGGAGGCGAAGTCATTTCTT | CsrA binding analysis (−90 nt from 5′ end) |

| CCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA | ||

| LPF-58 | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTTCGCCTCCCG | CsrA binding analysis (−100 ntfrom 5′ end) |

| TATCTGGAAGGTGTACATGG | ||

| GC LPF-58 | CCATGTACACCTTTCCAGATACGGGAGGCGAA | CsrA binding analysis (−100 ntfrom 5′ end) |

| CCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA | ||

| phoBT7-F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCATTAATGATCG | phoB nonspecific competitor RNA |

| CAACCTATTTATTACAACAGGGCAAATCATG | ||

| phoBT7-R | CATGATTTGCCCTGTTGTAATAAATAGGTTGCGA | phoB nonspecific competitor RNA |

| TCATTAATGCCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTA | ||

| Site-directed mutagenesis | ||

| LPF-63 | GCCCCGAAGGAAGTTTGCGTTCACCGTGAAGAG | CsrA Ser41–Cys41 AA change; FeBABE |

| LPF-64 | CTCTTCACGGTGAACGCAAACTTCCTTCGGGGC | CsrA Ser41–Cys41 AA change; FeBABE |

| LPF-67 | GAGCGGATAACAATTTCACACA | Sequencing; CsrA-His6 site-directed mutants (in pCSRH6-19) |

| LPF-68 | TTCTCTCATCCGCCAAAACA | Sequencing; CsrA-His6 site-directed mutants (in pCSRH6-19) |

| LPF-89 | CTGATTCTGACTCGTCGATGCGGTGAGACCCTC | CsrA Val8–Cys8 AA change; FeBABE |

| LPF-90 | GAGGGTCTCACCGCATCGACGAGTCAGAATCAG | CsrA Val8–Cys8 AA change; FeBABE |

| LPF-109 | AATGACTTCGCCTGGCGTATCTCCAAAGGTGTACATGG | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| LPF-110 | CCATGTACACCTTTGGAGATACGCCAGGCGAAGTCATT | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| LPF-111 | AATGACTTCGCCTCCCGTATCTCCAAAGGTGTACATGG | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| LPF-112 | CCATGTACACCTTTGGAGATACGGGAGGCGAAGTCATT | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| LPF-113 | GCCACCAGGGCGAACCAAGAAATGACTTCGCC | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| LPF-114 | GGCGAAGTCATTTCTTGGTTCGCCCTGGTGGC | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| LPF-115 | GCCACCAGGGCGAACCAAGAAATGAGTTCGCCTCCCGTATC | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| LPF-116 | GATACGGGAGGCGAACTCATTTCTTGGTTCGCCCTGGTGGC | Site-directed mutagenesis putative CsrA binding site |

| Toeprinting | ||

| T7 MoaA-For | GAAATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCCACTAAACAC TCTAGCCTCTGCAC |

PCR amplification to produce the template for in vitro transcription |

| LacZ2 | GCTGGCGAAAGGGGGATG | Primer for PCR amplification and the primer extension reaction |

Underlined nucleotides depict the T7 promoter sequence; italicized nucleotides show restriction enzyme cleavage sites; boldfaced nucleotides identify base substitutions. Sequences are shown in the 5′-to-3′ direction.

Generation of base-substituted moaA RNAs

The moaA plasmid, pAltermoaA, was generated by PCR amplification of the moaA leader extending from +4 to +144 using primer pair LPF-85/LPF-86 (Table 2). Purified DNA was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into EcoRI and BamHI digested pAlt-C4 plasmid DNA.53 The resulting plasmid, pAltermoaA, was used as template to introduce base-pair changes within putative CsrA binding sites of the moaA leader using the QuikChange II XL kit (Stratagene). The mutations were confirmed by sequence analysis.

Construction of templates for cysteine-substituted CsrA by site-directed mutagenesis

The WT CsrA protein contains no cysteine. Thus, two CsrA-His6 proteins with single cysteine substitutions at V8 and S41, suitable for FeBABE conjugation, were created and expressed from derivatives of plasmid pCSRH6-19 or pCSB12. The QuikChange II XL kit (Stratagene) was used, as instructed by the manufacturer, to construct the mutant plasmids. Oligonucleotides for the mutagenesis reactions are listed in Table 2; changes to the DNA sequence, shown in boldface, were confirmed by sequence analysis. Functionality of the mutant genes was confirmed by their ability to complement the effect of a csrA::kan mutation on glycogen biosynthesis.9

Modeling of the three-dimensional structure of CsrA

Coordinates for the modeling of the Yersinia enterocolitica CsrA protein (Protein Data Bank ID 2BTI) were rendered using the Cn3D macromolecular structure viewer.61

CsrA-His6 protein purification

Cysteine mutant proteins were expressed and purified as previously described for WT CsrA-His69 with the addition of a heparin column purification step. Ni-NTA fractions containing the CsrA-His6 mutant proteins were diluted 4-fold in Buffer A [50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) and 100 mM NaCl] and loaded onto a HiTrap Heparin HP column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with Buffer A, and bound protein was eluted by a linear gradient of Buffer A containing 100 mM to 2 M NaCl. Column fractions were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie Blue Staining. Fractions containing CsrA protein (>95% purity) were combined and concentrated using Amicon centrifugal filter units. Binding to the moaA untranslated leader RNA by the cysteine-substituted and WT proteins was indistinguishable in gel shifts.

FeBABE modification of single cysteine mutants of CsrA

Proteins for FeBABE [p-bromoacetamidobenzyl-EDTA, iron(III) chelate] conjugation were treated consecutively with DTT (1 mM) and EDTA (20 mM) for 5 min at room temperature. Proteins were dialyzed at 4 °C against conjugation buffer [30 mM Mops, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and 5% glycerol]. Dialyzed protein was mixed with a 20-fold molar excess reconstituted FeBABE reagent (8.5 nM; Thermo Scientific), and the conjugation reaction was performed in the dark for 2 h at room temperature with gentle mixing. Unconjugated FeBABE was removed by dialysis against conjugation buffer. The extent of conjugation was analyzed by determining concentration of remaining free sulfhydryl groups using Ellman’s Reagent (Thermo Scientific). Concentrated FeBABE conjugated proteins were stored at −80 °C.

FeBABE footprinting

Footprinting reactions were performed for 30 min at 37 °C in 1× binding buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM KCl], 3.25 ng total yeast RNA, 5% glycerol, 4 U SUPERasin (Ambion), 500 pM 5′ radiolabeled RNA and the indicated protein concentration in a final volume of 20 μl. RNAs were prepared as described above except that linearized pAlt-C4 plasmid DNA was used as the template for transcription of the glgC mRNA leader.53 RNA cleavage was initiated by the addition of ascorbic acid (5 mM ascorbic acid and 1.25 mM EDTA at pH 8.0) and hydrogen peroxide solution (5 mM hydrogen peroxide and 1.25 mM EDTA at pH 8.0) followed by 1 min of incubation at 37 °C. Reactions were quenched with 0.1 M thiourea and ethanol precipitated. Precipitated RNA was resuspended in formamide loading buffer (95% formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 0.05% xylene cyanol and 0.05% bromophenol blue), separated on a 5% sequencing gel and analyzed using a phosphorimager. Partial alkaline hydrolysis and RNase T1 ladders were prepared as previously described.46,48

Toeprinting of the moaA mRNA leader

Toeprint assays followed a previously published procedure with minor modifications.62 E. coli 30S ribosomal subunits were purified as previously described.46 The DNA template for in vitro transcription was a PCR product containing the moaA leader and the first 14 bp of the moaA coding sequence fused in-frame with lacZ. This DNA template was amplified using pMoaA (moaA‘-’lacZ translational fusion cloned between the PstI and BamHI sites of pLFT14) as a template and T7 MoaA-For and LacZ2 primers. A 228-nt RNA (+3 to +144 nt relative to the transcriptional start of moaA, a BamHI site at the moaAlacZ junction and 87 nt of the lacZ coding sequence) was synthesized in vitro using the RNAMaxx High Yield Transcription kit (Agilent Technologies). Gel-purified RNA from this fusion, in Tris–EDTA buffer, was hybridized to a 5′-end-labeled primer (LacZ2) that was complementary to the 3′ end of the transcript by heating at 80 °C for 3 min, followed by slow cooling to room temperature. Toeprint reaction mixtures (10 μl) contained 2 μl of the hybridization mixture (the final concentration of the RNA and the oligonucleotide was 15 nM), 2 μM CsrA-His6 and/or 150 nM 30S ribosomal subunits with or without 5 μM tRNAfMet, 375 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate and 10 mM DTT in toeprint buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2 and 60 mM ammonium acetate]. Previously frozen 30S ribosomal subunits were thawed and activated by incubation at 37 °C for 15 min. Mixtures containing CsrA were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow CsrA-mRNA complex formation, prior to the addition of 30S subunits. 30S ribosomal subunit toeprint reactions were performed by incubating RNA, 30S ribosomal subunits with or without tRNAfMet, in toeprint buffer as described previously.63 Following the addition of 0.1–0.5 U of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) or 0.05–0.2 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs), we incubated the reaction mixture at 37 °C for 15 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 6 μl of formamide-containing loading buffer. Samples were heated for 2 min at 90 °C prior to fractionation through standard 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gels. Radioactive bands were visualized using a phosphorimager.

Northern blotting

E. coli cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.8–1.0 in LB medium supplemented with 20 mM sodium tungstate (as indicated), and total cellular RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN). Total cellular RNA was separated on a 1.2% agarose formaldehyde gel and transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche Diagnostics) by electro-blotting using the Mini Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad). RNA was fixed to the membrane by UV cross-linking. Blots were hybridized overnight at 68 °C with a DIG-labeled antisense moaA RNA probe using the DIG Northern Starter kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The antisense moa RNA probe encompassing the entire moaA open reading frame was transcribed in vitro using the DIG Northern Starter kit (Roche Diagnostics) from a PCR product that was generated using the primer pair ASmoaAT7for and ASmoaAT7rev (Table 2). Blots were developed using the ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad) and quantified using Quantity One image analysis software (Bio-Rad).

Construction of chromosomal moaA‘-’lacZ and PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ translational fusions

The moaA reporter fusions, moaA‘-’lacZ and PlacUV5-moaA‘-’lacZ were generated by PCR amplification of the upstream regulatory region of moaA extending from −253 to +155 and from +4 to +155 relative to the start of transcription, respectively. Primer pairs for PCR amplification are listed in Table 2. Purified DNAs were digested with PstI and BamHI and cloned into PstI and BamHI digested pLFT plasmid DNA.14 The resulting plasmids, pmoaA and pUV5moaA, were sequenced to confirm successful in-frame insertion of the moaA insert. Fusions were integrated into the chromosome of CF7789 or MC CF7789 as previously described.57

β-Galactosidase and total protein assays

β-Galactosidase experiments were performed as previously described.14 All experiments were performed in triplicate. Total cellular protein was measured using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Biotechnology) with bovine serum albumin as the protein standard.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health, R01 GM059969 (T.R. and P.B.), R01 AI097116 (TR), and by the University of Florida CRIS project FLA-MCS-004949 (T.R.).

Abbreviations used

- SD

Shine–Dalgarno

- WT

wild type

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

References

- 1.Romeo T. Global regulation by the small RNA binding protein CsrA and the noncoding RNA CsrB. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:321–1330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babitzke P, Romeo T. CsrB sRNA family: sequestration of RNA-binding regulatory proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007;10:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romeo T, Vakulskas CA, Babitzke P. Posttranscriptional regulation on a global scale: form and function of Csr/Rsm systems. Environ. Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02794.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu MY, Gui G, Wei B, Preston JF, III, Oakford L, Yuksel U, et al. The RNA molecule CsrB binds to the global regulatory protein CsrA and antagonizes its activity in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17502–17510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubey AK, Baker CS, Romeo T, Babitzke P. RNA sequence and secondary structure participate in high-affinity CsrA–RNA interaction. RNA. 2005;11:1579–1587. doi: 10.1261/rna.2990205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irie Y, Starke M, Edwards AN, Wozniak DJ, Romeo T, Parsek MR. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix polysaccharide Psl is regulated transcriptionally by RpoS and posttranscriptionally by RsmA. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;78:158–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yakhnin H, Baker CS, Berezin I, Evangelista MA, Rassin A, Romeo T, Babitzke P. CsrA represses translation of sdiA, encoding the N-acylhomoserine-l-lactone receptor of Escherichia coli by binding exclusively within the coding region of sdiA mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:6162–6170. doi: 10.1128/JB.05975-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei BL, Brun-Zinkernagel AM, Simecka JW, Pruss BM, Babitzke P, Romeo T. Positive regulation of motility and fhlDC expression by the RNA-binding protein CsrA of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:245–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercante J, Suzuki K, Cheng X, Babitzke P, Romeo T. Comprehensive alanine-scanning mutagenesis of Escherichia coli CsrA defines two subdomains of critical functional importance. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:31832–31842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606057200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercante J, Edwards AE, Dubey AK, Babitzke P, Romeo T. Molecular geometry of CsrA (RsmA) binding to RNA and its implications for regulated expression. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;392:511–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schubert M, Lapouge K, Duss O, Oberstrass FC, Jelesarov I, Haas D, Allain FH. Molecular basis of messenger RNA recognition by the specific bacterial repressing clamp RsmA/CsrA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:807–813. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki K, Wang X, Weilbacher T, Pernestig AK, Melefors O, Georgellis D, et al. Regulatory circuitry of the CsrA/CsrB and BarA/UvrY systems of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:5130–5140. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.18.5130-5140.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weilbacher T, Suzuki K, Dubey AK, Wang X, Gudapaty S, Morozov I, et al. A novel sRNA component of the carbon storage regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:657–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards AN, Patterson-Fortin LM, Vakulskas CA, Mercante JW, Potrykus K, Vinella D, et al. Circuitry linking the Csr and stringent response global regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;80:1561–1580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonas K, Melefors O. The Escherichia coli CsrB and CsrC small RNAs are strongly induced during growth in nutrient-poor medium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;297:80–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chavez RG, Alvarez AF, Romeo T, Georgellis D. The physiological stimulus for the BarA sensor kinase. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:2009–2012. doi: 10.1128/JB.01685-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K, Babitzke P, Kushner SR, Romeo T. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2605–2617. doi: 10.1101/gad.1461606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonas K, Edwards AN, Ahmad I, Romeo T, Romling U, Melefors O. Complex regulatory network encompassing the Csr, c-di-GMP and motility systems of Salmonella Typhimurium. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;12:524–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yakhnin H, Yakhnin AV, Baker CS, Sineva E, Berezin I, Romeo T, Babitzke P. Complex regulation of the global regulatory gene csrA: CsrA-mediated translational repression, transcription from five promoters by Eσ70 and EσS. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;81:689–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henkin TM. Riboswitch RNAs: using RNA to sense cellular metabolism. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3383–3390. doi: 10.1101/gad.1747308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth A, Breaker RR. The structural and functional diversity of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070507.135656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. From ribosome to ribowitch: control of gene expression in bacteria by RNA structural rearrangements. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;41:329–338. doi: 10.1080/10409230600914294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandal M, Lee M, Barrick JE, Weinberg Z, Emilsson GM, Ruzzo WL, Breaker RR. A glycine-dependent riboswitch that uses cooperative binding to control gene expression. Science. 2004;306:275–279. doi: 10.1126/science.1100829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welz R, Breaker RR. Ligand binding and gene control characteristics of tandem riboswitches in Bacillus anthracis. RNA. 2007;13:573–582. doi: 10.1261/rna.407707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudarsan N, Hammond MC, Block KF, Welz R, Barrick JE, Roth A, Breaker RR. Tandem riboswitch architectures exhibit complex gene control functions. Science. 2006;314:300–304. doi: 10.1126/science.1130716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trausch JJ, Ceres P, Reyes FE, Batey RT. The structure of a tetrahydrofolate-sensing riboswitch reveals two ligand binding sites in a single aptamer. Structure. 2011;19:1413–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fox KA, Ramesh A, Stearns JE, Bourgogne A, Reyes-Jara A, Winkler WC, Garsin DA. Multiple posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms partner to control ethanolamine utilization in Enterococcus faecalis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4435–4440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812194106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.André, G., Even S, Putzer H, Burgière P, Croux C, Danchin A, et al. S-box and T-box riboswitches and antisense RNA control a sulfur metabolic operon of Clostridium acetobutylicum. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:5955–5969. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cromie MJ, Shin Y, Latifi T, Groisman EA. An RNA sensor for intracellular Mg2+ Cell. 2006;125:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S-Y, Cromie MJ, Lee E-J, Groisman EA. A bacterial mRNA leader that employs different mechanisms to sense disparate intracellular signals. Cell. 2010;142:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarz G, Mendel RR. Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis and molybdenum enzymes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:18343–18350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarz G. Molybedenum cofactor biosynthesis and deficiency. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:2792–2810. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5269-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nohno A, Kasai Y, Saito T. Cloning and complete nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli chlEN operon involved in molybdopterin biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:4097–4102. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4097-4102.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson JL, Indermaur LW, Rajagopalan KV. Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: requirement of the chlB gene product for the formation of the molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:12140–12145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajagopalan KV, Johnson JL. The pterin molybdenum cofactors. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10199–10202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iobi-Nivol C, Palmer T, Whitty PW, McNairn E, Boxer DH. The mob locus of Escherichia coli K12 required for molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis is expressed at very low levels. Microbiology. 1995;141:1663–1671. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maupin-Furlow JA, Rosentel JK, Lee JH, Deppenmeier U, Gunsalus RP, Shanmugam KT. Genetic analysis of the modABCD (molybdenum transport) operon of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:4851–4856. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4851-4856.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rech S, Deppenmeier U, Gunsalus RP. Regulation of the molybdate transport operon, modABCD, of Escherichia coli in response to molybdate availability. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:1023–1029. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.1023-1029.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNicholas PM, Rech SA, Gunsalus RP. Characterization of the ModE DNA-binding sites in the control regions of modABCD and moaABCDE of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;23:515–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.d01-1864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson LA, McNairn E, Leubke T, Pau RN, Boxer DH. ModE-dependent molybdate regulation of the molybdenum cofactor operon moa in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:7035–7043. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.24.7035-7043.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regulski EE, Moy RH, Weinberg Z, Barrick JE, Yao Z, Ruzzo WL, Breaker RR. A widespread riboswitch candidate that controls bacterial genes involved in molybdenum cofactor and tungsten cofactor metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;68:918–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker KP, Boxer DH. Regulation of the chlA locus of Escherichia coli K12: involvement of molybdenum cofactor. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:901–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pannuri A, Yakhnin H, Vakulskas CA, Edwards AN, Babitzke P, Romeo T. Translational repression of NhaR, a novel pathway for multi-tier regulation of biofilm circuitry by CsrA. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:79–89. doi: 10.1128/JB.06209-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards AN. Ph.D. Dissertation. Emory University; Atlanta, GA: 2010. The global regulatory role of the RNA binding protein CsrA. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heilek GM, Marusak R, Meares CF, Noller HF. Directed hydroxyl radical probing of 16S rRNA using Fe(II) tethered to ribosomal protein S4. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:1113–1116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker CS, Morozov I, Suzuki K, Romeo T, Babitzke P. CsrA regulates glycogen biosynthsis by preventing translation of glgC in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;44:1599–1610. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kletzin A, Adams MW. Tungsten in biological systems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1996;18:5–63. doi: 10.1016/0168-6445(95)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bevilacqua JM, Bevilacqua PC. Thermodynamic analysis of an RNA combinatorial library contained in a short hairpin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15877–15884. doi: 10.1021/bi981732v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romeo T, Gong M, Liu MY, Brun-Zinkernagel AM. Identification and molecular characterization of csrA, a pleiotropic gene from Escherichia coli that affects glycogen biosynthesis, gluconeogenesis, cell size, and surface properties. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:4744–4755. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.15.4744-4755.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabnis NA, Yang H, Romeo T. Pleiotropic regulation of the central carbohydrate metabolism in Escherichia coli via the gene csrA. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:29096–29104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang H, Liu MY, Romeo T. Coordinate genetic regulation of glycogen catabolism and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli via the CsrA gene product. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:1012–1017. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.1012-1017.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romeo T. Post-transcriptional regulation of bacterial carbohydrate metabolism: evidence that the gene product CsrA is a global mRNA decay factor. Res. Microbiol. 1996;147:505–512. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)84004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu MY, Romeo T. The global regulator CsrA of Escherichia coli is a specific mRNA-binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:4639–4642. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4639-4642.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang X, Dubey AK, Suzuki K, Baker CS, Babitzke P, Romeo T. CsrA post-transcriptionally represses pgaABCD, responsible for synthesis of a biofilm polysaccharide adhesin of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:168–1663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dubey AK, Baker CS, Suzuki K, Jones AD, Pandit P, Romeo T, Babitzke P. CsrA regulates translation of the Escherichia coli carbon starvation gene, cstA, by blocking ribosome access to the cstA transcript. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4450–4460. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4450-4460.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon R, Priefer U, Pohler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Biotechnology. 1983;1:784–791. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haldimann A, Wanner BL. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:6384–6393. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6384-6393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yakhnin AV, Trimble JJ, Chiaro CR, Babitzke P. Effects of mutations in the l-tryptophan binding pocket of the Trp RNA-binding attenuation protein of Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4519–4524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Geer LY, Chappey C, Kans JA, Bryant SH. Cn3D: sequence and structure views for Entrez. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:300–302. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yakhnin H, Pandit P, Petty TJ, Baker CS, Romeo T, Babitzke P. CsrA of Bacillus subtilis regulates translation initiation of the gene encoding the flagellin protein (hag) by blocking ribosome binding. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;64:1605–1620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hartz D, McPheeters DS, Traut R, Gold L. Extension inhibition analysis of translation initiation complexes. Methods Enzymol. 1988;164:419–425. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)64058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]