Abstract

Secondary capture has been proposed to be an alternative mechanism for leukocyte recruitment to an inflamed blood vessel wall. The process is controlled by interactions between PSGL-1 and L-selectin, both expressed on the cell surface. Interestingly, PSGL-1-L-selectin interactions are characterized by a unique phenomenon known as shear thresholding, whereby binding between PSGL-1 and L-selectin interactions is attenuated at low shear stresses and maximized at shear stresses ~ 1 dyne/cm2. Previously, shear thresholding and secondary capture have only been indirectly linked. Using a novel quantitative method, we analyzed leukocyte string formation in vitro and found that shear thresholding precluded secondary capture at low shear stresses while amplifying it at high shear stresses. Addition of the anti-L-selectin mAb DREG-56 strongly inhibited leukocyte string formation, suggesting a minor role for purely hydrodynamic interactions in secondary capture processes. Taken together, the data suggest that secondary capture is modulated by the shear thresholding property of L-selectin.

Keywords: L-selectin, shear-threshold, PSGL-1, neutrophil, leukocyte rolling, P-selectin, E-selectin, secondary capture

INTRODUCTION

In the initial steps of an inflammatory response, leukocytes tether and roll along the endothelium until a chemotactic signal triggers firm arrest and subsequent transmigration 7. Leukocyte tethering, the first resolvable adhesive interaction and subsequent rolling is governed primarily by interactions between P-selectin (CD62P) or E-selectin (CD62E), expressed on endothelial cells, and P-selectin Glycoprotein Ligand-1 (PSGL-1), constitutively expressed on the leukocytes 27. Leukocyte rolling can be also be initiated by an alternative mechanism referred to as secondary capture in which accumulation on the vessel wall is amplified by collisions between flowing and adherent leukocytes. Both hydrodynamic interactions and adhesive bond formation via PSGL-1 and L-selectin (CD62L), also constitutively expressed on the leukocyte surface,2,11,28 served to amplify leukocyte accumulation by bringing flowing leukocytes closer to the vessel wall.

All three selectins share a unique property by which leukocyte rolling and adhesive interactions with selectin ligands are optimized by a threshold level of hydrodynamic shear.12,23 In particular, leukocyte tethering via L-selectin-PSGL-1 or L-selectin-PNAd binding will not occur below a wall shear stress of ~ 0.4 dyne/cm2 in vitro. An identical phenomenon has been observed in vivo for L-selectin and P-selectin mediated leukocyte rolling in high endothelial venules and the mouse cremaster muscle vasculature. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain hydrodynamic shear thresholding in leukocyte rolling, being variously attributed to the unique molecular properties of L-selectin,15 convective transport,4,30 deformation of the contact patch during rolling,23 shear-dependent bond number,6 and catch bonds.32

The physiologic role of leukocyte shear thresholding has only been indirectly linked to leukocyte accumulation processes. To date, the strongest evidence for shear thresholding having physiologic relevance comes from studies of platelet interactions with von Willebrand factor (vWF). A gain-of-function mutant exists in the A-domain of vWF that effectively abolishes platelet shear thresholding on vWF surfaces and that correlates with severe deficiencies in the levels of circulating vWF.8,9,26,29 For leukocytes, despite evidence of hydrodynamic shear thresholding in vivo, nothing is known as to its physiological relevance. It has been speculated that the shear threshold phenomenon acts to prevent unwanted leukocyte accumulation and aggregation in vascular regions of low shear.12 One may be able to infer, then, that the shear enhancement of L-selectin interactions may amplify leukocyte aggregation and accumulation in regions of high shear, such as the wall of the blood vessel where L-selectin interactions are critical. While the argument for prevention of unwanted aggregation at low shear has not been validated in vivo, strong evidence exists that the L-selectin shear threshold can dramatically influence homotypic aggregation of leukocytes.14 Using a rheoscope, transient L-selectin aggregation events could be visualized that were strongly inhibited by lowering fluid shear rates below 400 s−1. Similarly, elevation of shear rates from 100 to 400 s−1 would rapidly trigger formation of transient doublets of leukocytes. Low shear can be almost as potent an inhibitor of L-selectin mediated aggregation as the addition of a blocking L-selectin antibody.

Interestingly, leukocyte-leukocyte interactions, governed by L-selectin-PSGL-1 binding are critical to initiate the secondary capture pathway. L-selectin mediated leukocyte-leukocyte interactions on a surface manifest themselves in vitro and in vivo in the form of leukocyte “strings”.11,13,17,22,24 By intravital microscopy, one group has demonstrated the importance of secondary capture to leukocyte accumulation in arterial vessels and large, but not small, venules.11 While the in vivo evidence for secondary capture remains controversial,20 Eriksson et al. (2001)11 cite leukocyte accumulation via secondary capture as a possible culprit in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

The secondary capture mechanism is largely controlled by L-selectin-PSGL-1 adhesion and occurs between flowing and adherent leukocytes on a variety of substrates including VCAM-1, ICAM, P-selectin, E-selectin, PNAd, and fibrinogen.1,17,25,31 Leukocyte strings are completely ablated by addition of a monoclonal antibody to L-selectin or by chymotrypsin treatment 1,25,31 and explain early observations of L-selectin dependence of neutrophil accumulation on P-selectin and E-selectin surfaces.16,20,22 Although a link between hydrodynamic shear thresholding and leukocyte secondary capture has been advanced,17 no formal definition of a leukocyte “string” has been established and therefore it is not known whether or not the shear threshold property of L-selectin regulates leukocyte accumulation through secondary capture. In fact, both experimental and computational evidence suggest that leukocyte strings can form without adhesive interactions over a broad range of shear stresses.3,18,19 In this model, strings form as a direct result of hydrodynamic perturbations in the fluid streamlines surrounding an adherent cell, leading to both upstream and downstream enhancements of leukocyte rolling.

To define the contribution of shear thresholding to leukocyte string formation, and its impact on overall leukocyte accumulation, we first established a quantitative definition of a leukocyte string. On the basis of the definition, we observed a strong correlation between the shear threshold property and leukocyte string formation. Furthermore, the quantitative analysis of string formation and dependency on flow suggest that L-selectin is a major contributor to leukocyte accumulation on P-selectin and E-selectin surfaces under venular flow conditions. This work highlights the importance of the unique biophysical characteristics of L-selectin dependent adhesion in the secondary capture mechanism and its relationship to hydrodynamic shear thresholding

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Protein Isolation

DREG-56, a function blocking mAb to L-selectin, was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Human P-selectin was isolated from outdated platelet packs by immunoaffinity chromatography as previously described.7 E-selectin was purified from Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell lysates transfected with wild-type human E-selectin cDNA as previously described.22

Neutrophil Isolation

Human neutrophils were obtained from 60 ml of heparin (10,000 U/ml)-anticoagulated whole blood. Neutrophils were isolated by density separation using 1-Step Polymorphs (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY). After isolation, neutrophils were washed and placed in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) without calcium and magnesium, supplemented with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and placed on ice. For flow chamber assays, neutrophils were taken from the reserve, centrifuged, and resuspended in HBSS containing 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 at room temperature.

For fluorescence experiments, neutrophils were labeled by one of two methods. Some neutrophils were labeled with 25 μM 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Other neutrophils were labeled with 2 μM calcein AM (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature. All neutrophils were washed and resuspended in HBSS containing 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES at room temperature.

Flow Chamber Assay

Polystyrene slides were cut from bacteriological Petri dishes (Falcon 1058, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and the diluted adhesion molecules were passively adsorbed to the slide and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 2 hours. Slides were blocked for nonspecific adhesion overnight at 4° C with 1% Tween in HBSS. The wall shear stress of the parallel plate flow chamber (Glycotech, Rockville, MD) was determined by the gasket dimensions, which were 0.01 inches thick and 1 cm wide. Cell or bead suspensions were drawn into the chamber at room temperature using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA). The chamber was mounted over an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Diaphot-TMD; Nikon, Garden City, NY) at 10X magnification (1 pixel = 1 μm) unless otherwise noted.

For fluorescence experiments, glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) were incubated with P-selectin for two hours at room temperature. Glass slides were blocked for nonspecific with 1% Tween and 1% HSA in HBSS at 4° C overnight. The slides were attached to the flow chamber and mounted over an inverted differential interference contrast microscope (Eclipse TE 300; Nikon, Garden City, NY) equipped with epifluorescent illumination using a 100-W HBO mercury lamp source coupled to a bandpass fluorescein and rhodamine filter set (Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT). Images were taken at 20X magnification by the digital high-speed camera (see below).

Data Acquisition, Image Analysis, and String Quantification

Images from some experiments were recorded using the Photron PCI FastCam (Photron USA, Inc.; San Diego, CA). The digital images were stored in the PCI’s memory board and transferred directly to the hard drive of a Dell Dimension 8400 (Dell, Inc.; Austin, TX) in AVI format. AVI movies were loaded on ImageJ and cells were identified and counted or tracked using a normalized cross-correlation algorithm.5 In other experiments, images were recorded on a VCR and digitized on an AG-5 frame acquisition card (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD) installed on a G4 Macintosh (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA) with NIH Image v.1.62 (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

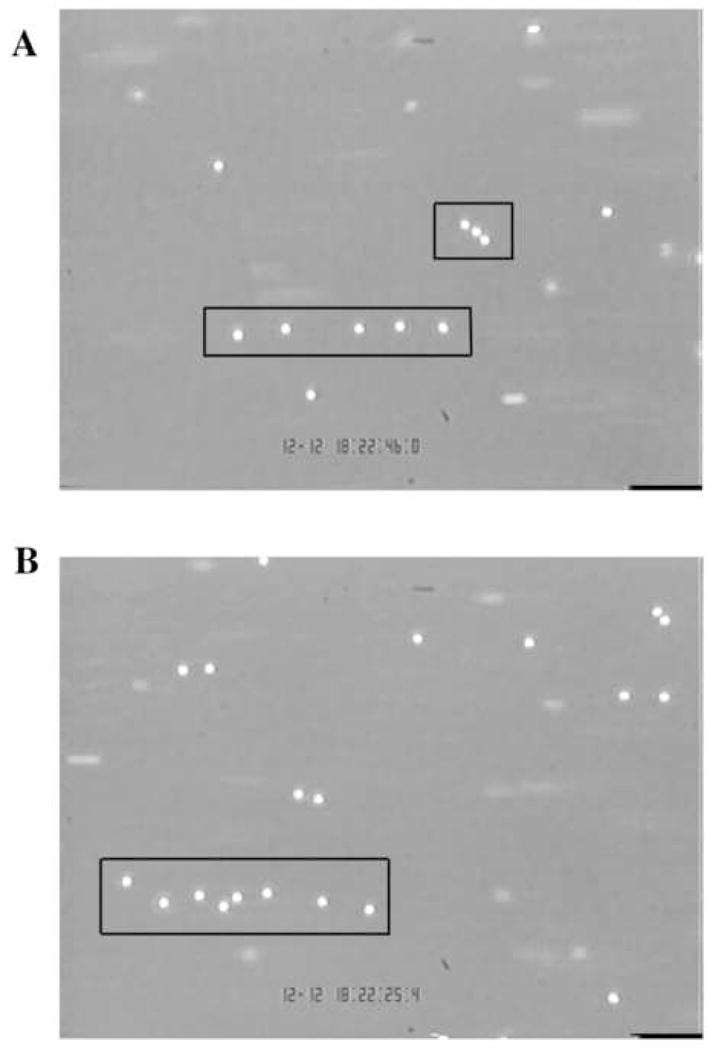

All images were opened in ImageJ v.1.32j (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and two example suspected strings are shown in Figure 1A and B. The phase contrast pictures were processed using a binary threshold (Process/Binary/Threshold in ImageJ). This process converted background pixels to a value of 0 and changed pixel values of cells to 255. The binary conversion was used as a first step to remove optical debris (e.g. cells out of the focal plane) and to simplify the process of locating cell centroids. The X–Y coordinates of the cells were saved to a text file using the Analyze/Tools/Save XY Coordinates function in ImageJ. The X–Y coordinates of the cells were loaded in Excel and plotted to give a pixel map of the original image. By comparing the original image and coordinate map, remaining unfocused cells and optical debris were cleaned up manually. A centroid map was then computed from the “cleaned” image by taking the coordinates of individual cells (x1, y1), (x2, y2), …, (xn, yn) and calculating the centroid according to the following equation:

| (4.1) |

FIGURE 1. Sample neutrophil string formation on P-selectin at 1 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress.

Red boxes outline suspected strings.

It was unnecessary to weight the pixels since, from the binary threshold, they all held the same value.

We imposed a set of three rules listed below to statistically define a leukocyte string.

Strings had to contain at least 3 neutrophils.

The best-fit line of the string could not be at more than a 45° angle relative to the direction of flow.

Neutrophils had to be within 50 μm of each other, straight-line distance, edge-to-edge (this is approximately equivalent to 5 cell diameters).

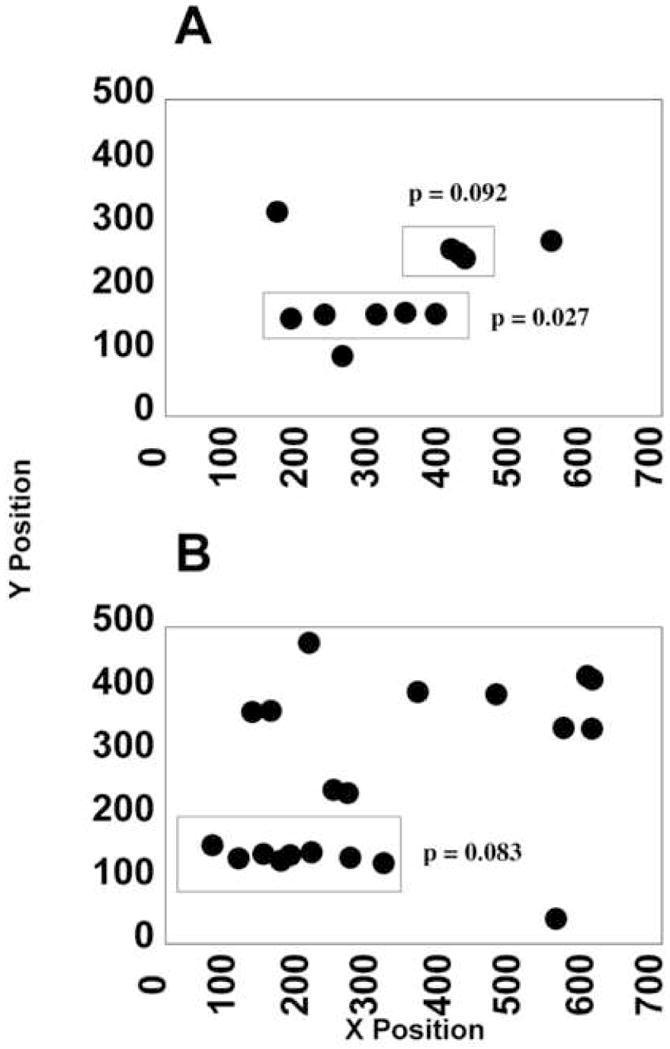

A neutrophil string was defined using the LINEST function in Excel. The coordinates of the centroid were input to the LINEST function and the F-statistic and dF (degrees of freedom) were calculated. The values of the F-statistic, dF, and number of neutrophils in the string were then entered into the FDIST function in Excel. FDIST returns the F probability distribution, so that with known degrees of freedom and the F test statistic, a p-value can be computed. Using a 90 % confidence interval, we computed the significance of the fit for all suspected neutrophil strings and a p-value of < 0.1 was considered a good fit (Fig. 2A and B).

FIGURE 2. Calculation of significance of fit of a line to a suspected leukocyte string.

Red boxes of Figure 1 match the red boxes of Figure 2. A fit was deemed significant for p < 0.1.

RESULTS

Visualization of Shear Dependent String Formation

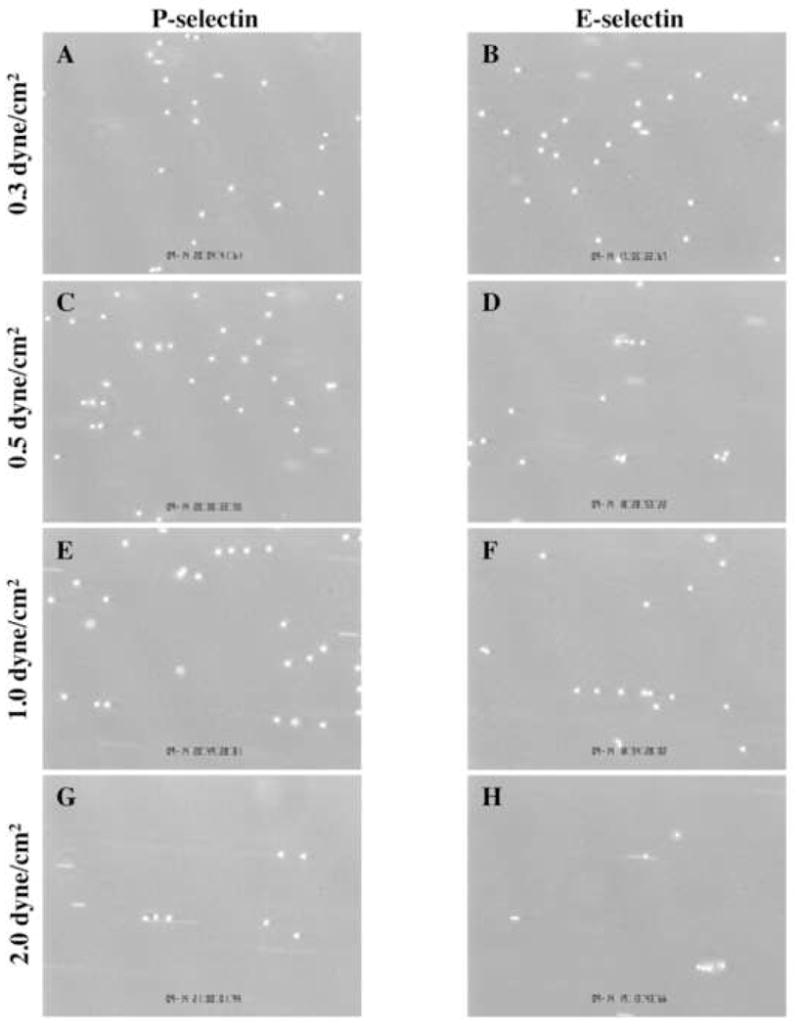

Neutrophils were flowed over P-selectin or E-selectin at 0.3, 0.5, 1, or 2 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress and at matched densities of ~100 sites/μm2. Images were taken at 3, 5, and 7 minutes in at least 10 fields of view, a sufficient number of images to cover the majority of protein-coated area. Representative images of leukocyte rolling flux are shown for both substrates and all wall shear stresses in Figure 3A-H for both P-selectin and E-selectin substrates. At wall low shear stresses, neutrophils tended to deposit randomly on the surface (Fig 3A and B, P-selectin and E-selectin respectively). However, as wall shear stresses were increased above 0.5 dyn/cm2 (see Fig. 3C and D) the string patterns became more evident (Fig. 3E and F). At the highest wall shear stress, string formation was still evident despite a significant drop in neutrophil tethering frequency resulting from the higher flow rates.

FIGURE 3. Images of string formation over a range of shear stresses.

Representative images of neutrophils rolling on P-selectin (left column) and E-selectin (right column) at shear stresses of 0.3 dyne/cm2 (A and B), 0.5 dyne/cm2 (C and D), 1.0 dyne/cm2 (E and F), and 2.0 dyne/cm2 (G and H). Neutrophils tend to line up in strings as shear stress increases.

Analysis of String Formation on P-selectin and E-selectin

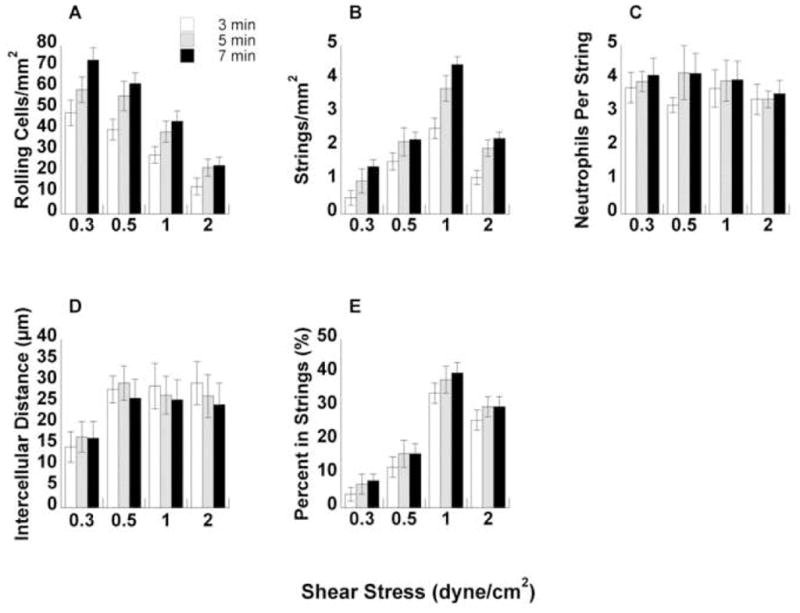

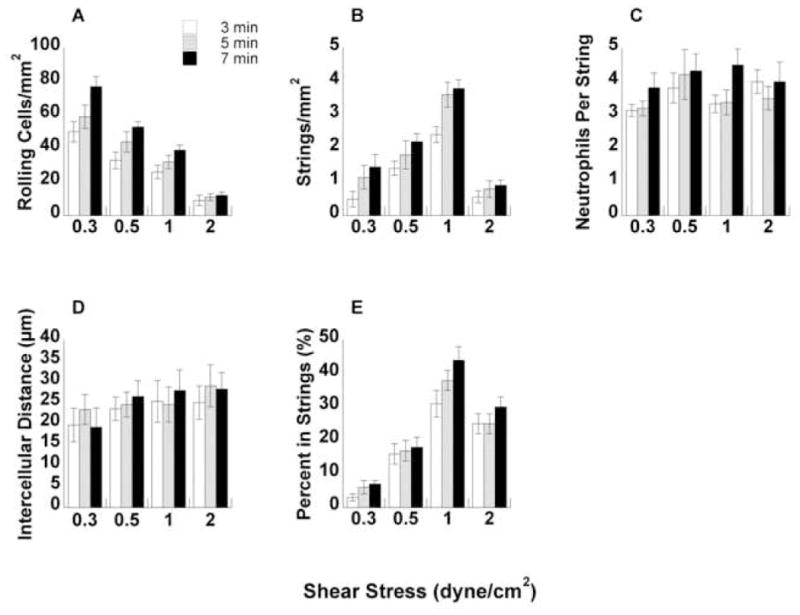

Total leukocyte rolling flux was measured on both P-selectin and E-selectin over a wide range of shear stresses at time points of 3, 5, and 7 minutes (Figs. 4A and 5 A, respectively). Rolling fluxes on each substrate exhibited a monotonic decay with increasing shear stress. As expected, the number of rolling cells increased at each time point for each shear stress. Unlike L-selectin, on which leukocyte rolling flux increases up to a maximum 1 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress, P-selectin and E-selectin facilitate maximum rolling fluxes at shear stresses as low as 0.3 dyne/cm2.23

FIGURE 4. Quantification of neutrophil string formation on P-selectin.

(A) Total number of neutrophils rolling on P-selectin over a range of shear stresses at 3, 5, and 7 minutes. (B) Number of strings formed per mm2 based on string definition. (C) Number of neutrophils in each string. (D) Average intercellular distance between each neutrophil in the string. Intercellular distance was measured from the edge of one cell to the edge of an adjacent cell in a straight line. (E) Percent of leukocytes in a string. This value was computed by multiplying C by B and dividing by A.

FIGURE 5. Quantification of neutrophil string formation on E-selectin.

(A) Total number of neutrophils rolling on E-selectin over a range of shear stresses at 3, 5, and 7 minutes. (B) Number of strings formed per mm2 based on string definition. (C) Number of neutrophils in each string. (D) Average intercellular distance between each neutrophil in the string. Intercellular distance was measured from the edge of one cell to the edge of an adjacent cell in a straight line. (E) Percent of leukocytes in a string. This value was computed by multiplying C by B and dividing by A.

Using the leukocyte string definition defined above in the Methods section, we counted the total number of strings in each field of view for P-selectin and E-selectin over a range of shear stresses (Figs. 4B and 5 B, respectively). On both substrates, the number of strings per area increased up to 1 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress with a subsequent decrease at 2 dyne/cm2 at all time points. Interestingly, the behavior closely followed the pattern of the L-selectin shear threshold phenomenon.23 To further quantify the string, we counted the number of neutrophils in each string for all wall shear stresses on P-selectin and E-selectin (Figs. 4C and 5 C, respectively). The average number of neutrophils in each string was comparable between the substrates and did not change dramatically between shear stresses and time points.

The distance between leukocytes in each string was measured for all experimental conditions on P-selectin and E-selectin (Figs. 4D and 5 D, respectively). The intercellular distance was measured from leukocyte edge to leukocyte edge and could not exceed 50 μm based on the inclusion requirement for a string. On both substrates, intercellular distances ranged from 15 μm to 30 μm, which represents a 1.5 to 3-cell diameter range on average. It should be noted that as flow rates increase, the 50μm limit becomes increasingly stringent.

The percent of total leukocytes in string conformation was calculated for all shear stresses on P-selectin and E-selectin (Figs. 4E and 5 E, respectively). The percent of neutrophils in strings was calculated by multiplying the number of neutrophils per string by the number of strings per area. The number of neutrophils per area in a string was then divided by the total number of rolling cells to give the fraction of neutrophils in a string. Curiously, the percent of neutrophils in string conformation increased dramatically from ~5% at 0.3 dyne/cm2 up to nearly 40% at 1 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress on both P-selectin and E-selectin, with a slight drop-off at 2 dyne/cm2. The response mirrored the pattern of L-selectin shear thresholding.

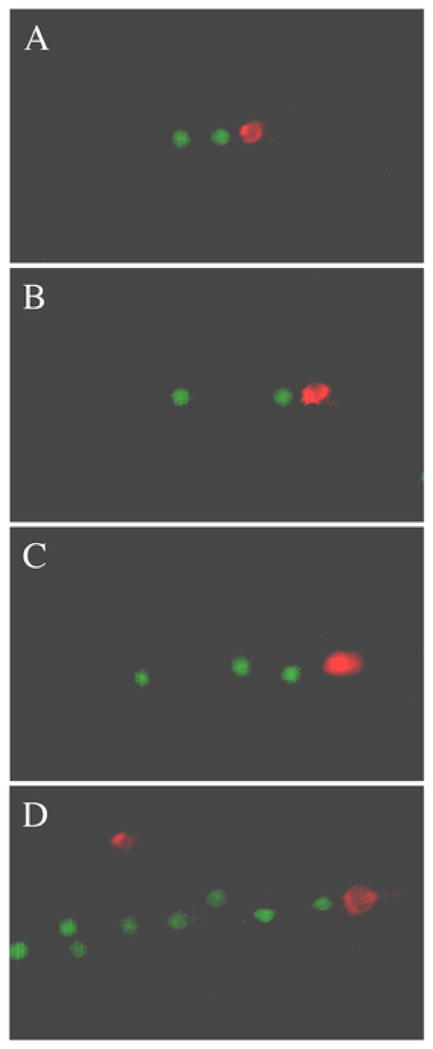

Fluorescence Imaging of String Formation

To define the sequence of leukocyte string formation, two separate batches of neutrophils were labeled with either calcein AM (green fluorescence) or DiI (red fluorescence). The neutrophils labeled with DiI were diluted to 10,000 cells/ml, a magnitude of order lower than our standard bulk concentration of cells. DiI labeled cells were flowed into the flow chamber over P-selectin (~100 sites/μm2 at a wall shear stress of 0.3 dyne/cm2 for one minute. This produced a sparse coating of rolling neutrophils. Buffer was then flowed in to clear the chamber of DiI labeled cells except for the cells rolling on the surface. At this point, the calcein labeled neutrophils were flowed in at 1 dyne/cm2 and images of neutrophil strings were taken at 45 s intervals (Fig. 6A–D). DiI labeled neutrophils served as nucleation sites for the calcein labeled neutrophils to bind to the P-selectin surface at 1 dyne/cm2.

FIGURE 6. Fluorescence images of neutrophil string formation.

Nucleating cells (red) were flowed in at 0.3 dyne/cm2 on a P-selectin substrate and calcein labeled neutrophils (green) were flowed over them at 1 dyne/cm2. Flow is from left to right.

Effects of L-selectin mAb DREG-56 on Secondary Capture

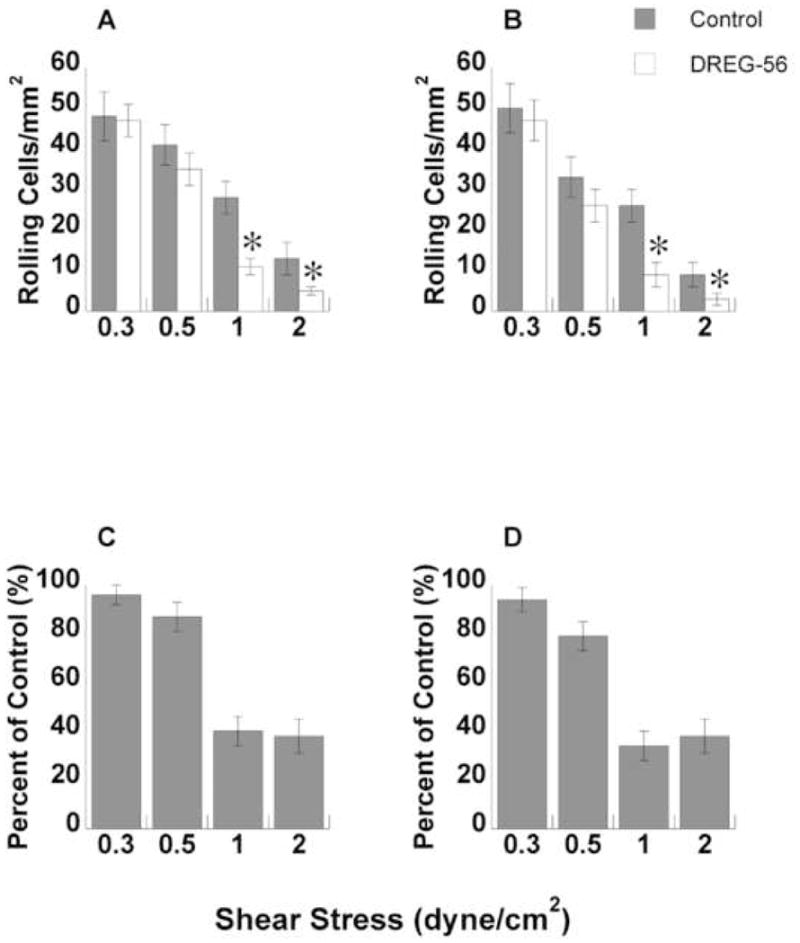

DREG-56, a function blocking mAb for L-selectin, was used to inhibit L-selectin- PSGL-1 interaction to assess the impact of L-selectin blockage on leukocyte rolling flux on P-selectin and E-selectin. Blockage of L-selectin prevented the adhesive contributions to neutrophil string formation. Total rolling flux was measured after 3 minutes over a range of wall shear stresses on both P-selectin and E-selectin with and without DREG-56 (Fig. 7A and B, respectively). At the lowest shear stress tested, 0.3 dyne/cm2, no discernible difference in total rolling flux was measured on either substrate. At 0.5 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress, addition of DREG-56 decreased total rolling flux, but not by a statistically significant amount. At wall shear stresses of 1 and 2 dyne/cm2, DREG-56 eliminated a statistically significant amount of total rolling cells (p < 0.05, paired t-test).

FIGURE 7. Rolling flux analysis with mAb on P-selectin and E-selectin.

Neutrophils were treated with DREG-56 and flowed over P-selectin (A) or E-selectin (B) and the number of rolling neutrophils was counted per unit area. The number of rolling neutrophils with mAb was statistically lower than controls at 1 dyne/cm2 and 2 dyne/cm2 (p < 0.05, t-test). The total number of rolling neutrophils with mAb is shown as a percent of control on P-selectin (C) and E-selectin (D). All error bars are ± S.E.M.

The number of leukocytes rolling with DREG-56 inhibition was calculated and plotted as a percent of control cells (those cells with no mAb added) for each substrate at all wall shear stresses (Fig. 7C and D). At 0.3 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress, addition DREG-56 had little impact on the number of rolling cells as a percent of control (96% and 95% on P-selectin and E-selectin, respectively). DREG-56 trimmed leukocyte rolling to 87% and 80% of control at 0.5 dyne/cm2. At 1 and 2 dyne/cm2 wall shear stress, blockade of L-selectin-PSGL-1 interactions reduced rolling to 35–40% of control on both substrates. Inhibition of the secondary capture pathway exhibited little effect at shear stresses near or below the shear threshold, but produced a dramatic abrogation in total rolling flux at shear stresses above the threshold.

DISCUSSION

Secondary capture contributes up to 50% of total leukocyte capture in all but the smallest microvessels. In addition to contributing to accumulation in arteries and venules, secondary capture appears to be important in the formation of leukocyte-rich atherosclerotic plaques.10,11 In this study, we sought to establish a correlation between the shear threshold property of the L-selectin-PSGL-1 bonds and secondary leukocyte capture using a novel quantitative method.

Rolling leukocyte strings are easily identified by visual observation due to their non-random appearance and orientation with the direction of flow. However, until now no one has established a statistical framework to identify and count leukocyte strings. Our method attempted to eliminate as much experimental subjectivity as possible. Previous approaches have solely relied on watching a string form and deducing that leukocytes attaching downstream from a nucleating cell must have resulted from a collision and secondary capture event. By using a set of rules and statistical tests to define the degree of cell orientation, we reduced experimental biases and more reliably identified secondary capture events and the resultant leukocyte strings.

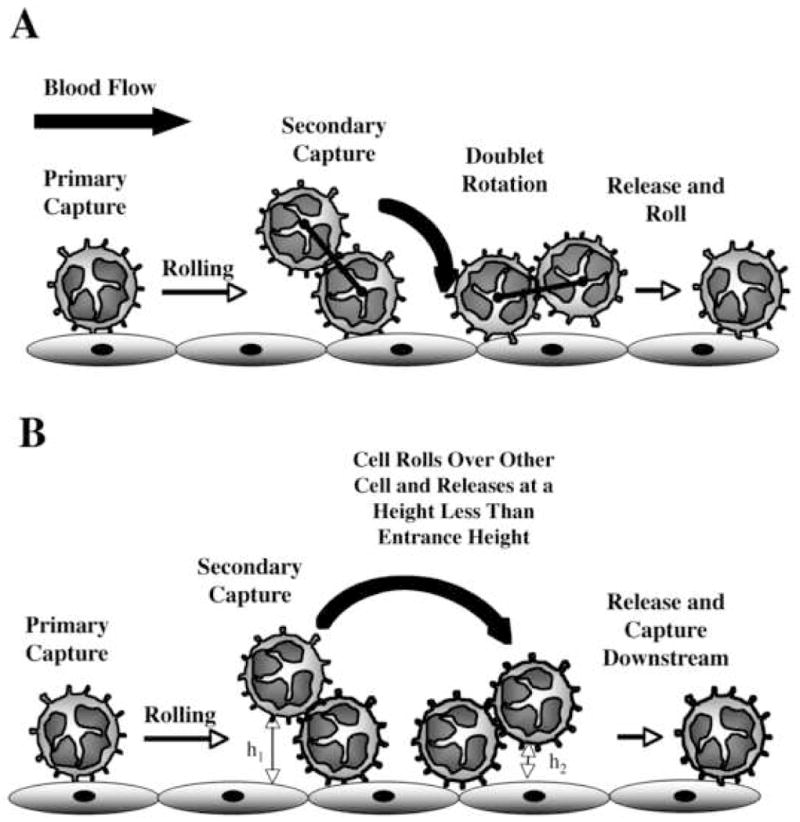

Two pathways appeared to exist for leukocyte interactions with already rolling or adherent cells to amplify accumulation on the vascular wall. Collisions of flowing and rolling leukocytes in some cases lasted long enough to form a transient doublet of leukocytes rolling on the substrate, similar to what has been observed in bulk suspension.14 Once formed, a transient doublet appeared to be torqued into the wall via rotation of the already adherent cell, delivering the newly captured cell to the vascular endothelium and releasing it to roll along the vessel wall (Fig. 8A). Alternatively, an adherent leukocyte acting through a combination of hydrodynamic effects and transient adhesive interactions would move the passing leukocyte closer to the substrate, where Brownian motion or collisions with adherent leukocytes further downstream would eventually result in a clearly defined secondary capture event (Fig. 8B). It may be possible that the second pathway described above may account for the initial failure to detect secondary capture events in vivo.20

FIGURE 8. Two proposed mechanisms for secondary capture.

(A) A neutrophil from free stream can collide with an adherent neutrophil and form a transient doublet. Shear forces can then torque the doublet into the wall delivering the previously free-stream neutrophil to the surface. (B) A neutrophil in free stream can collide with an adherent neutrophil, roll over or around it, and be released at a height closer to the surface to increase the probability of downstream capture.

At relatively low shear (less than 0.7 dyn/cm2 wall shear stress in vitro), leukocyte adhesion to P-selectin or E-selectin appeared to depend for the most part on primary tethering to the substrate, as blocking L-selectin had limited inhibitory effects on the rolling flux. Likely due to the shear threshold property of L-selectin, secondary capture was limited and failed to augment leukocyte rolling flux significantly. When leukocytes first emerge from the capillaries during inflammation and begin rolling, they are typically in a stretch of vasculature with relatively low shear rates and are already in molecular contact with the vessel wall due to the small size of the blood vessel.21 In fact, primary tethering events are as rare as secondary tethering events in the region of microvasculature immediately downstream of the capillary bed.20 Small blood vessels, on the order of a few leukocyte diameters or less, may not require the augmentation in leukocyte accumulation provided by secondary capture mechanisms.

A very different situation exists in arteries, arterioles and large venules, where feeding capillaries are not available to pre-adhere leukocytes to the endothelium. Well suited for this challenge is an adhesion pathway in which leukocytes co-expressing PSGL-1 and L-selectin protrude into the vessel lumen to intercept free-flowing leukocytes whose trajectories might only rarely intercept the vessel wall. In this instance, the shear threshold property acts to augment and amplify leukocyte adhesion on the vessel wall within a relatively narrow range of flowrates. At an optimum shear rate interactions between leukocytes would have a higher probability of forming bonds that would pull the incoming leukocyte into close proximately of the endothelium. Shear rates below the hydrodynamic threshold would therefore suppress aggregation and secondary capture.

Several studies have emphasized the importance of hydrodynamic effects created by an adherent leukocyte to string formation, arguing that strings can form in the absence of homotypic leukocyte adhesion.18 However, when homotypic adhesion was blocked string formation was strongly inhibited, suggesting that L-selectin adhesive interactions amplified accumulation. Furthermore, the majority of strings formed in a piecewise linear fashion; in other words, a nucleating leukocyte facilitated string formation downstream in most cases, and only rarely upstream. While the hydrodynamic interaction is likely critical to bring the leukocyte membranes into binding distance, the additional trajectory perturbation created by transient adhesive interactions appeared to enhance the probability of a downstream tethering event.

While L-selectin’s biomechanical properties have been hypothesized to be tuned to exploit the hydrodynamics of blood flow near the vessel wall, it remains unclear what might be the in vivo consequence of alteration of the balance of force sensitive bonds, catch bonding properties, and formation rates characteristic of L-selectin. Among the more obvious predictions would be that a general lengthening of L-selectin bond lifetimes would lead to the formation of larger and longer-lived leukocyte aggregates. Unwanted aggregation of leukocytes in the blood might well be expected to lead to plugging events in the microcirculation of numerous organ systems (i.e., lung, kidney, or brain) and increased opportunity for uncontrolled platelet interactions. Amplification of leukocyte accumulation on the vessel wall, while advantageous during acute inflammation, could lead to tissue damage in some areas and a failed response in others. Pathological consequences of unwanted and inadvertent leukocyte aggregation could therefore be severe, by both impeding the immune response and potentially precipitating severe thrombotic events.

Taking the shear threshold phenomenon to be a fundamental characteristic of L-selectin interactions, our data strongly suggest that leukocytes failed to form strings at low shear stresses due to an inadequate amount of force as a flowing leukocyte encountered an adherent one. While leukocytes are fairly rigid compared to erythrocytes, they can deform small amounts during a collision such that the number of L-selectin and PSGL-1 receptors could rapidly increase.14,17 At the low end of the shear stresses examined in this study, deformation may be insufficient to achieve a critical number of L-selectin receptors. At the high end of shear stresses examined, the brevity of the collision time and the resultant inability of a contact patch to reach its optimal size due to the leukocyte viscoelastic properties might limit the frequency of secondary capture interactions. An additional feature of L-selectin-PSGL-1 bonds, their catch-slip characteristics in which force strengthens individual bonds has been previously shown to contribute to leukocyte shear thresholding,32 and may complement the effects of leukocyte mechanical properties on secondary capture processes.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of NIH HL54614 (M.B.L.) and EB002185 (M.B.L.). We also thank Scott Diamond for valuable discussion.

References

- 1.Alon R, Fuhlbrigge RC, Finger EB, Springer TA. Interactions through L-selectin between leukocytes and adherent leukocytes nucleate rolling adhesions on selectins and VCAM-1 in shear flow. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:849–865. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruehl RE, Springer TA, Bainton DF. Quantitation of L-selectin distribution on human leukocyte microvilli by immunogold labeling and electron microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:835–844. doi: 10.1177/44.8.8756756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caputo KE, Lee D, King MR, Hammer DA. Adhesive dynamics simulations of the shear threshold effect for leukocytes. Biophys J. 2007;92:787–797. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang KC, Hammer DA. The forward rate of binding of surface-tethered reactants: effect of relative motion between two surfaces. Biophys J. 1999;76:1280–1292. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheezum MK, Walker WF, Guilford WH. Quantitative comparison of algorithms for tracking single fluorescent particles. Biophys J. 2001;81:2378–2388. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75884-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Springer TA. An automatic braking system that stabilizes leukocyte rolling by an increase in selectin bond number with shear. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:185–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiVietro JA, Smith MJ, Smith BR, Petruzzelli L, Larson RS, Lawrence MB. Immobilized IL-8 triggers progressive activation of neutrophils rolling in vitro on P-selectin and Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1. J Immunol. 2001;167:4017–4025. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doggett TA, Girdhar G, Lawshe A, Miller JL, Laurenzi IJ, Diamond SL, Diacovo TG. Alterations in the intrinsic properties of the GPIbalpha-VWF tether bond define the kinetics of the platelet-type von Willebrand disease mutation, Gly233Val. Blood. 2003;102:152–160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doggett TA, Girdhar G, Lawshe A, Schmidtke DW, Laurenzi IJ, Diamond SL, Diacovo TG. Selectin-like kinetics and biomechanics promote rapid platelet adhesion in flow: The GPIbalpha-vWF tether bond. Biophys J. 2002;83:194–205. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75161-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson EE, Xie X, Werr J, Thoren P, Lindbom L. Direct viewing of atherosclerosis in vivo: plaque invasion by leukocytes is initiated by the endothelial selectins. FASEB J. 2001;15:1149–1157. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0537com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson EE, Xie X, Werr J, Thoren P, Lindbom L. Importance of primary capture and L-selectin-dependent secondary capture in leukocyte accumulation in inflammation and atherosclerosis in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;194:205–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finger EB, Puri KD, Alon R, Lawrence MB, von Andrian UH, Springer TA. Adhesion through L-selectin requires a threshold hydrodynamic shear. Nature. 1996;379:266–269. doi: 10.1038/379266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goel MS, Diamond SL. Neutrophil enhancement of fibrin deposition under flow through platelet-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2093–2098. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldsmith HL, Quinn TA, Drury G, Spanos C, McIntosh FA, Simon SI. Dynamics of neutrophil aggregation in couette flow revealed by videomicroscopy: effect of shear rate on two-body collision efficiency and doublet lifetime. Biophys J. 2001;81:2020–2034. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75852-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg AW, Brunk DK, Hammer DA. Cell-free rolling mediated by L-selectin and sialyl Lewis(x) reveals the shear threshold effect. Biophys J. 2000;79:2391–2402. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76484-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafezi-Moghadam A, Ley K. Relevance of L-selectin shedding for leukocyte rolling in vivo. J Exp Med. 1999;189:939–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadash KE, Lawrence MB, Diamond SL. Neutrophil string formation: hydrodynamic thresholding and cellular deformation during cell collisions. Biophys J. 2004;86:4030–4039. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King MR, Hammer DA. Multiparticle adhesive dynamics: hydrodynamic recruitment of rolling leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14919–14924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261272498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King MR, Kim MB, Sarelius IH, Hammer DA. Hydrodynamic interactions between rolling leukocytes in vivo. Microcirculation. 2003;10:401–409. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunkel EJ, Chomas JE, Ley K. Role of primary and secondary capture for leukocyte accumulation in vivo. Circ Res. 1997;82:30–38. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunkel EJ, Ramos CL, Steeber DA, Muller W, Wagner N, Tedder TF, Ley K. The roles of L-selectin, beta 7 integrins, and P-selectin in leukocyte rolling and adhesion in high endothelial venules of Peyer’s patches. J Immunol. 1998;161:2449–2456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence MB, Bainton DF, Springer TA. Neutrophil tethering to and rolling on E-selectin are separable by a requirement for L-selectin. Immunity. 1994;1:137–145. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence MB, Kansas GS, Kunkel EJ, Ley K. Threshold levels of fluid shear promote leukocyte adhesion through selectins (CD62L,P,E) J Cell Biol. 1997;136:717–727. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence MB, Springer TA. Leukocytes roll on a selectin at physiologic flow rates: Distinction from and prerequisite for adhesion through integrins. Cell. 1991;65:859–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90393-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim YC, Snapp KR, Kansas GS, Camphausen R, Ding H, Luscinskas FW. Important contributions of P-selectin Glycoprotein Ligand-1 mediated secondary capture to human monocyte adhesion to P-selectin, E-selectin, and TNF-a-activated endothelium under flow in vitro. J Immunol. 1998;161:2501–2508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mody NA, Lomakin O, Doggett TA, Diacovo TG, King MR. Mechanics of transient platelet adhesion to von Willebrand factor under flow. Biophys J. 2005;88:1432–1443. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore KL, Patel KD, Bruehl RE, Fugang L, Johnson DA, Lichenstein HS, Cummings RD, Bainton DF, McEver RP. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 mediates rolling of human neutrophils on P-selectin. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:661–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Picker LJ, Warnock RA, Burns AR, Doerschuk CM, Berg EL, Butcher EC. The neutrophil selectin LECAM-1 presents carbohydrate ligands to the vascular selectins ELAM-1 and GMP-140. Cell. 1991;66:921–933. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puri KD, Doggett TA, Douangpanya J, Hou Y, Tino WT, Wilson T, Graf T, Clayton E, Turner M, Hayflick JS, Diacovo TG. Mechanisms and implications of phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta in promoting neutrophil trafficking into inflamed tissue. Blood. 2004;103:3448–3456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz US, Alon R. L-selectin-mediated leukocyte tethering in shear flow is controlled by multiple contacts and cytoskeletal anchorage facilitating fast rebinding events. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6940–6945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305822101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.St Hill CA, Alexander SR, Walcheck B. Indirect capture augments leukocyte accumulation on P-selectin in flowing whole blood. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:464–471. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1002491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yago T, Wu J, Wey CD, Klopocki AG, Zhu C, McEver RP. Catch bonds govern adhesion through L-selectin at threshold shear. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:913–923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]