Abstract

Background

The default mode network (DMN), a brain system anchored in the posteromedial cortex, has been identified as under-connected in adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, to date there have been no attempts to characterize this network and its involvement in mediating social deficits in children with ASD. Furthermore, the functionally heterogeneous profile of the posteromedial cortex raises questions regarding how altered connectivity manifests in specific functional modules within this brain region in children with ASD.

Methods

Here we use resting-state fMRI and an anatomically informed approach to investigate the functional connectivity of the DMN in 20 children with ASD and 19 age-, gender-, and IQ-matched typically developing children. We utilize multivariate regression analyses to test whether altered patterns of connectivity are predictive of social impairment severity.

Results

Compared to TD children, children with ASD demonstrated hyper-connectivity of the posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortices with predominately medial and anterolateral temporal cortex. In contrast, the precuneus in ASD children demonstrated hypo-connectivity with visual cortex, basal ganglia, and locally within the posteromedial cortex. Aberrant posterior cingulate cortex hyper-connectivity was linked with severity of social impairments in ASD, whereas precuneus hypo-connectivity was unrelated to social deficits. Consistent with previous work in healthy adults, we observe a functionally heterogeneous profile of connectivity within the posteromedial cortex in both TD and ASD children.

Conclusions

This work links hyper-connectivity of DMN-related circuits to the core social deficits in young children with ASD and highlights fundamental aspects of posteromedial cortex heterogeneity.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorders, default mode network, posteromedial cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, functional connectivity, resting-state fMRI

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by profound deficits in social behaviors and affects 1 in 88 children (1). These impairments encompass multiple forms of social cognition, including both interpersonal social processes and self-referential thought (2, 3). These social and self-referential cognitive processes have been linked with a pair of cortical midline brain regions, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), which serve as hubs of the default mode network (DMN) (4, 5). The VMPFC is involved in mentalizing or theory of mind, person perception, and representation of self-knowledge (6). The PCC, with its strong connections to medial temporal lobe systems, has been linked with episodic and autobiographical memory retrieval (7), visuo-spatial mental imagery, prospection, and self-projection (8). Although the DMN is typically attenuated in the context of task performance (5), regions belonging to this network are often engaged during social tasks (9, 10). This overlap between the DMN and nodes of the “social brain” has led to the proposal that the DMN is strongly associated with social cognition (11–13).

Motivated by the potential link between DMN function and social deficits in ASD, several studies have investigated DMN activation and connectivity in adults and adolescents with the disorder (14–18). Task-induced “deactivations” of the anterior midline DMN node has been reported as absent in adults with ASD relative to controls (16). Subsequent resting-state fMRI studies have identified altered DMN connectivity in adults and adolescents with ASD using both region-of-interest (ROI) and independent component analysis approaches (14–18). These studies collectively suggest that functional connectivity of the DMN is reduced in adults and adolescents with the disorder, with the exception of one investigation that identified a more complex pattern of both reduced and increased connectivity (17). At present, however, there are no published studies examining intrinsic functional connectivity of the DMN in childhood ASD. The only comparable study is a recently published paper by Rudie and colleagues reporting reduced connectivity between the PCC and MPFC in a mixed group of children and adolescents with ASD (19). We have recently found that, contrary to what has been reported in adults and adolescents, childhood ASD may be characterized by greater instances of hyper-connectivity than hypo-connectivity (20, 21). This underscores the need for studying age groups that are tightly restricted, rather than those that may encompass several distinct developmental stages.

Several critical questions regarding the nature of DMN integrity in ASD remain unaddressed. First, since ASD is a disorder with early life onset and variable developmental trajectory, it is important to understand how DMN connectivity manifests in young children with the disorder. Currently very little is known regarding network development in ASD. However, recent work examining the structural and functional connectivity within the DMN in healthy children and adults (22–24) has highlighted significant changes in this network with development. Therefore, findings in adolescents and adults with ASD may not be directly relevant to understanding the DMN in childhood ASD. Second, considering recent findings of posteromedial cortex (PMC) heterogeneity (25), specifically between the precuneus and the more ventral posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortices, it is possible that previous studies have missed critical nodes of the DMN, thereby potentially misrepresenting the network. Third, it is not known if aberrant DMN-related circuits are associated with social behavioral deficits in children with ASD.

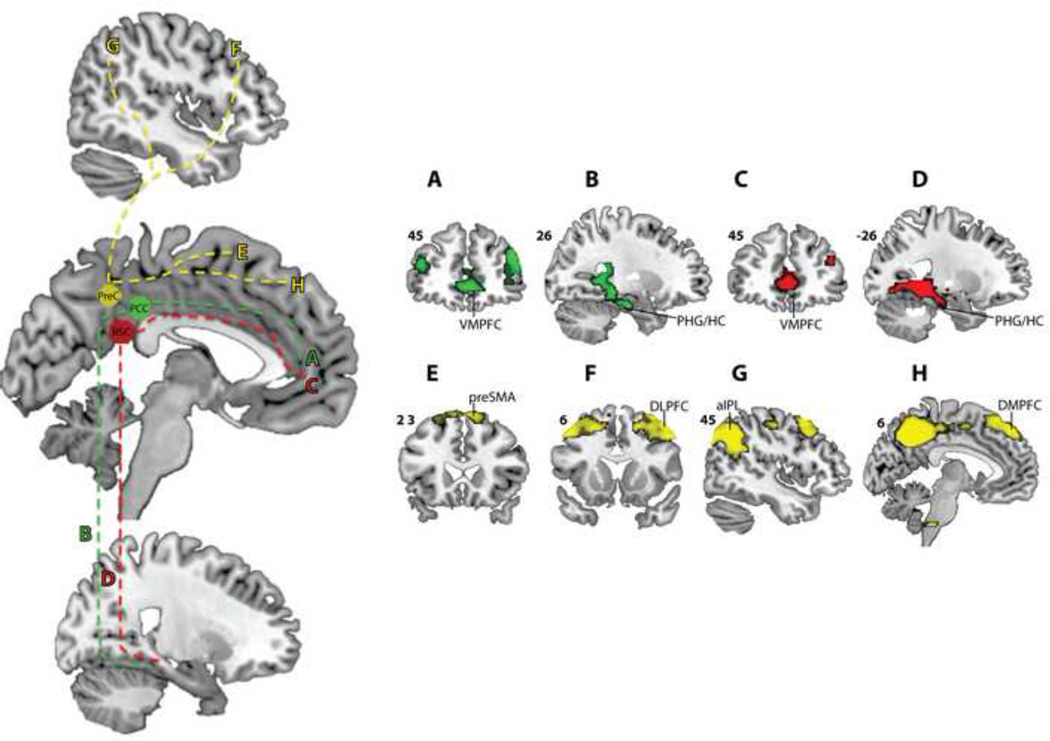

Inadequate attention to the neuroanatomy of the PMC is a potential limitation of previous clinical studies of the DMN. Anatomically, the DMN consists of prominent nodes in the PCC, retrosplenial cortex (RSC), angular gyrus, VMPFC, and both anterolateral and medial aspects of the temporal lobe (4, 11). The PMC collectively encompasses the PCC, RSC and precuneus (26) (Figure 1A). Converging evidence from tracing studies in non-human primates (27, 28) and resting-state fMRI connectivity studies in both adult humans and primates (25) have revealed that the PCC, RSC, and precuneus while all interconnected, each demonstrate unique patterns of anatomical and functional connectivity, suggesting the presence of distinct functional modules within the PMC (26). Importantly, these studies suggest that both the PCC and RSC have robust anatomical and functional connections with other key nodes of the DMN, particularly with VMPFC and the medial temporal lobe areas (25, 28, 29) (Figure 1C, D). In contrast, the precuneus has stronger connectivity with dorsolateral prefrontal, supplementary motor, and occipital regions (25) (Figure 1E). Based on these differences in connectivity and neuroanatomy of PMC sub-regions it has been proposed that the ventral PMC, consisting of the PCC and RSC, is the core posterior midline node of the DMN, rather than the neighboring precuneus (11, 25).

Figure 1.

Summary of posteromedial cortex anatomy and connectivity based on the work of Margulies and colleagues (25). The posteromedial cortex (PMC) (A) encompasses the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), retrosplenial cortex (RSC), and precuneus (PreC) (B). Ventral aspects of the PMC, including the PCC (C) and RSC (D), have strong connections with medial temporal lobe (MTL) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC). The PreC (E) has stronger connections with dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), supplementary motor (SMA), and occipital regions. cc = corpus callosum, cs = cingulate sulcus, pof = parieto-occipital sulcus, sps = sub-parietal sulcus.

Despite anatomical and functional evidence suggesting that the ventral PMC is the most representative posteromedial cortical node of the DMN, studies of putative DMN connectivity have not clearly delineated these nodes from dorsal regions within the PMC. DMN studies have reported atypical functional connectivity in both adolescents (18) and adults (17, 30) with ASD using identical region-of-interest (ROI) coordinates as starting points for functional connectivity analyses. Curiously, in both cases, the seed coordinates used in these connectivity analyses were reported as selected from a previous meta-analysis of task-deactivated regions (31), (32) and correspond more closely to the ventral precuneus, rather than the PCC proper. In light of this recent literature demonstrating functional heterogeneity within the PMC in normal healthy adults (33, 34) and evidence for robust PCC functional and anatomical connectivity with core DMN components (25, 28, 29), DMN connectivity in ASD should be reassessed.

The current study addresses these open questions regarding the nature of DMN connectivity in childhood ASD and provides insights into the aberrant functional organization of brain systems mediating social cognitive deficits in ASD. We utilize precisely defined ROIs in the PCC, RSC and precuneus, encompassing the dorsal and ventral aspects of the PMC, to assess DMN connectivity in children with ASD. Additionally, we examine the relationship between aberrant DMN connectivity and social behavioral deficits in childhood ASD.

METHODS

Participants

The Stanford University Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols. Children were recruited from schools and clinics near Stanford University. All children were required to have a full-scale IQ > 70, as measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). A group of 20 children aged 7–12 years old who met criteria for ASD on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al., 1994) or criteria for autism on the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) (Lord et al., 2000) were included in the study. Participants were matched on full-scale IQ, age, and gender with a group of 20 typically developing (TD) children aged 7–12 years (Table 1). Table S1 in the Supplement contains additional clinically relevant information on the ASD sample. One TD participant was excluded from the analysis due to issues related to data quality. The final group consisted of 20 children with ASD and 19 TD children.

Table 1.

Participant demographics. ADOS = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, ADI = Autism Diagnostic Interview. RMS = root mean square.

| ASD (n = 20) | TD (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 9.96 ± 1.59 (7–12 years old) | 9.88 ± 1.61 (7–12 years old) |

| Gender | 16 M, 4 F | 15 M, 4 F |

| Full-scale IQ | 112.6 ± 17.8 | 112.2 ± 15.8 |

| ADOS Social | 8.2 ± 2.1 | |

| ADOS Communication | 3.6 ± 1.5 | |

| ADI Social | 20.4 ± 5.4 | |

| ADI Communication | 15.9 ± 5.1 | |

| ADI Repetitive Behaviors | 5.8 ± 2.5 | |

| Movement (RMS) | 0.33 mm ± 0.23 | 0.30 mm ± 0.24 |

Data Acquisition

Functional MRI

Functional images were acquired on a 3T GE Signa scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) using a custom-built head coil. For the resting state fMRI scan, subjects were instructed to keep their eyes closed and try not to move for the duration of the six-minute scan. Head movement was further minimized by memory foam pillows placed around the participant’s head. A total of 29 axial slices (4.0 mm thickness, 0.5 mm skip) parallel to the AC-PC line and covering the whole brain were imaged using a T2* weighted gradient echo spiral in-out pulse sequence (35) with the following parameters: TR = 2000 msec, TE = 30 msec, flip angle = 80°, 1 interleave. The field of view was 20 cm, and the matrix size was 64×64, providing an in-plane spatial resolution of 3.125 mm. Reduction of blurring and signal loss arising from field inhomogeneities was accomplished by the use of an automated high-order shimming method prior to data acquisition.

fMRI Data Analysis

fMRI Preprocessing

A linear shim correction was applied separately for each slice during reconstruction using a magnetic field map acquired automatically by the pulse sequence at the beginning of the scan (35). Functional MRI data were then analyzed using SPM8 analysis software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Images were realigned to correct for motion, corrected for errors in slice timing, spatially transformed to standard stereotaxic space (based on the MNI coordinate system), resampled every 2 mm using sinc interpolation and smoothed with a 6 mm full-width half-maximum Gaussian kernel to decrease spatial noise before statistical analysis. Translational movement in millimeters (x, y, z) and rotational motion in degrees (pitch, roll, yaw) was calculated based on the SPM8 parameters for motion correction of the functional images in each subject.

Region of Interest Selection

ROI coordinates were selected from a seminal study by Margulies and colleagues that identified heterogeneous patterns of intrinsic brain connectivity across the PMC in both neurotypical adults and non-human primates (25). We included coordinates corresponding to the PCC ROI (MNI coordinates x= −2, y = −36, z = 35), RSC (MNI coordinates x= −3, y = −45, z = 23) and precuneus (MNI coordinates x= −2, y = −51, z = 41). Each ROI consisted of a sphere with a 6mm radius. The precuneus seed used in our study overlaps closely with the ventral precuneus seed (MNI coordinates x= −5, y = −53, z = 41) used in previous reports investigating DMN connectivity in adults and adolescents with ASD (17, 18, 30).

Functional Connectivity Analysis

For each ROI, a resting-state time series was extracted by averaging the time series of all voxels within it. The resulting ROI time series was then used as a covariate of interest in a linear regression whole-brain analysis. A global time series, computed across all brain voxels, along with 6 motion parameters, were used as additional covariates to remove confounding effects of physiological noise and participant movement (see Figure S3 in the Supplement for group differences after alternative cerebrospinal fluid and white matter regression analysis). Data was bandpass filtered (low pass 0.008 Hz, high pass 0.1 Hz). Group-level and between ROI connectivity maps were generated using t-tests of individual functional connectivity contrast images. Between group and between ROI functional connectivity maps were thresholded at p < 0.01 for height and a family wise error (FWE) corrected cluster extent p < 0.05 (corresponding to a minimum cluster size of 100 voxels). Combined group (ASD & TD) functional connectivity maps for each ROI were thresholded at FWE p < 0.0001 height and a 100 voxel cluster extent. To demonstrate the robustness of our findings against potential movement confounds we performed several analyses (see Tables S3 and S4 in the Supplement), including the “scrubbing procedure” proposed by Power and colleagues (see Figure S2 in the Supplement).

Multivariate Regression Analysis of Connectivity and Clinical Symptoms

To investigate whether connectivity between PMC ROIs and their associated group difference targets predicted social symptom severity in ASD, we used a sparse regression algorithm (36). The sparse regression algorithm identifies connections that predict symptom severity by modeling the relationship between the dependent variable (score on specified domain of ADOS/ADI-R) and the independent variables (strength of connectivity between seed ROI and peak coordinates generated from group differences). Please see Supplement 1 for a detailed description of the sparse regression analysis.

RESULTS

Differential connectivity of dorsal and ventral posteromedial cortex sub-regions

We first examined the functional connectivity patterns of the PCC, RSC, and precuneus in the combined group (n = 39) of children. Figure 2 demonstrates findings of heterogeneity between dorsal (precuneus) and ventral (PCC/RSC) aspects of the PMC. Both the PCC and RSC demonstrated stronger connections with VMPFC and medial temporal lobe DMN nodes compared to the precuneus (Figure 2A, B, C, D). In contrast, the precuneus was most strongly connected with the supplementary motor area (SMA) (Figure 2E), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Figure 2F), anterior inferior parietal lobule (Figure 2G), and dorsal aspects of the medial prefrontal cortex (Figure 2H). See Figure S1 in the Supplement for within-group connectivity maps of the PCC, RSC and precuneus. Information regarding degree of functional unity within the PMC in ASD and TD children is demonstrated in Figure S4 in the Supplement.

Figure 2.

Posteromedial cortex ventral and dorsal sub-regions demonstrate differential profiles of connectivity. Posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortices demonstrated stronger connections with VMPFC and medial temporal lobe DMN nodes compared to the precuneus (A, B, C, D). The precuneus was most strongly connected with the pre-supplementary motor area (preSMA) (E), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (F), anterior inferior parietal lobule (aIPL) (G), and dorsomedial aspects of the medial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC) (H).

Posterior cingulate cortex is hyper-connected in children with ASD

Relative to the TD group, children with ASD showed greater functional connectivity of the PCC with several brain regions (Figure 3A). PCC hyper-connectivity in children with ASD was detected in the anterolateral temporal cortex (middle and inferior temporal gyrus), lingual gyrus, posterior parahippocampal gyrus, temporal pole, and both the entorhinal and perirhinal cortex within the anterior aspect of the medial temporal lobe (MNI coordinates of target regions for each ROI are in Table S2 in the Supplement). There were no brain regions that showed decreased PCC connectivity in the ASD group compared to the TD group.

Figure 3.

Children with ASD demonstrated both hyper-connectivity (ASD > TD) and hypo-connectivity (TD > ASD) of posteromedial cortex sub-regions. The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and retrosplenial cortex (RSC) revealed ASD hyper-connectivity while the precuneus (PreC) demonstrated ASD hypo-connectivity. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001. aLTC = anterolateral temporal cortex, DMPFC = dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, ERc = entorhinal cortex, LG = lingual gyrus, PHG = parahippocampal gyrus, pInsula = posterior insular cortex, PRc = perirhinal cortex, pSTS = posterior superior temporal sulcus, TempP = temporal pole.

Retrosplenial cortex is hyper-connected in children with ASD

Similar to findings revealed by the PCC ROI, children with ASD also demonstrated increased RSC functional connectivity with several brain regions (Figure 3B). RSC hyper-connectivity in children with ASD was detected in the inferior frontal gyrus, middle frontal gyrus, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, posterior insular cortex, lingual gyrus, posterior parahippocampal gyrus, temporal pole, posterior superior temporal sulcus, and anterior supramarginal gyrus. There were no brain regions that showed reduced RSC connectivity in the ASD group compared to the TD group.

Precuneus is hypo-connected in children with ASD

Relative to the TD group, children with ASD showed reduced connectivity of the precuneus locally within the PMC (PCC, RSC, and precuneus), cuneus, as well as with caudate and dorsal medial thalamic nuclei (Figure 3C). There were no brain regions that showed greater precuneus connectivity in the ASD group compared to the TD group.

Relation between altered DMN connectivity and social impairments in children with ASD

To examine how aberrant DMN-related circuits are related to social deficits in children with ASD, we used a multivariate regression analysis (Figure 4). Functional connectivity between each PMC ROI and associated hyper- and hypo-connected target regions were regressed against scores from the social domain of the ADOS. Significant correlations were found between PCC seed targets in the right posterior parahippocampal gyrus, left temporal pole, and left lingual gyrus (R2 = 0.57, p < 0.009). No significant relations were observed for target regions identified by the RSC (R2 = 0.17) or the precuneus (R2 = 0.04).

Figure 4.

Posterior cingulate cortex hyper-connectivity predicts social deficits in ASD. Connections between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) seed region of interest (ROI) and associated ASD hyper-connected target regions were found to be predictive of social impairments as measured by the ADOS social subscale (A). No such significant relationships were demonstrated by the retrosplenial cortex (RSC) and precuneus (PreC)(B). L= left, R= right, n.s. = not significant, * represents significance. PHG = parahippocampal gyrus, TempP = temporal pole, LG = lingual gyrus.

DISCUSSION

The critical issue of how DMN connectivity manifests in young children with ASD and how aberrant connectivity of this network is linked with social behavioral deficits is an open question. Previous investigations of DMN connectivity in ASD have not explored the unique connectivity patterns across PMC modules (25). A novel finding from our study is that the ventral PMC, comprised of the PCC and RSC, demonstrated hyper-connected effects while the precuneus was hypo-connected in children with ASD. These findings highlight the importance of precise anatomical methods and the necessity for studying functional brain connectivity in ASD at earlier time points in development. Studies of typical development suggest that functional brain maturation involves simultaneous pruning of local connectivity and strengthening of long-range connectivity with age (37). While the under-connectivity theory of ASD posits that the disorder can be attributed to reduced synchrony between anterior and posterior brain regions (38), the mixed literature on brain connectivity in ASD has yet to converge on findings obtained from different methods and periods of development (39). Our findings, which oppose canonical brain connectivity theories in adults and adolescents with ASD, highlight the critical importance of studying ASD at earlier time points.

Posteromedial cortex is functionally heterogeneous early in development

Previous work in adults, and convergent findings from the macaque tracing literature, has identified a robust differentiation between the connectivity of ventral and dorsal aspects of the PMC (26, 28). Consistent with this literature, we found that in both ASD and TD children, ventral aspects of the PMC were most tightly connected with key medial prefrontal and temporal DMN nodes. In contrast, the precuneus was more strongly connected with anterior inferior parietal, dorsolateral and dorsomedial prefrontal regions relative to the PCC and RSC. These findings suggest that like in adults, the PMC has a heterogeneous profile of connectivity in children and that anatomically distinct ROIs can be utilized to more precisely map DMN connectivity in both normative and atypical development.

DMN is hyper-connected in children with ASD

We found that the PCC and RSC demonstrated stronger connectivity in children with ASD, compared to TD children. Target brain regions where such differences were noted included several regions belonging to the DMN, including the entorhinal and perirhinal cortex in the anterior medial temporal lobe, the parahippocampal gyrus in the posterior aspect of the medial temporal lobe, anterolateral temporal cortex, and the temporal pole. Although these medial and anterolateral temporal lobe nodes are less often identified as belonging to this network, several studies have highlighted the role of these regions within the DMN (11, 40).

Our findings support an emerging view that the “under-connectivity” theory of ASD may be too simplistic and that numerous variables including point of development, anatomical specificity, and choice of analytic technique (41) may preclude a single global theory of brain connectivity in ASD. This work raises additional questions to be addressed by future studies regarding the developmental trajectory of the DMN, along with other brain systems, in ASD. We are aware of no existing studies, either cross-sectional or longitudinal, that examine the development of brain connectivity in ASD, and suggest that this is an important direction for future work. We speculate that our findings of ASD hyper-connectivity in childhood may represent a stage prior to a critical point in development, perhaps puberty, where unknown mechanisms may facilitate a transition from hyper-connectivity to the reduced connectivity commonly observed in adolescents and adults with the disorder. In other work we have shown that the ASD brain in childhood may be characterized by greater instances of hyper-connectivity than hypo-connectivity (20).

However, considering the complex ASD behavioral phenotype it is very likely that the disorder is characterized by instances of both hyper- and hypo-connectivity, as demonstrated by our present analysis. We speculate that this a complex network phenomena arising from the presence of aberrant local circuits in some brain regions but not others. Multivariate pattern analysis of structural MRI data have revealed that children and adolescents with ASD could be discriminated from typically developing individuals with 92% accuracy based on gray matter in the PCC (3). Furthermore, a recent postmortem study identified altered PCC cytoarchitecture as a characteristic of brains of individuals with autism (42). Taken together, these findings suggest that loci of structural disorganization may underlie specific altered functional circuits in ASD.

Precuneus is hypo-connected in children with ASD

Children with ASD showed decreased functional connectivity of the precuneus locally within the PMC, cuneus, caudate nuclei, and the medial dorsal thalamic nucleus. Our findings of precuneus hypo-connectivity are consistent with previous literature reporting “under-connectivity” of this brain region in adults and adolescents with ASD (17, 18, 30). However, these previous studies identified the medial prefrontal cortex and temporal lobe regions as under-connected with the precuneus in adults with ASD, whereas in the present study under-connectivity of the precuneus in children was seen most robustly with the caudate nucleus. Although precuneus under-connectivity in the present study implicates different targets, the general finding of precuneus under-connectivity in children with ASD suggests a similar direction of effects.

DMN hyper-connectivity and social deficits in childhood ASD

Hyper-connectivity between the PCC and select targets, including the temporal pole, posterior parahippocampal gyrus, and lingual gyrus was associated with increased social behavioral impairments as measured by the ADOS diagnostic assessment (R2 = 0.57, p < 0.009). Social behavioral deficits in the ASD group were specifically linked to aberrant connectivity of the PCC. No significant relationships were found for atypical connectivity patterns associated with the RSC or the precuneus. Since the core regions of the DMN participate in cognitive functions that are of a social nature (9), it is plausible that altered connectivity of this system may contribute to deficits in the social domain in ASD. We propose that this hyper-connectivity may prevent task-relevant communication between the nodes of the DMN.

The temporal pole has been linked with socioemotional processes including theory of mind and face recognition (6, 43). Bilateral temporal pole lesions in primates have demonstrated symptoms similar to those seen in Klüver-Bucy syndrome, a disorder characterized by social withdrawal and blunted affect (43). Additional work observing strong connections between the temporal pole and the VMPFC, PCC/RSC, and parahippocampal gyrus has suggested that these regions collectively are involved with emotional or self-referential processes (44). The posterior parahippocampal gyrus also demonstrated hyper-connectivity related to social impairment severity. The parahippocampal gyrus has also been variably implicated as part of the “medial temporal lobe sub-system” of the DMN (4) and along with the temporal pole has been proposed to be functionally linked with autobiographical memory and semantic memory (45, 46), as well as making decisions about one’s own personal future (40). It has been proposed that these regions comprise a memory system fundamentally linked with social cognition (46). Taken together, our findings suggest that PCC hyper-connectivity with DMN-related circuits not only reflects atypical interactions within one or more networks important for inter- and intrapersonal social cognitive processes, but also is associated with severity of social impairment in children with ASD.

Several limitations of our work must be taken into consideration and addressed by future studies. First, at present there are no comparable studies investigating PMC heterogeneity in children of the age group we are studying, therefore the ROI coordinates used here were defined in adults. However, since the majority of cerebral volume development seems to occur before age six and become relatively stable by age ten (47), this issue of utilizing ROI coordinates from an adult study is likely to be minimal. An alternative approach would be to use age specific template, however this practice is more common with participants below the age of four (48). Future work should also control for potential effects of medication, the presence of co-morbid conditions (e.g. ADHD and anxiety), and different genotypes that may contribute to the variable findings of brain connectivity in ASD (19).

Despite these limitations our findings of both hypo- and hyper-connectivity within PMC regions underscore the importance of “tedious anatomy” (49) and highlight the need for more anatomical precision in functional connectivity studies of the DMN in ASD. Here we show that subtle but salient differences in anatomy reveal different patterns of altered brain connectivity in ASD. Taken together, our findings of differential patterns of connectivity within the PMC in children with ASD highlight the importance of addressing heterogeneity within neighboring cortical regions, and show for the first time that social impairments in childhood ASD are linked to hyper-connectivity of the DMN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tianwen Chen for assistance with data analysis and Maria Barth, Christina Young, Caitlin Tenison, and Sangeetha Santhanam for assistance with data collection. This work was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Career Development Award [K01MH092288] to LQU, as well as grants from the Singer Foundation, the Stanford Institute for Neuro-Innovation & Translational Neurosciences, and the National Institutes of Health [DC011095, MH084164] to VM. The funding organizations played no role in design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Portions of this data were presented at the annual meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping on June 14, 2012 Beijing, China.

Financial Disclosures: All of the authors have reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Baio J. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lombardo MV, Barnes JL, Wheelwright SJ, Baron-Cohen S. Self-referential cognition and empathy in autism. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uddin LQ. The self in autism: an emerging view from neuroimaging. Neurocase. 2011;17:201–208. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2010.509320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amodio DM, Frith CD. Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:268–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim AS. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:489–510. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.21029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckner RL, Carroll DC. Self-projection and the brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schilbach L, Eickhoff SB, Rotarska-Jagiela A, Fink GR, Vogeley K. Minds at rest? Social cognition as the default mode of cognizing and its putative relationship to the "default system" of the brain. Conscious Cogn. 2008;17:457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mars RB, Neubert FX, Noonan MP, Sallet J, Toni I, Rushworth MF. On the relationship between the "default mode network" and the "social brain". Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:189. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:483–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uddin LQ, Iacoboni M, Lange C, Keenan JP. The self and social cognition: the role of cortical midline structures and mirror neurons. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assaf M, Jagannathan K, Calhoun VD, Miller L, Stevens MC, Sahl R, et al. Abnormal functional connectivity of default mode sub-networks in autism spectrum disorder patients. Neuroimage. 2010;53:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherkassky VL, Kana RK, Keller TA, Just MA. Functional connectivity in a baseline resting-state network in autism. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1687–1690. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000239956.45448.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy DP, Redcay E, Courchesne E. Failing to deactivate: resting functional abnormalities in autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8275–8280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600674103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monk CS, Peltier SJ, Wiggins JL, Weng SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, et al. Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage. 2009;47:764–772. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weng SJ, Wiggins JL, Peltier SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, Lord C, et al. Alterations of resting state functional connectivity in the default network in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudie JD, Hernandez LM, Brown JA, Beck-Pancer D, Colich NL, Gorrindo P, et al. Autism-Associated Promoter Variant in MET Impacts Functional and Structural Brain Networks. Neuron. 2012;75:904–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Lynch CJ, Khouzam A, Phillips J, Menon V. Salience network based classification and prediction of symptom severity in children with autism. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Supekar K, Uddin LQ, Khouzam A, Phillips J, Gaillard WD, Kentworthy L, et al. The 18th Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping. China: Beijing; 2012. Widespread brain hyper-connectivity in children with autism. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon EM, Lee PS, Maisog JM, Foss-Feig J, Billington ME, Vanmeter J, et al. Strength of default mode resting-state connectivity relates to white matter integrity in children. Dev Sci. 2011;14:738–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Supekar K, Uddin LQ, Prater K, Amin H, Greicius MD, Menon V. Development of functional and structural connectivity within the default mode network in young children. Neuroimage. 2010;52:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fair DA, Cohen AL, Dosenbach NU, Church JA, Miezin FM, Barch DM, et al. The maturing architecture of the brain's default network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4028–4032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800376105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margulies DS, Vincent JL, Kelly C, Lohmann G, Uddin LQ, Biswal BB, et al. Precuneus shares intrinsic functional architecture in humans and monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20069–20074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905314106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parvizi J, Van Hoesen GW, Buckwalter J, Damasio A. Neural connections of the posteromedial cortex in the macaque. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1563–1568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507729103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leichnetz GR. Connections of the medial posterior parietal cortex (area 7m) in the monkey. Anat Rec. 2001;263:215–236. doi: 10.1002/ar.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morecraft RJ, Cipolloni PB, Stilwell-Morecraft KS, Gedney MT, Pandya DN. Cytoarchitecture and cortical connections of the posterior cingulate and adjacent somatosensory fields in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:37–69. doi: 10.1002/cne.10980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogt BA, Vogt L, Laureys S. Cytology and functionally correlated circuits of human posterior cingulate areas. Neuroimage. 2006;29:452–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy DP, Courchesne E. The intrinsic functional organization of the brain is altered in autism. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1877–1885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shulman GL, Fiez JA, Corbetta M, Buckner RL, M MF, Raichle ME, et al. Common Blood Flow Changes across Visual Tasks: II. Decreases in Cerebral Cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9:648–663. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leech R, Braga R, Sharp DJ. Echoes of the brain within the posterior cingulate cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:215–222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3689-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang S, Li CS. Functional connectivity mapping of the human precuneus by resting state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2011;59:3548–3562. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glover GH, Lai S. Self-navigated spiral fMRI: interleaved versus single-shot. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:361–368. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tibshirani RJ. Univariate shrinkage in the cox model for high dimensional data. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2009;8 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1438. Article21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Menon V. Typical and atypical development of functional human brain networks: insights from resting-state FMRI. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:21. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Just MA, Keller TA, Malave VL, Kana RK, Varma S. Autism as a neural systems disorder: A theory of frontal-posterior underconnectivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1292–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vissers ME, Cohen MX, Geurts HM. Brain connectivity and high functioning autism: a promising path of research that needs refined models, methodological convergence, and stronger behavioral links. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;36:604–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrews-Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron. 2010;65:550–562. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muller RA, Shih P, Keehn B, Deyoe JR, Leyden KM, Shukla DK. Underconnected, but how? A survey of functional connectivity MRI studies in autism spectrum disorders. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2233–2243. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oblak AL, Rosene DL, Kemper TL, Bauman ML, Blatt GJ. Altered posterior cingulate cortical cyctoarchitecture, but normal density of neurons and interneurons in the posterior cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus in autism. Autism Res. 2011;4:200–211. doi: 10.1002/aur.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olson IR, Plotzker A, Ezzyat Y. The Enigmatic temporal pole: a review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain. 2007;130:1718–1731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saleem KS, Kondo H, Price JL. Complementary circuits connecting the orbital and medial prefrontal networks with the temporal, insular, and opercular cortex in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:659–693. doi: 10.1002/cne.21577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spreng RN, Grady CL. Patterns of Brain Activity Supporting Autobiographical Memory, Prospection, and Theory-of-Mind and Their Relationship to the Default Mode Network. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spreng RN, Mar RA. I remember you: a role for memory in social cognition and the functional neuroanatomy of their interaction. Brain Res. 2012;1428:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lenroot RK, Giedd JN. Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanchez CE, Richards JE, Almli CR. Neurodevelopmental MRI brain templates for children from 2 weeks to 4 years of age. Dev Psychobiol. 2012;54:77–91. doi: 10.1002/dev.20579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Devlin JT, Poldrack RA. In praise of tedious anatomy. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.055. discussion 1050-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.