Abstract

The cis-acting elements necessary for the activity of DNA replication origins in metazoan cells are still poorly understood. Here we report a thorough characterization of the DNA sequence requirements of the origin associated with the human lamin B2 gene. A 1.2-kb DNA segment, comprising the start site of DNA replication and located within a large protein-bound region, as well as a CpG island, displays origin activity when moved to different ectopic positions. Genomic footprinting analysis of both the endogenous and the ectopic origins indicates that the large protein complex is assembled in both cases around the replication start site. Replacement of this footprinted region with an unrelated sequence, maintaining the CpG island intact, abolishes origin activity and the interaction with hORC2, a subunit of the origin recognition complex. Conversely, the replacement of 17 bp within the protected region reduces the extension of the protection without affecting the interaction with hORC2. This substitution does not abolish the origin activity but makes it more sensitive to the integration site. Finally, the nearby CpG island positively affects the efficiency of initiation. This analysis reveals the modular structure of the lamin B2 origin and supports the idea that sequence elements close to the replication start site play an important role in origin activation.

In 1963 Jacob, Brenner, and Cuzin (24) proposed the replicon model to explain the control of replication of the bacterial chromosome. In this model, DNA replication starts from a specific origin sequence, the replicator, that is recognized by a positive regulatory protein, the initiator. Since then the model has been validated in numerous prokaryotic and viral systems. The organization of the eukaryotic genome in multiple replication units distributed on several chromosomes has hampered the validation of this model in eukaryotes until the identification of the autonomous replicating sequences (ARS) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Initially identified for their ability to support the propagation of plasmid molecules in yeast cells, most of these sequences were successively proven to correspond to chromosomal replicators. ARSs are relatively short sequence elements (100 to 200 bp) that include the start site of replication, also called the origin of bidirectional DNA replication (OBR) (11). They consist of an essential 11-bp ARS consensus sequence (ACS) and of several auxiliary B elements that contribute to initiation activity. The ACS binds the origin recognition complex (ORC), a heteromeric complex of six proteins that assists the formation of a prereplicative complex on the origin. ORC orthologs have been isolated from all the eukaryotic species analyzed so far, including humans (for a review see reference 8). The ARS sequences and the ORC can be viewed as the prototypes of the eukaryotic replicator and initiator.

The major obstacle to the validation of the replicon model in metazoan cells was the failure to isolate the functional homologues of the ARS elements. Consequently, the identification of origin sequences had to wait for the development of highly sophisticated and sensitive techniques to map the initiation sites of DNA replication in a chromosomal context (for a review see reference 34). It is worth noticing, however, that sequences close to the replication start sites do not necessarily coincide with the replicator of Jacob's model. For instance, the replicator associated to the chorion gene locus in Drosophila melanogaster is composed of two elements: a 320-bp amplification control region 3 (ACE3) and an amplification enhancer region d (AERd), located about 1.5 kb away, that comprises the DNA replication initiation site oriβ (29). Initiation of DNA synthesis at oriβ requires the ACE3 element. On the other hand, even though the ORC efficiently binds three subfragments of ACE3, in vivo origin activity cannot be detected within the ACE3 element (7). The importance of sequences distant from the replication start site also has been observed in the hamster DHFR gene locus (26). Thus, initiation of DNA replication in metazoan cells, contrary to what was observed in lower eukaryotes, can be controlled both by local sequences and by sequences distant from the origin.

Following the identification of the genomic regions where DNA replication starts, a major challenge is to demonstrate whether these regions correspond to true replicators. One approach to address this point is to show that the genomic regions containing start sites of DNA replication are functional replicators when moved to ectopic positions of the genome. This has been proven in the case of the origins associated with the chorion gene cluster in D. melanogaster (29), the human β-globin (4), human c-myc (28, 30), and hamster DHFR genes (5). This analysis opens the door to the possibility of dissecting the elements required for the replicator activity.

In the last few years the human genomic region containing the replication start site of the lamin B2 replicon has been characterized in detail. This OBR maps within an extended in vivo-protected area (the origin-protected region, or OPR) that overlaps the 3′ end of the lamin B2 gene (2) and the promoter of the TIMM13 gene (10, 25). In vivo footprinting analysis indicates that the extension of the OPR oscillates during the cell cycle. Indeed, the footprint is established during the G1 phase, and its extension increases until the G1/S border. Origin firing results in a drastic shrinkage of the protected region in S phase. No protection is detectable in mitosis (3). Although this behavior recalls the assembly of pre- and postreplicative complexes on the yeast ARS sequences, there is no experimental evidence that the OPR sequence is actually required for the replicator activity.

Here we show that a 1.2-kb fragment of the lamin B2 replicon functions as a replicator when integrated at ectopic positions of the genome. This fragment comprises the OBR, the OPR, and part of the nearby CpG island. Our data indicate that the activity of this replicator critically depends on a 290-bp region containing the OPR and is influenced by the nearby CpG island. Interestingly, mutation of the OPR sequence makes the origin more sensitive to the integration site but does not prevent interaction with the hORC2 subunit of the ORC. In vivo footprinting analysis of both the wild-type and the mutated ectopic origin evidences a link between the activity of the replicator and the assembly of nucleoprotein complex on the origin sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures.

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (BioWhittaker), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 70 μg of gentamicin/ml in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. Cell clones were maintained in complete DMEM plus 0.2 mg of G418 (Gibco-BRL)/ml.

Plasmids.

The 1.2-kb BglII-NruI fragment of the lamin B2 gene, nucleotides 3728 to 4929 (GenBank accession no. M94363), was PCR amplified from L30E cosmid (10) and was cloned into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pBluescript II KS(+) (pBKS) (Stratagene). PCR-mediated mutagenesis was performed as previously described (31) to delete 35 bp between nucleotides 4035 and 4070 and to insert SalI, SfiI, and NotI sites at positions 4015, 4030, and 4115, respectively. The resulting construct, pBKS-eLamB2-ori, was digested with BglII-NruI to obtain the eLamB2-ori fragment used in cell transfection experiments. The 1.5-kb fragment of the B13 region was obtained by BamHI digestion of the L30E cosmid. The fragment obtained was subjected to PCR-mediated mutagenesis to introduce a 30-bp deletion between the target sequences of B13 primers and was cloned (pBKS-e-B13). To generate the eLamB2-mut construct we replaced, by PCR-mediated mutagenesis, the region of eLamB2-ori spanning from nucleotides 3860 to 4150 with an NdeI site. This site was successively used to insert a 290-bp fragment from pBKS-e-B13. The eLamB2* mutant was produced through PCR-mediated mutagenesis and differs from the wild-type sequence for replacement of 17 bp in the in vivo-protected area. (The wild-type and mutated sequences are shown in Fig. 3.) HIV-eLamB2 and HIV-eLamB2* differ from eLamB2-ori and eLamB2* for the replacement of the wild-type sequence between nucleotides 3823 to 3850 with the TATTGAGGCTTAAGCAGTGGGTTCCCTAGTTAGCCAGAGAGCTCCCAGGCTCAGATCTG sequence of the long terminal repeat A element of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (16). Mutant eLamB2-ΔCpG was obtained from pBKS-eLamB2-ori by digestion with NotI (position 4115) and religation of the vector. The resulting pBKS-eLamB2-ΔCpG construct was digested with BglII-SacI (position 2524 of pBKS) to release the eLamB2-ΔCpG fragment. All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

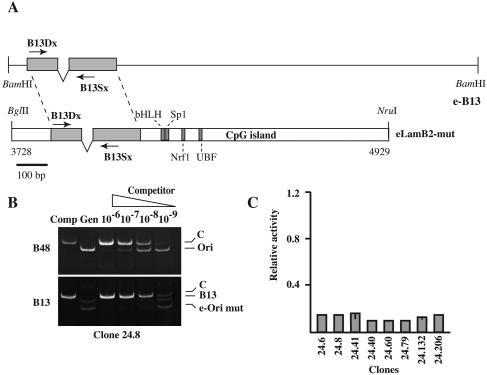

FIG. 3.

A 290-bp sequence comprising the OBR and the extended footprint is required for the replicator activity. (A) The 290-bp sequence from the e-B13 construct that was used to replace the OPR region in eLamB2-ori is indicated by a gray box. A scheme of the eLamB2-mut construct is shown. (B) Competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules purified from clone 24.8. e-Ori mut, ectopic origin. See the legend to Fig. 1 for further details. (C) Histogram of the replicator activity of the ectopic eLamB2-mut in the indicated clones as a fraction of the activity of the endogenous origin. The activity of the ectopic origin in some clones has been assessed in two independent experiments. The bar represents the difference between the two measured values.

Cell transfection.

Subconfluent HeLa cells were stably transfected by the calcium phosphate technique (22). Lamin B2 origin fragments were excised from the pBKS and were cotransfected in a 6:1 molar ratio with a solution of 100 ng of pOE8neo plasmid (9) linearized with SalI and 10 μg of HeLa genomic DNA carrier. Transfected cells were selected in 0.4 mg of G418/ml. After 12 days of growth in selective medium, cell clones were isolated and screened for single-copy integration of the exogenous lamin B2 origin by PCR and Southern blotting analysis.

Diagnostic PCR analysis.

For PCR analysis of stable cell clones, genomic DNA was prepared from single colonies (<104 cells). Cells were cracked on liquid nitrogen, heated at 95°C for 10 min, and then incubated with 20 μg of proteinase K (Sigma) at 50°C for 90 min. Half of the extracted DNA was amplified with Taq polymerase (Sigma) for 35 cycles in a standard reaction with a primer set specific for both the endogenous locus and the transfected fragment. Amplification conditions were 94°C for 30s, 56°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 20 s. Amplification products were resolved by 10% poly acrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in TBE (9 mM Tris-borate [pH 8.0], 0.4 mM EDTA), stained with ethidium bromide, and quantified by the National Institutes of Health image program (version 1.62). Clones in which amplification products from the endogenous and the ectopic sequences had a ratio of approximately 1 were selected.

Isolation of nascent DNA.

Nascent DNA was prepared from 108 exponentially growing cells as previously described (20). Nuclei were isolated in 5 ml of RSB (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2) with 0.4% NP-40. Nuclei were lysed with 15 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) and were incubated overnight at 56°C in the presence of 600 μg of proteinase K/ml. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with isopropanol, and dissolved in TNE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Three-hundred micrograms of total genomic DNA was heat denatured at 95°C for 5 min, chilled on ice for 5 min, loaded onto 5 to 30% linear neutral sucrose gradients in TNE, and centrifuged at 25,000 rpm (Beckman SW28 rotor) for 18 h at 20°C. One-milliliter fractions were collected from the top. Fractions containing single-stranded DNA molecules in the range of 0.7 to 1.5 kb, enriched in nascent DNA, were concentrated by ethanol precipitation.

Competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA.

Competitive PCR analysis was performed by using primer sets B48 (B48II Dx, 5′-GACTGGAAACTTTTTTGTAC-3′; B48 Sx, 5′-TAGCTACACTAGCCAGTGACCTTTTTCC-3′) and B13 (B13 Dx, 5′-GCCAGCTGGGTGGTGATAGA-3′; B13 Sx, 5′-CCTCAGAACCCAGCTGTGGA-3′). A constant volume of size-fractionated nascent DNA was added to amplification reaction mixtures containing decreasing amounts of competitor template (described in reference 21). Amplification was carried out as described above, except that 40 cycles were performed. Amplification products were resolved on 10% PAGE and were stained with ethidium bromide. The intensity of the amplification bands has been quantified with the National Institutes of Health image program (version 1.62). The ratio between endogenous and ectopic sequences has also been quantified before and after sucrose gradient purification of nascent DNA to more precisely evaluate the capacity of the ectopic origin to promote initiation of DNA synthesis.

In vivo DNA footprinting: DMS treatment.

Genomic DNA was prepared from 3 × 107 cells. In parallel an identical aliquot of cells was methylated in vivo with 0.1% dimethyl sulfate (DMS; Sigma) in prewarmed medium (37°C) for 1 min. After removal of the medium, cells were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 2% β-mercaptoethanol (Merck). Both untreated (control) and treated cells were harvested and lysed in 3 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) for 30 min at room temperature. Genomic DNA was purified by standard phenol-chloroform extraction and, after ethanol precipitation, was dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA). One-hundred micrograms of genomic DNA from untreated cells was incubated for 1 min at room temperature with 0.1% DMS. The reaction was stopped with ice-cold DMS stop buffer (1.5 M sodium acetate [pH 7.0], 1 M β-mercaptoethanol, 100 μg of tRNA/ml). DNA was ethanol precipitated and dissolved in TE buffer. Both in vivo and in vitro DMS-treated DNAs were cleaved at methylated guanine residues with 1 M piperidine (Sigma) for 30 min at 90°C. Piperidine was eliminated by evaporation and two consecutive ethanol and isopropanol DNA precipitations. DNA was dissolved at 0.4 μg/μl in TE buffer, pH 7.5.

In vivo DNA footprinting: ligation-mediated PCR.

Ligation-mediated PCR was performed with primer sets D and HIV specific for the endogenous and ectopic lamin B2 origins, respectively. Sequences and amplification conditions for both primers sets have been previously described (16, 18). Two micrograms of DMS-treated genomic DNA was annealed to 0.5 pmol of primer HIV A1 (5′-TATTGAGGCTTAAGCAGTGGGTTCC-3′) specific for the ectopic origin by denaturation at 95°C for 5 min and incubation at 60°C for 30 min in 10 μl of 1× ThermoPol buffer [10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1% Triton X-100] combined with 6 mM MgSO4. Primer extension was performed by adding 10 μl of 1× ThermoPol buffer, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 1 U of Vent exo− polymerase (New England Biolabs). The reaction mixture was incubated at 60°C for 5 min, 65°C for 10 s, 70°C for 10 s, and 76°C for 10 min. Blunt-end ligation was performed overnight at 16°C by adding 30 μl of linker mix containing 2 μM asymmetric double-stranded linker (oligonucleotides LMPCR1 [5′-GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTGAATTC-3′] and LMPCR2 [5′-GAATTCAGATC-3′] annealed to each other in 250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.7]), 1× ligation buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM ATP), 15.2% polyethylene glycol 8000, and 3 U of T4 DNA ligase (Promega). Ligation products were phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, dissolved in 20 μl of H2O, and added to 30 μl of PCR mix containing 1× ThermoPol buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2 mM MgSO4, 10 pmol of primer HIV A2 (5′-CCCTAGTTAGCCAGAGAGCTCCCAG-3′), 10 pmol of linker primer 1 (LMPCR1), and 1 U of Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs). The reaction mixture was denatured at 95°C for 3 min and was amplified for 18 cycles under the following conditions: 95°C for 1 min, 67°C for 2 min, and 76°C for 3 min with an increase of 5 s/cycle, followed by a final extension at 76°C for 10 min. For the end-labeling reaction mixture, 20 μl of the PCR products was added to an amplification reaction performed with 10 μl of 1× ThermoPol buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.6 mM MgSO4, 0.8 pmol of γ-33P-labeled HIV A3 primer (5′-GCCAGAGAGCTCCCAGGCTCAGATCTG-3′), and 0.5 U of Vent exo− polymerase. The reaction mixture was incubated at 95°C for 3 min and then was subjected to 7 cycles of PCR under the following conditions: 95°C for 1 min, 69°C for 2 min, 76°C for 7 min, and a final extension at 76°C for 3 min. Extension products were ethanol precipitated. Samples were denatured at 90°C for 5 min and were loaded on a 6% sequencing gel. Footprints were visualized by autoradiography.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP).

Samples of 108 asynchronous growing cells were cross-linked for 3 min with 1% formaldehyde (Merck) diluted in prewarmed medium (37°C). Cross-linking was quenched with a cold glycine solution (0.125 M glycine in PBS); cells were scrapped off, washed in PBS, and resuspended in 5 ml of hypotonic RSB buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2) for 10 min on ice. An equal volume of 0.4% NP-40 in RSB was added, followed by incubation on ice for 10 min. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation and were washed in RSB buffer. Unbound proteins were extracted in 5 ml of high-salt SNSB buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 M NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA). Finally, the nuclear material was resuspended in 1 ml of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA). All buffers were supplemented with protease inhibitor mix (Roche). Chromatin was sonicated with 30 short pulses on ice to yield an average DNA size of 700 bp. Immunoprecipitations were performed by incubation with 10 μg of anti-USF-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) rabbit polyclonal antibody H-86, 10 μg of anti-ORC2 (StressGen Biotechnology) monoclonal antibody, and 10 μg of anti-immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody as negative control. Immunoprecipitations were carried out for 2 h at 4°C on a rolling platform. One-hundred microliters of 50% protein A-Sepharose beads was added, and incubation was continued for 2 h. Beads were washed five times in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, five times in LiCl buffer (250 mM LiCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% deoxyxholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]), and five times in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA). Beads were then resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer and were incubated with an equal volume of 2× PK buffer (1% SDS, 200 mM NaCl, 600 μg of proteinase K/ml) for 3 h at 56°C. Cross-linking was reverted by incubation at 65°C for 6 h. DNA was purified by standard phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and was dissolved in 100 μl of TE. DNA was then analyzed by competitive PCR, as described above.

Western blotting.

For Western blotting experiments, proteins were resuspended in 1× SDS sample buffer (Laemmli buffer), fractionated onto SDS-10% PAGE, and electroblotted to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran; Schleicher & Schuell) in 20 mM Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4 (pH 7.0) buffer at 1.15 A for 60 min with cooling. Primary antibodies used were anti-ORC2 rabbit polyclonal antibody, a generous gift of B. Stillman, and anti-USF-1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Antibodies were revealed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG goat antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and membranes were developed with an ECL detection system (Amersham).

RESULTS

Experimental strategy.

As a first step toward the functional dissection of the lamin B2 origin (LamB2-ori), we tested the ability of LamB2-ori to promote initiation of DNA replication when moved to ectopic positions of the human genome. A linear fragment containing the origin was cotransfected into HeLa cells with a plasmid conferring resistance to G418.

To distinguish the ectopic (eLamB2-ori) from the endogenous sequence and, hence, to directly compare the activity of the two origins in promoting initiation of DNA replication, a 35-bp deletion was introduced within the 166-bp fragment amplified by primer set B48 (Fig. 1A). This fragment is the first sequence synthesized after origin firing and is the most abundant among the lamin B2 replicon sequences in the pool of nascent DNA molecules purified on sucrose gradients (21). B48 primers also anneal to the competitor used to quantify the abundance of nascent DNA molecules (21). Because the competitor is 35 bp longer than the wild-type sequence, coamplification of competitor endogenous and ectopic origin sequences results in the production of three DNA fragments that can be resolved by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1B).

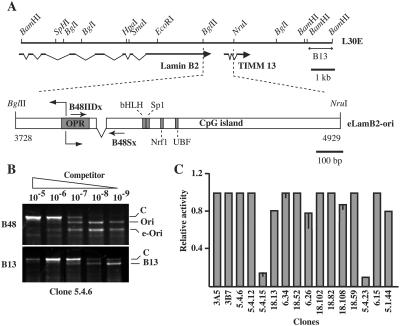

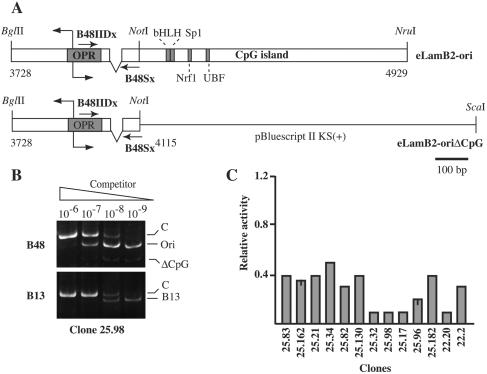

FIG. 1.

A 1.2-kb DNA fragment comprising LamB2-ori is a functional replicator at ectopic positions of the human genome. (A) Schematic representation of the genomic region in L30E cosmid. The exon-intron structure and position of lamin B2 and TIMM13 genes is indicated along with the position of the B13 region. Below is shown the scheme of the eLamB2-ori construct derived from the BglII-NruI fragment of L30E. Numbers refer to the genomic sequence (GenBank accession no. M94363). This fragment contains the start site of DNA replication of the lamin B2 replicon represented as two diverging arrows emanating from the extended in vivo-protected region (gray box). In the scheme the positions of additional in vivo footprints corresponding to binding sites for the indicated transcription factors are also shown (2, 18). Primers B48IIDx and B48Sx, used in the competitive PCR, are indicated by arrows. The interruption between the two arrows represents the 35-bp deletion that distinguishes the ectopic from the endogenous origin. (B) Competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules purified from clone 5.4.6. The competitor dilution is reported above each lane. The primer set used for amplification is indicated on the left of the gel image. The identity of the amplification bands is indicated on the right side. C, competitor; Ori, endogenous origin; e-Ori, ectopic origin; B13, B13 region. (C) Histogram of the replicator activity of the ectopic eLamB2-ori in the indicated clones as a fraction of the activity of the endogenous origin. The activity of the ectopic origin in some clones has been assessed in two independent experiments. The gray rectangle represents the average value, while the bar represents the difference between the two measured values. Origin activity has been measured by competitive PCR as for panel B. For more precise evaluation, we also determined the relative abundance of ectopic and endogenous sequences in total genomic DNA and in the pool of nascent DNA molecules.

After transfection, B48 primers were also employed to assess the copy number of the integrated ectopic origin in stable G418-resistant clones; only clones containing a single copy of eLamB2-ori were further considered. Southern blotting was then applied to verify both the copy number and the occurrence of random integration (see Materials and Methods). Finally, nascent DNA molecules were purified from independent clones by sucrose fractionation and were subjected to competitive PCR analysis to assess the abundance of sequences emanating from the endogenous and ectopic origins (see Materials and Methods). As a control, fractions containing nascent DNA molecules were also tested in competitive PCR with primer set B13, specific for a genomic region 5 kb away (Fig. 1A) that, as previously shown, did not contain an initiation site of DNA replication. The enrichment of B48 over B13 sequences was taken as a measure of the origin activity.

Replicator activity of the lamin B2 origin.

The strategy described above was initially applied to a 1.2-kb fragment of the lamin B2 replicon comprising the OBR, the in vivo-protected area (OPR), and the immediately downstream CpG island (Fig. 1A). Nascent DNA was purified from 16 independent clones containing a single copy of eLamB2-ori and was subjected to competitive PCR with primer sets B48 and B13. Figure 1B shows the analysis of clone 5.4.6. In this clone, identical amounts of endogenous and ectopic origin sequences were detectable in the pool of nascent DNA molecules, and both were 10-fold more abundant than B13 sequences, indicating that eLamB2-ori was as active as the endogenous origin in promoting initiation of DNA replication. A summary of the results obtained with the 16 independent clones is shown in the histogram of Fig. 1C. In 13 clones the ectopic and endogenous origins displayed comparable activity, indicating that the short (1.2 kb) DNA fragment encompassing the lamin B2 origin acted as a replicator when transferred to random positions of the human genome. Interestingly, we never observed an enrichment of ectopic versus endogenous B48 sequences in the pool of nascent DNA molecules. This could be explained by assuming that the endogenous origin fires in most, if not all, of HeLa cells. In this case, because each origin can be activated only once per cell cycle, the number of fragments emanating from a single-copy ectopic origin would at most equal those produced by the endogenous origin. In two clones (5.4.15 and 5.4.23) eLamB2-ori was not appreciably enriched over B13 sequences, indicating that the activity of the ectopic origin in these clones was drastically reduced or even abrogated. Because no rearrangements or mutations were detected in the ectopic origins of these two clones, the result supports the idea that the replicator activity of the 1.2-kb fragment is influenced either by the chromatin status or by sequence elements close to the site of integration. Whether the small (35 bp) deletion introduced in this fragment could play a role in the position-dependent effect is still unknown.

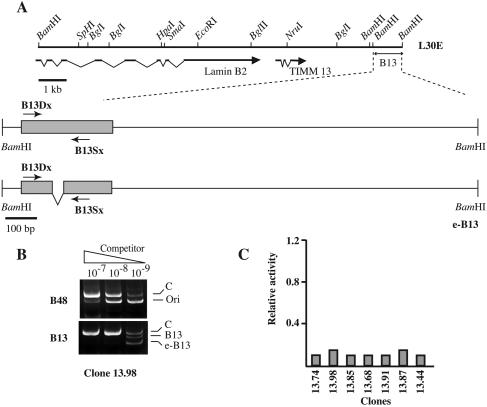

It has been proposed that autonomous replication in human cells is stimulated by simple sequence features that occur frequently in human DNA (23), raising the possibility that any human sequence could act as a replicator. To study this possibility we challenged in the same assay a 1.5-kb fragment from the B13 region that was located 5 kb away from the lamin B2 origin (Fig. 2) and did not contain a start site of DNA replication (21). A 30-bp deletion was introduced between the sequences, tagged by B13 primers in order to distinguish the ectopic (eB13) sequence from the endogenous sequence (Fig. 2A). Cell clones with a single-copy integration of eB13 were selected, and nascent DNA fragments were tested to assess the origin activity of this sequence. In seven out of seven clones we failed to observe origin activity of eB13 whose sequences were not enriched over those of the endogenous locus in the pool of nascent DNA molecules (Fig. 2B and C). This finding is consistent with the idea that the replicator activity is a distinguishing feature of specific sequences of the genome.

FIG. 2.

The B13 region does not act as a chromosomal replicator. (A) The relative position of the B13 region is shown under the scheme of the L30E cosmid. The structure of the 1.5-kb BamHI-BamHI fragment (eB13 construct) used in transfection is shown along with the position of primers B13Dx and B13Sx and of the 30-bp deletion that distinguishes the endogenous sequence from the ectopic sequence. (B) Competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules purified from clone 13.98. e-B13, ectopic B13 fragment. See the legend to Fig. 1 for further details. (C) Histogram of the replicator activity of the ectopic B13 region in the indicated clones as a fraction of the activity of the endogenous origin. The activity of the ectopic origin in some clones has been assessed in two independent experiments.

The in vivo-protected region is necessary for replicator activity.

The OBR of the lamin B2 replicon within a sequence on which a nucleoprotein complex is assembled in a cell cycle-dependent manner has been previously mapped (2). To assess whether this region was necessary for the replicator activity we replaced a 290-bp sequence containing the OPR with a fragment of the same size from the eB13 construct (eLamB2-mut in Fig. 3A). Because this substitution removed the target sites of primer set B48, analysis of nascent-strand fragments emanating from eLamB2-mut was performed with primer set B13, as for Fig. 2. Clones containing a single copy of eLamB2-mut were selected as described above, and the replicator activity of the mutated origin was assessed by competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules. In the hypothesis that the replicator activity was not due to the OPR region but rather to nearby sequence elements, such as the CpG island, one should observe an enrichment of ectopic over endogenous B13 sequences in the pool of newly synthesized molecules. Figure 3B shows the analysis of clone 24.8. In this clone, eLamB2-mut and endogenous B13 sequences were about 10-fold less represented in the pool of nascent DNA fragments than sequences recognized by B48 primers, indicating that the mutated origin was unable to promote initiation of DNA replication. An identical result was obtained with all the analyzed clones (see the histogram in Fig. 3C). On the basis of these data we concluded that the 290-bp fragment comprising the OPR and the OBR was necessary for the replicator activity.

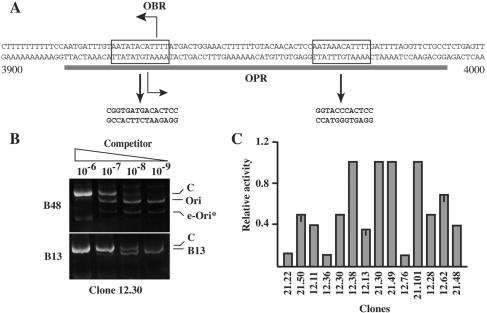

We then proceeded to investigate in more detail the elements required for origin specification, and we focused on the 70-bp OPR sequence. Within this AT-rich region two almost identical 12-mers are identifiable flanking the target site of the B48IIDx primer used in competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules. The upstream 12-mer contains the replication start site (Fig. 4A). We replaced 17 nucleotides within the two 12-mers, raising the overall G+C content of the region (Fig. 4A). The mutated 1.2-kb fragment (eLamB2*) was then used to transfect HeLa cells, and 14 independent clones containing eLamB2* integrated at random positions of the genome were analyzed as described above. Intriguingly, the analysis of clone 12.30 demonstrated that the mutated origin was only slightly less active than the endogenous one (Fig. 4B), as if the replacement of 17 nucleotides of the in vivo-protected area had a limited effect on the replicator function. The analysis of the additional 13 clones (see the histogram in Fig. 4C) supported the conclusion that the mutated origin was still active. However, contrary to what was observed with the wild-type sequence, in only four cases was eLamB2* as active as the endogenous origin. In all the remaining clones the abundance of nascent DNA molecules emanating from the mutated origin was reduced to different extents. A possible interpretation is that the 17-bp replacement makes the origin more sensitive than the wild-type sequence to the site of integration. At a molecular level the substitution could alter the composition of the protein complex responsible for the OPR, which in turn could affect the fraction of cells in which the ectopic origin fires. To rule out the possibility that observed differences between the ectopic wild-type sequence were due to random sampling of clones, we carried out a statistical analysis of the data shown in Fig. 1 and 4. We asked whether the presence of a 17-bp replacement could increase the probability of finding a clone in which the ectopic origin displayed an activity substantially reduced (more than 50%) compared to that of the endogenous sequence. Although the two groups contained a small number of clones, the chi-squared test supported the hypothesis that the wild-type and mutated origins actually behave in different manners and that the mutation significantly affects the initiation efficiency at ectopic sites (chi-square [1] = 6.451; P = 0.0111).

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide substitutions in the in vivo-protected sequence do not abrogate the replicator activity. (A) The in vivo-protected region (OPR) is indicated by a gray line below the sequence (nucleotides 3900 to 4000) of the lamin B2 origin. The replication start site (OBR) and two almost identical 12-mers (boxed sequences) are indicated. The mutated sequence in eLamB2* is shown immediately under the arrows. (B) Competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules purified from clone 12.30. e-Ori*, ectopic origin. See the legend to Fig. 1 for further details. (C) Histogram of the replicator activity of the ectopic eLamB2* in the indicated clones as a fraction of the activity of the endogenous origin. The activity of the ectopic origin in some clones has been assessed in two independent experiments. The bar represents the difference between the two measured values.

The CpG island affects origin activity.

The results described in the previous section point to the importance of the OPR sequence for the replicator activity. At the same time they suggest the relevance of chromosomal context in the ability of an origin to promote initiation of DNA replication. In this hypothesis, sequence elements known to control the chromatin packaging status, such as the CpG island, are expected to affect the replicator (6, 15). To test the role of the CpG island adjacent to the OPR sequence we generated a construct (eLamB2-oriΔCpG; Fig. 5A) in which the CpG island was replaced by a fragment of a bacterial vector. The replicator activity of this construct was then assayed as described above. As exemplified by the analysis of clone 25.98 (Fig. 5B), replacement of the CpG island with an unrelated sequence drastically affected the activity of the origin. Indeed, in none of the 12 analyzed clones was the mutated origin as active as the wild-type sequence was. However, in several clones the origin activity was not completely abrogated, and nascent DNA fragments emanating from the mutated origin were more abundant than the control B13 sequences (Fig. 5B and C). Thus, the CpG island, although not sufficient by itself for specifying DNA replication initiation sites, plays a positive role in the activity of the origin by increasing the efficiency of initiation. The CpG island might either act as a sort of insulator that protects against position effects or actively contribute to the establishment of a chromosomal context suitable for origin function.

FIG. 5.

The CpG island adjacent to the OPR influences the replicator activity. (A) Schematic representation of the eLamB2-oriΔCpG construct obtained by replacing the CpG island in eLamB2-ori with a fragment of pBKS vector as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules purified from clone 25.98. ΔCpG, ectopic origin. See the legend to Fig. 1 for further details. (C) Histogram of the replicator activity of the ectopic eLamB2-ΔCpG in the indicated clones as a fraction of the activity of the endogenous origin. The activity of the ectopic origin in some clones has been assessed in two independent experiments. The bar represents the difference between the two measured values.

Analysis of nucleoprotein complexes assembled in vivo on ectopic origins.

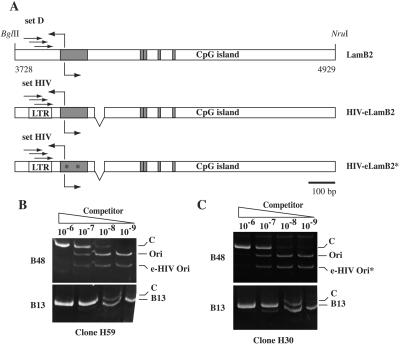

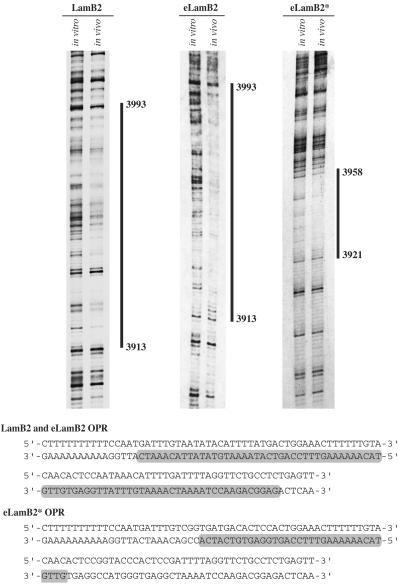

By means of in vivo footprinting experiments, an extended protected region (OPR) overlapping the lamin B2 origin has been detected (18). This protection was particularly visible by using primer set D located 50 bp upstream of the OPR (2, 18). We wondered whether a similar protection also could be detected on ectopic origins. In order to investigate this possibility and to independently analyze the complexes assembled on the ectopic and endogenous origins, we generated a version of eLamB2-ori (HIV-eLamB2) in which the target site of primer set D was replaced with an unrelated DNA sequence, a 59-bp sequence of the HIV-1 genome that was already successfully used for the in vivo footprinting analysis of the viral promoter (16) (Fig. 6A). Stable cell clones containing a single copy of HIV-eLamB2 were tested for the replicator activity of the transfected fragment. As exemplified by the analysis of clone H59 (Fig. 6B), replacement of the sequence recognized by primer set D had no effect on the ability of the origin to promote initiation of DNA replication. Consequently, the endogenous and ectopic origins in this clone were subjected to in vivo footprinting by using primer sets D and HIV, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7 and consistent with previous analysis (18), a protected 80-nucleotide area was detectable on the endogenous sequence. Notably, an identical protection was observed by using primer set HIV that targeted the ectopic origin. Thus, comparable nucleoprotein complexes are assembled on the two origins, although they are embedded in distinct chromatin contexts.

FIG. 6.

Replacement of sequence recognized by primer set D with an HIV sequence does not affect the replicator activity. (A) Schematic representation of the endogenous BglII-NruI region (LamB2) and of HIV-eLamB2 and HIV-eLamB2* constructs. The position of primer set D and primer set HIV used in in vivo footprinting experiments is indicated. (B) Competitive PCR analysis of nascent DNA molecules purified from clones H59 and H30 containing a copy of HIV-eLamB2 and HIV-eLamB2*, respectively. See the legend to Fig. 1 for further details.

FIG. 7.

In vivo footprinting analysis of ectopic origins. The endogenous lamin B2 origin and ectopic, either wild-type (eLamB2) or mutated (eLamB2*), origins have been subjected to in vivo footprinting analysis by the ligation-mediated PCR technique as described in Materials and Methods. 33P-labeled PCR products were resolved onto a 6% denaturing sequencing gel. In vitro, DMS-treated naked DNA; in vivo, DMS-treated cells. The sequence of the origin region is shown at the bottom of the figure. Protected sequences are indicated by gray bars. Numbers refer to the sequence of the genomic region (GenBank accession no. M94363).

The analysis of the eLamB2-mut clones (Fig. 3) indicated that the region containing the OPR was essential for the activity of the replicator. On the other hand, nucleotide substitutions in this region (eLamB2* construct; Fig. 4) were compatible with the origin activity. To investigate whether these replacements could affect the assembly of the nucleoprotein complex, we generated HIV-eLamB2*, a construct identical to eLamB2* except for the replacement of primer set D sequence with the target sequence of HIV primers. Competitive PCR of nascent DNA molecules proved that the ectopic HIV- eLamB2* origin in clone H30 was as active as the endogenous origin (Fig. 6C). As shown in Fig. 7, a footprint also was detectable on the mutated origin in clone H30, even though its extension was drastically reduced compared to what was observed with the wild-type sequence (37 versus 80 nucleotides). Indeed, although the part of the footprint proximal to the CpG island was no longer detectable, a protection was still visible between residues 3921 and 3958. The protected sequence comprised the mutated 12-mer distal to the CpG island, where the OBR was previously mapped on the endogenous sequence. It also contained an AT-rich box conserved with the wild-type sequence. Altogether these results suggest that the large footprint is not strictly required for the origin activity but rather for the ability of the origin to work in different chromatin contexts.

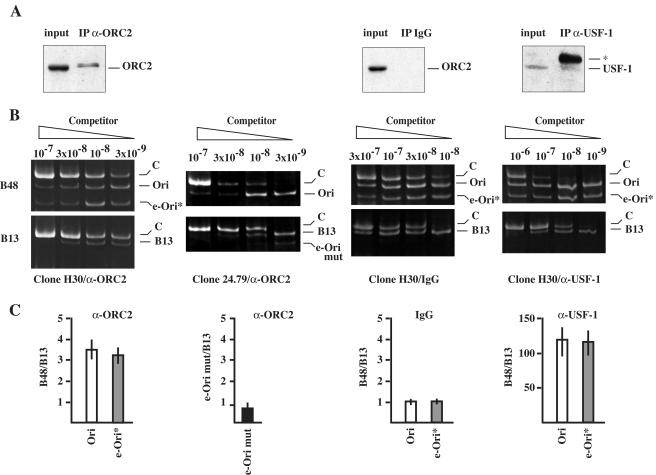

Interaction of hORC2 with mutated ectopic origins.

The origin activity assays depicted in Fig. 4 and 6 suggest the possibility that the ORC can interact with the mutated eLamB2* origin and can account at least in part for the protection detected in the in vivo footprinting experiments of Fig. 7. We decided to verify this possibility by means of the ChIP assay. Protein-DNA complexes in H30 cells were therefore cross-linked with formaldehyde, and sonicated chromatin was then subjected to immunoprecipitation with a monoclonal antibody specific for the ORC2 subunit of the ORC. As a control of the ChIP assay we tested whether the endogenous and ectopic origins could be immunoprecipitated by a polyclonal antibody against USF-1, a basic helix-loop-helix (b-HLH) transcription factor, for which a putative binding has been previously mapped by in vivo footprinting in the TIMM13 gene promoter close to the OPR (see Fig. 1A) (18). After reversion of cross-linking, immunoprecipitated DNA was subjected to competitive PCR with primers B48 and B13 to assess the enrichment of the origin sequence. As shown in the fourth panels of Fig. 8B and C, immunoprecipitation with anti-USF-1 antibodies produces an enrichment of both the endogenous and the mutated ectopic origins of approximately 100-fold stronger than that of the B13 sequences. This result indicates that the chromatin conformation of the ectopic origin is permissive for binding of transcription factors. Immunoprecipitation of the same chromatin preparation with antibodies against ORC2 gave a relatively more modest but reproducible enrichment of both the endogenous and the ectopic origins over the B13 sequences (first panels in Fig. 8B and C). No enrichment was detectable when chromatin was immunoprecipitated with control antibodies (third panels in Fig. 8B and C). This analysis showed that the endogenous and the ectopic B48 regions are both approximately threefold more enriched than B13 sequences in the pool of DNA fragments immunopurified with anti-ORC2 antibodies. This result is consistent with a previous ChIP analysis of the lamin B2 locus with anti-ORC2 antibodies that detected a fourfold enrichment of LamB2-ori relative to sequences located 4 kb away (27). Finally, we challenged a clone (clone 24.79) in the ChIP assay bearing a copy of eLamB2-mut in which the OPR region was replaced with a B13 sequence. As shown in the second panels of Fig. 8B and C, antibodies against hORC2 failed to immunoprecipitate eLamB2-mut better than endogenous B13 sequences, indicating that the interaction of the ORC with DNA is mediated by sequences in the OPR.

FIG. 8.

ChIP analysis. H30 cells containing eLamB2* were cross-linked with formaldehyde, and chromatin was immunoprecipitated with an antibody against hOrc2 (α-ORC2), with a control antibody against transcription factor USF-1 (α-USF-1) and with a control nonspecific antibody (IgG). In 24.79 cells containing eLamB2-mut, ChIP was performed with α-ORC2 only. (A) Immunoprecipitation was verified by Western blot analysis. Input, chromatin before immunoprecipitation; IP, immunoprecipitated material. Samples were probed with the antibody indicated on the right of each panel. The star identifies the heavy chain of the antibody. (B) Quantification of DNA immunoprecipitated from H30 and 24.79 cells. After reversion of cross-linking, immunoprecipitated DNA was subjected to competitive PCR with primers B48 and B13. Competitor dilutions are indicated above each lane. The identity of the different amplification bands is indicated on the right of each panel. (C) In the case of the H30 clone, histograms show the enrichment of endogenous (Ori) and ectopic (e-Ori*) sequences over B13 in the pool of DNA immunopurified with α-ORC2, α-USF-1, or control (IgG) antibodies. For clone 24.79, the histogram shows the enrichment of ectopic (e-Ori-mut) over endogenous B13 sequences immunopurified with α-ORC2 antibody. Bars indicate variations in three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this work we show that a 1.2-kb fragment of the lamin B2 replicon promotes initiation of DNA replication when integrated at ectopic positions of the human genome. This fragment represents the shortest human sequence identified so far that displays replicator activity. The activity of the origin crucially depends on a 290-bp sequence that contains the OBR and an extended in vivo-protected region. Moreover, the efficiency of initiation at ectopic sites seems to depend on an appropriate, still undetermined chromosomal context and is influenced by the nearby CpG island. It should be noted that our approach is more suitable for identifying DNA sequences absolutely required for the initiation activity than for discriminating whether partial origin activity reflects position or intrinsic effects of the introduced mutations. Nevertheless, our analysis supports the notion that in metazoan cells initiation of DNA replication is both sequence dependent, similar to what has been observed in bacteria and in lower eukaryotes, and sensitive to the chromatin context.

The OPR is important for the origin activity.

LamB2-ori shares important features with ARS sequences of S. cerevisiae. As in yeast, in fact, synthesis of the oppositely moving leading strands starts almost at the same positions on the two complementary helices (2) and occurs within an AT-rich area where a specific nucleoprotein complex is assembled in G1 phase. The extension of the protected region, which we termed OPR for origin-protected region, fluctuates during the cell cycle (3), recalling the assembly of pre- and postreplication complexes on ARS elements. In yeast, the ACS is recognized and bound by the ORC that acts as a landing pad for the remaining components of the prereplication complex (8). The ChIP analysis performed in this and in a previous study (27) demonstrate that LamB2-ori also is bound by the ORC. In accordance with this finding, the precise sites of binding of ORC1 and ORC2 have been recently mapped within the OPR (1). It is not unexpected, therefore, that the activity of the ectopic lamin B2 origin depends on a 290-bp fragment comprising the OPR. Replacement of this fragment with an unrelated human sequence of the same size (eLamB2-mut construct; Fig. 3) reduces the abundance of nascent DNA molecules emanating from the ectopic sequence to background levels and abrogates the interaction with ORC2. Notably, this result indicates that the nearby CpG island is not sufficient to specify initiation of DNA replication.

The detection of identical OPRs on the endogenous and ectopic origins (Fig. 7) indicates that the interaction of proteins with the origin is specific and mainly determined by the OPR sequence. This is the first time that protein complexes bound to ectopic and endogenous sequences in the same cells have been investigated by in vivo footprinting. A key element of this analysis is a short DNA sequence of the HIV-1 genome used to tag the ectopic fragment. The analysis reported in this paper demonstrates that, if applied in conjunction with the ChIP assay, this system allows the in vivo dissection of regulatory sequence elements and of the proteins they interact with.

Dissecting the OPR.

One important aspect addressed in this paper concerns the relationship between the replicator activity and the large protein complex assembled in vivo on the lamin B2 origin. The OPR corresponds to an AT-rich sequence in which two almost identical 12-mers are separated by a 28-bp spacer recognized by the B48IIDx primer used in competitive PCR. The upstream 12-mer contains the OBR. In order to understand the functional relevance of the two 12-mers, we replaced most of the A and T residues with C and G residues (Fig. 4). This change of 17 out of 80 bp of the OPR sequence makes the ectopic origin more sensitive to the site of integration but does not abolish its activity (eLamB2*; Fig. 4 and 6). The in vivo footprinting analysis of a full active clone indicates that this mutation drastically reduces the extension of the protected sequence. However, a shorter OPR, comprising the 28-bp spacer and the upstream mutated 12-mer, is still detectable. As suggested by the ChIP analysis with anti-ORC2 antibodies, this protection is most likely due to the interaction with the ORC. This hypothesis is consistent with a recent identification of the precise nucleotides of binding for the ORC2 protein within the 28-bp spacer (1). Moreover, this result is in accordance with in vitro observation that the interaction of the hORC4 subunit with the lamin B2 origin occurs on a specific AT-rich sequence within the OPR (33).

Collectively these results indicate that only a portion of the extended OPR is required for the activity of the replicator, suggesting a modular structure of the LamB2-ori, similar to that observed in the case of yeast ARS elements and of the human β-globin (4) and c-myc origins (28). The few mammalian DNA replication origins isolated so far do not share any consensus elements, except for a moderate bias in favor of AT-rich sequences. This could indicate a relatively poor specificity of binding of the ORC that is probably modulated by the interaction with some as-yet unidentified proteins. It is conceivable that transcription factors are involved in this process. Indeed, transcription factors have a major role in the activity of ARS sequences in S. cerevisiae (8) and in the activity of the origin required for the amplification of the chorion gene cluster in D. melanogaster (12).

The analysis of the eLamB2* mutant indicates that only a portion of the extended footprint detectable on the endogenous locus is actually required for the replicator activity, as if some of the proteins bound to the origin could have only an auxiliary function. The position-dependent activity of eLamB2* is compatible with the idea that some of the proteins interacting with the OPR region might contribute to establish a chromosomal context suitable for ORC binding and/or for origin activity. Putative candidates for this function could be the three homeotic proteins recently isolated for their ability to bind the sequence of the protected region both in vitro and in vivo (17). Notably, the binding site of one of these proteins (HOXC13) (17) is no longer present in the eLamB2* construct. Although a role for these proteins in origin activity has not yet been demonstrated, it is intriguing that at least one of them (HOXC10) (19) undergoes cycles of synthesis and degradation that parallel the assembly of the nucleoprotein complex on the lamin B2 origin.

Role of the CpG island.

A role of transcription regulatory elements in initiation of DNA replication is suggested by a great deal of observations. As proved by the analysis of both virus DNA genomes and ARS elements in yeast, transcription factors can participate in the initiation of DNA synthesis by interacting with the initiator complex (13, 14). Alternatively, transcription factors can alleviate the repressive effects of chromatin at the origin (13) by establishing a chromatin domain that is competent for transcription. Our finding that the CpG island plays a supporting role that increases the efficiency of initiation at the ectopic origin is perfectly consistent with the idea that chromatin context, and/or the epigenetic code of the integration site, is part of the mechanism that selects replication origins from a larger pool of possible initiation start sites dispersed throughout the genome. Similar mechanisms operate in lower eukaryotes and even in S. cerevisiae, where only a subset of the potential replication origins is active at any cell cycle (32). However, in metazoans this regulation has become more stringent and is probably linked to the development of these organisms. Remarkably, our finding substantiates the commonly accepted notion that a close relationship exists between DNA replication origins and CpG islands associated with promoters of highly transcribed genes (6, 15).

In conclusion, our analysis demonstrates that, in accord with the replicon model, sequence elements close to the OBR are required for the replicator activity in mammalian cells. Moreover, our data are compatible with the idea that sequence elements involved in the transcriptional regulation of the genome can assist the interaction of the ORC with the origin sequence.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by European Union (HPRN-CT-2000-00089) contracts to S.R. and A.F. and by grants from MURST 5%-CNR “Biomolecole per la salute umana” L.95/95 and Genetica Molecolare L.449/97 to G.B.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdurashidova, G., M. B. Danailov, A. Ochem, G. Triolo, V. Djeliova, S. Radulescu, A. Vindigni, S. Riva, and A. Falaschi. 2003. Localization of proteins bound to a replication origin of human DNA along the cell cycle. EMBO J. 22:4294-4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdurashidova, G., M. Deganuto, R. Klima, S. Riva, G. Biamonti, M. Giacca, and A. Falaschi. 2000. Start sites of bidirectional DNA synthesis at the human lamin B2 origin. Science 287:2023-2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdurashidova, G., S. Riva, G. Biamonti, M. Giacca, and A. Falaschi. 1998. Cell cycle modulation of protein-DNA interactions at a human replication origin. EMBO J. 17:2961-2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aladjem, M. I., L. W. Rodewald, J. L. Kolman, and G. M. Wahl. 1998. Genetic dissection of a mammalian replicator in the human beta-globin locus. Science 281:1005-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman, A. L., and E. Fanning. 2001. The Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase replication origin beta is active at multiple ectopic chromosomal locations and requires specific DNA sequence elements for activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1098-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antequera, F., and A. Bird. 1999. CpG islands as genomic footprints of promoters that are associated with replication origins. Curr. Biol. 9:R661-R667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin, R. J., T. L. Orr-Weaver, and S. P. Bell. 1999. Drosophila ORC specifically binds to ACE3, an origin of DNA replication control element. Genes Dev. 13:2639-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell, S. P., and A. Dutta. 2002. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71:333-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biamonti, G., G. Della Valle, D. Talarico, F. Cobianchi, S. Riva, and A. Falaschi. 1985. Fate of exogenous recombinant plasmids introduced into mouse and human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:5545-5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biamonti, G., M. Giacca, G. Perini, G. Contreas, L. Zentilin, F. Weighardt, M. Guerra, G. Della Valle, S. Saccone, S. Riva, et al. 1992. The gene for a novel human lamin maps at a highly transcribed locus of chromosome 19 which replicates at the onset of S-phase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3499-3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielinsky, A. K., and S. A. Gerbi. 1999. Chromosomal ARS1 has a single leading strand start site. Mol. Cell. 3:477-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosco, G., W. Du, and T. L. Orr-Weaver. 2001. DNA replication control through interaction of E2F-RB and the origin recognition complex. Nat. Cell. Biol. 3:289-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng, L., and T. J. Kelly. 1989. Transcriptional activator nuclear factor I stimulates the replication of SV40 minichromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Cell 59:541-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng, L. Z., J. L. Workman, R. E. Kingston, and T. J. Kelly. 1992. Regulation of DNA replication in vitro by the transcriptional activation domain of GAL4-VP16. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:589-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delgado, S., M. Gomez, A. Bird, and F. Antequera. 1998. Initiation of DNA replication at CpG islands in mammalian chromosomes. EMBO J. 17:2426-2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demarchi, F., P. D'Agaro, A. Falaschi, and M. Giacca. 1993. In vivo footprinting analysis of constitutive and inducible protein-DNA interactions at the long terminal repeat of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 67:7450-7460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Stanchina, E., D. Gabellini, P. Norio, M. Giacca, F. A. Peverali, S. Riva, A. Falaschi, and G. Biamonti. 2000. Selection of homeotic proteins for binding to a human DNA replication origin. J. Mol. Biol. 299:667-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimitrova, D. S., M. Giacca, F. Demarchi, G. Biamonti, S. Riva, and A. Falaschi. 1996. In vivo protein-DNA interactions at human DNA replication origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1498-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabellini, D., I. N. Colaluca, H. C. Vodermaier, G. Biamonti, M. Giacca, A. Falaschi, S. Riva, and F. A. Peverali. 2003. Early mitotic degradation of the homeoprotein HOXC10 is potentially linked to cell cycle progression. EMBO J. 22:3715-3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giacca, M., C. Pelizon, and A. Falaschi. 1997. Mapping replication origins by quantifying relative abundance of nascent DNA strands using competitive polymerase chain reaction. Methods 13:301-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giacca, M., L. Zentilin, P. Norio, S. Diviacco, D. Dimitrova, G. Contreas, G. Biamonti, G. Perini, F. Weighardt, S. Riva, et al. 1994. Fine mapping of a replication origin of human DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7119-7123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham, F. L., and A. J. van der Eb. 1973. Transformation of rat cells by DNA of human adenovirus 5. Virology 54:536-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinzel, S. S., P. J. Krysan, C. T. Tran, and M. P. Calos. 1991. Autonomous DNA replication in human cells is affected by the size and the source of the DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:2263-2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob, F., J. Brenner, and F. Cuzin. 1963. On the regulation of DNA replication in bacteria. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 28:329-348. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin, H., E. Kendall, T. C. Freeman, R. G. Roberts, and D. L. Vetrie. 1999. The human family of deafness/dystonia peptide (DDP) related mitochondrial import proteins. Genomics 61:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalejta, R. F., X. Li, L. D. Mesner, P. A. Dijkwel, H. B. Lin, and J. L. Hamlin. 1998. Distal sequences, but not ori-beta/OBR-1, are essential for initiation of DNA replication in the Chinese hamster DHFR origin. Mol. Cell. 2:797-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ladenburger, E. M., C. Keller, and R. Knippers. 2002. Identification of a binding region for human origin recognition complex proteins 1 and 2 that coincides with an origin of DNA replication. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1036-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, G., M. Malott, and M. Leffak. 2003. Multiple functional elements comprise a mammalian chromosomal replicator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1832-1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu, L., H. Zhang, and J. Tower. 2001. Functionally distinct, sequence-specific replicator and origin elements are required for Drosophila chorion gene amplification. Genes Dev. 15:134-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malott, M., and M. Leffak. 1999. Activity of the c-myc replicator at an ectopic chromosomal location. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:5685-5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montecucco, A., E. Savini, F. Weighardt, R. Rossi, G. Ciarrocchi, A. Villa, and G. Biamonti. 1995. The N-terminal domain of human DNA ligase I contains the nuclear localization signal and directs the enzyme to sites of DNA replication. EMBO J. 14:5379-53386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasero, P., A. Bensimon, and E. Schwob. 2002. Single-molecule analysis reveals clustering and epigenetic regulation of replication origins at the yeast rDNA locus. Genes Dev. 16:2479-2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stefanovic, D., S. Stanojcic, A. Vindigni, A. Ochem, and A. Falaschi. 2003. In vitro protein-DNA interactions at the human lamin B2 replication origin. J. Biol. Chem. 278:42737-42743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Todorovic, V., A. Falaschi, and M. Giacca. 1999. Replication origins of mammalian chromosomes: the happy few. Front. Biosci. 4:D859-D868. [DOI] [PubMed]