Background: Macrophages play an important role in inflammation and injury as well as resolution of the response.

Results: Mitochondrial Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 polarizes macrophages to an M2 phenotype.

Conclusion: A prolonged predominance of M2 macrophages can induce a fibrotic phenotype.

Significance: The antioxidant enzyme, Cu,Zn-SOD, increases mitochondrial H2O2 levels, which is linked to pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: Hydrogen Peroxide, Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress, Pulmonary Fibrosis, Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Macrophage Phenotype, STAT6

Abstract

Macrophages not only initiate and accentuate inflammation after tissue injury, but they are also involved in resolution and repair. This difference in macrophage activity is the result of a differentiation process to either M1 or M2 phenotypes. M1 macrophages are pro-inflammatory and have microbicidal and tumoricidal activity, whereas the M2 macrophages are involved in tumor progression and tissue remodeling and can be profibrotic in certain conditions. Because mitochondrial Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase (Cu,Zn-SOD)-mediated H2O2 is crucial for development of pulmonary fibrosis, we hypothesized that Cu,Zn-SOD modulated the macrophage phenotype. In this study, we demonstrate that Cu,Zn-SOD polarized macrophages to an M2 phenotype, and Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 levels modulated M2 gene expression at the transcriptional level by redox regulation of a critical cysteine in STAT6. Furthermore, overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD in mice resulted in a profibrotic environment and accelerated the development of pulmonary fibrosis, whereas polarization of macrophages to the M1 phenotype attenuated pulmonary fibrosis. Taken together, these observations provide a novel mechanism of Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated and Th2-independent M2 polarization and provide a potential therapeutic target for attenuating the accelerated development of pulmonary fibrosis.

Introduction

Pulmonary fibrosis is characterized by aberrant wound healing that leads to progressive deposition of collagen in extracellular spaces. Macrophages play an integral role in the pathogenesis of fibrosis by initiating an immune response and by generating reactive oxygen species (1). Macrophage plasticity is an important feature of these innate immune cells. Macrophage phenotypes are divided into two categories, the classically activated macrophages (CAM, M1 phenotype) and the alternatively activated macrophages (AAM, M2 phenotype), depending on stimulation by Th1 or Th2 cytokines, respectively (2).

M1 macrophages are commonly associated with the generation of proinflammatory cytokines, whereas M2 macrophages are anti-inflammatory and often associated with fibrotic conditions, including pulmonary fibrosis (3). M2 macrophages harbor a repertoire of pro-fibrotic signature changes, such as 1) increased expression of anti-inflammatory and profibrotic immune effectors, including TGF-β and C-C motif ligand 18, 2) up-regulated l-arginine metabolism by arginase I instead of iNOS2 to generate polyamines and proline, an important precursor for collagen synthesis, and 3) increased resistin-like secreted protein, found in inflammatory zone (FIZZ1) and chitinase-like secretory lectin, Ym1, which are actively involved in extracellular matrix dynamics.

Macrophages produce high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including H2O2, which has a critical role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Superoxide anion (O2˙̄) reacts with superoxide dismutase (SOD) at a rate constant of 109 m−1 s−1, which is associated with H2O2 generation. There are three SOD enzymes: Cu,Zn-SOD (SOD1) is located in the cytosol and mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS); Mn-SOD (SOD2) is located in the mitochondrial matrix; and EC-SOD (SOD3), which is an extracellular SOD (4, 5). The rate of H2O2 generation has been shown to increase with elevated levels of Mn-SOD in mitochondria (6). Because we have shown that the lungs of Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice have reduced oxidative stress and do not develop pulmonary fibrosis (7), these data suggest that Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 generation in alveolar macrophages is a critical factor in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Thus, understanding the effect of Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 generation in regulating alveolar macrophage polarization may uncover a mechanism by which H2O2 levels mediate pulmonary fibrosis.

The regulation of Th2 cytokine-induced M2 gene expression occurs, in part, at the transcriptional level by the activation of STAT6 (8). DNA binding and transcriptional activity of STAT6 requires the Src homology domain 2 (SH2) after IL-4 stimulation (9). The relationship between Cu,Zn-SOD and STAT6, however, is not known. In the current study we demonstrate that Cu,Zn-SOD accelerates the development of pulmonary fibrosis by inducing early and sustained alternative activation of macrophages. Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 required Cys528 in the SH2 domain of STAT6 to mediate M2 gene expression. These observations provide a novel mechanism of a Th2-independent, redox-dependent M2 polarization by regulation of STAT6 and provide a potential therapeutic target for attenuating the progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Chrysotile asbestos was provided Dr. Peter S. Thorne, University of Iowa College of Public Health. p-Hydroxylphenyl acetic acid (pHPA), polyethylene glycol-conjugated catalase (PEG-CAT), PEG-SOD, rotenone, antimycin A, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were purchased from Sigma.

Human Subjects

The Human Subjects Review Board of the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine approved the protocol of obtaining alveolar macrophages from normal volunteers and patients with asbestosis. Normal volunteers had to meet the following criteria: 1) ages between 18 and 55 years, 2) no history of cardiopulmonary disease or other chronic disease, 3) no prescription or nonprescription medication except oral contraceptives, 4) no recent or current evidence of infection, and 5) a lifetime nonsmoker. Alveolar macrophages were also obtained from patients with asbestosis. Patients with asbestosis had to meet the following criteria: 1) forced expiratory volume in 1 s and diffusion capacity of lung for carbon monoxide at least 50% predicted, 2) current nonsmoker, 3) no recent or current evidence of infection, and 4) evidence of restrictive physiology on pulmonary function tests and interstitial fibrosis on chest computed tomography. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage was performed after subjects received intramuscular atropine (0.6 mg) and local anesthesia. Three subsegments of the lung were lavaged with five 20-ml aliquots of normal saline, and the first aliquot in each was discarded. The percentage of alveolar macrophages was determined by Wright-Giemsa stain and varied from 90 to 98%.

Mice

Wild-type (WT), Cu,Zn-SOD−/−, and Cu,Zn-SODTg (a generous gift from Dr. Donald Heistad, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) C57BL/6 mice were used in these studies, and all protocols were approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were intratracheally administered 100 μg of chrysotile asbestos suspended in 50 μl of 0.9% saline solution after being anesthetized with 3% isoflurane using a precision Fortec vaporizer (Cyprane, Keighley, UK). Mice were euthanized at the designated day after exposure with an overdose of isoflurane, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. BAL cells were used for differential cell number. Alveolar macrophages were isolated from BAL fluid and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Bone marrow cells were isolated and incubated in L929 cell-conditioned media for 7 days to generate monocytes/macrophages.

Cell Culture

Human monocyte (THP-1) and mouse alveolar macrophage (MH-S) cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 media with the following supplements: 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. All experiments were performed with 0.5% serum supplement.

Plasmids and Transfections

A 696-bp fragment (−643/+53) of human TNF-α promoter was cloned into the KpnI/NheI sites of PGL3-basic using TNF-α-promoter-CAT as a template for PCR amplification followed by Kpn/NheI digestion with subsequent ligation of products using T4 DNA ligase (10). Human STAT6 cDNA (NM_003153, GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD) was cloned into pcDNA3.1D/V5-His-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Mutant pCDNA3.1-STAT6C528S-V5-His was generated using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). DNA sequences of all plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (University of Iowa DNA facility). Plasmid vectors were transfected into cells using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Determination of H2O2 Generation

Extracellular H2O2 production was determined fluorometrically, as previously described (11). Briefly, cells were incubated in phenol-red free Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 6.5 mm glucose, 1 mm HEPES, 6 mm sodium bicarbonate, 1.6 mm pHPA, and 0.95 μg/ml HRP. Cells were exposed to chrysotile asbestos (10 μg/cm2), and fluorescence of pHPA-dimer was measured using a spectrofluorometer at excitation of 320 nm and emission of 400 nm.

Adenoviral Vectors

Cells were infected with replication-deficient adenovirus type 5 with the E1 region replaced with DNA containing the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter region alone (Ad5.CMV) or Ad5.Cu,Zn-SOD vector (Gene Transfer Vector Core, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA) at a multiplicity of infection of 500 in serum-free RPMI medium. Serum supplement was added to the medium after 5 h to a final concentration of 0.5%.

Luciferase Assay

To correct for transfection efficiency, cells were co-transfected with phL-TK vector encoding Renilla luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined in cell lysates using the Dual Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Isolation of Membrane, Mitochondria, Endoplasmic Reticulum, Nucleus, and Cytoplasm

Membrane, mitochondrial, endoplasmic reticulum, nuclear, and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted as previously described (7, 12–14). For membrane isolation, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitors. Lysates were homogenized using a Kontes Pellet Pestle Motor and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were then centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h. After removal of the supernatant, the membrane pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer. Mitochondria were isolated by lysing the cells in a mitochondria buffer containing 10 mm Tris, pH 7.8, 0.2 mm EDTA, 320 mm sucrose, and protease inhibitors. Lysates were homogenized using a Kontes Pellet Pestle Motor and centrifuged at 2000 × g for 8 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and kept at 4 °C, and the pellet was lysed, homogenized, and centrifuged again. The two supernatants were pooled and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet was washed in the mitochondrial buffer twice and then resuspended in mitochondria buffer without sucrose. The endoplasmic reticulum was isolated by homogenizing cells in a lysis buffer containing 0.3 m sucrose, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 2 mm dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors. The homogenate was first centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 30,000 g for 20 min to obtain the crude endoplasmic reticulum fraction. Nuclear isolation was performed by resuspending cells in a lysis buffer (10 mm HEPES, 10 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EDTA) for 15 min on ice. Nonidet P-40 (10%) was added to lyse the cells, and the cells were centrifuged at 4 °C at 14,000 rpm. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in an extraction buffer (50 mm HEPES, 50 mm KCl, 300 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol) for 20 min on ice. After centrifuging at 4 °C at 14,000 rpm, the supernatant was collected as nuclear extract. The cytoplasm was isolated by resuspending cells in a lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8, 10 mm EDTA, protease inhibitors) and sonicating for 10 s on ice. The lysate was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 10 min, after which the supernatant containing the cytoplasmic fraction was collected.

Hydroxyproline Determination

Lung tissue was digested for 24 h at 112 °C with 6 n hydrochloric acid. Hydroxyproline concentration was determined as previously described (15).

Immunoblot Analysis

Whole cells lysates were obtained as described (16) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblot analyses were performed with the designated antibodies followed by the appropriate secondary antibodies cross-linked to HRP. Rabbit anti-STAT6, rabbit anti-lamin A/C, rabbit anti-Bip, rabbit anti-VDAC (Cell Signaling), mouse anti-β-actin (Sigma), mouse anti-GAPDH (Chemicon), mouse anti-6-His (Covance, CA), mouse anti-gp91phox (BD Biosciences), and sheep anti-Cu,Zn-SOD (Calbiochem) were used for immunoblot analysis. Densitometry was determined utilizing ImageJ.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA were obtained using TRIzol reagent (Sigma). After reverse transcription using iScript reverse transcription kit (Bio-Rad), M1 and M2 marker gene mRNA expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR using the SYBR Green kit. The following primer sets were used: mouse TNF-α, 5′-CAC TTG GTG GTT TGC TAC GA-3′ and 5′-CCA CAT CTC CCT CCA GAA AA-3′; mouse Ym1, 5′-TGT TCT GGT GAA GGA AAT GCG-3′ and 5′-CGT CAA TGA TTC CTG CTC CTG-3′; mouse arginase I, 5′-CAG AAG AAT GGA AGA GTC AG-3′ and 5′-CAG ATA TGC AGG GAG TCA CC-3′; mouse FIZZ1, 5′-CCT GCT GGG ATG ACT GCT ACT-3′ and 5′-AGA TCC ACA GGC AAA GCC AC-3′; mouse iNOS, 5′-GCT CCT CGC TCA AGT TCA GC-3′ and 5′-GTT TCT GGC AGC AGC GGC TC-3′; mouse β-actin, 5′-AGA GGG AAA TCG TGC GTG AC-3′ and 5′-CAA TAG TGA TGA TGA CCT GGC CGT-3′; mouse IL-1β, 5′-GAT CCA CAC TCT CCA GCT GCA-3′ and 5′-CAA CCA ACA AGT GAT ATT CTC CAT G-3′; mouse collagen Ia1, 5′-GAG TTT CCG TGC CTG GCC CC-3′ and 5′-ACC TCG GGG ACC CAT CTG GC-3′; human mannose receptor, 5′-GCA ATC CCG GTT CTC ATG GC-3′ and 5′-CGA GGA AGA GGT TCG GTT CAC C-3′; human CCL18, 5′-GCT TCA GGT CGC TGA TGT ATT-3′ and 5′-CCC TCC TTG TCC TCG TCT G-3′; human hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase, 5′-CCT CAT GGA CTG ATT ATG GAC-3′ and 5′-CAG ATT CAA CTT GCG CTC ATC-3′. Data were calculated by the ΔΔCT method. The mRNA measurements were normalized to β-actin or hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase and expressed in arbitrary units.

Immunohistochemistry

Lung sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Sections were H2O2-quenched, blocked, and incubated overnight with goat anti-arginase I (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 °C. Tissues were sequentially incubated with the donkey anti-goat IgG-biotinylated secondary antibody, streptavidin-HRP, and 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride at room temperature.

SOD Activity Assay

SOD activity assays were performed as described previously (17). Briefly, SOD activity was measured by separating samples on a 12% native polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained by incubation with 2.43 mm nitroblue tetrazolium, 28 μm riboflavin, and 28 mm TEMED in the dark.

Lucigenin Assay

Lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence assay was performed with membrane or mitochondrial protein as previously described (18). Briefly, protein lysates (10 μg) were mixed with lucigenin (5 mm), NADPH (100 mm), and PBS to a total volume of 1 ml, and luminescence was recorded every 30 s for 10 min as real light units by using a Sirius Luminometer (Berthold, Pforzheim, Germany).

ELISA

Active TGF-β, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-13, and MIP-2 in BAL fluid and cell media was measured by ELISA (R&D, Minneapolis, MN) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Arginase Activity Assay

Arginase activity was measured by using a QuantiChrom Arginase Assay kit (BioAssay System, Hayward, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

NO Measurement

Cellular generation of NO• was determined from the accumulation of nitrite in culture media. Nitrite is the main oxidation product found in vitro due to the extracellular oxidation of NO• by O2. The accumulated nitrite in the cell culture media was determined with a Sievers 280i nitric oxide analyzer (GE Analytical Instruments, Boulder, CO) using 1% potassium iodide in glacial acetic acid to reduce NO2− to NO•. Concentration of NO• was determined by chemiluminescence.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using an unpaired, one-tailed t test or one-way analysis of variance with Newman-Keuls post analysis. Values in the figures are expressed as the means and S.D., and p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Alveolar Macrophages from Asbestosis Patients Have an M2 Phenotype

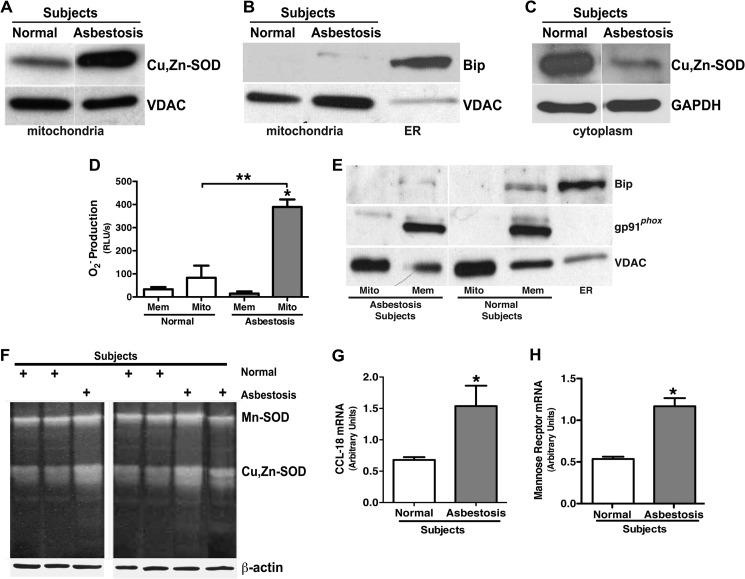

Because alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients produce high levels of H2O2 and H2O2 production in macrophages is associated with mitochondrial localization of Cu,Zn-SOD in asbestos-exposed macrophages (7), we investigated if Cu,Zn-SOD was localized in the mitochondria in alveolar macrophages from patients. Isolated mitochondria from alveolar macrophages obtained from patients with asbestosis demonstrated significantly greater immunoreactive Cu,Zn-SOD compared with normal subjects (Fig. 1A). Fractionation controls of the mitochondria are shown by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1B). In contrast, Cu,Zn-SOD in the cytoplasm was much greater in the alveolar macrophages obtained from normal subjects (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients have an M2 phenotype. Mitochondria and cytoplasm were isolated from alveolar macrophages obtained from normal subjects (n = 3) and asbestosis patients (n = 3). A, a representative immunoblot analysis for Cu,Zn-SOD in mitochondria is shown. B, shown is a representative immunoblot analysis for Bip and VDAC in the mitochondrial fractionations. ER, endoplasmic reticulum. C, shown is a representative immunoblot analysis for Cu,Zn-SOD in cytoplasm in alveolar macrophages. D, membrane and mitochondria were isolated from alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients and normal subjects. Membrane (Mem) and mitochondrial (Mito) protein lysates were used for measuring superoxide anion generation utilizing lucigenin assay. The superoxide generation rate (real light units s−1) was measured in both mitochondrial and membrane fractions. n = 3. *, p < 0.05 versus asbestosis membrane. **, p < 0.05 versus asbestosis mitochondria. E, mitochondria, membrane, and endoplasmic reticulum from asbestosis patients and normal volunteers were isolated, and immunoblot analysis for VDAC, gp91phox, and Bip was performed. F, Mn-SOD activity and Cu,Zn-SOD activity of alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients (n = 3) and normal subjects (n = 4) were measured by native gel with nitroblue tetrazolium staining. Total RNA of alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients and normal volunteers were isolated, and C-C motif ligand 18 (CCL-18; G) and mannose receptor gene expression (H) were measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase mRNA. *, p < 0.05 versus normal subjects (n = 3).

Because we have shown that alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients generate significantly more H2O2 compared with normal subjects (7), we investigated the source of O2˙̄ in alveolar macrophages obtained from patients and normal subjects. In asbestosis patients, mitochondria generated significantly more O2˙̄ than the membrane fraction as well as greater than both the membrane and mitochondrial fractions in normal subjects (Fig. 1D). The generation of O2˙̄ from the mitochondria increased in a time-dependent manner in asbestosis patients (data not shown). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the O2˙̄ production rate in the mitochondrial and the membrane fractions isolated from normal subjects. The purity of mitochondria and membrane was examined by immunoblot analysis for specific mitochondrial, membrane, and endoplasmic reticulum markers, VDAC, gp91phox, and Bip, respectively (Fig. 1E). Combined with our prior data showing that overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD decreased mitochondrial O2˙̄ levels (7), these results suggest that the majority of Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 generation in macrophages is from the mitochondria.

To determine whether the Cu,Zn-SOD activity was increased in alveolar macrophages obtained from asbestosis patients, SOD activity assays were performed. Mn-SOD activity was similar in normal subjects and asbestosis patients, but Cu,Zn-SOD activity was significantly greater in macrophages from asbestosis patients compared with normal subjects (Fig. 1F).

Because M2 macrophages are associated with fibrogenesis, we investigated whether alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients have a predominant M2 phenotype. Alveolar macrophages were obtained from normal subjects and patients with asbestosis, and mRNA was isolated. The M2 genes C-C motif ligand 18 (CCL-18; Fig. 1G) and surface mannose receptor (Fig. 1H) were significantly increased in macrophages from asbestosis patients compared with normal volunteers, suggesting M2 polarization in alveolar macrophages obtained from the patients. Based on these novel observations, we formulated the hypothesis that Cu,Zn-SOD induces pulmonary fibrosis in part by promoting the early and sustained alternative activation of macrophages, which accelerates pro-fibrotic cytokine generation and collagen synthesis by modulation of H2O2 generation.

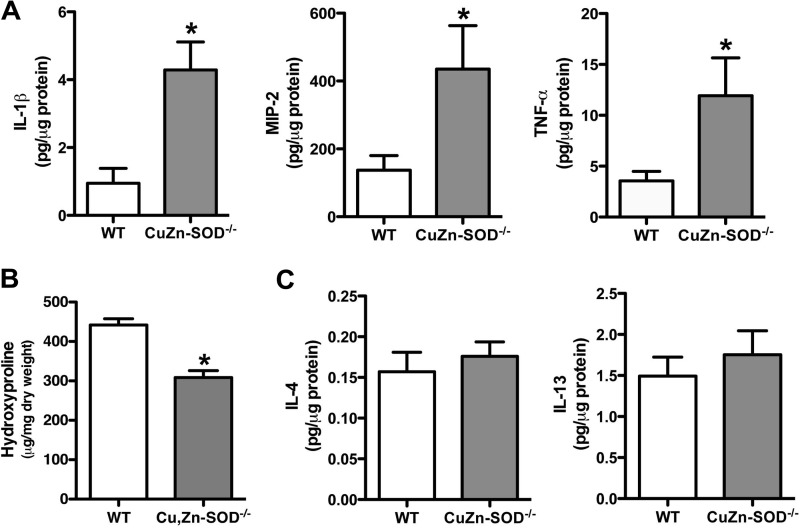

Alveolar Macrophages from Cu,Zn-SOD−/− Mice Have an M1 Phenotype

To investigate the role of Cu,Zn-SOD in modulating macrophage phenotype, we questioned whether Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice, which do not develop pulmonary fibrosis, had a predominant M1 macrophage phenotype compared with WT mice. WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice were euthanized 21 days after asbestos exposure, and bronchoalveolar lavage was performed. The principal (>90%) cell type in the BAL fluid was alveolar macrophages in both strains of mice (data not shown). Proinflammatory cytokine levels in BAL fluid were measured. Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice had significantly higher levels of M1 markers, such as IL-1β, MIP-2, and TNF-α, in BAL fluid compared with WT mice (Fig. 2A). To determine the effect of the predominant M1 phenotype in Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice, lungs were excised from mice exposed to asbestos, and a hydroxyproline assay was performed to measure collagen content. WT mice had significantly higher hydroxyproline levels in their lungs compared with Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that alveolar macrophages from Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice are primarily M1 macrophages, which may contribute to their protection from developing pulmonary fibrosis.

FIGURE 2.

Cu,Zn-SOD−/− macrophages have increased M1 markers. A, WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice were exposed to 100 μg of chrysotile asbestos intratracheally. IL-1β, MIP-2, and TNF-α cytokine levels were measured in BAL fluid of WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice 21 days after asbestos exposure. *, p < 0.05 versus WT. (n = 6 per each group). B, extracellular collagen deposition in lung of WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice after initial asbestos exposure was determined using hydroxyproline assay. *, p < 0.05 versus WT. (n = 4 per each group). C, IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine levels were measured in BAL fluid of WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− 21 days after initial asbestos exposure (n = 11 per each group).

WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− Mice Have Similar Th2 Cytokine Levels

Because alveolar macrophages from Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice are primarily an M1 phenotype compared with WT mice, we investigated whether these changes were related to differences in Th2 cytokine levels in the lung. The concentrations of two prominent Th2 cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13, in BAL fluid were similar in WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that alveolar macrophages from Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice have a proinflammatory, or M1, phenotype and suggest that this phenotype is not due to an alteration in the level of Th2 cytokines. Furthermore, these data suggest that the absence of Cu,Zn-SOD has no effect on the expression of Th2 cytokines.

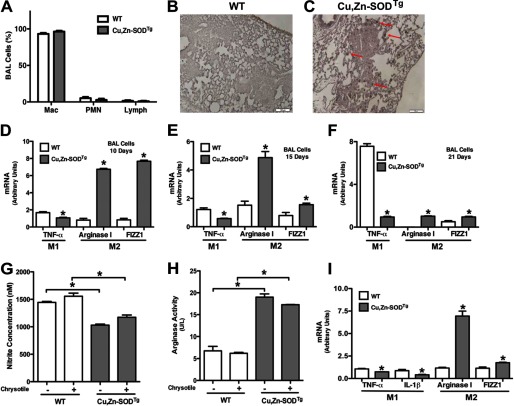

Cu,Zn-SOD Induces Macrophage M2 Polarization

Because macrophage polarization was different in WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice but both had similar levels of Th2 cytokines, we postulated that Cu,Zn-SOD mediates M2 polarization. WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice, which have more than a 3-fold increase of Cu,Zn-SOD protein expression and activity (19), were used to investigate the hypothesis that Cu,Zn-SOD mediates M2 polarization. To determine if alveolar macrophages were the predominant cell type in BAL fluid, WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice were exposed to chrysotile asbestos. Cell differential was determined, and >90% of the BAL cells were macrophages (Fig. 3A). We next determined the phenotype of the alveolar macrophages. The lungs were excised, and immunohistochemistry for the M2 marker, arginase I, was performed. The majority of macrophages in the lungs from Cu,Zn-SODTg mice stained for arginase I compared with the limited number in WT mice (Fig. 3, B and C).

FIGURE 3.

Cu,Zn-SOD induces macrophage M2 polarization. WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice were exposed to 100 μg of chrysotile asbestos intratracheally. A, BAL was performed 21 days after exposure, and cell differential was determined with Wright-Giemsa stain (n = 3). Mac, macrophage; PMN, polymorphonuclear cell. Lung sections of both WT (B) and Cu,Zn-SODTg (C) were processed for arginase I immunohistochemistry staining. Representative micrographs of one of three animals per genotype are shown. Magnification is 10×, and the bar indicates 100 μm. Macrophages isolated from WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice were cultured in the presence or absence of chrysotile asbestos overnight. 10 (D), 15 (E), or 21 (F) days after asbestos exposure the animals were euthanized, and alveolar macrophages were isolated by BAL and exposed in vitro to chrysotile for 4 h. Total RNA was isolated, and TNF-α, arginase I, and FIZZ1 gene expression were measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. *, p < 0.05 versus WT (n = 4 per each group). G, nitrite concentration was measured in cell culture medium. H, cell lysates were used to determine arginase activity by measuring urea synthesis and is expressed as units/liter of sample. U represents 1 unit of arginase that converts 1 μmol of l-arginine to urea per minute. *, p < 0.05 versus Cu,Zn-SODTg. (n = 4 per each group). I, macrophages isolated from WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg were cultured in BAL fluid from WT mice after asbestos exposure in the presence of chrysotile asbestos overnight. Total RNA was isolated, and TNF-α, IL-1β, arginase I, and FIZZ1 gene expression were measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. *, p < 0.05 versus WT. (n = 3 per each group).

Because Cu,Zn-SODTg mice had a predominant M2 phenotype in their lungs compared with WT mice, we investigated whether this difference in macrophage polarization was transient or sustained after asbestos exposure. WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice were exposed to chrysotile asbestos and euthanized 10, 15, or 21 days after exposure. Alveolar macrophages were incubated in vitro with asbestos for 4 h, and M1 and M2 gene expression was measured. At each time point, Cu,Zn-SODTg mice had significantly greater expression of the M2 markers arginase I and FIZZ1 and decreased expression of the M1 marker TNF-α compared with WT mice, suggesting that Cu,Zn-SOD induced an M2 phenotype polarization (Fig. 3, D–F).

The metabolic utilization of l-arginine differs in M1 and M2 macrophages, so we determined if Cu,Zn-SOD modulated this metabolic distinction. Macrophages were exposed to chrysotile asbestos, and nitrite production was measured. Asbestos increased nitrite concentration in macrophages from both WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice; however, the nitrite produced from Cu,Zn-SODTg macrophages was significantly less compared with that of WT mice in both the presence and absence of chrysotile (Fig. 3G). In contrast, Cu,Zn-SOD overexpression dramatically altered l-arginine metabolism by significantly increasing arginase activity as measured by urea generation (Fig. 3H). In aggregate, these data suggest that Cu,Zn-SOD modulates metabolism of l-arginine in a manner characteristic of the M2 phenotype.

To support the notion that Cu,Zn-SOD can induce alternative activation of macrophages independent of Th2 cytokine signaling, we incubated macrophages from WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice with BAL fluid collected from asbestos-exposed WT mice to investigate whether other factors contributed to macrophage polarization. Macrophages from Cu,Zn-SODTg mice had increased arginase I and FIZZ1 and decreased TNF-α and IL-1β compared with those from WT mice cultured in the presence of BAL fluid (Fig. 3I), which suggests that Cu,Zn-SOD is primarily responsible for modulating the macrophage phenotype.

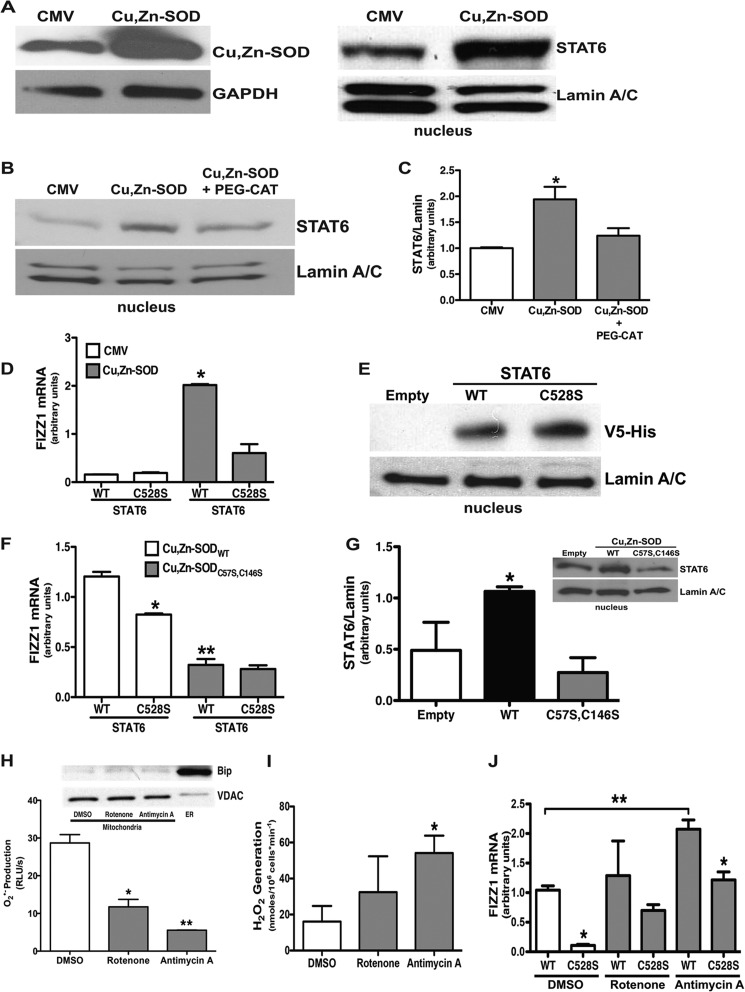

Cu,Zn-SOD Mediates M2 Polarization via Activation of STAT6

STAT6 is a member of the STAT family of transcription factors that regulates Th2 cytokine-induced gene expression during M2 polarization. To investigate the effect of Cu,Zn-SOD on STAT6, macrophages were infected with a replicative-deficient adenovirus containing either an empty or Cu,Zn-SOD vector. Cells infected with Ad5.Cu,Zn-SOD had significantly greater Cu,Zn-SOD expression compared with cells infected with the empty vector (Fig. 4A). Immunoblot analysis for STAT6 in the nuclear extract revealed that cells overexpressing Cu,Zn-SOD had a significant increase of STAT6 in the nucleus compared with the cells expressing an empty vector (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Cu,Zn-SOD mediates macrophage M2 polarization via activation of STAT6. A, macrophages were infected with a replication-deficient adenovirus vector expressing either an empty vector (CMV) or Cu,Zn-SOD vector (Cu,Zn-SOD) for 48 h. Immunoblot analysis for Cu,Zn-SOD overexpression (left) is shown. Nuclear fractions were isolated, and immunoblot analysis for STAT6 was performed (right). B, macrophages were infected with a replication-deficient adenovirus vector expressing either an empty vector (CMV) or Cu,Zn-SOD vector (Cu,Zn-SOD) for 24 h. Cells were cultured for an additional day in the presence or absence of PEG-CAT. Nuclear fractions were isolated, and immunoblot analysis for STAT6 was performed. C, shown is the ratio of densitometry of nuclear STAT6 expression to lamin A/C. n = 4. *, p < 0.05 versus CMV and Cu,Zn-SOD+PEG-CAT. D, macrophages were infected with a replication-deficient adenovirus vector expressing either an empty vector (CMV) or Cu,Zn-SOD vector (Cu,Zn-SOD) for 24 h. After 24 h, cells were transfected with either STAT6WT or STAT6C528S vectors for 24 h. Total RNA from macrophages was isolated, and FIZZ1 gene expression was measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. n = 4. *, p < 0.05 Cu,Zn-SOD with STAT6WT versus all other groups. E, macrophages were transfected with either an empty, STAT6WT, or STAT6C528S vector, and nuclear fractions were isolated. Immunoblot analysis for V5-His was performed. F, macrophages were co-transfected with either Cu,Zn-SOD-V5-HisWT or Cu,Zn-SOD-V5-HisC57S,C147S vector with either STAT6WT or STAT6C528S vector for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated, and FIZZ1 gene expression was measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. n = 4. *, p < 0.05 Cu,Zn-SODWT+STAT6WT versus Cu,Zn-SODWT+STAT6C528S. **, p < 0.05 Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C147S+STAT6WT versus Cu,Zn-SODWT+STAT6WT. G, macrophages were transfected with STAT6WT vector with either an empty, Cu,Zn-SODWT, or Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S vector, and nuclear fractions were isolated. The ratio of densitometry of nuclear STAT6 expression to lamin A/C was performed. n = 3. *, p < 0.05 versus empty and Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S. Inset, shown is a representative immunoblot analysis for STAT6 and lamin A/C. H, macrophages were treated with either 10 μm rotenone or 10 μm antimycin A overnight. Cell lysates (10 μg) were used for measuring superoxide anion generation utilizing lucigenin assay. n = 3. *, p < 0.05, rotenone versus DMSO. n = 3. **, p < 0.05, antimycin A versus DMSO. Inset, a representative immunoblot analysis for Bip and VDAC in the mitochondrial fractionations is shown. I, macrophages were treated with DMSO vehicle, 10 μm rotenone, or 10 μm antimycin A overnight. H2O2 production was measured by pHPA assay. *, p < 0.05, antimycin A versus DMSO. J, macrophages were transfected with either STAT6WT or STAT6C528S vector. 12 h later cells were treated with either vehicle (DMSO), 10 μm rotenone, or antimycin A for another 12 h. Total RNA from macrophages was isolated, and FIZZ1 gene expression was measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. *, p < 0.05 versus STAT6WT in DMSO- and antimycin A-treated cells (n = 3). **, p < 0.05 versus STAT6WT+DMSO (n = 3).

STAT6 Is Redox Regulated by Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2

Because Cu,Zn-SOD regulates macrophage mitochondrial H2O2 generation, we investigated whether STAT6 nuclear translocation was modulated by Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2. Macrophages were infected with a replication-deficient adenoviral vector expressing either an empty or Cu,Zn-SOD construct. After 48 h, cells were cultured in the presence or absence of PEG-CAT, and nuclear proteins were isolated. Cells expressing Cu,Zn-SOD cultured with PEG-CAT had a significant decrease in nuclear STAT6 localization to near control levels (Fig. 4B). To demonstrate this difference in a quantitative manner, densitometry of STAT6 was compared with lamin A/C in three separate experiments and was expressed graphically as a ratio (Fig. 4C).

Because STAT6 translocation was modulated by H2O2 and cysteine residues are critical targets for H2O2 (7, 20), we mutated Cys528 in the SH2 domain, which is a region of STAT6 necessary for DNA binding and transcriptional activation (9). Macrophages were infected with either an empty or Cu,Zn-SOD adenoviral vector. The cells were transfected the following day with either STAT6WT or STAT6C528S. After 24 h, FIZZ1 gene expression was determined. Overexpression of STAT6WT in cells expressing Cu,Zn-SOD significantly increased FIZZ1 gene expression compared with cells expressing the empty adenoviral vector (Fig. 4D). In contrast, STAT6C528S in cells expressing Cu,Zn-SOD decreased FIZZ1 gene expression near the level of cells expressing the empty vector with either STAT6WT or STAT6C528S.

To verify that the STAT6 mutation did not alter nuclear translocation, cells were transfected with an empty vector, STAT6WT, or STAT6C528S, and nuclear extracts were isolated. WT and C528S vectors were equally expressed in the nucleus as shown by immunoblot analysis for the tagged STAT6 vector (Fig. 4E). These data suggest that STAT6 nuclear translocation and the transcriptional activity is redox-regulated, and STAT6-dependent gene expression requires a critical cysteine in the SH2 domain.

STAT6-driven M2 Gene Expression Requires Cu,Zn-SOD

Because Cu,Zn-SOD activity in asbestos-exposed macrophages is localized to the mitochondria and requires two critical cysteine residues, Cys57 and Cys146 (7), we asked if overexpression of a catalytically inactive mutant (C57S,C146S) Cu,Zn-SOD would reduce M2 gene expression. Cells were transfected with either STAT6WT or STAT6C528S in combination with either Cu,Zn-SODWT or the catalytically inactive Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S vector. FIZZ1 gene expression was significantly reduced in cells expressing STAT6C528S compared with the STAT6WT in cells expressing the active Cu,Zn-SOD vector (Fig. 4F). In contrast, FIZZ1 gene expression was completely abolished in all cells expressing the Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S, which is catalytically inactive.

To determine if active Cu,Zn-SOD expression and activity was necessary for STAT6 nuclear translocation, macrophages were transfected with STAT6WT and either an empty vector, Cu,Zn-SODWT, or Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S. STAT6WT was significantly increased in cells expressing the active Cu,Zn-SOD, whereas STAT6 nuclear translocation was dramatically reduced below control levels in cells expressing the Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S (Fig. 4G). This difference is shown in a quantitative manner with densitometry of STAT6 compared with lamin A/C in three separate experiments and is expressed graphically as a ratio. A representative immunoblot analysis is shown (Fig. 4G, inset).

To validate the importance of Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated redox regulation in STAT6-dependent gene expression, we inhibited O2˙̄ generation using mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitors. Rotenone (10 μm) and antimycin A (10 μm) inhibit mitochondrial electron transport chain complex I and III, respectively, and are the primary sites of mitochondrial O2˙̄ production (21, 22). Similar to previously reported data using mitochondrial inhibitors on alveolar macrophages (23), rotenone reduced O2˙̄ production to 50% compared with vehicle-treated cells, and antimycin A had an even greater effect decreasing O2˙̄ production to ⅓ of the cells treated with the vehicle (Fig. 4H). Fractionation controls of the mitochondria are shown by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4H, inset).

Because Cu,Zn-SOD reduced O2˙̄ levels and increased H2O2, we investigated whether rotenone and antimycin A had similar effects (24, 25). Antimycin A treatment significantly increased H2O2 production compared with vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 4I). In contrast, H2O2 production was not altered in rotenone-treated cells.

To determine the effect of these inhibitors on FIZZ1 gene expression, macrophages were transfected with either STAT6WT or STAT6C528S. The following day cells were cultured in the presence of either vehicle, rotenone, or antimycin A. FIZZ1 gene expression was significantly inhibited in cells expressing the STAT6 mutant (C528S) compared with the WT in the presence of vehicle and antimycin A (Fig. 4J). Similar to Cu,Zn-SOD overexpression, antimycin A significantly increased FIZZ1 expression compared with cells treated with vehicle. Taken together, these observations that increased H2O2 production in cells treated with antimycin A support our previous data that Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 production is closely linked to complex III activity (7). Furthermore, these data suggest that oxidative stress in part modulates M2 gene expression.

Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 Modulates Macrophage Polarization

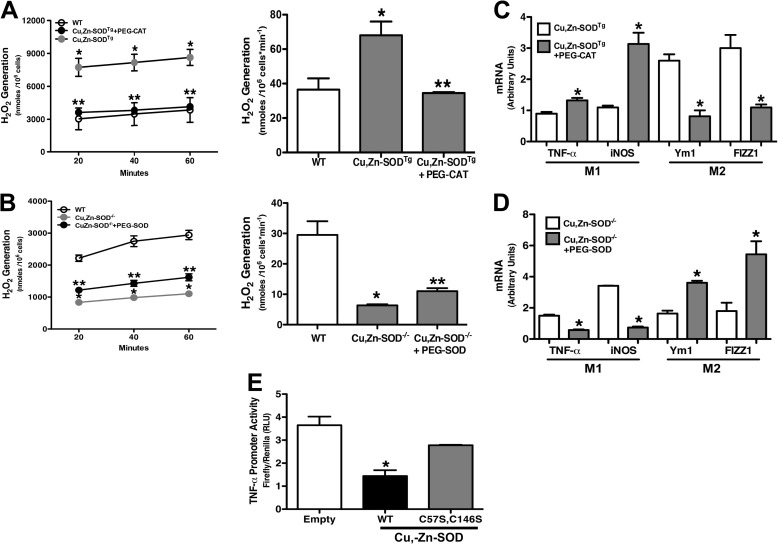

Because the primary enzymatic activity of Cu,Zn-SOD is the dismutation of O2˙̄ into H2O2, we questioned whether H2O2 levels contributed to macrophage polarization. To examine the role of Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 on macrophage polarization, we cultured macrophages from WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice in the presence or absence of PEG-CAT (100 units/ml) and measured H2O2 generation. Macrophages treated with PEG-CAT had lower H2O2 levels, similar to the level in WT macrophages. The rate of H2O2 generation was nearly 5-fold less in cells cultured with PEG-CAT (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Cu,Zn-SOD modulates M1/M2 polarization via H2O2 levels. A, macrophages isolated from WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice were cultured in the presence or absence of 100 units/ml PEG-CAT overnight and then treated with chrysotile asbestos. H2O2 generation was measured by pHPA assay (left). The rate of H2O2 generation is expressed in nmol/106 cells/min (right). n = 3. *, p < 0.05 Cu,Zn-SODTg versus WT; **, p < 0.05 Cu,Zn-SODTg+PEG-CAT versus Cu,Zn-SODTg. B, macrophages isolated from WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice were cultured in the presence or absence of 100 units/ml PEG-SOD for 3 h and then treated with chrysotile asbestos. H2O2 generation was measured by pHPA assay (left). Rate of H2O2 generation is expressed in nmol/106 cells/min (right). n = 3. *. p < 0.05 Cu,Zn-SOD−/− versus WT. **, p < 0.05 Cu,Zn-SOD−/−+PEG-SOD versus Cu,Zn-SOD−/−. C, total RNA from macrophages was isolated, and TNF-α, iNOS, FIZZ1, and Ym1 gene expression were measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. n = 4. *, p < 0.05 versus Cu,Zn-SODTg. D, total RNA from macrophages was isolated, and TNF-α, iNOS, FIZZ1, and Ym1 gene expression were measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. n = 4. *, p < 0.05 versus Cu,Zn-SOD−/−. E, macrophages were transfected with human TNF-α luciferase vector and either an empty vector, Cu,Zn-SOD-V5-HisWT, or Cu,Zn-SOD-V5-HisC57S,C147S vectors for 24 h and then exposed to chrysotile asbestos for 6 h. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured. Results are shown as firefly luciferase normalized to Renilla luciferase. n = 3. *, p < 0.05 WT versus empty and C57S,C146S mutant.

To further investigate the effect of Cu,Zn-SOD on H2O2 generation, alveolar macrophages from WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice were incubated in the presence or absence of PEG-SOD (100 units/ml). PEG-SOD significantly increased H2O2 levels compared with Cu,Zn-SOD−/− macrophages alone (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate the importance of Cu,Zn-SOD in regulating the redox state of macrophages.

We next determined the effect of H2O2 generation on M1/M2 gene expression. Cu,Zn-SODTg macrophages treated with PEG-CAT, which produced less H2O2, had decreased Ym1 and FIZZ1 gene expression and augmented TNF-α and iNOS gene expression (Fig. 5C). Because reducing H2O2 levels decreased M2 gene expression, we investigated whether increasing H2O2 would restore M2 gene expression. Cu,Zn-SOD−/− alveolar macrophages treated with PEG-SOD had significantly increased Ym1 and FIZZ1 gene expression, whereas it abolished M1 gene expression, as measured by TNF-α and iNOS (Fig. 5D). These observations suggest that Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 is a critical determinant of the macrophage phenotype.

To further examine the role of Cu,Zn-SOD-induced H2O2 generation on macrophage phenotype, we tested whether cells overexpressing the catalytically inactive mutant (C57S,C146S) Cu,Zn-SOD would enhance M1 gene expression. Cells were transfected with either an empty vector, Cu,Zn-SODWT, or Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S together with a TNF-α promoter reporter. TNF-α promoter activity was greatly reduced in cells expressing the Cu,Zn-SODWT compared with cells expressing the empty vector (Fig. 5E). In contrast, TNF-α promoter activity was recovered to near control levels in cells expressing the catalytically inactive mutant, Cu,Zn-SODC57S,C146S, compared with cells expressing the Cu,Zn-SODWT. Taken together, these data demonstrate that Cu,Zn-SOD regulates TNF-α promoter activity in a redox-dependent manner. Furthermore, these observations suggest that modulation of Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated mitochondrial H2O2 levels can alter macrophage polarization.

Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated M2 Polarization Accelerates the Development of Pulmonary Fibrosis

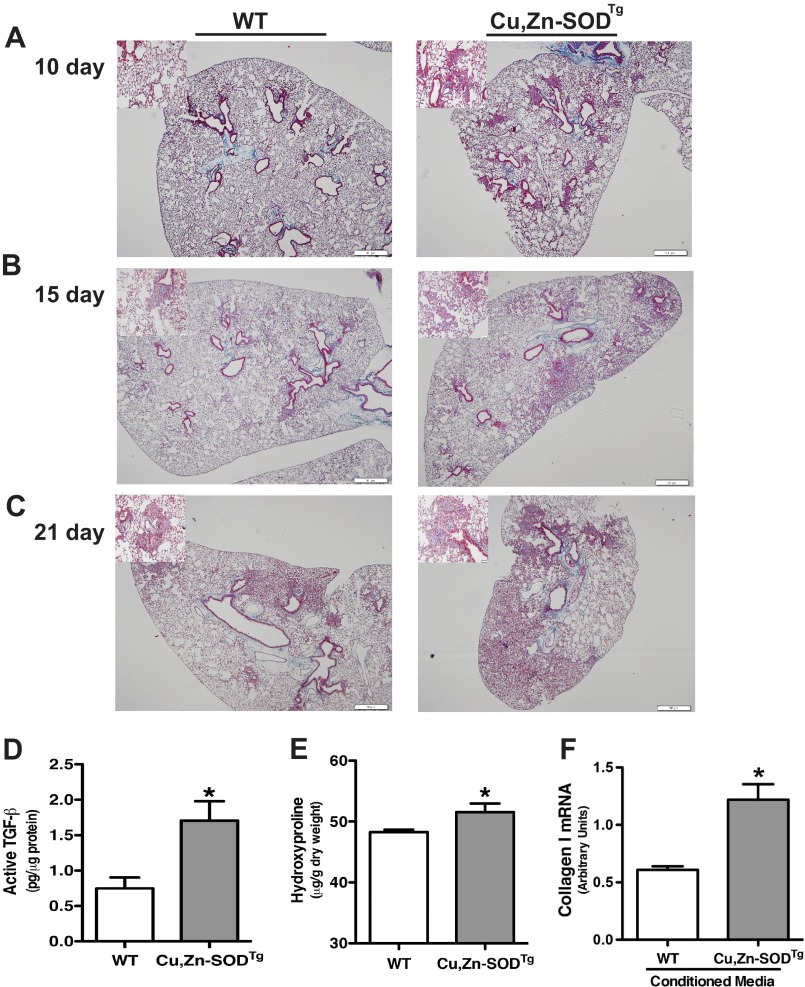

To determine the biological relevance of Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated alternative activation of macrophages in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis, we exposed WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice to chrysotile asbestos. The animals were euthanized 10, 15, and 21 days after exposure, and lungs were excised and processed for staining with Masson's trichrome to assess collagen deposition. The lungs of Cu,Zn-SODTg mice had collagen deposition in the peribronchial portions of the lung at day 10, whereas there was no evidence of collagen deposition in the lungs of WT mice (Fig. 6A). The fibrotic lesions progressed dramatically in a time-dependent manner in Cu,Zn-SODTg mice with parenchymal collagen deposition, whereas the lungs of WT mice showed small areas of peribronchial collagen at 15 days (Fig. 6B). At 21 days after asbestos exposure, the lungs of Cu,Zn-SODTg mice revealed dense fibrosis in the majority of the lung (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the WT mice had some peribronchial and parenchymal collagen deposition, but it was not nearly as wide-spread as seen in the Cu,Zn-SODTg mice.

FIGURE 6.

Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated M2 polarization accelerates pathogenesis of asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis in vivo. WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice were exposed to 100 μg of chrysotile asbestos intratracheally. 10 (A), 15 (B), and 20 (C) days later the animals were euthanized, and lungs were removed and processed for collagen deposition using Masson's trichome staining. Representative micrographs of one of five animals per genotype at each time point are shown. Magnification, 4×; the bar indicates 500 μm. Insets are representative micrographs at magnification 20×; the bar indicates 50 μm. D, active TGF-β in BAL fluid was measured. (n = 4 per each group. *, p < 0.05 versus WT. E, extracellular collagen deposition in lung of WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice 21 days after asbestos exposure were determined using hydroxyproline assay. *, p < 0.05 versus WT. n = 3 per each group. F, WT mouse lung fibroblasts were treated with conditioned media from either WT or Cu,Zn-SODTg macrophages overnight in the presence of asbestos. Total RNA from macrophages was isolated, and collagen I gene expression was measured. Results show arbitrary units normalized to β-actin mRNA. n = 3. *, p < 0.05 versus WT.

TGF-β is an important marker of M2-phenotype macrophages, and its expression in the activated form is linked to the pathogenesis of fibrosis. We measured the level of activated TGF-β in BAL fluid from WT and Cu,Zn-SODTg mice. Active TGF-β was significantly higher in Cu,Zn-SODTg compared with WT mice, indicating a dominant pro-fibrotic environment and M2 macrophage polarization (Fig. 6D).

To further verify the histopathological observations, we performed a hydroxyproline assay to determine the extent of pulmonary fibrosis biochemically. Hydroxyproline levels in the lung were significantly higher in Cu,Zn-SODTg mice compared with WT mice, indicating increased collagen deposition and more extensive pulmonary fibrosis (Fig. 6E). Because fibroblasts are the main source of collagen production and to provide a direct link between Cu,Zn-SOD and pulmonary fibrosis, we treated primary WT mouse lung fibroblasts with conditioned media from either WT or Cu,Zn-SODTg macrophages in the presence of asbestos overnight. Total RNA was isolated from mouse lung fibroblasts, and collagen I mRNA was measured. Mouse lung fibroblasts exposed to conditioned media from Cu,Zn-SODTg macrophages had a significant increase in collagen I gene expression compared with fibroblasts treated with conditioned media from WT macrophages (Fig. 6F). In aggregate, these data demonstrate that Cu,Zn-SOD induced macrophage M2 polarization and accelerated the development pulmonary fibrosis by increasing fibroblast collagen production.

DISCUSSION

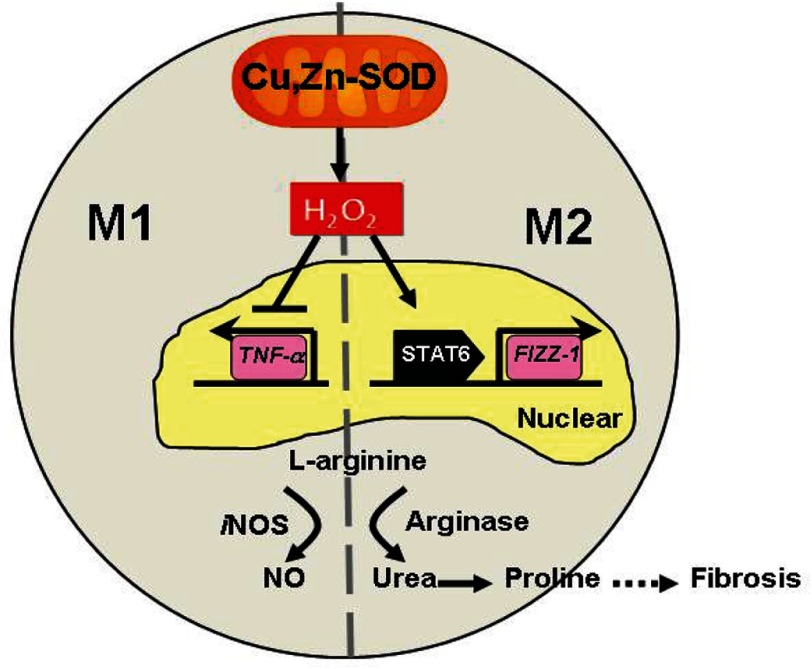

Macrophages have a critical role in both innate and adaptive immune responses. Macrophages not only initiate and accentuate inflammatory responses after tissue injury, but they are also involved in resolution and repair of the inflammation and injury. This distinction in macrophage activity is the result of a differentiation process that leads to a predominant proinflammatory M1 phenotype (classically activated) or an anti-inflammatory M2 (alternatively activated) phenotype. The M2 macrophages are also considered pro-fibrotic in certain conditions. Aberrant healing often occurs when an imbalance in the macrophage phenotype is present with a dominant M2 polarization. This imbalance can occur in multiple tissues, including the lung during the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Because Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 is crucial for the fibrogenic process in asbestos-induced pulmonary injury, we hypothesized that Cu,Zn-SOD modulated the macrophage phenotype. In this study we demonstrate that overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD polarized macrophages to an M2 phenotype independent of Th2 cytokine stimulation. Furthermore, modulating the redox level of the cell altered the macrophage phenotype. Evidence to support this mechanism include the following: (i) Cu,Zn-SOD−/− macrophages have increased M1 markers compared with WT macrophages independent of Th2 cytokines; (ii) Cu,Zn-SODTg macrophages polarized toward an M2 phenotype compared with WT macrophages; (iii) an increase in H2O2 levels by mitochondrial-localized Cu,Zn-SOD shifts the polarization pattern to an M2 phenotype; (iv) Cu,Zn-SOD mediates M2 polarization by modulation of STAT6 nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity in a redox-dependent manner; and (v) overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD leads to a pro-fibrotic environment and results in accelerated development of the fibrotic phenotype in vivo. These observations provide novel insight into the mechanism orchestrating macrophage activation and signify the importance of alternatively activated macrophages in pulmonary fibrosis (Fig. 7). Furthermore, understanding the molecular mechanism(s) that results in and accelerates fibrotic repair offers a target for potential therapeutic intervention.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic of Cu-Zn-SOD-dependent polarization of macrophages to the M2 phenotype. Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated H2O2 suppresses the M1 and activates the M2 macrophage phenotype by inhibiting the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α) and promoting, via STAT6, the transcription of pro-fibrotic factors, respectively. In M2 macrophages, l-arginine is preferentially metabolized by arginase I to urea. The subsequent production of proline leads to increased collagen deposition and fibrosis.

Studies have linked the role of Th2 cytokines and alternatively activated macrophages in fibrotic disease development (26, 27); however, it is not known whether a Th2 cytokine-independent pathway can lead to the development of fibrosis. The development of granulomas from Schistosoma mansoni exposure was not impaired in IL-4-deficient mice (28, 29), although other Th2 cytokines remained elevated. In addition, wound macrophages are known to undergo alternative activation despite a deficiency of Th2 cytokines in the wound environment, and the macrophage phenotype was sustained in mice lacking IL-4Rα (30). It is not clear from this study what induced the alternative activation. Our data are the first to demonstrate a molecular mechanism that mediates alternative activation of macrophages in a Th2-independent manner, which is contingent on the redox state of the cell.

STAT6 is critical for M2 cytokine production and granuloma formation in S. mansoni-induced hepatic injuries, as STAT6−/− mice fail to generate Th2 cytokines and have attenuated liver damage (31, 32). ROS generation is causally linked to STAT6 activation in certain cell lines; however, controversy remains whether STAT6 activation promotes ROS generation or STAT6 activation is downstream of ROS production (33, 34). We found that overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD modulates STAT6 translocation to the nucleus to initiate M2 gene transcription, which is dependent on the redox status of Cys528 in the SH2 domain of STAT6. Our data showed that despite similar Th2 cytokine levels in WT and Cu,Zn-SOD−/− mice, alveolar macrophage polarization patterns are differentially regulated. Increased levels of Cu,Zn-SOD resulted in a predominant M2 phenotype, whereas its absence was associated with an M1 phenotype. The redox regulation of STAT6 activation and M2 gene expression by Cu,Zn-SOD provide a novel mechanism of macrophage alternative activation in a Th2-independent manner.

Oxidative stress has long been known to play an important role in the development and progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Pro-inflammatory M1 genes, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and iNOS, have all been shown to be regulated by redox proteins, including Cu,Zn-SOD (35–37). Recently, Ym1 and FIZZ1 have emerged as oxidative stress proteins in pulmonary disease (38); however, the involvement of the redox status in modulating the macrophage phenotype is poorly understood. Previous studies have shown that increases in the oxidative metabolic environment fuels alternative activation of macrophages (39), whereas others show that M2 macrophages generate low levels of ROS (40). No study has shown that the redox status of the macrophage can directly regulate the macrophage phenotype. Circulating M2 cells accelerate the pathological progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a disease characterized with aberrant Cu,Zn-SOD function and excessive oxidative stress (41). One previous study demonstrated that increasing Mn-SOD activity in mitochondria enhanced electron transfer to oxygen to form O2˙̄ that is reduced to H2O2 (6); however, the ability of increasing Cu,Zn-SOD levels to facilitate higher H2O2 generation is not known. Our study is the first to demonstrate that Cu,Zn-SOD, the redox protein that catalyzes the generation of H2O2, polarizes macrophages to an M2 phenotype. Moreover, Cu,Zn-SOD-mediated macrophage polarization can be altered by modulating H2O2 generation, which suggests one mechanism by which oxidative stress is linked to pulmonary fibrosis.

Differential metabolism of l-arginine is characteristic of M1 and M2 macrophages (42). We found that overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD leads to a reduction of iNOS gene expression and NO synthesis, whereas arginase I expression and urea generation was enhanced. The l-arginine metabolic pattern is closely associated with collagen synthesis and fibrosis development. Overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD has been shown to inhibit iNOS expression in endothelial cells in a subarachnoid hemorrhage model (43); however, arginase I expression and urea production were not determined. Although arginase I expression is commonly linked to alternative activation of macrophages, one report found that arginase I was induced by Toll-like receptor activation to suppress NO production in M1 macrophages to prevent clearance of intracellular pathogens independent of STAT6 (44). The mechanism of Cu,Zn-SOD-induced differential arginase I and iNOS expression was unique in that it is dependent on the redox regulation of the STAT6 pathway. Furthermore, Cu,Zn-SODTg mice had early and sustained M2 gene expression and pro-fibrotic factor synthesis, which accelerated fibrosis development. These observations provide potential therapeutic targets that are modulated by oxidative stress.

M2 macrophages are known to be prevalent in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis, and systemic sclerosis (45). We found that alveolar macrophages obtained from asbestosis patients have higher M2 macrophage markers compared with normal volunteers, and C-C motif ligand 18 is known to induce lung fibroblast collagen production (46). In support of the fact that alveolar macrophages from asbestosis patients have increased Cu,Zn-SOD activity and generate higher levels of H2O2 (7), we also found in patients with asbestosis that the source of ROS generation was the mitochondria, that Cu,Zn-SOD was localized in the mitochondria of alveolar macrophages, and that these alveolar macrophages have an M2 phenotype. Furthermore, overexpression of Cu,Zn-SOD resulted in a dominant M2 phenotype, which accelerates fibrogenesis in a murine model of asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cu,Zn-SOD increased expression of active TGF-β and modulated intracellular l-arginine metabolism to generate proline, both of which facilitate development of pulmonary fibrosis. In aggregate, these observations provide evidence that Cu,Zn-SOD mediates pulmonary fibrosis in part via the early and sustained alternative activation of macrophages. Thus, intervening in this pathway may serve to prevent the development and/or progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chantal Allamargot and the Central Microscopy Research Facilities at the University of Iowa for assistance with immunohistochemistry, Garry R. Buettner, Brett Wagner, and the Electron Spin Resonance Facility at the University of Iowa for assistance with nitrite measurement, and Douglas R. Spitz for the helpful review and discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants 2R01ES015981-06 and R01ES014871. This work was also supported by a Merit Review from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Grant 1BX001135-01.

- iNOS

- inducible NOS

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase

- SH2

- Src homology domain 2

- pHPA

- p-hydroxylphenyl acetic acid

- BAL

- bronchoalveolar lavage

- VDAC

- voltage-dependent anion channel protein

- TEMED

- N,N,N',N'-tetramethylethylenediamine

- CAT

- catalase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Selman M., King T. E., Pardo A. (2001) Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann. Intern Med. 134, 136–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martinez F. O., Helming L., Gordon S. (2009) Alternative activation of macrophages. An immunologic functional perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 451–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gordon S., Martinez F. O. (2010) Alternative activation of macrophages. Mechanism and functions. Immunity 32, 593–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fridovich I., Freeman B. (1986) Antioxidant defenses in the lung. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 48, 693–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Okado-Matsumoto A., Fridovich I. (2001) Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver. Cu,Zn-SOD in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 38388–38393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buettner G. R., Ng C. F., Wang M., Rodgers V. G., Schafer F. Q. (2006) A new paradigm. Manganese superoxide dismutase influences the production of H2O2 in cells and thereby their biological state. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 41, 1338–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He C., Murthy S., McCormick M. L., Spitz D. R., Ryan A. J., Carter A. B. (2011) Mitochondrial Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase mediates pulmonary fibrosis by augmenting H2O2 generation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 15597–15607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heller N. M., Qi X., Junttila I. S., Shirey K. A., Vogel S. N., Paul W. E., Keegan A. D. (2008) Type I IL-4Rs selectively activate IRS-2 to induce target gene expression in macrophages. Sci. Signal. 1, ra17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daniel C., Salvekar A., Schindler U. (2000) A gain-of-function mutation in STAT6. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14255–14259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trede N. S., Tsytsykova A. V., Chatila T., Goldfeld A. E., Geha R. S. (1995) Transcriptional activation of the human TNF-α promoter by superantigen in human monocytic cells. Role of NF-κB. J. Immunol. 155, 902–908 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murthy S., Ryan A., He C., Mallampalli R. K., Carter A. B. (2010) Rac1-mediated mitochondrial H2O2 generation regulates MMP-9 gene expression in macrophages via inhibition of SP-1 and AP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25062–25073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carter A. B., Monick M. M., Hunninghake G. W. (1998) Lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine release in human alveolar macrophages is PKC-independent and TK- and PC-PLC-dependent. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 18, 384–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tephly L. A., Carter A. B. (2007) Constitutive NADPH oxidase and increased mitochondrial respiratory chain activity regulate chemokine gene expression. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 293, L1143–L1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ponnappa B. C., Dormer R. L., Williams J. A. (1981) Characterization of an ATP-dependent Ca2+ uptake system in mouse pancreatic microsomes. Am. J. Physiol. 240, G122–G129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murthy S., Adamcakova-Dodd A., Perry S. S., Tephly L. A., Keller R. M., Metwali N., Meyerholz D. K., Wang Y., Glogauer M., Thorne P. S., Carter A. B. (2009) Modulation of reactive oxygen species by Rac1 or catalase prevents asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 297, L846–L855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carter A. B., Hunninghake G. W. (2000) A constitutive active MEK → ERK pathway negatively regulates NF-κB-dependent gene expression by modulating TATA-binding protein phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27858–27864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oberley L. W., Spitz D. R. (1984) Assay of superoxide dismutase activity in tumor tissue. Methods Enzymol. 105, 457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Venkatachalam P., de Toledo S. M., Pandey B. N., Tephly L. A., Carter A. B., Little J. B., Spitz D. R., Azzam E. I. (2008) Regulation of normal cell cycle progression by flavin-containing oxidases. Oncogene 27, 20–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wakisaka Y., Chu Y., Miller J. D., Rosenberg G. A., Heistad D. D. (2010) Critical role for copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase in preventing spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage during acute and chronic hypertension in mice. Stroke 41, 790–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tephly L. A., Carter A. B. (2007) Differential expression and oxidation of MKP-1 modulates TNF-α gene expression. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 37, 366–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brand M. D., Affourtit C., Esteves T. C., Green K., Lambert A. J., Miwa S., Pakay J. L., Parker N. (2004) Mitochondrial superoxide. Production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 37, 755–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kussmaul L., Hirst J. (2006) The mechanism of superoxide production by NADH.ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7607–7612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rembish S. J., Trush M. A. (1994) Further evidence that lucigenin-derived chemiluminescence monitors mitochondrial superoxide generation in rat alveolar macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 17, 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boveris A., Chance B. (1973) The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem. J. 134, 707–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Quillet-Mary A., Jaffrézou J. P., Mansat V., Bordier C., Naval J., Laurent G. (1997) Implication of mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide generation in ceramide-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21388–21395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Postlethwaite A. E., Holness M. A., Katai H., Raghow R. (1992) Human fibroblasts synthesize elevated levels of extracellular matrix proteins in response to interleukin 4. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 1479–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chiaramonte M. G., Donaldson D. D., Cheever A. W., Wynn T. A. (1999) An IL-13 inhibitor blocks the development of hepatic fibrosis during a T-helper type 2-dominated inflammatory response. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 777–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chensue S. W., Warmington K., Ruth J. H., Lukacs N., Kunkel S. L. (1997) Mycobacterial and schistosomal antigen-elicited granuloma formation in IFN-g and IL-4 knockout mice. Analysis of local and regional cytokine and chemokine networks. J. Immunol. 159, 3565–3573 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pearce E. J., Cheever A., Leonard S., Covalesky M., Fernandez-Botran R., Kohler G., Kopf M. (1996) Schistosoma mansoni in IL-4-deficient mice. Int. Immunol. 8, 435–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Daley J. M., Brancato S. K., Thomay A. A., Reichner J. S., Albina J. E. (2010) The phenotype of murine wound macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87, 59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaplan M. H., Schindler U., Smiley S. T., Grusby M. J. (1996) Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells. Immunity 4, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaplan M. H., Whitfield J. R., Boros D. L., Grusby M. J. (1998) Th2 cells are required for the Schistosoma mansoni egg-induced granulomatous response. J. Immunol. 160, 1850–1856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mandal D., Fu P., Levine A. D. (2010) REDOX regulation of IL-13 signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Usage of alternate pathways mediates distinct gene expression patterns. Cell Signal. 22, 1485–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34. Hirakawa S., Saito R., Ohara H., Okuyama R., Aiba S. (2011) Dual oxidase 1 induced by Th2 cytokines promotes STAT6 phosphorylation via oxidative inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B in human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Immunol. 186, 4762–4770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chang S. C., Kao M. C., Fu M. T., Lin C. T. (2001) Modulation of NO and cytokines in microglial cells by Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 31, 1084–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marikovsky M., Ziv V., Nevo N., Harris-Cerruti C., Mahler O. (2003) Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase plays important role in immune response. J. Immunol. 170, 2993–3001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meissner F., Molawi K., Zychlinsky A. (2008) Superoxide dismutase 1 regulates caspase-1 and endotoxic shock. Nat. Immunol. 9, 866–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang L., Wang M., Kang X., Boontheung P., Li N., Nel A. E., Loo J. A. (2009) Oxidative stress and asthma. proteome analysis of chitinase-like proteins and FIZZ1 in lung tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J. Proteome Res. 8, 1631–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vats D., Mukundan L., Odegaard J. I., Zhang L., Smith K. L., Morel C. R., Wagner R. A., Greaves D. R., Murray P. J., Chawla A. (2006) Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1b attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 4, 13–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pelegrin P., Surprenant A. (2009) Dynamics of macrophage polarization reveal new mechanism to inhibit IL-1β release through pyrophosphates. EMBO J. 28, 2114–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vaknin I., Kunis G., Miller O., Butovsky O., Bukshpan S., Beers D. R., Henkel J. S., Yoles E., Appel S. H., Schwartz M. (2011) Excess circulating alternatively activated myeloid (M2) cells accelerate ALS progression while inhibiting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS ONE 6, e26921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Odegaard J. I., Chawla A. (2011) Alternative macrophage activation and metabolism. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6, 275–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saito A., Kamii H., Kato I., Takasawa S., Kondo T., Chan P. H., Okamoto H., Yoshimoto T. (2001) Transgenic Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase inhibits NO synthase induction in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 32, 1652–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. El Kasmi K. C., Qualls J. E., Pesce J. T., Smith A. M., Thompson R. W., Henao-Tamayo M., Basaraba R. J., König T., Schleicher U., Koo M. S., Kaplan G., Fitzgerald K. A., Tuomanen E. I., Orme I. M., Kanneganti T. D., Bogdan C., Wynn T. A., Murray P. J. (2008) Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1399–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pechkovsky D. V., Prasse A., Kollert F., Engel K. M., Dentler J., Luttmann W., Friedrich K., Müller-Quernheim J., Zissel G. (2010) Alternatively activated alveolar macrophages in pulmonary fibrosis-mediator production and intracellular signal transduction. Clin. Immunol. 137, 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prasse A., Pechkovsky D. V., Toews G. B., Jungraithmayr W., Kollert F., Goldmann T., Vollmer E., Müller-Quernheim J., Zissel G. (2006) A vicious circle of alveolar macrophages and fibroblasts perpetuates pulmonary fibrosis via CCL18. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173, 781–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]