Abstract

Binding of the transcription factor PU.1 to its DNA binding motif regulates the expression of a number of B-cell- and myeloid-specific genes. The long terminal repeat (LTR) of macrophage-tropic strains of equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) contains three PU.1 binding sites, namely an invariant promoter-proximal site as well as two upstream sites. We have previously shown that these sites are important for EIAV LTR activity in primary macrophages (W. Maury, J. Virol. 68:6270-6279, 1994). Since the sequences present in these three binding motifs are not identical, we sought to determine the role of these three sites in EIAV LTR activity. While DNase I footprinting studies indicated that all three sites within the enhancer were bound by recombinant PU.1, reporter gene assays demonstrated that the middle motif was most important for basal levels of LTR activity in macrophages and that the 5′ motif had little impact. The impact of the 3′ site became evident in Tat transactivation studies, in which the loss of the site reduced Tat-transactivated expression 40-fold. In contrast, elimination of the 5′ site had no effect on Tat-mediated activity. Binding studies were performed to determine whether differences in PU.1 binding affinity for the three sites correlated with the relative impact of each site on LTR transcription. While small differences were observed in the binding affinities of the three sites, with the promoter-proximal site having the strongest binding affinity, these differences could not account for the dramatic differences observed in the transcriptional effects. Instead, the promoter-proximal position of the 3′ motif appeared to be critical for its transcriptional impact and suggested that the PU.1 sites may serve different roles depending upon the location of the sites within the enhancer. Infectivity studies demonstrated that an LTR containing an enhancer composed of the three PU.1 sites was not sufficient to drive viral replication in macrophages. These findings indicate that while the promoter-proximal PU.1 site is the most critical site for EIAV LTR activity in the presence of Tat, other elements within the enhancer are needed for EIAV replication in macrophages.

Equine infectious anemia (EIA) results from a persistent infection in horses by the lentivirus equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV). In contrast to other lentiviruses, EIAV does not cause a long-term, debilitating disease but instead results in an acute, fulminate one. Within a few weeks of the initial infection, viremia is usually detected at high levels and is accompanied by fever and thrombocytopenia (6, 9, 41). After an initial episode of viremia that can last several days to weeks, the viremia is controlled and can become undetectable. Subsequent episodes of viremia may, but do not always, recur. However, the virus persists and the infected horse remains seropositive for life. EIAV pathogenesis is believed to result primarily, if not solely, from virus infection of tissue macrophages (32, 41). Tissue macrophages are also believed to be the primary reservoir of the virus during persistence (32).

As a consequence of the critical role that macrophages play in the EIAV life cycle, the transcription factor binding motifs that drive long terminal repeat (LTR) expression in macrophages have previously been identified (4, 5, 27). Three ets binding motifs that interact with the macrophage- and B-cell specific transcription factor PU.1 are present within the LTR enhancer of all known virulent strains of EIAV (29) and are necessary for viral transcription in primary macrophages (27). As further evidence that the EIAV PU.1 sites regulate viral expression in a macrophage-specific manner, it was previously demonstrated that substitution of the EIAV enhancer for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enhancer restricts HIV replication to macrophages (38). The enhancer region of the EIAV LTR, however, is surprisingly genetically hypervariable, and all three PU.1 sites are not necessarily found within the enhancer of long-term, healthy equine carriers or tissue-culture-adapted strains of the virus (29).

PU.1 binding motifs are found in and are critical for the expression of virtually all genes that are involved in myeloid-monocyte differentiation and development (45). In general, PU.1-dependent myeloid-specific promoters contain a single PU.1 site located close to the transcription initiation site. Transcription of these genes is usually not directed by a TATA box. Instead, PU.1 has been proposed to serve as a promoter-proximal motif that recruits other transcription factors, such as C/EBPα and AML-1, to the enhancer as well as the basal transcriptional machinery to the promoter (15, 46). In contrast to cellular PU.1-dependent enhancers, multiple PU.1 sites are present within the EIAV LTR in conjunction with an invariant TATA box. While it is known that the PU.1 sites are necessary for EIAV LTR expression in primary macrophages (27), whether the PU.1 sites are sufficient for driving LTR expression and virus replication in macrophages is not clear. Previous electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using overlapping oligonucleotides spanning the EIAV enhancer detected binding of PU.1 to all three ets sites (27). While other sites (PEA-2 and CRE) present in the EIAV enhancer from macrophage-tropic viruses bind to nuclear extracts (NEs) from fibroblastic cell lines that support EIAV replication (28), these sites do not appear to interact with primary macrophage NEs. These findings suggest that the PU.1 sites may be sufficient for LTR expression in primary macrophages.

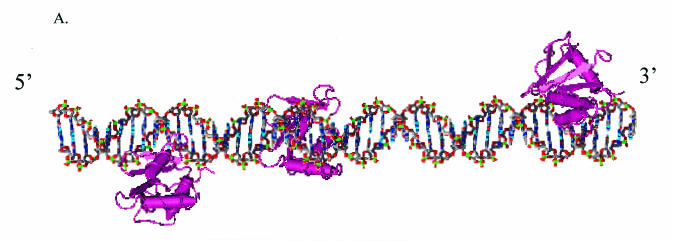

Since the crystal structure of the PU.1 binding domain with its DNA binding motif is known (24), we were able to model the interaction of PU.1 with the three EIAV sites. The second helix of the PU.1 binding domain is inserted into the major groove of the DNA helix and interacts with the core GGAA motif. The three core PU.1 motifs have a 13- and 23-nucleotide space between the 5′ and middle and the middle and 3′ sites, respectively. Assuming that this region of the LTR is B DNA and that all three sites can be occupied simultaneously, the spacing would result in PU.1 bound to its motif on multiple faces of the DNA (Fig. 1A). Since a 42-kDa globular protein such as PU.1 would have a Stokes radius of approximately 57 Å, each PU.1 molecule bound to the DNA would occupy about one complete turn of DNA. Because of the positioning of the motifs to each other, it is possible that PU.1 binds to each site independently of the other sites. Alternatively, because of the relatively close spacing of the sites, there may be interactions between the bound proteins. A third scenario that is possible is that the spacing between the sites is not sufficient to allow all three sites to be occupied simultaneously. To examine the interactions between PU.1 and the binding sites present within an EIAV LTR in order to define the role of this transcription factor in EIAV replication, we investigated the physical interaction of PU.1 with its EIAV motifs and explored the functional implications of these interactions. All three sites were found to be bound in a DNase protection assay, and no evidence of cooperative interactions was found. The middle and promoter-proximal PU.1 motifs were demonstrated to be important for basal transcription studies; however, the promoter-proximal site had the most pronounced effect on EIAV Tat transactivation of the LTR. Binding of this macrophage-specific transcription factor to the promoter-proximal site is reminiscent of findings with the promoter-proximal Sp1 site in HIV and suggests that PU.1 may serve a similar function as Sp1 in the EIAV LTR in macrophages. Despite the relatively robust reporter gene activity in a macrophage cell line of an enhancer region containing three PU.1 sites, virus infectivity studies demonstrated that these three sites were not sufficient for EIAV replication. Our findings indicate that other enhancer motifs are required for virus replication, suggesting that the interaction between EIAV enhancer elements needed for viral infectivity may be more complex and extensive than those identified through reporter gene assays.

FIG. 1.

PU.1 interactions with EIAV ets motifs. (A) Model of the interaction of the PU.1 binding domain with the three EIAV binding motifs. The binding domain of PU.1, as determined by Kodandapani et al. (24), was modeled onto B-form DNA. The second helix of a helix-turn-helix motif of PU.1 binds in the major groove of the helix through interactions with the core ets motif (GGAA) that is present on the antisense strand of the EIAV enhancer. (B) Schematic of the EIAV LTR and the nucleotide sequences of the EIAV LTR enhancer ets or PU.1 sites. The Oct motif is identified below the construct because the site physically overlaps both the 5′ and middle PU.1 sites. The empty blocks within the enhancer represent 3- to 5-bp blocks of DNA that are not believed to be involved with transcription factor binding. (C) DNase I protection of the EIAV enhancer region complexed with recombinant PU.1 protein. Lanes 1 to 3, increasing concentrations of DNase I in the absence of PU.1; lane 4, probe that was not treated with DNase; lanes 5 to 7, increasing concentrations of DNase I in the presence of recombinant PU.1. The 5′ to 3′ EIAV LTR enhancer nucleotide sequence is shown in the center of the figure. Hypersensitive regions (circles) as well as PU.1-protected nucleotides (bars) at each of the three PU.1 motifs are indicated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

DH82 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus 15% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37°C and split 1:5 with trypsin-versene two to three times per week. 293 cells (ATCC CRL-1573) are an adherent human embryonic kidney cell line transformed with adenovirus type 5 DNA (17). 293 cells were maintained in DMEM plus 10% FCS at 37°C and split 1:10 with trypsin-versene two or three times per week. Primary equine macrophages were isolated by a density centrifugation method based on techniques developed by English and Andersen (12). Five hundred milliliters of horse blood was centrifuged for 15 min at 700 × g. The cells were diluted to 120 ml with Hanks balanced salt solution + 2% FCS + penicillin-streptomycin (P/S). Thirty milliliters of diluted cells was layered onto a gradient of Histopaque-1119 and Histopaque-1077 (Sigma) and centrifuged for an additional 15 min at 700 × g. The white layer of cells located between the medium and the Histopaque layers was collected and washed three times with Hanks balanced salt solution + 2% FC + P/S. Mononuclear cells were plated into either 6-well trays at 7.0 × 107 cells per well or 24-well trays at 2.0 × 107 cells per well and were incubated at 37°C overnight in DMEM plus 20% normal horse serum plus 10% FCS. The following day, nonadherent cells were removed by rinsing of the plated cells with warm Hanks balanced salt solution + 2% FCS + P/S.

Transfections and reporter gene assays.

DH82 cells (2.8 × 105) were plated in a 6-well tray with DMEM plus 10% FCS and allowed to grow overnight. DH82 cells were transfected the following day with 3 μg of an LTR-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) construct in combination with 200 ng of a cytomegalovirus enhancer-promoter-driven β-galactosidase (β-Gal) plasmid (pCMV/β gal) by use of the GenePORTER transfection reagent (GTS, San Diego, Calif.). All transfections containing the LTR/CAT reporter plasmid were performed in the presence and absence of 1 μg of an EIAV Tat expression plasmid, pRSV-Etat, as noted (11). In wells to which pRSV-Etat was not added, 1 μg of salmon sperm DNA was added to maintain equivalent concentrations of DNA in all transfections. Transfections using GenePORTER were carried out in a total volume of 1 ml of serum-free DMEM per well according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were harvested and assayed for β-Gal to normalize cell lysates. CAT activity was determined for the transfection-normalized cell lysates. Transfections were all done in duplicate and were repeated three times.

β-Gal assays were performed with the Promega (Madison, Wis.) β-Gal enzyme assay system according to the manufacturer's instructions. For CAT assays, cell lysates were incubated with [14C]chloramphenicol and acetyl coenzyme A as described by Gorman et al. (16). Acetylated and unacetylated [14C]chloramphenicol was separated by thin-layer chromatography on Kodak thin-layer sheets. The acetylation pattern was identified and quantified with a Packard Instruments Instant Imager. The amount of CAT activity was expressed as the percentage of acetylation per milliunit of β-Gal per hour. The fold activation in the presence of Tat was determined by dividing the rate of acetylation in the presence of Tat by the rate of acetylation in the absence of Tat.

Expression and purification of PU.1.

Escherichia coli transformed with the PU.1-expressing pET (PU.1/pET) vector plasmid (37) was inoculated into a 500-ml culture and grown to an A600 of 0.700. IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM to induce PU.1 expression. Cells were grown for 7 h and then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min. Twenty-five milliliters of buffer A (6 M guanidinium HCl, 50 mM Tris, 50 mM Na phosphate [pH 8.0]) was added to lyse the cells. PU.1 protein was bound to the resin by incubation of the bacterial lysate with 8 ml of buffer A-equilibrated Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin (Stratagene) in a 50-ml tube on a rotary shaker at 25°C for 45 min. The resin was washed once with buffer A, pH 8.0, and twice with buffer A, pH 6.0, and finally was eluted in buffer A, pH 5.0. To prevent the eluted protein from precipitating during dialysis, we diluted it slowly in buffer D (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 80 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 15% glycerol, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μM leupeptin) to approximately five times its starting volume. After its dilution, the protein was dialyzed in buffer D overnight, with three buffer changes. Recombinant PU.1 was highly purified by this approach, and by visualization on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel and Coomassie blue staining the 42-kDa band represented >95% of the total protein in the lane (data not shown). Binding of recombinant PU.1 to its cognate site was verified by EMSAs, and it was used in DNase protection assays, affinity assays, and competition experiments.

End labeling of DNA probe for DNase I protection assay.

For end labeling of a DNA probe for use in a DNase I protection assay, the wild-type tissue-culture-adapted LTR, MA.1, which contains an NheI site at the 5′ end of the enhancer region, was first digested with the restriction enzyme MfeI to cut the LTR at the U3-R border. The DNA was radiolabeled with Klenow, [32P]dATP, [32P]TTP, dCTP, and dGTP for 30 min at room temperature. At the end of the incubation, unincorporated nucleotides were removed by using a G-50 exclusion column, and the reaction mixture was heat inactivated for 20 min at 75°C. This was digested with the restriction enzyme NheI and electrophoresed in a 2.2% agarose gel. The 120-nucleotide band corresponding to the EIAV enhancer-promoter region was excised, gel purified, phenol-chloroform extracted, and ethanol precipitated.

PU.1-DNA interaction studies. (i) DNase I protection assay.

The end-labeled probe (20,000 cpm) was incubated with approximately 80 ng of purified recombinant bacterially synthesized PU.1 for 30 min. Incubation was done in a total reaction volume of 20 μl containing 4 μg of poly(dI-dC), 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM MgCl2. Appropriate concentrations of DNase I stock solution (1 mg/ml; 100 mM CaCl2) were added for 1 min at room temperature. Two hundred microliters of a stop solution consisting of 0.6 M ammonium acetate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.1 mM EDTA was added subsequent to the DNase I treatment. Samples were phenol-chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated. The pellet was resuspended in loading buffer, heated to 90°C for 2 min, and run in a 10% sequencing gel containing 35% urea. The DNase I protection pattern was visualized by autoradiography. A G-reaction was carried out by incubating 200,000 cpm of end-labeled probe in a 200-μl reaction volume containing 50 mM cacodylate, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 μl of dimethylsulfate (DMS) at 20°C for 10 min. To stop the reaction, the above mixture was added to a solution containing 50 μl of sodium acetate (pH 7.0), 1 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 100 μg of tRNA/ml, and 750 μl of 100% ethanol was added to precipitate the DNA. The pellet was dried, resuspended in 10 μl of piperidine, and heated to 90°C for 30 min. This sample was dried to completion, and 10 μl of H2O was added and dried to completion. Finally, the sample was resuspended in 200 μl of loading buffer.

(ii) Scatchard analysis.

Three double-stranded oligonucleotides, each containing a PU.1 binding site corresponding to one of the PU.1 binding motifs in the EIAV LTR, were made by annealing complementary synthetic oligonucleotides. These where labeled with [32P]TTP in the presence of the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase and unlabeled dATP, dGTP, and dCTP. Increasing amounts (2 to 10 μl) of these oligonucleotides (∼10,000 cpm/μl) were incubated with 4 μl of bacterially synthesized PU.1 in a total volume of 20 μl containing 4 μg of poly(dI-dC), 100 mM KCl, and 1 mM MgCl2 for 20 to 25 min and were then placed on ice for 10 min. Samples were run in a 5% polyacrylamide gel (80:1 acrylamide to bis ratio) at 4°C at 150 V. For quantification purposes, 0.64 pmol of labeled, unpurified oligonucleotide was loaded in a separate lane. The bound and unbound complexes were quantified with a Packard Instant Imager, and Scatchard plots were graphed with Equilibrate software.

(iii) Binding studies with oligonucleotides containing two sites.

NEs were generated from DH82 cells, as previously described (21), by a modified version of a protocol described by Dignam et al. (10). The NEs contained 6.4 μg of protein/μl. Oligonucleotide probes were labeled by filling in of the 3′ ends with [32P]TTP and cold nucleotides by use of the Klenow fragment. A count of 20,000 cpm was used in each lane, and increasing quantities of NE were added in the presence of 4 μg of poly(dI-dC), 80 mM KCl, and 1 mM MgCl2. Gels were dried, and the amount of shifted versus unshifted label was quantitated with an Instant Imager (Packard Instruments). All curves reached saturation. Titration data were normalized to 100% binding and were fit by nonlinear least-squares (23) to a model-independent two-site (Adair) function (equation 1) that allows the sites to be heterogeneous (i.e., nonidentical) and cooperative (42, 43).

|

(1) |

Because the exact concentration of PU.1 in the NE was not known, the x axis for these titrations was reported as the volume added. To apply a standard binding function, it was necessary to treat concentrations as having units of 1 for a 1-μl addition. For each trial, the relative binding to the sites (Kd) was calculated from the resolved association constant of binding to both sites (K2), by which Kd is equal to the square root of the reciprocal of K2. The resolved values of Kd were then related back to the volume of NE added, and values for the effective volume required for 50% saturation were reported for each titration. Average curves were generated for two independent trials of the 5′ plus middle PU.1 oligonucleotide and three independent trials of the middle plus 3′ PU.1 oligonucleotide.

(iv) Mutagenesis of EIAV LTR.

Mutagenesis was initiated by the insertion of an NheI site at the 5′ end of the enhancer region at position −122 relative to the start of transcription. For PCR amplification, primers NheI (5′ GGC TAG CTC ATA CGA GTC TGC AAC 3′) and Xba 323 C′ (5′ TCT AGA GTA GGA TCT CGA ACA 3′) amplified 240 bp which encompassed the 3′ 2/3 of the LTR. The template for this PCR was the tissue-culture-adapted EIAV LTR MA.1. A separate amplification was also done from position −122 upstream to the 5′ end of the LTR with primers NheI C′ (5′ AGC TAG CCC TTT GGG 3′) and Xho 7606 (5′ GGT TTT CTC GAG GGG TTT TAT AAA TG 3′). These PCR-amplified fragments were cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) and PCR II (Invitrogen), respectively. Each plasmid was digested with NheI and XbaI, gel purified, and ligated into the PCR II backbone. The resulting LTR (LTR XNMX) contained XhoI and XbaI restriction sites flanking the LTR, with NheI and MfeI sites surrounding the enhancer region.

Point mutations were made in the other transcription factor binding sites, for MDBP, PEA-2, Oct, Lvb, and CRE, that existed within the LTR. The template OAS21, which contained a mutation in the Oct site as well as a substitution of a SpeI site for the CRE motif that eliminated ATF-1 binding to the CRE motif, was amplified with the primers pNhexx (5′ AGG GCT AGC TCA TAC TAG TCT GCA ACT AAG TGC AAT ATC 3′) and Mun I C′ (5′ AGT GCC CAA TTG TCA G 3′). The primer pNhexx incorporated point mutations into the MDBP and PEA-2 sites, blocking the ability of transcription factors to bind their respective cognate sequences. The product of this last amplification was used as a template for another PCR with the primers NheAvr2 (5′ GCT AGC TCA TAC GAG TCT GCA CCT AGG C 3′) and Mun I C′. Amplification with the NheAvr2 primer resulted in the replacement of the PEA-1 transcription factor binding motif with an AvrII restriction site. As was seen by sequencing of one of the clones that resulted from this PCR, a single nucleotide substitution in the Lvb site eliminated this site from the LTR. By cloning of this product into the LTR XNMX backbone at the NheI and MfeI restriction sites, the resulting full-length LTR (3PU.1) contained the three PU.1 motifs as the only transcription factor binding sites.

Various primers were synthesized to create point mutations in all possible combinations of the PU.1 sites. XS1speC′ (5′ ACT AGT CAC AAA TGC GGA ACT ATA TTG ATT CAC TAC AGG 3′) was used in combination with the primer Xho 7606 to mutate the 5′ PU.1 site from GTTCC to GTGAA. The primer XS2speC′ (5′ ACT AGT CAC AAA TGC TTC ACT ATA TTG) was used in combination with the primer Xho 7606 to create the same point mutation in the middle PU.1 site. The primer XS12speC′ (5′ ACT AGT CAC AAA TGC TTC ACT ATA TTG AAT CAC TAC AGG 3′) was also used in combination with the Xho 7606 primer in order to create the same point mutations in both the upstream and middle PU.1 binding sites. The 3ES primer (5′ TAA CAC TAG TTA AGT GAA TGT TTT TA 3′) was used with the Xba 323 C′ primer to make the above point mutation in the 3′ PU.1 binding site. The primer p3′PU.1up C′ (5′ AAC TAG TCA CAA AAC AGG AAC TAT AAA CAG GAA CTA 3′) was used in conjunction with the primer Xho 7606 to generate an LTR that contained the 3′ PU.1 sequence at both the 5′ and middle PU.1 locations. These amplified products were cloned into the 3PU.1 vector in various combinations and finally into pCATBasic to create the LTR/CAT constructs pDel-5′, pDel-mid, pDel-5′,mid, pDel-mid,3′, pDel-5′,3′, pDel-3′, pNoPU.1, and p3′UP. The LTR construct named p11 PU.1 contains 11 PU.1 sites and was generated by a multimerization that occurred upon ligation of an insert into the enhancer region after digestion with the restriction enzymes NheI and SpeI, which have homologous 5′ overhanging ends of the sequence CTAG.

HIV/EIAV chimeric LTRs were generated by the insertion of an NheI restriction site that was introduced into the EIAV LTR at position −120 relative to the start of transcription. This site, along with the naturally occurring MfeI site at position −5, was used to alter the enhancer region. A 115-bp piece of DNA that encompassed the enhancer region was excised from the EIAV LTR, and a 118-bp PCR-amplified piece of DNA containing the HIV enhancer-promoter region was inserted to produce pEp4/CAT. An additional mutant, pEp4mTAR/CAT, was created by a single point mutation (in bold in the primer sequence) in the TAR region of pEp4/CAT by PCR mutagenesis with a sense primer, mut TAR (GACAATTGGGCACTCAGATTCTCCGGTCTGAGTCC), and an antisense primer, Xba 323C′ (TCTAGAGTAGGATCTCGAACA).

(v) PCR.

DNA PCRs were performed with 100 to 200 ng of plasmid DNA. The reaction tubes also contained 1× thermophilic buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 0.1% Triton X-100), 2.5 μM MgCl2, a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, a 200 nM concentration of each primer, and 0.5 μl of Taq polymerase (Promega). PCR amplifications consisted of 29 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by a 5-min extension at 72°C.

RESULTS

Evidence of PU.1 binding to all three ets sites in the EIAV enhancer.

Previous work indicated that the three EIAV enhancer ets sites that interact with PU.1 in macrophage NEs are important for macrophage-specific expression of the EIAV LTR (27). Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that substitution of an EIAV enhancer that contains all three PU.1 sites confers macrophage specificity to HIV-1 expression (38). The presence of three closely spaced PU.1 sites within an enhancer is unique to EIAV, and the roles of these motifs in LTR activity and virus expression have not been extensively explored. The three PU.1 binding motifs in the EIAV enhancer region consist of an invariant core sequence, TTCC, but each contains variable nucleotides both upstream and downstream from the core motif that influence binding (26, 27). Despite the sequence heterogeneity of the three EIAV PU.1 sites (Fig. 1B), EMSAs have demonstrated that the macrophage- and B-cell-specific transcription factor PU.1 interacts with each EIAV motif in the context of a small synthetic oligonucleotide (5). We investigated whether recruitment and binding of the protein to all three sites within the context of a wild-type EIAV enhancer were possible. DNase I protection assays were performed, using bacterially synthesized PU.1 and a 120-bp fragment that encompassed the enhancer-promoter regions of the EIAV LTR (Fig. 1C). With a wild-type EIAV LTR enhancer that contained three PU.1 motifs as well as MDBP, PEA-2, Lvb, Oct, and CRE sites, sequences corresponding to the TTCC core nucleotides of all three PU.1 sites were strongly protected from DNase I treatment in the presence of recombinant PU.1. As observed with PU.1 binding sites of some cellular genes, nucleotides immediately upstream and six to eight nucleotides downstream from the core motif were also protected from digestion (13, 18, 40). A strong DNase-hypersensitive band was observed between the core TTCC sequence and the protected downstream nucleotides. The presence of the intense band immediately following the protected nucleotides suggests a conformational change or bend in the DNA that makes that nucleotide more accessible to DNase I, which is consistent with previous studies of other PU.1 binding sites (18, 40, 44). Results from the DNase I protection assays indicated that all three PU.1 sites were bound in the context of the wild-type enhancer.

The 3′ PU.1 motif is the most critical for LTR activity.

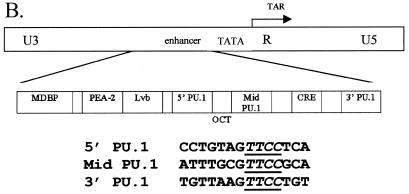

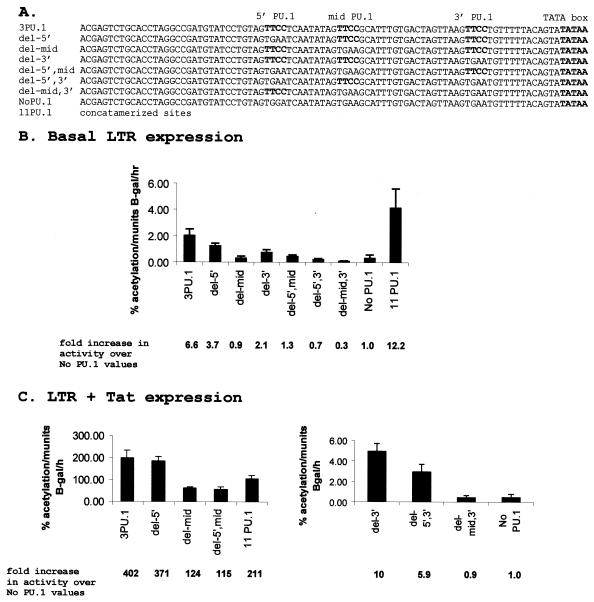

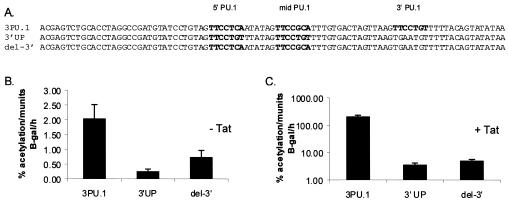

We were next interested in determining if all three sites were equally important for LTR activity. For determination of the relative contribution of each of the PU.1 sites to LTR activity, reporter gene assays were performed with the macrophage cell line DH82, which supports EIAV replication (21). Since we were interested in exploring the direct effects of PU.1 on the LTR, other known transcription factor binding motifs were mutated to eliminate possible synergistic interactions between proteins bound to those sites and PU.1 bound to its cognate motifs. Therefore, LTR/CAT constructs were generated that contained only the three PU.1 sites. The PU.1 sites were then mutated singly or in pairs, creating all permutations of one to three PU.1 sites (Fig. 2A). These LTRs were analyzed for non-Tat-transactivated (basal) and Tat-transactivated levels of expression. Basal expression levels were low. The construct containing a single PU.1 site at the 5′ location (pDel-mid,3′) had the lowest activity level, while the construct containing multiple copies of the enhancer region with 11 PU.1 sites (p11 PU.1) had the highest basal values (Fig. 2B). The loss of a single PU.1 site resulted in the reduction of basal expression by 40 to 85%, with elimination of the middle PU.1 site (pDel-mid) having the most pronounced effect.

FIG. 2.

PU.1 binding motifs in the EIAV enhancer differentially impact LTR activity in the canine macrophage cell line DH82. (A) Enhancer sequences tested for activity within the context of LTR/CAT constructs. (B) Basal levels of LTR activity. (C) Tat-transactivated levels of LTR activity of constructs containing the promoter-proximal (3′) PU.1 binding site (left panel) and constructs that do not contain the promoter-proximal (3′) PU.1 binding site (right panel).

In the presence of Tat, expression of the LTRs fell into two groups, namely high expressers (Fig. 2C, left panel) and low expressers (Fig. 2C, right panel). All of the high-expresser constructs contained the promoter-proximal PU.1 site, whereas this site was missing from all of the low expressers. This finding highlighted the importance of the 3′ site for Tat-transactivated activity of the LTR in DH82 cells. The loss of the 5′ site had little to no effect on the levels of LTR activity in the presence of Tat; the levels of LTR activity for p3PU.1 and pDel-5′ were not significantly different from each other (P = 0.312). Consistent with this finding, the LTR construct containing a mutation in the middle PU.1 site (pDel-mid) had an activity level that was not different from that of the LTR construct containing mutations in both upstream sites (pDel-5′,mid) (P = 0.39). These constructs had activities that were approximately 50% of the activity of p3PU.1, suggesting that the middle site plays a more important role in Tat-mediated LTR activity than the 5′ site. In the presence of Tat, the 11 PU.1 construct had lower transcriptional activity than both the p3PU.1 and pDel-5′ constructs, despite higher basal levels of expression.

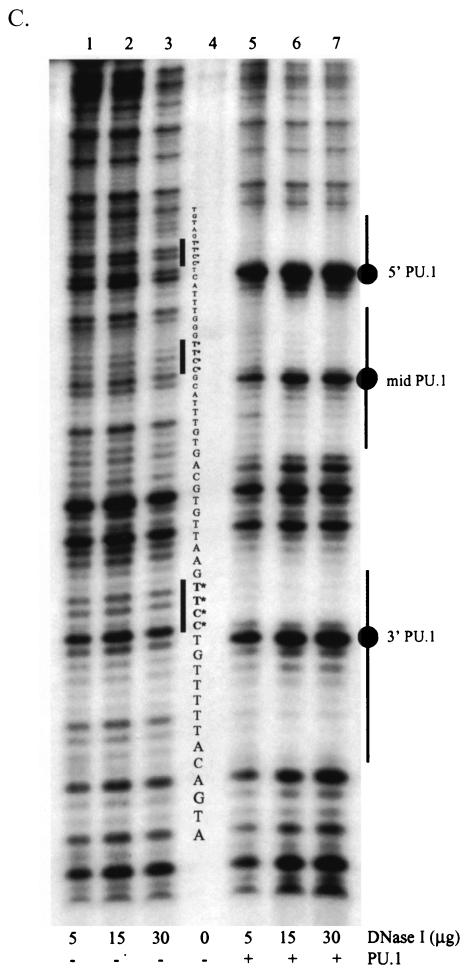

Affinity of PU.1 for EIAV LTR ets motifs.

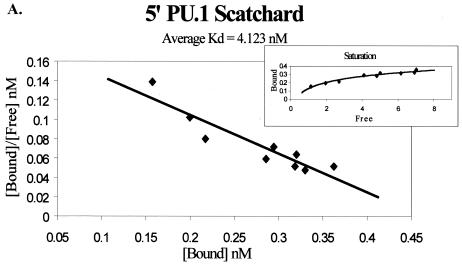

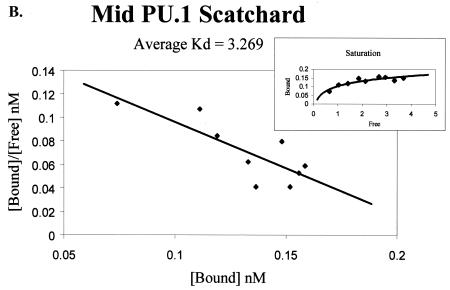

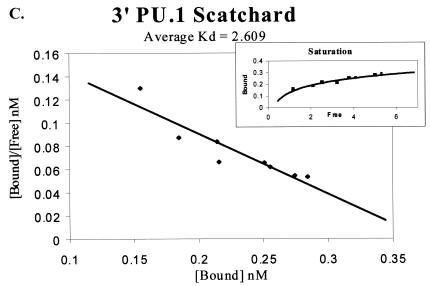

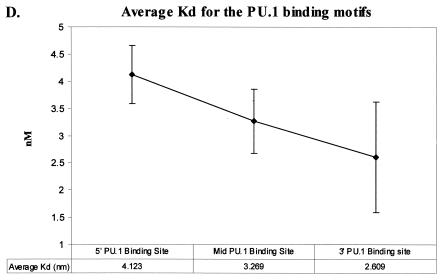

The effect of the 3′ PU.1 site could be due to its location within the enhancer or to an enhanced affinity of the site for PU.1 compared to the affinity of PU.1 for the other sites. To determine if PU.1 affinity for the promoter-proximal PU.1 motif differed from the affinity for the other two PU.1 sites, we undertook an investigation of PU.1 binding to each of the three sites. Double-stranded oligonucleotides were synthesized that matched the sequence of each motif (Table 1). Binding studies were performed and analyzed by Scatchard analysis. Increasing concentrations of each 32P-labeled, double-stranded oligonucleotide were incubated with the recombinant PU.1 protein and run through a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. Bound and unbound probes were quantified and graphed by using a Scatchard plot, and a Kd was determined. Figure 3A to C present representative data from the Scatchard analysis for each site. The 5′ PU.1 binding site had an average Kd of 4.12 ± 0.54 nM, the middle PU.1 binding site had an average Kd of 3.27 ± 0.59 nM, and the 3′ PU.1 binding site was determined to have an average Kd of 2.61 ± 1.0 nM. The decreasing trend in disassociation constants observed from the 5′ PU.1 binding site to the 3′ PU.1 binding site suggested that the 3′ site had the strongest affinity for PU.1. However, the binding affinities were not statistically different (Fig. 3D). A parallel series of experiments were performed to investigate the ability of increasing concentrations of cold competitor oligonucleotide to compete for PU.1 binding to 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing one of the three EIAV PU.1 sites (data not shown). Consistent with the Scatchard analysis, competitor oligonucleotides containing the middle and 3′ PU.1 sites were able to compete for binding at lower concentrations than the 5′ site oligonucleotide, but these differences were also not statistically significant.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for PU.1 binding studiesa

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| 5′PU.1 | ATA CTG TAG TTC CTC AAT ATA G |

| 5′PU.1 C′ | TTC ACT ATA TTG AGG AAC TAC A |

| MidPU.1 | TCA ATA TAG TTC CGC ATT TGT G |

| MidPU.1 C′ | ACG TCA CAA ATG CGG AAC TAT A |

| 3′PU.1 | CGT GTT AAG TTC CTG TTT TTA C |

| 3′PU.1 C′ | TAC TGT AAA AAC AGG AAC TTA A |

| 5′ + mid PU.1 | TCC TGT AGT TCC TCA ATA TAG TTC CGC A |

| 5′ + mid PU.1 C′ | CAA ATG CGG AAC TAT ATT GAG GAA CTA CAG G |

| Mid + 3′ PU.1 | TCA ATA TAG TTC CGC ATT TGC TAC GCG TTA AGT TCC TG |

| Mid + 3′ PU.1 C′ | ATA CTG TAA AAA CAG GAA CTT AAC GCG TAG CAA ATG CGG AAC |

Double-stranded oligonucleotides were made by annealing positive-strand oligonucleotides to their complementary (C′) partners. The core of each PU.1 binding motif is underlined. Other known transcription factor binding motifs (Oct and CRE) were eliminated from the oligonucleotides by point mutations.

FIG. 3.

Scatchard analysis of recombinant PU.1 binding to the three PU.1 binding motifs in the EIAV LTR. (A) Representative Scatchard plot of PU.1 binding to the 5′ PU.1 binding motif. The average disassociation constant was determined to be 4.123 nM. (B) Representative Scatchard plot of PU.1 binding to the middle PU.1 binding motif. The average disassociation constant was determined to be 3.269 nM. (C) Representative Scatchard plot of PU.1 binding to the 3′ PU.1 binding motif. The average disassociation constant was determined to be 2.609 nM. (D) Average disassociation constants of PU.1 for the three motifs within the EIAV LTR. Values represent means and standard errors of three independent experiments. The inset graphs in panels A to C demonstrate the saturation of the oligonucleotides with PU.1.

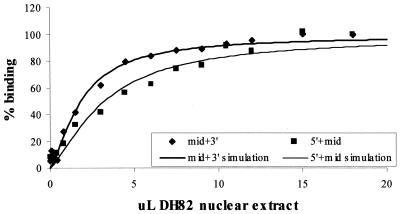

Since the modest differences in affinity of the sites could not account for the dramatic differences observed in the ability of the three sites to support maximal levels of LTR activity, we sought to determine if PU.1 bound to its sites independently or in a cooperative manner. EMSAs were performed with probes that contained either the two upstream PU.1 sites (5′ + mid PU.1) or the two downstream sites (mid + 3′ PU.1) (Table 1). Other transcription factor binding motifs that are known to be present in the EIAV enhancer were eliminated by point mutations in these oligonucleotides. For these studies, NEs from DH82 cells were used in order to analyze whether differences in binding affinities were observed in a more complex milieu of nuclear proteins. A constant amount of radiolabeled, double-stranded oligonucleotide was incubated with increasing quantities of NE. The bound and unbound complexes were separated, and the amount of bound complex was quantified, normalized, and plotted against the amount of NE added (Fig. 4). Best fit binding curves were generated and analyzed by using nonlinear least-squares (see Materials and Methods). Both the 5′ + mid PU.1 and mid + 3′ PU.1 oligonucleotide curves were hyperbolic rather than sigmoidal, indicating that PU.1 binding to the sites was not strongly cooperative. Consistent with the binding trends observed with the individual sites, the amount of NE needed to achieve 50% binding of the mid + 3′ PU.1 oligonucleotide was less (1.85 μl of NE) than the quantity of upstream oligonucleotide needed (3.29 μl of NE), suggesting an enhanced affinity of the two downstream sites for PU.1.

FIG. 4.

Binding curves of DH82 NE to an oligonucleotide containing the 5′ and middle PU.1 sites (5′ + mid oligonucleotide; squares) or an oligonucleotide containing the middle and 3′ PU.1 sites (mid + 3′ oligonucleotide; diamonds). All other transcription factor binding motifs that are present in that region of the EIAV LTR enhancer were altered in the oligonucleotides by the introduction of point mutations in the appropriate locations. Lines through the data were simulated by using the association constants resolved from a fit of averaged data.

PU.1 site proximity to the promoter is required for optimal activity.

Since an altered affinity of PU.1 for the three binding sites did not appear to be able to account for the differences in relative importance of the three PU.1 sites in reporter assays, we investigated whether the location of the 3′ PU.1 site was instrumental in determining its transcriptional impact. The promoter-proximal PU.1 nucleotide sequence (GTTCCTGTT) was substituted for the 5′ and middle sites, and the 3′ motif was eliminated by point mutations to generate an LTR called p3′ UP (Fig. 5A). The p3′ UP LTR/CAT construct was compared to the other LTRs in the same experiments as those shown in Fig. 2. For simplicity, only the p3PU.1 and the pDel-3′ results are shown here for comparison. The levels of basal and Tat-transactivated activity for p3′ UP were significantly less than the p3PU.1 values and were equivalent to or slightly less than those for pDel-3′, which contained the two wild-type upstream PU.1 elements but was missing the 3′ PU.1 site (Fig. 5B and C). These findings indicate that the location and not the sequence of the PU.1 site was of primary importance for determining the strength of the motif.

FIG. 5.

Promoter-proximal location of the PU.1 site is critical for optimal Tat-transactivated expression of the LTR. (A) Constructs tested with transient transfections performed in DH82 cells. The 3′ PU.1 binding motif was substituted for both the 5′ and middle PU.1 motifs in 3′ UP. (B) Basal levels of CAT activity in DH82 cells. (C) Tat-transactivated levels of CAT activity.

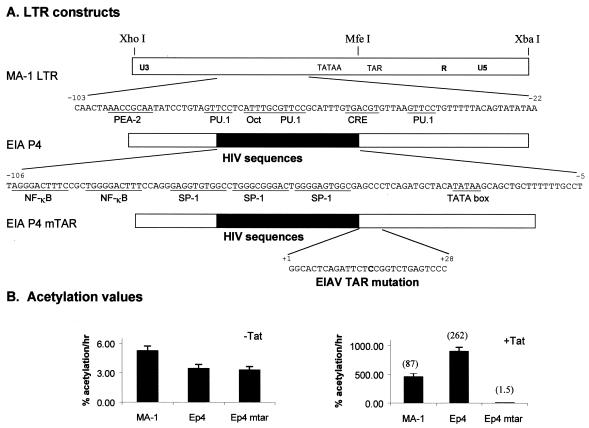

To further explore the role of PU.1 sites in Tat transactivation, we determined if the sites were required for EIAV Tat transactivation of LTR in macrophages. The HIV enhancer-promoter-proximal elements, consisting of two NF-κB and three Sp1 sites, and the HIV promoter were substituted for the wild-type EIAV enhancer and promoter elements in a construct called pEIA P4 (Fig. 6A). In addition, for verification that EIAV TAR was required for EIAV Tat transactivation of the chimeric LTR in macrophages, the TAR sequences were mutated by introducing a G-to-C change within the loop structure of the TAR that had previously been shown to eliminate Tat transactivation (pP4mTAR) (3). Substitution of the HIV sequences for the EIAV sequences resulted in strong levels of basal and Tat-transactivated activity, and the Tat-dependent activation was eliminated by the TAR loop mutation. These findings indicate that, while a promoter-proximal PU.1 site enhances Tat transactivation in macrophages, it is not absolutely required. Furthermore, these studies are consistent with the ability of the HIV enhancer-promoter to substitute for the EIAV enhancer-promoter in fibroblast cell lines (5).

FIG. 6.

HIV enhancer-promoter elements substitute for the EIAV elements in macrophages. (A) Constructs tested in transient transfections performed in DH82 cells. pEIA P4 (30) contains the HIV enhancer-promoter region within the context of the EIAV LTR. (B) Basal levels of expression. (C) EIAV Tat-transactivated levels of expression.

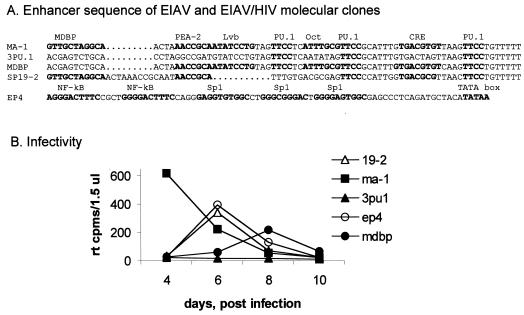

The three PU.1 sites are not sufficient for virus replication.

Previous studies within our laboratory suggested that an EIAV enhancer composed of three PU.1 sites might be sufficient to support virus replication in macrophages (27). To explore if the three sites could support replication, we tested the 3PU.1 LTR within the context of the infectious molecular clone pSP19-2 (34). The 3′ LTR was removed from pSP19-2 and an XhoI site was inserted at the env-LTR border. The p3PU.1 LTR, which contained an XhoI site at the 5′ LTR border, was ligated to the infectious clone. Ligation products were transfected into DH82 cells. Transfected cells were passaged over a several-week period to permit the spread of virus from the limited number of cells that were originally transfected. Transfected cell populations were periodically immunostained for EIAV antigens, and supernatants were tested for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity to monitor spread. 3PU.1/pSP19-2 did not spread in the DH82 cultures, and supernatant RT values did not increase over time, suggesting that the three PU.1 sites were not sufficient by themselves to support virus replication in DH82 cells (data not shown). However, EIAV antigen staining and low levels of supernatant RT were detectable in DH82 cells shortly after transfection. Equine monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) were infected with supernatants from 3PU.1/SP19-2 and a series of other constructs (Fig. 7A). Two wild-type EIAV constructs were used: the LTR from pSP19-2 and the MA.1 LTR (3) that is the parental LTR from which the 3PU.1 LTR was derived. Additionally, two other LTRs were tested for the ability to support virus replication. These included ΔMDBP/pSP19-2, which is an MA.1-derived LTR containing point mutations within the MDBP site that flanks the 5′ end of the EIAV enhancer, and EIA P4/pSP19-2, which contains the HIV enhancer-promoter sequences. RT-positive supernatants from DH82 cells that were infected or transfected with the various constructs were added to MDM cultures on the day of cell isolation. The medium was changed on day 2 and collected for RT analysis on days 4, 6, 8, and 10 (Fig. 7B). RT activity was readily detectable in supernatants from cultures infected with pSP19-2, MA-1/pSP19-2, EIA P4/pSP19-2, or ΔMDBP/pSP19-2, although RT activity was delayed by several days in the ΔMDBP/pSP19-2-infected culture. No RT activity was detected in supernatants from the 3PU.1/pSP19-2 infection. Genomic DNAs were extracted from the RT-positive MDM cultures and amplified for verification of the presence of the mutant enhancer region in the 5′ LTR position. The appropriate LTR was present and was the only one detected in each of the infections (data not shown). These findings indicate that despite the relatively strong reporter activity observed, the presence of the three ets motifs is not sufficient to drive EIAV replication, whereas a mutated EIAV enhancer containing a more intact enhancer region (ΔMDBP/pSP19-2) is able to replicate in MDMs.

FIG. 7.

Three PU.1 sites are not sufficient to support EIAV replication in equine MDMs. (A) Enhancer sequences of the molecular clones tested for infectivity. (B) RT activity of culture supernatants from EIAV-infected MDMs.

DISCUSSION

PU.1 is important for the expression of EIAV in macrophages (4, 27). Previous studies have indicated that nucleotides surrounding the core binding motif, GGAA (TTCC on the complementary strand), influence PU.1 binding to its cognate site (26, 27). Since the flanking nucleotides in each of the three PU.1 sites within the EIAV enhancer differ, we explored the ability of PU.1 to interact with each of the binding sites and determined the relative importance of each of the sites for LTR transcriptional activity. The three PU.1 sites within the EIAV LTR that had previously been identified by EMSAs (4, 5, 27) were protected from DNase I digestion in a footprinting experiment. Consistent with footprinting studies performed with other PU.1 binding motifs (13, 18, 40, 48), a broad region of 13 to 15 nucleotides was protected from digestion at each motif. A DNase I-hypersensitive band was present in the middle of the protected area immediately downstream from the TTCC core motif. Enhanced DNase I cleavage at this location has been observed with some, but not all, PU.1 motifs that have been previously footprinted and may result from an 8° bend in the DNA that occurs upon PU.1 binding, exposing the nucleotide and making it available for degradation (18, 19, 40). The presence of a bend in the DNA at that location is supported by crystallographic studies (24). While footprinting was only performed on one strand in our studies, the results clearly demonstrated PU.1 binding to all three sites and were consistent with footprinting studies that investigated binding on both strands (40, 48).

Reporter gene studies were performed with an enhancer region composed of only the three PU.1 sites. Transfection studies with a macrophage cell line demonstrated that the middle PU.1 site most strongly influenced basal levels of LTR expression. Loss of the middle site (pDel-mid) resulted in basal LTR expression levels that were no higher than expression from an LTR containing no PU.1 sites (pNo PU.1). These findings suggested that the middle site may bind to PU.1 most strongly or may interact with the other sites in a cooperative manner. However, our binding studies were not consistent with this possibility; the binding affinities of the three sites for PU.1 did not significantly differ and no evidence of cooperativity between the three sites was evident.

Upon the addition of Tat to the transfections, the importance of the promoter-proximal PU.1 motif became evident. The dramatic effect of the loss of the promoter-proximal PU.1 site on the Tat-transactivated activity of the LTR suggested that PU.1 binding to the 3′ site plays a different role in EIAV transcriptional regulation than PU.1 binding to the two upstream sites. While the 3′ PU.1 site was critical for maximal levels of expression in the context of the 3PU.1 LTR in macrophages, the site was not absolutely required, since the HIV enhancer was able to fully complement the loss of the EIAV enhancer.

As a component of an enhancer of cellular genes, a PU.1 binding motif is able to function in two very different regulatory environments, serving as the promoter-proximal element of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptor genes in myeloid cells and as the upstream enhancer sequences of the Ig kappa light chain and the Mu heavy chain intron enhancer of B cells (14). In the immunoglobulin enhancer sequences, PU.1 acts as a protein scaffold for other transcription factors. For example, it recruits the transcription factor Pip (PU.1 interacting partner) to the Ig kappa 3′ enhancer sequence (35), followed by the binding of c-fos and c-jun, to create a higher order transcription factor complex that acts to synergistically activate transcription. PU.1 mutants containing deletions in the acidic transactivation domain are still able to synergistically activate transcription from these enhancer sequences (36), suggesting that PU.1 serves an architectural role when the recruited transcription factors, and not PU.1, drive transcription. In contrast, in the enhancer-promoter of the M-CSF and GM-CSF receptor genes, the PU.1 binding site is located close to the transcription start site (45) and aids in the recruitment of the TFIID complex (20) as well as other transcription factors, such as C/EBP (31). In these myeloid cell-specific genes, the transactivation domain of PU.1 is required for the recruitment of basal transcriptional machinery. Nonetheless, a common feature to both of the roles that PU.1 plays is that the PU.1 protein serves as a transcriptional activator, promoting new transcription initiation.

In this study we identified a potentially new role for PU.1. This role in transcription may be specific to lentiviruses and similar to the function of promoter-proximal Sp1 sites in HIV. Consistent with our observations that the HIV enhancer elements readily replace the EIAV enhancer elements within the context of EIAV, we have also demonstrated that the EIAV enhancer can functionally replace the promoter-proximal Sp1 elements within HIV, albeit with a reduced efficiency of virus replication (38). Like other promoter-proximal PU.1 motifs, PU.1 may recruit proteins to the site of EIAV transcription. However, the fact that the dramatic impact of the 3′ PU.1 site was only observed in the presence of EIAV Tat suggests that the protein(s) recruited by PU.1 to the EIAV promoter-proximal site may be involved in transcription elongation. This recruitment may be in addition to any other proteins involved in transcription initiation. For instance, PU.1 binding to the EIAV promoter-proximal element may facilitate the recruitment of Tat and/or the cellular complex P-TEFb to the nascent RNA. The recruitment of proteins involved in transcription elongation to the HIV enhancer is well established. Barboric et al. demonstrated that RelA binding to the NF-κB sites, with the HIV enhancer, recruits P-TEFb to the HIV LTR and can promote transcript elongation in a Tat-independent manner (1). Similarly, Sp1 binding to its cognate sites recruits cyclin T1 to the HIV promoter and promotes HIV transcription in a Tat-independent manner (47). However, Sp1 binding to the promoter-proximal Sp1 motifs also promotes Tat-dependent HIV transcription (2, 7, 8, 22).

Despite the evident importance of the 3′ PU.1 site for Tat-transactivated expression of the EIAV LTR in macrophages, our infectivity studies indicated that the presence of three PU.1 sites was not sufficient for virus replication. Additional transcription factor motifs appear to be required. However, it is certainly possible and consistent with previous EMSA data (27) that PU.1 may be necessary for replication in macrophages. The other EIAV transcription factor binding motifs needed for virus replication in macrophages have yet to be elucidated. The delayed replication kinetics of the mutant virus ΔMDBP/pSP19-2 relative to the wild-type virus suggested that multiple binding elements may be required for EIAV replication in macrophages. This is in contrast to the EIAV LTR reporter gene expression described here and elsewhere, which has shown that multiple EIAV enhancer binding motifs can be mutated with the retention of relatively robust levels of basal and Tat-transactivated LTR activity (28). Our replication findings also appear to differ from findings for HIV by which as few as two of the five core enhancer elements (two NF-κB and three Sp1 sites) are sufficient for virus replication in most permissive cells (25, 33, 39). One possible explanation for the EIAV LTR requirement for numerous transcriptional elements could be the cell-specific nature of PU.1. Of the cells that are permissive for EIAV replication in tissue culture, only macrophages contain PU.1. The cell specificity of the transcription factor repertoire needed for EIAV replication may result in an added level of complexity to EIAV transcriptional regulation that is not present in HIV.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Atchison for the PU1/pET clone and C. Martin Stoltzfus and J. Lindsay Oaks for critical reviews of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grant NCI CA72063 to W.M. R.H. was supported by South Dakota EPSCOR and the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barboric, M., R. M. Nissen, S. Kanazawa, N. Jabrane-Ferrat, and B. M. Peterlin. 2001. NF-kappaB binds P-TEFb to stimulate transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell 8:327-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhout, B., and K. T. Jeang. 1992. Functional roles for the TATA promoter and enhancers in basal and Tat-induced expression of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 66:139-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho, M., and D. Derse. 1991. Mutational analysis of the equine infectious anemia virus Tat-responsive element. J. Virol. 65:3468-3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carvalho, M., and D. Derse. 1993. The PU.1/Spi-1 proto-oncogene is a transcriptional regulator of a lentivirus promoter. J. Virol. 67:3885-3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho, M., M. Kirkland, and D. Derse. 1993. Protein interactions with DNA elements in variant equine infectious anemia virus enhancers and their impact on transcriptional activity. J. Virol. 67:6586-6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheevers, W. P., and T. C. McGuire. 1985. Equine infectious anemia virus: immunopathogenesis and persistence. Rev. Infect. Dis. 7:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun, R. F., and K. T. Jeang. 1996. Requirements for RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal domain for activated transcription of human retroviruses human T-cell lymphotropic virus I and HIV-1. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27888-27894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chun, R. F., O. J. Semmes, C. Neuveut, and K. T. Jeang. 1998. Modulation of Sp1 phosphorylation by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat. J. Virol. 72:2615-2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clabough, D. L., D. Gebhard, M. T. Flaherty, L. E. Whetter, S. T. Perry, L. Coggins, and F. J. Fuller. 1991. Immune-mediated thrombocytopenia in horses infected with equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 65:6242-6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dignam, J. D., R. M. Lebovitz, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1475-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorn, P. L., and D. Derse. 1988. cis- and trans-acting regulation of gene expression of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 62:3522-3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.English, D., and B. R. Andersen. 1974. Single-step separation of red blood cells. Granulocytes and mononuclear leukocytes on discontinuous density gradients of Ficoll-Hypaque. J. Immunol. Methods 5:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng, X., S. L. Teitelbaum, M. E. Quiroz, S. L. Cheng, C. F. Lai, L. V. Avioli, and F. P. Ross. 2000. Sp1/Sp3 and PU.1 differentially regulate beta(5) integrin gene expression in macrophages and osteoblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8331-8340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher, R. C., M. C. Olson, J. M. Pongubala, J. M. Perkel, M. L. Atchison, E. W. Scott, and M. C. Simon. 1998. Normal myeloid development requires both the glutamine-rich transactivation domain and the PEST region of transcription factor PU.1 but not the potent acidic transactivation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4347-4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher, R. C., and E. W. Scott. 1998. Role of PU.1 in hematopoiesis. Stem Cells 16:25-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorman, C., R. Padmanabhan, and B. H. Howard. 1983. High efficiency DNA-mediated transformation of primate cells. Science 221:551-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham, F. L., J. Smiley, et al. 1977. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 36:59-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross, P., C. H. Arrowsmith, and R. B. Macgregor, Jr. 1998. Hydroxyl radical footprinting of DNA complexes of the ets domain of PU.1 and its comparison to the crystal structure. Biochemistry 37:5129-5135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross, P., A. A. Yee, C. H. Arrowsmith, and R. B. Macgregor, Jr. 1998. Quantitative hydroxyl radical footprinting reveals cooperative interactions between DNA-binding subdomains of PU.1 and IRF4. Biochemistry 37:9802-9811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagemeier, C., A. J. Bannister, A. Cook, and T. Kouzarides. 1993. The activation domain of transcription factor PU.1 binds the retinoblastoma (RB) protein and the transcription factor TFIID in vitro: RB shows sequence similarity to TFIID and TFIIB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:1580-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines, R., and W. Maury. 2001. DH82 cells: a macrophage cell line for the replication and study of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. Methods 95:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, L. M., and K. T. Jeang. 1993. Increased spacing between Sp1 and TATAA renders human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication defective: implication for Tat function. J. Virol. 67:6937-6944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, M. L. and S. G. Frasier. 1985. Non-linear least squares analysis. Methods Enzymol. 117:301-342. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kodandapani, R., F. Pio, C. Z. Ni, G. Piccialli, M. Klemsz, S. McKercher, R. A. Maki, and K. R. Ely. 1996. A new pattern for helix-turn-helix recognition revealed by the PU.1 ETS-domain-DNA complex. Nature 380:456-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard, J., C. Parrott, A. J. Buckler-White, W. Turner, E. K. Ross, M. A. Martin, and A. B. Rabson. 1989. The NF-κB binding sites in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat are not required for virus infectivity. J. Virol. 63:4919-4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, S. L., W. Schlegel, A. J. Valente, and R. A. Clark. 1999. Critical flanking sequences of PU.1 binding sites in myeloid-specific promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 274:32453-32460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maury, W. 1994. Monocyte maturation controls expression of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 68:6270-6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maury, W., S. Bradley, B. Wright, and R. Hines. 2000. Cell specificity of the transcription-factor repertoire used by a lentivirus: motifs important for expression of equine infectious anemia virus in nonmonocytic cells. Virology 267:267-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maury, W., S. Perryman, J. L. Oaks, B. K. Seid, T. Crawford, T. McGuire, and S. Carpenter. 1997. Localized sequence heterogeneity in the long terminal repeats of in vivo isolates of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 71:4929-4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maury, W. J., S. Carpenter, K. Graves, and B. Chesebro. 1994. Cellular and viral specificity of equine infectious anemia virus Tat transactivation. Virology 200:632-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagulapalli, S., J. M. Pongubala, and M. L. Atchison. 1995. Multiple proteins physically interact with PU.1. Transcriptional synergy with NF-IL6 beta (C/EBP delta, CRP3). J. Immunol. 155:4330-4338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oaks, J. L., T. C. McGuire, C. Ulibarri, and T. B. Crawford. 1998. Equine infectious anemia virus is found in tissue macrophages during subclinical infection. J. Virol. 72:7263-7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parrott, C., T. Seidner, E. Duh, J. Leonard, T. S. Theodore, A. Buckler-White, M. A. Martin, and A. B. Rabson. 1991. Variable role of the long terminal repeat Sp1-binding sites in human immunodeficiency virus replication in T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 65:1414-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Payne, S. L., J. Rausch, K. Rushlow, R. C. Montelaro, C. Issel, M. Flaherty, S. Perry, D. Sellon, and F. Fuller. 1994. Characterization of infectious molecular clones of equine infectious anaemia virus. J. Gen. Virol. 75:425-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perkel, J. M., and M. L. Atchison. 1998. A two-step mechanism for recruitment of Pip by PU.1. J. Immunol. 160:241-252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pongubala, J. M., and M. L. Atchison. 1997. PU.1 can participate in an active enhancer complex without its transcriptional activation domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:127-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pongubala, J. M., C. Van Beveren, S. Nagulapalli, M. J. Klemsz, S. R. McKercher, R. A. Maki, and M. L. Atchison. 1993. Effect of PU.1 phosphorylation on interaction with NF-EM5 and transcriptional activation. Science 259:1622-1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed-Inderbitzin, E., and W. Maury. 2003. Cellular specificity of HIV-1 replication can be controlled by LTR sequences. Virology 314:680-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross, E. K., A. J. Buckler-White, A. B. Rabson, G. Englund, and M. A. Martin. 1991. Contribution of NF-κB and Sp1 binding motifs to the replicative capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: distinct patterns of viral growth are determined by T-cell types. J. Virol. 65:4350-4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross, I. L., X. Yue, M. C. Ostrowski, and D. A. Hume. 1998. Interaction between PU.1 and another Ets family transcription factor promotes macrophage-specific basal transcription initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 273:6662-6669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sellon, D. C. 1993. Equine infectious anemia. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 9:321-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shea, M. A., B. R. Sorensen, S. Pedigo, and A. S. Verhoeven. 2000. Proteolytic footprinting titrations for estimating ligand-binding constants and detecting pathways of conformational switching of calmodulin. Methods Enzymol. 323:254-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sorensen, B. R., and M. A. Shea. 1998. Interactions between domains of apo calmodulin alter calcium binding and stability. Biochemistry 37:4244-4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strauss-Soukup, J. K., and L. J. Maher III. 1997. Role of asymmetric phosphate neutralization in DNA bending by PU.1. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31570-31575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenen, D. G., R. Hromas, J. D. Licht, and D. E. Zhang. 1997. Transcription factors, normal myeloid development, and leukemia. Blood 90:489-519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Dijk, T. B., B. Baltus, E. Caldenhoven, H. Handa, J. A. Raaijmakers, J. W. Lammers, L. Koenderman, and R. P. de Groot. 1998. Cloning and characterization of the human interleukin-3 (IL-3)/IL-5/ granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor betac gene: regulation by Ets family members. Blood 92:3636-3646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yedavalli, V. S., M. Benkirane, and K. T. Jeang. 2003. Tat and trans-activation-responsive (TAR) RNA-independent induction of HIV-1 long terminal repeat by human and murine cyclin T1 requires Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:6404-6410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ying, H., J. F. Chang, and J. R. Parnes. 1998. PU.1/Spi-1 is essential for the B cell-specific activity of the mouse CD72 promoter. J. Immunol. 160:2287-2296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]