Abstract

With the advent of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with alglucosidase alfa (rhGAA, Myozyme®) for Pompe disease, the clinical course of the disease has changed. We have previously described the poor outcome in cross reactive immunologic material (CRIM)-negative and high-titer CRIM-positive (HTCP) patients secondary to high sustained antibody titers (HSAT) which effectively neutralize ERT efficacy. Various immunomodulation strategies are being explored to diminish the immune response to ERT. However, once HSAT are formed, tolerization therapy has uniformly failed to lower antibody titers. Here we describe a case in which immunomodulation over a prolonged period of 28 months with cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, increased doses of rhGAA and rituximab failed to lower antibody titers and resulted in continued clinical decline in an infantile Pompe disease patient treated with ERT. Thus, it appears that the failure to target the antibody-secreting plasma cells responsible for HSAT led to a failure of tolerance induction. This is the first report using this combination of agents over a very extensive period of time with no success.

Keywords: Pompe disease, Antibodies, Immunomodulation, Cyclophosphamide, Rituximab, Plasmapheresis

1. Introduction

Pompe disease (glycogen storage disease type II) is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disease caused by deficiency of acid α-glucosidase (GAA), which leads to accumulation of glycogen in several cell types, most notably cardiac, skeletal and smooth muscle [1]. Prior to the development of alglucosidase alfa enzyme replacement therapy (ERT, rhGAA, Myozyme®) and its approval in 2006, patients with infantile-onset Pompe disease (IPD) rarely survived past one year of age [2,3]. With the advent of ERT, patients with IPD have realized prolonged survival and improved quality of life [4–6]. However, patients with high sustained antibody titers (HSAT) as defined by antibody titers of ≥1: 51,200 on two separate occasion after ≥6 months on ERT, demonstrate a diminished response to enzyme replacement therapy and often suffer rapidly progressive clinical deterioration [7,8]. With the hope that curtailing the immune response against rhGAA could allow for improved response to ERT, the use of immunomodulation is currently being explored. While some success has been noted in the naïve and early-ERT setting [9,10], no immune tolerance induction (ITI) protocol has successfully diminished antibody titers and improve clinical course in the face of HSAT in IPD patients. The CRIM-negative Pompe patient presented here demonstrates the failure of immunomodulatory regimens comprised cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, increased doses of rhGAA and rituximab at different time points over a 28-month period, with persistence of HSAT and progressive clinical decline and death.

2. Case report

2.1. Initial presentation and enzyme replacement therapy

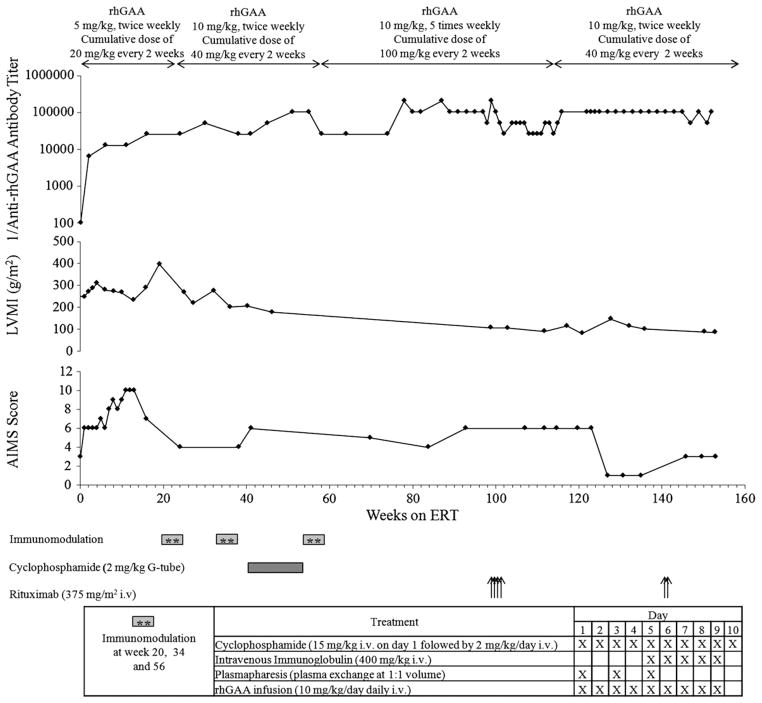

The patient was a 2 month-old Caucasian boy who first presented with cardiac arrest during an inguinal hernia repair. Muscle biopsy performed during the surgery demonstrated glycogen storage. Pompe disease was suspected and a diagnosis was confirmed on skin fibroblast testing which showed GAA activity of 2.4 nmol/h/mg protein (<1% of normal GAA activity). Western blot testing on a skin fibroblast sample later revealed CRIM negative status and mutation analysis showed a missense mutation on one allele (c.1687C>T) and a deletion mutation on the second (c.722_723delTT). Urine Glc4 evaluation was consistent with Pompe disease. He had severe hypotonia with weak respiratory muscle strength at baseline. Two dimensional, M-mode echocardiogram at baseline showed severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular mass index (LVMI) of 253 g/m2, ≥2 SD above the normal mean for age (64 g/m2; Fig. 1) [11]. Motor status evaluated by Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) score was 5 (age equivalent of a 0.75 month old infant; <5% of normal; Fig. 1). The Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) is an observational assessment scale which was constructed to measure the gross motor maturation in infants from birth through 18 months [12,13]. The patient was started on enzyme replacement therapy with rhGAA at age 4.2 months (5 mg/kg, twice weekly; cumulative dose of 20 mg/kg every 2 weeks) as 1 of 3 patients (patient 1) who participated in the first phase I/II clinical trial of rhGAA [14] and antibodies to rhGAA were not present at baseline. In the first 12 weeks of ERT, overall improvements in cardiac function (LVMI 232 g/m2 at week 12), respiratory function, muscle strength and motor development (AIMS score10 at week 12; age equivalent of a 1 month old infant) were observed.

Fig. 1.

Anti-rhGAA antibody titers, left ventricular mass index (LVMI), Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) score and time course of administration of immunomodulatory agents corresponding to weeks on enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). A 10-day extensive immunomodulation protocol using cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, increased dose of rhGAA, and rituximab failed to diminish antibody titers. Of note, decrease in LVMI correlates with increased dose of rhGAA (cumulative dose of 100 mg/kg every other week as compared to recommended dose of 20 mg/kg every other week in Myozyme package insert), which was administered between weeks 56 and 112. Lowest LVMI value in this patient was 80.4 g/m2 at week 121 on ERT, which remained above the upper limit of normal LVMI for an infant of 64 g/m2. After an initial period of improvement, AIMS score declined and remained at <5% of normal age despite increased dose of rhGAA and extensive immunomodulation.

2.2. Rising antibody titers and worsening clinical status (week 0 to week 20 of ERT)

Antibody titers at all available time points are shown in Fig. 1. By week 4, the patient seroconverted with anti-rhGAA antibody titers of 1:6400. Antibody titers continued to rise with titers of 1:12,800 and 1:25,600 at weeks 12 and 16, respectively. Following an episode of viral pneumonia and respiratory distress at week 17, he was intubated to ensure adequate ventilation. Tracheostomy was performed at week 19. A gastrostomy tube was placed at the same time because of feeding difficulties. LVMI rose to 397 g/m2 at week 19. With the worsening clinical status and increasing antibody titers, ITI therapy was attempted.

2.3. Immunomodulation with cyclophosphamide, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and increased dose of rhGAA (week 20 to week 99 of ERT)

Immunomodulation was initiated at week 20 of ERT. Details regarding the 10-day extensive immunomodulatory protocol consisting of cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, and increased doses of rhGAA are described in Fig. 1. This immunomodulation protocol was well-tolerated except for mild hematuria, a known side effect of cyclophosphamide which required treatment with 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate (MESNA). Despite this, his titers remained at the same level (1:25,600) through week 24 and increased to 1:51,200 at week 30. Although there was a slight improvement in cardiac status (LVMI 218 g/m2 at week 27), his motor status declined further (AIMS score 4 at week 24). Because of this marked blunting of the rhGAA therapeutic effect and rising antibody titer the same immunomodulation protocol was repeated at week 34 and week 56. In addition to the repeating the 10-day extensive immunomodulatory protocols twice which included daily cyclophosphamide treatment, additional cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg through G-tube) was continued between the immunomodulation attempts (week 42 through week 55; Fig. 1). At week 56, the patient was started on high-dose rhGAA (10 mg/kg every day for 5 days/week) to increase the therapeutic effect of enzyme. Despite this aggressive immunomodulation treatment approach, antibody titers continued to rise: 1:25,600 (weeks 38 and 41); 1:102,400 (weeks 51 and 55); and in the range of 1:204,800 (weeks 78 through 99). With the increased dose of rhGAA, there was further improvement in cardiac status (LVMI 106 g/m2 at week 99) but LVMI did not normalize (Fig. 1) [11]. Moreover, there was no motor improvement (AIMS score 4 to 6; age equivalent of a 0.5–1 month old infant; weeks 38 through 99; Fig. 1) [13]. He remained ventilator dependent throughout this time with no improvement in respiratory status.

2.4. Subsequent clinical course with increased dose of rhGAA and immunomodulation with rituximab (week 99 through week 153 of ERT)

From weeks 99 through 102, the patient received 4 doses of rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody; 375 mg/m2/dose, weekly) in hope of eliminating the B cells. The CD19 (circulating B cells) count dropped to 0% immediately after starting rituximab and there was an initial transient decrease in antibody titers (1:204,800 at week 99 to 1:25,600 at week 102) with titers rising back to 1:51,200 at week 104 and 1:102.400 at week 116. No clinical improvement was achieved during this time despite treatment with high doses of rhGAA. Due to patient fatigue and a lack of clinical response, the rhGAA dose was reduced to 10 mg/kg twice weekly (cumulative dose of 40 mg/kg every other week) from week 112 onwards. He received two more doses of weekly rituximab at weeks 140 and 141 with no decrease in antibody titer (1:102,400 through week 152). Despite the improvement in cardiac status (LVMI 85 g/m2 at week 153), his motor (AIMS score 1–3; age equivalent of <0.5 month infant) and respiratory status never improved. At week 153 (age 3 years 3 months), ERT was stopped due to limited clinical benefit from ERT and immunomodulation and the patient died at the age of 4 years 2 months due to withdrawal of ventilatory support.

3. Discussion

Here we present the failure of immunomodulation with different combinations of cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, increased doses of rhGAA and rituximab at different time points over a 28-month period in a CRIM-negative IPD patient with HSAT. The ITI protocol used for this patient was based on earlier success in other disorders treated with therapeutic proteins [15–17]. The rationale for using high-dose rhGAA therapy over a prolonged period was based on a previous case report by Brady et al., wherein gradual reduction of neutralizing antibody titers over many months of continued exposure to high doses of ERT was noted in a patient with Gaucher disease type III. In that report, it was suggested that high dose ERT may be an important factor in immune modulation [17]. In addition, rituximab was added to the protocol based on its ability to target B cells, the source of antibody producing plasma cells.

While the patient demonstrated initial improvements in LVMI and AIMS score upon the initiation of ERT, these improvements were short-lived. Systematic evaluation of other IPD patients has further demonstrated the negative impact of HSAT on treatment outcome [8]. After seroconversion at week 4, this patient’s antibody titers continued to rise and were accompanied by an increase in LVMI. After 20 weeks on ERT, a 10-day extensive protocol of cyclophosphamide, IVIG, plasmapheresis and increased dose of rhGAA was initiated but this course failed to achieve sustained reduction of antibody titers and, while an improvement in LVMI was noted, the patient’s motor function declined further. The 10-day immunomodulation protocol was repeated twice, with continued daily cyclophosphamide treatment in between. Despite this and the increase in rhGAA dose, the AIMS score did not improve and the patient remained ventilator-dependent, with only some improvement in cardiac status as indicated by improvement of LVMI. At week 99, immunomodulation with rituximab was attempted to target the B cell population. Despite the elimination of peripheral B cells a sustained decline in antibody titers was not achieved. The patient subsequently succumbed to respiratory arrest.

While our patient’s LVMI did improve with immunomodulation and increased-dose ERT, it did not normalize as it typically does in “good ERT responders” (low titer CRIM positive — LTCP patients) [8]. His motor and respiratory status failed to improve. It is likely that disproportionate improvement in LVMI, even in presence of HSAT, can be attributed to increased dosage of ERT and the presence of increased levels of mannose-6-phosphate receptors (by which rhGAA is taken up by cells) in cardiac myocytes, compared to skeletal muscle [18,19]. Furthermore, there is better perfusion in heart muscle compared to skeletal muscle, allowing for better delivery of ERT to cardiac myocytes. Indeed, preclinical studies have shown that only a small amount of infused enzyme actually reaches the skeletal muscle [20]. Thus, in the presence of HSAT, it is possible that the amount of enzyme available may not be sufficient to achieve a clinical benefit in skeletal muscle as opposed to cardiac muscle.

Several different ITI regimens have been subsequently investigated for their potential to prevent the development of HSAT and subsequent clinical decline in patients with Pompe disease on ERT. Methotrexate, mycophenolate and cyclosporin A/azathioprine have been tested in Pompe mice, while rituximab, plasmapheresis, IVIG, and methotrexate have been used in different combinations in patients with Pompe disease to counteract rhGAA-specific antibodies or immune complex formation [10,21,22]. In one CRIM-negative patient from the first clinical trial, a approach similar to the one described here was attempted using a combination of increased rhGAA dose (up to 10 mg/kg daily), frequent plasmapheresis and IVIG administration, and daily cyclophosphamide to counteract increasing rhGAA antibody titers and clinical decline. This patient’s course was complicated by nephrotic syndrome due to immune complex mediated nephritis, persistently high antibody titers (1:204,800) and continued clinical decline. A single case of successful elimination of rhGAA-specific antibodies after treatment with rituximab, methotrexate and IVIG has been reported [10]. However, it must be noted that the patient in that case developed antibody titers of about 1:1600 and was relatively early in his treatment course, whereas patients with HSAT who demonstrate poor response to ERT maintain titers ≥1:51,200 [8,10]. There have been no reports of successful immunomodulation in IPD with HSAT. A more recent report describes successful immune tolerance induction in the naïve or early-ERT setting in 4 infantile-onset Pompe patients treated with rituximab, methotrexate, and IVIG [9]. The success of this regimen in these patients is likely attributable to its use in the naïve or early-ERT setting, at which time the entrenched immune response, mediated by long lived plasma cells, has not yet been established. More recently, ERT in late onset Pompe disease has shown to induce pro-inflammatory T-cell responses in addition to the antibody response, which warrants further evaluation [23].

New approaches to ITI are needed to control the pre-existing immune response associated with high titers and sustained duration. While many of the agents used in the protocols described above have targeted T and/or B lymphocytes or acted non-specifically to remove immune complexes from the circulation, none of these agents has targeted plasma cells, which are the main source of antibody production once the humoral immune response is well-established. An agent that targets plasma cells might be effective in patients who have already developed HSAT and experienced clinical decline. The use of such an agent, with other known immunomodulatory agents, may lead to the development of an ITI protocol for those Pompe patients on ERT who need it most.

While there has been limited success with ITI in patients treated with therapeutic proteins, an effective protocol for managing HSAT has not been found. Current ITI protocols have demonstrated success only in the naïve or early-ERT setting and there remains the challenge of early identification of patients who are at high risk for the development of HSAT and poor clinical response. While the CRIM-negative status is known to confer this susceptibility in Pompe patients, identification of the CRIM-positive patients who will go on to develop HSAT, as opposed to those who will tolerize naturally over time, requires further study. This obstacle has not allowed timely implementation of ITI protocols prior to the establishment of the entrenched immune responses in such patients. Until universal early identification of at-risk patients and subsequent early initiation of ITI can be implemented, there will be a need for ITI protocols that can combat the entrenched immune response. Identification of such a regimen may benefit other conditions marked by sustained antibody responses, such as autoimmune diseases. This case serves as an example and a reminder that no widely effective immunomodulation therapy has been established for patients who develop HSAT during ERT for Pompe disease and continued investigation is not only warranted, but also imperative to the success of ERT in this patient cohort.

Acknowledgments

The clinical trials in which this patient was enrolled were sponsored by Synpac, Inc. (Durham, NC) and Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, MA). The clinical trials were supported by Genzyme Corporation and Grant 1UL1RR024128 from the Duke Clinical Research Unit (DCRU) Program, National Center for Research Resources and the National Institutes of Health. Priya S. Kishnani and Andrea Amalfitano have received research/grant support from Genzyme Corporation. Joel Charrow is a member of the Fabry and Gaucher Disease Registry Advisory Board for Genzyme Corporation. Priya S. Kishnani is a member of the Pompe and Gaucher Disease Registry Advisory Board for Genzyme Corporation. Joel Charrow, Y-T Chen and Priya S. Kishnani and have received honoraria from Genzyme Corporation. Alglucosidase alfa rhGAA, in the form of Genzyme’s product alglucosidase alfa, (Myozyme®/Lumizyme®) has been approved by the US FDA and the European Union as therapy for Pompe disease. Duke University and the inventors of the method of treatment and precursors of the cell lines used to generate the enzyme (rhGAA) used commercially have received royalties pursuant to the university’s policy on inventions, patents, and technology transfer.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The opinions and information in this article are those of the authors, and do not represent the views and/or policies of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

This potential conflict for Duke University has been resolved through monetization. S. G. Banugaria, T. T. Patel, S. Das, J. Mackey and A. S. Rosenberg have no financial or proprietary interest in the materials presented herein.

References

- 1.Hirschhorn R, Reuser AJJ. Glycogen storage disease type II: Acid a-glucosidase (acid maltase) deficiency. In: Valle D, Scriver CR, editors. Scriver’s OMMBID the Online Metabolic & Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kishnani PS, Hwu WL, Mandel H, Nicolino M, Yong F, Corzo D. A retrospective, multinational, multicenter study on the natural history of infantile-onset Pompe disease. J Pediatr. 2006;148:671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Hout HM, Hop W, van Diggelen OP, Smeitink JA, Smit GP, Poll-The BT, Bakker HD, Loonen MC, de Klerk JB, Reuser AJ, van der Ploeg AT. The natural course of infantile Pompe’s disease: 20 original cases compared with 133 cases from the literature. Pediatrics. 2003;112:332–340. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolino M, Byrne B, Wraith JE, Leslie N, Mandel H, Freyer DR, Arnold GL, Pivnick EK, Ottinger CJ, Robinson PH, Loo JC, Smitka M, Jardine P, Tato L, Chabrol B, McCandless S, Kimura S, Mehta L, Bali D, Skrinar A, Morgan C, Rangachari L, Corzo D, Kishnani PS. Clinical outcomes after long-term treatment with alglucosidase alfa in infants and children with advanced Pompe disease. Genet Med. 2009;11:210–219. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31819d0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishnani PS, Corzo D, Leslie ND, Gruskin D, Van der Ploeg A, Clancy JP, Parini R, Morin G, Beck M, Bauer MS, Jokic M, Tsai CE, Tsai BW, Morgan C, O’Meara T, Richards S, Tsao EC, Mandel H. Early treatment with alglucosidase alpha prolongs long-term survival of infants with Pompe disease. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:329–335. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181b24e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishnani PS, Corzo D, Nicolino M, Byrne B, Mandel H, Hwu WL, Leslie N, Levine J, Spencer C, McDonald M, Li J, Dumontier J, Halberthal M, Chien YH, Hopkin R, Vijayaraghavan S, Gruskin D, Bartholomew D, van der Ploeg A, Clancy JP, Parini R, Morin G, Beck M, De la Gastine GS, Jokic M, Thurberg B, Richards S, Bali D, Davison M, Worden MA, Chen YT, Wraith JE. Recombinant human acid [alpha]-glucosidase: major clinical benefits in infantile-onset Pompe disease. Neurology. 2007;68:99–109. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251268.41188.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kishnani PS, Goldenberg PC, DeArmey SL, Heller J, Benjamin D, Young S, Bali D, Smith SA, Li JS, Mandel H, Koeberl D, Rosenberg A, Chen YT. Cross-reactive immunologic material status affects treatment outcomes in Pompe disease infants. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banugaria SG, Prater SN, Ng YK, Kobori JA, Finkel RS, Ladda RL, Chen YT, Rosenberg AS, Kishnani PS. The impact of antibodies on clinical outcomes in diseases treated with therapeutic protein: lessons learned from infantile Pompe disease. Genet Med. 2011;13:729–736. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182174703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Messinger YH, Mendelsohn NJ, Rhead W, Dimmock D, Hershkovitz E, Champion M, Jones SA, Olson R, White A, Wells C, Bali D, Case LE, Young SP, Rosenberg AS, Kishnani PS. Successful immune tolerance induction to enzyme replacement therapy in CRIM-negative infantile Pompe disease. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2012;14:135–142. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendelsohn NJ, Messinger YH, Rosenberg AS, Kishnani PS. Elimination of antibodies to recombinant enzyme in Pompe’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:194–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0806809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel M, Staller W, Buhlmeyer K. Left ventricular myocardial mass determined by cross-sectional echocardiography in normal newborns, infants, and children. Pediatr Cardiol. 1991;12:143–149. doi: 10.1007/BF02238520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darrah J, Piper M, Watt MJ. Assessment of gross motor skills of at-risk infants: predictive validity of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:485–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb15399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piper MC, Darrah J. Motor Assessment of the Developing Infant. W. B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amalfitano A, Bengur AR, Morse RP, Majure JM, Case LE, Veerling DL, Mackey J, Kishnani P, Smith W, McVie-Wylie A, Sullivan JA, Hoganson GE, Phillips JA, III, Schaefer GB, Charrow J, Ware RE, Bossen EH, Chen YT. Recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase enzyme therapy for infantile glycogen storage disease type II: results of a phase I/II clinical trial. Genet Med. 2001;3:132–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Zettervall O. Induction of split tolerance and clinical cure in high-responding hemophiliacs with factor IX antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:9169–9173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.9169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson IM, Berntorp E, Zettervall O. Induction of immune tolerance in patients with hemophilia and antibodies to factor VIII by combined treatment with intravenous IgG, cyclophosphamide, and factor VIII. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:947–950. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804143181503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brady RO, Murray GJ, Oliver KL, Leitman SF, Sneller MC, Fleisher TA, Barton NW. Management of neutralizing antibody to Ceredase in a patient with type 3 Gaucher disease. Pediatrics. 1997;100:E11. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funk B, Kessler U, Eisenmenger W, Hansmann A, Kolb HJ, Kiess W. Expression of the insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose-6-phosphate receptor in multiple human tissues during fetal life and early infancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:424–431. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.2.1379254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wenk J, Hille A, von Figura K. Quantitation of Mr 46000 and Mr 300000 mannose 6-phosphate receptors in human cells and tissues. Biochem Int. 1991;23:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McVie-Wylie AJ, Lee KL, Qiu H, Jin X, Do H, Gotschall R, Thurberg BL, Rogers C, Raben N, O’Callaghan M, Canfield W, Andrews L, McPherson JM, Mattaliano RJ. Biochemical and pharmacological characterization of different recombinant acid alpha-glucosidase preparations evaluated for the treatment of Pompe disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph A, Munroe K, Housman M, Garman R, Richards S. Immune tolerance induction to enzyme-replacement therapy by co-administration of short-term, low-dose methotrexate in a murine Pompe disease model. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152:138–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunley TE, Corzo D, Dudek M, Kishnani P, Amalfitano A, Chen YT, Richards SM, Phillips JA, III, Fogo AB, Tiller GE. Nephrotic syndrome complicating alpha-glucosidase replacement therapy for Pompe disease. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e532–e535. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0988-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banati M, Hosszu Z, Trauninger A, Szereday L, Illes Z. Enzyme replacement therapy induces T-cell responses in late-onset Pompe disease. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:720–726. doi: 10.1002/mus.22136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]