Abstract

Nerve functions require phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) that binds to ion channels, thereby controlling their gating. Channel properties are also attributed to serotonin transporters (SERTs); however, SERT regulation by PIP2 has not been reported. SERTs control neurotransmission by removing serotonin from the extracellular space. An increase in extracellular serotonin results from transporter-mediated efflux triggered by amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Herein, we altered the abundance of PIP2 by activating phospholipase-C (PLC), using a scavenging peptide, and inhibiting PIP2-synthesis. We tested the effects of the verified scarcity of PIP2 on amphetamine-triggered SERT functions in human cells. We observed an interaction between SERT and PIP2 in pull-down assays. On decreased PIP2 availability, amphetamine-evoked currents were markedly reduced compared with controls, as was amphetamine-induced efflux. Signaling downstream of PLC was excluded as a cause for these effects. A reduction of substrate efflux due to PLC activation was also found with recombinant noradrenaline transporters and in rat hippocampal slices. Transmitter uptake was not affected by PIP2 reduction. Moreover, SERT was revealed to have a positively charged binding site for PIP2. Mutation of the latter resulted in a loss of amphetamine-induced SERT-mediated efflux and currents, as well as a lack of PIP2-dependent effects. Substrate uptake and surface expression were comparable between mutant and WT SERTs. These findings demonstrate that PIP2 binding to monoamine transporters is a prerequisite for amphetamine actions without being a requirement for neurotransmitter uptake. These results open the way to target amphetamine-induced SERT-dependent actions independently of normal SERT function and thus to treat psychostimulant addiction.

Keywords: phosphoinositide, reuptake, release, mass spectrometry, amperometry

Phosphoinositides are concentrated within the inner leaflets of plasma membranes where they serve as membrane anchors for cytoplasmic proteins and as signaling molecules (1). Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is produced by 1-phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI-4 kinase) and PIP-5 kinase through the sequential phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol. PIP2 is the precursor of two important second messengers: inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol [DAG (2)]. These two PIP2 products result from cleavage by phospholipase C (PLC) that is activated via receptors coupled to PLC. IP3 stimulates Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, whereas DAG directly activates most of the known protein kinase C isoforms. However, PIP2 is not only a precursor for second messengers but is also by itself important for signaling as it serves as an anchor for protein kinase C (3), directly binds to various membrane proteins (1), and is enriched in membrane rafts (4). Thereby, PIP2 controls essential functions of neurons, such as exocytosis (5), endocytosis (6), and transmembrane ion fluxes (7, 8).

Ion fluxes have also been observed in neurotransmitter:sodium symporters (NSSs). Members of this protein family, such as the transporters for dopamine (DAT), norepinephrine (NET), serotonin (5HT; SERT), and GABA (GAT), mediate uptake of released neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft. In addition, they are targets for addictive drugs such as amphetamines (9). Ion fluxes through these proteins are required for amphetamine-evoked substrate efflux but not for transmitter reuptake (10).

In contrast to neuronal ion channels and ion transporters, NSSs have not been reported to be regulated by PIP2, although other plasma membrane constituents such as cholesterol are required for the proper function of SERT (11–13) and DAT (14). Herein, we reveal SERT as a unique binding partner of membrane PIP2, characterize the binding site involved, and show that PIP2 is necessary for amphetamine actions but not for substrate reuptake. By targeting this interaction, one could thus prevent the contribution of SERT to addiction without affecting its physiological function.

Results and Discussion

Plasma Membrane PIP2 Is Required for SERT-Mediated Current.

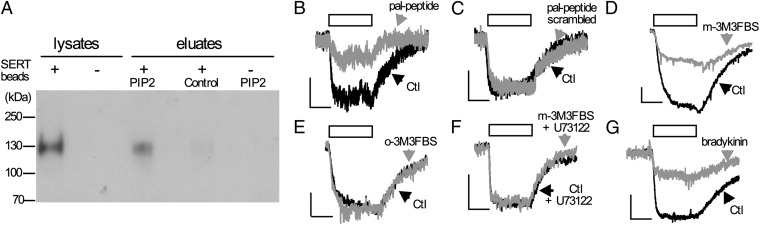

An interaction between PIP2 and SERT was established using PIP2-coated beads and proteins solubilized from human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells stably expressing the human SERT (HEK-SERT cells; Fig. 1A) (15). The direct interaction of PIP2 with ion channels and exchange proteins is required to permit ion fluxes in those proteins (8, 16). To test for analogous phenomena in SERT, currents through this transporter were triggered by the application of a substrate such as para-chloroamphetamine (pCA) (17). To disrupt PIP2 interactions, a palmitoylated peptide was used (Pal-HRQKHFEKRR; 10 µM), which is known to inhibit the effects of PIP2 on ion channels by binding to its polar head groups (18). This peptide reduced the pCA-induced SERT-mediated currents (Fig. 1B; 82.9 ± 5.1% inhibition; n = 4). A scrambled peptide (PAL-HAQKHFEAAA; 10 µM) unable to bind PIP2 did not exert any effect on SERT-mediated currents (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

PIP2 binding to SERT and regulation of SERT-mediated currents. (A) Lysates of either HEK293 cells expressing YFP-SERT (+) or nontransfected HEK293 (−) cells were incubated with either PIP2-coated beads or control beads. Samples of these lysates or proteins eluted from these beads were separated by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with an anti-GFP antibody. (B–G) Current traces from single HEK293-SERT cells; application of pCA (3 µM) is indicated by the bar: traces were obtained in the presence (gray) and absence (black; Ctl) of 10 µM pal-HRQKHFEKRR (pal-peptide in B), 10 µM scrambled peptide (C), 10 µM m-3M3FBS (D), 10 µM o-3M3FBS (E), 10 µM m-3M3FBS plus 3µM U72133 (F), or 10 nM bradykinin (G). The peptides, m-3M3FBS, o-3M3FBS, m-3M3FBS plus U72133, or 10nM bradykinin had been present for 20 min before the currents were recorded. Cells in G were coexpressing B2 bradykinin receptors. (Calibration bars, 2 pA and 2 s.)

We used the specific PLC activator m-3M3FBS {2,4,6-trimethyl-N-[3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]benzenesulfonamide} (19) to deplete membrane-associated PIP2. In cells treated with m-3M3FBS (10 μM) for 10 min, PIP2 contents were reduced to 49 ± 4% in comparison with cells treated with o-3M3FBS, an inactive ortho-analog, as quantified by MALDI-TOF (Fig. S1A). m-3M3FBS (10 μM) led to a significant decrease in pCA-induced SERT-mediated currents (Fig. 1D; 58.3 ± 8.9% inhibition; n = 7), whereas o-3M3FBS had no such effect (Fig. 1E; 6.8 ± 5.3% inhibition; n = 7). SERT-mediated current is not only induced by amphetamines such as pCA but also by the physiological substrate 5HT itself (20). Application of m-3M3FBS, but not o-3M3FBS, significantly reduced 5HT-induced currents (74.6 ± 8.1% inhibition, n = 4). Cells were treated with the PLC inhibitor U73122 to confirm that the effect of m-3M3FBS was caused by an activation of PLC; thereafter, m-3M3FBS failed to affect pCA-induced currents (0.1 ± 0.02% inhibition, n = 4; Fig. 1F).

To activate PLC by physiological means, B2 bradykinin receptors (B2Rs) were expressed in HEK-SERT cells, activation of which is known to tightly control the PIP2 content of the plasma membrane by PLC-mediated hydrolysis (21). pCA-induced current was significantly reduced by 59.6 ± 7.7% (n = 5) on addition of bradykinin (Fig. 1G). This effect was mediated by B2R activation because coapplication of the B2R-specific antagonist Hoe 140 (100 nM) attenuated the B2R-mediated effect on the SERT current (9.9 ± 3.8% inhibition, n = 5; sample trace in Fig. S1B). Thus, SERT interacts with PIP2 and amphetamine induced currents through the transporter can be altered by reducing PIP2 or by interfering with PIP2-protein interactions.

PIP2 Depletion Inhibits SERT-Mediated Efflux but Not Influx.

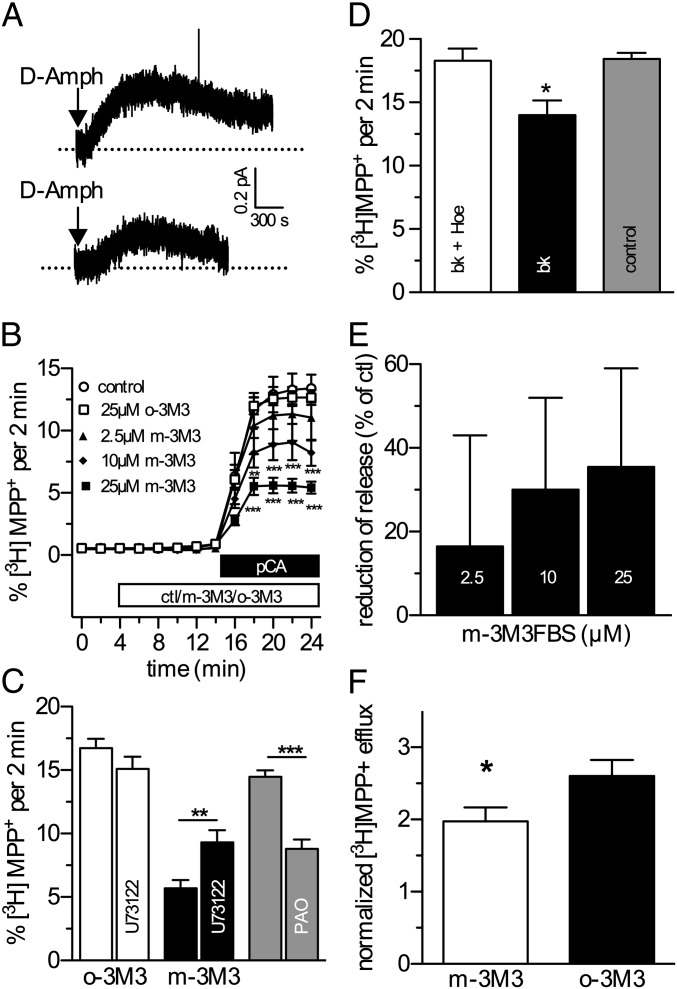

Currents through NSS family members are carried by sodium ions (22), and this sodium influx is believed to trigger transporter-mediated substrate efflux (23, 24). Therefore, the consequences of disrupting SERT-PIP2 interactions by the interfering palpeptide were also tested with respect to reverse transport using single cell microamperometry as previously described for DAT (24). Amperometric signals from HEK-SERT cells patch-loaded with 5HT were significantly reduced in the presence of 10 µM palpeptide (Fig. 2A, n = 6; P < 0.05, two-tailed Student t test).

Fig. 2.

PIP2 regulation of SERT-mediated efflux. (A) Representative oxidative currents from HEK-SERT cells. d-Amph (10 µM) was added as indicated by the arrows. Traces were obtained from cells loaded with either 10 µM scrambled peptide (upper trace) or pal-HRQKHFEKRR. (B) Time course of pCA-induced, SERT-mediated efflux of [3H]MPP+ from HEK-SERT cells. The cells were loaded with 0.1 µCi [3H]MPP+ and superfused, and 2-min fractions were collected. The indicated concentrations of m-3M3FBS or 25 µM o-3M3FBS were added to the superfusion buffer at minute 4. At minute 14, pCA (3 µM) was added to induce efflux. Efflux of radioactivity per 2-min fraction is expressed as percentage of radioactivity present in the cells at the beginning of that fraction (n = 6; two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test: **P < 0.01 or ***P < 0.001). (C) Experiments were carried out as shown in B; 25 µM m-3M3FBS or o-3M3FBS, in the absence or presence of 3 µM U73122, was added at minute 4. Similarly, 30 µM PAO was compared against control. Bar graphs represent efflux in percent of total radioactivity between minutes 22 and 24 (n = 5–37; two-tailed Mann–Whitney test: **P < 0.01 or ***P < 0.001). (D) Experiments were carried out as shown in B; pCA-induced, SERT-mediated efflux of [3H]MPP+ from HEK-SERT cells coexpressing B2 bradykinin receptors. Bradykinin (10 nM), either alone or together with 100 nM Hoe 140, was added to the superfusion buffer at minute 4. At minute 14, pCA (3 µM) was added to induce efflux (n = 3; one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test and is denoted by *P < 0.05). (E) Concentration dependence of m-3M3FBS treatment on the reduction of efflux in HEK293-DAT or HEK293-NET cells (n = 3; d-amphetamine, 3 µM). Cells were treated essentially as described in B. (F) Rat hippocampal slices were preloaded with 0.1 µM [3H]MPP+, and SERT-mediated efflux was induced by 3 µM pCA in the presence of m-3M3FBS or o-3M3FBS. Nomifensine (100 nM) was present throughout the experiment to block potential contributions from NET and DAT. Efflux is presented as in C–E. Statistically significant differences were assessed by Student t test (P < 0.05; n = 6, performed in triplicate).

This result raises the question of whether 5HT uptake might also be affected by modulating PIP2 levels: PIP2 levels were reduced by m-3M3FBS, but not o-3M3FBS, as reported above (Fig. 1D). As uptake cannot be measured in single cells, these experiments were carried out in populations of HEK-SERT cells. Neither agent induced significant alterations compared with vehicle (Table S1). In addition to [3H]substrate uptake, we also examined pCA uptake as quantified by HPLC (25). Thereby, we ruled out that the pCA that is used as the trigger for transporter-mediated efflux may be differently handled by the transporter: again, neither m-3M3FBS nor o-3M3FBS had any significant effect (867.4 ± 112.2 and 843.6 ± 124.8 pmol/100 µL, respectively; n = 4). The disparity between PIP2-sensitive SERT-mediated current (Fig. 1) and -insensitive uptake supports previous observations of uncoupled ion fluxes through SERT (20), which may additionally require an interaction with syntaxin 1A (22).

HEK-SERT cells were preloaded with the nondegradable substrate, tritiated methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), and continuously superfused until a baseline was established. SERT-dependent [3H]MPP+ efflux was induced by pCA (3 µM) (26) and measured by liquid scintillation counting. m-3M3FBS reduced this efflux in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). Again, o-3M3FBS had no effect (Fig. 2B). The inhibitory action of m-3M3FBS was attenuated by the PLC inhibitor U73122 (5 µM; Fig. 2C).

PI-4-kinase is involved in the synthesis of PIP2; its inhibition causes effects similar to those of PLC activation, but it is independent of PLC activity and products (27). Superfusion of [3H]MPP+-loaded HEK-SERT cells with phenyl-arseneoxide (PAO; 30 µM), a PI-4-kinase inhibitor, for 10 min before the addition of pCA resulted in a reduction of pCA-induced efflux (Fig. 2C; n = 12–16, P < 0.001 compared with control; one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test).

In cells coexpressing B2R, the addition of bradykinin (10 nM) significantly reduced pCA-triggered efflux (Fig. 2D; P < 0.05 compared with control; one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc test), which was prevented by the B2R antagonist Hoe 140 (100 nM; Fig. 2D). Thus, depletion of membrane PIP2 through PLC-dependent or -independent mechanisms, or interference with PIP2 protein interactions, reduced transporter-mediated sodium currents and substrate efflux. PIP2 sensitivity of [3H]MPP+ efflux was also found with the norepinephrine transporter: m-3M3FBS reduced d-amphetamine–induced efflux from HEK293-NET cells (Fig. 2E; n = 3). Furthermore, the physiological significance of our findings can be demonstrated by the sensitivity of pCA-induced [3H]MPP+-efflux from rat hippocampal slices toward PIP2 hydrolysis by m-3M3FBS (Fig. 2F). Thus, activation of PLC affected efflux through both recombinant and natively expressed monoamine transporters.

Second-Messenger Systems Are Activated but Do Not Contribute to PIP2 Effects on SERT: PKC and Ca2+.

Cleavage of PIP2 by PLC yields DAG, which activates PKC, leading to translocation from the cytosol to the membrane. The PKC-β II isoform is the most relevant for amphetamine-induced phosphorylation of transporters (28), and PKC is involved in the initiation of transporter-mediated efflux (25). In HEK-SERT cells, m-3M3FBS, but not o-3M3FBS, translocated recombinant fluorescent β II PKC to the membrane (Fig. S2A), indicative of PKC activation. Moreover, the PKC inhibitor GF109203X (1 µM) significantly diminished SERT-mediated efflux (Fig. S2B), but failed to alter the PIP2-dependent inhibition of efflux by m-3M3FBS (Fig. S2B). Thus, and apparently counterintuitive, the observed change in PKC activity on PLC activation by m-3M3FBS cannot be accounted for as the reason for the pronounced reduction in pCA-induced efflux.

PLC activation also increases the concentration of IP3, which in turn triggers the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores after binding to IP3 receptors; Ca2+ may play a role in transporter-mediated efflux as previously reported for the DAT (29). However, incubation of HEK-SERT cells with the membrane permeant Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM (50 µM) did not affect pCA-induced [3H]MPP+ efflux, whether m-3M3FBS was present or not (Fig. S2C). Likewise, the inhibition of pCA-induced current by m-3M3FBS was not altered by BAPTA-AM (control: 27.71 ± 11.42% vs. in the presence of BAPTA-AM: 31.6 ± 6.4%, n = 5; P > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test). Thus, changes in intracellular Ca2+ did not mediate the effects of PLC activation on amphetamine-induced currents and efflux.

Apart from shifting monoamine transporters from a reluctant to a willing state in terms of efflux, PKC also induces redistribution from the cell surface to intracellular compartments (30). However, within an exposure time of 20 min, neither m-3M3FBS nor o-3M3FBS led to the internalization of SERT in confocal microscopy and cell surface biotinylation experiments (Fig. S2 D and E). Nevertheless, activation of PKC by β-PMA significantly reduced cell surface expression of SERT as shown by biotinylation and a reduction in the Vmax of 5HT uptake (Fig. S2F; P < 0.05, n = 4; paired two-tailed Student t test). Thus, the PIP2 hydrolysis products, IP3 and DAG, were not involved in the modulation of transporter-mediated currents and efflux by PLC activation, indicating that the loss of PIP2 was the decisive mechanism.

PIP2 Does Not Regulate GAT1 Activity, Another Member of the NSS Family.

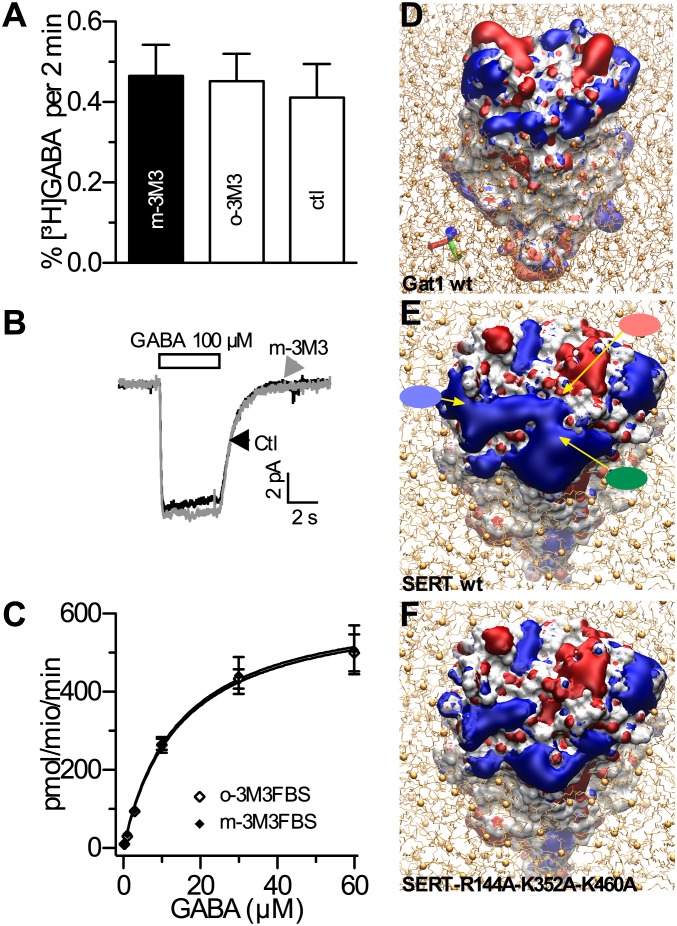

We investigated substrate efflux through the GABA transporter GAT1, a more distantly related member of the NSS family (31), to learn whether the above results might be universally valid for all NSSs. However, release of [3H]GABA from HEK cells stably expressing rat GAT1 (HEK-GAT1 cells) remained unaffected even at the highest m-3M3FBS concentrations tested (Fig. 3A). Likewise, GABA-evoked currents in HEK-GAT1 cells were not affected by 10 µM m-3M3FBS (Fig. 3B). Nevertheless, the PIP2 levels of HEK-GAT1 cells were decreased after application of m-3M3FBS (Fig. S3) to an extent comparable to those in HEK-SERT cells (Fig. 1D). Thus, GABA transporters are insensitive toward changes in PIP2 levels as suggested earlier (16), but it must be mentioned that GAT1 is insensitive to amphetamines, and specific “releasers” have not been identified for GAT1 (26).

Fig. 3.

Differences between SERT and GAT-1 in PIP2 sensitivity. (A) Efflux of [3H]GABA from HEK-GAT1 cells. The cells were loaded with 0.2 µM [3H]GABA and superfused, and 2-min fractions were collected (as shown for SERT in Fig. 2); 25 µM of m-3M3FBS or o-3M3FBS was added to the superfusion buffer at minute 4. At minute 14, GABA (333 µM) was added to induce efflux. Bar graphs represent efflux in percent of total radioactivity between minutes 22 and 24 (n = 4). (B) Current traces from single HEK-GAT1 cells; application of GABA (100 µM) is indicated by the bar; traces were obtained in the presence (gray) and absence (black; Ctl) of 10 µM m-3M3FBS. (C) HEK-GAT1 cells in 24-well plates were preincubated in Krebs–Ringer–Hepes (KHB) buffer with the respective substances for 15 min before 0.2 µM [3H]GABA was added for 3 min; nonspecific uptake was measured in the presence of 10 µM tiagabine. Subsequently, the cells were washed with ice-cold buffer and lysed, and the cellular radioactive content was counted (n = 3). (D–F Electrostatic potential iso-surfaces of GAT1 (D), SERT (E), and SERT-R144A-K352A-K460A (F); red denotes negative potential and blue denotes positive potential. The colored ellipses point to the positions of residues R144 (red), K352 (green), and K460 (blue).

The sequence identity between SERT and GAT1 is low (∼20%) (31). Therefore, the apparent differences in PIP2 sensitivity might be based on structural heterogeneities. Ion channels bind PIP2 via positively charged intracellular domains (33). Hence, we compared the electrostatic potentials of GAT1 and SERT (Fig. 3 D and E).

In contrast to the scattered positively charged area that covers the cytosolic side of GAT1 (Fig. 3D), roughly half the intracellular face of SERT has a positive surface potential (Fig. 3E). Here, a conspicuous patch of positively charged amino acids including residues R144 (helix 2), K352 (helix 6), and K460 (helix 9) could attract negatively charged molecules such as PIP2. The size of the PIP2 headgroups (34) would perfectly fit in between these residues (10-Å distance; Fig. S4A). A triple mutation of these three positively charged residues to alanine is predicted to dramatically change the electrostatic potential surrounding the transporter at the center of its cytosolic side (Fig. 3F); the surface containing a positive potential becomes smaller in strength and in size. Furthermore, negative charged areas appear in the center of the transporter. Therefore, we hypothesized that such an amino acid exchange would reduce the attractive force for PIP2 binding.

Mutation of the Putative PIP2 Binding Site in SERT Eliminates Current and Efflux.

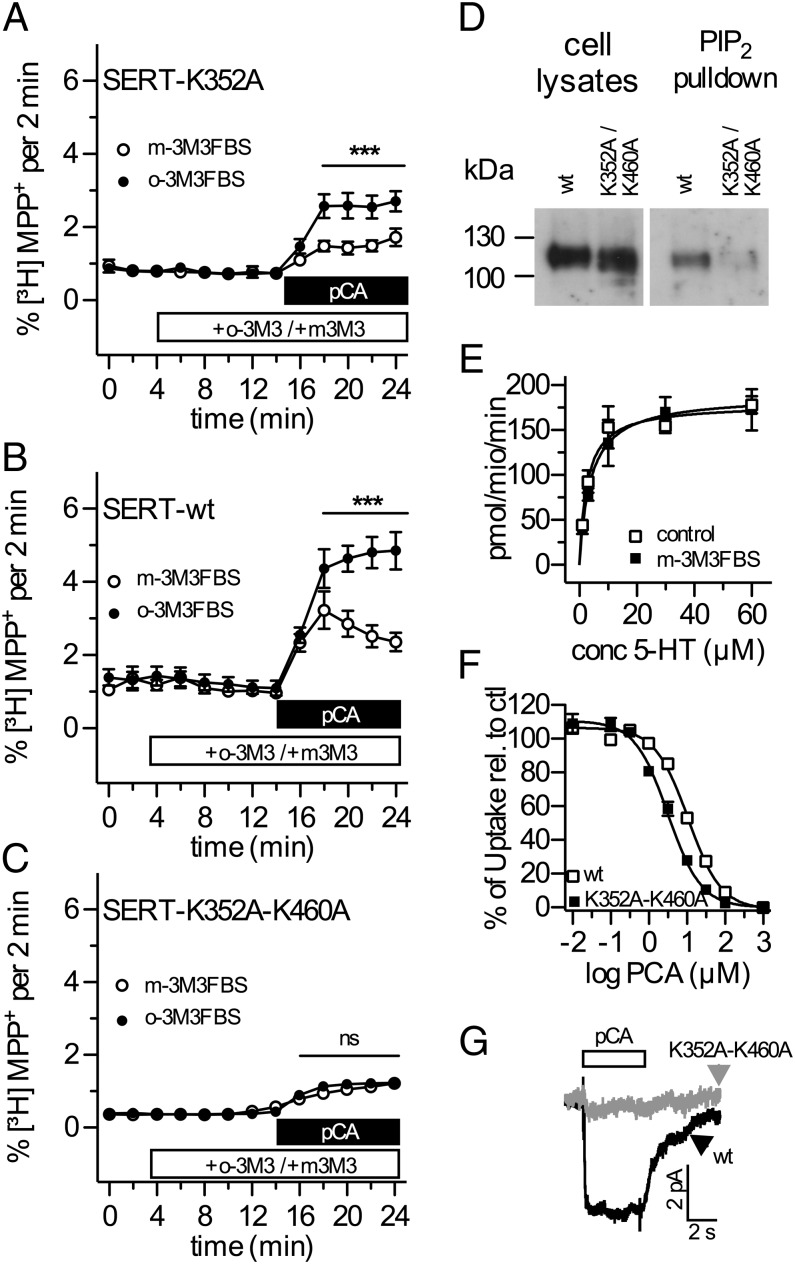

Single positively charged amino acids R144, K352, and K460 were replaced by alanines. The resulting single mutants were all expressed at the cell surface (Fig. S4B); they also displayed transport characteristics comparable to those of WT SERT (Table S2), and substrate efflux was inhibited by m-3M3FBS (Fig. 4A; Table S2). Thus, these single point mutations did not suffice to affect the interaction between PIP2 and SERT. This result is not surprising because up to five positively charged residues are typically involved in the binding of PIP2 to ion channels (33). Therefore, double mutations of these residues (SERT-R144A-K352A, SERT-R144A-K460A, SERT-K352A-K460A) were generated; these also led to surface expression levels and transport rates similar to those of WT SERT (Fig. 4E; Fig. S4C; Table S3). Moreover, competition of uptake by pCA was similar in mutants and WT SERT (Fig. 4F). In contrast, in all these double mutants, pCA-induced efflux was lower than in WT SERT (Fig. 4 B and C; Table S3). Nevertheless, efflux was not abolished, confirming that the conformational cycling of SERT was not entirely compromised by the mutation (Fig. 4 B and C). However, PIP2 hydrolysis triggered by m-3M3FBS affected pCA-induced efflux only in the SERT double mutants carrying the R144A mutation but not in the SERT-K352A-K460A variant (Fig. 4B; Table S3). In parallel with the marked reduction in pCA-induced substrate efflux, the SERT-K352A-K460A mutant lost its ability to (i) bind PIP2 (Fig. 4D) and (ii) mediate pCA-evoked currents (Fig. 4G). In contrast, the double mutants that originally included R144 showed pCA-induced currents that were comparable to those through WT SERT (Fig. S4D).

Fig. 4.

Lysine residues K352 and K460 in the cytosolic domain of SERT are required for binding and functional effects of PIP2. (A–C) Time course of pCA-induced, SERT-mediated efflux of [3H]MPP+ from HEK293 cells expressing SERT-K352A, YFP-tagged SERT, or SERT-K352A-K460A. The cells were loaded with 0.1 µCi [3H]MPP+ and superfused, and 2-min fractions were collected; 25 µM m-3M3FBS or o-3M3FBS was added to the superfusion buffer at minute 4. At minute 14, pCA (3 µM) was added to induce efflux. Efflux of radioactivity per 2-min fraction is expressed as percentage of radioactivity present in the cells at the beginning of that fraction (n = 3–5). Statistical significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test and is denoted by ***P < 0.001; n.s., no significance. (D) HEK293 cells stably expressing YFP-tagged SERT (WT) or SERT-K352A-K460A were solubilized (cell lysates) and pulled down with PIP2-coated beads. Eluted proteins from the beads were dissolved in 2× SDS loading buffer at 95 °C, separated by SDS/PAGE, and immunoblotted with an anti-GFP antibody. The images were derived from the same membrane with the same exposure time and represent three experiments with the same results. (E) Uptake of [3H]MPP+ by HEK293 cells expressing SERT-K352A-K460A was essentially carried out as described in Table S1 (n = 3). (F) Inhibition of 5HT uptake by pCA. Cells expressing SERT-K352A-K460A or WT SERT were incubated with 0.03 µM [3H]MPP+ and increasing concentrations of pCA as indicated (n = 4); after 3 min, the cells were washed and lysed, and radioactivity was determined. The IC50 values were 10.3 ± 0.9 and 3.7 ± 0.6 nM, respectively. (G) Current traces from single HEK293 cells expressing SERT-K352A-K460A (gray) or WT SERT (black); application of pCA (3 µM) is indicated by the bar.

This functional disparity between the three double mutants was not predicted by the electrostatic potentials shown in the model in Fig. 3E. However, estimating the distances between the mutated residues indicated that R144 is located in a very central position of SERT. This location precludes binding of PIP2 because it simply cannot be reached from the rim of the membrane (Fig. 3E; Fig. S4A). In addition, the mutation-induced change of electrostatic forces would even add to repel PIP2 from SERT because its central region now carries a more negative potential centered on the transporter vestibule (Fig. 3E).

As shown above, the activation of PLC either directly by m-3M3FBS or via B2 receptors reduced currents and reverse transport through SERT. Equivalent results were obtained when potential interactions of PIP2 with membrane proteins were prevented by interfering peptides, and direct binding between SERT and PIP2 was demonstrated. Together, these data reveal SERT to interact with and to be functionally regulated by PIP2.

Unlike the effects of the PIP2 binding peptides (18), the functional consequences of PLC activation may involve not only loss of PIP2, but also the generation of PIP2 cleavage products, DAG and IP3, and downstream signaling elements. Although loss of PIP2 from the cells under investigation as a result of PLC activation has been demonstrated, activation of PKC and increases in intracellular Ca2+ were evidenced not to be involved in the effects observed. Moreover, inwardly directed transport through SERT was not affected by PLC activation, thereby excluding general regulatory mechanisms such as changes in surface expression.

As previously reported for various ion channels (8), the present results reveal positively charged PIP2 binding sites within the intracellular domains of SERT. Mutational loss of charges within these regions led to largely reduced PIP2 binding to SERT and prevented the functional effects of PIP2 depletion (a huge decrease in SERT-mediated currents and substrate efflux), whereas 5HT uptake and its inhibition by competitors remained unaltered. These data confirm inward and outward transport as distinct mechanistic phenomena within monoamine transporters (10, 35). Hence, altered ion flux could regulate neuronal excitability; along those lines, the studies by Carvelli et al. do in fact speak to a role for DAT currents in vivo (36).

A segregation of currents and reverse transport from substrate uptake has also been identified in a rare variant of the human DAT, A559V, in a pedigree of patients diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (37). This mutation leads to a transporter no longer showing amphetamine-induced release of monoamines, as was observed here as consequence of either PIP2 depletion or specific amino acid exchanges. Thus, the selective interference with PIP2 binding to SERT to prevent amphetamine-induced efflux without affecting SERT-dependent reuptake may hold therapeutic promise for amphetamine-addicted patients.

Experimental Procedures

Experimental procedures for electrophysiology and amperometry have been performed as described (15, 16, 23, 35). Biochemical assays such as pull-down assays, biochemical tracer flux analysis, and HPLC determination of pCA have been reported earlier (22–25). More detailed information on the experimental procedures including MS, confocal laser scanning microscopy, and molecular modeling, and all reagents are provided in SI Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Shimadzu (MALDI Technologies Group, Manchester, UK) for providing the MALDI instrumentation. We acknowledge financial support from FWF Grants P18706, P22893, W1232, and F35-06 (to H.H.S.), W1232 and F35-02 (to G.F.E.), and P17611 (to S.B.); National Institutes of Health Grant DA13975 (to A.G.), and a Health Research Board/Marie Curie Postdoctoral mobility fellowship (to T.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1220552110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443(7112):651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolias KF, Cantley LC. Pathways for phosphoinositide synthesis. Chem Phys Lipids. 1999;98(1-2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(99)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marín-Vicente C, Nicolás FE, Gómez-Fernández JC, Corbalán-García S. The PtdIns(4,5)P2 ligand itself influences the localization of PKCalpha in the plasma membrane of intact living cells. J Mol Biol. 2008;377(4):1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pike LJ, Miller JM. Cholesterol depletion delocalizes phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate and inhibits hormone-stimulated phosphatidylinositol turnover. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(35):22298–22304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Paolo G, et al. Impaired PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis in nerve terminals produces defects in synaptic vesicle trafficking. Nature. 2004;431(7007):415–422. doi: 10.1038/nature02896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haucke V. Phosphoinositide regulation of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(Pt 6):1285–1289. doi: 10.1042/BST0331285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hilgemann DW, Ball R (1996) Regulation of cardiac Na+, Ca2+-exchange and KATP potassium channels by PIP2. Science 273(80):956–959. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gamper N, Shapiro MS. Regulation of ion transport proteins by membrane phosphoinositides. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(12):921–934. doi: 10.1038/nrn2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristensen AS, et al. SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters: Structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63(3):585–640. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sitte HH, Freissmuth M. The reverse operation of Na(+)/Cl(-)-coupled neurotransmitter transporters—why amphetamines take two to tango. J Neurochem. 2010;112(2):340–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guicheney P, et al. Platelet 5-HT content and uptake in essential hypertension: Role of endogenous digitalis-like factors and plasma cholesterol. J Hypertens. 1988;6(11):873–879. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198811000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scanlon SM, Williams DC, Schloss P. Membrane cholesterol modulates serotonin transporter activity. Biochemistry. 2001;40(35):10507–10513. doi: 10.1021/bi010730z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnani F, Tate CG, Wynne S, Williams C, Haase J. Partitioning of the serotonin transporter into lipid microdomains modulates transport of serotonin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(37):38770–38778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong WC, Amara SG. Membrane cholesterol modulates the outward facing conformation of the dopamine transporter and alters cocaine binding. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(42):32616–32626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilber B, et al. Serotonin-transporter mediated efflux: A pharmacological analysis of amphetamines and non-amphetamines. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(6):811–819. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilgemann DW, Feng S, Nasuhoglu C. The complex and intriguing lives of PIP2 with ion channels and transporters. Sci STKE. 2001;2001(111):re19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.111.re19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schicker K, et al. Unifying concept of serotonin transporter-associated currents. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(1):438–445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.304261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robbins J, Marsh SJ, Brown DA. Probing the regulation of M (Kv7) potassium channels in intact neurons with membrane-targeted peptides. J Neurosci. 2006;26(30):7950–7961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2138-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bae Y-S, et al. Identification of a compound that directly stimulates phospholipase C activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63(5):1043–1050. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mager S, et al. Conducting states of a mammalian serotonin transporter. Neuron. 1994;12(4):845–859. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutowski S, et al. Antibodies to the alpha q subfamily of guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein alpha subunits attenuate activation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis by hormones. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(30):20519–20524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quick MW. Regulating the conducting states of a mammalian serotonin transporter. Neuron. 2003;40(3):537–549. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sitte HH, et al. Carrier-mediated release, transport rates, and charge transfer induced by amphetamine, tyramine, and dopamine in mammalian cells transfected with the human dopamine transporter. J Neurochem. 1998;71(3):1289–1297. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71031289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khoshbouei H, Wang H, Lechleiter JD, Javitch JA, Galli A. Amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. A voltage-sensitive and intracellular Na+-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(14):12070–12077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seidel S, et al. Amphetamines take two to tango: An oligomer-based counter-transport model of neurotransmitter transport explores the amphetamine action. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(1):140–151. doi: 10.1124/mol.67.1.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sitte HH, et al. Quantitative analysis of inward and outward transport rates in cells stably expressing the cloned human serotonin transporter: Inconsistencies with the hypothesis of facilitated exchange diffusion. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59(5):1129–1137. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Várnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: Calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(2):501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson LA, Guptaroy B, Lund D, Shamban S, Gnegy ME. Regulation of amphetamine-stimulated dopamine efflux by protein kinase C beta. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(12):10914–10919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413887200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gnegy ME, et al. Intracellular Ca2+ regulates amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux and currents mediated by the human dopamine transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66(1):137–143. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitt KC, Reith MEA. Regulation of the dopamine transporter: Aspects relevant to psychostimulant drugs of abuse. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:316–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson N. The family of Na+/Cl- neurotransmitter transporters. J Neurochem. 1998;71(5):1785–1803. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beuming T, Shi L, Javitch JA, Weinstein H. A comprehensive structure-based alignment of prokaryotic and eukaryotic neurotransmitter/Na+ symporters (NSS) aids in the use of the LeuT structure to probe NSS structure and function. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70(5):1630–1642. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, Logothetis DE (2007) Molecular characteristics of phosphoinositide binding. Pflügers Archiv 455(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Haider S, Tarasov AI, Craig TJ, Sansom MSP, Ashcroft FM. Identification of the PIP2-binding site on Kir6.2 by molecular modelling and functional analysis. EMBO J. 2007;26(16):3749–3759. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robertson SD, Matthies HJG, Galli A. A closer look at amphetamine-induced reverse transport and trafficking of the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;39(2):73–80. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8053-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carvelli L, et al. Dopamine transporters depolarize neurons by a channel mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(45):16046–16051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403299101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazei-Robison MS, et al. Anomalous dopamine release associated with a human dopamine transporter coding variant. J Neurosci. 2008;28(28):7040–7046. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0473-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.