Abstract

Objectives

To determine the effect of stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging in an observation unit (OU) on revascularization, hospital readmission, and recurrent cardiac testing in intermediate risk patients with possible acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Background

Intermediate risk patients commonly undergo hospital admission with high rates of coronary revascularization. It is unknown whether OU-based care with CMR is a more efficient alternative.

Methods

We randomized 105 intermediate risk participants with symptoms of ACS but without definite ACS based on the first electrocardiogram and troponin to usual care provided by Cardiologists and Internists (n=53) versus OU care with stress CMR (n=52). We determined the primary composite endpoint of coronary artery revascularization, hospital readmission, and recurrent cardiac testing at 90 days. The secondary endpoint was length of stay from randomization to index visit discharge; safety was measured as ACS after discharge.

Results

The median age of participants was 56 (range 35 to 91) years, 54% were men, and 20% had pre-existing coronary disease. Index hospital admission was avoided in 85% of the OU-CMR participants. The primary outcome occurred in 20 (38%) usual care versus 7 (13%) OU-CMR participants (hazard ratio 3.4, 95% CI 1.4 – 8.0, p = .006). The OU-CMR group experienced significant reductions in all components: revascularizations [15% vs 2%, p=0.03], hospital readmissions [23% vs 8%, p = .03], and recurrent cardiac testing [17% vs 4%, p = .03]. Median length of stay was 26 hours (IQR: 23 – 45) in the usual care group and 21 hours (IQR: 15 – 25) in the OU-CMR group (p < .001). ACS after discharge occurred in 3 (6%) usual care and no OU-CMR participants.

Conclusions

In this single center trial, management of intermediate risk patients with possible ACS in an OU with stress CMR reduced coronary artery revascularization, hospital readmissions, and recurrent cardiac testing without an increase in post-discharge ACS at 90 days.

Keywords: chest pain, acute coronary syndrome, angioplasty, balloon, coronary, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Recent reports have demonstrated the adaptability of CMR for testing ED patients with symptoms concerning for ACS.(1–5) Attributes of CMR making this modality appealing for use in ED patients are the ability to diagnose MI prior to troponin elevation(1), differentiate between new and old infarcts(6), and accurately determine prognosis(7). These strengths of CMR allow patients at intermediate risk for ACS, commonly managed as inpatients, to be evaluated in an OU setting.

In intermediate risk patients, OU-based care with stress CMR testing reduced cost over the course of one year when compared to an inpatient care strategy in a recent analysis of a single-center randomized trial.(8) An ancillary finding of that trial was a reduction in coronary revascularization associated with OU-CMR that did not reach statistical significance. Reducing revascularization procedures may be desirable since they are expensive and up to two-thirds of coronary revascularization procedures in the US are of uncertain appropriateness or do not meet appropriateness criteria.(9) In addition, emerging evidence is signifying that intervention in stable coronary lesions may not improve outcomes,(10) and revascularization is associated with a high rate of readmissions and repeat revascularizations in the short-term following the procedure.(11) Together these data suggest that efficiency gains could result from more carefully selecting patients for coronary revascularization procedures.

Evaluating the efficiency of a cardiac-related care pathway must consider not only coronary revascularization but also the impact on other clinical events, such as the need for additional cardiac testing, hospital readmissions, and delayed cardiac events. We hypothesized that an OU-CMR care strategy would provide a highly accurate, noninvasive, comprehensive assessment during the index visit, thereby allowing some patients to safely avoid revascularization while simultaneously reducing hospital readmissions and recurrent cardiac testing. Accordingly, we conducted a single-center trial powered to detect a difference in the composite of coronary revascularization, hospital readmission, and recurrent cardiac testing 90 days from randomization between OU-CMR and usual inpatient care strategies.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a randomized, controlled, single-center clinical trial funded by NIH/NHLBI 1 R21 HL097131-01A1. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Wake Forest School of Medicine and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01035047) prior to enrollment. All participants provided written consent for study participation and were randomized to an OU-CMR strategy or usual care, an inpatient-based strategy. In the OU-CMR strategy, participants were managed in an OU setting, had serial troponin measurements at 4 and 8 hours from arrival, and underwent a stress CMR exam at the first available time. Participants in the usual care group were evaluated by the inpatient service for hospital admission and further diagnostic evaluation as determined by their care providers. Disposition decisions and subsequent testing in both groups were performed at the discretion of the care providers.

Setting

Participants were recruited from the ED of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. The study institution is a tertiary care academic medical center located in the Piedmont Triad area of North Carolina, serving urban, suburban, and rural populations. The ED volume in 2011 consisted of 103,000 patient encounters. This study population is distinct from other studies we have previously published from the OU setting.

At the study institution, patients with chest pain and related complaints, but without definite ACS, are risk stratified by attending emergency physicians in the ED as low risk (TIMI Risk Score <2) or elevated risk. Low risk patients are managed in the OU whereas elevated risk patients are managed as inpatients. Cardiac imaging modalities available in the OU and inpatient settings include stress imaging with echocardiography, nuclear, and CMR, coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA), and invasive catheter coronary angiography. The OU is staffed by midlevel providers and oversight is provided by attending emergency physicians. These care providers are have been exposed to the clinical use of CMR imaging since 2008, and have managed intermediate risk participants with CMR imaging in previous trials.(4,8)

Participants

Patients at least 21 years old presenting with symptoms suggestive of ACS were screened and those eligible were consecutively approached during enrollment hours (6 days excluding Saturday, 80 hours/week). Eligibility criteria required an inpatient or OU evaluation of the patient’s symptoms due to at least intermediate risk chest pain defined as either a Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction risk score(12) of ≥2 (corresponding to 10% or greater risk of ACS at 30 days in undifferentiated chest pain patients(13)) or a physician global risk assessment based on the ACC/AHA guidelines(14) of intermediate or high risk. Additionally, at the time of enrollment, the ED attending had to declare the patient as being safe for OU care, and that the patient could be discharged home if cardiac disease was excluded as the cause of symptoms. Patients were determined ineligible for the following reasons: definite ACS at the time of enrollment (elevated initial troponin, new ST-segment elevation [≥1 mm] or depression [≥2mm]), known inducible ischemia, hypotension, contraindications to CMR, life expectancy <3 months, pregnancy, coronary revascularization within 6 months, and increased risk for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (defined in the study as creatinine clearance <45 ml/min or < 60 ml/min if concomitant chronic liver disease, clinical concern for acute kidney injury, hepatorenal syndrome, or solid organ transplant).

Randomization

After obtaining written consent, participants were stratified based on the presence of known coronary disease (≥50% stenosis, prior MI or revascularization), and assigned within strata to one of the two treatment arms with equal probability using variably sized permuted block randomization. The randomization sequence was generated using nQuery Advisor 6.0 (Statistical Solutions, Saugus MA) and integrated into a secure website which was used by the study coordinators to register participants and obtain the study group assignments. The clinical investigators and staff were blinded to the randomization sequence.

Study Procedures

After randomization, usual care participants underwent consultation in the ED by the admitting service in accordance with customary practice. Care delivery in this group was not directed by the study protocol. In the OU-CMR group, orders were placed for serial troponin and ECG assessments at 4 and 8 hours after the initial evaluation, placement into observation status, and for a vasodilator CMR exam to be conducted at the first available time. CMR exams were integrated into the daily case load of exams without special scheduling provisions for this study. Clinical reports from the CMR exams were interpreted by the care providers in the OU to make a decision to discharge the patient home or obtain a cardiology consultation. Interpretations, the need for cardiology consultation, and decisions to perform revascularization were not directed by the study protocol.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Participants underwent CMR imaging in accordance with imaging protocols used in previous trials and for clinical care at the study site that have been previously described in detail.(4,5) Imaging was performed on a 1.5 Tesla Siemens Magnetom Avanto system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). An initial order was placed for an adenosine vasodilator stress exam, with regadenosine and dobutamine available as alternatives. Participants underwent assessments of resting wall motion, T2 imaging for edema, stress perfusion, rest perfusion, and delayed enhancement. Images were interpreted by a reading pool of board certified Cardiology and Radiology faculty with at least level II training in CMR(15) with results entered into the electronic medical record.

Blinding

Per protocol, inpatient care providers in the usual care group were not informed of the subject’s participation. Subjects were also asked to refrain from discussing their participation in a clinical trial with inpatient clinical staff. Because care providers in the OU-CMR group were integral to delivering the care pathway, these providers could not be blinded to the study intervention. Participants in both groups were not routinely made aware of the study endpoints during the consent or follow up process.

Data collection and processing

The study was conducted in accordance with standards of Good Clinical Practice, Standardized Reporting Guidelines(16), and Key Data Elements and Definitions(17). A detailed sources of data map was created prior to study initiation. Medical records were used as the source for data elements reliably contained in the medical record. Data collection templates were implemented to prospectively collect data from patients and ED care providers that were not reliable or not present in the electronic medical record. Data were recorded on web-based case report forms and transferred to a secure Structured Query Language relational database.

Follow up was conducted during the index visit using a structured record review. At both 30 and 90 days, a structured record review was followed by a structured telephonic interview. Outcome events reported at other healthcare facilities were confirmed using a structured review of those medical records. Incomplete telephone follow up at 90 days was handled using the following algorithm: participants with ongoing visits in the electronic medical record were considered to have complete information and were classified based on the data available in the medical record; participants with no ongoing visits were considered lost to follow up at the point of last contact (index visit discharge or 30 day telephone interview) and were censored in the analysis. Separate analyses were conducted assuming that those participants with no telephone contact had no events, as evidenced by their lack of events on chart review.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of coronary revascularization, all-cause hospital readmission, and recurrent cardiac testing within 90 days of randomization. Coronary revascularization included percutaneous and surgical revascularization occurring anytime after randomization. Hospital readmission was defined as an overnight stay, or placement into observation or inpatient status for > 8 hours, for all causes, after the index visit. Recurrent cardiac testing was defined as receiving one or more of the following procedures after index visit discharge: cardiac echocardiography, CMR, nuclear imaging, coronary CT angiography, or invasive angiography.

The secondary outcome was index visit length of stay, defined as the time elapsed between randomization and discharge from the facility. Safety events were all-cause mortality within 90 days, adverse events related to index visit stress testing, and ACS after discharge and within 90 days of randomization, defined as one of the following: a) acute myocardial infarction based on the universal definition(18), b) ischemia symptoms leading to revascularization, c) death likely related to cardiac ischemia, d) discharge diagnosis of unstable angina with evidence of >70% coronary stenosis or inducible ischemia on stress testing if coronary angiography not performed.

Sample size

A three-stage, group sequential design was used to assess the difference in event rates of the primary outcome between the two groups. We calculated that twenty-seven events were needed to provide 80% power for detecting a hazard ratio of 3.0 at the 5% two-sided level of significance when data are analyzed 3 times according to the O’Brien-Fleming stopping rules(19) (S+ SeqTrial, TIBCO Spotfire, Somerville, MA). The anticipated effect size was based on preliminary data from another trial(8) demonstrating 28% vs 9% event rates (hazard ratio 3.5) for the primary outcome favoring OU-CMR. We anticipated that approximately 146 patients would be needed to achieve the required 27 events based on the estimate of the fraction of patients experiencing an event.

Data analysis

For the primary outcome, the time to the composite outcome was the minimum time to any of the component events. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate the time to event distributions for the two groups. Participants lost to follow-up were considered censored at their last contact. The primary test for the group effect was accomplished using a CPH regression model for the time to the composite event. The primary model was based on intent to treat and included the assignment group and the stratification factor as covariates. The results of this analysis were compared to the O’Brien-Fleming stopping boundaries(19) during two interim analyses and the final analysis. At the final analysis, the null hypothesis was rejected if the p-value was less than 0.045. Length of stay was measured as a continuous variable from the time of ED presentation to the time of hospital discharge. All participants were discharged; there were no index visit deaths. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess the group difference in length of stay. Data analysis was conducted with SAS v9.2 and SAS Enterprise Guide v4.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

Results

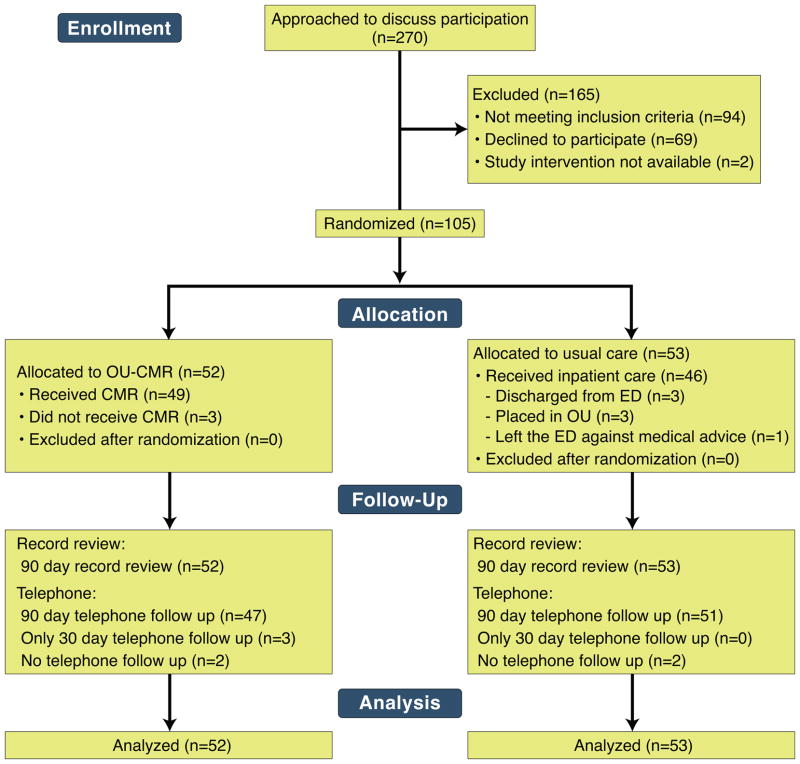

Over 67 weeks, 4996 patients presented during the hours of screening and had either a chief complaint of chest pain or troponin plus an electrocardiogram ordered. Of these with available information, the median age was 56 years, 48% were men, and 24% had prior coronary disease. From this population, 270 patients were approached, and 105 consented and enrolled (Figure 1). After randomizing 105 subjects, (inpatient n=53, OU-CMR n=52), the target number of participants with events (27) was observed. No participants were removed from the study cohort after randomization and analysis was performed based on intent to treat. Follow-up was conducted via chart review in all participants, and all but six completed the telephone interview for 90-day events (Figure 1). To understand the likelihood of undetected events among these six participants, the proportion of participants experiencing events not referenced in the medical records of the study institution was calculated. In total, 26/27 (96%) participants with events had evidence of the event in the records of the study institution. The remaining event was confirmed by obtaining medical records from another institution.

Figure 1. Consort diagram.

The study randomized 105 participants to OU-CMR (n=52) or usual care (n=53). All were analyzed based on intent to treat. OU, observation unit; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; ED, emergency department;

The study cohort had a median age of 56 (range 35–91) years, 54% were men, 30% had a history of diabetes mellitus, and 20% were known to have pre-existing coronary artery disease (Table 1). Chest pain was the chief complaint among 91% of participants, 89% had pain at rest, 65% had numerous episodes within 24 hours, and 60% had a normal ECG at presentation (Table 2). The TIMI risk score measured near the time of randomization did not differ among study groups and was most commonly 2 or 3 (range 0 to 5).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Past Medical History

| Patient Characteristic | Usual care N=53 n (%) |

OU-CMR N=52 n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) – median (range) | 59 (40–76) | 54 (35–91) |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 15 (28) | 9 (17) |

| Male sex | 29 (55) | 28 (54) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Black | 15 (28) | 20 (38) |

| White | 37 (70) | 29 (56) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) – median (range) | 29.6 (19.7–46.8) | 30.7 (16.4–51.2) |

| Underweight | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Normal | 13 (25) | 12 (23) |

| Overweight | 16 (30) | 10 (19) |

| Obese | 24 (45) | 29 (56) |

| Hypertension | 45 (85) | 37 (71) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (30) | 16 (31) |

| Current smoking | 20 (38) | 21 (40) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 39 (74) | 33 (63) |

| Prior Heart Failure | 1 (2) | 3 (6) |

| Prior MI | 7 (13) | 9 (17) |

| Prior PCI | 9 (17) | 7 (13) |

| Prior CABG | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft;

Table 2.

Presenting Characteristics and Physical Exam Findings

| Usual care n/N (%) |

OU-CMR n/N (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenting Characteristics | |||

| Chest pain chief complaint‡ | 47/50 (94) | 46/52 (88) | .488 |

| Chest pain at rest‡ | 43/50 (86) | 48/52 (92) | .353 |

| Multiple episodes of symptoms within 24 hours§ | 30/49 (61) | 29/52 (56) | .578 |

| Chest pain present on arrival to the ED§ | 34/50 (68) | 32/52 (62) | .495 |

| Chest pain pleuritic‡ | 3/50 (6) | 6/52 (12) | .488 |

| Physical Exam | |||

| Heart rate (beats/min)* | 78 (12) | 78 (16) | .946 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)* | 149 (21) | 146 (21) | .570 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)* | 87 (12) | 82 (14) | .058 |

| Rales‡ | 0/50 (0) | 1/52 (2) | 1.0 |

| Chest pain reproducible‡ | 4/47 (9) | 5/47 (11) | 1.0 |

| Overall ECG classification‡ | .213 | ||

| Normal | 34/53 (64) | 29/52 (56) | |

| Nonspecific changes | 12/53 (23) | 8/52 (15) | |

| Early repolarization only | 0/53 (0) | 1/52 (2) | |

| Abnormal but not diagnostic of ischemia | 3/53 (6) | 6/52 (12) | |

| Infarction or ischemia known to be old | 1/53 (2) | 6/52 (12) | |

| Infarction or ischemia not known to be old | 3/53 (6) | 2/52 (4) | |

| Suggestive of acute MI | 0/53 (0) | 0/52 (0) | |

| Risk Stratification | |||

| ED physician assessment of % likelihood of ACS within 30 days† | 5 (5–10) | 5 (5–10) | .852 |

| TIMI risk score|| | .873 | ||

| 0 | 1/53 (2) | 1/52 (2) | |

| 1 | 8/53 (15) | 2/52 (4) | |

| 2 | 21/53 (40) | 29/52 (56) | |

| 3 | 19/53 (36) | 17/52 (33) | |

| 4 | 3/53 (6) | 2/52 (4) | |

| 5 | 1/53 (2) | 1/52 (2) | |

data presented as mean(SD) and analyzed with t-test;

data presented as median(IQR) and analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis test;

Fisher exact test;

chi-squared test;

Kruskal-Wallis test

ED, Emergency Department; ECG, Electrocardiogram; MI, myocardial infarction; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

In subjects randomized to usual care, the disposition from the ED was inpatient admission for 46 patients (87%), discharge for 3 (6%), OU for 3 (6%), and leaving against medical advice for 1 (2%). In the OU-CMR group, all were placed in the OU from which 44 (85%) participants were discharged home; the remaining 8 (15%) participants were admitted. Median length of stay from randomization to final discharge from the hospital was 26 hours (IQR: 23 – 45) in the usual care group and 21 hours (IQR: 15 – 25) in the OU-CMR group (p < .001).

Cardiac imaging or angiography during the index visit was performed in 48/53 (91%) usual care participants and all OU-CMR participants. In the usual care group, the first test modalities were stress echo in 33 (62%), catheterization in 8 (15%), stress CMR in 3 (6%), resting echo in 3 (6%), coronary computed tomographic angiography in 1 (2%), and no testing in 5 (9%) participants. Median time to completion of testing in the usual care group was 22 (IQR: 19–26) hours. The first cardiac test in the OU-CMR group was CMR in 50 (96%) and stress echo in 2 (4%) participants (Table 3). Median time to completion of the first test was 21 (IQR: 16–23) hours.

Table 3.

Cardiac Testing and Disposition During the Index Hospital Visit

| Usual care N=53 n (%) |

OU-CMR N=52 n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First cardiac test completed | --- | ||

| None | 5 (9) | 0 (0) | |

| Stress CMR | 3 (6) | 50 (96) | |

| Stress echo | 33 (62) | 2 (4) | |

| Resting echo | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Stress nuclear imaging | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Cardiac catheterization | 8 (15) | 0 (0) | |

| Coronary computed tomographic angiography | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Elapsed time: ED arrival to first cardiac imaging test completed (hours)* | 22.3 (18.7 – 25.8) | 20.9 (15.7 – 23.4) | .028 |

| Hospital admission from ED or observation unit | 47 (89) | 8 (15) | --- |

data presented as median (IQR);Kruskal-Wallis test

Fisher exact test

CMR, Cardiac Magnetic Resonance; ED, Emergency Department

During the index visit, an elevated troponin occurred in 8 participants (5 usual care, 3 OU-CMR participants) after randomization and prior to invasive angiography (Table 4). On cardiac imaging, 6 (12%) OU-CMR participants had acute or inducible ischemia, all detected with vasodilator stress CMR, leading to invasive angiography in 5, and revascularization in 1; 2 had abnormal delayed enhancement, one from an acute MI and one from a prior MI. In the usual care group, 11 (21%) participants received invasive angiography during the index visit leading to revascularization in 7 (13%).

Table 4.

Participants with a Troponin above the upper limit of normal or receiving revascularization during the index visit

| Age (yrs) | Sex | Group | Peak troponin pre-cath (ng/ml) | Peak troponin (ng/ml) | First test | Target vessel(s) | Maximum target vessel stenosis | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | Male | OU-CMR | - | 0.06 | CMR | - | - | |

| 48 | Male | OU-CMR | 1.99 | 214.3 | CMR | Ramus | 100 | PCI |

| 48 | Female | OU-CMR | - | 0.41 | CMR | - | - | - |

| 40 | Male | UC | 0.14 | 56.9 | Cath | RCA | 20 | RCA dissection during cath |

| 58 | Male | UC | 0 | 0.06 | CMR | Graft vessel | 90 | PCI |

| 61 | Female | UC | 0.13 | 0.13 | Cath | Distal RCA | 90 | PCI |

| 61 | Male | UC | 0.02 | 0.14 | Cath | Mid LAD and prox circ | 80 and 98 | PCI |

| 63 | Male | UC | 0.02 | 0.02 | Stress echo | Prox LAD | 90 | CABG |

| 67 | Female | UC | 1.59 | 1.59 | Cath | Second diagonal | 80 | PCI |

| 67 | Male | UC | - | 1.63 | Stress echo | - | - | Ischemic stroke |

| 68 | Male | UC | - | .05 | Stress echo | - | - | - |

| 71 | Male | UC | 0 | 0 | Stress echo | Prox LAD | 90 | CABG |

UC, usual care; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; LAD, left anterior descending; RCA, right coronary artery; mid, middle; Cath, catheterization; prox, proximal; circ, circumflex;

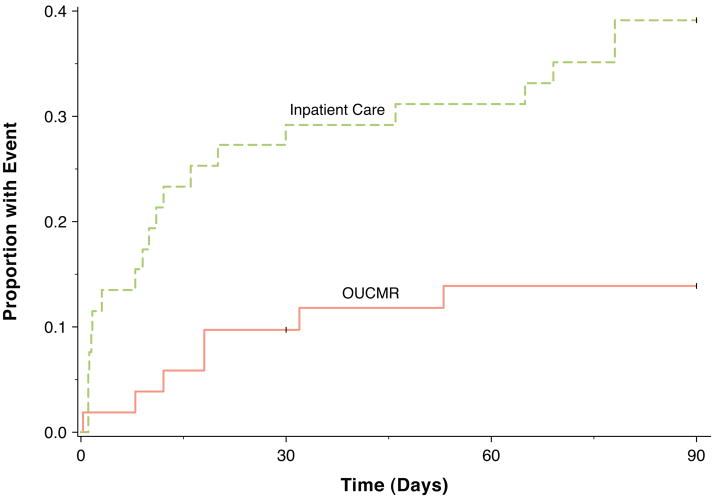

The primary outcome composite at 90 days occurred in 20 (38%) of the usual care group and 7 (13%) of the OU-CMR group (Table 5). In the CPH model, usual care was associated with a hazard ratio of 3.4 (95% CI 1.4 – 8.0, p = .006). In inpatient versus OU-CMR participants, cardiac testing after discharge occurred in 9 (17%) vs 2 (4%) (p = .03), revascularization after randomization occurred in 8 (15%) vs 1 (2%) (p = .03), and re-hospitalization in 12 (23%) vs 4 (8%) participants (p = .03). Three protocol-defined safety events occurred, all due to ACS after discharge among usual care subjects.

Table 5.

Study Outcomes and Safety Events Through 90 Days

| Usual care (N=53) | OU-CMR (N=52) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Primary outcome | |||

| Composite§ | 20 (38) | 7 (13) | .004 |

| Revascularization‡ | 8 (15) | 1 (2) | .031 |

| Hospital readmission§ | 12 (23) | 4 (8) | .033 |

| Recurrent cardiac testing§ | 9 (17) | 2 (4) | .028 |

| Secondary outcome | |||

| Index visit length of stay (hours)* | 26.3 (22.7, 44.8) | 21.1 (14.8, 25.2) | <.001 |

| Safety events‡ | |||

| Death (all-cause) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | --- |

| ACS after discharge | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.24 |

| Stress testing adverse events | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | --- |

data presented as median(IQR); Kruskal-Wallis test

Fisher exact test

chi-squared test

Discussion

We found that the OU-CMR care pathway in elevated risk participants is an efficient alternative to inpatient care, and can shorten hospital length of stay, reduce revascularization, recurrent cardiac testing, and hospital readmissions in agreement with trends observed in a prior trial.(5,8) Participants in this trial were consistent with intermediate-risk patients enrolled in other trials based on age, prior cardiac event rates (Table 1)(5,20), and TIMI risk score (Table 2). Reflective of typical care delivered to these patients across the US, the usual care group underwent a wide variety of initial testing modalities; most commonly stress echo (51%) and cardiac catheterization (17%) (Table 3). In this context, an OU-CMR pathway where nearly all participants received stress CMR as the first objective cardiac test appears to improve efficiency and did not incur any safety events through 90 days. (Tables 3 and 4, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence curves.

Cumulative incidence curves demonstrate an early reduction in composite events that continued through 90 days in the OU-CMR group compared to the usual care group. OU, observation unit; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance.

Assessing the net clinical benefit of reducing revascularizations is complicated. Appropriateness criteria for coronary revascularization are intricate and vary based on an individual patient’s clinical data, including angina severity and results from biomarker, invasive, and non-invasive tests.(21) Because all patients cannot receive all possible tests before revascularization, these decisions are made based on available data. The findings from this trial suggest that the order in which tests are conducted, and perhaps the location of care delivery, influences decisions regarding the need for revascularization. From one vantage point, it appears that some OU-CMR participants avoided revascularization without compromising clinical outcomes. From another perspective, the patients receiving revascularization (Table 5) all appear to have critical stenosis justifying intervention. It is unknown whether patients with similar coronary phenotypes were in the OU-CMR group, but the randomized design makes that likely. One interpretation is that in patients with symptoms attributed to unstable angina, stenotic vessels thought to be the cause of the patient’s symptoms may not actually cause inducible ischemia as measured by stress CMR. In these circumstances, appropriateness criteria would support a trial of medical therapy in some patients with single or 2-vessel disease and low-risk findings on non-invasive testing.(21) A similar and related finding is the management of patients with small troponin elevations. Patients with elevated troponin values are often referred for revascularization due to a recognized benefit of an early invasive strategy in patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS, with the largest benefit observed in patients with elevated serum troponin levels.(14) Recently, troponin assays have become more sensitive and myocardial infarction has been redefined to include patients with smaller elevations in troponin.(18) It remains unclear whether data supporting an early invasive strategy in “troponin positive” patients extends to these lower-grade troponin elevations. Mills and colleagues reported the impact of more sensitive troponin assays on mortality.(22) In the two time periods during which low-grade elevations were blinded or revealed to care providers, patients benefited from improved outcomes when the low-grade elevations were revealed. However, the main benefit from the lower troponin threshold appeared to be derived from more aggressive medical therapy, with no significant difference in revascularization rates. In our trial, 5 participants had a peak troponin value above the upper limit of normal and less than 1.0 ng/ml prior to any coronary intervention. Of these “small” elevations, 3 had vasodilator CMR or stress echo as the first test leading to uneventful discharge. These very preliminary findings suggest that highly accurate non-invasive testing may aid the selection of patients for invasive testing and revascularization.

The strengths of this analysis relate to the randomized design, high adherence to the OU-CMR pathway, and rigorous data collection and follow up procedures. In trade-off, our work has limitations. Because of the single-center design, these findings will need to be replicated across multiple centers to ensure external validity of the findings. We did not adjudicate the appropriateness of revascularization and therefore cannot comment on whether the reductions in revascularization would have been classified as appropriate. However, we submit that the absence of events in the short-term makes it unlikely that patients in need of life-sustaining revascularization were deprived of this intervention. Longer-term follow up is being conducted to determine if revascularizations were required after the 90 day period; our prior investigation did not reveal an increase in post-discharge events through 1 year in a similar OU-CMR group.(8) It is possible that our findings relate to an imbalance in ischemic cardiac events among the study groups despite our randomized design. We feel this is less likely because predictors of adverse cardiac events such as the TIMI risk score and initial ECG findings did not differ among groups, and because efficiency gains have now been observed in both of our studies. Additionally, incomplete blinding could have changed patient or care provider behavior despite our attempts to prevent this source of bias. Finally, we cannot specifically comment on safety of the two groups given that events post-discharge were rare. Given that most patients in both groups received serial cardiac biomarkers and objective cardiac testing we feel it is unlikely that the safety of the two approaches differs.

Conclusion

In this single center trial, management of intermediate risk patients with possible ACS in an OU with stress CMR reduces coronary artery revascularization, hospital readmissions, and recurrent cardiac testing without an increase in post-discharge ACS at 90 days.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support provided by NIH/NHLBI grants 1 R21 HL097131-01A1 (Miller), 1 R01 HL076438 (Hundley), Siemens (software support), NIH T-32 HL087730 (Mahler, PI Goff);

Abbreviation List

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- CPH

Cox Proportional Hazards

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- ED

emergency department

- IQR

interquartile range (1st quartile - 3rd quartile)

- TIMI

thrombolysis in myocardial infarction

- OU

observation unit

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: URL http://www.clinicaltrials.gov Unique identifier: NCT01035047

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Chadwick D. Miller, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

L. Douglas Case, Department of Biostatistical Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

William C. Little, Department of Internal Medicine/Cardiology, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Simon A. Mahler, Departments of Epidemiology and Prevention and Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Gregory L. Burke, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Erin N. Harper, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Cedric Lefebvre, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Brian Hiestand, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

James W. Hoekstra, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

Craig A. Hamilton, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

W. Gregory Hundley, Departments of Internal Medicine/Cardiology and Radiology, Wake Forest School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Cury RC, Shash K, Nagurney JT, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance with T2-weighted imaging improves detection of patients with acute coronary syndrome in the emergency department. Circulation. 2008;118:837–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.740597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingkanisorn WP, Kwong RY, Bohme NS, et al. Prognosis of Negative Adenosine Stress Magnetic Resonance in Patients Presenting to an Emergency Department With Chest Pain. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47:1427–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwong RY, Arai AE. Detecting patients with acute coronary syndrome in the chest pain center of the emergency department with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2004;3:25–31. doi: 10.1097/01.hpc.0000116584.57152.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller CD, Hoekstra JW, Lefebvre C, et al. Provider-Directed Imaging Stress Testing Reduces Health Care Expenditures in Lower-Risk Chest Pain Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department/Clinical Perspective. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2012;5:111–118. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.965293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller CD, Hwang W, Hoekstra JW, et al. Stress Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging With Observation Unit Care Reduces Cost for Patients With Emergent Chest Pain: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2010;56:209–219.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Aty H, Zagrosek A, Schulz-Menger J, et al. Delayed enhancement and T2-weighted cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging differentiate acute from chronic myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:2411–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127428.10985.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hundley WG, Morgan TM, Neagle CM, Hamilton CA, Rerkpattanapipat P, Link KM. Magnetic resonance imaging determination of cardiac prognosis. Circulation. 2002;106:2328–33. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000036017.46437.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller CD, Hwang W, Case D, et al. Stress CMR Imaging Observation Unit in the Emergency Department Reduces 1-Year Medical Care Costs in Patients With Acute Chest Pain: A Randomized Study for Comparison With Inpatient Care. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2011;4:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider EC, Leape LL, Weissman JS, Piana RN, Gatsonis C, Epstein AM. Racial Differences in Cardiac Revascularization Rates: Does “Overuse” Explain Higher Rates among White Patients? Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:328–337. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. Optimal Medical Therapy With or Without Percutaneous Coronary Intervention to Reduce Ischemic Burden: Results From the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) Trial Nuclear Substudy 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. Circulation. 2008;117:1283–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis JP, Schreiner G, Wang Y, et al. All-cause readmission and repeat revascularization after percutaneous coronary intervention in a cohort of medicare patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:903–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJLM, et al. The TIMI Risk Score for Unstable Angina/Non-ST Elevation MI: A Method for Prognostication and Therapeutic Decision Making. JAMA. 2000;284:835–842. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollack CV, Jr, Sites FD, Shofer FS, Sease KL, Hollander JE. Application of the TIMI risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome to an unselected emergency department chest pain population. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:13–8. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:e215–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Budoff MJ, Cohen MC, Garcia MJ, et al. ACCF/AHA clinical competence statement on cardiac imaging with computed tomography and magnetic resonance: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians Task Force on Clinical Competence and Training. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:383–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollander JE, Blomkalns AL, et al. Multidisciplinary Standardized Reporting Criteria Task Force Members. Standardized Reporting Guidelines for Studies Evaluating Risk Stratification of ED Patients with Potential Acute Coronary Syndromes 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08. 033. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1331–1340. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon CP, Battler A, Brindis RG, et al. American College of Cardiology key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes: A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Acute Coronary Syndromes Writing Committee) Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Heart Association, Cardiac Society of Australia & New Zealand, National Heart Foundation of Australia, Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions, and the Taiwan Society of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2114–2130. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01702-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farkouh ME, Smars PA, Reeder GS, et al. A Clinical Trial of a Chest-Pain Observation Unit for Patients with Unstable Angina. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1882–1888. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, Smith PK, Spertus JA. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC 2009 Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization: A Report by the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriateness Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology Endorsed by the American Society of Echocardiography, the Heart Failure Society of America, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.005. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:530–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills NL, Churchhouse AMD, Lee KK, et al. Implementation of a Sensitive Troponin I Assay and Risk of Recurrent Myocardial Infarction and Death in Patients With Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011 Mar 23/30;305:1210–1216. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]