Abstract

Objective:

Cigarette smokers have higher levels of alcohol consumption than nonsmokers and poorer response to alcohol treatment. It is possible that the greater severity of alcohol problems observed in smokers reflects a greater susceptibility to alcohol-related reinforcement. The present study used a behavioral economic purchase task to investigate whether heavy drinking smokers would have greater demand for alcohol than heavy drinking nonsmokers.

Method:

Participants were 207 college students who reported at least one heavy drinking episode in the past month. Of the 207 participants, 33.2% (n = 67) reported smoking cigarettes at least 1 day in the past month. Participants completed the hypothetical alcohol purchase task, a simulation task that asked them to report how many drinks they would purchase at varying price increments.

Results:

After the participants’ reported alcohol consumption, gender, alcohol problems, and depression were controlled for, analyses of covariance revealed that heavy drinking smokers had significantly greater reported maximum alcohol expenditures (Omax), greater maximum inelastic price (Pmax), and higher breakpoint values (first price suppressing consumption to zero).

Conclusions:

College student heavy drinkers who also smoke cigarettes exhibit increased demand for alcohol. Smokers in this high-risk developmental stage may thus be less sensitive to price and other contingencies that would otherwise serve to modulate drinking and may require more intensive intervention approaches.

College students disproportionately engage in risky health behaviors such as alcohol and tobacco consumption (Fromme et al., 2008; White et al., 2006). Approximately 45% of college students engage in heavy episodic drinking (Dawson et al., 2004; O’Malley and Johnston, 2002; Wechsler et al., 2002), and 16.6% report having used tobacco within the past 30 days (American College Health Association, 2009). Furthermore, among college students who are heavy drinkers, approximately 44% are current smokers, and more than 98% of college smokers consume alcohol (Weitzman and Chen, 2005). Cigarette smokers report higher levels of alcohol consumption than nonsmokers (Anthony and Echeagaray-Wagner, 2000; Chiolero et al., 2006; Kahler et al., 2008). Similarly, college students are more likely to consume alcohol when they smoke and drink to higher levels (Midanik et al., 2007).

Concurrent alcohol and tobacco users also are at increased risk for health-related difficulties such as cancer and cardiovascular disease (Pelucchi et al., 2008; Schlecht et al., 1999), specifically cancers of the mouth and throat (Franceschi et al., 1990; Negri et al., 1993; Zheng et al., 1990, 2004), esophagus (Howe et al., 2001), and potentially the liver (Marrero et al., 2005). In addition, concurrent users are more prone to experiencing academic difficulties (Barnes and Welte, 1986; DeBerard et al., 2004) and to using illicit drugs compared with individuals who use either substance alone or not at all (Hoffman et al., 2001). In addition to the physical and social consequences of concurrent use, smokers demonstrate poorer response to alcohol treatment. Specifically, smokers are more likely to relapse following successful alcohol treatment compared with individuals who have stopped or decreased smoking (Friend and Pagano, 2005; Karam-Hage et al., 2005) and compared with nonsmokers (Hintz et al., 2007).

It is possible that smokers have a greater general susceptibility to drug-related reinforcement, as indicated by animal studies in which nicotine administrations can increase responding for alcohol (Clark et al., 2001). Alternatively, because individuals typically smoke and drink simultaneously (Dierker et al., 2006), smokers may find alcohol more reinforcing because of the enhancing quality of combining the two substances (Piasecki et al., 2011). This is consistent with evidence that alcohol and nicotine additively increase dopamine release in the corticomesolimbic dopamine pathway (Tizabi et al., 2002, 2007). Similarly, ecological momentary assessment studies have found that individuals report an increase in pleasure from their last drink after smoking a cigarette (Piasecki et al., 2011). Although the results of these studies suggest that smoking is associated with acute increases in alcohol-related reinforcement, research is needed to determine whether smokers have a more general tendency to overvalue other drugs of abuse.

Alcohol and other drug purchase tasks have been developed to generate demand curves that can measure several aspects of the incentive value or the behavior-maintaining aspects of drugs and alcohol (Bickel et al., 2000; Hursh and Silberberg, 2008; Johnson and Bickel, 2006), including maximum levels of consumption and expenditure and the relative price sensitivity of consumption. In laboratory settings, demand curve analyses have been used to quantify drug consumption and levels of drug-reinforced responding as a function of price (e.g., lever presses required to obtain a drug dose) to measure differences in drug potency or the impact of environmental manipulations on demand (Higgins et al., 2004; Johnson and Bickel, 2006). Recently, time and cost-efficient self-report demand curve measures have been developed and administered in clinical settings to measure individual differences in the incentive value of drugs (Jacobs and Bickel, 1999; MacKillop et al., 2010b; Murphy et al., 2009; Skidmore and Murphy, 2011).

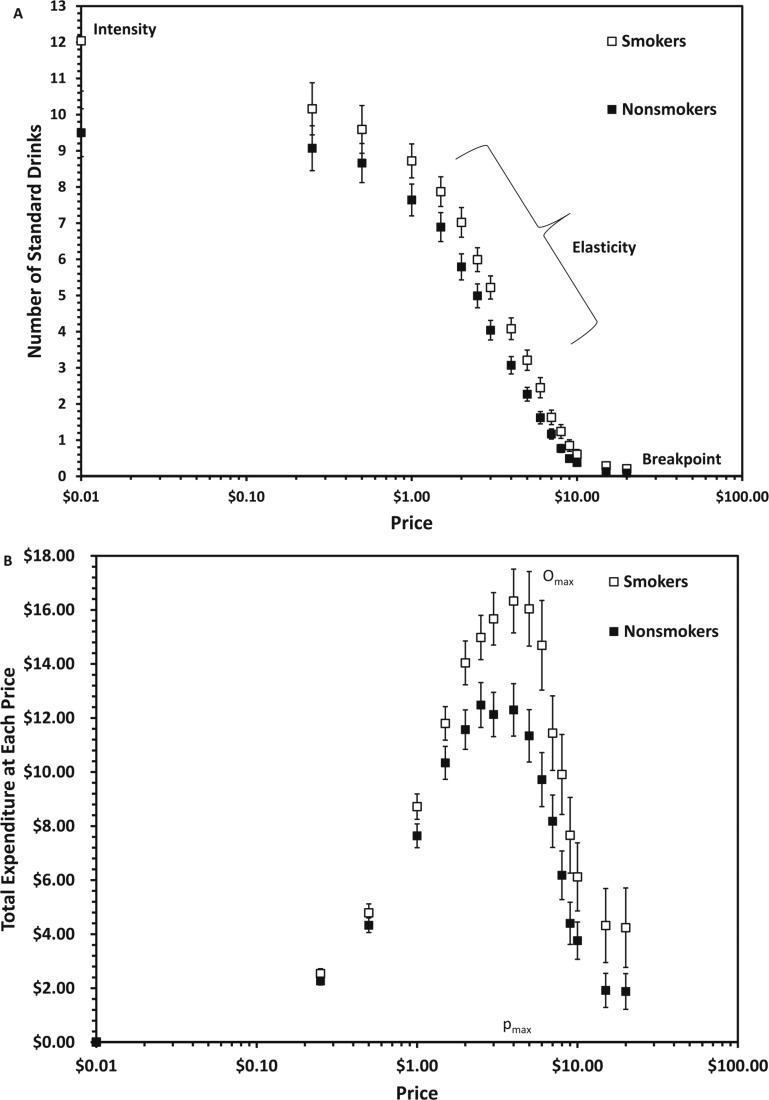

These studies have used hypothetical choices regarding alcohol and other drug purchases at varying prices (demand curves) to generate behavioral economic indices of drug-related reinforcement. In the case of alcohol purchase tasks (APTs), participants are asked how many standard drinks they would purchase and consume across a range of drinking prices (e.g., $0 to $20.00 per drink). (All amounts are in U.S. dollars.) Participants provide consumption values and, implicitly, expenditures at each price. Demand indices are then computed from these consumption and expenditure values. These indices include demand intensity (i.e., peak consumption at lowest price), elasticity (i.e., the rate of consumption reduction as a function of price), Pmax (i.e., maximum inelastic price), Omax (i.e., greatest expenditure on alcohol), and breakpoint (i.e., the first price that completely suppresses consumption).

Although demand almost always decreases in response to price increases, there are individual differences in the value of these parameters, which are thought to reflect strength of motivation for alcohol. For example, demand curves are associated with reported levels of heavy or heavy episodic drinking (Murphy and MacKillop, 2006) and alcohol-related problems, even after typical weekly consumption level is controlled for (MacKillop et al., 2010b; Murphy et al., 2009). Individuals who report symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress disorder (Murphy et al., 2013), craving (MacKillop et al., 2010b), or elevated personality risk (Acker et al., 2012; Kiselica and Borders, 2013; Skidmore and Murphy, 2011; Smith et al., 2010) also report elevated demand, and the influence of demand on alcohol problems has been found to be mediated by the relative level of stress-related drinking (Yurasek et al., 2011). Demand parameters show good test–retest reliability (Murphy et al., 2009) and associations with actual alcohol consumption in laboratory settings (Amlung et al., 2012).

Individual differences in alcohol demand curve measures also have been associated with changes in drinking following a brief alcohol intervention. College student drinkers with higher maximum expenditure (i.e., Omax) for alcohol and lower price sensitivity at baseline reported greater drinking 6 months after an intervention in models that controlled for baseline drinking (MacKillop and Murphy, 2007). Thus, elevated demand for alcohol may be indicative of a more problematic and less malleable drinking pattern, even among individuals with relatively similar heavy drinking patterns.

Given the robust association between smoking status and alcohol problem severity (Friend and Pagano, 2005), and given that smoking increases (acute) reports of pleasure (Piasecki et al., 2011) and dopamine release (Tizabi et al., 2002; 2007) associated with drinking, smokers may exhibit a general trait-level tendency to overvalue alcohol-related rewards, as reflected in elevated demand. However, this hypothesis has not been directly tested. Therefore, the present study attempted to extend research into (a) the determinants of elevated alcohol demand and (b) the associations between smoking and problematic alcohol use by determining whether heavy drinking smokers report elevated alcohol demand compared with heavy drinking nonsmokers after a variety of covariates (e.g., gender, drinking level, alcohol problems, depression) were controlled for. It was hypothesized that undergraduate heavy drinkers who also smoke would report greater demand for alcohol (as indicated by greater demand intensity) and Omax. Similarly, we hypothesized that smokers would be less sensitive to increases in price (as indicated by lower elasticity scores). These three metrics have shown the most consistent associations with alcohol-related outcomes (Acker et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2009).

Method

Participants

Participants were 207 college students (47% male; 68.5% White, 27.4% African American; Mage = 19.5 years [SD = 5.04]) who reported at least one heavy drinking episode (five/four or more drinks in one occasion for a man/woman) in the past month and agreed to participate in one of two brief alcohol intervention trials (Murphy et al., 2010). Participants in Study 1 were recruited from the on-campus health center, and those in Study 2 were recruited through a required first-year course. All procedures were approved by the University of Memphis Institutional Review Board. In the present analysis, baseline data were pooled from all conditions across the two trials. Of the 207 participants, 33.2% (n = 67) reported having smoked cigarettes at least 1 day in the past month.

Measures

Alcohol consumption.

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985) was used to measure alcohol consumption. On the DDQ, individuals provide an estimate of the total number of standard drinks they consumed on each day during a typical week in the past month. The DDQ has been used frequently with college students and is a reliable measure that is highly correlated with self-monitored drinking reports (Kivlahan et al., 1990). Participants also reported the number of times in the past month that they had a heavy drinking episode (four/five drinks in a single occasion for women/men).

Alcohol-related problems.

The Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire was used to measure alcohol-related problems experienced within the past 6 months (Read et al., 2006). Participants were asked to indicate which of 49 possible alcohol-related consequences (e.g., “I have woken up in an unexpected place after heavy drinking”) they have experienced. This measure has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including internal consistency and predictive validity (Read et al., 2007). Internal consistency was .92 in this sample.

Smoking variables.

To assess smoking status and nicotine dependence, participants completed the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Prokhorov et al., 1996). This measure consists of seven items, with the first measuring smoking status (e.g., “On how many days in the past month did you smoke at least one cigarette?”) and the rest assessing nicotine dependence (e.g., “Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden?”). Scores range from 0 to 8, with higher scores indicating more nicotine dependence. Internal consistency for the FTND was .59 in this sample.

Depression.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants are given 20 statements (e.g., “I had crying spells”) and rate how often in the past week they have felt that way, ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]) to 3 (most or all of the time [5–7 days]). Four of the items are reverse scored (e.g., “I was happy”). The CES-D has been shown to be reliable for assessing depressive symptoms across racial, gender, and age categories (Knight et al., 1997). Internal consistency for the CES-D in this sample was .84.

Alcohol demand.

An APT was used to measure alcohol demand. On the APT, participants are presented with a hypothetical drinking scenario and are asked how many drinks they would purchase and consume at 17 ascending prices in the hypothetical situation (Murphy and MacKillop, 2006). The APT included the following instructions:

In the questionnaire that follows, we would like you to pretend to purchase and consume alcohol. Imagine that you and your friends are at a party on a Thursday night from 9:00 p.m. until 2:00 a.m. to see a band. Imagine that you do not have any obligations the next day (i.e., no work or classes). The following questions ask how many drinks you would purchase at various prices. The available drinks are standard-size domestic beers (12 oz.), wine (5 oz.), shots of distilled spirits (1.5 oz.), or mixed drinks containing one shot of distilled spirits. Assume that you did not drink alcohol or use other drugs before you went to the party and that you will not drink or use other drugs after leaving the party. Also, assume that the alcohol you are about to purchase is for your consumption only during the party (you can’t sell or bring drinks home). Please respond to these questions honestly, as if you were actually in this situation.

Participants were then asked to report how many drinks they would consume at each of 17 prices, ranging from $0 (free) to $3.00 increasing by 50-cent increments, $3.00–$10.00 increasing by $1.00 increments, and $10.00–$20.00 increasing by $5.00 increments. Reported consumption was plotted as a function of price, and expenditures at each price were computed by multiplying consumption by price for each amount.

The resulting demand and expenditure curves yielded five indices of the incentive value of alcohol used in this study: demand intensity, breakpoint, Omax, Pmax, and elasticity. The first four indices were directly observed from the raw consumption and expenditure data (Murphy et al., 2009); elasticity is the average slope of the Hursh and Silberberg (2008) exponential equation: log Q = 1og Q0 + k (e−αP − 1), where Q = consumption at a given price, Q0 = consumption intercept, k = a constant denoting the range of consumption values in log10 units, P = price, and α = the derived demand parameter reflecting the rate of decline of consumption in standardized price. Greater elasticity (α) values reflect a greater proportional decrease in consumption as a function of price. The APT demand metrics have demonstrated good test-retest reliability and construct validity (MacKillop et al., 2010a; Murphy et al., 2009).

Data analysis plan

To minimize the impact of outliers, values greater than 3.29 SD above the mean on a given variable were changed to one unit greater than the greatest nonoutlier value (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Additionally, variables that were skewed or kurtotic were transformed using square root transformations. Correlational analyses were used to analyze the associations between smoking status, alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol demand. We also included depression as an individual-difference variable that might contribute to elevated demand and smoking (i.e., Murphy et al., 2013). Separate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were run to examine whether individual differences in alcohol demand are related to smoking status after controlling for relevant covariates (typical weekly alcohol consumption, gender, alcohol problems, and depression).

Results

Descriptive statistics and adequacy of demand curve model fit

On average, participants reported consuming 16.07 alcoholic drinks per week (SD = 13.48), experiencing 5.77 (SD = 5.04) heavy episodic drinking episodes in the past 2 weeks, and having 12.63 (SD = 8.51) alcohol-related problems. Smokers (n = 67) reported smoking a mean of 7.72 (SD = 5.87) cigarettes a day and a relatively low FTND mean score of 1.96 (SD = 1.80). On the APT, mean consumption at no cost (intensity) was 10.01 drinks (SD = 6.55), the mean lowest price at which participants reported that they would stop consuming drinks (breakpoint) was $9.29 (SD = 5.25), the mean maximum expenditure (Omax) was $18.36 (SD = 11.40), and the mean price per drink at this expenditure (Pmax) was $3.95 (SD = 2.32). The mean rate of consumption reduction as a function of price (elasticity) was 0.05 (SD = 0.05). See Table 1 for descriptive data as a function of smoking status.

Table 1.

Mean scores on alcohol- and smoking-related variables and demand curve indices for smokers and nonsmokersa

| Smoking status |

||

| Variable | Smoker (n = 67) M(SD) | Nonsmoker (n = 140) M(SD) |

| No. of drinks per week | 18.46 (12.72)* | 14.83 (13.33) |

| Alcohol-related problemsb | 15.27 (8.67)*** | 11.30 (1.30) |

| Nicotine dependencec | 1.96 (1.82) | – |

| No. of cigarettes per day | 7.72 (5.87) | – |

| Depressiond | 14.93 (8.95)** | 11.95 (6.79) |

| Intensitye | 10.90 (6.46)* | 9.22 (6.18) |

| Breakpointf | 10.58 (5.36)** | 8.63 (5.02) |

| Omaxg | 21.75 (11.51)*** | 16.63 (11.17) |

| Pmaxh | 4.43 (2.42)* | 3.70 (2.17) |

| Elasticityi | 0.04 (0.04)** | 0.06 (0.05) |

Because income has been found to be associated with alcohol demand, we examined the reported disposable income for nonessential items (e.g., clothing, compact discs, entertainment, alcohol, other drugs) between smokers and nonsmokers; there were no differences between these two groups (p = .69).

The Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire was used to measure alcohol-related problems experienced within the past 6 months. Participants were asked to indicate which of 49 possible alcohol-related problems they have experienced. In this sample, scores ranged from 0 to 38, with higher scores indicative of more problems experienced.

To assess nicotine dependence, participants completed the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence. This measure consists of seven items, with scores ranging from 0 to 8. Higher scores indicating more nicotine dependence.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. Participants are given 20 statements and rate how often in the past week they have felt that way, ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time [<1 day]) to 3 (most or all of the time [5–7 days]). Four of the items are reverse scored. Higher scores indicate higher depression.

Intensity is the peak consumption at lowest price. In this sample, scores ranged from 0 to 34, with higher scores indicating greater intensity.

Breakpoint (i.e., the first price that completely suppresses consumption) ranged from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating higher prices.

Omax = maximum alcohol expenditures. Scores ranged from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater expenditure.

Pmax = maximum inelastic price. Scores ranged from 0.25 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater prices.

Elasticity (i.e., the rate of consumption reduction as a function of price) ranged from 0 to 0.30, with higher scores indicating greater sensitivity to increases in price.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001.

As previously described, elasticity estimates were generated with an exponential demand curve equation (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008). This equation provided an excellent fit (R2 = .98) for the aggregated data (i.e., sample mean consumption values) but only an adequate fit to individual participant data (mean R2 = .60). Although R2 may not function well as a measure of curve fit with nonlinear models (Johnson and Bickel, 2008), the authors used a similar criterion as Reynolds and Schiffbauer (2004) and included elasticity values for analyses only when the demand equation accounted for at least 30% of the variance in the participant’s consumption (47 participants were excluded from the elasticity analyses, but not from the other analyses, for this reason). There were no significant demographic differences between participants with and without valid elasticity values, but participants without valid values reported lower weekly drinking levels, t(205) = −2.45, p = .02. Poor curve fits were often the result of having very few nonzero consumption values on the APT.

Associations between alcohol use, smoking variables, and alcohol demand

Pearson’s r statistics were used to analyze bivariate associations between alcohol consumption (drinks per week), alcohol-related problems, smoking status, nicotine dependence, depression, and the alcohol demand curve metrics (Table 2). As predicted, the demand metrics were highly correlated with the drinking variables (alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems); intensity, Omax, and elasticity were significantly associated with alcohol consumption. Similarly, all demand metrics except Pmax were associated with alcohol-related problems. Smoking status was significantly related to alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and all five demand indices (Table 2). Nicotine dependence was associated with greater intensity and Omax values. Depression was not related to alcohol consumption but was significantly associated with alcohol-related problems, elasticity, and smoking status.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations among alcohol consumption (drinks per week), smoking status, nicotine dependence, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol demand (intensity, breakpoint, Omax, Pmax, and elasticity)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

| 1. Drinks per week | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. Alcohol-related problems | .511** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. Smoking status | .165* | .224** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. Nicotine dependence | .137 | .193 | −.200 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. Depression | −.061 | .194** | .183** | .183 | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. Intensity | .585** | .348** | .153* | .238* | .108 | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. Breakpoint | .097 | .161* | .188** | .128 | .081 | .208** | 1.00 | |||

| 8. Omax | .516** | .442** | .234** | .235* | .061 | .589** | .653** | 1.00 | ||

| 9. Pmax | −.058 | .134 | .165* | .047 | .092 | −.067 | .653** | .531** | 1.00 | |

| 10. Elasticity | −.289** | −.446** | −.197* | −.226 | −194* | −.357** | −.486** | −.561** | −.344** | 1.00 |

Notes: Omax = maximum alcohol expenditures; Pmax = maximum inelastic price.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Differences in demand based on smoking status

ANCOVAs were run to investigate the relationship between smoking status and alcohol

demand while controlling for gender, typical weekly drinking level, alcohol-related

problems, and depression (Table 3). Analyses

indicated that smokers had higher scores on Omax, F(1,

193) = 3.76, p = .05,  = .02; higher breakpoint values, F(1,

193) = 4.96, p = .03,

= .02; higher breakpoint values, F(1,

193) = 4.96, p = .03,  = .03; and greater maximum inelastic price

(Pmax), F(1, 191) = 4.46, p

= .04,

= .03; and greater maximum inelastic price

(Pmax), F(1, 191) = 4.46, p

= .04,  = .02; compared with nonsmokers. These results suggest

that undergraduate heavy drinkers who also smoke cigarettes have increased demand for

alcohol, in particular greater alcohol expenditures and less price sensitivity, even

after other risk factors are taken into account (Figure

1). Because research has demonstrated that smokers who smoke fewer than

five cigarettes a day (i.e., “chippers”; Shiffman and Paty, 2006) show fewer signs of nicotine dependence

compared with heavier smokers (seven or more cigarettes per day), we replicated the

previous analyses, removing chippers from the smoking group. These results were

similar to the primary smoker versus non-smokers comparison: Participants who smoke

seven or more cigarettes per day had higher Omax (p

= .03) and breakpoint (p = .05) values than

nonsmokers, but Pmax was no longer significant (p

= .27).

= .02; compared with nonsmokers. These results suggest

that undergraduate heavy drinkers who also smoke cigarettes have increased demand for

alcohol, in particular greater alcohol expenditures and less price sensitivity, even

after other risk factors are taken into account (Figure

1). Because research has demonstrated that smokers who smoke fewer than

five cigarettes a day (i.e., “chippers”; Shiffman and Paty, 2006) show fewer signs of nicotine dependence

compared with heavier smokers (seven or more cigarettes per day), we replicated the

previous analyses, removing chippers from the smoking group. These results were

similar to the primary smoker versus non-smokers comparison: Participants who smoke

seven or more cigarettes per day had higher Omax (p

= .03) and breakpoint (p = .05) values than

nonsmokers, but Pmax was no longer significant (p

= .27).

Table 3.

Estimated marginal mean scores from ANCOVAs examining alcohol demand for smokers and nonsmokers (controlling for gender, alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and depression)

| Smoking status |

||||

| Demand curve metric | Smoker | Non-smoker | F(df) |  |

| Intensity | 3.03 | 2.99 | 0.116 (192) | .001 |

| Breakpoint | 3.12 | 2.83 | 4.96 (193)* | .025 |

| Omax | 4.30 | 3.96 | 3.76 (193)* | .019 |

| Pmax | 2.04 | 1.85 | 4.46 (191)* | .023 |

| Elasticity | 0.04 | 0.06 | 2.07 (149) | .014 |

Notes: ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; Omax = maximum alcohol expenditures; Pmax = maximum inelastic price.

p ≤ .05.

Figure 1.

Panel A depicts the mean (±1 standard error of the mean; SEM) number of drinks (hypothetical) that student smokers (n = 67) and nonsmokers (n = 140) would purchase as a function of price plotted in conventional double logarithmic coordinates for proportionality. Panel B depicts the mean (±1 SEM) expenditure on drinks (hypothetical) at each price by smokers and nonsmokers plotted in conventional double logarithmic coordinates for proportionality. The individual demand metrics also are provided: demand intensity (i.e., the peak consumption at the lowest price), elasticity (i.e., the rate of consumption reduction as a function of price), Pmax (i.e., the maximum inelastic price), Omax (i.e., the greatest expenditure on alcohol), and the breakpoint (i.e., the first price that completely suppresses consumption).

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that cigarette smokers have higher levels of alcohol consumption and poorer response to alcohol-focused treatment compared with non-smokers. Approximately 44% of heavy drinking college students also are smokers, placing them at risk for numerous health- and academic-related problems. Given the relationship between smoking status and alcohol-problem severity, smokers may tend to overvalue alcohol-related rewards. The goal of this study was to investigate whether cigarette smoking among heavy drinkers was associated with greater demand for alcohol on a behavioral economic purchase task. Consistent with our hypothesis, heavy drinking students who also reported having smoked at least 1 day in the past month demonstrated greater alcohol expenditures, breakpoint values, and maximum inelastic price values. The association between smoking and elevated demand appears to be unique and remained significant even after taking into account weekly drinking, alcohol problems, gender, and depression. In addition, the pattern of bivariate correlations indicated that student drinkers who smoke and report nicotine dependence report elevated alcohol demand.

Surprisingly, despite significant bivariate correlations between demand intensity and smoking, the effect of smoking on intensity was not significant in the multivariate ANCOVA that included weekly drinking among other covariates. This finding may be related to the moderate to large magnitude correlation between intensity and weekly drinking (r = .58), but it also may suggest that the shared risk factors that influence smoking status and alcohol demand are less relevant to episodes of ad libitum drinking captured by the intensity index as compared with the demand indices related to maximum output/expenditure or price sensitivity (MacKillop et al., 2008). Although smokers and nonsmokers did not differ on elasticity in the multivariate ANCOVA, smoking status was correlated with elasticity and the three demand indices that yielded significant ANCOVA results reflecting some element of price sensitivity (MacKillop et al., 2008). It is possible that smokers reported greater expenditure and breakpoint values in part because they are accustomed to making large expenditures on cigarettes. On average, a pack of cigarettes costs $5.51 (Rumberger and Hollenbeak, 2010), and more dependent smokers smoke more cigarettes, resulting in significant costs (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Therefore, smokers might be less price sensitive overall. Although in general, intensity, Omax, and elasticity have shown the most consistent associations with alcohol-related outcomes and may reflect the most essential elements of demand (Acker et al., 2012; Murphy et al., 2009), overall results have been variable, and the current results extend a few previous studies that indicated that breakpoint and Pmax may at times show significant associations with clinically relevant outcomes (MacKillop and Murphy, 2007). In general, these results support the continued inclusion of all five demand metrics in clinically relevant research.

Consistent with previous research (Pape et al., 2009), smoking status and nicotine dependence were correlated with alcohol-related problems. Findings from the current study extend that research by demonstrating that smokers also report greater demand for alcohol. Although more research is needed to determine the clinical implications of elevated demand (MacKillop and Murphy, 2007), laboratory and theoretical behavioral economic research suggests that elevated demand reflects stronger and more persistent motivation to consume the substance (Bickel and Vuchinich, 2000; Hursh and Silberberg, 2008; Johnson and Bickel, 2006). The present results extend previous research indicating that a variety of risk factors for problematic drinking—including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (Murphy et al., 2013), impulsivity (Kiselica and Borders, 2013; Smith et al., 2010), craving (MacKillop et al., 2010b), sensation seeking (Skidmore et al., 2009), and coping-related drinking (Yurasek et al., 2011)—are associated with elevated demand. This increased alcohol demand among smokers may contribute to a greater willingness to allocate excessive resources toward drinking (i.e., time, money, behavior) or to be less responsive to contingencies that typically reduce drinking (e.g., price or other elements of response cost; Skidmore and Murphy, 2010), which could contribute to the occurrence of more alcohol-related problems (e.g., blackouts, fights, injuries). Thus, the present results may help to explain the elevated risk for alcohol problems and the poor treatment response observed among drinkers who also smoke (Friend and Pagano, 2005; Karam-Hage et al., 2005).

These findings also are generally consistent with research conducted with nonhuman animals demonstrating that nicotine administration increases alcohol consumption, which may be the result of cross-tolerance (Collins et al., 1993) or enhanced reinforcement (Clark et al., 2001). Similarly, nicotine administration has been found to increase alcohol craving (Kouri et al, 2004) and vice versa (King and Epstein, 2005), which may contribute to the increased alcohol reward value found in smokers. In addition to craving, individuals in an ecological momentary assessment study reported increased satisfaction in alcohol consumption after smoking (Piasecki et al., 2011). Therefore, smokers may find alcohol more reinforcing because of the enhancing quality of combining the two substances (Piasecki et al., 2011). This study extends these findings by examining reinforcing efficacy outside the context of nicotine administration.

These findings may imply a more innate or dispositional characteristic of smokers. Research has demonstrated an overlap in genetic factors contributing to alcohol and nicotine dependence as well as vulnerability for dependence (True et al., 1999). Nicotine and alcohol share neurochemical mechanisms of action in the brain reward system, including a relationship with the dopamine system (Preuss et al., 2007). There is evidence that smokers may have a hypersensitive dopamine system and higher reward sensitivity, which might make alcohol more reinforcing for smokers (Hogarth, 2011).

The results of this study must be examined within the context of its limitations. The directionality of the relationship between our variables cannot be determined because of the cross-sectional nature of the study. Additionally, data collected on alcohol consumption, smoking status, alcohol-related consequences, and expenditures were assessed via self-report measures. There is considerable empirical support for the reliability, validity, and accuracy of hypothetical purchase measures (Amlung et al., 2012; Correia and Little, 2006; Murphy et al., 2009). However, given the increased use of technology in alcohol and other drug research methodology (Kuntsche and Robert, 2009; Neal et al., 2006), it would be interesting to investigate relationships between smoking and behavioral economics indices based on actual expenditures on alcohol over time (Tucker et al., 2006). It also might be useful to use a matched-sample design to more directly isolate the role of smoking status as an influence on alcohol demand. Finally, this study should be replicated in a general young-adult sample that includes non-college students with a range of drinking practices.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the findings from this study provide a conceptual and empirical bridge between the behavioral economic alcohol and tobacco literature, suggesting that smoking cigarettes may contribute to the overvaluation of alcohol in heavy drinking college students. Those initiating interventions targeting alcohol consumption also may want to inquire about smoking status, because smokers are more likely to relapse to alcohol use after treatment (Friend and Pagano, 2005; Karam-Hage et al., 2005). Smokers appear to be less sensitive to price and other contingencies that would otherwise serve to modulate drinking, and they may therefore require more intensive intervention approaches (Murphy et al., 2012). Future research is required to identify possible mediators of the relationship between smoking and alcohol demand, including social, affective, and personality variables.

Footnotes

This research was supported by an Alcohol Research Foundation (ABMRF) grant (to James G. Murphy) and National Institutes of Health Grant K23 AA016936 (to James MacKillop).

References

- Acker J, Amlung M, Stojek M, Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Individual variation in behavioral economic indices of the relative value of alcohol: Incremental validity in relation to impulsivity, craving, and intellectual functioning. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. 2012;3:423–436. [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association. American college health association—National college health assessment II: Reference group executive summary fall 2009. Linthicum, MD: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amlung MT, Acker J, Stojek MK, Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Is talk “cheap”? An initial investigation of the equivalence of alcohol purchase task performance for hypothetical and actual rewards. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Echeagaray-Wagner F. Epidemiologic analysis of alcohol and tobacco use. Alcohol Research & Health. 2000;24:201–208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Welte JW. Patterns and predictors of alcohol use among 7–12th grade students in New York State. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1986;47:53–61. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Vuchinich R. Reframing health behavior change with behavioral economics. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chiolero A, Wietlisbach V, Ruffieux C, Paccaud F, Cornuz J. Clustering of risk behaviors with cigarette consumption: A population-based survey. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AA, Lindgren SS, Brooks SP, Watson WP, Little HJ. Chronic infusion of nicotine can increase operant self-administration of alcohol. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:108–117. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. Women’s issues in alcohol use and cigarette smoking. In: Baer J, Marlatt G, McMahon R, editors. Addictive behaviors across the life span: Prevention, treatment, and policy issues (pp. 274–306) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia CJ, Little C. Use of a multiple-choice procedure with college student drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:445–452. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerard MS, Spielmans GI, Julka DL. Predictors of academic achievement and retention among college freshmen: A longitudinal study. College Student Journal. 2004;38:66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Lloyd-Richardson E, Stolar M, Flay B, Tiffany S, Collins L, Clayton R, the Tobacco Etiology Research Network (TERN) The proximal association between smoking and alcohol use among first year college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi S, Talamini R, Barra S, Barón AE, Negri E, Bidoli E, La Vecchia C. Smoking and drinking in relation to cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and esophagus in northern Italy. Cancer Research. 1990;50:6502–6507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend KB, Pagano ME. Smoking cessation and alcohol consumption in individuals in treatment for alcohol use disorders. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2005;24:61–75. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n02_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1497–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH. Principles of learning in the study and treatment of substance abuse. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD, editors. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of substance abuse treatment (3rd. ed., pp. 81–87) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hintz T, Mann K. Long-term behavior in treated alcoholism: Evidence for beneficial carry-over effects of abstinence from smoking on alcohol use and vice versa. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:3093–3100. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Barnes GM. Co-occurrence of alcohol and cigarette use among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth L. The role of impulsivity in the aetiology of drug dependence: Reward sensitivity versus automaticity. Psychopharmacology. 2011;215:567–580. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2172-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe HL, Wingo PA, Thun MJ, Ries LA, Rosenberg HM, Feigal EG, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer (1973 through 1998), featuring cancers with recent increasing trends. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93:824–842. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychological Review. 2008;115:186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, Bickel WK. Modeling drug consumption in the clinic using simulation procedures: Demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioid-dependent outpatients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:412–426. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Replacing relative reinforcing efficacy with behavioral economic demand curves. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;85:73–93. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.102-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16:264–274. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Papandonatos GD, Colby SM, Clark MA, Boergers J, Buka SL. Cigarette smoking and the lifetime alcohol involvement continuum. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam-Hage M, Pomerleau CS, Pomerleau OF, Brower KJ. Unaided smoking cessation among smokers in treatment for alcohol dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselica AM, Borders A. The reinforcing efficacy of alcohol mediates associations between impulsivity and negative drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:490–499. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Epstein AM. Alcohol dose-dependent increases in smoking urge in light smokers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:547–552. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158839.65251.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RG, Williams S, McGee R, Olaman S. Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behaviour Research And Therapy. 1997;35:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, McCarthy EM, Faust AH, Lukas SE. Pretreatment with transdermal nicotine enhances some of ethanol’s acute effects in men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Robert B. Short message service (SMS) technology in alcohol research—a feasibility study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2009;44:423–428. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Jr, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010a;119:106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Eisenberg DT, Lisman SA, Lum JK, Wilson DS. Further validation of a cigarette purchase task for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in college smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16:57–65. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, O’Hagen S, Lisman SA, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Tidey JW, Monti PM. Behavioral economic analysis of cueelicited craving for alcohol. Addiction. 2010b;105:1599–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Fu S, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS. Alcohol, tobacco and obesity are synergistic risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2005;42:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Tam TW, Weisner C. Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: Results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, McDevitt-Murphy ME. Computerized versus motivational interviewing alcohol interventions: Impact on discrepancy, motivation, and drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:628–639. doi: 10.1037/a0021347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Yurasek AM, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, McDevitt-Murphy ME, MacKillop J, Martens MP. Symptoms of depression and PTSD are associated with elevated alcohol demand. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;127:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Fromme K, Del Boca FK, Parks KA, King LP, Pardi AM, Corbin WR. Capturing the moment: Innovative approaches to daily alcohol assessment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:282–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri E, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, Tavani A. Attributable risk for oral cancer in northern Italy. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 1993;2:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape H, Rossow I, Storvoll EE. Under double influence: Assessment of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in general youth populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelucchi C, Gallus S, Garavello W, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C. Alcohol and tobacco use, and cancer risk for upper aerodigestive tract and liver. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2008;17:340–344. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282f75e91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Jahng S, Wood PK, Robertson BM, Epler AJ, Cronk NJ, Sher KJ. The subjective effects of alcohol-tobacco co-use: An ecological momentary assessment investigation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:557–571. doi: 10.1037/a0023033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss UW, Zill P, Koller G, Bondy B, Sokya M. D2 dopamine receptor gene haplotypes and their influence on alcohol and tobacco consumption magnitude in alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2007;42:258–266. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Pallonen UE, Fava JL, Ding L, Niaura R. Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Schiffbauer R. Measuring state changes in human delay discounting: An experiential discounting task. Behavioural Processes. 2004;67:343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger JS, Hollenbeak CS. Potential costs and benefits of statewide smoking cessation in Pennsylvania. Journal of Smoking Cessation. 2010;5:136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Schlecht NF, Franco EL, Pintos J, Negassa A, Kowalski LP, Olveira BV, Curado MP. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol consumption and the risk of cancers of the upper aero-digestive tract in Brazil. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;150:1129–1137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J. Smoking patterns and dependence: Contrasting chippers and heavy smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:509–523. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG. Relations between heavy drinking, gender, and substance-free reinforcement. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:158–166. doi: 10.1037/a0018513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG. The effect of drink price and next-day responsibilities on college student drinking: A behavioral economic analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:57–68. doi: 10.1037/a0021118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Martens MP, Murphy JB, Buscemi J, Yurasek AM, Skidmore J. Reinforcing efficacy moderates the relationship between impulsivity-related traits and alcohol use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:521–529. doi: 10.1037/a0021585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using multivariate statistics. 4th ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tizabi Y, Bai L, Copeland RL, Jr, Taylor RE. Combined effects of systemic alcohol and nicotine on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens shell. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2007;42:413–416. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizabi Y, Copeland RL, Jr, Louis VA, Taylor RE. Effects of combined systemic alcohol and central nicotine administration into ventral tegmental area on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:394–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True WR, Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Heath A C, Tsuang M. Common genetic vulnerability for nicotine and alcohol dependence in men. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:655–661. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Black BC, Rippens PD. Significance of a behavioral economic index of reward value in predicting drinking problem resolution. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:317–326. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Chen Y. The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: National survey results from the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Morgan TJ, Pugh LA, Celinska K, Labouvie EW, Pandina RJ. Evaluating two brief substance-use interventions for mandated college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:309–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurasek AM, Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Buscemi J, McCausland C, Martens MP. Drinking motives mediate the relationship between reinforcing efficacy and alcohol consumption and problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:991–999. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng TZ, Boyle P, Hu HF, Duan J, Jiang PJ, Ma DQ, Mac-Mahon B. Tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and risk of oral cancer: A case-control study in Beijing, People’s Republic of China. Cancer Causes and Control. 1990;1:173–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00053170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]