Abstract

Cohesin, along with positive regulators, establishes sister-chromatid cohesion by forming a ring to circle chromatin. The wings apart-like protein (Wapl) is a key negative regulator of cohesin and forms a complex with precocious dissociation of sisters protein 5 (Pds5) to promote cohesin release from chromatin. Here we report the crystal structure and functional characterization of human Wapl. Wapl contains a flexible, variable N-terminal region (Wapl-N) and a conserved C-terminal domain (Wapl-C) consisting of eight HEAT (Huntingtin, Elongation factor 3, A subunit, and target of rapamycin) repeats. Wapl-C folds into an elongated structure with two lobes. Structure-based mutagenesis maps the functional surface of Wapl-C to two distinct patches (I and II) on the N lobe and a localized patch (III) on the C lobe. Mutating critical patch I residues weaken Wapl binding to cohesin and diminish sister-chromatid resolution and cohesin release from mitotic chromosomes in human cells and Xenopus egg extracts. Surprisingly, patch III on the C lobe does not contribute to Wapl binding to cohesin or its known regulators. Although patch I mutations reduce Wapl binding to intact cohesin, they do not affect Wapl–Pds5 binding to the cohesin subcomplex of sister chromatid cohesion protein 1 (Scc1) and stromal antigen 2 (SA2) in vitro, which is instead mediated by Wapl-N. Thus, Wapl-N forms extensive interactions with Pds5 and Scc1–SA2. Wapl-C interacts with other cohesin subunits and possibly unknown effectors to trigger cohesin release from chromatin.

Keywords: chromosome segregation, crystallography, genomic stability, mitosis, protein–protein interaction

Proper chromosome segregation during mitosis maintains genomic stability. Errors in this process cause aneuploidy, which contributes to tumorigenesis under certain contexts (1). Timely establishment and dissolution of sister-chromatid cohesion are critical for accurate chromosome segregation and require the cell-cycle–regulated interactions between cohesin and its regulators (2–4).

In human cells, cohesin consists of four core subunits: Structural maintenance of chromosomes 1 (Smc1), Smc3, sister chromatid cohesion protein 1 (Scc1), and stromal antigen 1 or 2 (SA1/2). Smc1 and Smc3 are related ATPases, and each contains an ATPase head domain, a long coiled-coil domain, and a hinge domain that mediates Smc1–Smc3 heterodimerization. The Smc1–Smc3 heterodimer associates with the Scc1–SA1/2 heterodimer to produce the intact cohesin. Specifically, the N- and C-terminal winged helix domains (WHDs) of Scc1 connect the ATPase domains of Smc3 and Smc1, respectively, forming a ring (4).

Cohesin is loaded onto chromatin in telophase/G1, but the chromatin-bound cohesin at this stage is highly dynamic and is actively removed from chromatin by the cohesin inhibitor Wings apart-like protein (Wapl) (5–7). During DNA replication in S phase, the ATPase head domain of Smc3 is acetylated by the acetyltransferase establishment of cohesion protein 1 (Eco1) (8–13). In vertebrates, replication-coupled Smc3 acetylation enables the binding of precocious dissociation of sisters protein 5 (Pds5) and sororin to cohesin (14–17). Sororin counteracts Wapl to stabilize cohesin on replicated chromatin and establishes sister-chromatid cohesion (15). In prophase, polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) and cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) phosphorylate cohesin and sororin and trigger cohesin release from chromosome arms (15, 18–21). A pool of cohesin at centromeres is protected by the shugoshin (Sgo1)–protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) complex (22, 23), which binds to cohesin, dephosphorylates sororin, and protects cohesin from Wapl at centromeres (24). After all sister kinetochores attach properly to the mitotic spindle and are under tension, separase cleaves centromeric cohesin to initiate sister-chromatid separation. The separated chromatids are evenly partitioned into the two daughter cells through their attachment to microtubules originating from the opposite spindle poles. Wapl inactivation alleviates both the requirement for sororin in cohesion establishment in S phase and the need for Sgo1–PP2A in centromeric cohesion protection in mitosis (6, 7, 15, 24). Thus, Wapl is a critical negative regulator of cohesin.

Wapl-triggered cohesin release from chromatin requires the opening of the cohesin ring at the junction between the Smc3 ATPase domain and the N-terminal WHD of Scc1 in budding yeast, fly, and humans (25–27). Furthermore, the structure of the C-terminal domain of Wapl from the filamentous fungus Ashbya gossypii has recently been determined (28). The fungal Wapl proteins bind to the isolated Smc3 ATPase domain. It has been suggested that Wapl might trigger cohesin release from chromatin through stimulating the ATPase activity of cohesin, although this hypothesis remains to be biochemically tested.

In this study, we have determined the crystal structure of human Wapl (HsWapl). We have also systematically mapped the functional surface of Wapl using structure-based mutagenesis and performed in-depth functional and biochemical analyses of key Wapl mutants. Our results indicate that Wapl-mediated cohesin release from chromatin requires extensive physical contacts among Wapl, multiple cohesin subunits, and possibly an unknown effector. Our study reveals both similarities and important differences between the mechanisms of human and fungal Wapl proteins.

Results and Discussion

Crystal Structure of HsWapl.

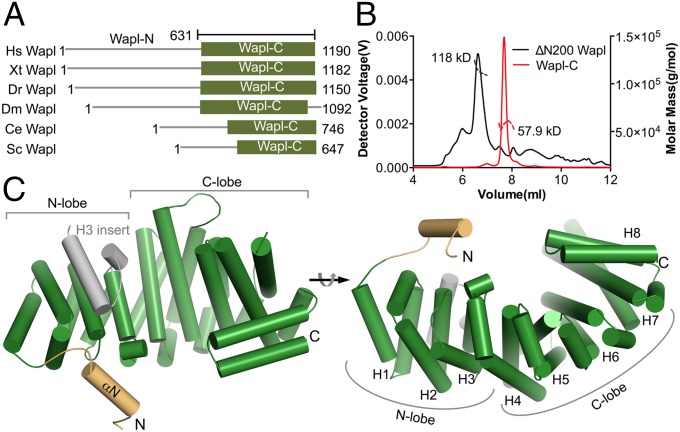

Wapl proteins from different species each have a divergent N-terminal domain with variable lengths and a conserved C-terminal domain (Wapl-C) (Fig. 1A). To gain insight into the mechanism of Wapl-dependent cohesin release from chromatin, we sought to analyze HsWapl biochemically and structurally. The recombinant, purified full-length (FL) Wapl and several N-terminal truncation mutants, including ΔN100–, ΔN200–, and ΔN300–Wapl, eluted from size-exclusion columns (SECs) with apparent molecular masses much larger than the expected molecular masses for their respective monomers. By contrast, Wapl-C behaved as a monomer on SEC with the expected molar mass. We then determined the native molecular masses of these proteins with SEC coupled with multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS). The FL Wapl had high polydispersity, indicating a tendency to aggregate. Both ΔN200–Wapl and Wapl-C (residues 631–1190) were monodispersed and had native molar masses of 118 and 58 kg/mol, similar to the molar masses of 111 and 63 kg/mol that were expected of their monomeric species (Fig. 1B). Analytical ultracentrifugation also confirmed that Wapl-C was a monomer with a native molar mass of 61 kg/mol. These results indicate that HsWapl is largely monomeric and has a globular C-terminal domain. Its N-terminal region is unfolded and flexible, explaining why the FL and larger N-terminal truncation Wapl proteins have larger than expected hydrodynamic radii and apparent molecular masses, based on SEC.

Fig. 1.

Structure of HsWapl. (A) Schematic drawing of the Wapl proteins from different species (Xt, Xenopus tropicalis; Dr, Danio rerio; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Wapl-C, the C-terminal domain of Wapl. The boundaries of human Wapl-C are indicated. (B) SEC-MALS profiles of human Wapl-C and ΔN200–Wapl. (C) Cartoon drawing of the crystal structure of human Wapl-C in two different orientations. The H3 insert and the N-terminal extension helix are colored gray and orange, respectively. The rest of the protein is colored green. The N and C lobes are labeled. The positions of the HEAT repeats 1–8 are indicated in Right. All structure figures were made with PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

We next determined the structure of Wapl-C using X-ray crystallography (Fig. 1C and Table S1). Wapl-C has an elongated shape with two lobes and contains eight HEAT (Huntingtin, Elongation factor 3, A subunit, and target of rapamycin) repeats with variable lengths and a short N-terminal extension. HEAT2 and HEAT8 each have two helixes (αA and αB) (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1). All other HEAT repeats each have two long helixes (αA and αB) and a third short helix (αC). HEAT3 contains a helical insert between αA and αB. The αA and αB helices in HEAT1–3 are shorter than those in HEAT4–8. HEAT1–3 repeats and the HEAT3 insert form the N lobe of Wapl-C. The longer HEAT4–8 repeats form the C lobe. The N-terminal extension (residues 631–640) is likely unfolded in solution, but folds into a helix in our structure due to crystal packing interactions (see Fig. 5D below).

Fig. 5.

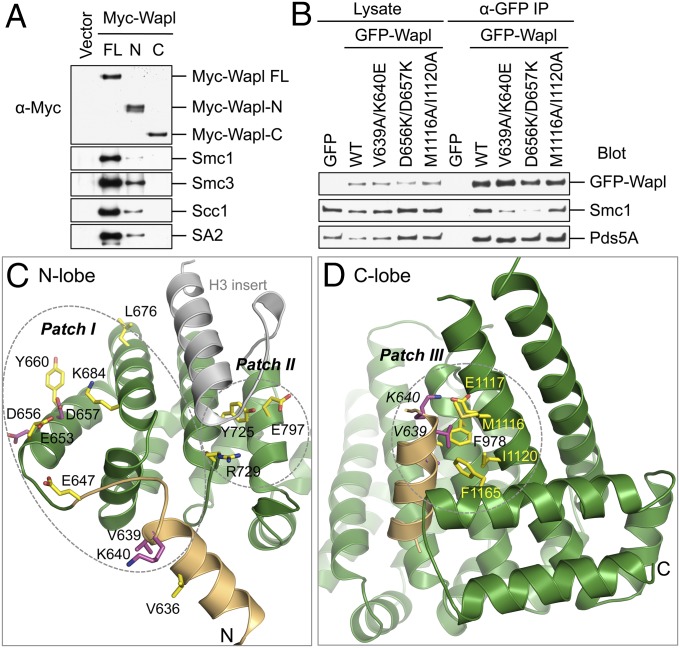

The N lobe, but not the C lobe, of Wapl-C is involved in binding to intact cohesin in human cells. (A) HeLa Tet-On cells were transfected with plasmids encoding Myc–Wapl FL, Wapl-N containing residues 1–600 (N), or Wapl-C containing residues 601–1190 (C) and then transfected with siWapl. Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc beads. The IP was blotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) HeLa Tet-On cells were transfected with the indicated GFP–Wapl plasmids for 24 h and then transfected with siWapl for 48 h. The total cell lysate and anti-GFP IP were blotted with the indicated antibodies. (C and D) Cartoon drawing of the N and C lobe of Wapl-C with the functionally important residues shown in sticks and labeled. The residues mutated in the double mutants are colored purple and others are colored yellow. The three conserved patches are circled. In crystal, the N-terminal extension helix from one Wapl molecule contacts patch III of another.

During the course of our work, the structure of the C-terminal domain of Wapl from the filamentous fungus A. gossypii was reported (28). As expected, the structures of A. gossypii Wapl (AgWapl) and HsWapl had similar folds (Fig. S2). Like HsWapl, AgWapl contains eight HEAT repeats, which form two lobes. AgWapl also contains a helical insert between helices αA and αB of HEAT3. A major difference between AgWapl and HsWapl is the relative orientation between their N and C lobes, suggesting the intriguing possibility that the connection between HEAT3 and HEAT4 is flexible, and these two repeats can rotate relative to each other.

Mapping the Functional Surface of Wapl-C.

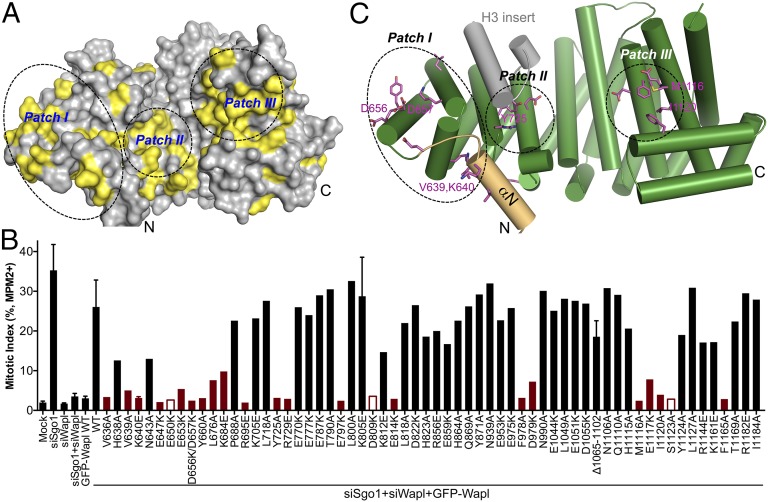

We failed to detect binding of human Wapl-C to known cohesin subunits and regulators in vitro, which prohibited us from determining the structure of Wapl-C bound to cohesin or its regulators. We thus systematically mutated Wapl-C surface residues that were conserved among metazoan Wapl proteins (Fig. 2A and Fig. S1) and examined the functions of these mutants in human cells (Fig. 2B). To test the Wapl mutants in a relatively high-throughput manner, we developed a flow cytometry assay for Wapl function. HeLa cells were first transfected with plasmids encoding GFP–Wapl WT or mutants and then transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting Sgo1 (siSgo1), siRNA oligonucleotides targeting Wapl (siWapl), or both. Cells were stained with the DNA dye propidium iodide (PI) and the MPM2 antibody (which detected mitotic phosphoproteins) and subjected to flow cytometry (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Mapping the functional surface of HsWapl. (A) Surface drawing of human Wapl-C with the conserved residues colored yellow. The N and C termini are labeled. Three conserved surface patches are circled. (B) HeLa Tet-On cells were transfected with plasmids encoding GFP–Wapl WT or mutants for 24 h and then transfected with siSgo1, siWapl, or both for another 24 h. Cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry. The mitotic index (as defined by the percentage of cells with 4N DNA contents and positive MPM2 staining) is plotted. The functionally defective mutants are shown in red. The mutants that did not express are indicated by open red bars. For samples that have been repeated multiple times, the mean and SD are shown. (C) Cartoon drawing of human Wapl-C with the functionally defective mutants shown as purple sticks. The N and C termini and key residues are labeled. The color scheme is the same as in Fig. 1C. The three conserved patches are circled.

Depletion of Sgo1 expectedly caused premature sister-chromatid separation and increased mitotic index (Fig. 2B), as defined by the percentage of cells with 4N DNA contents and positive MPM2 staining. Because the loss of centromeric cohesion in Sgo1-depleted cells was Wapl-dependent (6, 7), codepletion of Wapl rescued the mitotic arrest phenotype of Sgo1 RNAi cells. Transfection of GFP–Wapl WT or functionally intact Wapl mutants in cells depleted of both Sgo1 and Wapl restored Wapl function and again elevated the mitotic index. In contrast, transfection of functionally defective Wapl mutants did not restore the mitotic arrest in cells depleted of both Sgo1 and Wapl.

The functionally defective Wapl mutants affected residues in three surface patches on Wapl: patches I and II on the N lobe and patch III on the C lobe (Fig. 2 A and C). Patch II is not contiguous with patch I and is partially shielded by the two extra helices in HEAT3 (H3 insert). Intriguingly, mutations of the surface-conserved residues in the H3 insert, including E770K, E777K, E787K, and T790A, did not affect Wapl function in human cells (Fig. 2B). This observation raised the intriguing possibility that the H3 insert might have an autoinhibitory role. This hypothesis could not be rigorously tested, however, because a simple deletion of the entire H3 insert seriously destabilized the Wapl protein in human cells. Future structural studies on the Wapl–Pds5 or Wapl–cohesin complexes are needed to resolve this issue.

Wapl Patch I and III Mutations Diminish Cohesin Release and Sister-Chromatid Resolution During Mitosis.

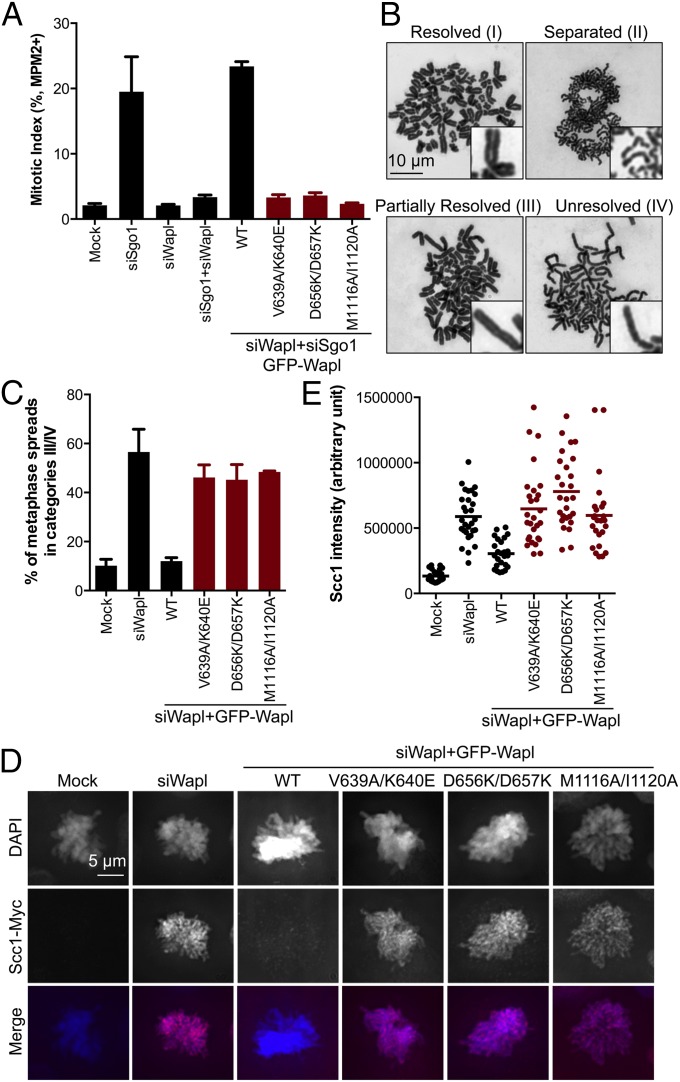

The flow cytometry assay described in Fig. 2B tested the functions of Wapl mutants indirectly. We next examined the functions of a selective subset of Wapl mutants using more direct, well-established cell biological assays, including metaphase chromosome spreads and immunofluorescence (6). Because our preliminary results indicated that certain single mutants had partial function in these assays, we constructed three double mutants: V639A/K640E, D656K/D657K, and M1116A/I1120A. The first two mutants affected residues in patch I, whereas the third targeted patch III.

As expected, all three double mutants were functionally defective in the flow cytometry-based assay and failed to restore the mitotic arrest in siSgo1/siWapl cells (Fig. 3A). These mutants were also defective in promoting sister-chromatid resolution during mitosis (Fig. 3 B and C). Most metaphase spreads of mock-transfected HeLa cells that had been arrested with nocodazole for a short duration had X-shaped chromosomes with their arms resolved (category I). Wapl depletion greatly increased the percentage of cells with partially resolved (category III) and unresolved (category IV) sister chromatids whose arms remained connected. Expression of wild-type (WT) GFP–Wapl, but not the three double mutants, rescued the defect in sister-chromatid resolution in mitotic siWapl cells, despite being expressed at similar levels (see Fig. 5B below). Consistently, all three mutants were also defective in removing Scc1–Myc-containing cohesin from mitotic chromosomes, based on immunofluorescence (Fig. 3 D and E). These results confirm the functional importance of patches I and III of Wapl-C.

Fig. 3.

Identification of functionally defective HsWapl mutants. (A) Quantification of the mitotic index of HeLa Tet-On cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs and plasmids. The functionally defective Wapl mutants are shown in red bars. The mean and SD of two independent experiments are shown. (B) HeLa Tet-On cells transfected with RNAi-resistant GFP–Wapl WT or mutants were depleted of endogenous Wapl by RNAi. Cells were synchronized with thymidine, released into fresh medium for 9 h, treated with nocodazole for 2 h, and analyzed by metaphase spreads. Sample images in four major categories of chromosome morphology are shown. In category I, most sister chromatids are X-shaped. They maintain cohesion at centromeres, but lose cohesion at arms. In category II, sister chromatids are separated and scattered. In category III, the arm regions of sister chromatids are partially resolved. In category IV, sister chromatids are not fully condensed, and their arms are not resolved. Representative sister chromatids are magnified and shown in Insets. (C) Quantification of the percentage of mitotic cells in B with categories III and IV chromosome morphology. The mean and SD of two independent experiments are shown. (D) Prometaphase HeLa Tet-On cells stably expressing Scc1–Myc that had been transfected with indicated plasmids and siRNAs were stained with DAPI (blue in merge) and anti-Myc (red in merge). (E) Quantification of the anti-Myc staining intensities of cells in D. Each dot in the graph represents a single cell (mock, n = 24; siWapl, n = 29; WT, n = 25; V639A/K640E, n = 28; D656K/D657K, n = 27; M1116A/I1120A, n = 25). The horizontal bars indicate the means.

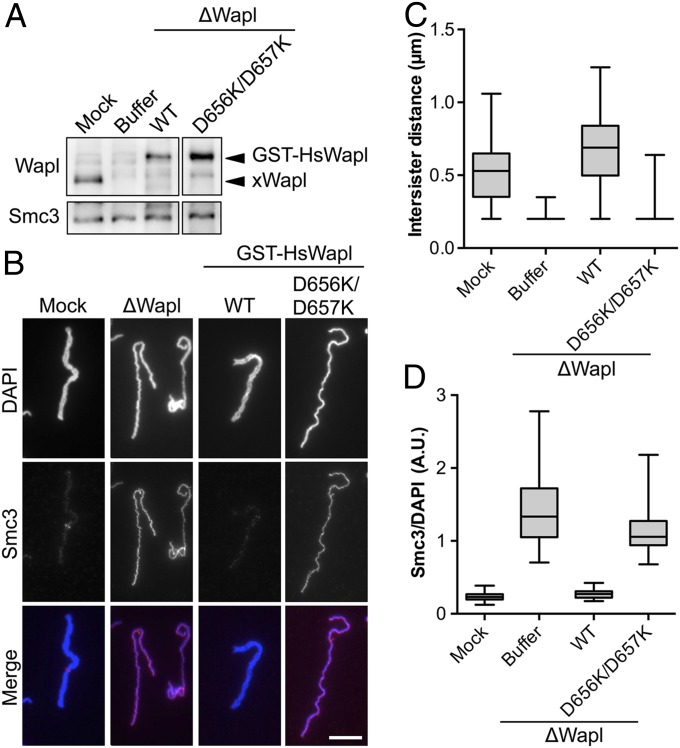

To further ascertain the functional importance of these Wapl residues, we performed depletion-rescue experiments in mitotic Xenopus egg extracts. The endogenous Xenopus Wapl (xWapl) was efficiently depleted from this cell-free system by using anti-xWapl antibody beads (Fig. 4A). Recombinant human GST–Wapl WT or D656K/D657K was added back to levels comparable to that of the endogenous xWapl. Immunodepletion of Wapl diminished sister-chromatid resolution, as evidenced by smaller intersister distances in the Wapl-depleted extract (Fig. 4 B and C). Consistent with this observation, more cohesin remained bound to chromosomes in this extract (Fig. 4 B and D). Addition of GST–HsWapl WT, but not D656K/D657K, back to the Wapl-depleted extract rescued the defects in sister-chromatid resolution and cohesin removal (Fig. 4 B–D). This result corroborates the functional importance of Wapl-C patch I residues.

Fig. 4.

Wapl D656K/D657K is defective in Xenopus egg extracts. Mitotic chromosomes were assembled in Xenopus egg extract that was either mock depleted (mock) or depleted of Wapl (∆Wapl) and supplemented with recombinant human GST–Wapl WT or the D656K/D657K mutant. (A) Immunoblot showing the relative levels of Wapl and Smc3 in each reaction. (B) Chromosomes were immunostained for Smc3 and counterstained with DAPI. Representative images are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of the intersister distance in each sample. (D) The amount of Smc3 on individual chromosomes was measured and is presented as Smc3 staining intensity normalized to DAPI staining intensity for the indicated samples (n ≥ 36 per sample). A.U., arbitrary units.

N Lobe, but Not C Lobe, of Wapl-C Is Involved in Cohesin Binding.

We next studied why the Wapl mutants were functionally defective. We first examined its binding to cohesin in human cells (Fig. 5A). Myc–Wapl-C itself did not bind cohesin. FL Myc–Wapl bound to cohesin much more efficiently than did Myc–Wapl-N. Thus, although Wapl-C is insufficient for cohesin binding, it contributes to the Wapl–cohesin interaction in the context of the FL protein.

We next tested which patches of Wapl-C were involved in cohesin binding (Fig. 5B). The GFP–Wapl V639A/K640E and D656K/D657K mutants bound cohesin less efficiently than GFP–Wapl WT did. They also bound to sororin more weakly (Fig. S4A), presumably because the Wapl–sororin interaction was bridged by cohesin and Pds5. Conversely, these two mutants bound to Pds5A as well as Wapl WT did (Fig. 5B). V639 and K640 are located in the N-terminal extension (Fig. 5C). D656 and D657 reside in the αA helix of HEAT1. All four residues are part of the conserved patch I. Therefore, the N lobe of Wapl-C contributes to cohesin binding.

In contrast, GFP–Wapl M1116A/I1120A bound to cohesin, Pds5A, and sororin as efficiently as did GFP–Wapl WT (Fig. 5B and Fig. S4A). M1116 and I1120 are located in the αB helix of HEAT7 and lie at the center of the conserved patch III. We next mutated two additional residues in this patch, D979 and E1117, which were conserved in yeast Wpl1. The D979K and E1117K mutants also retained normal binding to cohesin and sororin (Fig. S4B). Therefore, despite being critical for the function of Wapl, patch III is not required for binding to cohesin and its known regulators, such as Pds5 and sororin. Interestingly, a crystal-packing interaction involves the binding of the N-terminal extension helix of another Wapl molecule to patch III (Fig. 5D). Specifically, V639 and K640 of the N-terminal extension make energetically favorable hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions with F978, D979, M1116, E1117, I1120, and F1165.

At first glance, this binding interface appears to be functionally relevant, because mutations of residues at both sides of the interface––the N-extension helix and patch III––disrupt Wapl function. Three lines of evidence, however, argue against the functional relevance of this crystal-packing interaction. First, if the N-extension–patch III interaction were relevant, it would indicate that Wapl-C forms a symmetric dimer. Wapl-C is predominantly a monomer in solution (Fig. 1B). Second, differently tagged Wapl proteins do not appreciably interact in human cells (Fig. S5). Third, and perhaps most convincingly, although mutations of residues in both the N-extension helix and patch III disrupt Wapl function, they do so through different mechanisms. Whereas the patch III mutants are fully functional in cohesin binding, mutations of the N-extension helix weaken cohesin binding, suggesting that this helix might contact cohesin, as opposed to patch III of another Wapl molecule. Together, our results as a whole are more consistent with patch III interacting with an unknown Wapl effector. This functional surface of Wapl has contributed to artificial crystal-packing interactions. Identification of the putative Wapl effector is critical for understanding the mechanism and regulation of Wapl.

Wapl-N–Pds5 binds to Scc1–SA2.

Although Wapl-C is required for optimal binding to intact cohesin, it is insufficient to bind cohesin on its own. We next set out to map additional molecular interactions between FL Wapl and cohesin subunits in vitro. Consistent with a previous report (29), we found that GST–Wapl bound efficiently to the Scc1–SA2 heterodimer, but not to the Smc1–Smc3 heterodimer or to either Scc1 or SA2 alone (Fig. S6A). We also found that the GST–Wapl–Pds5B complex exhibited similar binding profiles. Unlike yeast Wpl1, which bound to an engineered Smc3 ATPase head domain, HsWapl or Wapl–Pds5B had no detectable binding to the isolated human Smc3 ATPase head domain.

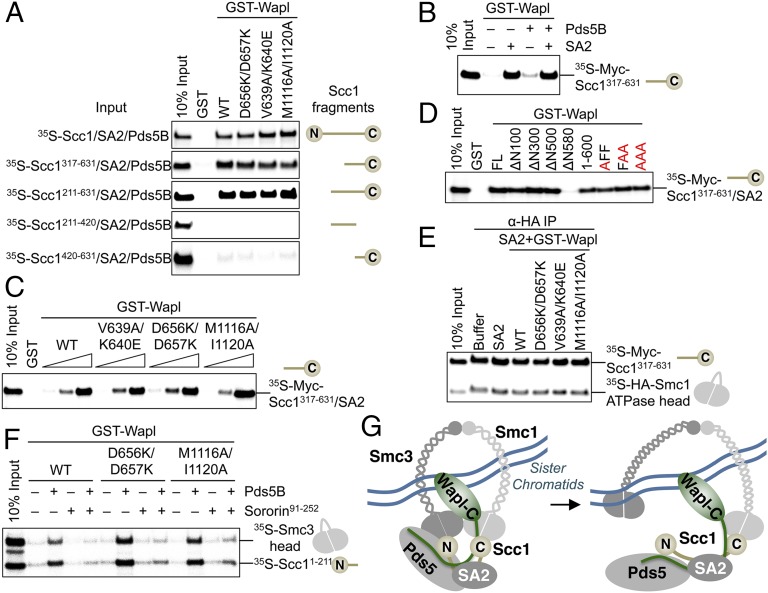

We mapped a Wapl–Pds5-binding element within Scc1–SA2 to the complex between SA2 and the C-terminal half of Scc1 (residues 317–631) (Fig. 6A). This binding required SA2, but not Pds5B (Fig. 6B). Moreover, none of the functionally defective Wapl-C double mutants exhibited deficient binding to Scc1–SA2 or SA2 bound to various Scc1 fragments in the presence or absence of Pds5B (Fig. 6 A and C and Fig. S6B). Instead, a region between residues 500–580 in Wapl-N was required for Wapl binding to Scc1317–631–SA2 (Fig. 6D and Fig. S7A). Consistent with Pds5 playing a role in Wapl binding to SA2–Scc1 (29), we detected a second interface between Pds5–Wapl and Scc1–SA2, involving Wapl-N, Pds5, and the N-terminal region of Scc1, Scc11–316 (Fig. S7B). This interaction required Pds5B, but not SA2.

Fig. 6.

HsWapl binds to cohesin through multiple interfaces. (A) GST or the indicated GST–Wapl proteins were immobilized on glutathione–agarose beads. Beads were incubated with 35S-labeled Scc1 or the indicated fragments in the presence of unlabeled, purified SA2 and Pds5B. The bound proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed with a phosphorimager. (B) Beads containing GST–Wapl were incubated with 35S-Scc1317–631 in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Pds5B or SA2. The bound proteins were analyzed with a phosphorimager. (C) Beads containing GST or increasing amounts of the indicated GST–Wapl proteins were incubated with 35S-Scc1317–631 and unlabeled SA2. The bound proteins were analyzed with a phosphorimager. (D) Beads containing GST and indicated GST–Wapl proteins were incubated with 35S-Scc1317–631 and unlabeled SA2. The bound proteins were analyzed with a phosphorimager. (E) The anti-HA beads containing 35S-Myc–Scc1317–631 and HA–Smc1 ATPase domain were incubated with unlabeled SA2 and the indicated GST–Wapl proteins. The bound proteins were analyzed with a phosphorimager. (F) Beads containing the indicated GST–Wapl proteins were incubated with 35S-Scc11–211 and 35S-Smc3 ATPase head in the presence or absence of unlabeled Pds5B or sororin. The bound proteins were analyzed with a phosphorimager. (G) Model for Wapl binding to cohesin and Wapl-dependent cohesin release from chromatin. Wapl-N binds to both Pds5 and Scc1–SA2 through two interfaces. The N lobe of Wapl-C likely contacts Smc1–Smc3 or other associated proteins. The extensive interaction between Wapl–Pds5 and cohesin does not directly disrupt the Smc3–Scc1 or Smc1–Scc1 interfaces. Wapl might open the Smc3–Scc1 gate of the cohesin ring indirectly through stimulating the ATPase activity of chromatin-bound cohesin.

Three FGF motifs in Wapl-N have been implicated in binding to Scc1–SA2 (29). Mutating the FGF motifs to EGE greatly reduced Wapl binding to Scc1–SA2. Conversely, our results showed that Wapl ΔN500, which lacked the FGF motifs, retained Scc1–SA2 binding. Furthermore, mutations of the FGF motifs to AGA only slightly diminished Wapl binding to Scc1317–631–SA2 (Fig. 6D) and did not affect the binding of Wapl–Pds5 to Scc11–316 (Fig. S7C), indicating that these motifs contribute to, but are not strictly required for, the Wapl–cohesin interaction. The EGE mutations might have introduced destabilizing interactions at the Wapl–cohesin interface, in addition to disrupting favorable interactions.

Because mutations of the N lobe of Wapl-C weakened Wapl binding to intact cohesin, but not to Scc1–SA2, the N lobe of Wapl-C likely contacts cohesin subunits or associated factors other than Scc1–SA2. Thus, Wapl has an extensive surface for binding to cohesin. Two regions of Wapl-N bind to Scc1–SA2, whereas the N lobe of Wapl-C likely contacts other cohesin subunits or cofactors. Binding of Wapl-N to the N-terminal region of Scc1 requires Pds5B, but not SA2. In contrast, binding of Wapl-N to the C-terminal region of Scc1 requires SA2, but not Pds5B.

We next tested whether Wapl directly disrupted the Smc1– or Smc3–Scc1 interfaces. The 35S-labeled, HA-tagged, engineered Smc1 ATPase head domain bound efficiently to Myc–Scc1317–631 (Fig. 6E). Addition of GST–Wapl or its mutants in the presence of SA2 did not diminish this interaction. Likewise, GST–Wapl or its mutants efficiently pulled down the complex between 35S-labeled Smc3 head domain and Scc1 N-WHD, only when Pds5B was present (Fig. 6F). This interaction was diminished by sororin, which disrupted the Wapl–Pds5B interaction. Therefore, Wapl–Pds5 does not directly compete with the ATPase head domains of Smc1 and Smc3 for their respective binding to C- and N-WHD of Scc1. The mechanism by which Wapl–Pds5 releases cohesin from chromatin remains to be established, but may involve the ATPase activity of Smc1–Smc3.

Mechanistic Differences Between Human and Yeast Wapl Proteins.

A recent study showed that budding yeast Wpl1 bound to the isolated Smc3 ATPase head domain and reported a structure of AgWapl bound to a short peptide derived from the AgSmc3 ATPase domain (Fig. S2) (28). The Smc3 peptide bound to a site on AgWapl that roughly corresponded to patch III on HsWapl. Surprisingly, mutations of the corresponding patch III residues in yeast Wpl1 disrupted Wpl1 function, but only moderately reduced the binding affinity between Wpl1 and Smc3 (28). Mutations of residues in the Wpl-binding motif of Smc3 had similarly moderate effects on the Wpl1–Smc3 affinity, but did not disrupt Wpl function. Considering our results that patch III of HsWapl does not contribute to cohesin binding and that functionally irrelevant crystal contacts tend to form at this site, the observed interactions between AgWapl and the AgSmc3 peptide need to be interpreted with caution. Alternatively, HsWapl may interact with cohesin in a mode that is different from that of the fungal Wapl proteins, because several patch III residues are not conserved between yeast and humans (Fig. S1).

Conversely, the patch I residues critical for HsWapl binding to cohesin are conserved in Wpl1 (Fig. S1). Mutations of residues equivalent to HsWapl D656 and D657 in yeast Wpl1 diminished Wpl1 binding to the Smc3 ATPase domain. Therefore, the cohesin-binding activity of the Wapl N lobe is conserved from yeast to man. Future structural studies on the complexes between Wapl and larger cohesin subcomplexes are needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms by which Wapl promotes cohesin release from chromatin and to resolve the apparent differences between human and fungal Wapl proteins.

Conclusion

Our results show that HsWapl interacts with cohesin extensively with at least three functional regions (Fig. 6G). Wapl-N–Pds5 binds to the Scc1–SA2 heterodimer, whereas the N lobe of Wapl-C likely contacts the Smc1–Smc3 heterodimer or other cohesin-associated factors. The interaction between Wapl-C N lobe and cohesin is functionally important. The Wapl-C C lobe does not contribute to the physical interaction between Wapl and cohesin and may instead interact with an unknown effector to promote cohesin release from chromatin.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression, Purification, Characterization, and Crystallization.

HsWapl proteins were expressed in bacteria and purified with a combination of affinity and conventional chromatography. Wapl-C (residues 631–1190) and its selenomethionine (SeMet) derivative were crystallized by using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method. The crystals were cryoprotected and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. See SI Materials and Methods for details.

Data Collection and Structure Determination.

Both native and SeMet-derivatized diffraction data were collected at beamline 19-ID (Structural Biology Center Collaborative Access Team) at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL) and processed with HKL3000 (30). The structure of Wapl was solved by using the diffraction data obtained from the SeMet-derivatized crystal. A partial model built with phases obtained from this dataset was refined against the native diffraction data with a resolution of 2.62 Å. After the initial round of refinement, chain A was overlapped on chain B and vice versa to add parts of the model that had been automatically built in one chain but not the other. Alternate rounds of REFMAC (31) refinement with rebuilding guided by electron density map inspection in COOT (32) led to the interpretation of ordered densities for the polypeptide chain and sulfate ions. The parameters of data collection and phasing and refinement statistics of the final model are shown in Table S1. See SI Materials and Methods for additional details of phase determination.

Protein Binding Assays.

See SI Materials and Methods for details of protein binding assays.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Synchronization.

See SI Materials and Methods for details of cell culture, transfection, and synchronization.

Antibodies, Immunoblotting, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunofluorescence.

Rabbit anti-xWapl antibody was made by immunization with recombinant protein encompassing the C-terminal 290 residues of xWapl. The anti-Smc3 antibody was generated against the C-terminal 165 residues of human Smc3. The antibodies were affinity purified. The antibody against HsWapl was described (33). The following antibodies were purchased from the indicated sources: anti-Myc (Roche; 11667203001), anti-GFP (Aves Labs; GFP-1020), anti-Pds5A (Bethyl; A300-088A), anti-Smc1 (Bethyl; A300-055A), and anti-MPM2 (Millipore; 05-368). See SI Materials and Methods for details of immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation, and immunofluorescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan-Michael Peters for providing the Wapl and Pds5A/B cDNAs. Use of Argonne National Laboratory Structural Biology Center beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by Department of Energy Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RR016478 (to S.R.), Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas Grant RP110465 (to H.Y.), and Welch Foundation Grant I-1441 (to H.Y.). S.R. is a Pew Scholar in Biomedical Sciences. H.Y. is an Investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 4K6J).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1304594110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schvartzman JM, Sotillo R, Benezra R. Mitotic chromosomal instability and cancer: Mouse modelling of the human disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(2):102–115. doi: 10.1038/nrc2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters JM, Tedeschi A, Schmitz J. The cohesin complex and its roles in chromosome biology. Genes Dev. 2008;22(22):3089–3114. doi: 10.1101/gad.1724308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onn I, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Guacci V, Unal E, Koshland DE. Sister chromatid cohesion: A simple concept with a complex reality. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:105–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasmyth K. Cohesin: A catenase with separate entry and exit gates? Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(10):1170–1177. doi: 10.1038/ncb2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vernì F, Gandhi R, Goldberg ML, Gatti M. Genetic and molecular analysis of wings apart-like (wapl), a gene controlling heterochromatin organization in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2000;154(4):1693–1710. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.4.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kueng S, et al. Wapl controls the dynamic association of cohesin with chromatin. Cell. 2006;127(5):955–967. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi R, Gillespie PJ, Hirano T. Human Wapl is a cohesin-binding protein that promotes sister-chromatid resolution in mitotic prophase. Curr Biol. 2006;16(24):2406–2417. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou F, Zou H. Two human orthologues of Eco1/Ctf7 acetyltransferases are both required for proper sister-chromatid cohesion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(8):3908–3918. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanov D, et al. Eco1 is a novel acetyltransferase that can acetylate proteins involved in cohesion. Curr Biol. 2002;12(4):323–328. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00681-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowland BD, et al. Building sister chromatid cohesion: smc3 acetylation counteracts an antiestablishment activity. Mol Cell. 2009;33(6):763–774. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J, et al. Acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 is required for S phase sister chromatid cohesion in both human and yeast. Mol Cell. 2008;31(1):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unal E, et al. A molecular determinant for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321(5888):566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.1157880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolef Ben-Shahar T, et al. Eco1-dependent cohesin acetylation during establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Science. 2008;321(5888):563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.1157774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rankin S, Ayad NG, Kirschner MW. Sororin, a substrate of the anaphase-promoting complex, is required for sister chromatid cohesion in vertebrates. Mol Cell. 2005;18(2):185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishiyama T, et al. Sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion by antagonizing Wapl. Cell. 2010;143(5):737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lafont AL, Song J, Rankin S. Sororin cooperates with the acetyltransferase Eco2 to ensure DNA replication-dependent sister chromatid cohesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(47):20364–20369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011069107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitz J, Watrin E, Lénárt P, Mechtler K, Peters JM. Sororin is required for stable binding of cohesin to chromatin and for sister chromatid cohesion in interphase. Curr Biol. 2007;17(7):630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waizenegger IC, Hauf S, Meinke A, Peters JM. Two distinct pathways remove mammalian cohesin from chromosome arms in prophase and from centromeres in anaphase. Cell. 2000;103(3):399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauf S, et al. Dissociation of cohesin from chromosome arms and loss of arm cohesion during early mitosis depends on phosphorylation of SA2. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(3):e69. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang N, Panigrahi AK, Mao Q, Pati D. Interaction of Sororin protein with polo-like kinase 1 mediates resolution of chromosomal arm cohesion. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(48):41826–41837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreier MR, Bekier ME, 2nd, Taylor WR. Regulation of sororin by Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 17):2976–2987. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitajima TS, et al. Shugoshin collaborates with protein phosphatase 2A to protect cohesin. Nature. 2006;441(7089):46–52. doi: 10.1038/nature04663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang Z, et al. PP2A is required for centromeric localization of Sgo1 and proper chromosome segregation. Dev Cell. 2006;10(5):575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Rankin S, Yu H. Phosphorylation-enabled binding of SGO1-PP2A to cohesin protects sororin and centromeric cohesion during mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(1):40–49. doi: 10.1038/ncb2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan KL, et al. Cohesin’s DNA exit gate is distinct from its entrance gate and is regulated by acetylation. Cell. 2012;150(5):961–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buheitel J, Stemmann O. Prophase pathway-dependent removal of cohesin from human chromosomes requires opening of the Smc3-Scc1 gate. EMBO J. 2013;32(5):666–676. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eichinger CS, Kurze A, Oliveira RA, Nasmyth K. Disengaging the Smc3/kleisin interface releases cohesin from Drosophila chromosomes during interphase and mitosis. EMBO J. 2013;32(5):656–665. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatterjee A, Zakian S, Hu XW, Singleton MR. Structural insights into the regulation of cohesion establishment by Wpl1. EMBO J. 2013;32(5):677–687. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shintomi K, Hirano T. Releasing cohesin from chromosome arms in early mitosis: Opposing actions of Wapl-Pds5 and Sgo1. Genes Dev. 2009;23(18):2224–2236. doi: 10.1101/gad.1844309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minor W, Cymborowski M, Otwinowski Z, Chruszcz M. HKL-3000: The integration of data reduction and structure solution—from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(Pt 8):859–866. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906019949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(Pt 3):240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu N, et al. Scc1 sumoylation by Mms21 promotes sister chromatid recombination through counteracting Wapl. Genes Dev. 2012;26(13):1473–1485. doi: 10.1101/gad.193615.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.