Background: Yeast sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) are proteolytically activated by a mechanism distinct from that of mammals.

Results: Site-directed mutagenesis studies define structural requirements for yeast SREBP cleavage.

Conclusion: Yeast SREBP cleavage requires a novel conserved glycine-leucine motif.

Significance: Understanding SREBP structural requirements aids mechanistic dissection of SREBP cleavage essential for fungal pathogenesis.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Lipids, Protein Motifs, Sterol, Transcription Factors, Fungal Pathogenesis, Glycine-Leucine Motif, Proteolytic Cleavage, SREBP

Abstract

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) are central regulators of cellular lipid synthesis and homeostasis. Mammalian SREBPs are proteolytically activated and liberated from the membrane by Golgi Site-1 and Site-2 proteases. Fission yeast SREBPs, Sre1 and Sre2, employ a different mechanism that genetically requires the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase complex for cleavage activation. Here, we established Sre2 as a model to define structural requirements for SREBP cleavage. We showed that Sre2 cleavage does not require the N-terminal basic helix-loop-helix zipper transcription factor domain, thus separating cleavage of Sre2 from its transcription factor function. From a mutagenesis screen of 94 C-terminal residues of Sre2, we isolated 15 residues required for cleavage and further identified a glycine-leucine sequence required for Sre2 cleavage. Importantly, the glycine-leucine sequence is located at a conserved distance before the first transmembrane segment of both Sre1 and Sre2 and cleavage occurs in between this sequence and the membrane. Bioinformatic analysis revealed a broad conservation of this novel glycine-leucine motif in SREBP homologs of ascomycete fungi, including the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus where SREBP is required for virulence. Consistent with this, the sequence was also required for cleavage of the oxygen-responsive transcription factor Sre1 and adaptation to hypoxia, demonstrating functional conservation of this cleavage recognition motif. These cleavage mutants will aid identification of the fungal SREBP protease and facilitate functional dissection of the Dsc E3 ligase required for SREBP activation and fungal pathogenesis.

Introduction

Cellular lipid synthesis and homeostasis are centrally regulated by sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP)2 transcription factors (1, 2). These membrane-bound transcription factors contain two transmembrane segments and are inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in a hairpin orientation with the N and C termini projecting into the cytosol (2). The SREBP N terminus contains a basic-helix-loop-helix zipper (bHLH-zip) transcription factor domain that is required for DNA binding and transcriptional activation of its target genes required for cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis (2). In mammalian cells following sterol-regulated transport to the Golgi, SREBPs are activated through sequential cleavage by the Golgi-resident Site-1 protease and Site-2 protease. Specifically, Site-1 protease is a subtilisin/kexin-like, serine protease that cleaves in the SREBP luminal loop, splitting the molecule in half. This first cleavage event enables the Site-2 protease zinc metalloprotease to cleave within the first transmembrane segment (TM1) and release the soluble SREBP N-terminal transcription factor from the membrane (3). In mammals, Site-2 protease is essential for membrane release and SREBP activity.

Fungal SREBPs have been characterized in Schizosaccharomyces pombe and the human pathogens Cryptococcus neoformans and Aspergillus fumigatus (4–9). Collectively, these studies revealed that fungal SREBPs are oxygen-responsive transcription factors required for adaptation to hypoxia and fungal pathogenesis (10). Fission yeast S. pombe contains two SREBP homologs: Sre1 and Sre2 (4). Sre1 is an oxygen-responsive transcription factor that is cleaved under low oxygen to promote adaptation to hypoxia (4). In contrast, cleavage of the less well characterized Sre2 occurs in the presence of oxygen and is unregulated. This feature of Sre2 makes it a useful model to study structural requirements for cleavage under routine cell culture conditions rather than low oxygen (11, 12).

Fission yeast lacks an identifiable Site-2 protease homolog, suggesting a different mechanism for SREBP cleavage (2). Previously, we showed that Sre1 is cleaved at a cytosolic position, instead of within TM1, consistent with Site-2 protease-independent cleavage. Genetic evidence revealed that both Sre1 and Sre2 cleavage requires a multisubunit Golgi-localized E3 ligase, which we named Dsc (defective for SREBP cleavage) (11, 12). The Dsc E3 ligase, composed of Dsc1 through Dsc5, is a stable membrane complex containing the RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligase Dsc1 (11). Consistent with its role in SREBP activation, A. fumigatus Dsc E3 ligase is also required for fungal virulence (13).

Despite genetic evidence of cleavage requirements for fission yeast SREBPs, the mechanism of how the Dsc E3 ligase mediates cleavage and the responsible fungal protease remains unknown. To aid uncoupling mechanistic steps of yeast SREBP cleavage, we dissected the cleavage mechanism from a substrate perspective. In the present study, we defined the structural requirements for Sre2 cleavage using serial truncation analysis and a site-directed mutagenesis screen. We isolated 15 single amino acid mutations in Sre2 that prevent cleavage. In addition, we identified a conserved, 7-amino acid glycine-leucine sequence in Sre2 required for cleavage. Notably, cleavage occurs in between the glycine-leucine sequence and the membrane. Importantly, the glycine-leucine sequence was required for Sre1 cleavage, confirming the function of this conserved cleavage recognition motif. This motif is broadly conserved across ascomycete fungi, whose members lack homologs of the intramembrane-cleaving Site-2 protease present in mammals. These findings demonstrate a role for this conserved glycine-leucine motif in fungal SREBP cleavage activation, provide tools for dissecting the mechanism of SREBP cleavage, and identify the SREBP C terminus as a target for antifungal therapy for pathogenic fungi that contain a relevant conserved SREBP pathway (5, 7, 9, 14, 15).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

We obtained yeast extract, peptone, and agar from BD Biosciences; Edinburgh minimal medium from MP Biomedical; oligonucleotides from Integrated DNA Technologies; alkaline phosphatase from Roche Applied Science; and HRP-conjugated, affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Prestained protein standards were from Bio-Rad.

Strains and Media

Wild-type haploid S. pombe KGY425 and derived strains were grown to log phase at 30 °C in YES medium (5 g/liter yeast extract plus 30 g/liter glucose and supplements; 225 mg/liter each of adenine, uracil, leucine, histidine, and lysine) or Edinburgh minimal medium plus supplements unless otherwise indicated. Yeast transformations were performed as described previously (4). Strains used in this study were derived using standard genetic techniques and are described in supplemental Table 3 (16).

Antibodies

We obtained anti-FLAG M2 from Sigma. Antisera to Sre1 (aa 1–260) and Sre2 (aa 1–426) polyclonal IgG generated against the cytosolic N terminus of fission yeast Sre1 and Sre2 have been described previously (4).

Plasmids

RCP90 and RCP92 encode truncated, N-terminal fragments of Sre2 (aa 423–697 and 423–712) under control of the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) promoter derived from pSLF101 (17). These plasmids were constructed by mutation of the appropriate codons to stop codons using QuikChange II XL mutagenesis. pCaMV-3×FLAG truncation plasmids listed in Fig. 1 were generated by truncation of the appropriate amino acids in Sre2 using QuikChange II XL mutagenesis.

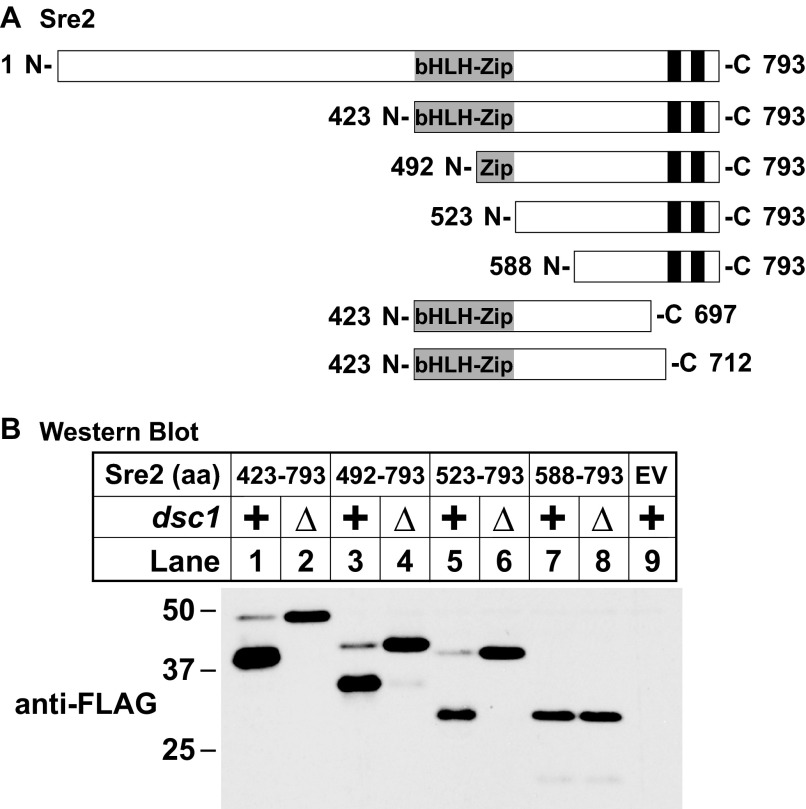

FIGURE 1.

Establishing the minimal Sre2 sequence required for cleavage. A, diagrams for serial truncations of Sre2. bHLH-zip and predicted transmembrane domains are indicated by gray and black boxes, respectively. B, serial truncation analysis of Sre2. Western blot was probed with anti-FLAG IgG of whole cell lysates. Wild-type or dsc1Δ cells carrying FLAG-tagged N-terminal truncations of Sre2 or empty vector (EV) were grown in minimal medium lacking leucine for 16 h. FLAG epitope is appended at the N terminus of truncated Sre2 to monitor cleavage. All strains are sre2Δ.

Sre1 integrating plasmid contains the sre1+ coding sequence flanked by 800 bp of upstream genomic sequence and 500 bp of downstream genomic sequence, with a his3+ marker for chromosomal reconstitution of histidine auxotrophy (18). Plasmids containing sre1 wild type and mutants (pES219, RCP365–RCP369) were linearized with AscI and transformed into sre1Δ strain and selected for on minimal medium lacking histidine to generate strains carrying integrated wild-type and mutant alleles of sre1 at the his3+ locus.

Low Oxygen Cell Culture

For Sre1 hypoxic cleavage assays, cells growing exponentially in YES medium were collected by centrifugation. Oxygenated medium was removed by aspiration, and cells were resuspended in deoxygenated YES medium under anaerobic conditions inside a Ruskinn In vivo2 400 hypoxic work station (Biotrace, Inc.). Anaerobic conditions were achieved in the work station using 10% hydrogen gas balanced with nitrogen in the presence of palladium catalyst. YES medium was deoxygenated by preincubation for >24 h in the hypoxic work station. After resuspension, cultures were agitated at 30 °C, harvested by centrifugation, washed with water, and frozen as cell pellets in liquid nitrogen.

Cleavage Assays

For Sre1 and Sre2 cleavage assays, whole cell lysates were prepared for immunoblotting analysis. Protein preparation and immunoblotting for S. pombe experiments were described previously (4). For Sre1 and Sre2, whole cell lysates were extracted and treated with alkaline phosphatase as described previously (4). For Sre2 model substrate, anti-FLAG M2 antibody was used to detect the precursor (P) and the cleaved N-terminal nuclear form (N). For Sre2-GFP, anti-Sre2 polyclonal antibody was used to detect the precursor (P) and cleaved N-terminal nuclear form (N).

Fluorescence Microscopy

A plasmid expressing GFP-sre2 from the thiamine repressible nmt* promoter (pAH230) was described previously (12). Cleavage mutants were generated in this plasmid using QuikChange II XL mutagenesis. Live cells were imaged on 2% agarose pads using a Zeiss Axioskop microscope equipped with fluorescence and Nomarski optics (Zeiss). Images were captured using a Photometrics Cool Snap EZ CCD camera and IP Lab Spectrum software (Biovision Technologies, Inc.).

Mutagenesis Screen of Sre2 Model Substrate

Sre2 model substrate was expressed from a plasmid containing a truncated form of Sre2 (aa 423–793), tagged with a 3×FLAG epitope at its N terminus, under control of the constitutive CaMV promoter. pCaMV mutant plasmids listed in Table 1 and Fig. 3 were generated by mutation of the appropriate codons using QuikChange II XL mutagenesis. In the model substrate, 94 aa at the distal end of Sre2 (aa 676–793), which spans the conserved glycine-leucine motif and two transmembrane segments, were analyzed for cleavage. These mutants were first mutated in groups of doublets or triplets. For the mutants that demonstrated cleavage defects, individual residues were mutated from each group to analyze the contribution to Sre2 cleavage defect. Cleavage defects in model substrate were confirmed by generating the respective mutants in plasmids expressing full-length GFP-sre2 under the control of the constitutive CaMV promoter, as well as GFP-sre2 expressed from the thiamine repressible promoter nmt* (and/or GFP-model substrate fusion protein driven by CaMV promoter). These plasmids were used for examining cleavage and localization, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Sre2 model substrate mutants screened

| Cleavage of Sre2 model substrate mutants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Block (P>N) | Partial (P≈N) | Normal (N>P) |

| L678T | N679E | V677T |

| G680E | E685A | V682T |

| L681T | T686A | T691A/N692A |

| G683E | V687A/H688A | G697A |

| L684T | M689A/L690A | S699A |

| M704A | P693A | R701A |

| S705A | D694A | F702A/S703A |

| K743R | D695A | V706A/L707A |

| E755L | S698A | S710A/P711A |

| S765L | N700A | S712A/L713A |

| P767L | P708A | H714L/S715L |

| D770L | I709A | R718L/F719L |

| W771L | M731L/H732L | F726L |

| R778A | S751L | C728L/F729L |

| E788A | R753L | T736L |

| S760L | P737A/E738A | |

| F761L | T740A/L741A/R742A | |

| V766L | W744A/S746A | |

| Y769L | S747A/I748A/Y749A | |

| N773A | F752L | |

| Y774A | C756L | |

| N776A | V757L | |

| L777A | F758L | |

| L781A | F764L | |

| L787A | G772A | |

| L775A | ||

| G779A | ||

| K780R | ||

| L782A | ||

| L783A | ||

| E784A/L785A/N786A | ||

| S789A | ||

| G790A/V791A | ||

| T793A | ||

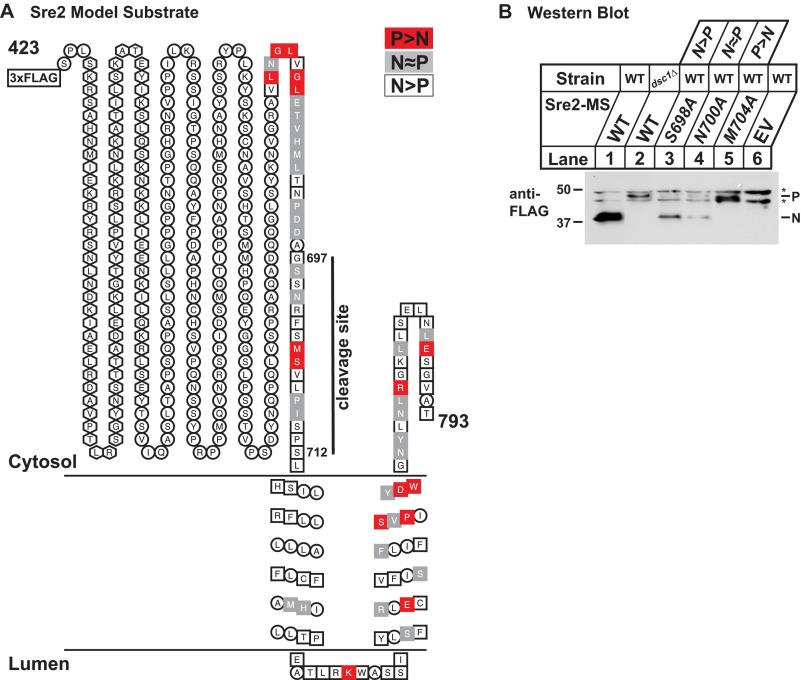

FIGURE 3.

Mutagenesis screen of Sre2 model substrate reveals sequence requirements for cleavage. A, diagram of predicted membrane topology and mutant classification for Sre2 model substrate (aa 423–793). 94 amino acids tested in mutagenesis screen are enclosed in squares. From these residues, mutants showing a robust block in cleavage (P>N) are indicated in red, mutants showing cleavage defect (N≈P) are indicated in gray, and residues showing normal cleavage (N>P) are indicated in white. Amino acid residues of bHLH-zip domain are enclosed in hexagons. B, Western blot probed with anti-FLAG IgG of lysates from sre2Δ cells expressing the indicated wild-type or mutant Sre2 model substrate. Each mutant defines a category of observed cleavage efficiency. Asterisks denote nonspecific cross-reactive bands.

Bioinformatics

Conservation of glycine-leucine motif of SREBPs was mined using a custom Perl script. In brief, SREBPs were isolated by protein sequence alignment using BLAST database version 2.2.25 downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). For each SREBP, coordinates of each transmembrane segment (TM) were predicted using TM-HMM software version 2.0, executed through a BioPerl module and confirmed with Phobius (19). Only SREBPs that contained one or more predicted TM(s) were used for downstream analysis. To define the consensus glycine-leucine conserved motif, a 50-amino acid stretch centered 55 aa before the first predicted TM was isolated for each SREBP. For all of the isolated 50-amino acid sequences, sequence similarity search was performed to reveal the conserved glycine-leucine motif. A sequence logo was generated using WebLogo 3 (20).

RESULTS

Minimal Sequence Required for Sre2 Cleavage

Sre2 is a 793-amino acid protein with two TM segments (aa 714–737 and 749–771) (Fig. 1A). To determine which region of Sre2 is required for Dsc-dependent cleavage, we generated serial N-terminal truncations of Sre2 and assayed cleavage of these mutants in whole cell extracts by immunoblotting (Fig. 1A). To monitor Sre2 cleavage events, we inserted a 3×FLAG epitope at the N terminus of Sre2 truncations, thereby allowing us to distinguish Sre2 precursor from Sre2 N-terminal cleaved form. Deletion of the N-terminal half of Sre2, aa 1–422, had no effect on cleavage. N-terminal truncated Sre2 (aa 423–793) showed a cleavage pattern similar to full-length Sre2 (12), with the majority of Sre2 in the cleaved form at steady state (Fig. 1B, lane 1). Importantly, this cleavage required Dsc1 (Fig. 1B, lane 2), the Golgi E3 ligase required for the cleavage activation of both Sre1 and Sre2 precursors (12). This result indicated that cleavage does not require Sre2 aa 1–422.

Further Sre2 truncations across the bHLH-zip domain (aa 426–516) demonstrated that this domain is also not required for cleavage (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 5), despite the requirement of this domain for DNA binding and transcription factor activity. Thus, the functions of Sre2 as a transcription factor and a substrate for Dsc-dependent cleavage are separable. Finally, Sre2 failed to cleave when we truncated Sre2 to aa 588 and the Sre2 precursor migrated at the same position in the presence or absence of dsc1 (Fig. 1B, lanes 7 and 8). Taken together, these results suggest that aa 1–522 including the bHLH-zip domain of Sre2 are not required for cleavage. However, sequences in the C-terminal portion of Sre2 are important for cleavage.

Cleavage of Sre2 Occurs in the Cytosol

Dsc-dependent cleavage of the oxygen-regulated Sre1 transcription factor occurs in the cytosol at a position ∼10 aa before the TM1 (12). Next, we mapped the cleavage site for Sre2. Because Sre2 cleavage occurs at a site close to its C terminus, Sre2 precursor and its cleaved nuclear form are not readily resolved by SDS-PAGE. Therefore, we chose to use an Sre2 model substrate, Sre2 aa 423–793 (hereafter, Sre2-MS), that is efficiently cleaved in a Dsc-dependent manner to analyze Sre2 sequences required for cleavage (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2). We verified that the N terminus of GFP-Sre2 aa 423–793 translocates to the nucleus, demonstrating that Sre2-MS is functionally imported after Dsc-dependent cleavage (data not shown). These data are consistent with studies on mammalian SREBP-2 showing that the bHLH-zip domain functions as a nuclear import signal (21).

Cleavage of mammalian SREBPs by Site-2 protease occurs within TM1 between a leucine and cysteine residue, both of which are not present in Sre2 (22). To estimate the position of Sre2 cleavage, we generated two C-terminal truncations of Sre2-MS encoding aa 423–697 and 423–712. These two size standards truncated Sre2-MS at cytosolic positions prior to the TM1 (Fig. 1A). Cleaved Sre2-MS migrated between the two C-terminal truncations (Fig. 2A, lane 4). Thus, Sre2 is cleaved between aa 697 and 712 in the cytosol, consistent with cytosolic cleavage of Sre1 (12). Notably, the cytosolic cleavage sites of Sre1 and Sre2 are equidistant (∼10 amino acids) from their respective first transmembrane segments. These results reinforce the observation that SREBP cleavage in S. pombe is mechanistically distinct from that in mammals, whereby cleavage occurs within TM1.

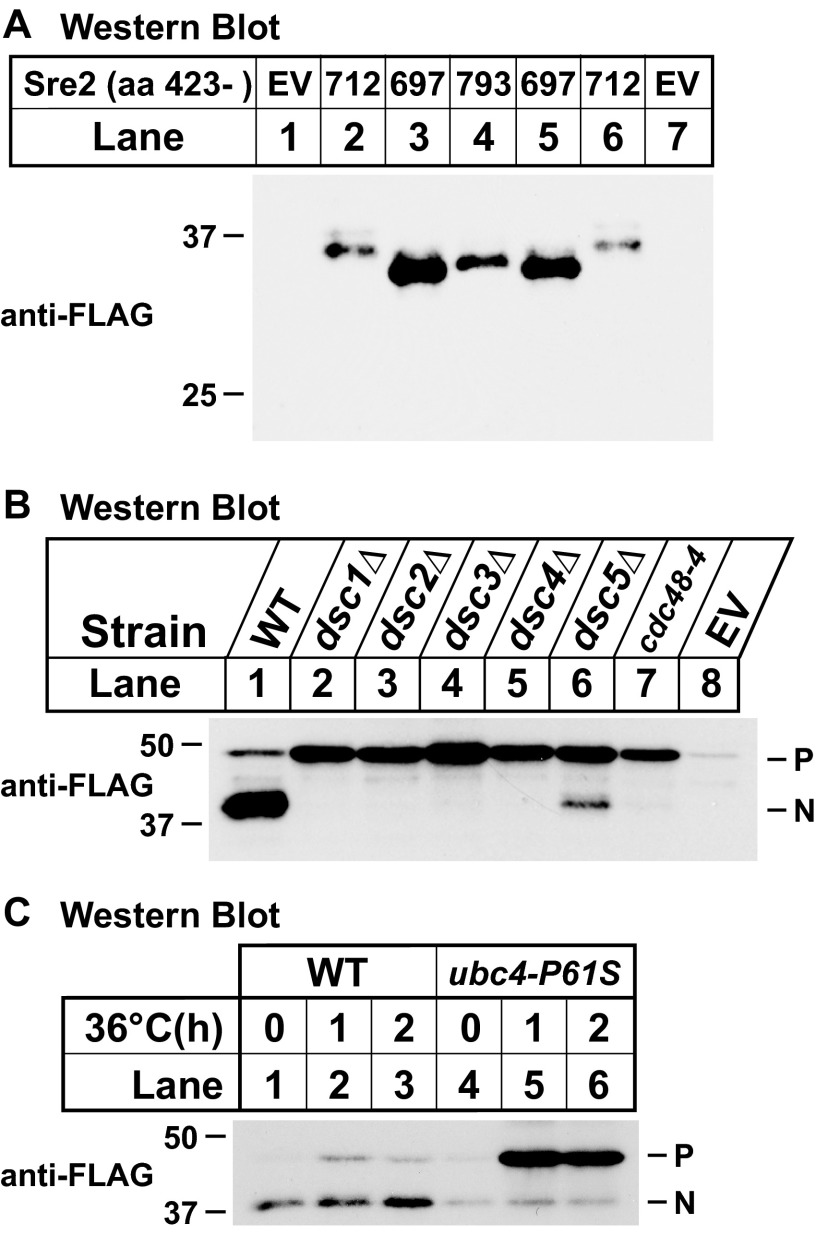

FIGURE 2.

Cleavage of Sre2 model substrate occurs in the cytosol and requires Dsc E3 ligase complex and E2 enzyme Ubc4. A, Western blot probed with anti-FLAG IgG of lysates from sre2Δ cells expressing wild-type Sre2 model substrate (MS) (aa 423–793) (lane 4), empty vector (EV, lane 1 or 7), or truncated versions of Sre2 (aa 423–697 or 423–712, lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). B, Western blot probed with anti-FLAG IgG of lysates from wild-type and indicated deletion or mutant strains. Strains carrying plasmids expressing Sre2-MS were grown in minimal medium lacking leucine for 16 h. C, Western blot probed with anti-FLAG IgG of lysates from wild-type and ubc4-P61S. Cells were grown to exponential phase at 25 °C and shifted to the non-permissive temperature of 36 °C for the indicated times. P and N, precursor and cleaved nuclear forms, respectively. All strains are sre2Δ.

Cleavage of Sre2 Model Substrate Requires Dsc E3 Ligase Complex, Cdc48 and E2 Enzyme Ubc4

Cleavage of Sre1 and Sre2 requires each of the subunits of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase complex Dsc1 through Dsc5, AAA-ATPase Cdc48, and the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc4 (11, 12). To investigate whether cleavage requirements of Sre2-MS parallel those of Sre1 and Sre2, we assayed cleavage of Sre2-MS in cells lacking each of these components. We found that Dsc1–Dsc4 were strictly required for Sre2-MS cleavage (Fig. 2B, lanes 2–5). In dsc5Δ cells, a small amount of Sre2-MS cleaved form was detectable (Fig. 2B, lane 6), consistent with partial requirement of dsc5 for cleavage of full-length Sre2 precursor (11). cdc48-4 contains a mutation (E325K) that lies in the Walker B motif in the AAA-ATPase domain of Cdc48 (11). This mutation causes a complete block of Sre2 cleavage compared with other cdc48 mutant alleles identified in a previous genetic screen, such as cdc48-2 (A586V) and cdc48-3 (E731K) in the D2 domain of Cdc48, that cause a severe impairment but not complete block (11). Consistent with this, Sre2-MS cleavage was blocked completely in cdc48-4 (Fig. 2B, lane 7) but not in cdc48-2 and cdc48-3 (data not shown). Finally, a temperature-sensitive allele ubc4-P61S of the essential E2 enzyme Ubc4 was utilized to test its role in Sre2-MS cleavage. Upon shifting to nonpermissive temperature to block Ubc4 function, the precursor form of Sre2-MS accumulated in ubc4-P61S, but not wild-type cells (Fig. 2C). This result indicated that Sre2-MS cleavage requires Ubc4. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Sre2-MS shares all functional requirements for Dsc-dependent cleavage with full-length Sre2 (aa 1–793) and Sre1 (11, 12) and thus is a model substrate for further mutational studies.

Site-directed Mutagenesis Screen of Sre2 Model Substrate

To understand comprehensively the requirements for Sre2 cleavage, we set out to screen for cleavage defects by site-directed scanning mutagenesis of Sre2-MS. Based on protein secondary structure prediction programs for structured regions and given that cleavage of both Sre1 and Sre2 occurs close to the first transmembrane segment, we focused our studies on the C-terminal 117 amino acids of Sre2-MS, mutating residues 677–793 (Fig. 3A). First, we tested a total of 94 amino acid residues by mutating amino acids either in single, double, or triple mutants (supplemental Table 1). We chose not to mutate hydrophobic residues in the transmembrane segments as these would likely not be well expressed. Mutants were grouped into three classes according to cleavage efficiency (the ratio of processed form (N) to precursor form (P)) (Table 1). 51 mutants showed normal cleavage (N>P), 28 showed a defect in cleavage (N≈P), and 15 showed a robust block in cleavage (P>N). Examples of each class are shown in Fig. 3B. For double or triple mutants that demonstrated a robust cleavage block (P>N), we further tested cleavage requirements by mutating individual amino acids to alanine for cytosolic residues and to leucine for residues within the transmembrane segments. For selective residues that are structurally similar to alanine or leucine, we mutated amino acids to charged residues such as glutamate or threonine. Fig. 3A and Table 1 summarize the results of the Sre2-MS mutagenesis screen.

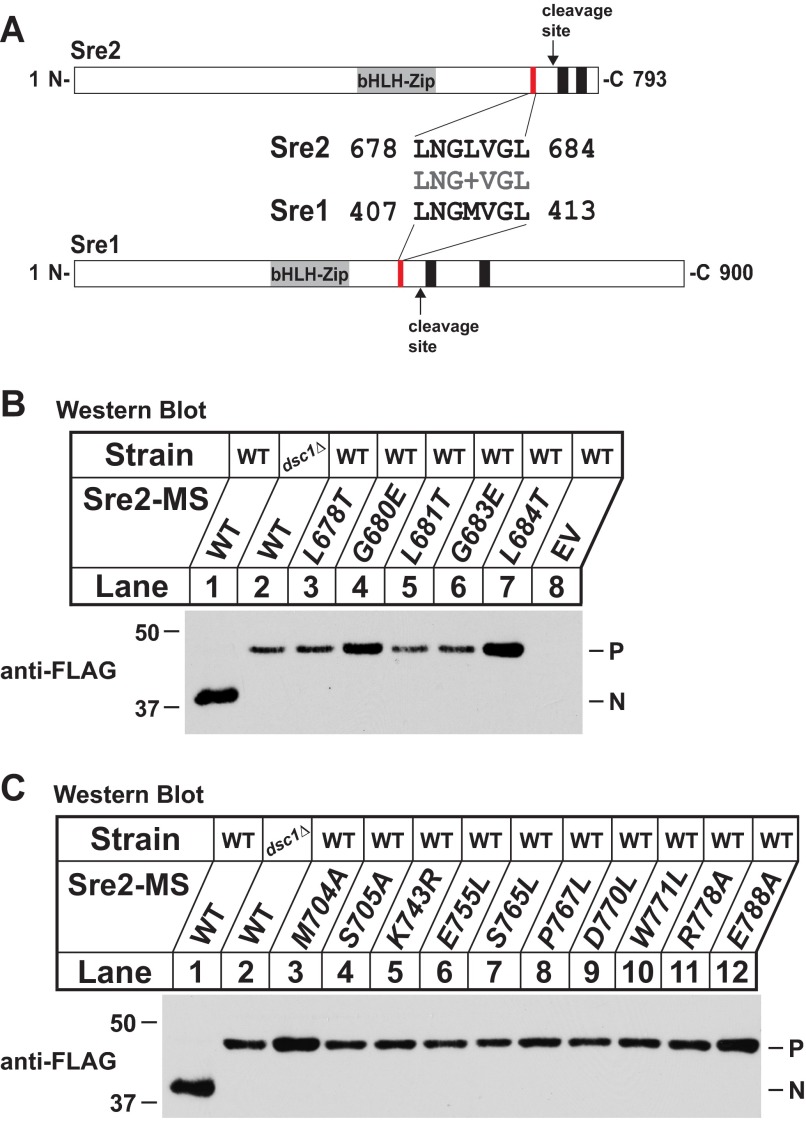

From the screen, we identified a short, 7-amino acid glycine-leucine region required for Sre2 cleavage (aa 678–684) (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, this glycine-leucine stretch is present in Sre1 (Fig. 4A) and is roughly equidistant from the first transmembrane segment in both Sre1 and Sre2 (27 and 29 amino acids, respectively). These observations suggested a role for the glycine-leucine region in Sre2 cleavage. To investigate whether this conserved sequence (aa 678–684) was required for cleavage, we assayed cleavage of single residue mutants. Notably, mutating 5 of 7 residues blocked cleavage when tested individually (Fig. 4B, lanes 3–7).

FIGURE 4.

Glycine-leucine sequence is required for yeast SREBP cleavage. A, alignment of glycine-leucine sequence from Sre1 and Sre2 of S. pombe and diagrams for Sre1 and Sre2. Numbers indicate respective amino acid positions of Sre1 and Sre2. Arrow indicates predicted cleavage site. Glycine-leucine sequence and predicted transmembrane domains are indicated by red and black boxes, respectively. B, Western blot probed with anti-FLAG IgG of lysates from indicated sre2Δ strains expressing either wild-type Sre2 model substrate (MS) or glycine-leucine sequence mutants. C, Western blot probed with anti-FLAG IgG of lysates from the indicated strains expressing either wild-type Sre2-MS or cleavage-defective mutants. P and N, precursor and cleaved nuclear forms, respectively. All strains are sre2Δ.

In addition, we identified 10 other single residues required for cleavage (Fig. 3A). Two residues, Met-704 and Ser-705, are located ∼10 amino acids before TM1 close to the cleavage site (Fig. 4C, lanes 3–12). We identified only a single residue, Lys-743, required for cleavage in the short endoplasmic reticulum luminal loop of Sre2. Mutation of five residues in the TM2 blocked cleavage (Glu-755, Ser-765, Pro-767, Asp-770, Trp-771) whereas none in TM1 was absolutely required (Fig. 3A). Finally, two charged residues in the cytosolic Sre2 C-terminal tail (Arg-778 and Glu-788) were also required for cleavage. In total, 15 C-terminal residues were found to be essential for Sre2-MS cleavage (Fig. 3A).

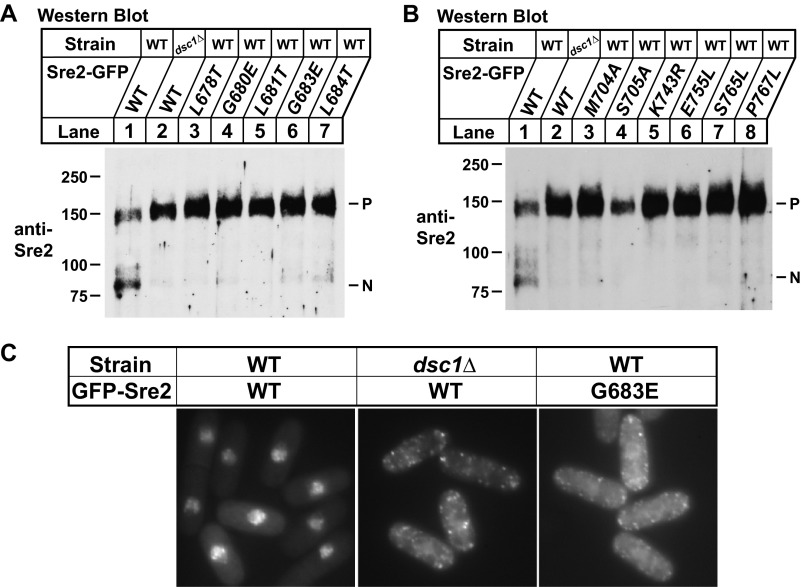

Validation of Sequence Requirements in Full-length Sre2

To independently test and verify the cleavage requirement for residues identified in the Sre2-MS screen, we generated each of the cleavage mutants in full-length GFP-Sre2. Fusion of GFP to the C terminus allows clear discrimination between the precursor (P) and cleaved nuclear (N) forms of Sre2 (12). Wild-type GFP-Sre2 was cleaved constitutively to generate Sre2N, and cleavage was blocked in dsc1Δ cells (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 and 2). Mutation of each of the five glycine-leucine region residues blocked cleavage of full-length GFP-Sre2 (Fig. 5A, lanes 3–7), emphasizing the importance of this sequence. Indeed, we observed a complete cleavage block for each of the additional 10 residues identified using Sre2-MS, examples of which are shown in Fig. 5B. These results validate Sre2 aa 423–793 as a model substrate and confirm the importance of these 15 residues for cleavage of full-length Sre2.

FIGURE 5.

Mutants are defective for cleavage of full-length Sre2. A, Western blot probed with anti-Sre2 IgG of lysates from the indicated sre2Δ strains expressing either full-length wild-type GFP-Sre2 or glycine-leucine motif mutants. B, Western blot probed with anti-Sre2 IgG of lysates from the indicated sre2Δ strains expressing either full-length wild-type GFP-Sre2 or cleavage-defective mutants. P and N, precursor and cleaved nuclear forms of GFP-Sre2, respectively. C, indicated sre2Δ strains expressing either wild-type GFP-Sre2 or GFP-Sre2 mutant grown in minimal medium lacking leucine and thiamine for 20 h to induce expression and imaged by fluorescence microscopy.

As a complementary approach to test the cleavage requirements for individual Sre2 residues, we assayed localization of different GFP-Sre2 fusion proteins in cells lacking endogenous Sre2. GFP fused to the N terminus of wild-type Sre2 translocated to the nucleus after its release from the membrane (left panel of Fig. 5C). Failure to cleave GFP-Sre2 in dsc1Δ cells caused GFP-Sre2 to localize in punctate structures (middle panel of Fig. 5C) (12). Consistent with a requirement for Dsc-dependent cleavage, GFP-Sre2 Gly-683 containing a mutation in the glycine-leucine stretch also localized to punctate structures (right panel of Fig. 5C). We tested all of the 15 individual cleavage mutants in this GFP-Sre2 assay and each failed to show nuclear localization equivalent to wild-type GFP-Sre2 (data not shown). Combined with the full-length GFP-Sre2 cleavage assays, these data demonstrate that full-length Sre2 cleavage requires each of the 15 residues isolated using Sre2-MS, showing the physiological importance of these sequences.

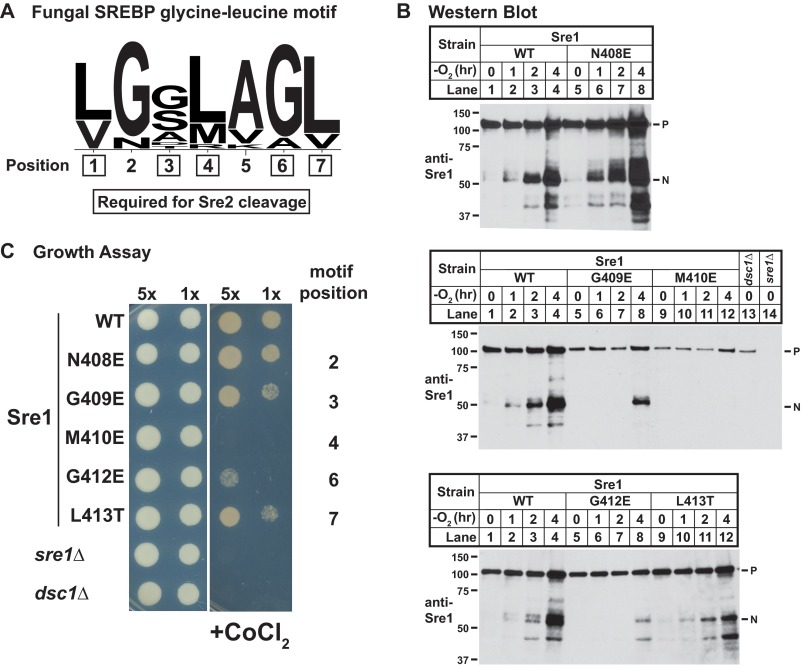

Bioinformatic Analysis Reveals Wide Conservation of Glycine-Leucine Motif in Ascomycete Fungi

Our mutagenesis screen identified a glycine-leucine sequence in Sre2 (aa 678–684) that is required for cleavage and conserved in Sre1 (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the distance of this sequence from the first transmembrane segment (∼30 amino acids) is also conserved between Sre2 and Sre1. To investigate whether the glycine-leucine region is conserved beyond S. pombe, we searched for glycine-leucine sequences in SREBPs ranging from fungi to mammals using a defined set of bioinformatic criteria. Given the short length of the conserved sequence, parameter definition was critical for the motif search and subsequent consensus motif generation. First, we isolated SREBPs from all species by sequence similarity search. We defined SREBPs by the presence of a specific tyrosine residue in the first helix of bHLH transcription factors. For each SREBP, we predicted coordinates for transmembrane segments using transmembrane prediction software, and we used only SREBPs that contained a predicted TM for subsequent analysis. Given that the glycine-leucine sequence is located at a conserved distance from TM1s of Sre1 and Sre2, we selected a 50-amino acid stretch that is centered 55 amino acids from the beginning of TM1 for each SREBP. We then performed a sequence alignment using all isolated 50-amino acid sequences. In this way, we identified a consensus sequence corresponding to the glycine-leucine motif (Fig. 6A). We identified the glycine-leucine motif in all ascomycete fungi analyzed, including pathogenic fungi A. fumigatus and Magnaporthe oryzae, but not basidiomycete fungi, like C. neoformans (supplemental Table 2). Interestingly, C. neoformans utilizes Site-2 protease to cleave and activate SREBP like mammalian cells (23). Collectively, this bioinformatic analysis identified a conserved glycine-leucine motif present in ascomycete fungi that lack Site-2 protease, further supporting a role for this sequence in SREBP cleavage.

FIGURE 6.

Glycine-leucine motif is broadly conserved in fungi and functionally conserved in Sre1. A, consensus SREBP glycine-leucine motif in fungi. Consensus sequence logo was generated by aligning 50-amino acid stretches that were isolated and centered at 55 amino acids before the first predicted TM of fungal SREBPs (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). Residues required for Sre2 cleavage are boxed. B, Western blot probed with anti-Sre1 IgG of lysates from the indicated full-length wild-type Sre1 and glycine-leucine motif mutants expressed from the chromosome. Cells were grown in rich medium for the indicated times in the absence of oxygen. Sre1 N408E is used as a control, corresponding to a residue with normal cleavage in Sre2. P and N, precursor and cleaved nuclear forms of Sre1, respectively. C, growth of wild-type, sre1Δ, dsc1Δ, and indicated sre1 mutants on YES-rich medium containing 1.6 mm cobalt chloride. 5x and 1x indicate 25,000 and 5,000 cells, respectively.

Sre1 Cleavage Requires Glycine-Leucine Motif

Having identified this conserved glycine-leucine motif, we next tested whether motif function is conserved between SREBPs. Fission yeast strains were generated that expressed wild-type or sre1 glycine-leucine motif mutants at the heterologous his3 locus (18). We cultured cells under low oxygen and assayed Sre1 cleavage by immunoblotting. Wild-type Sre1 precursor was cleaved to generate active Sre1N under hypoxia (top, middle, and bottom panels of Fig. 6B, lanes 1–4). Induction of Sre1 expressed from the his3 locus was reduced compared with wild-type cells, perhaps due to the absence of DNA elements required for key positive feedback regulation (4, 24, 25). As a control, we tested mutation of Sre1 N408E in the 7-amino acid conserved motif, corresponding to the second position in the motif that was not required for cleavage of Sre2 (aa 679) (Fig. 6A). In agreement, mutation of this residue did not affect cleavage of Sre1 (top panel of Fig. 6B, lanes 5–8). Then, we tested four of five required residues in the motif for Sre1 cleavage. Notably, mutation of glycine at the third position (Gly-409), methionine at the fourth position (Met-410), glycine at the sixth position (Gly-412), and leucine at the seventh position (Leu-413) blocked Sre1 cleavage under low oxygen (middle and bottom panels of Fig. 6B, lanes 5–12). These results were consistent with Sre2-MS, showing cleavage defects at the third, fourth, sixth, and seventh positions of the motif (Sre2 aa 678, 680, 683, and 684) (Fig. 6A). As expected, deletion of the E3 ligase dsc1 abolished Sre1 cleavage (middle panel of Fig. 6B, lane 13). In these experiments, the cleavage machinery functioned normally insomuch as endogenous Sre2 cleavage was normal (data not shown).

As an independent test, we assayed the ability of these sre1 mutants to grow in the presence of cobalt chloride, a hypoxia mimetic (6, 12). Wild-type cells, but not sre1Δ cells, grow under low oxygen (4). If Sre1 mutants are cleavage-defective, we expect to observe reduced growth on cobalt chloride, reminiscent of growth defects in sre1Δ and dsc1Δ cells. Consistent with results from the cleavage assays in Fig. 6B, Sre1 mutants blocked for cleavage failed to support wild-type growth on cobalt chloride (Fig. 6C), and growth defects correlated with the severity of observed Sre1 cleavage defects (Fig. 6B). These results demonstrate that the glycine-leucine motif is required for Sre1 cleavage, and together with the bioinformatic data suggest that this motif has a conserved function in SREBP cleavage in ascomycete fungi.

DISCUSSION

Genetic studies revealed requirements for dsc1 through dsc6 in the cleavage activation of the yeast SREBP transcription factors Sre1 and Sre2 (11, 12). Dsc1 through Dsc5 constitute the Dsc E3 ligase, a stable Golgi membrane complex containing the RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligase Dsc1 (11). dsc6 codes for Cdc48, an AAA-ATPase that binds to the Dsc E3 ligase through the ubiquitin regulatory X domain of Dsc5 (11). Previous studies indicate that the mechanism of cleavage is the same for Sre1 and Sre2 (11, 12), except that ER exit of Sre1 is regulated by sterols and oxygen and Sre2 exits the ER constitutively (4, 25). Our working model for yeast SREBP (Sre1 and Sre2) cleavage is as follows: (i) SREBP moves from the ER to Golgi; (ii) SREBP binds to the Dsc E3 ligase; (iii) SREBP is ubiquitinated by the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc4 and E3 ligase Dsc1; (iv) SREBP is subsequently cleaved by an unidentified protease releasing the N-terminal transcription factor domain from the membrane.

To develop tools that will allow us to test this model and dissect the mechanism of SREBP cleavage, we investigated the structural requirements for SREBP cleavage. We focused initially on Sre2 because its cleavage is constitutive, allowing us to study sequences required for cleavage under routine cell culture conditions rather than having to induce cleavage under hypoxia. Truncation analysis revealed that Sre2 cleavage does not require its bHLH-zip domain and demonstrated that a minimal substrate of 271 amino acids is still cleaved (Fig. 1). This result indicates that the functions of Sre2 as a transcription factor and a substrate for Dsc-dependent cleavage are separable. Using a truncated Sre2 model substrate, we identified 15 residues required for cleavage of full-length Sre2 and uncovered a novel SREBP cleavage motif. We discuss these mutants in light of our current understanding of SREBP cleavage in S. pombe and mammals.

Mutants blocked for Sre2 cleavage could be defective in any of the four steps outlined in our working model for SREBP cleavage. Sre2 cytosolic mutations could disrupt binding to COPII proteins required for sorting into vesicles and ER exit (26). However, none of the 15 Sre2 mutants localized to the ER when tested in either the GFP-Sre2 (Fig. 5C) or GFP-Sre2-MS localization studies (data not shown), suggesting that ER exit is normal in the mutants. In addition, Sre2 mutants showed wild-type expression (Fig. 4, B and C), suggesting that the proteins are properly folded and unlikely to be substrates for ER retention and ER-associated degradation (27). Determinants required for ER exit may be located between aa 523 and 676, a region required for cleavage (Fig. 1B), but not subjected to site-directed mutagenesis.

Function of Conserved Glycine-Leucine Motif in SREBP Cleavage

Several lines of evidence suggest that the glycine-leucine motif is a key determinant for Dsc-dependent SREBP cleavage. First, the glycine-leucine motif is located at a conserved distance from the first transmembrane segment of Sre1 and Sre2 in S. pombe and more than 20 other ascomycete SREBPs. Second, the presence of the glycine-leucine motif correlates with the lack of Site-2 protease homologs, i.e. every ascomycete fungus that contains the conserved glycine-leucine motif lacks a Site-2 protease homolog (10). Third, the glycine-leucine motif is functionally required for both Sre1 and Sre2 cleavage in S. pombe. Fourth, this motif is broadly conserved among ascomycete fungi.

Protein secondary structure software predicts this novel glycine-leucine motif folds either as α-helix or β-strand. This motif might represent a hydrophobic interface for interaction with the Dsc E3 ligase or the unidentified fungal SREBP protease. Given that the motif is located at a distance (∼20 amino acids) from the cleavage site, it is unlikely to participate in interactions with the protease active site. Indeed, a definitive functional assignment for this motif requires the development of additional assays for Dsc E3 ligase recognition, SREBP ubiquitination, and SREBP proteolytic cleavage.

As noted, the protease that cleaves SREBP in this system is not known. Mammalian SREBP is cleaved sequentially by the Site-1 protease after RXXL in the ER luminal loop before it can be cleaved by the Site-2 protease within TM1 to release functional transcription factor domain (28). Site-1 protease belongs to the subtilisin/kexin-like protease family, required for cleaving many proproteins to their active form (29, 30). Interestingly, we have isolated a cleavage mutant in the ER luminal loop of Sre2 at lysine 743. A charge-conservative mutation from lysine to arginine blocks Sre2 cleavage (Fig. 3). Subtilisin/kexin-like proteases typically cleave after lysine or arginine and dibasic sequences (29, 30), as evidenced by normal SREBP cleavage in mammals for the same corresponding Lys to Arg mutation (22). Further, in contrast to the cleavage of mammalian SREBP by Site-1 protease at a luminal RXXL sequence, this sequence is not conserved in Sre2 (22). More generally, proteases in the subtilisin/kexin-like family cleave after the consensus RX(R/K)R sequence, where X is any amino acid except cysteine (31). Collectively, these data argue against a Site-1 protease-like cleavage for yeast SREBP.

A Site-2 protease cleavage mechanism is also unlikely given the cytosolic cleavage sites of Sre1 (12) and Sre2 (Fig. 2A). Sre2 cleavage defects at methionine 704 and serine 705 represent cleavage mutants close to the cleavage site (Fig. 3A). These mutants might interfere directly with interaction between Sre2 and the unidentified protease. Consistent with this, the presence of Site-2 protease correlates with cleavage within the membrane (10, 23), whereas the absence of Site-2 protease correlates with cytosolic cleavage. Given the lack of Site-2 protease homologs in S. pombe and the broader ascomycete fungal phylum, and no detectable cleavage within TM1, a new cleavage mechanism might be employed for ascomycete SREBPs.

Sre2 cleavage mutants are enriched in TM2 (Fig. 3A), but a close examination of other SREBP TM2s did not reveal conserved sequences. Interestingly, ubiquitination and sorting of the Pep12 membrane protein into the multivesicular body required insertion of an aspartate residue into its transmembrane segment and Tul1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of the Dsc1 E3 ligase (32). Thus, it is possible that charged residues in a transmembrane segment are a signal for substrate recognition. Sre2 cleavage mutants within TM2 that contain a polar residue, such as glutamate 755, might fail to be recognized by the Dsc1 E3 ligase through the same mechanism.

Identification of the fungal SREBP protease and further characterization of Dsc E3 ligase function will require development of new assays. Importantly, these mutants will aid the identification of the protease and future structure-function studies. For example, genetic suppression of Sre1 cleavage-defective mutants may uncover components required for different steps in the pathway.

Implications for Fungal Pathogenesis

Ascomycete fungal pathogens remain detrimental to human health and agriculture. For instance, A. fumigatus is a major cause of life-threatening infections in immunocompromised individuals (33). Notably, A. fumigatus SREBP homolog SrbA as well as Dsc E3 ligase homologs are required for pathogenesis (7, 13). Interestingly, the glycine-leucine motif is conserved in Aspergillus. In terms of agriculture, the fungal rice blast pathogen M. oryzae, which causes destructive rice diseases and crop losses worldwide (34), also contains a putative SREBP homolog and the cleavage motif. Thus, this motif may be required for SREBP cleavage activation across ascomycete fungal pathogens. Because many other pathogenic fungi contain an SREBP pathway and the conserved motif, this study provides insight into molecular underpinnings of SREBP cleavage activation that may have broad antifungal applications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sumana Raychaudhuri for strains and for reviewing the manuscript, members of the Espenshade laboratories for excellent advice and discussion, and Shan Zhao for outstanding technical support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL077588 (to P. J. E.). This work was also supported by an Isaac Morris Hay and Lucille Elizabeth Hay graduate fellowship award (to R. C.) from the Department of Cell Biology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

This article contains supplemental Tables 1–3.

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- aa

- amino acids

- AAA

- ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities

- bHLH-zip

- basic-helix-loop-helix zipper

- CaMV

- cauliflower mosaic virus

- Dsc

- defective for SREBP cleavage

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- MS

- model substrate

- TM1

- first transmembrane segment

- TM2

- second transmembrane segment.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shao W., Espenshade P. J. (2012) Expanding roles for SREBP in metabolism. Cell Metab. 16, 414–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Espenshade P. J., Hughes A. L. (2007) Regulation of sterol synthesis in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 401–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rawson R. B., Zelenski N. G., Nijhawan D., Ye J., Sakai J., Hasan M. T., Chang T. Y., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1997) Complementation cloning of S2P, a gene encoding a putative metalloprotease required for intramembrane cleavage of SREBPs. Mol. Cell 1, 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hughes A. L., Todd B. L., Espenshade P. J. (2005) SREBP pathway responds to sterols and functions as an oxygen sensor in fission yeast. Cell 120, 831–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang Y. C., Bien C. M., Lee H., Espenshade P. J., Kwon-Chung K. J. (2007) Sre1p, a regulator of oxygen sensing and sterol homeostasis, is required for virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 614–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee H., Bien C. M., Hughes A. L., Espenshade P. J., Kwon-Chung K. J., Chang Y. C. (2007) Cobalt chloride, a hypoxia-mimicking agent, targets sterol synthesis in the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 1018–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Willger S. D., Puttikamonkul S., Kim K. H., Burritt J. B., Grahl N., Metzler L. J., Barbuch R., Bard M., Lawrence C. B., Cramer R. A., Jr. (2008) A sterol-regulatory element binding protein is required for cell polarity, hypoxia adaptation, azole drug resistance, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathogens 4, e1000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Osborne T. F., Espenshade P. J. (2009) Evolutionary conservation and adaptation in the mechanism that regulates SREBP action: what a long, strange tRIP it's been. Genes Dev. 23, 2578–2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chun C. D., Liu O. W., Madhani H. D. (2007) A link between virulence and homeostatic responses to hypoxia during infection by the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathogens 3, e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bien C. M., Espenshade P. J. (2010) Sterol regulatory element binding proteins in fungi: hypoxic transcription factors linked to pathogenesis. Eukaryotic Cell 9, 352–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stewart E. V., Lloyd S. J., Burg J. S., Nwosu C. C., Lintner R. E., Daza R., Russ C., Ponchner K., Nusbaum C., Espenshade P. J. (2012) Yeast sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) cleavage requires Cdc48 and Dsc5, a ubiquitin regulatory X domain-containing subunit of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 672–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stewart E. V., Nwosu C. C., Tong Z., Roguev A., Cummins T. D., Kim D. U., Hayles J., Park H. O., Hoe K. L., Powell D. W., Krogan N. J., Espenshade P. J. (2011) Yeast SREBP cleavage activation requires the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase complex. Mol. Cell 42, 160–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Willger S. D., Cornish E. J., Chung D., Fleming B. A., Lehmann M. M., Puttikamonkul S., Cramer R. A. (2012) Dsc orthologs are required for hypoxia adaptation, triazole drug responses, and fungal virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryotic Cell 11, 1557–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chang Y. C., Ingavale S. S., Bien C., Espenshade P., Kwon-Chung K. J. (2009) Conservation of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein pathway and its pathobiological importance in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryotic Cell 8, 1770–1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blatzer M., Barker B. M., Willger S. D., Beckmann N., Blosser S. J., Cornish E. J., Mazurie A., Grahl N., Haas H., Cramer R. A. (2011) SREBP coordinates iron and ergosterol homeostasis to mediate triazole drug and hypoxia responses in the human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bähler J., Wu J. Q., Longtine M. S., Shah N. G., McKenzie A., 3rd, Steever A. B., Wach A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. (1998) Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14, 943–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forsburg S. L. (1993) Comparison of Schizosaccharomyces pombe expression systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2955–2956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burke J. D., Gould K. L. (1994) Molecular cloning and characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe his3 gene for use as a selectable marker. Mol. Gen. Genet. 242, 169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stajich J. E., Block D., Boulez K., Brenner S. E., Chervitz S. A., Dagdigian C., Fuellen G., Gilbert J. G., Korf I., Lapp H., Lehväslaiho H., Matsalla C., Mungall C. J., Osborne B. I., Pocock M. R., Schattner P., Senger M., Stein L. D., Stupka E., Wilkinson M. D., Birney E. (2002) The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res. 12, 1611–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee S. J., Sekimoto T., Yamashita E., Nagoshi E., Nakagawa A., Imamoto N., Yoshimura M., Sakai H., Chong K. T., Tsukihara T., Yoneda Y. (2003) The structure of importin-β bound to SREBP-2: nuclear import of a transcription factor. Science 302, 1571–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duncan E. A., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L., Sakai J. (1997) Cleavage site for sterol-regulated protease localized to a Leu-Ser bond in the lumenal loop of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 12778–12785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bien C. M., Chang Y. C., Nes W. D., Kwon-Chung K. J., Espenshade P. J. (2009) Cryptococcus neoformans Site-2 protease is required for virulence and survival in the presence of azole drugs. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 672–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee C. Y., Yeh T. L., Hughes B. T., Espenshade P. J. (2011) Regulation of the Sre1 hypoxic transcription factor by oxygen-dependent control of DNA binding. Mol. Cell 44, 225–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Porter J. R., Lee C. Y., Espenshade P. J., Iglesias P. A. (2012) Regulation of SREBP during hypoxia requires Ofd1-mediated control of both DNA binding and degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 3764–3774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barlowe C., Orci L., Yeung T., Hosobuchi M., Hamamoto S., Salama N., Rexach M. F., Ravazzola M., Amherdt M., Schekman R. (1994) COPII: a membrane coat formed by Sec proteins that drive vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 77, 895–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hughes B. T., Nwosu C. C., Espenshade P. J. (2009) Degradation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein precursor requires the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation components Ubc7 and Hrd1 in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20512–20521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1999) A proteolytic pathway that controls the cholesterol content of membranes, cells, and blood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11041–11048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Seidah N. G. (2011) The proprotein convertases, 20 years later. Methods Mol. Biol. 768, 23–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seidah N. G., Day R., Marcinkiewicz M., Chrétien M. (1998) Precursor convertases: an evolutionary ancient, cell-specific, combinatorial mechanism yielding diverse bioactive peptides and proteins. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 839, 9–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steiner D. F. (1998) The proprotein convertases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2, 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reggiori F., Pelham H. R. (2002) A transmembrane ubiquitin ligase required to sort membrane proteins into multivesicular bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Latgé J. P. (1999) Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 310–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilson R. A., Talbot N. J. (2009) Under pressure: investigating the biology of plant infection by Magnaporthe oryzae. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]