Macromolecules sensitized to a user-defined signal represent important tools in chemical and cellular biology, with potential applications in medical diagnostics. A variety of engineering techniques have been developed to produce macromolecular switches, yet these efforts have focused primarily on modifying single-chain proteins (for recent examples see[1-5]). We have designed an approach suited to controlling the growing number of “split” proteins, comprised of self-assembling protein fragments. The method depends on the introduction of structural distortion to one of the complementary fragments, using a conditionally stable tether. Distortion serves to diminish the mutual affinity of the two fragments, and thereby blocks protein self assembly until the tether is cleaved. Here we describe how this strategy was employed to create a protease-activatable switch based on split green fluorescent protein (GFP). The switch functions in vitro and in E. coli with a gain of fluorescence, providing operational advantages over existing GFP-based protease reporters.

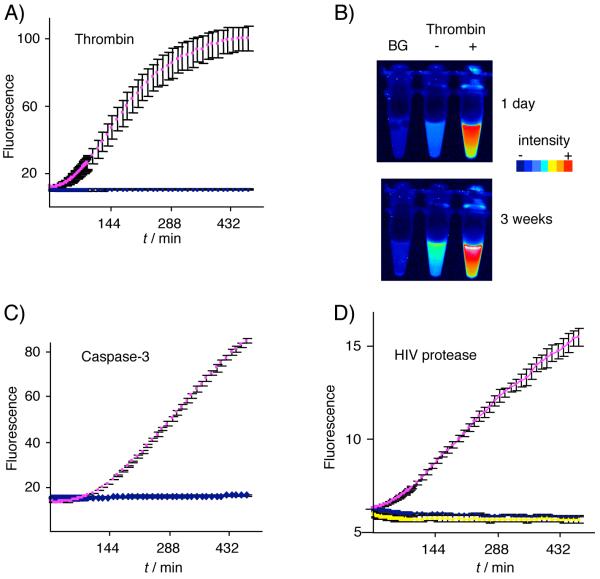

As an experimental test of conditional distortion to control split protein function, we attempted to convert self-assembling GFP into a protease switch. Waldo and coworkers initially selected GFP1-10 (amino acids 1-214 amino acids) and GFP11 (amino acids 215-231) as soluble, non-fluorescent fragments of GFP that associate strongly when mixed, resulting in the emission of green fluorescence.[6, 7] This GFP1-10/GFP11 system has proven useful as a screen for protein solubility[6] and aggregation.[8] In native GFP, the smaller GFP11 fragment is an elongated beta-strand, >40 Å in length.[9] We hypothesized that if the extended structure of GFP11 were sufficiently altered – into a bent conformation, for example – productive binding to GFP1-10 would be impeded. Our approach to the distortion of GFP11 and to the rendering of that distortion reversible through proteolysis was to constrain the N- and C- termini of GFP11 closely in space using a protease-sensitive tether. Successive steps of tether proteolysis and fragment assembly would therefore be necessary to reconstitute functional GFP (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Successive steps of proteolysis and fragment association reconstitute GFP.

To produce a constrained derivative of GFP11, we embedded the peptide as a surface loop in a heat- and acid-stable 7-kDa protein, called eglin c. In addition to the protein’s thermodynamic stability,[10] the prominent surface-exposed loop of eglin c, which we intended to replace with GFP11, can be proteolytically cleaved without compromising the protein’s global fold [11]. We substituted sequences into eglin c encoding GFP11 (RDHMVLHEYVNAAGIT), followed by a thrombin protease cleavage site (LVPRG), as a gapped duplex oligonucleotide[12], using the gene’s internal AatII and MluI restriction sites. We prepared a second construct in an identical manner, but with the sequence encoding the peptide SSKLQ in place of LVPRG; SSKLQ is not cleaved by thrombin[13]. Both peptides were well tolerated by the scaffold, as evidenced by overproduction of soluble chimeric protein in E. coli at levels comparable to that of the unsubstituted scaffold (Supporting Figure 1a).

The yields of chimeric protein were sufficiently high to permit assaying directly from cell lysate without purification. If the chimeric protein’s fold is similar to that of the unsubstituted scaffold, the N- and C-termini of GFP11 will be brought within 11 Å of each other,[14] considerably closer than their native separation in GFP. To test for the presence and the functional consequences of a conformational distortion of GFP11, we combined the chimeric proteins with unmodified GFP1-10 (Sandia Biotech) in cleavage buffer, and determined whether GFP reconstitution was protease dependent. For brevity, we will refer to the combination of the chimeric protein and unmodified GFP1-10 as Pro-GFPX (n), where X(n) denotes the inserted protease cleavage site. Consistent with the scheme in Figure 1, we observed a substantial increase in the fluorescence of solutions containing Pro-GFPLVPRG only after the addition of active thrombin (Figure 2a, b).

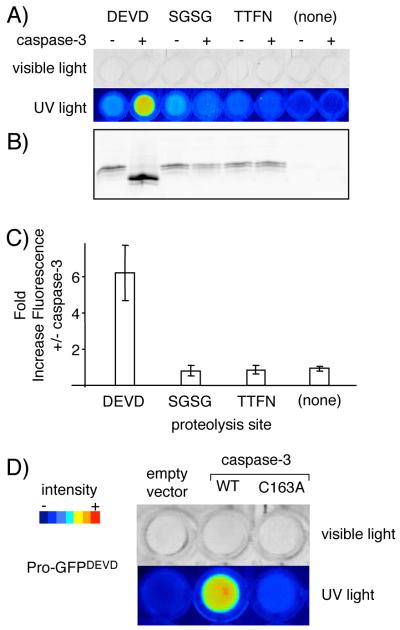

Figure 2.

Pro-GFP is a latent fluorophore activated by proteolysis. A) Thrombin-catalyzed processing of Pro-GFPLVPRG. Fluorescence traces of Pro-GFPLVPRG over time, show an increase in signal in the presence of thrombin protease (pink) but not in the sample lacking protease (blue). Reactions were carried out in duplicate at 27 °C in cleavage buffer, and were monitored for fluorescence (λex/λem, 485 nm/540 nm) at 5-min intervals. Error bars indicate data range from duplicate samples. B) Direct visualization of long-lived signal from protease-treated Pro-GFP. Fluorescence of Pro-GFPLVPRG samples is shown 24 h and 3 weeks after addition of thrombin (right) or buffer only (left). The background tube (BG) contained thrombin and GFP1-10 only. Tubes were imaged with a Typhoon fluorescence scanner (λex/λem, 488 nm/580 nm). C) & D) Processing of Pro-GFPDEVD by the cysteine protease, caspase-3 C) and processing of Pro-GFPGIFLET by HIV protease D). Reaction conditions are as in (A) except that for C), TCEP was included in the assay mixture, and for D), Pro-GFP11GIFLET proteolysis was carried out in MES buffer (pH 6.1) with EDTA (10 mM). The yellow trace in D) is data from samples that contained Pro-GFPGIFLET, HIV protease, and the tight-binding HIV protease inhibitor, nelfinavir (10 μM).

The gain of signal produced by Pro-GFPLVPRG solutions after adding thrombin suggested specific processing of the scaffold, as we subsequently confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis (Supporting Figure 1b). The kinetics of fluorogenesis, apart from an initial lag phase, appeared similar to that of the reconstitution reaction with the unmodified split GFP system (Figure 2a).[6, 7] When the Pro-GFPLVPRG/thrombin reaction was repeated with successively lower concentrations of protease, or in the presence of successively higher amounts of a general serine protein inhibitor, phenylmethylsufonyl fluoride, we observed that the rate and the extent of fluorescent output were suppressed (Supporting Figure 2a, b). These results are consistent with the coupling of GFP reconstitution to protease activity. We noted that the fluorescence signal following thrombin treatment was long-lasting, persisting above the signal from Pro-GFPLVPRG in buffer alone for at least 3 weeks (Figure 2b). Thus, proteolysis apparently does not interfere with GFP reconstitution or the stability of the reconstituted complex.[15] Although measurable fluorescence was emitted from samples of Pro-GFPLVPRG in the absence of thrombin, the signal did not increase during the 7.5 h assay and we could reliably detect fluorogenesis with ≥0.015 units of thrombin per reaction.

We detected no increase in fluorescence after addition of thrombin to Pro-GFPSSKLQ, suggesting a lack of processing at SSKLQ, or at any of the three potential arginine substrate residues in the scaffold (data not shown). The quenched fluorescence of Pro-GFPLVPRG in the absence of thrombin and Pro-GFPSSKLQ with a non-cognate site +/− thrombin suggests that the conformation of GFP11 in the intact scaffold is distorted, and that distortion must be relieved enzymatically to permit productive binding to GFP1-10.

Replacing the protease site in the scaffold with the sequence DEVD or GIFLET maintained the caging effect on GFP11 and the solubility of the chimeric protein. When combined with GFP1-10 to produce Pro-GFPDEVD or Pro-GFPGIFLET, each of the two precursors produced a gain in fluorescence upon site-specific proteolysis: Pro-GFPDEVD by the cysteine protease, human caspase-3, and Pro-GFPGIFLET by the aspartic acid protease, HIV protease (Figure 2c, d).[16, 17]

Unlike the serine and cysteine proteases, HIV protease catalyzes peptide bond cleavage by direct water attack, and has a mildly acidic pH optimum. The scaffold constraining GFP11 is acid-stable,[18] so protease digestions at reduced pH is feasible; however, GFP assembly becomes less efficient at pH values below neutrality. To minimize complications arising from pH sensitivity, we separated proteolysis and assembly into discrete steps. Using this sequential format, we also tested the capacity of HIV protease to activate Pro-GFPGIFLET in the presence of the tight-binding inhibitor, nelfinavir.[19] When aliquots of the reactions were mixed with GFP1-10, a time-dependent increase in fluorescence was apparent in the Pro-GFPGIFLET/HIV protease sample, whereas, no increase in fluorescence was apparent in the absence of protease or in the sample containing HIV protease with nelfinavir (Figure 2d). Thus, the functional reconstitution of GFP can be conformationally constrained using tethers of varying sequence and can be rescued in vitro with enzymatically active proteases that cleave by distinct mechanisms.

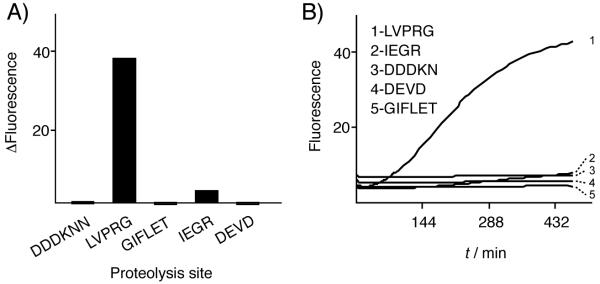

We next evaluated the potential of this technology to map protease substrate-specificity. Reactions were carried out between thrombin and Pro-GFPLVPRG, Pro-GFPGIFLET, Pro-GFPDEVD, and two additional variants, Pro-GFPIEGR and Pro-GFPDDDKNN. The latter two were created for assaying Factor Xa protease and enteropeptidase, respectively. For the processing of Pro-GFPIEGR and Pro-GFPDDDKNN by their cognate proteases, see Supporting Figure 3. As shown in Figure 3, the most intense signal in this experiment was emitted from the thrombin/Pro-GFPLVPRG samples. The weak but reproducible signal produced from the thrombin/Pro-GFPIEGR reaction may be explained by a low level of contaminating Factor Xa in the commercial preparation, or by promiscuous cleavage after the Arg residue in IEGR. Thrombin has been reported to cleave at a GlyArg↓ site in the protein hormone cholecystokinin.[20] The results of this pilot experiment further demonstrate that activation of Pro-GFP is occurring site-specifically. In addition, the dynamic range of Pro-GFP reactions in vitro appears sufficient to allow differentiation among an efficient protease substrate, a substrate with borderline activity, and a non-substrate.

Figure 3.

Site-specific selectivity in Pro-GFP activation. A) Extent of reaction. Change in fluorescence (ΔF=Ffinal-Finitial) was measured after a 7.5-h incubation of each potential Pro-GFP substrate, bearing the indicated cleavage site, with 1.5 units of thrombin. Reaction conditions as in Figure 2. B) Continuous monitoring. GFP fluorescence (λex/λem, 485 nm/540 nm) from the same samples was measured at 5-min intervals..

A bacterial screen for protease activity based on Pro-GFP could be useful in structure/function analyses of proteases, or for visualizing protease-dependent processes in a biological context. We therefore examined the possibility of protease-promoted GFP reconstitution in E. coli, by co-expressing procaspase-3 protease, which undergoes autocatalytic activation to caspase-3 in E. coli,[21] along with the two components of Pro-GFPDEVD. As substrate controls for this experiment, we prepared strains co-expressing caspase-3 with either of the two Pro-GFP variants displaying arbitrary non-caspase-3 cleavage sites, Pro-GFPSGSG and Pro-GFPTTFN. A fourth strain co-expressing caspase-3 and GFP1-10 in the absence of GFP11 was prepared as a control for background fluorescence. Consistent with the idea of site-specific proteolytic activation of Pro-GFP, we observed the strongest fluorescent signal emitted from E. coli cultures co-expressing caspase-3 and Pro-GFPDEVD (Figure 4a).

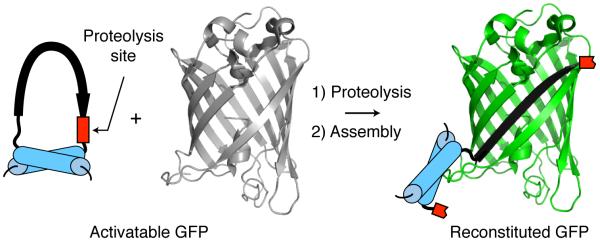

Figure 4.

Pro-GFP detects protease activity in E. coli. A) Activation of Pro-GFPDEVD by co-expressed human caspase-3. E. coli cultures expressing one of each of the indicated Pro-GFP variants in the presence or absence of co-expressed caspase-3 were visualized under white light (top) and UV light (λex/λem at 488 nm/580 nm) (bottom). The two right-most control strains co-express GFP1-10 with or without caspase-3. B) Identification by gel shift of processed Pro-GFPDEVD in strain co-expressing caspase-3. Aliquots of bacterial lysate were resolved by SDS-PAGE (18%) without pre-boiling, and were then imaged with a Typhoon fluorescence scanner (λex/λem at 488 nm/580 nm). C) Quantification of Pro-GFPDEVD activation in soluble bacterial lysates. Average fold increase in GFP fluorescence (λex/λem at 488 nm/540 nm) with caspase-3 coexpression, over four independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation. D) Activation of Pro-GFPDEVD by active caspase-3, but not by a catalytically inactive caspase mutant (C163A). Liquid cultures were imaged for fluorescence as in A).

Specific processing of Pro-GFPDEVD in the caspase-3 co-expression strain was also detectable by analysis of cell lysate (Figure 4b), and by analysis of the purified chimeric protein (Supporting Figure 4) using SDS-PAGE. Quantitative comparison of GFP fluorescence showed ≥6-fold higher values in normalized cell lysate of the Pro-GFPDEVD/caspase-3 strain relative to the cell lysate from the substrate control strains and the Pro-GFPDEVD strain lacking caspase-3 (Figure 4c). Caspase-3 processing of Pro-GFPDEVD, but not Pro-GFPSGSG or Pro-GFPTTFN, is consistent with this protease’s specificity.[22] As a final control, we compared the in vivo activation of Pro-GFPDEVD by active caspase-3 with a catalytically inactive caspase mutant (C163A). Predictably, no signal was produced with the inactive protease above the level of the empty vector control, indicating that GFP reconstitution depends on activity of the co-expressed protease (Figure 4d). The results of these experiments demonstrate that the preparation and subsequent activation of Pro-GFP in vitro, described above, can be replicated in the context of living E. coli.

We have introduced a strategy to prepare split proteins in a conditionally inactive form using conformational distortion that is maintained by a cleavable tether. We applied this method to convert split GFP into a latent fluorophore that can be activated by site-specific proteolysis. Pro-GFP served as a biofluorogenic substrate for representative enzymes from the three major protease classes: serine, cysteine, and aspartic acid. As a reporter, Pro-GFP resembles that of a quenched fluorescent peptide in its coupling of protease activity, or inhibition, to an optical signal. The use of GFP, in the words of Heim and Tsien, “gives the unique possibility of replacing organic synthesis with molecular biology, and monitoring proteases in situ in living cells and organisms”.[23] Indeed, we found that Pro-GFP can function specifically as a novel reporter of protease activity in live E. coli. Variants of GFP are available in an ever-increasing array of hues, and bacterial phytochromes extend the range of fluorescent proteins into the infrared region for deep-tissue imaging.[24] Conversion of these natural fluorophores into similar Pro forms will provide a platform for multiplex protease imaging and analysis in a biological context.

The importance of proteases as regulators in biological processes and as indicators of disease cannot be overstressed.[25, 26] Accordingly, GFP-based protease reporters have been described before. [27-32] (For luciferase-based reporters, see [33-35]). The feature distinguishing Pro-GFP from existing systems is that Pro-GFP reports proteolysis both in vitro and in vivo with a gain of fluorescence, rather than with a loss of fluorescence. We anticipate that extensions of our approach will involve split macromolecules unrelated to GFP, and include moieties other than peptides as cleavable tethers.

Experimental Section

Reagents

Proteases obtained commercially included enteropeptidase (Genscript), human thrombin (Sigma), Factor Xa (New England Biolabs), and human caspase-3 (BioVision). DNA restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Oligonucleotides were prepared by Integrated DNA Technologies. Stock solutions of nelfinavir (Tocris) and phenymethylsulfonylchloride (Sigma) were prepared in ethanol immediately prior to use. Solutions of GFP1-10 (0.4 mg/ml) were purchased from Sandia Biotech. A pET-23b plasmid encoding the human procaspase-3 was obtained from ATCC.

Plasmids

The eglin c gene encoding the scaffold for GFP11X(n) was PCR-amplified from pET28 eglin c F10W (kindly provided by Dr. Andrew Lee, UNC Chapel Hill). Eglin c-79 used for in vitro Pro-GFPase assays was amplified with primers 1879 and 1907 (Table S1). Eglin c-85 used to prepare Pro-GFP in E. coli, was amplified with primers 2284 and 2285 (Table S1). The reverse primer, 2285, adds the ssrA degradation tag to the carboxy terminus of eglin c. This ssrA tag was added to eglin c to reduce the steady-state quantities of the protein and thereby avoid the potential for spurious association with GFP1-10 independent of proteolysis.

To create the eglin c-GFP11(X)n chimeras, we replaced an internal segment of the eglin c gene that encoded the protein’s native loop, residues Ser42 to Arg49, by an oligonucleotide encoding GFP11 (underlined) and a protease cleavage site (X)n separated by glycine (G) spacers: GRDHMVLHEYVNAAGITG(X)nG. Each oligo was annealed to two shorter oligos, 1990 and 1991 (Table S1), and the resulting gapped duplex was ligated into eglin c’s unique AatII and MluI sites. Eglin c-79-GFP11(X)n derivatives were cloned into the NcoI and XhoI sites of pET28a (Novagen) for over-expression in E. coli. Eglin c-85-GFP11(X)n derivatives were cloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of pACYC-duet-GFP1-10 for co-expression with GFP1-10. The GFP1-10 gene fragment used in constructing pACYC-duet-GFP1-10 was kindly provided by Professor Geoffrey Waldo (Los Alamos National Labs).

BL21(DE3) strains expressing Pro-GFP variants were generated for potential in vivo processing by co-expressed human caspase-3. The Pro-GFP variants included Pro-GFPDEVD, and two noncognate controls, Pro-GFPSGSG and Pro-GFPTTFN. A fourth BL21(DE3) strain expressing GFP1-10 without its complementary GFP11 peptide was generated as a background control. Into these strains, we electroporated either pET-22b (Novagen/EMD Biosciences), or a pET-22b plasmid expressing human pro-caspase-3. Early in this work, we found that the stringent T7/lac promoter of pET-22b is an important factor that enhances signal/noise ratio in the assay while avoiding toxicity associated with leaky expression of caspase-3.

Eglin c-GFP11(X)n expression

Overnight liquid cultures of the BL21(DE3) strains harboring pET28a eglin c-GFP11(X)n expression plasmids were seeded at a 1-to-50 dilution into 5 ml of LB broth (10 g/l bacto-tryptone, 5 g/L bacto-yeast extract, 10 g/l NaCl) with (Kanamycin 25 μg/ml), grown to an OD600 of 0.7 at 37 °C, then induced with 0.3 mM IPTG for 4 h at 30 °C. Cultures were pelleted and frozen at −80 °C. To extract soluble GFP11X(n), we resuspended thawed pellets in 300 μl of BPER-II reagent (Pierce Inc.) by pippeting, then vortexing for 2 min, followed by centrifugation at 14x g for 10 min. Cleared lysates typically contained 0.8 mg/ml of total soluble protein (BioRad Protein Assay Reagent), with 0.1 mg/ml of GFP11(X)n.

In vitro Pro-GFP(X)n processing

Pro-GFP was prepared by mixing 10 μl of 10-fold diluted E. coli lysate containing over-expressed GFP11(X)n with 100 μl of GFP1-10 (3.4 mg/ml) in TNG buffer (50mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.1M NaCl, 10% glycerol). Prior to adding protease, this mixture was incubated for >5 h or overnight, at 22 °C, during which time the fluorescence signal attained a constant value. Fluorescence values ((λex/λem, 485 nm/540 nm) of Pro-GFP(X)n solutions in the presence or absence of added protease were recorded at 5-min intervals on a Biotek5 fluorescent plate reader, with Gen5 operating software.

In vivo Pro-GFP(X)n expression and processing

BL21(DE3) strains expressing Pro-GFPDEVD and human caspase-3 along with control expression strains, were transferred from freshly grown bacterial colonies on LB agar into 7 ml of LB buffer with chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml) and ampicillin (100 μg/ml). After growth at 37 °C to midlog phase (OD600, 0.7), cultures were induced with 0.3 mM IPTG and then incubated at 25 °C for an additional 4 h. We imaged live cultures directly with the Typhoon scanner after replacing spent media with Tris buffer (0.1 M, pH 8). For protein analysis, cultures were centrifuged, and the pelleted cells were stored at −80 °C. Total soluble protein was extracted from the thawed cells with B-PERII reagent (ThermoScientific Inc.), as described above, and analyzed for steady-state fluorescence (λex/λem, 485 nm/540 nm) on the Biotek5 plate reader. Lysates were also separated by SDS-PAGE (15%) without pre-boiling, followed by gel imaging using a Typhoon scanner (λex/λem, 488 nm/580 nm) and the Image Works software. For analysis of the specific cleavage of the eglin c-GFP11X(n) by co-expressed caspase-3, His-tagged eglin c-GFPDEVD was purified from the soluble lysate using a 1 ml Ni-NTA column (Quiagen) and was then resolved by denaturing SDS-PAGE (18%) followed by Coomassie blue staining.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Celia Schiffer (UMass Medical School) for providing purified HIV protease, Dr. James Wells (UCSF) for a plasmid encoding procaspase-3 (C163A), and Dr. Geoffrey Waldo (Los Alamos National Laboratory) for a plasmid encoding GFP1-10. We thank John Dansereau for help preparing the figures and Maryellen Carl for expert help preparing the manuscript. We acknowledge the Wadsworth Center’s Molecular Genetics Core for DNA sequencing. This work was supported by NIH grants GM39422 and GM44844 to MB.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW or from the author.

References

- [1].Plainkum P, Fuchs SM, Wiyakrutta S, Raines RT. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:11511. doi: 10.1038/nsb884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wu YI, Frey D, Lungu OI, Jaehrig A, Schlichting I, Kuhlman B, Hahn KM. Nature. 2009;461:10410. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mitrea DM, Parsons LS, Loh SN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907668107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Schierling B, Noel AJ, Wende W, Hien le T, Volkov E, Kubareva E, Oretskaya T, Kokkinidis M, Rompp A, Spengler B, Pingoud A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909444107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Breurken M, Lempens EH, Merkx M. Chembiochem. 2010;11:1665. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cabantous S, Waldo GS. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:45. doi: 10.1038/nmeth932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cabantous S, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:102. doi: 10.1038/nbt1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chun W, Waldo GS, Johnson GV. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2529. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ormo M, Cubitt AB, Kallio K, Gross LA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ. Science. 1996;273 doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bae SJ, Sturtevant JM. Biophys. Chen. 1995;55:247. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(94)00157-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Betzel C, Dauter Z, Genov N, Lamzin V, Navaza J, Schnebli HP, Visanji M, Wilson KS. FEBS Lett. 1993;317:185. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smith BD, Raines RT. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2008;21:289. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Denmeade SR, Lou W, Lovgren J, Malm J, Lilja H, Isaacs JT. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hyberts SG, Goldberg MS, Havel TF, Wagner G. Protein Sci. 1992;1:736. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Magliery TJ, Wilson CG, Pan W, Mishler D, Ghosh I, Hamilton AD, Regan L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:146. doi: 10.1021/ja046699g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Beck ZQ, Hervio L, Dawson PE, Elder JH, Madison EL. Virology. 2000;274:391. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tewari M, Quan LT, O’Rourke K, Desnoyers S, Zeng Z, Beidler DR, Poirier GG, Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. Cell. 1995;81:801. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hu H, Clarkson MW, Hermans J, Lee AL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13856. doi: 10.1021/bi035015z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Shetty BV, Kosa MB, Khalil DA, Webber S. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:110. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chang JY. Biochem J. 1986;240:797. doi: 10.1042/bj2400797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Methods. 1999;17:313. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stennicke HR, Renatus M, Meldal M, Salvesen GS. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 2):563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Heim R, Tsien RY. Curr Biol. 1996;6:178. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shu X, Royant A, Lin MZ, Aguilera TA, Lev-Ram V, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. Science. 2009;324:804. doi: 10.1126/science.1168683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Turk B. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:785. doi: 10.1038/nrd2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wildes D, Wells JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914495107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Xu X, Gerard AL, Huang BC, Anderson DC, Payan DG, Luo Y. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2034. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.8.2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jones J, Heim R, Hare E, Stack J, Pollok BA. J Biomol Screen. 2000;5:307. doi: 10.1177/108705710000500502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Benkovic SJ, Scott CP. 20020110834 US PATENT APPLICATION. 2002

- [30].Boulware KT, Daugherty PS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511108103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jones CT, Catanese MT, Law LM, Khetani SR, Syder AJ, Ploss A, Oh TS, Schoggins JW, MacDonald MR, Bhatia SN, Rice CM. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:167. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ward WW. 7329506. US Patent. 2008 B2 Dated.

- [33].Kanno A, Yamanaka Y, Hirano H, Umezawa Y, Ozawa T. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:7595. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shekhawat SS, Porter JR, Sriprasad A, Ghosh I. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15284. doi: 10.1021/ja9050857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fan F, Binkowski BF, Butler BL, Stecha PF, Lewis MK, Wood KV. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:346. doi: 10.1021/cb8000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.