Abstract

Objective:

Sexual-minority women are at heightened risk for a number of mental health problems, including hazardous alcohol consumption, depression, and anxiety. We examined self-medication and impaired-functioning models of the associations among these variables and interpreted results within a life course framework that considered the unique social stressors experienced by sexual-minority women.

Method:

Data were from a sample of 384 women interviewed during the first two waves of the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) study.

Results:

Covariance structure modeling revealed that (a) consistent with a self-medication process, anxiety was prospectively associated with hazardous drinking and (b) consistent with an impaired-functioning process, hazardous drinking was prospectively associated with depression.

Conclusions:

Our findings support a life course perspective that interprets the mental health of adult sexual-minority women as influenced by adverse childhood experiences, age at drinking onset, first heterosexual intercourse, and first sexual identity disclosure, as well as by processes associated with self-medication and impaired functioning during adulthood.

In recent years, there has been increased concern with the health of sexual-minority (lesbian, gay, bisexual) populations in the United States. In a follow-up to the 1999 report on lesbian health (Solarz, 1999), the Institute of Medicine recently released a more comprehensive report, The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding (Institute of Medicine, 2011). This historic report emphasizes the unique health needs of sexual minorities and the limited understanding of these needs. Indeed, research over the past decade has produced compelling evidence of mental health disparities among sexual-minority women, including a heightened risk of hazardous drinking (Drabble et al., 2005; McCabe et al., 2009), depression, and anxiety (Bostwick et al., 2010; Cochran and Mays, 2009; King et al., 2008). However, little attention has been paid to the social and psychological processes underlying these disparities. Studies that address these processes (Hughes et al., 2007; McCabe et al., 2010; Meyer, 2003) indicate that stress related to sexual-minority status plays an important role. In addition, recent research suggests that adverse childhood experiences, including childhood sexual and physical abuse, may help explain sexual-minority women’s heightened risk of hazardous drinking and psychological distress (Balsam et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2010a, 2010b).

Less understood are developmental characteristics that may influence the mental health of sexual minorities. Although most sexual minorities manage the process of identity development without serious consequences, the developmental stage at which this process occurs may function as a risk or protective factor for later negative mental health outcomes. In particular, coming out at a younger age may confer greater vulnerability to risky behaviors, such as earlier drinking onset (McCabe et al., 2013; Parks and Hughes, 2007). Indeed, studies have found that, compared with their heterosexual counterparts, sexual minorities report earlier ages at drinking onset (Corliss et al., 2008; S. C. Wilsnack et al., 2008) and first heterosexual intercourse (Blake et al., 2001;Saewyc etal., 1999).

Given the general reliance on cross-sectional research, the temporal nature and directional relationships of mental health processes among sexual-minority women have been largely unexplored. Evidence from general population samples, however, provides valuable insight. Available theories suggest that hazardous drinking may be a cause and a consequence of psychological distress. The forms of distress most commonly investigated are depression and anxiety—the most prevalent mental health conditions experienced by women (Satcher, 2000).

Alcohol use and depression

The association between alcohol use and depression is well documented and has been demonstrated to be stronger among women than men (Fleming et al., 2008; Grant and Harford, 1995). Historically, the most common explanation has been the self-medication hypothesis, which suggests that individuals use alcohol to self-medicate in an effort to alleviate depressive symptoms—placing them at increased risk for hazardous drinking (Graham et al., 2007; Peirce et al., 2000). Consistent with the social learning theory perspective, alcohol use in this context is interpreted as a coping mechanism that is invoked when other strategies have failed or are unavailable (Cooper et al., 1992; Holahan et al., 2001). Several longitudinal studies have found evidence consistent with the self-medication model (Moscato et al., 1997; Peirce et al., 2000; Repetto et al., 2004).

Hazardous drinking can also increase depressive symptoms (Jané-Llopis and Matytsina, 2006; Rao et al., 2000). The impaired-functioning model suggests that heavy drinking inhibits effective social functioning, which can harm personal relationships, threaten employment, and increase risk of accidents and vulnerability to victimization—all of which may serve as pathways to depression (Abraham and Fava, 1999; Newcomb et al., 1999). Physiological mechanisms also may contribute to this relationship, as depression may be a consequence of the toxic effects of alcohol on neurological functioning (Kuo et al., 2006; Merikangas et al., 1996; Stice et al., 2004) or the activation, via heavy alcohol use, of genetic markers associated with depression (Fergusson et al., 2008). Several investigators have reported prospective evidence supporting the impaired-functioning hypothesis of depression and alcohol use over the self-medication hypothesis (Fergusson et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2000; Rohde et al., 2001; Schutte et al., 1997; Stice et al., 2004).

Self-medication and impaired-functioning models are not mutually exclusive; alcohol consumption and depression can reinforce one another. Findings from several longitudinal studies suggest a transactional association between heavy alcohol use and depression in which each condition prospectively exacerbates the other (Gilman and Abraham, 2001; Locke and Newcomb, 2001; Marmorstein, 2009; Windle and Miller, 1990). Although a handful of researchers have found no evidence of a prospective association between the two (Fleming et al., 2008), with few exceptions (Kaplow et al., 2001) this research has not considered other forms of psychological distress, particularly anxiety, which is also known to be associated with hazardous drinking (Kushner et al., 1999; Regier et al., 1998).

Alcohol use and anxiety

Similar to associations between alcohol use and depression, co-occurring anxiety and hazardous drinking are more common among women (Grant et al., 2009; Merikangas et al., 1996) and are also often interpreted within a self-medication perspective (Buckner et al., 2008; Crum and Pratt, 2001; Zimmermann et al., 2003). Most longitudinal evidence regarding the association between anxiety and hazardous drinking supports this perspective (Buckner et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2004; Crum and Pratt, 2001; Goodwin et al., 2004; Kaplow et al., 2001; Schmidt et al., 2007; Zimmermann et al., 2003).

Consistent with the impaired-functioning model, symptoms of anxiety also may be a consequence of the many social and health-related problems associated with hazardous drinking. At least one prospective study has found a reciprocal relationship between anxiety and alcohol use disorders (Kushner et al., 1999), but there is less evidence of a prospective effect of alcohol use on anxiety (Jané-Llopis and Matytsina, 2006).

A life course perspective

Although a substantial body of research is now available, it rarely addresses the developmental processes and associated mental health outcomes of sexual-minority women. This is due in part to the lack of longitudinal studies of sexual-minority women’s health. This general absence of empirical evidence has been paralleled by insufficient development of theoretical models of these processes (Meyer, 2003). Here, we offer a life course conceptualization of the development of depression, anxiety, and hazardous drinking among adult sexual-minority women.

Adverse childhood experiences, such as childhood sexual abuse or having a parent with alcohol-related problems, are known to place individuals at risk for early onset of alcohol use and heterosexual intercourse (Dube et al., 2006; Hillis et al., 2001; Hughes et al., 2007). These early experiences increase risk of hazardous drinking (Hingson et al., 2006; Pitkänen et al., 2005) and negative mental health consequences, such as depression and anxiety.

For sexual-minority women, an additional risk factor is the process of sexual identity formation. The formation and disclosure of a nonheterosexual sexual identity are often powerfully stressful experiences associated with social stigma, parental and peer rejection, social and workplace discrimination, victimization, and psychological distress (Ryan et al., 2010; Weiss and Hope, 2011). Consistent with general population findings that have linked anxiety and later onset of first heterosexual intercourse (Capaldi et al., 1996; Zimmer-Gembeck and Helfand, 2008), anxiety and fear of rejection may prevent or delay disclosure of minority sexual identity (D’Augelli et al., 2010). Delayed or limited disclosure of sexual identity may consequently result in increased anxiety (Jordan and Deluty, 1998). In addition, experiences of discrimination and rejection associated with disclosure may lead to the development of depression, anxiety, and self-medication with alcohol. The impaired functioning associated with hazardous drinking may then contribute to increases in both anxiety and depression.

This life course perspective suggests developmental pathways that represent both general psychosocial processes and experiences that are unique to sexual minorities. In the research reported here, we used longitudinal data to investigate aspects of these developmental processes in a diverse sample of adult sexual-minority women. Available research led us to hypothesize that, among sexual-minority women: (1) adverse childhood experiences (childhood sexual abuse and parental drinking problems) are associated with earlier drinking onset and earlier first heterosexual intercourse (first sex); (2) earlier age at sexual orientation disclosure, earlier drinking onset, and earlier first sex are associated with higher levels of depression and hazardous drinking; (3) later age at sexual orientation disclosure, later drinking onset, and later first sex are associated with higher levels of anxiety; (4) higher levels of anxiety and depression are associated with higher levels of subsequent hazardous drinking, consistent with the self-medication model; and (5) higher levels of hazardous drinking are associated with higher levels of subsequent anxiety and depression, consistent with the impaired-functioning model. In exploring these hypotheses, we began to address the gaps in knowledge related to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health identified by the Institute of Medicine (2011; Solarz, 1999) and by the U.S. government (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010).

Method

Sample recruitment and retention

Data are from the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) study, a longitudinal project focusing on risk and protective factors for hazardous drinking among sexual-minority women. Sampling methods in the CHLEW study were designed to minimize limitations and maximize the strengths of volunteer samples. To minimize systematic bias and increase sample diversity, we used a variety of recruitment methods. Multiple recruitment sources included clusters of social (e.g., formal community-based organizations and informal social groups) and individual social networks, including those of women who participated in the study. The study was advertised in local newspapers and on flyers posted in churches and bookstores and distributed to individuals and organizations via formal and informal social events and networks. We especially targeted women who had been underrepresented in studies of lesbian health, including women of color, older lesbians, and lesbians of lower socioeconomic status. Eligible participants self-identified as lesbian, were 18 or older, spoke English, and resided in Chicago or surrounding suburbs. All participants provided written consent. The study protocol was approved by the University of Illinois Institution Review Board.

Both Wave 1 (2000–2001) and Wave 2 (2004–2005) data were collected in face-to-face interviews conducted by trained interviewers. Interviews lasted 1–2 hours. In Wave 1, 447 women were recruited and interviewed. Wave 2 interviews were conducted with 384 women—a response rate of 85.9% (87.9% of respondents who were still living and able to participate). Lost to follow-up were 33 (7.4%) women who could not be located, 10 (2.2%) who were deceased, 10 (2.2%) who refused, and 9 (2.0%) who were located but were unable to participate. One participant transitioned from female to male gender. Nonresponse rates were examined relative to all major drinking variables and seven demographic variables (age, race/ethnicity, education, income, employment status, relationship status, and having children living at home). We fit a logistic regression model to examine possible predictors of attrition. The only significant predictor of attrition was less than a high school education (odds ratio = 3.39, 95% CI [1.12, 10.2], p = .03).

In Wave 1, respondents were screened for eligibility with the question, “Understanding that sexual identity is only one part of your identity, do you consider yourself to be lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual, transgender, or something else?” Although the screening interview selected only women who self-identified as lesbians, in the main interview 11 women identified as bisexual, one as “queer,” and another refused to be labeled. In Wave 2, nearly twice as many women identified as bisexual (n = 21); 83 identified as mostly lesbian, 266 as lesbian, 7 as mostly heterosexual, 2 as heterosexual, and 5 as queer or something else (another label or “preferred not to be labeled”).

Survey questionnaires

The Wave 1 questionnaire was adapted from the National Study of Health and Life Experiences of Women (NSHLEW), a national study of women in the general population (R. W. Wilsnack et al., 2006; S. C. Wilsnack et al., 1991), to which we added additional questions about sexual orientation and sexual identity development milestones. The Wave 2 survey used measures of drinking behavior and drinking consequences identical to those in Wave 1.

Measures

Hazardous drinking.

We constructed a latent measure of hazardous drinking that combined indicators of heavier drinking and adverse consequences of drinking. We chose to use this combination of indicators because our longitudinal model included three outcome variables at each wave; separate variables for alcohol consumption and adverse consequences would have increased the number of model parameters to be estimated. In addition, because the community-based sample in the study had a relatively low prevalence of diagnosable alcohol use disorders, we preferred to use a composite measure of risky or hazardous drinking (heavier consumption and some adverse consequences) rather than diagnostic measures of alcohol abuse and dependence.

Two dichotomous indicators of hazardous drinking were heavy episodic drinking (one or more occasions of drinking six or more drinks in a day) and subjective intoxication (one or more occasions of having consumed “enough to feel drunk—that is, where drinking noticeably affected your thinking, talking, and behavior”)—based on past-12-month reports at each interview. The two other indicators were adverse drinking consequences (e.g., driving while drunk or high from alcohol, complaints about respondent’s drinking by her partner; range: 0–8) and symptoms of potential alcohol dependence (e.g., memory lapses [blackouts], inability to stop or reduce alcohol consumption over time; range: 0–5). Both measures were drawn from national drinking surveys (Calahan, 1970; Polich and Orvis, 1979) and were selected based on their prevalence in pretests of the NSHLEW.

Respondents were first asked whether they had ever experienced each of these problems. Those who answered affirmatively were then asked whether these experiences had occurred in the previous 12 months (for respondents who reported any drinking during these time frames). For both Waves 1 and 2, these measures were dichotomized (any vs. no adverse drinking consequences and any vs. no potential alcohol-dependence symptoms in the past 12 months). The KR-20 reliability coefficients for these indicators were 0.77 and 0.80 at Waves 1 and 2, respectively.

Depression.

Depressive symptoms were measured using questions from the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Robins et al., 1981). Respondents were asked about experiences of nine specific symptoms (e.g., decreased appetite, problems with sleeping, tired all the time, felt worthless) during their lifetime (at Wave 1) and since the last interview (at Wave 2). KR-20 reliability coefficients were 0.83 (at Wave 1) and 0.87 (at Wave 2).

Anxiety.

Six indicators were used to represent anxiety. Each was assessed using a 5-point Likert-type response format. The six items (e.g., worries a lot, can be tense, gets nervous easily) were adapted from the neuroticism scale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Eysenck and Eysenck, 1991). At each wave, respondents were asked about their current experience. Cronbach’s α for these indicators were .80 and .78, respectively, at Waves 1 and 2.

Parental drinking problems.

A respondent’s perceptions of whether her father and/or mother had experienced drinking problems during the time she was growing up were assessed by asking, “Did your [father/mother] ever have any problems due to [his/her] drinking, such as marriage or family problems, problems with the law, problems with work or health—any kind of problems related to [his/her] drinking?” Responses were coded as no parent (0), one parent (1), or both parents (2) with drinking problems.

Childhood sexual abuse.

We used a measure of self-perceived childhood sexual abuse. Respondents were asked, “Do you feel that you were sexually abused when you were growing up?” after a series of in-depth questions about childhood sexual experiences (S. C. Wilsnack et al., 1997, 2004). These questions inquired about a range of sexual experiences before age 18 that were used to classify women’s experiences based on Wyatt’s (1985) definitions of intrafamilial and extrafamilial childhood sexual abuse. We used a single self-perception question in the current analyses because 14% (n = 53) of the cases had insufficient information to classify them according to Wyatt’s criteria and because Wyatt’s definition likely captures some experiences considered consensual by the respondent. All of the women classified based on Wyatt’s criteria also reported self-perceived childhood sexual abuse.

Age at drinking onset.

Age at drinking onset was assessed using the question, “How old were you when you began to drink alcoholic beverages (more than just a sip), even if you were under age?” Responses were categorized as 10 years or younger, 11–12, 13–14, 15–16, 17–18, 19–20, and 21 years or older.

Age at first consensual heterosexual sexual intercourse.

Age at first heterosexual intercourse (age at first sex) was categorized as 11–12, 13–14, 15–16, 17–18, 19–20, and 21 years or older.

Age at first disclosure of sexual orientation.

To assess this sexual identity development milestone, respondents were asked, “How old were you when you first told someone you were lesbian/gay?” For these analyses, responses were categorized as 6–12, 13–16, 17–20, 21–24, 25–28, 29–32, and 33 years or older.

Race/ethnicity.

Respondents were classified as White (1) versus non-White (0).

Age.

Respondent age at baseline interview was measured in years. Frequency distributions or means for all study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means and frequencies of study variables (N = 384)

| Wave 1 |

Wave 2 |

|||

| Variable | n | % or M (SD) | n | % or M (SD) |

| Hazardous drinking indicatorsa (all indicators range: 0–1) | ||||

| Any drinking problem consequences | 82 | 21.4% | 96 | 25.0% |

| Any alcohol dependence symptoms | 87 | 22.7% | 95 | 24.7% |

| Any heavy episodic drinking | 98 | 25.5% | 96 | 25.0% |

| Intoxication | 210 | 54.7% | 186 | 48.4% |

| Depression indicatorsb (all indicators range: 0–1) | ||||

| Felt sad/blue | 276 | 71.9% | 220 | 57.3% |

| Lost appetite | 190 | 49.5% | 126 | 32.8% |

| Trouble sleeping | 262 | 68.2% | 233 | 60.7% |

| Tired out all the time | 268 | 69.8% | 231 | 60.2% |

| Moving all the time | 116 | 30.2% | 72 | 18.8% |

| Talked/moved slowly | 142 | 37.0% | 133 | 34.6% |

| Lost interest in sex | 252 | 65.6% | 217 | 56.5% |

| Felt worthless | 213 | 55.5% | 124 | 32.3% |

| Thinking was harder | 216 | 56.3% | 175 | 45.6% |

| Anxiety indicatorsc (all indicators range: 1–5) | ||||

| Relaxed, handles stress well (reversed) | 384 | 2.8 (1.3) | 384 | 2.5 (1.2) |

| Remains calm in tense situations (reversed) | 384 | 2.2 (1.1) | 384 | 2.1 (1.1) |

| Emotionally stable (reversed) | 383 | 2.3 (1.2) | 384 | 2.1 (1.1) |

| Nervous easily | 384 | 2.9 (1.3) | 384 | 2.7 (1.3) |

| Tense | 384 | 3.5 (1.2) | 384 | 3.3 (1.2) |

| Worries a lot | 384 | 3.6(1.3) | 384 | 3.3 (1.3) |

| Self-perceived childhood sexual abuse | 124 | 32.3 | ||

| Parental drinking problems | 134 | 34.9 | ||

| Age at drinking onset (range: 0–6) | ||||

| ≤10 years | 13 | 3.4% | ||

| 11–12 years | 28 | 7.3% | ||

| 13–14 years | 52 | 13.5% | ||

| 15–16 years | 96 | 25.0% | ||

| 17–18 years | 85 | 22.1% | ||

| 19–20 years | 42 | 10.9% | ||

| ≥21 years | 68 | 17.7% | ||

| Age at first sexual intercourse (range: 0–6) | ||||

| 11–12 years | 7 | 1.8% | ||

| 13–14 years | 25 | 6.5% | ||

| 15–16 years | 45 | 11.7% | ||

| 17–18 years | 86 | 22.4% | ||

| 19–20 years | 70 | 18.2% | ||

| ≥21 years | 149 | 38.8% | ||

| Age first disclosed sexual orientation (range: 0–6) | ||||

| 6–12 years | 8 | 2.1% | ||

| 13–16 years | 43 | 11.2% | ||

| 17–20 years | 117 | 30.5% | ||

| 21–24 years | 74 | 19.3% | ||

| 25–28 years | 49 | 12.8% | ||

| 29–32 years | 38 | 9.9% | ||

| 33–40 years | 32 | 8.3% | ||

| Race (White = 1) | 192 | 50.0% | ||

| Age in years (range: 18–83) | 384 | 37.9 (11.8) | ||

Hazardous drinking questions asked about past year experiences at Wave 1 and at Wave 2 interviews;

depression questions asked about lifetime experiences at Wave 1 interview and about experiences “since last interview” at Wave 2 interview;

anxiety questions asked about current experiences at Wave 1 and at Wave 2 interviews.

Analysis

We tested our hypotheses with covariance structure models using the mean and variance adjusted weighted least-squares method of estimation (Hayduk, 1987). A key advantage of covariance structure modeling is that it can be used to construct latent variable measures and to conduct path analyses simultaneously. The path analytic or structural component is appropriate for analyzing and describing time-ordered relationships among multiple variables in a single model. It also permits estimation of direct and indirect effects of the independent variables.

We estimated a path model that examined the effects of adverse childhood experiences on age-at-onset measures (first alcohol use, sexual intercourse, and sexual orientation disclosure) and subsequent effects of these experiences on hazardous drinking, anxiety, and depression. We also examined the longitudinal effects of hazardous drinking, anxiety, and depression on one another. All models were estimated using unweighted data with Mplus 6.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998).

Results

Description of sample

At baseline, the 447 women in the study ranged in age from 18 to 83 years (M = 37.5, SD = 11.7). Fewer than half (47%) identified as non-Hispanic White, 28% were Black non-Hispanic, 20% were Hispanic/Latina, and 5% were Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, or multiracial. Comparisons of respondents’ race/ethnicity with 2000 census data indicated that the sample closely reflected the distribution of the population in Cook County, Illinois, where the large majority of CHLEW respondents lived. In contrast to the general Cook County population, but similar to other lesbian samples, the respondents were well educated; 56% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. The majority of respondents worked full time at one (54%) or multiple jobs (14%). Eleven percent worked part time, and 20% were not employed. One fourth had annual household incomes of less than $20,000, whereas 21% had incomes of $75,000 or more. Most (67%) respondents were in a committed relationship with a female partner. Nearly one third had one or more children, and 19% had at least one child younger than age 18 living with them.

Measurement model

The measurement model used to construct latent measures of hazardous drinking, depression, and anxiety for each wave is presented in Table 2. Each of the four observed indicators of any past-year alcohol-problem consequences, alcohol-dependence symptoms, intoxication, and heavy episodic drinking loaded significantly on the hazardous drinking latent construct at each wave.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of indicators of latent constructs: Standardized coefficients

| Variable | Wave 1 | Wave 2 |

| Hazardous drinking | ||

| Any heavy episodic drinking | .841 | .840 |

| Any intoxication | .923 | .922 |

| Any drinking problem consequences | .873 | .872 |

| Any alcohol-dependence symptoms | .854 | .853 |

| Depression | ||

| Felt sad/blue | .899 | .909 |

| Lost appetite | .681 | .702 |

| Trouble sleeping | .743 | .762 |

| Tired out all the time | .810 | .825 |

| Moving all the time | .587 | .610 |

| Talked/moved slow | .763 | .781 |

| Lost interest in sex | .518 | .540 |

| Felt worthless | .808 | .824 |

| Thinking was harder | .795 | .811 |

| Anxiety | ||

| Nervousness or anxiety interfered with your everyday life or activities | .656 | .643 |

| Relaxed, handles stress well (reversed) | .716 | .705 |

| Remains calm in tense situations (reversed) | .611 | .599 |

| Emotionally stable (reversed) | .658 | .645 |

| Nervous easily | .649 | .637 |

| Tense | .584 | .571 |

| Worries a lot | .646 | .634 |

Notes: This measurement part of the model was simultaneously fitted with the structural part of the model. Autocorrelated errors (not shown) between Wave 1 and Wave 2 measures were specified to account for within-subject clustering.

Latent measures of depression and anxiety also were successfully developed. All factor loadings and correlated error terms for Waves 1 and 2 assessments of each indicator were constrained to be equal. All indicators loaded significantly on their respective latent measures at Waves 1 and 2. The overall measurement model was evaluated simultaneously with the structural model.

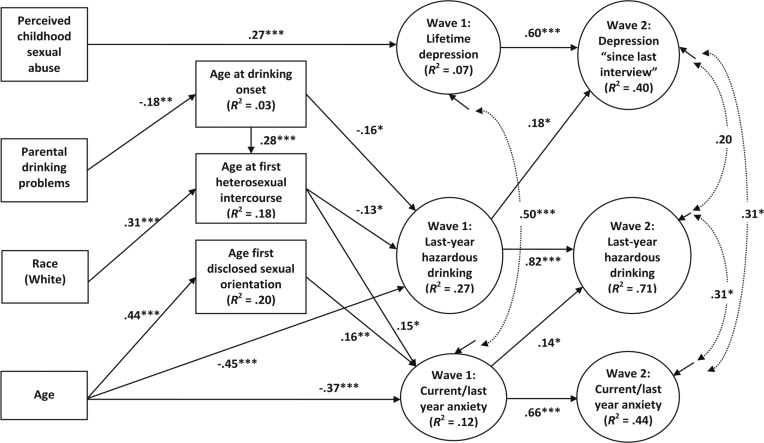

Structural model

A structural model was estimated to simultaneously assess each hypothesis. This model examined relationships among childhood experiences, adolescent experiences, and the hazardous drinking, depression, and anxiety latent measures assessed at two points in time. Nonsignificant paths were trimmed, resulting in the final model presented in Figure 1. Overall fit measures suggested a close fit between the specified model and the data, χ2(188) = 336.7, p < .0001; χ2/df = 1.79; root mean square error of approximation = .05; comparative fit index = .94; Tucker-Lewis index = .96. Although not depicted, autocorrelated errors between Wave 1 and 2 measures of each construct were specified to account for within-subject clustering.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal predictors of hazardous drinking, depression, and anxiety: Standardized coefficients. Model fit χ2(188) = 336.7, p < .0001; χ2/df = 1.79; root mean square error of approximation = .05; comparative fit index = .94; Tucker—Lewis index = .96.

*p < .05;

**p < .01;

***p < .001 (nondirectional).

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, women who reported parental drinking problems were more likely to report earlier drinking onset. Contrary to Hypothesis 1, childhood sexual abuse was not associated with any of the age-at-onset measures. Race was associated with age at first heterosexual sexual intercourse (White women were older when they first had sexual intercourse). Earlier age at drinking onset was also associated with earlier age at first sex. Older women in the sample first disclosed their minority sexual orientation at a later age.

Two age-at-onset measures were independently associated with hazardous drinking at Wave 1. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, levels of hazardous drinking were higher among women who reported earlier drinking onset and those who reported earlier age at first heterosexual sex. In addition, younger women reported higher levels of hazardous drinking at Wave 1.

In contrast, none of the age-at-onset measures were significantly associated with depression at Wave 1. Only childhood sexual abuse was independently associated with Wave 1 depression, suggesting that childhood sexual abuse directly influences adult depression, independent of any mediating processes. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was not supported for depression.

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, several age-at-onset measures were associated with Wave 1 anxiety. Later age at first sexual intercourse and later age at first sexual orientation disclosure were each independently associated with greater levels of anxiety. In addition, older sexual-minority women reported lower levels of anxiety.

Level of anxiety at Wave 1 was positively associated with hazardous drinking at Wave 2, controlling for Wave 1 hazardous drinking, a prospective association supportive of a self-medication process (Hypothesis 4). A similar process was not observed with depression, as Wave 1 depression levels were not associated with Wave 2 hazardous drinking.

The impaired-functioning model (Hypothesis 5) was partially supported. Wave 1 hazardous drinking levels were associated with Wave 2 levels of depression, after controlling for baseline depression. Wave 1 hazardous drinking was not associated with Wave 2 anxiety. Hence, among sexual-minority women in this sample, prospective analyses suggested that symptoms of anxiety may lead to self-medication via hazardous drinking, and hazardous drinking may be associated with impaired functioning and heightened risk of depression.

Discussion

Although research has demonstrated that sexual-minority women are at heightened risk for hazardous drinking and psychological distress, relatively little is known about the social and behavioral processes associated with these risks. We examined a theoretical model of potential precursors of negative mental health in this population. Taken as a whole, findings support a life course perspective that interprets the mental health of adult sexual-minority women as being associated with adverse childhood experiences (Hypothesis 1), the timing of drinking onset, first heterosexual intercourse, and first sexual identity disclosure (Hypotheses 2 and 3), as well as processes associated with self-medication and impaired functioning during adulthood (Hypotheses 4 and 5, respectively).

In support of Hypothesis 1, having parents with drinking problems was independently associated with earlier age at drinking onset. This finding is consistent with findings from both general population (Dube et al., 2006) and sexual-minority (McCabe et al., 2013) literature. This may reflect social modeling of adult behavior (Latendresse et al., 2008) and/or familial/genetic vulnerability (Cotton, 1979). Age at drinking onset, in turn, appears to mediate the association between parental drinking problems and first heterosexual intercourse, providing additional evidence of how adverse childhood experiences may contribute to earlier initiation of behaviors that place adolescents at risk for negative social and health outcomes.

Adverse childhood experiences were neither directly nor indirectly associated with age at first sexual orientation disclosure. Only respondents’ baseline age was associated with age at disclosure. Younger women in the sample tended to disclose earlier, which may reflect the growing visibility and social acceptance of sexual minorities.

Childhood sexual abuse was not associated with any age-at-onset measure. As in prior research with general population (Dube et al., 2005) and sexual-minority women (Hughes et al., 2007) samples, childhood sexual abuse did have a direct effect on depression. The processes believed to underlie this relationship include long-lasting trauma-induced increases in sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events (Kendler et al., 2004), impairment of intimate relationships by adverse psychological effects of childhood sexual abuse (e.g., anger, distrust, low self-esteem, sexual problems) with resulting social isolation and depression (Covington and Surrey, 1997), and pervasive neurodevelopmental effects of chronic sexual abuse, resulting in multiple adverse mental health outcomes, including depression (van der Kolk et al., 1996).

Earlier ages at drinking onset and first sex were associated with hazardous drinking, a finding supporting Hypothesis 2 and consistent with existing research (Mason et al., 2010). Earlier age at drinking onset is believed to increase risk of developing problematic drinking by increasing the period of drinking during adolescence and young adulthood when individuals are most vulnerable (Dube et al., 2006). Our findings suggest that age at drinking onset has a direct effect on hazardous drinking, as well as an indirect effect via increasing the likelihood of early sex (Fergusson and Lynskey, 1996). These developmental milestones, however, were not found to be predictive of baseline depression.

Hypothesis 3 posited that age-at-onset developmental markers would be associated with anxiety, such that sexual-minority women who reported higher levels of anxiety would also report later ages for these developmental milestones. This hypothesis was partially supported, as sexual-minority women who reported greater anxiety levels were older at first consensual heterosexual intercourse and sexual identity disclosure.

It is not surprising that anxiety was associated with delays both in initiating heterosexual relationships and in disclosing minority sexual identity. Studies have found that family and other social pressures to enter into heterosexual relationships, to marry, and to have children are major stressors for many sexual-minority women (Greene, 1994; Morris et al., 2002). Attempting to balance adherence to heterosexual societal norms and a minority sexual identity by delaying or avoiding heterosexual sexual relationships and delaying sexual identity disclosure may be both a cause and a consequence of anxiety symptoms (Jordan and Deluty, 1998). Unfortunately, our data cannot resolve the temporal/causal ordering between anxiety and these developmental milestones. Examining these relationships should be a goal of future inquiry.

Wave 1 anxiety level was positively associated with Wave 2 level of hazardous drinking, a finding supportive of the self-medication model (Hypothesis 4). However, Wave 1 depression was not associated with Wave 2 hazardous drinking. This finding is consistent with results from a national study of young (ages 18–25 years) sexual-minority women (Kaysen et al., 2012) but inconsistent with studies of the women in the general population, which have documented a prospective association between depression and subsequent drinking behavior (McCarty et al., 2009; Moscato et al., 1997; Schutte, et al., 1997; Wang and Patten, 2001). It is notable, however, that these studies did not control for the effects of anxiety.

We also found only partial support for the impaired-functioning model (Hypothesis 5) in that Wave 1 hazardous drinking was associated with Wave 2 depression but not Wave 2 anxiety levels. These findings are consistent with prior research suggesting that hazardous drinking is prospectively more strongly associated with depression than anxiety (Jané-Llopis and Matytsina, 2006). Overall, our results suggest that self-medication via hazardous drinking may be a strategy for coping with anxiety among sexual-minority women and that depression is the more common consequence of this strategy.

Our findings also suggest that heightened risk of hazardous drinking can be explained, at least in part, by sexual-minority women’s attempts to cope with anxiety resulting from social stress, stigma, rejection, and discrimination associated with minority sexual identity and the social pressures of navigating heterocentric social environments. The finding that hazardous drinking was not prospectively associated with anxiety suggests that efforts to self-medicate symptoms of anxiety may be, in part, successful. The prospective relationship between hazardous drinking and subsequent depression does, however, provide evidence that conforms to an impaired-functioning model. It seems reasonable that any of the health, social, and economic costs of hazardous drinking may increase risk of depression.

Limitations and strengths

It is important to note that more than one possible model can be estimated in covariance structure modeling. Thus, there is no guarantee that the model presented reflects the most appropriate representation of these data. However, the model is rooted in theory and provides a scientifically plausible depiction of the social behavioral processes in the development of hazardous drinking in this high-risk population.

The study sample was recruited using nonprobability methods. The sampling strategy, however, was carefully designed and executed to ensure recruitment of a diverse sample of this difficult-to-find population, an approach deemed necessary given the prohibitive costs of using probability sampling to recruit sexual-minority participants. In addition, although we have demonstrated theoretically derived, temporal associations among several variables, we cannot establish causality using these data. Indeed, the complexity of the processes examined and the range of other potential social, psychological, and health-related mediators or moderators preclude the possibility of definitively identifying causal mechanisms. The time frames used to measure hazardous drinking, anxiety, and depression were not fully consistent with one another in the two waves of data collection. There may have also been unmeasured events between Waves 1 and 2. Additional concerns related to measurement quality include reliance on retrospective self-reports, a strategy known to be associated with measurement error; reliance on subjective indicators of childhood sexual abuse; and use of depression and anxiety measures that do not reflect strict criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Although these limitations are important to consider, we also emphasize strengths of the study. Most notable is the study design. Our analyses used one of the few currently available longitudinal data sets related to sexual-minority women’s health. The data were collected using rigorous survey procedures that included high-quality face-to-face interviews and careful follow-up procedures that successfully minimized attrition across waves. This study goes beyond the previous modest research literature that has focused on descriptive reporting of prevalence by investigating an integrated set of research hypotheses designed to elucidate the social and behavioral processes associated with the alcohol use and mental health of adult sexual-minority women.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Kelly Martin and Robyn Nisi in the preparation of this manuscript. We also thank the women who served as participants in the Chicago Health and Life Experiences Study.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants K01 AA00266 and R01 AA13328. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Abraham HD, Fava M. Order of onset of substance abuse and depression in a sample of depressed outpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1999;40:44–50. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Lehavot K, Beadnell B, Circo E. Childhood abuse and mental health indicators among ethnically diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:459–468. doi: 10.1037/a0018661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Hack T. Preventing sexual risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents: The benefits of gay-sensitive HIV instruction in schools. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:940–946. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, McCabe SE. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, Small JW, Schlauch RC, Lewinsohn PM. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calahan D. Problem drinkers: A national study. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L, Stoolmiller M. Predicting the timing of first sexual intercourse for at-risk adolescent males. Child Development. 1996;67:344–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ATA, Gau SF, Chen THH, Chang JC, Chang YT. A 4-year longitudinal study on risk factors for alcoholism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:184–191. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Burden of psychiatric morbidity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the California Quality of Life Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:647–658. doi: 10.1037/a0016501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: Moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:139–152. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin SB. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: Findings from the Growing Up Today Study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton NS. The familial incidence of alcoholism: A review. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1979;40:89–116. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1979.40.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington SS, Surrey JL. The relational model of women’s psychological development: Implications for substance abuse. In: Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, editors. Gender and alcohol: Individual and social perspectives (pp, 335–351) New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Pratt LA. Risk of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in social phobia: A prospective analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1693–1700. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Factors associated with parents’ knowledge of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths’ sexual orientation. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2010;6:178–198. [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Midanik LT, Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: Results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH. Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28:430–438. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. 444.e1–444.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. London, England: Hodder & Stoughton; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:260–266. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. Alcohol misuse and adolescent sexual behaviors and risk taking. Pediatrics. 1996;98:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Mason WA, Mazza JJ, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Latent growth modeling of the relationship between depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:186–197. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abraham HD. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Association between anxiety disorders and substance use disorders among young persons: Results of a 21-year longitudinal study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2004;38:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Massak A, Demers A, Rehm J. Does the association between alcohol consumption and depression depend on how they are measured? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:78–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: Results of a national survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene B. Lesbian women of color: Triple jeopardy. In: Comas-Diaz L, Green B, editors. Women of color: Integrating ethnic and gender identities in psychotherapy (pp. 389–427) New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hayduk LA. Structural equation modeling with LISREL: Essentials and advances. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: A retrospective cohort study. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: A ten-year model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:190–198. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Wilsnack SC, Szalacha LA. Childhood risk factors for alcohol abuse and psychological distress among adult lesbians. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:769–789. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010a;105:2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, Szalacha LA, McNair R. Substance abuse and mental health disparities: Comparisons across sexual identity groups in a national sample of young Australian women. Social Science & Medicine. 2010b;71:824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jané-Llopis E, Matytsina I. Mental health and alcohol, drugs and tobacco: A review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:515–536. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM, Deluty RH. Coming out for lesbian women: Its relation to anxiety, positive affectivity, self-esteem, and social support. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;35:41–63. doi: 10.1300/J082v35n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, Costello EJ. The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2001;30:316–326. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Balsam K, Kirk J, Hughes T, Hodge K, Rhew I. H. L. Littleton (Chair), Understanding sexual violence and exploitation risk among diverse groups of victims. Los Angeles, CA: Symposium conducted at the 28th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; 2012, November. Risk factors associated with sexual assault among sexual minority women. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1475–1482. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400265x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471–244X/8/70/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo PH, Gardner CO, Kendler KS, Prescott CA. The temporal relationship of the onsets of alcohol dependence and major depression: Using a genetically informative study design. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1153–1162. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Erickson DJ. Prospective analysis of the relation between DSM-III anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:723–732. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parenting mechanisms in links between parents’ and adolescents’ alcohol use behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke TF, Newcomb MD. Alcohol involvement and dysphoria: A longitudinal examination of gender differences from late adolescence to adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR. Longitudinal associations between alcohol problems and depressive symptoms: Early adolescence through early adulthood. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Hitch JE, Kosterman R, McCarty CA, Herrenkohl TI, Hawkins JD. Growth in adolescent delinquency and alcohol use in relation to young adult crime, alcohol use disorders, and risky sex: A comparison of youth from low- versus middle-income backgrounds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1377–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1946–1952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Hughes TL, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation and substance abuse treatment utilization in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;44:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Kosterman R, Mason WA, McCauley E, Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl TI, Lengua LJ. Longitudinal associations among depression, obesity and alcohol use disorders in young adulthood. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Stevens D, Fenton B. Comorbidity of alcoholism and anxiety disorder: The role of family studies. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1996;20:100–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Balsam KF, Rothblum ED. Lesbian and bisexual mothers and nonmothers: Demographics and the coming-out process. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:144–156. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscato BS, Russell M, Zielezny M, Bromet E, Egri G, Mudar P, Marshall JR. Gender differences in the relation between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems: A longitudinal perspective. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;146:966–974. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Vargas-Carmona J, Galaif ER. Drug problems and psychological distress among a community sample of adults: Predictors, consequences, or confound? Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:405–429. [Google Scholar]

- Parks CA, Hughes TL. Age differences in lesbian identity development and drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:361–380. doi: 10.1080/10826080601142097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce RS, Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML, Mudar P. A longitudinal model of social contact, social support, depression, and alcohol use. Health Psychology. 2000;19:28–38. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen T, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: A follow-up study from age 8–42 for females and males. Addiction. 2005;100:652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich JM, Orvis BR. Alcohol problems: Patterns and prevalence in the U.S. Air Force. Santa Monica, CA: Rand; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Daley SE, Hammen C. Relationship between depression and substance use disorders in adolescent women during the transition to adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:215–222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Rae DS, Narrow WE, Kaelber CT, Schatzberg AF. Prevalence of anxiety disorders and their comorbidity with mood and addictive disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;173(Supplement 34):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto PB, Zimmerman MA, Caldwell CH. A longitudinal study of the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use in a sample of inner-city black youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:169–178. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Kahler CW, Seeley JR, Brown RA. Natural course of alcohol use disorders from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;23:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Bearinger LH, Blum RW, Resnick MD. Sexual intercourse, abuse and pregnancy among adolescent women: Does sexual orientation make a difference? Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31:127–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satcher DS. Executive summary: A report of the Surgeon General on mental health. Public Health Reports. 2000;115:89–101. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Keough ME. Anxiety sensitivity as a prospective predictor of alcohol use disorders. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:202–219. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte KK, Hearst J, Moos RH. Gender differences in the relations between depressive symptoms and drinking behavior among problem drinkers: A three-wave study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:392–404. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solarz AL, editor. Lesbian health: Current assessment and directions for the future. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Burton EM, Shaw H. Prospective relations between bulimic pathology, depression, and substance abuse: Unpacking comorbidity in adolescent girls. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:62–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020. Lesbian, gay: bisexual, and transgender health; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicId=25. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk BA, McFarlane AC, Weisaeth L, editors. Traumatic stress: The effects of overwhelming experience on the mind, body and society. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Patten SB. A prospective study of sex-specific effects of major depression on alcohol consumption. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;46:422–425. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss BJ, Hope DA. A preliminary investigation of worry content in sexual minorities. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Kristjanson AF, Wilsnack SC, Crosby RD. Are US women drinking less (or more)? Historical and aging trends, 1981–2001. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:341–348. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Hughes TL, Johnson TP, Bostwick WB, Szalacha LA, Benson P, Kinnison KE. Drinking and drinking-related problems among heterosexual and sexual minority women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:129–139. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Klassen AD, Schur BE, Wilsnack RW. Predicting onset and chronicity of women’s problem drinking: A five-year longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:305–318. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Vogeltanz ND, Klassen AD, Harris TR. Childhood sexual abuse and women’s substance abuse: National survey findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:264–271. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Wilsnack RW, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Harris TR. Child sexual abuse and alcohol use among women: Setting the stage for risky sexual behavior. In: Koenig L, Doll LS, O’Leary A, Pequegnat W, editors. From child sexual abuse to adult sexual risk: Trauma, revictimization, and intervention (pp. 181–200) Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Miller BA. Problem drinking and depression among DWI offenders: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:166–174. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and white-American women in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1985;9:507–519. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Helfand M. Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: Developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Developmental Review. 2008;28:153–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Wittchen HU, Höfler M, Pfister H, Kessler RC, Lieb R. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders: A 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:1211–1222. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]