Abstract

Behavioral symptoms such as repetitive statements and questions, wandering, and sleep disturbances are a core clinical feature of Alzheimer disease and related dementias, affecting patients and their families. These behaviors have devastating effects. If untreated, they can contribute to more rapid disease progression, earlier nursing home placement, worse quality of life, accelerated functional decline, greater caregiver distress, and higher health care utilization and costs. Patients with dementia are typically not screened for behavioral symptoms in primary care and even when clinically reported, tend to receive ineffective, inappropriate, and fragmented care. Yet, clinicians are often called upon to address behaviors that place the patient or others at risk or which families encounter as problematic. It is important to include on-going systematic screening for behavioral symptoms to facilitate prevention and early treatment as part of standard comprehensive dementia care. When identified, behaviors should be characterized and underlying causes sought in order to derive a treatment plan. Because available pharmacologic treatments used to treat behaviors have modest efficacy at best, are associated with notable risks, and do not address behaviors most distressing for families, nonpharmacologic options are recommended as first-line treatments or if necessary, in parallel with pharmacologic or other treatment options. Nonpharmacologic treatments may include a general approach (caregiver education and training in problem solving, communication and task simplification skills, patient exercise, and/or activity programs), or a targeted approach in which precipitating conditions of a specific behavior are identified and modified (eg, implementing nighttime routines to address sleep disturbances). Using the case of Mr A, we characterize common behavioral symptoms of dementia and describe an assessment strategy for selecting evidence-based nonpharmacologic treatments. We highlight the clinician's important role in facilitating collaboration with specialists and other health care professionals to implement nonpharmacological treatment plans. Substantial evidence shows that nonpharmacologic approaches can yield high levels of patient and caregiver satisfaction, quality of life improvements, and reductions in behavioral symptoms. Although access to nonpharmacologic approaches is currently limited, they should be part of standard dementia care.

The Patient's Story

Mr A is a 93-year-old man who immigrated to the United States from Mexico at 8 years of age. He lives at home with his cousin and primary caregiver, Mr Z. His other family members live in Mexico. He was a military clerical worker in the United States Army and never married or had children. About 13 years ago, Mr A complained of memory problems including forgetting why he walked into a room, or whether he had taken his medications.

An initial examination in 2004 revealed a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 29/30, above the standard cut-off of 24 indicating concern for dementia. However, in the context of memory impairment and a head CT showing significant white matter changes and bilateral and frontotemporal atrophy, Mr A was diagnosed with possible mild cognitive impairment. His physician thought this could be a result of brain vascular disease, although Alzheimer's disease was also a possible etiology.

By 2010, the MMSE declined to 21/30. As laboratory test results indicated no potentially reversible etiology, his course was considered consistent with mild progressive dementia. Mr A was, by now, more reliant on his cousin to take medications and perform instrumental activities (shopping, cooking), although when home alone, he was able to call his cousin at work and perform self-care (dressing, bathing) independently. As the disease progressed, his mood remained positive and he lacked insight into his memory problems. Neuropsychological testing revealed major impairments in executive function, verbal/spatial memory, recall, and language, with mild word finding difficulty. He also has multiple co-morbidities (hypertension, chronic hypokalemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, lower extremity peripheral neuropathy, coronary artery disease), receives vitamin B12 injections monthly and takes 13 medications.

Initially, memory-related problems were most bothersome to Mr A, whereas repetitive questioning was troublesome to his caregiver, Mr Z. In 2010, significant neuropsychiatric symptoms and behaviors (referred to as behavioral symptoms in this article) that were problematic to the caregiver emerged. The initial chief complaint to the physician, Dr J, was Mr A “hearing voices at night” and not letting Mr Z sleep. In addition to night-time hallucinations, Mr A experienced other behaviors including napping excessively during the day, withdrawing from activity, restlessness at night and waking his caregiver, and displaying feelings of insecurity and loneliness.

With dementia progression, Mr Z assumed more hands-on care responsibilities juggling full-time employment, sleep deprivation, and a limited support network. A concern to Dr J was Mr A′s reduced decision-making capacity and questionable ability to stay at home alone safely. This concern was precipitated by an incident in 2011.. Mr A, upon developing a nosebleed, left his home to find help, became lost, and fell. Neighbors called Mr Z and paramedics to take him to an emergency department.

A Care of the Aging Patient series editor interviewed Mr A, Mr Z, and Dr J in 2011.

Perspectives

Mr A: (Asked about his health)…My heart?…I'm very well for my age… I think you have noticed I'm not hearing well … I'm mostly by myself. [Mr Z] goes to work during the daytime. I don't see him … I just get lonesome.

Mr Z: Well, it's not easy. I have to be very patient and sometimes I'm not patient enough. …what I don't like is during the night when he gets up and turns on the light in my room and he wants to know if I'm there.

Dr J: The patient declined in his cognitive abilities… in evenings, he was very restless…he wasn't sleeping and was turning on lights and talking loudly…the caregiver was concerned because he appeared to be talking to people….

Mr A′s story exemplifies a common scenario confronted by the 5.4 million people in the United States aging with dementia and complex comorbidities. Dementia-associated behavioral symptoms and their potentially devastating consequences worsen quality of life for patients and their over 15 million family caregivers.1,2 Considered a pandemic, dementia is projected to afflict over 115.4 million new patients worldwide and 16 million in the United States by 2050.3 Most patients are cared for at home by family throughout the disease course.4 As with many patients with dementia, Mr A developed behavioral symptoms (Table 1) that changed with disease progression and required ongoing interventions by his family and physician to manage.

Table 1. Potential Nonpharmacologic Strategies to Manage Mr. A′s Targeted Behaviors.

| Presenting Behavior | Select Nonpharmacologic Strategies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviors at mild cognitive impairment stage | |||

| Forgetful about medication taking |

|

||

| General forgetfulness; disorientation to time |

|

||

| Behaviors at moderate dementia stage | |||

| Hearing voices or noises (especially at night) |

|

||

| Nighttime waking, turns on lights, wakes caregiver, feels insecure at night |

|

||

| Repetitive questioning |

|

||

| Leaves home and wanders outside |

|

||

| Unable to respond to emergency (difficulty calling for help) |

|

||

| Falls and poor balance |

|

||

| Memory-related such as disorientation, confusion recognizing objects |

|

||

| Restless at night |

|

||

Note: Bold refers to strategies discussed, considered or implemented by Mr. A′s physician and caregiver. Strategies listed are potential approaches used in randomized clinical trials but are not exhaustive. A suggested strategy may be effective for one patient but not another. Any one strategy may not have been evaluated for effectiveness for use with all dementia patients with the same presenting behavior. Strategies listed above should only be considered once thorough assessment (description and decoding – Figure 1, steps 2 and 3) has been completed.

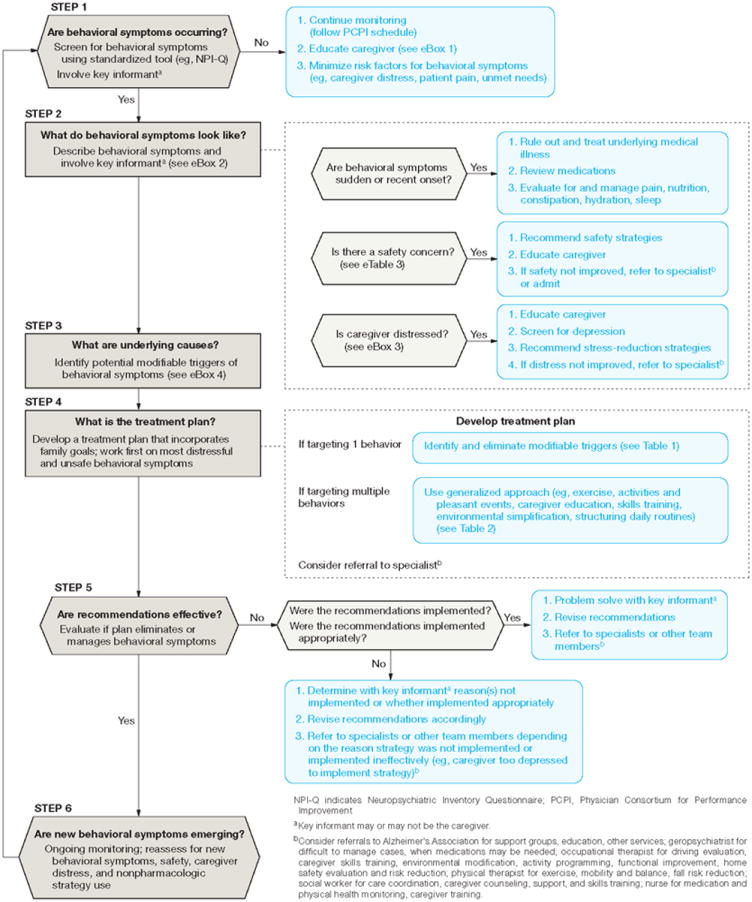

Using Mr A′s story, we describe common behaviors associated with dementia and the role of nonpharmacologic treatments including a review of existing evidence. We present a framework for integrating evidence-based nonpharmacologic treatments in dementia care involving 6 interrelated steps: routine screening for prevention or early detection of behaviors, describing presenting behaviors, identifying underlying causes, developing nonpharmacologic treatment plans, evaluating if nonpharmacologic recommendations are effective, and conducting on-going monitoring of behaviors and nonpharmacologic strategy use (Figure 1). This framework offers primary care doctors a way to effectively integrate nonpharmacologic approaches into their daily practice.

Figure 1. Screening, identifying, and Manging Behavioral Symptoms in Patients With Dementia.

Methods

We conducted PubMed searches to identify studies in peer-reviewed journals published from 1992 to 2012 concerning nonpharmacologic behavioral management, focused primarily on community-dwelling dementia patients. Search terms included: nonpharmacologic interventions, nonpharmacologic strategies; behavioral symptoms in dementia; neuropsychiatric symptoms, treatment for neuropsychiatric behaviors, and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Studies were limited to the English language. We also searched for recent published systematic reviews, meta-analyses, Cochrane reviews, and home and community-based randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments from 2001 to the present with behavioral symptoms as an outcome. Additionally, we searched for published dementia care guidelines that included treatment for behaviors in PubMed, websites of medical organizations, and reviewed the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI) 2011 Dementia Performance Measurement Set. Our data synthesis and recommendations were informed by existing evidence, our clinical practices and trial experience testing nonpharmacologic approaches.

Definition, Etiology and Prevalence of Behavioral Symptoms

A heterogeneous group of non-cognitive manifestations occurring in patients with dementia, behavioral symptoms represent one of the most significant clinical dimensions of the disease. Various terms refer to these behaviors. Neuropsychiatric symptoms refer broadly to the cognitive, behavioral and psychological sequelae of brain diseases,5 and more narrowly to behavioral and psychological sequelae only,6 also known as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. In this article, we use the term behavioral symptoms both to describe psychiatric manifestations of dementia (depression, apathy, agitation, delusions, hallucinations), and common behaviors that are often challenging to families (repetitive vocalizations, shadowing, resistance to care, wandering, argumentativeness).

Behavioral symptoms tend to occur in clusters or syndromes (depression, psychosis, agitation, aggression, apathy, sleep disturbances, executive dysfunction).2,7 As cognitive impairment alone does not explain the etiology of behaviors, further study is underway to understand phenotype and pathogenesis. They are now considered central consequences of the diffuse brain damage that brings about cognitive and functional decline in dementia. As dementia patients experience heightened vulnerability to their environment, behavioral symptoms may result from the confluence of multiple, some potentially modifiable, interacting factors including internal (e.g., pain, fear) or external (e.g., over-stimulating environment, complex caregiver communications) features.6,7

Although behavioral symptoms occur at any disease stage, some appear more often than others at different stages. Depression and apathy are frequently observed in mild cognitive impairment and early stage Alzheimer's disease, and may increase in frequency as dementia worsens. Delusions, hallucinations, and aggression are more common in moderate to severe stages.2 Apathy, a common family complaint, is among the most frequent and persistent behavioral symptom across all dementia stages. Defined as diminished motivation for at least 4 weeks, it is accompanied by any 2 of the following: reduced goal-directed behavior, goal-directed cognitive activity, and emotions.2 Agitation, another chronic and persistent problem to families , refers to a syndrome involving emotional distress, excessive psychomotor activity, wandering, aggressive behaviors,8 irritability, disinhibition, and/or vocally disruptive behaviours.6,9 It occurs at all levels of dementia severity, but particularly in middle to later stages (e.g., MMSE <20).10-13

Behavioral symptoms are nearly universal in dementia regardless of underlying etiology.2,8,13-16 However, dementia due to certain etiologies may have higher rates of particular behavioral symptoms. Depression is most common in vascular dementia; hallucinations are more frequent in disseminated Lewy body disease than Alzheimer's disease; and Frontotemporal dementia is often characterized by executive control loss, evidenced by such behaviors as disinhibition, wandering, social inappropriateness, and apathy.17-19

Behavioral symptoms frequently co-occur, and can be a “moving target” over time. For example, wandering may be followed by delusions, which may be replaced by aggression and so on. Families frequently manage multiple behavioral symptoms simultaneously as with Mr A. While fluctuations in frequency and severity occur, behaviors tend to endure, with most persisting for at least 6 months if untreated.10-12,14,20,21

Consequences of Behavioral Symptoms

Consequences of behaviors are more harmful than those attributable to cognitive decline such as forgetfulness and memory loss, and should not be underestimated.6,15,22,23 Behavioral symptoms can be extremely stressful to caregivers, most of whom have little or no formal training in addressing the unique challenges symptoms usually present. Adding to complexity, persons with dementia, as reflected in Mr A, typically have limited insight concerning their behaviors or repercussions for their caregivers, although reasons for anosognosia differ by dementia type.

Behavioral symptoms heighten patient risk of engagement in dangerous activities, hasten disease progression, and are associated with restraint use, nursing home placement, and psychiatric admissions.8,24-28 Depression, delusions, agitation, hallucinations and caregiver distress are in particular associated with nursing home placement.29,30 In addition to leading to patient suffering, managing behaviors, such as Mr A′s sleep disturbances, wandering, repetitive vocalizations, or other common symptoms (restlessness, anxiousness, overactivity, resisting or refusing care), are the most problematic and distressing aspect of providing care.2,23,31,32 Caregivers of patients with behavioral symptoms are more distressed and depressed than those not managing behaviors.33 Managing behavioral symptoms is one of the most costly aspects of care provision, associated with increased health utilization, direct care costs, and family time spent in daily oversight, as with Mr A and Mr Z.34,35

What are Nonpharmacologic Approaches?

Typical efforts to manage behaviors involve pharmacologic treatments (specifically off label use of atypical antipsychotics), yet these show only modest improvements or no benefits compared with placebo,36-38 and evidence of adverse effects, including heightened risk for mortality.39,40 This has resulted in FDA warnings and an increased interest in nonpharmacologic strategies.

Nonpharmacologic treatments, defined for what they are not (not medications), refer to a broad spectrum of approaches involving some action with the patient and/or their physical and social environment. They can be broadly categorized as generalized (behavior non-specific such as caregiver education and support), or targeted (behavior-specific such as eliminating conditions contributing to a specified behavior). Either approach may directly involve the patient (e.g., exercise) and/or work through another agent–typically the caregiver (e.g., use of communication techniques) or physical environment (e.g., soothing music). Nonpharmacologic approaches conceptualize behavioral symptoms as expressions of unmet needs (e.g., repetitive vocalizations for auditory stimulation); inadvertently reinforced behavior in response to environmental triggers (e.g., patient learns screaming attracts increased attention); and/or consequences of a mismatch between the environment and patients' abilities to process and act upon cues, expectations and demands.41 Approaches may involve modifying patient and/or caregiver cognitions, behaviors, environments, or precipitating events contributing to behaviors or instructing in compensatory strategy use to reduce the patient's increased vulnerability to their environment.

Treatment goals of nonpharmacologic approaches include prevention, management, reduction, or elimination of behavioral occurrences (frequency, severity); reduction of caregiver distress; and/or prevention of adverse consequences (harm to caregiver or patient). Guidelines from medical organizations and working groups recommend nonpharmacologic approaches as the preferred first-line treatment, except in emergency situations where behaviors lead to imminent danger to patient or caregiver, and/or which require hospitalization.42-48 Emerging evidence coupled with practical know-how supports their use as part of standard, comprehensive dementia care.

Integrating Nonpharmacologic Approaches into Dementia Care

Figure 1 displays a decision-making approach involving 6 progressive, highly interrelated and often co-occurring steps for managing behavioral symptoms nonpharmacologically.

Screen for and Prevent Behaviors (Figure 1–Step1)

Dr J: I would follow his Mini-Mental State Exam once a year. …I mostly asked about his functioning. Initially, he would come into the clinic alone …then it was his caregiver and I would ask both: “What's a normal day for you, how are things going? Any problems, any disruptive behaviors, any concerns?”

The initial step is assuming a preventive stance by conducting on-going systematic screening for behaviors and implementing preventive actions.42 By doing so, behaviors are less likely to occur and can be identified early and treated immediately, leading to harm avoidance and better management.

There is no widely agreed upon standard for screening behavioral symptoms. Behaviors are typically brought to a physician's attention by a concerned caregiver or other healthcare provider after their occurrences. The PCP's I Dementia Performance Measurement Set suggests that screening occur proactively and at minimum, yearly, using a reliable and validated instrument (e.g., Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), its clinician (NPI-C) or shortened versions (NPI-Q).42,49,50

Based on screening, when behaviors are not present, critical preventive measures may include counseling caregivers about: (1) dementia, behavioral symptoms and resources (see Resource List); (2) the importance of early detection and physician notification; (3) patients' need for adequate stimulation and structured daily routines; and (3) taking care of themselves (Box 1). As behavioral risk factors include caregiver distress, patient pain, sleep disturbance, inadequate nutrition, infection or other acute medical illnesses,8,51,52 proactively evaluating for their presence and addressing them is equally important.

In Mr A's case, early detection of his nocturnal hallucinations and sleep disturbances by using a behavioral symptom checklist with the caregiver at each visit may have identified these behaviors when they first emerged so they could have been managed immediately. Providing Mr Z early on with targeted nonpharmacologic sleep hygiene strategies (eliminating caffeine by afternoon, establishing structured nighttime routines) may have prevented caregiver exhaustion. Also, early and on-going detection of Mr A′s declining abilities and providing caregiver education about risks for Mr A staying home alone may have prevented his wandering and emergency department visit.

Describe Presenting Behaviors (Figure 1–Step 2)

Mr Z: He would hear sounds…he would call me (at night at home) and ask me if I heard a sound. I told him there was no sound and maybe he was hearing something…That's what I mentioned to Dr. J.”

When behaviors are present, clinicians should proceed with a more formal assessment to describe and differentiate symptoms. This involves interviewing patient and caregiver to characterize behavior(s) and the circumstances of occurrences. Differentiating behavioral symptoms is important. For example, agitation encompasses varied behaviors and may involve physical (hitting, pacing, biting, pushing), verbal (threats, screaming, attention-getting) and/or passive (withdrawal, handwringing, blank stare) attributes that should be delineated to derive specific treatment approaches.

The clinician needs to consider the patient's perspective and what happened according to him/her. However, with disease progression, the patient may be unable to accurately report or remember behaviors or will not fully comprehend risks for his/her safety; thus caregiver involvement becomes essential. (Box 2 provides questions for caregivers to help characterize behaviors.

When describing behaviors, two areas of immediate significance for triaging and developing a treatment plan are safety and level of caregiver distress.52 Box 3 lists common safety concerns contributing to or triggered by behavioral symptoms. Safety concerns will depend upon the patient's cognitive functioning and living situation: as patients become more impaired, they need more supervision to remain safe, as Mr A illustrates. Referral to an occupational therapist or other qualified professional for a comprehensive home safety evaluation would be appropriate.53,54

Safety concerns for Mr A included being home alone while the caregiver worked, his inability to respond effectively to emergency situations, and lack of caregiver follow-through with obtaining a safety alert necklace. While Mr A′s complaint of night-time noises did not at first appear to endanger the patient or caregiver, Mr Z′s lack of sleep put him at risk for indirect health concerns (e.g., sleep deprivation leading to poor health or accidents) and poor work performance. As safety became an increasing concern, Dr J spent more clinical time educating the caregiver as to Mr A′s declining capabilities and increasing need for daily oversight, and identifying alternatives to him remaining at home alone.

Also of importance is determining the caregiver's burden level to evaluate the urgency of modifying behavior(s).55 Caregivers may consider one behavior versus another as more distressing to them. In some cases, caregivers may experience a behavioral symptom “personally”, feeling that the patient is “doing this on purpose to bother them.” Box 4 provides questions to help discern caregiver distress. A depressed caregiver can benefit from referral to a psychiatrist or psychologist for evaluation and counseling, psychotherapy or anti-depressant medication.

Identify Underlying Causes (Figure 1–Step 3)

Dr J: Any time someone comes to me with …a change in behavior, I …hope it wasn't something I did. I look at the medications. Basically, I want to make sure that the patient is not delirious. Does the patient have a urinary tract infection or something that is making him delirious or a medication change?

Step 3 involves identifying possible causes for identified behaviors. Potential causes may be patient-related, caregiver-related or environment-related (Box 5). As Dr J indicates, her immediate concern was whether patient-related factors (medical illnesses, pain, medications), were contributors, particularly important with acute or subacute behavioral onset. Dr J ruled out medical conditions (pain, infection, medications), determined that Mr A was not depressed, and discerned that hearing might be an issue as hearing loss is a potential risk factor for developing delusions or hallucinations in older adults.

Dr J: The caregiver has done an amazing job…. he's able to answer the patient calmly when he's repeating things. …the disruption in sleep and auditory hallucinations …set the family on edge and the caregiver was just overwhelmed.

The clinician should also observe the caregiver's coping and communication styles, closeness to patient, and availability of support (Box 5). Negative communications (yelling, harsh tone, criticizing) are associated with increased patient agitation; dysfunctional (e.g., problem will go away if ignored) versus problem-solving coping (e.g., proactive, task-focused) is associated with poorer patient outcomes; whereas a close relationship with the patient is associated with better patient outcomes.56 Cultural expectations and values can also influence care decisions. In Mr A′s case, most family members lived in Mexico. His cousin willingly assumed care responsibilities but had limited local support. As he needed to work, he was becoming distressed.

Dr J: … state funding for adult day [services], things that could help [Mr A] be safer and which he would really enjoy, has been cut….

Mr A′s story highlights how living situations impact nonpharmacologic treatment decisions. Financial constraints may compromise use of nonpharmacologic approaches or contribute to caregiver burden. As financial strain and caregiver burden are predictive of nursing home placement,57 recognizing these and other contextual factors, as exemplified by Dr J, and working with families to address them, is part of a nonpharmacologic approach.

An under-examined contributor to behaviors is the home environment such as the presence of excessive stimulation (noise, number of people, clutter), under-stimulation (no objects to view or touch, poor lighting), inappropriate room temperature (too hot or cold), and way-finding challenges (difficulties locating bathroom, bedroom, kitchen).53 This can be gleaned through key informant interviews or direct observation through a home evaluation by occupational therapists or other qualified professionals.

Devise a Treatment Plan (Figure 1-Step 4)

Although antipsychotic use has declined, there is still over-reliance on these and other pharmacologic treatments, despite limited efficacy data and increased mortality and morbidity (e.g., falls) risks.40,58 Moreover, no pharmacologic solutions address potential underlying causes of behaviors or behaviors most distressful to families.32

A treatment plan may include generalized and behavior-specific targeted approaches and if necessary, referrals to dementia specialists (geriatric psychiatrists, neurologists specializing in cognitive disorders, geriatricians; nurses, psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists, physical therapists).

Generalized nonpharmacologic approaches address behaviors by improving daily life overall. Evidence from randomized, controlled clinical trials supports use of structured activity, caregiver education and training, and adult day services with small to very large effect sizes reported.59-65

Activity

Mr A: I don't … do exercise….mostly I do a little gardening… The rest of the time I read the paper or watch TV. ….oh, I can walk more than 2 or 3 blocks. I do a lot of walking.

Physical exercise plus caregiver training in behavioral management techniques can reduce patient depression,66 although unclear is the specific dose, intensity, and type of exercise that maximizes benefit. As formal exercise routines can be difficult to implement, simple activities such as taking routine daily walks with the caregiver can enhance feelings of well-being and sleep. Purposeful activities (social, cognitive, physical) with intrinsic interest or meaning to the patient and that are graded to their capabilities (e.g., executive function, motoric abilities) can reduce agitation and other behaviors families find disruptive.67 For example, a patient with moderate dementia with a previous interest in fishing may be able to organize a tackle box and sort plastic equipment (lures, weights); or in the moderate-severe stage, look through a fishing magazine or watch a video on fishing. Purposeful and regular activities at home that tap into previous interests and procedural memory can prevent or reduce agitation and depression.67,68

Caregiver Education and Training

Mr Z: I think it would be very advisable to have some classes that people can go to in order to really understand the situation.

A meta-analysis of 23 randomized clinical trials provides strong confirmation of the benefits of caregiver education and skills training interventions for reducing behavioral symptoms. Collectively, these trials involved 3,279 community-dwelling caregivers and patients. Significant treatment effects were demonstrated for reducing behavioral symptoms [effect size=0.34 (95% CI: 0.20 – 0.48, Z=4.87; p<0.01) and caregiver negative reactions [effect size=0.15 (95% CI: 0.04 – 0.26, Z=2.76; p=0.006).65 Even small improvements can make a critical difference in helping patients to continue living at home with quality of life.

Effective interventions were wide-ranging and included caregiver education, skills training (problem solving, communication strategies), social support (linking caregivers to others), and/or environmental modifications (assistive device use, creating a quiet uncluttered space). Interventions varied in dose, intensity, and delivery mode (telephone, mail, face-to-face, groups, computer technologies); however, the most effective were patient-and caregiver-centered such that information and support addressed the challenges families identified as troublesome. Addressing multiple areas of immediate need and providing problem-solving skills to prevent, manage, or minimize behavioral occurrences were common among effective interventions.65 Although not all caregiver support programs (e.g., counseling) result in behavioral symptom reduction, benefits for caregivers overall are manifold and equally important and include enhanced skills and confidence, less distress with behaviors, and nursing home placement delay.64

Although these interventions are not widely available yet and can be time consuming, it is possible to implement these approaches in primary care by involving nurses or other staff who can meet with caregivers during patient encounters.69 Alternately, referral to local Alzheimer's Associations may be helpful. Some branches offer caregiver interventions and group support. Patients with safety issues or functional limitations can be referred for occupational therapy home evaluation and treatment which may be reimbursable and affords an opportunity for systematic caregiver education and instruction in behavioral management.70

Adult Day Services

Dr J:… Another option would be referring somebody to adult day [services] every day – which this patient would really enjoy … it takes the burden off of the caregiver by having other people watch the patient.

A systematic review of studies on adult day services shows multiple benefits including reductions in behavioral symptoms and caregiver distress.71,72 However, level of exposure for symptom reduction is unclear and outcomes may be patient-specific.

Other Generalized Strategies

Music interventions ranging from recorded music or music activities in individual or group settings are promising.73 Musical abilities appear preserved in some patients. A few randomized trials found reduced aggression, agitation and wandering while patients were engaged in music although more careful research is necessary.73

Evidence for other nonpharmacologic approaches is inconclusive. A systematic review of 17 controlled studies testing cognitive training using compensatory (e.g., learning to organize or visualize information) or restorative (e.g., spaced retrieval requiring patients to recall information over progressively longer time frames) strategies found a medium effect size (0.47) in many areas of functioning, yet limited evidence for improving behaviors.73 Recent evidence from a year-long intervention involving psychosocial support and cognitive exercises (compensatory strategies) benefited mood and cognition in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and moderate dementia suggesting this is a promising area of investigation.74

There is inconsistent to no evidence supporting reminiscence therapy (discussion of past activities, events, experiences), validation therapy (work-through unresolved conflicts), simulated presence therapy (use of audiotapes by family members of patient's life), aromatherapy (use of fragrant plant oils), or light therapy in reducing behavioral symptoms.73,75 There are no quality studies for acupuncture. [See Appendices A and B]. Most studies are limited by small samples, lack of methodological rigor and precision in measuring behavioral symptoms, or exclusive focus on nursing home residents.

Generalized Strategies for Disease Stages

Most generalized strategies have been evaluated with patients at mild to moderate dementia yet may be effective in mild cognitive impairment. For example, caregiver education concerning functional consequences of memory loss, training patients in compensatory strategies (e.g., memory boards, calendars, external prompts), appear helpful although more randomized trials are needed.

There is insufficient research for nonpharmacologic strategies with severely impaired patients, although most community-based trials referenced above include some patients with MMSE scores <10. A meta-analysis of 21 nonpharmacologic therapies targeting patients in day hospitals or residential care facilities found limited, but moderate to high quality evidence for use of sensory-focused strategies such as calming music and aromas, reflexology (application of pressure to specific points on hands and feet), and other multi-sensory stimulation therapies.51 However, research is limited on the use of these techniques at home and whether caregivers can implement them effectively. (See Table 2 for generalized approaches for Mr. A).

Table 2. General Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Managing Behavioral Symptoms.

| Domain | Key Strategies |

|---|---|

| Communication |

|

| Simplify environment |

|

| Caregiver education and support |

|

| Simplify tasks |

|

| Activities |

|

Note: Domains and strategies listed are potential approaches used in randomized clinical trials but are not exhaustive. A suggested strategy may be effective for one patient but not another. Any one strategy may not have been evaluated for effectiveness for use with all dementia patients with the same presenting behavior. Strategies listed above should only be considered once thorough assessment (description and decoding – Figure 1, steps 2 and 3) has been completed.

Targeted Approaches

Mr Z: … he was afraid to sleep by himself and he wanted me to sleep with him… he needed the lights to be on during the whole night because he was afraid. He didn't feel secure. I decided to buy one of those lights that you keep on all night, and it's working.

A targeted approach involves implementing specific strategies directed at a single behavior (e.g., agitation when bathing). It typically involves problem-solving to identify precipitating and modifiable causes and consequences of the identified behavior, followed by efforts to modify these conditions (e.g., assuring bathroom is warm, water temperature not too hot). It relies on a key informant (family member) who works with the clinician to characterize the behavior and help identify modifiable factors and strategies (Figure 1, Steps 2 and 3).

A targeted approach would be useful for Mr A′s sleep disturbance. It would first involve ruling out depression and other causes, examining the physical environment where he slept, and assessing his daily and bedtime routines (Figure 1, Steps 2 and 3). A home evaluation of sleeping quarters and nighttime routines by an occupational therapist or other qualified professional could provide important information for devising a treatment plan. Based on identifying potential contributing factors to the behavior, potential strategies might include eliminating caffeinated beverages and/or napping in the afternoon, implementing a structured daily routine of exercise and/or meaningful activity, implementing a structured nighttime routine possibly involving soft music, setting a tranquil tone, and removing stimulating environmental distractions (television). These approaches can be highly effective in managing sleep disturbances.

A randomized trial with 272 community-dwelling patients and their caregivers showed that targeting behaviors most distressful to caregivers and modifying potential triggers improved or eliminated patient symptoms and enhanced caregiver well-being and skills.32 The Resources for Enhancing Caregiver Health initiative (REACH II) involving 600 diverse families (Caucasian, African American and Hispanic) demonstrated that a targeted problem behavior approach combined with other caregiver support strategies (e.g., generalized approach) effectively reduced behavioral symptoms and associated caregiver distress.59

Few studies have been conducted that target specific behaviors in community-dwelling patients. For wandering, 4 systematic reviews of nonpharmacologic strategies found no evidence of benefit from exercise or walking therapies in randomized trials, whereas tracking devices and home alarms effectively detected wandering and locating lost patients in uncontrolled, non-randomized studies.73 For aggression, minimizing risk factors such as patient depression and pain, caregiver burden, and poor patient-caregiver relationship may be preventive.14,76 Alternately, educating caregivers in strategies to use when aggressive behaviors occur such as distracting the patient, backing away and leaving the room (if patient is safe) can be helpful. Studies of nursing home residents suggest that personalizing the bathing experience (e.,g, offering choice, creating a spa experience),79 can minimize agitation and aggression; however, these strategies have not been tested in homes in randomized trials.

Determine Effectiveness of Nonpharmacologic Strategies (Figure 1-Step 5)

Dr J: the sleep problems persist.…We were trying to think of all the different angles. He wasn't depressed… he wasn't in pain. We worried that his vision was poor, so we had him see the eye doctors. We had him put in a nightlight so he wouldn't flip on all the lights for the whole family. …..we talked about the whole idea of good sleep hygiene. The patient had been drinking a fair amount of caffeinated beverages and I think he normally had a glass of wine at night. We had been tapering down on those things. He was in a quiet place…. he was just laying around the house and napping a lot. So, getting him out of the house and into a senior center was another remedy that we came up with and that actually worked pretty well. On the days that he went to the senior center, he slept pretty well at night.

Step 5 involves evaluating the effectiveness of the nonpharmacologic treatment for resolving behavioral symptoms. This includes determining whether the caregiver implemented the nonpharmacologic strategies, and if so, if they were implemented correctly, and then whether the behavior was resolved (eliminated, reduced severity and/or frequency or better management). For example, Mr Z did not followup with obtaining a safety alert bracelet for Mr A.

As shown, Dr J tried various strategies until resolution was obtained. If there are no behavioral improvements, it is important to determine if characteristics of the behavior or the patient's environment or health status have changed, or if the strategy itself is not effective. Specialist referral should also be considered at that point.

On-going Monitoring (Figure 1–Step 6)

As behavioral symptoms fluctuate and the patient's context change, Figure 1 and its steps reflect a repetitive cycle. Essential to using nonpharmacologic approaches is monitoring treatment plans. If resolution using strategies is not obtained, other treatment options such as referral to specialists should be considered.

Adverse Effects

Nonpharmacologic strategies do not carry the level of risk associated with pharmacologic treatments. However, potential for adverse effects should not be ignored. A few studies report increased agitation in cognitive/emotion-oriented interventions.73 Increased agitation and physical aggression has also been reported for some sensory approaches (music therapy, massage/touch therapies, aromatherapy).73,78 As nonpharmacologic modalities involve manipulations of persons, behaviors, cognitions and environments, they represent active treatments necessitating careful monitoring of behavioral improvement or worsening, with particular attention to potential for heightened agitation.

Challenges

One challenge is that our framework may be labor intensive as it involves on-going evaluation, problem-solving, strategy modification, and access to dementia care specialists (geropsychiatrists, occupational therapists, nurses, social workers). Reimbursement and care systems do not adequately support their use. Busy clinicians may find it challenging to integrate the 6-steps over short patient visits. However, forming a dementia team with other health professionals is an effective strategy to address this potential challenge.79 Another challenge is lack of guidelines for starting or stopping strategies. However, essential to using strategies is ongoing monitoring. Yet another challenge is that nonpharmacologic strategies may be effective for certain symptoms (repetitive questioning, agitation), but not others (hallucinations). Although guidelines for using nonpharmacologic strategies by disease stage and behavioral-type are still needed, this should not deter their use now. It is also unclear as to the best combination of strategies for optimizing treatment effects or how nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches may augment each other.

There may be no single approach for addressing any one behavior; it may require a multi-component approach (generalized plus tailored). Our 6-step framework serves as a guide for clinicians to consider multiple approaches. Finally, detection, assessment and behavioral symptom management may be challenging to apply to patients with dementia who live alone and do not have family.

Conclusion

Behavioral symptoms are a major source of disability making their clinical management critical. Unfortunately, most patients treated in primary care do not receive thorough assessment, treatment and monitoring of behavioral symptoms.80,81 Mr. A experienced numerous behavioral symptoms including hearing voices at night which often trigger a physician's prescription for an anti-psychotic. However, as illustrated, a combination of nonpharmacologic strategies including an evaluation of Mr A′s hearing and hearing aids effectively managed his sleep disturbance without drug use.

There is strong evidence for both generalized and targeted nonpharmacologic treatments. Essential to a nonpharmacological approach is educating caregivers in ways to effectively prevent and manage behavioral symptoms. As nonpharmacologic approaches yield high levels of patient and caregiver satisfaction, quality of life improvements and reduced behavioral symptoms with minimal risk and adverse reactions, they should be part of standard dementia care.

Acknowledgments

Dr Gitlin has been supported for research reported in this article in part by funds from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute on Nursing (Research Grant # RO1 AG22254); National Institute on Aging (Research Grant # 1R01AG041781-01A); the PA Department of Health, Tobacco Settlement (SAP # 100027298), the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant # R21 MH069425), and Alzheimer's Grant NPSASA-10-174265).

Dr Lyketsos was supported by the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (P50-AG005146).

Sponsorship Statement: Funding agencies did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Dr Lyketsos has received grant support (research or CME) from NIMH, NIA, Associated Jewish Federation of Baltimore, Weinberg Foundation, Forest, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Eisai, Pfizer, Astra-Zeneca, Lilly, Ortho-McNeil, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, National Football League, Elan, Functional Neuromodulation Inc.; has served as consultant/advisor for Astra-Zeneca, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Eisai, Novartis, Forest, Supernus, Adlyfe, Takeda, Wyeth, Lundbeck, Merz, Lilly, Pfizer, Genentech, Elan, NFL Players Association, NFL Benefits Office, Avanir, Zinfandel; and received honorarium or travel support from Pfizer, Forest, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Health Monitor

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr Gitlin and Dr Kales have no disclosures or sources of conflict.

Contributor Information

Helen C. Kales, Email: kales@umich.edu.

Constantine G. Lyketsos, Email: Kostas@jhmi.edu.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Association. 2012 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(2):131–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyketsos CG, Carrillo MC, Ryan JM, Khachaturian AS, Trzepacz P, Amatniek J, Cedarbaum J, Brashear R, Miller DS. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement The Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7(5):532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Dementia: A public health priority. World Health Organization; Geneva Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan CM, Arling G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in care for older adults with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):813–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halbauer JD, Wesson Ashford JW, Zeitzer JM, Adamson MM, Lew HL, Yesavege JA. Neuropsychiatric diagnosis and management of chronic sequelae of war-related mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. JRRD. 2009;46(6):757–796. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2008.08.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Steinberg M, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer's disease clusters into three groups: The Cache County study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(11):1043–1053. doi: 10.1002/gps.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawlor B. Managing behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:463–465. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.6.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunik ME, Snow AL, Davila JA, et al. Causes of aggressive behavior in patients with dementia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1145–1152. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04703oli. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colena CCI Agitation: A conceptual overview. In: Behavioral complications in Alzheimer's disease. Lawlor BA, editor. American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1995. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aalten P, de Vugt ME, Jaspers N, Jolles J, Verhey FR. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Part I: Findings from the two-year longitudinal maasbed study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(6):523–530. doi: 10.1002/gps.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aalten P, de Vugt ME, Jaspers N, Jolles J, Verhey FR. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Part II: Relationships among behavioural sub-syndromes and the influence of clinical variables. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(6):531–536. doi: 10.1002/gps.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryu SH, Katona C, Rive B, Livingston G. Persistence of and changes in neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease over 6 months: The LASER-AD study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(11):976–983. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.11.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spalletta G, Musicco M, Padovani A, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and syndromes in a large cohort of newly diagnosed, untreated patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(11):1026–1035. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6b68d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P, et al. Point and 5-year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: The Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finkel SI, Burns A. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): A clinical and research update. International Psychogeriatrics. 2000;12(1) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyketsos CG. International Psychogeriatrics. Published online by Cambridge University Press; 2007. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (a.k.a. BPSD) and dementia treatment development. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=Lyketsos%20CG.%20Neuropsychiatric%20symptoms%20(a.k.a.%20BPSD)%20and%20dementia%20treatment%20development.%20%20Internati onal%20Psychogeriatrics. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marra C, Quaranta D, Zinno M, et al. Clusters of cognitive and behavioral disorders clearly distinguish primary progressive aphasia from Frontal Lobe Dementia, and Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24(5):317–326. doi: 10.1159/000108115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nyatsanza S, Shetty T, Gregory C, Lough S, Dawson K, Hodges JR. A study of stereotypic behaviours in Alzheimer's disease and Frontal and Temporal Variant Frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(10):1398–1402. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.10.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Staekenborg SS, Su T, van Straaten EC, et al. Behavioural and psychological symptoms in vascular dementia; differences between small- and large-vessel disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(5):547–551. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.187500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eustace A, Coen R, Walsh C, et al. A longitudinal evaluation of behavioural and psychological symptoms of probable Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(10):968–973. doi: 10.1002/gps.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtzer R, Tang MX, Devanand DP, et al. Psychopathological features in Alzheimer's disease: Course and relationship with cognitive status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(7):953–960. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magai C, Hartung R, Cohen CI. Caregiver distress and behavioral symptoms. In: Lawlor BB, editor. Behavioral complications in Alzheimer's disease. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Den Wijngaart MA, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Felling AJ. The influence of stressors, appraisal and personal conditions on the burden of spousal caregivers of persons with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(6):626–636. doi: 10.1080/13607860701368463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okura T, Langa KM. Caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with cognitive impairment: The Aging, Demographics and Memory Study (ADAMS). Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Disorders. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Discord. 2011;25(2):116–21. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318203f208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilley DW, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Beck TL, Evans DA. Influence of behavioral symptoms on rates of institutionalization for persons with Alzheimer's disease. Psychol Med. 2004;34(6):1129–1135. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan DC, Kasper JD, Black BS, Rabins PV. Presence of behavioral and psychological symptoms predicts nursing home placement in community-dwelling elders with cognitive impairment in univariate but not multivariate analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(6):548–554. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.6.m548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karttunen K, Karppi P, Hiltunen A, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in patients with very mild and mild Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(5):473–482. doi: 10.1002/gps.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okura T, Plassman BL, Steffens DC, Llewellyn DJ, Potter GG, Langa KM. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms and their association with functional limitations in older adults in the United States: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(2):330–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okura T, Plassman BL, Steffens DC, Llewellyn DJ, Potter GG, Langa KM. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of institutionalization and death: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):473–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kales HC, Chen P, Blow FC, Welsh DE, Mellow AM. Rates of clinical depression diagnosis, functional impairment, and nursing home placement in coexisting dementia and depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):441–449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.6.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz R, O'Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist. 1995;35(6):771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW. Targeting and managing behavioral symptoms in individuals with dementia: A randomized trial of a nonpharmacological intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1465–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Vugt ME, Stevens F, Aalten P, et al. Do caregiver management strategies influence patient behaviour in dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):85–92. doi: 10.1002/gps.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beeri MS, Werner P, Davidson M, Noy S. The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer's disease patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(5):403–408. doi: 10.1002/gps.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murman DL, Chen Q, Powell MC, Kuo SB, Bradley CJ, Colenda CC. The incremental direct costs associated with behavioral symptoms in AD. Neurology. 2002;59(11):1721–1729. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036904.73393.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for Dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(15):1934–1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Davis SM, Hsiao JK, Ismail MS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(15):1525–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballard C, Hanney ML, Theodouou M, Douglas S, McShane R, Kossakowski K, et al. The dementia antipsychotic withdrawal trial (DART-AD): Long term follow-up of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2009;8:151–157. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffee K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of Dementia: A review of evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293(5):596–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kales HC, Valenstein M, Kim HM, et al. Mortality risk in patients with dementia treated with antipsychotics versus other psychiatric medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1568–76. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: A review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. Performance Measure Set. 2010 http://www.ama-ssn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/370/dementia-public-comments.

- 43.Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: Consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):889–898. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.California Workgroup on Guidelines for Alzheimer's Disease Management – Final Report. 2008 Apr; http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/alzheimers.

- 45.NICE-SCIE Supporting Caregivers and patients. 2011 http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/10998/30320.

- 46.American Academy of Neurology. 2001 http://www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/dementia_guideline.pdf.

- 47.Rabins PV, Blacker D, et al. American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Am J Psychiatry. (Second) 2007;164(12 Suppl):5–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, Blank K, Doraiswamy MP, Kalunian DA, Yaffe K. Task Force of American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry: Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(7):561–572. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Medeiros K, Robert P, Gauthier S, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Clinician rating scale (NPI-C): Reliability and validity of a revised assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(6):984–994. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the neuropsychiatric inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kverno KS, Black BS, Nolan MT, Rabins PV. Research on treating neuropsychiatric symptoms of advanced dementia with non-pharmacological strategies, 1998-2008: A systematic literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(5):825–843. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hodgson N, Gitlin LN, Winter L, Czekanski K. Undiagnosed illness and nueropsychiatric behaviors in community-residing older adults with dementia. Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Disorders. 2010;24(4):603–609. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f8520a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gitlin LN, Schinfeld S, Winter L, Corcoran M, Hauck W. Evaluating home environments of person with dementia: Inter-rater reliability and validity of the home environmental assessment protocol (HEAP) Disability and Rehabilitation. 2002;24:59–71. doi: 10.1080/09638280110066325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: The COPE randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(9):983–991. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Czaja SJ, Gitlin LN, Schulz R, Zhang S, Burgio LD, Stevens AB, Nichols LO, Gallagher-Thompson D. Development of the risk appraisal measure: A brief screen to identify risk areas and guide interventions for dementia caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):1064–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norton MC, Piercy KW, Rabins PV, Green RC, Breitner JCS, Ostbye T, Corcoran C, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Lyketsos CG, Tschanz JT. Caregiver – recipient closeness and symptom progression in Alzheimer's disease. The Cache County dementia progression study. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2009;64B(5):560–568. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spillman BC, Long SK. Does high caregiver stress predict nursing home entry? Inquiry. 2009;46(2):140–161. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_46.02.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kales HC, Zivin K, Kim HM, et al. Trends in antipsychotic use in dementia 1999-2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):190–197. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gitlin LN, Corcoran M, Winter L, Boyce A, Hauck WW. A randomized, controlled trial of a home environmental intervention: Effect on efficacy and upset in caregivers and on daily function of persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 2001;41(1):4–14. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Corcoran M, Dennis MP, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW. Effects of the home environmental skill-building program on the caregiver-care recipient dyad: 6-month outcomes from the Philadelphia REACH initiative. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):532–546. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gitlin LN, Belle SH, Burgio LD, Czaja SJ, Mahoney D, Gallagher-Thompson D, Burns R, Hauck WW, Zhang S, Schulz R, Ory MG for REACH Investigators. Effect of multicomponent interventions on caregiver burden and depression: The REACH multisite initiative at 6-month follow-up. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):361–374. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Graff MJ, Adang EM, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekker J, Jonsson L, Thijssen M, Hoefnagels WH, Rikkert MG. Community occupational therapy for older patients with dementia and their care givers: Cost effectiveness study. BMJ. 2008;336(7636):134–138. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39408.481898.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, Roth DL. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592–1599. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242727.81172.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:946–953. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2015–2022. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Burke J, Chernett N, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: A randomized pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(3):229–239. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318160da72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Teri L, Logsdon RG, Peskind E, et al. Treatment of agitation in AD: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Neurology. 2000;55(9):1271–1278. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.9.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ, Lummus A. Primary care interventions for dementia caregivers: 2-year outcomes from the REACH study. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):547–555. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gitlin LN, Jacobs M, Vause-Earland T. Translation of a dementia caregiver intervention for delivery in homecare as a reimbursable Medicare Service: Outcomes and lessons learned. Gerontologist. 2010 doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gitlin LN, Reever K, Dennis MP, Mathieu E, Hauck WW. Enhancing quality of life of families who use adult day services: Short and long-term effects of the “Adult Day Services Plus” program. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(5):630–639. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gaugler JE, Jarrott SE, Zarit SH, Stephens MA, Townsend A, Greene R. Respite for dementia caregivers: The effects of adult day service use on caregiving hours and care demands. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15(1):37–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203008743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Neil ME, Freeman M, Christensen V, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral symptoms of dementia: A systematic review of the evidence. VA-ESP Project #05-22. 2011 http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/Dementia-Nonpharm.pdf. [PubMed]

- 74.Olazaran J, Muniz R, Reisberg B, et al. Benefits of cognitive-motor intervention in MCI and mild to moderate alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2348–2353. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147478.03911.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Burns A, Perry E, Holmes C, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial of Melissa officinalis oil and donepezil for the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31(2):158–64. doi: 10.1159/000324438. Epub 2011 Feb 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nguyen VT, Love AR, Kunik ME. Preventing aggression in persons with dementia. Geriatrics. 2008;63(11):21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sloane PD, Hoeffer B, Mitchell CM, et al. Effect of person-centered showering and the towel bath on bathing-associated aggression, agitation, and discomfort in nursing home residents with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1795–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cooke ML, Moyle W, Shum DH, et al. A randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of music on agitated behaviours and anxiety in older people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(8):905–916. doi: 10.1080/13607861003713190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with alzheimer disease in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reuben D, Levin J, Frank J, Hirsch S, McCreath H, Roth C, Wenger N. Closing the dementia care gap: Can referral to Alzheimer's Association chapters help? Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2009;5:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chodosh J, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. Caring for patients with dementia: How good is the quality of care? Results from three health systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(8):1260–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The Timed “Up & Go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]