Abstract

The pancreas consists of three main cell lineages (endocrine, exocrine, and duct) that develop from common primitive foregut precursors. The transcriptional network responsible for endocrine cell development has been studied extensively, but much less is known about the transcription factors that maintain the exocrine and duct cell lineages. One transcription factor that may be important to exocrine cell function is Mist1, a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factor that is expressed in acinar cells. In order to perform a molecular characterization of this protein, we employed coimmunoprecipitation and bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays, coupled with electrophoretic mobility shift assay studies, to show that Mist1 exists in vivo as a homodimer complex. Analysis of transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative Mist1 transgene (Mist1mutant basic [Mist1MB]) revealed the cell autonomous effect of inhibiting endogenous Mist1. Mist1MB cells become disorganized, exhibit a severe depletion of intercellular gap junctions, and express high levels of the glycoprotein clusterin, which has been shown to demarcate immature acinar cells. Inhibition of Mist1 transcriptional activity also leads to activation of duct-specific genes, such as cytokeratin 19 and cytokeratin 20, suggesting that alterations in the bHLH network produce a direct acinar-to-ductal phenotypic switch in mature cells. We propose that Mist1 is a key transcriptional regulator of exocrine pancreatic cells and that in the absence of functional Mist1, acinar cells do not maintain their normal identity.

The molecular and cellular processes that control the development and maintenance of the adult pancreas encompass aspects of inductive cellular interactions, signaling pathways, and transcriptional regulatory networks (8, 21, 37, 43). Each of these events operates in concert to generate the distinct endocrine and exocrine cell compartments that are associated with the mature organ. These cell types include the endocrine islet cells which express insulin (β cells), glucagon (α cells), somatostatin (δ cells), and pancreatic polypeptide (PP cells), the exocrine acinar cells which express a variety of digestive hydrolases, and the duct cells which produce an elaborate tubular network to transport acinar cell products to the digestive tract (8, 21).

The ability of the primitive foregut to generate these complex cell lineages relies on the expression and activity of many transcription factors, including Forkhead box proteins (Foxa1 and Foxa2), LIM homeodomain proteins (Isl1 and Lmx1.1), and homeobox transcription factors (PDX1, Pbx1, and HB9) (7, 8, 21, 35, 43). Gene inactivation studies have revealed that many of these factors are critical to the initial specification of the pancreatic buds and the generation of the endocrine and exocrine cell lineages (1, 13, 18, 26, 30).

An additional transcription factor family that is critical to pancreas development is the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein family. The bHLH proteins are grouped into two distinct classes based primarily on expression patterns and DNA binding characteristics (25, 27). Class A bHLH proteins are expressed in most cell types, while class B bHLH proteins exhibit a highly restricted, tissue-specific expression pattern. The functional bHLH unit is a dimer that normally is produced by one member of the class A factors, such as E12, E47, HEB, and ITF-1, and one member of the class B factors (27). Binding of bHLH heterodimers to target genes leads to transcriptional activation and the subsequent lineage specificity and differentiation of pancreatic stem cells (10, 17, 23, 27, 29).

To date, four class B bHLH factors (neurogenin3, NeuroD1, PTF1a, and Mist1) have been identified as essential to pancreas development and/or maintenance of the differentiated state. Neurogenin3 is critical to endocrine cell lineage progression, while NeuroD1 is essential for the expansion of the endocrine α, β, and δ cells (10, 29, 36). Similarly, PTF1a (also known as PTF1-p48) is involved in specifying the exocrine cell lineage, since mice lacking Ptf1a fail to develop an exocrine pancreas (23). Recent genetic studies by Kawaguchi et al. (19) have shown that Ptf1a expression is also associated with pancreatic progenitor cells that are capable of generating all three cell lineages (endocrine, exocrine, and duct), providing intriguing new evidence that Ptf1a may have additional roles in regulating endocrine and duct cell lineage progression.

Another bHLH factor that is expressed in the exocrine pancreas is Mist1 (31, 32). Mist1 gene expression occurs early in pancreatic development (embryonic day 10.5 [E10.5]) and becomes restricted to the exocrine acinar cells (31, 32). The exocrine pancreas lineage is specified properly in Mist1 null mice, but the development of individual cells and the establishment of normal cellular polarity associated with acini are disrupted (32, 34). Although the expression pattern and initial characterization of Mist1 null mice have been reported, very little is known regarding the molecular properties associated with this factor. In addition, the complex phenotype associated with the Mist1 null animals has made it difficult to determine which alterations are directly due to the absence of Mist1 and which changes are the result of long-term physiological consequences ascribed to a Mist1 null pancreas.

In an effort to perform a molecular dissection of Mist1, we employed coimmunoprecipitation and bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays, coupled with electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) studies, to show that Mist1 exists in vivo as a homodimer complex. Analysis of transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative Mist1 transgene (Mist1mutant basic [Mist1MB]) revealed the cell autonomous consequence of inhibiting endogenous Mist1 activity and confirmed that Mist1MB cells develop a highly disorganized cellular structure, exhibit a severe depletion of intercellular gap junctions, and express high levels of the glycoprotein clusterin, which has been shown to demarcate immature acinar cells (28). Inhibition of Mist1 transcriptional activity also leads to activation of the duct-specific genes cytokeratin 19 (CK19) and cytokeratin 20 (CK20), suggesting a direct acinar-to-ductal conversion. These results demonstrate that Mist1 is critical to the terminal differentiation of the exocrine pancreas and that in the absence of functional Mist1 protein, acinar cells do not maintain a fully mature state. We conclude that Mist1MB mice represent a novel model system that allows analysis of the cell autonomous nature of the bHLH transcriptional regulatory networks that are involved in maintaining the exocrine pancreas lineage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene constructs, reporter gene assays, and Mist1MB mice.

The Mist1MB and Mist1mutant helix (Mist1MH) gene constructs were produced by standard site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit from Stratagene. Mist1MB contains the basic domain amino acid substitutions RER→GGG (amino acids 80 to 82) while Mist1MH contains a Q→P (amino acid 93) substitution within helix 1. A Myc epitope tag was added to the carboxyl end of the Mist1, Mist1MB, and Mist1MH proteins using the pcDNA3-Myc/His cloning plasmid (Invitrogen). The elastasepr-Mist1MB gene construct was generated using a fragment of the rat elastase 1 promoter (elastasepr) from positions −500 to +8 (15, 40) driving expression of a Myc-tagged Mist1MB protein. This construct was used to generate elastasepr-Mist1MB mice through standard pronuclear injection protocols. The Cx32pr-Luc reporter gene containing positions −680 to +20 of the mouse connexin32 promoter (Cx32pr) has been reported previously (34).

Cells from the pancreatic exocrine cell line AR42J were propagated in growth medium consisting of 40% F12K, 25% high-glucose Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (hgDMEM), 25% F12, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Cells (1.6 × 106) were transfected by electroporation using 10 μg of reporter (Cx32pr-Luc), 5 μg of the appropriate transcription factor expression plasmid (pcDNA3, pcDNA3-Mist1, pcDNA3-Mist1MB, or pcDNA3-Mist1MH) and 5 μg of pRL-Null Renilla luciferase control vector per experimental group. Where indicated, cells were cotransfected with Mist1MB or Mist1MH expression plasmids (2, 5, or 10 μg) and 5 μg of the Mist1 expression plasmid. In all cases, DNA concentrations were kept constant using pcDNA3. Cells were harvested 48 h posttransfection by scraping the cells into Promega passive lysis buffer. Luminescence values were determined using the Promega dual luciferase reporter assay system. At least three independent transfections were performed for all gene constructs and experimental groups.

HEK-293 cells were maintained in medium containing hgDMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% penicillin or streptomycin. All transfections were performed using 106 cells per 100-mm-diameter dish and a standard calcium phosphate precipitation protocol. For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, cells were cotransfected with 5 μg of individual pcDNA3-Myc-tagged Mist1 DNA constructs and 5 μg of an untagged pcDNA3-Mist1 expression plasmid. For EMSAs, cells were transfected with 2 μg of pcDNA3-Mist1 and 4 μg of a competitor (Mist1MB or Mist1MH) expression plasmid.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation.

Mist1 and Mist1MH coding regions were amplified by PCR and cloned in frame into the pBiFC-YN and pBiFC-YC plasmids to yield pBiFC-Mist1-YN, pBiFC-Mist1-YC, pBiFC-Mist1MH-YN and pBiFC-Mist1MH-YC. The pBiFC-YN and -YC plasmids contain the N and Y terminus of the yellow fluorescence protein (YFP), respectively (16). For analysis of fluorescence complementation, specific YN and YC plasmids (5 μg/100-mm-diameter dish) were transfected into HEK-293 cells singly or in multiple pairwise combinations. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were switched to 30°C for 2 h and then examined for nuclear fluorescence using standard fluorescence microscopy. pBiFC-Jun-YN and pBiFC-Fos-YC plasmids were used as positive controls (16).

EMSAs.

E-box oligonucleotide probes were generated by standard procedures using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. EMSAs were conducted as described previously (22). Nuclear extracts were prepared by lysing cells in lysis buffer containing 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) for 30 min. The nuclear fraction was collected and resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, 0.52 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 25% glycerol, 0.2% NP-40). Four micrograms of nuclear extract was used for each 30-μl reaction mixture in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM DTT, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 4 μg of bovine serum albumin, and 2 μg of poly(dI-dC). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 15 min, the 32P-labeled E-box DNA probe was added to the mixture, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min. In some experiments, preimmune or anti-Mist1 serum was added to the reaction mixture for EMSA supershift assays. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and visualized by autoradiography.

Coimmunoprecipitation assays.

Whole-cell lysates from HEK-293 cells were prepared by lysing cells with 400 μl of lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 10% glycerol. The lysates were then incubated with 5 μl of anti-Myc (9E10) at 4°C. After 1 h, 15 μl of protein A (Amersham) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h. Samples were washed four times with lysis buffer and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using the Mist1 antibody.

RNA expression analysis.

Total RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed using the Superscript II reverse transcription system (Gibco BRL). cDNA reactions were amplified using Taq polymerase and gene-specific primers for Mist1 (5′-GCGCGTACGGCCTCGAAT-3′ and 5′-CAAGCCCTAGAGAAGATG-3′), CK20 (5′-GGCAATGCAGAACCTGAACG-3′ and 5′-GAGCCTTGACGTCCTCTAGG-3′), and β-actin (5′-ATTGTTACCAACTGGGACG-3′ and 5′-TCTCCTGCTCGAAGTCTAG). Target sequences were amplified within linear ranges using the following conditions: 95°C for 40 s, 55°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 55 s. All primer pairs amplified regions crossing intron borders.

Immunohistochemistry.

Frozen and paraffin-embedded pancreatic sections were processed for immunohistochemistry by standard procedures. Briefly, tissues were removed, frozen in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek) without fixation, and cut into 5-μm-thick sections at −20°C using a Zeiss cryostat. Tissue sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then blocked for 1 h with the Mouse on Mouse (MOM) reagent (Vector). For paraffin immunohistochemistry, pancreatic tissue was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm-thick sections. Sections were deparaffined and rehydrated, and then antigens were retrieved using the 2100-Retriever and the supplied AG buffer (PickCell Laboratories). Samples were washed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked using the MOM blocking reagent. Primary antibodies were added to frozen or paraffin-embedded sections for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies included rabbit Mist1 (diluted 1:100), rabbit c-Myc (diluted 1:200; Santa Cruz), mouse Myc 9E10 (diluted 1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), mouse connexin32 (diluted 1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) (diluted 1:100; Chemicon), rabbit connexin32 (diluted 1:200; Zymed Laboratories), goat clusterin (diluted 1:100; Santa Cruz), mouse CK20 (diluted 1:100; DAKO), and mouse CK19 (TROMA 3; diluted 1:500; gift of Rolf Kemler). After the primary antibody was added, sections were incubated with biotinylated or Texas red-conjugated secondary antibodies (diluted 1:250; Vector) for 10 min at room temperature followed by incubation with Oregon green-conjugated tertiary antibodies (diluted 1:300; Molecular Probes) and 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma) for 5 min. Coverslips were mounted with Fluorosave reagent (Calbiochem) and examined using an Olympus fluorescence microscope. Images were captured with a QImager MicroImager II digital camera and Empix Northern Eclipse software.

Electron microscopy and immunogold labeling.

Pancreas fragments from wild-type and Mist1MB mice were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde-0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS and then gradually dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in LRWhite resin. Immunogold labeling was performed on ultrathin sections using anti-rabbit c-Myc, followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to colloidal gold (18-nm diameter). Electron micrographs were obtained using a Philips transmission electron microscope.

Protein immunoblot assays.

Tissue protein extraction, protein electrophoresis, and immunoblotting were performed as described previously (31, 32). For immunoblot analysis, 50-μg samples of whole-cell protein extracts were electrophoresed on acrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and incubated with primary antibodies against Mist1, Myc, CK20, Akt, and β-actin. After the immunoblots were incubated with a secondary antibody, they were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Pierce) per the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Mutations in the Mist1 DNA binding domain create a functional dominant-negative protein.

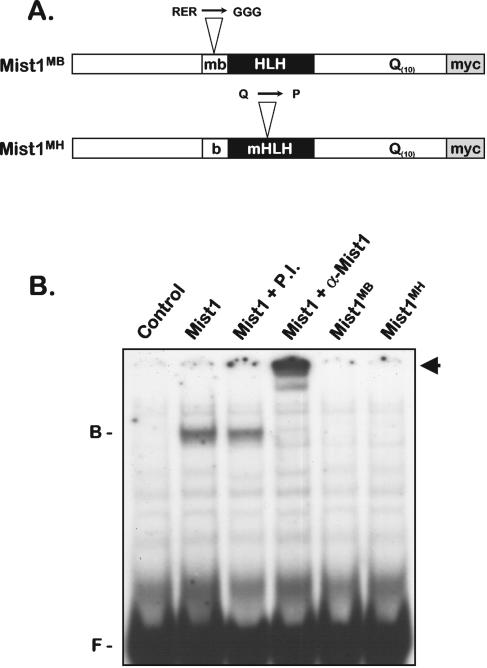

Mist1 gene expression initiates in the developing pancreas at E10.5 and then becomes restricted to the exocrine acinar cells of the adult (31, 32). Although the expression pattern of the Mist1 gene is well defined, little is known regarding the molecular properties associated with this factor. In an effort to perform a molecular dissection of Mist1, we generated mutations in the basic domain (Mist1MB) and in helix 1 of the dimerization domain (Mist1MH) to establish whether these domains were required for formation of a functional complex (Fig. 1A). In vitro protein-protein interaction assays revealed that Mist1 and Mist1MB efficiently formed homodimer complexes, whereas Mist1MH was completely defective in bHLH dimerization (data not shown). As predicted, nuclear extracts from Mist1-expressing cells contained a Mist1 complex that bound to E-box DNA targets (Fig. 1B). This bound complex was supershifted when coincubated with anti-Mist1 but not when incubated with control preimmune serum (Fig. 1B) or with antibodies against several class A bHLH factors (data not shown), suggesting that the identified bound complex represents a Mist1 homodimer. In contrast to these results, cells expressing Mist1MB or Mist1MH did not exhibit any Mist1-DNA complexes (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that binding of Mist1 to DNA requires an intact bHLH motif.

FIG. 1.

Mist1MB and Mist1MH proteins are defective in DNA binding. (A) Schematic drawing of the point mutations present within the Mist1MB and Mist1MH proteins. mb, mutant basic domain; Myc, the C-terminal Myc epitope tag (see text for details); b, basic domain; mHLH, mutant HLH. (B) EMSA using a 32P-labeled E-box oligonucleotide and nuclear extracts from control cells and cells expressing the indicated Mist1 proteins. In some instances, a Mist1 antibody (α-Mist1) or the control preimmune (P.I.) antibody was used in supershift experiments. As predicted, Mist1MB and Mist1MH do not bind to the E-box target. The positions of free DNA (F), bound complex (B), and the Mist1 supershifted complex (arrow) are indicated at the sides of the gel.

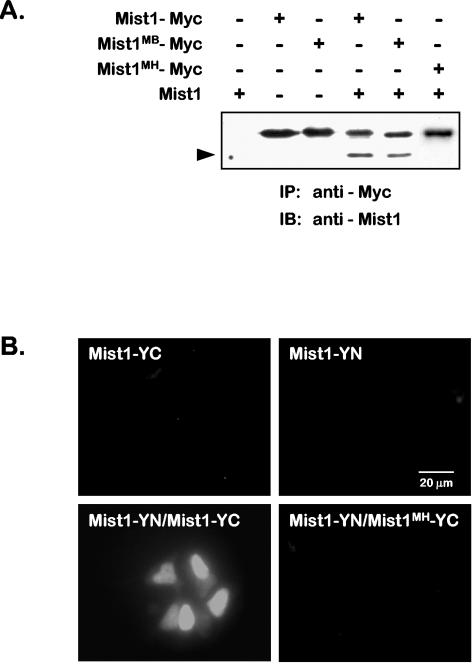

The ability of Mist1MB to form homodimers in vitro prompted us to examine whether Mist1-Mist1MB dimer complexes could form in vivo. Cells in which Myc-tagged Mist1, Mist1MB, or Mist1MH proteins were expressed, along with an untagged Mist1 protein, were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation assays using a Myc antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and processed for immunoblotting using a Mist1 antibody to detect both input proteins. As shown in Fig. 2A, formation of Mist1-Mist1 and Mist1-Mist1MB dimers was observed in cells that coexpressed the respective proteins. In contrast, formation of Mist1-Mist1MH dimers was never detected in these assays. Similar results were obtained using a bimolecular fluorescence complementation approach in which various Mist1 cDNA sequences were cloned in frame into the N or C terminus of the YFP (16). Cells expressing Mist1-YC or Mist1-YN alone or in conjunction with the control YN or YC plasmid exhibited no YFP fluorescence (Fig. 2B). However, when Mist1-YC and Mist1-YN were coexpressed in cells, strong nuclear YFP fluorescence was reconstituted (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, when Mist1MH-YC or Mist1MH-YN were coexpressed with the appropriate Mist1-YC or Mist1-YN plasmid, no fluorescence complementation was achieved, confirming that the helix 1 mutation prevented bHLH dimerization (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Mist1 forms homodimer complexes in vivo. (A) Cells were cotransfected with expression plasmids encoding Mist1, Mist1-Myc, Mist1MB-Myc, or Mist1MH-Myc protein (+). Following transfection, nuclear extracts were isolated and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using a Myc antibody. Precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and then immunoblotted (IB) using a Mist1 antibody. Although Mist1 and Mist1MB coimmunoprecipitate with Mist1, Mist1MH does not form dimers with the wild-type Mist1 protein. The position of the coimmunoprecipitated Mist1 protein is indicated by the arrowhead. Note that the Mist1-Myc proteins exhibit a lower mobility than the wild-type Mist1 protein due to the presence of the Myc epitope tag. (B) Bimolecular fluorescence complementation confirms Mist1 homodimer formation in vivo. Individual Mist1 expression plasmids encoding a Mist1-YFP C terminus (Mist1-YC) fusion protein or a Mist1-YFP N terminus (Mist1-YN) fusion protein were introduced into cells individually or in a pairwise combination. YFP fluorescence is reconstituted only when Mist1-YN and Mist1-YC are coexpressed, demonstrating that Mist1 homodimers are functionally produced in these cells. Note that cells coexpressing Mist1-YN and Mist1MH-YC do not form a functional complex.

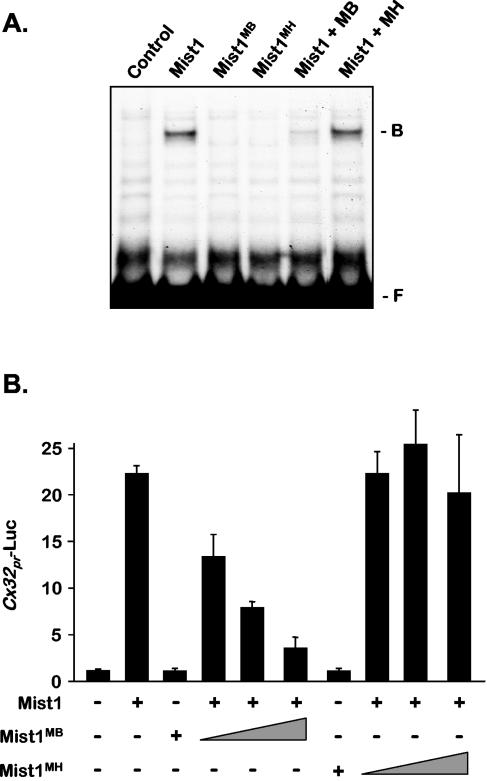

Since Mist1 and Mist1MB readily formed Mist1-Mist1MB dimers in vivo, we next tested whether Mist1MB could influence the DNA binding properties associated with the normal Mist1 protein. As shown in Fig. 3A, when Mist1 and Mist1MB were coexpressed in cells, Mist1MB functioned as an effective inhibitor, preventing Mist1 from interacting with E-box DNA targets. In contrast, Mist1MH, which is defective in bHLH dimerization, had no influence on Mist1 DNA binding activity when coexpressed with the wild-type protein. To further test the ability of Mist1MB to block cellular Mist1 activity, acinar cells were cotransfected with a connexin32 (Cx32) reporter gene (Cx32pr-Luc) and Mist1 expression plasmids, since previous studies have demonstrated that Mist1 activates expression of this acinar-specific gap junction gene (34). As expected, the Cx32pr-Luc gene exhibited low basal expression levels in pancreatic acinar cells, whereas coexpression of Cx32pr-Luc and Mist1 generated a 20- to 25-fold increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 3B). When Mist1MB was coexpressed in these cells, a dose-dependent inhibition of Mist1-induced Cx32pr-Luc expression was observed. This inhibition was not obtained by coexpression of Mist1MH (Fig. 3B). We conclude that Mist1MB functions as a dominant-negative protein in acinar cells by forming DNA-binding defective complexes with Mist1.

FIG. 3.

(A) EMSA using nuclear extracts from control cells and cells expressing the indicated Mist1 proteins. Whereas expression of Mist1MB effectively blocks Mist1 from binding to DNA (Mist1 + MB), Mist1MH has no effect on Mist1 DNA binding activity (Mist1 + MH). The positions of free DNA (F) and bound complex (B) are indicated to the right of the gel. (B) Mist1MB is a potent inhibitor of Mist1-induced expression of the Cx32pr-Luc gene. Pancreatic AR42J cells were cotransfected with the Cx32pr-Luc reporter gene and the indicated Mist1 expression plasmids. The presence (+) or absence (−) of a Mist1 protein and the amount of Mist1MB and Mist1MH (indicated by the thickness of the triangle) are indicated below the bars. Mist1MH has no effect on Cx32pr-Luc expression, whereas Mist1MB functions as a potent inhibitor.

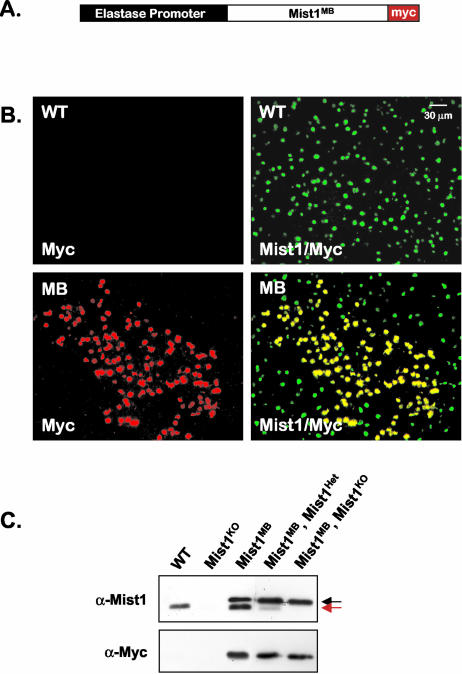

Expression of Mist1MB leads to changes in exocrine gene expression patterns.

Given that Mist1MB is an effective inhibitor of Mist1 activity in cultured cells, we set out to generate Mist1MB mice in which the Mist1MB protein was expressed exclusively in pancreatic acinar cells. A Mist1MB transgene construct (elastasepr-Mist1MB) was produced using the rat elastase 1 promoter to drive acinar-specific expression of the Mist1MB protein (Fig. 4A). Eight lines of transgenic mice were established; they exhibited two distinct elastasepr-Mist1MB expression patterns. Several lines showed Mist1MB expression in ∼95% of all pancreatic acinar cells, whereas other lines exhibited a patchy expression pattern which, nonetheless, was acinar cell specific (Fig. 4B). In all cases, pancreatic islet and duct cells remained Mist1MB negative (data not shown). Immunoblotting confirmed that the Mist1MB protein was expressed at high levels in the pancreas and that Mist1MB expression did not alter endogenous Mist1 protein expression (Fig. 4C). In addition, Mist1MB expression was maintained at similar levels regardless of the endogenous Mist1 genetic background (wild type, heterozygote, and knockout) (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

The elastasepr-Mist1MB-Myc expression plasmid is expressed exclusively in pancreatic exocrine acinar cells. (A) Schematic drawing of the elastasepr-Mist1MB-myc transgene. (B) Pancreas sections from wild-type (WT) and Mist1MB (MB) mice were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis using the Myc antibody to detect expression of the transgene protein and a Mist1 antibody to detect both Mist1 and Mist1MB proteins. Several lines of mice express Mist1MB in a patchy pattern that is nonetheless acinar cell specific (see text for details). (C) Immunoblot of protein extracts from the indicated mouse lines using antibodies against Mist1 (α-Mist1) to detect both endogenous and transgene protein products or using anti-Myc (α-Myc) to detect only the transgene Mist1 product. The Mist1MB-Myc protein exhibits a lower mobility (black arrow) than the wild-type Mist1 protein (red arrow) due to the presence of the Myc epitope tag. Mist1MB, Mist1Het and Mist1MB, Mist1KO indicate genotypes in which the Mist1MB mice were crossed into a heterozygote Mist1 (Mist1Het) (expressing approximately 50% less Mist1 protein) or Mist1 knockout (Mist1KO) (expressing no Mist1) background.

To determine whether Mist1MB expression generated changes in acinar cell characteristics, we examined the elastasepr-Mist1MB mice for phenotypic alterations. Although all lines gave similar results (data not shown), we focused our analysis on several lines of mice that showed the patchy expression pattern, since these animals offered the distinct advantage of allowing a side-by-side phenotypic comparison of acinar cells that expressed the Mist1MB protein and acinar cells that did not express Mist1MB. In this fashion, we were able to examine the cell autonomous nature of the inhibition of Mist1 activity in individual cells.

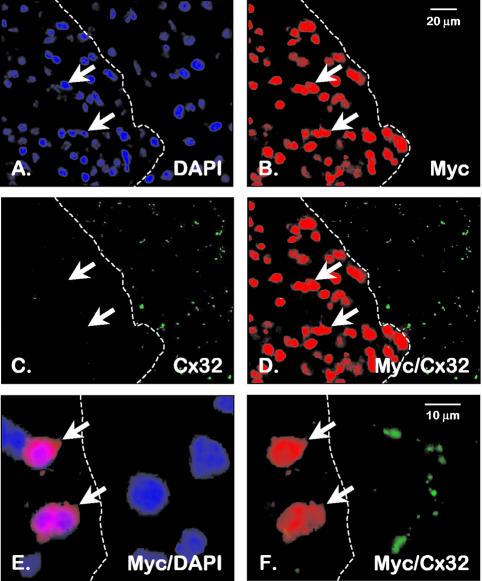

As a first step, we examined connexin32 (Cx32) gene expression, since coexpression of Mist1MB in cultured acinar cells led to a reduction in Cx32 gene activity (Fig. 3B). Analysis of pancreatic sections from Mist1MB mice revealed that the acinar cell-restricted Cx32 protein was completely absent in cells that expressed the Mist1MB protein (Fig. 5). In all cases, acinar cells expressing Mist1MB failed to accumulate Cx32 gap junction plaques, whereas normal levels of this gap junction protein were maintained in adjacent acinar cells that did not express Mist1MB. As expected, Cx32 expression continued normally in salivary gland acinar cells where endogenous Mist1 is expressed but where the elastasepr-Mist1MB transgene is not active (data not shown). These results confirm that inhibition of Mist1 activity in individual acinar cells is sufficient to block expression of the gap junction protein Cx32.

FIG. 5.

Mist1MB-expressing cells do not express the gap junction protein Cx32. Pancreas sections from Mist1MB mice were processed for Cx32 immunofluorescence (green) and Mist1MB-Myc immunofluorescence (red). Mist1MB-expressing cells (identified by the red nuclei and arrows) do not contain detectable levels of the Cx32 gap junction protein (green spots), whereas Mist1MB-negative cells (cells to the right of the broken line) continue to generate normal gap junction plaques. Nuclei in panels A and E were also stained with the DNA fluorochrome DAPI.

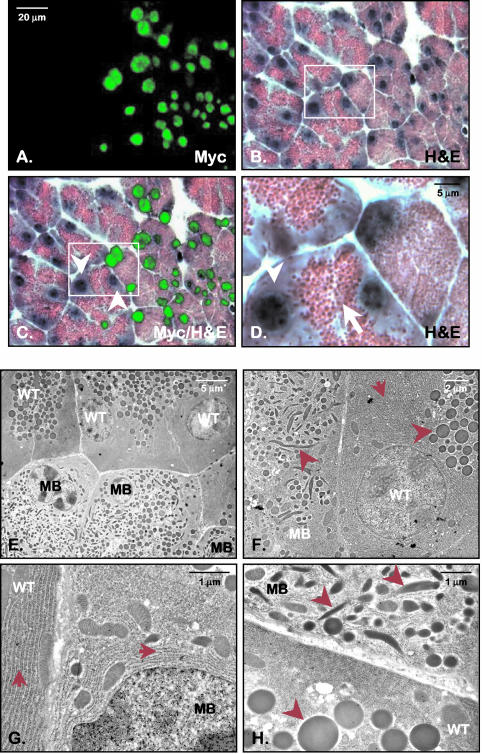

The molecular block in Cx32 gene expression prompted us to examine other aspects of the Mist1MB cells to determine whether altering the functional bHLH components would lead to additional cellular changes. Routine histology on pancreatic sections from the Mist1MB mice revealed severe alterations in tissue architecture that were restricted to the Mist1MB cells. Hematoxylin and eosin staining suggested that Mist1MB-expressing cells contained reduced amounts of endoplasmic reticulum, since they did not show the normal basophilic staining pattern that is typical of wild-type specimens (Fig. 6A to D). Mist1MB cells also did not establish the normal basal-to-apical organization that is a hallmark of pancreatic acinar cells, whereas adjacent non-Mist1MB-expressing cells retained their normal polarized characteristics. Indeed, Mist1MB cells were smaller and more compact in the tissue and showed a disruption in zymogen granule clustering (Fig. 6D). Electron microscopy confirmed the disarray of organelle distribution. Zymogen granules were grossly misshapen and not clustered within the apical regions of the Mist1MB cells (Fig. 6E to H). Similarly, the endoplasmic reticulum in Mist1MB cells was reduced and evenly dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 6E to H). In contrast, Mist1MB-negative cells retained a normal, polarized morphology.

FIG. 6.

Pancreatic acinar cells expressing the Mist1MB protein exhibit a disorganized cellular structure. (A to D) Myc immunohistochemistry, coupled with hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E), revealed that Mist1MB acinar cells exhibited a severely disorganized structure compared to non-Mist1MB-expressing cells. Note that the typical basophilic staining of the endoplasmic reticulum seen in non-Mist1MB-expressing cells (arrowhead) is completely absent in the Mist1MB-expressing cells. The boxed area in panels B and C is shown at a higher magnification in panel D. Zymogen granules, which are clustered and readily visible in control cells (arrow) are not organized in the Mist1MB-expressing cells. (E to H) Transmission electron microscopy, coupled with anti-Myc immunogold labeling, confirms that Mist1MB-expressing cells (MB) are highly disorganized, showing no zymogen granule organization, a disruption in zymogen granule morphology (arrowheads), and a greatly reduced and unorganized endoplasmic reticulum (arrows). All Mist1MB-expressing cells were identified by the presence of nuclear localized anti-Myc gold particles which are readily apparent in panel G. WT, wild-type cell (not expressing Mist1MB).

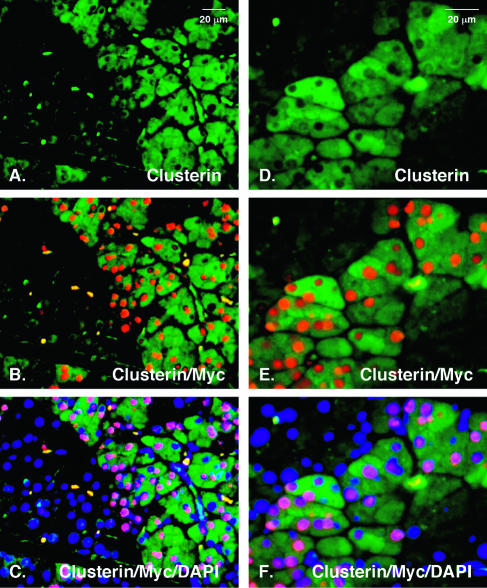

The disruption in cellular organization observed in Mist1MB cells suggested that inhibition of Mist1 activity prevented acinar cells from attaining a fully mature state. Previously, it was difficult to make clear distinctions between newly formed, immature acinar cells and fully functional acinar cells, since molecular markers of acinar cell differentiation, such as amylase and carboxypeptidase, do not discriminate between embryonic, immature, and mature acinar cells. However, a recent study by Min et al. (28) has shown that clusterin, a glycoprotein expressed by many cell types under different physiological conditions, demarcates immature, newly formed pancreatic acinar cells. We therefore examined clusterin expression in the Mist1MB model system. As shown in Fig. 7, immunofluorescence analysis revealed that the majority of Mist1MB-expressing cells coexpressed high levels of clusterin, whereas adjacent Mist1MB-negative cells remained clusterin negative. As expected, pancreatic sections from wild-type mice contained only rare clusterin-positive acinar cells in the entire pancreas (data not shown) (28). These results provide additional evidence that Mist1MB cells do not attain a fully mature acinar phenotype and that inhibition of Mist1 activity produces a dramatic effect on how acinar cells retain their normal cellular characteristics.

FIG. 7.

Clusterin expression is dramatically elevated in Mist1MB acinar cells. Immunofluorescence showing clusterin staining (green in panels A and D), clusterin and Myc staining (red nuclei in panels B and E), or clusterin, Myc, and DAPI staining (blue nuclei in panels C and F) reveal that Mist1MB-expressing cells contain high levels of clusterin protein. In contrast, non-Mist1MB-expressing cells (Myc negative) remain clusterin negative. Panels A to C and D to F represent two different areas of the pancreas.

Mist1MB cells exhibit acinar-to-ductal metaplasia.

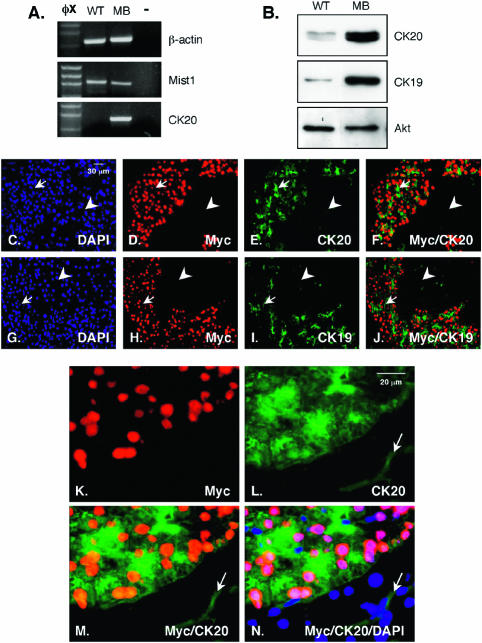

The results from the Mist1MB mice indicated that disruption of Mist1 activity prevented acinar cells from fully differentiating, suggesting that Mist1MB cells may acquire a new cellular identity. Indeed, several studies have shown that acinar cells can transdifferentiate into pancreatic duct cells under a variety of experimental conditions (2, 33, 38). In an effort to determine whether inhibition of the Mist1 bHLH regulatory pathway alters acinar cell identity, we examined Mist1MB cells for expression of duct cell gene products. Pancreatic tissue samples from the Mist1MB mice showed elevated transcript and protein levels of the duct cell-restricted genes CK20 and CK19 compared to the levels detected in wild-type samples (Fig. 8A and B). These results suggested that disruption of Mist1 activity by use of the dominant-negative Mist1MB protein induced an increase in these duct cell gene products.

FIG. 8.

Mist1MB acinar cells express the duct cell proteins CK19 and CK20. (A) Semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis of CK20 expression in wild-type (WT) and Mist1MB (MB) pancreas tissue. CK20 transcript levels are greatly enhanced in the Mist1MB mice. Lane −, no-RNA control. (B) Immunoblot analysis of CK20 and CK19 expression reveals that Mist1MB cells contain high levels of these duct cell proteins. Akt protein levels serve as a loading control. (C to J) Immunofluorescence using CK20 (C to F) and CK19 (G to J) antibodies on sections obtained from Mist1MB samples. Mist1MB-expressing acinar cells (arrows) express high levels of CK20 and CK19, while non-Mist1MB-expressing cells (arrowheads) remain CK20 and CK19 negative. (K to N) High magnification of acinar cells from Mist1MB mice showing that individual acinar cells expressing the Mist1MB protein (Myc) coexpress CK20. The arrows in panels L, M, and N demarcate a normal CK20-positive intercalated duct.

Immunofluorescence of Mist1MB pancreatic tissue sections confirmed that Mist1MB cells coexpressed high levels of CK20 and CK19, whereas non-Mist1MB-expressing cells remained CK20 and CK19 negative (Fig. 8C to J). Further analysis of the Mist1MB samples revealed that CK19 (data not shown) and CK20 expression was restricted to the intercalated duct cells in the non-transgene-expressing areas, whereas for Mist1MB cells, CK19 and CK20 were found coexpressed with Mist1MB within acinar cells (Fig. 8K to N). Although Mist1MB expression affected the acinar cell phenotype, the presence of Mist1MB acinar cells had no detrimental effect on the endocrine pancreas. Insulin expressing β cells were readily detected in all Mist1MB mice (data not shown). We conclude that inhibition of Mist1 activity via expression of Mist1MB results in dramatic alterations of the exocrine pancreas, ultimately leading to a cell autonomous activation of duct cell-specific genes and an overall block in acinar cell maturation events.

DISCUSSION

The pancreas is a complex organ that develops from an evagination of the primitive foregut. During development, a minimum of three distinct cell lineages are established that differentiate into an endocrine component (α, β, δ, and PP cells), an exocrine component (acinar cells), and a duct cell component (interlobular, intralobular, and intercalated ducts) (3, 21, 43). The precise signaling pathways (8, 14, 20, 24) and transcription factor circuitry (7, 8, 10, 35) that are instrumental in these developmental decisions are rapidly being defined through elegant mouse genetic studies. However, the pathways that are critical to maintaining the fully differentiated state have not been well characterized.

In this report, we show that inhibition of Mist1, a bHLH transcription factor that is expressed in exocrine pancreatic cells, dramatically affects the maintenance of the mature acinar cell phenotype. Unlike most bHLH proteins, Mist1 is unique in that only one Mist1 family member exists in the human, mouse, Drosophila, and sea squirt genomes (25). Similarly, Mist1 exhibits the unusual bHLH property of forming homodimers, suggesting that Mist1 function is not dependent upon its dimerization with a class A bHLH factor. Indeed, expression of the Mist1MB protein in acinar cells leads to formation of Mist1-Mist1MB dimers that are defective in DNA binding. Thus, Mist1MB functions as a dominant-negative factor by preventing Mist1-DNA interactions.

The pattern of Mist1 gene expression is also distinct among most transcription factors, since the Mist1 protein is found exclusively in serous exocrine cell types (pancreas, salivary glands, and lacrimal gland) (31), each of which functions to produce secreted products which are transported through elaborate ductal networks. This restricted expression pattern suggests that Mist1 functions to regulate genes that are involved in exocytosis, maintenance of cellular polarity, or monitoring of normal acinar-ductal homeostasis. Indeed, Mist1 null mice show altered expression of several genes whose products are involved in regulated secretion (32). Inhibition of Mist1 activity in the Mist1MB mice similarly leads to severe changes in the intracellular organization of cells, where zymogen granules are misshapen, smaller, and poorly organized and the endoplasmic reticulum is reduced and diffusely positioned throughout the cytoplasm. Mist1MB cells also exhibit a twofold increase in overall acinar cell number and an identical twofold increase is similarly observed in Mist1knockout (Mist1KO) animals (unpublished results). The mechanisms that are responsible for generating this increase are unknown but do not involve changes in the expression levels of several cell cycle regulators, including Ki-67 and PCNA (unpublished results). Instead, the increase in cell number appears to reflect an increase in the packing of exocrine cells within individual acini. Further studies will be needed to more completely appreciate the significance of these observations.

Analysis of Mist1MB cells also revealed that they fail to express the Cx32 protein and do not accumulate functional gap junction plaques. The inability of Mist1MB cells to communicate through gap junctions may be important to maintaining a normal acinar architecture and achieving a normal mature phenotype. Similar cellular changes often are observed in a number of pancreatic disease states, including chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer (4, 39), suggesting that Mist1 activity may become compromised under these disease situations. How these changes alter the overall function of the exocrine pancreas remains to be determined, but it is clear that Mist1 is a key regulator of pancreatic homeostasis in the adult organ.

A third characteristic of Mist1MB cells is the activation of duct cell-restricted genes. The exocrine pancreas consists of an intricate ductal network that includes the large interlobular and intralobular ducts as well as the smaller intercalated ducts which are intimately associated with acinar cells and individual acini (3). Intercalated ducts coexpress CK19 and CK20, while intralobular and interlobular ducts express CK19 and CK7, respectively (6) (unpublished results). The ability of Mist1MB cells to activate and retain expression of the intercalated duct cell CK19 and CK20 proteins suggests two possible models. In the first model, Mist1MB cells may developmentally arrest in a pancreatic progenitor state in which they coexpress acinar and duct cell gene products. Lineage tracing studies from Gu et al. (12) support a model for pancreatic cell commitment where duct and acinar cell lineages diverge from a common progenitor cell prior to E12.5. This developmental age is also the approximate time that the elastase 1 gene becomes transcriptionally active in the developing pancreas (9). Thus, expression of Mist1MB at this early stage may influence how progenitor cells make appropriate decisions regarding the commitment to an acinar versus duct cell lineage. Although this is an attractive model to explain the acinar-duct cell phenotype of Mist1MB cells, it is unlikely that this mechanism operates in the Mist1MB mice, since we have been unable to detect Mist1MB protein in the embryonic pancreas (unpublished results).

A second possible model is that Mist1MB cells transdifferentiate into duct cells. The ability of acinar cells to transdifferentiate into duct cells has been documented in several cell culture systems (2, 33) and in transgenic mice expressing transforming growth factor alpha (38). Acinar-to-ductal metaplasia also has been reported in cases of chronic pancreatitis and in experimentally induced pancreatic cancer (4), suggesting that the default pathway for these acinar disease states is to revert to a duct cell lineage. Indeed, Mist1MB-expressing cells retain many characteristics of cells undergoing pancreatitis and early stages of pancreatic cancer (4, 42, 44, 45), including reversion to a more immature cell type and activation of clusterin gene expression. These observations suggest that Mist1 regulates genes that lock in the terminally differentiated acinar cell state while preventing aberrant cell growth and function and that expression of Mist1MB in a fully differentiated acinar cell is sufficient to cause this phenotypic switch. The molecular mechanisms by which these changes occur remain unknown but likely are not simple. For example, transient transfection of a Mist1MB expression plasmid into the pancreatic cell line AR42J failed to activate the endogenous CK19 gene (unpublished results), suggesting that other factors or different cellular contexts likely come into play in Mist1-induced acinar-to-ductal metaplasia. For this reason, additional analyses of Mist1MB and Mist1KO mice will be critical to identifying Mist1-regulated genes and to characterizing how normal Mist1 activity blocks acinar-to-ductal phenotypic changes.

Pancreatic mouse models have provided a wealth of information concerning the embryonic development of individual cell lineages and the molecular basis for a variety of pancreatic disease states, including diabetes, pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer (5, 8, 11, 41). Although Mist1 null mice have been generated, the complex phenotype associated with these animals has made it difficult to determine which cellular alterations are specifically due to the absence of Mist1 and which changes are the result of long-term physiological consequences ascribed to a Mist1 null pancreas. Mist1MB mice have, for the first time, permitted an examination of the cell autonomous consequence of inhibiting endogenous Mist1 activity in the pancreas. We are now poised to ask key questions regarding how cells respond to changes within a local environment, since it will be possible to examine normal and abnormal acinar cells within the same tissue. In addition to designing studies to evaluate how normal and Mist1MB-expressing acinar cells communicate and influence neighboring acinar cells, it will be possible to determine how altered acinar cells affect adjacent islet and duct cells. Each of these studies will help to define the bHLH transcriptional circuits that are critical to maintaining normal pancreatic homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ray MacDonald, Galvin Swift, Rolf Kemler, Doris Stoffers, Chang-Deng Hu, and Tom Kerppola for providing valuable reagents used in this study and Judy Hallett and the Purdue Cancer Center Transgenic Mouse Core Facility for their assistance in generating the mice described in this report.

This work was supported in part by grants to S.F.K. from the National Institutes of Health (DK55489) and from the Purdue University Cancer Center. L.Z and J.M.R. were supported by Purdue Research Foundation graduate fellowships, and T.T. was supported by a GAANN graduate student training grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlgren, U., J. Jonsson, and H. Edlund. 1996. The morphogenesis of the pancreatic mesenchyme is uncoupled from that of the pancreatic epithelium in IPF1/PDX1-deficient mice. Development 122:1409-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arias, A. E., and M. Bendayan. 1993. Differentiation of pancreatic acinar cells into duct-like cells in vitro. Lab. Investig. 69:518-530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashizawa, N., H. Endoh, K. Hidaka, M. Watanabe, and S. Fukumoto. 1997. Three-dimensional structure of the rat pancreatic duct in normal and inflammated pancreas. Microsc. Res. Tech. 37:543-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bockman, D. E. 1995. Toward understanding pancreatic disease: from architecture to cell signaling. Pancreas 11:324-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonner-Weir, S., and A. Sharma. 2002. Pancreatic stem cells. J. Pathol. 197:519-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouwens, L. 1998. Cytokeratins and cell differentiation in the pancreas. J. Pathol. 184:234-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakrabarti, S. K., and R. G. Mirmira. 2003. Transcription factors direct the development and function of pancreatic beta cells. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 14:78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edlund, H. 2002. Pancreatic organogenesis—developmental mechanisms and implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:524-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gittes, G. K., and W. J. Rutter. 1992. Onset of cell-specific gene expression in the developing mouse pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:1128-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradwohl, G., A. Dierich, M. LeMeur, and F. Guillemot. 2000. neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1607-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu, G., J. R. Brown, and D. A. Melton. 2003. Direct lineage tracing reveals the ontogeny of pancreatic cell fates during mouse embryogenesis. Mech. Dev. 120:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu, G., J. Dubauskaite, and D. A. Melton. 2002. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development 129:2447-2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison, K. A., J. Thaler, S. L. Pfaff, H. Gu, and J. H. Kehrl. 1999. Pancreas dorsal lobe agenesis and abnormal islets of Langerhans in Hlxb9-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 23:71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hebrok, M., S. K. Kim, B. St. Jacques, A. P. McMahon, and D. A. Melton. 2000. Regulation of pancreas development by hedgehog signaling. Development 127:4905-4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller, R. S., D. A. Stoffers, T. Bock, K. Svenstrup, J. Jensen, T. Horn, C. P. Miller, J. F. Habener, O. D. Madsen, and P. Serup. 2001. Improved glucose tolerance and acinar dysmorphogenesis by targeted expression of transcription factor PDX-1 to the exocrine pancreas. Diabetes 50:1553-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu, C. D., Y. Chinenov, and T. K. Kerppola. 2002. Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol. Cell 9:789-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen, J., E. E. Pedersen, P. Galante, J. Hald, R. S. Heller, M. Ishibashi, R. Kageyama, F. Guillemot, P. Serup, and O. D. Madsen. 2000. Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1. Nat. Genet. 24:36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonsson, J., L. Carlsson, T. Edlund, and H. Edlund. 1994. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature 371:606-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawaguchi, Y., B. Cooper, M. Gannon, M. Ray, R. J. MacDonald, and C. V. Wright. 2002. The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nat. Genet. 32:128-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, S. K., and M. Hebrok. 2001. Intercellular signals regulating pancreas development and function. Genes Dev. 15:111-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim, S. K., and R. J. MacDonald. 2002. Signaling and transcriptional control of pancreatic organogenesis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12:540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong, Y., S. E. Johnson, E. J. Taparowsky, and S. F. Konieczny. 1995. Ras p21Val inhibits myogenesis without altering the DNA binding or transcriptional activities of the myogenic basic helix-loop-helix factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5205-5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krapp, A., M. Knofler, B. Ledermann, K. Burki, C. Berney, N. Zoerkler, O. Hagenbuchle, and P. K. Wellauer. 1998. The bHLH protein PTF1-p48 is essential for the formation of the exocrine and the correct spatial organization of the endocrine pancreas. Genes Dev. 12:3752-3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lammert, E., O. Cleaver, and D. Melton. 2001. Induction of pancreatic differentiation by signals from blood vessels. Science 294:564-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ledent, V., O. Paquet, and M. Vervoort. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of the human basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Genome Biol. 3:research0030.1-0030.18. [Online.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, H., S. Arber, T. M. Jessell, and H. Edlund. 1999. Selective agenesis of the dorsal pancreas in mice lacking homeobox gene Hlxb9. Nat. Genet. 23:67-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massari, M. E., and C. Murre. 2000. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:429-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Min, B. H., B. M. Kim, S. H. Lee, S. W. Kang, M. Bendayan, and I. S. Park. 2003. Clusterin expression in the early process of pancreas regeneration in the pancreatectomized rat. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 51:1355-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naya, F. J., H. P. Huang, Y. Qiu, H. Mutoh, F. J. DeMayo, A. B. Leiter, and M. J. Tsai. 1997. Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/neuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 11:2323-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Offield, M. F., T. L. Jetton, P. A. Labosky, M. Ray, R. W. Stein, M. A. Magnuson, B. L. Hogan, and C. V. Wright. 1996. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development 122:983-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pin, C. L., A. C. Bonvissuto, and S. F. Konieczny. 2000. Mist1 expression is a common link among serous exocrine cells exhibiting regulated exocytosis. Anat. Rec. 259:157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pin, C. L., J. M. Rukstalis, C. Johnson, and S. F. Konieczny. 2001. The bHLH transcription factor Mist1 is required to maintain exocrine pancreas cell organization and acinar cell identity. J. Cell Biol. 155:519-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rooman, I., Y. Heremans, H. Heimberg, and L. Bouwens. 2000. Modulation of rat pancreatic acinoductal transdifferentiation and expression of PDX-1 in vitro. Diabetologia 43:907-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rukstalis, J. M., A. Kowalik, L. Zhu, D. Lidington, C. L. Pin, and S. F. Konieczny. 2003. Exocrine specific expression of Connexin32 is dependent on the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Mist1. J. Cell Sci. 116:3315-3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwitzgebel, V. M. 2001. Programming of the pancreas. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 185:99-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwitzgebel, V. M., D. W. Scheel, J. R. Conners, J. Kalamaras, J. E. Lee, D. J. Anderson, L. Sussel, J. D. Johnson, and M. S. German. 2000. Expression of neurogenin3 reveals an islet cell precursor population in the pancreas. Development 127:3533-3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slack, J. M. 1995. Developmental biology of the pancreas. Development 121:1569-1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song, S. Y., M. Gannon, M. K. Washington, C. R. Scoggins, I. M. Meszoely, J. R. Goldenring, C. R. Marino, E. P. Sandgren, R. J. Coffey, Jr., C. V. Wright, and S. D. Leach. 1999. Expansion of Pdx1-expressing pancreatic epithelium and islet neogenesis in transgenic mice overexpressing transforming growth factor alpha. Gastroenterology 117:1416-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steer, M. L. 1997. Pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Digestion 58(Suppl. 1):46-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swift, G. H., S. D. Rose, and R. J. MacDonald. 1994. An element of the elastase I enhancer is an overlapping bipartite binding site activated by a heteromeric factor. J. Biol. Chem. 269:12809-12815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talamini, G., M. Falconi, C. Bassi, M. Mastromauro, R. Salvia, and P. Pederzoli. 2000. Chronic pancreatitis: relationship to acute pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. JOP 1(Suppl. 3):69-76. [Online.] [PubMed]

- 42.Wildi, S., J. Kleeff, H. Maruyama, C. A. Maurer, H. Friess, M. W. Buchler, A. D. Lander, and M. Korc. 1999. Characterization of cytokeratin 20 expression in pancreatic and colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 5:2840-2847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson, M. E., D. Scheel, and M. S. German. 2003. Gene expression cascades in pancreatic development. Mech. Dev. 120:65-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie, M. J., Y. Motoo, S. B. Su, H. Mouri, K. Ohtsubo, F. Matsubara, and N. Sawabu. 2002. Expression of clusterin in human pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 25:234-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie, M. J., Y. Motoo, S. B. Su, and N. Sawabu. 2001. Expression of clusterin in pancreatic acinar cell injuries in vivo and in vitro. Pancreas 22:126-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]