Abstract

Purpose

High dose radiation therapy (RT) for intrahepatic cancer is limited by the development of liver injury. This study investigated whether regional hepatic function assessed prior to and during the course of RT using 99mTc-labeled immindodiacetic acid (IDA) SPECT could predict regional liver function reserve after RT.

Methods and Materials

Fourteen patients treated with RT for intrahepatic cancers underwent dynamic 99mTc-IDA SPECT scans prior to RT, during, and one month after completion of RT. Indocyanine green (ICG) tests (a measure of overall liver function) were performed within 1 day of each scan. 3D volumetric hepatic extraction fraction (HEF) images of the liver were estimated by deconvolution analysis. After co-registration of the CT/SPECT and the treatment planning CT, HEF dose-response functions during and post-RT were generated. The volumetric mean of the HEFs in the whole liver was correlated with ICG clearance time. Three models, Dose, Priori and Adaptive models, were developed using multivariate linear regression to assess whether the regional HEFs measured before and during RT helped predict regional hepatic function post-RT.

Results

The mean of the volumetric liver HEFs was significantly correlated with ICG clearance half-life time (r = −0.80, p<0.0001), for all time points. Linear correlations between local doses and regional HEFs one month post-RT were significant in 12 patients. In the priori model, regional HEF post-RT was predicted by the planned dose and regional HEF assessed prior to RT (R=0.71, p<0.0001). In the adaptive model, regional HEF post-RT was predicted by regional HEF re-assessed during RT and the remaining planned local dose (R=0.83, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

99mTc-IDA SPECT obtained during RT could be used to assess regional hepatic function and helped predict post-RT regional liver function reserve. This could support individualized adaptive radiation treatment strategies to maximize tumor control and minimize the risk of liver damage.

Keywords: 99mTc-IDA SPECT, Hepatic extraction fraction, intrahepatic cancer, radiation-induced liver disease, radiation toxicity

Introduction

High-dose radiation therapy (RT) combined with chemotherapy seems to prolong the survival of patients with intrahepatic cancers (1, 2). However, high-dose RT is limited by the development of radiation-induced liver disease (RILD) (3), a constellation of anicteric ascites, hepatomegaly, and elevated liver enzymes, which can occur 2 weeks to 4 months after the completion of RT. In severe cases, RILD can lead to liver failure and death (3). Currently, there is no effective treatment for RILD.

Assessment of liver function reserve prior to and during RT might allow safer delivery of high doses for better tumor control. Considering that regional liver dysfunction most likely occurs in patients who have hepatocellular carcinoma with cirrhosis and/or who have had previous liver-directed therapy, it is important to assess regional hepatic function prior to RT and its response during RT, looking to predict liver function reserve after RT. Indocyanine green (ICG) clearance, an overall liver function measure, has been used for planning of hepatectomy and liver transplantation (4), and explored for its role in management of the risk of liver injury in RT (5). However, its use cannot provide spatial distributions of hepatic function, which would be useful for radiation treatment planning.

Recent studies have shown that portal venous perfusion quantified by dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) imaging prior to and during RT has the potential to predict regional liver damage after RT (6, 7). Rather than relying on perfusion as a surrogate of hepatic function, however, regional hepatobiliary function can be directly imaged by SPECT with 99mTc-labeled iminodiacetic acid (IDA), a well-established hepatic function agent (8, 9). The 99mTc-IDA is extracted from the blood by hepatocytes through the dye anion receptor, secreted into the bile canaliculi, and then excreted into the bile ducts (10). Hepatic uptake of IDA is commonly evaluated by the hepatic extraction fraction (HEF) (11). Clinical studies have shown that HEF can discriminate between liver parenchymal dysfunction and common bile duct obstruction (8, 12). Therefore, HEF parametric maps derived from 99mTc-IDA SPECT might be used to assess regional liver function and provide guidance for adaptive radiation therapy.

In this pilot study, we tested the hypothesis that regional hepatic function assessed prior to and during the course of RT by SPECT with an IDA agent of 99mTc-membrofenin could help predict both global and regional function after the completion of RT. We tested this hypothesis on a general patient population with different types of radiation treatment for intrahepatic cancers. We validated the HEF by using a well-established overall liver function measurement (ICG clearance). We explored three predictive models by incorporating local radiation dose, regional hepatic function prior to RT, and regional hepatic function response to the dose received in the early course of RT for prediction of regional hepatic function after therapy.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Radiotherapy

Fourteen patients (1 woman and 13 men, 44-83 years old) with unresectable intrahepatic cancer provided written informed consent and participated in a prospective, IRB-approved study (Table 1). Ten patients had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), three cholangiocarcinoma, and one metastasis to the liver. Six of ten HCC patients had cirrhosis. Three patients were treated with 3D conformal RT, three with intensity-modulated RT, and eight with stereotactic body RT (SBRT) as clinically indicated. Generally, tumors up to 3cm were treated with SBRT, and larger tumors received IMRT in the past 2 years, with the rest receiving 3D conformal RT. Radiation dose for each patient was prescribed by an NTCP model to have a 10% or less risk for development of RILD (13). The median doses were 62 Gy in 1.8-2.5 Gy per fraction for 3D conformal RT, 52 Gy in 2-2.6 Gy per fraction for IMRT, and 33 Gy in 8.5-12 Gy per fraction for SBRT. Ten patients had a 4-week break after 50%-60% of the dose was delivered in order to allow liver tissue recovery from early treatment to minimize the risk of complication. Eight patients had previous liver-directed treatments, including transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation and RT.

Table 1.

Patient Information

| Pt No. | Sex/Age | Pathology | Radiotherapy | Physical Dose (Gy) | T1/2 of ICG clearance (min) | Break during RT |

Previous Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| During RT | End RT | Prior RT | During RT | 1 month after RT | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1* | M/59 | HCC | 3D Conformal | 32.5 | 50 | 8.59 | 10.55 | 10.44 | no | TACE / Radioembolization |

| 2 | M/72 | HCC | SBRT | 40 | 50 | 5.00 | 4.00 | 4.50 | no | none |

| 3 | M/54 | cholangiocarcinoma | 3D Conformal | 36 | 62 | 4.50 | 4.25 | 4.75 | no | none |

| 4* | M/60 | HCC | SBRT | NA | 30 | 9.95 | NA | 11.31 | yes | TACE / RFA |

| 5 | M/72 | HCC | IMRT | 32.5 | 50 | 5.07 | 6.24 | 6.19 | yes | none |

| 6* | M/73 | HCC | SBRT | 40 | 50 | 4.68 | 5.82 | 6.56 | yes | TACE |

| 7 | M/71 | cholangiocarcinoma | 3D Conformal | 36 | 64.8 | 5.26 | 4.75 | 5.25 | yes | none |

| 8* | M/67 | HCC | SBRT | NA | 30 | 13.96 | NA | 14.64 | yes | RFA |

| 9 | F/66 | cholangiocarcinoma | IMRT | 36 | 54 | 4.68 | 4.15 | 4.37 | no | none |

| 10* | M/61 | HCC | SBRT | 22 | 33 | 11.83 | NA | 11.27 | yes | TACE / RFA |

| 11 | M/44 | HCC | IMRT | 26 | 52 | 11.31 | 4.07 | 7.27 | yes | none |

| 12 | M/83 | HCC | SBRT | 8.5 | 17 | 5.06 | 5.29 | NA | yes | TACE |

| 13 | M/58 | esophageal metastasis | SBRT | 36 | 60 | 5.19 | 5.62 | 6.86 | yes | RT |

| 14* | M/59 | HCC | SBRT | NA | 33 | 13.67 | NA | 13.09 | yes | TACE |

HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; ICG: indocyanine green; NA: data not available; TACE: transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; RFA: radiofrequency ablation; RT: radiation therapy.

patient with cirrhosis.

SPECT/CT

Dynamic SPECT scans were performed 1 week prior to RT, after delivery of 50%-60% planned dose, and one month after the completion of RT on a hybrid SPECT/CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA). After fasting 3-4 hours, patients received an intravenous injection of 10 mCi of 99mTc-labeled membrofenin (Choletec, Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ). Dynamic SPECT acquisition started immediately after the injection, and lasted up to 60 minutes. Twenty-seven dynamic volumes (Matrix: 128×128×142; FOV:500×500×355 mm3) were reconstructed by filtered back projection to have temporal resolutions of 15 sec for 1-8 temporal volumes, 30 sec for volume 9-14, 1 min for volume 15-19, 2.5 min for volume 20-21, 5 min for volume 22-24, and 10 min for the last three volumes. A CT scan was subsequently obtained on the same gantry for attenuation correction and patient anatomy image. The SPECT and CT were visually checked to ensure alignment.

Hepatic Extraction Fraction

Hepatic extraction fraction (HEF) was estimated by deconvolution analysis of dynamic SPECT data (11). A volumetric HEF map was estimated voxel-by-voxel throughout the liver. First, the spleen was contoured on the axial CT and transferred onto the SPECT. Then, ~500 voxels with the maximal spleen SPECT activity were thresholded to obtain a vascular input function (VIF). Second, for each liver voxel, an impulse response curve was determined by deconvolution of its time-activity curve with the VIF. The deconvolution was performed by single value decomposition (SVD) (14). Third, an exponential curve was fitted to the impulse response function between 7 min and 30 min by least-squares, and then was extrapolated to the peak time of the impulse response function. Finally, the HEF was calculated as a ratio of the initial hepatocyte activity from the exponential curve to the vascular activity peak from the impulse response function (11). For the voxels with HEF greater than one, due to noise or other image artifacts, HEF was set to one for further analysis.

Validation of HEF

HEF quantification was validated by ICG clearance, an established measure of overall liver function. ICG tests were performed at +/−1 day of each SPECT/CT scan. Immediately after bolus administration of ICG dye (0.5 mg/kg), blood samples (~6 ml) were drawn at time 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 min. The half-life time (T1/2) of ICG clearance was determined from evaluation of ICG concentration in the serum samples. We calculated the mean of the voxelwise HEFs in the liver excluding the gross tumor volume . A correlation between and ICG T1/2 was assessed by Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

HEF Dose-Response Function

To evaluate the relationship between local radiation dose and regional HEF function change, we mapped the planned radiation dose distribution onto the HEF images through rigid-body co-registration of each CT (from the SPECT/CT) to the treatment planning CT by using in-house Functional Image Analysis Tool (FIAT). The dose to the normal liver was converted to 2-Gy equivalent per fraction using the linear quadratic approach with an α/β ratio of 2.5 Gy (15). Then, the liver volume, excluding the GTV and large vessels, was segmented into subvolumes at 4 Gy intervals. To avoid partial volume effects, volumes within two voxels from the liver boundary were also excluded from analysis. The average doses and HEFs in each of the dose-defined subvolumes were calculated for each time point to determine the HEF dose response function.

Predictive models for post-RT HEF

We tested three models for predicting the regional HEF one month after RT. First, we modeled regional HEF one month after RT based upon the planned dose distribution alone (Dose Model) as:

| (1) |

where HEFi, j, post is the mean HEF in region j (defined by dose intervals of every 4 Gy) of the liver of patient i (i=1,…,14) one month post RT, and Dosei,j is the mean planed dose at region j, α is the slope and β is the intercept. In the second model (Priori Model), we added the regional HEF measured prior to RT as:

| (2) |

where HEFi, j, pre is the mean HEF in region j (defined by dose intervals of every 4 Gy) of the liver of patient i pre RT. In the third model (Adaptive model), we considered the regional HEF re-assessed during the mid-course of RT as a response to the initial dose, and the remaining planned but undelivered local (regional) dose (dosei,j,rem) as:

| (3) |

where HEFi,j,mid is the mean HEF in region j for patient i measured during the mid-course of RT, and γ, η, μ and ν were model parameters. Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed by using statistical analysis package R (16), and a two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. The difference between the first two models was evaluated by F statistics for nested models.

Results

Validity of HEF Derived from SPECT

A total of 36 pairs of ICG and HEF measurements were obtained from the 14 patients. The median of the volume-averaged HEFs changed from 0.75 (range: 0.46 – 0.88) before RT to 0.66 (range: 0.43 – 0.86) one month post RT. The median ICG T1/2 changed from 5.23 min (range: 4.50 - 13.96 min) to 6.71 min (range: 4.37- 14.64 min). No patients developed RILD after the completion of RT. The volumetric means of HEF were linearly and significantly correlated with ICG T1/2 (r = −0.8, p<0.0001, Figure 1) suggesting the spatially-resolved HEF derived from 99mTc-IDA SPECT can measure regional liver function.

Figure 1.

Correlation between the volumetric mean HEF in the liver () and the ICG clearance half-life time (T1/2). The data from pt #11 prior to RT (red arrow) deviated from the correlation trend. This patient had portal venous thrombosis prior to RT, which improved after RT.

Individual Liver Function Prior to RT

Given that patients with poor liver function are at high risk for liver injury after irradiation, we assessed the overall and regional liver function of patients prior to RT. Five of six patients (pt#1, #4, #8, #10 and #14) with HCC and cirrhosis had low overall liver function prior to RT, with volumetric-weighted means of HEFs below 0.6 (range: 0.46-0.56), and T1/2s of ICG clearance longer than 8 min (range: 8.59-13.67 min). One patient (pt#11, HCC with portal vein thrombosis but without cirrhosis) had a prolonged T1/2 (11.31 min) but a relatively normal (0.77) before RT. The remaining patients had relative normal liver function prior to RT, with the T1/2 range of 4.5-5.19 min and of 0.67-0.88.

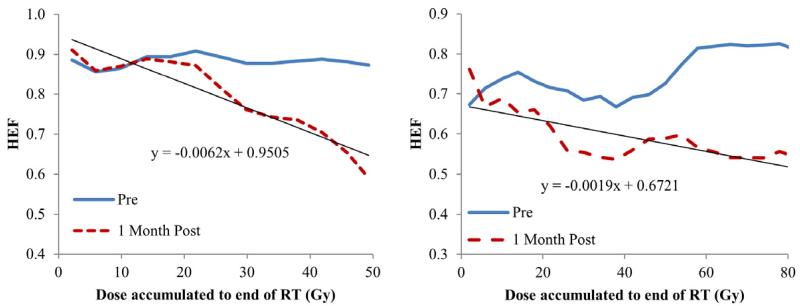

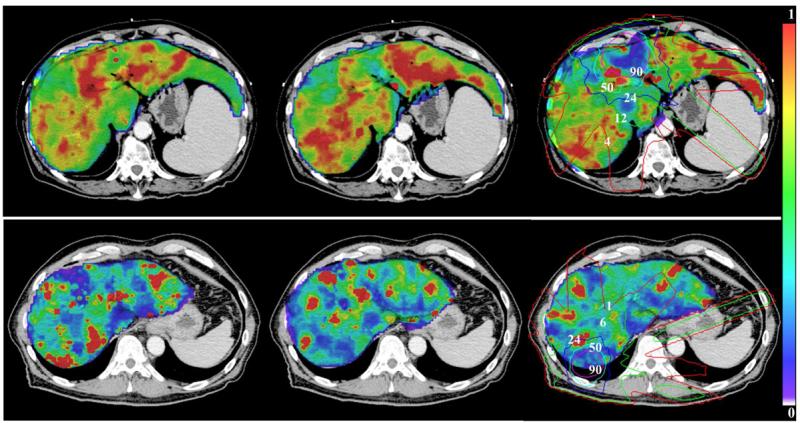

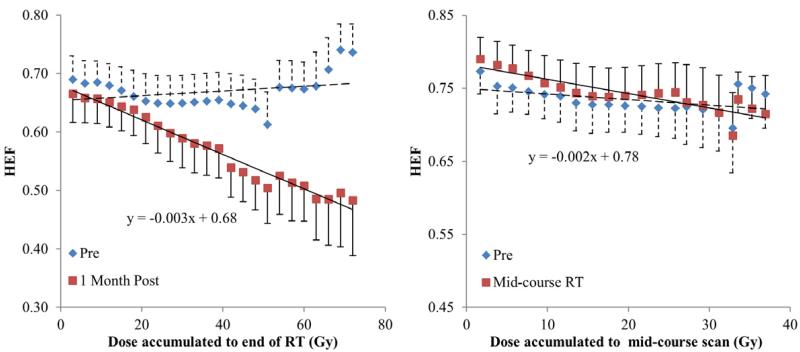

Individual Regional HEF Dose-Response Function

When evaluating regional HEF dose-response in individual patients, all the patients had a linear and significant correlation between local dose and regional HEF one month after RT (linear regression, p<0.05), except pt#2 and #12, who were treated by SBRT and might be less sensitive to radiation. The slopes of the linear regression lines (interpreted as HEF reduction per Gy) ranged from 0.14%/Gy to 0.67%/Gy with a median of 0.32%/Gy (Figures 2 and 3), indicating individual radiation sensitivity. When considering all patients as a group (by averaging the regional HEF dose-response functions), every Gy reduced approximately 0.33% of HEF one month after RT (Figure 4a). Also, the regions receiving 40 Gy or greater showed significant reduction in HEF one month after RT compared to pre RT (p<0.05). When evaluating the averaged regional HEFs measured during RT, there was a linear correlation between regional HEF and local dose accumulated up to the time of scan (r = −0.79, p=0.004, Figure 4b).

Figure 2.

Individual HEF Dose response functions one month after RT from two patients (left: pt #6; right: pt #9).

Figure 3.

Color-coded HEF pre (left), during (mid) and one month after RT (right) overlaid on the treatment planning CT for two patients (Top: pt #6; bottom: pt #10). A reduction in the HEF one month after RT can be seen in the subvolume receiving greater than 50 Gy. Isodose lines (Gy) are indicated on the right panels.

Figure 4.

Average HEF dose response functions of all the patients one month after RT (left) and during the mid-course of RT (right). The curves are generated by averaging HEF dose-response functions over all the patients within each dose interval.

Predictive models for post-RT regional HEF

We investigated three models for prediction of regional HEF one month after RT. In the first Dose Model, the local dose accumulated to the end of RT was a significant predictor for the regional HEF measured one month after RT (R=0.27, p<0.0001, Table 2). In the second Priori Model, both the regional HEF assessed before RT and the local dose accumulated to the end of RT were significant predictors for the regional HEF one month after RT (R=0.71, p<0.0001). Compared to the Dose model, adding the individual baseline regional liver function in the second model significantly improved its predictive power (ANOVA, p<0.0001). Finally, in the third adaptive model, the regional HEF measured during RT and the remaining undelivered dose were significant predictors for the regional HEF one month after RT (R=0.83, p<0.0001), in which goodness fitting was improved compared to the second model, suggesting that it is important to assess the individual and regional HEF response to the initially delivered dose.

Table 2.

Predictive Models for liver function post RT

| Dose Model: HEFi, j, post = αDosei, j + β | (R=0.27, p<0.0001) | |||

|

| ||||

| Coefficient | Std. Error | t value | P-value | |

| Intercept (β) | 0.661 | 0.023 | 29.286 | < 0.0001 |

| Dose (α) (Gy) | −0.002 | 0.001 | −4.248 | < 0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Priori Model: HEFi, j, post = γHEFi, j, pre + ηDosei, j + β | (R=0.71, p<0.0001) | |||

|

| ||||

| Coefficient | Std. Error | t value | P-value | |

| Intercept (β) | 0.085 | 0.045 | 1.912 | 0.057 |

| HEFpre (γ) | 0.870 | 0.063 | 13.904 | < 0.0001 |

| Dose (η) (Gy) | −0.003 | 0.000 | −6.748 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||

| Adaptive Model: HEFi, j, post = μHEFi, j, mid + νDosei, j,rem + β | (R=0.83, p<0.0001) | |||

|

| ||||

| Coefficient | Std. Error | t value | P-value | |

| Intercept (β) | 0.149 | 0.030 | 4.998 | <0.0001 |

| HEFmid (μ) | 0.784 | 0.043 | 18.384 | <0.0001 |

| Doserem (ν) (Gy) | −0.004 | 0.001 | −4.492 | <0.0001 |

HEFpre: HEF pre RT; HEFmid: HEF during the mid-course of RT; Dose: planned dose; Doserem: remaining dose after the mid-course of RT.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the hepatic function distribution in the patients with intrahepatic cancers prior to, during, and one month after the completion of RT by 99mTc-IDA SPECT. We validated the HEF derived from 99mTc-IDA SPECT by using a well-established overall liver function measurement of ICG clearance. We found that prediction of the regional HEF one month after the completion of RT could be improved by incorporating the regional HEF measured prior to or during the early course of RT into the dose-based model. These findings indicate that baseline individual regional liver function should be considered in initial treatment planning, particularly for patients at high risk for liver injury, e.g., patients with HCC and cirrhosis and/or with previous liver-directed interventions. Most importantly, our findings suggest that the individual and regional dose-response of liver function assessed during the early course of RT could be used to re-adjust both the total dose and the dose distribution for the remaining treatment. These strategies have the potential to aid in optimizing both the safety and efficacy of radiation therapy for intrahepatic cancers.

Hepatobiliary function SPECT with 99mTc-IDA has been demonstrated to play an important role in the diagnosis of liver disease (8, 9, 17). In this study, we validated the extracted HEF from IDA SPECT using the ICG clearance test for patients who a) had both primary and metastatic cancers; b) showed a broad range of liver function (ICG T1/2 from 4.00 min to 14.64 min); and c) were treated by various types of RT. In one patient (#11) with portal vein thrombus, the relationship did not hold. This is because a thrombus can substantially affect hepatic blood flow and the ICG clearance rate, even though the hepatic extraction function can remain normal. In this patient, when the tumor size was reduced by RT and the portal vein flow was improved, the ICG clearance rate improved. Clinical routine blood “liver function” tests have limited roles for assessment and prediction of hepatic function response to radiation doses, possibly due to that many other factors affect these tests. However, bilirubin levels had significant correlation with the mean HEFs (r=−0.54, 21 pair data points available), but weaker than ICG clearance. Finally, the regional and total HEF determined by 99mTc-IDA SPECT provide important information for decision making regarding total dose and, potentially, beam arrangement.

In the past, models to predict the likelihood of developing RILD have been primarily based on population data of radiation dose distribution in the normal liver (18, 19). The mean liver dose has shown to be a useful parameter to estimate the risk of developing RILD. To improve the predictive power of the dose-based NTCP models, clinical factors such as tumor type, tumor volume and previous treatments have been examined in the models (13). These factors that provide information regarding preexisting conditions of patients cannot reflect individual sensitivity to radiation, which could be due to genetic and environmental factors. In this study, we found that the majority of patients with HCC and cirrhosis had a low HEF prior to RT. We found that combining the regional HEF prior to RT with total planned local dose improved prediction of the regional HEF one month after RT compared to using the dose alone. Incorporating the individual and regional dose-response of HEF assessed during the early course of RT further improved prediction of the post-RT regional HEF. These findings suggest that it would be possible to design a strategy for planning and adapting the individual therapy based upon individual liver function prior to RT and mid-course response. This strategy could overcome the dilemma in the population-based treatment plan, in which the 10% of patients who are the most sensitive to radiation limit the dose for all patients.

This study has several limitations. First, as the dynamic SPECT scans last 60 min, respiratory motion between temporal volumes may induce errors in HEF estimation. Second, dose was mapped onto the HEF volumes by rigid-body registration of SPECT/CT to the treatment planning CT without considering morphological changes of the liver between scans. In this study, we visually examined each registration. However, we used the volumetric mean HEF and mean dose in the dose-binned subvolumes (with a size of 2 cc or greater) for analysis, which has a greater tolerance to possible mis-alignment between the HEF volume and the dose distribution.

Our results form the foundation for replanning radiation treatment midway through therapy for patients with intrahepatic cancers. The strategy has shown promise in the treatment of lung cancer (20). In that study, patients undergo an FDG-PET scan during treatment, and radiation therapy are replanned to increase dose to the FDG-PET avid region, which harbors active disease, while maintaining a standard dose (60 Gy in 2 Gy fractions) to the rest of the tumor. This concept is now being tested in a multi-institutional trial (RTOG 1106). Our results from the current study suggest that is may also be possible to use the converse approach. By replanning radiation treatment midway through treatment to increase dose to regions of the liver that are not contributing to liver function (and, thereby, sparing functional parts), we anticipate that we can substantially increase the safe dose of radiation to an intrahepatic cancer for most patients. Based on our finding that local control correlates with dose (1), we would anticipate that this approach would increase control rates. The development of such a clinical trial is currently underway.

Summary.

We performed 99mTc-labeled iminodiacetic acid (IDA) SPECT and indocyanine green clearance tests before, during, and after radiotherapy for intrahepatic tumors, with the hypothesis that we could predict regional hepatic function reserve post-RT. Three models were tested; the best was the Adaptive model, which included dose and during-RT regional function. Changes in imaging detected during RT could guide individualized mid-course adaptation to maximize tumor control and minimize the risk of liver damage.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by RO1CA132834.

This work was presented at the 2012 AAPM annual meeting and will be presented at the 2013 Cancer Imaging and Radiation Therapy Symposium.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ben-Josef E, Normolle D, Ensminger WD, et al. Phase II trial of high-dose conformal radiation therapy with concurrent hepatic artery floxuridine for unresectable intrahepatic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.5354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson LA, McGinn CJ, Normolle D, et al. Escalated focal liver radiation and concurrent hepatic artery fluorodeoxyuridine for unresectable intrahepatic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2210–2218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence TS, Robertson JM, Anscher MS, et al. Hepatic toxicity resulting from cancer treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31 doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00418-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemming AW, Scudamore CH, Shackleton CR, et al. Indocyanine green clearance as a predictor of successful hepatic resection in cirrhotic patients. Am J Surg. 1992;163:515–518. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(92)90400-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon HI, Koom WS, Lee IJ, et al. The significance of ICG-R15 in predicting hepatic toxicity in patients receiving radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2012;32:1165–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2012.02784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Y, Pan C, Balter JM, et al. Liver function after irradiation based on computed tomographic portal vein perfusion imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y, Wang H, Johnson TD, et al. Prediction of Liver Function by Using Magnetic Resonance-based Portal Venous Perfusion Imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aburano T, Yokoyama K, Shuke N, et al. The role of Tc-99m IDA hepatobiliary and Tc-99m colloid hepatic imaging in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Nucl Med. 1991;16:4–9. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonas E, Naslund E, Freedman J, et al. Measurement of parenchymal function and bile duct flow in primary sclerosing cholangitis using dynamic 99mTc-HIDA SPECT. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:674–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan J, Cooper M, Loberg M, et al. Technetium-99m-labeled n-(2,6-dimethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl) iminodiacetic acid (tc-99m HIDA): a new radiopharmaceutical for hepatobiliary imaging studies. J Nucl Med. 1977;18:997–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juni JE, Reichle R. Measurement of hepatocellular function with deconvolutional analysis: application in the differential diagnosis of acute jaundice. Radiology. 1990;177:171–175. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.1.2399315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michael M, Thompson M, Hicks RJ, et al. Relationship of hepatic functional imaging to irinotecan pharmacokinetics and genetic parameters of drug elimination. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4228–4235. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson LA, Normolle D, Balter JM, et al. Analysis of radiation-induced liver disease using the Lyman NTCP model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:810–821. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02846-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsson H, Nordell A, Vargas R, et al. Assessment of hepatic extraction fraction and input relative blood flow using dynamic hepatocyte-specific contrast-enhanced MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:1323–1331. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barendsen GW. Dose fractionation, dose rate and iso-effect relationships for normal tissue responses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982;8:1981–1997. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(82)90459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.R Development Core Team. R . A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roca I, Ciofetta G. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy in current pediatric practice. Q J Nucl Med. 1998;42:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim TH, Kim DY, Park JW, et al. Dose-volumetric parameters predicting radiation-induced hepatic toxicity in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence TS, Tesser RJ, ten Haken RK. An application of dose volume histograms to the treatment of intrahepatic malignancies with radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90031-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng M, Kong FM, Gross M, et al. Using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to assess tumor volume during radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer and its potential impact on adaptive dose escalation and normal tissue sparing. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:1228–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]