Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Chondrosarcomas are the most common primary chest wall malignancy. The mainstay of treatment is radical resection, which often requires chest wall reconstruction. This presents numerous challenges and more extensive defects mandate the use of microvascular free flaps. Selecting the most appropriate flap is important to the outcome of the surgery.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 71-year-old male presented with a large chondrocarcoma of the chest wall. The planned resection excluded use of the ipsilateral and contralateral pectoralis major flap because of size and reach limitations. The latissimus dorsi flap was deemed inappropriate on logistical grounds as well as potential vascular compromise. The patient was too thin for reconstruction using an abdominal flap. Therefore, following radical tumour resection, the defect was reconstructed with a methyl methacrylate polypropylene mesh plate for chest wall stability and an anterolateral thigh free flap in a single-stage joint cardiothoracic and plastic surgical procedure. The flap was anastomosed to the contralateral internal mammary vessels as the ipsilateral mammary vessels had been resected.

DISCUSSION

The outcome was complete resection of the tumour, no significant impact on ventilation and acceptable cosmesis.

CONCLUSION

This case demonstrates the complex decision making process required in chest wall reconstruction and the versatility of the ALT free flap. The ALT free flap ensured adequate skin cover, subsequent bulk, provided an excellent operative position, produced little loss of donor site function, and provided an acceptable cosmetic result.

Keywords: Chest wall reconstruction, Chondrosarcoma, Anterolateral thigh free flap, Flap selection, Respiratory function, Reconstructive algorithm

1. Introduction

Chest wall neoplasms account for 5% of all thoracic tumours,1 with the most common primary chest wall malignancy being chondrosarcoma. Chondrosarcomas usually originate from the anterior chest wall – from either the costochondral junctions or sternum. They have a wide age range of presentation but typically occur in patients 30–60 years old. They are slightly more common in males, with a male to female ratio of 1.3:1. Chondrosarcomas can present as painful or painless chest wall masses.2 At the time of presentation, 10% have pulmonary metastases.1 The overall five-year survival rates are greater than 60% but may be over 80% in patients without metastases. Poor prognostic factors include an age over 50 years, incomplete resection, synchronous metastases, and local recurrence.2

It has been shown that radiotherapy or chemotherapy may not be very effective in treating chondrosarcomas,3,4 particularly when low grade. The mainstay of treatment for chondrosarcomas, where possible, is complete excision sometimes with adjuvant therapy. In such cases, the primary aims of chest wall reconstruction are to ensure stability and good physiological functioning of the chest wall, as well as soft tissue closure of the defect. Good cosmesis is also a consideration. Loco-regional flaps are often the first choice for soft tissue coverage but due to the extensive resection often required part of the flap may be resected during tumour extirpation and their vascularity is often compromised. Furthermore, if the flap blood supply is tenuous there may be necrosis at the distal end and this can expose underlying organs leading to serious complications. Sometimes these patients have had radiotherapy making local flap options unreliable. For these reasons, some complex reconstructions require the use of microvascular free tissue transfer flaps.5

2. Case report

A 71-year-old male presented with a two-month history of an asymmetrical chest wall due to a large, slow-growing, painless right-sided mass. The patient was a non-smoker, otherwise well and was a keen tennis player.

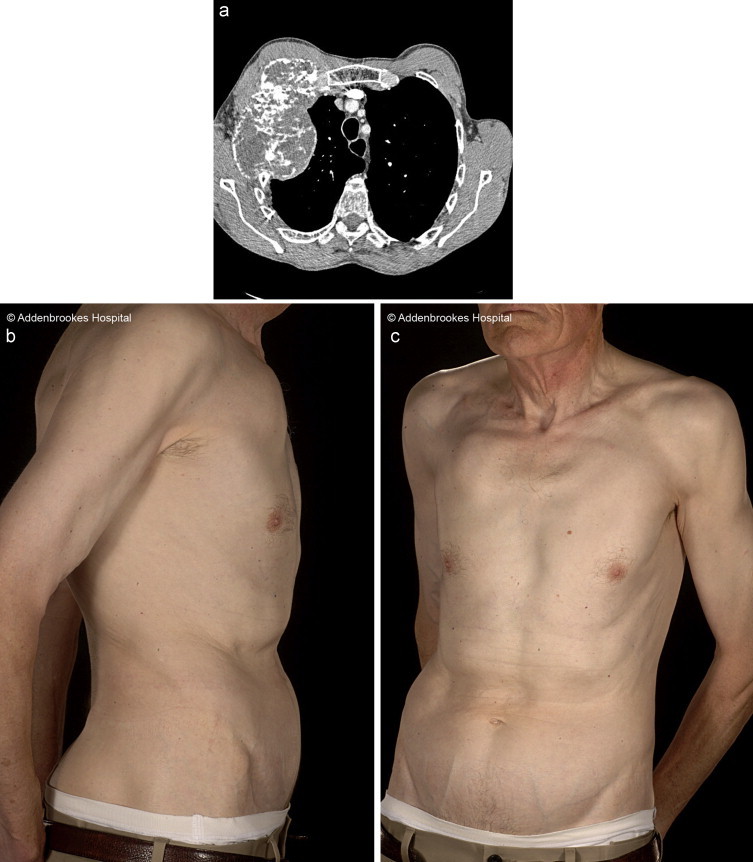

A chest CT scan (Fig. 1a) revealed features of a chondrosarcoma which impinged on the first and second ribs, manubrium, sternum and subclavian vessels. Abdominal and pelvic CT scans showed no evidence of metastatic disease. A pre-operative core biopsy of the mass confirmed a grade 2 chondrosarcoma. The overlying skin was freely mobile (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

(a) CT scan showing right-sided mass on chest wall and (b) pre-operative photos.

The patient was reviewed at the sarcoma multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting, where surgery was recommended in preference to primary radiotherapy or chemotherapy. He would require skeletal and soft tissue reconstruction and thus he was referred to the plastic surgery service. On assessment, a decision was made to use the contralateral anterolateral thigh (ALT) free flap. The advice of an orthopaedic surgeon and a vascular surgeon was sought in case the patient needed further bony excision or resection of the subclavian vessels.

2.1. Surgical details

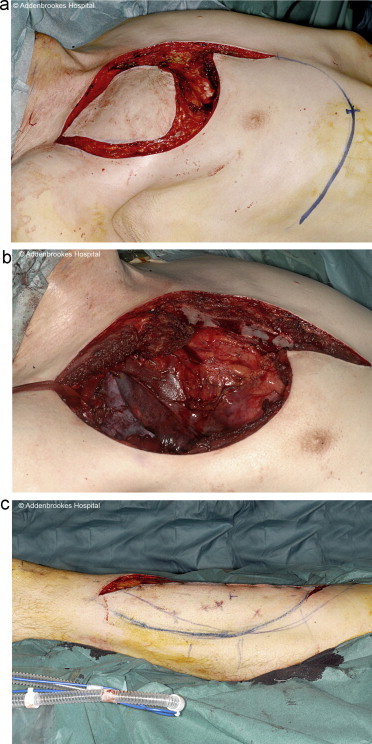

After intubation with an endotracheal double-lumen tube, the patient was positioned in the oblique supine position in order to allow adequate access for the resection both anteriorly and posteriorly. The patient was kept in this position throughout the procedure. Access was gained via a curvilinear incision jointly agreed by the plastic and cardiothoracic surgeons (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

(a) Incision for access to chest wall and post-excision and (b) left anterolateral thigh flap donor site.

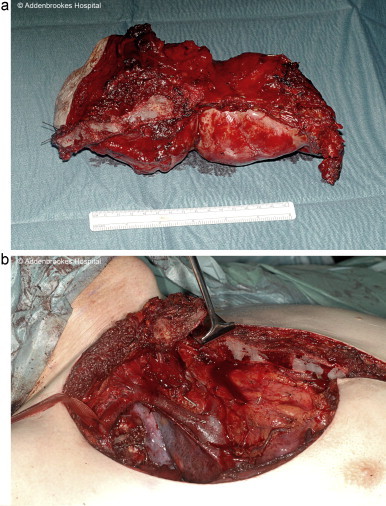

To avoid disruption of the sternoclavicular joint the manubrium was partly divided. An en bloc resection of the mass including most of ribs 1–3 and part of the sternum was performed. The mass was successfully dissected off the subclavian vessels (Fig. 3). Histology of the excised mass revealed a 16 cm × 8 cm × 8 cm lobulated, well circumscribed cartilaginous tumour replacing the second rib. There was no infiltration of the pectoralis muscles anteriorly or the pleura posteriorly and the resection margins were clear.

Fig. 3.

(a) Resected tumour and (b) site of resection approaching subclavian vessels.

Simultaneously, a fasciocutaneous ALT free flap incorporating a segment of the vastus lateralis muscle was harvested from the patient's left contralateral thigh (Fig. 2b).

The contralateral internal mammary recipient vessels were exposed using a standard total rib-sparing technique.6 A methyl methacrylate polypropylene mesh sandwich was fabricated and sutured to the fifth rib inferiorly and the sternum medially. It was felt that this would provide a stable base and avoid any risk of impingement on the clavicle and subclavian vessels which may have occurred if it had been taken higher. The ALT flap was successfully anastomosed to the internal mammary vessels end-to-end, with the flap pedicle positioned superficial to the sternum to enable easy exposure in case of subsequent re-exploration.

2.2. Post-surgery

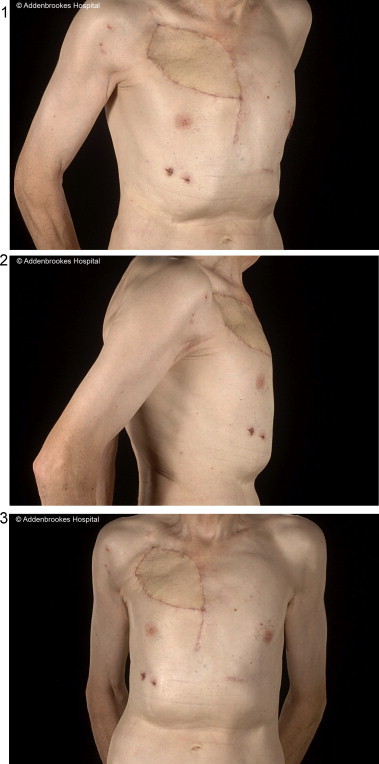

Post-operatively, he spent two days on the ICU and was discharged home on day 11. There were no significant respiratory complications. He developed a small seroma under the flap donor site, which was periodically aspirated. At six months post-operatively, he remains well and has an excellent range of shoulder movement. The cosmetic result was acceptable (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Post-operative photos of chest wall.

3. Discussion of flap choice

Chest wall reconstruction has many challenges. It needs to be durable, strong, airtight and must not be detrimental to ventilatory mechanics. Whether or not reconstructive surgery is indicated depends on several factors; for instance, large tumours of the chest wall require large resections which cannot be closed directly and hence need to be reconstructed.7 Rib resection may require reconstructive surgery.8 Small defects do not need reconstruction. Alternatives for skeletal reconstruction comprise biological or artificial mesh sheets, cement and more recently artificial metal ribs.9,10 Metal ribs may compromise future radiotherapy and should only be used if there is great confidence regarding the margins. Previous radiotherapy compromises healing, which may be improved by the use of nonadjacent flaps. The patient's body habitus also plays a role in determining reconstructive flap choice.

This patient posed a number of challenges and provided a pertinent example of the decision-making process involved in flap selection. A local flap could not be used for this patient because the ipsilateral pectoralis major flap had to be resected with the tumour, while the contralateral pectoralis major was too short, whether used as an advancement or turnover flap, to sufficiently fill the defect.

Regional flaps which were considered included a transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM), thoracodorsal artery perforator (TAP), intercostal artery perforator (ICAP), and the greater omentum. The TRAM flap was not ideal as an abdominal wall operation sacrificing an important muscle, in combination with an extensive thoracotomy involving multiple rib resection and partial sternectomy, would further compromise the patient's ventilatory mechanics. The right internal mammary vessels had also been sacrificed. Furthermore, the rectus abdominis flap would also weaken the abdominal wall and potentially lead to other complications such as hernia formation.11 Besides the patient was thin so had insufficient abdominal laxity to enable the harvest of a TRAM flap. The ICAP flap, although it would spare the abdominal musculature, relies on the presence of excess lateral truncal tissue, which the patient lacked. The greater omental flap would provide sufficient coverage12 but requires a split skin graft as well as a laparotomy and has no rigidity. A laparotomy would further compromise respiratory mechanics and has risks of intra-abdominal complications.13,14 The patient had insufficient bulk on his back so the TAP flap was not feasible with or without muscle (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Pre-operative photos demonstrating body habitus.

Free flap options in this instance included the latissimus dorsi (LD), ALT, tensor fascia lata (TFL) and deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP). Practical considerations in free flap chest wall reconstruction need to include; where the anastomoses would be made, the pedicle length, the volume of the flap, and the skin paddle size. The flap pedicle could not be anastomosed to vessels on the same side of the chest as these had been either sacrificed during the tumour resection (internal mammary and thoracoacromial axis) while attempting anastomoses to the subclavian vessels or its tributaries carried too high a risk of venous thrombosis following the substantial dissection trauma to it. The LD flap was a viable option15 but the logistics of the positioning of the patient would provide hindrance to the cardiothoracic and plastic surgeons operating simultaneously. The tumour was large (Fig. 3a) and reached the subclavian vessels (Fig. 3b) so resection or blunt damage to the vessels further excluded an ipsilateral pedicled LD flap, due again to the high venous thrombosis risk.

Pre-operatively, a core biopsy performed through the skin mandated the sacrifice of the surrounding skin (at least 5 cm margins) and any flap had to possess enough skin to replace what was removed during the tumour resection. An LD free flap would provide insufficient skin coverage without resorting to split skin grafting of the donor site, a usually undesirable proposition in chest wall reconstruction because of patient positioning post-operatively, subsequent poor skin graft take and poor donor site cosmesis. The TFL flap, although it does have many of the advantages of the ALT flap, is a short flap measuring 4–6 cm long,16 making it unsuitable. The DIEP free flap was excluded due to insufficient abdominal bulk (Fig. 5).

The ALT free flap has been shown to be reliable in complex chest wall reconstructions with or without radiotherapy.5 It was the best option in our case as it provided ample skin and soft tissue as well as minimal donor site morbidity.17,18 There is little functional deficit with this flap as the potentially damaged vastus lateralis functions as a synagonist with the other three knee extensors, leading to little functional loss. The ALT free flap has a large skin area which can be harvested even with the use of only a single major perforator.19,20 Additionally, the patient did not have to be turned during surgery as the ALT flap is harvested in the supine position with simultaneous resection of the tumour. It is based on large vessels ensuring easier microvascular surgery.

4. Conclusion

Herein, this case demonstrates the decision-making process involved in flap selection and further highlights the versatility of the ALT free flap. The challenges involved in chest wall reconstruction, the flap options available, and the possibilities for recipient vessels are outlined. The ALT free flap ensured adequate skin cover, subsequent bulk, provided an excellent operative position, produced little loss of donor site function, and provided an acceptable cosmetic result.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

Shahzad F. collected the literature review, wrote case report, discussion, selected figures, edited all sections throughout, prepared for submission; Wong K.Y. wrote case report, discussion, edited all sections throughout; Maraka J. wrote abstract, introduction, conclusion, edited all sections throughout; Di Candia M. contributed to discussion; Coonar A.S. and Malata C.M. edited the paper.

References

- 1.Souza F.F., De Angelo M., O’Regan K., Jagganathan J., Krajewski K., Ramaiya N. Malignant primary chest wall neoplasms: a pictorial review of imaging findings. Clinical Imaging. 2013;37(February (1)):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burt M. Primary malignant tumors of the chest wall. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Chest Surgery Clinics of North America. 1994;4(February (1)):137–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickey I.D., Rose P.S., Fuchs B., Wold L.E., Okuno S.H., Sim F.H. Dedifferentiated Chondrosarcoma: the role of chemotherapy with updated outcomes. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2004;86(November (11)):2412–2418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harwood A.R., Krajbich J.I., Fornasier V.L. Radiotherapy of chondrosarcoma of bone. Cancer. 1980;45(11):2769–2777. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800601)45:11<2769::aid-cncr2820451111>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Candia M., Wells F.C., Malata C.M. Anterolateral thigh free flap for complex composite central chest wall defect reconstruction with extrathoracic microvascular anastomoses. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;126(November (5)):1581–1588. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef679c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malata C.M., Moses M., Mickute Z., Di Candia M. Tips for successful microvascular abdominal flap breast reconstruction utilizing the “total rib preservation” technique for internal mammary vessel exposure. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2011;66(January (1)):36–42. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181e19daf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mansour K.A., Thourani V.H., Losken A., Reeves J.G., Miller J.I., Jr., Carlson G.W. Chest wall resections and reconstruction: a 25-year experience. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2002;73(June (6)):1720–1725. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03527-0. [discussion 1725-1726] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokote K., Osada H. Indication and method of chest wall reconstruction, Kyobu Geka. Japanese Journal of Thoracic Surgery. 1996;49(January (1)):38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coonar A.S., Qureshi N., Smith I., Wells F.C., Reisberg E., Wihlm J.-M. A novel titanium rib bridge system for chest wall reconstruction. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2009;87(May (5)):e46–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coonar A.S., Wihlm J.-M., Wells F.C., Qureshi N. Intermediate outcome and dynamic computerised tomography after chest wall reconstruction with the STRATOS titanium rib bridge system: video demonstration of preserved bucket-handle rib motion. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2011;12(January (1)):80–81. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.249615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beahm E.K., Chang D.W. Chest wall reconstruction and advanced disease. Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 2004;18(May (2)):117–129. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-829046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das S.K. The size of the human omentum and methods of lengthening it for transplantation. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1976;29(April (2)):170–174. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(76)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hultman C.S., Culbertson J.H., Jones G.E., Losken A., Kumar A.V., Carlson G.W. Thoracic reconstruction with the omentum: indications, complications, and results. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2001;46(March (3)):242–249. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurkiewicz M.J., Arnold P.G. The omentum: an account of its use in the reconstruction of the chest wall. Annals of Surgery. 1977;185(May (5)):548–554. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197705000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hameed A., Akhtar S., Naqvi A., Pervaiz Z. Reconstruction of complex chest wall defects by using polypropylene mesh and a pedicled latissimus dorsi flap: a 6-year experience. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2008;61(June (6)):628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauerbier M., Dittler S., Kreutzer C. Microsurgical chest wall reconstruction after oncologic resections. Seminars in Plastic Surgery. 2011;25(February (1)):60–69. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo Y.-R., Yeh M.-C., Shih H.-S., Chen C.-C., Lin P.-Y., Chiang Y.-C. Versatility of the anterolateral thigh flap with vascularized fascia lata for reconstruction of complex soft-tissue defects: clinical experience and functional assessment of the donor site. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;124(July (1)):171–180. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Candia M., Lie K., Kumiponjera D., Simcock J., Cormack G.C., Malata C.M. Versatility of the anterolateral thigh free flap: the four seasons flap. Eplasty. 2012;12:e21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimata Y., Uchiyama K., Ebihara S., Nakatsuka T., Harii K. Anatomic variations and technical problems of the anterolateral thigh flap: a report of 74 cases. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1998;102(October (5)):1517–1523. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199810000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo S., Raffoul W., Luo J., Luo L., Gao J., Chen L. Anterolateral thigh flap: a review of 168 cases. Microsurgery. 1999;19(5):232–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2752(1999)19:5<232::aid-micr5>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]