Abstract

The hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) transcriptional complex is regulated by cellular oxygen levels and growth factors. The phosphoinosotide 3-kinase (PI-3K)-Akt/protein kinase B (PKB) pathway has been shown to regulate HIF-1 activity in response to oncogenic signals and growth factors. We assessed whether the HDM2 oncoprotein, a direct target of Akt/PKB, could regulate HIF-1α expression and HIF-1 activity under normoxic conditions. We found that growth factor stimulation, overexpression of Akt/PKB, or loss of PTEN resulted in enhanced expression of both HIF-1α and HDM2. Growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α was ablated by transient expression of a dominant negative form of Akt/PKB or by treatment with LY294002. Transient expression of HDM2 led to increased expression of HIF-1α. Pulse-chase and cycloheximide experiments revealed that HDM2 did not significantly affect the half-life of HIF-1α. Growth factor-induced HIF-1α and HDM2 proteins were localized to the nucleus, and induction of both proteins was observed in both p53+/+ and p53−/− HCT116 cells to comparable levels. Importantly, insulin-like growth factor 1-induced HIF-1α expression was observed in p53-null mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) but was significantly impaired in p53 Mdm2 double-null MEFs, indicating a requirement for Mdm2 in this process. Finally, we showed that phosphorylation at Ser166 in HDM2 contributed in part to growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α. Our study has important implications for the role of the PI-3K-Akt/PKB-HDM2 pathway in tumor progression and angiogenesis.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is a transcriptional complex consisting of alpha (α) and beta (β) subunits. HIF-1 links hypoxic stress to tumor progression and angiogenesis in most human cancers by targeting the expression of a myriad of genes involved in vascularization (VEGF and erythropoietin genes), metabolic adaptation (glucose transporter and glycolytic enzyme genes), and cell survival (insulin-like growth factor 1 [IGF-1] and 2 and insulin genes) (15). HIF-1 activity is dependent on the availability of the α subunit, which is regulated by cellular oxygen and growth factors. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is degraded by targeted ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome (10, 17, 24, 37). This negative regulation is mediated by direct binding of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein, which is a component of an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Binding of VHL to HIF-1α is dependent on prolyl hydroxylation at residues Pro402 and Pro564 (18) and acetylation at Lys532 (19) of HIF-1α. In response to hypoxia, HIF-1α is stabilized and localized to the nucleus, where it binds to HIF-1β to form the HIF-1 complex (20). HIF-1 specifically binds to hypoxia response elements (HRE) within target genes and recruits the coactivator CREB-binding protein/p300 to activate transcription (2).

HIF-1α is overexpressed in many human cancers and correlates with a poor prognostic outcome (15). Loss of p53 (31), germ line mutations in VHL (24), deletion of PTEN (39), or activating mutations in Ras (7) all lead to increased HIF-1 activity. Of particular interest is that both HIF-1α and the HDM2 oncoprotein can be regulated by the same stimuli: growth factor stimulation (4, 13); genetic alterations, such as activating mutations in Ras (7, 32); loss of PTEN (25, 39); or amplification of the HER2/neu tyrosine kinase receptor (21). Hdm2 is a direct transcriptional target of the p53 tumor suppressor protein, and HDM2 itself regulates cell proliferation by inactivating p53 transcriptional activity and targeting it for ubiquitin-mediated degradation (36). However, p53-independent mechanisms also exist to induce HDM2 expression. For example, expression of Hdm2 is induced by the Raf/MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway (32), and activation of the serine-threonine kinase Akt/protein kinase B (PKB) by growth factors can also increase HDM2 expression (4). Induction of HDM2 by either of these events leads to a proliferative advantage, at least in part by inactivating p53 (26). Overexpression of HDM2 is observed in many tumors and correlates with increased proliferation and tumor growth (30). Interestingly, HDM2 can also confer a growth advantage to cells in the absence of p53 (11), and combined expression of HDM2 with adenovirus E1A and Ha-RasV12 is sufficient to convert a normal human cell into a cancer cell (33).

HIF-1α protein levels have been shown to be upregulated by activated Akt/PKB (39) via a VHL-independent mechanism (7, 9). Growth factors, such as IGF-1, induce HIF-1α protein expression by enhancing protein synthesis (13, 14). Recent studies have shown that HIF-1α expression is sensitive to rapamycin, an inhibitor of the mammalian target of the rapamycin protein (mTOR), a downstream target of Akt/PKB (16, 35). However, HIF-1α induction by insulin is less sensitive to rapamycin than treatment with the phosphoinosotide 3-kinase (PI-3K) inhibitor LY294002 (35). Although this may suggest a dose-response differential, it may also suggest that other potential downstream targets of PI-3K-Akt/PKB are involved in regulating HIF-1α expression.

In this study, we assessed the role of the HDM2 oncoprotein in the regulation of HIF-1α expression in response to growth factor stimulation in the context of signaling downstream of PI-3K-Akt/PKB. We show that both HDM2 and HIF-1α proteins are upregulated by IGF-1 stimulation or by expression of activated Akt/PKB. We show that growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α is ablated by expression of a kinase-dead form of Akt/PKB or by treatment of cells with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002. Importantly, we show that both HDM2 and HIF-1α induction in response to IGF-1 is independent of p53 and that induction of HIF-1α is dependent on HDM2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs and antibodies.

A full-length human HIF-1α expression construct (pCMVβ-HA-HIFα) was provided by Andrew Kung (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, Mass.). Plasmids encoding wild-type HDM2 (pCHDM-1A) and human p53 (p53-FLAG pCDNA3) were provided by Karen Vousden and have been described previously (4, 22). The HDM2-S166D mutant was generated from wild-type pCHDM-1A by using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), as described previously (4). The plasmid encoding wild-type Akt/PKB (pCDNA3-Akt) and kinase-dead Akt/PKB (pCDNA3-179A-Akt) were provided by David Stokoe (University of California at San Francisco). The pGL-HRE luciferase reporter construct was provided by Giovanni Melillo (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md.). An HIF-1α-specific monoclonal antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences. HDM2-specific Ab-1 and human p53 (DO1) monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Oncogene Science (Cambridge, Mass.). A β-actin-specific monoclonal antibody was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). An anti-Akt polyclonal antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.), and an anti-phospho-Akt (Ser 473) polyclonal antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, Mass.).

Cell culture.

The human osteosarcoma cell lines U2OS and Saos-2 (p53-null) were used for transient transfection assays. The human primary diploid fibroblast cell line MRC-5, the human glioma cell line U87MG, and the human colorectal cell line HCT116 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The p53−/− and p53−/− Mdm2−/− double-null mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) were a gift from Karen Vousden. The p53+/+ HCT116 and p53−/− HCT116 matched human colorectal cell lines have been described previously (8). HIF-1α tetracycline (TetOn)-inducible cells were established by stable transfection of pTRE-HIF-1α into the Saos-2 TetOn primary cell line. The Saos-2 TetOn primary cell line has been described previously (29). The U2OS-HRE-luc stable cell lines were generated by cotransfecting the pGL-HRE luciferase reporter construct (pGL-HRE) with the pSV2 vector into U2OS cells and then selecting with hygromycin. All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Gibco-BRL) containing 10% fetal calf serum and cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Transient transfections were carried out using the calcium phosphate precipitation method, and cells were harvested either in NP-40 lysis buffer (100 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl2, 1% NP-40) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (EDTA free; Boehringer Mannheim) or in 2× sample buffer (125 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.01% bromophenol blue, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol) for subsequent separation by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis as previously described (4). Transient overexpression of wild-type Akt/PKB by calcium phosphate precipitation resulted in phosphorylation at Ser473 and was consistent with our previous observations (4). While performing experiments using a number of cell lines (HCT116, MRC-5, U2OS, Saos-2, and MCF-7), we noted that HIF-1α induction was barely detectable in response to IGF-1 treatment when cells were starved in 0.1% fetal bovine serum or in serum-free conditions for 24 h (see Fig. 1A, lane 2). We found that in order to obtain a robust and reproducible induction of HIF-1α under these conditions, basal HIF-1α levels needed to be minimally increased prior to growth factor stimulation by addition of a proteasome inhibitor, by exogenous expression of HIF-1α, or by constitutive activation of Akt/PKB. Alternatively, cells needed to be starved for at least 36 h prior to IGF-1 treatment to obtain a robust and reproducible induction of HIF-1α. For treatment with IGF-1, cells were starved for 36 to 48 h and then stimulated with 100 ng of recombinant IGF-1 (Sigma) per ml for 6 h. However, for experiments using either primary human fibroblasts (MRC-5) or primary MEFs, treatments were based on previous studies using primary human fibroblasts (4). Cells were starved for 24 h and then treated with 50 μM MG132 (Calbiochem) for 3 h to boost the levels of endogenous HIF-1α or HDM2 proteins prior to stimulation with IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for a further 4 to 6 h. Western blots were quantified by densitometric analysis to assess the relative levels of HIF-1α protein in response to IGF-1 treatment compared with the control. For experiments using the PI-3K inhibitor, cells were treated with 10 μM LY294002 (Calbiochem) for approximately 30 min prior to growth factor stimulation.

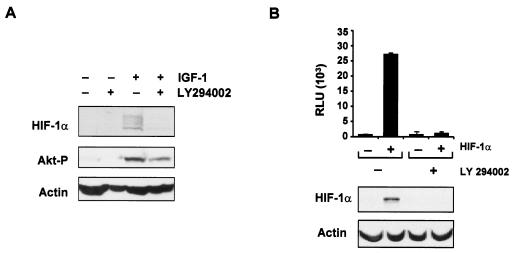

FIG. 1.

HIF-1α expression is regulated by growth factor stimulation and the PI-3K-Akt/PKB signaling pathway. (A) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and phosphorylated Akt (Akt-P) (Ser473) proteins from HCT116 cells treated with LY294002 (10 μM) for 30 min prior to stimulation with IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. β-Actin expression was used as a load control in all experiments. (B) Inhibition of PI-3K ablates HIF-1 activity. U2OS cells stably expressing pGL-HRE (U2OS-HRE-luc) were transiently transfected with either 5 μg of the pCMV control vector (−) or 5 μg of HIF-1α (pCMVβ-HA-HIF-1α) (+) expression constructs. pCMV-β-Gal (50 ng) was cotransfected in all experiments as an internal transfection control. LY294002 (10 μM) was added for 6 h prior to harvest, and HIF-1 activity was determined by luciferase assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate, with the standard deviation indicated. Activity is expressed as RLU standardized to β-Gal expression. The lower panel shows Western blot analysis of HIF-1α expression. β-Actin expression was used as the load control.

Pulse-chase and cycloheximide assays.

U2OS cells were seeded at 0.5 × 106 cells onto 6-cm-diameter plates in duplicate and transiently transfected the next day with either the pCMV control vector or 10 μg of pCMVβ-HA-HIF-1α with or without 5 μg of the pCHDM-1A expression construct. The following day, cells were starved for 48 h and/or incubated with or without IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h and then treated with 50 μg of cycloheximide (Sigma) per ml for 0, 30, and 60 min before lysis; SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analysis were then performed. Alternatively, plates transfected in parallel were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated in 2 ml of methionine-cysteine-free DMEM (Gibco-BRL) containing 10% dialyzed fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL) and 250 μCi of [35S]methionine/cysteine (Trans 35S-Label; ICN) for 60 min. Cells were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline, and 4 ml of complete medium (cold DMEM-10% fetal calf serum) was added. Cells were harvested at 0, 15, 30, and 60 min in NP-40 lysis buffer. HIF-1α protein was immunoprecipitated on protein A-Sepharose beads (50% slurry), using an HIF-1α monoclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals). Radiolabeled HIF-1α protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis and quantified by densitometric analysis. Western blot analysis was then performed to determine immunoprecipitated HIF-1α levels to assess load, and levels were quantified by densitometric analysis. All values were corrected relative to the load control and represented graphically.

Reporter assays.

To assay for HIF-1 activity in U2OS-HRE-luc cells or parental control cells, cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in six-well plates and transiently cotransfected with either 5 μg of pCMV control vector or 5 μg of pCMVβ-HA-HIF-1α. pCMV-β-Gal (50 ng) was cotransfected in all experiments as an internal transfection control. The following day, LY294002 was added at 10 μM for approximately 6 h, followed by lysis with 200 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity (measured as relative light units [RLU]) was determined by using the luciferase reporter system (Promega) and standardized to β-galactosidase (β-Gal) expression.

Immunostaining.

HCT116 cells were plated onto 10-cm-diameter plates containing 1-cm-diameter sterile glass cover slips. Cells were starved in serum-free DMEM for 36 h and then incubated with or without IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. Cells were stained for HDM2 and HIF-1α as previously described (4) using monoclonal antibodies specific to HDM2 and HIF-1α. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to visualize the nucleus.

RESULTS

HIF-1α expression is regulated by growth factor stimulation and the PI-3K-Akt/PKB signaling pathway.

HIF-1α expression is upregulated in response to growth factor stimulation (13, 21), and this appears to be mediated by an effect on HIF-1α protein synthesis via a mechanism that is not yet clear (21). We showed that HIF-1α protein levels were rapidly increased in response to IGF-1 treatment of HCT116 cells (Fig. 1A), consistent with previous studies (13, 21). The induction of HIF-1α was concurrent with phosphorylation of Akt/PKB at Ser 473 (Fig. 1A). In response to growth factor stimulation, the PI-3K-Akt/PKB signaling pathway has been shown to positively regulate HIF-1α protein levels and HIF-1 activity (39). Indeed, we found that IGF-1-mediated induction of HIF-1α expression in HCT116 cells could be inhibited by brief pretreatment of these cells with the PI-3K inhibitor LY294002 prior to IGF-1 stimulation (Fig. 1A). Finally, LY294002 also blocked expression of HIF-1α in U2OS cells stably expressing an HRE-luciferase reporter construct. This led to significant inhibition of HIF-1 activity in these cells (Fig. 1B). LY294002 had negligible effects on U2OS cells stably expressing a control luciferase reporter construct (data not shown). Taken together, our data suggest that the PI-3K signaling pathway is important for HIF-1α induction in response to IGF-1 and HIF-1 activity under normoxic conditions.

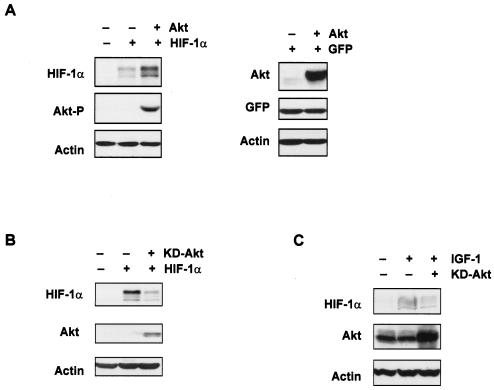

Growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α requires activation by Akt/PKB.

The serine-threonine kinase Akt/PKB is a downstream target of PI-3K and is activated in response to growth factor stimulation (12). We next addressed whether expression of Akt/PKB was sufficient to increase HIF-1α levels. Transient coexpression of Akt/PKB with HIF-1α in U2OS cells greatly enhanced HIF-1α expression as compared with the cDNA vector control (Fig. 2A, left panel). Induction of HIF-1α by Akt/PKB was not mediated by a general effect on the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, since Akt/PKB expression did not affect the pCMV-GFP control, as shown in Fig. 2A, right panel, and as we have previously shown (4). HIF-1α expression was significantly reduced by exogenous expression of a kinase-dead (inactive) form of Akt/PKB (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, expression of a kinase-dead form of Akt/PKB blocked endogenous HIF-1α induction in response to IGF-1 treatment (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these observations support a role for the PI-3K-Akt/PKB pathway in the regulation HIF-1α expression and HIF-1 activity under normoxic conditions and demonstrate that Akt/PKB activity is important for HIF-1α induction in response to growth factors. Since we (data not shown) and others (39) have observed that HIF-1α and Akt/PKB do not directly associate in coimmunoprecipitation assays, we wondered how Akt/PKB might mediate this effect on HIF-1α.

FIG. 2.

Growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α requires activation by Akt/PKB. (A) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and phosphorylated Akt (Akt-P) (Ser473) or total Akt proteins from U2OS cells which were transiently cotransfected with 10 μg of the pCMV vector control (−), HIF-1α expression constructs, and/or 5 μg of Akt expression constructs. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) (1 μg) was used as a transfection control as previously described (4). (B) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α or total Akt proteins from U2OS cells transiently cotransfected with either the pCMV vector control (−), 10 μg of HIF-1α, and/or 5 μg of kinase-dead (KD)-Akt expression constructs. (C) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and Akt proteins from U2OS cells transiently cotransfected with either 5 μg of the pCMV vector control (−) or 5 μg of KD-Akt expression constructs. Cells were starved for 36 h posttransfection and then stimulated with IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. β-Actin expression was used as the load control in all experiments.

HDM2 expression is regulated by the PI-3K-Akt/PKB signaling pathway.

The HDM2 oncoprotein has profound effects on cell proliferation and tumor growth. HDM2 is a transcriptional target of p53 (36); however, growth factor signaling also upregulates HDM2 expression (4). Recently, we showed that the HDM2 oncoprotein is a direct target of Akt/PKB (4). Like HIF-1α expression (Fig. 2A), we have previously shown that expression of HDM2 in U2OS cells was also induced by Akt/PKB (4), and like HIF-1α (Fig. 2B), HDM2 protein levels have also been shown to be reduced by expression of a kinase-dead (inactive) form of Akt/PKB (25).

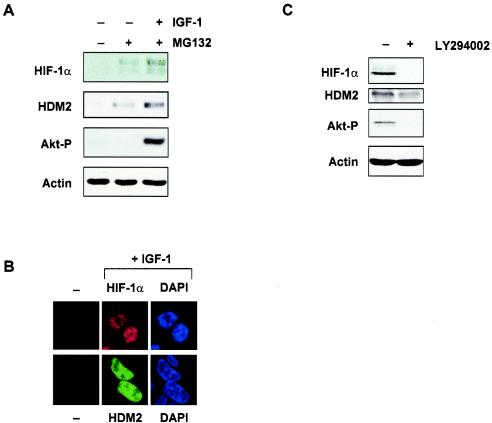

Having established that both HIF-1α and HDM2 were sensitive to induction by Akt/PKB, we next sought to determine whether both HDM2 and HIF-1α were concurrently induced in response to growth factor stimulation. To address this, we used primary human fibroblasts cells, since we had previously shown HDM2 induction by IGF-1 in these cells (4). MRC-5 cells were starved overnight in serum-free conditions and then incubated with or without the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (50 μM) for 3 h to boost the levels of endogenous HIF-1α and HDM2 proteins immediately prior to IGF-1 stimulation (Fig. 3A). HIF-1α induction by IGF-1 was concurrent with the induction of HDM2 and phosphorylation of Akt/PKB at Ser473 (Fig. 3A). It was clear from our studies that Akt/PKB activation could lead to simultaneous induction of both HDM2 and HIF-1α. Furthermore, we showed that both HIF-1α and HDM2 proteins colocalized to the nucleus in response to IGF-1 (Fig. 3B). It is possible that high levels of both HDM2 and HIF-1α would be observed in cancer cells containing constitutively activated Akt/PKB. To address this, we used the human glioma cell line U87MG. These cells are PTEN-null, and as a result, the endogenous Akt/PKB is constitutively activated (25). We showed that basal HDM2 and HIF-1α protein levels were easily detectable in U87MG cells (Fig. 3C) as compared with all other cell lines used in this study. Importantly, both HDM2 and HIF-1α proteins levels could be significantly reduced by brief treatment with LY294002, with a concurrent ablation of Akt phosphorylation at Ser473, suggesting that the detectable HDM2 and HIF-1α levels observed in these cells were due to activation of the PI-3K pathway and Akt/PKB. Thus, our data so far suggest that expression of both HDM2 and HIF-1α could be upregulated by growth factor-mediated activation of Akt/PKB or oncogenic signaling via the PI-3K-Akt/PKB pathway.

FIG. 3.

HDM2 expression is regulated by the PI-3K-Akt/PKB signaling pathway. (A) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α, HDM2, and phosphorylated Akt (Akt-P) (Ser473) proteins from primary human fibroblasts (MRC-5 cells). Cells were starved overnight and then treated with MG132 (50 μM) for 3 h, followed by incubation with or without IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of HIF-1α (upper panels) and HDM2 (lower panels) proteins in HCT116 cells before treatment (−) and after treatment with IGF-1 (+IGF-1). Cells were counterstained with DAPI to localize the nucleus. (C) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α, HDM2, and phosphorylated Akt (Akt-P) (Ser473) proteins from U87MG cells treated or not treated with LY294002 (10 μM) 30 min prior to lysis. β-Actin expression was used as the load control in all experiments.

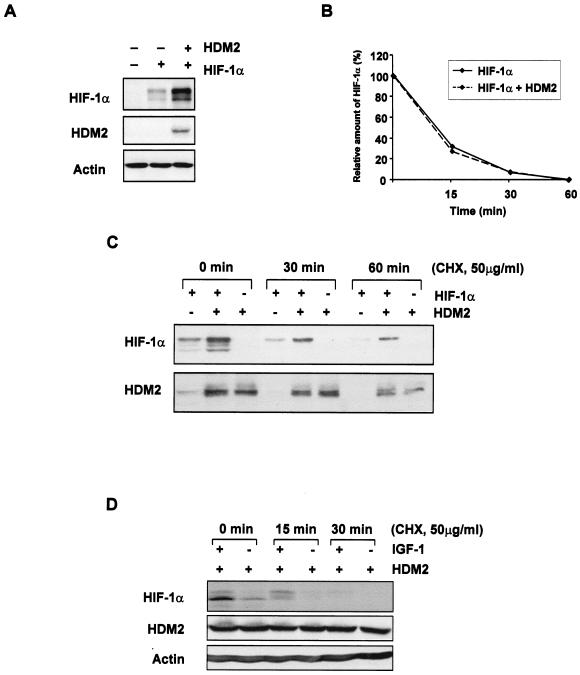

The HDM2 oncoprotein enhances HIF-1α expression.

Since HDM2 has been shown to be a direct downstream target of Akt/PKB (4) and is coregulated with HIF-1α, we next sought to determine whether HDM2 itself could regulate HIF-1α protein expression. Coexpression of HDM2 with HIF-1α greatly increased HIF-1α protein levels in U2OS cells (Fig. 4A). The ability of HDM2 to increase HIF-1α levels did not appear to be due to an increase in protein stability. The half-life of HIF-1α protein in the presence of HDM2 did not significantly change as compared with that of HIF-1α alone when assessed by pulse-chase analysis (Fig. 4B) or when assessed over a time course in the presence of cycloheximide (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, HDM2 could induce endogenous HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 4D), and this induction could be further increased by treatment of cells with IGF-1 (Fig. 4D). Previous studies have shown that HIF-1α levels induced in cells in response to hypoxia or a hypoxia mimetic agent remain constant over a 60-min period in the presence of cycloheximide (21), indicating an effect on protein stability. The observations that HDM2 did not affect HIF-1α levels in this way and that HIF-1α was significantly degraded by 15 min in the presence of cycloheximide either in the presence or absence of IGF-1 suggested that HDM2 was affecting HIF-1α protein synthesis (Fig. 4D). Our data are consistent with a previous study that showed that growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α was not due to an increase in the half-life of the protein but indicated that there was an effect on protein synthesis (21).

FIG. 4.

The HDM2 oncoprotein enhances HIF-1α expression. (A) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and HDM2 proteins from U2OS cells that were transiently cotransfected with either the pCMV vector control (−), 10 μg of HIF-1α, and/or 5 μg of HDM2 expression constructs. (B) Graphical representation of radioactively labeled HIF-1α protein transfected as described in panel A. Transiently transfected U2OS cells were pulse-labeled with methionine-cysteine-free medium containing [35S]methionine/cysteine and chased with unlabeled complete medium for the times indicated. (C) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and HDM2 proteins from U2OS cells which were transiently cotransfected as described in panel A and then treated with 50 μg of cycloheximide (CHX)/ml for the times indicated prior to harvesting. (D) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and HDM2 proteins from HCT116 cells, which were transiently transfected with 10 μg of HDM2 expression plasmid, starved for 36 h, stimulated with IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h, and then treated with 50 μg of cycloheximide/ml for the times indicated prior to harvesting.

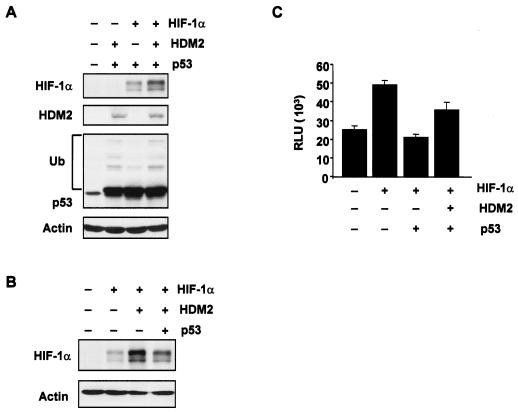

We next sought to determine whether HDM2 could upregulate HIF-1α expression in the presence of p53 (under normoxic conditions). The p53 tumor suppressor protein has been shown to negatively regulate HIF-1α expression (31) and HIF-1 activity (6) under hypoxic conditions. We found that transient coexpression of HDM2 in U2OS cells also enhanced HIF-1α protein levels in the presence of p53, although the effect was less than that observed in the absence of p53 (Fig. 5A and B). Interestingly, HDM2 was able to ubiquitinate p53 in the presence of HIF-1α to a level similar to that observed for HDM2 in the absence of HIF-1α (Fig. 5A). This is consistent with studies showing that p53 is degraded when HDM2 is induced in response to growth factors (4, 26). Using a HIF-1α tetracycline-inducible system, we showed that expression of HDM2 was able to relieve p53-mediated inhibition of HIF-1 activity (Fig. 5C) at least in part by targeting p53 for degradation (data not shown). These observations suggest that expression of HDM2 can lead to both upregulation of HIF-1α levels and the targeted ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p53. It was important therefore to address whether induction of HIF-1α in this way could occur in the absence of p53.

FIG. 5.

HDM2-mediated effects in the presence of p53. (A and B) U2OS cells were transiently cotransfected with the vector control (−), 10 μg of HIF-1α, 5 μg of HDM2, and/or 5 μg of p53-FLAG expression constructs. Western blot analysis was carried out using specific antibodies against HIF-1α, p53, and HDM2. Ub, ubiquitinated p53. (C) Saos-2 HIF-1α TetOn-inducible cells were transiently cotransfected with the pGL-HRE plasmid and 2.5 μg of either the vector control (−), p53-FLAG, or HDM2 expression constructs, followed by doxycycline treatment (6 μg/ml) for 24 h. pCMV-β-Gal (50 ng) was cotransfected in all experiments as an internal transfection control. HIF-1 activity was determined by luciferase assay. Experiments were performed in duplicate, with the standard deviation indicated. Activity is expressed as RLU standardized to β-Gal expression.

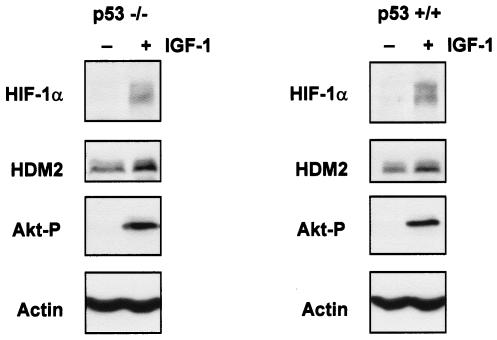

Induction of HIF-1α protein expression by growth factors is p53 independent but requires HDM2.

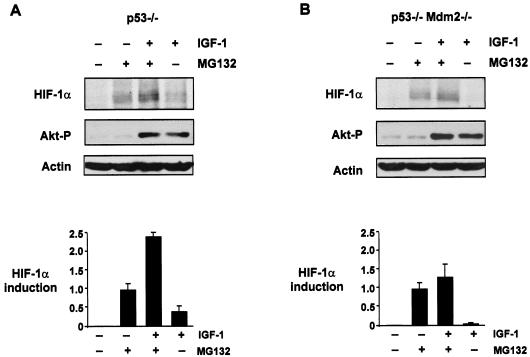

Most human tumors have lost p53 function due to mutation of the gene or deregulation of the pathways that lead to p53 activation (36). We therefore wanted to determine whether HIF-1α protein could be induced by growth factors in the absence of p53. As shown in Fig. 6, HIF-1α was induced to comparable levels in p53−/− HCT116 and p53+/+ HCT116 cells in response to IGF-1 stimulation. This was concurrent with an increase in HDM2 expression and activation of Akt/PKB (Fig. 6), suggesting that induction of HDM2 and HIF-1α by growth factors is independent of p53 status. Since HDM2 could induce HIF-1α expression in the absence of p53 and growth factor-mediated induction of both HIF-1α and HDM2 was also independent of p53, we next sought to determine whether HDM2 was required for the induction of HIF-1α protein expression in response to IGF-1. Therefore, we starved p53−/− or p53−/− Mdm2−/− MEFs overnight in serum-free conditions and then treated the cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for approximately 3 h to boost the basal levels of endogenous HIF-1α protein. Then, cells were stimulated with IGF-1 for 6 h. Induction of HIF-1α protein in response to IGF-1 treatment was observed in the p53−/− MEFs in the presence or absence of MG132 (Fig. 7A). This was consistent with our observations for p53−/− HCT116 cells (Fig. 6) and Saos-2 (p53-null) cells (data not shown). However, induction of HIF-1α protein expression was significantly reduced in the p53−/− Mdm2 −/− MEFs in response to IGF-1 treatment either in the presence or absence of MG132 (Fig. 7B) compared with our observations for p53−/− MEFs (Fig. 7A). Our data suggest that HDM2 is required for HIF-1α induction in response to IGF-1.

FIG. 6.

Induction of HIF-1α protein expression by growth factors is p53 independent. (A) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α, HDM2, and phosphorylated Akt (Akt-P) (Ser473) proteins from p53−/− HCT116 (left panel) or p53+/+ HCT116 cells (right panel) starved for 36 h prior to IGF-1 treatment (100 ng/ml) for 6 h.

FIG. 7.

Induction of HIF-1α protein expression by growth factors requires HDM2. Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and phosphorylated Akt proteins from p53−/− (A) or p53−/− Mdm2−/− (B) MEFs starved overnight and then treated with MG132 (50 μM) for 3 h, followed by incubation with or without IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. β-Actin expression was used as the load control. Graphs are representative of two independent experiments and show the relative amounts of HIF-1α induced for each treatment as outlined. HIF-1α levels from Western blot analyses were measured by densitometric analysis and quantified relative to the actin load control.

Role of HDM2 phosphorylation in growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α.

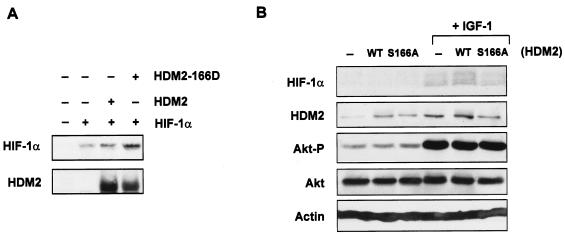

One of the major sites for Akt/PKB phosphorylation in HDM2 is at residue Ser166 (4, 26, 38). We next sought to determine whether phosphorylation of HDM2 was important for HIF-1α induction. Coexpression of HDM2 in Saos-2 cells (p53-null) led to enhanced HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 8A); importantly, however, expression of a mutant form of HDM2, containing an aspartic acid substitution at Ser166 (S166D), which mimics phosphorylation by Akt/PKB (4), further increased HIF-1α expression compared to wild-type HDM2 (Fig. 8A), implicating a role for this site in regulating HIF-1α induction. To address this further, we assessed the contribution of this site to HIF-1α induction in response to growth factor stimulation. As shown in Fig. 8B, wild-type HDM2 expression and endogenous HDM2 were enhanced by IGF-1 treatment of HCT116 cells and led to an increase in endogenous HIF-1α levels as compared to untreated controls. However, substitution of serine with alanine at residue 166 within HDM2 rendered HDM2 less sensitive to IGF-1 and impaired HDM2's ability to induce HIF-1α in response to IGF-1 treatment, suggesting that phosphorylation at this site contributes at least in part to growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α.

FIG. 8.

Role of HDM2 phosphorylation in growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α. (A) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and HDM2 proteins from Saos-2 cells (p53-null) after transient cotransfection with the pCMV vector control, 10 μg of HIF-1α, 5 μg of wild-type HDM2 (HDM2), and/or 5 μg of mutant HDM2-S166D expression constructs. (B) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α, HDM2, phosphorylated Akt (Akt-P) (Ser473), and total Akt proteins from HCT116 cells transiently transfected with either 10 μg of the pCMV vector control (−), wild-type (WT) HDM2, or mutant HDM-S166A (S166A) expression constructs. Cells were then starved for 36 h and treated with or without IGF-1 (100 ng/ml) for 6 h prior to harvest. β-Actin expression was used as the load control in all experiments.

DISCUSSION

An understanding of underlying mechanisms involved in the ability of a cell to activate HIF-1 in response to both hypoxic stress and oncogenic signals has important implications for how these processes become deregulated in human cancer (15). An adaptation to microenvironmental stimuli such as hypoxia and growth factors in combination with genetic lesions provide malignant cells with the ability to form hypoxic vascular solid tumors, which are aggressive and metastatic. Treatment of these tumors by conventional therapies correlates with a poor prognostic outcome (34). At least two mechanisms exist to regulate HIF-1α expression and thus HIF-1 activity. In response to hypoxia, HIF-1α expression is upregulated at the level of protein stability by inhibition of prolyl hydroxylation and subsequent inhibition of ubiquitin-mediated degradation by VHL (10, 17, 24, 37). However, in response to growth factor stimulation, HIF-1α expression is upregulated at the level of protein synthesis (21).

In this study, we addressed how growth factors enhance HIF-1α expression, with specific focus on the link between HIF-1α expression, the serine-threonine kinase Akt/PKB, and the oncoprotein HDM2. We showed that IGF-1-mediated induction of HIF-1α was ablated by transient expression of a dominant negative form of Akt/PKB or by treatment with LY294002, indicating that Akt/PKB activity is important for HIF-1α induction in response to IGF-1. In support of this, we showed that activated Akt/PKB enhances HIF-1α expression, consistent with a previous study (39). HIF-1α protein induced by expression of activated Akt/PKB has been shown to be constitutively hydroxylated at proline 564, suggesting that a VHL-independent mechanism is involved (9). The observation that Akt/PKB and HIF-1α do not interact directly (39) suggested that downstream targets of Akt/PKB might be involved in this regulation. Indeed, recent studies have implicated the downstream effector of Akt/PKB, mTOR, in the regulation of HIF-1α expression (16, 35). We were interested therefore in addressing how other Akt/PKB targets may regulate HIF-1α expression.

We have recently identified the HDM2 oncoprotein as a direct downstream target of Akt/PKB (4). HDM2 expression is upregulated by Akt/PKB-mediated phosphorylation, leading to the targeted ubiquitination and degradation of the p53 tumor suppressor protein (4, 26, 38). Indeed, we found that IGF-1 stimulation, transient expression of Akt/PKB, or loss of PTEN resulted in enhanced expression of both HIF-1α and HDM2. Transient expression of HDM2 led to increased expression of HIF-1α, and this could be enhanced further by aspartic acid substitution at Ser166 within HDM2, which mimics phosphorylation by Akt/PKB (38). Although HDM2 could clearly enhance HIF-1α protein levels, we found that this was not mediated by an effect on HIF-1α protein stability but indicated an effect on HIF-1α protein synthesis. These observations were consistent with a previous study showing that growth factor-mediated induction of HIF-1α was not due to an increase in the half-life of the protein, but affected HIF-1α protein synthesis (21). The possibility that HDM2 may also affect HIF-1α protein synthesis was particularly interesting. HDM2 has been shown to bind to ribosomal proteins and might function to regulate processes such as ribosomal biogenesis and transport and protein synthesis/translation (23). Importantly, we found that although IGF-1-mediated induction of HIF-1α and HDM2 was independent of p53, HDM2 was required for induction of HIF-1α by IGF-1 in MEFs and that phosphorylation of HDM2 at Ser166 contributed to this process. Under normoxic conditions, we showed that HDM2 could induce HIF-1α and simultaneously target p53 for degradation when overexpressed. This may indicate a potential cellular mechanism that would allow HIF-1 to be activated in the absence of any potential negative regulation by p53. Activation of the PI-3K pathway in tumor cells by growth factor stimulation or via loss of PTEN or amplification of HER2 (neu), for example, would presumably lead to a proliferative advantage through increased expression of HDM2 and HIF-1α, as well as the ablation of p53 function. The ability of HDM2 to be upregulated by growth factors and oncogenes, together with its ability to induce HIF-1α expression, reveals a potential novel role for HDM2 in tumor progression. ′

The predominant pathway for inducing HIF-1α in response to hypoxia appears to be via inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase and subsequent inhibition of VHL binding; however, the PI-3K pathway has been shown by some groups also to contribute to HIF-1α induced by hypoxic stress (7, 27). A recent report has demonstrated that the PI-3K signaling pathway is important for early HIF-1α induction in hypoxia (27). However, in some reports it has been argued that activation of the PI-3K pathway is insufficient for the induction of HIF-1α in response to hypoxia (1, 3). The difficulty in pinpointing a precise role for PI-3K in hypoxia-mediated induction of HIF-1α may be explained by the observations that the activation of PI-3K in response to hypoxia appears to be cell type specific and that the requirement for the PI-3K pathway in the induction of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions is temporally dependent (27). Nevertheless, the possibility that activation of the PI-3K pathway by oncogenic signals may contribute to hypoxia-mediated signaling to HIF-1 is particularly interesting.

An abnormally growing cancer cell within a tumor mass would potentially experience stimulation by both hypoxia and growth factors. An important question is how these converging stimuli affect the overall outcome for HIF-1α and its contribution to tumor progression. We would predict that the induction of HIF-1α would be greatly augmented if these pathways were to cooperate. Indeed, several studies support this idea (13, 28). We also noted that induction of HIF-1α protein levels could be dramatically increased if cells were starved for at least 36 h prior to IGF-1 treatment or if basal HIF-1α levels were minimally increased prior to growth factor stimulation by addition of a proteasome inhibitor, by exogenous expression of HIF-1α, or by constitutive activation of Akt/PKB. These observations may also indicate that growth factor and oncogenic signaling pathways cooperate with other signals to increase HIF-1α expression and/or that oncogenic signals may need to cooperate with other pathways to effectively drive HIF-1α expression. Our study clearly shows that HDM2-mediated positive regulation of HIF-1α by growth factor signals is independent of p53. However, we found that overexpression of p53 could negatively regulate HIF-1. We have previously shown that p53 is stabilized in response to multiple stressors, including hypoxic stress (5). Interestingly, p53 does not transcriptionally target HDM2 in response to hypoxic stress in a number of human tumor cell lines (5). It will be interesting to establish whether loss or deregulation of p53, or other tumor suppressors such as VHL or PTEN, affect HIF-1-mediated tumor progression by cooperating with the PI-3K-Akt/PKB-HDM2 pathway.

Our study reveals a novel role for the HDM2 oncoprotein in the positive regulation of HIF-1α and has important implications for the role of the PI-3K-Akt/PKB-HDM2 pathway in tumor proliferation and angiogenesis and how we might target this pathway therapeutically.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amato Giaccia (Stanford University, Stanford, Calif.) and Gregg Semenza (Johns Hopkins University Medical School, Baltimore, Md.) for helpful suggestions regarding growth factor induction of HIF-1α. Thanks to Paul Workman (Institute of Cancer Research, Sutton, Surrey, United Kingdom), Christine Blattner (Institute of Genetics and Toxicology, Karlsruhe, Germany), and Neville Ashcroft (DNA Damage and Stability Centre, University of Sussex, Sussex, United Kingdom) for their critical review of the manuscript and helpful discussions. We thank Karen Vousden (Beatson Institute, Glasgow, United Kingdom) for the MEFs. Finally, we thank Alan Lehmann (DNA Damage and Stability Centre, University of Sussex), Nina Perusinghe, and all other members of the Ashcroft laboratory for their input and support.

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK (CRC grant C309/A2984) and the Institute of Cancer Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez-Tejado, M., A. Alfranca, J. Aragones, A. Vara, M. O. Landazuri, and L. del Peso. 2002. Lack of evidence for the involvement of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway in the activation of hypoxia-inducible factors by low oxygen tension. J. Biol. Chem. 277:13508-13517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arany, Z., L. E. Huang, R. Eckner, S. Bhattacharya, C. Jiang, M. A. Goldberg, H. F. Bunn, and D. M. Livingston. 1996. An essential role for p300/CBP in the cellular response to hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:12969-12973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arsham, A. M., D. R. Plas, C. B. Thompson, and M. C. Simon. 2002. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling is neither required for hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1 alpha nor sufficient for HIF-1-dependent target gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 277:15162-15170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashcroft, M., R. L. Ludwig, D. B. Woods, T. D. Copeland, H. O. Weber, E. J. MacRae, and K. H. Vousden. 2002. Phosphorylation of HDM2 by Akt. Oncogene 21:1955-1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashcroft, M., Y. Taya, and K. H. Vousden. 2000. Stress signals utilize multiple pathways to stabilize p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3224-3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blagosklonny, M. V., W. G. An, L. Y. Romanova, J. Trepel, T. Fojo, and L. Neckers. 1998. p53 inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-stimulated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 273:11995-11998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blancher, C., J. W. Moore, N. Robertson, and A. L. Harris. 2001. Effects of ras and von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene mutations on hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha, HIF-2alpha, and vascular endothelial growth factor expression and their regulation by the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 61:7349-7355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunz, F., P. M. Hwang, C. Torrance, T. Waldman, Y. Zhang, L. Dillehay, J. Williams, C. Lengauer, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1999. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J. Clin. Investig. 104:263-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan, D. A., P. D. Sutphin, N. C. Denko, and A. J. Giaccia. 2002. Role of prolyl hydroxylation in oncogenically stabilized hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 277:40112-40117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cockman, M. E., N. Masson, D. R. Mole, P. Jaakkola, G. W. Chang, S. C. Clifford, E. R. Maher, C. W. Pugh, P. J. Ratcliffe, and P. H. Maxwell. 2000. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25733-25741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubs-Poterszman, M. C., B. Tocque, and B. Wasylyk. 1995. MDM2 transformation in the absence of p53 and abrogation of the p107 G1 cell-cycle arrest. Oncogene 11:2445-2449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franke, T. F., S. I. Yang, T. O. Chan, K. Datta, A. Kazlauskas, D. K. Morrison, D. R. Kaplan, and P. N. Tsichlis. 1995. The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell 81:727-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuda, R., K. Hirota, F. Fan, Y. D. Jung, L. M. Ellis, and G. L. Semenza. 2002. Insulin-like growth factor 1 induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression, which is dependent on MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in colon cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:38205-38211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross, T. S., N. Akeno, T. L. Clemens, S. Komarova, S. Srinivasan, D. A. Weimer, and S. Mayorov. 2001. Selected contribution: osteocytes upregulate HIF-1alpha in response to acute disuse and oxygen deprivation. J. Appl. Physiol. 90:2514-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris, A. L. 2002. Hypoxia—a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:38-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson, C. C., M. Liu, G. G. Chiang, D. M. Otterness, D. C. Loomis, F. Kaper, A. J. Giaccia, and R. T. Abraham. 2002. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α expression and function by the mammalian target of rapamycin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7004-7014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivan, M., K. Kondo, H. Yang, W. Kim, J. Valiando, M. Ohh, A. Salic, J. M. Asara, W. S. Lane, and W. G. Kaelin, Jr. 2001. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 292:464-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaakkola, P., D. R. Mole, Y. M. Tian, M. I. Wilson, J. Gielbert, S. J. Gaskell, A. Kriegsheim, H. F. Hebestreit, M. Mukherji, C. J. Schofield, P. H. Maxwell, C. W. Pugh, and P. J. Ratcliffe. 2001. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292:468-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeong, J. W., M. K. Bae, M. Y. Ahn, S. H. Kim, T. K. Sohn, M. H. Bae, M. A. Yoo, E. J. Song, K. J. Lee, and K. W. Kim. 2002. Regulation and destabilization of HIF-1alpha by ARD1-mediated acetylation. Cell 111:709-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang, B. H., J. Z. Zheng, S. W. Leung, R. Roe, and G. L. Semenza. 1997. Transactivation and inhibitory domains of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Modulation of transcriptional activity by oxygen tension. J. Biol. Chem. 272:19253-19260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laughner, E., P. Taghavi, K. Chiles, P. C. Mahon, and G. L. Semenza. 2001. HER2 (neu) signaling increases the rate of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) synthesis: novel mechanism for HIF-1-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3995-4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohrum, M. A., M. Ashcroft, M. H. Kubbutat, and K. H. Vousden. 2000. Identification of a cryptic nucleolar-localization signal in MDM2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:179-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marechal, V., B. Elenbaas, J. Piette, J. C. Nicolas, and A. J. Levine. 1994. The ribosomal L5 protein is associated with mdm-2 and mdm-2-p53 complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:7414-7420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell, P. H., M. S. Wiesener, G. W. Chang, S. C. Clifford, E. C. Vaux, M. E. Cockman, C. C. Wykoff, C. W. Pugh, E. R. Maher, and P. J. Ratcliffe. 1999. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399:271-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayo, L. D., J. E. Dixon, D. L. Durden, N. K. Tonks, and D. B. Donner. 2002. PTEN protects p53 from Mdm2 and sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapy. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5484-5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayo, L. D., and D. B. Donner. 2001. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway promotes translocation of Mdm2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:11598-11603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mottet, D., V. Dumont, Y. Deccache, C. Demazy, N. Ninane, M. Raes, and C. Michiels. 2003. Regulation of HIF-1alpha protein level during hypoxic conditions by the PI3K/AKT/GSK3beta pathway in HepG2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 33:31277-31286. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pennacchietti, S., P. Michieli, M. Galluzzo, M. Mazzone, S. Giordano, and P. M. Comoglio. 2003. Hypoxia promotes invasive growth by transcriptional activation of the met protooncogene. Cancer Cell 3:347-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips, A. C., M. K. Ernst, S. Bates, N. R. Rice, and K. H. Vousden. 1999. E2F-1 potentiates cell death by blocking antiapoptotic signaling pathways. Mol. Cell 4:771-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polsky, D., K. Melzer, C. Hazan, K. S. Panageas, K. Busam, M. Drobnjak, H. Kamino, J. G. Spira, A. W. Kopf, A. Houghton, C. Cordon-Cardo, and I. Osman. 2002. HDM2 protein overexpression and prognosis in primary malignant melanoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94:1803-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravi, R., B. Mookerjee, Z. M. Bhujwalla, C. H. Sutter, D. Artemov, Q. Zeng, L. E. Dillehay, A. Madan, G. L. Semenza, and A. Bedi. 2000. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Genes Dev. 14:34-44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ries, S., C. Biederer, D. Woods, O. Shifman, S. Shirasawa, T. Sasazuki, M. McMahon, M. Oren, and F. McCormick. 2000. Opposing effects of Ras on p53: transcriptional activation of mdm2 and induction of p19ARF. Cell 103:321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seger, Y. R., M. Garcia-Cao, S. Piccinin, C. L. Cunsolo, C. Doglioni, M. A. Blasco, G. J. Hannon, and R. Maestro. 2002. Transformation of normal human cells in the absence of telomerase activation. Cancer Cell 2:401-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semenza, G. L. 2002. HIF-1 and tumor progression: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol. Med. 8:S62-S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treins, C., S. Giorgetti-Peraldi, J. Murdaca, G. L. Semenza, and E. Van Obberghen. 2002. Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27975-27981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vousden, K. H. 2002. Activation of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1602:47-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu, F., S. B. White, Q. Zhao, and F. S. Lee. 2001. HIF-1alpha binding to VHL is regulated by stimulus-sensitive proline hydroxylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9630-9635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou, B. P., Y. Liao, W. Xia, Y. Zou, B. Spohn, and M. C. Hung. 2001. HER-2/neu induces p53 ubiquitination via Akt-mediated MDM2 phosphorylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:973-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zundel, W., C. Schindler, D. Haas-Kogan, A. Koong, F. Kaper, E. Chen, A. R. Gottschalk, H. E. Ryan, R. S. Johnson, A. B. Jefferson, D. Stokoe, and A. J. Giaccia. 2000. Loss of PTEN facilitates HIF-1-mediated gene expression. Genes Dev. 14:391-396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]