Abstract

The antagonistic Ac-TZ14011 peptide, which binds the CXCR4 receptor, has been labeled with a multifunctional single-attachment-point, MSAP, reagent to obtain a peptide derivative for multimodal imaging. The imaging label contained a DTPA chelate and a fluorescent dye with Cy5.5 spectral properties. Flow cytometry and confocal microscopy showed specific receptor binding of the multimodal peptide, regardless of the presence of indium in the chelate.

Introduction

The chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is a G-protein-coupled membrane receptor which is present in various cell types (1–2). CXCR4 has been shown to play a critical role in (breast) cancer progression and metastatic spread (3–4). It has been reported that 69% of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) lesions are CXCR4-positive (5). Over-expression of CXCR4 has also been suggested to be of value for imaging applications (6–7).

For molecular imaging of cancer-related biomarkers several modalities are in use, including SPECT, PET, MRI and fluorescence imaging (8). Each modality has its own strengths and weaknesses, and therefore, often more than one modality is needed during the clinical trajectory, viz. combined pre- and intraoperative imaging. Combining imaging modalities is referred to as multimodal imaging (9–12). An imaging probe for multimodal detection, hence, contains at least two different diagnostic labels. As we have shown, in particular the combination of radiolabels for SPECT or PET and fluorescent labels has potential in peptide-based molecular imaging (12). This combination benefits from the high sensitivity of nuclear imaging and the high spatial resolution of fluorescence imaging (11).

Several CXCR4 antagonistic peptides have been reported (13–14). One of the most potent peptides, T140, is a 14 amino acid-containing disulfide-bridged peptide with a rigid β-hairpin conformation (15). Residues 2, 3, 5 and 14 of T140 are mainly responsible for CXCR4 binding, whereas the residues 7–10 in the type II’ β-turn do not have direct contacts with CXCR4 within 3.0 Å (16). T140 has been optimized to Ac-TZ14011 for better CXCR4 binding, higher in vivo stability and easier functionalization, i.e. in Ac-TZ14011 only one amine group is present (D-Lys8) (17–19). The binding of dye- and chelate-labeled Ac-TZ14011 peptides to CXCR4 has already been validated in vitro and in vivo (17–19). However, a multimodal derivative of this CXCR4-targeting peptide has not yet been reported. Here, we report the synthesis of a multimodal Ac-TZ14011 by reaction of its single amine with a multifunctional single-attachment-point, MSAP, reagent (20–21)). We have performed initial in vitro validation studies to examine its cell specificity and receptor affinity. These in vitro studies form the basis for future in vivo testing.

Results and discussion

A multifunctional single point attachment (MSAP) reagent was synthesized as described, bearing a DTPA and CyAL5.5-b fluorochrome reporters and an NHS ester reactive group for reaction with the single lysine on the The CXCR4 peptide antagonist Ac-TZ14011 (1). The origin of the CyAL5.5b fluorochrome is explained in supplementary materials.

The CXCR4 peptide antagonist Ac-TZ14011 (1) was synthesized and purified as previously described (Figure 1) (17–19). This peptide contains one amine functionality (D-Lys8), which was used to conjugate the MSAP label 2. Peptide 3 was purified with preparative HPLC and characterized with mass spectrometry. After that, the lysine of peptide 3 was labeled with (non-radioactive) indium, yielding peptide 4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conjugation of the MSAP label (2) to Ac-TZ14011 (1) and subsequent indium labeling.

The absorption and emission spectra of 3 and 4 were recorded to demonstrate that indium binding in the chelate has no influence on the optical properties (see Supporting Information Figure S1). Indeed, the absorption spectra of both constructs were analogous and also the emission spectra were very similar.

The cellular uptake of the peptides 3 and 4 was quantitatively examined with flow cytometry. As a reference the commercial CXCR4 antibody CD184, clone 12G5-PE, was used to establish the difference in CXCR4 expression between two MDAMB231 cell lines. It was found that the higher CXCR4 expressing cells, MDAMB231CXCR4+, contained 4.4 times more 12G5-PE than the basal cell line MDAMB231 (Table 1). Subsequently, cells were incubated with 1 µM of compound 3 or 4 for 1 hour and then analyzed (Figure 2). The mean fluorescence intensity ratios (MFIRs) for 3 and 4 were approximately 10 times higher than that of the antibody (Table 1). This difference is probably caused by the fact that the concentration of the antibody was lower than that of peptides 3 and 4 (6.4 nM and 1 µM, respectively). Furthermore, the optical properties of the Cy5.5-like dye (λab = 680 nm, λem = 704 nm) are different than that of phycoerythrin (PE, λab = 496 nm and 564 nm, λem = 578 nm) in 12G5-PE. Regardless of these differences, the ratio of the fluorescent signals was for construct 3 a factor 4.1, which nicely corresponds to the ratio obtained with the antibody. For construct 4 the ratio was somewhat lower, namely 3.1. This is probably due to increased nonspecific binding of 4 to the cells, since both cell types had a higher MFIR. The increased nonspecific binding of 4 is possibly a charge-related effect: free DPTA is mainly -3 charged (5 carboxylates and 2 protonated nitrogen atoms) and indium-bound DTPA has a charge of -2 (5 carboxylates, no protonated nitrogen atoms and In3+) (22–23). A decrease in charge is expected to decrease the hydrophobicity, which generally results in more cellular uptake.

Table 1.

Quantitative analysis of cellular uptake of MDAMB231 and MDAMB231CXCR4+ cells using a CXCR4 antibody and the peptides 3 and 4.

| compound | MFIR ± SD MDAMB231 |

MFIR ± SD MDAMB231CXCR4+ |

ratio of MFIRs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12G5-PE antibody | 1.116 ± 0.054 | 4.920 ± 1.46 | 4.4 |

| 3 | 10.94 ± 1.62 | 45.27 ± 2.19 | 4.1 |

| 4 | 18.24 ± 1.93 | 56.67 ± 2.84 | 3.1 |

MFIR = mean fluorescence intensity ratio

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of the constructs 3 and 4 using (A) MDAMB231 cells or (B) MDAMB231CXCR4+ cells. Both graphs present untreated cells (trace filled with grey), 1 µM of 3 (black trace) and 1 µM of 4 (grey trace).

The receptor affinity of compounds 3 and 4 was also determined. First the affinity of peptide 3 for the MDAMB231CXCR4+ cells was determined by incubation with different concentrations of 3 and subsequent flow cytometry analysis (Figure 3A). The dissociation constant (KD) of 3 was found to be 186.9 nM (Table 2). In the same manner the receptor affinity of the indium labeled derivative 4, which gave somewhat higher cellular uptake values (Figure 3A), was determined to be 177.1 nM (Table 2). The affinities of 3 and 4 are not significantly different, indicating that indium binding does not affect receptor affinity, and therefore, the effects found in Figure 2 and Table 1 are most likely caused by nonspecific uptake.

Figure 3.

(A) Determination of affinity of constructs 3 and 4 with saturation binding experiments. (B) Competition experiments with three other Ac-TZ14011 peptides in the presence of 250 nM of 3. (C) Structures of the peptides used for competition experiments.

Table 2.

Dissociations constants (KD) of the constructs.

| Ac-TZ14011 peptide | KD (nM) |

|---|---|

| unlabeled (1) | 8.61 ± 1.42 |

| DTPA | 124.4 ± 23.9 |

| FITC | 203.5 ± 67.1 |

| 3 | 186.9 ± 52.4 |

| 4 | 177.1 ± 37.2 |

Competition experiments were performed by adding different amounts of Ac-TZ14011 (1), Ac-TZ14011-DTPA (19) or Ac-TZ14011-FITC (24) in the presence of 250 nM of peptide 3 (Figure 3B and 3C). The dissociation constants were calculated from the inhibition curves by fitting it to a competition model. The KD values of the monolabeled peptides Ac-TZ14011-DTPA and Ac-TZ14011-FITC were in the order of the KD values of 3 and 4 (Table 1). These results indicate that the bifunctional label does not hamper receptor binding more than the smaller FITC and DTPA monolabels. However, the unlabeled Ac-TZ14011 peptide 1 had an approximately 20 times higher receptor affinity than derivatives 3 and 4 (Table 2). Thus, despite of the fact that molecular modeling studies showed that D-Lys8 has no interaction with CXCR4 (16), functionalization of it still influences binding affinity. This influence might be explained by looking at the different effects of a modification of the peptide can have on receptor binding. A modification can directly change a receptor interaction (e.g. a hydrogen bond), can change the 3D structure of the peptide and/or can hinder the phamacophore to bind properly to the receptor (16). The third effect seems to cause the decrease in affinity, since the first two effects are most likely not applicable. Such a decrease in affinity upon conjugation of a bifunctional imaging label has also been observed for other peptidic imaging agents (12). Although the decrease in affinity is significant, it is most likely not an obstruction for imaging purposes, since the affinity is still in the nanomolar range (25).

Because the MSAP label appears to hinder the phamacophore to bind properly to CXCR4, a logical improvement would be the incorporation of a larger spacer between the label and the pharmacophore. However, it has been shown that incorporation of a 6-aminocaproic acid spacer does not yield a higher affinity (18). It is possible that even longer spacers will be more appropriate, but this has not been investigated yet.

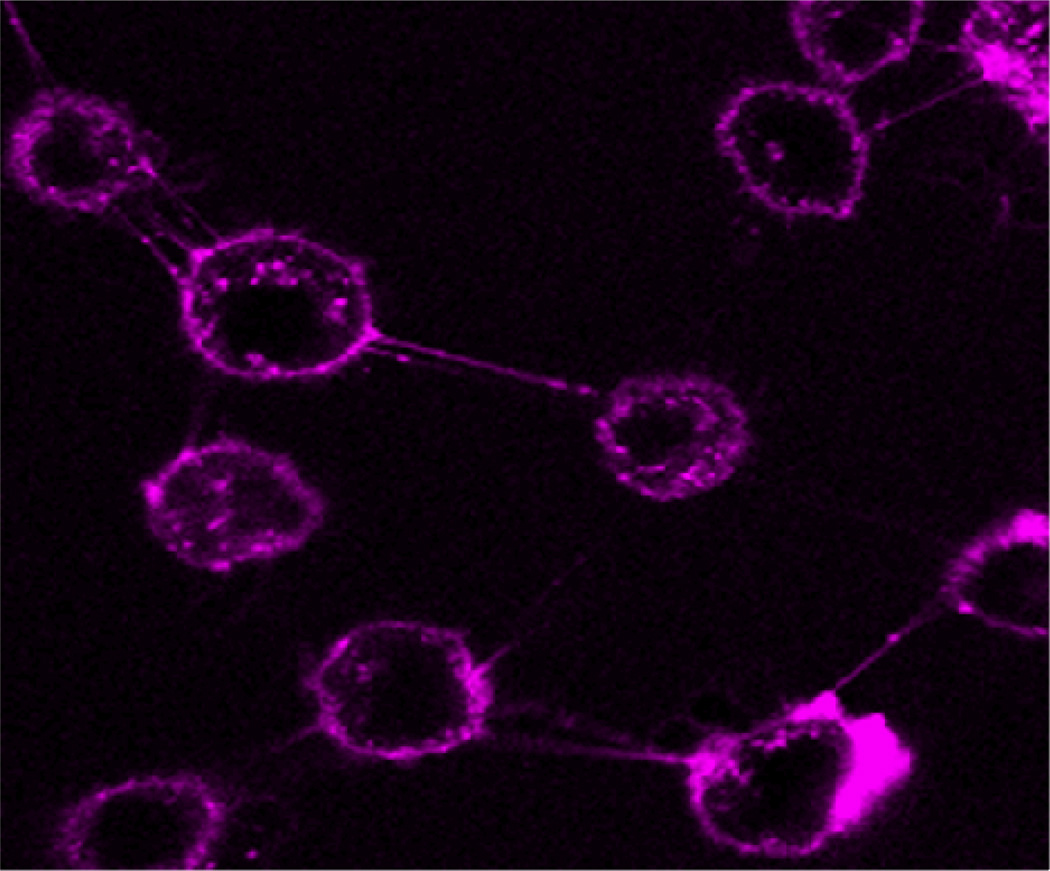

The cellular distribution of the MSAP peptide 3 was studied with confocal microscopy using MDAMB231CXCR4+ cells, which possessed a 4.4-fold increased level of CXCR4 expression (Table 1). The cells were incubated with 1 µM of MSAP peptide 3, washed and analyzed (Figure 4). A clear cell membrane staining was observed, corresponding to the fact that CXCR4 is a G-protein-coupled membrane receptor, as mentioned in the introduction (1–2). Moreover, staining in cellular vesicles was detected, which indicated that some CXCR4-bound fluorescent peptide was internalized. The observed cell staining supports the flow cytometry data of MDAMB231CXCR4+ cells.

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy of peptide 3 using MDAMB231CXCR4+ cells.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this paper the first bifunctional CXCR4 antagonistic peptide is reported. This peptide, Ac-TZ14011, has been labeled with a MSAP reagent containing a Cy5.5-like dye and a DTPA chelate and can specifically label MDAMB231CXCR4+ cells. Indium binding to the chelate does not affect the fluorescence of the dye. Furthermore, the MSAP label does not interfere with receptor binding more than other, smaller labels. In the near future we aim to test the properties of this peptide in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectra of 3 and 4. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Literature cited

- 1.Furusato B, Mohamed A, Uhlen M, Rhim JS. CXCR4 and cancer. Pathol. Int. 2010;60:497–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2010.02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhandari D, Robia SL, Marchese A. The E3 ubiquitin ligase atrophin interacting protein 4 binds directly to the chemokine receptor CXCR4 via a novel WW domain-mediated interaction. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1324–1339. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-03-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teicher BA, Fricker SP. CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2010;16:2927–2931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazennec G, Richmond A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2010;16:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvucci O, Bouchard A, Baccarelli A, Deschenes J, Sauter G, Simon R, Bianchi R, Basik M. The role of CXCR4 receptor expression in breast cancer: a large tissue microarray study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2006;97:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nimmagadda S, Pullambhatla M, Stone K, Green G, Bhujwalla ZM, Pomper MG. Molecular imaging of CXCR4 receptor expression in human cancer xenografts with [64Cu]AMD3100 positron emission tomography. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3935–3944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han Y, Yin D, Zheng M, Zhou W, Lee Z, Zhan L, Ma Y, Wu M, Shi L, Wang N, Lee J, Wang C, Lee Z, Wang Y. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of a novel 125I-labeled T140 analog for quantitation of CXCR4 expression. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2010;284:279–286. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mather S. Molecular imaging with bioconjugates in mouse models of cancer. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:631–643. doi: 10.1021/bc800401x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings LE, Long NJ. 'Two is better than one'–probes for dual-modality molecular imaging. Chem. Commun. 2009:3511–3524. doi: 10.1039/b821903f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louie A. Multimodality imaging probes: design and challenges. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:3146–3195. doi: 10.1021/cr9003538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culver J, Akers W, Achilefu S. Multimodality molecular imaging with combined optical and SPECT/PET modalities. J. Nucl. Med. 2008;49:169–172. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuil J, Velders AH, Van Leeuwen FWB. Multimodal tumor-targeting peptides functionalized with both a radio-and a fluorescent-label. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1021/bc100276j. accepted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamamura H, Omagari A, Hiramatsu K, Gotoh K, Kanamoto T, Xu Y, Kodama E, Matsuoka M, Hattori T, Yamamoto N, Nakashima H, Otaka A, Fujii N. Development of specific CXCR4 inhibitors possessing high selectivity indexes as well as complete stability in serum based on an anti-HIV peptide T140. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:1897–1902. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamamura H, Hiramatsu K, Kusano S, Terakubo S, Yamamoto N, Trent JO, Wang Z, Peiper SC, Nakashima H, Otaka A, Fujii N. Synthesis of potent CXCR4 inhibitors possessing low cytotoxicity and improved biostability based on T140 derivatives. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1:3656–3662. doi: 10.1039/b306473p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamamura H, Sugioka M, Odagaki Y, Omagari A, Kan Y, Oishi S, Nakashima H, Yamamoto N, Peiper SC, Hamanaka N, Otaka A, Fujii N. Conformational study of a highly specific CXCR4 inhibitor, T140, disclosing the close proximity of its intrinsic pharmacophores associated with strong anti-HIV activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:359–362. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00664-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trent JO, Wang ZX, Murray JL, Shao W, Tamamura H, Fujii N, Peiper SC. Lipid bilayer simulations of CXCR4 with inverse agonists and weak partial agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:47136–47144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nomura W, Tanabe Y, Tsutsumi H, Tanaka T, Ohba K, Yamamoto N, Tamamura H. Fluorophore labeling enables imaging and evaluation of specific CXCR4-ligand interaction at the cell membrane for fluorescence-based screening. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1917–1920. doi: 10.1021/bc800216p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oishi S, Masuda R, Evans B, Ueda S, Goto Y, Ohno H, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G, Wang Z, Peiper SC, Naito T, Kodama E, Matsuoka M, Fujii N. Synthesis and application of fluorescein- and biotin-labeled molecular probes for the chemokine receptor CXCR4. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:1154–1158. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanaoka H, Mukai T, Tamamura H, Mori T, Ishino S, Ogawa K, Iida Y, Doi R, Fujii N, Saji H. Development of a 111In-labeled peptide derivative targeting a chemokine receptor, CXCR4, for imaging tumors. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2006;33:489–494. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garanger E, Aikawa E, Reynolds F, Weissleder R, Josephson L. Simplified syntheses of complex multifunctional nanomaterials. Chem. Commun. 2008:4792–4794. doi: 10.1039/b809537j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garanger E, Blois J, Hilderbrand SA, Shao F, Josephson L. Divergent oriented synthesis for the design of reagents for protein conjugation. J. Comb. Chem. 2010;12:57–64. doi: 10.1021/cc900141b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moulin C, Amekraz B, Steiner V, Plancque G, Ansoborlo E. Speciation studies on DTPA using the complementary nature of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and time-resolved laser-induced fluorescence. Appl. Spectrosc. 2003;57:1151–1161. doi: 10.1366/00037020360696026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maecke HR, Riesen A, Ritter W. The molecular structure of indium-DTPA. J. Nucl. Med. 1989;30:1235–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van den Berg NS, Buckle T, Kuil J, Wesseling J, Van Leeuwen FWB. Direct fluorescent detection of CXCR4 using a targeted peptide antagonist. 2010 doi: 10.1593/tlo.11115. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schottelius M, Wester HJ. Molecular imaging targeting peptide receptors. Methods. 2009;48:161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.