Abstract

Purpose

The cell cycle progression (CCP) score, a prognostic RNA signature based on the average expression level of 31 CCP genes, has been shown to predict biochemical recurrence (BCR) after prostatectomy and prostate cancer specific mortality in men undergoing observation. However, the value of the CCP score in men who received primary external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is untested.

Methods and Materials

The CCP score was derived retrospectively from diagnostic biopsy specimens of men diagnosed with prostate cancer from 1991 to 2006 (n=141). All patients were treated with definitive EBRT; approximately half of the cohort was African-American. Outcome was time from EBRT to BCR using the Phoenix definition. Median follow-up for patients without BCR was 4.8 years. Association with outcome was evaluated by CoxPH survival analysis and likelihood ratio tests.

Results

Of 141 patients, 19 (13%) had BCR. The median CCP score for patient samples was 0.12. In univariable analysis, CCP score significantly predicted BCR (p-value = 0.0017). The hazard ratio (HR) for BCR was 2.55 for a one-unit increase in CCP score (equivalent to a doubling of gene expression). In a multivariable analysis with Gleason score, PSA, percent positive cores, and androgen deprivation therapy, the HR for CCP remained significant (p-value = 0.034), indicating that CCP provides prognostic information that is not provided by standard clinical parameters. With 10-year censoring, the CCP score was associated with prostate cancer specific mortality (p-value = 0.013). There was no evidence for interaction between CCP and any clinical variable, including ethnicity.

Conclusions

Among men treated with EBRT, the CCP score significantly predicated outcome and provided greater prognostic information than was available with clinical parameters. If validated in a larger cohort, CCP score could identify high-risk men undergoing EBRT who may need more aggressive therapy.

Keywords: CCP, radiation, biomarkers

Introduction

For men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer, accurate risk stratification enables appropriate clinical management. Currently, clinical parameters such as Gleason score, serum PSA, and clinical T stage provide some prognostic information. For men identified with low-risk disease, active surveillance or other deferred intervention regimens may be the best choice (1). Alternatively, for men with intermediate and high-risk disease, curative therapy is warranted. However, within all of these risk groups, there is heterogeneity of clinical outcomes. Therefore, improved discrimination would be useful to determine optimal therapy for all patients.

For men treated with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), existing prognostic models are hindered by the fact that the tumor is not removed, precluding accurate ascertainment of stage, grade and tumor volume (2). Moreover, no prognostic biomarkers with the exception of PSA have proven sufficiently informative to impact clinical care. About 30% of the patients treated with definitive ERBT progress biochemically. If these patients could be identified at diagnosis, they might benefit from more aggressive therapies (e.g. EBRT with brachytherapy boost) (3) and/or concurrent administration of systemic therapies like androgen deprivation. However, as more intensive therapies also result in unwanted morbidities they should be avoided in men who are likely to be controlled following EBRT alone. As such, accurate assessment of the risk of biochemical progression is crucial to provide optimal clinical care.

Recently, we developed a prognostic RNA signature that helps characterize prostate cancer aggressiveness (4,5). The signature is based on determining the expression levels of cell cycle progression (CCP) genes, and likely measures the fraction of tumor cells that are actively dividing. Since the signature is based on fundamental cancer biology, it potentially provides prognostic information in many different clinical settings. In fact, the signature has been associated with adverse outcome in conservatively managed cohorts from the UK and in surgically treated cohorts from the U.S. (4,5). However, its ability to predict outcome after EBRT is untested. Here, we evaluated the prognostic utility of the CCP score for predicting biochemical recurrence (BCR) in men treated with EBRT as their primary curative therapy. We hypothesized that high CCP score would be correlated with poor outcome (i.e. BCR) and that this association would hold even after controlling for standard clinical characteristics.

Methods and Materials

Cohort

Patients were included if they underwent diagnostic biopsy for prostate cancer between 1991 and 2006, and were treated with definitive EBRT (either alone or in combination with ADT). Patients without available formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded (FFPE) blocks containing their original diagnostic biopsy were excluded. Additional predefined exclusion criteria were pre-treatment PSA greater than 100 ng/ml and patients who began treatment > 2 years after diagnostic biopsy. Finally, patients with follow up data for less than 3 years who had not developed BCR within this time frame were excluded.

Sample preparation and real-time PCR

FFPE biopsy tumor blocks underwent pathological evaluation. The original diagnostic hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue sections from each block were evaluated for tumor content. The tumor area was identified, measured (length in mm), and circled. Based on the tumor length, additional unstained 10μm sections of tissue were cut so that at least 20 mm of total tumor (mm on H&E × # slides) were used for subsequent RNA isolation.

Selected tumor regions were removed from the unstained slides by macro-dissection according to pathologist’s instructions. The tumor region was dissected directly into a centrifuge tube and the paraffin removed using xylene and washed with ethanol. Samples were treated overnight with proteinase K digestion at 55°C. Total RNA was extracted using miRNeasy (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer (with the exception of the extended proteinase K digestion). Isolated total RNA was treated with DNase I (Sigma) prior to cDNA synthesis. High-capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems) was used to convert total RNA into single strand cDNA as described by manufacturer. Prior to measuring expression levels, the cDNA was pre-amplified with a pooled reaction containing 31 CCP and 15 housekeeping (HK) gene TaqMan assays. Pre-amplification reaction conditions were: 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15sec and 60°C for 14 cycles and dilute 1:20 using the 1XTE buffer prior to loading on Taqman Low Density Arrays (TLDA, Applied Biosystems) to measure gene expression. All samples were run in triplicate.

CCP score calculation

The CCP score was calculated from the expression data of 31 CCP genes normalized by the expression of 15 HK genes as previously described (4). CCP scores were rejected if more than 9 CCP genes were missing (n=5), or if the standard deviation of the CCP scores within the triplicate was greater than 0.5 (n=2; these two CCP scores were also part of the group of CCP scores rejected due to missing genes).

Statistical Analysis

Survival analysis was carried out using Cox proportional hazards (PH) models, to assess the association between the CCP score as a continuous variable and risk of BCR. The primary endpoint was time to BCR event. BCR was defined as reaching a post-RT PSA of nadir + 2ng/ml (Phoenix criteria, 23 patients), or due to secondary treatment for a rising PSA prior to meeting the Phoenix definition (5 patients). Prostate cancer specific mortality was defined as death in any patient with metastases showing progression following ADT. Time zero was defined as the start of radiation, and observations were censored on the date of last follow-up or death. The majority of the analysis is based upon 5-year censoring to address the observed time dependence of hazard ratio (HR) for CCP and the fact that BCR after 5-years post-RT may be less clinically relevant. The exception was analysis of disease-specific mortality, which was based on 10-year censoring due to the longer time frame required to observe disease-related mortality. The clinical and demographic variables recorded were age at diagnosis, ethnicity (African-American, White, Asian, Hispanic, Other), baseline PSA, clinical stage, Gleason score, concurrent hormone use, percent positive cores, year of biopsy, and radiation dose. We also used a modified D’Amico risk classification (6) to stratify patient risk. Low-risk was defined as PSA <10 and Gleason <7, intermediate risk as PSA 10–20 or Gleason 7, and high-risk as PSA >20 or Gleason 8–10 disease. All CCP scores were assigned prior to unmasking the clinical and outcome data.

PSA concentration was modeled as the natural logarithm of 1 + PSA (ng/ml) to account for the right-skewed distribution of PSA values. In addition, 1 was added to PSA prior to transformation to prevent men with low PSA levels from having negative numbers. Gleason scores were grouped into three categories: less than 7, equal to 7, and greater than 7. Models were fitted with Gleason score considered as a three-level nominal categorical variable. All test statistics were calculated as the change in the partial likelihood deviance metric between the full model and the appropriate reduced model. HR was used to measure the risk of BCR for a one-unit increase in CCP score.

A multivariable Cox PH model was fit to assess the added prognostic information of the CCP score on BCR risk, after adjustment for other clinical characteristics including PSA, Gleason score, and percent positive cores (considered continuous over the interval (0,1)). A secondary analysis with fewer patients also included clinical stage, radiation dose, and concurrent hormone use as these data were not available for all men. The CCP score was evaluated as a linear and a quadratic term, and tested for interactions with all considered clinical and demographic variables. The correlation between scaled Schoenfeld residuals versus untransformed time was used to evaluate the proportional hazards assumption for Cox regression, and specifically the time-dependence of the hazard associated with CCP. The two-sample t-test was used to test for a difference in means for CCP scores. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test for a difference in central location for PSA and percent positive cores. Statistical inference was conducted within the R (version 2.15.1, June 2012, R Development Core Team) and SAS (version 9.2) software environments. Statistical significance was set at the 5% level, prior to conducting inference. All p-values and confidence intervals were two-sided.

Results

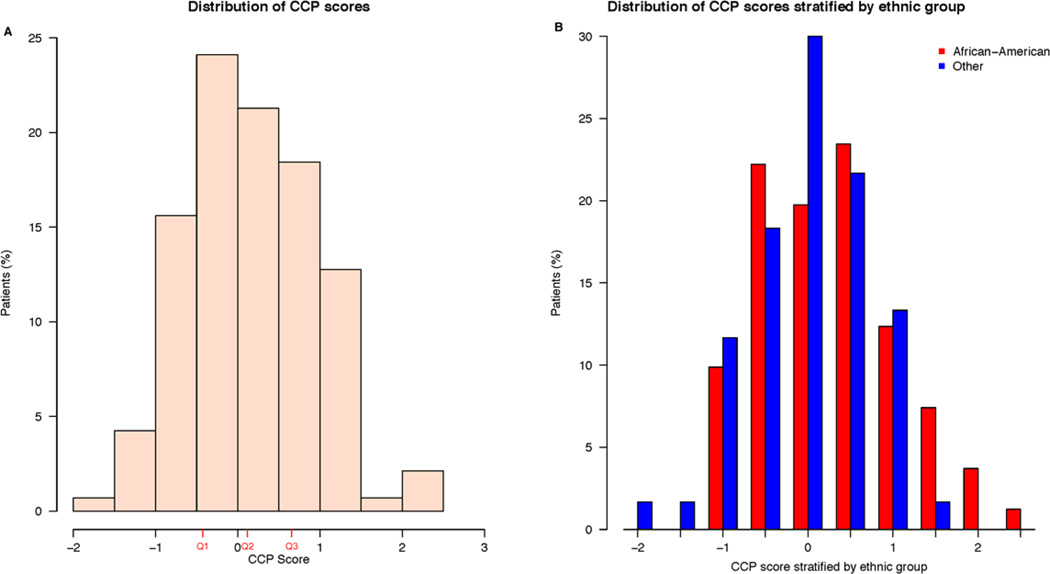

Initially, 179 men were identified for inclusion in this study. However, 27 patients (15%) where eliminated from the study due to little or no tumor remaining in their diagnostic biopsy, 5 patients (3%) with sufficient tumor failed to generate gene expression data, and 6 patients (3%) were eliminated because EBRT therapy was initiated more than two years after diagnostic biopsy (Supplementary Figure 1). Therefore, the final study cohort contained 141 patients. The clinical characteristics of the 141 patients are shown in Table 1, and were similar to the 38 excluded patients, with the exception of Gleason score. As expected, patients who were primarily excluded for no remaining tumor tended to have lower Gleason scores. The CCP score distribution is shown in Figure 1. The African-American patients had slightly higher scores than other ethnicities (mostly Caucasian), but the difference was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.079). The African-American patients also had higher PSA values (p-value = 0.0073), and tended to have a higher percentage of positive biopsy cores (p-value = 0.074).

Table 1.

Summary measures for the considered clinical and demographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | N | Summary Measure |

|---|---|---|

| CCP score, median (IQR) | 141 | 0.12 (−0.43, 0.66) |

| Age, years at diagnosis, median (IQR) | 141 | 66 (60, 71) |

| Ethnicity† (%) | ||

| African-American | 81 | 57.4 |

| Other | 60 | 42.6 |

| Baseline PSA‡ (ng/ml), median (IQR) | 140 | 8.04 (5.45, 13.47) |

| Clinical stage (%) | ||

| T1 | 72 | 60.0 |

| T2 | 44 | 36.7 |

| T3 | 4 | 3.3 |

| Gleason score (%) | ||

| <7 | 54 | 38.3 |

| 7 | 70 | 49.6 |

| >7 | 17 | 12.1 |

| Concurrent hormone use (%) | ||

| No | 74 | 52.5 |

| Yes | 67 | 47.5 |

| Percent positive cores, median (IQR) | 134 | 45 (24, 67) |

| Year of biopsy, median (IQR) | 141 | 2004 (2001, 2005) |

| Modified D’Amico risk (%) | ||

| Low | 38 | 27.3 |

| Intermediate | 72 | 51.8 |

| High | 29 | 20.9 |

| Radiation Dose (Gy), median (IQR) | 116 | 74 (71, 74) |

Abbreviations: CCP = cell cycle progression; IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; Gy = gray.

Data were collected upon 81 African-Americans, 58 Whites, and 2 patients of “Other” ethnicity. We dichotomized ethnicity, to avoid statistical modeling issues resulting from data sparseness.

Maximum baseline PSA was 87.7 ng/ml.

Figure 1.

Distribution of CCP scores. A) Distribution in entire cohort. Red tick marks indicate the 25th (Q1, −0.43), the median (Q2, 0.12), and 75th (Q3, 0.66) percentile of score values. B) CCP score distribution stratified by ethnicity.

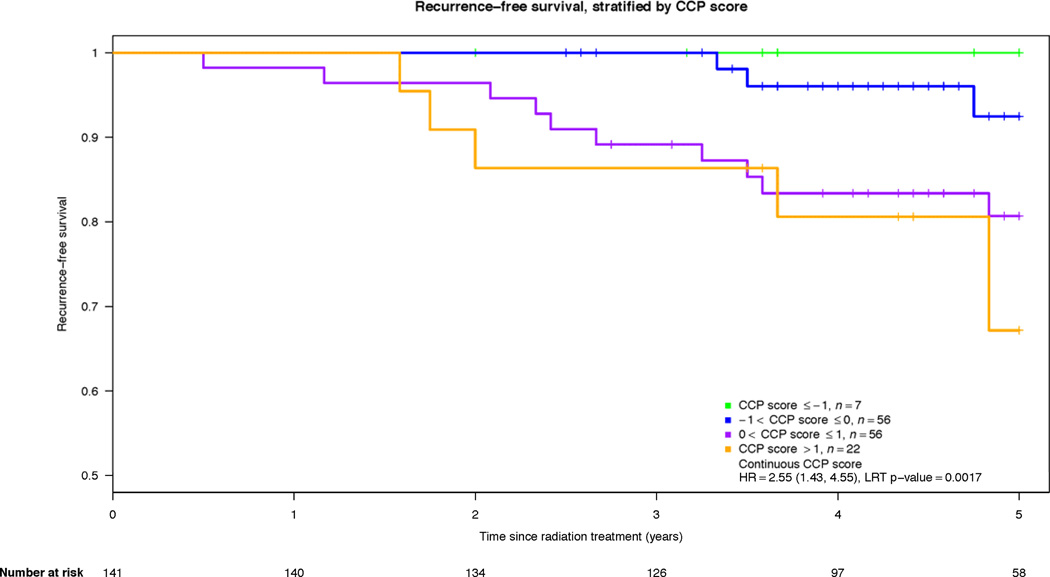

In evaluating the univariable association between CCP and BCR after EBRT with 10-year censoring, we saw strong evidence for time-dependency in the CCP score hazard ratio (HR), indicating that the CCP score was more predictive of BCR events in the first 5-years compared to predicting BCR from 5 to 10 years (p-value = 0.0063). However, the median follow-up time for patients who did not recur was only 4.75 years, and only 9 BCR events happened after 5 years. Therefore, the results presented here are based on 5-year censoring. Within this time frame, there was no evidence for time-dependency in CCP HR (p-value = 0.63). By 5 years, 13.4% (19/141) of the cohort had BCR. CCP score was associated with BCR after EBRT (Table 2) (HR per CCP unit = 2.55; 95% CI (1.43, 4.55), p-value = 0.0017). The HR for a change from the 25th to 75th percentile of the score distribution was 2.75 (95% CI (1.47, 5.15)). The effect of a one-unit increase in CCP score (corresponding to a doubling of RNA expression) on the 5-year risk of BCR is shown in Figure 2. Finally, 6 patients died from prostate cancer by 10 years. The CCP score was associated with disease specific mortality (HR per CCP unit = 3.77; 95% CI (1.37, 10.4), p-value = 0.013).

Table 2.

Summary of the fitted univariable Cox models.

| Covariate | Number of events |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

χ2 (df) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCP score | 19 | 2.55 (1.43, 4.55) | 9.81 (1) | 0.0017 |

| Age, years at diagnosis | 19 | 1.06 (0.99, 1.13) | 2.74 (1) | 0.098 |

| Ethnicity | 4.0×10−4 (1) | 0.984 | ||

| African-American | 11 | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Other | 8 | 0.99 (0.40, 2.47) | ||

| log(1 + PSA) | 19 | 2.72 (1.57, 4.71) | 11.9 (1) | 0.00057 |

| Clinical stage |

10.1 (2) |

0.0066 |

||

| T1 | 4 | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| T2 | 9 | 3.53 (1.09, 11.5) | ||

| T3 | 2 | 19.08 (3.43, 106.2) | ||

| Gleason score |

5.95 (2) |

0.051 |

||

| <7 | 3 | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 7 | 13 | 3.87 (1.10, 13.6) | ||

| >7 | 3 | 3.67 (0.74, 18.2) | ||

| Concurrent hormone use | 1.17 (1) | 0.280 | ||

| No | 8 | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Yes | 11 | 1.65 (0.66, 4.11) | ||

| Percent positive cores | 17 | 6.24 (1.05, 36.9) | 4.02 (1) | 0.045 |

| Year of biopsy | 19 | 0.90 (0.79, 1.03) | 2.15 (1) | 0.142 |

| Modified D’Amico risk |

8.49 (2) |

0.014 |

||

| Low | 1 | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Intermediate | 10 | 6.20 (0.79, 48.6) | ||

| High | 7 | 11.12 (1.37, 90.5) | ||

| Radiation dose | 15 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | 0.84 (1) | 0.358 |

Abbreviations: CCP = cell cycle progression; CI = confidence interval; χ2 = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; Gy = gray; ref = reference category.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier for 5-year recurrence free survival illustrating the effect of a one-unit increase in CCP score (also equivalent to a doubling in gene expression levels).

Our multivariable analysis included adjustments for pretreatment PSA, Gleason, percent positive cores, and concurrent ADT. The CCP score remained significantly predictive of BCR (Table 3) (HR per CCP unit = 2.11 (95% CI (1.05, 4.25), p-value = 0.034). Further adjustment for clinical stage or radiation dose did not materially alter the HR for CCP (1.93), but the number of included patients was reduced to 105 so these variables were not included in the final multivariable model. There was no evidence for an interaction between CCP and any tested clinical variable including ethnicity (p-value ≥ 0.17). As in previous studies (4,5), CCP score was only weakly correlated with other clinical variables (strongest correlation with any single clinical variable was with clinical stage, ρ = 0.33), demonstrating that the CCP score provides mostly independent information about prognosis.

Table 3.

Summary of the fitted multivariable Cox model.(a)

| Covariate | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

χ2 (df) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCP score | 2.11 (1.05, 4.25) | 4.48 (1) | 0.034 | |

| log(1 + PSA) | 1.77 (0.90, 3.48) | 2.93 (1) | 0.087 | |

| Gleason score |

3.25 (2) |

0.197 |

||

| <7 | 1.00 (ref) | |||

| 7 | 3.73 (0.76, 18.2) | |||

| >7 | 2.71 (0.42, 17.5) | |||

| Percent positive cores | 1.11 (0.13, 9.19) | 0.01 (1) | 0.920 | |

| Concurrent hormone use | 0.05 (1) | 0.826 | ||

| No | 1.00 (ref) | |||

| Yes | 1.14 (0.35, 3.78) | |||

Abbreviations: CCP = cell cycle progression; CI = confidence interval; χ2 = chi-square; df = degrees of freedom; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; ref = reference category;

N = 134, with 17 events

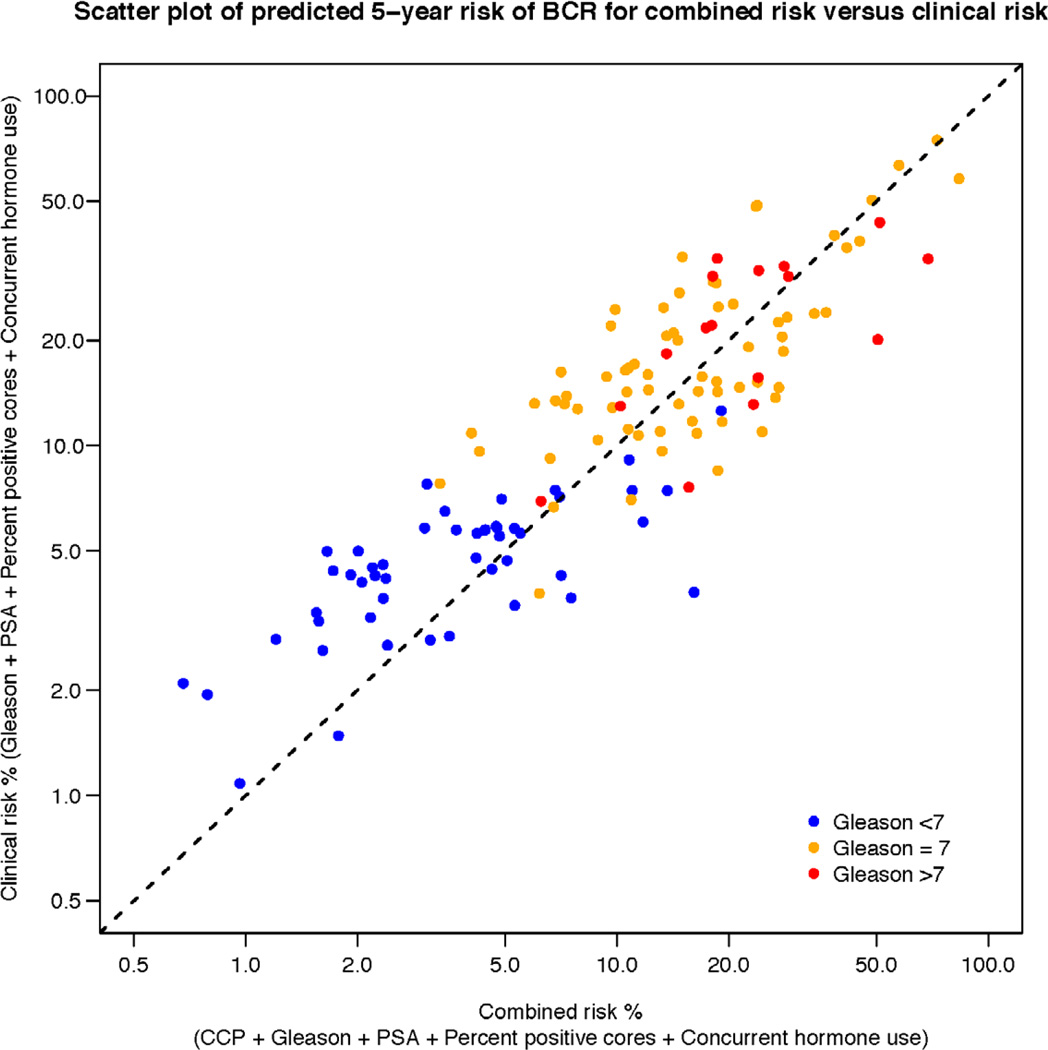

To illustrate how the addition of CCP score to a prediction model changes patient prognosis, we compared the prediction obtained using clinical parameters only to the prediction obtained using clinical parameters combined with CCP score (Figure 3). It can be seen from the figure that for any given risk connoted by clinical parameters, these patients could be further risk stratified by adding CCP score. This was true across the entire spectrum of clinical risk. The c-index for the model presented in Figure 3 including the CCP score was 0.80, which was an improvement over a model with clinical variables only (c-index = 0.78), but is also indicative of the limited sensitivity of c-index to detect improved discrimination in survival analysis (7).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of the 5-year predicted risk of BCR for a model including CCP score (x-axis) versus clinical parameters only (y-axis). Patient’s Gleason score is indicated by dot color. For any given patient, the added contribution of the CCP score to the predicted risk, based on Gleason, PSA, percent positive cores, and concurrent ADT, can be determined by the horizontal distance between the dot and the diagonal dashed line.

Discussion

For patients opting for treatment of localized prostate cancer, prognostic biomarkers are needed to inform appropriate intensity and duration of intervention. As demonstrated here, the CCP score derived from the diagnostic biopsy is prognostic of biochemical failure and, although there were few events, also predictive of disease specific morality after primary EBRT. To our knowledge this is the first example of a prognostic molecular biomarker for primary radiation therapy besides PSA. This result is also consistent with previous data showing Ki67 expression (also a CCP gene) predicts failure after salvage radiation therapy (8). Finally, this is the first demonstration of the prognostic utility of CCP score in African-American patients.

Patients with high CCP scores were more likely to progress (Figure 2). Importantly, the prognostic information provided by the CCP score was mostly independent of other clinical variables (as demonstrated by the only modest reduction in HR in multivariable compared to univariable analysis), and because the score is only modestly correlated with other variables, it provides improved risk discrimination across the spectrum of clinical risk. Similar characteristics regarding the prognostic utility of the CCP score and its relationship to other clinical variables have been observed in previous studies (4,5).

In this study, we see evidence that the CCP score was a strong predictor of early treatment failures, but that the prognostic utility declined over time (p-value of 0.0063 for time dependency in CCP HR). Consistent with this observation, we have seen evidence of time dependence in the CCP HR in some of our previous studies (5). Perhaps later failures (after 5 years) are less indicative of aggressive disease, and instead include more local recurrences that are less clinically relevant. Alternatively, late recurrences may be due technical issues in radiation delivery. If true, then these events (recurrence due to less aggressive disease or technical issues) would not be predicted by disease biology, which CCP measures. In fact, short time to EBRT failure has been shown to be a poor prognostic indicator in other studies (9). This can be contrasted to the lack of time dependency in the observed association in this study between CCP score and disease-specific mortality, supporting the view that disease-specific death is indicative of aggressive disease regardless of elapsed time from diagnosis. Perhaps the CCP score predicts micrometastatic disease present at the time of initial diagnosis and treatment. If true, then a high CCP score, and thus, a high risk for micrometastases, would indicate the need for treatment with both a local and systemic therapy (i.e. HRT + ADT). However, given the limitations of this study including the small size of the cohort, small number of treatment failures, and the relatively short follow-up time, definitive conclusions regarding time dependency will require additional studies.

The data presented here, confirm and extend our previous work demonstrating the prognostic utility of the CCP score. Earlier studies have shown the score to be prognostic in biopsies from conservatively treated men from the UK and from surgically resected tumors in post-prostatectomy cohorts from the U.S. (4,5). In this study, patients were treated with EBRT as their primary curative therapy. Previously, the univarable HR (per unit score) for CCP score has ranged from 1.89 to 2.92, which is consistent with the HR reported here (2.55). The CCP score probably measures the fraction of dividing cells within the sampled tumor tissue, and as such, gives a quantitative measure of tumor growth. The consistent behavior of the CCP score indicates that the relationship between this measure and prostate cancer outcome is robust to both patient composition and specific clinical treatment. However, as noted, given the small sample size and modest follow-up, these results require validation in larger cohorts with longer clinical follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Summary.

This study evaluated whether a mRNA based diagnostic assay (CCP score) can be used as a prognostic indicator in EBRT-treated prostate cancer patients. The CCP score was significantly predictive of biochemical recurrence even after adjustment for standard clinical parameters. This is also the first study that evaluated the prognostic utility of CCP score in African-American patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding for this study was provided by Myriad Genetics, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest Notification

A potential conflict of interest does exist since employees of Myriad Genetics, Inc. have received salary and stock from Myriad Genetics, Inc. The other authors, not employed by Myriad Genetics, Inc., do not have a conflict of interest since they have not received payment from Myriad Genetics, Inc.

References

- 1.Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roach M, 3rd, Waldman F, Pollack A. Predictive models in external beam radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:3112–3120. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurwitz MD, Halabi S, Archer L, et al. Combination external beam radiation and brachytherapy boost with androgen deprivation for treatment of intermediate-risk prostate cancer: Long-term results of calgb 99809. Cancer. 2011;117:5579–5588. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuzick J, Swanson GP, Fisher G, et al. Prognostic value of an rna expression signature derived from cell cycle proliferation genes in patients with prostate cancer: A retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:245–255. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuzick J, Berney DM, Fisher G, et al. Prognostic value of a cell cycle progression signature for prostate cancer death in a conservatively managed needle biopsy cohort. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1095–1099. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280:969–974. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, D'Agostino RB, Jr, et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the roc curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–172. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker AS, Heckman MG, Wu KJ, et al. Evaluation of ki-67 staining levels as an independent biomarker of biochemical recurrence after salvage radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1364–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denham JW, Steigler A, Wilcox C, et al. Time to biochemical failure and prostate-specific antigen doubling time as surrogates for prostate cancer-specific mortality: Evidence from the trog 96.01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1058–1068. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.