Abstract

Objective

To examine long-term associations between change in alcohol-consumption status and cessation of alcohol use, and fibrinogen levels in a large, young, biracial cohort.

Design

Analysis of covariance models were used to analyse participants within the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) cohort who had fibrinogen and alcohol use data at year 7 (1992–1993; ages 25–37) and year 20 examinations.

Setting

4 urban US cities.

Patients

2520 men and women within the CARDIA cohort.

Main outcome measures

13-year changes in alcohol use related to changes in fibrinogen.

Results

Over 13 years, mean fibrinogen increased by 71 vs 70 mg/dL (p=NS) in black men (BM) versus white men (WM), and 78 vs 68 mg/dL (p<0.05) in black women (BW) versus white women (WW), respectively. Compared with never-drinkers, there were smaller longitudinal increases in fibrinogen for BM, BW and WW (but a larger increase in WM) who became or stayed drinkers, after multivariable adjustment. For BM, WM and WW, fibrinogen increased the most among persons who quit drinking over 13 years (p<0.001 for WM (fibrinogen increase=86.5 (7.1) (mean (SE))), compared with never-drinkers (fibrinogen increase=53.1 (5.4)).

Conclusions

In this young cohort, compared with the participants who never drank, those who became/stayed drinkers had smaller increases, while those who quit drinking had the highest increase in fibrinogen over 13 years of follow-up. The results provide a novel insight into the mechanism for the established protective effect of moderate alcohol intake on cardiovascular disease outcomes.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Preventive Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

To gain some insight into the established protective effect of moderate alcohol intake on cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes.

To determine the 13-year longitudinal associations between change in alcohol consumption status and cessation of alcohol use.

To determine variations in fibrinogen levels among a biracial group of young adult participants from the large Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) cohort.

Key messages

In this young cohort of black and white men and women with minimal baseline confounding factors, compared with the participants who never drank, those who became/stayed drinkers had smaller increases, while those who quit drinking had the highest increase in fibrinogen over 13 years of follow-up.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strength of our study lies in the longitudinal nature of our assessment with a relatively long follow-up period of 13 years, the large size of the study, the youth of the study participants (with few residual confounding factors at baseline) and the sex/racial make-up of the cohort. Our study findings are particularly novel in that in examining the associations between alcohol consumption and fibrinogen changes in a large population of black and white men and women, we consolidated many years of alcohol use into each of the alcohol status categories, while examining their effects on variations in fibrinogen levels within each group. Thus, our study provides an important addition to the literature with respect to the long-term relationship between alcohol use and fibrinogen as a marker of CVD.

Limitations include the relatively wide range of alcohol intake levels included among persons classified as drinkers. Nonetheless, our findings remained the same after dropping at-risk levels. We caution that this analysis does not specifically measure all other potential conditions associated with elevated fibrinogen levels, although on average the CARDIA cohort was recruited to be a relatively healthy sample at baseline. Furthermore, some participants were excluded from our analysis due to missing data or loss to follow-up. Findings were unchanged when imputation analysis was performed in a prior study by our group which examined associations between fibrinogen and CV risk factors in the same population.

Introduction

Numerous studies have linked moderate alcohol consumption with lower cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality.1–3 Conversely, fibrinogen—the precursor of fibrin, a cofactor for platelet aggregation, and a major determinant of blood viscosity and atherogenesis—directly and independently correlates with CVD as well as CVD risk factors.4 5 Many cross-sectional and prospective studies have found lower fibrinogen levels among alcohol consumers.4 6 Accordingly, fibrinogen levels decline with lifestyle interventions such as smoking cessation, exercise and moderate alcohol consumption.4 5 7

Alcohol is suggested to be causally related to a lower risk of CVD through changes in lipids and haemostatic/inflammatory factors, such as fibrinogen.1 3 6 8 9 This observed relationship between alcohol consumption and CVD follows a non-linear J-shaped curve, thus suggesting hazards to excessive alcohol consumption and to complete abstinence.1 6 10 In addition, there are some data in the literature linking a moderate increase in alcohol-consumption status to a decreased risk of CVD and diabetes,11 12 and better health among moderate drinkers compared with alcohol quitters after acute myocardial infarction (MI).13 Fibrinogen, lipids and other inflammatory and haemostatic factors implicated in CVD also appear to follow a J-shaped distribution in their relationship with alcohol consumption.6 9 14 Nonetheless, there are very sparse data describing the relationship between long-term change in alcohol-consumption status and any of these factors.10 Even less is known about the influence of cessation of alcohol use on these factors.

We report 13-year longitudinal associations between change in alcohol-consumption status and cessation of alcohol use and variations in fibrinogen levels among a biracial group of young adult participants from the large Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) cohort. Findings from this study of young adults might provide some insight into the established protective effect of moderate alcohol intake on CVD outcomes. We stratified our findings by sex and race.

Methods

Study participants

CARDIA is an ongoing multicentre prospective cohort study designed to investigate the evolution of CVD risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis in young adults. Inclusion/exclusion criteria, baseline characteristics and details of the study design have been described elsewhere.15 Briefly, in 1985–1986, the cohort enrolled 5115 black and white adults aged 18–30 years, recruited from four urban US areas (Birmingham, Alabama; Oakland, California; Chicago, Illinois and Minneapolis, Minnesota). Participants were balanced by age, sex, race and education at baseline. The institutional review boards at all the study sites approved the study protocol and obtained written informed consent from all study participants.

Our study included 2971 non-pregnant CARDIA women and men with fibrinogen measurements at examination years 7 (Y7—our study baseline) and 20 (Y20—termed follow-up in our study). Persons with coronary heart disease (CHD; n=6), persons with non-fasting glucose and missing data for triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol (n=312), persons with missing changes in alcohol-use status (n=28) and persons missing other covariates of interest (n=105) were excluded. The final cohort for analysis included 2520 non-pregnant women and men.

Covariates ascertainment

Blood pressure, cholesterol, height, weight, waist circumference, smoking and physical activity were measured in each examination using a standardised protocol.16 Interviewer-administered questionnaires were used to obtain information on age, race, socioeconomic measures, diabetes history, cigarette-smoking status, family history and medication used.15

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol use was assessed via an interviewer-administered questionnaire for different types of alcoholic beverages (wine, beer and liquor). Current alcohol drinkers were defined as individuals who drank any alcoholic beverages in the past year. Otherwise, individuals were classified as non-drinkers.

Change in alcohol-consumption status over 13 years was categorised according to dichotomised alcohol consumption groupings (non-drinker, current drinker) at Y7 and Y20 and four mutually exclusive groups to reflect long-term changes in alcohol-consumption status were defined: continued non-drinker (individuals persistently in the ‘non-drinker’ category at both Y7 and Y20, referent), became drinker (individuals in the ‘non-drinker’ category at Y7 but in the ‘current’ category at Y20), stayed drinker (individuals persistently in the ‘current’ category at both Y7 and Y20) and quit drinking (individuals in the ‘current’ category at Y7 but in the ‘non-drinker’ category in Y20).

We used categorised change in alcohol use rather than a numeric value of change in alcohol consumption over time for two reasons: first, as per the US Department of Health and Human Services, alcohol use was categorised as none, moderate and at-risk based on established thresholds; second, the distribution of changes in alcohol use (as numeric values) over time in the general population is skewed and not normally distributed. As such, changes in alcohol use cannot be analysed using parametric statistical tests.

Fibrinogen measurement

Each participant had blood samples drawn after an 8 h fast, between 7:00 and 10:00. Within 10 min of collection, repeated inversion was used to mix the samples, which were then spun in a refrigerated centrifuge at 4°C for 20 min. Within 90 min, the samples were stored at −70°C for a maximum of 4 months. Fibrinogen was measured in Y7 and Y20 plasma samples as previously described, using the BNII Nephelometer 100 Analyzer, Dade Behring, Deerfield, Illinois, USA.17 The assay was calibrated with a reference plasma of known fibrinogen concentration, and the intra-assay and interassay coefficient of variation were 2.7% and 2.6% at Y7 and 3.1% and 4.2% at Y20, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed by sex/race strata, with two-sided p<0.05 considered as statistically significant. Baseline and follow-up alcohol-consumption status and pairwise differences in covariates by sex/race groups were estimated using t tests, χ² tests and Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate. Analysis of covariance models were used to relate changes in status of alcohol use (predictor variable) to changes in mean fibrinogen levels (outcome variable) over 13 years, with adjustments for covariates. Model 1 was adjusted for baseline (Y7) age and fibrinogen level. Model 2 was adjusted for baseline age, fibrinogen level, family history of heart disease, education, physical activity and traditional CVD risk factors (including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, obesity and number of cigarettes/day); 13-year change in physical activity score, as well as follow-up statuses of traditional CVD risk factors as listed. We stratified our findings by sex/race groups because the CARDIA study group was designed to be balanced by age, sex, race and education when recruited at baseline. Analyses were conducted with SAS statistical software V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics for this sample have been described previously. In brief, we included 2520 participants (55% women, 43% black) with a mean age of 32.2 years (range 25–37 years) at study baseline. Online supplementary table S1 shows summary statistics for key variables at baseline and follow-up. Over 13 years, mean fibrinogen increased by 71 vs 70 mg/dL (p=NS) in black men compared with white men and 78 vs 68 mg/dL (p<0.05) in black women compared with white women, respectively.

The prevalence of alcohol use at baseline and year 20 was higher among white men and women relative to black men and women (both p<0.01). Compared with the study baseline, the prevalence of alcohol use at Y20 was higher among white men and women, but lower among black men and women by follow-up 13 years later (see online supplementary table S1).

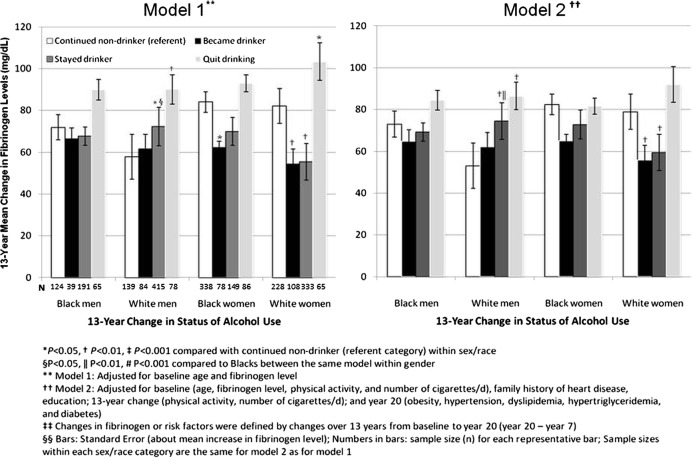

Multivariable changes in fibrinogen levels in relation to changes in alcohol-consumption status

The alcohol-drinking status for most participants remained stable through the years (figure 1). More individuals remained non-drinkers (N=829) or stayed drinkers (N=1088), while fewer persons changed their drinking status through the years (N=309 for those who became drinkers, and 294 for those who quit drinking). After adjustments for various covariates (models 1 and 2 in figure 1), changes in alcohol-consumption status from study baseline to follow-up were inversely associated with changes in mean fibrinogen levels during the same time period. As such, becoming or staying a drinker (for both models) was associated with a smaller mean increase in 13-year follow-up fibrinogen levels compared with never-drinkers. This held true among black men and women, but was particularly strongest in white women (all p<0.001 for both models among white women). An exception was white men, whose fibrinogen increased more in those who became or stayed drinkers and increased the least among those who never drank alcohol over the 13 years.

Figure 1.

Adjusted mean increase in fibrinogen in relation to changes in alcohol use over 13 years by sex race: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study, 1992–2006.

For all alcohol-use patterns studied, quitting alcohol use was associated with the largest mean increase in fibrinogen by the 13-year follow-up (p<0.001 for white men, compared with never-drinkers). For black women, change in fibrinogen was essentially the same for those who quit drinking relative to those who never drank alcohol over the years.

Our findings remained the same when at-risk drinkers—defined as ≥3 drinks on the day of maximum intake in the past month or ≥8 drinks/week for women; and ≥4 drinks on the day they drank the most in the past month or ≥15 drinks/week for men18—were excluded from the analysis (data not shown). Our findings also did not change when follow-up CVD risk factors were excluded from model 2. Furthermore, the change in fibrinogen levels among participants who became or stayed drinkers through the years remained significantly lower compared with the change among those who quit drinking—used as the referent group in this case (data not shown).

The health characteristics of the participants by alcohol consumption category are shown in table 1. The unadjusted data show that, at baseline (Y7), the continued non-drinker population and those who quit drinking had a significantly higher prevalence of high blood pressure—which increased and remained significant by Y20—compared with those who became or stayed drinkers. Those who quit drinking had a significantly lower prevalence of diabetes at baseline, which increased (but not significantly) by follow-up at Y20. Interestingly, other assessed characteristics (including liver disease, hepatitis, digestive disease and cancer) were not significantly different among the alcohol-consumption groups.

Table 1.

Years 7 and 20 health characteristics of participants by changes in alcohol consumption status

| Comorbidities* | Year 7 |

Year 20 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continued non-drinker | Became drinker | Stayed drinker | Quit drinking | p Value† | Continued non-drinker | Became drinker | Stayed drinker | Quit drinking | p Value† | |

| High blood pressure (%) | 11.0 | 5.8 | 7.7 | 10.5 | 0.012 | 27.1 | 15.2 | 19.3 | 28.9 | <0.001 |

| Stroke or TIA (%) | – | – | – | – | – | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.318 |

| Diabetes (%) | 4.7 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.001 | 9.2 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 9.5 | 0.007 |

| Liver disease (%) | 1.2 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.281 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 0.161 |

| Hepatitis (%) | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.165 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 0.421 |

| Digestive disease (%) | 5.5 | 7.1 | 4.1 | 6.5 | 0.116 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 9.5 | 0.554 |

| Cancer (%) | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.591 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 0.421 |

| Mental disorder (%) | 4.1 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 0.500 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 0.152 |

*Participants were asked if a physician had previously diagnosed them with the chronic conditions.

†Overall p values calculated using χ2 test.

TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Discussion

We directly examined associations between changes in long-term alcohol consumption and alcohol cessation and changes in fibrinogen levels in a large, young population of black and white men and women. Overall, we observed that fibrinogen rose less in persons who became drinkers or remained drinkers and, interestingly, increased more in persons who quit drinking. This pattern held for three of the sex/race groups in our study, even after adjusting for study baseline age, fibrinogen levels, family history of heart disease, education, physical activity and traditional CVD risk factors; 13-year changes in physical activity, as well as follow-up statuses of traditional CVD risk factors (as detailed in model 2 in figure 1). However, for white men, continued non-drinker status was not associated with a greater rise in fibrinogen.

Fibrinogen is mainly synthesised in the liver, and is a soluble glycoprotein which regulates plasma viscosity, induces reversible red cell aggregation and is the most abundant component of thrombi.16 19 In addition, fibrinogen increases platelet reactivity by binding glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor on the platelet surface.16 Fibrin is an important component of atherogenesis and atheroma growth; additionally, it provides a scaffold for smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, which attracts leucocytes, affecting endothelial permeability and vascular tone.16 20 Fibrinogen binds LDL cholesterol and lipids, and is consequently involved in the formation of the atherosclerotic lipid core.16 Moderate alcohol consumption has beneficial effects on atherosclerosis, attributed to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects and to its actions on vascular function. These effects are thought to be mediated by polyphenols.21

Fibrinogen has shown significant independent positive associations with CHD, CVD and their risk factors—including age, smoking history, physical activity, body mass index, total and LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure,4 5 while the opposite is true for alcohol consumption. In fact, alcohol consumed in moderate quantities is inversely correlated with risk factors and mortality for CHD and CVD (including stroke).2 3

We found that, overall, persons who continued to use and those who initiated alcohol consumption during the 13 years of follow-up had smaller changes in fibrinogen levels relative to those who never consumed alcohol. Several prospective and cross-sectional studies have shown significant inverse associations between alcohol consumption and fibrinogen levels.4 6 Indeed, moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with platelet inhibition similar to that observed with aspirin use.22 However, while some studies have examined the relationship between very short-term alcohol intake and changes in fibrinogen levels in a limited number of patients,8 23 very sparse data exist that have examined associations between long-term alcohol intake status and variations in fibrinogen levels in a large population of participants. In addition, the youth of our study population contributes significant information to existing literature because it evaluates alcohol effects on CVD risk, with minimal confounding. Our study suggests that moderate alcohol consumption can still modulate CVD risk even in young adults, an important finding which agrees with benefits to CVD risk modulation beginning early in life. It also suggests fibrinogen as a possible mediator of this process.

An interesting and important observation from our study is that in all sex/race groups, among those who quit drinking over the years, fibrinogen levels increased to values higher than that observed for never-drinkers and the rest of the drinking groups. Indeed, several studies have observed a J-shaped curve in the relationship between alcohol and CVD such that lower alcohol consumption was associated with reduced CVD, while the reverse was true for higher quantities of alcohol consumed.1 2 24 A study of patients immediately post-MI showed better health among patients with moderately increased alcohol intake relative to quitters.13 Nonetheless, to our knowledge, no study has investigated the effects of quitting alcohol consumption on inflammatory/thrombotic markers or CVD risk factors in general. Fibrinogen is a marker of platelet aggregation and vascular thrombosis. In acute, short-term human and experimental models, discontinuation of alcohol use has been associated with rebound platelet aggregation.14 22 25

Unlike the rest of the sex/race groups, white men who became drinkers and those who stayed drinkers through the years had larger increases in fibrinogen levels relative to never-drinkers. Prospective and cross-sectional studies have shown the observed J-curve pattern to beneficial effects of alcohol in whites, but not in blacks; and moderate alcohol drinking has been shown to be associated with reduced CVD mortality in whites, but not blacks.26 27 This finding in our study is unexplained and requires further exploration. The strength of our study lies in the longitudinal nature of our assessment with a relatively long follow-up period of 13 years, the large size of the study, the youth of the study participants (with few residual confounding factors at baseline) and the sex/racial make-up of the cohort. Our study findings are particularly novel in that in examining the associations between alcohol consumption and fibrinogen changes in a large population of black and white men and women, we consolidated many years of alcohol use into each of the alcohol status categories, while examining their effects on variations in fibrinogen levels within each group. Thus, our study provides an important addition to the literature with respect to the long-term relationship between alcohol use and fibrinogen as a marker of CVD.

Limitations include the relatively wide range of alcohol-intake levels included among persons classified as drinkers. Nonetheless, our findings remained the same after dropping at-risk levels. We caution that this analysis does not specifically measure all other potential conditions associated with elevated fibrinogen levels, although on average the CARDIA cohort was recruited to be a relatively healthy sample at baseline. Furthermore, some participants were excluded from our analysis due to missing data or loss to follow-up. Findings were unchanged when imputation analysis was performed in a prior study by our group which examined associations between fibrinogen and CV risk factors in the same population.

Conclusion

In this young cohort of black and white men and women with minimal baseline confounding factors, the increase in fibrinogen was smaller overall among drinkers and larger among those who quit drinking, compared with those who remained alcohol-free for 13 years. These results need to be confirmed in other populations. Our study provides insight into the mechanism and possible role of fibrinogen on the established protective effect of moderate alcohol intake on CVD outcomes, and concurs with benefits to CVD risk modulation beginning early in life. Translation of our findings to associations with CHD/CVD events would be of great interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript, except as required of all studies supported by NHLBI. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: TMO is the guarantor and was responsible for the overall content of the current article. OK was interested in cardiovascular risk factors and associations with markers of inflammation. This author worked closely with the lead author to shape and write the manuscript. CC performed all analysis for the current manuscript and also contributed significantly to the statistical language and writing of the statistical analysis section of the manuscript. PS contributed significantly to the epidemiological language, as well as statistical analysis (from an epidemiology perspective), employed in the manuscript. DG contributed significantly to the proposal development, as well as the writing of the manuscript. KL oversaw the proposal development, data analysis and writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grant HL-43758 and contracts NO1-HC-48049 and NO1-HC-95095 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and grant AG032136 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: DG was the fibrinogen expert who was awarded the grant for fibrinogen measurement in the CARDIA cohort.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Costanzo S, Di Castelnuovo A, Donati MB, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1339–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, et al. Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2437–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brien SE, Ronksley PE, Turner BJ, et al. Effect of alcohol consumption on biological markers associated with risk of coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. BMJ 2011;342:d636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaptoge S, White IR, Thompson SG, et al. Fibrinogen Studies C Associations of plasma fibrinogen levels with established cardiovascular disease risk factors, inflammatory markers, and other characteristics: individual participant meta-analysis of 154,211 adults in 31 prospective studies: the fibrinogen studies collaboration. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:867–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danesh J, Lewington S, Thompson SG, et al. Fibrinogen Studies C Plasma fibrinogen level and the risk of major cardiovascular diseases and nonvascular mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis.[Erratum appears in JAMA. 2005 Dec 14;294:2848]. JAMA 2005;294:1799–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimm EB, Williams P, Fosher K, et al. Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ 1999;319:1523–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chainani-Wu N, Weidner G, Purnell DM, et al. Changes in emerging cardiac biomarkers after an intensive lifestyle intervention. Am J Cardiol 2011;108:498–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen AS, Marckmann P, Dragsted LO, et al. Effect of red wine and red grape extract on blood lipids, haemostatic factors, and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:449–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imhof A, Woodward M, Doering A, et al. Overall alcohol intake, beer, wine, and systemic markers of inflammation in western Europe: results from three MONICA samples (Augsburg, Glasgow, Lille). Eur Heart J 2004;25:2092–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kloner RA, Rezkalla SH. To drink or not to drink? That is the question. Circulation 2007;116:1306–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sesso HD, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, et al. Seven-year changes in alcohol consumption and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease in men. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2605–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joosten MM, Chiuve SE, Mukamal KJ, et al. Changes in alcohol consumption and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes 2011;60:74–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter MD, Lee JH, Buchanan DM, et al. Comparison of outcomes among moderate alcohol drinkers before acute myocardial infarction to effect of continued versus discontinuing alcohol intake after the infarct. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1651–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puddey IB, Rakic V, Dimmitt SB, et al. Influence of pattern of drinking on cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors—a review. Addiction 1999;94:649–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:1105–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tousoulis D, Papageorgiou N, Androulakis E, et al. Fibrinogen and cardiovascular disease: genetics and biomarkers. Blood Rev 2011. Epub 2011/06/10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reiner AP, Carty CL, Carlson CS, et al. Association between patterns of nucleotide variation across the three fibrinogen genes and plasma fibrinogen levels: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. J Thromb Haemost 2006;4:1279–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician's guide. In: Services USDoHaH, ed. Rockville, MD: 2005:1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrick S, Blanc-Brude O, Gray A, et al. Fibrinogen. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1999;31:741–6 Epub 1999/09/01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green D, Foiles N, Chan C, et al. Elevated fibrinogen levels and subsequent subclinical atherosclerosis: the CARDIA Study. Atherosclerosis 2009;202:623–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arranz S, Chiva-Blanch G, Valderas-Martinez P, et al. Wine, beer, alcohol and polyphenols on cardiovascular disease and cancer. Nutrients 2012;4:759–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renaud SC, Ruf JC. Effects of alcohol on platelet functions. Clin Chim Acta 1996;246:77–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimmitt SB, Rakic V, Puddey IB, et al. The effects of alcohol on coagulation and fibrinolytic factors: a controlled trial. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1998;9:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, et al. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med 2004;38:613–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruf JC. Alcohol, wine and platelet function. Biol Res 2004;37:209–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in all-cause mortality risk according to alcohol consumption patterns in the national alcohol surveys. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:769–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sempos CT, Rehm J, Wu T, et al. Average volume of alcohol consumption and all-cause mortality in African Americans: the NHEFS cohort. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2003;27:88–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.