Abstract

Context

Reduction in emergency department (ED) utilization is frequently viewed as a potential source for cost savings. One consideration has been to propose denying payment if the patient’s diagnosis upon ED discharge appears to reflect a “non-emergency” condition. This approach does not incorporate other clinical factors such as chief complaint that may inform necessity for ED care.

Objective

To determine whether ED presenting complaint and ED discharge diagnosis correspond sufficiently to support use of discharge diagnosis as the basis for policies discouraging ED use.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The New York University emergency department algorithm (EDA) has been commonly used to identify “non-emergency” ED visits. We applied the EDA to publicly available ED visit data from the 2009 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) for the purpose of identifying all “primary care treatable” visits. For each visit with a discharge diagnosis classified as “primary care treatable” we identified the chief complaint. To determine whether these chief complaints correspond to “non-emergency” ED visits, we then examined all ED visits with this same group of chief complaints to ascertain the ED course, final disposition, and discharge diagnoses.

Main Outcome Measures

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and disposition associated with chief complaints related to ”non-emergency ” ED visits.

Results

Although only 6.3% (95% CI 5.8–6.7) of visits were determined to have “primary care treatable diagnoses” based on discharge diagnosis and our modification of the EDA, the chief complaints reported for these ED visits with “primary care treatable” ED discharge diagnoses were the same chief complaints reported for 88.7% (95% CI 88.1–89.4) of all ED visits. Of these visits, 11.1% (95% CI 9.3–13.0) were identified at triage as needing immediate or emergent ED care; 12.5% (95% CI 11.8–14.3) required hospital admission; and 3.4% (95% CI 2.5–4.3) of admitted patients went directly from the ED to the operating room.

Conclusions

Among ED visits with the same presenting complaint as those ultimately given a “primary care treatable” diagnosis based on ED discharge diagnosis, a substantial proportion required immediate emergency care or hospital admission. The limited correspondence between presenting complaint and ED discharge diagnoses suggests that these discharge diagnoses are unable to accurately identify ”non-emergency” ED visits.

CONTEXT

With increasing medical care costs, policy-makers have turned to emergency department (ED) utilization as a potential source for cost savings. Although the assumptions driving this policy approach are unproven,1 recent attempts to reduce ED use have occurred in Medicaid programs.2–6 If implemented for patients in Medicaid programs, it is likely that such practices may result in similar policies by other payers, potentially affecting access to ED care for other segments of the population.

One approach aimed at reducing ED use has been to deny or limit payment if the patient’s diagnosis on discharge from the ED appears to reflect a “non-emergency” condition. 3,7,8 Legislatures or regulators in Tennessee, Iowa, New Hampshire, and Illinois have considered or enacted legislation or regulations that would limit payment for “non-emergency” ED visits by Medicaid enrollees, based on discharge diagnosis. Other states, including Arizona, Oregon, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, North Carolina, and New Mexico, have recently implemented or considered implementation of some level of copayment requirement for non-emergency use of the ED (personal communications, Craig Price, American College of Emergency Physicians; April 13, 2012 and February 11, 2013). Although criteria for determining “non-emergency” ED visits vary by state and no systematic review of states’ practices is available, Washington State recently drew attention for a proposal in which the payer may make a determination about payment based only on the ED discharge diagnosis and whether the patient is hospitalized during the ED visit, without other clinical information,9 and other states appear to have similar practices. For this approach to be effective at reducing “non-emergency” ED use without discouraging ED use for more serious conditions, it would be necessary to predict discharge diagnosis based on information available before the patient is seen in the ED – i.e., based on presenting symptoms. Many have questioned whether this approach is possible. For example, a 65-year-old patient with diabetes may be discharged with the “non-emergency” diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux after presenting with a chief complaint of chest pain; however, that patient still required an emergency evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome. In addition, there is concern that this approach may violate the prudent layperson standard, which establishes the “criteria that insurance coverage is based not on ultimate diagnosis, but on whether a prudent person might anticipate serious impairment to his or her health in an emergency situation.” 10

The purpose of this study was to determine the correspondence between ED presenting complaint and ED discharge diagnosis

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected in the 2009 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). As described by its developers, “The NHAMCS is an annual, national probability sample of ambulatory visits made to non-federal, general, and short-stay U.S. hospitals conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Although the survey includes visits to selected ambulatory care departments, this analysis focuses solely on the visits to hospital emergency departments (EDs). The multi-staged sample design is comprised of a three stages for the ED component: 1) 112 geographic primary sampling units (PSUs); 2) approximately 480 hospitals within PSUs; and 3) patient visits within emergency service areas.”11 Per NHAMCS protocol, trained hospital staff members abstract ED visit data using a structured data entry form during 4-week data periods randomly assigned for each sampled hospital. The sampled data are extrapolated to national estimates through use of assigned patient visit weights, which account for probability of visit selection, nonresponse, and ratio of sampled hospitals to hospital universe. The study was exempt from review by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco.

Key Variables

ED visit with “primary care treatable diagnosis” based on ED discharge diagnosis

We sought a method for identifying “non-emergency” ED visits that would maximize the probability of successfully classifying such visits based on the ED discharge diagnosis. Although the process for defining “non-emergency” diagnoses varies by state and various lists of “non-emergency” diagnoses have been proposed,12,13 many are based at least in part on the Emergency Department Algorithm (EDA) developed at New York University.14,15 Although the EDA was developed for other purposes and the EDA developers caution that “the algorithm is not intended as a triage tool or as a mechanism to determine whether ED use is appropriate for required reimbursement by a managed care plan,”15 it has been used by policymakers both to characterize “overuse” of EDs in several states (e.g., Connecticut16, Oregon17 and Massachusetts18) and, in modified form, as a basis for denying payment for ED visits in Washington State. 9,12

We selected the EDA as the basis for classifying “non-emergency” ED visits for this study, both because of its use for similar purposes and because its classification system is more evidence-based than others that have been proposed. The EDA was developed with input from emergency physicians and based on ED visit data abstracted from 5,700 ED visit records. After excluding visits for injuries, mental health, and drug- and alcohol-related conditions, physician reviewers used data including chief complaint, demographic data, duration of symptoms, presenting vital signs, and medical history to classify visits as “emergent” (requiring care in under 12 hours) or “non-emergent.” Emergency cases were then further categorized as “emergency, primary care treatable” or “emergency, ED needed,” based on whether the resources required during the ED visit (including radiology, blood work, etc.) are normally available in the outpatient setting, in the judgment of the algorithm’s creators. In addition, “ED needed” visits were categorized based on whether or not they were “preventable or avoidable” with timely and effective outpatient care. 15,19

The final step in the development of the EDA was designed to allow the EDA to be applied to administrative datasets. To do so, the above classifications were “mapped” to the discharge diagnoses for each case in the sample to determine the percentage of sample cases in each of the 4 categories for each diagnosis.14 As stated elsewhere, “For instance, multiple patients in the sample were discharged with ICD-9 code 789.00 (abdominal pain, unspecified site). All were deemed to require care within 12 hours and were classified as emergent. Two-thirds of these patients were managed with resources available in primary care settings, while one-third received interventions not available outside the ED. Therefore, the ICD-9 code 789.00 is assigned a 0.67 probability of emergency, primary care–treatable and a 0.33 probability of emergent, ED needed.”20

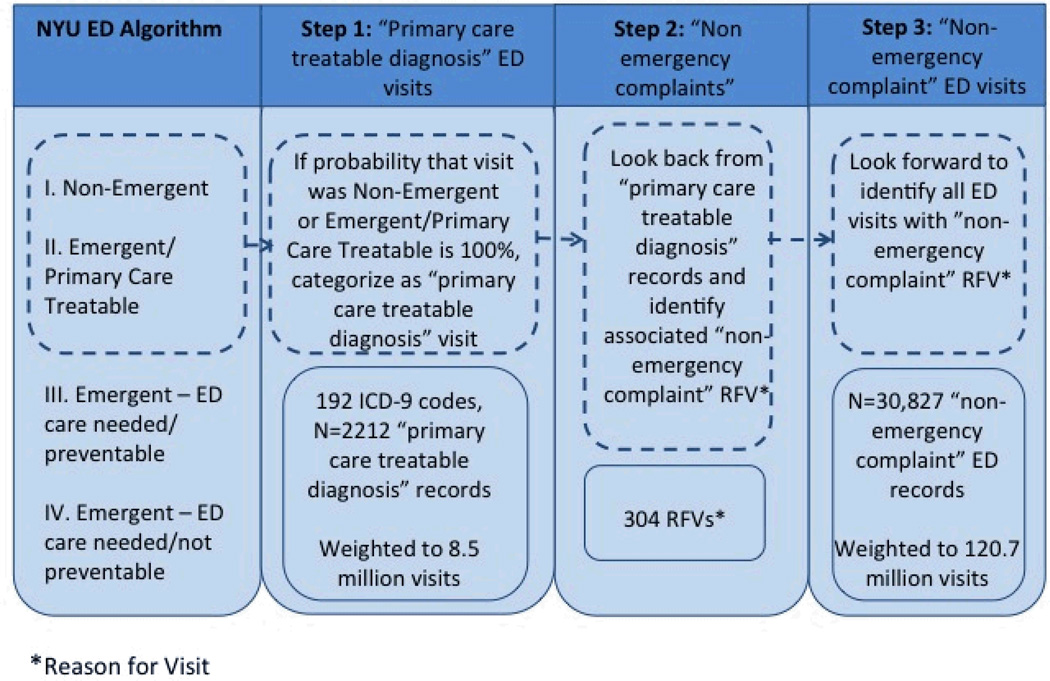

We used 2 additional strategies to maximize the probability that our classification system would identify only “non-emergency” ED visits. First, based on the ED discharge diagnosis, we classified a visit as “primary care treatable diagnosis” only if the EDA predicted that the probability of the diagnosis being primary care treatable was 100% (Figure 1, Step 1). This approach leads to a more limited number of “primary care treatable diagnoses” than that used by some other researchers.20–22 Second, because some policymakers have proposed only denying payment for visits after which the patient was discharged home, we excluded visits resulting in hospital admission. By eliminating these higher-acuity visits, we eliminated some of the higher-risk chief complaints associated with a diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for creation of “non-emergency complaint” ED visits based on NYU ED algorithm

Chief Complaints Associated with “non-emergency” ED visits

Because patients present to the ED with a chief complaint, not with a discharge diagnosis, our next step in identifying “non-emergency” visits was to determine what chief complaints were associated with the ”primary care treatable diagnoses” (Figure 1, Step 2). The NHAMCS database contains a field for the most important reason for visit (RFV), in which the patient’s chief complaint is coded according to a standardized classification system developed by the National Center for Health Statistics.23,24 This coding system is similar to ICD9-CM coding, in that it allows conversion of free-text data into a structured system. The RFV coding for chief complaints has been widely used by NCHS in NHAMCS and other surveys.25,26 At each hospital, triage nurses document the patient’s chief complaint per hospital protocol. Then, chart abstractors trained by the National Center for Health Statistics review the patient record and record the verbatim text, which is later classified as a chief complaint using RFV codes by an NCHS contractor. “As part of the quality assurance procedure, a 10 percent quality control sample of Patient Record Forms is independently keyed and coded. Error rates typically range between 0.3 and 0.9 percent for various survey items.”11

For all visits with “primary care treatable diagnoses,” based on the ED discharge diagnosis, we generated a list of RFVs. We then identified all ED visits in the dataset with RFVs identical to those on our list. These are referred to as ED visits with “non-emergency complaints” (Figure 1, Step 3). We chose the term, “non-emergency complaint” because, if it were possible to prospectively identify ED visits with diagnoses on the “primary care treatable diagnosis” list, the chief complaints resulting in these diagnoses might not require ED care.

Variables reflecting the acuity of “non-emergency complaint” ED visits

Next, for the group of ED visits with “non-emergency complaints” we identified diagnoses, disposition, and other key factors related to the patient’s initial presentation and ED course. Demographic variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance type, region, and urban/rural status. We also included triage categories defined on a scale of 1–5 by nursing staff as “immediate,” “emergent,” “urgent,” “semi-urgent,” or “non-urgent.”27 Triage vital signs were classified as normal or abnormal using standards based on published guidelines.28,29 Pain scale was by patient self-report on presentation, with a scale from 1–10, with 10 being the most severe. We also identified whether patients arrived by ambulance. We ascertained whether the visit resulted in hospital admission and, if so, whether the patient was admitted to an observation unit, to a standard bed or to a higher level of care. NHAMCS does not distinguish between observation unit stays occurring in the ED and those occurring in the inpatient facility. For the purposes of this analysis, we grouped observation unit stays with inpatient admissions, reasoning that an observation unit admission indicated a patient could not safely be discharged home.

Statistical Analysis

If presenting complaint corresponded closely with the discharge diagnosis, visits with “non-emergency complaints” based on the reasons for visit would be expected to correspond to visits with “primary care treatable diagnoses.” In this situation, the number of visits with “non-emergency complaints” would be similar to the number of visits with “primary care treatable diagnoses.” Conversely, if presenting complaint corresponded poorly with the discharge diagnosis, multiple chief complaints would be expected to be associated with each diagnosis and multiple diagnoses would be associated with each complaint. In this situation, the number of visits with “non-emergency complaints” would exceed the number of visits with “primary care treatable diagnoses.” Therefore, we compared the proportion of ED visits with “primary care treatable diagnoses” based on ED discharge diagnosis to the proportion ED visits with “non-emergency complaints” based on the reason for the visit. In addition, we calculated descriptive statistics for “non-emergency complaint” ED visits, presenting frequencies and proportions.

We report actual ED visits from the hospitals included in the NHAMCS sample, national estimates based on survey visit weights, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) based on standard errors provided by NHAMCS. The analyses follow recommendations on the NHAMCS website for using the sampling weights in the dataset to project, for all ED visits in the United States, the proportions with the specified characteristics. 11 Confidence intervals were calculated using standard methods for survey data collected with stratified sampling, based on weights provided by NHAMCS.30 All estimates conform to NCHS standards.11 Unweighted estimates based on less than 30 records are considered unreliable by NCHS and are marked by an asterisk. Estimates were sufficiently precise with a single year of data to avoid the need to combine multiple years of NHAMCS data, which would have added complexity to the analyses given changes in variable definitions (e.g., triage category) over time. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC) and SUDAAN (version 10.0; RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina).

RESULTS

The 2009 NHAMCS dataset contains 34,942 records, each representing a unique ED visit. Of these visits, an estimated 6.3% (95% CI 5.8–6.7) had “primary care treatable diagnoses” based on the ED discharge diagnosis and our modification of the EDA. However, the presenting complaints associated with the ED visits (i.e., “non-emergency complaints”) were also the presenting complaints for 88.7% (95% CI 88.1–89.4) of all ED visits, reflecting poor correspondence between ED discharge diagnosis and chief complaint.

These findings were similar for age-stratified subgroups. For children under age 18, 5.5 % (95% CI 4.7–6.3) had “primary care treatable diagnoses” and 90.0% (95% CI% 88.6–91.1) had “non-emergency complaints.” For adults age 65 and older, 3.2% (95% CI 2.8–3.8) had “primary care treatable diagnoses” and 86.9% (95% CI 85.8–88.1) had “non-emergency complaints.” (See eTables 1 and 2 for additional age-stratified results.)

Of the ED visits for chief complaints identical to chief complaints generated by the group of ED visits with “primary care treatable” diagnoses, 9.3% (95% CI 8.2–10.5) had an "emergent" triage category; 3.7% (95% CI 3.4–4.1) of patients had been seen in the same ED within the last 72 hours; and 2.1% (95% CI 1.7–2.5) had been discharged from a hospital within the past 7 days (Table 1). In addition, 79.7% (95% CI 78.2–81.3) had at least one abnormal triage vital sign recorded. Although the most common vital sign abnormalities were respiratory rate (61.8%, 95% CI 59.9–63.8) and blood pressure (34.2%, 95% CI 32.7–35.8), patients presented with abnormal heart rates at 21.8% (95% CI 20.8–22.8) of visits, were hypoxic at 6.6% (95% CI 5.3–7.9) of visits, and were either hypo- or hyperthermic at 6.1% (95% CI 5.5–6.7) of visits . The mode of arrival for 13.8 % (95% CI 12.8–14.8) of “non-emergency” patients was ambulance, and 38% (95% CI 35.9–40.1) reported pain scales ≥ 6 (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study population with original “primary care treatable” diagnosesa and “non-emergency complaint” ED visitsb, NHAMCS 2009

| “Primary care treatable” diagnoses | “Non-emergency complaint” ED visits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted No.c |

Weighted proportion,% |

(95% CI) | Unweighted No. |

Weighted proportion,% |

(95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||||

| <18 | 467 | 21.5 | (19.0–23.9) | 7,254 | 24.7 | (22.4–27.0) |

| 18–44 | 1,128 | 51.5 | (48.5–54.2) | 12,450 | 39.6 | (38.1–41.1) |

| 45–64 | 439 | 19.3 | (17.4–21.3) | 6,655 | 21.4 | (20.5–22.3) |

| 65–79 d | 111 | 4.5 | (3.4–5.6) | 2,680 | 8.6 | (8.1–9.2) |

| >80e | 67 | 3.1 | (2.3–4.0 | 1,788 | 5.6 | (5.2–6.1) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1,337 | 62.8 | (59.9–65.7) | 17,223 | 55.9 | (54.9–56.8) |

| Male | 875 | 37.2 | (34.3–40.1) | 13,604 | 44.1 | (43.2–45.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,199 | 56.3 | (52.0–60.6) | 17,777 | 59.1 | (55.2–63.0) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 606 | 28.1 | (23.5–32.6) | 7,151 | 22.8 | (19.1–26.4) |

| Hispanic | 96 | 3.1 | (2.1–4.2) | 1,293 | 3.7 | (2.4–5.0) |

| Other | 311 | 12.5 | (9.9–15.2) | 4,606 | 14.4 | (11.5–17.3) |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Private | 726 | 33.2 | (29.7–36.8) | 11,947 | 39.0 | (36.5–41.5) |

| Medicare | 153 | 6.7 | (5.4–8.0) | 3,319 | 10.5 | (9.6–11.3) |

| Medicaid | 689 | 32.2 | (29.0–35.4) | 7,908 | 25.3 | (23.0–27.6) |

| Uninsured/Self-pay | 423 | 18.8 | (16.2–21.5) | 4,701 | 15.6 | (13.9–17.3) |

| Other | 56 | 2.3 | (1.5–3.2) | 964 | 2.9 | (2.3–3.5) |

| Missing/unknown | 165 | 6.7 | (4.2–9.3) | 1,988 | 6.7 | (4.5–9.0) |

| Triage category | ||||||

| Immediate | 20* | 1.4 | (0.5–2.2) | 529 | 1.8 | (1.1–2.5) |

| Emergent d | 119 | 5.2 | (3.7–6.8) | 2,926 | 9.3 | (8.2–10.5) |

| Urgent d | 755 | 34.5 | (31.0–38.0) | 12,836 | 41.7 | (39.6–43.8) |

| Semi-urgent | 900 | 42.2 | (38.5–45.8) | 10,552 | 35.7 | (33.5–38.0) |

| Non-urgent d | 314 | 13.2 | (10.7–15.8) | 2,500 | 7.9 | (6.9–9.0) |

| Triage not conducted | 104 | 3.5 | (1.1–5.9) | 1,484 | 3.5 | (1.3–5.8) |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 559 | 17.2 | (13.5–20.9) | 7,856 | 18.0 | (14.1–21.9) |

| Midwest | 521 | 26.7 | (18.9–34.4) | 6,664 | 23.2 | (16.9–29.6) |

| South | 773 | 39.1 | (32.0–46.3) | 10,902 | 39.7 | (33.3–46.1) |

| West | 359 | 17.0 | (11.9–22.1) | 5,405 | 19.1 | (14.3–23.8) |

| Metropolitan Statistical Area | ||||||

| Urban | 1,848 | 80.2 | (69.6–90.8) | 26,245 | 82.0 | (72.3–91.6) |

| Rural | 364 | 19.8 | (9.2–30.4) | 4,582 | 18.0 | (8.4–27.7) |

| Seen within last 72 hours | ||||||

| Yes | 79 | 3.3 | (2.4–4.3) | 1,151 | 3.7 | (3.4–4.1) |

| No | 1,801 | 77.8 | (70.9–84.8) | 24,990 | 79.9 | (75.1–84.7) |

| Unknown | 332 | 18.9 | (11.7–26.0) | 4,686 | 16.4 | (11.6–21.2) |

| Discharged from hospital within last 7 days | ||||||

| Yes | 33 | 1.3 | (0.7–2.0) | 720 | 2.1 | (1.7–2.5) |

| No | 1,327 | 58.7 | (51.5–65.8) | 18,243 | 59.0 | (52.7–65.2) |

| Unknown | 852 | 40.0 | (32.7–47.3) | 11,864 | 39.0 | (32.7–45.3) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NHAMCS, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; ED, emergency department

Under 30 records, estimate considered imprecise by the National Center for Health Statistics

n=2,212 records, representing an estimated 8.5 million visits

n=30,827 records, representing an estimated 120.7 million visits

Number of records in the data set for each type of category (unweighted). Proportions, however, are calculated using survey weights.

indicates significant difference (non-overlapping 95% CI) between visits with “primary care treatable” diagnoses and “non emergency complaint” ED visits.

Table 2.

Severity of Illness Characteristics Associated with original “primary care treatable” diagnosesa and “non-emergency complaint” ED visitsb, NHAMCS 2009

| “Primary care treatable” diagnoses | “Non-emergency complaint” ED visits | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted No. c |

Weighted proportion, % |

(95% CI) | Unweighted No. c |

Weighted proportion, % |

(95% CI) | |

| Vital signsf | ||||||

| Respiratory Rate | ||||||

| Normal | 787 | 36.1 | (32.8–39.4) | 10,038 | 33.5 | (31.7–35.3) |

| Abnormal | 1,336 | 60.1 | (56.8–63.4) | 19,307 | 61.8 | (59.9–63.8) |

| Missing | 89 | 3.8 | (2.6–5.0) | 1,482 | 4.7 | (3.2–6.1) |

| Heart Rate | ||||||

| Normal d | 1,741 | 77.7 | (74.7–80.6) | 22,378 | 71.9 | (69.9–74.0) |

| Abnormal d | 343 | 16.1 | (14.0–18.3) | 6,605 | 21.8 | (20.8–22.8) |

| Missing | 128 | 6.2 | (3.3–9.0) | 1,844 | 6.2 | (3.8–8.7) |

| Blood Pressure | ||||||

| Normal d | 1,303 | 58.9 | (55.5–62.4) | 16,665 | 52.7 | (51.2–54.1) |

| Abnormal d | 642 | 28.5 | (25.6–31.5) | 10,302 | 34.2 | (32.7–35.8) |

| Missing | 267 | 12.6 | (10.3–14.8) | 3,858 | 13.1 | (11.3–14.9) |

| Pulse Oximetry | ||||||

| Normal | 1,769 | 78.8 | (74.5–83.2) | 24,337 | 77.5 | (74.1–81.1) |

| Abnormal | 76 | 3.7 | (1.9–5.5) | 1,904 | 6.6 | (5.3–7.9) |

| Missing | 367 | 17.5 | (13.3–21.7) | 4,586 | 15.9 | (12.5–19.3) |

| Temperature | ||||||

| Normal | 2,086 | 93.9 | (92.1–95.6) | 27,530 | 88.4 | (86.9–89.9) |

| Abnormal d | 47 | 2.0 | (1.3–2.6) | 1,745 | 6.1 | (5.5–6.7) |

| Missing | 79 | 4.2 | (2.4–6.0) | 1,552 | 5.5 | (4.0–7.0) |

| All vital signs | ||||||

| All normal | 285 | 12.6 | (10.5–14.7) | 3,265 | 10.4 | (9.5–11.2) |

| Any abnormal | 1,689 | 76.8 | (74.5–79.2) | 24,612 | 79.7 | (78.2–81.3) |

| All missing | 238 | 10.6 | (9.0–12.1) | 2,950 | 9.9 | (8.3–11.5) |

| Mode of arrival | ||||||

| Ambulance d | 116 | 5.8 | (4.3–7.2) | 4,289 | 13.8 | (12.8–14.8) |

| Other d | 1,975 | 88.5 | (86.2–90.8) | 25,000 | 81.2 | (80.0–82.5) |

| Missing/unknown | 121 | 5.8 | (4.3–7.2) | 1,538 | 5.0 | (3.8–6.2) |

| Pain scale | ||||||

| 0–5 | 802 | 34.8 | (30.7–38.8) | 11,906 | 38.0 | (35.7–40.3) |

| 6–10 | 899 | 41.3 | (37.6–45.0) | 11,623 | 38.0 | (35.9–40.1) |

| Missing | 511 | 23.9 | (19.6–28.2) | 7,298 | 24.0 | (20.6–27.4) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NHAMCS, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; ED, emergency department

n=2,212 records, representing an estimated 8.5 million visits

n=30,827 records, representing an estimated 120.7 million visits

Number of records in the data set for each type of category (unweighted). Proportions, however, are calculated using survey weights.

Indicates significant difference between the visits with “primary care treatable” diagnoses and “non emergency complaint” ED visits

Normal vital signs were adjusted for age and are based on published values from Rosen’s Emergency Medicine (RR, HR) and from EMS guidelines (BP) below. Values that fell outside (above or below) these ranges were considered abnormal. Abnormal temperature was defined as a recorded temperature above 38°C/100.4° F

| Age | RR (breaths/min) |

HR | |

| <1 | 30–60 | 100–160 | BP, mmHg |

| 1–2 | 24–40 | 90–150 | Neonates (−1–28d) =60 SBP |

| 2–5 | 22–34 | 80–140 | Infants (1mo–1yr)=70–90 SBP |

| 6–12 | 18–30 | 70–120 | Children (1y–8y)=70–95 SBP |

| Adult | 12–16 | 60–100 | Adults= 90–140 SBP, 60–90 DBP |

Regarding disposition of patients with “non-emergency complaint” ED visits, 12.5% (95% CI 11.8–14.3) were admitted to the hospital. Of admitted patients, 11.2% (95% CI 9.5–12.9) were admitted to a critical care unit, 22.9% (95% CI 18.4–27.4) required step-down or telemetry monitoring, 3.4% (95% CI 2.5–4.3) required the operating room, and 7.0% (95% CI 5.7–8.4) of the admissions were to an observation unit (Table 3).

Table 3.

Disposition and admitted patients location for “non-emergency complaint” ED visitsa, NHAMCS 2009

| “Non emergency complaint” ED visits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted No.b |

Weighted proportion, % |

(95% CI) | |

| Disposition | |||

| Admit to hospital or observation unit | 4,027 | 12.5 | (11.8–14.3) |

| Discharged | 25,190 | 82.4 | (81.1–83.7) |

| Left AMA | 261 | 0.7 | (0.6–0.9) |

| No answer | 423 | 1.4 | (1.2–1.6) |

| Transfer | 461 | 1.3 | (1.0–1.6) |

| Left before/after medical screening exam | 441 | 1.5 | (1.2–1.9) |

| DOA/died in ED | 24* | ‡ | ‡ |

| For admitted patients | |||

| Admitted patients location | |||

| Critical Care Unit | 413 | 11.2 | (9.5–12.9) |

| Stepdown/telemetry unit | 894 | 22.9 | (18.4–27.4) |

| Operating Room | 158 | 3.4 | (2.5–4.3) |

| Mental health/substance use detoxification | 103 | 1.8 | (1.1–2.6) |

| Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory | 26 | ‡ | ‡ |

| Other bed/unit | 1,677 | 40.5 | (36.8–44.3) |

| Observation unit | 325 | 7.0 | (5.7–8.4) |

| Location unknown | 431 | 12.5 | (9.1–16.0) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NHAMCS, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; ED, emergency department

Under 30 records, estimate considered imprecise by the National Center for Health Statistics

Confidence interval is not produced because there were only 24 people who died, and 26 people admitted to the cardiac catheterization laboratory.

n=30,827 records, representing an estimated 120.7 million visits

Number of records in the data set for each type of category (unweighted). Proportions, however, are calculated using survey weights.

There were 192 different “primary care treatable diagnoses” (eTable 3) and 304 “non-emergency complaints” (eTable 4) represented. “Unspecified disorder of the teeth and gums” was the most common “primary care treatable diagnosis” and accounted for 11.6% of ED visits with “primary care treatable diagnoses.” The 3 most common “non-emergency complaints” (Table 4) were toothache (10.05%), skin rash (5.99%), and abdominal pain, cramps, spasms (5.03%); other “non-emergency chief complaints” were as variable as skin itching, insect bite, ingrown nail, foreign body to eye, migraine headache, blood in stool, and symptoms of labor. For patients with “non-emergency complaint” ED visits, the 3 most common diagnoses identified were abdominal pain/unspecified site, acute respiratory infection, and chest pain/unspecified (Table 5).

Table 4.

10 most common reasons for visit (“non-emergency complaints”) associated with “primary care treatable diagnoses”a, NHAMCS 2009

| Reason For Visit | Unweighted Visit No.b |

Weighted proportion, % |

(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toothache | 202 | 10.05 | 7.92–12.18 |

| Skin rash | 139 | 5.99 | 4.67–7.31 |

| Abdominal pain, cramps, spasms, not otherwise specified | 102 | 5.03 | 3.77–6.29 |

| Earache, pain | 103 | 4.27 | 3.46–5.08 |

| Fever | 47 | 2.24 | 1.46–3.02 |

| Uterine and vaginal bleeding | 47 | 2.23 | 1.33–3.13 |

| Hip pain, ache, soreness, discomfort | 37 | 2.04 | 1.16–2.92 |

| Diarrhea | 49 | 1.93 | 1.19–2.67 |

| Chest pain | 34 | 1.75 | 0.86–2.64 |

| Other diseases of the skin | 29* | 1.51 | 0.90–2.12 |

| Other | 1423 | 62.96 | 60.28–65.62 |

| Total | 2212 | 100.0 | 100.0–100.0 |

Abbreviations: NHAMCS, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; ED, emergency department

Under 30 records, estimate considered imprecise by the National Center for Health Statistics

n=2,212 records, weighted 8.5 million visits

Number of records in the data set for each type of category

Table 5.

27 most common discharge diagnoses associated with “non-emergency complaint” ED visitsa, NHAMCS 2009

| Diagnosis | Unweighted Visit No.b |

Weighted proportion, % |

(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain, unspecified site | 1068 | 3.60 | 3.23–3.97 |

| Acute upper respiratory infections | 842 | 2.87 | 2.51–3.23 |

| Chest pain, unspecified | 862 | 2.75 | 2.41–3.09 |

| Sprains and strains, unspecified | 733 | 2.35 | 2.07–2.63 |

| Fever, unspecified | 535 | 2.04 | 1.65–2.43 |

| Left before seen/walked out/not seen | 594 | 1.99 | 1.60–2.38 |

| Urinary tract infection, unspecified | 535 | 1.71 | 1.52–1.90 |

| Unspecified otitis media | 500 | 1.67 | 1.37–1.97 |

| Headache | 468 | 1.53 | 1.33–1.73 |

| Missing | 258 | 1.49 | 0.19–2.79 |

| Other unknown and unspecified cause of morbidity and mortality | 443 | 1.46 | 1.24–1.68 |

| Pneumonia, organism unspecified | 396 | 1.37 | 1.17–1.57 |

| Acute pharyngitis | 405 | 1.34 | 1.18–1.50 |

| Backache, unspecified | 341 | 1.14 | 0.94–1.34 |

| Bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic | 286 | 1.02 | 0.81–1.23 |

| Head injury, unspecified | 297 | 1.00 | 0.81–1.19 |

| Other and unspecified noninfectious gastroenteritis and colitis | 319 | 0.99 | 0.82–1.16 |

| Lumbago | 303 | 0.98 | 0.82–1.14 |

| Syncope and collapse | 297 | 0.95 | 0.79–1.11 |

| Vomiting alone | 278 | 0.94 | 0.80–1.08 |

| Acute bronchitis | 290 | 0.92 | 0.73–1.11 |

| Influenza with other respiratory manifestations | 254 | 0.91 | 0.64–1.18 |

| 25 most common discharge diagnoses associated with “non-emergency complaint” ED visitsa, NHAMCS 2009 | |||

| Other cellulitis and abscess | 245 | 0.90 | 0.71–1.09 |

| Migraine, unspecified | 257 | 0.84 | 0.56–1.12 |

| Unspecified disorder of the teeth and supporting structures | 249 | 0.82 | 0.65–0.99 |

| Asthma, unspecified with acute exacerbation | 251 | 0.81 | 0.66–0.96 |

| Open wound of finger(s) | 247 | 0.80 | 0.65–0.95 |

Abbreviations: NHAMCS, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; ED, emergency department

n=30,827 records, representing an estimated 120.7 million visits

Number of records in the data set for each type of category

Because our analysis was conducted in aggregate, it was possible that a subset of “primary care treatable” diagnoses might be concordant with chief complaints and therefore appropriate targets for discouraging ED use. Therefore, we used the same techniques described above to analyze some of the most common primary care treatable diagnoses individually (unspecified disorder of the teeth and supporting structures, diarrhea, and esophageal reflux). Each of these common “primary care treatable” diagnoses was associated with 20 or more “non-emergency complaints.” In turn, these “non-emergency complaint” visits were associated with 29 to over 300 distinct discharge diagnoses with a wide range of clinical severity, consistent with our overall study findings.

COMMENT

Patients present to the ED with chief complaints, symptoms, and signs, but usually not with diagnoses. For a list of ED discharge diagnoses to be considered “non-emergency,” the ED discharge diagnoses must be predictable based on chief complaint information available at triage. Our study illustrates the challenges of mapping from discharge diagnosis to chief complaint. Although only 6.3% of ED visits had “primary care treatable” discharge diagnoses, the chief complaints reported for these visits encompassed 88.7% of all ED visits. If a triage nurse were to redirect patients away from the ED based on “non-emergency complaints,” 93% of the redirected ED visits would not have “primary care treatable diagnoses.” Adding vital signs to the decision rule would add little discriminatory power, because 79.7% of ED visits with “non-emergency complaints” had abnormal vital signs, including 76.8% of ED visits with “primary care treatable diagnoses” and 80.0% with other diagnoses.

These results highlight the flaws of a conceptual framework that fails to distinguish between information available at arrival in the ED and information available at discharge from the ED. The results call into question reimbursement policies that deny or limit payment based on discharge diagnosis. Attempting to discourage patients from using the ED based on the likelihood that they would have “non-emergency diagnoses” risks sending away patients who require emergency care.31–36 The majority of Medicaid patients, who stand to be disproportionately affected by such policies, visit the ED for “urgent or more serious” problems.37

Our results are in keeping with the original intention of the EDA. The EDA does not classify specific diagnoses as “non-emergency” or “primary care treatable,” as policy-makers have attempted to do.6 Instead, as the developers of the algorithm acknowledge, “few diagnostic categories are clear cut in all cases;”15 a discharge diagnosis related to a given ED visit can be in each of multiple categories (based on the initial complaint, vital signs, resources used in the ED, etc. that have been mapped to the discharge diagnosis),19 highlighting the complexity of the issue.

A limitation of this study is the choice of the EDA as the basis for classifying ED visits as “non-emergency.” In theory, a different list of “non-emergency diagnoses” might correspond better with chief complaints. We chose to use the EDA because – despite the intent of the EDA’s developers – the EDA has been modified for this purpose, and had been developed more rigorously than other proposed “non-emergency” diagnosis lists. We used two methodological strategies to try to optimize the classification system. First, in selecting ED visits with “non-emergency diagnoses” based on ED discharge diagnosis, we also limited the visits to those that did not result in hospital admission. Second, in using the EDA, we selected only diagnoses that, in the EDA classification system, had 100% probability of not requiring care in the ED. Had we chosen to classify visits less conservatively as other authors have – for example by including visits with low probability (but not zero probability) of needing ED care in our sample – it is likely that our results would reflect final diagnoses and ED visit characteristics of even greater severity. A list of “non-emergency diagnoses” such as the one recently proposed in Washington State,10,12 which includes some diagnoses that the EDA classifies as having substantial risk of requiring ED care, is likely to have worse performance than the approach we tested.

A second potential limitation of our study is that the only triage information we used was the patient’s chief complaint. It is possible that a combination of chief complaint and vital signs could map to diagnoses in a more helpful manner. However, previous attempts at developing triage decision rules based on chief complaint and vital signs have not succeeded.31,32 In addition, the majority of current state proposals to deny or limit Medicaid payments for ED visits use discharge diagnosis alone and do not incorporate other patient characteristics such as vital signs. A payment system that used vital signs as well as diagnosis would require more complex billing datasets and information technology than currently exist. Given the lack of alternative approaches, we anticipate that there will be further attempts to discourage ED use through retroactive denial for “non-emergency” diagnoses.

A complex interplay of community, patient, and health system factors influence ED use. 38–40 Strategies aimed narrowly at reducing such use are unlikely to improve population health or to reduce health system costs.41,42 Instead, a more innovative and sustainable path forward is through policies that allow for the creation of integrated systems of health and community care where risk is shared and resources allocated rationally. It is possible that other diagnosis lists may correspond better with chief complaints that do not occur in true emergencies. Policy-makers who are considering such approaches that involve lists of diagnoses may wish to use our rather simple methodology to evaluate the proposed lists prior to implementation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We especially thank Professor John C. Billings, JD, for his thoughtful input, Amy J. Markowitz, JD for editorial assistance, and Nicole Gordon, BA for her technical support; none of them received any financial compensation for their contributions. Dr. Hsia and Ms. Maselli had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Lowe has served as a consultant to the American College of Emergency Physicians regarding the appropriate use of emergency departments. Dr. Raven has served as a consultant for the United Hospital Fund related to patterns of ED utilization in New York City. This publication was supported by the Emergency Medicine Foundation, as well as the NIH/NCRR/OD UCSF-CTSI grant number KL2 RR024130 (RYH), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars (RYH). Its contents, including design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of any of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Maria Raven, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 505 Parnassus Ave, San Francisco, CA 94707, Maria.raven@emergency.ucsf.edu /917-499-5608 (mobile).

Robert A. Lowe, Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Department of Emergency Medicine, Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Senior Scholar, Center for Policy and Research in Emergency Medicine (CPR-EM), Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Mail Code BICC-504, Portland, Oregon 97239-3098, lowero@ohsu.edu /503 494-7134.

Judith Maselli, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, 3333 California St, Box 1211, San Francisco, CA 94143-1211, jmaselli@medicine.ucsf.edu/ 415-502-4068.

Renee Y. Hsia, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco General Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, 1001 Potrero Ave, 1E21, San Francisco, CA 94110, renee.hsia@ucsf.edu/ 415-206-4612.

References

- 1.Lowe RA, Schull M. On easy solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(3):235–238. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews AW. Medicaid Cuts Rile Doctors: Hospitals Also Fight Washington State's Drive to Trim Emergency Room Vistis. [Accessed December 21, 2012];The Wall Street Journal. 2012 Feb 25; Health Industry. Available online at http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204778604577241830930006856.html.

- 3.Smith VK, Gifford K, Ellis E, Rudowitz R, Snyder L. Moving Ahead Amid Fiscal Challenges: A Look at Medicaid Spending, Coverage and Policy Trends. Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2011 and 2012. 2011 Oct; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortensen K. Copayments Did Not Reduce Medicaid Enrollees' Nonemergency Use of Emergency Departments. Health Affairs. 2010;29(9):1632–1650. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn K. [Accessed January 15, 2013];Notice Regarding Medicaid Service Limits. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Medicaid Business and Policy; 2012. Available online at http://www.dhhs.nh.gov/ombp/medicaid/documents/edchangeclientltr.pdf.

- 6.Washington State's Medicaid Program Will No Longer Pay For Unnecessary ER Visits. [Accessed January 15, 2013];Kaiser Health News. 2012 http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/daily-reports/2012/february/08/states-medicaid.aspx.

- 7.Galewitz P. [Accessed Feb 11, 2013];Kaiser Health News: Hospitals Demand Payment Upfront from ER Patients with Routine Problems. 2012 http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2012/February/19/Hospitals-Demand-Payment-Upfront-From-ER-Patients.aspx?utm_source=khn&utm_medium=internal&utm_campaign=widget.

- 8.Pear R. Many Medicaid Patients Could Face Higher Fees Under a Proposed Federal Policy. The New York Times. 2013 Jan;22 2013; Health. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kellermann AL, Weinick RM. Emergency Departments, Medicaid Costs, and Access to Primary Care--Understanding the Link. New Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2141–2143. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1203247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blachly L. ACEP Initiative Supporting 'Prudent Layperson' Standard Becomes Law in Health Care Reform Act. [Accessed December 25, 2012];ACEP News: Clinical Practice & Management. 2010 http://www.acep.org/content.aspx?id=48650.

- 11.McCaig LF, Burt CW. Understanding and Interpreting the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: Key Questions and Answers. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe RA. Evaluation of the Washington State HCA Proposed List of "Non-Emergency" Diagnoses. Oregon Health and Science University; 2012. [Accessed January 16, 2013]. Available online at http://www.modernhealthcare.com/Assets/pdf/CH78359227.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Texas Medicaid. Bimonthly update to the Texas Medicaid Provider Procedures Manual. National Heritage Insurance Company; 2003. available at http://www.tmhp.com/Texas_Medicaid_Bulletin/176_M.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billings JC. nyu ed algorithm background. [Accessed July 31, 2012];nyu ed algorithm. http://wagner.nyu.edu/chpsr/ed_background.shtml.

- 15.Billings JC, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Emergency Room Use: The New York Story. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greci LK. Issue Brief: Profile of emergency department visits not requiring inpatient admission to a Connecticut acute care hospital, Fiscal Year 2006–2009. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.OMPRO. Comparative Assessment Report: Emergency Department Utilization, Oregon Health Plan Managed Care Plans, 2002–2003. Portland: Oregon; Mar 18, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy. Analysis in Brief. Vol 2004. Boston, MA: 2004. Non-emergency and preventable ED visits. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billings JC, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Issue Brief: Emergency Department Use in New York City: A Substitute for Primary Care? New York University and The Commonwealth Fund: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe RA, Fu R. Can the emergency department algorithm detect changes in access to care? Acad Emerg Med. 2008 Jun;15(6):506–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballard DW, Price M, Fung V, et al. Validation of an algorithm for categorizing the severity of hospital emergency department visits. Med Care. 2010 Jan;48(1):58–63. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181bd49ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wharam JFLB, Galbraith AA, Kleinman KP, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. Emergency department use and subsequent hospitalizations among members of a high-deductible health plan. JAMA. 2007;297(10):1093–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 25, 2012];Ambulatory Health Care Data-2009 Survey Methodology. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_questionnaires.htm.

- 24.Schneider D, Appleton L, McLemore R. A reason for visit classification for ambulatory care. Vital Health Stat. 1979 Feb;2(78):i–vi. 1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raman S, Levin J, Hall D, Frey K. Using Categorization of Reason-for-Visit Strings as the Basis for an Outbreak Detection System---Minnesota 2002–2003. Vol 54: Centers for Disease Control. MMWR. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 Emergency Department Summary. 7. Vol. 6. Natl Health Stat Report; Aug, 2008. pp. 1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCaig LF, Woodwell D. Analyzing data from the NAMCS and the NHAMCS. [Accessed May 11, 2012];Data Users Conference Presentations Web site 2007. 2006 2007; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_presentations.htm.

- 28.Dickinson ET, Lozada KN. Trend Alert: The trending and interpretation of vital signs. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. 2010 Mar 1; doi: 10.1016/S0197-2510(10)70066-8. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Normal Vital Signs Guidelines for EMS, by Age Group. [Accessed March 1, 2012]; http://www.scribd.com/doc/73342401/Normal-Vital-Signs-Guidelines-for-Ems.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHAMCS Micro-Data File Documentation. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbuhl SB, Lowe RA. The inappropriateness of "appropriateness". Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(3):189–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowe RA, Abbuhl SB. Appropriate standards for "appropriateness" research. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(6):629–632. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.115216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowe RA, Bindman AB, Ulrich SK, et al. Refusing care to emergency department patients: Evaluation of published triage guidelines. Ann of Emerg Med. 1994;23(2):286–293. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young GP, Lowe RA. Adverse outcomes of managed care gatekeeping. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:1129–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Brien GM, Shapiro MJ, Wollard RW, O'Sullivan PS, Stein MD. “Inappropriate” emergency department use: a comparison of three methodologies for identification. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(3):252–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birnbaum A, Gallagher EJ, Utkewicz M, Gennis P, Carter W. Failure to validate a predictive model for refusal of care to emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1(3):213–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1994.tb02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommers A, Boukus ER, Carrier ER. Dispelling Myths About Emergency Department Use: Majority of Medicaid Visits Are for Urgent or More Serious Symptoms. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowe RA, Rongwei F, Ong ET, et al. Community Characteristics Affecting Emergency Department Use by Medicaid Enrollees. Med Care. 2009;47:15–22. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181844e1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cunningham PJ. What Accounts for Differences In The Use Of Hospital Emergency Departments Across U.S. Communities? Health Affairs. 2006;25(5):w324–w336. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheung PT, Wiler JL, Lowe RA, Ginde AA. National Study of Barriers to Timely Primary Care and Emergency Department Utilization Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyrance PH, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler SW. US Emergency Department Costs: No Emergency. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(11):1527–1531. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young GP, Wagner MB, Kellermann AL, Ellis J, Bouley D. for the 24 hours in the ED Study Group. Ambulatory Visits to Hospital Emergency Departments. JAMA. 1996 Aug 14;276(6):460–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.6.460. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.