Abstract

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract (GI) for which treatments with immunosuppressive drugs have significant side-effects. Consequently, there is a clinical need for site-specific and non-toxic delivery of therapeutic genes or drugs for CD and related disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease. The aim of this study was to validate a gene delivery platform based on ultrasound-activated lipid-shelled microbubbles (MBs) targeted to inflamed mesenteric endothelium in the CD-like TNFΔARE mouse model. MBs bearing luciferase plasmid were functionalized with antibodies to MAdCAM-1 (MB-M) or VCAM-1 (MB-V), biomarkers of gut endothelial cell inflammation and evaluated in an in vitro flow chamber assay with appropriate ligands to confirm targeting specificity. Following MB retro-orbital injection in TNFΔARE mice, the mean contrast intensity in the ileocecal region from accumulated MB-M and MB-V was 8.5-fold and 3.6-fold greater, respectively, compared to MB-C. Delivery of luciferase plasmid to the GI tract in TNFΔARE mice was achieved by insonating the endothelial cell-bound agents using a commercial sonoporator. Luciferase expression in the midgut was detected 48 h later by bioluminescence imaging and further confirmed by immunohistochemical staining. The liver, spleen, heart, and kidney had no detectable bioluminescence following insonation. Transfection of the microcirculation guided by a targeted, acoustically-activated platform such as an ultrasound contrast agent microbubble has the potential to be a minimally-invasive treatment strategy to ameliorate CD and other inflammatory conditions.

Keywords: MAdCAM-1, Sonoporation, VCAM-1, Ultrasound, Contrast agents, Gene delivery

1. Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) is an autoimmune disorder that leads to a chronic and debilitating form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The pathogenesis of CD is unknown and likely results from a confluence of genetic and environmental factors [1,2]. Conventional treatment of CD with steroids and other immunosuppressive drugs results in amelioration of acute symptoms, but therapy must be carefully monitored to minimized negative side-effects that are attendant with long-term usage [3,4]. Alternative therapies using biological agents targeted at regulatory elements of the immune system have shown positive clinical outcomes in many cases, and allow respite from some of the negative side effects of long-term steroid use [5–7]. The most widely-used biologics to date have been humanized monoclonal antibodies that block the activity of the cytokine, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [8,9]. In addition, antibodies to cytokines such as IL-23, IL-17, IL-6, and alpha 4 integrin are in clinical trials or have been approved as treatments for CD [10,11]. While promising as therapies, all biologics developed to date have significant drawbacks, including limited efficacy in some patients, risks of adverse immune responses with repeated administration, and high cost [5,11–13]. Gene therapy strategies aimed at addressing the underlying disease components may therefore represent an alternative approach for long-term treatment of CD and IBD.

The intestinal inflammation characteristic of CD is associated with recruitment of naïve lymphocytes into the gut-associated lymphoid tissue [14]. Animal studies suggest that CD in time takes on characteristics of chronic inflammatory disease, such as continuously dysregulated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, overexpression of adhesion molecules such as mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) [13,15], intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) [12,16,17], and in some models, vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) [18,19]. Notably, increased expression of MAdCAM-1 has been reported in the intestinal microvascular endothelium in several CD-like mouse models [20,21], as has VCAM-1 [22].

One approach to molecularly image the vascular inflammation characteristic of CD and IBD is to target ultrasound microbubble contrast agents to receptors on inflamed endothelium. In this approach, microbubbles (MBs), ranging from 2 to 4 µm, are functionalized with antibodies or peptides to endothelial markers such as MAdCAM-1 that then support adhesion to the blood vessel wall in the tissue of interest [21,23,24]. Consequently, contrast (generated by the MB echogenicity) maps to the expression of the respective antigens on the vascular endothelium. One advantage of contrast enhanced ultrasound imaging is that the microbubble's size constrains it to the lumen of the blood vessel and results in rapid clearance by the lung and spleen. Repeated applications should therefore be possible to probe the expression patterns of different antigens [25].

Ultrasound contrast MBs have also been used to sonoporate cells, a process in which acoustic energy induces bubble collapse, generating microjets that create transient pores in the cell membrane. The combination of membrane pore creation and microjet formation facilitates transport of large molecules and nanoparticles into the cell cytoplasm [26–34]. The net result is that an intravascularly administered MB can deliver DNA plasmids, siRNAs, proteins, or conventional drugs to the cells of the blood vessel wall if appropriately activated by ultrasound.

Previously, we have used a targeted MB formulation as an imaging modality to detect and evaluate MAdCAM-1 expression noninvasively in ileitis in a mouse model of chronic intestinal inflammation [21]. Plasmid-bearing untargeted MBs have also been used to deliver genes to the rat hindlimb skeletal muscle [35], achieving luciferase gene transfer by localized application of ultrasound. In this study, MBs were formulated to adhere to the vascular endothelium via the receptors MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1, known to be upregulated in the mesentery of TNFΔARE mice, an animal model of IBD-like disorders. Additionally, the targeted MBs were modified to carry DNA plasmids coding for luciferase, a reporter gene. Using this platform, we demonstrated its ability to detect MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in chronically inflamed mesenteric vasculature of TNFΔARE mice and with ultrasound we initiated targeted transfection of the luciferase plasmid to the diseased intestinal tissue.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Luciferase plasmid

The plasmid pCMV-GL3 was derived from pGL-3 (Promega, Madison, WI). The pCMV-GL3 plasmid drives the expression of the firefly luciferase gene from the CMV promoter, with a molecular weight of 38 kDa. The plasmid was amplified in Epicurian Coli XL10 gold ultracompetent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and then isolated and purified using QIAGEN plasmid giga kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Plasmid concentration was assessed by photometric absorption at 260 nm.

2.2. Cell culture preparation and flow cytometry analysis

Three cell lines were used in this study. SVEC4–10 (murine endothelial cell line derived by SV40 transformation) was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA), and was used to investigate MB adhesion to VCAM-1. SV-LEC, a mouse lymphatic endothelial cell line from the mesenteric adventitial tissue, was generated as described previously [36]. SV-LEC cells express MAdCAM-1 following TNF-α stimulation. SV-LEC cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Invitrogen) in a 95% air–5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. The SVEC4–10 cells were similarly maintained, except for the addition of 10% heatinactivated FBS. The endothelioma line bEND.3 was a gift from Dr. Eugene Butcher and was maintained under identical conditions as SV-LEC cells. For the functional binding flow chamber assay, 35-mm culture dishes (Corning, Corning, NY) were pre-coated with 2 µg/ml fibronectin (Millipore, Temecula, CA) for 3 h at room temperature (RT) and both cell lines were seeded at a density of 1.5×105 cells/mL and grown to confluence. SV-LEC cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 20 ng/mL recombinant murine TNF-α (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 24 h prior to the parallel flow chamber experiment. The presence of VCAM-1 in SVEC4–10 cells and MAdCAM-1 in SV-LEC cells was verified by FACS analysis (data not shown) using Alexa Flour 647-conjugated anti-VCAM-1 (clone: 429, eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or FITCconjugated anti-MAdCAM-1 (clone: MECA-367, eBioscience, San Diego, CA), respectively. bEND.3 cells cultured with 20 ng/mL murine TNF-α were positive for VCAM-1 and MAdCAM-1. All flow cytometry data were analyzed with FLOWjo Software (www.treestar.com/flowjo).

2.3. Targeted plasmid-bearing microbubble preparation

Biotinylated monoclonal murine antibodies against MAdCAM-1 (clone: MECA-367), VCAM-1 (clone: 429), Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647) conjugated mouse anti-Rat IgG and IgG2a isotype control (clone: EBR2a) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). We utilized an experimental MB manufactured by Targeson, Inc. (San Diego, CA), known as TS-02–008 [26]. MBs were composed of a gaseous decafluorobutane core encapsulated by distearoylphophatidylcholine (DSPC), a lipid shell, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) stearate (Supplemental Fig. A). The bubble shell contains a small amount of lipid 1,2-distearoyl-3-trimethylammoniumpropane (DTAP; Avanti, Alabaster, AL) which provides a net positive surface charge. The MB also contains 1% of lipid–PEG–biotin, which enables conjugation of targeting ligands using biotin–streptavidin conjugation chemistry. Conjugation of biotinylated antibodies to the MB was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, anti-MAdCAM-1, anti-VCAM-1 or isotype control antibodies were added at 5 µg per 1×107 MBs, followed by addition of pCMV-GL3 plasmid (20 µg per 1×108 MBs) to MBs being used for gene delivery. MBs were resuspended to a final concentration of 2×107 MB/mL. For the targeted MB construct characterization by FACS analysis, luciferase plasmid-bearing MBs were labeled with the nucleotide-avid fluorophore YOYO-1 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), 1 µg per 1×108 MBs and second staining was conducted with AF647 conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody (5 µg per 1×107 MBs) at a final concentration of 5×106 MB/mL for FACS analysis. To compare the polydisperse MB population with known bead sizes by FACS, some MB samples were incubated with polystyrene microbeads (2.022±0.046 µm and 5.919±0.354 µm from Polyscience, Inc.; Warrington, PA). MB concentration and size distribution were assessed by electrozone sensing using a Coulter Multisizer 4 (Beckman–Coulter, Miami, FL).

2.4. Laminar flow adhesion assay

35-mm nontreated polystyrene Petri dishes (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were used to absorb recombinant murine MAdCAM-1 (rmMAdCAM-1) or VCAM-1 (rmVCAM-1) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) protein at 1 µg/mL for 3 h at RT and blocked as previously described [25]. The experimental flow chamber binding assay setup is shown in Supplemental Fig. B. A commercially available parallel flow chamber (Glycotech, Rockville, MA) was used to modulate wall shear stresses across substrates with recombinant protein or confluent EC monolayers. In some experiments, cells were incubated with neutralizing antibodies at 50 µg/mL for 30 min before adhesion assays to block MAdCAM-1 or VCAM-1. A PHD2000 programmable syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) maintained a continuous wall shear stress of 1.0 dyn/cm2. The flow chamber assembly was mounted over an upright microscope (Orthoplan; Leitz,Wetzlar, Germany) with ×63 objective. MBs were kept in suspension by a magnetic stirrer and infused at a concentration of 5×106 MB/mL in DMEM with 10% FBS. After 4 min of flow, ten fields of view (FOV) were scanned and recorded. Videos from all experiments were captured using a high definition camcorder (HV20; Canon, Easley, SC) and directly stored to the hard drive of a Dell Dimension 8400 (Dell, Austin, TX) using Pinnacle Studio Ultimate software (Mountain View, CA).

2.5. Experimental animal model

The B6.129P-Tnftm2Gkl/Jarn strain generated by over 30 generations of continuous backcrossing to C57BL6/J as previously described [37]. All progeny were either heterozygous to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)ΔAU-rich element (ARE) (TNFΔARE) or carried no mutated alleles, wild-type (WT). The WT mice were used as the non-inflamed controls. TNFΔARE mice develop disease by 8 weeks-of-age that worsens progressively, yet they reach sexual maturity and procreate. Mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions. All in vivo experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia. TNFΔARE and WT mice utilized for all experiments were females between 8 and 10 weeks of age weighing 16–20 g.

2.6. In vivo imaging of targeted microbubble accumulation

All images were acquired with an Acuson Sequoia 512 ultrasound system (Siemens, Issaquah, WA) with a 15L8 high-frequency linear assay transducer (Supplemental Fig. C). Mice were anesthetized by placing each mouse into an induction chamber and introducing 2.5% (v/v) aerosolized isoflurane in oxygen. Once anesthetized, the mouse was placed and secured to a 3-axis linear positioning stage in supine position, equipped with a heated pad set at 37 °C, and maintained on 1% isoflurane in oxygen during the imaging. Ultrasound transmission gel (Aquasonic, Parker Labs, Fairfield, NJ) was used to couple the transducer to the skin surface. The B-mode (14 MHz, MI=0.25) was used to guide the transducer placement to the ileocecum. Nondestructive imaging was performed in cadence contrast pulse sequencing (CPS) mode (8 MHz, MI=0.25, CPS gain=−5, dynamic range=80), MB-M, MB-V or MB-C (50 µL containing 1×107 MBs) was administered as an intravenous (IV) bolus retro-orbital injection to TNFΔARE and WT mice. The CPS image sequence was acquired for 10 min, at which point all unbound MBs had been cleared (Fig. 3). To verify the binding specificity of targeted MBs, a high power destructive pulse was applied (8 MHz; MI=1.9). All images were digitally stored on magneto-optical (MO) disk and transferred onto a personal computer for subsequent off-line analysis using ImageJ (www.rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

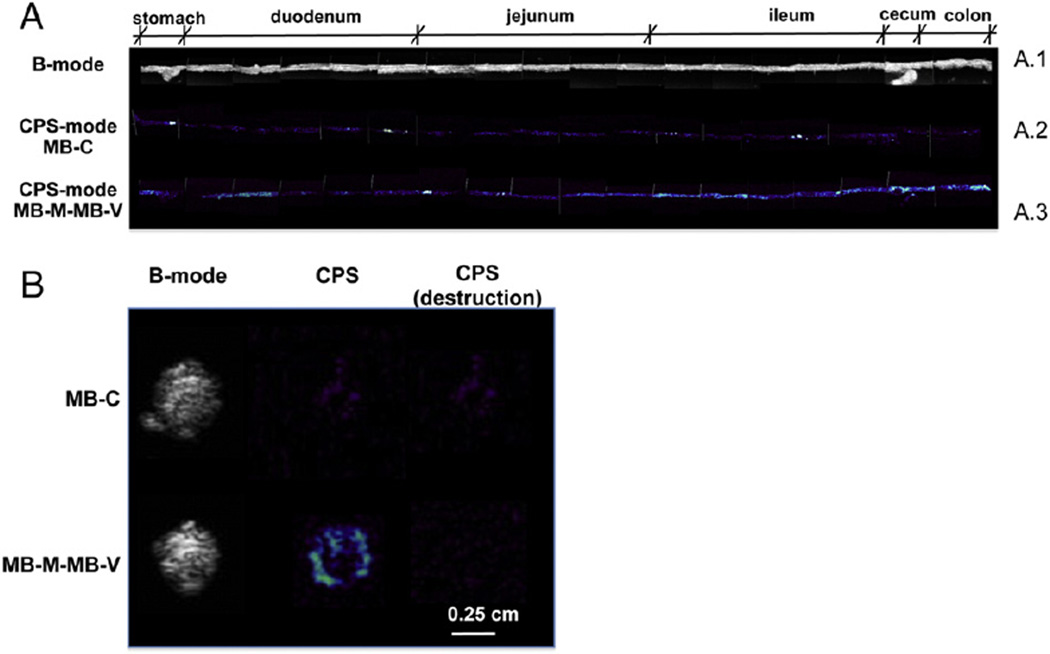

Fig. 3.

Bowel targeted molecular ultrasound imaging mediated by inflammatory biomarkers of endothelial dysregulation in TNFΔARE mice. (A) Contrast ultrasound signal, color-coded in shades of white/green/blue, showing strong signal 30 s post retro-orbital injection of luciferase plasmid-bearing MBs, regions of interest shown in dashed lines. (B) Time course of targeted and control MB accumulation shows complete wash-out of MB-C after 10 min but not from either MB-M or MB-V. (C) Mean intensity signal 10 min post injection from MB-C, MB-V or MB-M in TNFΔARE or WT mice.

2.7. Ex vivo imaging of microbubble accumulation

A 3-axis linear stage equipped with a stepping motor controller (Velmex, Inc., Bloomfield, NY) was employed for the ex vivo targeting images (Supplemental Fig. D). A single dose of MB-M and MB-V (1×107 MBs per type) were administered into the TNFΔARE mice with 10 minute dwell time between doses. Subsequently, mice were euthanized, and the GI tract (stomach to colon, ∼35 cm in length) was isolated and mounted in a saline bath (0.9% NaCI solution in degassed distilled water) at 20 °C. The 15L8 transducer was mechanically fixed approximately 0.5 cm above the GI tract and moved along the length every 2 cm with the positioning device controller. The B-mode imaging was used for anatomical visualization along the GI tract segment (Fig. 4A.1), while CPS mode imaging verified accumulation of MB-M– MB-V (Fig. 4A.3) or MB-C (Fig. 4A.2).

Fig. 4.

Biodistribution of membrane markers of endothelial cell inflammation assessed by accumulation of MB-M–MB-V in the GI tract of TNFΔARE mice. Targeted plasmid-bearing MB-M and MB-V were injected intravenously. The GI tract was imaged for accumulation of MBs in the bowel with the ultrasound transducer in CPS mode (8 MHz, MI=0.25, CPS gain=−5, dynamic range=80). (A) Ex vivo imaging of the GI tract (stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum and colon) in B- (A.1) and CPS-modes of MB-M–MB-V (A.3) and MB-C (A.2). (B) Cross-sectional ultrasound images of ileum in B- and CPS-modes of MB-M–MB-V and MB-C, approximately 30 cm from the stomach.

2.8. Targeted transfection of luciferase plasmid in vivo

We previously explored the transfection efficiency of a model plasmid in vitro [26], and used this work to guide our in vivo conditions. A SP-100 sonoporator (Sonidel, Ltd., Dublin, Ireland) was used to produce varying ultrasound power intensities (0.3, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4 and 5 W/cm2) at a center frequency of 1.0 MHz applied transabdominally. The transducer was placed above the abdomen with ultrasound coupling gel, and was translated across the entire bowel region at approximately 50 mm/s. Transfection efficiency was evaluated by bioluminescence imaging 48 h post-treatment. A preliminary study revealed that 5 W/cm2 at 25% duty cycle for 5 min produced the greatest transfection efficiency (data not shown), and these conditions were used for all studies reported here unless otherwise noted. Our previous results suggested that all MBs within the beam were destroyed under these conditions, which appears to be a necessary condition for release of the plasmid and its eventual expression [26]. MB-M, MB-V, MB-M– MB-V or MB-C, all bearing luciferase plasmid, were administered to mice by retro-orbital injection. Accumulation of MBs in the ileocecal region was monitored by non-destructive ultrasound imaging for 10 min as described above. Immediately after US imaging, the entire bowel region was insonated. For the combined MB-M–MB-V dose MB-M was administered first followed by insonation, followed by a dose of MB-V. Full destruction of the MBs was verified by the absence of the contrast US signal.

2.9. Noninvasive real-time in vivo bioluminescence imaging

Mice were anesthetized and maintained on 1% isoflurane in oxygen and subsequently received an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of an aqueous solution of D-luciferin at 125 mg/kg body weight (Xenogen, Alameda, CA). Eight minutes following D-luciferin administration, mice were imaged using Xenogen IVIS100. Images were acquired for 5 min with a 15 cm field of view (FOV), binning factor of 8 and 1/f stop. For ex vivo bioluminescence imaging, mice were euthanized and the GI tract, liver, kidney, spleen and heart were isolated, kept on ice, dipped in D-luciferin for 2 min (all at the same time) just before being imaged. Images were processed using Xenogens' Living Image software (Xenogen) and presented as luminescence intensities (photons/s/cm2/sr) or total flux (photons/s).

2.10. MAdCAM-1, VCAM-1 and luciferase immunohistochemical detection

Forty-eight hours post last US treatment, mice were anesthetized and euthanized. The GI tract was isolated and dipped in D-luciferin for ex vivo bioluminescence imaging. The ileal region showing bioluminescence signal (5 mm length approx.) was separated and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Five micrometer-thick cryostat sections were fixed in ice-cold acetone: ethanol (1:1 ratio) and stained with mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against MAdCAM-1 (eBioscience, clone: MECA-367), VCAM-1 (eBioscience, clone: 429), luciferase (Sigma, Clone: LUC-1) and rabbit polyclonal antibody against PECAM-1 (CD31) (Abcam). All slides were stained on a DAKO Autostrainer (DAKO Corp., Capenteria, CA). Endogenous peroxidases were blocked using peroxidase blocking reagent (DAKO). Luciferase antibody staining was performed following the manufacturer's protocol. MAdCAM-1,VCAM-1 and luciferase antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin. PECAM-1 (CD31) antibody was detected with DAKO Envision Dual Link. Diaminobenzidine was used as a substrate and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with permanent mounting medium. Images were collected using an Olympus BX41 microscope with × 20 or × 40 objectives coupled with an Olympus DP71 digital camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

2.11. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), unless otherwise noted. All differences were evaluated by using the two-tailed Student's t-test, with P<0.05 considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise stated, each independent sample consists of one culture Petri dish or animal.

3. Results

3.1. Ultrasound contrast agent (MB) characterization

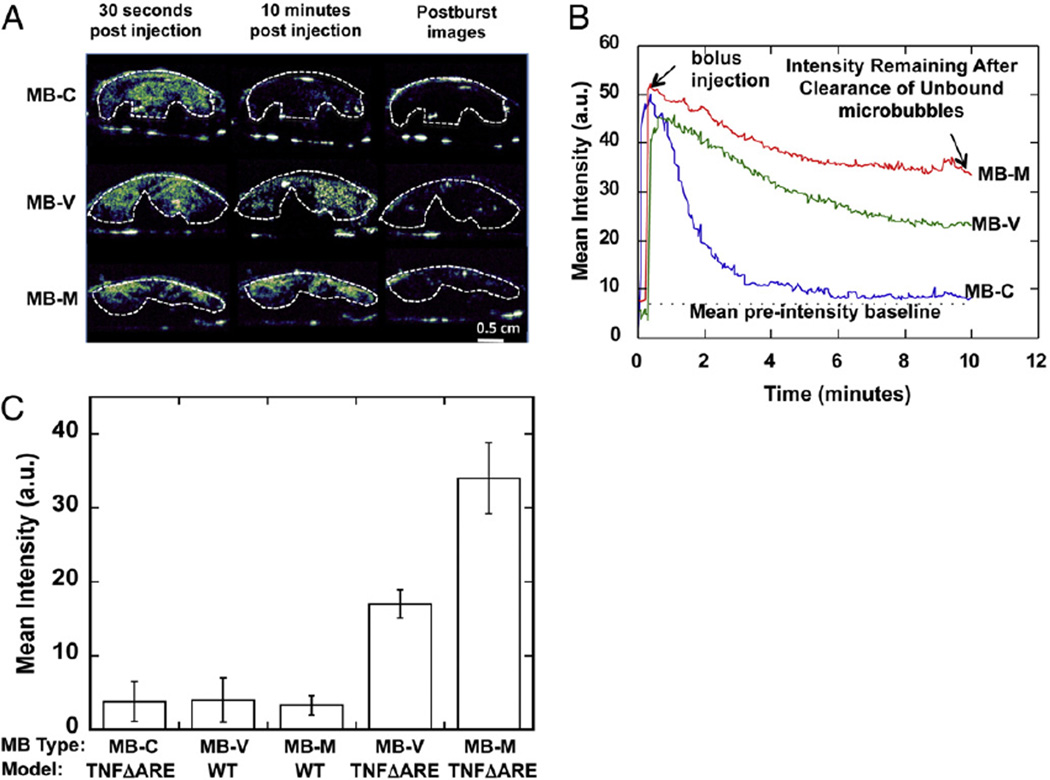

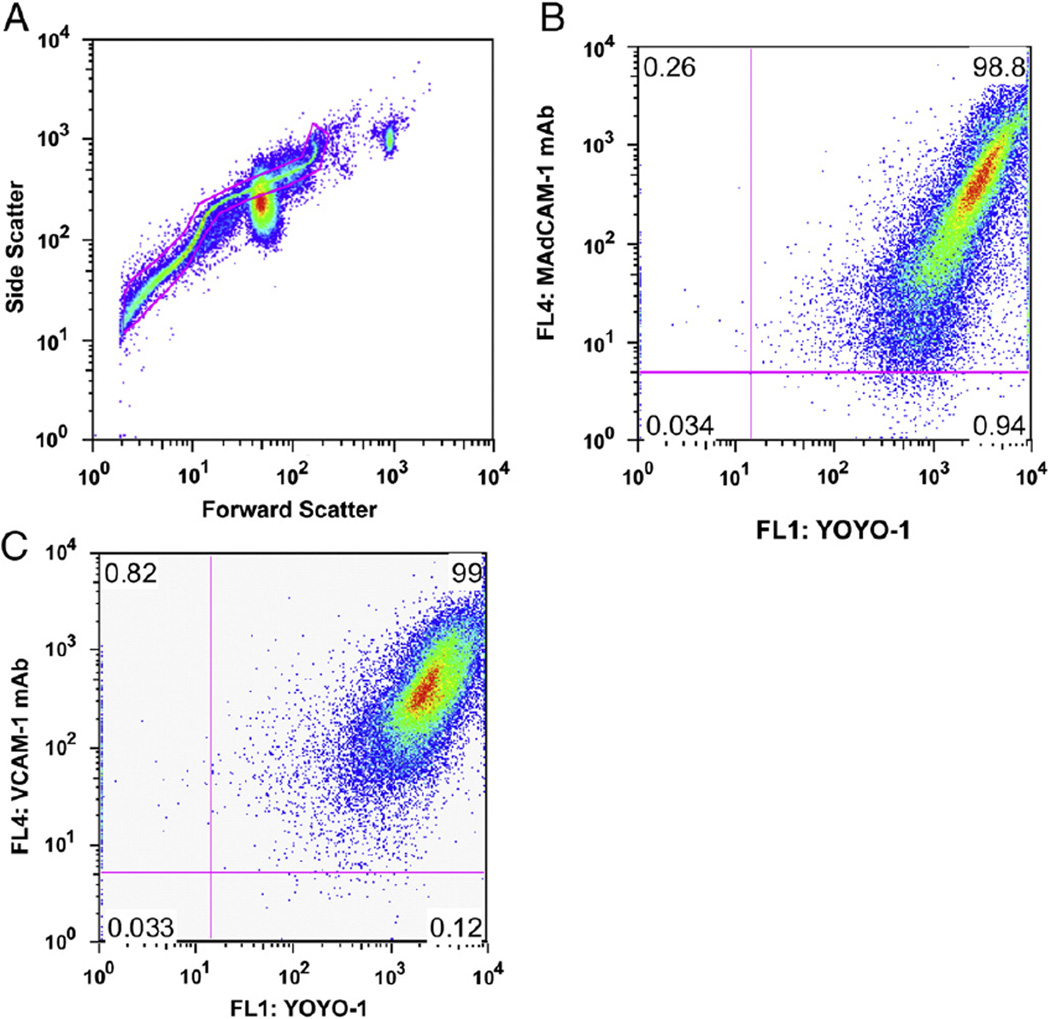

A sigmoidal forward-side scatter plot, characteristic of polydisperse gas-encapsulated MBs [26,38], was observed by flow cytometry (FACS) analysis (Fig. 1A). Based on the forward scatter results from the polystyrene microbeads, the MBs were less than 6 µm in (Fig. 1A). Single stain-positive control samples used to determine compensation and quadrants were prepared as follows: MBs were conjugated with VCAM-1 antibodies and then detected with AF647-conjugated secondary antibody or YOYO-1 labeled plasmid alone. A low-level background fluorescence signal for naked cationic MBs was observed (data not shown), while a strong fluorescence signal was observed for luciferase plasmid-bearing MBs coupled with MAdCAM-1 (Fig. 1B) or VCAM-1 antibodies (Fig. 1C). An antibody concentration of 5 µg per 107 MBs translated to approximately 200,000 antibody molecules per MB [39] and spectrophotometric measurements at 260 nm revealed a maximum payload of 4 µg of plasmid per 108 MB as previously described [35]. The mean diameter of the targeted MB was 1.8± 0.54 µm as measured by electrozone sensing with a Coulter counter (Supplemental Fig. E).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of targeted MB construct by flow cytometry analysis. Plasmid DNA was electrostatically coupled to the cationic MBs and labeled with YOYO-1. Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody to detect the biotinylated mAbs. (A) Forward vs. side scatter of MB-V bearing luciferase plasmid labeled with YOYO-1 and antibody conjugated to the MB shell, with a gate showing the population of MBs analyzed to be under 6 µm in diameter. (B) Dot-plots for MB-M and (C) MB-V show a significant fluorescent signal from plasmid and antibodies against MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1 coupled to the MB shell, respectively.

3.2. Targeted microbubbles under physiological shear flow conditions

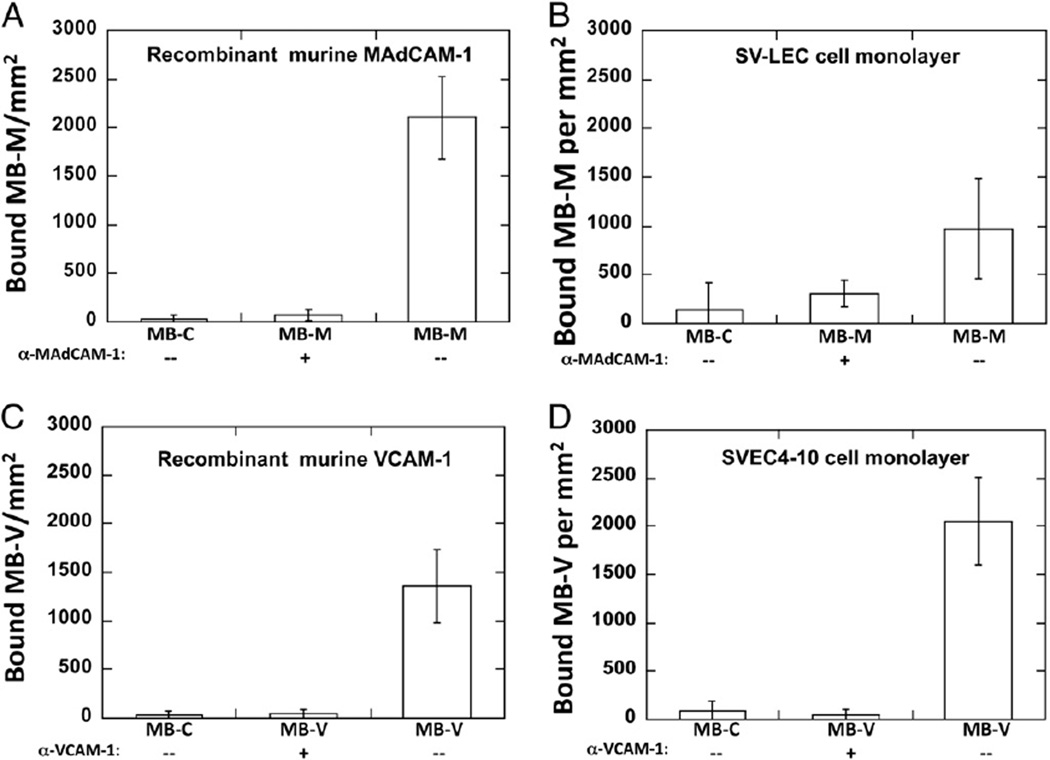

To validate plasmid-bearing MB adhesion to molecular targets, we analyzed MB adhesion on recombinant proteins and EC monolayer substrates (SVEC4–10 for VCAM-1 expression and SV-LEC for MAdCAM-1 expression, respectively) using a parallel-plate flow chamber. All SVEC4–10 cells constitutively express VCAM-1, while ∼20% of TNF-α stimulated SV-LEC cells express Mad CAM-1, both verified by FACS analysis (data not shown). As a negative control, we conjugated an isotype antibody that has no relevant specificity to help distinguish non-specific adhesion levels. Under a physiological wall shear stress (1 dyn/cm2), a 75 and 6-fold increase in the number of bound MB-M per mm2 relative to the MB-C was observed on rmMAdCAM-1 and SV-LEC monolayer substrates, respectively, (Fig. 2A and B). Substrates pre-treated with α-MAdCAM-1 antibodies abrogated binding from 75 to 97%. Similar results were observed on the number of MB-V bound to rmVCAM-1 and SVEC4–10 cell monolayers, 47 and 25-fold increase respectively, relative to MB-C (Fig. 2C and D). Similarly, the addition of anti-VCAM-1 antibodies abrogated MB-V–substrate binding. MB-C binding in flow to bEND.3 (34±29 MB-C/mm2) was comparable to binding to of MB-C to SV-LEC (115±23 MB-C/mm2) and SVEC4–10 (76±19 MB-C/mm2) at 1 dyn/cm2 wall shear stress (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Functional evaluation of targeted MBs to recombinant murine MAdCAM-1 (rmMAdCAM-1) and VCAM-1 (rmVCAM-1) and cultured EC monolayers expressing MAdCAM-1 or VCAM-1. Quantitative evaluation under continuous flow conditions demonstrated specificity for MB-M to rmMAdCAM-1 (A) and SV-LEC monolayers (B). MB-V for rmVCAM-1 (C) and SVEC4–10 monolayers (D). Incubating substrates with anti-MAdCAM-1 or anti-VCAM-1 antibodies abrogated targeted MB binding; minimal binding was observed with MB-C.

3.3. Verification of microbubble retention in vivo by ultrasound imaging

Having determined targeted MBs' binding to recombinant proteins and EC monolayer substrates in vitro, we next evaluated intravascular binding of MB-M and MB-V in vivo using the TNFΔARE mouse model. Ultrasound images were recorded before (pre-contrast baseline) and after (post-contrast) the MB injection. After the bolus injection, there was a rapid increase in the MB concentration in the ileocecal region, followed by a slow wash-out of circulating MB over 10 min (Fig. 3A). This behavior manifests as a steady-state plateau in the time–intensity curve, indicating retention of MBs (Fig. 3B). Minimum retention was observed with MB-C. We further validated that the contrast signal observed at 10 min corresponded to adherent MBs, not circulating, by applying a destructive pulse which destroyed all MBs with in the beam. No replenishment of the contrast signal was observed within few seconds after the destructive burst, suggesting that the observed signal was due to adherent MBs. The intensity signals of adherent MB-M and MB-V were approximately 8.5-fold and 3.6-fold greater than MB-C, respectively (Fig. 3C) in TNFΔARE mice, and close to the baseline level in WT mice receiving MB-M or MB-V. These results demonstrate selective targeting to specific endothelium receptors present under this pathological condition.

3.4. Ex vivo imaging of microbubble accumulation in the GI tract

The bowel presents a complex anatomy in situ and scale of the mouse organ presents additional difficulty in precisely identifying locations of inflammation. In order to further characterize the regions of MB accumulation inTNFΔARE mice, we harvested the bowel for ex vivo imaging of the entire GI tract following accumulation of MB-M–MB-V (Fig. 4A.1). These MBs accumulated along the GI tract (Fig. 4A.3), identifying sites of local up-regulation of cell adhesion molecules in the duodenum, ileum and colon macrovasculature. Minimum non-specific accumulation was observed with MB-C (Fig. 4A.2). After a high-power destructive pulse, no contrast enhancement was observed in the isolated bowel, further validating the specificity of MB-M–MB-V (Fig. 4B).

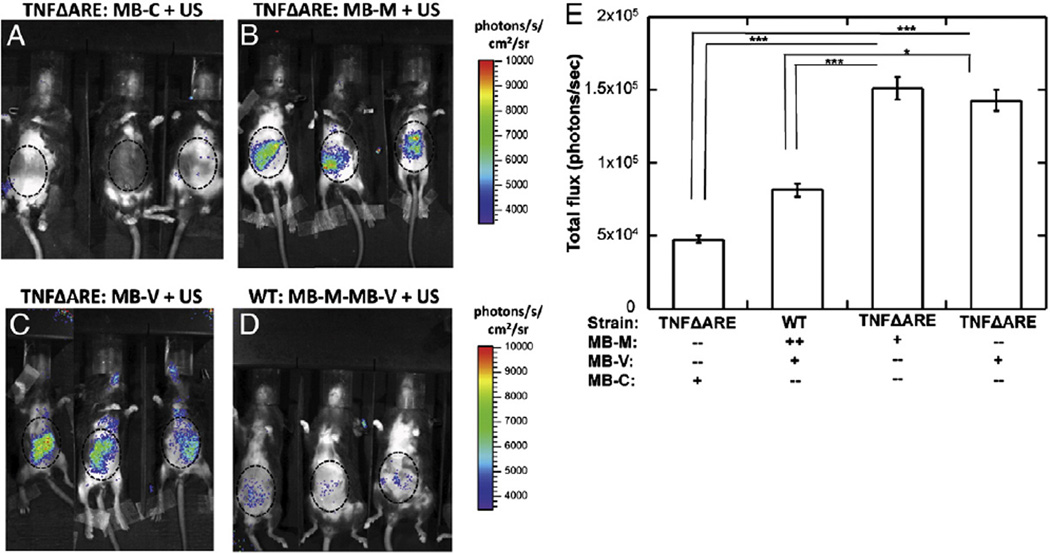

3.5. Microbubble-mediated delivery of luciferase plasmid

In vivo bioluminescence imaging revealed that luciferase expression was evident within the lower abdominal cavity at 2 days after the vector administration. A single dose of MB-M or MB-V in TNFΔARE mice provided detectable bioluminescent signal (Fig. 5B and C), with minimum signal from controls (TNFΔARE mice administered MB-C (Fig. 5A) or WT mice administered with both MB-M and MB-V (Fig. 5D)). Quantitation of the photon flux indicated approximately equal levels of bioluminescence generated by MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1 targeted MBs. WT mice treated with MB-V and MB-M had significantly lower levels of biolumi-nescence, consistent with a lower level of inflammation suggested by the lower level of MB-V and MB-M binding detected by ultrasound.

Fig. 5.

Bioluminescence imaging from TNFΔARE and WT mice. MBs were administered via retro-orbital injection, followed by acoustic treatment with a Sonidel sonoporator. Forty-eight hours after US treatment mice were anesthetized and administered D-luciferin substrate by intraperitoneal (IP) injection. Eight minutes following D-luciferin administration, mice were imaged for luciferase activity using an IVIS100 system. Bioluminescence images from TNFΔARE mice receiving (A) MB-C, (B) MB-M, (C) MB-V or (D) WT mice administered a combination of MB-M and MB-V. (E) Bioluminescence signal quantified and plotted as total flux in the ileocecal region, revealed significantly higher levels of luciferase activity in TNFΔARE mice receiving MB-M or MB-V. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

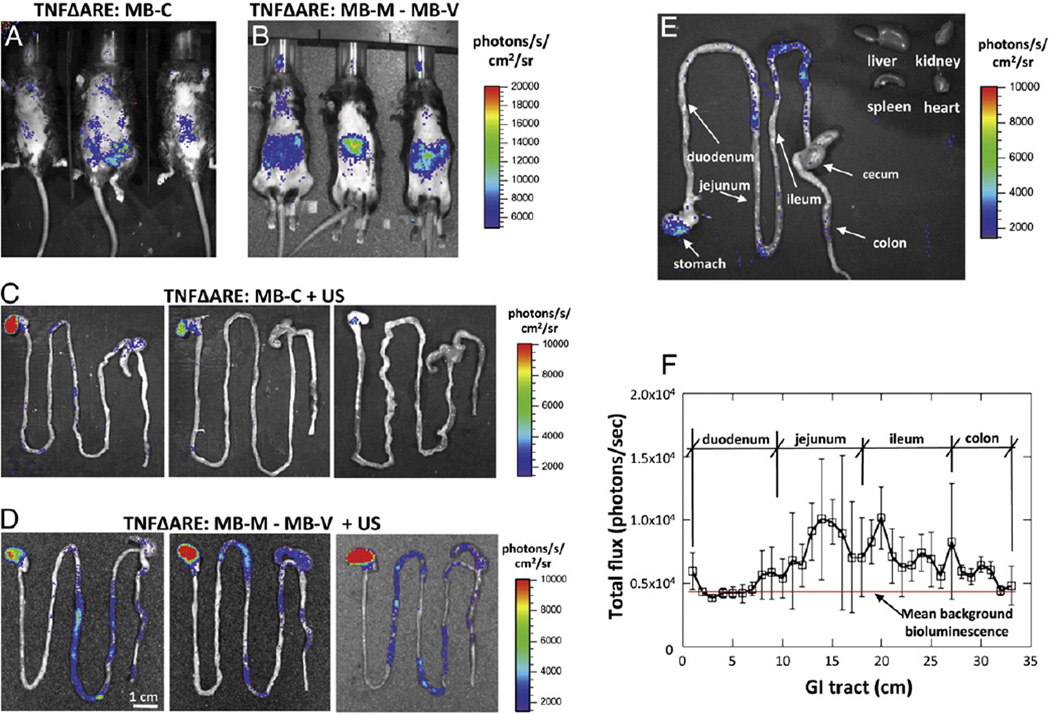

For ex vivo imaging of isolated organs, mice were treated for 4 days, receiving daily single dose injections of MB-M and MB-V followed by acoustic treatment to transfect the luciferase reporter gene. Two days after the fourth treatment ex vivo bioluminescence imaging revealed significant luciferase activity in the TNFΔARE treated with MB-V and MB-M (Fig. 6B) higher than that found with MB-C treatments (Fig. 6A). Examination of the GI track ex vivo indicated low levels in the TNFΔARE mice treated with MB-C (Fig. 6C) and significant levels in the stomach, jejunum and ileum (Fig. 6D). The pattern of bioluminescence was non-uniform, possibly indicative of region variations in inflammation. We observe minimal bioluminescence in the liver, kidney, spleen and heart (Fig. 6E). In mice that received MB-M–MB-V, bioluminescence was mainly found in the stomach, jejunum and ileum, with no expression in the liver, kidney, spleen or heart. Furthermore, bioluminescence was also quantified and plotted as total flux (photons/s) along the GI tract (Fig. 6F). Direct examination of those images revealed higher signal differences in the jejunum and ileum, but not in the duodenum nor from TNFΔARE mice receiving MB-C (Fig. 6C). These data suggested that luciferase gene expression was restricted to the GI tract following intravenous administration of the targeted non-viral vector.

Fig. 6.

Bioluminescence imaging from TNFΔARE mice receiving multiple daily doses of MB-M–MB-V or MB-C (1×107 per dose) followed by acoustic treatment. Accumulated MBs were insonated with the sonoporator. (A) Mice were administered a total of eight bolus injections of MB-C (A) or MB-M followed by MB-V (B), a total of two per day with 10 minute dwell time between doses. Ex vivo bioluminescence images from the isolated GI tract from mice receiving MB-C (C) or MB-M and MB-V (D). (E) Ex vivo bioluminescence imaging of isolated GI tract, liver, kidney, spleen and heart. (F) Bioluminescence signal quantified and plotted as total flux along the GI tract, revealed significantly higher levels of luciferase activity in the jejunum and ileum.

3.6. Immunohistochemistry

Significant MAdCAM-1 expression was observed in TNFΔARE mice (Fig. 7C), with significantly less observed in WT mice (Fig. 7A). Less VCAM-1 than MAdCAM-1 expression was apparent in TNFΔARE mice (Fig. 7D), with no VCAM-1 detectable in WT mice (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Histological analysis of frozen ileum sections for MAdCAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM-1 and luciferase expressions post treatment, as per Materials and methods section. Prior to ex vivo bioluminescent imaging, mice were euthanized, the isolated GI tract was dipped in D-luciferin for 2 min and imaged for 5 min in the IVIS100 system. Bioluminescent activity in ilea was identified and collected for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. (A) MAdCAM-1 and (B) VCAM-1 expressions in WT mice (arrows)(×20). (C) MAdCAM-1 and (D) VCAM-1 expressions in ileum of TNFΔARE mice (×20). (E) IHC staining for PECAM-1 (endothelial-specific marker) (×40) and (F) luciferase expression in endothelial vasculature (×40).

We used immunohistochemical staining (IHC) of luciferase to further examine expression of the delivered transgene (Fig. 7F) in the ileum. Our IHC staining data suggest that luciferase and PECAM-1 expressions co-localize in consecutive cryostat sections (Fig. 7E, F).

4. Discussion

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic autoimmune disorder of the GI tract with no known cure. Current medical approaches to treat CD are associated with side effects that in some cases severely compromise patient health [5,7]. In this study, we investigated a cell-specific nonviral gene delivery technique mediated by ultrasound and DNAcarrying receptor-targeted microbubbles (MBs). Our data suggest that the functionalized MB was able to 1) carry a detectable payload of plasmid, 2) adhere specifically to inflamed mesenteric endothelium, and 3) subsequently mediate delivery of the DNA payload upon application of ultrasound energy. Receptor and cell selectivity of MBs targeted to MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1 was verified by non-invasive ultrasound imaging and delivery of the reporter transgene was confirmed by whole-body bioluminescent imaging and immunostaining. Molecularly targeted MBs carrying a therapeutic transgene payload may therefore be a viable delivery technique for integrated diagnosis and treatment of Crohn's disease and other pathologies involving inflamed, damaged, or dysregulated vascular endothelium.

A challenge facing many targeted therapies is that while molecularly specific, they may lack sufficient tissue selectivity to ensure an adequate degree of safety and effectiveness. In particular, as different organ systems share a number of common surface receptor types and even cell signaling pathways, it may be difficult to control off-target effects and delivery to non-diseased tissues [40]. To address this challenge, we integrated two approaches for targeting: a physical approach based on control of the placement of the ultrasound activating beam and a molecular approach where the ligands on the MB controlled adhesion to vascular endothelial cells via specific receptors.

We first assessed the molecular specificity of MB retention in the TNFΔARE mouse gut inflammation model by ultrasound imaging prior to activation of gene delivery (sonoporation). Effectively, we ‘guided’ delivery of the reporter gene by utilization of the MB platform's echogenicity and image contrast. Sonoporation of the inflamed mesentery of the TNFΔARE mice ultimately leads to expression of luciferase in discrete regions of the mesenteric endothelium without detectable transduction in the liver, kidneys, spleen or heart. Despite the administration of ultrasound over the entire intestinal volume, transfection only took place where there were high concentrations of either VCAM-1 or MAdCAM-1 on the mesenteric endothelium.

Due to the receptor specificity of MB binding to the vessel wall we were able to observe a punctate pattern of MAdCAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in the mesentery, suggestive of a complex and regional pattern of disease. Conventional assessment of Crohn's and IBD using various biomarkers offers no such insight into the localized nature of the inflammatory response, nor how sub-regions of the mesentery might respond to targeted therapies. The punctate pattern of VCAM-1 and MAdCAM-1 expression further suggested that receptor specific therapy would primarily target diseased tissue rather than healthy bystander tissue.

Previous studies have described gene delivery approaches in which non-targeted MBs are co-administered with the transgene in the fluid phase followed by ultrasound treatment [29,31,41–43]. Additionally, several studies have utilized a non-targeted cationic MB similar to that described in this study in which DNA plasmids were conjugated by electrostatic binding [35,44,45]. While transduction of the reporter gene was detected in the tissue, expression was not limited to diseased tissue. Furthermore, delivery depended on permeabilization or in some cases rupture of the blood vessel wall [29,44,46–48]. Although we have not directly compared the efficiency of our targeted and payloadbearing MB with either of the previously reported methods, our results suggest that our formulation enabled molecularly-specific transfection of a regional vascular bed with minimal off-target delivery.

To maximize tissue specific DNA delivery and minimize vascular damage, we lowered the applied acoustic energy compared to previous work to a point at which in vitro studies suggested would limit long-term mechanical disruption of the endothelial cell membrane [26,49]. The lower energy we used for in vivo ultrasound MB activation did not appear to result in vessel rupture as suggested by the lack of extravasated erythrocytes in the mesentery and the absence of local thrombosis in histologic studies (Fig. 7). Based on immunohistochemical analysis, the expression of the delivered reporter gene luciferase matched well to endothelial cell CD31/PECAM-1 expression, suggesting that the targeted endothelium was viable 48 h post-sonoporation and able to express the luciferase gene. Nevertheless, more complete studies are needed to fully assess the potential damage to and long-term effects on the target endothelial cells [50].

Ultrasound mediated gene transfer to the endothelium not only creates unique opportunities for delivery of therapeutic proteins [51], it also creates unique concerns regarding the potential for vascular damage. Microbubble collapse generates short-range (micron-scale) fluid jets that transiently permeabilize the target cell's membrane, allowing transport of large molecules such as DNA or proteins. Scanning electron microscopy indicates pore sizes ranging from 40 to 75 nm that rapidly reseal (<1 min) [52]. In contrast, gene or drug delivery by nanoparticles into the target cell is by endocytosis [50,53]. A concern that must be addressed in the future is the extent of the endothelial response to the ‘trauma’ of membrane perturbation and gene delivery. While any number of delivery strategies face these concerns, the microbubble delivery approach may offer the potential advantage of highly localized effects that can be tuned by targeting and placement of the ultrasound beam that minimize systemic risks to the organism.

Diagnostic imaging using MBs with lipid shells similar to the ones described in this study are in wide clinical use and have an excellent safety record. In the United States, their use is generally restricted to visualization of cardiac wall motion, although applications involving monitoring microcirculatory blood flow are approved in the European Union. It should be noted that targeted MB agents such as the one described in this study have not been approved for diagnostic use, although these agents are widely used in the context of preclinical research [54–56].

There are several limitations to our study. Although we were able to demonstrate an 8.5-fold increase in acoustic intensity in the ileocecal region using a single dose of MB-M when compared to MB-C (Fig. 3C), multiple doses of targeted MBs were required before it was possible to detect luciferase expression by conventional histologic methods (Fig. 5E). Additionally, we utilized biotin–streptavidin coupling chemistry for conjugation of targeting ligands. This technique is robust and eminently useful for proof-of-concept studies but is not translatable to clinical use due to the presence of the streptavidin component. Covalent linkages could likely supplant the biotin–avidin linkage. Likewise, the targeting ligands used here (monoclonal antibodies raised in rat) are not translatable and would need to be replaced with more biocompatible ligands. Nevertheless, imaging MBs bearing clinically-translatable ligands and conjugation strategies are, however, available for preclinical use [54,55] and are being actively developed for clinical use [57].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by a NIH Bioengineering Research Partnership EB002185. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Patcharin Pramoonjago and Angela Miller from the Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility at the University of Virginia for their assistance in the immunohistochemical staining. The authors also thank Sonidel LTD for equipment support and Dr. J. Steven Alexander (Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Louisiana State University Health Science center, Shreveport, LA) for providing the SV-LEC cell line. Dr. J. Rychak and Dr. A. Klibanov report stock ownership in Targeson, LLC.

Abbreviations

- AU

arbitrary units

- CD

Crohn's disease

- EC

endothelial cell

- GALT

gut-associated lymphoid tissue

- GI

gastrointestinal

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IV

intravenous

- IHC

immunohistochemical

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- MAdCAM-1

mucosal addressin cellular adhesion molecule-1

- MBs

microbubbles

- MB-M

plasmid-bearing targeted microbubbles to MAdCAM-1

- MB-V

plasmid-bearing targeted microbubbles to VCAM-1

- MB-C

plasmid-bearing control microbubbles

- rmMAdCAM-1

recombinant murine MAdCAM-1

- ROI

region of interest

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- IP

intraperitoneal

- UCA

ultrasound contrast agents

- US

ultrasound

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- rmVCAM-1

recombinant murine VCAM-1

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.10.021

References

- 1.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006;3:390–407. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melum E, Franke A, Karlsen TH. Genome-wide association studies—a summary for the clinical gastroenterologist. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5377–5396. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pithadia AB, Jain S. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Pharmacol. Rep. 2010;63:629–642. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier J, Sturm A. Current treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3204–3212. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i27.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombel J-F, Sandborn WJ, Reinish W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D'Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL, Tang KL, van der Woude CJ, Rutgeerts P, Group SS. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Assche G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG. Daclizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody to the interleukin 2 receptor (CD25), for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, dose ranging trial. Gut. 2006;55:1568–1574. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.089854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wirtz S, Neurath MF. Inflammatory bowel disorders: gene therapy solutions. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2003;5:495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen RD. The pharmacoeconomics of biologic therapy for IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;7:103–109. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blam ME, Stein RB, Lichtenstein GR. Integrating anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: current and future perspectives. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1977–1997. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kopf M, Bachmann MF, Marsland BJ. Averting inflammation by targeting the cytokine environment. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:703–718. doi: 10.1038/nrd2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melmed GY, Targen SR. Future biologic targets for IBD: potentials and pitfalls. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;7 doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allez M, Vermeire S, Mozziconacci N, Michetti P, Laharie D, Louis E, Bigard M-A, Hebuterne X, Treton X, Kohn A, Marteau P, Cortot A, Nichita C, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P, Lemann M, Colombel J-F. The efficacy and safety of a third anti-TNF monoclonal antibody in Crohn's disease after failure of two other anti-TNF antibodies. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;31:92–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan AC, Carter PJ. Therapeutic antibodies for autoimmunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:310–316. doi: 10.1038/nri2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller WA. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in leukocyte transmigration and the inflammatory response. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briskin M, Winsor-Hines D, Shyjan A, Cochran N, Bloom S, Wilson J, McEvoy LM, Butcher EC, Kassam N, Mackay CR, Newman W, Ringler DJ. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, Van Assche G. Biological therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1182–1197. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh S, Panaccione R. Anti-adhesion molecule therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2010;3:239–258. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10373176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Physiologic basis for novel drug therapies used to treat inflammatory bowel disease I. Immunology and therapeutic potential of antiadhesion molecule therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G169–G174. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00423.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawa Y, Shibata K, Braithwaite MW, Suzuki M, Yoshida S. Expression of immunoglobulin superfamily members on the lymphatic endothelium of inflamed human small intestine. Microvasc. Res. 1999;57:100–106. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivera-Nieves J, Gorfu G, Ley K. Leukocyte adhesion molecules in animal models of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1715–1735. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmann C, Klibanov AL, Olson TS, Sonnenschein JR, Rivera-Nieves J, Cominellii F, Ley K, Lindner JR, Pizarro TT. Targeting mucosal addressin cellular adhesion molecule (MAdCAM)-1 to noninvasively image experimental Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:8–16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chosa M, Soeta S, Ichihara N, Nishita T, Asari M, Matsumoto S, Amasaki H. Pathomechanism of cellular infiltration in the perivascular region of several organs in the SAMP1/Yit mouse. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009;7:1553–1560. doi: 10.1292/jvms.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warram JM, Sorace AG, Saini R, Umphrey HR, Zinn KR, Hoyt K. A triple-targeted ultrasound contrast agent provides improved localization to tumor vasculature. J. Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:921–931. doi: 10.7863/jum.2011.30.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weller GE, Lu E, Ciskari MM, Klibanov AL, Fischer D, Wagner WR, Villanueva F. Ultrasound imaging of acute cardiac transplant rejection with microbubbles targeted to intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Circulation. 2003;108:218–224. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080287.74762.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernot S, Klibanov AL. Microbubbles in ultrasound-triggered drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008;60:1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tlaxca JL, Anderson CR, Klibanov AL, Lowrey B, Hossack JA, Alexander JS, Lawrence MB, Rychak JJ. Analysis of in vitro transfection by sonoporation using cationic and neutral microbubbles. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2010;36:1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bekeredjian R, Chen S, Frenkel PA, Grayburn PA, Shohet RV. Ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction can repeatedly direct highly specific plasmid expression to the heart. Circulation. 2003;108:1022–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084535.35435.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinoshita M, Hynynen K. Intracellular delivery of Bak BH3 peptide by microbubbleenhanced ultrasound. Pharm. Res. 2005;22:716–720. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-2586-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leong-Poi H, Kuliszewski MA, Lekas M, Sibbald M, Teichert-Kuliszewska K, Klibanov AL, Stewart DJ, Lindner JR. Therapeutic arteriogenesis by ultrasoundmediated VEGF165 plasmid gene delivery to chronically ischemic skeletal muscle. Circ. Res. 2007;101:295–303. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li YS, Reid CN, McHale AP. Enhancing ultrasound-mediated cell membrane permeabilisation (sonoporation) using a high frequency pulse regime and implications for ultrasound-aided cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehier-Humbert S, Bettinger T, Yan F, Guy RH. Ultrasound-mediated gene delivery: kinetics of plasmid internalization and gene expression. J. Control. Release. 2005;104:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller DL, Bao S, Gies RA, Thrall BD. Ultrasonic enhancement of gene transfection in murine melanoma tumors. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 1999;25:1425–1430. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otani K, Yamahara K, Ohnishi S, Obata H, Kitamura S, Nagaya N. Nonviral delivery of siRNA into mesenchymal stem cells by a combination of ultrasound and microbubbles. J. Control. Release. 2009;133:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rahim A, Taylor SL, Bush NL, ter Haar GR, Bamber JC, Porter CD. Physical parameters affecting ultrasound/microbubble-mediated gene delivery efficiency in vitro. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2006;32:1269–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christiansen JP, French BA, Klibanov AL, Kaul S, Lindner JR. Targeted tissue transfection with ultrasound destruction of plasmid-bearing cationic microbubbles. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2003;29:1759–1767. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(03)00976-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ando T, Jordan P, Joh T, Wang Y, Jennings MH, Houghton J, Alexander JS. Isolation and characterization of a novel mouse lymphatic endothelial cell line: SV-LEC. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2005;3:105–115. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2005.3.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho J, Kurtz CC, Naganuma M, Ernst PB, Cominellii F, Rivera-Nieves J. A CD8+/CD103high T cell subset regulates TNF-mediated chronic murine ileitis. J. Immunol. 2008;180:2573–2580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feshitan JA, Chen CC, Kwan JJ, Borden MA. Microbubble size isolation by differential centrifugation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;329:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrante EA, Pickard JE, Rychak JJ, Klibanov AL, Ley K. Dual targeting improves microbubble contrast agent adhesion to VCAM-1 and P-selectin under flow. J. Control. Release. 2009;140:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torchilin VP, Muzykantov VR. Strategies and means for drug targeting: an overview. In: Muzykantov VR, Torchilin VP, editors. Biomedical Aspects of Drug Targeting. Boston/Dordrecht/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2010. pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawrie A, Brisken AF, Francis SE, Cumberland DC, Crossman DC, Newman CM. Microbubble-enhanced ultrasound for vascular gene delivery. Gene Ther. 2000;7:2023–2027. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bekeredjian R, Chen S, Grayburn PA, Shohet RV. Augmentation of cardiac protein delivery using ultrasound targeted microbubble destruction. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2005;31:687–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pislaru SV, Pislaru C, Kinnick RR, Singh R, Gulati R, Greenleaf JF, Simari RD. Optimization of ultrasound-mediated gene transfer: comparison of contrast agents and ultrasound modalities. Eur. Heart J. 2003;24:1690–1698. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vannan M, McCreery T, Li P, Han Z, Unger E, Kuresten B, Nabel E, Rajagopalan S. Ultrasound-mediated transfection of canine myocardium by intravenous administration of cationic microbubble-linked plasmid DNA. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2002;15:214–218. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.119913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lentacker I, De Geest BG, Vandenbroucke RE, Peeters L, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, Sanders NN. Ultrasound-responsive polymer-coated microbubbles that bind and protect DNA. Langmuir. 2006;22:7273–7278. doi: 10.1021/la0603828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sirsi SR, Hernandez SL, Zielinski L, Blomback H, Koubaa A, Synder M, Homma S, Kanel JJ, Yamashiro DJ, Borden MA. Polyplex-microbubble hybrids for ultrasound-guided plasmid DNA delivery to solid tumors. J. Control. Release. 2012;157:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burke CW, Klibanov AL, Sheehan JP, Price RJ. Inhibition of glioma growth by microbubble activation in a subcutaneous model using low duty cycle ultrasound without significant heating. J. Neurosurg. 2011;114:1654–1661. doi: 10.3171/2010.11.JNS101201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kooiman K, Emmer M, Foppen-Harteveld M, van Wamel A, de Jong N. Increasing the endothelial layer permeability through ultrasound-activated microbubbles. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010;57:29–32. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2009.2030335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kooiman K, Foppen-Harteveld M, van der Steen AFW, de Jong N. Sonoporation of endothelial cells by vibrating targeted microbubbles. J. Control. Release. 2011;154:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding BS, Dzlubia T, Shuvaev VV, Muro S, Muzykantov VR. Advanced drug delivery systems that target the vascular endothelium. Mol. Interv. 2006;6:98–112. doi: 10.1124/mi.6.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simone E, Ding BS, Muzykantov VR. Targeted delivery of therapeutics to endothelium. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:283–300. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0676-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehier-Humbert S, Bettinger T, Yan F, Guy RH. Plasma membrane poration induced by ultrasound exposure: implication for drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2005;104:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muro S, Koval M, Muzykantov VR. Endothelial endocytic pathways: gates for vascular drug delivery. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2004;2:281–299. doi: 10.2174/1570161043385736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson CR, Hu X, Zhang H, Tlaxca JL, Decleves AE, Houghtaling R, Sharma K, Lawrence MB, Ferrara KW, Rychak JJ. Ultrasound molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis with an integrin targeted microbubble contrast agent. Invest. Radiol. 2011;46:215–224. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3182034fed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anderson CR, Rychak JJ, Backer M, Backer J, Ley K, Klibanov AL. scVEGF microbubble ultrasound contrast agents: a novel probe for ultrasound molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. Invest. Radiol. 2010;45:579–585. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181efd581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rychak JJ, Graba J, Cheung AM, Mystry BS, Lindner JR, Kerbel RS, Foster FS. Microultrasound molecular imaging of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in a mouse model of tumor angiogenesis. Mol. Imaging. 2007;6:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pochon S, Tardy I, Bussat P, Bettinger T, Brochot J, von Wronski M, Passantino L, Schneider M. BR55: a lipopeptide-based VEGFR2-targeted ultrasound contrast agent for molecular imaging of angiogenesis. Invest. Radiol. 2010;45:89–95. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181c5927c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.