Abstract

Since the appearance of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle and its linkage with the human variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, the possible spread of this agent to sheep flocks has been of concern as a potential new source of contamination. Molecular analysis of the protease cleavage of the abnormal prion protein (PrP), by Western blotting (PrPres) or by immunohistochemical methods (PrPd), has shown some potential to distinguish BSE and scrapie in sheep. Using a newly developed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, we identified 18 infected sheep in which PrPres showed an increased sensitivity to proteinase K digestion. When analyzed by Western blotting, two of them showed a low molecular mass of unglycosylated PrPres as found in BSE-infected sheep, in contrast to other naturally infected sheep. A decrease of the labeling by P4 monoclonal antibody, which recognizes an epitope close to the protease cleavage site, was also found by Western blotting in the former two samples, but this was less marked than in BSE-infected sheep. These two samples, and all of the other natural scrapie cases studied, were clearly distinguishable from those from sheep inoculated with the BSE agent from either French or British cattle by immunohistochemical analysis of PrPd labeling in the brain and lymphoid tissues. Final characterization of the strain involved in these samples will require analysis of the features of the disease following infection of mice, but our data already emphasize the need to use the different available methods to define the molecular properties of abnormal PrP and its possible similarities with the BSE agent.

Prion diseases, or transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are neurodegenerative diseases which include scrapie of sheep and goats and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans. Epidemiological studies have failed to demonstrate any link between scrapie and CJD (36). Since the appearance of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle (45), other novel TSEs involving ruminants from zoological collections and feline species (1, 32, 35, 48) and humans (variant CJD) (21) have emerged. Strain typing studies with mice have shown that these new prion diseases are linked to the BSE agent (7) and are probably due to consumption of BSE-contaminated tissues. The BSE agent, whether isolated from primary cattle infection or from different naturally or experimentally exposed species, indeed shows remarkably uniform features following transmission to mice (7, 12, 17).

The origin of the cattle BSE agent remains unknown, but it most probably originated from adaptation and recycling of the sheep scrapie agent in cattle (46, 47). Irrespective of the origins of BSE in cattle, the susceptibility of sheep to BSE has been demonstrated by using several different routes of infection (including the oral route) (2, 14-16, 29). The possibility of spread of this agent to sheep flocks is therefore of considerable concern, as exposure to BSE-contaminated meat and bone meal in some flocks is a real possibility (8). Thus, the precise identification of the BSE agent in sheep is needed, particularly as it may represent a potential new source of contamination for human beings. This identification of BSE in sheep cannot be made by analysis of clinical signs, as BSE-infected sheep show signs similar to those observed in naturally occurring scrapie (2, 15, 25).

The biochemical analysis of abnormal prion protein (PrP), the only specific marker of these diseases (6), can potentially contribute to strain identification. Abnormal PrP is derived from a normal host protein named PrPc. The abnormal PrP is partially resistant to protease digestion (PrPres) and gives a 27- to 30-kDa fragment after proteinase K (PK) treatment (6); in rodent scrapie a sequence of 62 N-terminal amino acids is digested, leaving a core of 141 amino acids (33). By using the Western blotting method and specific antibodies directed against the core globular domain of the PrP, three fragments can be separated by their relative molecular weights; these correspond to the diglycosylated, monoglycosylated, and nonglycosylated forms of the protein. While high levels of diglycosylated PrPres were found in sheep experimentally infected with BSE, natural sheep scrapie and BSE of cattle could not be readily distinguished according to ratios of the different PrPres glycoforms (5, 40). Some studies have identified a lower molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrPres in variant CJD compared to most other forms of CJD in humans and also in experimentally BSE-infected sheep compared to natural scrapie cases (2, 9, 21, 40). However, in sheep, a low molecular mass has also been found in the experimental scrapie isolate CH1641 (2, 22, 23, 40), although some molecular differences from the BSE agent in sheep have been reported (40).

Recently, an immunohistochemical approach for identification of BSE in sheep has also been achieved by characterizing the epitopes of abnormal PrP present in neurons and also in phagocytic cells of the lymphoreticular system and brain. This method does not use protease treatment, and the term PrPd is used to describe the abnormal disease-specific accumulations of PrP seen by immunohistochemistry. However, by using different peptide-specific antibodies directed against the PK cleavage region of the PrP, a more extensive digestion of the abnormal PrP was revealed in tingible body macrophages (TBMs) in lymphoid tissues and in glial cells and neurons in the brains of BSE-infected sheep compared to natural scrapie cases (27, 28).

Taken together, all of the data strongly suggest that PrPres from animals or humans infected by the BSE agent is more susceptible to PK treatment than PrPres found in scrapie-infected animals. As a consequence, a larger segment of the N-terminal sequence of PrPres is removed by proteolytic treatment, leading to a loss of the corresponding epitopes. This has already been illustrated in previous studies showing that the epitope recognized by the P4 monoclonal antibody (20) was specifically unexposed in BSE-infected cattle and sheep while kept in scrapie-infected sheep, apart from the CH1641 experimental scrapie isolate (40). On the basis of such observations, a new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was developed, which checks for the presence of the octa-repeat sequence following PK treatment as a way to identify the BSE agent in sheep (39).

In order to identify potential BSE cases in flocks, a series of 214 scrapie samples from affected French flocks was analyzed by the ELISA technique. In this screening step, most of the brain samples behaved like conventional scrapie samples, but 18 of them showed an increased protease cleavage without reproducing the behavior observed in a BSE-infected sheep control. Interestingly, when tested by Western blotting, 2 of these 18 samples, both originating from the same flock, showed an unglycosylated band with a lower molecular mass than in other scrapie samples and similar to that found in BSE-infected sheep. A precise characterization of these two cases was made in comparison to experimental BSE in sheep and natural scrapie cases, by Western blotting and by using an immunohistochemical analysis of PrPd processing in phagocytic cells of the lymphoreticular system and in brain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A series of 214 French field sheep scrapie isolates, collected between 1991 and 1998 through the French surveillance network for suspect clinical cases (D. Calavas, AFSSA-Lyon, France), was first screened by use of the ELISA method to seek suspect cases with molecular features resembling those of experimentally BSE-infected sheep. Following analysis of the molecular masses for suspect cases by Western blotting, a panel of sheep scrapie cases was chosen for further detailed studies by using Western blotting and immunohistochemical methods, in comparison with experimentally BSE-infected sheep.

Sheep TSE isolates.

The sheep used in this study are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sheep used in the study

| Groupa | Identification no. (infection routeb) | Sheep breed | PrP genotype | Age at death (yr) or dpic | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SB1 (i.p.) | Lacaune | ARQ/ARQ | 672 dpi | France |

| SB3 (i.s.) | Lacaune | ARQ/ARQ | 1,444 dpi | France | |

| R1207 (i.c.) | Romney | ARQ/ARQ | 519 dpi | United Kingdom | |

| 2 | R680 | Suffolk | ARQ/ARQ | 892 days | United Kingdom |

| 3 | O100d | Manech Tête Rousse | VRQ/VRQ | 5 yr (1996) | France |

| O104d | Manech Tête Rousse | VRQ/VRQ | 2 yr (1997) | France | |

| O58 | Manech Tête Rousse | VRQ/VRQ | 4 yr (1996) | France | |

| O54 | Manech Tête Rousse | ARQ/XRQ | 2 yr (1996) | France | |

| 4 | O76 | Manech Tête Rousse | ARQ/ARQ | 2 yr (1996) | France |

| O180 | Texel × Charollais | ARH/VRQ | Preclinical (1997) | France | |

| O175 | Texel × Charollais | ARQ/VRQ | 2 yr (1997) | France | |

| 7028 | Romanov × Ile de France | ARQ/VRQ | Preclinical (1999) | France |

Group 1, experimentally infected sheep with BSE; group 2, natural scrapie case from the United Kingdom; group 3, naturally infected sheep from a single French flock; group 4, naturally infected sheep from three separate French flocks.

i.p., intraperitoneal infection; i.s., intrasplenic infection; i.c., intracerebral infection.

dpi, day postinfection.

Sheep with unusual Western blot profile.

(i) Group 1.

Group 1 consisted of sheep experimentally infected with BSE. Two Lacaune sheep with a PrP genotype known to give sensitivity to natural scrapie (ARQ/ARQ at codons 136, 154, and 171) were inoculated by either the intraperitoneal or intrasplenic route with 0.5 g of a brain homogenate from a French BSE-affected cow. One animal died at 672 days postinoculation (after intraperitoneal infection), and the other was euthanatized at 1,444 days postinoculation (after intrasplenic infection) after having shown clinical signs of neurological disease. Sheep R1207 was an ARQ/ARQ Romney sheep experimentally challenged intracerebrally with a 10−4 dilution of BSE-infected brain homogenate. The animal developed clinical disease and was euthanatized at 519 days postinoculation. Typical vacuolar pathology, brain, and peripheral PrPd accumulation were present in all three sheep experimentally infected with BSE.

(ii) Group 2.

Group 2 consisted of one sheep with natural scrapie. R680 was a naturally diseased ARQ/ARQ British Suffolk sheep which died 892 days after birth. The animal showed typical vacuolar pathology and PrPd accumulation as previously characterized in this flock (18).

(iii) Group 3.

Group 3 consisted of four Manech Tête Rousse sheep from the same affected flock for which the first official declaration of scrapie occurred in 1996. These sheep were euthanatized between December 1996 and February 1997 when they were between 2 and 5 years of age and presenting with clinical signs of scrapie. The histological examination of fixed brain stems confirmed the diagnosis of TSE. Only frozen frontal brain regions were available for biochemical studies. Of these four samples, two (O100 and O104) showed moderate or severe autolysis as determined by routine histology methods. Preliminary studies of PrPres patterns in sheep by using Western blotting had shown an usual pattern in the O100 and O104 isolates, with a low molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrPres, compared to previous data obtained in the laboratory (2).

(iv) Group 4.

Group 4 included four sheep with histologically confirmed TSE detected from three other outbreaks within the French surveillance network. Biochemical studies were also performed on frontal brain regions, and histological analysis was performed on hindbrains.

ELISA procedure.

The ELISA used in this study was designed to distinguish BSE from scrapie. It is similar in design to a rapid test used on a large scale in Europe (the Bio-Rad test formally developed by CEA). In this test PrPres is first purified and concentrated before being denatured and analyzed by using a sandwich immunoassay (19). The capture antibody, immobilized into the solid phase, recognizes an epitope in the N terminus of the PrP, whereas the tracer antibody binds to the C-terminal moiety. In the Bio-Rad tests used for the postmortem diagnosis of BSE in cattle, the PK digestion, which is a key step in this assay, is done in a controlled medium (a mixture of detergents and chaotropic agents) so that the N-terminal epitope recognized by the capture antibody is preserved during the proteolysis. By varying the conditions of PK treatment (notably by altering the nature and concentration of the detergents and chaotropic agents and the PK concentration), we have found that the PrPres associated with the BSE agent was more sensitive to PK digestion than other prion strains. Conditions were thus defined in which the epitope recognized by the capture antibody (here the octa-repeat sequence) was eliminated by the PK treatment in the BSE agent but remained preserved in scrapie strains. In practice, we used two sets of conditions of PK treatment. Compared to the Bio-Rad test validated for detection of PrPres in cattle BSE, this typing involves several modifications, including a change in the antibodies used for the sandwich immunoassay and the extensive use of PK inhibitors in order to have a better control of PK digestion. A more detailed description of this test will be given elsewhere (S. Simon et al., unpublished data). Under the first set of digestion conditions (set A), the critical epitope is conserved whatever the strain is. In the second set of conditions (set A′), the treatment preferentially eliminates the N-terminal epitope described above in BSE but not in scrapie. Ratios between the two measurements (A/A′) were determined for differential detection of BSE and natural scrapie. This ratio is equal (or close) to unity with most natural scrapie isolates and is significantly above unity with the BSE agent.

Western blot procedure.

Brain samples were homogenized at 10% in a 5% glucose solution by forcing the brain suspension through a 0.4-mm-diameter needle. A 330-μl volume was made up to 1.2 ml in 5% glucose before incubation with PK (10 μg/100 mg of brain tissue) (Roche) for 1 h at 37°C. N-Lauroyl sarcosyl at 30% (600 μl; Sigma) was added. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, samples were centrifuged at 200,000 × g for 2 h on a 10% sucrose cushion in a Beckman TL100 ultracentrifuge. The pellets were resuspended and heated for 5 min at 100°C in 50 μl of denaturing buffer (sodium dodecyl sulfate, 4%; β-mercaptoethanol, 2%; glycine, 192 mM; Tris, 25 mM; sucrose, 5%).

Samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted to nitrocellulose membranes in transfer buffer (Tris, 25 mM; glycine, 192 mM; isopropanol, 10%) at a constant 400 mA for 1 h. The membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline-Tween 20 (0.1%) (PBST). After two washes in PBST, the membranes were incubated (1 h at room temperature) with Bar233 monoclonal antibody (1/5,000 in PBST), which was raised against an ovine histidine-tagged recombinant protein (3) and recognizes the ovine PrP sequence from position 144 to 155 (FGNDYEDRYYRE) (5), or with P4 monoclonal antibody (1/5,000), which was prepared against a synthetic ovine PrP sequence from position 89 to 04 (GGGGWGQGGSHSQWNK) (from R-biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany) (20). After three washes in PBST, the membranes were incubated (30 min at room temperature) with peroxidase-labeled conjugates against rabbit or mouse immunoglobulins (1/2,500 in PBST) (Clinisciences). After three washes in PBST, bound antibodies were then detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) or Supersignal (Pierce) chemiluminescent substrates. Migrations of the unglycosylated PrPres were compared for repeated runs of the samples, either on films after exposure of the membranes on Biomax MR Kodak films (Sigma) or by using pictures obtained with the Fluor-S Multimager (Bio-Rad). Molecular masses of the three PrPres glycoforms were determined in some selected samples by comparison of at least eight different runs of the samples of the center positions of the PrPres bands with a biotinylated marker (SDS-6B; Sigma), using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The intensities of PrPres signals were assessed by using the Fluor-S-Multimager software, allowing comparisons of reactivities with either Bar233 or P4 monoclonal antibody. Scoring of the reactivities used according to the decrease of P4 labeling: −, no labeling; ±, light labeling; +, moderate labeling; and ++, intense labeling. For quantitative studies of glycoform ratios, chemiluminescent signals corresponding to the three glycoforms of the protein were quantified by using a Fluor S-Multimager analysis system. Glycoform ratios were expressed as mean percentages (± standard errors) of the total signal for the three glycoforms (high, low, and unglycosylated), from at least eight different runs of the samples.

Immunohistochemical procedure.

Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and then routinely embedded in paraffin wax. To ensure adhesion, tissues sections (5 μm thick) were collected onto pretreated glass slides (StarFrost; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) and dried. Once they were dewaxed, rehydrated sections were used for disease-specific PrPd immunohistochemical analysis. Briefly, sections were immersed in 98% formic acid for 5 min, washed in running tap water, and then immersed in 0.2% citrate buffer to be autoclaved for 30 min at 121°C. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by using 1% H2O2 in ethanol for 20 min. After rinsing in tap water and in PBST (0.2% Tween 20) buffer, nonspecific tissue antigens were blocked in normal horse serum for 60 min. Incubation with primary antibody was then performed overnight at 4°C. Different PrP antibodies (Table 2) were used, with the following specific concentrations: R521, 1/10,000; P4, 1/2,000; 505, 1/10,000); and R486, 1/10,000. The first three are directed against the upstream segment of the flexible tail (37) of the abnormal isoform of PrP, and R486 recognizes a more resistant region of the abnormal PrP (28). Bound antibodies were labeled by means of a commercial immunoperoxidase technique (Vector-Elite ABC; Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, United Kingdom). Once labeled, sections were immersed in 0.5% copper sulfate to enhance the intensity of the reaction product. Slides were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin.

TABLE 2.

Antibodies used and their specificity for PrP epitopes

| Antibody | Type | Immunogen position (PrP) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| P4 | Monoclonal | 89-104 (ovine) PrP | 20 |

| R521 | Polyclonal | 94-105 (ovine) | 41 |

| 505 | Polyclonal | 100-111 (ovine) | 41 |

| Bar233 | Monoclonal | 145-156 (ovine) | Unpublished data |

| R486 | Polyclonal | 221-234 (ovine) | 28 |

The intensity of intraneuronal PrPd labeling was subjectively estimated according to criteria presented in a previous paper (28): −, no labeling; ±, trace of light labeling; +, light labeling; ++, moderate labeling; and +++, intense labeling over most of the target site.

RESULTS

ELISA screening of French field sheep isolates.

The experimental ovine BSE samples (group 1, SB1 and SB3) were used as internal controls in each series of measurements, and these were characterized by an A/A′ ratio of 3.3 ± 0.8 (absolute values of between 2.3 and 5.3). Most of the scrapie isolates had A/A′ ratios of close to 1, while 18 had ratios that were consistently and repeatedly greater than 1 (ranging from 1.4 to 3.1). Due to interassay variations, the two populations (experimental BSE and field isolates) overlapped; however, in a given series, none of the field isolates behaved like the experimental BSE control. For instance, in the series including the field sample with an A/A′ ratio of 3.1, the corresponding BSE value was 4.9. A more detailed description of results obtained for field sheep samples and experimental BSE in sheep will be given elsewhere (Simon et al., unpublished data). However, when analyzed by Western blotting, 2 of the 18 samples (O100 and O104, both originating from the same flock [group 3]) giving the highest ELISA ratios showed a lower apparent molecular weight of the unglycosylated PrPres. These two isolates were then characterized in more detail by Western blotting and immunohistochemical methods together with a panel of other sheep isolates, including those from field cases and experimental BSE in sheep, as described in Materials and Methods and in Table 1.

Western blotting study of sheep TSE isolates.

All but one (O180, group 4) of the eight field scrapie samples studied by Western blotting gave a characteristic protein banding pattern corresponding to the three glycoforms of PrPres, with the diglycosylated (top), the monoglycosylated (middle), and the unglycosylated (bottom) bands (Fig. 1). It should be noted that samples O100 and O104 (group 3), strongly autolysed, showed only low levels of PrPres, and smears were regularly observed on Western blotting.

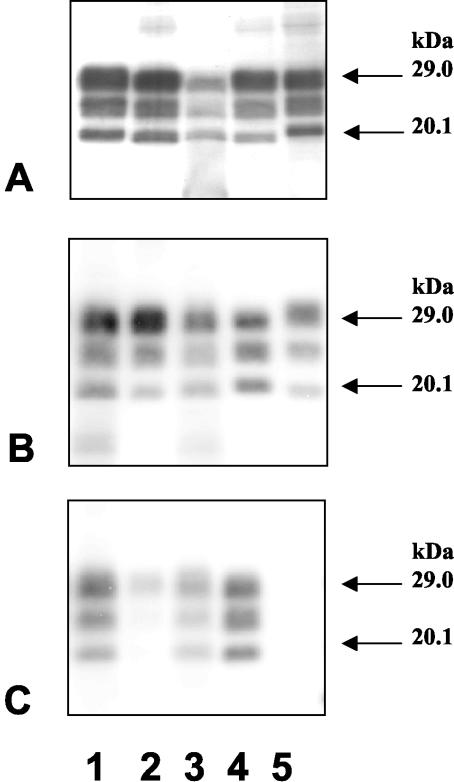

FIG. 1.

Western blotting analysis of PrPres with Bar233 (A and B) or P4 (C) monoclonal antibody. (A) Lanes: 1, cattle BSE; 2, BSE-infected sheep (intraperitoneal inoculation); 3, sheep scrapie case O100; 4, BSE-infected sheep (intrasplenic inoculation); 5, natural scrapie case. (B and C) Lanes: 1, sheep scrapie case O100; 2, BSE-infected sheep (intraperitoneal inoculation); 3, sheep scrapie case O104; 4, sheep scrapie case O58; 5, cattle BSE.

The unglycosylated PrPres fragment from the two sheep experimentally infected with French cattle BSE (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 4) had a low molecular mass, slightly lower than that of PrPres from a BSE-infected cow (Fig. 1A, lane 1). The unglycosylated PrPres fragments of six of eight French scrapie-affected sheep had a clearly distinct and higher molecular mass compared with PrPres from BSE-infected animals (Fig. 1A and B, lanes 5 and 4, respectively), as previously described (2). Repeated runs of samples from the two other naturally infected French sheep (O100 and O104) from the same Manech Tête Rousse flock showed, from extractions from different regions of the available frozen brain sample, an unglycosylated PrPres fragment with a molecular mass similar to that found in BSE-infected sheep (Fig. 1A and B). These results were reproduced in two different laboratories.

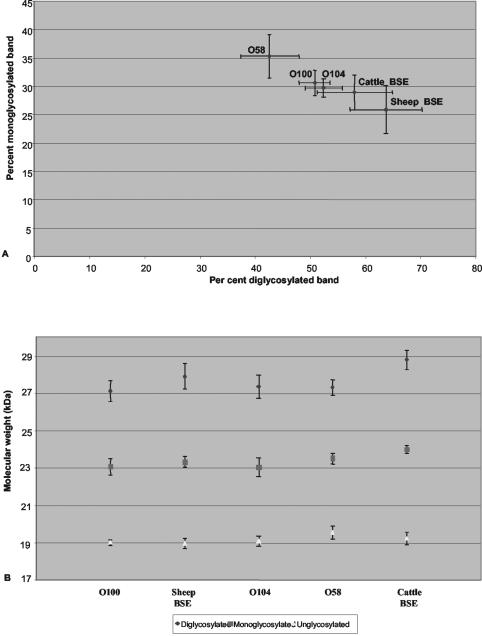

The molecular masses and glycoform ratios obtained from repeated runs of these two samples (O100 and O104) are shown in Fig. 2B, in comparison with another sample from a sheep (O58) with the same homozygous V136 R154 Q171 genotype from the same flock and with BSE infection in cattle or in sheep.

FIG. 2.

Glycoform ratios (A) and molecular masses (B) (means ± standard deviations) of PrPres detected by Western blotting with the Bar233 monoclonal antibody in sheep infected with natural scrapie or experimental BSE and in cattle with BSE.

Comparison of the intensities of PrPres signals detected by using the Bar233 and P4 monoclonal antibodies showed a strong lowering of PrP signals with the P4 antibody in BSE-infected sheep (Fig. 1C, lane 2). Scoring of the differential reactivities (P4/Bar233) for the different samples is indicated in Fig. 1C. A lowering of P4 immunoreactivity was also observed in O100 and O104 when compared in repeated runs of the samples with the sample O58, which shows unglycosylated PrPres a higher molecular mass. This decrease was, however, clearly less pronounced than that observed with BSE-infected sheep. Cattle PrPres was not detected with P4 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1C, lane 5). The glycoform ratios observed following PrPres detection with Bar233 antibody (Fig. 2A) showed very high levels of diglycosylated PrPres in BSE-infected sheep, which was at least twice as abundant as the monoglycosylated form, in contrast with natural scrapie cases, including O100 and O104. PrPres from BSE-infected cattle showed intermediate levels of glycosylation, overlapping with those of natural scrapie cases O100 and O104.

Immunohistochemical study. (i) Lymphoid organs: TBMs.

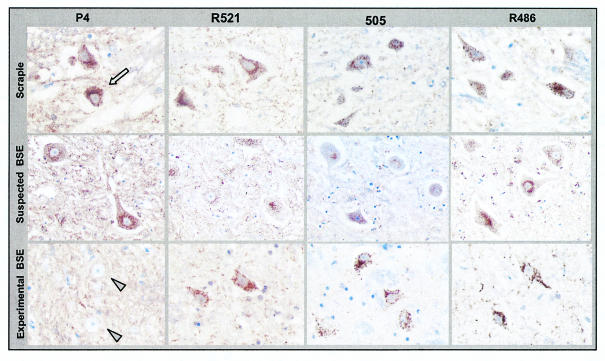

Lymphoid organ samples were immunolabeled with R521, P4, 505, and R486 antibodies. The results show that most antibodies labeled follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and TBMs with different intensities (Fig. 3).

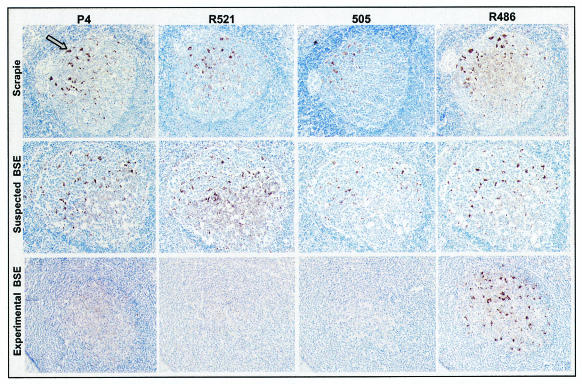

FIG. 3.

Comparison of immunolabeling of PrPd in lymph nodes with the P4, R521, 505, and R486 antibodies on serial sections. TBMs were labeled with all of the antibodies used in the natural cases of sheep TSE (brown deposits; arrow) (row 1) and in O100 (row 2) but not in experimentally infected sheep with BSE (row 3), where only R486 gave labeling. In row 2, the O100 sheep follicle shows numerous tissue spaces within the light zone and also shows separation of the follicular capsule from adjacent paracortical lymphocytes. These features are not present in the other two samples shown and are caused by postmortem changes consistent with autolysis. A ×10 objective was used.

In all samples obtained from naturally exposed sheep (groups 2, 3, and 4), TBMs were labeled with all of the antibodies used (Fig. 3). This same pattern was observed for the two Manech Tête Rousse sheep (O100 and O104), which in Western blotting showed unglycosylated bands similar to those from BSE-infected sheep (Fig. 3). In contrast, TBMs of sheep experimentally infected with BSE (group 1) were labeled only with antibody R486 (Fig. 3). These different patterns of TBM labeling, for natural TSE or experimental BSE, were found in all lymph node, spleen, or Peyer's patch samples examined. No differences were observed between natural TSE cases from France or the United Kingdom or between BSE-infected sheep, of different breeds and infected via different routes with either French or British BSE cattle samples.

(ii) Central nervous system.

At the level of the obex sections, the patterns of PrPd immunolabeling produced by different antibodies were compared for the different sheep analyzed (natural sheep TSE isolates and experimental BSE in sheep). For each brain stem sample, the dorsal nucleus vagus (X) and the hypoglossal (XII) and olivary nuclei were studied in order to characterize the intraglial and intraneuronal PrPd labeling patterns.

(a) Intraglial labeling.

PrPd was detected with R521, P4, 505, and R486 antibodies in all naturally occurring TSE cases from the United Kingdom and France analyzed (groups 2, 3, and 4) (Fig. 4). The precise identification of the labeling was always indicated by the presence of a nucleus (in blue) closely associated with a coarse particulate type of PrPd deposit (brown deposits) (Fig. 4). This same pattern, with a similar intensity, was found for TSE cases O100 and O104 (Fig. 4). In contrast, in all BSE-affected sheep, whereas the 505 and R486 antibodies produced a similar intracellular PrPd labeling of glial cells, P4 and R521 did not produce this type of labeling (Fig. 4).

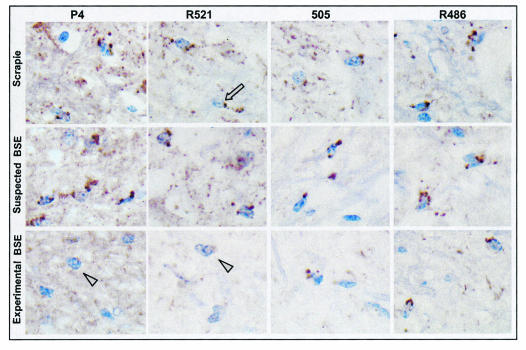

FIG. 4.

Comparison of intraglial PrPd immunolabeling (brown deposits; arrow) with the P4, R521, 505, and R486 antibodies on serial sections of brain stem. Intraglial PrPd was labeled with all of the antibodies used in the cases of natural sheep TSE (row 1) and in O100 (row 2) but not in sheep experimentally infected with BSE (row 3) (arrowheads), where only R486 and 505 gave labeling of glia. A ×100 objective was used.

(b) Intraneuronal labeling.

The intracytoplasmic labeling of PrPd in neurons in the dorsal (parasympathetic) nucleus of the vagal nerve (X) and the hypoglossal (XII) and olivary nuclei was studied. In brain stem samples from natural TSE cases, the P4, R521, 505, and R486 antibodies produced an intracytoplasmic labeling of neurons (Fig. 5); the labeling being more intense with both P4 and R486. Of the three brain stem nuclei studied, the intensity of this intracytoplasmic labeling was generally more conspicuous in the olivary nucleus (Table 3). This same pattern with a similar intensity was found for natural TSE cases O100 and O104 (Fig. 5; Table 3). For the BSE-infected sheep samples, only R521, 505, and R486 produced an intracytoplasmic labeling of neurons, with a more intense labeling observed with R486; P4 did not producing this labeling (Fig. 5; Table 3).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of intraneuronal PrPd immunolabeling (brown deposits; arrow) with the P4, R521, 505, and R486 antibodies on serial sections of brain stem. Intraneuronal PrPd was labeled with all of the antibodies used in the natural cases of sheep TSE (row 1) and in O100 (row 2) but not in sheep experimentally infected with BSE (row 3), where no intraneuronal immunolabeling was obtained with P4 (arrowheads). A ×40 objective was used.

TABLE 3.

Comparative intensity of intraneuronal immunolabeling in dorsal nucleus vagus (X), hypoglossal nucleus (XII), and olivary nucleus with the P4 and R486 antibodies

| Animala | Labelingb of:

|

Antibody | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | XII | Olivary nucleus | ||

| SB1 | + | NDc | +++ | R486 |

| − | ND | +/− | P4 | |

| SB3 | ++ | ++ | +++ | R486 |

| − | +/− | +/− | P4 | |

| R1207 | ++ | ++ | +++ | R486 |

| − | − | +/− | P4 | |

| R680 | + | + | +++ | R486 |

| + | + | +++ | P4 | |

| O100 | ++ | ++ | + | R486 |

| ++ | ++ | +/− | P4 | |

| O104 | ++ | +++ | +++ | R486 |

| ++ | ++ | +/− | P4 | |

| O58 | ++ | ++ | +++ | R486 |

| ++ | +++ | +++ | P4 | |

| O54 | ++ | + | +++ | R486 |

| ++ | + | +++ | P4 | |

| O76 | ++ | ++ | +++ | R486 |

| ++ | ++ | +++ | P4 | |

| O180 | ++ | + | ++ | R486 |

| ++ | + | +/− | P4 | |

SB1 and SB3 are sheep from France that were experimentally infected with BSE by the intraperitoneal and intrasplenic routes, respectively; R1207 is a sheep from the United Kingdom that was experimentally infected with BSE; and R680 is a sheep from the United Kingdom with natural scrapie. All others are sheep from France with natural TSE.

See Materials and Methods.

ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

We describe features of the abnormal PrP accumulating in the brains of sheep with natural TSE or with experimental BSE, originating from either British or French sources, determined by using ELISA and Western blotting detection of PrPres or immunohistochemical detection of PrPd. The specific Western blotting features of PrPres had already been described for BSE-infected sheep of different breeds from both French and United Kingdom sources, which typically showed a lower molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrPres than seen for natural scrapie cases or for cattle BSE (2, 22, 40). We also confirmed in this study that PrPres was only faintly labeled by the P4 monoclonal antibody, as previously described for sheep infected with British cattle BSE by using a modification of a rapid Western blotting diagnosis test for BSE (40). These biochemical features were identical in the two Lacaune sheep inoculated with French cattle BSE agent by the intraperitoneal or intrasplenic route in this study. As also previously reported (40), the decrease of P4 labeling was also less in BSE-infected sheep than in cattle BSE, which might be linked to the different sequences in this region of the protein in the two species. More importantly, this work also demonstrates the same differences in the immunohistochemical labeling of PrPd in phagocytic cells of the lymphoreticular system and brain and in neurons in BSE-infected sheep inoculated with French or British cattle BSE agent, compared with naturally occurring scrapie cases, as previously observed (27, 28). Whereas these differences seem to be independent of the breed and route of infection, these results, consistent with a common origin of French and British BSE, further suggest that characterization of the protease cleavage site could aid identification of potential BSE cases in sheep.

The identification of the precise cell type accumulating PrPd in TSE-affected sheep can be based on the shape and the localization of the implicated cells or on specific markers. In lymphoid organs, FDCs and TBMs were identified as accumulating abnormal PrP (31, 41), as well as different cell populations in the central nervous system (18, 38). Extracellular forms of PrPd released around neurons, astrocytes, and FDCs of sheep infected with scrapie are present as the full-length protein (26). In TBMs, glial cells, and neurons, intralysosomal PrPd appeared to be truncated by protein-degrading enzymes, and antibodies such as BG4 and FH11 did not label PrPd in these cells, as they are directed against the downstream segment of the N-terminal end of PrP (28, 37). It is therefore suggested that the N terminus of PrPd acquired from the extracellular space is digested within phagocytic cell lysosomes. A more detailed analysis using P4, R521, and 505 antibodies directed against the upstream segment of the flexible tail of the PrP molecule permits differentiation of BSE in sheep from different sheep scrapie sources (27, 28). This differentiation is possible because the degradation of the abnormal PrP in lysosomes seems to be more extensive in BSE infection than in natural scrapie. In sheep BSE, the P4, R521, and 505 antibodies do not label PrPd in TBMs, in contrast to what was observed for scrapie. The specific degradation of PrPd is, however, variable in different cells, being more extensive in TBMs, less so in glial cells, and less again in neurons. The precise site of truncation delimiting the most resistant domain of the abnormal PrP is therefore difficult to determine because of this cellular variation of PrPd labeling and because results can vary according to pretreatments used for PrPd antigen retrievals. Nevertheless, all of the results suggest that a more extensive truncation of the PrPd occurred in phagocytic cells and in neurons in BSE-infected sheep than with scrapie infection, and these immunohistochemical results are consistent with those obtained by using the Western blotting method after PK treatment. The more extensive protease digestion of the PrPres extracted from BSE-infected animals has been characterized by epitope mapping following Western blotting detection or by N-terminal sequencing of the PrPd protein following transmission in sheep (40), mice (4), and humans (34).

Following an initial screening by using an ELISA technique aimed at identifying the BSE agent in sheep based on the reactivity against an epitope close to the PK cleavage site, Western blotting studies of PrPres extracted from the brains of French sheep field TSE cases led to the finding of two particular cases (O100 and O104), of the same genotype (VRQ/VRQ) and from a same flock, that showed some similarities with BSE in sheep regarding the molecular mass of the unglycosylated PrPres. Other cases analyzed in this study (O58 and O54 [group 3], including a sheep of this same genotype from this flock, and four sheep from other TSE outbreaks [group 4]) showed the PrPres pattern previously described for natural scrapie cases, with a clearly distinct and higher molecular mass compared to that for BSE in sheep (2, 22, 40). So far, a single sheep TSE isolate, CH1641, with close similarities in the migration of unglycosylated PrPres to that found for BSE in sheep has been described. CH1641 has been experimentally maintained by serial passages in sheep from a scrapie case that occurred in the United Kingdom in the 1970s (2, 13, 23). The BSE agent and CH1641 in sheep also shared a strongly decreased recognition by the P4 monoclonal antibody compared to that in natural scrapie cases (40). P4 labeling was also decreased in O100 and O104 compared to a scrapie control of the same genotype and from the same flock, but to a lesser extent than for BSE in sheep. These results are in good agreement with those obtained by ELISA characterization of protease digestion, showing an increased protease digestion without reaching the level found for BSE in sheep. In contrast with immunohistochemical methods, biochemical analysis does not allow characterization of the cell types in which PrPres accumulates. The natural TSE sheep samples described above were studied by immunohistochemical methods, using antibodies close to the protease cleavage site, in brain and lymphoid tissues. All of them, including those from the two affected sheep with unusual Western blotting patterns, O100 and O104, had a typical scrapie-like signature by immunohistochemical analysis. We also observed differences of glycoform ratios between natural sheep TSE cases, including O100 and O104, and experimental BSE in sheep. These differences, mainly linked to the very high levels of diglycosylated PrPres in BSE-infected sheep, are quite consistent with those previously described for British cases of natural scrapie or experimental BSE, using a modified version of the Western blotting Prionics test and 6H4 antibody (40). Together these data suggest that O100 and O104 do not share all the features found in BSE in sheep. Nevertheless, criteria which allow the distinction of ovine BSE from scrapie need to be more clearly defined, especially when quantitative assessment of the glycoform ratios or differential reactivities of antibodies directed toward the protease cleavage sites are considered, as these methods are difficult to standardize.

The significance of the biochemical properties of sheep isolates O100 and O104 is unclear, and several hypothesis can be considered to explain these observations (1). Since the nonfixed brain material from these two sheep was autolysed, an endogenous protease action, might have predigested the tissue and abnormal PrP during the autolysis process, thereby facilitating or enhancing the PK action. However, among the frozen samples received in the laboratory for diagnosis, a number of field samples were also autolysed without showing any unusual protease cleavage. Similarly, use of variable concentrations of PK did not lead to changes in the molecular weight, and only the signal intensity of PrPres detection was modified (24, 30).

Several procedural steps which contribute to variations in electrophoretic mobility or/and glycoform ratios have previously been identified. These included metal ion chelations, prior to PK treatment (43), PrPres extraction under different pH conditions (49, 50), and the use of sodium phosphotungstic acid precipitation before PK treatment (44). Whereas in these situations changes in the PrPres patterns were the result of modifications in the laboratory methods, it should be emphasized that they could reveal a genuine biological diversity of these diseases.

Our results could be explained by the presence in these sheep of a particular strain of TSE agent with some properties close to those found in the BSE agent and in the CH1641 scrapie isolate. While the unusual electrophoretic features were similarly found in two sheep of the same genotype in the same flock, but not in some other sheep of this flock, characterization of the infectious agent involved in these scrapie cases is required, using mouse transmission studies in a panel of mice with different prn-p genotypes, as used for strain typing (7), and in other transgenic mouse models (10, 11, 42).

In conclusion, our results have reinforced the idea that uniform features could be found in sheep experimentally infected with BSE, including those infected with BSE from different geographical origins. Importantly, through the study of a panel of field sheep TSE cases, two with some biochemical features similar to those of ovine BSE were found. These two samples were initially identified from a group of 18 following application of a rapid ELISA test, which may be useful for screening of large series of samples. The accurate identification of the infectious agent strain in sheep, however, requires a careful analysis by the different available methods, including those which aid characterization of different molecular properties that may characterize TSE strains and mouse transmission studies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Martin Groschup for the P4 antibody, to Jan Langeveld for gifts of the R521 and 505 antibodies, and to Roy Jackman for R486. We gratefully acknowledge Didier Calavas for analysis of the data obtained from the French scrapie surveillance network and Dominique Canal and Jérémy Verchère for technical assistance.

Stéphane Lezmi was financially supported by a grant from Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Aliments (AFSSA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Baron, T., P. Belli, J.-Y. Madec, F. Moutou, C. Vitaud, and M. Savey. 1997. Spongiform encephalopathy in an imported cheetah in France. Vet. Rec. 141:270-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron, T., J.-Y. Madec, D. Calavas, Y. Richard, and F. Barillet. 2000. Comparison of French natural scrapie isolates with BSE and experimental scrapie infected sheep. Neurosci. Lett. 284:175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron, T. G. M., D. Betemps, H. Martin, M. H. Groschup, and J.-Y. Madec. 1999. Immunological characterization of the sheep prion protein expressed as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 25:379-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron, T. G. M., and A. G. Biacabe. 2001. Molecular analysis of the abnormal prion protein during coinfection of mice by bovine spongiform encephalopathy and a scrapie agent. J. Virol. 75:107-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron, T. G. M., J.-Y. Madec, and D. Calavas. 1999. Similar signature of the prion protein in natural sheep scrapie and bovine spongiform encephalopathy-linked diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3701-3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton, D. C., M. P. McKinley, and S. B. Prusiner. 1982. Identification of a protein that purifies with the scrapie prion. Science 218:1309-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce, M. 1996. Strain typing studies of scrapie and BSE, p. 223-236. In H. Baker and R. M. Ridley (ed.), Prion diseases. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J.

- 8.Butler, D. 1998. Doubts over ability to monitor risks of BSE spread to sheep. Nature 395:6-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collinge, J., K. C. L. Sidle, J. Meads, J. Ironside, and A. F. Hill. 1996. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ′new variant' CJD. Nature 383:685-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crozet, C., A. Bencsik, F. Flamant, S. Lezmi, J. Samarut, and T. Baron. 2001. Florid plaques in ovine PrP transgenic mice infected with an experimental ovine BSE. EMBO Rep. 21:952-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crozet, C., F. Flamant, A. Bencsik, D. Aubert, J. Samarut, and T. Baron. 2001. Efficient transmission of two different sheep scrapie isolates in transgenic mice expressing the ovine PrP gene. J. Virol. 75:5328-5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster, J. D., M. Bruce, I. Mc Connell, A. Chree, and H. Fraser. 1996. Detection of BSE infectivity in brain and spleen of experimentally infected sheep. Vet. Rec. 138:546-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster, J. D., and A. G. Dickinson. 1988. The unusual properties of CH1641, a sheep-passaged isolate of scrapie. Vet. Rec. 123:5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster, J. D., J. Hope, and H. Fraser. 1993. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy to sheep and goats. Vet. Rec. 133:339-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster, J. D., D. Parnham, A. Chong, W. Goldmann, and N. Hunter. 2001. Clinical signs histopathology and genetics of experimental transmission of BSE and natural scrapie to sheep and goats. Vet. Rec. 148:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster, J. D., D. W. Parnham, N. Hunter, and M. Bruce. 2001. Distribution of the prion protein in sheep terminally affected with BSE following experimental oral transmission. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2319-2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser, H., M. E. Bruce, A. Chree, I. McConnell, and G. A. Wells. 1992. Transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy and scrapie to mice. J. Gen. Virol. 73:1891-1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez, L., S. Martin, I. Begara-McGorum, N. Hunter, F. Houston, M. Simmons, and M. Jeffrey. 2002. Effects of agent strain and host genotype on PrP accumulation in the brain of sheep naturally and experimentally affected with scrapie. J. Comp. Pathol. 126:17-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grassi, J., C. Créminion, and Y. Frobert. 2000. Specific determination of the proteinase K-resistant form of the prion protein using two-site immunometric assays. Application to the post-mortem diagnosis of BSE. Arch. Virol. 16:197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harmeyer, S., E. Pfaff, and M. H. Groschup. 1998. Synthetic peptide vaccines yield monoclonal antibodies to cellular and pathological prion proteins of ruminants. J. Gen. Virol. 79:937-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill, A., M. Desbruslais, S. Joiner, K. C. L. Sidle, I. Gowland, and J. Collinge. 1997. The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature 389:448-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill, A. F., K. C. L. Sidle, S. Joiner, P. Keyes, T. C. Martin, M. Dawson, and J. Collinge. 1998. Molecular screening of sheep for bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Neurosci. Lett. 255:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hope, J., S. C. E. R. Wood, C. R. Birkett, A. Chong, M. E. Bruce, D. Cairns, W. Goldmann, N. Hunter, and C. J. Bostock. 1999. Molecular analysis of ovine prion protein identifies similarities between BSE and an experimental isolate of natural scrapie, CH1641. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horiuchi, M., T. Nemoto, N. Ishiguro, H. Furuoka, S. Mohri, and M. Shinagawa. 2002. Biological and biochemical characterization of sheep scrapie in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3421-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houston, E. F., and M. B. Gravenor. 2003. Clinical signs in sheep experimentally infected with scrapie and BSE. Vet. Rec. 152:333-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffrey, M., C. M. Goodsir, A. Holliman, R. J. Higgins, M. E. Bruce, P. A. McBride, and J. R. Fraser. 1998. Determination of the frequency and distribution of vascular and parenchymal amyloid with polyclonal and N-terminal-specific PrP antibodies in scrapie-affected sheep and mice. Vet. Rec. 142:534-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeffrey, M., S. Martin, and L. Gonzalez. 2003. Cell-associated variants of disease-specific prion protein immunolabelling are found in different sources of sheep transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1033-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeffrey, M., S. Martin, L. Gonzalez, S. J. Ryder, S. J. Bellworthy, and R. Jackman. 2001. Differential diagnosis of infections with the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and scrapie agents in sheep. J. Comp. Pathol. 125:271-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeffrey, M., S. Ryder, S. Martin, S. A. C. Hawkins, L. Terry, C. Berthelin-Baker, and S. J. Bellworthy. 2001. Oral inoculation of sheep with the agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). 1. Onset and distribution of disease-specific PrP accumulation in brain and viscera. J. Comp. Pathol. 124:280-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuczius, T., and M. H. Groschup. 1999. Differences in proteinase K resistance and neuronal deposition of abnormal prion proteins characterize bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) and scrapie strains. Mol. Med. 5:406-418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lezmi, S., A. Bencsik, and T. Baron. 2001. CNA42 monoclonal antibody identifies FDC as PrPsc accumulating cells in the spleen of scrapie affected sheep. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 82:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lezmi, S., A. Bencsik, E. Monks, T. Petit, and T. Baron. 2003. First case of feline spongiform encephalopathy in a captive cheetah born in France—PrPsc analysis in various tissues revealed unexpected targeting of kidney and adrenal gland. Histochem. Cell Biol. 119:415-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oesch, B., D. Westaway, M. Wälchli, M. P. McKinley, S. B. Kent, R. Aebersold, R. A. Barry, P. Tempst, D. B. Teplow, L. E. Hood, S. B. Prusiner, and C. Weissmann. 1985. A cellular gene encodes scrapie PrP 27-30 protein. Cell 40:735-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parchi, P., W. Q. Zou, W. Wang, P. Brown, S. Capellari, B. Ghetti, N. Kopp, W. J. Schulz-Schaeffer, H. A. Kretzschmar, M. W. Head, J. W. Ironside, P. Gambetti, and S. G. Chen. 2000. Genetic influence on the structural variations of the abnormal prion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10168-10172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peet, R., and J. Curran. 1992. Spongiform encephalopathy in an imported cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). Aust. Vet. J. 69:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prusiner, S. B. 1997. Prion diseases and the BSE crisis. Science 278:245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riek, R., S. Hornemann, G. Wider, R. Glockshuber, and K. Wüthrich. 1997. NMR characterization of the full-length recombinant murine prion protein mPrP(23-231). FEBS Lett. 413:282-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryder, S. J., Y. I. Spencer, P. J. Bellerby, and S. A. March. 2001. Immunohistochemical detection of PrP in the medulla oblongata of sheep: the spectrum of staining in normal and scrapie-affected sheep. Vet. Rec. 148:7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, S., E. Comoy, N. Morel, J. Y. Madec, T. Baron, J. P. Deslys, and J. Grassi. 2003. Identification of the BSE strain in mouse and sheep using a rapid enzyme immunoassay. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 29:207-208. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stack, M. J., M. J. Chaplin, and J. Clark. 2002. Differentiation of prion protein glycoforms from naturally occurring sheep scrapie, sheep-passaged scrapie strains (CH1641 and SSBP1), bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) cases and Romney and Cheviot breed sheep experimentally inoculated with BSE using two monoclonal antibodies. Acta Neuropathol. 104:279-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Keulen, L. J. M., B. E. C. Schreuder, R. H. Meloen, G. Mooij-Harkes, M. E. W. Vromans, and J. P. M. Langeveld. 1996. Immunohistochemical detection of prion in lymphoid tissues of sheep with natural scrapie. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1228-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilotte, J. L., S. Soulier, R. Essalmani, M. G. Stinnakre, D. Vaiman, L. Lepourry, J. C. DaSilva, N. Besnard, M. Dawson, A. Buschmann, M. Groschup, S. Petit, M. F. Madelaine, S. Rakatobe, A. LeDur, D. Vilette, and H. Laude. 2001. Markedly increased susceptibility to natural sheep scrapie of transgenic mice expressing ovine PrP. J. Virol. 75:5977-5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wadsworth, J. D. F., A. F. Hill, S. Joiner, G. S. Jackson, A. R. Clarke, and J. Collinge. 1999. Strain-specific prion-protein conformation determined by metal ions. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:55-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wadsworth, J. D. F., S. Joiner, A. F. Hill, T. A. Campbell, M. Desbruslais, P. J. Luthert, and J. Collinge. 2001. Tissue distribution of protease resistant prion protein in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease using a highly sensitive immunoblotting assay. Lancet 358:171-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wells, G. A. H., A. C. Scott, C. T. Johnson, R. F. Gunning, R. D. Hancock, M. Jeffrey, M. Dawson, and R. Bradley. 1987. A novel progressive spongiform encephalopathy in cattle. Vet. Rec. 121:419-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilesmith, J. W., J. B. M. Ryan, and M. J. Atkinson. 1991. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy: epidemiological studies on the origin. Vet. Rec. 128:199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilesmith, J. W., J. B. M. Ryan, and W. D. Hueston. 1992. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy: case-control studies of calf feeding practices and meat and bonemeal inclusion in proprietary concentrates. Res. Vet. Sci. 52:325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wyatt, J. M., G. R. Pearson, T. N. Smerdon, T. J. Gruffydd-Jones, G. A. H. Wells, and J. W. Wilesmith. 1991. Naturally occurring scrapie-like encephalopathy in five domestic cats. Vet. Rec. 129:233-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zanusso, G., A. Farinazzo, M. Fiorini, M. Gelati, A. Castagna, P. G. Righetti, N. Rizzuto, and S. Monaco. 2001. pH-dependent prion protein conformation in classical Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40377-40380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zanusso, G., S. Ferrari, F. Cardone, P. Zampieri, M. Gelati, M. Fiorini, A. Farinazzo, M. Gardiman, T. Cavallaro, M. Bentivoglio, P. G. Righetti, M. Pocchiari, N. Rizzuto, and S. Monaco. 2003. Detection of pathologic prion protein in the olfactory epithelium in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:711-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]