Abstract

This retrospective study reports patient signalment, method of diagnosis and geographic distribution, and examines trends in prevalence and seasonal distribution of blastomycosis cases submitted to a veterinary diagnostic laboratory in Saskatchewan over a 21-year period. Of the 143 cases that originated from Saskatchewan and Manitoba 137 were from canine and 6 from feline patients. Signalment was similar to that previously reported. All cases originated in southern Saskatchewan and Manitoba, primarily from Regina, Moose Jaw, Swift Current, and Winnipeg. Case numbers showed a significant increase in the period 2001 to 2010 compared to 1990 to 2000. Seasonally, there was an increasing trend in the number of diagnoses from February to November. There was no correlation between average seasonal temperature or average seasonal total precipitation and the number of cases of blastomycosis. The persistence of blastomycosis in southern Saskatchewan indicates that Blastomyces dermatitidis is now endemic in this region.

Résumé

Prévalence et répartition géographique de la blastomycose canine et féline dans les Prairies canadiennes. Cette étude rétrospective présente un rapport sur le signalement du patient, la méthode de diagnostic et la répartition géographique et examine les tendances de prévalence et répartition saisonnière des cas de blastomycose soumis à un laboratoire de diagnostic vétérinaire en Saskatchewan pendant une période de 21 ans. Parmi les 143 cas qui provenaient de la Saskatchewan et du Manitoba, 137 étaient issus de patients canins et 6 de patients félins. Le signalement était semblable à celui antérieurement déclaré. Tous les cas provenaient du sud de la Saskatchewan et du Manitoba, surtout de Regina, de Moose Jaw, de Swift Current et de Winnipeg. Le nombre de cas a affiché une hausse importante pendant la période de 2001 à 2010 comparativement à la période de 1990 à 2000. Sur le plan saisonnier, il se produisait une tendance à la hausse du nombre de diagnostics de février à novembre. Il n’y avait aucune corrélation entre la température saisonnière moyenne ou le total des précipitations saisonnières moyennes et le nombre de cas de blastomycose. La persistance de la blastomycose dans le sud de la Saskatchewan indique que Blastomyces dermatitidis est maintenant endémique dans cette région.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Blastomycosis is a systemic mycotic infection caused by the dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, with most cases acquired by inhalation of the spores from the environment (1). The reservoir for B. dermatitidis is thought to be soil; however, organisms have only been successfully cultured from the environment 21 times, despite thousands of attempts (2). This disease is endemic in the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio River valleys, the mid-Atlantic states, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec, Manitoba, and Ontario (1). Although blastomycosis was first reported in dogs in Saskatchewan in 1973 (3), with an additional 19 cases between 1981 and 1986 (4), Saskatchewan has only rarely been included in the literature as an endemic region (4,5). The purpose of the present study was to describe cases of blastomycosis on the Canadian prairies, verify the persistence of blastomycosis in Saskatchewan since the initial reports, and illustrate endemicity of blastomycosis in southern regions of the province.

Materials and methods

Description of cases

Laboratory records from the Prairie Diagnostic Services (PDS) database, at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, between January 1990 and March 2011 were searched. Cases that originated in Saskatchewan or Manitoba and contained a definitive diagnosis of Blastomyces dermatitidis were included in the study. Details of signalment (including species, age, gender, and breed) were recorded, as well as the diagnostic tests that were done, and the geographic origin of the patient sample. Species and gender were evaluated as proportions of the total blastomycosis cases, and age was analyzed for median values and range. A search was also performed for total canine laboratory submissions between January 1990 and March 2011, which were subclassified by breed and submitting clinic (i.e., geographic distribution). Breed data from the blastomycosis group were divided into breed groups, as were the data from total PDS submissions. The top 3 breed groups were ranked for the blastomycosis cases, total PDS submissions, and blastomycosis cases as a proportion of PDS submissions by breed as a descriptive method of comparison. Geographic distribution of blastomycosis cases was mapped. Reference to total laboratory submissions from the same geographic locations is reported to exclude the influence of submission bias.

Description of trends

Canine data from January 1990 to December 2010 was isolated, with a matching search of the database performed for total canine biopsy, cytology, and necropsy submissions over the same time period. Data for both the blastomycosis group and total submission group, were batched by year, month, and season. Seasons were as follows: spring (March to May), summer (June to August), fall (September to November), and winter (December to February). Trends in the annual prevalence of canine blastomycosis over the 21-year period, relative to total annual canine submissions for the specified diagnostic methods, were determined. Using Fisher’s exact test and chi-squared test, the number of cases from 1990 to 2000 were compared with the number of cases from 2001 to 2010, as well as by year within each of these time periods. Using a chi-squared test, the number of blastomycosis cases was compared between seasons over the 21-year period, with and without taking into account the corresponding total seasonal canine submissions for the specified diagnostic methods.

Historical mean temperatures (°C) and total precipitation (mm), were obtained from the Environment Canada Web site (6) from January 1990 to December 2010 for the 2 regions in Saskatchewan with the highest incidence of blastomycosis (Regina and Moose Jaw). Weather data for Moose Jaw were collected from Moose Jaw Station A from January 1990 until June 1998 when data were no longer available. Weather data from that time point until December 2010 were collected from the Moose Jaw CS station. There was a 0.3 m change in elevation, and less than 1 minute difference in the latitude and longitude between these Moose Jaw weather stations, thus the continuity of the data was considered intact. Similarly, weather information data were initially collected from the Regina International Airport from January 1990 until September 2008, after which data were no longer available. From October 2008 until December 2010, data from the Regina RCS station were used. There was a change in elevation between these two stations of 0.3 m, but no change in the longitude or latitude. Weather information collected from these sites was considered representative of the southern regions of the province for the purpose of statistical analysis. Average seasonal temperature and total precipitation from each city were examined relative to the seasonal distribution of Saskatchewan blastomycosis cases, through the calculation of a Spearman “r” value, to look for a relationship between weather patterns and occurrence of disease. Case numbers were evaluated relative to the corresponding seasonal weather data, and relative to the weather data for the previous season. EpiInfo 6 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

The PDS laboratory, the sole provider of veterinary diagnostics in Saskatchewan, also receives a wide array of submissions from the surrounding western provinces. A review of canine cytology, biopsy, and necropsy submissions from January 1990 to December 2010 revealed that PDS serviced 115 of the 131 veterinary clinics located in Saskatchewan. The clinics were widely dispersed throughout the province and were located in 17 of the 18 census divisions in Saskatchewan. The vast majority of the clinics serviced represent general practices with the exception of a single large referral center (WCVM Veterinary Medical Center).

Description of cases

A total of 151 confirmed blastomycosis cases were submitted to PDS between January 1990 and March 2011. Of these, 108 originated in Saskatchewan, 35 were from Manitoba, 4 were from Ontario (specifically the endemic area of Kenora), 2 were from British Columbia, and 1 each was from Alberta and Wisconsin, USA. The 143 cases from Manitoba and Saskatchewan were included in the study. Of the 108 cases originating from Saskatchewan, 102 were canine patients, and 6 were feline patients. All 35 cases from Manitoba were canine. During the same time period, there was a total of 256 080 canine laboratory submissions to PDS.

Of the canine Blastomyces positive submissions, 128 had the age of the patient listed, while the age was unknown in 9 cases. The median age of canine patients was 3.0 y (range 0.5 to 14 y), with most cases (54%) being between the ages of 1 and 3 y. The median age of the 6 feline patients was 4 y (range: 2 to 9 y). Gender was reported in 136/137 canine submissions. Male dogs comprised 58% of the cases; 66% of these dogs were neutered. Female dogs comprised 42% of the cases and 70% of these were neutered. The feline cases involved 5 neutered males and 1 neutered female. The patient’s breed was reported on 134 of the canine submissions. Breed distribution is tabulated with subclassification based on the American Kennel Club groups (Table 1). The sporting group comprised the majority of cases (52%), followed by the working group (18%), herding group (7%), hound and toy groups (6% each), non-sporting and terrier groups (4% each), and unclassified breeds (2%). When total PDS submissions for the same time period were ranked by breed, the sporting group also predominated (24%), but herding (18.2%) and non-sporting (17.2%) groups were ranked second and third, respectively. The ranking order differed again when blastomycosis case breed numbers were evaluated as a proportion of the total PDS submissions by breed. In this case the sporting group again predominated, but the second and third ranking went to the working group and hounds, respectively. For most individual breeds listed, their representation in the current study correlated well with their representation when all canine submissions to PDS over the 21-year period were taken into account. However, Labrador retrievers (21.2% compared to 6.5%, P < 0.00001) and golden retrievers (13.9% compared to 4.5%, P < 0.00001) were overrepresented in the current study compared with the proportion of these breed submissions to PDS. Five of the feline patients were domestic shorthair cats, and 1 of the patients was a Persian.

Table 1.

Breed distribution of canine blastomycosis cases from Saskatchewan and Manitoba between January 1990 and March 2011 (n = 137)

| Working group (n = 25) | Sporting group (n = 71) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| Breed | Number | Breed | Number |

| Rottweiler | 6 | Labrador retriever | 29 |

| Rottweiler X | 1 | Labrador retriever X | 7 |

| Mastiff breeds | 3 | Golden retriever | 19 |

| Doberman pinscher | 3 | Golden retriever X | 1 |

| Siberian husky | 2 | Cocker spaniel | 6 |

| Siberian husky X | 1 | Cocker spaniel X | 3 |

| Boxer | 2 | Spaniel X | 3 |

| Akita | 1 | Brittany spaniel | 1 |

| Alaskan malamute | 1 | Chesapeake Bay retriever | 1 |

| Greater Swiss mountain dog | 1 | German shorthair pointer | 1 |

| Standard schnauzer | 1 | ||

| Great dane | 1 | ||

| Great Pyrenees | 1 | ||

| Saint bernard | 1 | ||

|

| |||

| Hound group (n = 8) | Herding group (n = 10) | ||

|

|

|

||

| Breed | Number | Breed | Number |

|

| |||

| Basset hound | 2 | German shepherd dog | 3 |

| Beagle | 1 | German shepherd dog X | 2 |

| Bloodhound | 1 | Collie X | 3 |

| Dachshund | 1 | Border collie | 1 |

| Norwegian elkhound | 1 | Shetland sheepdog X | 1 |

| Whippet | 1 | ||

| Whippet X | 1 | ||

|

| |||

| Non-sporting group (n = 6) | Terrier group (n = 6) | ||

|

|

|

||

| Breed | Number | Breed | Number |

|

| |||

| Dalmatian | 2 | Jack Russell terrier | 2 |

| Poodle | 1 | Terrier X | 2 |

| Poodle X | 1 | Miniature schnauzer | 1 |

| Boston terrier | 1 | Staffordshire terrier | 1 |

| Lhasa apso X | 1 | ||

|

| |||

| Toy group (n = 8) | Other (n = 3) | ||

|

|

|

||

| Breed | Number | Breed | Number |

|

| |||

| Shih tzu | 4 | Unclassified | 3 |

| Shih tzu X | 3 | ||

| Papillion | 1 | ||

Each patient (n = 143) was evaluated for the types of submissions used in the diagnosis of blastomycosis. Cytology was diagnostic for blastomycosis in 101 patients. These submissions were most frequently from skin lesions (36%), respiratory tract (32%) (including bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, transtracheal wash fluid, and sputum samples), and lymph node (17%). The remaining samples originated from the vitreous humor (7%), synovial fluid (3%), urine (2%), nasal cavity (2%), and there was a single sample of unknown origin. Surgical biopsy was diagnostic for blastomycosis in 53 patients. Skin biopsies (46%) or submission of an entire ocular globe (37%) were the most common of these submissions. The remaining samples were from lymph node (4%), tongue (4%), bone lesions (4%), respiratory tract (2%), endometrium (2%), testicle (2%), and mass lesions within a body cavity (2%). Culture was used in conjunction with cytology and/or histopathology in 11 cases, and was the basis for diagnosis in 1 case in which postmortem tissue was submitted for culture only. A diagnosis of blastomycosis was made on necropsy in 10 patients. When feline cases were examined separately, cytology was diagnostic in 4/6 cases, with samples originating from skin (2), lymph node (1), and lung (1). Surgical biopsy of lymph node was diagnostic in 1 case. Culture was used in conjunction with positive cytology and histopathology in 1/6 patients. In 2 patients necropsy was a means of diagnosis.

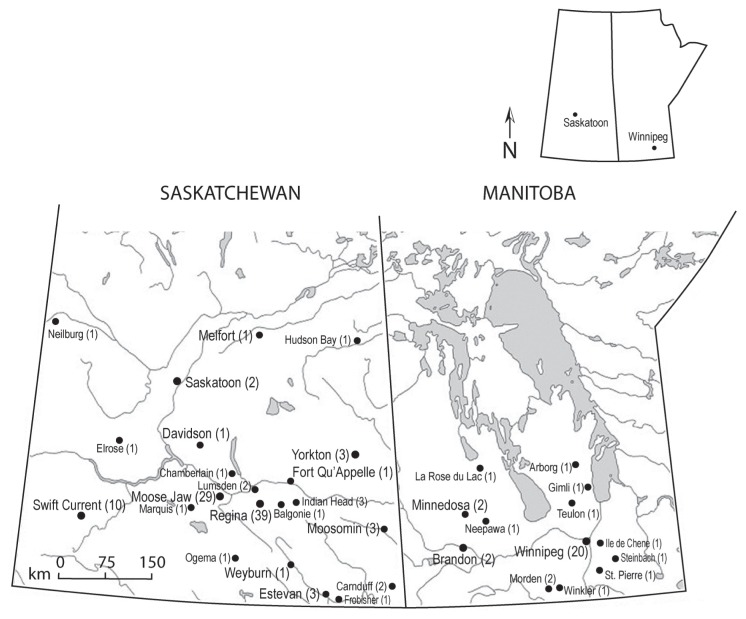

All of the cases originated in the southern half of both Saskatchewan and Manitoba (Figure 1). The majority of Saskatchewan cases (n = 108) originated in Regina (36%), Moose Jaw (27%), and Swift Current (9%), while cases originating in Winnipeg (57%) dominated the submissions from Manitoba (n = 35). Only 2 cases (1.9%) of blastomycosis were identified in Saskatoon. In comparison, of the total number of canine cytology, biopsy, and necropsy submissions to PDS over the same time period, 4.8%, 2.1%, 1.5%, and 0.6% of cases originated from Saskatoon, Regina, Swift Current, and Moose Jaw, respectively. Feline cases originated from Regina (3/6), Swift Current (2/6), and Moose Jaw (1/6).

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of canine and feline blastomycosis cases in Saskatchewan and Manitoba between January 1990 and March 2011 (n = 143).

Feline cases were diagnosed sporadically between 1990 and 2011, with 1 case diagnosed in each of 1999, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2011. Seasonal distribution of blastomycosis in feline patients was limited to the first 7 mo of the year, with 1 case each in January, February, June, and July, and 2 cases in April. Feline cases were too few to assess significance of annual or seasonal distribution of the diagnosis.

Description of trends

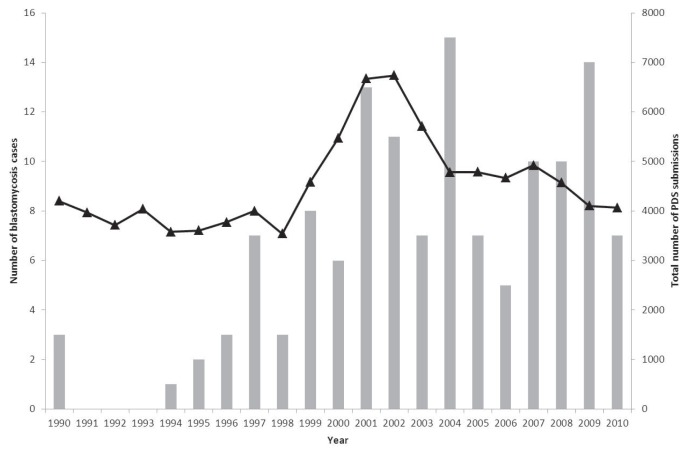

Between January 1990 and December 2010 there were 95 479 canine biopsy, cytology, and necropsy submissions to PDS. From these submissions 132 cases of canine blastomycosis were diagnosed, of which 98 were from Saskatchewan and 34 from Manitoba. Annual distribution of these cases, relative to total annual canine submissions for the specified diagnostic methods, is shown in Figure 2. When total laboratory submissions were taken into account, the 5 years in which the occurrence of blastomycosis was highest ranked as follows: 2009, 2004, 2008, 2007, and 2001. When the 5 years with the lowest occurrence were ranked, 1991, 1992, and 1993 shared first place with zero submissions, followed by 1994, 1995, 1990, and 1996. This trend for low occurrence years to be within 1990 to 2000 and high occurrence years to be within the period 2001 to 2010 is reinforced by a statistically significant difference between the frequencies in these 2 time periods, both with and without consideration of corresponding total canine laboratory submissions (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Annual prevalence of canine blastomycosis in Saskatchewan and Manitoba based on submissions to the Prairie Diagnostic Service between January 1990 and December 2010 (bars), relative to total PDS submissions during the same time period (line) (n = 132).

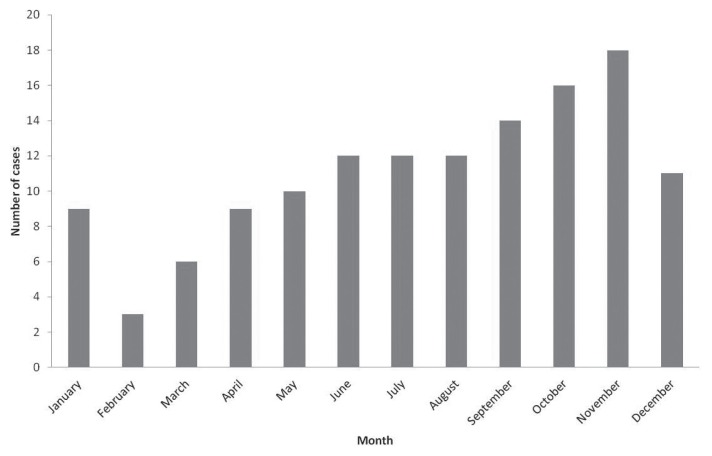

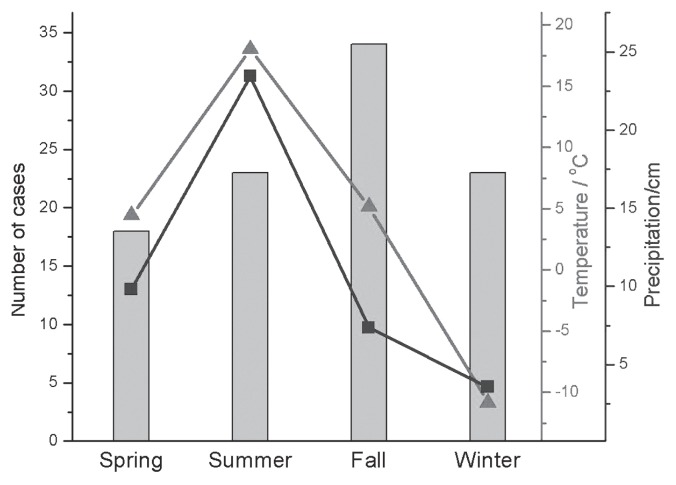

Blastomycosis was diagnosed throughout the year; however, when seasonal distribution of cases from Saskatchewan and Manitoba from January 1990 to December 2010 was evaluated a cyclical pattern was apparent. There was an increasing trend in the number of cases diagnosed from February to November, after which case numbers decreased (Figure 3). When evaluated by season, there was a significant difference between numbers of blastomycosis cases diagnosed in each season, both when total seasonal PDS submissions were, and were not, taken into account (P < 0.001 and P < 0.003, respectively). Blastomycosis was most frequently diagnosed in the fall, followed by summer. Total cytology, biopsy, and necropsy submissions, however, were highest in winter and spring. Weather data from Moose Jaw weather stations, in relation to seasonal distribution of blastomycosis in Saskatchewan, are presented graphically (Figure 4), and the degree of correlation between weather data and cases of blastomycosis, both for the corresponding and previous season, is reported in Table 2. Results for Regina weather data (not shown) were very similar. There was no statistical correlation between the average temperature or average total precipitation and the number of cases of blastomycosis when corresponding seasons were evaluated. The weather data for the previous season appeared to be highly correlated with the number of blastomycosis cases, but the result was only borderline significant.

Figure 3.

Seasonal distribution of canine blastomycosis cases in Saskatchewan and Manitoba between January 1990 and December 2010 (n = 132).

Figure 4.

Average seasonal temperature (triangles, inside right axis) and average total seasonal precipitation (squares, outer left axis) in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan versus number of Saskatchewan blastomycosis cases per season, between January 1990 and December 2010 (n = 98).

Table 2.

Degree of association between positive blastomycosis case numbers and seasonal weather data from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, for the corresponding and previous seasons, respectively. Degree of association is portrayed as a Spearman Correlation Coefficient with associated P-value

| Temperature same season | Precipitation same season | Temperature previous season | Precipitation previous season | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman correlation coefficient | 0.316 | 0.316 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| P-value | 0.684 | 0.684 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

Discussion

The current study examined trends in the seasonal distribution and annual prevalence, and described the patient signalment, and geographic distribution of cases of blastomycosis submitted to a veterinary diagnostic laboratory in Saskatchewan over a 21-year period. In total, 108 cases of blastomycosis were identified in southern Saskatchewan during this period, and consistent with the previous literature, the vast majority of these cases were in dogs.

The patient signalment in cases of canine blastomycosis has been well-documented in the literature. As shown in the present study, canine blastomycosis is most often reported in young (< 2-years-old), large breed dogs, and cases are equally represented across the genders (1,7,8). In the current study, cases of blastomycosis were most frequently observed in sporting breeds. Although the sporting group also predominated in total PDS submissions, when this underlying population was accounted for, the sporting group maintained its relative importance as it relates to blastomycosis. This suggests there is a true predominance of this group in the diseased population. Within the sporting group, Labrador retrievers, and golden retrievers appeared to be overrepresented. This finding may not represent a true breed predisposition, but rather may reflect an occupational hazard of these breeds and increased exposure to the environmental niche of B. dermatitidis. Similarly, the working and hound groups, which were ranked second and third, respectively, when the total laboratory submissions by breed were taken into account, may also hold importance in the blastomycosis demographics. Although the current study demonstrates a trend for canine blastomycosis to be present in young, large, sporting breed dogs, it is important to recognize the wide age range of affected animals and the wide distribution across all breed groups, including toy breeds. Therefore, blastomycosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis in dogs with compatible clinical signs that have travelled to or live in endemic regions of Saskatchewan regardless of their age, gender, or breed.

An unexpected finding in the current study was the diagnosis of blastomycosis in 6 cats resident in Saskatchewan. Blastomycosis is a rare disease of cats (1), and in endemic areas, the estimated annual incidence rate of blastomycosis is thought to be 100-fold lower in cats than in dogs (9). Although feline blastomycosis is uncommon there are approximately 50 cases reported primarily in 2 reviews (10,11) and 2 recent case series (9,12). There are conflicting reports in the literature regarding the signalment of cats with blastomycosis. Some authors have suggested that there are no breed, age, or gender predilections in this species (1). Others have reported a predominance of disease in male cats (9,11). The reason for this suspected gender predilection is unknown, but may be related to behavioral differences between the genders. While male cats predominate in the current study, the total numbers are too low to assign a predilection. Reported breed predispositions have included Siamese (11), Abyssinian (10), Havana brown (10), and domestic shorthair cats (9,12); in the current study most cases were observed in domestic shorthair cats. This finding may simply reflect the composition of the cat population in Saskatchewan. A wide age range is reported in the literature with the age at time of diagnosis ranging from 6 mo to 18 y (11), and the reported mean age ranging from 5.9 y (10) to 7.8 y (12). In accordance with the veterinary literature, the current study demonstrated a wide age range, but a median age lower than those previously reported. The indoor/outdoor status of the cats herein was unknown; therefore, the source of potential exposure also remains unknown. Interestingly, there are reports of blastomycosis in cats that live strictly indoors (9,12) suggesting that a proportion of cats may acquire infection with B. dermatitidis in or very near their homes.

The cornerstone of diagnosis is demonstration of the yeasts, with morphology typical of B. dermatitidis by cytology or histopathology (1). The current study reinforces the utility of cytology in the diagnosis of blastomycosis as 70% of cases were diagnosed by this method. Cytological specimens that facilitated diagnosis included aspirates from skin masses, lymph nodes, vitreous humor, and lung; impression smears from ulcerated skin masses; transtracheal wash; and bronchoalveolar lavage.

Historically, blastomycosis has been associated with a well-defined geographic range and is endemic to the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio River valleys, the mid-Atlantic States, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec, Manitoba, and Ontario (1). The current study identified large numbers of cases of blastomycosis occurring in southern Saskatchewan with most cases consistently occurring in Regina and Moose Jaw regions. This apparent geographic variation in canine blastomycosis is further supported when the geographic distribution of total canine submissions to PDS is examined. Over twice as many canine submissions were received from Saskatoon clinics than from Regina clinics, yet the number of canine blastomycosis cases from Regina was 19 times greater than those reported from Saskatoon. Similarly, almost 8 times the number of canine cases were submitted from Saskatoon than Moose Jaw, but the number of blastomycosis cases reported from Moose Jaw was approximately 15 times greater than that from Saskatoon. These results suggest a true geographic variation in the occurrence of blastomycosis within the province rather than submission bias. The authors conclude that since the first report of canine blastomycosis in Saskatchewan in 1973, increased numbers of cases are being diagnosed and the geographic distribution has remained consistent, indicating that B. dermatitidis is endemic in southern regions of Saskatchewan.

Cases of canine blastomycosis have long been associated with waterways (7,8). A more recent study concluded that in northern Wisconsin, human and dog cases were most commonly associated with residence near low elevation waterways with sandy soils (13). Blastomyces dermatitidis is poorly competitive in the environment, but has the ability to survive harsh conditions and rapid environmental changes that may enable it to temporarily “bloom” (14). Some authors have postulated that sandy soils are prone to daily temperature and moisture extremes that may favor the proliferation of B. dermatitidis(14). However, since successful environmental isolation has been infrequent (2), the ecological niche of this organism remains an enigma. In the current study, although information regarding the proximity of residence to waterways or access to waterways was not available, the geographic distribution of cases in southern Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba closely follows the Qu’Appelle and Assiniboine river systems. There is nothing unique to the soils along these river systems, but similar to most rivers they would be typified by the presence of sandy soils (Dr. Jeff Schoenau, University of Saskatchewan, personal communication, 2012). Whether the soil conditions along these particular river systems favor the growth of B. dermatitidis has not been investigated.

One of the major limitations of the current study was its retrospective nature and the limited historical information that could be gleaned from the case submission forms. As a result, geographic distribution of blastomycosis in Saskatchewan and Manitoba was determined based on the location of the animals at the time of diagnosis. Information regarding travel history to other endemic regions in Canada and the United States was unavailable; thus, the authors cannot eliminate the possibility that a proportion of animals may have been infected with B. dermatitidis outside of the province of Saskatchewan. In addition, visitation of animals to endemic regions either within Saskatchewan or out of province may account for the distribution of sporadic cases within more central regions of the province.

One of the goals of the current study was to examine trends in the incidence of blastomycosis submissions within the province of Saskatchewan. An increasing trend is noted when the number of cases from 1990 to 2000 is compared to the number of cases from 2001 to 2010. The increased number of cases is further supported when total annual laboratory submissions is taken into account; thereby confirming that this trend is not a result of concurrent increased laboratory submissions. However, whether this reflects a true increase in the incidence of blastomycosis within the province is unknown. The results may be confounded by increased veterinary awareness of this disease and the desire to have independent and definitive confirmation of the diagnosis before pursuing expensive therapeutic interventions.

In the current study, there was significant seasonal variation in the diagnosis of blastomycosis, with the majority of cases diagnosed in the fall and summer. This finding was in contrast to the seasons with the highest laboratory submission rates (winter and spring), indicating the trends in submissions was not responsible for the apparent seasonal distribution of blastomycosis. Seasonal variations in the clinical presentation of human cases of blastomycosis have been reported in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario (15). These regions have a climate similar to Saskatchewan, characterized by an early autumn, late spring, and cold winter. Symptoms of blastomycosis were first noted in autumn and winter in 63% of human patients, and the seasonal distribution was influenced by the type (localized versus disseminated) of pulmonary blastomycosis (15). After this peak in disease onset, there was a decrease in occurrence rate to nearly zero by the summer months. Light et al (15) suggest that this observed pattern may reflect acquisition of B. dermatitidis in the summer months and a presymptomatic incubation period of 1 to 6 mo. In the current study, cases of canine blastomycosis were identified in all months of the year although, as in the study by Light et al (15), there was a trend for increased numbers of cases to be recognized in the autumn months which may reflect a summer exposure. Interestingly, unlike human blastomycosis, the summer months constituted the second most common time of diagnosis for canine cases. The reason for this difference is unknown, but could reflect the difference between assessing onset of symptoms in the human study, as opposed to the time of diagnosis in the current study. Information regarding the onset of clinical signs was not available in the current study, and some owners may have sought veterinary medical intervention later in the course of disease. Difference in incubation time, which is reported as variable, but ranging from 2 to 10 wk in dogs (8), or reactivation of infection may also contribute to the discrepancy between the data for the summer months in the 2 studies.

A recent study examining the effect of weather on canine blastomycosis found that when 6-month time periods were the unit of analysis, increased moisture on average 1 y before diagnosis, and lower than average temperature, but higher maximum temperature on average 6 mo prior to diagnosis were associated with increased case numbers (14). In the current study, temperature and precipitation data were compared to number of blastomycosis cases on a seasonal basis rather than 6-month periods. Graphically, both temperature and precipitation tended to follow a similar pattern, and as they increased, or decreased, the number of blastomycosis cases diagnosed in the following season, similarly increased or decreased compared to the previous season. However, the result was not statistically significant when assessing the average temperature or average total precipitation with the corresponding seasonal blastomycosis case numbers. When the weather data from the previous season was compared to the number of blastomycosis positive cases, there was a potential correlation, with a borderline P-value. The inability of the current study to statistically confirm a correlation or test for an association between weather data and the number of reported blastomycosis cases may be a reflection of sample size, and the limitations of this study design. Weather parameters recorded from individual weather stations may not have been representative of the larger geographic area. Although not statistically significant, the strong visual correlation between number of blastomycosis cases and weather data from the previous season is likely worth noting as it suggests potential for the previous season’s weather to influence case numbers. This, in turn, could further support that infection may occur in the summer months in the majority of cases, when both temperature and precipitation are at their highest.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of blastomycosis in southern Saskatchewan has become increasingly more frequent in the last decade. Given the persistence and perceived geographic clustering of cases of blastomycosis in southern Saskatchewan, in particular the Regina and Moose Jaw areas, B. dermatitidis should now be considered endemic in these regions. Veterinarians should be aware of this newly recognized area of endemicity, and should include blastomycosis as a differential diagnosis in dogs and cats with compatible clinical signs and a history of travel to, or residency in, southern Saskatchewan. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Legendre AM. Blastomycosis. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2012. pp. 606–614. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgardner DJ, Paretsky DP. The in vitro isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis from a woodpile in north central Wisconsin, USA. Med Mycol. 1999;37:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoff B. North American blastomycosis in two dogs in Saskatchewan. Can Vet J. 1973;14:122–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harasen GLG, Randall JW. Canine blastomycosis in southern Saskatchewan. Can Vet J. 1986:375–378. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallabh V, Martin T, Conly JM. Blastomycosis in Saskatchewan. West J Med. 1988;148:460–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canada’s National Climate Archive. Environment Canada [home-page on the Internet] [Last accessed May 13, 2013]. Updated 2011 September 14. Available from: http://climate.weatheroffice.gc.ca/climateData/canada_e.html.

- 7.Arceneaux KA, Taboda J, Hosgood G. Blastomycosis in dogs: 115 cases (1980–1995) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998;213:658–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Archer JR, Trainer DO, Schell RF. Epidemiologic study of canine blastomycosis in Wisconsin. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1987;190:1292–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blondin N, Baumgardner DJ, Moore GE, Glickman LT. Blastomycosis in indoor cats: Suburban Chicago, Illinois, USA. Mycopathologia. 2007;163:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s11046-006-0090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies C, Troy GC. Deep mycotic infections in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1996;32:380–391. doi: 10.5326/15473317-32-5-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller PE, Miller LM, Schoster JV. Feline blastomycosis: A report of three cases and literature review (1961 to 1988) J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1990;26:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilor C, Graves TK, Barger AM, O’Dell-Anderson K. Clinical aspects of natural infection with Blastomyces dermatitidis in cats: 8 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;229:96–99. doi: 10.2460/javma.229.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumgardner DJ, Steber D, Glazier R. Geographic information system analysis of blastomycosis in northern Wisconsin, USA: Waterways and soil. Med Mycol. 2005;43:117–125. doi: 10.1080/13693780410001731529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumgardner DJ, Paretsky DP, Baeseman ZJ, Schreiber A. Effects of season and weather on blastomycosis in dogs: Northern Wisconsin, USA. Med Mycol. 2011;49:49–55. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.488658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Light RB, Kralt D, Embil JM, et al. Seasonal variations in the clinical presentation of pulmonary and extrapulmonary blastomycosis. Med Mycol. 2008;46:835–841. doi: 10.1080/13693780802132763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]