Background: PDGF- and VEGF-related factor (Pvr) ligands are implicated in the establishment and dispersal of Drosophila embryonic hemocytes.

Results: Hemocyte-restricted Pvr pathway activation in pvf2–3 mutants is sufficient for hemocyte survival and non-invasive migration, whereas epithelial-specific Pvf expression is required for hemocyte invasive migration.

Conclusion: Pvfs are required for invasion, but not directional guidance of hemocytes.

Significance: We uncover a novel role for Pvfs in hemocyte trans-epithelial migration.

Keywords: Cell Invasion, Cell Migration, Drosophila, Hematopoiesis, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) family members are essential and evolutionary conserved determinants of blood cell development and dispersal. In addition, VEGFs are integral to vascular growth and permeability with detrimental contributions to ischemic diseases and metastatic cancers. The PDGF/VEGF-receptor related (Pvr) protein is implicated in the migration and trophic maintenance of macrophage-like hemocytes in Drosophila melanogaster embryos. pvr mutants have a depleted hemocyte population and a breakdown in hemocyte distribution. Previous studies suggested redundant functions for the Pvr ligands, Pvf2 and Pvf3 in the regulation of hemocyte migration, proliferation, and size. However, the precise roles that Pvf2 and Pvf3 play in hematopoiesis remain unclear due to the lack of available mutants. To determine Pvf2 and Pvf3 functions in vivo, we generated a genomic deletion that simultaneously disrupts Pvf2 and Pvf3. From our studies, we identified contributions of Pvf2 and Pvf3 to the Pvr trophic maintenance of hemocytes. Furthermore, we uncovered a novel role for Pvfs in invasive migrations. We showed that Pvf2 and Pvf3 are not required for the directed migration of hemocytes, but act locally in epithelial cells to coordinate trans-epithelial migration of hemocytes. Our findings redefine Pvf roles in hemocyte migration and highlight novel Pvf roles in hemocyte invasive migration. These new parallels between the Pvr and PDGF/VEGF pathways extend the utility of the Drosophila embryonic system to dissect physiological and pathological roles of PDGF/VEGF-like growth factors.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis is a critical developmental process that requires stringent parallel regulation of blood cell proliferation (1), homeostasis (2), and migration (3, 4). Deregulated hematopoiesis has potentially lethal implications that include the onset of leukemic diseases or pathogenic disruptions to cellular and humoral immunity (5, 6). As with many fundamental cellular and developmental processes, there is a substantial body of evidence that evolutionarily conserved signal transduction pathways orchestrate defining features of hematopoiesis in distantly related phyla (7, 8). For example, homologs of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) pathways direct key processes in the development (9–11) and migration (12, 13) of blood cells in mammals and Drosophila melanogaster (14, 15). With an unrivaled capacity for intricate genetic manipulations and clearly defined embryonic development, Drosophila is a particularly instructive model to examine the involvement of the VEGF/PDGF pathways in hematopoiesis.

The Drosophila PDGF/VEGF-receptor related (Pvr)2 RTK has an intracellular split-tyrosine kinase domain and seven Ig-like repeats that bind the PDGF- and VEGF-related factor (Pvf) ligands Pvf1, Pvf2, and Pvf3 (10, 12, 16). In Drosophila, the embryonic blood system is dominated by a dynamic subset of phagocytic hemocytes (17, 18). These cells express the Pvr receptor and functionally resemble myeloid lineage cells in vertebrates (9, 19). Hemocytes arise from the head mesoderm and initiate a series of stereotypical anterior to posterior migrations along epithelial surfaces (18). Ventrally located hemocytes migrate along parallel passages on the dorsal and ventral planes of the developing ventral nerve cord (VNC) (20), whereas dorsally located hemocytes migrate toward and abut the extending germband (18). Ventral hemocytes secrete extracellular basement membrane molecules that support development of the VNC (21, 22). A portion of hemocytes leave open migratory routes, breach epithelial barriers, and enter the surrounding tissues (18, 23). Ventral hemocytes initiate a series of local movements characterized by migration across the VNC, whereas dorsal hemocytes penetrate the extended germband epithelium (18, 23). In contrast to open migration, invasive migration by dorsal hemocytes requires a specialized system for the dissolution of cell-cell epithelial junctions and evidence indicates that RhoL/Rap1 GTPases activate integrins in hemocytes to facilitate invasive migration (23, 24).

Several studies implicate the Pvf-Pvr signal transduction axis in numerous aspects of embryonic hematopoiesis. For example, cell culture studies suggest that pvr, pvf2, and pvf3 determine hemocyte size (25, 26), whereas genetic studies implicated pvf2 in the proliferation of larval hemocytes (27). In addition to controlling the size and viability of hemocytes, there is convincing evidence that the Pvr pathway regulates a number of developmental migrations (16, 28–32). Genetic analysis established a role for Pvf1 as a guidance cue for border cell migration in oogenesis (16, 32) and in wound closure in the larval epidermis (33). However, our understanding of the role of Pvr in embryonic hemocyte migration has evolved less clearly. pvr null mutants are embryonic lethal with reduced hemocyte numbers and disrupted hemocyte migration (10, 12). These data were initially interpreted to suggest that the Pvr axis controls the developmental migration of embryonic hemocytes (12). A subsequent study uncovered an essential trophic role for Pvr signals in embryonic hemocytes, as expression of the pan-caspase inhibitor p35 in the hemocytes of pvr mutants restored hemocyte numbers (9).

The embryonic expression patterns of pvf2 and pvf3 correlate with routes of hemocyte migration and simultaneous depletion of pvf2 and pvf3 with RNAi disrupts hemocyte migration (12, 13). From these observations, Pvf2 and Pvf3 were proposed to act as chemokines that attract Pvr-positive hemocytes along migratory routes (13). These data were originally supported by the lack of hemocyte migration in pvr mutants(12). However, it is noteworthy that the expression of p35 in hemocytes of pvr mutants restores many features of the distribution of hemocytes throughout embryos (9). These findings point to non-essential requirements for Pvr in the dispersal of embryonic hemocytes. The roles attributed to Pvfs and Pvr add confusion to the context-relevant biological function of Pvfs in hematopoiesis. Much of the confusion is a direct result of a lack of available pvf2 and pvf3 mutants, which forced previous studies to rely on overexpression or RNAi-based approaches.

To address this issue, we generated a genomic deletion that specifically disrupts pvf2 and pvf3 (pvf2–3) (34) and examined the consequences for embryonic hematopoiesis and migration. We found that deletion of pvf2 and -3 was embryonic lethal, with drastically reduced hemocyte numbers and impaired distribution of hemocytes. We identified trophic roles for Pvf2 and Pvf3 in hemocyte survival, consistent with previous evidence of Pvr survival functions (9). Upon analysis of hemocyte migration we found that pvf2 and pvf3 do not exhibit chemoattractant activity. Instead we found a novel requirement for hemocyte-extrinsic Pvfs to direct invasive hemocyte migration. Our findings establish that pvf2 and pvf3 sustain the embryonic hemocyte population and uncover a novel hemocyte-independent role for Pvfs to coordinate hemocyte invasion through epithelial barriers. These data establish the Drosophila embryo as an ideal model to explore the requirements for PDGF and VEGF-like ligands in processes of invasive cell migration during development and disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly Stocks

All fly stocks were maintained at 18 °C and crosses were performed at 25 °C on a standard cornmeal media (Nutri-Fly Bloomington Formulation, Genesee Scientific). Embryos were collected at 25 °C on agar plates supplemented with apple juice, sugar, and methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate fungus inhibitor (Sigma H5501). The following fly lines were used in this study: w1118, P{XP}Pvf2d00645, and PBac{WH}Pvf3f04842 (Exelixis Harvard Collection), Df(2L)BSC291 55 (Bloomington Stock Center (BSC) number 23676), crq-Gal4 (BSC number 25041), UAS-eGFP (K. King-Jones, University of Alberta), UAS-mCD8-GFP (BSC number 28832), UAS-pvf2 (27), UAS-pvrCA (16), UAS-Ras85DV12 (BSC number 4847), UAS-p35 (BSC number 5072), pvr5363 (19), and byn-GAL4 (29).

pvf2–3 Deletion and Validation

We used standard genetic approaches to excise a genomic region between the P{XP}Pvf2d00645 and PBac{WH}Pvf3f04842 (35). Primers used to confirm pvf2–3 excision targeted the P{XP}Pvf2d00645 and PBac{WH}Pvf3f04842 insertion elements. Primers sequences were: 5′-AATGATTCGCAGTGGAAGGCT-3′ and 5′-GACGCATGATTATCTTTTACGTGAC-3′. Primers sequences for the detection of pvf transcripts were as follows: pvf1, 5′-GCGCAGCATCATGAAATCAACCG-3′ and 5′-TGCACGCGGGCATATAGTAGTAG-3′; pvf2, 5′-TCAGCGACGAAACGTGCAAGA-3′ and 5′-TTTGAATGCGGCGTCGTTCC-3′; pvf3, 5′-AGCCAAATTTGTGCCGCCAAG-3′ and 5′-CTGCGATGCTTACTGCTCTTCACG-3′.

Embryo Immunofluorescence

Embryo immunofluorescence buffers were 1× PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 (PT), 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 5% normal goat serum in PT (PT-NGS). Embryos were collected from apple juice plates and dechorionated in 50% bleach for 2 min and rinsed in water. After fixation in a 1:1 solution of 4% formaldehyde, PBS:heptane for 20 min in a 37 °C shaker, embryos were devitellinized by a 30-s vortex in a 1:1 heptane:methanol solution. Embryos were permeabilized in PT for 30 min, blocked for 1 h in PT-NGS, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies in PT-NGS. Embryos were washed 3× 5 min in PT, 3× 15 min in PT with 300 mm NaCl, rinsed 5 times in PT, and then incubated for 30 min in PT-NGS. Embryos were incubated with preabsorbed secondary antibodies for 1 h. Before mounting, embryos were washed 3× 5 min then 4× 15 min in PT and 1 min in PBS. Embryos were mounted in Fluoromount (Sigma F4680). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000) (Invitrogen G10362), mouse anti-armadillo (1:250) (DSHB N27A1), and rat anti-Pvr (1:200) (41). The following secondary antibodies and stains were used: goat anti-rabbit Alexa-488 (1:500) (Invitrogen A11008), goat anti-mouse Alexa-647 (1:500) (Invitrogen A21235), goat anti-mouse Alexa-568 (1:500) (Invitrogen A11004), and Hoechst 33258 (1:1000) (Molecular Probes H-3569).

Confocal Microscopy

Embryos were imaged on an Olympus IX-81 microscope with a Yokagawa CSU X1 spinning disk confocal scan head. Images were collected as a Z-series using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices Inc.) and FIJI software (ImageJA 1.45b). Z-series were processed into a single Z-projections and movies were constructed and analyzed with Imaris software (Bitplane Inc.). Each individual whole embryo image was acquired from 3 or 4 overlapping 20× objective fields and compiled using Photoshop CS3 (Adobe). All figures were assembled with Photoshop CS3 and Illustrator CS3 (Adobe).

Hemocyte Quantification

Hemocytes from whole embryo images were quantified according to cell morphology features, GFP fluorescent contrast, size, and set parameters determined by the Columbus Software (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). This process was entirely automated and the same quantification parameters were established and applied across all genotypes. Quantification of each genotype was automated with identical parameters. Cell numbers were graphed by Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

TUNEL Labeling

The In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR red (Roche Applied Science number 12156792910) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Embryos were prepared and mounted as the described in the immunofluorescence protocol with the addition of 50 μl of TUNEL labeling mixture/enzyme solution (45 μl of labeling/5 μl of enzyme) to the secondary antibody step and an overnight incubation at 4 °C.

RESULTS

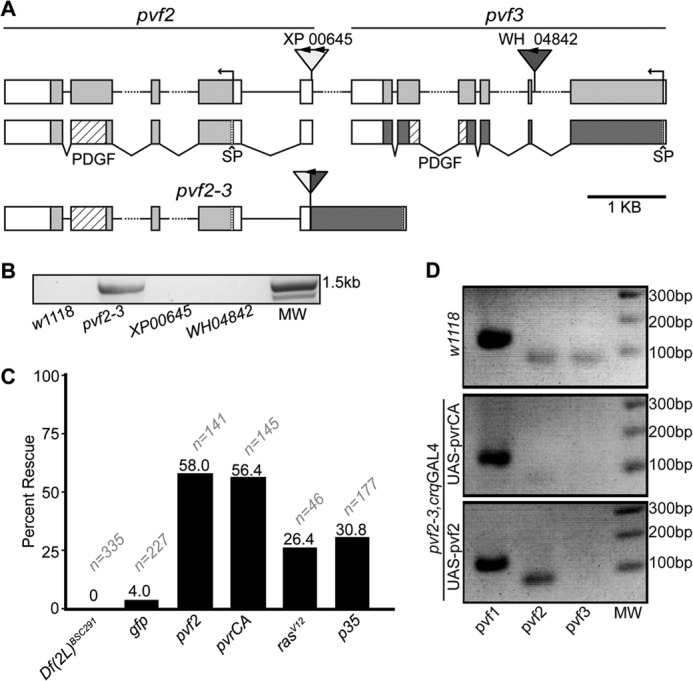

Genomic Deletion of pvf2 and pvf3

The pvf2 and pvf3 genes lie in a tandem, uninterrupted arrangement on the left arm of the second chromosome. To clarify the functions of Pvf2 and Pvf3 during embryogenesis, we used FLP-based recombination of FRT-bearing P-elements in the pvf2 and pvf3 loci to generate a genomic deletion that ablates the Pvf2 promoter and five of six exons in Pvf3 (pvf2–3, Fig. 1A). We confirmed that the pvf2–3 genomic excision was present in pvf2–3 mutants, but absent from the parental P-element insertion fly lines and control w1118 lines (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the individual pvf2 and pvf3 insertion lines, the pvf2–3 homozygous mutation was embryonic lethal. The pvf2–3 mutation was also lethal in heterozygosity with a genomic deficiency that spans the pvf2 and pvf3 locus (Df(2L)BSC291, Fig. 1C), indicating that the homozygous lethality of pvf2–3 mutants is a result of disruptions to the pvf2 and pvf3 loci.

FIGURE 1.

A genomic deletion of the pvf2-pvf3 locus in Drosophila. A, organization of the pvf2 and pvf3 locus in wild-type and pvf2–3 deletion flies. The {XP}Pvf200645 (XP00645) and {WH}Pvf3f04842 (WH04842) are shown. FRT sites are indicated with arrowheads. Gray and white boxes represent exons and untranslated regions, respectively. pvf2 and pvf3 cDNA structures are shown below the genomic map. Coding sequences are shown with gray boxes. PDGF domains with diagonal striped boxes and signal peptide (SP) sequences as horizontal striped boxes are indicated. The pvf2–3 map shows the deletion product of FLP-mediated recombination between the FRT-bearing XP and WH P-elements. B, PCR confirmation that the P-element recombination product is present in the deletion strain, but absent from wild-type and parental P-element insertion lines. The PCR primers target the XP00645 and WH04842 P-elements. DNA molecular weight (MW) markers are shown. C, quantification of viable pvf2–3 mutants. The first column shows pvf2–3 in heterozygosity with the Df(2L)BSC291 deficiency. The remaining columns show homozygous pvf2–3 mutant flies that express GFP, pvf2, pvrCA, rasV12, or p35 transgenes under the hemocyte-specific croquemort (crq) promoter. Percent rescue is the percentage of rescued progeny based on expected Mendelian ratios. Sample size (n) is indicated for each genotype. D, detection of pvf1, -2, and -3 transcripts in wild-type and homozygous pvf2–3 mutants flies that express the indicated rescue constructs under the crq promoter.

Given that pvr mutants are also embryonic lethal, we hypothesized that simultaneous loss of Pvf2 and Pvf3 constricted Pvr pathway activation. We therefore tested whether re-engagement of Pvr reverted the lethality of pvf2–3 mutants. Specifically, we repleted Pvr signaling in the embryonic hemocyte compartment of pvf2–3 mutants by the induced expression of various Pvr pathway components with the GAL4/UAS system. To do this, we used an established hemocyte-specific GAL4 driver croquemort (crqGAL4) (36) to express Pvf2, or constitutively active variants of Pvr (PvrCA) or Ras (RasV12) in pvf2–3 mutants (Fig. 1C). Expression of Pvf2, PvrCA, and RasV12 in hemocytes partially rescued lethality of pvf2–3 homozygous mutants, whereas hemocyte-specific GFP expression did not. Previous evidence implicated Pvr in hemocyte trophic survival, as hemocyte-specific expression of the pan-caspase inhibitor p35 rescued hemocyte death in pvr mutant embryos (9). To determine whether Pvf2 and Pvf3 contribute to trophic signaling, we used the crqGAL4 driver to express p35 in hemocytes of pvf2–3 mutant embryos. We found that expression of p35 in hemocytes also produced a partial rescue of pvf2–3 mutant lethality (Fig. 1C). Notably, a greater proportion of pvf2–3 mutants were rescued by hemocyte-specific expression of Pvf2 and PvrCA than observed with the RasV12 and p35 transgenes.

As the pvf2–3 deficiency does not ablate the coding region of pvf2, we considered the possibility that our deletion strain does not affect pvf2 expression. To test this hypothesis, we examined pvf2 transcript levels in pvf2–3 mutants rescued to adulthood through crqGAL4-mediated expression of pvf2 or PvrCA (Fig. 1D). We detected pvf1, pvf2, and pvf3 transcripts in wild-type flies. In contrast, we found that pvf2–3 homozygous mutants that express a pvf2 rescue construct lacked pvf3 transcripts and maintained expression of pvf1 and pvf2. These data suggest that pvf2–3 deficiency disrupts expression of pvf3. We also found that pvf2–3 homozygous mutants that express a PvrCA rescue construct exhibit weakly detectable pvf2 transcript or no pvf3 transcript and maintained expression of pvf1. As the PvrCA rescue flies are homozygous for the pvf2–3 deletion, our data confirm that the genomic deletion strongly disrupts expression of pvf2 and ablates the expression of pvf3 and establish that hemocyte-specific activation of the Pvr pathway is sufficient to restore viability to pvf2–3 mutants.

pvf2–3 Mutants Exhibit Defects in Hemocyte Distribution

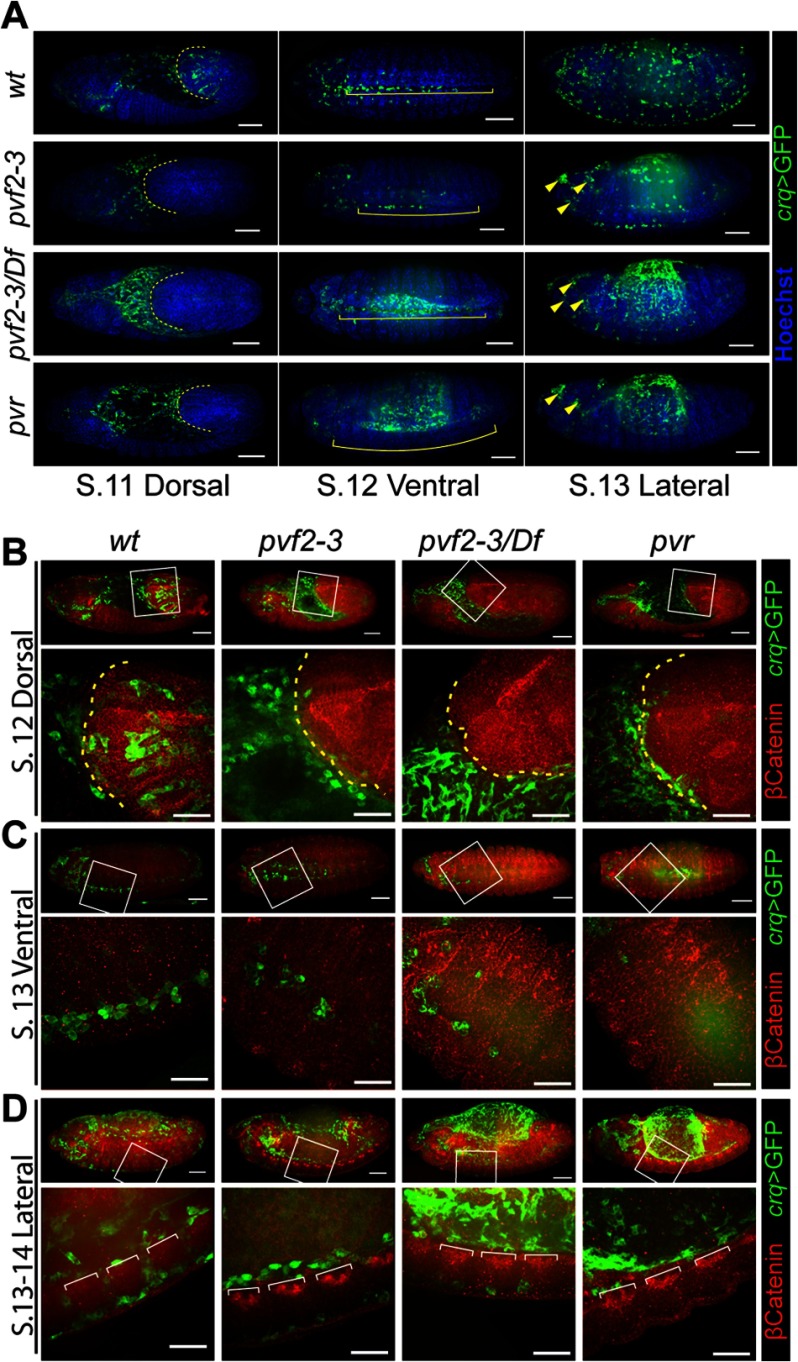

As Pvr mutant embryos exhibit defects in embryonic hemocyte distribution, we assessed hemocyte migration in pvf2–3 mutant embryos. We visualized hemocytes through crqGAL4-specific expression of GFP and labeled the epithelial adherens junction protein Armadillo (β-Catenin) to visualize cell borders (Fig. 2). As expected, wild-type hemocytes populated the extended germband of stage 12 embryos. In contrast, hemocytes were completely absent from the germband in pvf2–3, pvf2–3/Df(2L)BSC291, and pvr mutants (Fig. 2, A, first column, and B). Hemocytes in pvf2–3, pvf2–3/Df(2L)BSC291, and pvr mutant embryos migrated posteriorly across the dorsal plane of the amnioserosa at the same rate as the retracting germband, but failed to enter the germband. We observed a residual population of hemocytes at the ventral midline in both pvf2–3 mutants and pvf2–3/Df embryos, but no hemocytes at the ventral midline in pvr mutants (Fig. 2, A, second column, and C and D). In stage 13 wild-type embryos, anterior hemocytes traverse the ventral midline to converge with hemocytes distributed through the posterior of the embryo by the retracting germband (Fig. 2C). We found hemocytes in the anterior half of the ventral midline in pvf2–3 and pvf2–3/Df(2L)BSC291 embryos, but a complete absence of posterior hemocytes in pvf2–3, pvf2–3/Df(2L)BSC291, and pvr mutants. We also observed defined aggregation of hemocytes in the head of pvf2–3, pvf2–3/Df(2L)BSC291, and pvr mutant embryos (Fig. 2A, arrowheads).

FIGURE 2.

Hematopoiesis and hemocyte migration in pvf2–3 mutants. A–D, stage 11–14 crqGAL4,UAS-eGFP/+ (wt), pvf2–3,crqGAL4/pvf2–3,UAS-eGFP (pvf2–3), UAS-mCD8-GFP;pvf2–3,crqGAL4/Df(2L)BSC291 (pvf2–3/Df), and UAS-eGFP;pvr,crqGAL4/pvr (pvr) embryos. Hemocytes were visualized by eGFP expression (green in A). All embryos were oriented with the anterior region to the left and the dorsal surface facing up. A, embryos were counterstained with Hoechst (blue in A) to visualize DNA. Scale bars represent 50 μm. Dashed yellow lines in stage 11 embryos indicate the edge of the retracting germband. Yellow brackets in stage 12 embryos indicate the ventral midline region. Yellow arrowheads in stage 13 pvf2–3, pvf2–3/Df, and the pvr mutant eGFP frame mark hemocyte clumps in the head. B–D, hemocytes were visualized by GFP expression (green in B). The adherens junction protein, Armadillo (β-Catenin), was visualized by antibody labeling (red in B). The boxed regions in the first row of each embryo are shown below at higher magnification. Scale bars represent 50 μm in whole embryo panels and 25 μm in high magnification panels. B, dashed yellow line indicates the edge of the retracting germband. D, white brackets demarcate axon bundles of the ventral nerve cord.

A subset of hemocytes traverses the dorsal surface of the VNC during stages 11–13 of embryogenesis and then crosses through gaps between axon bundles of the VNC to populate the space between the ventral epidermis and the VNC (Fig. 2D and supplemental Video S1). As hemocytes populate the ventral midline they cross back and forth through open gaps in the VNC (Fig. 2D). We found that hemocyte passages through the VNC were largely absent along the trunks of pvf2–3 and pvf2–3/Df(2L)BSC291 embryos. Only a residual population of hemocytes entered the ventral side of the VNC in the head of the embryo and appeared to be isolated from hemocytes on the dorsal side of the VNC in the embryonic trunk (Fig. 2D, second and third columns). We did not detect hemocytes along either the dorsal or ventral surface of the VNC of pvr mutant embryos (Fig. 2D, fourth column). In summary, hemocyte distribution defects are remarkably similar between pvr and pvf2–3 mutant embryos, with the exception that we observe residual hemocyte distribution along the ventral midline of pvf2–3 mutants.

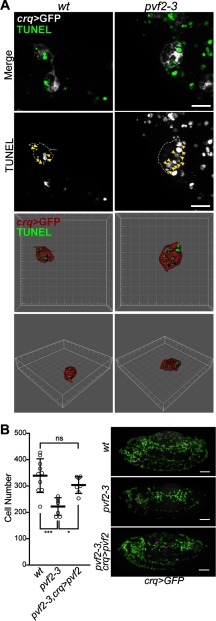

Pvf2 and Pvf3 Provide Trophic Signals to Hemocytes

Given that hemocyte-specific expression of p35 rescued pvf2–3 lethality and the established trophic roles of Pvr in hemocyte survival, we speculated that Pvf2 and Pvf3 are important trophic factors for the survival of hemocytes. We assessed apoptotic cell death in wild-type and pvf2–3 mutant embryos that expressed GFP in hemocytes. We did not observe major differences between the distribution of apoptotic corpses in pvf2–3 mutant and wild-type embryos. However, we noticed that anterior hemocytes in stage 13 pvf2–3 mutant embryos formed dense aggregates with an enlarged and heavily vacuolated cell morphology. High magnification images show that these hemocytes engulfed numerous apoptotic bodies at one time compared with wild-type hemocytes (Fig. 3A, arrowheads). These data indicate elevated levels of phagocytic activity in the anterior of pvf2–3 mutants and are reminiscent of the cannibalistic phagocytosis of hemocytes reported in pvr mutants (9). We quantified hemocytes in wild-type embryos, pvf2–3 mutant embryos, and pvf2–3 homozygous mutant embryos that express pvf2 in hemocytes (pvf2–3,crq>pvf2). pvf2–3 mutants exhibited a significant decrease in hemocyte numbers compared with wild-type embryos. In contrast, hemocyte-specific expression of pvf2 restored hemocyte numbers to wild-type levels (Fig. 3B). Our findings show that Pvf2 and Pvf3 provide essential trophic cues for the survival of embryonic hemocytes.

FIGURE 3.

Hemocyte survival in pvf2–3 mutants. A and B, hemocytes in crqGAL4,UAS-eGFP/+ (wt), pvf2–3,crqGAL4/pvf2–3,UAS-eGFP (pvf2–3), and pvf2–3,crqGAL4,UAS-GFP,UAS-pvf2 (pvf2–3,crq>pvf2) embryos. A, high magnification images of hemocytes from wt and pvf2–3 mutant embryos. Hemocytes were visualized by eGFP expression (white in Merge) and apoptotic cell death by TUNEL staining (green in Merge). Scale bar represents 10 μm. Space filling visualization is shown for the bottom two rows. B, quantification of hemocytes from stage 13 embryos of the indicated genotypes. Horizontal dashes represent mean cell number of 340 in wt, 222 in pvf2–3, and 304 in pvf2–3,crq>pvf2 embryos. Statistical significance of differences between genotypes was calculated by analysis of variance analysis. Asterisks represent the respective p values: *** = 0.0002; * = 0.0146; and ns, nonsignificant = 0.3897. Representative embryos are shown for each genotype. Quantified hemocytes are highlighted in green. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

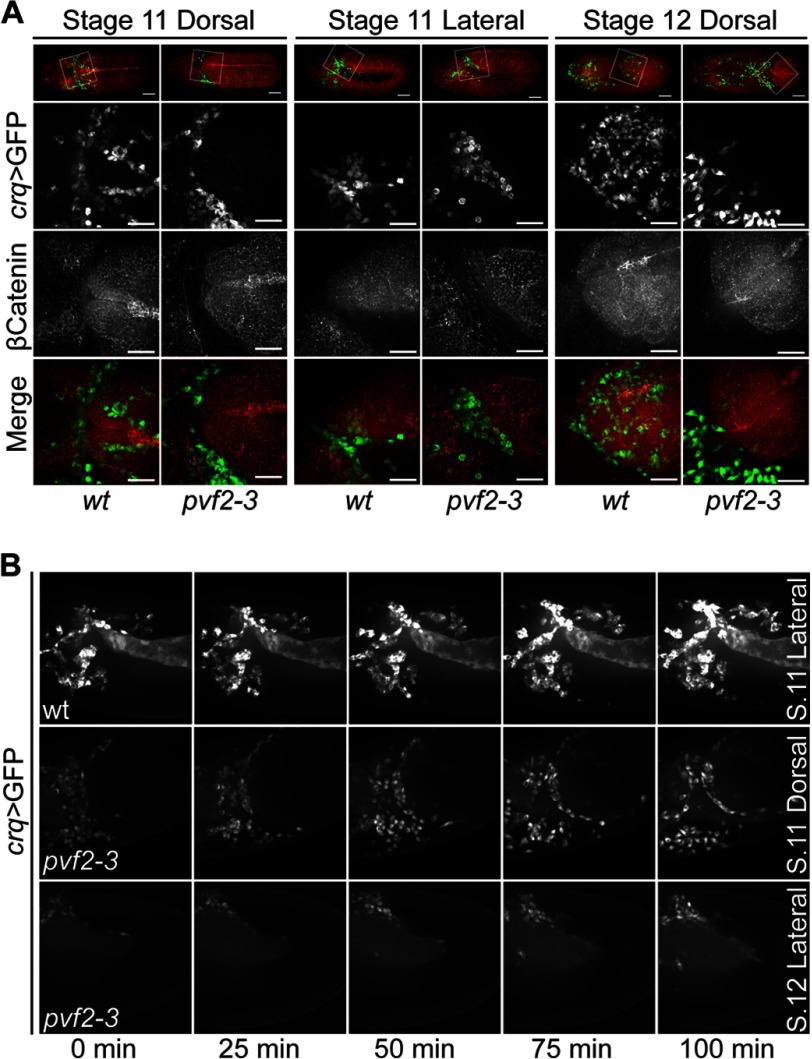

Pvf2 and Pvf3 Direct Germband Invasion by Hemocytes

During embryogenesis, hemocytes enter the extended germband in a process that requires the dissolution of epithelial cell-cell junctions followed by a chain migration of hemocytes through newly formed intercellular gaps into the germband (23). As hemocytes are absent from the germband of pvf2–3 mutant embryos, we visualized germband invasions in wild-type and pvf2–3 mutant embryos. We found that a subset of wild-type and pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes migrated toward and accumulated at the anterior margin of the extended germband in stage 11 embryos (Fig. 4A). Wild-type hemocytes then penetrated the epithelium and individually invaded at defined locations of disrupted adherens junction along the terminus and underside of the extended germband at stage 12 (Fig. 4A). In contrast, we found that pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes did not penetrate the epithelium. By stage 12 nearly all wild-type dorsal hemocytes were within the germband, whereas all dorsal pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes remained in close contact with the retracting margin of the germband. The localization and migration of hemocytes relative to the germband epithelium remained constant throughout germband retraction in pvf2–3 mutants. However, the inability of mutant hemocytes to invade and pass through the epithelial junctions of the germband results in a marked deficit in posterior hemocytes in stage 13 embryos (Fig. 2A, fourth column).

FIGURE 4.

Hemocyte invasion of the germband in pvf2–3 mutant embryos. A, stage 11–12 crqGAL4,UAS-eGFP/+ (wt) and pvf2–3,crqGAL4/pvf2–3,UAS-eGFP (pvf2–3) embryos. Hemocytes were visualized by eGFP expression (green in Merge) and Armadillo (β-Catenin) was visualized by antibody labeling (red in Merge). The boxed regions in the first row are shown at higher magnification in the second to fourth rows. Scale bars represent 50 μm in whole embryo panels and 25 μm in high magnification panels. B, individual frames from live images of wt and pvf2–3 embryos of the indicated stages and orientations. Hemocytes are visualized by eGFP expression as above. The upper panel captures germband invasion by hemocytes in wt embryos. The lower two panels show a failure of pvf2–3 hemocytes to invade the germband.

To follow hemocyte movements at the germband interface in greater detail, we visualized GFP expressing hemocytes in live wild-type and pvf2–3 mutant embryos. Wild-type hemocytes entered the germband epithelium through several restricted locations (Fig. 4B and supplemental Video S2). When we examined pvf2–3 mutants, we found that hemocytes exhibited dynamic and continuous movements along the germband interface (Fig. 4B and supplemental Videos S3 and S4). Despite an intact migration to the correct location and the appropriately positioned accumulation of hemocytes at the presumptive sites of epithelial invasion, all pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes failed to penetrate the germband epithelium. Examination of live and fixed pvf2–3 mutants revealed that posterior migration of dorsally located hemocytes was intact in mutant hemocytes despite their inability to enter the retracting germband. In summary, our observations reveal that the route and rate of dorsal migration is intact, but that the initial step of epithelial invasion is completely absent in pvf2–3 mutants. Together, these findings indicate that Pvf2 and Pvf3 are required for hemocyte invasion across epithelial barriers, but that loss of Pvf2 and -3 does not disrupt the dorsal-posterior migration of embryonic hemocytes to the germband interface.

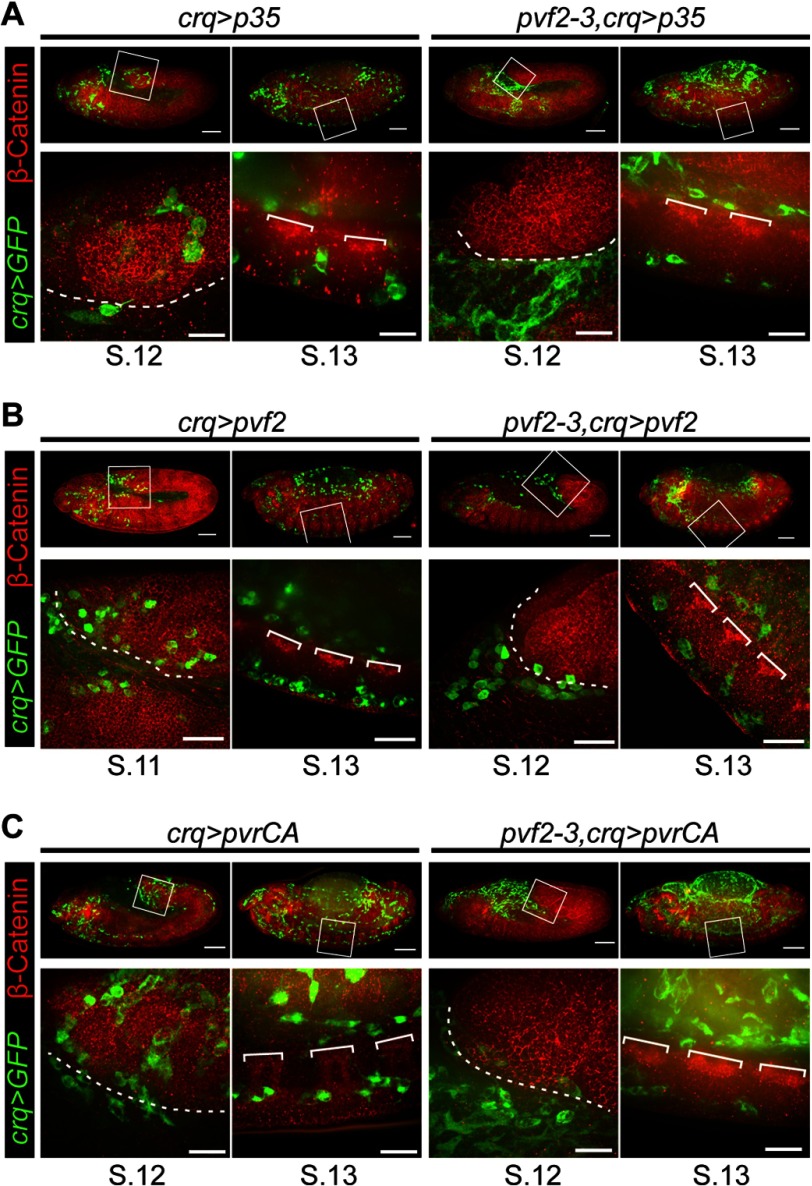

Inhibition of Apoptosis Restores Migration, but Not Epithelial Invasion in pvf2–3 Mutant Hemocytes

As pvf2–3 mutants display a marked reduction in hemocyte numbers, we considered the possibility that the inability of mutant hemocytes to penetrate the extended germband reflects an underlying defect in cell viability. To test this hypothesis, we expressed the baculovirus pan-caspase inhibitor p35 in pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes (pvf2–3,crq>p35, Fig. 5A). Our initial studies confirmed that expression of p35 in hemocytes reverts the lethality of the pvf2–3 deletion (Fig. 1). We found that p35 restored the posterior migration of ventrally located hemocytes in pvf2–3 mutant embryos. In contrast, we found that p35 expression did not restore the migration of hemocytes across the VNC in pvf2–3 mutants (Fig. 5A, fourth column). In addition, we found that pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes that express p35 failed to invade the extended germband of stage 11 embryos (Fig. 5A, third column). Together these observations suggest that inhibition of apoptosis restores the posterior migration of ventral hemocytes in pvf2–3 mutant embryos. In contrast, invasive migration into the extended germband or across the ventral nerve cord is independent of trophic signals from Pvf2 and Pvf3.

FIGURE 5.

Hemocyte migration patterns in pvf2–3 mutants that express Pvf2, a constitutively active Pvr or the pan-caspase inhibitor p35. A–C, hemocytes were visualized by eGFP expression (green) and Armadillo (β-Catenin) was visualized by antibody labeling (red). The boxed regions were visualized at higher magnification shown in the lower panel. Scale bars represent 50 μm in whole embryo panels and 15 μm in high magnification panels. The dashed white line indicates the edge of the retracting germband. White brackets demarcate axon bundles of the ventral nerve cord. A, crqGAL4,UAS-eGFP/UAS-pvf2 (crq>pvf2) and pvf2–3,crqGAL4,UAS-GFP,UAS-pvf2(pvf2–3,crq>pvf2) embryos are shown. B, crqGAL4,UAS-eGFP/UAS-pvrCA (crq>pvrCA) and UAS-mCD8-GFP/+;pvf2–3,crqGAL4/pvf2–3,UAS-pvrCA (pvf2–3,crq>pvrCA) embryos are shown. C, crqGAL4,UAS-eGFP/UAS-p35 (crq>p35) and UAS-mCD8-GFP/+;pvf2–3,crqGAL4/pvf2–3,UAS-p35 (pvf2–3,crq>p35) embryos are shown.

Extrinsic Signals Guide the Invasive Migration of Embryonic Hemocytes

Our data suggest that non-trophic signals from the Pvr pathway control invasive migration of hemocytes. To test if invasive signals from Pvf ligands are hemocyte-autonomous or extrinsic, we assessed the migratory and invasive behavior of wild-type hemocytes and pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes that express Pvf2 (crq>pvf2 and pvf2–3,crq>pvf2, Fig. 5B). Hemocyte-specific expression of Pvf2 restores viability to pvf2–3 mutants (Fig. 1) and restores hemocyte numbers to wild-type levels in mutant embryos (Fig. 3). We found that expression of Pvf2 in wild-type hemocytes does not impair hemocyte distribution (Fig. 5B, first and second columns). We found that the expression of Pvf2 in pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes completely restored anterior to posterior migration of ventral hemocytes, but failed to restore invasion of the extended germband in stage 12 embryos (Fig. 5B, third and fourth columns).

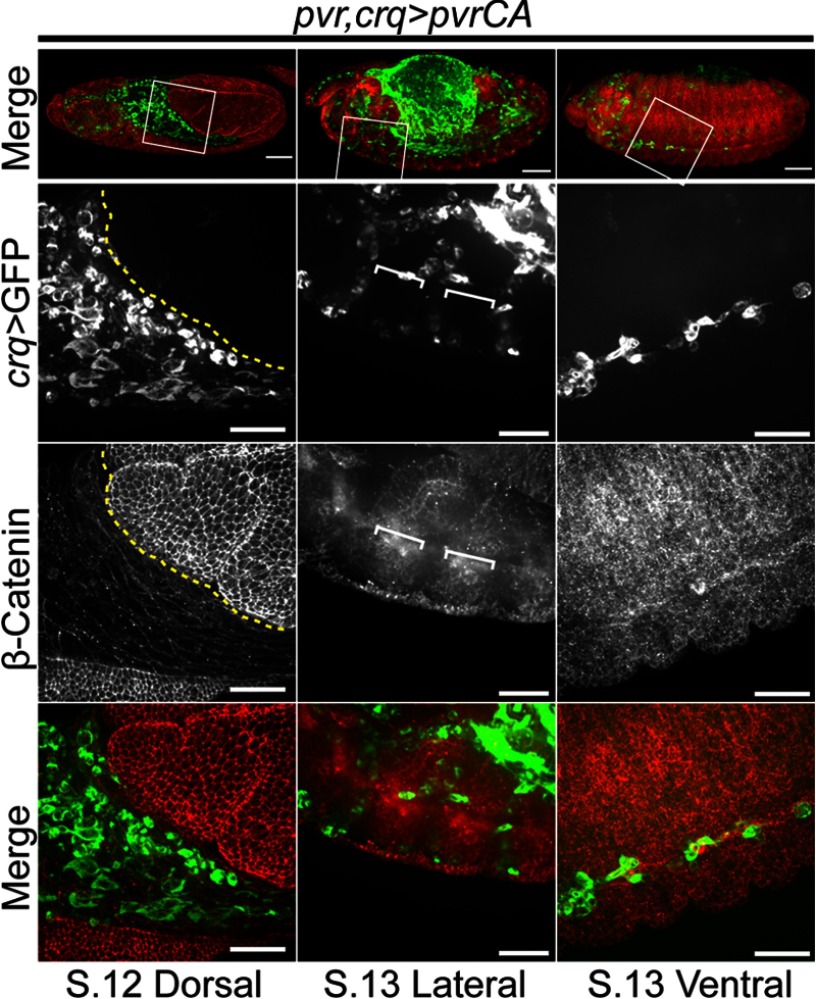

We then tracked the migratory and invasive behavior of pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes that express a constitutively active Pvr variant. For these experiments we followed the migration of GFP positive hemocytes that express PvrCA in wild-type (crq>PvrCA) and pvf2–3 mutant (pvf2–3,crq>PvrCA) embryos (Fig. 5C). pvf2–3,crq>PvrCA hemocytes bypass requirements for Pvf2 or Pvf3 ligands to activate Pvr signals and rescue the lethality of pvf2–3 mutants (Fig. 1). Interestingly, uniform activation of the Pvr pathway in hemocytes of otherwise wild-type embryos did not disrupt the migration of hemocytes (Fig. 5C, first and second columns). We found that expression of PvrCA restored posterior migration to ventrally located pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes, but failed to restore transition across the posterior VNC (Fig. 5C, fourth column). Likewise, expression of PvrCA failed to restore invasion of the extended germband by pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes (Fig. 5C, third column). These findings suggest that uniform Pvr activation in hemocytes is sufficient for the survival and posterior migration of embryonic hemocytes, but insufficient for the invasion of embryonic epithelial structures. In summary, hemocyte-specific restoration of the Pvr pathway restores hemocyte numbers and re-establishes the stereotypical routes of hemocyte migration in pvf2–3 mutant embryos. In contrast, activation of the Pvr pathway fails to restore invasive movements to pvf2–3 mutant hemocytes.

The Pvr Pathway Is Dispensable for the Posterior Migration of Embryonic Hemocytes

Whereas several reports implicate Pvf2 and Pvf3 as chemokines for embryonic hemocytes (12, 13, 28, 29) our findings are more consistent with a previous report that the Pvf/Pvr axis is not required for hemocyte migration (9). We hypothesized that the apparent migratory defects previously ascribed to Pvf2 and Pvf3 disruptions are an indirect consequence of the loss of hemocyte numbers that accompany disruptions to pvf2 and pvf3. To determine whether activation of the Pvr pathway in hemocytes alone is sufficient for hemocyte migration, we expressed pvrCA in the hemocytes of pvr mutants. The pvr receptor mutant is a null allele with a severe truncation at the first immunoglobulin domain (19), whereas for the PvrCA receptor, λ dimerization motifs replace the external ligand-binding domain and promote constitutive receptor coupling and downstream signaling (16). We followed the migration of GFP positive hemocytes that express pvrCA in pvr mutant embryos (pvr,crq>pvrCA, Fig. 6). We found that hemocyte-specific expression of the PvrCA receptor in pvr mutants was sufficient to restore the posterior migration of ventral hemocytes (Fig. 6, third column). Intriguingly, we found that expression of PvrCA partially restored transition across the VNC in the anterior, but not posterior of the embryo. Finally, we found that hemocyte-restricted engagement of Pvr signals did not restore invasion of the extended germband by pvr mutant hemocytes in stage 12 embryos (Fig. 6, first column). These findings demonstrate that the posterior migration of embryonic hemocytes does not require sensing of environmental Pvf ligands to guide migration, and that Pvr pathway activation through ligand binding domains is required for the invasive migration of hemocytes.

FIGURE 6.

Hemocyte behavior in pvr mutant embryos that express a constitutively active Pvr. Hemocytes were visualized by eGFP expression (green in Merge) and Armadillo (β-Catenin) was visualized by antibody labeling (red in Merge). The boxed regions were visualized at higher magnification in the lower three panels. Scale bars represent 50 μm in the whole embryo panels and 25 μm in high magnification panels. UAS-mCD8-GFP/+;pvr,crqGAL4/pvr,UAS-pvrCA (pvr,crq>pvrCA) embryos are shown. The dashed yellow line indicates the edge of the retracting germband. White brackets demarcate axon bundles of the ventral nerve cord.

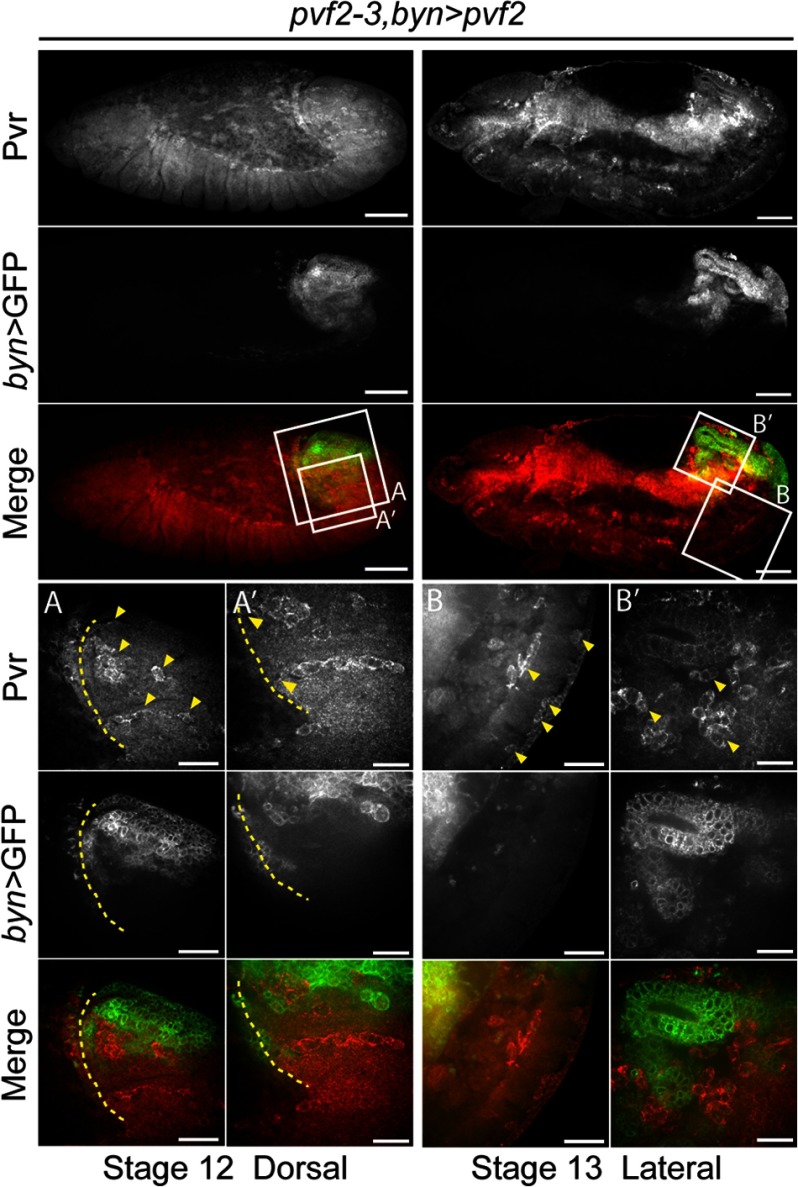

Expression of Pvf2 in the Germband Epithelium Restores Invasive Migration of Hemocytes in pvf2–3 Mutants

Our findings suggest that hemocyte extrinsic Pvf ligands are required for invasive hemocyte migration. To further test this, we expressed Pvf2 in the germband epithelium of pvf2–3 mutants (Fig. 7). Specifically, we expressed Pvf2 in the hindgut, which forms the terminal epithelial barrier of the extended germband through which hemocytes invade. To visualized hemocytes, we used a Pvr-specific antibody. The Pvr antibody is a reliable approach to detect hemocytes, as Pvr is highly expressed on embryonic hemocytes (9, 19, 41). We found that hindgut-restricted expression of Pvf2 restored hemocyte invasion of the germband in pvf2–3 mutants (Fig. 7, first and second columns). In stage 13 embryos, we found hemocytes interspersed around the GFP-positive hindgut epithelium and also hemocytes with GFP-positive inclusions in regions of the ventral posterior (Fig. 7, third and fourth columns). Together, these observations suggest that Pvf expression in the germband epithelium is essential for hemocyte invasive migration, but that Pvfs are dispensable as guidance cues for hemocyte migration to these tissues.

FIGURE 7.

Germband-restricted Pvf2 expression restores hemocyte invasive migration in pvf2–3 mutants. A brachyenteron (byn) pattern of Pvf2 expression is visualized by GFP (green in Merge). Hemocytes are visualized by antibody labeling of Pvr (red in Merge). The boxed regions were visualized at higher magnifications in the lower three panels. Scale bars represent 50 μm in whole embryo panels, 25 μm in A and B) and 15 μm in A′ and B′ panels. UAS-mCD8-GFP/+;pvf2–3,UAS-pvf2/pvf2–3;bynGAL4/+ (pvf2–3,byn>pvf2) embryos are shown. The dashed yellow line indicates the edge of the retracting germband. Arrowheads in A indicate hemocytes in the germband and at the site of invasion into the germband (A′). Arrowheads in B indicate hemocytes in the ventral posterior and in B′ hemocytes surrounding the developing hindgut.

DISCUSSION

Summary of This Report

Previous studies implicated the Pvr signal transduction pathway in a number of critical embryonic events, such as the control of hemocyte size (25), the provision of trophic (9) and migratory cues (12, 13) to hemocytes, and the control of organ morphogenesis in hemocyte- dependent (20, 22, 29) and -independent manners (28, 30, 31). The role of the Pvr axis in hemocyte migration is unclear with apparently contradictory studies indicating that pvf2 and pvf3 are essential (13), or that the Pvr pathway is dispensable for hemocyte migration (9). Direct examination of the requirements for pvf2 and pvf3 in embryogenesis are hindered by the absence of mutations in the two. To address this issue, we generated a genomic deletion that disrupts expression of pvf2 and pvf3. We confirmed that pvf2 and pvf3 provide essential trophic signals to hemocytes and established that simultaneous loss of pvf2 and pvf3 is embryonic lethal. In addition, we demonstrated that pvf2 and pvf3 do not provide chemotactic cues to guide the posterior migration of newly formed hemocytes. Instead, our data establish a novel role for pvf2 and pvf3 in controlling the invasion of embryonic epithelia by migratory hemocytes.

Requirements for pvf2 and pvf3 in Embryonic Hematopoiesis

Several lines of evidence confirm that the pvf2–3 mutant phenotypes presented in this report are a direct consequence of the depleted expression of pvf2 and pvf3. On a molecular level, the deletion removes almost the entire coding region of pvf3 and the promoter region of pvf2. We confirmed that homozygous mutants have severely diminished pvf2 expression and fail to express pvf3. We showed that a separate genomic deficiency that spans pvf2 and pvf3 fails to complement the pvf2–3 mutant phenotype. Phenotypically, the defects in pvf2–3 mutant embryos resemble pvr mutants. Specifically, pvf2–3 and pvr mutants exhibit anterior hemocyte aggregates, greatly diminished hemocyte numbers, and a block in germband invasion by embryonic hemocytes (9, 12). Finally, we found that hemocyte-restricted expression of pvf2, pvrCA, or RasV12 rescued the homozygous lethality of pvf2–3 mutants. Together our data indicate that pvf2 and pvf3 perform essential hemocyte-specific functions during embryonic development. We believe that Pvf2 and Pvf3 act in a redundant manner, as expression of pvf2 alone rescues the pvf2–3 defects described here. Rescue experiments with pvf3 are required to fully validate this hypothesis.

pvf2 and pvf3 Control Embryonic Hemocyte Survival

We observed a marked reduction in hemocyte numbers in pvf2–3 mutants and showed that the remaining anterior hemocyte population is engorged with apoptotic corpses. These findings are reminiscent of pvr mutants, which become heavily engorged through cannibalistic phagocytosis due to disruptions in survival signals that sustain hemocytes (9). Our observations suggest that Pvf2 and Pvf3 provide the necessary trophic inputs through Pvr to maintain the hemocyte pool. We confirmed this through the restoration of pvf2–3 hemocyte numbers to wild-type levels by hemocyte-specific expression of pvf2. However, we noted differences in the severity of certain hemocyte defects in pvf2–3 and pvr mutants. The anterior aggregation of hemocytes was more pronounced in pvr mutants than in pvf2–3 mutants. These observations support previous speculation that pvf1 contributes to hemocyte survival signaling at early stages of embryogenesis (13). As hemocyte-restricted expression of p35 or activation of the Pvr pathway is sufficient to revert the lethality of the pvf2–3 mutation, we conclude that the essential embryonic functions of the Pvf-Pvr axis are restricted to the hemocyte population.

Re-evaluation of Pvf2 and Pvf3 Roles in Hemocyte Migration

There is a substantial body of evidence that supports roles for the Pvf-Pvr axis in the control of developmental migrations. For example, Pvf1 guides border cell migration during oogenesis (16, 32) and a similar guidance mechanism is described for Pvf1 in larval epidermal cell migration during wound closure (33). A number of studies suggested that Pvf2 and Pvf3 act as guidance molecules during the developmental migration of embryonic hemocytes (12, 13, 29). Specifically, Pvf2 and Pvf3 are thought to serve as chemoattractants that guide Pvr-expressing hemocytes out of the head and along defined anterior to posterior routes in the developing embryo (13). This role is supported by the restricted spatial and temporal expression patterns of pvf2 and pvf3 in the VNC and pvf2 in the dorsal vessel, which coincide with defined routes of hemocyte migration (13). This hypothesis also overlaps with the respective roles of PDGF and VEGF in fibroblast (37) and early blood cell chemotaxis (38). However, our initial studies suggested that posterior migration of hemocytes along the VNC and the dorsal vessel is undisturbed in pvf2–3 mutant embryos. When we replenished hemocyte numbers in pvf2–3 mutants through hemocyte-specific expression of pvf2, we observed a complete restoration of anterior to posterior hemocyte migration. If the supply of Pvf2 is limited to hemocytes in the rescue experiments, our data argue that pvf2 and pvf3 do not act as extrinsic guidance molecules for the posterior migration of embryonic hemocytes. However, we considered that if the pvf2–3 mutation does not entirely ablate pvf2 expression, it is imaginable that the residual Pvf2 produced is sufficient to guide posterior hemocyte migration. We therefore tested this hypothesis in an experiment where we induced ligand-independent activation of the Pvr pathway in the hemocytes of embryos that were otherwise deficient for pvr function. Our studies showed that restoration of Pvr activity to hemocytes that are insensitive to guidance cues from Pvf ligands completely restored the posterior migration of embryonic hemocytes. These findings agree with the observed hemocyte distribution pattern in late stage pvr mutant embryos rescued with PvrCA (9) and conclusively establish that Pvf2 and Pvf3 do not act as chemoattractants for the posterior migration of embryonic hemocytes.

We believe that the migratory defects previously described in embryos injected with dsRNA that targets pvf2 and pvf3 are a consequence of the reduced hemocyte numbers caused by a block in trophic signaling (12, 13). However, from our data we cannot exclude Pvf roles in local hemocyte chemotaxis nor the possibility that Pvfs, like many conserved growth factors, may act as chemokinetic molecules that sensitize hemocytes to other chemoattractants (39). However, recent evidence of a genetic interaction between Pvr and a WASP family member required for the efficient processing of hemocyte phagosome material hints at an alternative explanation for Pvr pathway mutant phenotypes (40). This study showed that disruptions to the ability of hemocytes to process phagocytosed apoptotic corpses causes extreme vacuolation of hemocyte cytoplasm and consequently prevents hemocyte migration. Our observation of heavily vacuolated cytoplasm in pvf2–3 and pvr mutants draws an intriguing correlation between phagosome processing and Pvf-Pvr signaling.

Hemocyte-Extrinsic Cues Are Required for Invasive Migration

During embryonic development, a subset of hemocytes leaves open migratory routes and penetrates epithelial barriers to invade and populate embryonic tissues. Previous studies described an absence of hemocytes in the retracted germband of pvr mutants (10, 12). We also noticed an absence of posterior hemocytes in pvf2–3 mutants and traced this defect to a failure of hemocytes to invade the extended germband. The invasive potential of a cell depends on its motile potential and ability to breach tissue barriers. Our examination of hemocytes in fixed and live pvf2–3 mutant embryos revealed that hemocytes do not exhibit a loss of motile potential, as mutant hemocytes capably position themselves at presumptive sites of invasion. Furthermore, we showed that hemocyte positioning at defined sites of entry into the germband was intact not only in pvf2–3 mutants, but also pvr mutants. We also showed that p35 or PvrCA expression in hemocytes did not restore invasive migration in pvf2–3 mutants. This indicates that Pvf-Pvr survival signals are not sufficient to restore invasive migration. We believe these observations indicate that Pvf-Pvr signals are essential to coordinate the process of invasion, whereas other guidance cues attract hemocytes to the germband interface. We note that the epithelial expression patterns of pvf2 and pvf3 are consistent with such a function (12, 41).

We found that expression of pvf2 in the hemocytes of pvf2–3 mutants does not rescue invasion of the extended germband by embryonic hemocytes, whereas expression of pvf2 in the germband epithelia does restore the hemocyte invasive migration. These findings could be interpreted as evidence of a germband-restricted Pvf-Pvr-mediated control of epithelial permeability. However, previous studies established that hemocyte-specific expression of wild-type Pvr restores hemocyte invasion in pvr mutant embryos (9). Therefore, these findings support a mechanism where epithelial Pvfs engage Pvr in hemocytes to orchestrate the polarization of the invasion machinery of hemocytes toward the proximal interface of the epithelium. Uniform activation of the Pvr pathway does not restore invasive migration in pvf2–3 and pvr mutant embryos. We speculate that PvrCA unlike wild-type Pvr interferes with the essential hemocyte polarization toward the site of invasion. Requirements for polarization during invasive migration are supported by evidence of Pvr-induced invasive extensions in border cell migration (42) and in recent work that shows a requirement for RhoL in hemocytes to promote Rap1 localization and increased integrin affinity at the leading edge of the invading hemocytes (23). Also, Pvr controls actin accumulation through Rac and the DOCK180 homolog Mbc in border cell migration (16). Whether Pvr signaling contributes to adhesion through RhoL activity or controls actin-rich extension through Rac and Mbc in hemocyte invasion is an intriguing avenue for future studies.

In summary, our data support the involvement of the Pvr pathway in hemocyte survival and establish Pvf2 and Pvf3 as essential trophic signaling molecules for hemocyte survival. In addition, we provide evidence that pvf2 and pvf3 are not chemoattractants that guide the posterior migration of hemocytes from the head of stage 11 embryos. Instead, we uncover a novel hemocyte-extrinsic role for pvf2 and pvf3 in invasive migration that is independent of their survival function. A role for Pvfs in trans-epithelial migration is intriguingly similar to established VEGF roles in vascular permeability. For example, VEGFs induce the formation of small pores or fenestrae on endothelial cells, calveolae for intra-endothelial protein transport, and channels or vesiculo-vacuolar organelles for passage of material through endothelial cells (43). VEGFs also support cellular passage across endothelial barriers, as VEGFR-2 directly phosphorylates VE-cadherin, β-, γ-, and p120-catenins, causing the dissolution of adherens junctions (44). Our observation of Pvf-supported invasive hemocyte migration and separate work that shows embryonic hemocytes track toward wounds along hydrogen peroxide gradients (45) support the Drosophila embryo as a compelling model to study VEGF contributions to detrimental edemas during ischemic injury (46) or PDGF-induced VEGF roles in tumor growth and vascular leakage that promote extravasation and metastasis (5, 47, 48). Given the prolific occurrence of these disease pathologies and the potential of targeted therapeutics, future studies to dissect the regulation of Pvf-Pvr signaling roles in hemocyte invasion will be invaluable to extend our understanding of the physiological and pathological roles of PDGF and VEGF roles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pernille Rørth for the pvrCA fly line and Helen Skaer for the bynGAL4 fly line used in this study. Additional flies lines were obtained through the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and the Harvard Exelixis Collection. The anti-Pvr antibody was kindly provided by Ben-Zion Shilo. The anti-armadillo and anti-DCAD2 (DE-Cadherin) monoclonal antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD, National Institutes of Health, and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA. We gratefully acknowledge the extensive microscopy support from Dr. Stephen Ogg and the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry core imaging service, the Cell Imaging Centre, University of Alberta.

This work was supported in part by Canadian Institute for Heath Research Grant MOP 77746 and grants from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) and Alberta Innovates Heath Solutions (AIHS).

This article contains supplemental Videos S1–S4.

- Pvr

- PDGF/VEGF-receptor related

- Pvf

- PDGF- and VEGF-related factor

- VNC

- ventral nerve cord.

REFERENCES

- 1. Oostendorp R. A., Gilfillan S., Parmar A., Schiemann M., Marz S., Niemeyer M., Schill S., Hammerschmid E., Jacobs V. R., Peschel C., Götze K. S. (2008) Oncostatin M-mediated regulation of KIT-ligand-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling maintains hematopoietic repopulating activity of Lin-CD34+CD133+ cord blood cells. Stem Cells 26, 2164–2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seita J., Weissman I. L. (2010) Hematopoietic stem cell. Self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2, 640–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zlotoff D. A., Bhandoola A. (2011) Hematopoietic progenitor migration to the adult thymus. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1217, 122–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sahin A. O., Buitenhuis M. (2012) Molecular mechanisms underlying adhesion and migration of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Adh. Migr. 6, 39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerber H. P., Ferrara N. (2003) The role of VEGF in normal and neoplastic hematopoiesis. J. Mol. Med. 81, 20–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kondo M., Wagers A. J., Manz M. G., Prohaska S. S., Scherer D. C., Beilhack G. F., Shizuru J. A., Weissman I. L. (2003) Biology of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors. Implications for clinical application. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 759–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Evans C. J., Hartenstein V., Banerjee U. (2003) Thicker than blood. Conserved mechanisms in Drosophila and vertebrate hematopoiesis. Dev. Cell 5, 673–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fossett N., Schulz R. A. (2001) Functional conservation of hematopoietic factors in Drosophila and vertebrates. Differentiation 69, 83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brückner K., Kockel L., Duchek P., Luque C. M., Rørth P., Perrimon N. (2004) The PDGF/VEGF receptor controls blood cell survival in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 7, 73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heino T. I., Kärpänen T., Wahlström G., Pulkkinen M., Eriksson U., Alitalo K., Roos C. (2001) The Drosophila VEGF receptor homolog is expressed in hemocytes. Mech. Dev. 109, 69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoch R. V., Soriano P. (2003) Roles of PDGF in animal development. Development 130, 4769–4784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cho N. K., Keyes L., Johnson E., Heller J., Ryner L., Karim F., Krasnow M. A. (2002) Developmental control of blood cell migration by the Drosophila VEGF pathway. Cell 108, 865–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wood W., Faria C., Jacinto A. (2006) Distinct mechanisms regulate hemocyte chemotaxis during development and wound healing in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 173, 405–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andrae J., Gallini R., Betsholtz C. (2008) Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 22, 1276–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Traver D., Zon L. I. (2002) Walking the walk. Migration and other common themes in blood and vascular development. Cell 108, 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duchek P., Somogyi K., Jékely G., Beccari S., Rørth P. (2001) Guidance of cell migration by the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor. Cell 107, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meister M., Lagueux M. (2003) Drosophila blood cells. Cell Microbiol. 5, 573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tepass U., Fessler L. I., Aziz A., Hartenstein V. (1994) Embryonic origin of hemocytes and their relationship to cell death in Drosophila. Development 120, 1829–1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sears H. C., Kennedy C. J., Garrity P. A. (2003) Macrophage-mediated corpse engulfment is required for normal Drosophila CNS morphogenesis. Development 130, 3557–3565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Evans I. R., Hu N., Skaer H., Wood W. (2010) Interdependence of macrophage migration and ventral nerve cord development in Drosophila embryos. Development 137, 1625–1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fessler L. I., Nelson R. E., Fessler J. H. (1994) Drosophila extracellular matrix. Methods Enzymol. 245, 271–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olofsson B., Page D. T. (2005) Condensation of the central nervous system in embryonic Drosophila is inhibited by blocking hemocyte migration or neural activity. Dev. Biol. 279, 233–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siekhaus D., Haesemeyer M., Moffitt O., Lehmann R. (2010) RhoL controls invasion and Rap1 localization during immune cell transmigration in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 605–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paladi M., Tepass U. (2004) Function of Rho GTPases in embryonic blood cell migration in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 117, 6313–6326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sims D., Duchek P., Baum B. (2009) PDGF/VEGF signaling controls cell size in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 10, R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Börklund M., Taipale M., Varjosalo M., Saharinen J., Lahdenperä J., Taipale J. (2006) Identification of pathways regulating cell size and cell-cycle progression by RNAi. Nature 439, 1009–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Munier A. I., Doucet D., Perrodou E., Zachary D., Meister M., Hoffmann J. A., Janeway C. A., Jr., Lagueux M. (2002) PVF2, a PDGF/VEGF-like growth factor, induces hemocyte proliferation in Drosophila larvae. EMBO Rep. 3, 1195–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harris K. E., Schnittke N., Beckendorf S. K. (2007) Two ligands signal through the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor to ensure proper salivary gland positioning. Mech. Dev. 124, 441–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bunt S., Hooley C., Hu N., Scahill C., Weavers H., Skaer H. (2010) Hemocyte-secreted type IV collagen enhances BMP signaling to guide renal tubule morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 19, 296–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Macías A., Romero N. M., Martín F., Suárez L., Rosa A. L., Morata G. (2004) PVF1/PVR signaling and apoptosis promotes the rotation and dorsal closure of the Drosophila male terminalia. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 1087–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishimaru S., Ueda R., Hinohara Y., Ohtani M., Hanafusa H. (2004) PVR plays a critical role via JNK activation in thorax closure during Drosophila metamorphosis. EMBO J. 23, 3984–3994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McDonald J. A., Pinheiro E. M., Montell D. J. (2003) PVF1, a PDGF/VEGF homolog, is sufficient to guide border cells and interacts genetically with Taiman. Development 130, 3469–3478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu Y., Brock A. R., Wang Y., Fujitani K., Ueda R., Galko M. J. (2009) A blood-borne PDGF/VEGF-like ligand initiates wound-induced epidermal cell migration in Drosophila larvae. Curr. Biol. 19, 1473–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bond D., Foley E. (2012) Autocrine platelet-derived growth factor-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-related (Pvr) pathway activity controls intestinal stem cell proliferation in the adult Drosophila midgut. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 27359–27370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parks A. L., Cook K. R., Belvin M., Dompe N. A., Fawcett R., Huppert K., Tan L. R., Winter C. G., Bogart K. P., Deal J. E., Deal-Herr M. E., Grant D., Marcinko M., Miyazaki W. Y., Robertson S., Shaw K. J., Tabios M., Vysotskaia V., Zhao L., Andrade R. S., Edgar K. A., Howie E., Killpack K., Milash B., Norton A., Thao D., Whittaker K., Winner M. A., Friedman L., Margolis J., Singer M. A., Kopczynski C., Curtis D., Kaufman T. C., Plowman G. D., Duyk G., Francis-Lang H. L. (2004) Systematic generation of high-resolution deletion coverage of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nat. Genet. 36, 288–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Franc N. C., Dimarcq J. L., Lagueux M., Hoffmann J., Ezekowitz R. A. (1996) Croquemort, a novel Drosophila hemocyte/macrophage receptor that recognizes apoptotic cells. Immunity 4, 431–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seppä H., Grotendorst G., Seppä S., Schiffmann E., Martin G. R. (1982) Platelet-derived growth factor in chemotactic for fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 92, 584–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shalaby F., Rossant J., Yamaguchi T. P., Gertsenstein M., Wu X. F., Breitman M. L., Schuh A. C. (1995) Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient mice. Nature 376, 62–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Petrie R. J., Doyle A. D., Yamada K. M. (2009) Random versus directionally persistent cell migration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 538–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Evans I. R., Ghai P. A., Urbancic V., Tan K. L., Wood W. (2013) SCAR/WAVE-mediated processing of engulfed apoptotic corpses is essential for effective macrophage migration in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 20, 709–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rosin D., Schejter E., Volk T., Shilo B. Z. (2004) Apical accumulation of the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor ligands provides a mechanism for triggering localized actin polymerization. Development 131, 1939–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fulga T. A., Rørth P. (2002) Invasive cell migration is initiated by guided growth of long cellular extensions. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 715–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weis S. M., Cheresh D. A. (2005) Pathophysiological consequences of VEGF-induced vascular permeability. Nature 437, 497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Esser S., Lampugnani M. G., Corada M., Dejana E., Risau W. (1998) Vascular endothelial growth factor induces VE-cadherin tyrosine phosphorylation in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 111, 1853–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moreira S., Stramer B., Evans I., Wood W., Martin P. (2010) Prioritization of competing damage and developmental signals by migrating macrophages in the Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 20, 464–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van Bruggen N., Thibodeaux H., Palmer J. T., Lee W. P., Fu L., Cairns B., Tumas D., Gerlai R., Williams S. P., van Lookeren Campagne M., Ferrara N. (1999) VEGF antagonism reduces edema formation and tissue damage after ischemia/reperfusion injury in the mouse brain. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 1613–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Saharinen P., Eklund L., Pulkki K., Bono P., Alitalo K. (2011) VEGF and angiopoietin signaling in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Trends Mol. Med. 17, 347–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bergers G., Song S., Meyer-Morse N., Bergsland E., Hanahan D. (2003) Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1287–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.