Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the utility of subchondral bone texture from a baseline x-ray image for predicting 3-year knee osteoarthritis (OA) progression.

Methods

A total of 138 participants in the Prediction of Osteoarthritis Progression (POP) study were evaluated at baseline and 3 years. Fixed-flexion knee radiographs of the 248 non-replaced knees underwent fractal analysis of the medial subchondral tibial plateau using a commercially available software tool. OA progression was defined as a 1-grade change in joint space narrowing (JSN) or osteophyte based on a standardized knee atlas. Statistical analysis of fractal signatures was performed using a new method based on modeling the overall shape of fractal dimension versus radius curves.

Results

Baseline fractal signature of the medial tibial plateau was predictive of medial knee JSN progression (area under the curve [AUC] of Receiver Operating Characteristic plot of 0.75), but not progression based on osteophyte or progression of the lateral compartment. The traditional covariates (age, gender, body mass index, knee pain), general bone mineral content, and baseline joint space width fared little better than random variables for predicting OA progression (AUC 0.52–0.58). The maximal predictive model combined baseline fractal signature, knee alignment, traditional covariates, and bone mineral content (AUC 0.79).

Conclusions

We identified a prognostic marker of OA that is readily extracted from a plain radiograph by fractal signature analysis. The global shape approach to analyzing these data is a potentially efficient means of identifying individuals at risk of knee OA progression that needs to be validated in a second cohort.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, imaging, biomarker, subchondral bone

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) progression can be defined anatomically by means of plain radiographs, clinically by means of symptoms, or physiologically by means of a functional assessment. Of these three methods of defining OA progression, the anatomical means of assessment has prevailed. The only method currently accepted by regulators for evaluating disease progression in knee OA is the sequential radiographic assessment of joint space narrowing (JSN). Problems with radiographic evaluation of OA include difficulty reproducing patient position in order to measure joint space width, and relative insensitivity to change that requires large studies of 18 to 24 months duration to demonstrate changes. Further, changes in joint space width are confounded by meniscal damage and extrusion, which are also seen in OA (1). Risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), age, and gender are commonly used in OA clinical trials in an attempt to select individuals with greater risk of knee OA progression (2–4). Unfortunately, we do not fully understand the effect or interaction of these predictors and they have not been highly successful. The continued lack of a good predictor has stalled pursuit of treatments for a disease that affects nearly 20% of the population and has a significant impact on productivity and quality of life.

Analyses of bone in OA date back over more than half a century and have provided clear indications that changes in periarticular bone occur very early in OA development (5). The bone architecture on radiographic images of osteoarthritic joints began to be analyzed in the 1990's by Buckland-Wright and colleagues using fractal signature analysis (FSA) (6, 7), a technique first applied in medicine to the study of abnormalities of lung radiographs (reviewed in (7)). FSA evaluates the complexity of detail of a 2-dimensional image (that is a projection of the 3-D bone architecture) at a variety of scales spanning the typical size range of trabeculae (100–300 µm) and trabecular spaces (200–2000 µm) (8). As described by Buckland-Wright and colleagues, the complexity of detail quantified by fractal dimension is determined principally by the number, spacing, and cross-connectivity of trabeculae (9). By nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), another group has determined that the apparent fractal dimension is an index of bone marrow space pore size; pore size is in turn related to, and increases with, perforation and disappearance of trabeculae (10). To date, fractal analysis has been applied successfully to the study of osteoporosis and arthritis of the spine (11–14), hips (15, 16), pre- and post-joint replacement knees (6, 7, 9, 14, 17–26), anterior cruciate ligament ruptured knees (27), wrist (14, 28, 29), and hands (14). Plain radiographs have been used primarily, but this method is amenable to analysis of other image types such as those acquired by computed tomography (11, 12) and NMR (10). One of the greatest advantages to FSA is that it is robust to many of the pitfalls inherent in the gold standard measure of radiographic progression, joint space narrowing. Joint space narrowing is problematic due to the need for high quality images (often beyond the general quality of clinical images) using well-controlled acquisition protocols for extraction of good quantitative data. In particular, FSA has been shown to be robust to varying radiographic exposure, to changing pixel size, and knee repositioning (6). The feasibility of applying FSA in a clinical trial was demonstrated retrospectively by fractal signature analyses of radiographs generated in the two-year longitudinal study of a bisphosphonate for OA (25). Here we have focused on its use for predicting knee OA progression.

Analyses of bone are very pertinent to an understanding of the OA disease process. Bone density measurements have revealed that subchondral and subarticular bone of subregions of the diseased compartment of OA knees are osteoporotic (30, 31). The process of periarticular bone remodeling of OA joints is believed to account for the finding that bone resorption biomarkers are elevated in patients with progressive knee OA (32). These findings are corroborated by biomechanical studies demonstrating that the subchondral bone from OA knees is less stiff and dense with greater porosity and reduced mineral content (33). These findings are compatible with the overall results gleaned from fractal signature analyses of OA knees reported by Buckland-Wright and colleagues, namely decreased fractal dimensions (interpreted as an increase in the thickness) of medium to large horizontal trabecular structures in early OA; and increased fractal dimensions (interpreted as increased fenestration, thinning and thus number) of most sizes of vertical trabecular structures in severe OA (severity defined by joint space widths) (34).

To date, three studies have evaluated tibial cancellous bone changes longitudinally in the context of knee OA progression using FSA but results have been conflicting (19, 21, 25). The first, a study of 240 patients reported in abstract form only, revealed significant differences in the pattern of FSA change (increased vertical FSA of most trabecular sizes and decreased horizontal FSA of large trabeculae) over 12 months between patients with slow (n=240) versus marked (n=12) joint space narrowing (19); these results were interpreted as indicative of local subchondral bone loss coincident with knee OA progression. A second much smaller study (n=40) failed to identify significant differences in the pattern of FSA change over the course of 24 months in slow and fast progressors (21). A third study evaluated FSA change over 3 years in one-third (n=400) of patients in a placebo-controlled trial of a bisphosphonate for knee OA (25). Compared with patients with non-rapid joint space narrowing (JSN), patients with rapid JSN tended to have a greater decrease in the vertical fractal dimensions (interpreted as a greater loss of most sizes of vertical trabeculae), and no significant difference in the horizontal trabeculae. By contrast, the non-progressor group showed a slight decrease in fractal dimensions for vertical and horizontal trabeculae over time and no drug treatment effect. The JSN progressors showed a marked and dose-dependent change in FSA with drug treatment consistent with a preservation of trabecular structure and reversal of the pathological changes with increasing drug dose. As far as we are aware, no prior in vivo study has evaluated the utility of FSA for predicting knee OA progressors from a cohort of knee OA patients. We also sought to address one of the challenges posed by the wealth of excellent prior research in this area, namely, to develop a more holistic method of dealing with the array of variables generated by such analyses. As described here, we addressed this problem with a generalized ‘shape analysis’ of the data that enabled us to create an overall model that was predictive of OA progression independent of other non-radiographic variables.

Methods

Patients

A total of 159 participants (118 female, 41 male) were enrolled in the NIH sponsored Strategies to Predict Osteoarthritis Progression (POP) study, approved and in accordance with the policies of the Duke Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited primarily through Rheumatology and Orthopaedic clinics and met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for symptomatic OA of at least one knee. In addition, all participants met radiographic criteria for OA with a Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) (35) score of 1–3 in at least one knee. Exclusion criteria included the following: bilateral knee KL4 scores; exposure to a corticosteroid (either parenteral or oral) within 3 months prior to the study evaluation; knee arthroscopic surgery within 6 months prior to the study evaluation; known history of avascular necrosis, inflammatory arthritis, Paget’s disease, joint infection, periarticular fracture, neuropathic arthropathy, reactive arthritis, or gout involving the knee, and current anticoagulation. A total of 186 participants were screened to identify the final 159 participants with radiographic and symptomatic knee OA of at least one knee. These analyses focused on the 138 participants (87%) who returned for follow-up evaluation 3 years later. Of the total 276 knees available for analysis, 10 were replaced at baseline and 18 replaced during the period of longitudinal follow-up leaving a total of 248 knees available for the final analyses. Age, gender, and measured body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) were collected as covariates. Knee symptoms were ascertained by the NHANES I criterion (36) of pain, aching or stiffness on most days of any one month in the last year; for subjects answering yes, symptoms were quantified as mild, moderate, or severe yielding a total score of 0–4 for each knee.

Radiographic Imaging

Posteroanterior fixed-flexion knee radiographs were obtained with the SynaFlexer™ lower limb positioning frame (Synarc, San Francisco) with a ten degree caudal x-ray beam angle (37). X-rays were scored for KL grade (0–4), and individual OA radiographic features of joint space narrowing (JSN) and osteophyte (OST) were scored 0–3 using the OARSI standardized atlas (38) for the medial and lateral tibiofemoral compartments. This resulted in total JSN scores of 0–6 and OST scores of 0–12 as all four margins of the knee joint were scored for this feature. Blinded rescoring of 78 knee radiographs was performed to calculate the intrarater reliability of the x-ray readings by weighted kappa statistic, which were as follows: for JSN kappa 0.71 (95% CIs 0.63–0.79); for OST kappa 0.73 (95% CIs 0.67–0.79). For purposes of statistical modeling, knee OA baseline status was defined as the JSN score at baseline. Knee OA progression status was calculated as the change in JSN scores or the change in OST score for the tibiofemoral compartment over 3 years derived from baseline and follow-up x-rays read in tandem by two trained readers (VBK and GM) blinded to the clinical and bone texture data but not blinded to the time sequence. Of the 248 knees available for analysis, 13% were defined as progressors on the basis of increase in joint space narrowing (JSN) over 3 years, and 69% on the basis of increase in osteophyte (OST). The progressor knees in this study were: 18 based on medial JSN, 14 based on lateral JSN, 75 based on medial OST, and 97 based on lateral OST. It was possible to have a change in OST in the absence of JSN change, however, except for one case, all progressors based on JSN also had increasing OST scores. Trabecular bone mineral density (BMD) and bone mineral content (BMC) were measured at the calcaneus of the dominant leg using a Norland ApolloTM DEXA. Knee alignment was measured manually to within 0.5 degrees on a weight-bearing “long-limb” (pelvis to ankle) anteroposterior radiograph as previously reported (39) using the center at the base of the tibial spines as the vertex of the angle.

Image Analysis with the Optasia Knee Analyzer

All X-rays were analyzed using the KneeAnalyzer application developed by Optasia Medical (Manchester, UK). The KneeAnalyzer utilizes computer aided detection based on statistical shape modeling to provide highly reproducible quantitative measurements of the medial compartment of the knee yielding separate vertical and horizontal fractal dimensions over a range of scales related to trabecular dimensions and referred to as signatures. All films were digitized using a VIDAR Diagnostic Pro Plus digitizer at 150 dpi (dots per inch), which converts to a pixel resolution of 169.3 microns. Per the KneeAnalyzer requirements, all films were converted to uncompressed, 8-bit grayscale TIFF format from DICOM using the PixelMed Java DICOM Toolkit (an open source software package distributed by PixelMed Publishing freely available at website www.pixelmed.com). All analyses were performed with the fibula on the left-hand side of the image as viewed by the rater (images were flipped horizontally as necessary). Correction for magnification was achieved by analyst-assisted detection of the vertical column of beads in the SynaFlexer platform by the KneeAnalyzer. Joint segmentation was based on six manually selected initialization points at the lateral femur, medial femur, lateral tibia, medial tibia, lateral tibial spine, and medial tibial spine (Figure 1a). Once the initialization points were selected, the software determined the joint space boundary profiles for both the lateral and medial compartments and automatically identified the rectangular region for fractal signature analysis in the medial subchondral bone based on the medial tibial joint profile (Figure 1b). The FSA region of interest (ROI) spanned ¾ of the tibial compartment width, had a height of 6 mm (determined using SynaFlexer calibration), and left boundary aligned with the tip of the medial tibial spine. This ROI was standardized based on later work by Buckland-Wright who used this to avoid the periarticular osteopenia adjacent to marginal osteophytes (9). From this region, FSA was determined at a range of scales (termed radii) as determined by the software based on the pixel resolution and SynaFlexer calibration. The radii for FSA ranged in dimension from 3 pixels wide (0.4 mm) to the width of ½ the height of the ROI (3 mm). The fractal dimensions in two directions were measured with rod-shaped structuring elements (6) using a "box" counting approach (10). The FSA data provided by the software are referenced to the 'vertical filter' (horizontal fractal dimension) and the 'horizontal filter' (vertical fractal dimension). So to avoid confusion, we herein describe the data in terms of the horizontal fractal dimension (tension) and vertical fractal dimension (compression) and not according to the 'filter'.

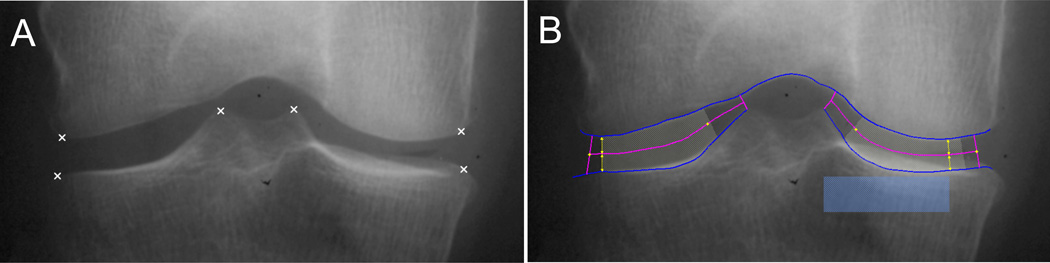

Figure 1. Optasia KneeAnalyzer computer assisted identification of regions of interest.

A) Joint segmentation was based on six manually selected initialization points (marked by x) at the lateral femur, medial femur, lateral tibia, medial tibia, lateral tibial spine, and medial tibial spine. B) Once the initialization points were selected, the software determined the joint space boundary profiles for both the lateral and medial compartments (medial compartment on right) and identified the region for fractal signature analysis in the medial subchondral bone (blue rectangular box).

Interrater reliability

A subset of six radiographs (3 OA, 3 non-OA) were analyzed by three analysts to test the impact of analyst on FSA. Two criteria were evaluated, the range and distribution of ‘filter’ elements and the fractal signature for both the horizontal and vertical fractal dimensions.

Statistical Analysis

The fractal signature (FS) data generated by the KneeAnalyzer application are 3-dimensional, where compression and tension fractal dimensions (FD) are measured over a range of radii for each knee X-ray, representing increasing lengths based on the pixel dimension. The FD measures are highly correlated along radius. We modeled the trends of compression and tension change over radius with second order (quadratic) multiple regression models using a non-centered polynomial, so that the multidimensional correlations between FD measures and radii were summarized by 2 polynomial “shape” parameters. Using the shape approach, precise alignment of radii across patients was not necessary, and the full use of the all the data could be made, thereby increasing the power to discern a potential difference between groups. Clinical covariates, including age, gender, BMI, knee pain, bone mineral content (BMC), left versus right knee, knee alignment and baseline knee OA severity (categorical joint space narrowing 0–3), were included in the same statistical model with an analysis of co-variances (ANCOVA) framework and repeated measures. Linear mixed models and generalized linear models were used to adjust for correlations between knees.

To determine if the fractal signature variation was associated with any clinical factors, we tested whether the shapes of the polynomial curves were different among different groups of individuals, e.g., progressors vs. non-progressors. This was to test the interaction terms between the shape parameters and the group indicators. We also investigated whether the FD variations were associated with other clinical factors such as age, gender, BMI, and other covariates, adjusting for the shape of curves considered in the model.

The full statistical model was: Yijk = u+a+g+BMI+BMC+KA+JSN+LR + rk + rk2 + gIDi + rk × gIDi + rk2 × gIDi + Pij + eijk; Where: Yijk is the fractal dimension readings calculated at i-th status (progressor vs. non-progressor), j-th individual (left vs. right) and k-th radius; u is the grand mean; a is age; g is gender; KA is Knee Alignment; JSN is the Joint Space Narrowing at Baseline; LR is the left or right knee indicator; r is radius – linear term; r2 radius – quadratic term; gIDi is the group ID (e.g., i=0 if non-progressor; =1 if progressor); r*gID and r2*gID are the interaction terms; Pij is the random effect associated with the jth subject in group i; eijk is the random error term, associated with the jth subject in group i at radius k. Since it is observed that in general the correlations among FD measures are larger for nearby radii than far-apart radii, an auto-regressive correlation model of order 1 (i.e., AR(1) in SAS/mixed/repeated measures) was used. More sophisticated statistical models were investigated as well, e.g., with various interaction terms between/among fixed effects, and multiple intra-subject random correlation patterns. Eventually this model was selected because of its parsimony and efficiency.

To determine if the shapes of the polynomial curves could be used to predict disease progression, we included the estimates of the shape parameters of the polynomial curves from both the compression and tension fractal dimensions, together with other covariates, in a generalized linear model (GLM/GEE) to predict disease progression status. GLM/GEE was used to adjust for correlations within an individual because there were two curves from most individuals (left and right knees), and the shape parameters estimated from those curves are likely to be correlated. The linear predictors from the GEE model were used to predict scores for every knee.

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were generated based on the prediction scores using 5-fold cross-validations as introduced by Efron (40). In the cross-validation, the data were divided randomly into 5 groups (or folds), 4 groups were used as training data for model building and the remaining 1 group was used for model validation. The false positive rate and false negative rate were calculated by averaging results from all 5 possible training-data/validation data combinations. A total of 300 cross-validations were performed and the averaged results were reported. Various statistical models containing different combinations of predicting variables were investigated. Data for the numbers needed to screen to predict one progressor were derived from the ROC curves for a range of false positive or type I error rates. The full GLM/GEE model was:

Yij = u + a + g + BMI + BMC + KA + JSN + LRj + HL + HQ + VL + VQ + Pi + eij; Where: Yij is the disease progression status, defined as at least one grade change in joint space narrowing or at least one grade change in osteophyte. It is recorded at i-th individual, j-th knee (left vs. right); a is age; g is gender; KA is Knee Alignment; JSN is the Joint Space Narrowing at Baseline; HL is the linear shape parameter estimated from horizontal filter data; VL is the linear shape parameter estimated from Vertical filter data; HQ is the quadratic shape parameter estimated from horizontal filter data; VQ is the quadratic shape parameter estimated from vertical filter data; P is the patient ID. This factor is treated as a random effect in the model; eij is the random error term, associated with ith subject and jth knee.

Results

Interrater reliability of fractal signatures

The impact of individual analysts on FSA was small and non-significant. In order to test the impact of the analysts, linear regression was used, plotting each analyst versus the mean filter element size or the mean fractal signature (horizontal and vertical) of the 6 knee radiographs. The fractal signatures (horizontal) gave intercepts and slopes (R2) for the three analysts of: 0.105 + 0.958 (0.93); −0.006 + 1.009 (0.86); and −0.99 + 1.032 (0.81). The fractal signatures (vertical) gave intercepts and slopes (R2) for the three analysts of: −0.05 + 1.022 (0.97); −0.13 + 0.94 (0.97); and −0.07 + 1.31 (0.97). The filter elements (to three decimal places) gave intercepts of 0 and slopes of 1.002, 1.002 and 0.995 respectively, with R2 >0.99.

Since the analyst does not manually ‘place’ the box for fractal analysis, we reviewed the ‘magnification factor’ from the Synaflexer™ calibration as well as the digital location of the box for the three analysts as a possible source for the small (and non-significant) variations. In all cases but one, the magnification factors were identical. In the exception there was a 2.8% variation between analyst 3 and the other two analysts. The median ‘box’ size for the group of patients was 157 (range 140 – 183) by 39 pixels (range 37 – 47). The differences in the box area were ≤ 9% for all analysts and all patients.

Image Analysis

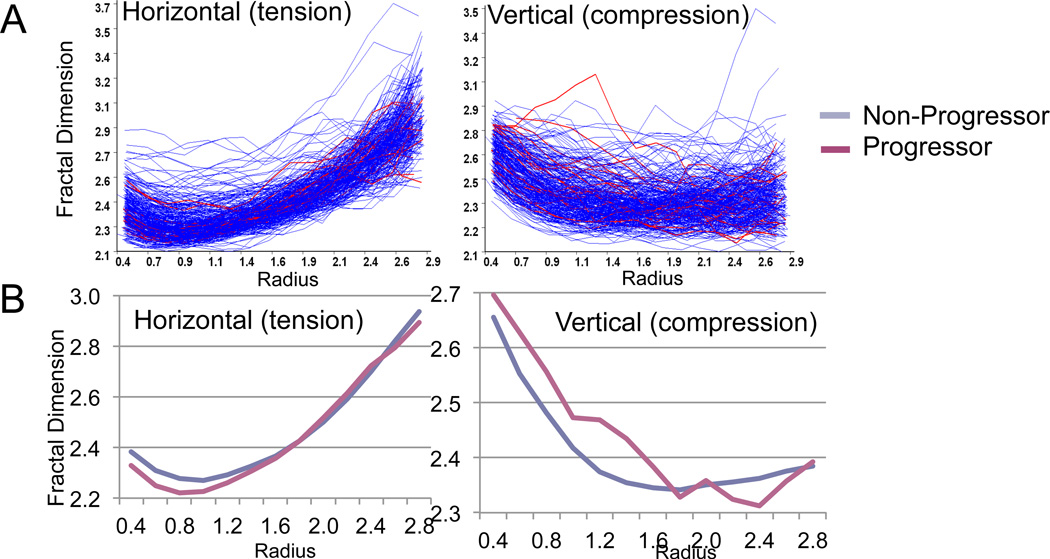

The complexity of the data posed an interesting bioinformatics challenge as demonstrated by the complexity of curves generated from all knees (Figure 2A). Upon analysis of the total fractal data without global shape analysis (Figure 2A), there was no discernible statistically significant association between fractal dimensions and progression status (for horizontal fractal dimension: p=0.42 for OST progression, and p=0.07 for JSN progression; for vertical fractal dimension: p=0.67 for OST progression, and p=0.15 for JSN progression). These results demonstrated the value, exemplified by analyses in past studies, of analyzing across groups within specific ranges of radii or trabecular size in order to draw any meaningful conclusions. In the past, this was typically done by subtraction of baseline from follow-up FSA data followed by group comparisons of data within specific ranges of trabecular widths. However, we chose a new method of analyses that modeled the overall shape of the curve of the fractal dimension versus radius. Two components of the shape curve were evident, a linear and a quadratic shape. This method avoided the problem of alignment of radii across individuals. Figure 2B shows the mean overall fractal signature shape curves of knee OA progressors and non-progressors. This method revealed decreased horizontal fractal dimensions (tension) and increased vertical fractal dimensions (compression) in progressors compared with non-progessors at particular regions of the curve.

Figure 2. FSA curves of progressors (red) and non-progressors (blue).

A) Knee radiographs were analyzed with the Optasia KneeAnalyzer, which generated a complex family of curves, each curve representing one individual’s fractal signature (fractal dimensions over a series of radii in mm). B) Curve fitting with quadratic and linear components showing lower mean fractal dimensions in knee OA progressors in the tension (horizontal on left) component, and higher mean fractal dimensions in knee OA progressors in the compression (vertical on right) component.

Correlations with FSA

The remaining analyses were conducted with linear and quadratic fitted fractal signature data. Bivariate associations with fractal signatures are shown in Table 1. The linear shape (radius) and the quadratic shape (radius2) terms were significantly associated with fractal dimensions. The interaction of the shape terms and OA progression was strongly associated with horizontal fractal dimension. Calcaneal bone mineral density (BMD) and bone mineral content (BMC) were both associated with horizontal fractal dimension; the association with BMC was strongest so it was retained in lieu of BMD for subsequent analyses. Significant associations with vertical fractal dimensions included both the linear, and quadratic shape terms, as well as gender, age and body mass index.

Table 1.

Bivariate associations with fractal dimensions in progressors and non-progressors (p values and parameter estimates)

| Horizontal Fractal Dimension (tension) |

Vertical Fractal Dimension (compression) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Progression based on OST |

Progression based on JSN |

Progression based on OST |

Progression based on JSN |

| P values (parameter estimates) | ||||

| radius |

< 0.0001 (−0.426) |

< 0.0001 (−0.386) |

< 0.0001 (0.018) |

< 0.0001 (−0.041) |

| radius2 |

< 0.0001 (0.202) |

< 0.0001 (0.193) |

< 0.0001 (0.139) |

< 0.0001 (0.134) |

| Left versus Right | 0.732 (0.011) |

0.904 (0.002) |

0.148 (0.038) |

0.108 (0.050) |

| radius*OA_progression |

0.002 (−0.094) |

0.034 (−0.106) |

0.969 (0.001) |

0.895 (0.006) |

| radius2*OA_progression |

< 0.0001 (0.036) |

0.023 (0.034) |

0.910 (−0.001) |

0.704 (0.005) |

| Left versus Right*OA_progression |

0.539 (−0.014) |

0.994 (0.0003) |

0.047 (−0.045) |

0.255 (−0.041) |

| Gender | 0.540 (0.009) |

0.5729 (0.008) |

< 0.0001 (−0.075) |

< 0.0001 (−0.078) |

| Age | 0.323 (−0.0005) |

0.3130 (−0.0006) |

0.008 (0.001) |

0.005 (0.001) |

| BMI | 0.983 (0.00002) |

0.916 (0.0001) |

0.001 (0.003) |

0.0003 (0.003) |

| BMC |

0.0187 (−0.005) |

0.018 (−0.005) |

0.758 (−0.0007) |

0.868 (−0.0004) |

| Knee Pain | 0.873 (−0.001) |

0.885 (−0.001) |

0.004 (0.023) |

0.004 (0.023) |

| Knee Alignment | 0.673 (0.001) |

0.769 (0.0004) |

0.292 (0.001) |

0.206 (0.002) |

| Baseline JSN status | 0.671 (−0.003) |

0.663 (−0.003) |

< 0.0001 (0.033) |

< 0.0001 (0.033) |

Approach: ANCOVA w/ Variance Component Model

FD (H,V) = 2nd polynomial fitting over “radius” |OA prog + Clinical covs + Design pars + random effects (Variance Components)

OST=progression based on osteophyte; JSN=progression based on joint space narrowing; BMI=body mass index; BMC=(calcaneal) bone mineral content

Prediction of OA progression based on global shape analysis of fractal signature curves

We next evaluated the prognostic capability of baseline fractal signatures to predict OA progression status at 3 years in models accounting for age, gender, BMI, BMC, knee pain, baseline knee status, and knee alignment, and adjusted using generalized estimating equations for the correlation between knees (Table 2). All fractal signature terms (horizontal and vertical, linear and quadratic) were acquired from the medial subchondral region. Fractal signatures of the medial subchondral bone from baseline x-rays were significantly correlated with 3-year OA progression based on JSN of the medial compartment. The baseline fractal signatures of the medial subchondral bone were not associated with OA progression based on OST, or with OA progression of the lateral knee compartment. In addition, age was independently predictive of medial and lateral JSN, while knee alignment was independently predictive of medial JSN. Accounting for these other factors, BMI was only independently predictive of lateral osteophyte progression.

Table 2.

Prediction modeling of OA progression defined by joint space narrowing (JSN) or osteophyte (OST)

| Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Any JSN | Medial JSN | Lateral JSN | Any OST | Medial OST | Lateral OST |

| P values from Type 3 GEE Models (parameter estimates) | ||||||

| Left vs. right | 0.397 (−0.307) |

0.635 (−0.251) |

0.317 (−0.530) |

0.817 (−0.053) |

0.673 (0.113) |

0.908 (−0.028) |

| Age | 0.384 (−0.020) |

0.025 (−0.088) |

0.032 (0.067) |

0.419 (0.012) |

0.978 (0.001) |

0.719 (0.005) |

| Gender | 0.654 (0.245) |

0.589 (−0.473) |

0.178 (1.019) |

0.605 (−0.174) |

0.554 (−0.239) |

0.934 (−0.030) |

| BMI | 0.352 (−0.042) |

0.067 (−0.115) |

0.503 (0.063) |

0.068 (0.043) |

0.241 (0.027) |

0.036 (0.053) |

| BMC | 0.387 (−0.062) |

0.245 (0.153) |

0.193 (−0.143) |

0.896 (0.007) |

0.988 (0.001) |

0.681 (−0.024) |

| Knee Pain | 0.629 (−0.133) |

0.110 (−0.669) |

0.874 (−0.055) |

0.108 (−0.301) |

0.744 (−0.064) |

0.286 (−0.203) |

| Knee Alignment | 0.119 (−0.113) |

0.016 (−0.252) |

0.610 (−0.057) |

0.096 (0.045) |

0.523 (0.018) |

0.063 (0.060) |

| Baseline JSN Status |

0.120 (−0.377) |

0.494 (−0.201) |

0.167 (−0.533) |

0.026 (0.372) |

0.005 (0.592) |

0.322 (0.171) |

| V_linear (compression) |

0.019 (−9.081) |

0.010 (18.225) |

0.631 (−1.701) |

0.515 (−1.275) |

0.129 (−3.235) |

0.586 (−1.140) |

| V_quad (compression) |

0.025 (−27.531) |

0.015 (58.807) |

0.760 (−3.057) |

0.508 (−3.941) |

0.180 (−8.942) |

0.535 (−3.896) |

| H_linear (tension) |

0.042 (4.585) |

0.012 (10.163) |

0.721 (1.105) |

0.893 (0.210) |

0.191 (2.380) |

0.626 (−0.752) |

| H quad (tension) |

0.062 (10.926) |

0.021 (24.153) |

0.551 (4.495) |

0.728 (−1.569) |

0.474 (3.895) |

0.371 (−4.133) |

SAS: proc genmod used GLM/GEE (Dist: Bin; L: logit)

OA prog = FS info (in polynomial parameters) + Clinical covs + Design pars + multiple correlation structures.

V=vertical; H=horizontal: linear and quad (quadratic) shape terms

OST=progression based on osteophyte; JSN=progression based on joint space narrowing; BMI=body mass index; BMC=(calcaneal) bone mineral content

Accuracy of fractal signatures for predicting OA progression

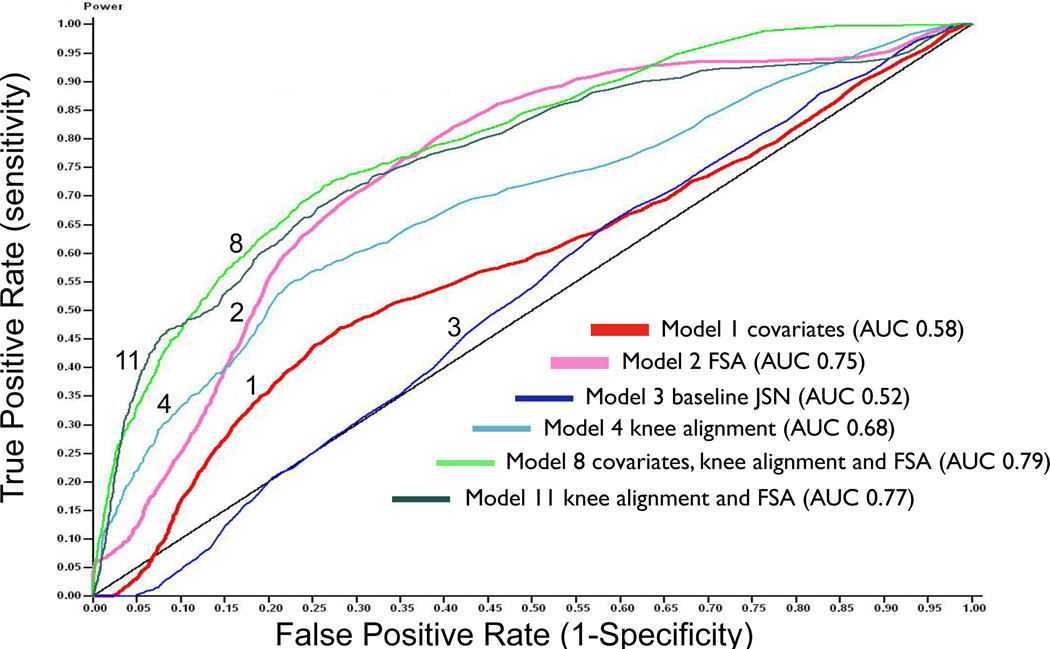

Receiver Operating Characteristic curves (ROC) were used to quantify the accuracy of predicting medial OA JSN progression by fractal signatures and other variables individually and in combination (Table 3). ROC curves were constructed to predict medial joint space narrowing cross-validating in 5 groups. The null model is expected to have an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.5; four random variables gave AUC 0.50. The traditional covariates (age, gender, BMI) fared no better than the random variables for predicting OA progression with AUC 0.52 (not shown). The addition of BMC and knee pain increased the predictive power only slightly (AUC 0.58). Baseline OA status (categorical joint space narrowing variable) alone was no better than the random variables (AUC 0.52) for predicting knee OA progression. FSA had a remarkably good predictive capability for OA progression yielding an AUC 0.75 with no improvement on addition of the covariates age, gender, BMI, BMC and knee pain (AUC 0.74). Among the other variables, only knee alignment was moderately predictive of medial JSN progression (AUC 0.68). The best model with the fewest variables (AUC 0.79) was not much better than FSA alone, and used all variables (age, gender, BMI, BMC, knee pain, knee alignment and FSA) but not baseline OA status. Six representative ROC curves are depicted in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Results of Receiver Operating Characteristic curves for assessing ability to predict OA progression and numbers needed to screen to predict one medial joint space narrowing progressor

| Model Covariates | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Age | Gender | BMI | BMC | Pain | Baseline OA JSN Severity |

Knee Alignment |

FSA | Random | Area Under Curve (AUC) |

AUC Range (95% CIs) |

| 1 | X | X | X | X | X | 0.58 | 0.46–0.69 | ||||

| 2 | X | 0.75 | 0.65–0.84 | ||||||||

| 3 | X | 0.52 | 0.44–0.59 | ||||||||

| 4 | X | 0.68 | 0.57–0.81 | ||||||||

| 5 | X | X | 0.67 | 0.55–0.80 | |||||||

| 6 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.74 | 0.65–0.84 | |||

| 7 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.74 | 0.65–0.84 | ||

| 8 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.79 | 0.72–0.88 | ||

| 9 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | 0.79 | 0.71–0.88 | |

| 10 | X | X | 0.74 | 0.64–0.83 | |||||||

| 11 | X | X | 0.77 | 0.66–0.88 | |||||||

| 12 | X | X | X | 0.76 | 0.65–0.88 | ||||||

| 13 | X | 0.50 | 0.41–0.57 | ||||||||

| Numbers Needed to Screen to Identify One Progressor | ||||||||||||||

|

False Positive Rate |

0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

|

Using Covariates |

∞ | 398.8 | 74.75 | 41.24 | 23.92 | 17.33 | 11.61 | 8.99 | 6.72 | 5.72 | 2.08 | 1.68 | 1.36 | 1.08 |

| Using FSA | 15.00 | 12.50 | 10.91 | 9.23 | 7.55 | 5.85 | 5.26 | 4.71 | 4.17 | 3.85 | 1.42 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 1.05 |

Covariates = age, gender, BMI, knee pain, and bone mineral content

FSA = fractal signature analysis

Figure 3. Representative Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves depicting the strength of the predictive models for medial OA joint space narrowing.

The black diagonal line represents the result of using random variables to predict medial knee OA joint space narrowing progression. Model 1 (thick red line) uses covariates: age, gender, BMI, knee pain and bone mineral content (BMC); Model 2 (thick pink line) uses FSA alone; Model 3 (thin dark blue line) uses baseline medial joint space narrowing alone; Model 4 (thin light blue line) uses knee alignment alone; Model 8 (thin green line) with highest overall area under the curve uses covariates (age, gender, BMI, knee pain, and BMC), knee alignment, and FSA; Model 11 (thin dark line) uses knee alignment and FSA (FSA=bone texture by fractal signature analysis).

Utility

To gain an appreciation of how FSA might benefit clinical trial design, we extracted data from the ROCs for this cohort to estimate the number needed to screen to identify one medial compartment progressor by this method. We compared the predictive ability of the traditional covariates (age, gender, BMI, knee pain) and bone mineral content to that of medial compartment FSA. As demonstrated for a variety of false positive rates, fewer individuals need to be screened in order to predict one progressor using FSA compared with the other covariates. At a type I error or false positive rate of 5%, 8 individuals would need to be screened by FSA versus 24 using the other covariates, amounting to 1:3 ratio to identify one medial knee OA progressor comparing the two methods (Table 3).

Discussion

Although trabecular structure is not truly fractal in nature, trabeculae possess fractal-like properties at the resolution of the plain radiograph (10). For this reason, fractal analysis is a valuable analytic tool for characterizing the complicated histomorphometry of bone. However, one of the major challenges posed by FSA studies is how to analyze the complex fractal signature data. The most recent studies of FSA and OA generally relied on subtraction of the mean fractal signature of an OA or treatment group from that of a non-OA control or reference group (21, 23, 24). We found it was necessary to develop a method of analyzing these complex data to have a means of comparing the baseline data in cross-section to distinguish progressors from non-progressors. The strategy used here was to focus on a global approach, curve fitting with a second order polynomial regression. By using this approach, we found that OA progression defined by JSN was significantly associated with shape of the fractal signature curves. In brief, we found that baseline higher fractal signatures of vertical trabeculae and baseline lower fractal signature of horizontal trabeculae distinguished knee OA progressors from OA non-progressors. Bone texture by FSA of the inner ¾ of the medial tibial compartment demonstrated 75% predictive capacity by ROC curve for predicting individuals with significant medial joint space narrowing but not osteophyte. These results are applicable to clinical trial design and it is hoped, will afford a new means of enriching a trial for joint space narrowing progressors.

Age has been associated with increased number (increased FSA) of fine vertical and horizontal trabeculae independent of disease state (14); in these past studies the size of trabeculae affected by age did not overlap the range of trabecular sizes altered by OA (16). Using the global shape analysis approach, we found only small effects of age on the vertical FSA. Previously, no correlation was found between BMI and FSA (17). Using the global shape analysis approach, we found a small but significant effect of BMI on vertical FSA.

Although no previous studies evaluated subchondral trabecular texture as a predictor of OA progression, there have been two studies showing significant longitudinal change in trabecular texture coincident with OA progression using a subtractive approach (follow-up minus baseline fractal signatures) (19, 25). The data from the subarticular region in particular, and the direction of these longitudinal fractal signature changes with progression were consistent with the differences we have found between progressors and non-progressors differentiated at baseline. A further study showed a significant decrease in the horizontal fractal dimension within four years of an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture (27), suggesting that the bone changes following ACL rupture occur early and replicate those of knee OA progression.

Previous studies using other approaches have established that changes in periarticular bone occur very early in the development of OA, supporting the concept that skeletal adaptations antedate detectable alterations in the structural integrity of the articular cartilage (41). It has been shown previously that FSA detects changes in periarticular bone that are not discernible by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (9). Our data support the contention that changes in peri-articular bone are sensitive indicators of the disease process in human OA and provide a prognostic factor with high predictive capability for subsequent cartilage loss. One reason for this, posed by Goldring, is the marked differential capacity of cartilage and bone to adapt to mechanical loads and damage (41). Cortical and trabecular bone rapidly alter skeletal architecture and shape in response to load via cell-mediated modeling and remodeling. Chondrocytes also modulate their functional state in response to loading, however, the capacity of these cells to repair and modify their surrounding extracellular matrix is relatively limited in comparison with skeletal tissues. This differential adaptive capacity likely underlies the more rapid appearance of detectable bone skeletal changes in OA, especially after injuries that acutely alter joint mechanics An increase in fractal dimensions, as seen here in the vertical (compression) component in knee OA progressors, has been equated with increased complexity of the image due to increased trabecular number secondary to thinning and fenestration of coarser trabeculae, in brief, a bone resorptive process. Decreased fractal dimensions, as seen here for the horizontal (tension) component in knee OA progressors, has been equated with decreased complexity of the image due to apparent decreased trabecular number secondary to trabecular coarsening manifested as horizontal striations on the radiograph (24). It has been speculated that the changes in the horizontal component result from a thickened cortical plate and retention of the horizontal trabeculae associated with enhanced absorption of load-bearing stress, resulting in reduced load transmission to the underlying trabecular bone, termed stress shielding, and the development of progressive osteoporotic change (22).

Curiously, the shapes of the vertical and horizontal FSA curves for the medial subchondral region of the knee appeared to differ between our work and that of Buckland-Wright and colleagues; they reported an initial increase then steady decrease in the fractal dimension in both vertical and horizontal directions with increasing radius (17), while we have found a decrease in fractal dimension in the vertical trabeculae and an increase in fractal dimension in the horizontal trabeculae with increasing radius. In part, this may be explained by the fact that we did not use digitized macroradiographs as was often done in previous work, so we did not detect the smallest trabeculae. The dimensions in the study by Buckland-Wright (0.06mm – 1.14mm) were also different from those in our analysis (0.4mm - 3mm). As such, our curves represent an extension encompassing larger radii compared with those published in previous report and are in fact consistent with those found in the report by Buckland-Wright and colleagues (17, 27). Additionally, our ROIs differed. For the Buckland-Wright study in which the FSA curves are reported, they used an ROI spanning the outer ¾ of the medial tibial plateau rather than the inner ¾ of their later work (9) and our work. Nevertheless, the characteristic differences between fractal signature patterns of progressors and non-progressors were comparable to the changes seen longitudinally in Buckland-Wright's work between fast and slow progressors (19).

OA progression can be influenced by both systemic and local factors (reviewed in (42). Among the most potent risk factors for structural progression yet described are limb malalignment, both static and dynamic, and obesity, whose effect has been shown to be mediated by malalignment (43). Although knee alignment did increase the predictive capability of OA progression over traditional covariates including BMI, it added only modestly to FSA. A number of features on magnetic resonance images (MRI) have been associated with knee OA progression including meniscal factors (1, 44), and bone marrow lesions (45, 46), as well as joint effusion, synovial pathology, cartilage lesions, and osteophytes (44). No head to head comparisons have been performed of soft tissue (by MRI) versus bone texture (FSA of radiograph) features so the relative strength of these predictors is not precisely known at this time. However, Hunter showed that the strongest MRI predictor in their study, meniscal subluxation, contributed 7% predictive power to a model consisting of age, sex and BMI (1), whereas we found that FSA contributed 75% on its own and 17% predictive power to a model consisting of age, BMI, sex, knee pain, and bone mineral content. Furthermore, our results for FSA were derived by cross-validation which is a reliable and conservative approach to estimating predictive power. We are not aware of any other individual predictive factor as good as FSA in the published literature currently. Moreover, both FSA and knee alignment can be obtained from a standard radiograph and could provide the most cost-effective means of maximizing identification of progressors.

FSA may be a valuable adjunct in OA clinical trials for several reasons. FSA can provide a quantitative indication of the effects of a drug on bone remodeling especially for drugs that have a direct effect on bone, such as the bisphosphonates (25), calcitonin (47), diacerhein (48), and cathepsins (49), to name a few. Second, the ability of FSA to reflect cartilage loss (19) and to predict risk for cartilage loss, as shown here, makes it a potential outcome for drugs whose mechanism of action may be targeted to cartilage breakdown, not just bone remodeling. Third, FSA is relatively robust to differences in x-ray acquisition and quality, and patient positioning, and could be readily obtained from a standard knee radiograph, thus providing a cost-effective outcome that could be effectively instituted in a multi-center trial.

A limitation of our study was that we did not use macroradiographs, however, a past study showed that radiographic method had no significant effect upon reproducibility of vertical and horizontal FSA but that macroradiographs only showed differences between OA and control groups across a wider range of trabecular widths than standard radiographs (23). As with all past studies, we performed FSA on digitized images. We compared reliability and results of FSA from digitized and digital image formats and noted the loss of data from a few of the smallest radii only (data not shown), an effect that is likely due to subtle smoothing of detail in the secondary digitization. It will be useful to determine in a future study whether the use of digitally acquired images may increase sensitivity for changes in very small radii and may further enhance the predictive capability of the method. A strength of the study was that we analyzed both knees with appropriate controlling for correlation between knees, thereby increasing study power. We also controlled for baseline status and derived conservative estimates in the predictive models due to the cross-validation approach that was used. Inclusion of all types of knee OA from our cohort revealed that medial tibial plateau fractal signature specifically predicted medial JSN. This compartmental specificity of FSA for ipsilateral JSN provides additional evidence for the face validity of this measure. It remains to be seen whether lateral FSA will have similar predictive capability for lateral JSN (work in progress). The predictive capability of lateral FSA for lateral OA progression has not been assessed previously as all previous studies were confined to individuals with isolated medial compartment or medial compartment dominant disease. Finally, it was also suggested from this work that the traditional covariates and baseline knee status are poor means of enriching a clinical trial for joint space narrowing progressors.

A recent review suggested three reasons to obtain a radiograph for research or clinical trial purposes (50): 1) to establish the diagnosis or the degree of severity of OA; 2) to monitor disease activity, progression and possible therapeutic responses; and 3) to look for complications of the disorder or therapy. With the advent of these promising FSA data we add a fourth reason to obtain a radiograph, namely to evaluate risk for knee OA progression. This approach could be used to enrich an OA treatment trial with knee OA progressors to help minimize trial cost and drug exposure and increase the study power to show an effect.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Norine Hall and Samantha Womack, E Boudreau, who have contributed to image digitization and semi-automated analysis and to Gary McDaniel, PAC, study coordinator of the POP study. We also wish to express sincerest thanks to Alan Brett and Optasia for providing the Optasia KneeAnalyzer for research use.

Supported by a generous gift from David H. Murdock; Grant Number 1UL1 RR024128–01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research; NIH/NIAMS grant RO1 AR48769, and by the National Center for Research Resources NIH MO1-RR-30, supporting the Duke General Clinical Research Unit where this study was conducted. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH, and NIH/NIAMS

References

- 1.Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Tu X, Lavalley M, Niu JB, Amin S, et al. Change in joint space width: hyaline articular cartilage loss or alteration in meniscus? Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2488–2495. doi: 10.1002/art.22016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA, Katz BP, Lane KA, Buckwalter KA, Yocum DE, et al. Effects of doxycycline on progression of osteoarthritis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2015–2025. doi: 10.1002/art.21122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellio Le Graverand MP, Buck RJ, Wyman BT, Vignon E, Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, et al. Change in regional cartilage morphology and joint space width in osteoarthritis participants versus healthy controls - a multicenter study using 3.0 Tesla MRI and Lyon Schuss radiography. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohmander LS, Felson D. Can we identify a 'high risk' patient profile to determine who will experience rapid progression of osteoarthritis? Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(Suppl A):S49–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldring SR. The role of bone in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34(3):561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch JA, Hawkes DJ, Buckland-Wright JC. A robust and accurate method for calculating the fractal signature of texture in macroradiographs of osteoarthritic knees. Med Inform (Lond) 1991;16(2):241–251. doi: 10.3109/14639239109012130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch JA, Hawkes DJ, Buckland-Wright JC. Analysis of texture in macroradiographs of osteoarthritic knees using the fractal signature. Phys Med Biol. 1991;36(6):709–722. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/36/6/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffith JF, Genant HK. Bone mass and architecture determination: state of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22(5):737–764. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Messent EA, Buckland-Wright JC, Blake GM. Fractal analysis of trabecular bone in knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a more sensitive marker of disease status than bone mineral density (BMD) Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;76(6):419–425. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung HW, Chu CC, Underweiser M, Wehrli FW. On the fractal nature of trabecular structure. Med Phys. 1994;21(10):1535–1540. doi: 10.1118/1.597263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majumdar S, Weinstein RS, Prasad RR. Application of fractal geometry techniques to the study of trabecular bone. Med Phys. 1993;20(6):1611–1619. doi: 10.1118/1.596948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein RS, Majumdar S. Fractal geometry and vertebral compression fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9(11):1797–1802. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650091117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckland-Wright JC, Lynch JA, Rymer J, Fogelman I. Fractal signature analysis of macroradiographs measures trabecular organization in lumbar vertebrae of postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994;54(2):106–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00296060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckland-Wright JC, Lynch JA, Bird C. Microfocal techniques in quantitative radiography: measurement of cancellous bone organization. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35(Suppl 3):18–22. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.suppl_3.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma S, Rogers J, Watt I, Buckland-Wright C. Bone mineral density and fractal signature analysis in hip osteoarthriis - a study of a post-mortem and a postoperative population. Clin Radiology. 1997:52–872. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papaloucas CD, Ward RJ, Tonkin CJ, Buckland-Wright C. Cancellous bone changes in hip osteoarthritis: a short-term longitudinal study using fractal signature analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(11):998–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckland-Wright JC, Lynch JA, Macfarlane DG. Fractal signature analysis measures cancellous bone organisation in macroradiographs of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(10):749–755. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.10.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messent EA, Buckland-Wright C. Tibial cancellous bone changs in early knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;(S9):1084. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckland-Wright C, Messent E, Papaloucas C, GA C, Beary J, Meyer K. Tibial cancellous bone changes in OA knee patients grouped into those with slow or detectable joint space narrowing (JSN) Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(S9):S145. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papaloucas CD, Earnshaw P, Tonkin C, Buckland-Wright JC. Quantitative radiographic assessment of cancellous bone changes in the proximal tibia after total knee arthroplasty: a 3-year follow-up study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;74(5):429–436. doi: 10.1007/s00223-003-0109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messent EA, Ward RJ, Tonkin CJ, Buckland-Wright C. Tibial cancellous bone changes in patients with knee osteoarthritis. A short-term longitudinal study using Fractal Signature Analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(6):463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messent EA, Ward RJ, Tonkin CJ, Buckland-Wright C. Cancellous bone differences between knees with early, definite and advanced joint space loss; a comparative quantitative macroradiographic study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messent EA, Ward RJ, Tonkin CJ, Buckland-Wright C. Differences in trabecular structure between knees with and without osteoarthritis quantified by macro and standard radiography, respectively. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(12):1302–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Messent EA, Ward RJ, Tonkin CJ, Buckland-Wright C. Osteophytes, juxta-articular radiolucencies and cancellous bone changes in the proximal tibia of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.06.020. Epub 2006 Aug 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckland-Wright JC, Messent EA, Bingham CO, 3rd, Ward RJ, Tonkin C. A 2 yr longitudinal radiographic study examining the effect of a bisphosphonate (risedronate) upon subchondral bone loss in osteoarthritic knee patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(2):257–264. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel213. Epub 2006 Jul 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podsiadlo P, Dahl L, Englund M, Lohmander LS, Stachowiak GW. Differences in trabecular bone texture between knees with and without radiographic osteoarthritis detected by fractal methods. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(3):323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckland-Wright JC, Lynch JA, Dave B. Early radiographic features in patients with anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(8):641–646. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.8.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldie L, Foster M, Buckland-Wright C. Quantitative radiography of cancellous bone changes in the distal radius of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;(Suppl 9):S231. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Disini L, Foster M, Milligan PJ, Buckland-Wright JC. Cancellous bone changes in the radius of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional quantitative macroradiographic study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(9):1150–1157. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karvonen RL, Miller PR, Nelson DA, Granda JL, Fernandez-Madrid F. Periarticular osteoporosis in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(11):2187–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennell KL, Creaby MW, Wrigley TV, Hunter DJ. Tibial subchondral trabecular volumetric bone density in medial knee joint osteoarthritis using peripheral quantitative computed tomography technology. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(9):2776–2785. doi: 10.1002/art.23795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bettica P, Cline G, Hart DJ, Meyer J, Spector TD. Evidence for increased bone resorption in patients with progressive knee osteoarthritis: longitudinal results from the Chingford study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(12):3178–3184. doi: 10.1002/art.10630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li B, Aspden RM. Composition and mechanical properties of cancellous bone from the femoral head of patients with osteoporosis or osteoarthritis. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12(4):641–651. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buckland-Wright C. Subchondral bone changes in hand and knee osteoarthritis detected by radiography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(Suppl A):S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MA, Ettinger WH, Neuhaus JM. Obesity and osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1990;20(3 Suppl 1):34–41. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(90)90045-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterfy C, Li J, Saim S, Duryea J, Lynch J, Miaux Y, et al. Comparison of fixed-flexion positioning with fluoroscopic semi-flexed positioning for quantifying radiographic joint-space width in the knee: test-retest reproducibility. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:128–132. doi: 10.1007/s00256-002-0603-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altman RD, Hochberg M, Murphy WA, Jr., Wolfe F, Lequesne M. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995;3(Suppl A):3–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kraus VB, Vail TP, Worrell T, McDaniel G. A comparative assessment of alignment angle of the knee by radiographic and physical examination methods. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(6):1730–1735. doi: 10.1002/art.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the Bootstrap. London: Chapman and Hill; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldring SR. Role of bone in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter DJ. Risk stratification for knee osteoarthritis progression: a narrative review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Felson DT, Goggins J, Niu J, Zhang Y, Hunter DJ. The effect of body weight on progression of knee osteoarthritis is dependent on alignment. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;50(12):3904–3909. doi: 10.1002/art.20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madan-Sharma R, Kloppenburg M, Kornaat PR, Botha-Scheepers SA, Le Graverand MP, Bloem JL, et al. Do MRI features at baseline predict radiographic joint space narrowing in the medial compartment of the osteoarthritic knee 2 years later? Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(9):805–811. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0508-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felson DT, McLaughlin S, Goggins J, LaValley MP, Gale ME, Totterman S, et al. Bone marrow edema and its relation to progression of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(5 Pt 1):330–336. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_1-200309020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wluka AE, Hanna F, Davies-Tuck M, Wang Y, Bell RJ, Davis SR, et al. Bone marrow lesions predict increase in knee cartilage defects and loss of cartilage volume in middle-aged women without knee pain over 2 years. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):850–855. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karsdal MA, Sondergaard BC, Arnold M, Christiansen C. Calcitonin affects both bone and cartilage: a dual action treatment for osteoarthritis? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1117:181–195. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boileau C, Tat SK, Pelletier JP, Cheng S, Martel-Pelletier J. Diacerein inhibits the synthesis of resorptive enzymes and reduces osteoclastic differentiation/survival in osteoarthritic subchondral bone: a possible mechanism for a protective effect against subchondral bone remodelling. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(3):R71. doi: 10.1186/ar2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vasiljeva O, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Turk D, Turk V, Turk B. Emerging roles of cysteine cathepsins in disease and their potential as drug targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(4):387–403. doi: 10.2174/138161207780162962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buckland-Wright C. Which radiographic techniques should we use for research and clinical practice? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20(1):39–55. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]