Abstract

Generating and maintaining a robust CD8+ T cell response in the face of high viral burden is vital for host survival. Further, balancing the differentiation of effectors along the memory precursor effector cell (MPEC) vs. short-lived effector cell (SLEC) pathways may be critical in controlling the outcome of virus infection with regard to clearance and establishing protection. While recent studies have identified several factors that have the capacity to regulate effector CD8+ T cell differentiation, e.g. inflammatory cytokines, we are far from a complete understanding of how cells choose the MPEC vs. SLEC fate following infection. Here we have modulated the infectious dose of the poxvirus vaccinia virus as an approach to modulate the environment present during activation and expansion of virus-specific effector cells. Surprisingly, in the face of a high virus burden, the number of SLEC was decreased. This was the result of increased nTreg generated by high viral burden as depletion of these cells restored SLEC. Our data suggest Treg modulation of differentiation occurs via competition for IL-2 during the late expansion period, as opposed to the time of T cell priming. These findings support a novel model wherein modulation of the Treg response as a result of high viral burden regulates late stage SLEC number.

INTRODUCTION

CD8+ T cells are a critical contributor to the clearance of viral infection. Following infection, naïve antigen specific cells will undergo marked expansion and in the process differentiate to become effector cells with the capacity to mediate viral clearance. After the peak of CD8+ T cell response, greater than 90% of these cells will die during the contraction phase of the response, with the surviving cells giving rise to a stable self renewing memory pool (1).

Recent data show that effector cells with increased potential to persist longterm as self renewing memory cells, termed memory precursor effector cells (MPEC), can be identified by the expression of the IL-7R-alpha (CD127) at the peak of CD8+ T cell expansion (2,3). In contrast, short-lived effector cells (SLEC) are identified by the expression of KLRG1, a marker of replicative senescence (4). As suggested by their name, SLEC have limited potential to persist long term and are thought to be terminally differentiated (5,6).

Inflammatory cytokines, shown to be important for the generation of optimal effector responses as well as memory formation (7), appear to drive these effector cells down the terminally differentiated pathway. For example, prolonged exposure to IL-2 has been reported to promote SLEC generation (8). IL-12, another important proinflammatory cytokine, can also promote SLEC differentiation by increasing expression of the transcription factor T-bet (5,9). Thus, in addition to providing general signals promoting naïve CD8+ T cell activation, inflammation is a potent regulator of SLEC formation (10). Certainly, the inflammatory environment can differ across infections. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that distinct mediators contribute to T cell differentiation when individual infectious models are interrogated. For example, IL-12 is dispensable for SLEC differentiation following infection with vaccinia virus (VV), Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV) or Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV), but not L. monocytogenes (11,12).

While initially associated with regulating the immune response to autoantigens by suppression of self-reactive T cells (13–15), CD4+ CD25+ forkhead box protein 3(Foxp3) expressing cells, known as natural Treg (nTreg) (16), have also been shown to negatively regulate the immune response during viral infections. For example, depletion of nTreg by administration of anti-CD25 antibody followed by infection with VV or HSV resulted in elevated CD8+ T cell responses (17–19). As a result of their constitutive expression of the high affinity IL-2 alpha chain (CD25), nTreg posses the potential to take up significant amounts of IL-2 from the environment. In support of this, recent studies have implicated nTreg as a modulator of effector cell expansion through IL-2 uptake (20).

Although virus burden can exert significant influence over the size of the effector cell response (21,22), it is not clear whether it regulates the differentiation of effector cells. Further, whether virus dose-dependent differences in the size of the response selectively impacts effectors in a differentiation-dependent fashion is unknown. In this study, we have addressed these questions by infecting mice with either a high or low dose of VV. We observed that the virus-specific response in mice infected with a low dose of vaccinia virus was skewed toward SLEC. The selective increase in SLEC in low dose infected mice could not be explained by increased proliferation in this population. However, depletion of natural regulatory T cells (Tregs), which we found to be present at increased numbers at late times postinfection in high dose infected mice, led to an increase in the number of B8R-specific cells and a skewing of the response toward SLEC. Treatment of mice with recombinant human IL-2 or depletion of Tregs following the initiation of the response after infection with the high dose resulted in increased SLEC supporting a mechanism whereby Treg regulate effector cells by IL-2 uptake at the post-priming stage. These data provide evidence for a role for viral burden in effector cell differentiation, with increased viral dose inhibiting the number of SLEC at the peak of the response through increasing the number of nTreg during the expansion phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and infections

Six to ten week old, female C57BL/6 mice (Frederick Cancer Research Facility, National Cancer Institute, Fredrick, MD) were used throughout this study. Mice were maintained in the Wake Forest University School of Medicine animal facilities, under specific-pathogen-free conditions and in accordance with approved IACUC protocols. Infections were done with 1×106 (high dose) or 1–3×104 (low dose) PFU of VV-GP33 (23) delivered intraperitoneally.

Cell staining and flow cytometry

For detection of CD8+ T effector cells, a total of 1×106 spleen cells from vaccinia virus infected mice were incubated for 30 minutes on ice with B8R Tetramer (NIH tetramer core facility, Emory University, Atlanta, GA) together with anti-CD127 (Biolegend, SB/199), -CD44 (Biolegend, IM7), -KLRG1 (Biolegend, 2F1/KLRG1) and -CD8α (BD Bioscience, 53–6.7) antibodies. Cells were then washed twice and samples acquired on a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer. For analysis of T-bet and eomes cells were stained as above followed by fixation and permeabilization using the FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated with T-bet-PECy7 (eBioscience, eBio4B10) and eomes-Alexa Fluor 488 (eBioscience, Dan11mag) diluted in 1X Permeabilization Buffer. Isotype controls we used in negative control samples. Active caspase 3 in B8R+ cells was assessed using anti-caspase 3, active form (BD Biosciences, C92-605) following permeabilization with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions. For detecting Tregs, cells were stained with antibodies specific for CD4 (Biolegend, GK1.5), CD44 (Biolegend, IM7), CD25 (Biolegend, PC61), CTLA4 (Biolegend, UC10-4B9), CD69 (Biolegend, H1.2F3) and GITR (Biolegend, YGITR 765) antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. After washing, cells were incubated for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature in a Foxp3 fix/perm buffer (Biolegend). Cells were then washed and incubated for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature in Foxp3 perm buffer (Biolegend). Following washing, cells were stained with anti-Foxp3 (Biolegend, MF-14) in perm buffer for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature after which they were washed. Data were acquired using a BD FACSCanto II and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc). For analysis of DC, mice received anti-CD25 (Bio X Cell, PC-61.5.3) antibody on d1 prior to infection with the high virus dose. On d2 p.i., dendritic cells in the spleen were assessed by flow cytometric analysis for the expression of CD80 and CD40. Cells with high levels of CD40 (BD Bioscience, 3/32) and CD80 (BD Bioscience, 16-10A1) were considered mature.

Analysis of pSTAT5

Spleens were isolated and immediately placed into 5 ml of PBS containing 1.6% formaldehyde. The spleen was then dissociated and placed through a 70 micron filter followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 minutes. Twenty ml of ice cold methanol was subsequently added with constant vortexing. Cells were placed briefly on ice and subsequently stored at −80°C. For staining, 0.5 ml of cells were removed and washed 3X in staining buffer. Cells were stained with antibodies to CD4, FoxP3 (clone NRRF-30, eBioscience), CD25 and pSTAT5 (clone 47, BD Biosciences) and samples acquired on a BD FACSCanto II cytometer.

Plaque assay

Spleen or ovaries from infected mice were homogenized, centrifuged and serial dilutions of the supernatant added to confluent BSC-1 cells in six-well plates. Plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C after which the media was aspirated and 2 ml of MEM+10% FBS added. Twenty-four hours later, monolayers were stained with crystal violet and plaques enumerated.

BrdU detection and recombinant IL-2 treatments

Infected mice received 500μl of BrdU (1.6mg/ml of BrdU (Sigma)) by i.p. injection. Five hours later splenocytes were isolated and stained on ice for 30 minutes with B8R Tetramer (NIH tetramer core facility, Emory University, Atlanta, GA) together with antibodies to CD127, CD44 (Biolegend), KLRG1 (Abcam) and CD8α (BD Biosciences). BrdU staining was carried out according to the supplied protocol (BD Biosciences). Recombinant human IL-2 treatment was done as previously described (24). Briefly, mice received two daily injections of 15,000 IU of recombinant human IL-2 from days three to six postinfection.

nTreg depletion

nTreg were depleted by injecting with 400μg of anti-CD25 (clone PC-61) or isotype (BioXCell) antibody one day prior to infection with vaccinia virus. For late nTreg depletion, mice were injected with 30μg of anti-FR4 (Biolegend) 2.5 days following infection with virus to prevent deleterious effects of anti-CD25 antibody on activated T cells. nTreg were also depleted by administering 30μg of anti-FR4 one day prior to infection.

Statistical analyses

Unless otherwise stated, all statistics were done using a two-tailed student’s t-test with a p value of ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

CD8+ effector responses are skewed towards SLEC following infection with a low vs. high virus dose

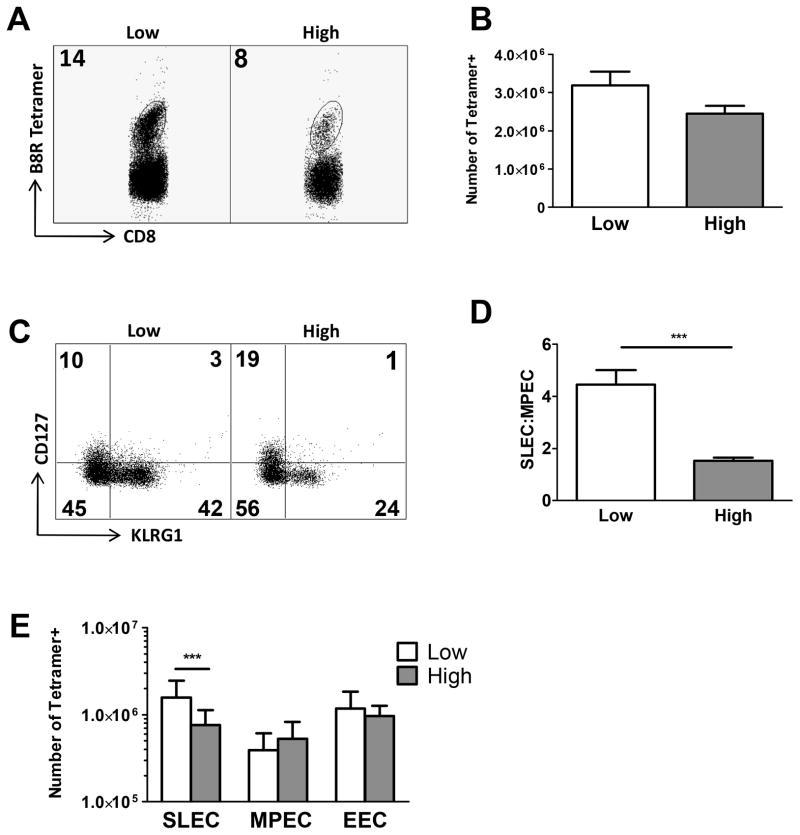

The differentiation of effector cells along the MPEC versus SLEC pathways is a highly regulated process. At present we know little about how viral burden perturbs this process. To address this question, C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) infected with either a high (1×106 PFU) or low dose (1–3×104 PFU) of VV. We then determined if the difference in virus would result in changes in the effector population generated to the immunodominant B8R20-27 epitope. On day 7 postinfection, splenocytes were isolated and the number of MPEC and SLEC determined by staining with tetramer together with KLRG1 and CD127. SLEC were identified as KLRG1HiCD127Lo and MPEC as KLRG1LoCD127Hi (5). Early effector cells (EEC), which express neither KLRG1 nor CD127 (25), were also analyzed. On day 7 postinfection, mice infected with high dose virus exhibited a decreased frequency of antigen specific cells, approximately 2-fold less when compared to mice infected with low dose virus (Fig. 1A). When the total number of antigen specific cells was determined there was a trend towards more antigen specific cells in the low dose infected mice, although this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Infection with a low or high dose of VV skews the response towards more SLEC in mice infected with low dose.

Wild type C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally infected with either a high or low dose of vaccinia virus. Seven days postinfection, spleens were harvested and the immunodominant B8R-specific population assessed. (A) Representative dot plots showing the frequency of B8R positive CD8+ T cells in mice infected with low or high dose virus. Cells were pre-gated for analysis of the CD8+CD44Hi population. (B) Averaged data showing the total number of B8R-specific CD8+ T cells. (C) Representative dot plot of B8R+CD8+ T cells stained with anti-KLRG1 and anti-CD127 antibodies. The upper left quadrant represents MPEC, the lower right quadrant SLEC, and the lower left quadrant early effector cells (EEC). Cells were pre-gated for analysis of the CD8+CD44Hi population. (D) Ratio of the frequency of SLEC to MPEC averaged across multiple mice. (E) Averaged data showing the number of SLEC, MPEC or EEC within the B8R+CD8+ T cell population. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (**=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001). Averaged data are from at least 23 mice assayed in a minimum of 7 independent experiments.

We next determined the differentiation state of the effector cells present in mice infected with the disparate amounts of virus. This analysis showed a higher frequency of SLEC in animals infected with the low compared to high virus dose (Fig. 1C), resulting in a skewing in the ratio of SLEC:MPEC within the total effector cell population (Fig. 1D). In agreement with these data, mice infected with the low dose virus exhibited an increased number of SLEC compared to high dose infected animals (Fig. 1E). There was no significant difference in the EEC or MPEC populations. The difference in the total number of B8R cells could be accounted for almost exclusively by this increase in SLEC in low dose infected mice. Taken together, these data show that increasing the infecting dose of VV led to a selective decrease in the terminally differentiated SLEC population.

Infection with high dose VV is associated with an increased viral burden

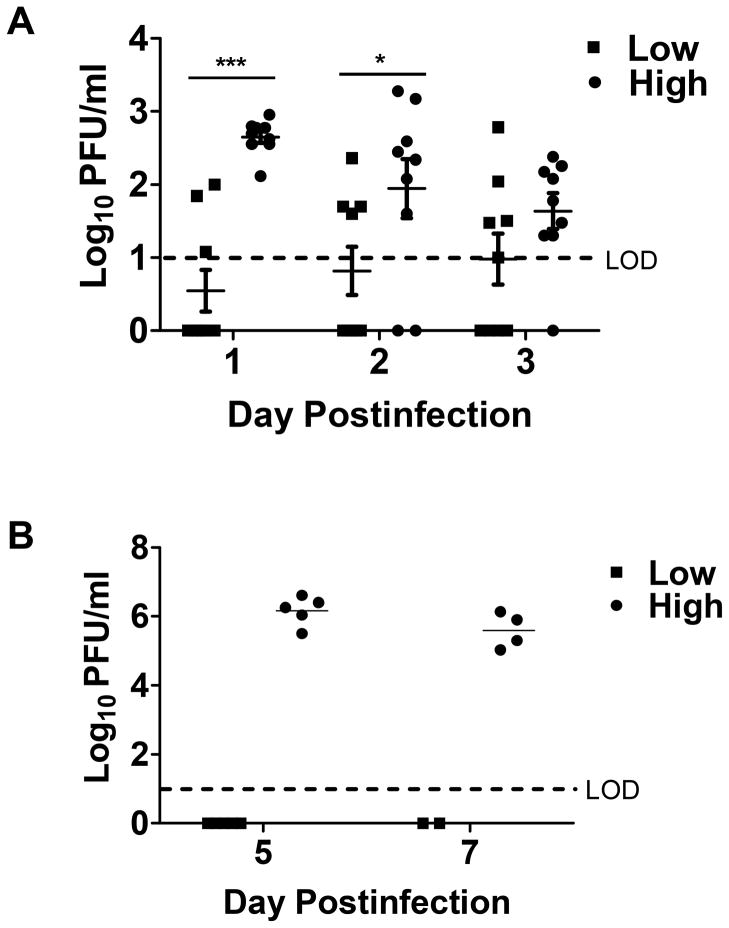

Increasing the viral dose administered to the animals should lead to increased viral burden in the spleen at early times postinfection, the window for priming the CD8+ T cell response. In addition, we would expect the higher dose to increase systemic virus at later times (d5-7), the point at which the effector population is undergoing continued expansion and differentiation. To assess viral load during the priming phase, spleens were isolated from mice on days 1–3 following infection. On days 1 and 2 p.i., virus was detected in animals infected with the high virus dose while virus was below the limit of detection in animals infected with the low dose (Fig. 2A). By day 3, virus began to decrease in the spleens of animals infected with the high virus dose such that there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups of mice.

Figure 2. Infection with high dose VV is associated with an increased viral burden.

C57BL/6 mice were infected with a high or low dose of VV i.p. (A) On days 1–3, viral burden in the spleen was assessed by plaque assay. B. Virus in the ovaries was measured on d5 and 7 p.i. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (*=p<0.05, ***=p<0.001). LOD, limit of detection.

To assess systemic virus present at later times postinfection, we measured viral load in the ovaries at days 5 and 7 p.i. In agreement with what was observed in the spleen at early times, infection with the higher viral dose resulted in high levels of systemic virus (Fig. 2B). Thus differences in viral burden were evident throughout both the T cell activation and expansion phases. As a result, dose associated differences in the environment could presumably regulate both early and late phases of the immune response.

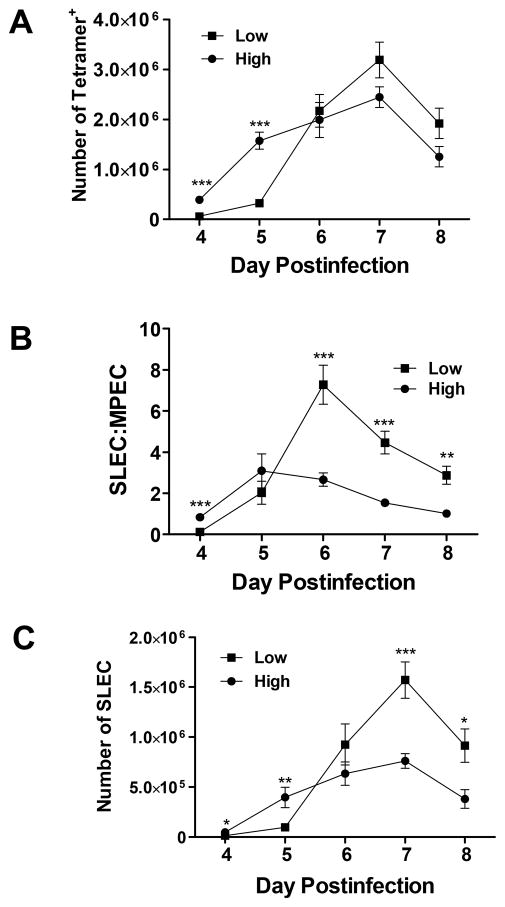

The increase in SLEC:MPEC ratio is apparent at multiple times postinfection

We next determined how differences in viral burden impacted the kinetics of SLEC vs. MPEC generation as it was possible that the skewing we observed at d7 p.i. was a reflection of increased kinetics of SLEC generation/expansion in these animals. The total number of B8R-specific cells as well as the number of B8R-specific MPEC and SLEC was assessed on days 4–8 following infection. Irrespective of the infecting dose, the peak of the B8R-specific response occurred on day 7 (Fig. 3A). We found that the number of B8R-specific cells was significantly higher at early times in the expansion phase (days 4 and 5) following infection with the higher virus dose. However, by d6 the difference in the number of B8R-specific cells between the two groups of animals was much less pronounced, with a trend toward higher numbers in the animals infected with the lower virus dose at days 7 and 8. Thus, infection with high dose virus resulted in a larger effector cell response at early times; however, the response in animals infected with the low dose of virus underwent rapid expansion between days 5 and 6 that resulted in a similar number of B8R-specific cells at this timepoint and eventually a trend towards higher numbers at later times.

Figure 3. The increased SLEC:MPEC ratio is present only at late times postinfection.

C57B/6 mice were infected with either a high or low dose of vaccinia virus (VV) i.p. On days 4–8 following infection, spleens were harvested and the immunodominant B8R-specific population assessed. (A) Total number of B8R-specific cells, (B) B8R+ SLEC:MPEC ratio and (C) B8R+ SLEC number over time. Data shown are the average of 10 mice for d4, at least 21 mice on d5, at least 13 mice on d6, at least 23 mice on d7, and 6 mice on d8. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (**=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001).

We next evaluated differentiation within the effector population over the course of the response. At d5 the ratio of SLEC:MPEC was relatively similar (Fig. 3B). The difference at d4 was the result of the very low number of SLEC present at this time following infection with the low virus dose (Fig. 3C). By d6 the skewing towards SLEC in mice infected with the low dose was readily observed and continued through d8 (Fig. 3B). This skewing in ratio was associated with a robust increase in the number of SLEC present the mice infected with the low virus dose (Fig. 3C). Based on these data, we conclude that the increased ratio of SLEC:MPEC observed following infection with the low dose is not a transient effect related to a difference in the kinetics of B8R-specific T cell generation. Further, the increased representation of SLEC within the population was not evident until d6 and thus was consistent with regulation at a late stage of the response.

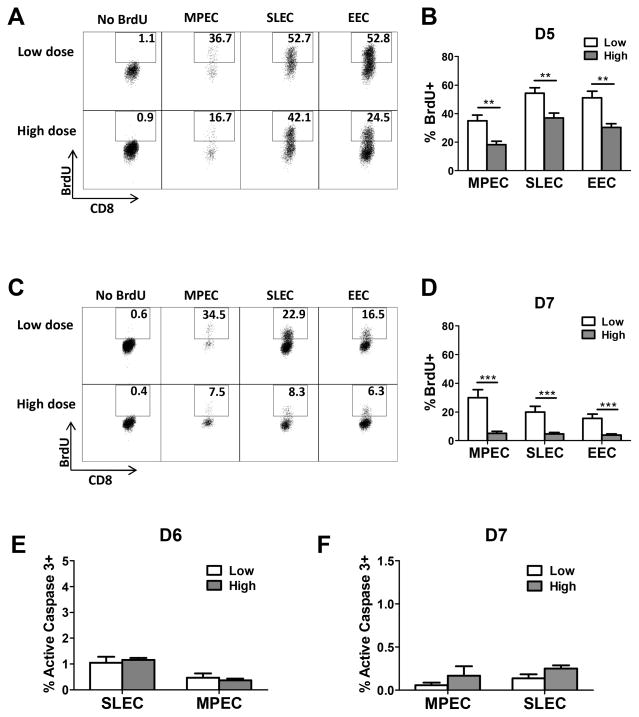

B8R+ cells undergo increased proliferation on d5-7 p.i. in low dose infected mice

One possibility to explain the increased skewing toward SLEC in mice infected with low dose virus was a selective increase in proliferation within this population. To test this possibility, animals received a 5 hour pulse with BrdU on day 5 or 7 p.i. Analysis of the BrdU+ populations showed that mice infected with the low virus dose exhibited an increase in proliferation at both timepoints compared to mice infected with the high virus dose (Fig. 4). This was the case for all of the populations (MPEC, SLEC, and EEC). While SLEC appeared to be the most highly proliferating population at d5 p.i., MPEC exhibited higher levels of BrdU+ cells at d7. Although effector cells were actively dividing in mice infected with the high virus dose at d5 p.i., by d7 there was limited evidence of proliferation. These data show that a selective increase in proliferation within the SLEC in mice infected with the low dose of virus cannot account for the skewing in this population.

Figure 4. B8R-specific effectors undergo increased proliferation in mice infected with low compared to high dose virus.

C57BL/6 mice were infected with either a high or low dose of vaccinia virus (VV) i.p. On days 5 or 7 after infection, mice received BrdU by i.p. injection. Five hours later BrdU incorporation was assessed. Representative dot plots as well as the average frequency of B8R+ MPEC and SLEC on d5 (A and B) and d7 (C and D) p.i are shown. Data in B are the average of 8 animals and in D6 animals analyzed in at least 3 independent experiments. On d6 (E) and 7 (F) p.i., MPEC and SLEC were assessed for the presence of active caspase 3. No significant differences were found between effectors isolated from high dose vs. low dose infected animals. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (**=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001).

SLEC from high and low dose infected animals exhibit similar levels of active caspase 3 positivity

Another possibility to explain the decreased number of SLEC in effectors following infection with the high virus dose was increased apoptosis in this population. To test this possibility, we examined cells for the presence of active caspase 3 at d6 and d7 p.i. As shown in figure 4E and F, there was no evidence of increased apoptosis in SLEC from high dose infected animals. In fact, apoptosis was minimal at these times. Thus the reduced number of SLEC in high dose infected animals cannot be explained by increased apoptosis in these cells.

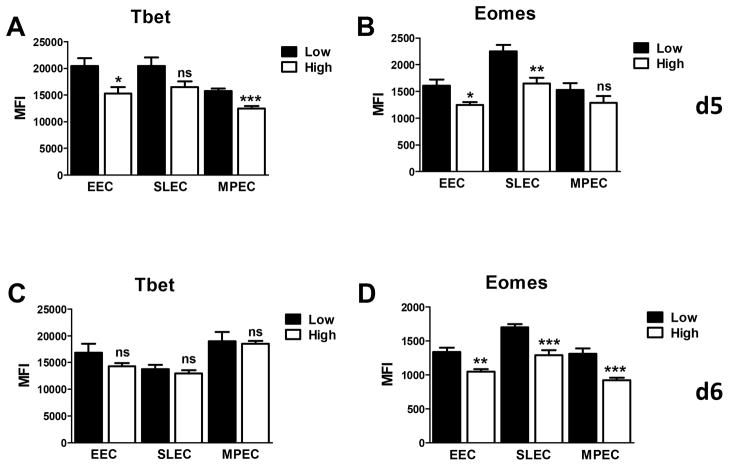

B8R+ cells from low dose infected animals exhibit an increased level of T-bet at d5 p.i

Inflammatory signals that promote SLEC generation also increase expression of the transcription factor T-bet (5). Thus we determined whether B8R+ effector cells from low dose infected animals exhibited increased expression of T-bet. EEC, MPEC, and SLEC populations were evaluated on d5 and d6 p.i. On d5 p.i., the expression of T-bet was significantly higher in EEC and MPEC from mice infected with the low dose of virus (Fig. 5A). T-bet expression was also increased in SLEC (although this did not statistical significance, p=0.067). Interestingly, the level of eomes was also increased in these effectors (Fig. 5B). By d6, levels of T-bet were similar in effector cells generated following infection with the high versus low dose of virus (Fig. 5C), while the decrease in eomes was sustained in effectors from mice infected with the high virus dose (Fig. 5D). Although the role of T-bet and eomes under these conditions is not fully elucidated from these studies, the altered expression of these molecules in effectors from mice infected with the high versus low virus dose is in agreement with the differential regulation of effector differentiation observed. Further, the reduced expression of T-bet at d5 in the high dose infected animals is consistent with a reduced presence of SLEC over time.

Figure 5. Effector cells from mice infected with the high virus dose exhibit decreased levels of T-bet at d5 p.i.

C57BL/6 mice were infected with either a high or low dose of vaccinia virus. On d5 (A and B) and d6 (C and D) p.i., splenocytes were isolated and CD8+B8R+ SLEC, MPEC, and EEC assessed for expression of eomes and T-bet. For each virus dose, results are the average of 6–7 mice analyzed in two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.005, ***=p<0.001). Significance testing was performed across the two virus doses.

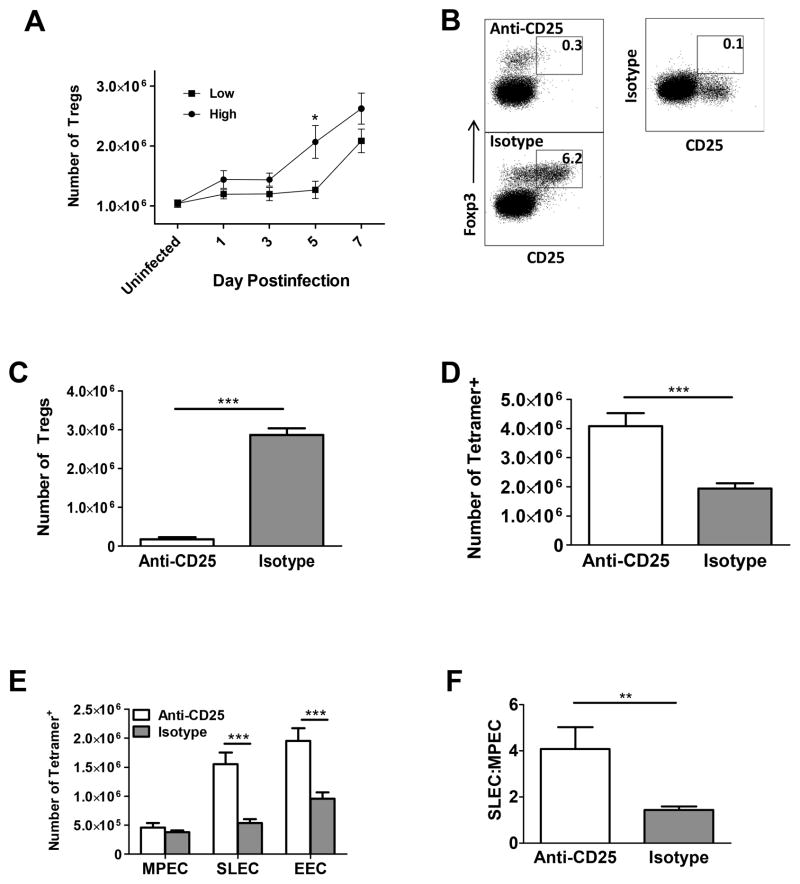

nTreg control SLEC number in mice infected with high dose virus

Recent evidence points to the indirect contribution of nTreg to effector cell differentiation through regulation of IL-2 present in the environment (20). As a first step in evaluating the potential for nTreg to play a role in control of the SLEC pool following infection with vaccinia virus, Treg number was analyzed over the course of infection. A significant increase in the number of nTreg was observed at d5 in mice that received the high virus dose, resulting in a significantly higher number of nTreg in mice infected with the high versus low virus dose (Fig. 6A). The timeframe for nTreg increase coincided with the reduced relative expansion of B8R+ cells in high vs. low dose infected animals. Expansion of nTreg in low dose infected mice was not observed until later in the response (day 7) (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. nTreg control SLEC number in mice infected with high dose virus.

(A) C57BL/6 mice were infected with either a high or low dose of vaccinia virus. The number of CD25+FoxP3+ Treg present over d1-7 following infection was determined. (B–F) Mice infected with the high virus dose were treated with 400μg of anti-CD25 or isotype control antibody one day prior to infection. On d7 p.i. nTreg were analyzed. (B) Representative dot plot and (C) average number of nTreg present in treated mice. (D) Total number of B8R-specific cells. (E) Effector cell numbers and (F) ratio of SLEC to MPEC following anti-CD25 or isotype antibody treatment. Data shown for (A) are an average of 10 mice from d1-3, at least 6 mice from d5-7 analyzed in a minimum of 2 independent experiments. For figures B–F, data are an average of at least 9 mice from 4 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001).

To determine whether the increased number of nTreg was involved in regulating SLEC number in animals infected with the higher virus dose, nTreg were depleted by administration of anti-CD25 or isotype control antibody one day prior to infection. Injection with anti-CD25 resulted in significant depletion of CD25+FoxP3+ cells (Fig. 6B and C). Consistent with previously published data that show nTreg mediated suppression of the B8R specific response (17), mice depleted of nTreg showed a significant increase in the number of B8R-specific cells (Fig. 6D). Concomitant with the increase in the antigen specific cells was an increase in the SLEC population (Fig. 6E) that resulted in skewing of the B8R-specific response towards SLEC (Fig. 6F). There was no significant increase in the number of MPEC (Fig. 6E). As CD25 is also expressed on activated T cells, administration of anti-CD25 antibody could potentially impact these cells. To ensure that the results we obtained were not due to direct effects on activated T cells, we treated mice with anti-FR4 antibody, an alternative approach for the depletion of nTreg (26). The results from these studies were similar to those obtained following anti-CD25 treatment (supplemental Fig. 1). Together, these data show that the presence of increased nTreg following infection with high virus dose resulted in a reduced SLEC population.

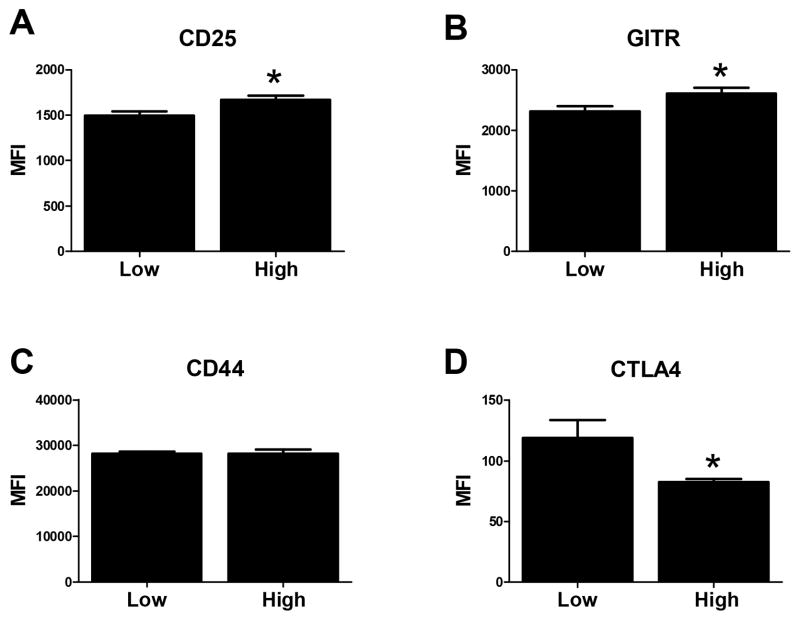

nTreg generated following infection with the high virus dose exhibit increased expression of the activation markers CD25 and GITR and decreased expression of CTLA4

Given the increased number of nTreg in mice infected with the high virus, we were interested to determine whether these nTreg exhibited differential expression of markers known to be involved in nTreg function/proliferation. To this end we assessed the expression of CD25, CD44, GITR, and CTLA4. nTreg from mice infected with the high virus dose had significant increases in CD25 and GITR (Fig. 7A and B), while the level of CTLA4 expressed on these cells was decreased (Fig. 7D). No difference in CD44 was observed (Fig. 7C). IL-2 signaling and GITR engagement are known to be associated with increased survival/proliferation/function of nTreg (27–29). In contrast, CTLA4 engagement results in decreased proliferation of these cells (30,31). Thus, the differential expression pattern of these markers on nTreg from the high dose infected mice is consistent with their increased number and function.

Figure 7. nTreg from mice infected with the high virus dose exhibit increased levels of CD25 and GITR, but decreased CTLA4.

On d6 following infection, nTreg identified by staining with CD4 and FoxP3 were assessed for the expression of CD25 (A), GITR (B), CD44 (C), and CTLA4 (D). The data are generated from 7–8 individual animals analyzed across 2 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (*p< 0.05).

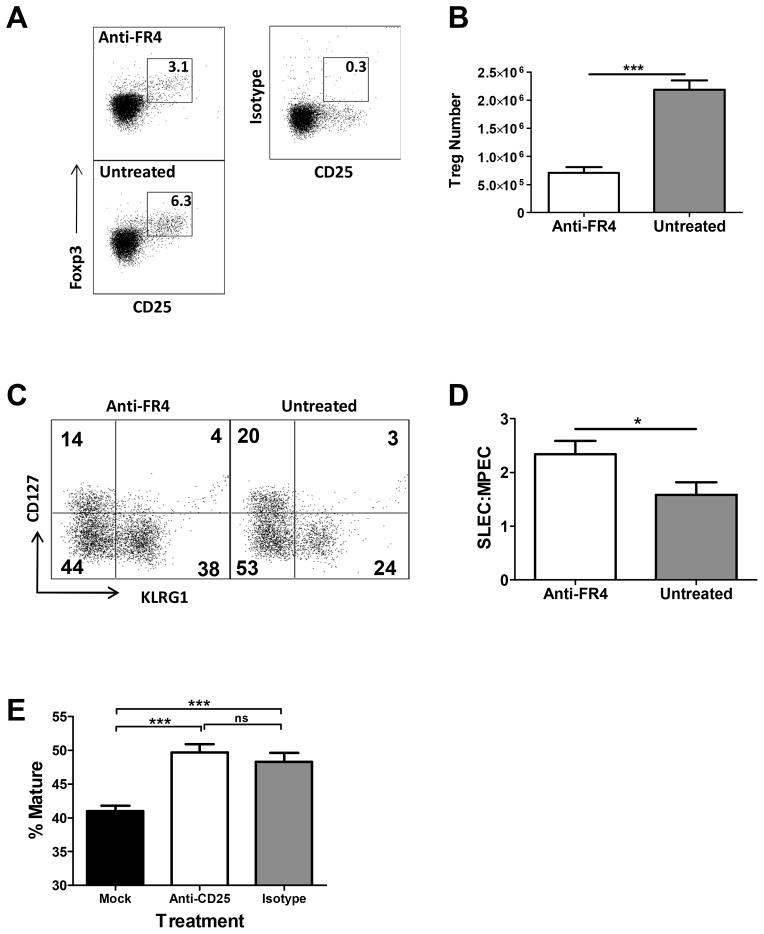

Late depletion of nTreg resulted in an increased SLEC:MPEC ratio

Our analysis of the emergence of SLEC following infection with high vs. low dose virus was consistent with a late effect of nTreg cells, i.e. skewing did not occur until day ≥6 p.i. (Fig. 3). Based on this result, we hypothesized that depletion of nTreg at a post-priming stage would still promote an increased SLEC:MPEC skewing similar to that observed in mice infected with the high virus dose that were depleted of nTreg prior to infection. To determine if this were the case, we administered anti-FR4 antibody at d2.5 p.i. We chose this approach to minimize potential effects of administering anti-CD25 antibody during the activation and proliferation stages of the T cell response when activated T cells also express high levels of CD25. Treatment of mice with anti-FR4 at day 2.5 resulted in a decreased number of Treg at d7 p.i. (Fig. 8A and B). Further, depletion of nTreg led to a significant increase in the SLEC population (Fig. 8C and data not shown) and as a result increased skewing within the population towards SLEC (Fig. 8D). A previous study reported that nTreg could decrease SLEC via inhibition of DC maturation (32). However, in agreement with the late stage effect of nTreg on the SLEC number in our model, nTreg depletion had no significant effect on the maturation of DC following infection with the high virus dose (Fig. 8E).

Figure 8. nTreg regulate SLEC number at a step subsequent to priming of the CD8+ T cell response.

C57BL/6 mice were infected with a high dose of vaccinia virus i.p. On day 2.5 after infection mice were treated with 30μg of anti-FR4 antibody. Responses were analyzed on d7p.i. (A) Representative dot plot of CD25 and FoxP3 staining following pre-gating on CD4+ T cells. (B) Number of nTreg in mice treated with anti-FR4 antibody versus untreated mice. (C) Representative dot plot of B8R+CD8+ T cells in untreated mice or in mice that received anti-FR4 antibody following staining with KLRG1 and CD127 antibodies. (D) Ratio of SLEC:MPEC within the B8R+CD8+ T cell population in treated vs. untreated animals. Data shown are the average of 6 animals analyzed in 2 independent experiments. (E) Mice received PC61 antibody on d1 prior to infection with the high virus dose. On d2 p.i., the time at which DC demonstrate maximal maturation in our preliminary studies, dendritic cells in the spleen were assessed for the expression of CD80 and CD40 as indicators of maturation. The percentage of mature CD11c+ cells is shown. Data shown are the average of at least 8 animals analyzed in 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test except in Fig 8C where a one tailed t-test was used. (*=p<0.05, ***=p ≤ 0.0005).

IL-2 administration at late times following infection with the high virus dose increased SLEC expansion and resulted in an SLEC:MPEC ratio similar to that observed in mice infected with the low virus dose

nTreg constitute a major consumer of IL-2 within the immune responders. If the generation of high numbers of nTreg as a result of high viral burden were limiting late stage SLEC by decreasing available IL-2, administration of this cytokine should restore SLEC. To determine if this were the case, high dose infected mice received 15,000 IU of recombinant human IL-2 twice daily on days 3–6 p.i. The data in figure 9A and B show that this treatment resulted in an increased frequency and number of B8R-specific cells on d7 p.i. Further, mice that received IL-2 had an increased frequency of SLEC (Fig. 9C) that resulted in an SLEC:MPEC ratio similar to that observed in mice infected with the low virus dose (Fig. 9D, compare to Fig. 1D). Taken together, these data suggest that increased vaccinia virus burden resulted in increased nTreg, which in turn decreased SLEC number through consumption of IL-2.

Figure 9. Late treatment with recombinant IL-2 results in SLEC skewing of the virus-specific CD8+ T cell response.

C57BL/6 mice were infected with a high dose of vaccinia virus i.p. On days 3–6 p.i., mice received a twice daily injection of recombinant IL-2. On day 7 p.i., the B8R-specific population present in the spleen was assessed. (A) Representative dot plots showing the frequency of B8R positive CD8+ T cells in mice treated with IL-2 versus mock treated animals. (B) Averaged data showing the total number of B8R specific CD8+ T cells. (C) Representative dot plot of B8R+CD8+ T cells stained with anti-KLRG1 and anti-CD127 antibodies following IL-2 treatment. (D) The SLEC:MPEC within the B8R-specific population. Data shown are the average of at least 12 animals analyzed in 5 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (*=p<0.05).

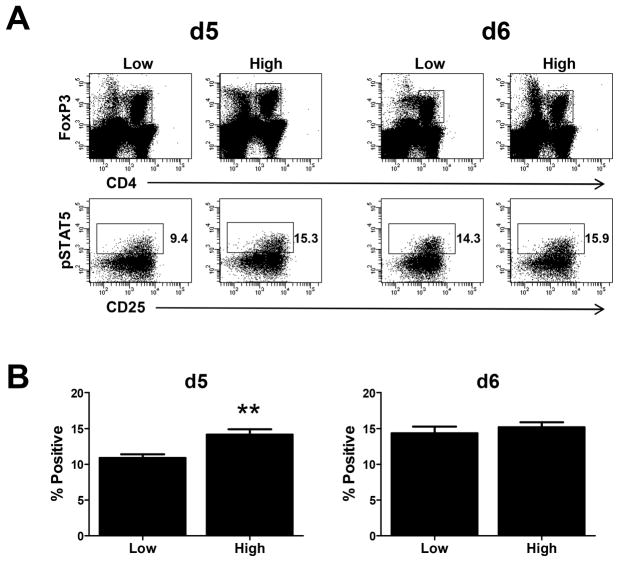

nTreg present at d5 in mice infected with high virus dose exhibit increased pSTAT5 compared to mice infected with low virus dose

The above data are consistent with the model that IL-2 utilization by nTreg limits cytokine availability for use by CD8+ effectors. Thus we reasoned that nTreg present in the animals infected with the high virus dose should exhibit evidence of increased IL-2 receptor engagement. To test this possibility, phosphorylation of STAT5 was measured following fixation immediately following spleen isolation as previously described (33). We assessed two timepoints, d5 and d6 p.i. At d5 following infection, a significantly higher percentage of nTreg from high dose infected animals were positive for pSTAT5 staining compared to the low dose counterpart (Fig. 10). Interestingly by d6, nTreg from high and low dose infected animals showed similar levels of pSTAT5. The increased phosphorylation of STAT5 in nTreg present at d5 following infection with the high dose of virus, a timepoint at which B8R+ effectors from the low but not high dose infected animals underwent robust expansion, supports the model of increased consumption of IL-2 by these cells compared to nTreg present in animals infected with the low virus dose.

Figure 10. nTreg from mice infected with the high virus dose exhibit increased levels of pSTAT5.

On d5 or d6 p.i., spleens from infected animals were isolated and immediately fixed in 1.6% formaldehyde followed by methanol permeabilization. pSTAT5 levels were assessed in CD4+FoxP3+ cells by staining with antibody specific to pSTAT5. Representative data are shown in A. Averaged data are shown in B. Data for each timepoint and condition are generated from 11 individual animals analyzed across 4 experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s two tailed t-test. (**, p= 0.002).

DISCUSSION

The expansion of effector cells following virus infection is a critical determinant of effective clearance. Here we report the finding that viral burden dictates the nature of the CD8+ effector T cell response with regard to both number and differentiation state. Paradoxically, high viral load following vaccinia virus infection resulted in a decreased number of SLEC within the responding effector cell pool. This constraint on the effector cell response was the result of nTreg mediated restriction of the SLEC population. The regulation of the effector cell response was selective for SLEC, as MPEC numbers were similar regardless of viral burden. Modulation of this population resulted in a skewing of the response toward SLEC in animals infected with the high virus dose. The skewing was a late event, as it was not apparent until d6 p.i.

We reasoned that the increase in SLEC number following low dose infection was potentially due to selective expansion of SLEC in low dose infected mice. However, while we found a greater percentage of SLEC were undergoing proliferation in mice infected with the low vs. high virus dose, MPEC and EEC populations exhibited a similar increase in proliferating cells. Thus selective proliferation of SLEC could not account for the increase in cell number.

The decreased number of SLEC in animals infected with the high dose was also not the result of increased death as measured by the presence of active caspase 3. Thus one possibility to explain the increased number of SLEC is increased differentiation of effectors along this pathway in mice infected with the low virus dose, i.e. a greater percentage of the dividing cells differentiate into SLEC. The increased level of T-bet in the effectors present at d5 following infection with the low virus dose is consistent with this model. That said, these effectors also showed increased levels of eomes. It is becoming increasingly clear that the regulation of eomes and T-bet as it relates to KLRG1hi vs. KLRG1lo expression is complex. Recently, elegant work has demonstrated the presence of further differentiation states within KLRG1hi vs. KLRG1lo populations that diverge in the relative expression of T-bet and eomes (34). In addition, the expression of T-bet and eomes within KLRG1 high vs. low lung effectors does not follow the expected pattern (35). The role of the differential T-bet and eomes expression in the SLEC skewing observed in our system will require further study.

The increased proliferation observed in EEC and MPEC populations, even though the number of these cells was not increased in mice infected with the low vs. high virus dose, is consistent with EEC, and perhaps MPEC, serving as sources of SLEC that are generated at later times p.i. While EEC are known to be efficient progenitors of SLEC (36), MPEC can also give rise to all three populations (36). One possibility is that a subpopulation of MPEC has the capacity to be shunted into the SLEC pathway directly or via an EEC intermediate. As MPEC contain two subsets that are thought to give rise to TEM vs. TCM (37), it is tempting to speculate that these two subsets differ with regard to the potential to undergo further differentiation during the acute response. One might speculate that the TEM generating subset can give rise to SLEC in the acute response, as increased IL-2 signaling results in increased TEM generation similar to its effect on SLEC generation (8,38). This fits with our model suggesting increased IL-2 availability in the animals infected with low virus dose.

nTreg are well established as important players in suppressing potentially damaging self-reactive T cell response (for review see (39)). However, an increasing body of literature now supports their role in suppressing the immune response following viral infections, e.g. VV (17), HIV (40,41), HSV (18,19,40), HCV (40,42). Viral load appears to be an important regulator of Treg number as, for example, antiviral treatment during acute hepatitis B infection resulted in decreased nTreg that correlated with decreased virus load (43,44). This is potentially through increased production of IL-2, which promotes nTreg expansion and suppressive function (33). Based on this finding, we propose the increased nTreg generation observed in our study in mice infected with the high compared to low vaccinia virus dose is the result of increased virus burden.

The regulated expansion of nTreg in our model plays a critical role in determining effector cell fate as their presence at high numbers was associated with a decreased SLEC population. We found that depletion of nTreg resulted in an increase in the number of SLEC comparable to that observed in mice infected with low dose virus. This appeared to occur through modulation of IL-2 availability as administration of IL-2 resulted in a larger SLEC population. The consumption of IL-2 by nTreg in mice infected with the high virus dose is supported by our finding that a larger proportion of nTreg from these mice were positive for phosphorylated STAT5 compared to the nTreg from mice infected with the low virus dose. nTreg posses a unique ability to “starve” expanding T cells of IL-2 due to constitutive high level expression of CD25 (20), thereby preventing IL-2 signaling that is known to be a critical signal for shunting effectors to the SLEC pathway (8,45), presumably through its ability to sustain Blimp-1 expression (45).

A role for nTreg in the regulation of SLEC has been recently reported (32). The basis for this effect following infection with replication incompetent MVA was identified as a Treg mediated decrease in DC maturation. Thus, nTreg altered effector cell generation at the priming stage. Our studies reveal an alternative strategy utilized by nTreg to alter SLEC number in the presence of high viral load. Here regulation occurred at a kinetically distinct phase of the immune response, i.e. late expansion. The late nature of this effect was demonstrated by increased SLEC number as a result of delivery of IL-2 at d3-6 p.i. as well as depletion of nTreg following administration of anti-FR4 at d2.5 p.i., a strategy that should delete Treg at ≥ d3 p.i. The late effect on T cells in our model is also supported by the observed similarity in DC maturation in the presence or absence of Treg. Thus nTreg can impact CD8+ T cell effector fate via multiple mechanisms depending on the viral load.

In agreement with an effect at a post-priming stage, analysis of CD25 expression at d4 p.i. revealed significantly increased CD25 expression on SLEC in mice infected with the high vs. low dose of virus (data not shown). As high CD25 expression at this time is likely the result of positive feedback from sustained IL-2 signaling, nTreg seemed not to have limited T effector cell access to IL-2 at this timepoint. By d5, the increased CD25 expression on SLEC from mice infected with the high virus dose was no longer apparent, having fallen below that on SLEC from mice infected with the low virus dose (data not shown). The loss of CD25 expression at d5 coincided with a much higher number of nTreg. In addition, a higher percentage of these nTreg were positive for pSTAT5, an indicator of IL-2 signaling, compared to their low dose counterpart (for review see (46)). We believe that the mechanism of Treg action is primarily through IL-2 as we found no difference in the level of TGFβ or IL-10 in mice infected with the high vs. low dose of virus (data not shown).

How then does low virus dose limit Treg expansion to promote maximal SLEC formation? Infection with the low virus dose resulted in a more limited T cell response through d5 postinfection. Given this, we would predict that IL-2 levels are relatively low. In a previous report by Benson et al., limited IL-2 levels was shown to have a more profound effect on Treg compared to effector T cell generation (47). Thus, limiting IL-2 at early times postinfection as a result of low virus burden may allow preferential use of this cytokine in local cell environment by virus-specific T cells, thereby limiting Treg expansion that would subsequently suppress the SLEC population.

In summary, our data show that the viral burden present following poxvirus infection has a significant effect on the regulation of CD8+ effector T cell number and fate. In contrast to what might be expected, high vaccinia virus load resulted in reduced SLEC, a cell type known to be enhanced by the presence of inflammatory cytokines. Together these data reveal a novel mechanism by which viral load impacts SLEC number as a result of increased nTreg that appear to limit SLEC access to IL-2 at late stages of the immune response.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jason Grayson and Purnima Dubey for helpful comments on this manuscript. We thank the NIH Tetramer Facility for provision of tetramer.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 AI043591 (M.A. A.-M.).

Reference List

- 1.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: Implications for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nri778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huster KM, Busch V, Schiemann M, Linkemann K, Kerksiek KM, Wagner H, Busch DH. Selective expression of IL-7 receptor on memory T cells identifies early CD40L-dependent generation of distinct CD8+ memory T cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5610–5615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308054101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voehringer D, Blaser C, Brawand P, Raulet DH, Hanke T, Pircher H. Viral infections induce abundant numbers of senescent CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4838–4843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8+ T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarkar S, Kalia V, Haining WN, Konieczny BT, Subramaniam S, Ahmed R. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J Exp Med. 2008;205:625–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalia V, Sarkar S, Subramaniam S, Haining WN, Smith KA, Ahmed R. Prolonged interleukin-2Ralpha expression on virus-specific CD8+ T cells favors terminal-effector differentiation in vivo. Immunity. 2010;32:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui W, Joshi NS, Jiang A, Kaech SM. Effects of Signal 3 during CD8 T cell priming: Bystander production of IL-12 enhances effector T cell expansion but promotes terminal differentiation. Vaccine. 2009;27:2177–2187. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pham NL, V, Badovinac P, Harty JT. A default pathway of memory CD8 T cell differentiation after dendritic cell immunization is deflected by encounter with inflammatory cytokines during antigen-driven proliferation. J Immunol. 2009;183:2337–2348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keppler SJ, Theil K, Vucikuja S, Aichele P. Effector T-cell differentiation during viral and bacterial infections: Role of direct IL-12 signals for cell fate decision of CD8(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1774–1783. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox MA, Harrington LE, Zajac AJ. Cytokines and the inception of CD8 T cell responses. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:287–296. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells in the control of immune pathology. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:816–822. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haeryfar SM, DiPaolo RJ, Tscharke DC, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Regulatory T cells suppress CD8+ T cell responses induced by direct priming and cross-priming and moderate immunodominance disparities. J Immunol. 2005;174:3344–3351. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suvas S, Kumaraguru U, Pack CD, Lee S, Rouse BT. CD4+CD25+ T cells regulate virus-specific primary and memory CD8+ T cell responses. J Exp Med. 2003;198:889–901. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suvas S, Azkur AK, Kim BS, Kumaraguru U, Rouse BT. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control the severity of viral immunoinflammatory lesions. J Immunol. 2004;172:4123–4132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNally A, Hill GR, Sparwasser T, Thomas R, Steptoe RJ. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control CD8+ T-cell effector differentiation by modulating IL-2 homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7529–7534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103782108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badovinac VP, Porter BB, Harty JT. Programmed contraction of CD8+ T cells after infection. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:619–626. doi: 10.1038/ni804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Heijst JW, Gerlach C, Swart E, Sie D, Nunes-Alves C, Kerkhoven RM, Arens R, Correia-Neves M, Schepers K, Schumacher TN. Recruitment of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in response to infection is markedly efficient. Science. 2009;325:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.1175455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitton JL, Sheng N, Oldstone MB, McKee TA. A “string-of-beads” vaccine, comprising linked minigenes, confers protection from lethal-dose virus challenge. J Virol. 1993;67:348–352. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.348-352.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blattman JN, Grayson JM, Wherry EJ, Kaech SM, Smith KA, Ahmed R. Therapeutic use of IL-2 to enhance antiviral T-cell responses in vivo. Nat Med. 2003;9:540–547. doi: 10.1038/nm866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefrancois L, Obar JJ. Once a killer, always a killer: from cytotoxic T cell to memory cell. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:206–218. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi T, Hirota K, Nagahama K, Ohkawa K, Takahashi T, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of immune responses by antigen-specific regulatory T cells expressing the folate receptor. Immunity. 2007;27:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Olffen RW, Koning N, van Gisbergen KP, Wensveen FM, Hoek RM, Boon L, Hamann J, van Lier RA, Nolte MA. GITR triggering induces expansion of both effector and regulatory CD4+ T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182:7490–7500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de la RM, Rutz S, Dorninger H, Scheffold A. Interleukin-2 is essential for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell function. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2480–2488. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thornton AM, Piccirillo CA, Shevach EM. Activation requirements for the induction of CD4+CD25+ T cell suppressor function. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:366–376. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker LS, Sansom DM. The emerging role of CTLA4 as a cell-extrinsic regulator of T cell responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:852–863. doi: 10.1038/nri3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang AL, Teijaro JR, Njau MN, Chandran SS, Azimzadeh A, Nadler SG, Rothstein DM, Farber DL. CTLA4 expression is an indicator and regulator of steady-state CD4+ FoxP3+ T cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:1806–1813. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kastenmuller W, Gasteiger G, Subramanian N, Sparwasser T, Busch DH, Belkaid Y, Drexler I, Germain RN. Regulatory T cells selectively control CD8+ T cell effector pool size via IL-2 restriction. J Immunol. 2011;187:3186–3197. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Gorman WE, Dooms H, Thorne SH, Kuswanto WF, Simonds EF, Krutzik PO, Nolan GP, Abbas AK. The initial phase of an immune response functions to activate regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:332–339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joshi NS, Cui W, Dominguez CX, Chen JH, Hand TW, Kaech SM. Increased numbers of preexisting memory CD8 T cells and decreased T-bet expression can restrain terminal differentiation of secondary effector and memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4068–4076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye F, Turner J, Flano E. Contribution of pulmonary KLRG1high and KLRG1low CD8 T cells to effector and memory responses during influenza virus infection. J Immunol. 2012;189:5206–5211. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obar JJ, Jellison ER, Sheridan BS, Blair DA, Pham QM, Zickovich JM, Lefrancois L. Pathogen-induced inflammatory environment controls effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2011;187:4967–4978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obar JJ, Lefrancois L. Early events governing memory CD8+ T-cell differentiation. Int Immunol. 2010;22:619–625. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obar JJ, Lefrancois L. Early signals during CD8 T cell priming regulate the generation of central memory cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:263–272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lourenco EV, La Cava A. Natural regulatory T cells in autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:33–42. doi: 10.3109/08916931003782155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rouse BT, Sarangi PP, Suvas S. Regulatory T cells in virus infections. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:272–286. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss L, Donkova-Petrini V, Caccavelli L, Balbo M, Carbonneil C, Levy Y. Human immunodeficiency virus-driven expansion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells, which suppress HIV-specific CD4 T-cell responses in HIV-infected patients. Blood. 2004;104:3249–3256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boettler T, Spangenberg HC, Neumann-Haefelin C, Panther E, Urbani S, Ferrari C, Blum HE, von WF, Thimme R. T cells with a CD4+CD25+ regulatory phenotype suppress in vitro proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7860–7867. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7860-7867.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nan XP, Zhang Y, Yu HT, Sun RL, Peng MJ, Li Y, Su WJ, Lian JQ, Wang JP, Bai XF. Inhibition of viral replication downregulates CD4highCD25high regulatory T cells and Programmed Death-Ligand 1 in chronic Hepatitis B. Viral Immunol. 2012;25:21–28. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.TrehanPati N, Kotillil S, Hissar SS, Shrivastava S, Khanam A, Sukriti S, Mishra SK, Sarin SK. Circulating Tregs correlate with viral load reduction in chronic HBV-treated patients with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:509–520. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pipkin ME, Sacks JA, Cruz-Guilloty F, Lichtenheld MG, Bevan MJ, Rao A. Interleukin-2 and inflammation induce distinct transcriptional programs that promote the differentiation of effector cytolytic T cells. Immunity. 2010;32:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng G, Yu A, Malek TR. T-cell tolerance and the multi-functional role of IL-2R signaling in T-regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2011;241:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benson A, Murray S, Divakar P, Burnaevskiy N, Pifer R, Forman J, Yarovinsky F. Microbial infection-induced expansion of effector T cells overcomes the suppressive effects of regulatory T cells via an IL-2 deprivation mechanism. J Immunol. 2012;188:800–810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.