Abstract

Objective

We evaluate the effects of Medicare Part D coverage gap on pharmacy use among a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries and on medication adherence among two subsamples with heart failure and/or diabetes.

Study Design

A pre-post-with-a-comparison-group design with propensity score weighting.

Methods

We used a 5% of random sample of elderly Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in stand-alone Part D plans in 2007. The comparison group had full coverage in the gap whereas the two study groups had either no coverage or generic-only coverage in the gap. Main outcomes include probability of filling a prescription, monthly pharmacy spending and number of prescriptions filled, and adherence measured by medication possession ratios.

Results

Relative to the comparison group, beneficiaries without drug coverage in the gap reduced the number of prescriptions filled per month by 16.0% (95% CI 15.5%–16.5%) while those with generic drug coverage in the gap reduced it by 10.8% (95% CI 10.3%–11.4%). Most of the reduction in drug use was attributable to the reduction in brand-name drugs. Beneficiaries with heart failure reduced medication adherence for heart failure drugs by 3.6% (95% CI 2.9%–4.2%) and beneficiaries with diabetes reduced anti-diabetic adherence by 10.3% (95% CI 9.4%–11.3%).

Conclusions

Medicare beneficiaries reduced medication use (mainly brand-name drugs) after entering the coverage gap. Medication adherence was reduced to a smaller degree. This suggests that while beneficiaries’ financial burden would continue because of the coverage gap, the gap would not result in a large reduction in medication adherence for essential drugs.

Keywords: medication adherence, drug coverage, Medicare

Medicare Part D offers prescription drug coverage for Medicare beneficiaries. Since the program’s inception in 2006, many beneficiaries have obtained improved drug coverage and increased their use of medications.1–3 The standard Part D benefit in 2007 included an initial $265 deductible, a period in which beneficiaries paid 25 percent of drug costs between $265 and $2,400, a coverage gap in which they paid 100 percent of costs until their total out-of-pocket spending reached a catastrophic limit of $3,850; and a catastrophic coverage period in which they paid 5 percent.4

A major concern is the large coverage gap in the standard Part D design. About one-third of all Medicare beneficiaries enter this coverage gap each year.5 It is possible that, faced with a sudden increase in medication costs, beneficiaries will cut back on their medication use and reduce medication adherence for the essential drugs;6–8 and this, in turn, might put their health at risk leading to subsequent increases in hospitalizations and medical spending.9 Because of the high cost of Medicare and the potential implications for health outcomes, it is important to determine whether the coverage gap leads to reduction in medication adherence for essential drugs.

A few studies have examined the effects of the coverage gap on medication use, but the majority of these studies used pharmacy data either from one local Medicare-Advantage Part D (MA-PD) plan7, 10, 11 or for one specific condition – beneficiaries with diabetes.6, 10, 12–14 One recent study used Medicare Part D data to examine the effects of the coverage gap among two subsamples with hypertension and hyperlipidemia.15 They found that the coverage gap was associated with the reduction in use and adherence of medications for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Another recent study studied aged Medicare beneficiaries with cardiovascular disease enrolled in a stand-alone Part D plan or a retiree drug plan that was administered by CVS Caremark.16 They found that beneficiaries with no financial assistance during the coverage gap were more likely to discontinue their cardiovascular drugs.

In this study, we evaluate the effects of the coverage gap on medication spending and use among all Medicare beneficiaries (those 65 or older) in the national Part D data. In addition, we select two subsamples of those with heart failure and/or diabetes to evaluate the gap effect on medication spending and adherence. We selected these two conditions because they are common in Medicare and the medication treatment is very important and premature discontinuation may lead to increase in subsequent spending on medical care.17, 18 We compare how whether beneficiaries with these chronic conditions respond to the coverage gap differently from the general population.

Our analyses are guided by a number of hypotheses: (1) Medicare beneficiaries will decrease all their medication use regardless drug classes once they enter the gap – and that the decrease will be higher for those with no drug coverage in the gap than those with generic coverage in the gap.19, 20 However, those who anticipate going through the gap and entering the catastrophic period will not reduce their medication use in the gap.7 (2) Beneficiaries will decrease their use of all brand-name drugs more than generic drugs, and if beneficiaries have generic drug coverage they will shift from brand-name to generic drugs.19 (3) Among those with heart failure and/or diabetes, the adherence to cardiovascular and diabetic drugs will decrease in the coverage gap.10

METHODS

Data and Study Population

We obtained beneficiary demographic and enrollment information, plan benefits, prescription drug events and medical claims for a 5% random sample of all aged Medicare beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in PDPs in 2007. We identified two subpopulations of beneficiaries – those with heart failure and/or diabetes. Each subpopulation was identified following two criteria: 1) having a diagnosis for the condition before 1/1/2007, defined by 2006 CMS Chronic Condition Warehouse (CCW) indicators (Appendix Table 1); and 2) using at least one medication for the condition in the initial coverage period so we can ensure that beneficiaries were on medications of interest before entering the coverage gap (Appendix Table 2 provides the list of medications). The study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh.

Study Design

Although the standard Part D benefit includes these four phases, some companies offering Part D drug plans modified the design and offered either “actuarially equivalent” or enhanced plans. In 2007, 72 percent of stand-alone Part D plans (PDPs) had the standard coverage gap, 27 percent of PDPs had some generic coverage in the gap, and less than 1 percent offered coverage for both brand-name and generic drugs.21 In addition, beneficiaries with low-incomes who are eligible for subsidies had a lower copayment throughout the year and did not face a coverage gap.4

Using this variation in drug coverage, we identified two study groups based on the type of coverage they had in the gap (“no-coverage”, “generic-only”) and one comparison group. The comparison group consisted of beneficiaries who had either 12-month Medicaid coverage or 12-month low-income-subsidies (“LIS group”). Thus, the drug coverage for the comparison group did not change throughout the year; that is, they did not face the gap in coverage. Even though the LIS group is different from the two study groups in socioeconomic characteristics, they can still serve the purpose of controlling for the underlying time trends in medication use, because their drug coverage did not change while the study groups had a sudden increase in drug costs once entering the coverage gap.

We used a pre-post-with-a-comparison-group design to assess the impact of the coverage gap on medication and medical care use. This uses a difference-in-difference estimate, comparing the change in pre- and within-gap for each study group, relative to the pre- and within-gap change in the comparison group. This design does not require that study and comparison groups have the same baseline characteristics. As long as different groups have similar baseline trends, we could get unbiased results.22 We tested the baseline pre-gap trends in overall medication use across three groups and they are similar.

We hypothesized that beneficiaries who went through the coverage gap and entered the catastrophic coverage period would not reduce their medication use in the gap.7 We ran regressions to test this hypothesis and found that those entering the catastrophic period did not change their medication use in the gap (Appendix Table 3). Thus, for this study we primarily focused on beneficiaries who entered the gap but did not go through it. That is, each individual in our study sample had a pre-gap and a within-gap period.

To define pre- and within-gap periods, we first identified the index date as the first day that the beneficiary’s total drug spending reached the coverage gap threshold. The pre-gap period was defined as 1/1/2007 to the index date. The within-gap period was defined as the duration between the first day after the index date until 12/31/2007. The index date was included in the pre-gap period because almost all drugs filled by beneficiaries on that day were subject to copayment levels in the initial coverage period. We compared the change in each outcome in the pre-gap and within-gap periods between each study group and the comparison group: no-coverage vs LIS, and generic-only vs LIS groups. We used propensity score weighting mechanism to balance each study group with the comparison group. The propensity score weighting was conducted separately for each group: the general population, as well as each subgroup of those with heart failure and/or diabetes.

Outcomes of Interest

For the pre- and within-gap periods separately, we defined four outcomes to measure medication use: (1) probability of using a medication (1=used a medication; 0=did not use a medication in the study period); (2) mean number of monthly prescriptions filled per month, defined as total number of prescriptions that are standardized by 30-day supply (i.e., a prescription with 90-day supply would count as 3 monthly drugs) divided by the number of months in the study period; (3) mean monthly pharmacy spending per month, and (4) medication adherence measured by medication possession ratio (MPR). For the general population, we focused on the first three outcomes. We measured these outcomes for all medications and then for brand-name and generic drugs separately.

For the patients with chronic conditions, we focused on the mean number of monthly prescriptions filled and the MPR. We examined the mean number of monthly prescriptions filled overall as well as the number of monthly prescriptions for disease specific drugs. We defined the MPR as the proportion of days during a given period (e.g., either pre-gap or within-gap period) that a subject had possession of any drugs used to treat the chronic illness. The drugs filled on the day entering the coverage gap were included in calculating the within-gap MPRs for two reasons: (1) these drugs were used in the within-gap period; and (2) to be consistent with the pre-gap MPR definition where drugs filled on the first day (1/1/2007) were included in the calculation. Similarly, to be consistent with the MPR calculation in the pre-gap period where drugs filled before 1/1/2007 were not included, drugs filled before entering the gap were not included in the calculation for the within-gap adherence. However, the definitions for MPRs should not change the difference-in-difference results because we applied same rules for the study and comparison groups.

Statistical Analysis

To implement the propensity score weighting mechanisms, we conducted a two-stage analysis. In the first stage, we ran two logistic regression models to predict the probability of being in a study group relative to the comparison group, controlling for age, sex, race, number of Elixhauser comorbidities,23 and prescription drug hierarchical condition category (RxHCC). RxHCC is the beneficiary risk adjuster used by CMS to adjust payment to plans for pharmacy costs.24

In the second stage, we ran a difference-in-difference model with the inverse of propensity score as a weight. This effectively assigned a higher weight to individuals in the comparison group who had characteristics similar to those in the study group. In this model, the dependent variable was the difference between within-gap and pre-gap periods for each previously-defined outcome. Because pre- and within-gap- measures are likely to be correlated, the advantage of this approach against using two interrelated outcomes is that one can simply eliminate the correlated structure in two outcomes. The key independent variable was the indicator for being in the study group relative to the comparison group. All the covariates used in calculating propensity scores were included in the model.

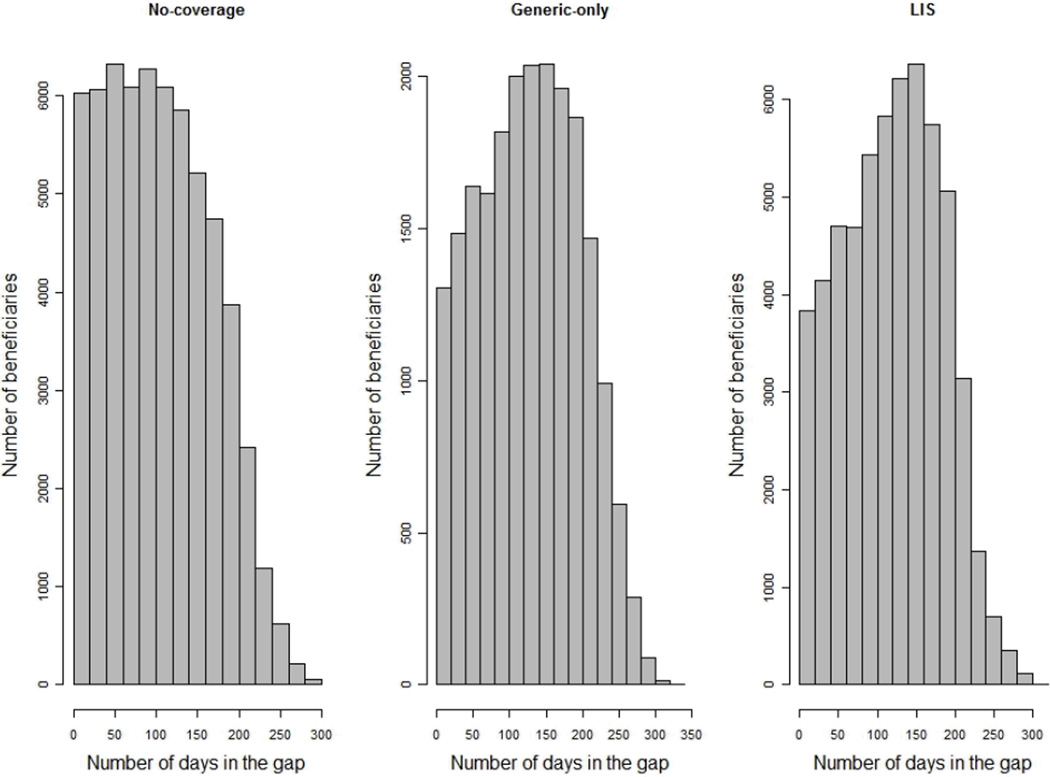

In addition, we controlled for duration of time spent in the coverage gap (Figure 1) in the model because the longer beneficiaries stayed in the gap the more likely they would change their medication use and medical spending. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 2.12.

Figure 1.

Histograms of the Time Spent in the Gap by Group

Abbreviation: LIS = low-income subsidy group.

RESULTS

Table 1 compares the characteristics between each study group and comparison group for beneficiaries whose pharmacy spending exceeded the coverage gap threshold but did not exceed the catastrophic coverage threshold. All the numbers are after adjustment with propensity score weights. After adjustment, all characteristics were comparable (i.e., there is no statistically-significant difference at p>.05) between each study group and the comparison group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population in 2007 After Propensity Score Weighting*

| Variable | No-Coverage vs LIS | Generic-Only vs LIS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Coverage (n=61,040) |

LIS (n=57,699) |

P value |

Generic Only (n=21,219) |

LIS (n=57,699) |

P value |

|

| Female sex, % | 64.4 | 64.6 | 0.54 | 62.2 | 62.3 | 0.87 |

| Race, % | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 93.5 | 93.6 | 0.88 | 94.4 | 94.5 | 0.99 |

| African American | 3.0 | 3.0 | 0.67 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.51 |

| Hispanic | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.67 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.51 |

| Asian | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.62 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.34 |

| Age, % | ||||||

| 65–74 | 40.8 | 40.9 | 0.92 | 46.1 | 46.2 | 0.94 |

| 75–84 | 40.1 | 40.1 | 0.90 | 37.8 | 37.7 | 0.85 |

| ≥ 85 | 19.1 | 19.1 | 0.97 | 16.1 | 16.1 | 0.88 |

| Prescription drug risk score, mean | 0.96±0 | 0.96±0 | 0.97 | 0.99±0 | 0.99±0 | 0.66 |

| No. Elixhauser comorbidities, mean | 2.83±0.01 | 2.83±0.01 | 0.87 | 3.03±0.02 | 3.02±0.01 | 0.71 |

| Diagnosed chronic conditions, % | ||||||

| Hypertension | 59.8 | 56.5 | <.001 | 59.9 | 57.8 | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 43.8 | 32.2 | <.001 | 44.3 | 33.7 | <.001 |

| AMI | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.49 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.01 |

| COPD | 14.2 | 20.7 | <.001 | 14.9 | 22.5 | <.001 |

| Heart failure | 22.6 | 29.9 | <.001 | 25.1 | 30.9 | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 33.6 | 38.5 | <.001 | 39.6 | 40.6 | 0.03 |

| RA/OA | 26.9 | 30.3 | <.001 | 28.2 | 30.5 | <.001 |

Plus-minus values are means±SE.

Abbreviations: LIS = low income subsidies, this group includes duals and non-duals with low-income subsides for Part D; AMI = Acute Myocardial Infarction; COPD = Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RA/OA = Rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis.

All numbers in the table are adjusted using inverse propensity score weights. Propensity scores were calculated using logistic regression models that predict the probability of being in a study group (No-coverage, or Generic-only) relative to the comparison group (LIS group), controlling for age, sex, race, number of Elixhauser comorbidities, and prescription drug hierarchical condition.

Effects of the Coverage Gap on Medication Use and Spending Among the General Population

Table 2 presents the effects of the coverage gap on the probability of using a drug, mean number of monthly prescriptions filled and mean monthly pharmacy spending for all medications for the overall population. There are three main findings:

Table 2.

The Effect of the Coverage Gap on Medication Use Among All Aged Beneficiaries Who Reached the Coverage-gap Threshold But Did Not Reach the Catastrophic-coverage Threshold in 2007

| Type of Medications |

Study & Comparison Groups |

Unadjusted Data* |

Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects† |

% Change, Diff-in- Diff Effects/Pre-Gap Values‡ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre- Gap |

Within- Gap |

Estimate | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

|

Probability of Using a Medication | |||||||

| All medications |

No-coverage | 1.00 | 0.88 | −0.03 | (−0.04, −0.03) | −3.3 | (−3.6, −3.0) |

| Generic-only | 1.00 | 0.94 | −0.02 | (−0.02, −0.01) | −1.6 | (−1.9, −1.3) | |

| LIS | 1.00 | 0.94 | Ref | ||||

| Brand-name | No-coverage | 1.00 | 0.79 | −0.07 | (−0.07, −0.06) | −6.7 | (−7.0, −6.3) |

| Generic-only | 1.00 | 0.84 | −0.08 | (−0.09, −0.08) | −8.2 | (−8.6, −7.8) | |

| LIS | 1.00 | 0.90 | Ref | ||||

| Generics | No-coverage | 0.98 | 0.81 | −0.05 | (−0.05, −0.05) | −5.2 | (−5.5, −4.8) |

| Generic-only | 0.98 | 0.90 | −0.02 | (−0.03, −0.02) | −2.4 | (−2.8, −2.0) | |

| LIS | 0.99 | 0.91 | Ref | ||||

|

Mean Number of Monthly Prescriptions | |||||||

| All medications |

No-coverage | 5.30 | 3.61 | −0.85 | (−0.88, −0.82) | −16.0 | (−16.5, −15.5) |

| Generic-only | 6.14 | 4.65 | −0.66 | (−0.70, −0.63) | −10.8 | (−11.4, −10.3) | |

| LIS | 5.84 | 5.02 | Ref | ||||

| Brand-name | No-coverage | 2.71 | 1.51 | −0.64 | (−0.65, −0.62) | −23.5 | (−23.9, −23.0) |

| Generic-only | 2.87 | 1.66 | −0.61 | (−0.62, −0.59) | −21.1 | (−21.7, −20.5) | |

| LIS | 2.59 | 1.99 | Ref | ||||

| Generics | No-coverage | 2.57 | 2.09 | −0.21 | (−0.23, −0.19) | −8.2 | (−9.0, −7.4) |

| Generic-only | 3.23 | 2.96 | −0.06 | (−0.08, −0.03) | −1.8 | (−2.6, −1.0) | |

| LIS | 3.22 | 2.99 | Ref | ||||

|

Mean Monthly Pharmacy Spending | |||||||

| All medications |

No-coverage | 309 | 184 | −73.15 | (−74.65, −71.66) | −23.7 | (−24.2, −23.2) |

| Generic-only | 351 | 224 | −66.59 | (−68.48, −64.69) | −19.0 | (−19.5, −18.5) | |

| LIS | 331 | 274 | Ref | ||||

| Brand-name | No-coverage | 256 | 143 | −66.65 | (−68.01, −65.30) | −26.1 | (−26.6, −25.5) |

| Generic-only | 277 | 157 | −65.16 | (−66.88, −63.45) | −23.5 | (−24.1, −22.9) | |

| LIS | 262 | 209 | Ref | ||||

| Generics | No-coverage | 52 | 40 | −6.40 | (−6.92, −5.88) | −12.2 | (−13.2, −11.2) |

| Generic-only | 73 | 66 | −1.39 | (−2.11, −0.66) | −1.9 | (−2.9, −0.9) | |

| LIS | 68 | 64 | Ref | ||||

This is the overall population, a national sample of aged beneficiaries regardless which medical conditions they had. The sample sizes for no-coverage, generic-only, and LIS groups are 61040, 21219, and 57699, respectively.

These are average numbers in the pre-gap and within-gap periods, but they are unadjusted and unweighted raw data.

“ Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects” are adjusted estimates from the difference-in-difference model with the inverse of propensity score as a weight. The estimates measure changes in outcomes between within-gap and pre-gap periods in each study group, relative to the changes in outcomes in the comparison group (“Ref”).

“% Change” is calculated using “Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects” divided by pre-gap values.

Abbreviations: LIS = low-income-subsidies; this is the comparison group. Ref = reference group.

First, relative to the comparison group, there were statistically significant reductions in all of the outcomes (probability of using a drug, mean number of monthly drugs filled, and monthly pharmacy spending) in both study groups. However, those with no coverage generally decreased their use of medications more than those with generic drug coverage in the gap.

Second, the overall decrease in monthly medications and spending on drugs was primarily due to the decrease in the use of brand name drugs. For example, those without drug coverage in the gap reduced their overall medication use by 0.85 medications per month (95% CI 0.82– 0.88); and 75 percent of the reduction was accounted for by brand-name drugs and 25 percent by the reduction in generic drugs. This group decreased its monthly pharmacy spending by $73.15 (95% CI $71.66–$74.65), of which $66.65 (95% CI $65.30–$68.01) was for brand-name drugs and $6.40 (95% CI $5.88–$6.92) for generic drugs.

Third, those with only generic coverage in the gap reduced their use of brand-name drugs but did not increase their use of generic drugs. In fact, they decreased their use of generic drugs slightly but negligibly. Among the general population, relative to the comparison group, the generic-only group reduced the number of monthly prescriptions filled by 0.66 (95% CI 0.63–0.70), almost all of this decrease attributable to the reduction in brand-name drugs [0.61 (95% 0.59–0.62)].

Effects of the Coverage Gap among Patients with Chronic Conditions

Beneficiaries with heart failure and/or diabetes decreased their overall use of medications and the overall decrease was similar to that found for the general population (Table 3). They also decreased their use of the drugs specific to their conditions. The relative decreases in the condition-specific drugs were similar to those observed for the overall drugs.

Table 3.

The Association of the Coverage Gap with Mean Number of Monthly Prescriptions Among Aged Beneficiaries Who Reached the Coverage-gap Threshold But Did Not Reach the Catastrophic-coverage Threshold in 2007, by Health Condition

| Health Conditions |

Study & Comparison Groups |

Unadjusted Data* |

Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects† |

% Change, Diff-in-Diff Effects/Pre-Gap Values‡ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Gap | Within- Gap |

Estimate | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

|

Heart Failure | |||||||

| All medications | No-coverage | 6.36 | 4.70 | −0.83 | (−0.89, −0.77) | −13.1 | (−14.0, −12.2) |

| Generic-only | 7.27 | 5.78 | −0.60 | (−0.67, −0.54) | −8.3 | (−9.2, −7.4) | |

| LIS | 6.74 | 5.85 | Ref | ||||

| HF medications | No-coverage | 2.85 | 2.09 | −0.33 | (−0.36, −0.3) | −11.7 | (−12.8, −10.6) |

| Generic-only | 3.12 | 2.49 | −0.20 | (−0.24, −0.16) | −6.4 | (−7.6, −5.3) | |

| LIS | 2.77 | 2.35 | Ref | ||||

|

Diabetes | |||||||

| All medications | No-coverage | 6.21 | 4.27 | −0.95 | (−1.01, −0.89) | −15.3 | (−16.3, −14.4) |

| Generic-only | 7.07 | 5.39 | −0.67 | (−0.74, −0.6) | −9.5 | (−10.4, −8.5) | |

| LIS | 6.64 | 5.64 | Ref | ||||

| Diabetes medications |

No-coverage | 1.31 | 0.83 | −0.22 | (−0.24, −0.2) | −17.2 | (−18.7, −15.6) |

| Generic-only | 1.40 | 1.00 | −0.14 | (−0.16, −0.11) | −9.8 | (−11.7, −7.9) | |

| LIS | 1.28 | 1.01 | Ref | ||||

The sample sizes for the subsample of beneficiaries with heart failure are 11,542 in the no-coverage group, 4,578 in the generic-only group and 16,786 in the LIS group.

The sample sizes for the subsample of beneficiaries with diabetes are 12,349 in the no-coverage group, 5,308 in the generic-only group and 15,797 in the LIS group.

These are average numbers in the pre-gap and within-gap periods, but they are unadjusted and unweighted raw data.

“Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects” are adjusted estimates from the difference-in-difference model with the inverse of propensity score as a weight. The estimates measure changes in outcomes between within-gap and pre-gap periods in each study group, relative to the changes in outcomes in the comparison group (“Ref”). Propensity score model was conducted separately for each subpopulation.

“% Change” is calculated using “Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects” divided by pre-gap values.

Abbreviations: LIS = low-income-subsidies; this is the comparison group. Ref = reference group.

The decrease in medication use was accompanied by the decrease in medication adherence in both groups, but the decrease in adherence was smaller than the reduction in the number of prescriptions filled (Table 4). In addition, relative to the comparison group, the decrease in medication adherence was always larger in the no-coverage group than in the generic-only group. In the heart failure sample, the MPR for heart failure drugs among the no-coverage group dropped from 0.87 in the pre-gap period to 0.83 in the within-gap period, while the MPR for those with generic-only coverage dropped from 0.87 to 0.86. Although statistically significant, the relative reduction in adherence for heart failure is negligible. The same pattern was observed for those with diabetes although decrease in medication adherence was larger in this group.

Table 4.

The Association of the Coverage Gap with Medication Adherence Among Aged Beneficiaries With Heart Failure and/or Diabetes

| Health Conditions |

Study & Comparison Groups |

Unadjusted Data* | Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects† |

% Change, Diff- in-Diff Effects/Pre-Gap Values‡ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Gap | Within- Gap |

Estimate | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

|

Medication Possession Ratio | |||||||

| Heart failure | No-coverage | 0.868 | 0.829 | −0.03 | (−0.04, −0.03) | −3.6 | (−4.2, −2.9) |

| Generic-only | 0.873 | 0.863 | −0.01 | (−0.02, 0.00) | −1.1 | (−1.8, −0.4) | |

| LIS | 0.853 | 0.850 | Ref | ||||

| Diabetes | No-coverage | 0.763 | 0.656 | −0.08 | (−0.09, −0.07) | −10.3 | (−11.3, −9.4) |

| Generic-only | 0.770 | 0.696 | −0.05 | (−0.06, −0.05) | −7.1 | (−8.2, −6.1) | |

| LIS | 0.754 | 0.729 | Ref | ||||

The sample sizes for the subsample of beneficiaries with heart failure are 11,542 in the no-coverage group, 4,578 in the generic-only group and 16,786 in the LIS group.

The sample sizes for the subsample of beneficiaries with diabetes are 12,349 in the no-coverage group, 5,308 in the generic-only group and 15,797 in the LIS group.

These are average numbers in the pre-gap and within-gap periods, but they are unadjusted and unweighted raw data.

“Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects” are adjusted estimates from the difference-in-difference model with the inverse of propensity score as a weight. The estimates measure changes in outcomes between within-gap and pre-gap periods in each study group, relative to the changes in outcomes in the comparison group (“Ref”). Propensity score model was conducted separately for each subpopulation.

“% Change” is calculated using “Diff-in-Diff Coverage Gap Effects” divided by pre-gap values.

Abbreviations: LIS = low-income-subsidies; this is the comparison group. Ref = reference group.

COMMENT

Medicare beneficiaries decreased their medication use once they entered the gap – and the decrease in use was consistently higher for those who had no coverage in the gap than those with generic drug coverage in the gap. We hypothesized that beneficiaries would reduce their brand-name drugs after entering the coverage gap; and if they had generic drug coverage, they would shift their brand-name to generic drugs. We did observe that beneficiaries reduced their use of brand-name drugs substantially more than generic drugs, but those with generic drug coverage did not switch from brand-name to generic drugs. This is partially because those in the generic-only group tended to use more generic drugs in the initial coverage gap period.

We adjusted the time spent in the gap in our model so the beneficiaries spending less time in the gap contributed less to the regression results. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analysis by excluding those beneficiaries who stayed in the gap for less than one month or less than two months. The results are robust.

The overall coverage gap effects in the no-coverage group on medication use are similar to those found in an earlier study examining beneficiaries enrolled in MA-PD products.7 However, the effects for those with generic drug coverage were different – in the earlier study beneficiaries with generic drug coverage actually increased their use of generic drugs in the gap whereas in this population no such increase was observed.7 This difference may be due to different practices between traditional fee-for-service Medicare and Medicare advantage plans. For example, MA-PD plans might have better medication management program or chronic disease management program.

A major strength of this study is that we had a random sample of aged Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in PDP products. We examined the effect of the coverage gap on a national overall sample of Medicare beneficiaries as well as those with two prevalent chronic conditions: heart failure and/or diabetes. We included all qualified Medicare beneficiaries – including those in nursing homes. (We estimated the model excluding nursing home residents, and the results were similar).

We used the pre-post-with-a-comparison-group design, the strongest quasi-experiment observational study design. The key to this approach is that the drug coverage in the comparison group did not change in the pre-gap and within-gap periods; while study groups were exposed to a sudden increase in medication price. Even though the comparison group is different in socioeconomic status from the study groups, all groups had similar baseline trends in medication use. Thus, this study design may lead to unbiased results.22 However, we acknowledge that we can eliminate selection bias.

The weakness of our study is that we did not explicitly estimate the anticipatory effects of the coverage gap, namely, beneficiaries might change their behaviors before they entered the coverage gap. Thus, we might underestimate the effects of the coverage gap. We did observe the signs of anticipatory effects. For example, beneficiaries with generic coverage were more likely to use generic drugs in the pre-gap period; and those who went through the coverage gap did not change their drug use in the gap. By focusing on those who did not go through the coverage gap we mitigated the problem.

Current provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) on the Part D include: 1) starting in 2010, beneficiaries entering the coverage gap receive a $250 rebate; 2) starting in 2011, beneficiaries pay 50 percent for brand-name drugs and 93 percent for generic drugs that are used in the coverage gap; and 3) the gap size will be gradually reduced in order to eliminate it by 2020.25 In the 2011 standard Part D benefit, the threshold entering the coverage gap is $2,840 in total pharmacy spending and the threshold entering the catastrophic period is $4,550 in total out-of-pocket pharmacy spending.26 Thus, coverage gap will continue to be an important issue that deserves a close attention from policy makers, providers and beneficiaries. However, if our results are replicated, it would indicate that while the financial burden on Medicare beneficiaries would continue because of the coverage gap, the gap would not result in a large reduction in medication adherence.

Take-away points.

We examined the effect of the coverage gap on a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries as well as those with heart failure and/or diabetes. Although beneficiaries’ financial burden would continue due to the coverage gap until 2020, the gap would not result in a large reduction in medication adherence for essential drugs.

Medicare beneficiaries reduced medication use (mainly brand-name drugs) after entering the coverage gap.

Beneficiaries with generic drug coverage in the gap reduced their drug use less.

However, medication adherence was reduced to a much smaller degree for essential drugs used to treat heart failure and diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Funding source:

NIMH RC1 MH088510, AHRQ R01 HS018657.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang Y, Donohue JM, Lave JR, O’Donnell G, Newhouse JP. The impact of the Medicare Part D drug benefits on pharmacy and medical care spending. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):52–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0807998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Lave JR, Donohue JM, Fischer MA, Chernew ME, Newhouse JP. The impact of Medicare Part D on medication adherence among older adults enrolled in Medicare-Advantage products. Med Care. 2010;48(5):409–417. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d68978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ketcham JD, Simon KI. Medicare Part D's effects on elderly patients' drug costs and utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(11 Suppl):SP14–SP22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed July 10, 2011];The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. 2007 http://kff.org/medicare/upload/7044-06.pdf.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed February 3, 2011];Medicare Part D data symposium presentations. 2010 http://www.cms.gov/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/09_ProgramReports.asp.

- 6.Schmittdiel JA, Ettner SL, Fung V, et al. Medicare Part D coverage gap and diabetes beneficiaries. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(3):189–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Donohue JM, Newhouse JP, Lave JR. The effects of the coverage gap on drug spending: a closer look at Medicare Part D. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):w317–w325. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Pedan A, et al. The effect of Medicare Part D coverage on drug use and cost sharing among seniors without prior drug benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):w305–w316. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu J, Price M, Huang J, et al. Unintended consequences of caps on Medicare drug benefits. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2349–2359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raebel MA, Delate T, Ellis JL, Bayliss EA. Effects of reaching the drug benefit threshold on Medicare members' healthcare utilization during the first year of Medicare Part D. Med Care. 2008;46(10):1116–1122. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318185cddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nair KV, Frech-Tamas F, Jan S, Wolfe P, Allen RR, Saseen JJ. Comparing pre-gap and gap behaviors for Medicare beneficiaries in a Medicare managed care plan. J Health Care Finance. 2011;38(2):38–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duru OK, Mangione CM, Hsu J, et al. Generic-only drug coverage in the Medicare Part D gap and effect on medication cost-cutting behaviors for patients with diabetes mellitus: the translating research into action for diabetes study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(5):822–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu Q, Zeng F, Patel BV, Tripoli LC. Part D coverage gap and adherence to diabetes medications. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(12):911–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fung V, Mangione CM, Huang J, et al. Falling into the coverage gap: Part D drug costs and adherence for Medicare Advantage prescription drug plan beneficiaries with diabetes. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(2):355–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li P, McElligott S, Bergquist H, Schwartz JS, Doshi JA. Effect of the medicare part d coverage gap on medication use among patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):776–784. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polinski JM, Shrank WH, Glynn RJ, Huskamp HA, Roebuck MC, Schneeweiss S. Beneficiaries with cardiovascular disease and the part d coverage gap. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(3):387–395. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Writing Committee Members, Hunt SA, Abraham WT, et al. 2009 Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119(14):e391–e479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D, Sarkisian CA. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5 Suppl Guidelines):S265–S280. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.51.5s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huskamp HA, Deverka PA, Epstein AM, Epstein RS, McGuigan KA, Frank RG. The effect of incentive-based formularies on prescription-drug utilization and spending. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2224–2232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa030954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huskamp HA, Frank RG, McGuigan KA, Zhang Y. Impact of a three-tier formulary on demand response for prescription drugs. Journal of Economics and Managment Strategy. 2005;14(3):729–753. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed April 22, 2011];Medicare Part D 2010 data spotlight: the coverage gap. 2009 http://kff.org/medicare/upload/8008.pdf.

- 22.Meyer BD. Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. Journal of Business and Economics Statistics. 1995;13:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed February 3, 2010];Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Prescription Drug Hierarchical Condition Category (RxHCC) Model Software. 2010 http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/06_Risk_adjustment.asp.

- 25.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed July 10, 2011];Summary of key changes to Medicare in 2010 health reform law. 2010 http://kff.org/medicare/upload/8107.pdf.

- 26.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed July 10, 2011];The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. 2010 http://kff.org/medicare/upload/7044-11.pdf.