Abstract

The periodontal ligament contains progenitor cells; however, their identity and differentiation potential in vivo remain poorly characterized. Previous results have suggested that periodontal tissue progenitors reside in perivascular areas. Therefore, we utilized a lineage-tracing approach to identify and track periodontal progenitor cells from the perivascular region in vivo. We used an alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) promoter-driven and tamoxifen-inducible Cre system (αSMACreERT2) that, in combination with a reporter mouse line (Ai9), permanently labels a cell population, termed ‘SMA9’. To trace the differentiation of SMA9-labeled cells into osteoblasts/cementoblasts, we utilized a Col2.3GFP transgene, while expression of Scleraxis-GFP was used to follow differentiation into periodontal ligament fibroblasts during normal tissue formation and remodeling following injury. In uninjured three-week-old SMA9 mice, tamoxifen labeled a small population of cells in the periodontal ligament that expanded over time, particularly in the apical region of the root. By 17 days and 7 weeks after labeling, some SMA9-labeled cells expressed markers indicating differentiation into mature lineages, including cementocytes. Following injury, SMA9 cells expanded, and differentiated into cementoblasts, osteoblasts, and periodontal ligament fibroblasts. SMA9-labeled cells represent a source of progenitors that can give rise to mature osteoblasts, cementoblasts, and fibroblasts within the periodontium.

Keywords: periodontal ligament, cementoblasts, GFP, α-smooth muscle actin, scleraxis, Cre recombinase

Introduction

Periodontal disease affects up to 70% of Americans and is the major cause of tooth loss after the age of 65 yrs (Eke et al., 2012). The affected tissues comprise all structures of the periodontium, including periodontal ligament (PDL), cementum, and bone, and their cellular elements: PDL fibroblasts, cementoblasts, and osteoblasts (Foster and Somerman, 2005). Current regenerative strategies involving bone grafts and guided tissue regeneration are not optimal because of morbidity associated with the donor site and immunoreactivity.

It has been postulated that the PDL contains a progenitor population that can differentiate into cementoblasts, osteoblasts, and PDL fibroblasts (Gould et al., 1980; Foster et al., 2007). These progenitors exhibit many stem-cell-like features, including small size, responsiveness to stimulating factors, slow cycle time (McCulloch, 1985; Mrozik et al., 2010), and the ability to generate multiple mesenchymal lineages (Seo et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2005; San Miguel et al., 2010). However, it has not been possible to identify and isolate this population of progenitors. Characterization of progenitor cells within the periodontium is crucial for understanding the processes involved in the remodeling and regeneration of periodontal tissues. These progenitors could potentially be used to promote the regeneration of tissues affected by periodontal disease.

Previous investigations have identified progenitor cell populations within the periodontium expressing mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) markers such as STRO-1, CD146, and CD44 (Leonardi et al., 2000, 2006; Chen et al., 2006; Kemoun et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2009). We have identified a periodontal progenitor population expressing alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) that resides in perivascular areas of PDL in the apical region (San Miguel et al., 2010). We also demonstrated αSMA expression in perivascular cells in bone marrow, adipose tissue, the periosteum, and cranial sutures, areas rich with progenitor cells (Kalajzic et al., 2008; Zannettino et al., 2008 Grcevic et al., 2012). The limitation of previous studies that identified periodontal tissue progenitors is their reliance on in vitro assays to determine lineage potential.

The goal of our study was to examine the ability of αSMA-expressing cells residing within periodontal tissues to generate mature lineages of the periodontium in vivo. We used murine models harboring real-time visual transgenes and Cre/loxP technology as a powerful way of identifying periodontal progenitors and their progeny (Grcevic et al., 2012).

Materials & Methods

Transgenic Mice

The αSMA-GFP and αSMACreERT2 mice have been previously described (Kalajzic et al., 2008; Grcevic et al., 2012). Mice in which a 2.3-kb promoter fragment of type I collagen drives GFP (Col2.3-GFP) were used to identify osteoblasts and cementoblasts (Kalajzic et al., 2002; Braut et al., 2003). Mice in which the Scleraxis promoter drives GFP (Scx-GFP) were utilized to identify PDL fibroblasts (Pryce et al., 2007; Inoue et al., 2012). αSMACreERT2 mice were crossed with Cre reporter mice (Ai9) (Madisen et al., 2010) (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) to generate αSMACreERT2/Ai9 mice (SMA9). To trace differentiation of SMA9 cells, we generated triple transgenic mice SMA9/Col2.3-GFP and SMA9/Scx-GFP. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee.

Lineage Tracing

Three- to four-week-old mice were treated with tamoxifen at 75 μg/g of body weight. Mice were treated on 2 consecutive days and sacrificed 2 days, 17 days, and 6 to 7 wks following tamoxifen administration. Results were evaluated in 4 or 5 jaws per time-point, and genotype.

PDL Injury Model

Two-month-old transgenic mice were treated with tamoxifen 48 and 24 hrs before injury. Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (87 mg/kg) and xylazine (13 mg/kg). Injury was induced on the lingual root of the first maxillary molar by the insertion of a 0.1-mm blade between the gingiva and alveolar bone (Appendix Fig. 1). This injury results in damage to the PDL and associated cementum and bone. Mice were sacrificed on day 7 and day 28 after injury, and maxillary arches were isolated and processed for histological and epifluorescence analysis. Results were evaluated in 4 to 6 jaws per time-point and by genotype.

Histology

Jaws were fixed for 3 days in 10% formalin at 4°C, decalcified in 14% EDTA for 3 wks, placed in 30% sucrose overnight, and embedded in cryomatrix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sections measuring 5 μm were obtained by means of a cryostat (Leica, Wetzler, Germany) and tape transfer system (Section-lab, Hiroshima, Japan). Sections were examined with an Observer.Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA), and images were obtained with appropriate filter cubes (Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT, USA). To obtain a full-size image of teeth, we scanned the sections, then stitched them into a composite. Following fluorescent imaging, coverslips were removed, and sections were stained with hematoxylin and re-imaged.

Results

Visual Promoter-Reporter Transgenes Identify Populations of Cells within Periodontium

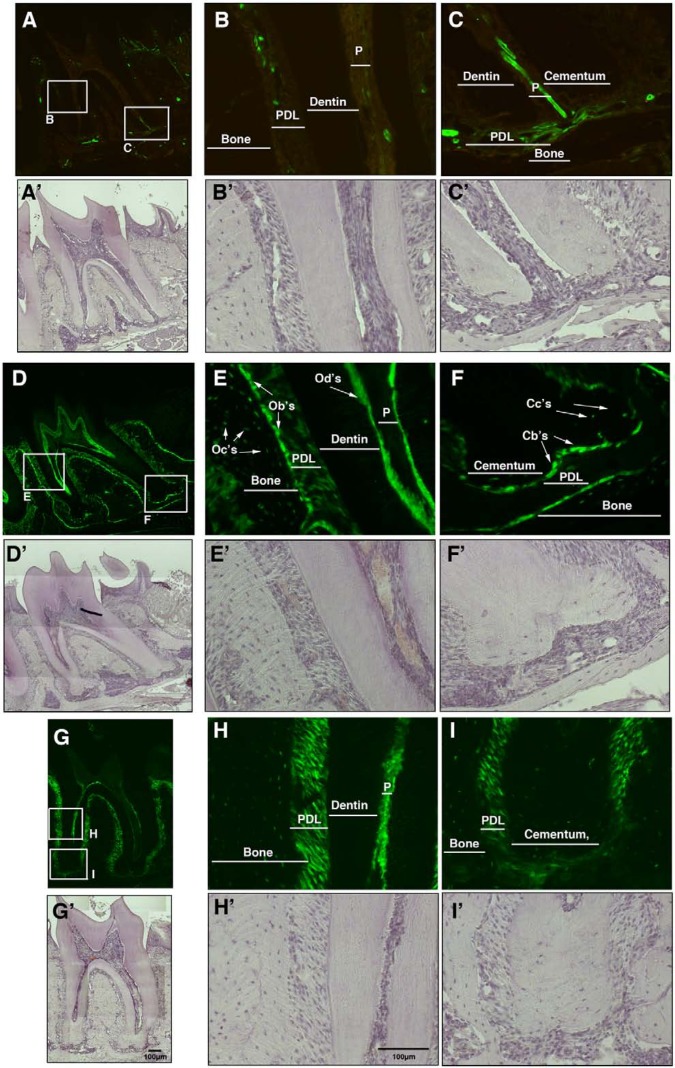

To validate the transgenes used in this study to identify progenitors and mature cells, we examined GFP expression in the jaws of adult αSMA-GFP, Col2.3-GFP, and Scx-GFP transgenic mice. We postulated that αSMA could be used as a marker of periodontal progenitor cells. Consistent with our previous studies (San Miguel et al., 2010), αSMA-GFP expression was detected in cells associated with the microvasculature within the alveolar bone, the horizontal and oblique PDL fibers, and the area rich in vasculature within the apical fibers of the PDL (Figs. 1A-1C). Immunostaining has shown that these cells are distinct from CD31+ endothelial cells (San Miguel et al., 2010), but they generally express high levels of pericyte marker PDGFRβ (Appendix Fig. 2). Flow cytometry of isolated αSMA-GFP+ cells indicated that they do not express hematopoietic or endothelial lineage markers (Appendix Fig. 3), but a subset of these cells expresses MSC markers such as Sca1, CD90, and CD105 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Expression of the αSMA-GFP, Col2.3-GFP, and Scx-GFP transgenes within the periodontium. Sections of the second mandibular molar from six-week-old transgenic mice were evaluated for GFP expression. (A-C) αSMA-GFP-positive cells were detected in the PDL in cells in close association with vasculature within the cervical (B-B′) and apical (C-C′) regions. (D-F) Col2.3-GFP labeled most mature mesenchymal lineage cells within periodontal tissues, as indicated in high-power images from the cervical (E-E′) and apical regions (F-F′) of the periodontium. (E-E′) Col2.3-GFP expression was detected in osteoblasts (Ob’s), osteocytes (Oc’s), and at a lower level in periodontal fibroblasts in the cervical region. Col2.3-GFP was also strongly expressed in odontoblasts (Od’s) and weakly expressed in dental pulp (P). (F-F′) In the apical region, Col2.3-GFP was expressed in cementoblasts (Cb’s) and cementocytes (Cc’s). (G-I) Scx-GFP expression was detected at strong levels in PDL fibroblasts in both the cervical (H-H′) and apical regions (I-I′) of the tooth. A-I, epifluorescence; A′-I′, hematoxylin staining. Images were taken at 10× (A, D, G) and 20× magnifications (B-C, E-F, H-I). Abbreviations: Cb’s, cementoblasts; Cc’s, cementocytes; Ob’s, osteoblasts; Oc’s, osteocytes; Od’s, odontoblasts; P, pulp; PDL, periodontal ligament.

Col2.3-GFP is a marker of mature osteoblasts, cementoblasts, and odontoblasts (Braut et al., 2003). As expected, positive cells were observed in osteoblasts, osteocytes within bone, cementoblasts on the root surface, and odontoblasts lining the pulp chamber. Col2.3-GFP transgene was expressed at a lower level in dental pulp and in cervical PDL fibroblasts (Figs. 1D-1F). Since Col2.3-GFP does not label all PDL fibroblasts, Scx-GFP was used (Inoue et al., 2012). It was expressed at high levels in PDL fibroblasts within the cervical and periapical regions and in cells of the trans-septal ligament and at lower levels by osteocytes and cementocytes (Figs. 1G-1I).

SMA9 Cells Represent a Population of Periodontal Progenitors

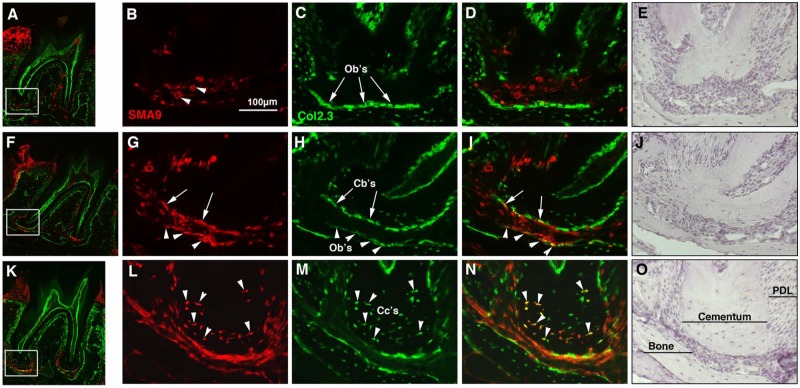

To trace the fate of αSMA-expressing cells in the periodontium, we utilized mice in which the αSMA promoter directs an inducible Cre recombinase (αSMACreERT2) crossed with Ai9 reporter mice that express the red fluorescent protein tdTomato only after Cre recombinase excises a STOP cassette. Once the αSMACreERT2 is activated by tamoxifen, αSMA-expressing cells and their progeny will express the tdTomato reporter gene throughout their lifespan (SMA9+). To detect differentiation of SMA9+ cells into mature cementoblasts and osteoblasts, we crossed SMA9 mice with Col2.3-GFP mice.

Two days after tamoxifen administration to 3- to 4-week-old SMA9/Col2.3-GFP mice, SMA9+ cells were observed within the gingiva and in perivascular areas of PDL in the periapical region (Figs. 2A-2E). At this time-point, we did not detect co-expression of Col2.3-GFP in SMA9+ cells. Histology of the periodontium 17 days after labeling showed expansion of SMA9+ cells in the PDL and co-expression of Col2.3-GFP in SMA9+ cells on the surface of the root and adjacent alveolar bone in the apical region (Figs. 2F-2J). Seven wks after labeling, there were still SMA9+ cells within the PDL and surrounding tissues, and the majority of these cells co-expressed Col2.3-GFP transgene (Figs. 2K-2O). SMA9/Col2.3-GFP cells were also observed in cellular cementum in the apical region of the root. Cellular cementum was largely absent in 3- to 4-week-old mice but formed during the period of lineage tracing. Analysis of our data showed that SMA9+ cells were capable of differentiation into osteoblasts, cementoblasts, and cementocytes within the periodontium during normal growth and remodeling (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Lineage tracing of SMA9+ cells during cementum formation in SMA9/Col2.3-GFP transgenic mice. Three- to four-week-old SMA9/Col2.3-GFP mice were injected with tamoxifen on 2 consecutive days and sacrificed at days 2 (A-E) and 17 (F-J) and 7 wks (K-O) after induction of Cre activity. Expression of SMA9 transgene was evaluated in the periodontium of second mandibular molars. (A-E) At day 2, a few SMA9+ cells were detected within the apical region of the PDL that are associated with microvasculature (indicated by arrowheads in B). Col2.3-GFP was not expressed in SMA9+ cells (indicated by arrows in C). (F-J) The SMA9 population expanded by day 17 (F), particularly in the apical region of the root. Dual-labeled osteoblasts were detected in adjacent alveolar bone (G-I, indicated by arrowheads) and cementoblasts lining cementum (indicated by arrows). (K-O) At week 7, in addition to expansion within the PDL, SMA9 expression was detected in cementoblasts and in cementocytes within cellular cementum (indicated by arrowheads). Dual fluorescent images represent a scanned 10x image of a whole tooth (A, F, K). High-magnification images (20x) of the apical region of the root are shown in the red channel for SMA9+ cells (B, G, L), the green channel for Col2.3-GFP+ cells (C, H, M), overlaid images (D, I, N) and images stained with hematoxylin (E, J, O). Representative images are shown (n = 4-5 per time-point). Abbreviations: P, pulp; PDL, periodontal ligament; Cb’s, cementoblasts; Cc’s, cementocytes.

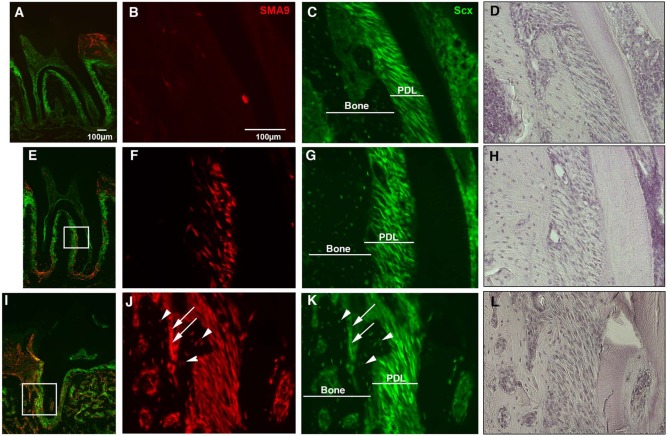

To evaluate differentiation of SMA9+ progenitor cells into PDL fibroblasts, we performed similar lineage tracing in SMA9/Scx-GFP mice (Figs. 3A-3H). Similar to Figs. 2A-2E, a few SMA9+ cells were detected at day 2 within the PDL in the periapical region (Figs. 3A-3D), and these cells did not co-express Scx-GFP, indicating that they are not mature PDL fibroblasts. Seven wks after labeling, SMA9+ cells had expanded within both the cervical and apical areas of the PDL, and most SMA9+ cells co-expressed Scx-GFP, indicating a PDL fibroblast phenotype (Figs. 3E-3H).

Figure 3.

Differentiation of SMA9+ cells into Scx-GFP+ PDL fibroblasts. The Scx-GFP transgene was utilized to detect transition of αSMA-labeled cells into mature PDL fibroblasts. Three- to four-week-old SMA9/Scx-GFP mice were injected with tamoxifen, and histological analysis of the second mandibular molar was completed at day 2 and week 7 after treatment. At day 2 (A-D), a small population of SMA9+ cells was detected within PDL areas. Expansion and differentiation of the SMA9+ population was observed by 7 wks (E-H), with numerous SMA9+ cells present within the PDL area and co-expressing Scx-GFP. Histology of tamoxifen-treated SMA9/Scx-GFP mice 28 days after PDL injury at the first maxillary molar is shown (I-L). Following injury to the PDL area, SMA9+ cells could be observed within the newly formed bone and within the majority of the Scx-GFP-expressing PDL fibroblasts. A population of osteocytes (J-K, arrowheads) and osteoblasts (J-K, arrows) co-expressed SMA9 and Scx-GFP (arrows). In epifluorescent images (A-C, E-G, I-K), green labels Scx-GFP+ cells, and red labels expression of the SMA9 transgene. Hematoxylin staining is also shown (D, H, L). Representative images are shown (n = 4 per time-point). Images were taken at magnifications of 10× (A, E, J) and 20× (B-D, F-H, J-L).

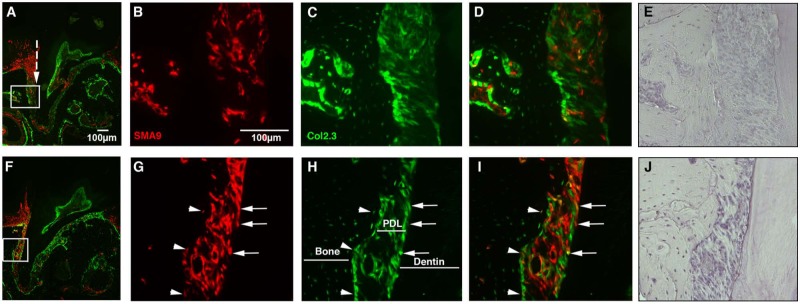

Effects of Periodontal Injury on Expansion and Differentiation of SMA9+ Progenitors

We developed a periodontal injury model to examine the regenerative potential of SMA9+ cells in the PDL during healing (Appendix Fig. 1). Seven days after injury, there was notable expansion of the SMA9+ population within gingiva and in perivascular areas of PDL in the periapical region of the injured root (Figs. 4A-4E) as compared with the uninjured root (Appendix Fig. 4). In addition, at this time, SMA9+ cells in the gingiva extended more apically (Figs. 4A-4E) as compared with the uninjured root. Co-expression of Col2.3-GFP was not detected in SMA9+ cells at this time-point (Figs. 4B-4E). Four wks after injury (Figs. 4F-4J), co-expression of Col2.3-GFP was detected in SMA9+ cells, including osteoblasts lining the adjacent new bone deposited after the injury, and cementoblasts. There were also numerous Col2.3-GFP+/SMA9+ cells in the PDL space that displayed many features characteristic of PDL fibroblasts, including spindle shape and parallel orientation.

Figure 4.

Injury-induced repair of periodontal ligament involves SMA9+ cells. The regenerative capacity of SMA9+ cells was examined 7 days (A-E) and 4 wks (F-J) following injury to the periodontium of the first maxillary molar. Labeling of SMA9+ cells was induced by tamoxifen given to the two-month-old SMA9/Col2.3-GFP transgenic mice 24 and 48 hrs before injury. (A-E) Seven days after injury, numerous SMA9+ cells were observed within the injured periodontium (A, injury site indicated by broken line). At day 7 after injury, the majority of the SMA9-expressing cells do not express Col2.3-GFP (B-D). At 4 wks after injury, we observed a dramatic expansion of SMA9-labeled cells within the PDL, and many of these cells co-express Col2.3-GFP (G-I, osteoblasts/osteocytes [see arrowheads]; cementoblasts [see arrows]), indicating differentiation of injury-induced SMA9 periodontal progenitors. Hematoxylin staining is also shown (E, J). Representative images are shown (n = 6 mice per time point). Images were taken at magnifications of 10× (A, F) and 20× (B-E, G-J).

The contributions of SMA9+ cells to PDL fibroblasts after injury were confirmed in SMA9/Scx-GFP mice (Figs. 3I-3L). We observed new bone formation from SMA9+ cells, indicated by the presence of numerous SMA9+ osteocytes and osteoblasts (Figs. 3J, 3K). In addition, SMA9+ cells expanded and differentiated into numerous cells with fibroblastic shape within the PDL co-expressing Scx-GFP, indicative of a PDL fibroblast phenotype (Figs. 3I-3L). Our observations in the injured periodontium provide evidence of contributions of SMA9+ cells to PDL fibroblasts (identified by morphology and expression of Col2.3-GFP and Scx-GFP), osteoblasts, and cementoblasts (identified by location and expression of Col2.3-GFP), indicating that αSMA-expressing cells contribute to the regeneration of the periodontium.

Discussion

Current treatment of advanced periodontal disease consists of conservative or surgical approaches aimed at removing the affected inflamed tissue and bacterial plaque, which then stimulates regenerative processes. Stem cell–based treatments to regenerate periodontium are a promising therapeutic approach for this condition (Krebsbach and Robey, 2002; Lin et al., 2008). Periodontal tissue contains a resident population of cells with regenerative potential. Better understanding of the identity of these cells and the mechanisms involved in their differentiation into mature cell types is an essential step toward their therapeutic utilization (Ivanovski et al., 2006). Seo et al. (2004) found that human PDL-derived cell cultures expressed MSC markers STRO-1 and CD146 and were capable of differentiating into adipocytes or mineralizing cells in vitro. When transplanted into immunocompromised mice, PDL stem cells form cementum/PDL-like structures (Seo et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2006). It has been suggested that perivascular cell populations contain progenitors for cementoblasts, osteoblasts, and PDL fibroblasts, but this has never been confirmed in vivo (Iwasaki et al., 2013). A recent study utilized expression of osterix to identify cementoblasts and their progenitors in vivo (Cao et al., 2012). Osterix is expressed in cells within the PDL in proximity to the cementoblast layer, indicative of their pre-cementogenic phenotype. However, osterix expression in both progenitors and mature cells (cementoblasts and osteoblasts) precludes the use of the osterix-Cre models for lineage-tracing studies in adult animals.

We have previously utilized αSMA-GFP to identify a population of perivascular cells within the periodontium that show osteogenic potential in vitro (San Miguel et al., 2010). The main disadvantage of the αSMA-GFP model is a decrease in GFP expression during differentiation. Therefore, in this study we used an αSMA promoter-directed inducible Cre recombinase (αSMA-CreERT2) combined with a reporter mouse (Ai9). Cre recombination is regulated by tamoxifen induction, thus avoiding activation during developmental stages and permitting lineage tracing to be performed in adult animals. This approach provided in vivo evidence that the αSMA+ pericyte/myofibroblast cells residing in the PDL have the ability to differentiate into mature cell types within the periodontium during growth and regeneration after injury. This is in line with results (in long bones) indicating that αSMA+ cells in the bone marrow differentiate into osteogenic lineage cells during bone growth, and αSMA+ periosteal cells contribute to osteogenic and chondrogenic elements during fracture healing (Grcevic et al., 2012).

One of the most important considerations in lineage-tracing studies is the methodology used to identify mature cell phenotypes. In this study, we used expression of the Col2.3-GFP transgene, which is characteristic of cementoblasts and osteoblasts, as a marker of mature cells within these lineages. The differentiation of SMA9 cells into cementoblasts and osteoblasts is clearly shown in cells expressing both SMA9 and Col2.3-GFP, providing strong evidence that, in addition to labeling osteogenic progenitors as it does in other tissues, the periodontal SMA9+ population contains progenitors capable of differentiating into cementoblasts/cementocytes (Fig. 2). Differentiation of SMA9 cells into PDL fibroblasts was confirmed in Scx-GFP mice. Scleraxis is a transcription factor, expressed in tendon progenitor populations and mature tendons as well as in PDL fibroblasts (Pryce et al., 2007; Inoue et al., 2012). We did not expect to detect expression of Scx-GFP in osteocytes and cementoblasts, and further studies will be required to establish whether this expression pattern is consistent with the expression of endogenous Scleraxis. However, strong, uniform expression of Scx-GFP in PDL fibroblasts, but not in SMA9+ cells in the PDL soon after labeling, facilitated lineage tracing of SMA9+ cells into PDL fibroblasts.

The contributions of the SMA9+ cells to all mature mesenchymal tissues within the periodontium are more evident following injury to the PDL. In addition, we observed expansion of SMA9+ cells from the gingiva toward the PDL area. Gingival tissue has been postulated to contain a population of MSCs capable of multi-lineage differentiation (Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). With this system, it is difficult to identify the exact source of SMA9+ cells contributing to periodontal regeneration, and it is possible that gingiva-derived SMA9+ cells migrate into the wound and contribute to the healing process, but given that SMA9+ cells are present in the PDL prior to injury, and can contribute to multiple lineages under conditions of normal growth and tissue turnover, it is likely that these cells also play a role in healing. Our previous studies have shown that αSMACre-labeled cells represent a heterogeneous population, and αSMA expression is characteristic of both pericytes and myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts are produced in response to injury, and a subset of the cells labeled after injury is likely to be myofibroblasts. A recent study demonstrated that ADAM12-expressing perivascular cells became myofibroblasts that regulated injury healing, but did not contribute to other mature lineages (Dulauroy et al., 2012). This suggests that αSMA+ pericytes, and not myofibroblasts, are the periodontal progenitors, but further studies are required to clarify this.

In conclusion, αSMACreERT2 labels an endogenous periodontal progenitor population capable of differentiation into mature cell types, including osteoblasts, cementoblasts, and PDL fibroblasts in vivo under normal growth conditions, and after injury. This provides a transgenic model in which to characterize the effects of periodontal disease or injury on mesenchymal progenitor cells and their regenerative potential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ronen Schweitzer for providing Scleraxis-GFP mice.

Footnotes

This work has been supported by the NIH/NIAMS (grant AR055607 to I.K.) and the Croatian Science Foundation (to H.R.).

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Braut A, Kollar EJ, Mina M. (2003). Analysis of the odontogenic and osteogenic potentials of dental pulp in vivo using a Col1a1-2.3-GFP transgene. Int J Dev Biol 47:281-292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Zhang H, Zhou X, Han X, Ren Y, Gao T, et al. (2012). Genetic evidence for the vital function of Osterix in cementogenesis. J Bone Miner Res 27:1080-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Marino V, Gronthos S, Bartold PM. (2006). Location of putative stem cells in human periodontal ligament. J Periodontal Res 41:547-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulauroy S, Di Carlo SE, Langa F, Eberl G, Peduto L. (2012). Lineage tracing and genetic ablation of ADAM12(+) perivascular cells identify a major source of profibrotic cells during acute tissue injury. Nat Med 18:1262-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Thornton-Evans GO, Genco RJ. (2012). Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res 91:914-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster BL, Somerman MJ. (2005). Regenerating the periodontium: is there a magic formula? Orthod Craniofac Res 8:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster BL, Popowics TE, Fong HK, Somerman MJ. (2007). Advances in defining regulators of cementum development and periodontal regeneration. Curr Top Dev Biol 78:47-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TR, Melcher AH, Brunette DM. (1980). Migration and division of progenitor cell populations in periodontal ligament after wounding. J Periodontal Res 15:20-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grcevic D, Pejda S, Matthews BG, Repic D, Wang L, Li H, et al. (2012). In vivo fate mapping identifies mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells 30:187-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Ebisawa K, Itaya T, Sugito T, Yamawaki-Ogata A, Sumita Y, et al. (2012). Effect of GDF-5 and BMP-2 on the expression of tendo/ligamentogenesis-related markers in human PDL-derived cells. Oral Dis 18:206-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovski S, Gronthos S, Shi S, Bartold PM. (2006). Stem cells in the periodontal ligament. Oral Dis 12:358-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K, Komaki M, Yokoyama N, Tanaka Y, Taki A, Kimura Y, et al. (2013). Periodontal ligament stem cells possess the characteristics of pericytes. J Periodontol [Epub ahead of print 12/14/2012] (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalajzic I, Kalajzic Z, Kaliterna M, Gronowicz G, Clark SH, Lichtler AC, et al. (2002). Use of type I collagen green fluorescent protein transgenes to identify subpopulations of cells at different stages of the osteoblast lineage. J Bone Miner Res 17:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalajzic Z, Li H, Wang LP, Jiang X, Lamothe K, Adams DJ, et al. (2008). Use of an alpha-smooth muscle actin GFP reporter to identify an osteoprogenitor population. Bone 43:501-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemoun P, Laurencin-Dalicieux S, Rue J, Vaysse F, Romeas A, Arzate H, et al. (2007). Localization of STRO-1, BMP-2/-3/-7, BMP receptors and phosphorylated Smad-1 during the formation of mouse periodontium. Tissue Cell 39:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebsbach PH, Robey PG. (2002). Dental and skeletal stem cells: potential cellular therapeutics for craniofacial regeneration. J Dent Educ 66:766-773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi R, Lanteri E, Stivala F, Travali S. (2000). Immunolocalization of CD44 adhesion molecules in human periradicular lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 89:480-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi R, Loreto C, Caltabiano R, Caltabiano C. (2006). Immunolocalization of CD44s in human teeth. Acta Histochem 108:425-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin NH, Gronthos S, Bartold PM. (2008). Stem cells and periodontal regeneration. Aust Dent J 53:108-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, et al. (2010). A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 13:133-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch CA. (1985). Progenitor cell populations in the periodontal ligament of mice. Anat Rec 211:258-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrozik K, Gronthos S, Shi S, Bartold PM. (2010). A method to isolate, purify, and characterize human periodontal ligament stem cells. Methods Mol Biol 666:269-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryce BA, Brent AE, Murchison ND, Tabin CJ, Schweitzer R. (2007). Generation of transgenic tendon reporters, ScxGFP and ScxAP, using regulatory elements of the scleraxis gene. Dev Dyn 236:1677-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Miguel SM, Fatahi MR, Li H, Igwe JC, Aguila HL, Kalajzic I. (2010). Defining a visual marker of osteoprogenitor cells within the periodontium. J Periodontal Res 45:60-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, et al. (2004). Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet 364:149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S, Bartold PM, Miura M, Seo BM, Robey PG, Gronthos S. (2005). The efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells to regenerate and repair dental structures. Orthod Craniofac Res 8:191-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Yu M, Yan X, Wen Y, Zeng Q, Yue W, et al. (2011). Gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cell-mediated therapeutic approach for bone tissue regeneration. Stem Cells Dev 20:2093-2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wang W, Kapila Y, Lotz J, Kapila S. (2009). Multiple differentiation capacity of STRO-1+/CD146+ PDL mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev 18:487-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannettino AC, Paton S, Arthur A, Khor F, Itescu S, Gimble JM, et al. (2008). Multipotential human adipose-derived stromal stem cells exhibit a perivascular phenotype in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Physiol 214:413-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QZ, Nguyen AL, Yu WH, Le AD. (2012). Human oral mucosa and gingiva: a unique reservoir for mesenchymal stem cells. J Dent Res 91:1011-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.