Abstract

An understanding of the relationship between the breadth and magnitude of T-cell epitope responses and viral loads is important for the design of effective vaccines. For this study, we screened a cohort of 46 subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected individuals for T-cell responses against a panel of peptides corresponding to the complete subtype C genome. We used a gamma interferon ELISPOT assay to explore the hypothesis that patterns of T-cell responses across the expressed HIV-1 genome correlate with viral control. The estimated median time from seroconversion to response for the cohort was 13 months, and the order of cumulative T-cell responses against HIV proteins was as follows: Nef > Gag > Pol > Env > Vif > Rev > Vpr > Tat > Vpu. Nef was the most intensely targeted protein, with 97.5% of the epitopes being clustered within 119 amino acids, constituting almost one-third of the responses across the expressed genome. The second most targeted region was p24, comprising 17% of the responses. There was no correlation between viral load and the breadth of responses, but there was a weak positive correlation (r = 0.297; P = 0.034) between viral load and the total magnitude of responses, implying that the magnitude of T-cell recognition did not contribute to viral control. When hierarchical patterns of recognition were correlated with the viral load, preferential targeting of Gag was significantly (r = 0.445; P = 0.0025) associated with viral control. These data suggest that preferential targeting of Gag epitopes, rather than the breadth or magnitude of the response across the genome, may be an important marker of immune efficacy. These data have significance for the design of vaccines and for interpretation of vaccine-induced responses.

It is estimated that 42 million people are infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), with 29.4 million infected individuals, constituting 70% of the global epidemic, living in sub-Saharan Africa (http://unaids.org/). The worst hit areas of the HIV/AIDS pandemic are in southern Africa, and in South Africa >25% of the adult population is infected (17), with high incidence rates (47). Molecular epidemiological studies have shown that the HIV-1 epidemic is heterosexually transmitted and dominated by subtype C (22, 37, 44, 45). Thus, developing an effective HIV-1 vaccine to curtail this epidemic is increasingly important, and the identity of possible correlates of immune protection against HIV infection or disease is thought to be fundamental to this process. Since one of the main outcomes of a possible efficacious vaccine would be the stimulation of anti-HIV T-cell immunity, it is important to define the type and scope of T-cell immune responses that correlate with control of the virus. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to determine what aspects of CD8+ T-cell immunity are associated with the control of subtype C HIV-1 in natural infections.

Class I major histocompatibility complex-restricted CD8+ T lymphocytes play a central role in the host immune response to HIV infection (6, 11, 12, 14, 24, 25, 30). Compelling evidence for the role of these cells has been shown by depleting CD8+ T cells in SIV-infected macaques, resulting in enhanced virus replication and accelerated pathogenesis (26, 34, 40). Vaccine strategies capable of eliciting virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses have been shown to control virus replication and to prevent the onset of disease in monkeys (4, 5, 41). With human studies, the emergence and preservation of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses in individuals with acute HIV infection have been shown to coincide with a rapid decline in plasma viremia (29, 49); strong and robust HIV-specific CTL responses are maintained in pediatric and adult long-term nonprogressors (13, 20, 27, 39), and disease progression is accompanied by a decline in CTL responses (27). While CD8+ T cells appear to play an important role in anti-HIV immunity, there are conflicting clinical data on the association of CD8+ T-cell responses with plasma viremia. Some studies have observed an inverse correlation between plasma viral load and HIV-specific T-cell responses (9, 10, 14, 21, 36, 38), and other studies have demonstrated a positive correlation (7, 11). In contrast, recent reports have found no correlation between plasma viral load and HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (1, 36).

The identification of CTL epitopes during the early stage of HIV-1 infection is thought to be important for vaccine design, since vaccines may elicit epitope-specific responses that are relevant for contemporary circulating viruses. These responses are considered important as a defining property of immunogenicity in HIV-1 vaccine trials and are a desired outcome of vaccine-induced T-cell immunity. In addition to the identification and definition of significant epitopes, it is also important to define the qualitative nature of anti-HIV T-cell immunity. With this objective, we investigated CD8+ T-cell responses against a series of overlapping subtype C-based peptides corresponding to the nine expressed HIV-1 gene regions by using a gamma interferon (IFN-γ) ELISPOT assay. We measured the frequency of T-cell responses from individuals recently infected with subtype C HIV-1 and identified associations between patterns of CD8+ T-cell recognition and viral control. There was no significant association between the breadth of response and the plasma viral load, although there was a significant positive correlation between total cumulative responses. When the order of recognition of protein regions was placed in a hierarchy for each individual, we found a significant positive correlation between the preferential targeting of Gag and the plasma viral load. These data represent important information regarding mechanisms associated with viral control and how multigenic vaccine candidates may be evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient cohort.

Forty-six patients were recruited within approximately 2 years of seroconversion, with an estimated median time of 13 months (Table 1). The time from seroconversion was estimated as the midpoint between the last antibody-negative assay result and the first HIV-1-positive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay result. All individuals were naïve for antiretroviral drugs. These individuals were recruited as part of the HIVNET 028 Study, and patients were enrolled from five clinic sites in four southern African countries: Malawi (n = 8), Zimbabwe (n = 10), Zambia (n = 8), and South Africa (n = 20). These individuals displayed a wide range of viral loads, with some individuals showing control of viremia and others showing no control (Table 1). There were no significant associations between the country of origin and viremia, and for the purposes of this study, individuals were grouped as one cohort.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of 46 patients screened for full genome expressed responses at specific times after seroconversion

| Patient no. | Months postsero- conversion | CD4 count (per mm3) | CD8 count (per mm3) | CD4/CD8 ratio | No. of RNA copies/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.4 | 371 | 853 | 0.435 | 15,565 |

| 2 | 4.4 | 610 | 727 | 0.839 | 15,588 |

| 3 | 4.9 | 434 | 234 | 1.855 | 50 |

| 4 | 4.9 | 661 | 684 | 0.966 | 29,013 |

| 5 | 5.1 | 512 | 714 | 0.717 | 1,523 |

| 6 | 5.3 | 473 | 1,143 | 0.414 | 4,108 |

| 7 | 5.5 | 424 | 846 | 0.501 | 4,160 |

| 8 | 6.5 | 637 | 591 | 1.178 | NDb |

| 9 | 6.7 | 538 | 796 | 0.676 | 1,195 |

| 10 | 8.0 | 188 | 1,140 | 0.165 | 331,441 |

| 11 | 8.0 | 486 | 720 | 0.675 | 9,746 |

| 12 | 8.5 | 45 | 174 | 0.259 | 202,735 |

| 13 | 8.5 | 75 | 311 | 0.241 | 239,828 |

| 14 | 5.3 | 481 | 577 | 0.834 | 146,916 |

| 15 | 10.5 | 1,307 | 669 | 1.954 | 1,104 |

| 16 | 10.8 | 167 | 432 | 0.387 | 46,328 |

| 17 | 11.2 | 242 | 907 | 0.267 | 73,753 |

| 18 | 11.7 | 287 | 595 | 0.482 | 33,921 |

| 19 | 12.0 | 780 | 739 | 1.055 | 6,189 |

| 20 | 12.2 | 455 | 508 | 0.896 | 20,439 |

| 21 | 12.4 | 300 | 479 | 0.626 | 11,463 |

| 22 | 12.9 | 703 | 1,151 | 0.611 | 2,300 |

| 23 | 13.1 | 361 | 2,000 | 0.18 | 46,984 |

| 24 | 14.3 | 255 | 741 | 0.344 | 16,952 |

| 25 | 14.3 | 460 | 483 | 0.952 | 5,014 |

| 26 | 12.9 | 608 | 685 | 0.888 | 8,583 |

| 27 | 14.4 | 670 | 2,307 | 0.29 | 774 |

| 28 | 15.1 | 322 | 710 | 0.454 | 5,788 |

| 29 | 16.1 | 522 | 507 | 1.03 | 14,199 |

| 30 | 16.5 | 253 | 1,663 | 0.152 | 68,521 |

| 31 | 17.6 | 143 | 641 | 0.223 | 23,273 |

| 32 | 18.1 | 600 | 1,212 | 0.495 | 6,841 |

| 33 | 19.0 | 397 | 1,432 | 0.277 | 1,862 |

| 34 | 19.0 | 448 | 1,252 | 0.358 | 8,048 |

| 35 | 20.1 | 663 | 1,551 | 0.427 | 569 |

| 36 | 21.9 | 476 | 709 | 0.671 | 93,697 |

| 37 | 22.5 | 855 | 927 | 0.922 | 108 |

| 38 | 22.8 | 178 | 331 | 0.538 | 39,887 |

| 39 | 23.0 | 250 | 395 | 0.633 | 3,880 |

| 40 | 23.2 | 216 | 473 | 0.457 | 25,249 |

| 41 | 24.1 | 308 | 451 | 0.683 | 33,575 |

| 42 | 24.4 | 453 | 1,141 | 0.397 | 37,706 |

| 43 | 24.5 | 560 | 883 | 0.634 | 718 |

| 44 | 24.7 | 507 | 602 | 0.842 | 45,007 |

| 45 | 25.0 | 337 | 542 | 0.622 | 10,727 |

| 46 | 25.7 | 364 | 804 | 0.453 | 1,983 |

| Median | 13.0 | 451 | 712 | 0.6 | 11,463 |

| 25% IQRa | 8.1 | 290 | 517 | 0.4 | 3,880 |

| 75% IQRa | 19.8 | 555 | 922 | 0.8 | 37,706 |

IQR, interquartile range.

ND, not done.

Synthetic peptides.

Synthetic peptides spanning nine subtype C HIV-1 gene regions (with the exception of integrase) were made by using 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl-based solid-phase chemistry (Natural and Medical Sciences Institute, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany). All peptides were checked for the correct molecular weight by Elektrospray QTOF-mass spectrometry. Peptide purities ranged from 70 to 80%. A total of 396 overlapping peptides were synthesized, some of which were designed to match gene regions selected for inclusion in subtype C vaccine candidates. Pol, Rev, Tat, Nef, and gp160 were based on Du151 and Du179 (gp160) (48), and Gag, Vpu, Vif, and Vpr were based on consensus C (a generous gift from Marcus Altfeld, Massachusetts General Hospital). Nef peptides were synthesized as 15-mers overlapping at 11 amino acids (aa), and the remaining peptides varied from 15- to 18-mers overlapping at 10 residues and were designed by use of PeptGen (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/hiv-db/PEPTGEN/PeptGenSubmitForm.html). Peptides were dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide at an initial concentration of 10 mg/ml and were pooled at 40 μg/ml/peptide stock in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in which the final dimethyl sulfoxide concentration was always <0.5%.

Design of peptide pools.

The 396 peptides used for this study were arranged in a pool with a matrix design allowing a single screen of responses across the HIV-1 genome on one 96-well plate. Each of the nine gene regions was pooled with no more than 24 peptides/pool. Table 2 shows the details of the pools for each of the nine expressed gene regions.

TABLE 2.

Arrangement of each of the nine expressed gene regions into pools

| Gene region | No. of pools | No. of peptides/ pool | Peptide length (aa) | Overlap (aa) | Strain that peptides were based on |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pol | 4 | 24 | 15-18 | 10 | Du 151 |

| Tat | 1 | 12 | 15-18 | 10 | Du 151 |

| Rev | 1 | 14 | 15-18 | 10 | Du 151 |

| Env | 5 | 24 | 15-18 | 10 | Du 179 |

| Nef | 5 | 10 | 15 | 11 | Du 151 |

| Gag | 5 | 14 | 15-18 | 10 | Consensus |

| Vif | 2 | 12 | 15-18 | 10 | Consensus |

| Vpr | 1 | 11 | 15-18 | 10 | Consensus |

| Vpu | 1 | 9 | 15-18 | 10 | Consensus |

Forty-eight more pools were constructed in a matrix design (M1 to M48) containing 12 or 5 peptides/pool. By employing a pool and matrix approach, it was possible to identify individual peptide responses from multiple pool responses. For example, if a response was identified in Gag pool 1, the Tat pool, Env pools 2 and 5, and Nef pools 2 and 3 and the matrix pool responses were found in M2, M21, M27, M39, and M48, this resulted in peptide selections of Gag 3, Tat 1 and 11, Env 51 and 104, and Nef 20 and 21. Thus, from the 396 peptides in the initial screen, the selection was eventually narrowed to seven individual peptides for confirmation.

PBMC preparation.

Cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were thawed and allowed to rest overnight in R10 medium (RPMI 1640 [Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom]) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen) and 50 U of gentamicin (Invitrogen) at 2 × 106 to 4 × 106 PBMC/ml at 37°C in 5% CO2 prior to use in the ELISPOT assay (15). After the incubation, cells were counted by trypan blue dye exclusion and were used in assays.

ELISPOT assay.

ELISPOT assays were performed as previously described (31). Briefly cryopreserved PBMC were thawed and plated in 96-well polyvinylidene difluoride plates (MAIP S45; Millipore, Johannesburg, South Africa) that had been coated with 50 μl of anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody 1-D1k (2 μg/ml) (Mabtech, Stockholm, Sweden) overnight at 4°C. Peptides were added directly to the wells at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml along with 1 × 105 to 2 × 105 cells in 50 μl of R10 medium and were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 16 to 18 h, plates were extensively washed with PBS and wash buffer (PBS, 1% fetal calf serum, and 0.001% Tween 20), followed by incubation with a biotinylated anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (2 μg/ml) (clone 7-B6-1; Mabtech) at room temperature for 3 h. After six more washes with wash buffer, 2 μg of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Pharmingen)/ml was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated for another 1 h at room temperature. Spots were visualized by using Novared substrate (Vector, Burlingame, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Duplicate wells containing PBMC and R10 medium as well as R10 medium alone were used as negative controls. Wells containing PBMC and phytohemagglutinin served as positive controls. As an additional control, duplicate wells containing PBMC and pools of cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and influenza virus (CEF) epitopes were used (16). The number of spots per well was counted with an Immunospot (Cellular Technology Ltd., Cleveland, Ohio) automated plate counter. Peptide responses were confirmed by using individual peptides in the ELISPOT assay, and in some experiments, CD8+ T-cell dependence was confirmed by CD8 and immunoglobulin G (mock) depletion by use of magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Assessment of cutoffs in the ELISPOT assay.

An important criterion for defining what constitutes a positive response in the ELISPOT assay is the lower threshold, or cutoff, above which a response is classified as positive. For determination of the background reactivity to the HIV-1 peptides, PBMC from 25 HIV-1-seronegative individuals were used to define the spread of negative responses. Figure 1 shows the spread of spot-forming units (SFU)/106 PBMC, where the mean SFU/106 PBMC for each pool ranged from 13 to 19, with an overall mean value of 16 ± 22 SFU/106 PBMC. For the purpose of defining a cutoff, 4 standard deviations (88 SFU/106 PBMC) above the mean, or >104 SFU/106 PBMC, was considered positive. Additionally, if the number of spots in the negative controls exceeded 20 SFU/106 PBMC per well, the ELISPOT assay was repeated. A further criterion used for defining positive responses was a match between a pool response and a matrix response.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of responses from HIV-1-seronegative individuals to each of the peptide pools (Gag to Nef), showing the boundaries of the mean SFU/106 PBMC and 4 standard deviations (dotted lines demarcated by arrow), with the upper threshold being 104 SFU/106 PBMC.

Statistical and data analysis.

All data were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges and were analyzed by use of nonparametric statistics. Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analysis of variance was used to test for significant differences across gene regions, and Dunn's pairwise analysis was used to identify differences between gene regions and regions recognized within each gene region. For tests between two groups, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. For assessments of the relationships between responses, Spearman rank correlations were used and corrected for multiple tests. Statistical analysis was performed by use of SigmaStat 2.0 (SPSS Science, Chicago, Ill.).

Cumulative responses identified for each protein region were adjusted for protein length by dividing the total combined pool response identified for each individual by the number of amino acids making up the protein region. The breadth of responses for each participant was calculated by (i) counting the number of positive peptide pools and (ii) counting the number of protein regions. Hierarchical responses were identified by ordering each of the combined peptide pool responses (corresponding to Gag, Pol, Vif, Vpr, Tat, Rev, Vpu, Env, and Nef) from one to nine, with one being the highest SFU/106 PBMC value and nine being the lowest response.

RESULTS

Distribution of HIV-1-specific T-cell responses across subtype C.

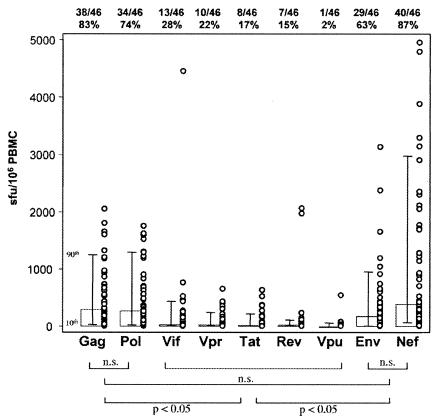

Forty-four of 46 (95.6%) subtype C HIV-1-infected individuals responded to one or more of the 396 peptides used in this study. Figure 2 shows the distribution of SFU/106 PBMC for the 44 responders across the expressed genome, with 87% recognizing Nef, 83% recognizing Gag, 74% recognizing Pol, 63% recognizing Env, 28% recognizing Vif, 22% recognizing Vpr, 17% recognizing Tat, 15% recognizing Rev, and 2% recognizing Vpu. When median SFU/106 PBMC values were compared across different regions of the genome, that for Nef was highest. No significant differences existed between Gag, Pol, Env, and Nef SFU/106 PBMC values. However, these responses were all significantly higher than those for Vif, Vpr, Tat, Rev, and Vpu (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of responses across complete peptide pool sets, showing medians with the 10th and 90th percentiles as well as individual plots. The proportion of individuals responding to each peptide set is shown above the plot, and the significance levels between regions are shown below the plot. Significance was measured by Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analysis of variance and Dunn's pairwise analysis. n.s., not significant.

Distribution of HIV-1-specific T-cell responses within subtype C proteins.

The extent of T-cell targeting within each gene region was further delineated by examining the cumulative frequencies of SFU/106 PBMC in specific pools, demarcated by amino acid numbers in Fig. 3. Overall, the highest cumulative magnitude of HIV-1-specific cells was found directed to the central region of Nef, between aa 52 and 171 (Fig. 3A). This 119-aa stretch made up 97.5% of the anti-Nef responses and constituted 32% of the total cumulative SFU/106 PBMC relative to the rest of the genome. Within Gag, responses to aa 219 to 322 in p24 were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those to any other subregion of Gag (Fig. 3A). Relative to the total cumulative response across the genome, responses to p24 made up 17.4%. For Pol, the SFU/106 PBMC values for reverse transcriptase (aa 355 to 533) and RNase H (aa 534 to 689) peptides were significantly higher than those for other regions within Pol, and they collectively amounted to 9.6% of the total responses across the genome. Because integrase was missing from the pool makeup, it was not possible to gauge how this region was targeted or how it influenced the spread of responses within Pol. Within Env, there appeared to be a uniform spread of SFU/106 PBMC values within gp41 and gp120 (aa 192 to 694). Of the accessory gene products, there was a higher response to the N-terminal half of Vif (aa 1 to 102) than to the C terminus, although the difference was not significant. Relative to the total positive response across the genome, the SFU/106 PBMC values for Rev and Tat constituted 4.4 and 2%, respectively, and the least recognized peptides were those corresponding to Vpr and Vpu.

FIG. 3.

Responses to peptide pools. (A) Cumulative SFU/106 PBMC responses to each of the peptide pools. (B) Frequencies of individuals recognizing each of the peptide pools, depicted as amino acid numbers, to show more detailed recognition of sites within pools. Consecutive amino acid numbers are shown across all pools, amounting to a total of 3,091 aa, corresponding to the complete expressed genome.

We next analyzed the frequencies of individual peptide pool responses targeted by subtype C HIV-1-infected individuals. Our data indicated that the most recognized region was the central region of Nef, followed by p17 (aa 1 to 111), p24 (aa 219 to 322), RNase H (aa 534 to 689), and pools within Env (Fig. 3B). Although there was a higher magnitude of response to epitopes in p24 Gag, epitopes in p17 were more frequently recognized.

Identity of epitopic regions within Gag, Pol, Vif, Env, and Nef.

Some of the responses identified in the initial full-genome screen were confirmed by using single peptides in subsequent ELISPOT assays. Single-peptide confirmations allowed us to identify possible epitopes within 15- to 18-mers. Table 3 shows the amino acid sequences of confirmed subtype C peptide responses to Gag, Pol, Vif, Env, and Nef, and 24 of 47 (51%) responses were also identified as being CD8+ T-cell mediated after the depletion of CD8+ cells in the ELISPOT assay. There were insufficient samples to confirm the remaining responses as being CD8+ T-cell mediated. Seventy-four percent (35 of 47) of confirmed subtype C peptide responses were matched with previously described epitope sequences derived from subtype B (25). Although some of the subtype B epitope sequences were variant from the subtype C peptide sequences (Table 3), it was apparent that many of the responses targeted were in highly conserved regions of these genes. Of the 76 previously described subtype B epitopes (Table 3), 23 (30%) had one amino acid difference from the subtype C peptide sequence, eight (10.5%) had two amino acid differences, two (2.6%) had three amino acid differences, and two had four amino acid differences. Overall, 70% of previously described subtype B CTL epitope sequences were identical to the subtype C peptide sequences recognized.

TABLE 3.

Confirmed peptide responses in Gag, Pol, Vif, Env and Nef pools

| Peptide pool or peptide (aa) | Confirmed peptide sequence | SFU/106 cells

|

Selection of subtype B epitopes found in the subtype C epitopic regionsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC | CD8 | |||

| Gag | ||||

| 1-111 | 9RGGKLDKWEKIRLRPGGK26 | 158 | KIRLRPGGK, GELDRWEKI | |

| 1-111 | 17EKIRLRPGGKKHYMLKHL34 | 276 | 12 | KIRLRPGGKK, RLRPGGKKK |

| 1-111 | 25GKKHYMLKHLVWASREL41 | 160 | KYKLKHIVW | |

| 1-111 | 32KHLVWASRELERFAL46 | 345 | WASRELERF | |

| 1-111 | 71TGTEELRSLYNTVATLY87 | 981 | 9 | GTEELRSL, SLYNTVATLY, RSLYNTVATLY, TGTEELRSLY |

| 1-111 | 78SLYNTVATLYCVHAGIEV95 | 649 | 30 | SLYNTVATLY, TLYCVHAG |

| 112-218 | 155WVKVIEEKAFSPEVIPMF172 | 623 | KAFSPEVIPMF | |

| 112-218 | 163AFSPEVIPMFTALSEGA179 | 201 | EVIPMFSAL, VIPMFSAL | |

| 112-218 | 170PMFTALSEGATPQDLNTM187 | 512 | SEGATPQDL, LSEGATPQDL | |

| 112-218 | 178GATPQDLNTMLNTVGGH194 | 929 | TPQDLNTML | |

| 219-322 | 257PVGDIYKRWIILGLNKIV275 | 949 | GDIYKRWII, DIYKRWII, IYKRWIIL, IYKRWIILGL, IYKRWIILGLNK | |

| 219-322 | 289GPKEPFRDYVDRFFKTLR306 | 1,901 | 25 | RDYVDRFFKTLR, RDYVDRFFKT |

| 219-322 | 297YVDRFFKTLRAEQATQDV314 | 3,073 | 20 | DRFFKTLRA |

| 219-322 | 305LRAEQATQDVKNWMTDTL322 | 188 | RAEQASQEV, AEQASQDVKNW, QASQDVKNW | |

| Pol | ||||

| 1-175 | 22PQITLWQRPLVSIKI35 | 1,070 | VTLWQRPLV | |

| 176-354 | 305ALYVGSDLEIGQHRAKI321 | 1,480 | 10 | DLEIGQHRTK |

| 355-533 | 359TVQPIQLPEKDSWTVNDI376 | 230 | PIVLPEKDSW, IVLPEKDSW, VLPEKDSW | |

| 355-533 | 381GKLNWTSQIYPGIKVRQL398 | 418 | 0 | KLNWASQIY, QIYPGIKVR |

| 355-533 | 485KQLTEAVQKISLESIVTW502 | 180 | KITTESIVIW | |

| 355-533 | 508FRLPIQKETWEIWWTDYW525 | 270 | PIQKETWETW, TWETWWTEYW | |

| 534-689 | 552PIAGAETFYVDGAANR567 | 803 | 10 | IVGAETFYVDGAAN, GAETFYVDGA, AETFYVDGA, AETFYVDGAAN |

| 534-689 | 558TFYVDGAANRETKIGKA574 | 720 | 0 | No previously described epitopes |

| Vif | ||||

| 1-102 | 71LQTGERDWHLGHGVSIEW88 | 189 | 20 | No previously described epitopes |

| 1-102 | 78HLGHGVSIEWRLRRY93 | 377 | 10 | No previously described epitopes |

| 1-102 | 84VSIEWRLRRYSTQVDPGL101 | 164 | 10 | No previously described epitopes |

| 103-192 | 143SLYQYLALTALIKPKKIK159 | 420 | No previously described epitopes | |

| Env | ||||

| 192-346 | 197KVSFDPIPIHYCAPAGYA214 | 1,117 | 0 | VSFEPIPIHY, SFEPIPIHY |

| 192-346 | 290GNNTRKSIRIGPGQAFY306 | 290 | QRGPGRAFV, RIQRGPGRAF | |

| 192-346 | 297IRIGPGQAFYTBHIIGDI314 | 350 | No previously described epitopes | |

| 347-523 | 414DGGTDNTTEIFRPGGGNM431 | 350 | 0 | No previously described epitopes |

| 347-523 | 470RAVGIGAVLLGFLGAA492 | 380 | 0 | No previously described epitopes |

| 524-694 | 575WSNKSQQAIWDNMTWMQW592 | 780 | No previously described epitopes | |

| 524-694 | 583IWDNMTWMQWDREINNY599 | 400 | No previously described epitopes | |

| 524-694 | 657RIIFAVLSIVNRVRQGY673 | 103 | 10 | AVLSIVNRV, IVNRVRQGY |

| 524-694 | 664SIVNRVRQGYSPLSFQTL681 | 740 | 0 | IVNRVRQGY |

| 695-826 | 740AARTVELLGRSSLRGLQR757 | 190 | 0 | No previously described epitopes |

| Nef | ||||

| 1-51 | 42ALTSSNTAHNNPDCA55 | 965 | ALTSSNTAA | |

| 52-91 | 62EVGFPVRPQVPLRPM76 | 491 | FPVTPQVPL, FPVTPQVPLR, PVTPQVIPLRPM, PQVPLRPM | |

| 52-91 | 69PVRPQVPLRPMTYKA83 | 258 | VPLRFMTY, QVPLRPMTYK, PLRPMTYK | |

| 52-91 | 73QVPLRPMTYKAAFDL87 | 992 | QVPLRPMTYK, RPMTYKAAV | |

| 52-91 | 77RPMTYKAAFDLSSFL91 | 910 | 7 | MTYKAAVD, KAAVDLSHFL, AAVDLSHFL |

| 92-131 | 81YKAAFDLSFFLKEKG95 | 593 | 15 | KAAVDLSHFL, AAVDLSHFLKEK, AVDLSHFL, DLSHFLKEK |

| 92-131 | 101IHSKRRQDILDLWVY115 | 665 | 17 | HSQRRQDILDLWIY, RRQDILDLWI, RQDILDLWIY, DILDLWIF |

| 92-131 | 113WVYHTQGYFPDWQNY127 | 612 | 20 | YHTQGYFPDWQ, HTQGYFPDWQ, TQGYFPDWQNY |

| 132-171 | 129PGPGVRYPLTFGWCF143 | 1,704 | 15 | GPGVRYPLTFGWCY, RYPLTFGW, RYPLTFGWCF, YPLTFGWCY, TPLTFGWCF |

| 132-171 | 133VRYPLTFGWCFKLVP147 | 1,289 | 30 | RYPLTFGW, RYPLTFGWCY, RYPLTFGWCF |

| 132-171 | 157NKGENNCLLHPMSQH171 | 443 | No previously described epitopes | |

Previously described subtype B CTL epitopes (27) found within the subtype C peptide sequences are shown; bold letters denote amino acid variations from the subtype C epitopic sequence.

Within p17 Gag (aa 1 to 111), single-peptide confirmations identified six peptides (Table 3) that constituted the frequently recognized pool of aa 1 to 111 (Fig. 3B). When the overlaps were removed, two relatively long amino acid stretches (aa 9 to 46 and 71 to 95), 9RGGKLDKWEKIRLRPGGKKHYMLKHLVWASRELERFAL46 and 71TGTEELRSLYNTVATLYCVHAGIEV95) within p17 Gag, were identified as containing multiple epitopes that are frequently targeted by individuals. Similarly, within p24 Gag, eight single-peptide confirmations identified three immunodominant epitope-rich amino acid stretches as follows: 155WVKVIEEKAFSPEVIPMFTALSEGATPQDLNTMLNTVGGH194, 257PVGDIYKRWIILGLNKIV275, and 289GPKEPFRDYVDRFFKTLRAEQATQDVKNWMTDTL322 (Table 3). The last stretch (aa 289 to 322) was considered highly immunodominant, as it was significantly and frequently recognized by individuals (Fig. 3). We defined immunodominance as >50% of responses in <25% of the gene segment. Single peptide responses in Pol identified the sequences 552PIAGAETFYVDGAANRETKIGKA574 and 558TFYVDGAANRETKIGKA574, for which no epitopes have been previously described. Single peptide responses with the N-terminal half of Vif also revealed that novel epitopes were recognized, which was also the case for four peptide regions within Env, namely aa 414 to 431, 470 to 492, 575 to 592, and 583 to 599. Within Nef, three regions were significantly targeted, namely 62EVGFPVRPQVPLRPMTYKAAFDLSFFLKEKG95, 101IHSKRRQDILDLWVYHTQGYFPDWQNY127, and 129PGPGVRYPLTFGWCFKLVP147. Collectively, these subtype C epitopic regions within Nef contain 30 known subtype B CTL epitopes (Table 3).

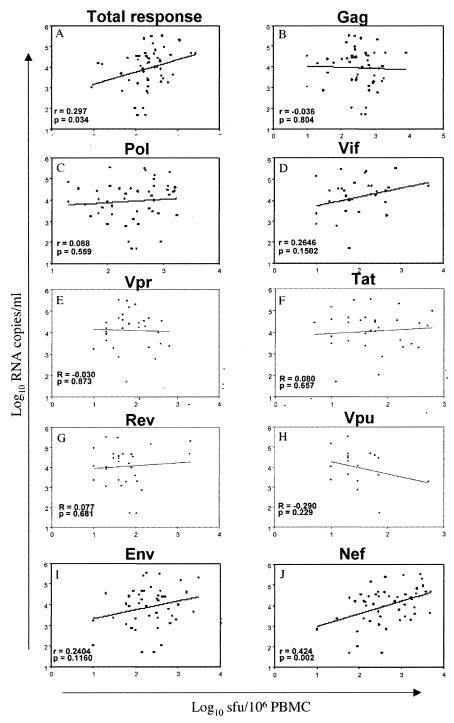

Correlation between HIV-1-specific T-cell responses and plasma viremia.

There was a small (r = 0.297) but significant (P = 0.034) correlation between total cumulative SFU/106 PBMC responses from all protein regions and plasma viral loads for 44 of 46 participants (Fig. 4A). A more detailed analysis of region-specific T-cell responses and viral loads revealed no significant associations (Fig. 4B to I) except for a highly significant (P = 0.002) positive correlation of 0.424 between Nef-specific responses and viral load. When total responses were correlated with CD4 counts, there was no significant correlation (r = −0.134; P = 0.57).

FIG. 4.

Correlations between log10 SFU/106 PBMC values and log10 plasma viral loads showing total responses to all peptide pools (A), Gag pools (B), Pol pools (C), Vif pools (D), the Vpr pool (E), the Tat pool (F), the Rev pool (G), the Vpu pool (H), Env pools (I), and Nef pools (J). Correlations were corrected for multiple tests by Bonferroni's analysis.

The breadth of responses for each participant was calculated by counting the number of pools that had >104 SFU/106 PBMC in the ELISPOT assay. There was a total of 25 pools used in the assay, with some participants recognizing 0 pools and others recognizing up to 13 pools. Each positive response to a pool was used as a conservative estimate of the number of epitopes recognized. Figure 5A shows no significant correlation between the number of peptide pools and the plasma viral load (r = 0.132; P = 0.359). In addition to counting of the number of positive pools, the number of complete protein regions recognized was correlated with the viral load. Figure 5B shows no significant association (r = 0.125; P = 0.424) between the number of complete regions recognized and the plasma viral load, and together these data show that the breadth of responses was not associated with viral control for this cohort.

FIG. 5.

Correlation between peptide or protein recognition and viral loads. (A) Correlation between the numbers of positive peptide pools recognized per individual (n = 44) and log10 plasma viral loads. Each peptide pool represents a conservative estimate of the number of epitopes recognized. (B) Correlation between the numbers of complete proteins recognized per individual (n = 44) and log10 plasma viral loads. Each region corresponds to one of the nine protein regions, and the numbers recognized measure the breadth of the response across the genome.

Correlation between the hierarchy of HIV-1-specific T-cell responses and plasma viremia.

When the cumulative SFU/106 PBMC values of the 44 individuals who responded to the peptide pools were ranked by order of magnitude, the overall order of recognition was as follows: Nef > Gag > Pol > Env > Vif > Rev > Vpr > Tat > Vpu (Fig. 6A). When adjusted for protein length, the order became as follows: Nef > Gag > Rev > Vif > Vpr > Tat > Pol > Env > Vpu (Fig. 6B). Combined, these data reflect the dominance of Nef and Gag HIV-1-specific T-cell epitope responses within this cohort. As there appeared to be a clear hierarchy of responses within the cohort, we wished to identify on an individual basis whether hierarchical rankings were associated with plasma viral loads. Thus, for each individual, the total SFU/106 PBMC per protein was ranked by order of magnitude from 1 to 9 (corresponding to the gene regions). When these resulting hierarchies were plotted with viral loads, a significant positive correlation existed for Gag (when unadjusted for protein length, r = 0.445 and P = 0.0025, and when adjusted for protein length, r = 0.428 and P = 0.0027) (Fig. 6C), suggesting that when Gag is the target preferred by CD8+ T cells, there is an association with significantly lower viral loads. A similar positive association was not found for any other region (Fig. 6D to F). However, there was a significant negative correlation between the unadjusted Nef hierarchy and viral loads which when adjusted for protein length was no longer significant (when unadjusted for protein length, r = −0.317 and P = 0.025, and when adjusted for protein length, r = −0.203 and P = 0.162) (Fig. 6F). There was also no significant association between the hierarchy of Gag recognition and the overall immune status of individuals, as measured by CD4 counts (r = −0.07; P = 0.57).

FIG. 6.

(A) Cumulative SFU/106 PBMC response to complete sets of peptides (corresponding to whole protein regions) ranked as a hierarchy from highest to lowest recognition. (B) Cumulative response adjusted for protein length ranked as a hierarchy from highest to lowest recognition. (C) Correlation between the hierarchy of responses to Gag and the log10 plasma viral load for both the unadjusted and adjusted ranking for each individual. (D) Correlation for Pol. (E) Correlation for Env. (F) Correlation for Nef. Thick short lines correspond to the unadjusted hierarchical responses, and longer lines correspond to the adjusted hierarchical responses.

DISCUSSION

Southern Africa is at the epicenter of the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. The epidemic is dominated by subtype C infections (45), and it is important to characterize T-cell responses in this population with the aim of identifying aspects of immunity that correlate with viral control. With this study, we wished to not only measure the breadth and magnitude of T-cell responses directed at subtype C HIV-1, but also to determine patterns of CD8+ T-cell recognition across the fully expressed genome. To explore the hypothesis that patterns of response may be associated with viral control, we used a series of overlapping peptides based on South African subtype C HIV-1 sequences. Five of the nine sets of peptides corresponded to gene regions chosen for subtype C vaccine development (48), which also allowed us to measure the strength, range, and identity of epitope-specific T-cell responses to reagents matching vaccine candidates. To date, only one study, using blood donor units from Botswana, has reported comprehensive responses to HIV-1 proteins by subtype C HIV-1-infected individuals (36). Our study provides further information and describes responses for a defined cohort for which the time from seroconversion is known.

All individuals examined for this study were infected by subtype C HIV-1, as determined by gag, nef, and pol sequencing (C. Willimson and R. Donovan, unpublished data). Most individuals studied responded to at least one peptide. However, we observed that 2 of the 46 HIV-1-infected individuals did not respond to any of the peptides. It is possible that these individuals may have targeted integrase, which was absent from the peptide set, or that they may have developed CD8+ T cells that targeted variant regions of the sequences in the peptide set. It was recently shown that anti-HIV T-cell responses to variable gene products are underestimated when consensus-based peptides, rather than peptides based on an autologous virus, are used (2). In our study, the central region of Nef was highly targeted, with responses to Nef making up almost one-third of the total responses. This region, spanning 119 aa, is known to be highly conserved across subtypes (32). It is unlikely that a bias existed for more responses to Nef, because we used shorter Nef peptides with a 1-aa-shorter overlap for this study. It was recently shown that 18-mer sequences overlapping by 10 aa are equivalent to 15-mer sequences overlapping by 10 or 11 aa in ELISPOT assays (18). The more conserved regions in Gag p17 and p24 were also frequently targeted, with the magnitude of anti-p24 responses being significantly higher than that of anti-p17 responses. Responses to Vif, Vpr, Tat, Rev, and Vpu were significantly less frequent than those to Gag, Pol, Env, and Nef, possibly reflecting more variability in these genes (43, 46, 51).

Within the central region of Nef, the most frequently targeted epitope region was 129PGPGVRYPLTFGWCF143. This highly conserved sequence matched seven previously reported subtype B-defined epitopes (28). A similar analysis with Gag p24 showed that the most frequently recognized epitopic re-gion was 289GPKEPFRDYVDRFFKTLRAEQATQDV314,which is known to contain subtype B-defined HLA-B*14, -B*15, -B*18, and -B*44 restricted epitopes (28). Similarly, responses to Pol and Env peptides revealed that the majority of frequently recognized peptides occurred in highly conserved regions and contained epitopes that have been described previously (28). These results further confirm the conservation of T-cell epitopes between subtypes, as was previously predicted by sequence analysis (32) and demonstrated by cross-clade CTL responses (8, 33, 50). It was also apparent that novel epitopes were identified, especially in Vif and regions within Env. As there are common, but unique, HLA allele frequencies in southern African populations (19, 23, 35) that differ from those that restrict many subtype B CTL epitopes, it is possible that CTL epitopes are fairly promiscuous and degenerate, so that known epitopes are restricted by different HLA molecules (15). We hypothesize that degenerate epitopes exist in more conserved regions of the subtype C genome, while more variable regions contain novel epitopes. Overall, there is likely to be a wealth of as yet undescribed and novel CTL epitopes found in populations with different HLA backgrounds, as found in southern Africa.

A number of studies have demonstrated the central role of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the control of SIV replication in nonhuman primates (26, 40), and recent studies have shown that vaccine-induced SIV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses attenuate disease progression (3, 5, 42). Although some studies of HIV-1-infected individuals have shown that there is an inverse correlation between plasma viremia and HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (10, 14, 21, 38), the limitation of these studies has been the focus on a single or selected panel of optimal epitopes. The comprehensive analysis of using overlapping peptides in our study showed a significant positive correlation between the magnitude of total T-cell responses to HIV-1 and the viral load. Correlations at the individual protein level showed that anti-Nef responses may be associated with higher viral loads, and there were positive trends for anti-Vif and anti-Env responses. We found no significant correlation between anti-Gag responses and viral loads, although there was a hint of a negative trend. This contrasts with observations made with subtype C HIV-1-infected blood donors, for whom anti-p24 responses showed a significant negative correlation with viral loads (36). Overall, our data are in agreement with studies looking at responses in a range of antiretroviral-naïve subtype B HIV-1-infected individuals, for whom a positive correlation between plasma viremia and total HIV-1-specific CD8+ T-cell responses was identified (7). Similar observations were made at the epitope level with children (11), for whom a positive correlation existed between the frequency of MHC A*02-restricted Gag (SL9) and Pol (IV9) epitope-specific CD8+ T cells and viremia. These observations support the hypothesis that the frequency of HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells is a reflection of antigenic load, rather than a determining factor of viral control, and is independent of subtype. In contrast, other recent reports have shown no correlation between plasma viremia and total HIV-1-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in subtype B-infected individuals (1) and subtype C-infected African blood donors (36). These discrepancies could be related to differences in the study cohorts, as the former study was a mixture of drug-naïve and drug-treated individuals, or the stage of infection, as the cohort in Botswana was undefined and may have consisted of chronically infected individuals (36).

Recent studies associating the quality of memory CTL functioning with viremia demonstrated that the breadth of recognition was inversely correlated with plasma viral loads (14). Similarly, studies using ELISPOT assays have shown that the magnitude and breadth of T-cell responses recognizing Gag or p24 peptides are inversely related to viral loads (21). In our study, there was no association between the breadth of T-cell recognition and viral loads, in agreement with recent observations made for subtype B infections (1, 12). Collectively, the data suggest that low viral loads in individuals within this cohort are unrelated to the breadth and magnitude of CD8+ T-cell epitope responses.

When we looked at our data for patterns of response, we found that when we ranked the order of responses across complete peptide sets, corresponding to whole protein regions, there was a significant positive correlation between Gag hierarchy and the viral load. These data show that when an individual preferentially targets Gag, there is a significantly lower viral load. Since this association remains after an adjustment for protein length, we conclude that the preferential targeting of epitopes in Gag is important for viral control. The negative association with Nef hierarchy, although not significant when adjusted for protein length, argues for the domineering nature of anti-Nef responses at the early stage of infection, which does not seem to be related to viral control. This effect appears to be independent of the gross immune status of the individual, as no such correlations were identified with CD4 counts.

We have shown in this study that subtype C HIV-1-infected individuals in the early stage of infection target multiple protein regions, with responses dominated by Nef. There was a positive correlation between anti-HIV-1 responses and plasma viremia, largely constituted by Nef-specific responses, and the hierarchy of Gag-specific responses correlated with plasma viral loads. We therefore conclude that preferential targeting of Gag epitopes during the early stage of infection correlates with viral control and can be used to provide a marker of immune efficacy. These hierarchical patterns should be taken into account when assessing the immunogenicity of future multigenic candidate vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kingdom Mofhandu and Mmusi Rampou for expert technical help. We also thank the clinical staff at each of the clinical sites for their invaluable help in collecting and shipping samples. Finally, we thank the HIV-1-infected participants of this study.

A.M. is a South African AIDS Vaccine Initiative (SAAVI) fellow, and T.M. is a Fogarty International Fellow. Funding was provided by NIH grant N01-AI-45202.

The HIVNET 028 Study team comprises the following: Clive Gray (cochair) and Haynes Sheppard (cochair), Zambia University Teaching Hospital; Rosemary Masondu, Susan Allen, and Michelle Klautzman, University of Alabama; Newton Kumwenda, Malawi College of Medicine; Taha Taha, Johns Hopkins University; Lynn Zijenah, Victoria Aquino, Michael Chirenje, Mike Mbizo, and Ocean Tobaiwa, University of Zimbabwe; David Katzenstein, Stanford University; Glenda Gray, James McIntyre, and Armstrong Mafhandu, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa; Efthyia Vardas, Mark Colvin, Dudu Msweli, Wendy Dlamini, Gita Ramjee, Salim Abdool Karim, and Quarraisha Abdool Karim, Medical Research Council, Durban, South Africa; Lynn Morris and Natasha Taylor, National Institute for Communicable Diseases; Carolyn Williamson, Helba Bredell, and Celia Rademayer, University of Cape Town; Jorge Flores, Division of AIDS, National Institutes of Health; and Ward Cates, Linda McNeil, and Missie Allen, Family Health International.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addo, M. M., X. G. Yu, A. Rathod, D. Cohen, R. L. Eldridge, D. Strick, M. N. Johnston, C. Corcoran, A. G. Wurcel, C. A. Fitzpatrick, M. E. Feeney, W. R. Rodriguez, N. Basgoz, R. Draenert, D. R. Stone, C. Brander, P. J. Goulder, E. S. Rosenberg, M. Altfeld, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Comprehensive epitope analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell responses directed against the entire expressed HIV-1 genome demonstrate broadly directed responses, but no correlation to viral load. J. Virol. 77:2081-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altfeld, M., M. M. Addo, R. Shankarappa, P. K. Lee, T. M. Allen, X. G. Yu, A. Rathod, J. Harlow, K. O'Sullivan, M. N. Johnston, P. J. Goulder, J. I. Mullins, E. S. Rosenberg, C. Brander, B. Korber, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Enhanced detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific T-cell responses to highly variable regions by using peptides based on autologous virus sequences. J. Virol. 77:7330-7340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amara, R. R., F. Villinger, J. D. Altman, S. L. Lydy, S. P. O'Neil, S. I. Staprans, D. C. Montefiori, Y. Xu, J. G. Herndon, L. S. Wyatt, M. A. Candido, N. L. Kozyr, P. L. Earl, J. M. Smith, H. L. Ma, B. D. Grimm, M. L. Hulsey, J. Miller, H. M. McClure, J. M. McNicholl, B. Moss, and H. L. Robinson. 2001. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science 292:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barouch, D. H., S. Santra, M. J. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, R. Plishka, A. Buckler-White, A. E. Gaitan, R. Zin, J. H. Nam, L. S. Wyatt, M. A. Lifton, C. E. Nickerson, B. Moss, D. C. Montefiori, V. M. Hirsch, and N. L. Letvin. 2001. Reduction of simian-human immunodeficiency virus 89.6P viremia in rhesus monkeys by recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara vaccination. J. Virol. 75:5151-5158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barouch, D. H., S. Santra, J. E. Schmitz, M. J. Kuroda, T. M. Fu, W. Wagner, M. Bilska, A. Craiu, X. X. Zheng, G. R. Krivulka, K. Beaudry, M. A. Lifton, C. E. Nickerson, W. L. Trigona, K. Punt, D. C. Freed, L. Guan, S. Dubey, D. Casimiro, A. Simon, M. E. Davies, M. Chastain, T. B. Strom, R. S. Gelman, D. C. Montefiori, M. G. Lewis, E. A. Emini, J. W. Shiver, and N. L. Letvin. 2000. Control of viremia and prevention of clinical AIDS in rhesus monkeys by cytokine-augmented DNA vaccination. Science 290:486-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertoletti, A., F. Cham, S. McAdam, T. Rostron, S. Rowland-Jones, S. Sabally, T. Corrah, K. Ariyoshi, and H. Whittle. 1998. Cytotoxic T cells from human immunodeficiency virus type 2-infected patients frequently cross-react with different human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clades. J. Virol. 72:2439-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betts, M. R., D. R. Ambrozak, D. C. Douek, S. Bonhoeffer, J. M. Brenchley, J. P. Casazza, R. A. Koup, and L. J. Picker. 2001. Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J. Virol. 75:11983-11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betts, M. R., J. Krowka, C. Santamaria, K. Balsamo, F. Gao, G. Mulundu, C. Luo, N. N′Gandu, H. Sheppard, B. H. Hahn, S. Allen, and J. A. Frelinger. 1997. Cross-clade human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in HIV-infected Zambians. J. Virol. 71:8908-8911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betts, M. R., J. F. Krowka, T. B. Kepler, M. Davidian, C. Christopherson, S. Kwok, L. Louie, J. Eron, H. Sheppard, and J. A. Frelinger. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity is inversely correlated with HIV type 1 viral load in HIV type 1-infected long-term survivors. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1219-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buseyne, F., J. Le Chenadec, B. Corre, F. Porrot, M. Burgard, C. Rouzioux, S. Blanche, M. J. Mayaux, and Y. Riviere. 2002. Inverse correlation between memory Gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and viral replication in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. J. Infect. Dis. 186:1589-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buseyne, F., D. Scott-Algara, F. Porrot, B. Corre, N. Bellal, M. Burgard, C. Rouzioux, S. Blanche, and Y. Riviere. 2002. Frequencies of ex vivo-activated human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific gamma-interferon-producing CD8+ T cells in infected children correlate positively with plasma viral load. J. Virol. 76:12414-12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao, J., J. McNevin, S. Holte, L. Fink, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 2003. Comprehensive analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific gamma interferon-secreting CD8+ T cells in primary HIV-1 infection. J. Virol. 77:6867-6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakraborty, R., G. M. Gillespie, M. Reinis, T. Rostron, T. Dong, S. Philpott, H. Burger, B. Weiser, T. Peto, and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2002. HIV-1-specific CD8 T cell responses in a pediatric slow progressor infected as a premature neonate. AIDS 16:2085-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chouquet, C., B. Autran, E. Gomard, J. M. Bouley, V. Calvez, C. Katlama, D. Costagliola, and Y. Riviere. 2002. Correlation between breadth of memory HIV-specific cytotoxic T cells, viral load and disease progression in HIV infection. AIDS 16:2399-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currier, J. R., M. deSouza, P. Chanbancherd, W. Bernstein, D. L. Birx, and J. H. Cox. 2002. Comprehensive screening for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype-specific CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes and definition of degenerate epitopes restricted by HLA-A0207 and -C(W)0304 alleles. J. Virol. 76:4971-4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currier, J. R., E. G. Kuta, E. Turk, L. B. Earhart, L. Loomis-Price, S. Janetzki, G. Ferrari, D. L. Birx, and J. H. Cox. 2002. A panel of MHC class I restricted viral peptides for use as a quality control for vaccine trial ELISPOT assays. J. Immunol. Methods 260:157-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health of South Africa. 2000. National HIV sero-prevalence survey of women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Summary report. Health Systems Research and Epidemiology, Department of Health, Pretoria, South Africa.

- 18.Draenert, R., M. Altfeld, C. Brander, N. Basgoz, C. Corcoran, A. G. Wurcel, D. R. Stone, S. A. Kalams, A. Trocha, M. M. Addo, P. J. Goulder, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Comparison of overlapping peptide sets for detection of antiviral CD8 and CD4 T cell responses. J. Immunol. Methods 275:19-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.du Toit, E. D., K. J. MacGregor, D. G. Taljaard, and M. Oudshoorn. 1988. HLA-A, B, C, DR and DQ polymorphisms in three South African population groups: South African Negroes, Cape Coloureds and South African Caucasoids. Tissue Antigens 31:109-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyer, W. B., G. S. Ogg, M. A. Demoitie, X. Jin, A. F. Geczy, S. L. Rowland-Jones, A. J. McMichael, D. F. Nixon, and J. S. Sullivan. 1999. Strong human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity in Sydney Blood Bank Cohort patients infected with Nef-defective HIV type 1. J. Virol. 73:436-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards, B. H., A. Bansal, S. Sabbaj, J. Bakari, M. J. Mulligan, and P. A. Goepfert. 2002. Magnitude of functional CD8+ T-cell responses to the Gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 correlates inversely with viral load in plasma. J. Virol. 76:2298-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelbrecht, S., T. de Villiers, C. C. Sampson, J. zur Megede, S. W. Barnett, and E. J. van Rensburg. 2001. Genetic analysis of the complete gag and env genes of HIV type 1 subtype C primary isolates from South Africa. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1533-1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond, M. 1997. HLA class I alleles in Zulus, p. 151. In D. W. Gjertson and P. I. Terasaki (ed.), HLA 1997. American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics, Lenexa, Kans.

- 24.Harrer, T., E. Harrer, S. A. Kalams, P. Barbosa, A. Trocha, R. P. Johnson, T. Elbeik, M. B. Feinberg, S. P. Buchbinder, and B. D. Walker. 1996. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes in asymptomatic long-term nonprogressing HIV-1 infection. Breadth and specificity of the response and relation to in vivo viral quasispecies in a person with prolonged infection and low viral load. J. Immunol. 156:2616-2623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrer, T., E. Harrer, S. A. Kalams, T. Elbeik, S. I. Staprans, M. B. Feinberg, Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, T. Yilma, A. M. Caliendo, R. P. Johnson, S. P. Buchbinder, and B. D. Walker. 1996. Strong cytotoxic T cell and weak neutralizing antibody responses in a subset of persons with stable nonprogressing HIV type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:585-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin, X., D. E. Bauer, S. E. Tuttleton, S. Lewin, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, C. E. Irwin, J. T. Safrit, J. Mittler, L. Weinberger, L. G. Kostrikis, L. Zhang, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8(+) T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 189:991-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein, M. R., C. A. van Baalen, A. M. Holwerda, S. R. Kerkhof Garde, R. J. Bende, I. P. Keet, J. K. Eeftinck-Schattenkerk, A. D. Osterhaus, H. Schuitemaker, and F. Miedema. 1995. Kinetics of Gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses during the clinical course of HIV-1 infection: a longitudinal analysis of rapid progressors and long-term asymptomatics. J. Exp. Med. 181:1365-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korber, B. T. M., C. Brander, B. F. Haynes, R. Koup, C. Kuiken, J. P. Moore, B. D. Walker, and D. I. Watkins. 2001. HIV molecular immunology 2001. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex.

- 29.Koup, R. A., J. T. Safrit, Y. Cao, C. A. Andrews, G. McLeod, W. Borkowsky, C. Farthing, and D. D. Ho. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650-4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuroda, M. J., J. E. Schmitz, W. A. Charini, C. E. Nickerson, M. A. Lifton, C. I. Lord, M. A. Forman, and N. L. Letvin. 1999. Emergence of CTL coincides with clearance of virus during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J. Immunol. 162:5127-5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mashishi, T., and C. M. Gray. 2002. The ELISPOT assay: an easily transferable method for measuring cellular responses and identifying T cell epitopes. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 40:903-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mashishi, T., S. Loubser, W. Hide, G. Hunt, L. Morris, G. Ramjee, S. Abdool-Karim, C. Williamson, and C. M. Gray. 2001. Conserved domains of subtype C nef from South African HIV type 1-infected individuals include cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope-rich regions. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1681-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAdam, S., P. Kaleebu, P. Krausa, P. Goulder, N. French, B. Collin, T. Blanchard, J. Whitworth, A. McMichael, and F. Gotch. 1998. Cross-clade recognition of p55 by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. AIDS 12:571-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metzner, K. J., X. Jin, F. V. Lee, A. Gettie, D. E. Bauer, M. Di Mascio, A. S. Perelson, P. A. Marx, D. D. Ho, L. G. Kostrikis, and R. I. Connor. 2000. Effects of in vivo CD8(+) T cell depletion on virus replication in rhesus macaques immunized with a live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccine. J. Exp. Med. 191:1921-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novitsky, V., P. O. Flores-Villanueva, P. Chigwedere, S. Gaolekwe, H. Bussman, G. Sebetso, R. Marlink, E. J. Yunis, and M. Essex. 2001. Identification of most frequent HLA class I antigen specificities in Botswana: relevance for HIV vaccine design. Hum. Immunol. 62:146-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Novitsky, V., P. Gilbert, T. Peter, M. F. McLane, S. Gaolekwe, N. Rybak, I. Thior, T. Ndung'u, R. Marlink, T. H. Lee, and M. Essex. 2003. Association between virus-specific T-cell responses and plasma viral load in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J. Virol. 77:882-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Novitsky, V., U. R. Smith, P. Gilbert, M. F. McLane, P. Chigwedere, C. Williamson, T. Ndung'u, I. Klein, S. Y. Chang, T. Peter, I. Thior, B. T. Foley, S. Gaolekwe, N. Rybak, S. Gaseitsiwe, F. Vannberg, R. Marlink, T. H. Lee, and M. Essex. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C molecular phylogeny: consensus sequence for an AIDS vaccine design? J. Virol. 76:5435-5451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogg, G. S., X. Jin, S. Bonhoeffer, P. R. Dunbar, M. A. Nowak, S. Monard, J. P. Segal, Y. Cao, S. L. Rowland-Jones, V. Cerundolo, A. Hurley, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. F. Nixon, and A. J. McMichael. 1998. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science 279:2103-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rinaldo, C., X. L. Huang, Z. F. Fan, M. Ding, L. Beltz, A. Logar, D. Panicali, G. Mazzara, J. Liebmann, M. Cottrill, et al. 1995. High levels of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) memory cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity and low viral load are associated with lack of disease in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J. Virol. 69:5838-5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmitz, J. E., M. J. Kuroda, S. Santra, V. G. Sasseville, M. A. Simon, M. A. Lifton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. Dalesandro, B. J. Scallon, J. Ghrayeb, M. A. Forman, D. C. Montefiori, E. P. Rieber, N. L. Letvin, and K. A. Reimann. 1999. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283:857-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seth, A., I. Ourmanov, J. E. Schmitz, M. J. Kuroda, M. A. Lifton, C. E. Nickerson, L. Wyatt, M. Carroll, B. Moss, D. Venzon, N. L. Letvin, and V. M. Hirsch. 2000. Immunization with a modified vaccinia virus expressing simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Gag-Pol primes for an anamnestic Gag-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response and is associated with reduction of viremia after SIV challenge. J. Virol. 74:2502-2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiver, J. W., T. M. Fu, L. Chen, D. R. Casimiro, M. E. Davies, R. K. Evans, Z. Q. Zhang, A. J. Simon, W. L. Trigona, S. A. Dubey, L. Huang, V. A. Harris, R. S. Long, X. Liang, L. Handt, W. A. Schleif, L. Zhu, D. C. Freed, N. V. Persaud, L. Guan, K. S. Punt, A. Tang, M. Chen, K. A. Wilson, K. B. Collins, G. J. Heidecker, V. R. Fernandez, H. C. Perry, J. G. Joyce, K. M. Grimm, J. C. Cook, P. M. Keller, D. S. Kresock, H. Mach, R. D. Troutman, L. A. Isopi, D. M. Williams, Z. Xu, K. E. Bohannon, D. B. Volkin, D. C. Montefiori, A. Miura, G. R. Krivulka, M. A. Lifton, M. J. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, N. L. Letvin, M. J. Caulfield, A. J. Bett, R. Youil, D. C. Kaslow, and E. A. Emini. 2002. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature 415:331-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephens, E. B., D. K. Singh, E. Pacyniak, and C. McCormick. 2001. Comparison of Vif sequences from diverse geographical isolates of HIV type 1 and SIV(cpz) identifies substitutions common to subtype C isolates and extensive variation in a proposed nuclear transport inhibition signal. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Harmelen, J., R. Wood, M. Lambrick, E. P. Rybicki, A. L. Williamson, and C. Williamson. 1997. An association between HIV-1 subtypes and mode of transmission in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS 11:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Harmelen, J. H., E. Van der Ryst, A. S. Loubser, D. York, S. Madurai, S. Lyons, R. Wood, and C. Williamson. 1999. A predominantly HIV type 1 subtype C-restricted epidemic in South African urban populations. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:395-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wieland, U., A. Seelhoff, A. Hofmann, J. E. Kuhn, H. J. Eggers, P. Mugyenyi, and S. Schwander. 1997. Diversity of the vif gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in Uganda. J. Gen. Virol. 78:393-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkinson, D., S. S. Abdool Karim, B. Williams, and E. Gouws. 2000. High HIV incidence and prevalence among young women in rural South Africa: developing a cohort for intervention trials. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 23:405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williamson, C., L. Morris, M. F. Maughan, L. H. Ping, S. A. Dryga, R. Thomas, E. A. Reap, T. Cilliers, J. van Harmelen, A. Pascual, G. Ramjee, G. Gray, R. Johnston, S. A. Karim, and R. Swanstrom. 2003. Characterization and selection of HIV-1 subtype C isolates for use in vaccine development. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 19:133-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson, J. D., G. S. Ogg, R. L. Allen, C. Davis, S. Shaunak, J. Downie, W. Dyer, C. Workman, S. Sullivan, A. J. McMichael, and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2000. Direct visualization of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes during primary infection. AIDS 14:225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson, S. E., S. L. Pedersen, J. C. Kunich, V. L. Wilkins, D. L. Mann, G. P. Mazzara, J. Tartaglia, C. L. Celum, and H. W. Sheppard. 1998. Cross-clade envelope glycoprotein 160-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in early HIV type 1 clade B infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 14:925-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yedavalli, V. R., M. Husain, A. Horodner, and N. Ahmad. 2001. Molecular characterization of HIV type 1 vpu genes from mothers and infants after perinatal transmission. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1089-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]