Abstract

In China, formal long-term care services for the large aging population have increased to meet escalating demands as demographic shifts and socioeconomic changes have eroded traditional elder care. We analyze China’s evolving long-term care landscape and trace major government policies and private-sector initiatives shaping it. Although home and community-based services remain spotty, institutional care is booming with little regulatory oversight. Chinese policy makers face mounting challenges overseeing the rapidly growing residential care sector, given the tension arising from policy inducements to further institutional growth, a weak regulatory framework, and the lack of enforcement capacity. We recommend addressing the following pressing policy issues: building a balanced system of services and avoiding an “institutional bias” that promotes rapid growth of elder care institutions over home or community-based care; strengthening regulatory oversight and quality assurance with information systems; and prioritizing education and training initiatives to grow a professionalized long-term care workforce.

Aging populations pose serious challenges for the health and long-term care systems in many countries around the world.1 The challenges are particularly acute in China, where demographic shifts are rapid, exacerbated by the one-child family policy.2 The country is undergoing profound socioeconomic changes, and Chinese families—the traditional bedrock of old-age security—are increasingly strained as the number of older people explodes while the number of potential caregivers shrinks.3

Amid these trends, formal long-term care services for the elderly have emerged and expanded rapidly in China, catalyzed by government policies and private-sector initiatives.4 Not long ago, institutional elder care was rare and limited to state-run institutions exclusively serving childless elders, orphans, the mentally ill, and developmentally disabled adults without families.5,6 Today the landscape is being reshaped by a new class of private-sector facilities catering to elderly Chinese not being cared for by adult children at home.4,7 These developments are revolutionary in a society that for millennia enshrined the Confucian norm of filial piety and family care.

In this article we outline the broad contour of China’s evolving long-term care landscape, trace the development of major government policies in shaping this landscape, and discuss the multifaceted challenges for Chinese policy makers as they scramble to build a viable long-term care system. We offer policy insights that are applicable not only to China but also to other rapidly aging and developing countries. To place these discussions in perspective, we begin by summarizing demographic and sociocultural trends in China.

China’s Demographic Tsunami

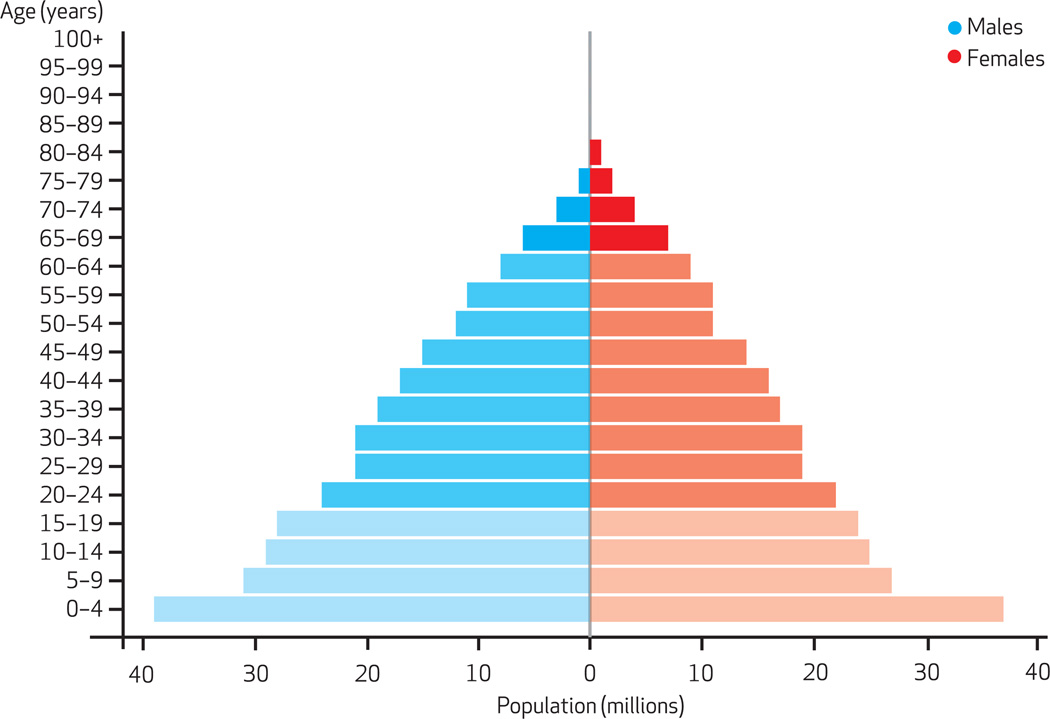

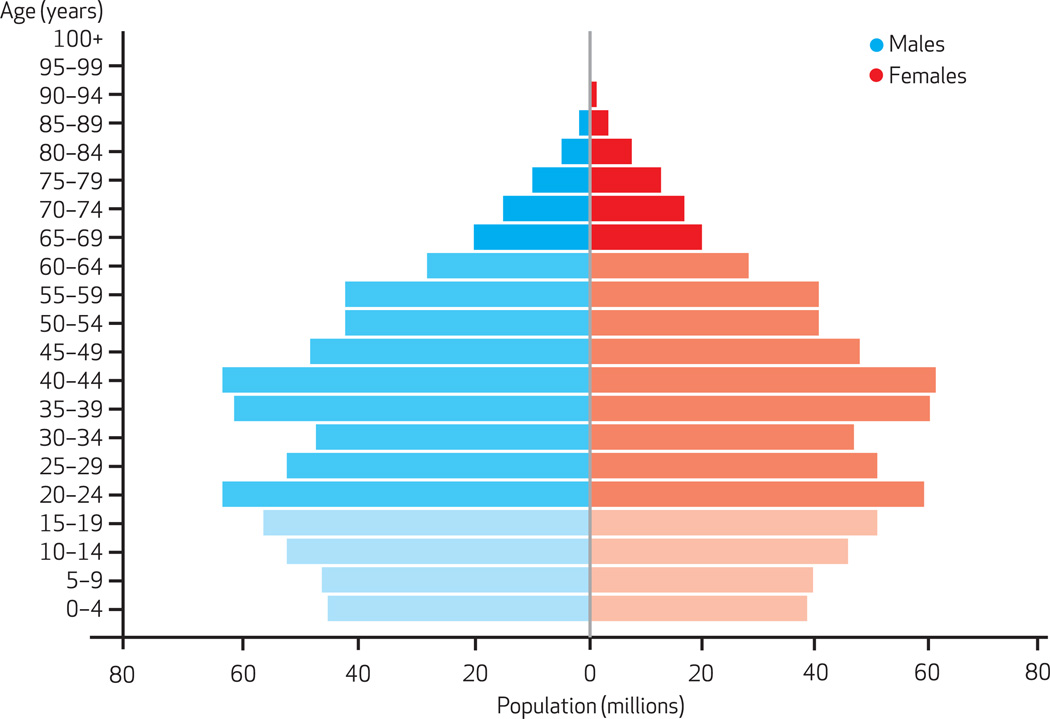

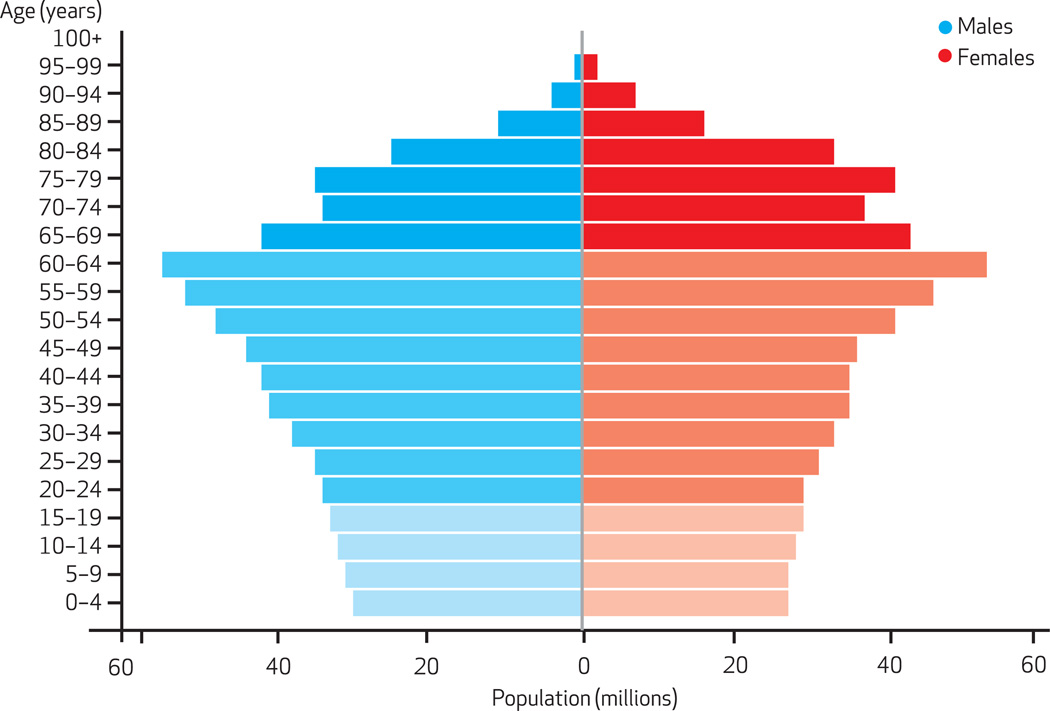

In 1950 China had a young and fast-growing population, with a median age of twenty-four (Exhibit 1). By 2010 the population age structure had shifted upward considerably, to a median age of thirty-five (Exhibit 2). By 2050, when the median age will approach fifty, one out of every four Chinese will be sixty-five or older (Exhibit 3).8

EXHIBIT 1.

Age Structure Of China’s Population, 1950

SOURCE United Nations. World population prospects: the 2010 revision (Note 8 in text).

EXHIBIT 2.

Age Structure Of China’s Population, 2010

SOURCE United Nations. World population prospects: the 2010 revision (Note 8 in text).

EXHIBIT 3.

Age Structure Of China’s Population, 2050 (Projected)

SOURCE United Nations. World population prospects: the 2010 revision (Note 8 in text).

The old-age dependency ratio—the number of people ages 65 and older per 100 working-age people ages 20–64—is projected to soar, from 13 dependents per 100 working-age people in 2010 to 45 per 100 by 2050.8 The ranks of the “oldest old,” those ages eighty and older, is swelling even faster, from roughly eighteen million in 2010 to a projected ninety-eight million by 2050.8

Nationwide, an estimated thirty-three million Chinese over age sixty have limitations in handling daily living activities, and almost a third of them are dependent on others for assistance.9 Long-term care needs and associated costs are especially high for the oldest old and are projected to rise rapidly.10

Elder Care In China: Tradition And Change

The Confucian norm of filial piety is deeply rooted in Chinese elder care.11,12 The centrality of family care for older Chinese has been summed up by the statement: “For thousands of years, filial piety was China’s Medicare, Social Security and long-term care, all woven into a single family value.”13

However, demographic shifts and socioeconomic changes are eroding this tradition, raising concerns that families may not continue to be the mainstay of elder care.14–16 In cities, the emerging “4-2-1” family structure (four grand-parents; two parents, neither of whom has siblings; and one child) is emblematic of the potential problem.3 In the countryside, the fulfillment of filial piety by adult children is increasingly difficult, aggravated by the massive outmigration of young people to cities for work.16 Some rural elders have resorted to signing a “family support agreement” contract with adult children to ensure needed support and care.17

The very concept of filial piety is evolving, as reflected in shifting attitudes among both the old and the young toward independence and autonomy in living arrangements and the increasing tolerance of institutional care for elders.18–21

China has recently launched a series of policy initiatives to improve its health care and social security systems. These include expanding basic health insurance for all through the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance Scheme (since 1998), the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (since 2003), and the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance Scheme (since 2007).22,23 In 2009 the New Rural Pension Insurance pilot program started in 10 percent of Chinese counties and is scheduled to roll out nationwide to cover all rural elderly by 2020.24 Because the policy focus is on achieving universal coverage with shallow benefits in the short term,25 whether these programs will be extended to include long-term care services remains to be seen.

China’s Evolving Long-Term Care Landscape

Until recently, institutional elder care in China was rare and limited to the so-called “Three No’s”—people with no children, no income, and no relatives, who were publicly supported welfare recipients.26 Institutionalized elders were stigmatized.27 Few families could imagine placing a loved one in an institution to be cared for by strangers. Most residential care homes were run by the state, municipalities, local governments, or collectives.

In the mid-1990s China implemented reforms to decentralize the operation and financing of state welfare institutions.28,29 Since then, these institutions have shifted their financial base from reliance on public funding to more diversified revenue sources, including privately paying individuals.27

Elder care homes have proliferated, primarily in the private sector in urban areas.4,7 Although there are limited data, one recent study provides a glimpse into the growth and character of this nascent industry over the past thirty years.4 In Tianjin, for instance, there were only 4 facilities in 1980 (all government run), but there were 13 by 1990, 68 by 2000, and 157 by 2010 (20 of these facilities were government run, and 137 were privately run). Similar rates of growth were also observed in Nanjing and Beijing.4

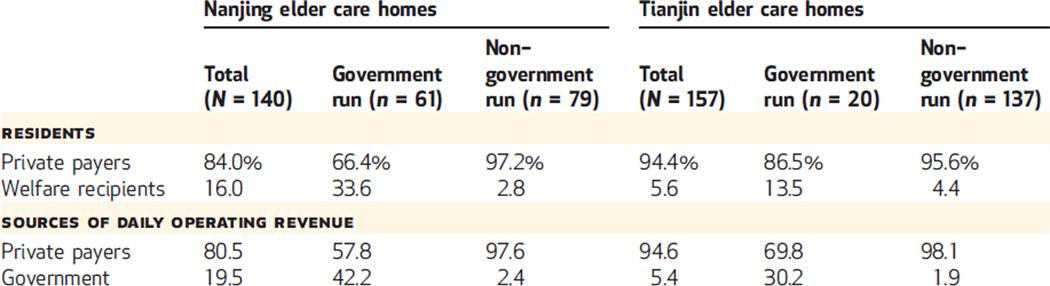

The historical pattern of residents in elder care facilities and the sources of revenue that pay for their institutional care have also changed, as shown in Exhibit 4. In Tianjin in 2010 and Nanjing in 2009, almost all residents in nongovernment-run homes were private payers. Even in government-run homes, most residents were private payers. Welfare recipients were rare and mostly housed in government facilities.

EXHIBIT 4.

Elder Care Homes’ Residents And Sources Of Daily Operating Revenue, Nanjing (2009) And Tianjin (2010), China

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from elder care homes in Nanjing and Tianjin. NOTE Numbers are means across facilities in each column.

The current mix of facilities spans a wide spectrum, ranging from “mom and pop”–style board-and-care homes providing little professional care to modern nursing homes with skilled nursing and medical services.4

As of 2010 there were an estimated 40,000 elder care facilities and 3.15 million beds in those facilities nationwide.30 On a per capita basis, China has about half as many long-term care beds per 1,000 older people as most developed countries do. Just 1.5–2.0 percent of people ages sixty-five and older live in residential care facilities in China, compared with 4–8 percent in Western countries.31,32

China’s twelfth five-year plan (2011–15) for socioeconomic development set a goal of adding another 3.42 million beds in the next five years, to boost total capacity to thirty beds per 1,000 elders ages sixty and older by 2015, from roughly eighteen beds per 1,000 elders in 2011.30

Shaping A Long-Term Care System In China

Policy attention to aging issues in China has increased since 1999, when the China National Committee on Aging was established. This committee now involves twenty-eight ministerial-level government agencies and coordinates policy making, planning, and developing elder care services nationally.

Recent national policy initiatives have sought to develop a system of services for the elderly. The blueprint of this emerging system, as outlined in the twelfth five-year plan, consists of three tiers of social services for the aged: home-based care as the “basis,” community-based services as “backing,” and institutional care as “support.”33

HOME AND COMMUNITY-BASED SERVICES REMAIN SPOTTY

The Chinese government has actively promoted home-based care as the primary pillar of services for the aged. This stance is con- sistent with the cultural tradition of filial piety.32 Most of the care within an elder’s home is informal care by family members. For those who can afford it, this informal care may be supplemented by formal services provided at home by paid caregivers.

A series of national policy initiatives over the last decade attempted to develop community-based services. A notable example was the Starlight Program, under which the government invested a total of 13.4 billion yuan (roughly US $2.1 billion) to build urban community-based senior services centers during 2001–04. By 2005 the program had established 32,000 Starlight Senior Centers nationwide.34

However, the centers have apparently not served their intended purpose. After 2005 the Starlight Program lost momentum partly because of dwindling financial support from the government, raising questions about the viability of similar initiatives. To date, self-sustaining, community-based long-term care services remain largely nonexistent, except in a few major urban centers like Shanghai.35

More recently, a new type of home-based elder care model, called Virtual Elder Care Home or Elder Care Home without Walls, has gained popularity in China.36 It features home care agencies providing a wide range of personal care and homemaker services in elders’ homes. Services are initiated by phone calls to a local government–sponsored information and service center, which then directs a qualified service provider to the elder’s home.

Participating providers contract with the local government and are reimbursed for services purchased by the government on behalf of eligible care recipients, the majority of whom are “Three No’s” or otherwise vulnerable. Since its inception in 2007 in the city of Suzhou, in eastern China’s Jiangsu Province, the Virtual Elder Care Home model has spread to many parts of the country, including Gansu Province in northwest China.37

To date, policy initiatives to support home or community-based care have been largely limited to urban areas, and even there, the number of beneficiaries is still relatively small. In much of rural China, the development of home and community-based services faces many practical challenges because of the physical environment and the lack of resources and infrastructure. Instead, current practice and policy directions in rural areas favor institutions by encouraging “centralized support and care” in rural homes for the aged that are run, or subsidized, by the local county or township government.38,39

INSTITUTIONAL ELDER CARE IS BOOMING

In recent years, the Chinese government has increased efforts to build residential elder care services by actively promoting the construction of senior housing, homes for the aged, and nursing homes.34 This development has followed two separate tracks leading to a dual system of institutional elder care: One is directly developed, owned, and managed by the government; the other is market driven and developed, owned, and run by private-sector entities.

In cities, government-run institutions and senior care homes are required to admit elders who qualify as “Three No’s.” In rural areas, government-run homes for the aged target the “Three No’s” who are eligible for the “Five Guarantees”—namely, food, clothing, housing, medical care, and burial expenses. Indeed, virtually all residents in rural facilities are welfare recipients, as they have always been.40

What is new is that the government now looks to the private sector to develop elder care facilities to address the severe shortage of long-term care beds. Private-sector initiatives are seen as the fastest way to meet the demand.41 Policy makers also realize that the government’s role must shift from being the direct “supplier and provider” to being a “purchaser and regulator” of services.41

Guided by this strategic shift, a series of national policy directives have been issued to speed up private-sector development of institutional social services for the aged. Multiple strategies are in play, ranging from state-built and privately run facilities to privately operated facilities with government support and subsidies for construction and operations.34

POLICY INDUCEMENTS ARE FUELING FURTHER GROWTH

National policy directives have urged local governments to apply preferential policy treatments for private-sector development of elder care facilities, such as tax exemptions, subsidies for new and existing beds, land allotment or leasing for new construction, and reduced utility rates. Formulated and implemented locally, the incentives and subsidies vary substantially by form and amount across regions.

Municipal governments have responded to national policy directives with substantial incentives to spur construction and operation of facilities. In Nanjing, for instance, the municipal government provides financial inducement for new construction in the amount of 2,000–4,000 yuan (roughly US$317–$635) per new bed and an ongoing operating subsidy of 80 yuan (about US$13) per occupied bed each month.4 In Beijing the municipal government provides a construction subsidy of 8,000–16,000 yuan (about US$1,270–$2,540) per new bed and an operating subsidy of 100–200 yuan (about US $16–$32) per occupied bed.39

Policy inducements, coupled with rising consumer demand and purchasing power, have bolstered entrepreneurial interest amongreal estate developers, venture capitalists, investors, and other businesses—both domestic and foreign— in tapping China’s booming senior care market. Several US-based firms and private equity funds have recently sought to invest in Western-style senior housing in China.42,43 However, the obstacles to success are numerous, including an unrealistic market niche (most investors pursue high-end facilities, which few elderly Chinese can afford), cultural incongruity (Western-style care and services may not align well with local customs or consumer preferences), and an uncertain regulatory environment.

The Challenges Of Regulatory Oversight

The national regulatory authority over elder care services rests primarily with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. As is typical of the Chinese policy-making process, the ministry sets national policies and regulatory guidelines that are to be implemented by provincial-level officials. Directives then trickle down to cities and counties in each province.

NATIONAL REGULATORY FRAMEWORK REMAINS SKETCHY

At the national level, only minimal standards currently exist for the regulation of providers of elder care. In 1999 the Ministry of Civil Affairs released the Provisional Measures for the Management of Social Welfare Institutions.44 This national policy effort was the first designed to formalize regulation of all types of social welfare institutions. The current regulatory structure is based on three major policy documents, as outlined below. Efforts are now under way to revise these regulations, although they are still the prevailing official guidelines.

The Code for Design of Buildings for Elderly Persons was jointly promulgated by the Ministry of Construction (now named the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development) and the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 1999 and addresses the “bricks and mortar” of facilities housing the elderly.45 The Code is applicable to all city and town residential buildings and public facilities that cater exclusively to the elderly.

The Basic Standards for Social Welfare Institutionsfor the Elderly was promulgated by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 2001.46 It stipulates the guiding principles, basic service standards, facility operations, and equipment for such institutions. This was the first national guideline to set minimum standards applicable to social welfare institutions of all types. It outlines different facility characteristics appropriate to meet the varying needs of the elderly. However, detailed criteria differentiating residents by levels of care are lacking.

The National Occupational Standards for Old-Age Care Workers was drafted by the Ministry of Civil Affairs and approved and promulgated by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security (now named the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security) in 2002.47 An old-age care worker is defined as a person who “provides daily living assistance or nursing for the elderly.”47(p1) The basic requirements for this occupation, a fairly new job category, include a middle school education (nine years of schooling) and at least 180 hours of training for entry-level workers. However, the number of workers who have actually met these basic requirements is widely believed to be very small.

LOCAL REGULATORY ENFORCEMENT IS WEAK

Local authorities are responsible for adhering to national policy guidelines in a manner that best fits local conditions. Officials in Tianjin acknowledged many practical difficulties that exist in exercising regulatory oversight, partly because of the lack of specificity in current regulations and the paucity of qualified inspection personnel.48

Compliance with the required building code is a challenge in Tianjin, where most elder care homes are retrofitted residential buildings, factories, or even schools leased by the provider. Since there are limits to repurposing existing buildings for elder care, many facilities may not comply with mandated standards. Local officials acknowledged this situation but viewed it as a necessary compromise to increase bed supply quickly.48

TENSIONS RESULT FROM CONFLICTING POLICY INTERESTS

Officials in Tianjin noted the tension between conflicting government policies of ex-panding supply and implementing regulations.48 Generally, the zeal for growth trumps regulatory oversight on the policy agenda.

The misalignment of policy incentives is also evident in the allocation of land for new construction. With economic growth as the top priority, local governments tend to favor for-profit businesses when approving land deals. In Tianjin and elsewhere, virtually all private-sector elder care facilities are registered as non-enterprise, not-for-profit entities in order to receive a tax exemption. Given the scarcity and escalating cost of land, it is not surprising that local governments have little incentive to parcel out land to nonprofit entities that do not generate tax revenue.48

Consequently, relatively few private-sector facilities have been built recently because of difficulties obtaining government land leases. This may increasingly become a barrier for private-sector initiatives in developing long-term care services. For rental facilities, disputes over property rights—which are often murky in China— and leasing contracts also complicate investment.

Policy Recommendations

Chinese policy makers confront numerous challenges in developing appropriate policy responses as the formal long-term care services sector continues to grow rapidly. We highlight three pressing issues and offer recommendations to address them.

PROVIDING A MIX OF SERVICES THAT ELDERLY PEOPLE WANT

The preference of older people for living in their own home for as long as possible seems to be universal, but it is perhaps especially so in China, where family values are highly regarded and ingrained in the cultural tradition of filial piety. China’s blueprint for a three-tiered long-term care system aptly emphasizes home and community-based services.

In actuality, however, current policies and resource allocation tilt toward institutional care. The need for more facilities may be justified, but Chinese policy makers should be careful to avoid an institutional bias in the country’s fledgling long-term care system. Although what constitutes an optimal service mix seems elusive, policy makers should strive to build a balanced system of services that reflects older people’s preference as much as possible.

STRENGTHENING REGULATORY OVERSIGHT THROUGH INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Scandals have already begun to surface about Chinese long-term care facilities, underscoring the need for regulatory oversight. Chinese policy makers need to institute a formalized regulatory structure soon. Effective oversight will require building an information system to facilitate evidence-based policy making, quality assurance, and regulatory enforcement.

China may learn a great deal from the United States, where all publicly certified nursing homes must report both facility- and resident-level data electronically, using a uniform annual facility inspection survey and standardized resident assessment. It will take time and resources to build an information infrastructure in China, but the ubiquitous Internet means that China can institute such a system more quickly than was possible in the United States two decades ago.

BUILDING A LONG-TERM CARE WORKFORCE

At present, the lack of a qualified and professional workforce in long-term care is an urgent issue in China. The majority of direct care workers are inadequately trained and poorly paid. Even the most optimistic estimate suggests that fewer than one-third of all direct care workers providing elder care services have received any professional training.9

However, inadequate training for direct care workers is not the only impediment. Professional clinical and management staff are also needed to ensure a transition to a modern, information-based long-term care delivery system. Chinese policy makers should prioritize education and training initiatives to grow a professionalized long-term care workforce.

Conclusion

As China’s population ages, pressures are building for policy makers to develop a viable long-term care system to meet escalating demands. Although home and community-based services are preferred by most elderly Chinese and promoted by the government, such services remain spotty across most cities and towns in China and are virtually nonexistent in rural areas. In contrast, institutional elder care is expanding rapidly, primarily in the urban private sector.

Partially due to policy makers’ zealous pursuit of building beds quickly to meet the perceived gap between rising demand and limited supply, little regulatory oversight exists over the kinds of services and the quality of care provided in Chinese long-term care facilities. Policy makers in China will confront numerous challenges in fostering and monitoring this rapidly growing long-term care services sector, including conflicting policy interests, a weak regulatory framework, and lack of enforcement capacity.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this article was supported, in part, by a grant from the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R03TW008142).

Biographies

Zhanlian Feng is a senior research public health analyst at RTI International.

In this month’s Health Affairs, Zhanlian Feng and coauthors analyze China’s evolving long-term care landscape and trace major government policies and private-sector initiatives that are shaping it. Although home and community-based services remain spotty, institutional care is booming, with little regulatory oversight and a lack of enforcement capacity. The authors recommend that China learn from past mistakes in the United States and build a balanced system of services for home and community-based care; strengthen regulatory oversight and quality assurance; and prioritize the education and training of a professionalized long-term care workforce.

Feng is a senior research public health analyst in the Aging, Disability, and Long-Term Care Program at RTI International and an adjunct assistant professor of health services, policy, and practice at Brown University. His current research interests include the use of health services by older people with dementia or cognitive impairments, federal and state policies shaping the US long-term care landscape, and socioeconomic differences in access to and quality of long-term care services.

Feng is a leading researcher on emerging long-term care issues in China and was named an aged care policy research expert in 2011 by the China Association of Social Welfare. He earned a master’s degree and a doctorate in sociology and demography from Brown University.

Chang Liu is a doctoral candidate at Brown University.

Chang Liu is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at Brown University. His research focuses on health insurance and elder care. His current work uses econometric study designs to examine the impact of insurance policies on patient and provider behaviors and their economic implications. He is also interested in cost-effectiveness analysis in health care decision making.

Liu was awarded the eXebs Friedrich J. Schoening International Scholarship and was named an eXebs Fellow while he was an exchange student at the European Business School. He also received scholarships from the Ronald Coase Institute, the Fu-ren Dong Foundation, and the Rand Summer Institute. Liu received a master’s degree in finance from the Guanghua School of Management of Peking University, in China.

Xinping Guan is director of the Institute of Social Development and Administration at Nankai University.

Xinping Guan is a professor in and chair of the Department of Social Work and Social Policy and director of the Institute of Social Development and Administration at Nankai University, in China. His current academic and research areas include social policy, social work, and social demography. He serves as vice director of the China Association of Social Work Education and vice director of the Social Policy Committee of the China Association of Sociology.

Guan is a member of the Expert Advisory Committee of the Ministry of Civil Affairs and a member of the Directing Board of Sociological Teaching of the Ministry of Education, in China. He received a master’s degree in sociology and a doctorate in economics from Nankai University.

Vincent Mor is the Florence Pirce Grant Professor of Community Health at Brown University.

Vincent Mor is the Florence Pirce Grant Professor of Community Health in the Public Health Program at the Brown University School of Medicine and a research health scientist at the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center. He was awarded a Distinguished Investigator Award by AcademyHealth in 2011 and is a member of the AcademyHealth board of directors.

Mor is also an editorial board member of Health Services Research, the Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, and BMC Health Services Research. He received a master’s degree in rehabilitation administration from Northeastern University, a doctorate in social welfare policy from Brandeis University, and an honorary master’s degree from Brown University.

Contributor Information

Zhanlian Feng, Email: zfeng@rti.org, Senior research public health analyst in the Aging, Disability, and Long-Term Care Program at RTI International, in Waltham, Massachusetts.

Chang Liu, Doctoral candidate in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island.

Xinping Guan, Chair of the Department of Social Work and Social Policy and director of the Institute of Social Development and Administration at Nankai University, in China.

Vincent Mor, Florence Pirce Grant Professor of Community Health in the Public Health Program at the Brown University School of Medicine.

NOTES

- 1.Kinsella K, He W. An aging world: 2008. Washington (DC): Census Bureau; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hesketh T, Lu L, Xing ZW. The effect of China’s one-child family policy after 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1171–1176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flaherty JH, Liu ML, Ding L, Dong B, Ding Q, Li X, et al. China: the aging giant. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1295–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng Z, Zhan HJ, Feng X, Liu C, Sun M, Mor V. An industry in the making: the emergence of institutional elder care in urban China. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):738–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu B, Mao Z, Xu Q. Institutional care for elders in rural China. J Aging Soc Policy. 2008;20(2):218–239. doi: 10.1080/08959420801977632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu S, Liang J. China: population aging and old age support. In: Bengtson VL, Kim K, Myers GC, Eun K, editors. Ajging in East and West: families, states, and the elderly. New York (NY): Springer; 2000. pp. 59–93. Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhan HJ, Liu G, Guan X, Bai HG. Recent developments in institutional elder care in China: changing concepts and attitudes. J Aging Soc Policy. 2006;18(2):85–108. doi: 10.1300/J031v18n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations. World population prospects: the 2010 revision. New York (NY): United Nations; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang K. Beijing:China National Committee on Aging. Press release, The National Study of Disability and Functional Limitations of the Elderly. 2011 Mar 1; Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peng R, Ling L, He Q. Self-rated health status transition and long-term care need, of the oldest Chinese. Health Policy. 2010;97(2–3):259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikels C. Chinese kinship and the state: shaping of policy for the elderly. In: Maddox G, Lawton MP, editors. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics. Vol. 13. New York (NY): Springer; 1993. pp. 123–146. Chapter 6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sher AE. Aging in post-Mao China: the politics of veneration. Boulder (CO): Westview Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin D. Aging in China: a tradition under stress: who will care for the nation’s elders? AARP Bulletin [serial on the Internet] 2008 Jul; [cited 2012 Nov 5. Available from: http://www.aarp.org/politics-society/around-the-globe/info-07-2008/aging_in_china_a_tradition_ under_stress.html.

- 14.Jiang L. Changing kinship structure and its implications for old-age support in urban and rural China. Population Studies. 1995;49(1):127–145. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H. Who will care for our parents? Changing boundaries of family and public roles in providing care for the aged in urban China. Care Manag J. 2007;8(1):39–46. doi: 10.1891/152109807780494087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giles J, Wang D, Zhao C. Can China’s rural elderly count on support from adult children? Implications of rural-to-urban migration. J Popul Ageing. 2010;3:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou RJ. Filial piety by contract? The emergence, implementation, and implications of the “family support agreement” in China. Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):3–16. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Chen S. Aging, living arrangements, and housing in China. Ageing Int. 2011;36(4):463–474. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan X, Zhan HJ, Liu G. Institutional and individual autonomy: investigating predictors of attitudes toward institutional care in China. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2007;64(1):83–107. doi: 10.2190/J162-6L63-0347-8762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caring for the elderly: new homes for the old: old-people’s homes are full, as attitudes to the elderly change. Economist. 2012 Apr 21; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhan HJ, Feng X, Luo B. Placing elderly parents in institutions in urban China: a reinterpretation of filial piety. Res Aging. 2008;30(5):543–571. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip W, Hsiao WC. The Chinese health system at a crossroads. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(2):460–468. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Y, Zhang L, Chen Q. China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme for rural residents: popularity of broad coverage poses challenges for costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(5):1058–1064. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.State Council. Guiding principles for piloting the New Rural Pension Insurance Program [Internet] Beijing: State Council; 2009. [updated 2009 Sep 4; cited 2012 Aug 25]. Chinese. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2009-09/04/content_1409216.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yip WC, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu S, Ma J, Maynard A. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex healthcare reforms. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):833–842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S. Social policy of the economic state and community care in Chinese culture: aging, family, urban change, and the socialist welfare pluralism. Brookfield (VT): Avebury; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shang X. Moving toward a multilevel and multi-pillar system: changes in institutional care in two Chinese cities. J Soc Policy. 2001;30(2):259–281. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croll EJ. Social welfare reform: trends and tensions. China Q. 1999;159:684–699. doi: 10.1017/s030574100000343x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong L, Tang J. Non-state care homes for older people as third sector organisations in China’s transitional welfare economy. J Soc Policy. 2006;35(2):229–246. [Google Scholar]

- 30.State Council. The 12th five-year plan for the development of social services for the aged (2011–2015) Beijing: State Council; 2011. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu D, Dupre ME, Liu G. Characteristics of the institutionalized and community-residing oldest-old in China. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(4):871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu LW, Chi I. Nursing homes in China. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(4):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Until now, the last tier of the system—institutional services—has always been officially emphasized and called “supplement” instead of “support.” A key policy maker at the Ministry of Civil Affairs confirmed to the first author of this article that this is merely a wording change, not a shift in policy direction or focus. It was a tactic deemed necessary for securing more funds for developing elder care services from the central government’s budgets for the next five years.

- 34.China publishes a white paper on its undertakings for the aged. China .org.cn [serial on the Internet] 2006 Dec 12; [cited 2012 Nov 5. Available from: http://www.china.org.cn/english/China/191990.htm.

- 35.Wu B, Carter MW, Goins RT, Cheng C. Emerging services for community-based long-term care in urban China: a systematic analysis of Shanghai’s community-based agencies. J Aging Soc Policy. 2005;17(4):37–60. doi: 10.1300/J031v17n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang M. Virtual Elder Care Home born in Suzhou [Internet] 2007 Nov 14; [cited 2012 Nov 5]. Chinese. Available from: http://su.people.com.cn/GB/channel238/277/200711/14/7078.html.

- 37.Virtual Elder Care Homes being established in all Gansu counties and districts this year. China Lanzhou Net [serial on the Internet] 2012 Feb 9; [cited 2012 Nov 5]. Chinese. Available from: http://ent.lanzhou.cn/system/2012/02/09/010086487.shtml.

- 38.Ministry of Civil Affairs, China National Committee on Aging. Basic situation of aged care services nationwide: a collection. Beijing: China Society Publishing House; 2010. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministry of Civil Affairs, China National Committee on Aging. Policy documents on aged care services nationwide: a collection. Beijing: China Society Publishing House; 2010. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu B, Mao ZF, Zhong R. Long-term care arrangements in rural China: review of recent developments. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(7):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.According to officials in the Ministry of Civil Affairs, in a 2011 interview with the first author of this article in Beijing.

- 42.Troianovski A. Housing operators put focus on China. Wall Street Journal. 2011 Mar 9; [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grunbaum R. Seattle firms plan senior housing for China’s booming elderly population. Seattle Times. 2011 Sep 10; [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ministry of Civil Affairs. Provisional measures for the management of social welfare institutions. Beijing: The Ministry; 1999. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ministry of Construction, Ministry of Civil Affairs. The code for design of buildings for elderly persons (JGJ 122–99) Beijing: The Ministry; 1999. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministry of Civil Affairs. Basic standards for social welfare institutions for the elderly (MZ008-2001) Beijing: The Ministry; 2001. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ministry of Labor and Social Security. National occupational standards for old-age care workers. Beijing: The Ministry; 2002. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 48.According to officials in the Tianjin Municipal Bureau of Civil Affairs, in a 2011 interview with the first author of this article in Tianjin