Highlights

-

•

New procedure to test endowment effect in lottery settings.

-

•

Procedure controls for transaction costs and inspection effects.

-

•

Successful prediction of the endowment effect in a hypothetical setting.

-

•

Successful prediction for self and for others.

-

•

Identification of regret as probable source of endowment effects in lottery settings.

Keywords: Endowment effect, Ownership, Prediction, Regret, Simulation

Abstract

The endowment effect is the finding that possession of an item adds to its value. We introduce a new procedure for testing this effect: participants are divided into two groups. Possession group participants inspect a numbered lottery ticket and know it is theirs, while inspection group participants only inspect a lottery ticket without being endowed with it. Subsequently participants choose between playing the lottery with this (possessed or inspected) ticket, or exchanging it for another one. Our procedure tests for the effect of endowment while controlling for the influence of transaction costs as well as for inspection effects and the influence of bargaining roles (buyer vs. seller), which often afflict experimentation with the endowment effect. In a real setting, tickets in possession were valued significantly higher than inspected tickets. Contrary to some findings in the literature participants also correctly predicted these valuation differences in a hypothetical situation, both for themselves as well as for others. Furthermore, our results suggest that regret rather than loss aversion may be the source of the endowment effect in an experimental setting using lottery tickets. Applying our procedure to a setting employing riskless objects in form of mugs revealed rather ambiguous results, thus emphasizing that the role of regret might be less prominent in non-lottery settings.

1. Introduction

An endowment effect exists if the subjective value of an item is higher when it is owned than when it is not owned (Thaler, 1980). This phenomenon has frequently been found in bargaining contexts with items like coffee mugs, pens, or lottery tickets (e.g., Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1990; Knetsch, 1989; Ortona & Scacciati, 1992; Van Dijk & Van Knippenberg, 1996, 1998). For instance, Kahneman et al. (1990) reported that the average of buyers’ maximum willingness to pay (WTP) for a mug was about half of the average price that sellers (i.e., owners) were willing to accept (willingness to accept; WTA) as minimal price for selling the mug.

The standard economic explanation for this difference is based on two features of prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), namely reference dependency and loss aversion. Reference dependency means that the subjective value of an item depends on the current reference point of the decision maker. From the reference point of a seller, who by necessity owns the item, the transaction is framed as a loss. In contrast, from the reference point of a buyer, who attempts to get the item, the transaction is perceived as a gain. Since losses have a greater psychological impact than gains of the same magnitude (loss aversion; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Kahneman & Tversky, 1984; Thaler, 1980, 1985), sellers accept losing an item only for a higher price than buyers are willing to pay in order to get it. Subsequent research has shown that this WTA–WTP disparity may be more likely caused by both, loss aversion of the item in the case of being a seller and loss aversion of money in the case of being a buyer (Bateman, Kahneman, Munro, Starmer, & Sugden, 2005).

Recent research on the endowment effect offers alternative explanations to loss aversion. For instance, people may value things they own, because they typically have chosen them beforehand. Thus they follow a heuristic: if I have chosen something, it must be valuable (Brehm, 1956). Another line of research argues that chosen items are associated with the self (e.g., Gawronski, Bodenhausen, & Becker, 2007), and that people tend to value things more that are associated with the self (Beggan, 1992; Beggan & Scott, 1997). Finally, since we typically do only sell things that we own, and buy things that we do not own, ownership and bargaining role are often confounded in buyer–seller-tasks. In an experiment unconfounding ownership and bargaining role, Morewedge, Shu, Gilbert, and Wilson (2009) found that the effect disappeared when buyers were owners and sellers were no owners. For instance, buyers were willing to pay just as much for a coffee mug as sellers demanded, if the buyers already owned an identical mug. The authors suggest that ownership rather than loss aversion causes the endowment effect in the standard buyer–seller paradigm.

1.1. Endowment effects in lottery settings

In order to exclude these alternative explanations and to avoid the bargaining role-ownership confounding, research procedures have been developed where participants are endowed with an item and subsequently offered the possibility to exchange it for another (not owned) item (e.g., Bar-Hillel & Neter, 1996; Knetsch, 1989; Van Dijk & Van Knippenberg, 1998). For instance, Bar-Hillel and Neter (1996) handed out lottery tickets to participants who could either keep the initial ticket or exchange it for another one. People showed a reluctance to trade their ticket, indicating a higher value of the ticket they had originally been endowed with. However, this line of research faces a problem: prospect theory in neither the original version (first generation; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979), nor the second generation cumulative version (e.g. Luce & Fishburn, 1991; Starmer & Sugden, 1989; Tversky & Kahneman, 1992; Wakker & Tversky, 1993) does allow for an uncertain reference point. Thus, these versions of prospect theory cannot be applied to predict an endowment effect in a lottery setting. Only the recent third generation prospect theory (Schmidt, Starmer, & Sugden, 2008) retains the basic features of previous variants (loss aversion, diminishing sensitivity, non-linear probability weighting) while allowing for uncertain reference points. Third-generation prospect theory indeed predicts an endowment effect even for exchanging endowed lottery tickets for other – not endowed – tickets.

Nevertheless, it stays controversial, whether the phenomenon of an endowment effect in lottery settings is entirely due to loss aversion. The reluctance to exchange a lottery ticket might also follow from anticipated regret: imagining that an exchanged ticket might win may induce regret (e.g., Bar-Hillel & Neter, 1996). Regret is experienced after realizing that the current status would have been better, if one had decided differently in a particular situation (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). Regret theories in economics (Bell, 1982; Loomes & Sugden, 1982; Sage & White, 1983) rest on two fundamental assumptions: (i) People experience emotions after learning about the outcome of a decision. Regret follows when a different choice would have led to a more desirable outcome; rejoicing follows when one finds out that a decision has resulted in the best outcome. (ii) When making decisions under uncertainty, people try to anticipate the emotions associated with different outcomes and choose options that minimize anticipated regret or maximize anticipated rejoicing.

Psychological research adds to this basic relationship, as it has been shown that the anticipation of regret does not only depend on the outcome itself, but also on how the outcome came about (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007). For instance, Gilovich and Medvec (1995), among others, report that actions produce more regret than inactions. Similarly, in an experiment by Kahneman and Tversky (1982) participants indicated that an active investor in the stock market would feel more regret than a passive holder, even when they both lost the same amount of money. In addition, Inman and Zeelenberg (2002) report that in the case of a negative outcome a consumer’s decision to switch from one product to another generally produces more regret than the decision to make a repeat purchase. Zeelenberg, Van den Bos, Van Dijk, and Pieters (2002) provide further evidence that regret depends on what behavior is perceived as the “normal” behavior in the situation at hand.

Anticipated regret is an alternative to loss aversion as an explanation for the reluctance to trade an endowed lottery ticket for another ticket: imagining that the exchanged ticket might win leads to regret, and anticipating this regret leads to a reluctance to exchange tickets. Examination of the endowment effect within a lottery setting has the advantage of avoiding the confounding of ownership and bargaining role, but the experimental lottery procedure also implicates some problems. Plott and Zeiler (2005, 2007) argue convincingly that there is no consensus on whether the literature supports the interpretation that WTA–WTP disparities in different contexts are due to an endowment effect. They offer evidence that support the notion that these findings may actually be based on incorrect interpretations of experimental results. Despite empirical evidence that WTA–WTP disparities are observable even when controlling for experimental misconceptions in lottery settings (Isoni, Loomes, & Sugden, 2011), some of their arguments remain challenging the standard lottery procedure. These arguments are: (i) Transaction costs fail to be constant. Plott and Zeiler (2007, p.1455) state: “Specifically, if a subject is indifferent between the endowed good and the alternative good, even very slight transaction costs (e.g., requiring a subject to raise his hand if he wishes to trade or to take any sort of action to initiate a trade such as the physical exchange of the endowment for the alternate good) might encourage him to keep the good within reach.” According to Plott and Smith (1978) slight transaction costs can have a big influence on choices when subjects are indifferent between options (see also Chapman, 1998). Thus, exchanging an endowed lottery ticket for another one needs action which is more costly than remaining inactive and staying with the original ticket. In case that someone is indifferent between the two tickets this small additional cost can make the big difference such that people keep their original ticket if only to prevent any additional costs associated with switching tickets. Another argument by Plott and Zeiler (2007) is (ii) Inspection as a source of information. “The ability to thoroughly inspect a good in one’s possession can be a source of information about its properties that leads to an adjustment in valuation” (p. 1451). Accordingly, reluctance to trade might be due to additional information gleaned from use rather than from possession proper. In sum, experimental evidence showing reluctance to trade an endowed lottery ticket for another one cannot unambiguously be interpreted as being due to endowment.

1.2. Predicting endowment effects

Are people able to correctly predict the endowment effect in a hypothetical setting? Given that using hypothetical inputs is standard procedure in research on judgment and decision making (Kühberger, Schulte-Mecklenbeck, & Perner, 2002), it seems safe to assume that the endowment effect will also exist in hypothetical settings. However, Loewenstein and Adler (1995) report that people failed to predict it for the valuation of a coffee mug. In their study, people not in possession of a mug failed to accurately predict how much they would value the mug if they actually were to own it. Subsequent studies (Van Boven, Dunning, & Loewenstein, 2000; Van Boven, Loewenstein, & Dunning, 2003) added to this by showing that selling prices were underestimated by buyers whereas buying prices were overestimated by sellers. Van Boven, Dunning, and Loewenstein (2000), Van Boven et al. (2003) proposed to consider this an intrapersonal empathy gap. This gap exists when predictions of own behavior are biased because the predictor is in a different psychological state (i.e., mis-predicting one’s own selling price while actually being a buyer; mis-predicting one’s own buying price while actually being a seller). In addition, they say, there are interpersonal empathy gaps, which exist when predictions for others are biased (i.e., I am a buyer, and the other person is a seller). They argue that people are subject to both types of empathy gaps, and they thus underestimate the impact of the endowment effect on their own, as well as on other people’s preferences. On this reasoning the endowment effect fails to be correctly predicted when there is no correspondence in bargaining roles. It follows that, if there is such a correspondence, or if the situation does not call for bargaining roles at all, prediction should be possible.

1.3. Aim of the present research

The present paper builds on the evidence discussed above in the following way: in Experiment 1 we test the endowment effect with a new procedure using lotteries: our new procedure controls for transaction costs by keeping costs for exchanging and keeping tickets absolutely equal. Second, our procedure enables a test of the informational value of endowment. Recall that it is possible that the reluctance to trade a ticket is not caused by proper ownership, but rather by learning that an inspected ticket is not deficient, or by a stronger identification with the number of a ticket after having been endowed.

In Experiment 2 we apply our procedure to a hypothetical context to test whether or not people are able to predict an endowment effect correctly for themselves as well as for others. The reasons for investigating hypothetical effects are: (i) Reports in the literature on the predictability of the endowment effect are inconclusive, and replicability is an unresolved issue within a lottery setting. (ii) The failure to predict other people’s choices in the case of the endowment effect is an argument against the theory of mental simulation in an ongoing debate in the field of social cognition (e.g., Kühberger & Bazinger, 2013; Stich & Nichols, 1995). (iii) The successful prediction of endowment effects in a hypothetical setting is a necessary precondition for Experiment 3, where we test whether anticipated regret instead of loss aversion is the likely source of the endowment effect. Although there are studies investigating a relation between endowment effects and regret (e.g., Bar-Hillel & Neter, 1996; Martinez, Zeelenberg, & Rijsman, 2011; Van De Ven & Zeelenberg, 2011), the empirical evidence showing that regret is the crucial factor in explaining endowment effects in lottery settings still is weak: some of these studies relate to a buyer–seller context (e.g., Martinez et al., 2011), others do not control for transaction costs, or show inconclusive results (Bar-Hillel & Neter, 1996). An interesting study induced regret by manipulating feedback (Van De Ven & Zeelenberg, 2011). This study reported an effect of regret on the reluctance to trade a ticket, but used a procedure that is not easily comparable to other studies: it offered an additional reward for giving up the original ticket. Finally, in Experiment 4 we replicate Experiment 1 by using coffee mugs instead of lottery tickets, in order to test if our findings are also valid beyond the lottery setting.

2. Experiment 1

In Experiment 1 we arranged for a real lottery where people were asked to participate. The crucial manipulation was about how participants were presented the tickets: either by being directly endowed with a ticket (possession condition), or by being offered the opportunity to inspect a ticket (inspection condition). People then indicated whether they preferred to participate with the endowed (inspected) ticket, or another one. Thus, there was no bargaining situation, and both conditions were identical with respect to information about the tickets.

2.1. Participants

Forty undergraduates of Psychology from two introductory statistics courses at the University of Salzburg (25 females, 15 males; mean age 23.4 years) participated voluntarily.

2.2. Design and procedure

Subjects were invited to participate in a lottery awarding a prize of €25 to one of 40 tickets and were informed that the chance of winning was exactly the same for each of the 40 available tickets. People were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, possession or inspection.

Possession group participants were shown two numbered, but otherwise identical, tickets lying on a table right in front of them. They were informed that the numbers from 1 to 40 printed on the tickets were used to identify the winning ticket in a lottery which was scheduled for the next week1. Then one of the two tickets was given to them and they were told that this ticket was theirs (“You now possess this ticket and you can have a close look at it.”). After this endowment procedure participants had to put their ticket back to the table, just next to the other ticket. Then they were given a choice. They were asked to choose the ticket they actually wanted to play the lottery with: the ticket in their possession or the other (identical) ticket.

After choosing the ticket to play the lottery with, participants’ valuation of this ticket was measured by giving them a short list of prices ranging from €0.50 up to €10 in intervals of ¢50. For each price participants had to indicate whether they would exchange their chosen ticket and switch to the other ticket if they were paid the respective amount. This measures the value of the chosen ticket in comparison with the other ticket. Participants were informed that at the end of the experiment, for two randomly selected people one of the listed prices would be drawn and enacted. Depending on their response concerning this price they either had to play the lottery with the chosen ticket, or received the respective amount of money and had to play with the other, non-chosen ticket. This well-established price elicitation method (e.g. Chapman, 1998) determines the smallest amount of money necessary to make a participant switch from the chosen ticket to the other ticket. This measure is conceptually similar to the classic willingness-to-accept-measures. After completing the pricelist, participants were debriefed and asked to bring along their ticket to the lottery 1 week later.

The procedure in the inspection group was identical to the possession group, with the exception that participants were handed out one of the tickets in order to inspect it (without being endowed). So again, two numbered tickets were lying on the table and the experimenter handed them one of those (“This ticket is an example of the tickets for playing the lottery. You can have a close look at it.”). Afterwards participants had to return the inspected ticket to the table next to the other ticket, and were asked to choose the ticket they wanted to play the lottery with.

This procedure is new in research on endowment effects and offers some notable advantages. First, transaction costs are identical across groups: in any group participants have to return the ticket (endowed, or inspected), and then select one of the two tickets from the table. Second, the establishment of an inspection group allows the independent analysis of both possession, and inspection of a ticket, as potential determinants of the reluctance to trade. This procedure equates for information values by rendering the inspection condition as informative as the endowment condition. Finally, the setting does not create a market situation, since there are no buyers or sellers, and thus there is no confounding of ownership and bargaining role as in many other experiments.

2.3. Results and discussion

Two sorts of data were collected in Experiment 1: chosen ticket (possessed/inspected vs. other), and amount of money required for switching (WTP).

2.3.1. Choices

Inspection group participants were indifferent between tickets: 9 of 20 participants (45%) chose the initial (inspected) ticket, while the rest (55%) decided for the other ticket. This is not significantly different from the even split (χ2(1) = 0.20; n.s.). In contrast, the vast majority of possession group participants kept their initial ticket (17 out of 20; 85%), and only 3 people (15%) decided to exchange it (χ2(1) = 9.80; p < .01; φ = .70). This difference between conditions turned out to be highly significant (χ2(1) = 7.03; p < .01; φ = .42).

2.3.2. Prices

Our procedure distinguishes between two types of decision makers: non-switchers, who stay with their initial ticket (possessed, or inspected) and switchers, who part with it and opt for the other ticket. For both groups we measured the minimal amount of money required for giving away the initial ticket and taking the other one instead. For non-switchers this WTA price is positive, because they value their initial ticket higher than the other ticket. For switchers, this WTA is negative since they value their initial ticket less than the other one. In the inspection group the mean WTA for switching was € + 0.30 (i.e., the inspected ticket was valued approximately equal to the other ticket; not significantly different from €0 (t(19) = 0.23; n.s.), compared to a mean WTA of € + 4.90 in the possession group (i.e., people valued the endowed ticket about €5 higher than the other ticket; significantly higher than €0; t(19) = 4.45; p < .001; r = .71). The difference between the two groups was also highly significant (t(38) = 2.71; p = .01; r = .40). To make sure that the different valuations in the possession condition compared to the inspection condition are not an artifact due to middle-of-scale answers in combination with the frequencies of switching/not switching in the two conditions we had a closer look at the valuation data in the two groups: the 17 participants who were endowed with a ticket and decided to keep it indicated WTA prices between ¢50 and €10 for exchanging their chosen ticket. Indeed, 7 participants indicated the highest possible WTA of €10, followed by others demanding €9 and €8.50, respectively. In contrast, the three switchers in the possession group indicated that payments of €5, €2, and €1 would make them switch to play the lottery with the non-chosen ticket. In the inspection group the 9 participants who kept their inspected ticket demanded WTA prices that were similar to the switchers’ prices (price range from €0 to €10, and ¢50 to €10 respectively; 2 participants demanded €10, and 3 participants €1 in each group). Thus, keepers and switchers showed similar distributions of WTA prices in the inspection condition, while these distributions were clearly different in the endowment condition. These data show that what we observed is a real difference in valuation between the possession and the inspection group rather than an artifact.2

In sum, we found a strong reluctance to exchange a lottery ticket that one owns for an equivalent ticket that one does not own. No such reluctance was found in a comparable condition that only differed by a lack of ownership. Since transaction costs and informational value did not differ between conditions, it follows that endowment is the relevant feature leading to reluctance to exchange an endowed lottery ticket. Note that effects of choosing and of bolstering self-esteem due to ownership are also unlikely here, since the endowed ticket was not chosen in the first place, and owning this ticket does not imply anything about the self.

Loss aversion might be the crucial factor in explaining the endowment effect in our lottery setting. As discussed in the introduction, third generation prospect theory (Schmidt et al., 2008) allows the reference point to be a lottery. In the possession condition the reference point is the ticket a person is endowed with, and the question of switching is answered by comparing a loss of €25 (switch and the endowed ticket wins) with a gain of €25 (switch and other ticket wins). For the other 38 cases there will not be any difference because neither ticket wins, when owning the endowed ticket is the reference act. Since losses loom larger than gains, subjects will keep the endowed ticket since a forgone gain of €25 is not as bad as a realized loss of €25. In the inspection condition there is no reference point and thus individuals should be indifferent between tickets.

The loss aversion explanation is a bit problematic for the valuation task results, however. In the valuation task, the reference act is clear: it is the ticket that has been chosen, in both the endowment and the inspection group. Therefore, people in both groups should demand similar amounts of money to switch from the chosen ticket to the other one. This is inconsistent with our finding of a higher price for switching in the possession group in comparison to the inspection group.

Considering regret as an alternative explanation for the reluctance to exchange an endowed ticket, classical regret theory (Loomes & Sugden, 1982) does not directly account for the observed differences. Since all lottery tickets have the same probability of winning the same amount of €25, regret as a consequence of choosing a blank when the other ticket wins, is identical for the possession and inspection condition. However, psychological research on regret has found evidence that regret is higher when a negative outcome was preceded by “norm-deviant” behavior compared to standard behavior (Zeelenberg et al., 2002), and is said to be especially strong if a previously owned lottery ticket wins (Bar-Hillel & Neter, 1996). So this psychologically enriched notion of regret – slightly different to regret theory in economics – could explain the pattern of results observed in Experiment 1. We will further investigate this issue in Experiment 3, but since the finding of an endowment effect in a hypothetical setting is a necessary precondition for this experiment, Experiment 2 aims at replicating the outcome of Experiment 1 in a hypothetical setting.

3. Experiment 2

Our first experiment shows that believing that one owns a lottery ticket adds to its value. The interesting question is whether holding a hypothetical belief (i.e., only imagining that one owns a ticket) has the same consequences as a real belief (i.e., knowing that one owns a ticket). Experiment 2 was designed to investigate whether the endowment effect can also be predicted hypothetically. In order to do this, participants were given a detailed description of either the possession group or the inspection group procedure of Experiment 1, and were then asked to imagine being in exactly the same situation. Subsequently, they had to predict which ticket a participant would choose. Van Boven et al. (2000), Van Boven et al. (2003) report an intrapersonal empathy gap (failure in self-prediction) and an interpersonal empathy gap (failure in predicting the effect for others) in bargaining endowment tasks. The purpose of Experiment 2 was to test whether correct prediction is also impossible in our task, which is without different bargaining roles. Thus, lack of correspondence between bargaining roles does not apply. Indeed, there is ample evidence that entertaining a belief hypothetically often results in similar effects as the real belief (for a discussion of doing hypothetical experiments, see Hertwig & Ortmann, 2001; Kühberger, 2001). Otherwise, hypothetical choices would always suffer from misprediction. According to Perner and Kühberger (2006) the effects of mental states like beliefs can be predicted correctly. Thus, imagining a situation should result in the same effect as being in a corresponding real situation.

3.1. Participants

One hundred and twenty-five undergraduate students from introductory statistics courses in Psychology at the University of Salzburg (110 females, 15 males; mean age = 22.7 years) agreed to participate voluntarily. We sampled from the same population as in Experiment 1, but avoided repeated recruitment.

3.2. Design and procedure

Experiment 2 used hypothetical outcomes, since there was no real lottery taking place and participants could not win in reality. Participants were instructed to imagine participation in one of the two conditions of Experiment 1.

We used a full factorial 2 × 2 design with the between subject factors endowment condition (possession vs. inspection) and target of prediction (self vs. other). Thus, participants had to predict for themselves whether they would choose a possessed (group 1), or inspected (group 2) hypothetical ticket, or would switch to the other ticket. The remaining two groups had to predict whether some other person would keep a possessed (group 3), or inspected (group 4) ticket, or would prefer the alternative ticket.

In principle there is no difference between self and other predictions in this setting: when predicting, you imagine being in a situation different from the actual situation and feed the relevant features into your decision making system. Thereby a preference is established, which is your own preference (in the case of self-prediction), or is attributed to another person (in the case of prediction for others). A difference between self and other in this process only exists to the degree that the relevant features of the situation also include additional knowledge about the other person. Since the other person is left unspecified there are no such features available. Thus, we expect no difference between the self and other conditions.

As in Experiment 1, participants in all four groups additionally had to state the amount of money they, or others, were expected to accept for giving up the chosen ticket in order to switch to the other one.

3.3. Results and discussion

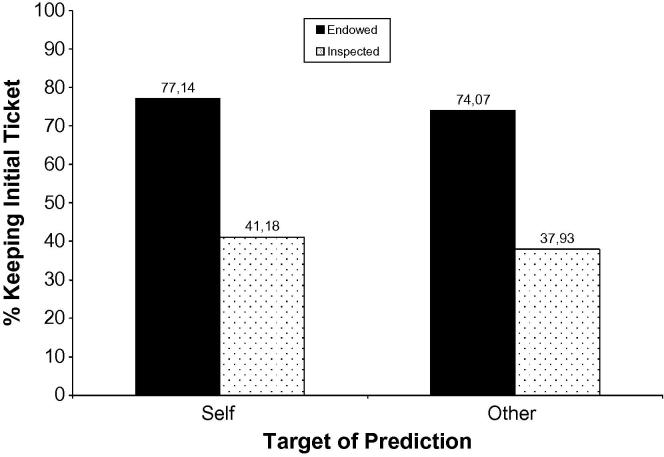

Fig. 1 shows the percentage of participants predicting that the initial ticket would be preferred in any of the four experimental groups.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of preferring initial ticket in different hypothetical situations.

For conducting an ANOVA non-switching predictions were coded as 0 (preference of initial ticket), and switching predictions as 1 (preference for other ticket). We found a main effect for condition (possession vs. inspection; F(1, 121) = 18.39; p < .001; η2 = .13), no significant difference for target of prediction (self vs. other; F(1, 121) = 0.14; n.s.), and no interaction (F(1, 121) = 0.00; n.s.). Looking at self-predictions in the possession condition, it turned out that 77% of the participants predicted that they would prefere the initial ticket compared to 41% in the inspection group. When predicting for another person, the results showed a similar pattern (74% preferring the initial ticket in possession vs. 38% in the inspection group).

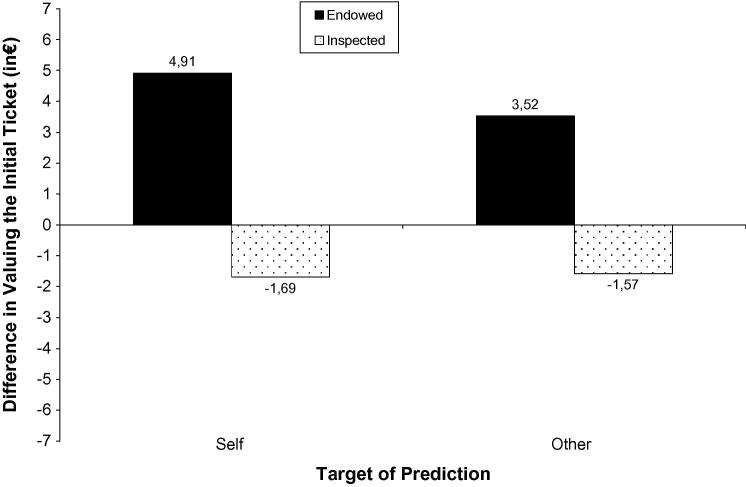

Fig. 2 shows the means of the WTA-prices. Again, positive values indicate that the initial ticket was valued higher than the other ticket, and negative values indicate the reverse. An ANOVA showed a significant main effect for condition (F(1, 121) = 27.32; p < .001, η2 = .18), but no difference for target of prediction (F(1, 121) = 0.32; n.s.), and no interaction (F(1, 121) = 0.46; n.s.).

Fig. 2.

Mean prices indicated for accepting the other ticket in different hypothetical situations.

When predicting for oneself, possessed tickets were predicted to be valued about €4.90 higher on average than the other ticket. This differs significantly from 0 (t(34) = 5.03; p < .001; r = .65). In contrast, inspected tickets were predicted to be valued €1.70 lower than the other ticket in the self-prediction condition (t(33) = −1.47; n.s.). A direct comparison of the self-prediction condition of Experiment 2 and Experiment 1 via an analysis of variance with experiment as one factor and condition (possession vs. inspection) as a second factor only revealed a main effect for condition (F(1, 105) = 22.47; p < .001; η2 = .18), but no main effect for experiment (F(1, 105) = 0.70; n.s.) nor an interaction (F(1, 105) = 0.72; n.s.), thus confirming the similarity of the results of these two experiments. A similar pattern was found for predicting another person: possessed tickets were predicted to be valued about €3.50 higher than the other ticket (significantly different from 0; t(26) = 2.86; p < .01; r = .49), inspected tickets were predicted to be valued €1.60 lower than the other ticket, which again did not differ significantly from 0 (t(28) = −1.42; n.s.).

To back up the interpretation of the valuation results as an indicator for higher valuation of the endowed ticket compared to the inspected ticket we decided for a more rigorous test3: we compared the 27 participants who preferred the endowed ticket in the possession group with the 14 participants who preferred the initial ticket in the inspection group. For self-predictions we found a significant difference in ticket prices (possession group mean = €7.52; inspection group mean = €4.79; t(39) = 2.38; p < .05; r = .36). A similar pattern was found in the other-prediction conditions, where the 20 participants who kept the endowed ticket valuated this ticket higher than the 11 participants in the inspection group (possession group = €6.90; inspection group = €5.09; t(29) = 1.79; p = .08; r = .32). These results were also confirmed by non-parametrical analyses controlling for bias in the underlying distributions (self-prediction U = 114.00, p < .05; other-prediction U = 69.00, p = .09).

In sum, the results of Experiment 2 show that the endowment effect can be predicted correctly for oneself as well as for other people in a hypothetical setting. The comparison of the valuation of lottery tickets in Experiment 1 (real) and Experiment 2 (hypothetical) reveals a striking similarity in the size of the effects: the effect size for choices in the real Experiment 1 was φ = .40, thus explaining 16% of the variance; the effect size in the hypothetical Experiment 2 was η2 = .13, which corresponds to an explained variance of 13%. Similarly, in Experiment 1, the endowed tickets were valued €4.90 higher than the other tickets, which is nearly identical to the hypothetical Experiment 2, where endowed tickets (in the self-prediction condition) were predicted to be valued €4.91 higher than the other tickets. In addition, participants predicted the endowment effect not only for themselves, but also for other people. This pattern of findings suggests that simply imagining possession of a ticket may have the same consequences on valuation as actual possession. By implication, it is in all likelihood the difference in bargaining roles that prevents participants from correctly predicting the endowment effect in bargaining settings.

The first two experiments showed an endowment effect that can also be predicted correctly. However, as pointed out before, loss aversion can only partly account for these findings. The psychologically enriched conception of regret might be a driving force behind this phenomenon. Experiment 3 was designed to directly test the idea that anticipated regret plays a prominent role in the present experimental setting.

4. Experiment 3

Anticipated regret is an emotion that comes into play if one mentally imagines suboptimal outcomes. In our task, anticipated regret could originate from comparing consequences of the selected and the unselected action (i.e., switching vs. not switching). If I select a ticket and imagine that the other ticket wins, I will experience regret (Miller & Taylor, 1995; Zeelenberg, Van Dijk, Manstead, & Van der Pligt, 2000). As explained before, classical regret theory (Loomes & Sugden, 1982) predicts regret to be constant in all possible cases, regardless of whether the ticket is possessed or inspected, or if it was exchanged or not: there is only one alternative, and this is the same in all situations. Thus, regret is identical.

Research addressing the psychological sources of regret has shown that things are more complicated (e.g., Gilovich & Medvec, 1995; Zeelenberg et al., 2002). Specifically, we suggest that there is stronger anticipated regret in the condition where someone is endowed with a lottery ticket, imagines exchanging this ticket for the other one, and imagines that the original ticket wins, compared to all other cases (i.e., preferring the endowed ticket and the other available ticket wins; preferring the inspected ticket and the other ticket wins; preferring the other ticket and the inspected ticket wins). The basic idea is that acting away from a reference point (i.e., exchanging a possessed ticket) is a strong source of regret, if the action turns out negatively (Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2007; Zeelenberg et al., 2002). Thus, regret in our task is an emotion which depends on both, the action and the anticipated outcome. It is produced in imagination and therefore should be easily re-lived in a hypothetical task. In Experiment 2 we found an endowment effect with lottery tickets in our hypothetical task. Building on that, we designed Experiment 3 where participants were asked to imagine having preferred one of the tickets sketched above and confronting a negative outcome afterwards. Subsequently, we registered their anticipated level of regret.

4.1. Participants

Two hundred and thirty-nine undergraduates from an introductory course of Psychology at the University of Salzburg (195 females, 44 males; mean age = 22.3 years) participated voluntarily.

4.2. Design and procedure

Participants were introduced to the situation of Experiment 1 and were instructed to imagine participation. They were assigned to one of four groups crossing condition (possession vs. inspection) and action (switching vs. not switching). Participants of the first group had to imagine being in possession of a ticket, and having decided to keep it for playing the lottery (possession/not switching); group 2 participants had to imagine being in possession of the initial ticket and having switched to the other ticket (possession/switching); participants of group 3 had to imagine having inspected the initial ticket and having kept it (inspection/not switching); group 4 participants were to imagine inspection and switching (inspection/switching). Then participants were told that the ticket they finally chose failed to win, but instead the rejected ticket was drawn. Subsequently they were asked to predict their regret on a 10-point scale (1 = would not feel any regret at all, 10 = would feel very strong regret). This question specifically refers to their action (switching/not switching) and entails a comparison between the consequences of an action and a failure to act. If our effect is due to regret, participants in the switching conditions should report higher regret than participants in the non-switching condition, but only when they were in possession of the initial ticket.

As a control question, participants had to indicate how negative they would feel about losing in their respective situation, again on a 10-point scale (1 = would not feel bad at all, 10 = would feel very bad). This question does not refer to the action, but rather to the outcome, and since the negative outcome is the same in all four cases, we expected no difference regarding these answers. The order of presentation of the two questions was counterbalanced over all conditions.

4.3. Results and discussion

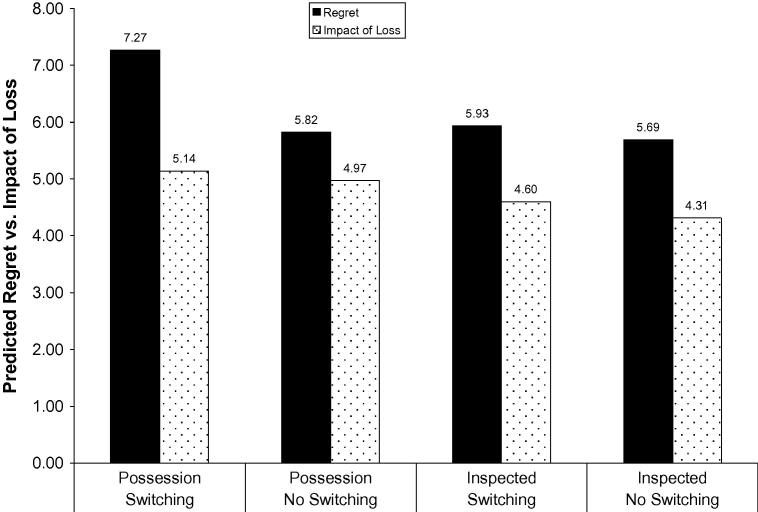

The results are depicted in Fig. 3. A 2 (ownership) × 2 (action) × 2 (question) ANOVA revealed a significant influence of ownership (F(1, 235) = 4.58; p < .05, η2 = .02) and of question (F(1, 235) = 96.57; p < .001, η2 = .29), but not of action (F(1, 235) = 2.98; n.s.). Anticipated regret in general was higher than the negative impact of loss (with means of 6.18 and 4.75, respectively). The crucial result showing the role of regret is the significant three-way interaction between ownership, action, and question (F(1, 235) = 5.23; p < .05, η2 = .02). Inspection of Fig. 3 shows that this interaction is due to one of the eight cells: imagining losing in the possession condition after having switched. Note that it was not switching per se that led to the anticipation of stronger regret (no main effect of switching/not switching), but only switching in connection with possession of a ticket. This pattern shows that regret is a source of the endowment effect, which, at least for this type of experiment, might be more appropriate than loss aversion.

Fig. 3.

Predictions of regret and impact of loss for all conditions of Experiment 3.

Experiments 1–3 use lottery tickets. Lotteries are a specific case, theoretically, as well as empirically. Experiment 4 was designed to test our basic procedure with riskless objects.

5. Experiment 4

Experiment 4 tests the possession–inspection difference with riskless items, namely coffee mugs. Again we expect that people will prefer mugs in possession, but will not have a preference for inspected mugs.

5.1. Participants

Forty undergraduates students from the University of Vienna (26 females, 14 males; mean age 23.5 years) participated voluntarily. We excluded students of psychology to make sure that participants did not have any background knowledge about endowment effects.

5.2. Design and procedure

Subjects were invited to participate in an experiment where they had to answer a few questions unrelated to the present study. They were told that they would get a coffee mug as remuneration for participation and were randomly assigned to either the possession or the inspection condition.

Possession group participants were shown two identical blue coffee mugs that were put on a table right in front of them and they were informed that they would get one of these mugs. Subsequently they were endowed with one of the two mugs (“This mug now belongs to you and you can have a close look at it.”). Afterwards participants had to put their mug back on the table, just beside the other mug and were offered to choose which mug they wanted to take home: the mug they were endowed with or the other (identical) mug. Again we measured participants’ valuation of their mugs by collecting WTA prices (minimum amount of money to give up chosen mug and switch to the other one instead). Participants were informed that for some randomly selected participants (same probabilities as in Experiment 1) one of the listed prices would be drawn and enacted.

The procedure in the inspection group was identical to the possession group, with the exception that participants were handed one of the two mugs to inspect it (“This is an example of the mugs you will get for participation. You can have a close look at it.”). Then they had to return the mug and were asked to choose the mug that they preferred to take home.

5.3. Results and discussion

5.3.1. Choices

Similar to Experiment 1, inspection group participants were indifferent between the two mugs: 8 of 20 participants (40%) chose the initial (inspected) mug, while the others (60%) opted for the alternative mug. This is not significantly different from the even split (χ2(1) = 0.80; n.s.). In the possession group the clear majority preferred the initial (possessed) mug (17 out of 20; 85%), whereas only 3 people (15%) opted for exchanging it (χ2(1) = 9.80; p < .01; φ = .70). The difference found between conditions is highly significant (χ2(1) = 8.64; p < .01; φ = .46).

5.3.2. Prices

In both conditions people staying with their initial mug stated a higher WTA for exchanging it (possession/not switching = €3.85; inspection/not switching = €3.31) than participants who decided to switch mugs (possession/switching = €0.83; inspection/switching = €2.04). The critical test between the valuations of participants staying with the initial mug in the possession and the inspection treatments did not reveal a significant difference (t(23) = 0.37; n.s.). Due to the small sample size we decided to have a closer look at the distributions of prices in the respective groups, but there were no obvious differences.

In sum, we replicated the endowment effect for choices of mugs: our participants were reluctant to exchange a possessed mug, but not with regard to an inspected mug. The valuation measure did not show a difference between possession and inspection groups: when offered money for switching to the other mug, participants in both groups indicated similar WTA prices.

The results in the choice task show that possessing an item makes people stick to it, but in this case it does not mean that they also ask for a higher price in order to exchange it. Hence, we obtain another interesting finding revealing that choice and evaluation can sometimes lead to different results.

6. General discussion

We conducted four experiments on the endowment effect. Using a non-bargaining paradigm we were able to show that this effect exists for real lottery tickets (Experiment 1) and can also be predicted hypothetically (Experiment 2). Anticipated regret rather than loss aversion was identified as the main factor responsible for these findings (Experiment 3). An additional experiment replicated an endowment effect for coffee mugs, but – in contrast to the lottery setting – did not reveal a difference in WTA measures between the possession and the inspection condition.

Our new procedure to study the endowment effect has some advantages: first, choice options in the endowment condition and in the control condition are identical with regard to transaction costs. This solves the problem of differences in transaction costs often criticized in other experiments dealing with lotteries. Second, the task does not induce a bargaining situation. This removes disparities between buyer and seller roles, which are often confounded with endowment. Note, however, that removing the buyer–seller asymmetry may make differences in transaction costs even more salient, thereby calling for adequate control of these costs. Third, our task excludes inspection effects (i.e., gaining some additional information by inspecting an item; Plott & Zeiler, 2007) as an explanation, since endowment and control condition offer the same amount of information. Finally, explanations like the heuristic that preference implies value (Brehm, 1956), or that chosen items are associated with the self (e.g., Gawronski et al., 2007) are not applicable for our task.

Any manipulation also entails some disadvantages, just as ours does. For instance, one could argue that inspection is some form of “light” endowment, and therefore the reference point was manipulated even with this treatment (see Knetsch & Wong, 2009, for a similar argument). This is unlikely for our findings, however, since in Experiment 1 and 2 (and also in Experiment 4) we failed to find even a weak endowment effect in the inspection conditions: inspecting a ticket had no measurable effect on preferences and the majority of participants decided to exchange the inspected ticket.

In Experiment 2 the endowment effect was neatly predicted in a hypothetical situation. This finding differs from earlier results of Loewenstein and Adler (1995) and Van Boven et al. (2000), Van Boven et al. (2003), who report unsuccessful prediction of the endowment effect. This difference may be explained by the different setting we used. In our procedure predictions were not confounded with bargaining role, and in addition, we used lottery tickets instead of coffee mugs, or bottles of wine. Van Boven et al. (2000) report that the egocentric empathy gap was significantly reduced if buyer’s agents themselves experienced ownership. Due to this ownership experience it could have been easier for buyer’s agents to take over a seller’s perspective, leading to a better prediction of selling prices. Thus, the empathy gap responsible for unsuccessful prediction may be due to the lack of fit in bargaining roles. Since we used no bargaining setting these difficulties did not apply to our setting.

The successful prediction of the endowment effect also sheds some light on the ongoing debate on how we are able to predict the behavior and choices of other people (e.g., Gordon, 1986; Kühberger & Bazinger, 2013; Stich & Nichols, 1995). In principle, we can either use theoretical knowledge about others’ mental processes (i.e., apply folk psychological knowledge), or we can simulate what we would do for ourselves by imagining being in exactly the same situation as the target of prediction (i.e., use simulation, or mental replication). It has been argued that a failure to predict other people’s choices would be challenging evidence against the simulation view. However, Kühberger, Kogler, Hug, and Mösl (2006) have shown that many of the reported instances of such misprediction of choices are informal, or invalid. The present finding, that the endowment effect can indeed be correctly predicted, adds to the list of successful cases.

The results of Experiment 3 show that participants expect most regret after exchanging an owned ticket. The assumption that regret may be the source of endowment effects is in line with recent research by Morewedge et al. (2009), who also doubt the prominent role of loss aversion regarding the endowment effect. For the specific case of lottery tasks Risen and Gilovich (2007) report that people are reluctant to exchange lottery tickets because they believe that exchanged tickets are more likely to win a lottery than retained tickets. This can be another reason for a high level of anticipated regret. Thus, in a lottery situation anticipated regret with regard to switching tickets seems to be the crucial factor (Zeelenberg et al., 2000).

The results of the valuation task in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 clearly reveal that people are not staying with their endowed ticket to make a choice in a situation of total indifference, but rather show that the possessed lottery ticket is evaluated significantly higher that an inspected ticket. In contrast, Experiment 4 suggests that the lottery setting might be a crucial precondition for the strong influence of regret. Although we find a similar choice pattern as in our lottery experiments when using coffee mugs, participants seem to be rather willing to give up a possessed mug when they are offered money to exchange it. This does not rule out that regret also plays a role in these settings, but could be interpreted as an indication that loss aversion might be more important in settings dealing with riskless objects, or in bargaining situations where the notion of regret cannot be applied easily (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Tversky & Kahneman, 1991).

Although our data presents strong arguments in favor of regret as the driving force of the endowment effect in lottery settings, loss aversion as an explanation cannot be entirely excluded. Third generation prospect theory (PT3; Schmidt et al., 2008) and other theories of reference-dependent preferences (e.g., Köszegi & Rabin, 2006; Sugden, 2003) allow reference points to be uncertain and achieve to explain the effect of a reluctance to trade an endowed ticket just as well as theories of anticipated regret targeting the decision process. Nevertheless, we suppose that explaining the differences in valuation of endowed tickets compared to inspected tickets is a hard task for loss aversion. Hence, it appears that both, anticipated regret and loss aversion are important factors for explaining endowment effects, but loss aversion may be more relevant when dealing with riskless objects, whereas regret should be especially relevant in lottery settings.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) Grant No. P20718-G14 to the second author. We want to thank Jan-Arvid Hager, Jerome Olsen and Korbinian Räß for their help in organizing the data collection, and especially two anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Since for the last participant there was only one of the 40 tickets left, this person was shown that ticket and another ticket numbered 41. This last participant was also informed that there were only 40 tickets participating, on the pretext that one of the previous numbers was no longer available. The ticket finally chosen was included in the lottery, the other ticket was excluded.

Considering the small sample size in Experiment 1 further statistical analysis is pointless.

In Experiment 2 the sample size was bigger than in Experiment 1, so this test makes sense here.

References

- Bar-Hillel M., Neter E. Why are people reluctant to exchange lottery tickets? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:17–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman I., Kahneman D., Munro A., Starmer C., Sugden R. Testing competing models of loss aversion: An adversarial collaboration. Journal of Public Economics. 2005;89:1561–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Beggan J.K. On the social nature of nonsocial perception: The mere ownership effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Beggan J.K., Scott A. More than meets their eyes: Support of the mere ownership effect. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 1997;5:285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bell D. Regret in decision making under uncertainty. Operations Research. 1982;20:961–981. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm J.W. Post-decision changes in desirability of alternatives. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1956;52:384–389. doi: 10.1037/h0041006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman G.B. Similarity and reluctance to trade. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 1998;11:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski B., Bodenhausen G.V., Becker A.P. I like it, because I like myself: Associative self-anchoring and post-decisional change of implicit evaluations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2007;43:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T., Medvec V.H. The experience of regret: What, when, and why. Psychological Review. 1995;102:379–395. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R.M. Folk psychology as simulation. Mind & Language. 1986;1:158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hertwig R., Ortmann A. Experimental practices in economics: A methodological challenge for psychologists? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2001;24:383–403. doi: 10.1037/e683322011-032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman J.J., Zeelenberg M. Regret in repeat versus switch decisions: The attenuation role of decision justifiability. Journal of Consumer Research. 2002;29:116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Isoni A., Loomes G., Sugden R. The willingness to pay-willingness to accept gap, the “endowment effect”, subject misconceptions, and experimental procedures for eliciting valuations: Comment. American Economic Review. 2011;101:991–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D., Knetsch J.L., Thaler R. Experimental tests of the endowment effect and the Coase Theorem. Journal of Political Economy. 1990;98:728–741. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D., Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D., Tversky A. The psychology of preferences. Scientific American. 1982;246:160–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D., Tversky A. Choices, values and frames. American Psychologist. 1984;39:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Knetsch J.L. The endowment effect and evidence of nonreversible indifference curves. The American Economic Review. 1989;79:1277–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Knetsch J.L., Wong W. The endowment effect and the reference state: Evidence and manipulations. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 2009;71:407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Köszegi B., Rabin M. A model of reference-dependent preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2006;121:1133–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Kühberger A. Why using real and hypothetical payoffs? Behavioral & Brain Sciences. 2001;24:419–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kühberger, A., & Bazinger, C. (2013). Predicting decisions by simulation or by theory? Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Kühberger A., Kogler C., Hug A., Mösl E. The role of the position effect in theory and simulation. Mind & Language. 2006;21:610–625. [Google Scholar]

- Kühberger A., Schulte-Mecklenbeck M., Perner J. Framing decisions: Hypothetical and real. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2002;89:1162–1175. doi: 10.1006/obhd.1999.2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G., Adler D. A bias in the prediction of tastes. Economic Journal. 1995;105:929–937. [Google Scholar]

- Loomes G., Sugden R. An alternative theory or rational choice under uncertainty. The Economic Journal. 1982;92:805–824. [Google Scholar]

- Luce R.D., Fishburn P.C. Rank- and sign-dependent linear utility models for finite first-order gambles. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1991;4:29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez L.F., Zeelenberg M., Rijsman J.B. Regret, disappointment and the endowment effect. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2011;32:962–968. [Google Scholar]

- Miller D.T., Taylor B.R. Counterfactual thought, regret, and superstition: How to avoid kicking yourself. In: Roese N.J., Olson J.M., editors. What might have been: The social psychology of counterfactual thinking. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1995. pp. 305–331. [Google Scholar]

- Morewedge C.K., Shu L.L., Gilbert D.T., Wilson T.D. Bad riddance or good rubbish? Ownership and not loss aversion causes the endowment effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:947–951. [Google Scholar]

- Ortona G., Scacciati F. New experiments on the endowment effect. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1992;13:277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Perner J., Kühberger A. Framing and the theory-simulation controversy: Predicting people’s decisions. In: Viale R., Andler D., Hirschfeld L., editors. Biological and cultural bases of human inference. Erlbaum; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Plott C.R., Smith V.L. An experimental investigation of two exchange institutions. Review of Economic Studies. 1978;45:133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Plott C.R., Zeiler K. The willingness to pay-willingness to accept gap, the “endowment effect”, subjects misconceptions, and experimental procedures for eliciting valuations. The American Economic Review. 2005;95:530–545. [Google Scholar]

- Plott C.R., Zeiler K. Exchange asymmetries incorrectly interpreted as evidence of endowment effect theory and prospect theory? The American Economic Review. 2005;97:1449–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Risen J.L., Gilovich T. Another look at why people are reluctant to switch lottery tickets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93(1):12–22. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage A.P., White E.B. Decision and information structures in regret models of judgment and choice. IEEE, SMC. 1983;13:136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt U., Starmer C., Sugden R. Third-generation prospect theory. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2008;36:203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Starmer C., Sugden R. Probability and juxtaposition effects: An experimental investigation of the common ratio effect. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1989;2:159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Stich S., Nichols S. Second thoughts on simulation. In: Davies M., Stone T., editors. Mental simulation: Evaluations and applications. Blackwell; Oxford: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sugden R. Reference-dependent subjective expected utility. Journal of Economic Theory. 2003;111:172–191. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler R.H. Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 1980;1:39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler R.H. Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science. 1985;4:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A., Kahneman D. Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1991;107:1039–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A., Kahneman D. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1992;5:297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven L., Dunning D., Loewenstein G. Egocentric empathy gaps between owners and buyers: Misperceptions of the endowment effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:66–76. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven L., Loewenstein G., Dunning D. Mispredicting the endowment effect: Underestimation of owners’ selling prices by buyer’s agents. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 2003;51:351–365. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Ven N., Zeelenberg M. Regret aversion and the reluctance to exchange lottery tickets. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2011;32:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk E., Van Knippenberg D. Buying and selling exchange goods: Loss aversion and the endowment effect. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1996;17:517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk E., Van Knippenberg D. Trading wine: On the endowment effect, loss aversion, and the comparability of consumer goods. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1998;19:485–495. [Google Scholar]

- Wakker P.P., Tversky A. An axiomatization of cumulative prospect theory. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1993;7:147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zeelenberg M., Pieters R. A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2007;17:3–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1701_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeelenberg M., Van den Bos K., Van Dijk E., Pieters R. The inaction effect in the psychology of regret. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:314–327. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeelenberg M., Van Dijk W.W., Manstead A.S.R., Van der Pligt J. On bad decisions and disconfirmed expectancies: The psychology of regret and disappointment. Cognition and Emotion. 2000;14:521–541. [Google Scholar]