Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure (E-VAC) therapy in the treatment of cervical esophageal leakage.

METHODS: Between May and November 2012, three male patients who developed post-operative cervical esophageal leakage were treated with E-VAC therapy. One patient had undergone surgical excision of a pharyngo-cervical liposarcoma with partial esophageal resection, and the other two patients had received surgical treatment for symptomatic Zenker’s diverticulum. Following endoscopic verification of the leakage, a trimmed polyurethane sponge was fixed to the distal end of a nasogastric silicone tube and endoscopically positioned into the wound cavity, and with decreasing cavity size the sponge was positioned intraluminally to cover the leak. Continuous suction was applied, and the vacuum drainage system was changed twice a week.

RESULTS: The initial E-VAC placement was technically successful for all three patients, and complete closure of the esophageal leak was achieved without any procedure-related complications. In all three patients, the insufficiencies were located either above or slightly below the upper esophageal sphincter. The median duration of the E-VAC drainage was 29 d (range: 19-49 d), with a median of seven sponge exchanges (range: 5-12 sponge exchanges). In addition, the E-VAC therapy reduced inflammatory markers to within normal range for all three patients. Two of the patients were immediately fitted with a percutaneous enteral gastric feeding tube with jejunal extension, and the third patient received parenteral feeding. All three patients showed normal swallow function and no evidence of stricture after completion of the E-VAC therapy.

CONCLUSION: E-VAC therapy for cervical esophageal leakage was well tolerated by patients. This safe and effective procedure may significantly reduce morbidity and mortality following cervical esophageal leakage.

Keywords: Endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure therapy, Vacuum therapy, Negative pressure wound therapy, Cervical esophageal leakage, Anastomotic leakage

Core tip: Traditional methods to treat cervical esophageal leakage close to the upper esophageal sphincter are associated with high morbidity and mortality. The newly developed method of endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure (E-VAC) therapy using polyurethane sponges has been demonstrated as efficacious for treating gastrointestinal tract leakages. We applied E-VAC therapy to three patients with post-operative cervical leakage and achieved complete closure in all, without any procedure-related complications. The E-VAC therapy was well tolerated by patients with cervical esophageal leakage, and its application in this patient population may contribute to a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Anastomotic leakage is a potentially life-threatening complication that may follow esophageal surgery. The leakage may range in severity from a minor anastomotic defect to a fulminant leak with systemic sepsis and multiple organ failure[1-3]. Cervical anastomoses have been associated with leakage rates as high as 40% and a mortality rate of 5%[4-6]. The treatment of cervical anastomotic leakage above the upper esophageal sphincter is particularly challenging, and only limited treatment options are available. Traditionally, the repair of cervical leakage has involved surgical intervention[7]; however, re-operation is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates[8]. Placement of self-expandable metal stents in such situations is difficult or even impossible and is associated with a high rate of procedure-related complications, such as globus sensation and/or respiratory insufficiency. Therefore, the procedure is often not performed[9-11].

Over the last decade, several endoscopic treatment options for repair of esophageal anastomotic leakages have emerged, including fibrin glue injection, endoscopic transluminal drainage and self-expanding metal stents[12-14]. Endoscopic treatment using self-expandable metal or plastic stents has become the treatment of choice for anastomotic esophageal leakage, and its reported success rates are above 80%[12,15-18]. Most recently, endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure (E-VAC) has been suggested as an effective treatment modality for esophageal anastomotic leakage in the upper gastrointestinal tract[19]. E-VAC therapy involves placing polyurethane sponges into the wound cavity that was induced by the leak, followed by application of an external vacuum through a transnasal tube to drain the infected fluid and induce the formation of granulation tissue. Recent studies of E-VAC therapy for the treatment of leaks following esophageal anastomoses have demonstrated that the procedure is capable of achieving successful wound closure with no associated mortality[20-23]. However, these studies have mainly examined intrathoracic anastomotic leakages. Here, we report the successful application of E-VAC therapy to treat cervical anastomotic leakages in three patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and procedure description

Between May and November 2012, three male patients with post-operative cervical esophageal leakage were treated with E-VAC therapy at the Endoscopy Unit of the Hannover Medical School (Hannover, Germany). E-VAC placement was performed as described previously[22] as the modified form of the VAC technique, which is an established treatment modality for chronic and infected cutaneous wounds[24,25]. Briefly, a trimmed polyurethane sponge, pore size 400-600 μm (KCI, Wiesbaden, Germany) was fixed to the distal end of a nasogastric silicone tube (Freka 15 Ch; Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) and introduced into the cavity under endoscopic vision. With decreasing cavity size, the sponge was placed endoluminally to cover the entire esophageal defect. A continuous negative pressure of 125 mmHg was applied using a vacuum pump (KCI). The vacuum drainage system was endoscopically changed two times per week. All endoscopic interventions were performed either under general anesthesia or conscious sedation with propofol and midazolam. All three patients gave informed consent for publication of their case, and retrospective analysis was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. The data are presented as individual values, median, and ranges.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients

We used E-VAC therapy to treat three male patients with post-operative cervical esophageal leakage. The patients were 69-, 71- and 80-year-old (Table 1). Patient 1 had undergone surgical excision of a pharyngo-cervical liposarcoma with partial esophageal resection followed by an insufficiency 3 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter (17 cm from the incisors). Patients 2 and 3 had suffered from cervical esophageal perforation following surgical treatment of a symptomatic Zenker´s diverticulum. Patient 2 had open surgery with a diverticulectomy and myotomy (Figure 1). Patient 3 suffered from recurrent Zenker´s diverticulum and was treated with transoral endoluminal mucomyotomy. The insufficiency in these two cases was located above the upper esophageal sphincter, at 17 cm from the incisors in patient 2 and at 19 cm from the incisors in patient 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of three patients who underwent endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure treatment

| Patient | Sex | Age, yr | Diagnosis | Surgical procedure | Cause of leakage | Distance from the dental arch, cm | Time interval from diagnosis to start of E-VAC therapy, d | Time interval from surgery to start of E-VAC therapy, d |

| 1 | Male | 80 | Liposarcoma | Thoracic esophageal resection | Anastomotic insufficiency | 17 | 11 | 25 |

| 2 | Male | 71 | Zenker´s diverticulum | Diverticulectomy and myotomy | Anastomotic insufficiency | 17 | 0 | 13 |

| 3 | Male | 69 | Zenker´s diverticulum | Mucomyotomy | Iatrogenic perforation | 19 | 0 | 2 |

E-VAC: Endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure.

Figure 1.

Radiographic findings of the second patient with Zenker’s diverticulum. A: Barium swallow showing the Zenker’s diverticulum (arrow) out-pouching from the posterior wall of the esophagus. Computed tomography scan showing the cervical esophageal leakage with periesophageal mediastinal abscess and extraluminal air (arrow); B: Contrasted esophagus (asterisk) with extravasation; C: Gastrografin swallow after endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure treatment showing a small residual saccular protrusion (arrow), but no leakage and no stenosis, clip in situ.

Results of E-VAC therapy

All three patients had endoscopically diagnosed esophageal leakage and their initial E-VAC placement was technically successful. In all three cases, the sponge was initially placed into the extraluminal cavity (intracavitary), which was changed to intraluminal placement with decreasing cavity size. Two patients immediately received a percutaneous enteral gastric feeding tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J tube) and the third patient received parenteral feeding (Table 2). The median duration of E-VAC therapy was 29 d (range: 19-49 d) with a median of seven sponge exchanges (range: 5-12 sponge exchanges) (Table 2). Median hospitalization time was 46 d (range: 42-108 d). In all three patients, complete closure of the leakage was achieved without any procedure-related complications and without the need for surgical re-intervention (Figure 2). Sponge therapy was well tolerated and there was no evidence of residual leakage either clinically or after Gastrografin swallow in patients 2 and 3. Inflammation was assessed by measuring white blood cell (WBC) counts and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. In two patients, the WBC count was initially elevated but decreased to within the normal range following E-VAC therapy. All three patients had markedly elevated CRP levels (range: 152-296 mg/L) at the beginning of the treatment, which were reduced to almost normal (range: 3-34 mg/L) by the time of discharge (Table 3). Patients were clinically followed-up after hospital discharge and endoscopy was performed in two patients at post-discharge days 47 and 206. All three patients had normal swallow function and no evidence of stenosis after completion of the E-VAC therapy.

Table 2.

Endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure treatment characteristics

| Patient | Treatment type | Sponge exchanges, n | E-VAC treatment duration, d | Hospitalization duration, d | Endoscopic follow-up2 duration, d | Feeding method |

| 11 | Intracavitary/ | 1 × 9 | 1 × 34 | 108 | None | PEG-J tube |

| intraluminal | 1 × 3 | 1 × 15 | ||||

| 2 | Intracavitary/ | 5 | 19 | 42 | 47 | Intravenously |

| intraluminal | ||||||

| 3 | Intracavitary/ | 7 | 29 | 46 | 206 | PEG-J tube |

| intraluminal |

Patient did not achieve complete healing after the first treatment cycle and underwent a second treatment;

Days after sponge removal. E-VAC: Endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure; PEG-J tube: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with jejunal extension.

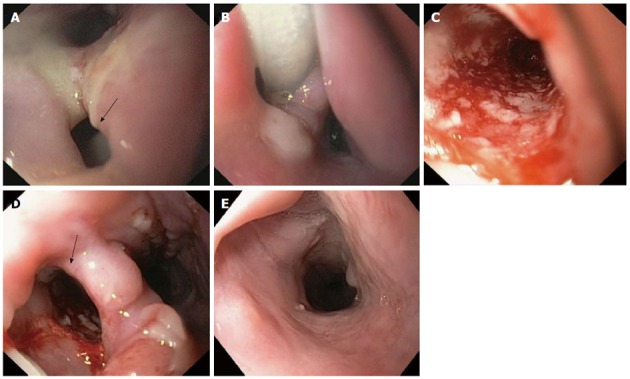

Figure 2.

Endoscopic images of cervical esophageal leakage after surgical diverticulectomy and cricopharyngeal myotomy and subsequent treatment with endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure. A: The defect was large enough to be intubated with a standard endoscope (arrow); B: Sponge positioned in the extraluminal wound cavity and connected to a drainage tube; C: Clean wound ground and formation of fresh granulation tissue with good vascularisation at 3 d after the endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure (E-VAC) therapy; D: Appearance of esophageal defect (arrow) at 11 d after the E-VAC therapy; E: Complete healing of the leakage at 47 d after completion of the E-VAC treatment.

Table 3.

Inflammation markers monitored during the endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure treatment

| Patient |

WBC |

CRP |

||

| 1st sponge placement | Sponge removal | 1st sponge placement | Sponge removal | |

| 1 | 11.6 | 4.3 | 152 | 34 |

| 2 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 244 | 34 |

| 3 | 14.3 | 9.9 | 296 | 3 |

WBC: White blood cell count, normal range: 4.4-11.3 Tsd/μL; CRP: C-reactive protein, normal range: < 8 mg/L.

DISCUSSION

Esophageal anastomotic leakage is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, particularly when surgical repair is required[1,4,8]. Consequently, efforts have been made to devise less invasive treatment modalities. A number of endoscopic techniques have emerged in recent years, including E-VAC therapy. Here, we report the successful use of E-VAC therapy for the treatment of post-operative cervical esophageal leakage.

Previous studies of E-VAC treatment were mainly concerned with the management of thoracoabdominal esophageal leakages; although, cervical esophagogastric anastomoses have a higher incidence of leaks compared to thoracic anastomoses[5]. Cervical leakages treated with E-VAC therapy have been rarely described[20,26]. Here, we examined two cases of Zenker´s diverticulum perforation with insufficiencies above the upper esophageal sphincter and one case of surgical excision of a pharyngo-cervical liposarcoma with partial esophageal resection followed by an insufficiency just below the upper esophageal sphincter. Due to high cervical localization of the perforation, stent placement was not considered. In all three patients, complete closure of the leakage was achieved without any procedure-related complications. None of the patients required further surgical intervention, and all three patients displayed regular swallow function after completion of the E-VAC therapy. Follow-up endoscopy in patients 2 and 3 demonstrated complete healing of the esophagus.

These case series indicate that E-VAC therapy has clinical utility in the repair of cervical esophageal leakage. These data justify conducting further studies to examine the potential of E-VAC therapy for treating other iatrogenic cervical esophageal perforations, such as perforations after transesophageal echocardiography, foreign body impaction, or endoscopic and surgical procedures. Compared to the previous studies of E-VAC therapy for treating thoracic esophageal leakage[20,26], our case studies of E-VAC therapy for treating cervical esophageal leakage required longer treatment times and a higher number of sponge changes. Therefore, we recommend early PEG placement for enteral feeding. However, despite the longer treatment times, the E-VAC therapy was well tolerated by all of our patients.

Our case studies suggest that use of E-VAC therapy allows for rapid removal of infected tissue. Prior to E-VAC therapy, all three patients displayed high levels of inflammatory markers that were indicative of systemic inflammatory complications from the esophageal leakage. Notably, a considerable reduction in the levels of these inflammatory markers was observed following treatment, which suggests that the E-VAC therapy resulted in rapid drainage of the infected wound cavity and control of inflammation.

In summary, we report that E-VAC therapy is a safe and efficacious treatment option for cervical esophageal leakage. E-VAC therapy appears to provide adequate wound drainage, promotion of tissue granulation within the wound cavity, and closure of the cervical esophageal defect. Despite the high localization of the vacuum placement, sponge therapy was well tolerated by our patients. Application of this therapy may contribute a significant improvement in morbidity and mortality. A multidisciplinary approach, involving the coordinated efforts of abdominal and/or ear-nose-throat surgeons, may further enhance E-VAC therapy as a treatment modality for cervical esophageal leakage.

COMMENTS

Background

Traditionally, the repair of cervical esophageal leakage has involved surgical intervention, as placement of self-expandable metal stents in this situation is difficult or even impossible. Most recently, endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure (E-VAC) has been suggested as an effective treatment modality for esophageal leakage. Therefore, the authors investigated the efficacy of E-VAC therapy for cervical leakage above or slightly below the upper esophageal sphincter.

Research frontiers

Cervical esophageal leakage is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, particularly when surgical repair is required. Therefore, this study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of a non-invasive endoscopic treatment using E-VAC therapy for treating cervical esophageal leakage.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study demonstrates that E-VAC therapy is an efficacious and safe treatment option for treating cervical esophageal leakage. Despite the high localization of the vacuum placement, the sponge therapy is well tolerated.

Applications

E-VAC therapy can be used as an alternative treatment option for cervical esophageal leakages above or slightly below the upper esophageal sphincter. These findings indicate the benefit of future studies addressing whether E-VAC therapy may also be useful for treatment of other iatrogenic cervical esophageal perforations, such as perforations after transesophageal echocardiography, foreign body impaction, or endoscopic and surgical procedures.

Terminology

The VAC technique is an established treatment modality for chronic and infected cutaneous wounds. Recently, the endoscopic placement of a vacuum-assisted closure system (endoscopic-vacuum assisted closure, E-VAC) in the gastrointestinal tract has been shown to be an effective treatment option for anastomotic leaks. The trimmed polyurethane foam with an open-cell structure (sponge) is fixed to the distal end of a silicone duodenal tube and endoscopically introduced into the necrotic cavity of the upper or the lower gastrointestinal tract. A continuous negative pressure of 125 mmHg is applied using a vacuum pump and the sponge is replaced two to three times per week.

Peer review

The authors conclude that E-VAC therapy is a safe and effective treatment option for cervical esophageal leakage.

Footnotes

Supported by The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft in the framework of the “Open Access Publishing” Program

P- Reviewers Issa IA, Morris DL, Ooi LL, Wang LS S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Urschel JD. Esophagogastrostomy anastomotic leaks complicating esophagectomy: a review. Am J Surg. 1995;169:634–640. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80238-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alanezi K, Urschel JD. Mortality secondary to esophageal anastomotic leak. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;10:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crestanello JA, Deschamps C, Cassivi SD, Nichols FC, Allen MS, Schleck C, Pairolero PC. Selective management of intrathoracic anastomotic leak after esophagectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierie JP, de Graaf PW, van Vroonhoven TJ, Obertop H. Healing of the cervical esophagogastrostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:448–454. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klink CD, Binnebösel M, Otto J, Boehm G, von Trotha KT, Hilgers RD, Conze J, Neumann UP, Jansen M. Intrathoracic versus cervical anastomosis after resection of esophageal cancer: a matched pair analysis of 72 patients in a single center study. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:159. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larburu Etxaniz S, Gonzales Reyna J, Elorza Orúe JL, Asensio Gallego JI, Diez del Val I, Eizaguirre Letamendia E, Mar Medina B. [Cervical anastomotic leak after esophagectomy: diagnosis and management] Cir Esp. 2013;91:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamek HE, Jakobs R, Dorlars D, Martin WR, Krömer MU, Riemann JF. Management of esophageal perforations after therapeutic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:411–414. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jougon J, Delcambre F, MacBride T, Minniti A, Velly JF. [Mortality from iatrogenic esophageal perforations is high: experience of 54 treated cases] Ann Chir. 2002;127:26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(01)00660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi EK, Song HY, Kim JW, Shin JH, Kim KR, Kim JH, Kim SB, Jung HY, Park SI. Covered metallic stent placement in the management of cervical esophageal strictures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macdonald S, Edwards RD, Moss JG. Patient tolerance of cervical esophageal metallic stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:891–898. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61807-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Profili S, Meloni GB, Feo CF, Pischedda A, Bozzo C, Ginesu GC, Canalis GC. Self-expandable metal stents in the management of cervical oesophageal and/or hypopharyngeal strictures. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:1028–1033. doi: 10.1053/crad.2002.0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Böhm G, Mossdorf A, Klink C, Klinge U, Jansen M, Schumpelick V, Truong S. Treatment algorithm for postoperative upper gastrointestinal fistulas and leaks using combined vicryl plug and fibrin glue. Endoscopy. 2010;42:599–602. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amrani L, Ménard C, Berdah S, Emungania O, Soune PA, Subtil C, Brunet C, Grimaud JC, Barthet M. From iatrogenic digestive perforation to complete anastomotic disunion: endoscopic stenting as a new concept of “stent-guided regeneration and re-epithelialization”. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1282–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Rio P, Dell’Abate P, Soliani P, Ziegler S, Arcuri M, Sianesi M. Endoscopic treatment of esophageal and colo-rectal fistulas with fibrin glue. Acta Biomed. 2005;76:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hünerbein M, Stroszczynski C, Moesta KT, Schlag PM. Treatment of thoracic anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy with self-expanding plastic stents. Ann Surg. 2004;240:801–807. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143122.76666.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kauer WK, Stein HJ, Dittler HJ, Siewert JR. Stent implantation as a treatment option in patients with thoracic anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:50–53. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelbmann CM, Ratiu NL, Rath HC, Rogler G, Lock G, Schölmerich J, Kullmann F. Use of self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of esophageal perforations and symptomatic anastomotic leaks. Endoscopy. 2004;36:695–699. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doniec JM, Schniewind B, Kahlke V, Kremer B, Grimm H. Therapy of anastomotic leaks by means of covered self-expanding metallic stents after esophagogastrectomy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:652–658. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weidenhagen R, Hartl WH, Gruetzner KU, Eichhorn ME, Spelsberg F, Jauch KW. Anastomotic leakage after esophageal resection: new treatment options by endoluminal vacuum therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1674–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahrens M, Schulte T, Egberts J, Schafmayer C, Hampe J, Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Schniewind B. Drainage of esophageal leakage using endoscopic vacuum therapy: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:693–698. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loske G, Schorsch T, Müller C. Intraluminal and intracavitary vacuum therapy for esophageal leakage: a new endoscopic minimally invasive approach. Endoscopy. 2011;43:540–544. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wedemeyer J, Brangewitz M, Kubicka S, Jackobs S, Winkler M, Neipp M, Klempnauer J, Manns MP, Schneider AS. Management of major postsurgical gastroesophageal intrathoracic leaks with an endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brangewitz M, Voigtländer T, Helfritz FA, Lankisch TO, Winkler M, Klempnauer J, Manns MP, Schneider AS, Wedemeyer J. Endoscopic closure of esophageal intrathoracic leaks: stent versus endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure, a retrospective analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:433–438. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie X, McGregor M, Dendukuri N. The clinical effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy: a systematic review. J Wound Care. 2010;19:490–495. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.11.79697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vikatmaa P, Juutilainen V, Kuukasjärvi P, Malmivaara A. Negative pressure wound therapy: a systematic review on effectiveness and safety. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schorsch T, Müller C, Loske G. Endoscopic vacuum therapy of anastomotic leakage and iatrogenic perforation in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2040–2045. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2707-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]