Abstract

Purpose

Radiation therapy (RT) often induces enteritis by inhibiting proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) has been shown to protect the intestine in several animal injury models. The objective of this study was to examine whether HB-EGF affects RT-induced intestinal injury.

Methods

HB-EGF or PBS was administered intraperitoneally to mice daily for 3 days, followed by total body irradiation (TBI). Three days after TBI, intestinal segments were harvested, and BrdU immunohistochemistry was performed to identify proliferating crypts (n=25). Four days after TBI, intestinal segments were harvested and assessed for histologic injury (n=34), and FITC-dextran was administered via gavage with serum FITC-dextran levels quantified to determine gut barrier function (n=18).

Results

Compared to non-HB-EGF-treated irradiated mice, administration of HB-EGF to irradiated mice led to a significantly increased percentage of proliferative crypts (72.6% vs. 50.5%, p=0.001), a significantly decreased percent of histologic sections with severe histologic injury (13.7% vs. 20.3%, p=0.005), and significantly reduced intestinal permeability (18.8 µg/mL vs. 22.6 µg/mL, p=0.02).

Conclusions

These results suggest that administration of HB-EGF protects the intestines from injury after exposure to radiation therapy. Administration of HB-EGF may represent a novel therapy for the prevention of radiation enteritis in the future.

Keywords: HB-EGF, radiation injury, intestines, proliferation, permeability

Sixty to ninety percent of cancer patients receiving abdominal or pelvic radiation therapy develop some degree of intestinal injury [1]. Signs and symptoms of mucositis, dysmotility, and obstruction vary in onset, duration, and severity. The potential development of radiation enteritis or proctitis has turned the intestine into a dose-limiting organ for the administration of abdominal and pelvic radiation therapy. Without the availability of preventive therapy, radiation enteritis remains a concern for patients intolerant of radiation therapy, often limiting the use of this highly effective treatment modality.

Toxic exposure to radiation damages cellular DNA, often resulting in the loss of cellular proliferation or even immediate cell death. Rapidly dividing cells, such as mucosal crypt cells, are most sensitive to this type of injury. Radiation exposure reduces the ability of crypt cells to proliferate and differentiate into epithelial cells, limiting the ability of the mucosa to recover from the injury. Apoptosis, increased reactive oxygen species production, and severe inflammatory changes ensue throughout the mucosal lining and the wall of the intestine [2]. In acute radiation enteritis, these pathologic changes typically result in ulcer formation, mucositis, and gut barrier dysfunction. Injury leading to chronic radiation enteritis is often characterized by malabsorption, dysmotility, obstruction, or fistula formation [1].

Management of acute radiation enteritis ranges from antibiotics and antiemetics to parenteral nutritional support or surgical intervention. Patients are typically treated with antidiarrheal, antiemetic, and spasmolytic agents. Similarly, treatment options for chronic radiation enteritis are dependent on the underlying pathology and often include prokinetics, antibiotics, and dietary alterations [1]. While therapeutic options for symptomatic relief have been identified, reduced radiation dosages and fractions are often required [2].

Initially identified in 1990 as a secreted product of cultured human macrophages, heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF) is a glycoprotein member of the EGF family [3]. Through interactions with EGF receptor subtypes ErbB1 and ErbB4, as well as the HB-EGF-specific receptor N-arginine dibasic convertase (Nardilysin) [4], HB-EGF promotes cell proliferation and migration of many cell types including smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells [3] [5]. Using several different animal models of intestinal injury, we have shown that administration of HB-EGF down-regulates pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [6], preserves intestinal epithelial cell proliferation [7], and decreases reactive oxygen species production [8]. We further showed that administration of HB-EGF protects the lungs from remote organ injury after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury [9]. The therapeutic effects of HB-EGF in the intestine have been explored in our laboratory using animal models of necrotizing enterocolitis [10], ischemia/reperfusion injury [11], and hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation [12]; however, the ability of HB-EGF to protect the intestines from radiation injury has never been investigated. The present study was designed to evaluate the effects of HB-EGF in an animal model of radiation therapy-induced intestinal injury.

1. METHODS

1.1. Mouse model of radiation therapy-induced enteritis

The following experimental protocol followed the guidelines for the ethical treatment of experimental animals as approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #01802AR). Eight to twelve week-old female B6D2F1 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were randomized to the following three groups: (1) control mice that were non-irradiated and received 200 µL of PBS intraperitoneally (IP) once daily for three consecutive days (no RT group) (N=19); (2) mice that received 200 µL of PBS IP once daily for three consecutive days followed by exposure to total body irradiation (TBI) at a dose of 10 Gray in a 137 cesium-based gamma irradiator (IBL 437, CIS Bio International) (RT group) (N=28); or (3) mice that received intraperitoneal HB-EGF [800 µg/kg in 200 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] (Trillium Therapeutics Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada) once daily for three consecutive days followed by TBI (RT + HB-EGF group) (N=30).

At the end of the experiment, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation under inhaled 2% isoflurane, USP (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL).

1.2. Mucosal crypt cell proliferation

Mucosal crypt cell proliferation was determined using bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) immunohistochemistry (IHC). BrdU is a uridine derivative that can be incorporated into DNA during the synthesis-phase of the cell cycle as a thymidine substitute. Mice were randomized to the following three groups: (1) no RT (n=8); (2) RT (n=8); and (3) RT + HB-EGF (n=9). Animals received BrdU (30 mg/kg) (Invitrogen Corporation, Camarillo, CA) IP 69 h after TBI, with non-irradiated animals receiving BrdU simultaneously. Four hours later, animals were sacrificed and the gastrointestinal tract was removed. Portions of duodenum, jejunum, and ileum were collected from every animal and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 4-µm thickness. Sections were then stained using the BrdU Streptavidin-Biotin System (Invitrogen Corporation, Camarillo, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Proliferating cells were identified by positive nuclear staining, indicative of BrdU incorporation. Mucosal crypts containing 3 or more BrdU-positive cells were considered to be proliferative crypts. Results were quantified as the percentage of proliferative crypts per intestinal segment.

1.3. Histologic injury score

The degree of radiation-induced injury was assessed in mice 4 days after receiving radiation therapy. Mice were randomized to the following three groups: (1) no RT (n=7); (2) RT (n=13); and (3) RT + HB-EGF (n=14). Upon sacrifice, the gastrointestinal tract was carefully removed and segments of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and descending colon/rectum were collected from each animal. Segments were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h, paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 4-µm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). A radiation injury scoring system described by others [13] was modified and utilized by two independent investigators to blindly score two sections per intestinal segment from each animal. Histologic abnormalities were graded as follows: grade 0, normal; grade 1, infiltration of inflammatory cells or mucosal hemorrhage; grade 2, vacuolization of the villi, abnormally oriented crypts, or mucosal hypertrophy; grade 3, submucosal cysts or irregular crypt regeneration with atypical epithelial cells; and grade 4, ulcerated mucosa or transmural necrosis. Sections receiving grades 3 or 4 were considered to have severe histologic injury. The proportion of sections with severe histologic injury per intestinal segment was compared between groups.

1.4. Gut barrier function

To determine gut barrier function, we studied the mucosal permeability of the intestine to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran (MW 4 kDa [FD4]) (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO), which has been shown in previous studies to provide a reliable evaluation of mucosal integrity [14] [15]. Mice were randomized to the following three groups: (1) no RT (n=4); (2) RT (n=7); and (3) RT + HB-EGF (n=7). Animals received FD4 (500 mg/kg in water) via gavage 4 days after TBI. Blood was collected 4 h later at the time of sacrifice. The concentration of FD4 in the serum of each animal was measured using spectrophotofluorometry (SpectraMax M2e, Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA). Serum concentrations of the samples were calculated based on standard dilution curves of known FD4 concentrations.

1.5. Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. The percent of proliferating mucosal crypts and serum concentrations of FITC-labeled dextran between groups were compared using the Student’s t test. The proportion of sections with severe histologic injury was compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 software (Microsoft Office, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) or GraphPad Prism software (version 5.01, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

2. RESULTS

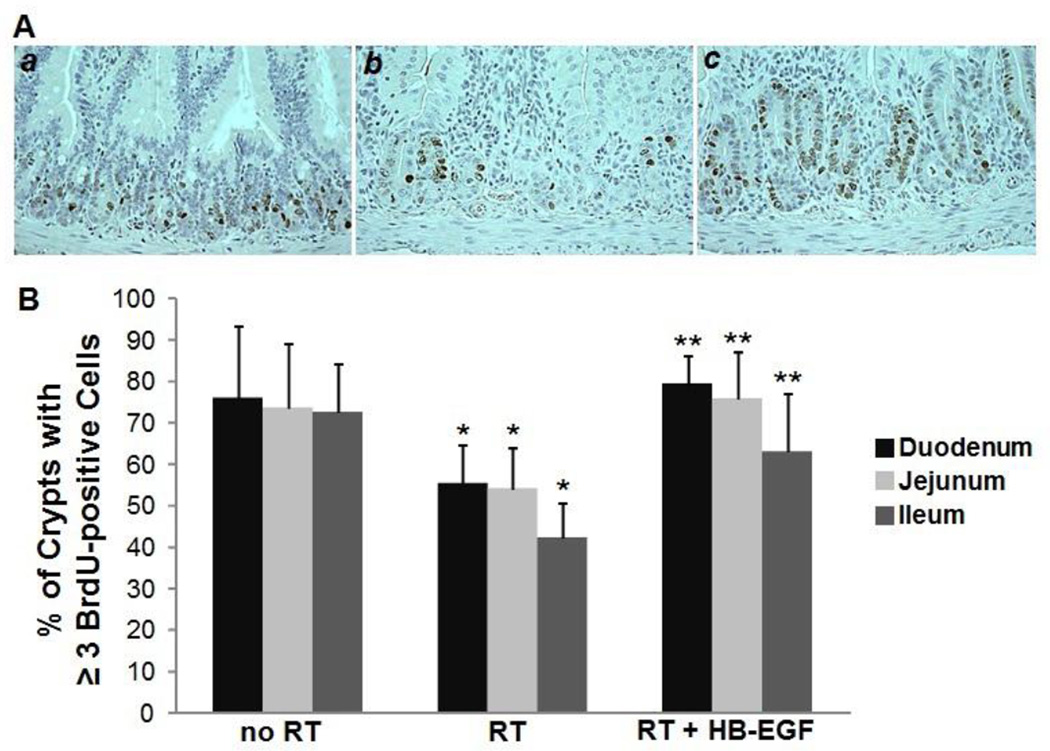

2.1. Administration of HB-EGF preserves mucosal crypt cell proliferation after RT-induced intestinal injury

Since radiation exposure inhibits mucosal crypt cell proliferation and HB-EGF stimulates crypt cell proliferation, we began by examining the effect of HB-EGF on mucosal crypt cell proliferation after radiation exposure. BrdU IHC was used to identify proliferating cells (Figure 1A). In uninjured animals, the average percent of proliferative crypts was 75.8% ± 17.6 in the duodenum, 73.5% ± 15.4 in the jejunum, and 72.5% ± 11.6 in the ileum (Figure 1B). Compared to non-irradiated animals, the percent of proliferative crypts in irradiated animals was significantly decreased to 55.1% ± 9.3 in the duodenum (p=0.03), 54.1% ± 9.9 in the jejunum (p=0.01), and 42.2% ± 8.4 in the ileum (p=0.0003). Compared to irradiated animals that received PBS, treatment of irradiated animals with HB-EGF significantly increased the percentage of proliferative crypts to 79.2% ± 6.8 in the duodenum (p=0.00004), 75.7% ± 11.2 in the jejunum (p=0.004), and 63% ± 14.1 in the ileum (p=0.01). Thus, HB-EGF treatment induced a significant increase in mucosal crypt cell proliferation in the small intestine of irradiated animals.

Figure 1. Mucosal crypt cell proliferation after RT-induced intestinal injury.

(A) Shown are representative photomicrographs of BrdU immunohistochemistry of the duodenum of non-irradiated mice (a), irradiated mice (b), and irradiated mice treated with HB-EGF (c). Images at 40× magnification. (B) Quantification of the percent of proliferative crypts. *p < 0.05 vs. no RT; **p < 0.05 vs. RT.

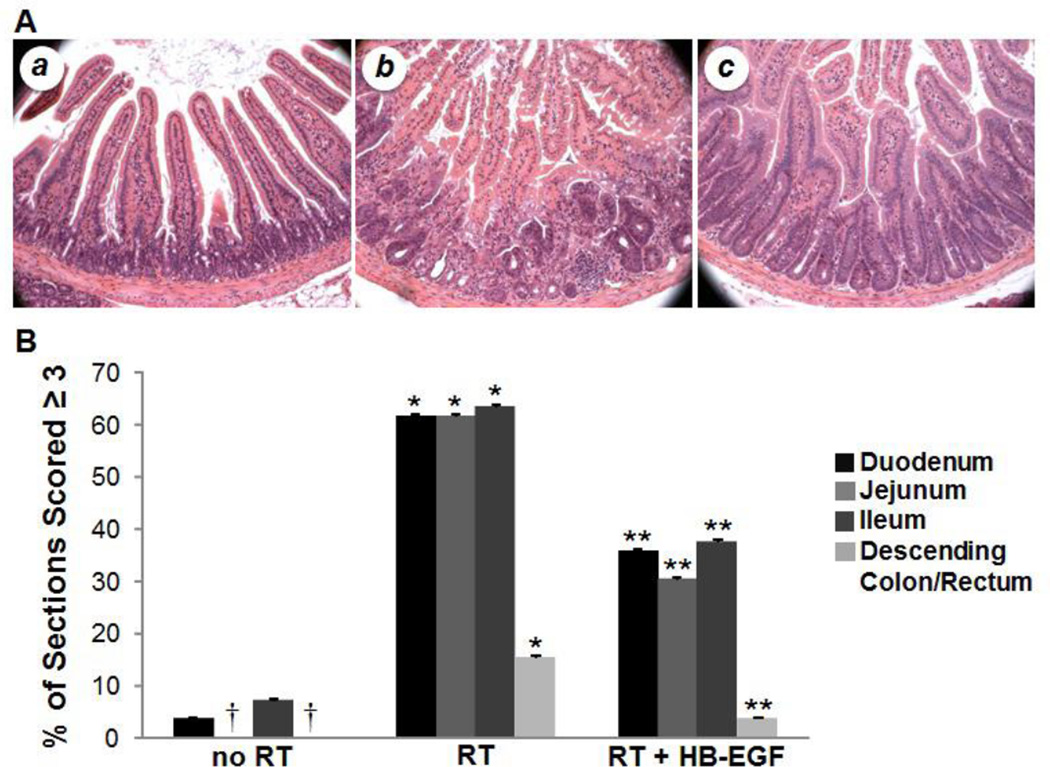

2.2. Administration of HB-EGF reduces intestinal histologic injury after RT-induced intestinal injury

Intestinal sections receiving a score of 3 or 4 were considered to have severe histologic injury. Analysis of uninjured animals showed very little evidence of intestinal injury (Figure 2A,B). In contrast to uninjured animals, exposure to radiation led to significantly increased intestinal injury, with severe histologic injury in 61.5% ± 0.49 of duodenal sections (p<0.0001), 61.5% ± 0.49 of jejunal sections (p<0.0001), 63.5% ± 0.48 of ileal sections (p<0.0001), and 15.4% ± 0.36 of descending colon/rectal sections (p=0.0143). Compared to non-HB-EGF-treated irradiated animals, irradiated animals treated with HB-EGF had significantly decreased intestinal injury, with severe histologic injury in only 35.7% ± 0.48 of duodenal sections (p=0.004), 30.4% ± 0.46 of jejunal sections (p=0.0006), 37.5% ± 0.48 of ileal sections (p=0.004), and 3.6% ± 0.19 of descending colon/rectal sections (p=0.02). These results indicate that animals treated with HB-EGF developed less severe histologic injury upon exposure to radiation therapy.

Figure 2. Intestinal histologic injury after RT-induced intestinal injury.

Shown are representative photomicrographs of H&E stained duodenum from non-irradiated mice (a), irradiated mice (b), and irradiated mice treated with HB-EGF (c). Images at 20× magnification. (B) RT led to significant histologic injury compared with non-irradiated intestine. Irradiated mice treated with HB-EGF had significantly decreased histologic injury compared with non-HB-EGF-treatment irradiated mice. †No sections of jejunum or descending colon/rectum were scored ≥ 3. *p < 0.05 vs. No RT; **p < 0.05 vs. RT + PBS.

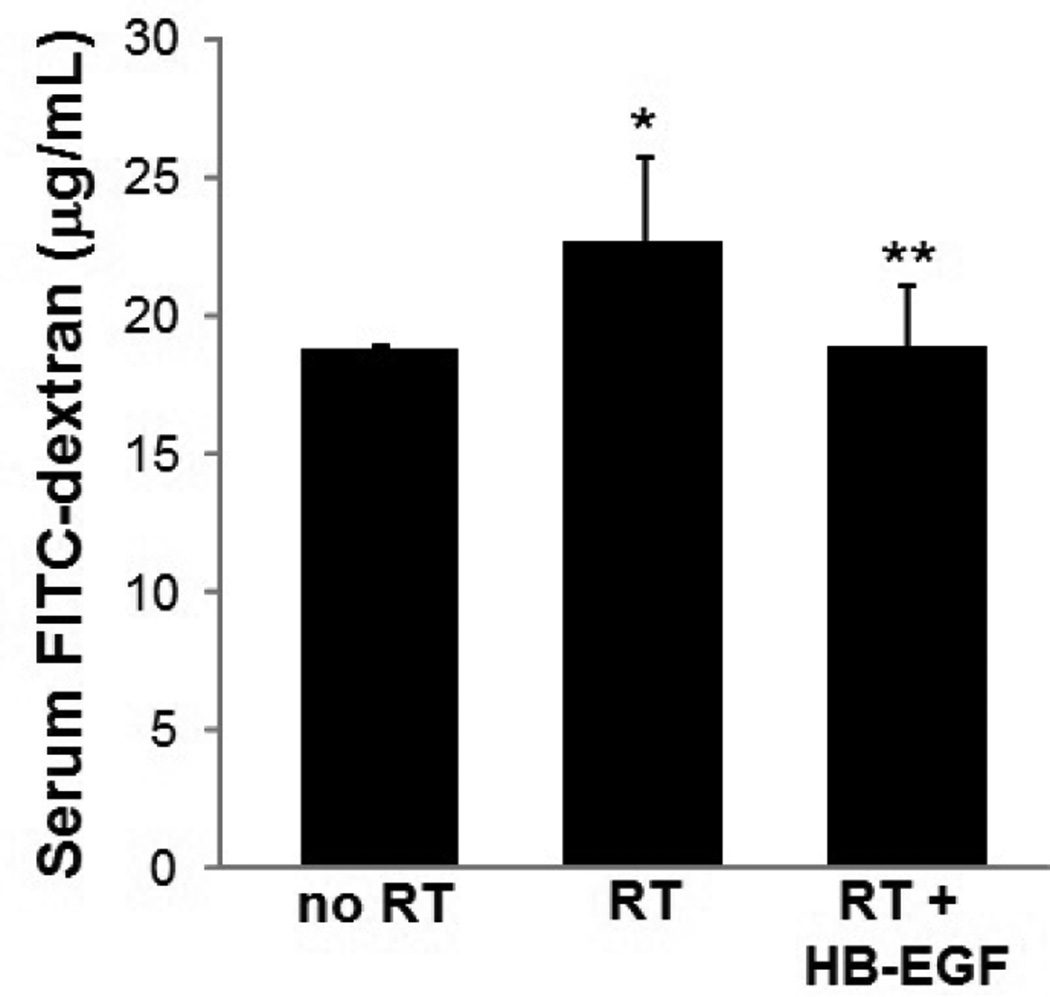

2.3. Administration of HB-EGF preserves gut barrier function after RT-induced intestinal injury

To determine gut barrier function, we studied the mucosal permeability of the intestine to FITC-dextran. After enteral administration of FD4, serum FD4 levels were 18.67 ± 0.25 µg/mL in uninjured animals (Figure 3). Serum FD4 concentrations were significantly increased in irradiated animals compared to uninjured animals (22.58 ± 3.15 µg/mL, p=0.049). Irradiated mice treated with HB-EGF had significantly lower serum FD4 levels compared to non-HB-EGF-treated irradiated animals (18.8 ± 2.26 µg/mL, p=0.017).

Figure 3. Gut barrier function after RT-induced intestinal injury.

Serum FITC-dextran levels were significantly increased after exposure to RT compared to non-irradiated mice (22.58 ± 3.15 µg/mL vs. 18.67 ± 0.25 µg/mL; *p=0.049). Irradiated mice pre-treated with HB-EGF had lower serum FITC-dextran levels compared with irradiated mice that did not receive HB-EGF (18.8 ± 2.26 µg/mL vs. 22.58 ± 3.15 µg/mL; **p=0.017).

3. DISCUSSION

In 2009, the estimated number of abdominal or pelvic cancer survivors in the United States exceeded 5 million, according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute. If half of those with abdominal or pelvic cancer received radiation therapy, it is likely that approximately 1.7 to 2.6 million patients developed some degree of radiation enteritis. Therapeutic options available to these patients are aimed at alleviating symptoms after the intestine has undergone significant damage. However, preventive interventions prior to the progression of intestinal injury are desirable. As we have previously demonstrated, HB-EGF protects the intestines from various forms of injury when administered prophylactically or therapeutically [10] [11] [12]. The present study examined the effects of prophylactic administration of HB-EGF on the progression of radiation therapy-induced intestinal injury.

One of the most significant aspects of radiation injury is cellular DNA damage in rapidly dividing cells. Due in part to the enormous proliferation and differentiation potential of intestinal stem cells located in the mucosal crypts, the intestinal epithelium is the most rapidly proliferating tissue in adult mammals. Intestinal stem cells divide to produce a new stem cell as well as a rapidly proliferating transit amplifying daughter cell. The latter cell type undergoes several cell divisions and then terminally differentiates into one of four intestinal epithelial cell lineages that comprise the mucosal lining. In response to injury, intestinal epithelial cells from healthy areas migrate to the injured sites, followed by an increase in mucosal crypt cell proliferation. The current study demonstrates that exposure to radiation significantly impairs mucosal crypt cell proliferation. More importantly, we have shown that administration of HB-EGF prior to radiation therapy promotes the proliferation of mucosal crypt cells. These findings are consistent with our previous findings that HB-EGF promotes crypt cell proliferation in experimental necrotizing enterocolitis [7] and after ischemia/reperfusion injury [16].

Apoptosis and enhanced inflammatory processes ultimately cause histologic damage to the mucosal lining of the intestine after exposure to radiation. Similar to previous studies [13], the current study shows that radiation therapy induces significant histologic injury to segments of the intestine. Importantly, we demonstrate that the administration of HB-EGF protects the intestine from developing severe radiation-induced histologic injury.

The progression of histologic damage without adequate mucosal recovery leads to a breakdown in the mucosal barrier of the intestine. Increased mucosal permeability often results in the translocation and dissemination of microorganisms. The risk of systemic infection is increased in the setting of bacterial overgrowth secondary to intestinal dysmotility, which is often seen in chronic radiation enteritis [1]. In our study, exposure to radiation led to a significant increase in mucosal permeability of the intestine. Importantly, we demonstrate preservation of gut barrier function with HB-EGF administration.

To further explore the role of HB-EGF as a preventive therapy, we must consider its use in future clinical trials. Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that HB-EGF exerts intestinal protective effects when administered either enterally or intravenously. While the pharmacokinetics of both intragastric- and IV-administered HB-EGF have been described [17], the pharmacokinetics of IP-administered HB-EGF are unknown. We chose to administer HB-EGF via IP injections due to previous studies performed in our laboratory. The timing of HB-EGF administration in our study was influenced by the model of Farrell et al. (1998) in which they examined the protective effects of keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) in radiation therapy-induced enteritis by administering KGF as 3 daily subcutaneous injections [18], as well as by our previous studies of HB-EGF in other animal models, in which it was administered several times a day. While we administered HB-EGF via IP injection in the current study, it could be administered either enterally or IV in future clinical trials.

In order to identify preventive therapies for radiation enteritis, investigators have examined the effects of several other growth factors in models of radiation-therapy induced intestinal injury. KGF and recombinant human EGF were found to reduce histologic injury, improve crypt survival, and enhance crypt cell proliferation in the small intestine [18] [19]. The intestinal stem cell growth factor R-spondin 1 has also been shown to improve crypt survival and crypt cell proliferation in the jejunum, as well as prevent malabsorption [20]. In examining the use of fibroblast growth factor (FGF), an FGF1–FGF2 chimera (FGFC) was created in order to avoid concurrent administration of exogenous heparin, a necessity for the stability and activity of FGF1 alone. FGFC without exogenous heparin was found to be more effective at improving crypt survival and increasing crypt cell proliferation in the jejunum when given after radiation therapy compared to FGF1 [21]. Unlike the studies described above, which typically examined only one region of small bowel, the current study assessed histologic injury in all regions of the small intestine as well as in the descending colon/rectum. Also, by studying changes in intestinal permeability, we were able to assess the ability of HB-EGF to preserve gut barrier function in radiation-induced intestinal injury.

Based on these results, we conclude that administration of HB-EGF preserves mucosal crypt cell proliferation, reduces intestinal histologic injury, and maintains gut barrier function in intestine exposed to radiation therapy. Future studies are being designed to investigate the mechanisms by which HB-EGF exerts its protective effects on irradiated intestine. Our results support the potential future use of HB-EGF for the prevention of radiation therapy-induced enteritis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 M61193 (GEB) and NIH T32 CA 90223-8 (MAM)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hauer-Jensen M, Wang J, Denham JW. Bowel injury: current and evolving management strategies. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:357–371. doi: 10.1016/s1053-4296(03)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bismar MM, Sinicrope FA. Radiation enteritis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2002;4:361–365. doi: 10.1007/s11894-002-0005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besner G, Higashiyama S, Klagsbrun M. Isolation and characterization of a macrophage-derived heparin-binding growth factor. Cell Regul. 1990;1:811–819. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.11.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta VB, Zhou Y, Radulescu A, et al. HB-EGF stimulates eNOS expression and nitric oxide production and promotes eNOS dependent angiogenesis. Growth Factors. 2008;26:301–315. doi: 10.1080/08977190802393596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis-Fleischer KM, Besner GE. Structure and function of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) Front Biosci. 1998;3:d288–d299. doi: 10.2741/a241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocourt DV, Mehta VB, Besner GE. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor decreases inflammatory cytokine expression after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2007;139:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng J, Besner GE. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor promotes enterocyte migration and proliferation in neonatal rats with necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn MA, Xia G, Mehta VB, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) decreases oxygen free radical production in vitro and in vivo. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:639–646. doi: 10.1089/15230860260220148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James IA, Chen CL, Huang G, et al. HB-EGF protects the lungs after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2010;163:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radulescu A, Zorko NA, Yu X, et al. Preclinical neonatal rat studies of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor in protection of the intestines from necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:437–442. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181994fa0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillai SB, Hinman CE, Luquette MH, et al. Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor protects rat intestine from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 1999;87:225–231. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang HY, Radulescu A, Chen CL, et al. Mice overexpressing the gene for heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF) have increased resistance to hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation. Surgery. 2011;149:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langberg CW, Sauer T, Reitan JB, et al. Tolerance of rat small intestine to localized single dose and fractionated irradiation. Acta Oncol. 1992;31:781–787. doi: 10.3109/02841869209083871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver SR, Phillips NA, Novosad VL, et al. Hyperthermia induces injury to the intestinal mucosa in the mouse: evidence for an oxidative stress mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R845–R853. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00595.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q, Fang CH, Hasselgren PO. Intestinal permeability is reduced and IL-10 levels are increased in septic IL-6 knockout mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1013–R1023. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.3.R1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia G, Martin AE, Michalsky MP, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor preserves crypt cell proliferation and decreases bacterial translocation after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1081–1087. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.33881. discussion 1081–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng J, Mehta VB, El-Assal ON, et al. Tissue distribution and plasma clearance of heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF) in adult and newborn rats. Peptides. 2006;27:1589–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell CL, Bready JV, Rex KL, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor protects mice from chemotherapy and radiation-induced gastrointestinal injury and mortality. Cancer Res. 1998;58:933–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh H, Seong J, Kim W, et al. Recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rhEGF) protects radiation-induced intestine injury in murine system. J Radiat Res. 2010;51:535–541. doi: 10.1269/jrr.09145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhanja P, Saha S, Kabarriti R, et al. Protective role of R-spondin1, an intestinal stem cell growth factor, against radiation-induced gastrointestinal syndrome in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama F, Hagiwara A, Umeda S, et al. Post treatment with an FGF chimeric growth factor enhances epithelial cell proliferation to improve recovery from radiation-induced intestinal damage. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]