Abstract

Purpose

This study compared the clinical outcomes of T1-2N1 breast cancer patients with and without postmastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT). Risk factors for loco-regional recurrence (LRR) were identified in order to define a subgroup of patients who might benefit from PMRT.

Materials and Methods

Of 110 T1-2N1 breast cancer patients who underwent mastectomy from January 1994 through December 2009, 32 patients underwent PMRT and 78 patients did not. Treatment outcomes and risk factors for LRR were analyzed.

Results

The 5- and 10-year LRR rates were both 6.2% in the PMRT group, and 10.4% and 14.6% in the no-PMRT group (p=0.336). In addition, no significant differences in distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) or overall survival (OS) were observed between patients receiving and not receiving PMRT. In multivariate analysis, factors associated with higher LRR rates included grade 3 disease, extracapsular extension (ECE), and triple negative subtype. Patients who had one or more risk factors for LRR were defined as a high-risk patient group. In the high-risk group, both 5- and 10-year LRR rates for patients who underwent PMRT was 18.2%, and LRR rates of 21.4% at five years and 36.6% at 10 years were observed for patients who did not undergo PMRT (p=0.069).

Conclusion

PMRT in T1-2N1 breast cancer patients should be considered according to several prognostic factors in addition to T and N stage. Findings of our study indicated that PMRT did not improve LRR, DMFS, or OS in T1-2N1 breast cancer patients. However, in a subgroup of patients with grade 3 disease, ECE, or triple negative subtype, PMRT might be beneficial.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Radiotherapy, Mastectomy, Risk factor

Introduction

Randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses have shown that postmastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT) reduces the risk of loco-regional recurrence (LRR) and improves survival of high-risk breast cancer patients with metastasis in four or more axillary lymph nodes, or with tumors>5 cm in diameter [1-4]. However, PMRT for intermediate-risk breast cancer patients with metastasis in one to three axillary lymph nodes and with tumors≤5 cm is a highly controversial issue in breast cancer management [5-7].

Stage T1-2N1 breast cancer encompasses a heterogeneous population of tumors characterized by several prognostic clinical, pathological, and molecular factors [8,9]. Therefore, the use of PMRT for patients with T1-2N1 breast cancer could be guided by several prognostic factors rather than by T and N stage only. Some studies have reported that LRR and survival rates of T1-2N1 breast cancer patients treated with radical mastectomy are dependent on several prognostic factors other than T and N stage; these studies suggest that a subgroup of T1-2N1 breast cancer patients might be at particularly high risk of LRR and might benefit from PMRT [8,10,11]. However, no consensus can be drawn from these studies.

In this retrospective study, we compared the clinical outcomes of T1-2N1 breast cancer patients with and without PMRT. In addition, we also identified risk factors for LRR in order to define a subgroup of patients who might benefit from PMRT.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility criteria for this study were histological diagnosis of unilateral breast invasive ductal carcinoma, no other concomitant malignant disease, pathological tumor size≤5 cm and metastasis in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes, no tumor invasion of the skin, no metastasis in the ipsilateral internal mammary or supraclavicular lymph nodes or distant sites at the time of diagnosis, completion of modified radical mastectomy (MRM), no previous breast cancer, no neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and a follow-up period of more than two years after MRM. Tumor stage was based on the 7th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system. Histologic type and grading followed the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. At our institution, 110 breast cancer patients met the eligibility criteria from January 1994 through December 2009, and were enrolled in this study. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the retrospective review and analysis of patient data.

All patients underwent MRM. If the surgical margins were not free from disease, re-excision was performed in order to achieve disease-free surgical margins. All patients underwent axillary lymph node dissection. In some patients, axillary lymph node dissection was performed after sentinel lymph node biopsy. The extent of axillary lymph node dissection was usually confined to level I and II nodes. In cases of suspected level II or III nodal involvement, dissection was extended to level III.

After explaining the benefits and risks of PMRT to each patient, PMRT was administered at the discretion of the radiation oncologist, taking into account the patients' preference. There was no other factor that interfered with the decision regarding whether to use PMRT or not. Radiotherpy was delivered using a 6-MV photon beam to the chest wall. With a schedule of 2 Gy per fraction and five fractions weekly, the chest wall was treated with tangential fields to 46 Gy. All patients also received an electron boost to the tumor bed, with a median dose of 10 Gy (range, 10 to 16 Gy). Regional nodal irradiation was not implemented.

All patients underwent systemic chemotherapy. Decisions regarding the chemotherapy regimen were individualized by the medical oncologist. Regimens included doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide (AC); fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FAC); docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide (TAC); cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF); or cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and fluorouracil (CEF). All patients with positive estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) received adjuvant hormone therapy with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors.

All patient records included ER, PR, and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) status. Patients were classified according to receptor status: luminal (ER- or PR-positive), triple negative (ER-, PR-, HER2-negative), and HER2-positive (ER-, PR-negative, and HER2-positive). ER and PR status was determined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. Positive HER2 status was determined using either IHC 3+ staining or amplification on fluorescence in situ hybridization.

The primary endpoint of this study was LRR, and the secondary endpoints were distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) and overall survival (OS). LRR was defined as any tumor recurrence in the chest wall and/or ipsilateral axillary, supraclavicular, or internal mammary lymph nodes. Any recurrence outside these areas was defined as distant metastasis. All recurrences were diagnosed by either clinical or radiologic examination, as well as histologic confirmation, when possible.

To evaluate the impact of PMRT, patients were divided into two groups: 32 patients who underwent PMRT (PMRT group) and 78 patients who did not undergo PMRT (no-PMRT group). For identification of risk factors for LRR, the following parameters were included in the analysis: age, tumor location, histologic grade, T stage, number of positive axillary lymph nodes, number of dissected axillary lymph nodes, percentage of positive axillary lymph nodes, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), extracapsular extension (ECE), surgical resection margin, molecular subtype, regimen of chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy (trastuzumab).

The distribution patterns of clinical, pathological, and molecular factors of the PMRT group and no-PMRT group were compared by chi-square test. Actuarial recurrence and survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons among groups were performed using log-rank tests. The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used in performance of multivariate analysis. Elapsed time was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of recurrence recognition, death, or final follow-up visit. All tests were two-sided and p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

1. Patient characteristics

The median age of patients was 48.6 years (range, 32.4 to 75.5 years). All patients had invasive ductal carcinoma. The tumor histologic grade was 1 in 17 (15.5%) patients, 2 in 68 (61.8%) patients, and 3 in 25 (22.7%) patients. The median number of dissected axillary lymph nodes was 16 (range, 4 to 38) and the median percentage of positive axillary lymph nodes was 10.0% (range, 2.6 to 50.0%). The T stage was 1 in 43 patients (39.1%) and 2 in 67 patients (60.9%). All patients had surgical resection margins free from disease. The most commonly used adjuvant chemotherapy regimen was AC (doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 on day 1 and cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 on day 1, cycled every 21 days for four cycles). AC chemotherapy was given to 77 (70.0%) patients, CMF to 17 (15.5%) patients, FAC to six (5.5%) patients, CEF to five (4.5%) patients, and TAC to five (4.5%) patients. Among the patients, 86 (78.2%) patients showed positive immunoreactivity for ER or PR, and 34 (30.9%) were positive for HER2. Based on this result, 86 (78.2%), 14 (12.7%), and 10 (9.1%) patients were classified into the luminal, triple negative, and HER2-positive groups, respectively. The median follow-up duration for all patients was 7.0 years (range, 1.8 to 20.0 years).

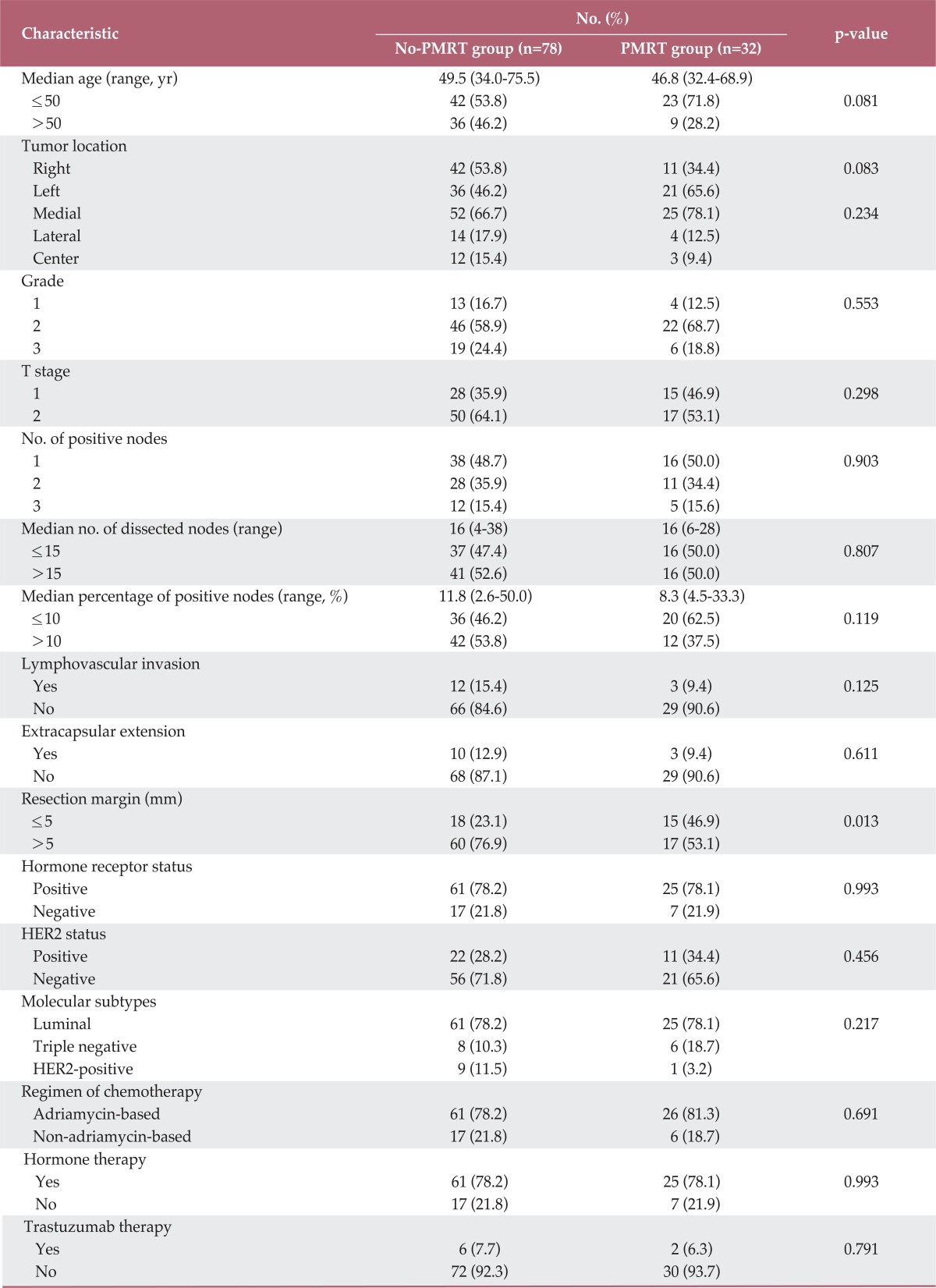

Among the patients, 32 (29.1%) underwent PMRT and 78 (70.9%) did not. A summary of patient and tumor characteristics from the PMRT and no-PMRT groups is shown in Table 1. Compared with the no-PMRT group, more patients in the PMRT group had surgical resection margins ≤5 mm. However, no significant difference in other characteristics was noted between the two groups.

Table 1.

Comparisons of characteristics of patients with and without PMRT

PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

2. Recurrence and survival

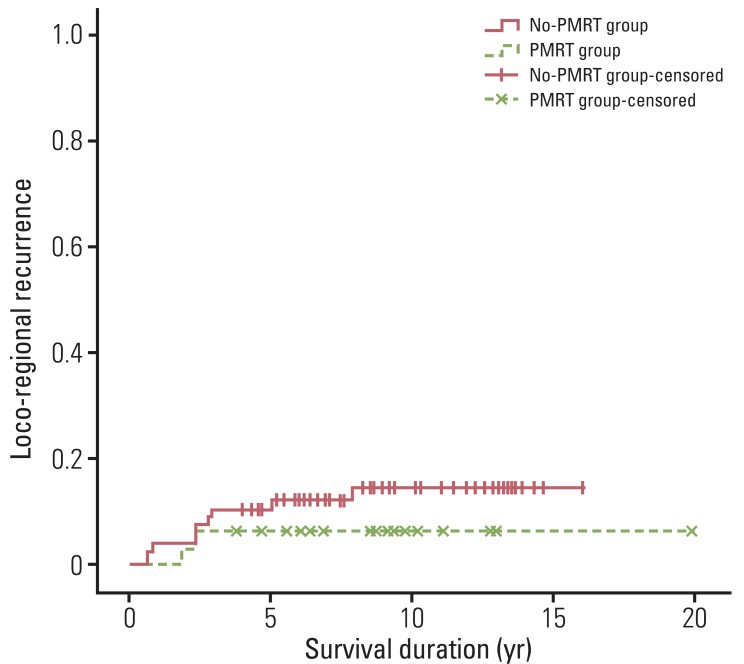

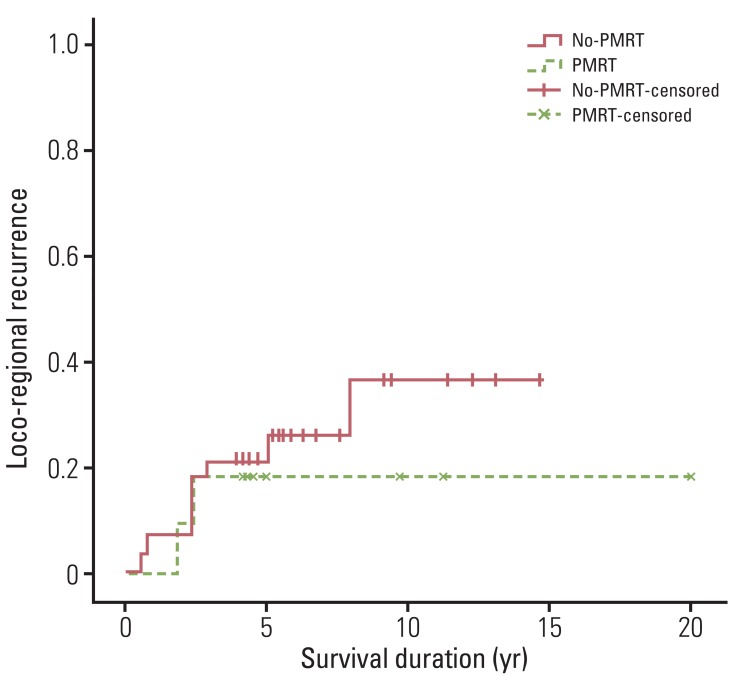

In the whole patients, 12 (10.9%) experienced LRR. Of these 12 patients, six experienced concomitant chest wall and regional lymph node recurrence, and the remaining six experienced regional lymph node recurrence. No isolated chest wall recurrence was found. In addition, of the 12 patients who developed LRR, 11 experienced concomitant distant metastasis. The median duration from surgery to LRR was 2.4 years (range, 0.6 to 7.9 years). Actuarial LRR rates were 9.2% at five years and 12.3% at 10 years. Two patients (6.2%) in the PMRT group and 10 patients (12.8%) in the no-PMRT group developed LRR. The 5- and 10-year actuarial LRR rates were both 6.2% in the PMRT group, and 10.4% at five years and 14.6% at 10 years in the no-PMRT group (p=0.336) (Fig. 1). No significant difference in terms of LRR was observed between patients receiving and not receiving PMRT.

Fig. 1.

Loco-regional recurrence for patients who received or did not receive postmastectomy radiotherapy (p=0.336). Differences between the two patient groups were not significant. PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy.

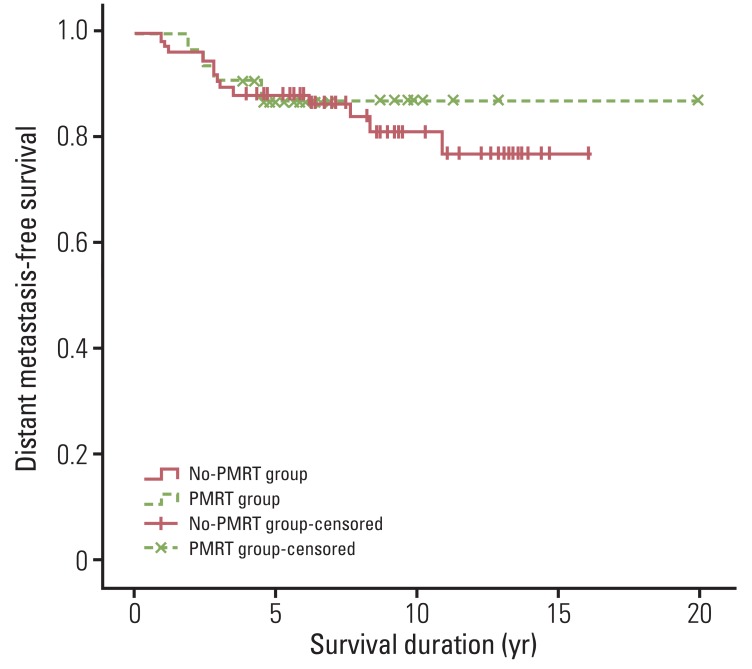

In the whole patients, 17 (15.5%) developed distant metastasis. The median duration from surgery to distant metastasis was 2.8 years (range, 0.9 to 8.4 years). DMFS rates were 88.8% at five years and 82.8% at 10 years. Four (12.5%) patients in the PMRT group and 13 (16.7%) patients in the no-PMRT group developed metastasis. The 5- and 10-year DMFS rates were both 87.0% in the PMRT group, and 88.4% at five years and 81.3% at 10 years in the no-PMRT group (p=0.681) (Fig. 2). No significant difference in terms of DMFS were observed between patients receiving or not receiving PMRT.

Fig. 2.

Distant metastasis-free survival for patients who received or did not receive postmastectomy radiotherapy (p=0.681). Differences between the two patient groups were not significant. PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy.

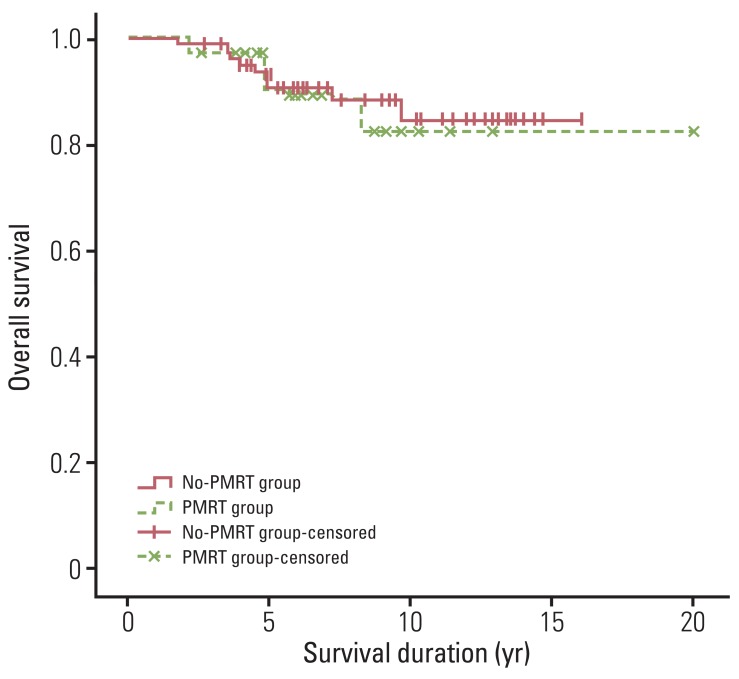

For all patients, the 5- and 10-year OS rates were 91.1% and 83.4%. During the follow-up period, 97 patients (88.2%) survived. OS rates were 93.1% at five years and 82.1% at 10 years in the PMRT group, and 90.3% at five years and 84.2% at 10 years in the no-PMRT group (p=0.824) (Fig. 3). No significant difference in terms of OS were observed between patients receiving or not receiving PMRT.

Fig. 3.

Overall survival for patients who received or did not receive postmastectomy radiotherapy (p=0.824). Differences between the two patient groups were not significant. PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy.

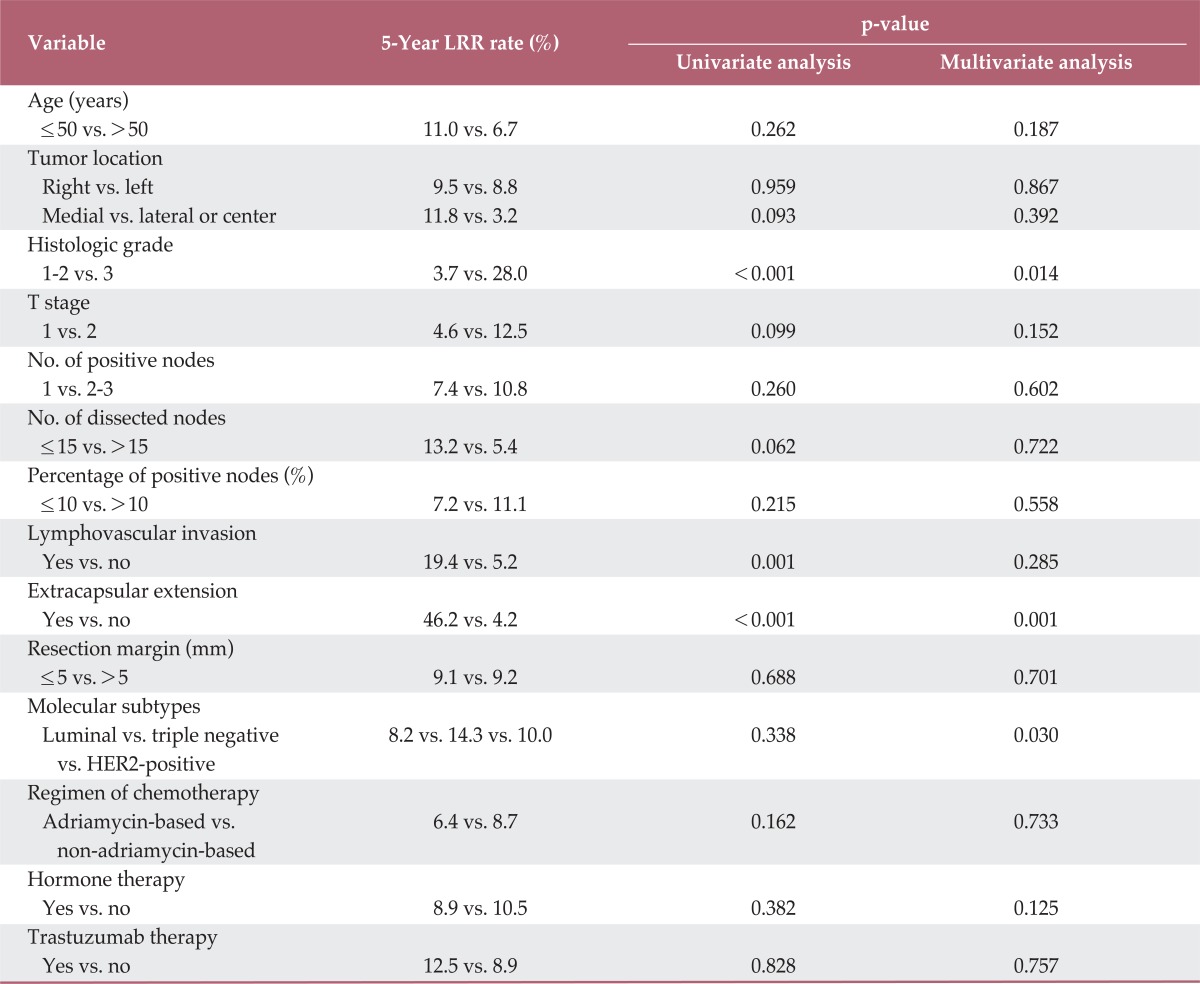

3. Risk factors for LRR

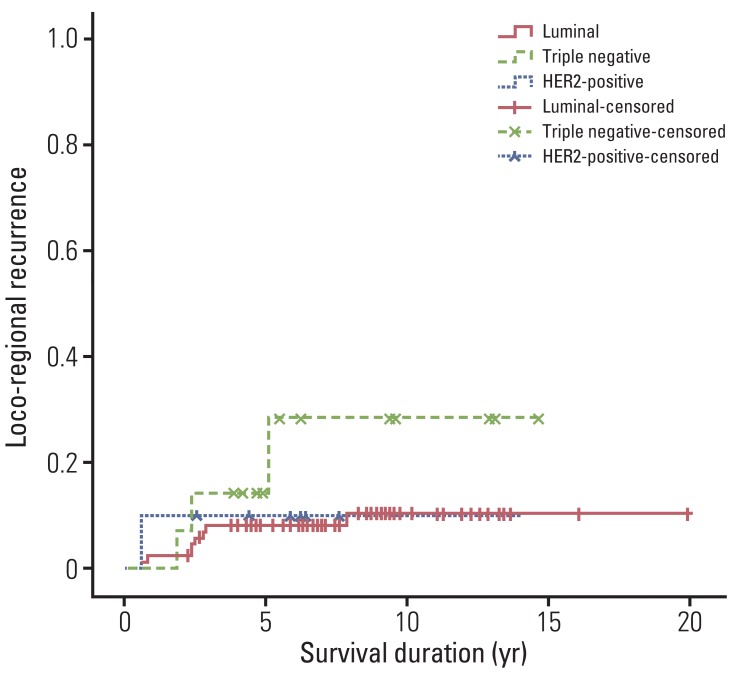

Risk factors for LRR were analyzed for all patients. In univariate analysis, factors associated with LRR were histologic grade (p<0.001), LVI (p=0.001), and ECE (p<0.001). In multivariate analysis, histologic grade (hazard ratio, 6.074; 95% confidence interval, 1.524 to 40.140; p=0.014) and ECE (hazard ratio, 11.756; 95% confidence interval, 2.956 to 53.359; p=0.001) remained significant factors for LRR, and molecular subtypes (hazard ratio, 4.365; 95% confidence interval, 8.365 to 14.760; p=0.030) were also found to show a significant association with LRR (Table 2, Fig. 4). Histologic grade 3 disease, positive ECE, and triple negative subtype showed an association with a higher LRR rate.

Table 2.

Analysis of risk factors for loco-regional recurrence (LRR)

HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

Fig. 4.

Loco-regional recurrence according to molecular subtypes. The 5- and 10-year actuarial loco-regional recurrence rates were 8.2% and 10.5% in the luminal subtype, 10% and 10% in the HER2-positive subtype, and 14.3% and 28.6% in the triple negative subtype. In multivariate analysis, patients who had the triple negative subtype showed a significantly higher loco-regional recurrence rate (hazard ratio, 4.365; 95% confidence interval, 8.365 to 14.760; p=0.030). HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2.

Of all patients, 39 had one or more risk factors for LRR that remained significant in multivariate analysis; these patients were defined as a high-risk patient group. In the high-risk group, 11 (28.2%) patients underwent PMRT and 28 (71.8%) did not. In the high-risk patient group, actuarial LRR rates for patients who underwent PMRT were 18.2% at both five and 10 years. Actuarial LRR rates for patients who did not undergo PMRT were 21.4% at five years and 36.6% at 10 years (p=0.069) (Fig. 5). Lower LRR rates were observed for patients who underwent PMRT, compared to those who did not undergo PMRT. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

Fig. 5.

Loco-regional recurrence for patients who received and did not receive postmastectomy radiotherapy in the high-risk patient group. Patients who received postmastectomy radiotherapy showed lower loco-regional recurrence rates, compared with patients who did not receive postmastectomy radiotherapy (p=0.069). However, differences between the two patient groups were not significant. PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy.

Discussion

The value of PMRT in women with metastasis in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes and with tumors≤5 cm remains uncertain. Several studies have reported on the value of PMRT in reducing LRR and mortality in intermediate-risk breast cancer patients, however, results have been inconsistent. Some studies have reported decreased LRR and survival benefit with PMRT [2,12-15], whereas others reported no benefit with PMRT [1,16-19]. In our study, we compared LRR, DMFS, and OS of T1-2N1 breast cancer patients with (32 patients) and without PMRT (78 patients). In the PMRT group, the 5- and 10-year actuarial LRR rates were both 6.2%, and, in the no-PMRT group, the rates were 10.4% and 14.6%, respectively. No significant difference was observed between these two patient groups (p=0.336). In addition, in terms of DMFS and OS, no significant differences were observed between patients receiving and not receiving PMRT. On the other hand, in the subgroup analysis of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82b&c randomized trials, Overgaard et al. [13] reported that PMRT significantly reduced the 15-year LRR rate (27% in the no-PMRT group vs. 4% in the PMRT group, p<0.001) and improved 15-year OS rate (48% in the no-PMRT group vs. 57% in the PMRT group, p=0.03). Also, in the British Columbia randomized trial, Ragaz et al. [12] reported that PMRT significantly improved LRR-free survival, disease-free survival, and OS in breast cancer patients with metastasis in 1-3 axillary lymph nodes. A major difference between our study and those randomized trials is the PMRT field. In Danish and British Columbia trials, the chest wall and regional lymph nodes (axillary nodes, supraclavicular nodes, and internal mammary nodes) were included in the PMRT field. However, in our study, only the chest wall was treated and regional nodal irradiation was not implemented. In addition, in our study, all patients had breast cancer with tumor size≤5 cm, however, some breast cancer patients with tumor size>5 cm were included in the subgroup analysis of Danish trials (4.7%) and the British Columbia trial (15.6%).

The Medical Research Council Selective Use of Post-Mastectomy Radiotherapy (SUPREMO) trial for determination of the role of PMRT in women with intermediate-risk breast cancer following mastectomy is ongoing [20]. This randomized, phase III trial is designed for investigation of whether post-mastectomy chest wall irradiation can reduce LRR and improve survival in patients with pT1N1M0 or pT2N0-1M0 disease. This trial might provide more information on the role of PMRT in this patient group. However, because several clinical and pathological factors might affect prognosis in patients with intermediate-risk breast cancer, it is a crude way to determine potential indications for PMRT using only T and N stage [11,13]. In addition, the available knowledge regarding the prognostic value of molecular factors in selection of breast cancer patients for adjuvant therapy has recently increased [21,22]. Therefore, strategies that use clinical, pathological, and molecular factors other than T and N stage in distinguishing subgroups of intermediate-risk breast cancer patients who might be at particularly high risk of LRR and who might benefit from PMRT should be investigated.

Some studies have reported on subgroups of intermediate-risk breast cancer patients who might benefit from PMRT. In a retrospective analysis that included 821 T1-2N1 breast cancer patients, Truong et al. [11] reported that, in patients aged <45 years, a subgroup with >25% positive axillary nodes were recommended for PMRT. In patients aged≥45 years, a subgroup with >25% positive axillary nodes, medial tumor location, and ER-negative disease were also recommended for PMRT. Trovo et al. [10], who conducted a retrospective review of 150 stage I-II breast cancer patients treated with modified radical mastectomy, reported that LVI, grade 3 disease, ER-negative tumors, and premenopausal status were significant risk factors for LRR. In their study, patients with three or more risk factors had an LRR rate of >20% at five years, and PMRT was recommended. In retrospective analysis, which included 575 T1-2N1 breast cancer patients, Duraker et al. [23] reported that PMRT was beneficial in reducing LRR risk in T1N1 patients with >25% positive axillary nodes and in T2N1 patients with >8% positive axillary nodes. The authors proposed that PMRT could be omitted in patients with a percentage of positive axillary nodes equal to or less than these cut-off ratios. In our study, in multivariate analysis, grade 3 disease, positive ECE, and triple negative subtype were significant risk factors for LRR. We defined patients with one or more risk factors as a high-risk patient group. In this high-risk patient group, in patients who underwent PMRT, 5- and 10-year actuarial LRR rates were both 18.2%, and those for patients who did not undergo PMRT were 21.4% and 36.6% (p=0.069) (Fig. 5). Due to small sample size and short follow-up duration, no significant difference was observed between these two patient groups; however, PMRT appeared to reduce LRR in the later period. Therefore, we propose that PMRT would be necessary in patients with grade 3 disease, ECE, or triple negative tumors. In order to confirm the subgroup of patients who might benefit from PMRT in T1-2N1 breast cancer, prospective multicenter trials with large sample sizes and longer follow-up duration will be required.

Recently, there has been accumulating evidence indicating that molecular factors will allow for prediction of the response to adjuvant radiotherapy in breast cancer patients. Several studies have reported a significant association of HER2-positive and triple negative tumors with worse recurrence rates and decreased survival [9,24,25]. In our study, patients were classified into luminal, triple negative, and HER2-positive groups according to receptor status. The 5- and 10-year actuarial LRR rates were 8.2% and 10.5% in luminal subtypes, 10% and 10% in HER2-positive subtypes, and 14.3% and 28.6% in triple negative subtypes. Multivariate analysis showed significantly higher LRR rates for patients with triple negative tumors. In the recent era of biologic tumor classification, breast cancer molecular subtypes might provide better guidance with regard to which patients are likely to benefit from PMRT. This is the first study to identify molecular subtypes that can guide treatment strategies for PMRT in T1-2N1 breast cancer patients. In order to confirm the findings of our study, a prospective randomized trial for evaluation of molecular markers must be conducted.

Our study had some limitations. First, the follow-up durations were not sufficiently long in some cases, and, consequently, this study may have underestimated recurrence rates. Second, the retrospective design might have inherent bias. For example, adjuvant chemotherapy and PMRT were provided according to the attending physicians' discretion rather than based on a predetermined protocol. Thus, adjuvant chemotherapy regimens varied widely. Third, the small sample size could explain why statistical significance was not reached for some evaluated factors. However, many prospective trials with large samples enroll patients who might have inherently different characteristics than patients in the community. Because this study enrolled a community-based population, our results might offer valuable information regarding clinical outcomes in patients encountered in community practice.

Conclusion

PMRT in T1-2N1 breast cancer patients should be considered according to prognostic factors such as clinical, pathological, and molecular factors. Findings of our study showed that PMRT did not improve LRR, DMFS, or OS in T1-2N1 breast cancer patients. However, in a subgroup of patients with grade 3 disease, ECE, or triple negative tumors, PMRT might be beneficial.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest relevant to this article was not reported.

References

- 1.Ragaz J, Jackson SM, Le N, Plenderleith IH, Spinelli JJ, Basco VE, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:956–962. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overgaard M, Hansen PS, Overgaard J, Rose C, Andersson M, Bach F, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82b Trial. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:949–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Overgaard M, Jensen MB, Overgaard J, Hansen PS, Rose C, Andersson M, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk postmenopausal breast-cancer patients given adjuvant tamoxifen: Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82c randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1641–1648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelan TJ, Julian J, Wright J, Jadad AR, Levine ML. Does locoregional radiation therapy improve survival in breast cancer? A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1220–1229. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Recht A, Edge SB, Solin LJ, Robinson DS, Estabrook A, Fine RE, et al. Postmastectomy radiotherapy: clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1539–1569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Truong PT, Olivotto IA, Whelan TJ, Levine M Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: 16. Locoregional post-mastectomy radiotherapy. CMAJ. 2004;170:1263–1273. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor ME, Haffty BG, Rabinovitch R, Arthur DW, Halberg FE, Strom EA, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria on postmastectomy radiotherapy expert panel on radiation oncology-breast. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallgren A, Bonetti M, Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Holmberg SB, et al. Risk factors for locoregional recurrence among breast cancer patients: results from International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I through VII. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1205–1213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, John-sen H, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trovo M, Durofil E, Polesel J, Roncadin M, Perin T, Mileto M, et al. Locoregional failure in early-stage breast cancer patients treated with radical mastectomy and adjuvant systemic therapy: which patients benefit from postmastectomy irradiation? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e153–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Truong PT, Olivotto IA, Kader HA, Panades M, Speers CH, Berthelet E. Selecting breast cancer patients with T1-T2 tumors and one to three positive axillary nodes at high postmastectomy locoregional recurrence risk for adjuvant radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1337–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ragaz J, Olivotto IA, Spinelli JJ, Phillips N, Jackson SM, Wilson KS, et al. Locoregional radiation therapy in patients with high-risk breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: 20-year results of the British Columbia randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:116–126. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Overgaard M, Nielsen HM, Overgaard J. Is the benefit of postmastectomy irradiation limited to patients with four or more positive nodes, as recommended in international consensus reports? A subgroup analysis of the DBCG 82 b&c randomized trials. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marks LB, Zeng J, Prosnitz LR. One to three versus four or more positive nodes and postmastectomy radiotherapy: time to end the debate. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2075–2077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosar R, Uzal C, Tokatli F, Denizli B, Saynak M, Turan N, et al. Postmastectomy irradiation in breast in breast cancer patients with T1-2 and 1-3 positive axillary lymph nodes: is there a role for radiation therapy? Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith BD, Smith GL, Haffty BG. Postmastectomy radiation and mortality in women with T1-2 node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1409–1419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowble B. Postmastectomy radiation in patients with one to three positive axillary nodes receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: an unresolved issue. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1999;9:230–240. doi: 10.1016/s1053-4296(99)80014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernando IN. The role of radiotherapy in patients undergoing mastectomy for carcinoma of the breast. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2000;12:158–165. doi: 10.1053/clon.2000.9143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce LJ. Treatment guidelines and techniques in delivery of postmastectomy radiotherapy in management of operable breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;30:117–124. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunkler IH, Canney P, van Tienhoven G, Russell NS MRC/EORTC (BIG 2-04) SUPREMO Trial Management Group. Elucidating the role of chest wall irradiation in 'intermediate-risk' breast cancer: the MRC/EORTC SUPREMO trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sotiriou C, Wirapati P, Loi S, Harris A, Fox S, Smeds J, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:262–272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreike B, Halfwerk H, Kristel P, Glas A, Peterse H, Bartelink H, et al. Gene expression profiles of primary breast carcinomas from patients at high risk for local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5705–5712. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duraker N, Demir D, Bati B, Yilmaz BD, Bati Y, Caynak ZC, et al. Survival benefit of post-mastectomy radiotherapy in breast carcinoma patients with T1-2 tumor and 1-3 axillary lymph node(s) metastasis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:601–608. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sotiriou C, Neo SY, McShane LM, Korn EL, Long PM, Jazaeri A, et al. Breast cancer classification and prognosis based on gene expression profiles from a population-based study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10393–10398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1732912100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen PL, Taghian AG, Katz MS, Niemierko A, Abi Raad RF, Boon WL, et al. Breast cancer subtype approximated by estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER-2 is associated with local and distant recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2373–2378. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]